This document provides information about a handbook titled "Taylor's Musculoskeletal Problems and Injuries" which was edited by Robert B. Taylor and includes contributions from various associate editors and authors. The handbook contains 12 chapters covering a range of musculoskeletal disorders, injuries, and related topics that are relevant for primary care clinicians. It is intended to address deficiencies in musculoskeletal training for physicians in family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, and other fields involved in primary care.

![Physical Examination

The initial examination is fairly detailed. With the patient standing

and appropriately gowned, the examining physician notes the stance

and gait, as well as the presence or absence of the normal curvature of

the spine (e.g., thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, splinting to one

side, scoliosis). The range of motion of the back is documented,

including flexion, lateral bending, and rotation. Intact dorsiflexion

and plantar flexion of the foot is determined by observing heel-walk

and toe-walk. Intact knee extension is determined by observing the

patient squat and rise, while keeping the back straight.

With the patient seated, a distracted straight-leg raising test is

applied. With the hip flexed at 90 degrees, the flexed knee is brought

to full extension. A positive straight-leg raising test reproduces the

patient’s paresthesias in the distribution of a nerve root at ⬍60

degrees of knee extension. Sensation to light touch and pinprick are

examined and motor strength of hip and knee flexors is tested. The

deep tendon reflexes are tested [knee jerk (L4), ankle jerk (S1)]

and long tract signs are elicited by applying Babinski’s maneuver

(Table 1.1).

With the patient in the supine position, the straight-leg raising test

is repeated. With the hip and knee extended, the leg is raised (i.e., the

1. Disorders of the Back and Neck 5

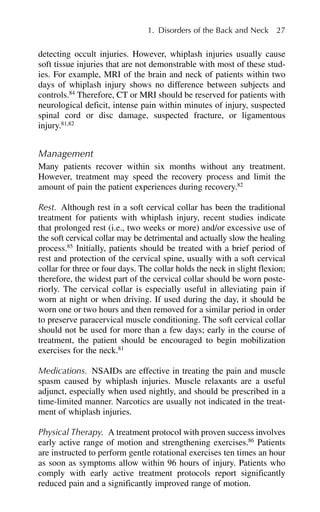

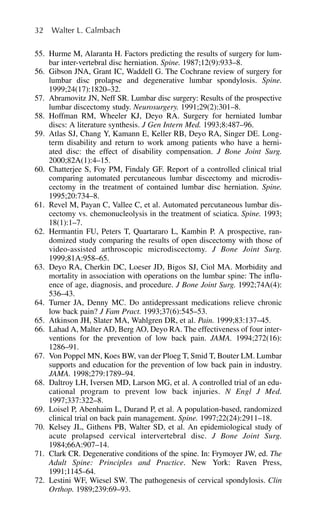

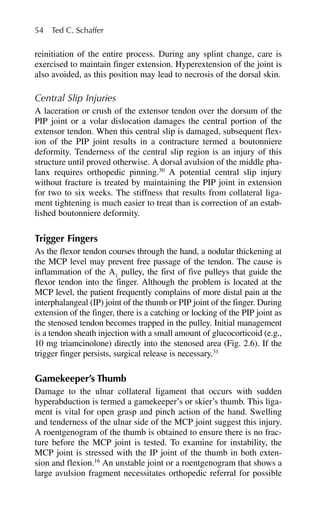

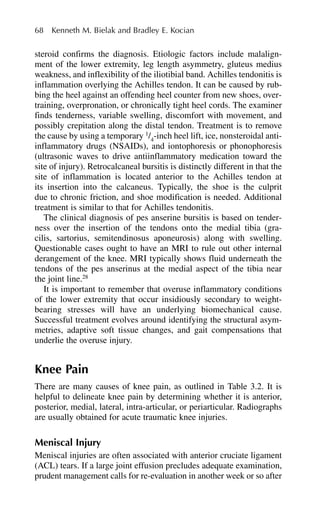

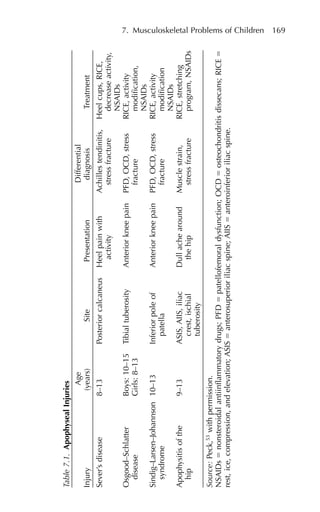

Table 1.1. Motor, Sensory, and Deep Tendon Reflex Patterns

Associated with Commonly Affected Nerve Roots

Deep tendon

Nerve root Motor reflexes Sensory reflexes reflexes

C5 Deltoid Lateral arm Biceps jerk (C5,C6)

C6 Biceps, Lateral forearm Brachioradialis

brachioradialis,

wrist extensors

C7 Triceps, wrist Middle of hand, Triceps jerk

flexors, MCP middle finger

extensors

C8 MCP flexors Medial forearm —

T1 Abductors and Medial arm —

adductors of

fingers

L4 Quadriceps Anterior thigh Knee jerk

L5 Dorsiflex foot Dorsum of foot Hamstring reflex

and great toe (L5, S1)

S1 Plantarflex foot Lateral foot, Ankle jerk

posterior calf

MCP ⫽ metacarpophalangeal.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/musculoskeletalpocketbook-230104013636-e7f180fd/85/musculoskeletal-pocketbook-pdf-19-320.jpg)

![Examination of the patient with a rotator cuff injury reveals painful or

limited active abduction (between 60 and 120 degrees), where the cuff

comes in greatest contact with the overlying acromial arch.9

With a

significant cuff tear, the patient is frequently unable to hold the arm in

90 degrees of abduction. Atrophy may develop in the supraspinatus or

infraspinatus muscles of the scapula. If a cuff tear is suspected, ortho-

pedic referral with arthroscopy or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

is indicated to delineate potential surgical cases. With any cuff injury

an extensive rehabilitation program of three to six months is needed

to gain full motion and strength.

Subacromial Bursitis

The subacromial bursa separates the deltoid muscle from the underly-

ing rotator cuff. Irritation of adjacent structures, most commonly

impingement of the rotator cuff, results in inflammatory bursitis.

Often there is a history of overuse or trauma followed by pain and

limited active motion. Aspiration of excessive bursal fluid followed

by corticosteroid injection using a subacromial lateral or posterior

approach can provide dramatic relief of this problem.3

Adequate vol-

ume of injection [5 to 10 cc lidocaine (Xylocaine) plus corticosteroid]

should be used to optimize injection results.

Calcific tendonitis, usually within the supraspinatus insertion, may

cause an acute inflammatory reaction of the overlying subacromial

bursa. Roentgenograms demonstrate a calcific deposit superior and

lateral to the humerus. The severe pain can be relieved by needle aspi-

ration of the calcific mass along with a lidocaine and corticosteroid

injection of the bursa. Occasionally surgical excision of the calcific

deposition is required.10

Bicipital Tendonitis and Rupture

The long head of the biceps tendon, which is palpable in the bicipital

groove, may be irritated as it courses through the glenohumeral joint

and below the supraspinatus tendon to its attachment at the superior

sulcus of the glenoid. Isolated pain over the long head of the biceps

tendon suggests this problem, although usually there is more diffuse

tenderness involving the entire subacromial region. The short head of

the biceps tendon attaches to the coracoid process and is rarely

involved in inflammatory problems of the shoulder. In most cases rup-

ture of the long head of the biceps tendon occurs as a result of

advanced impingement in middle-aged or elderly patients. There is a

sudden pop associated with a heavy isometric flexion of the arm such

as lifting a heavy object with that arm. The patient experiences mild

40 Ted C. Schaffer](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/musculoskeletalpocketbook-230104013636-e7f180fd/85/musculoskeletal-pocketbook-pdf-54-320.jpg)

![tensile trabeculae, and wider trochanteric region) on plain radiographs

were as predictive of risk for hip fracture as bone mineral density

determinations.4

Dexa scanning has become an important tool in

screening for osteoporosis.

The best treatment for osteoporosis is prevention. Preventive meas-

ures include hormone replacement therapy, exercise, alendronate,

increased calcium intake, and calcitonins (see Reference 56, Chapter

122). Recently, combination therapies of estrogen and alendronate

have yielded even greater increases in bone mineral density and are

tolerated quite well.5

Certain facts are important to remember when

considering the prescription of preventive measures: short-term inter-

vention late in the natural course of osteoporosis may have significant

effects on the incidence of hip fractures;6

hip fracture may be associ-

ated with reduced muscle strength rather than reduced body mass or

fat;7,8

long-term heavy activity reduces the risk of hip fracture in post-

menopausal women;9

and height appears to be an important inde-

pendent risk factor for hip fracture among American women and

men.10

Factors that are protective [relative risk (RR) ⬍1] against hip

fracture in the elderly are an increase in weight after age 25 and rou-

tine walking for exercise.

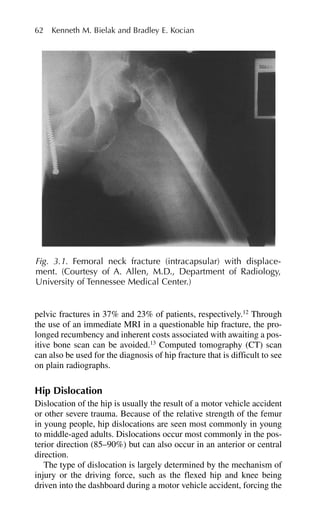

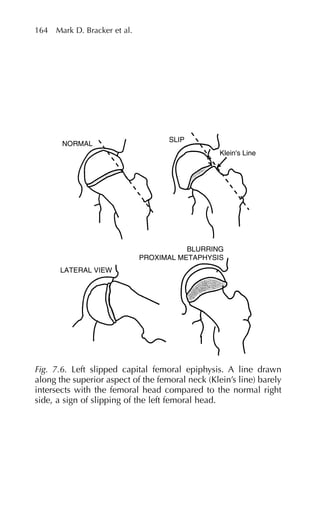

Fractures of the proximal femur can be classified as femoral neck,

intertrochanteric, or subtrochanteric based on anatomic site. Fractures

of the femoral neck (cervical or intracapsular) result from an indirect

shear force on the angulated femoral neck (Fig. 3.1). They are found

more commonly in the elderly and have a high risk for complications,

such as avascular necrosis. Fractures of the neck of the femur are

painful and can be associated with little bruising or swelling. It is

important to note that a nondisplaced fracture can be ambulated upon,

albeit with some degree of pain. A displaced fracture of the hip causes

shortening and external rotation. Extracapsular (intertrochanteric and

subtrochanteric) fractures occur with direct trauma to the hip, result-

ing in immediate pain, inability to ambulate, and generally significant

loss of blood. In the elderly, trochanteric fractures have been associ-

ated with up to twice the short-term mortality of cervical fractures. In

terms of measured bone mineral density (BMD), a relatively low

trochanteric BMD or a high femoral neck BMD is associated with

trochanteric hip fracture.11

Immediate referral for orthopedic surgery

is necessary. Treatment options take into account the type and extent

of fracture: cervical fractures in the elderly and significant displace-

ments require hip replacement, and extracapsular fractures respond

well with repair and internal fixation.

With suspected hip fracture and negative plain radiographs, mag-

netic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated occult femoral and

3. Disorders of the Lower Extremity 61](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/musculoskeletalpocketbook-230104013636-e7f180fd/85/musculoskeletal-pocketbook-pdf-75-320.jpg)

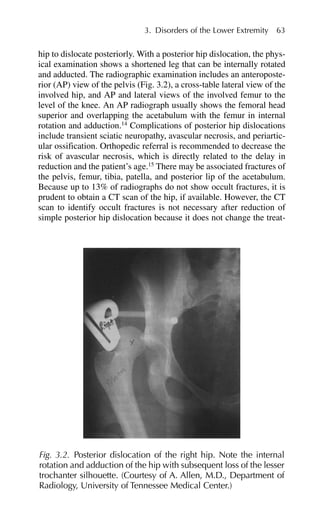

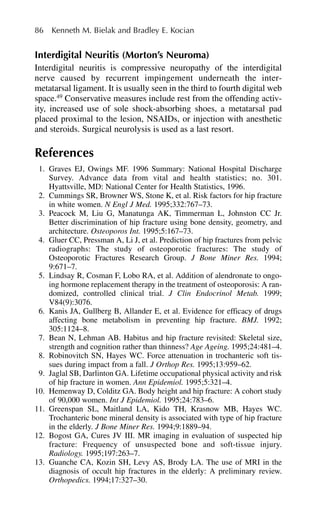

![ment plan.16

In the absence of penetrating trauma, intracapsular gas

bubbles on CT are reliable indicators of recent hip dislocation and

may be the only objective finding of this injury.17

MRI can be used for

the early detection of osteonecrosis of the femoral head after trau-

matic hip dislocation or fracture dislocation.18

Traumatic anterior dislocation of the hip represents 11% of all hip

dislocations and is classified into superior and inferior types.

Associated femoral head fractures are common, but acetabular frac-

tures are relatively rare. Whereas inferoanterior hip dislocation is eas-

ily recognized on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis, the

radiographic appearance of superoanterior hip dislocation is less

straightforward. Misinterpretation of a superoanterior hip dislocation

can lead to an initial misdiagnosis of posterior hip dislocation, which

has implications for the surgical approach and may result in failed

closed reduction.19

The superoanterior dislocation of the femoral head

can be distinguished from the posterior dislocation by noting a more

lateral orientation to the acetabulum and an externally rotated femur

that is not adducted. The lesser trochanter becomes more prominent

medially.20

Central hip dislocations usually occur with resulting fracture to the

iliopubic portion of the acetabulum as a severe lateral blow to the hip

drives the femoral head medially. There are usually other skeletal and

soft tissue injuries associated with this type of injury.14

After closed reduction of a hip dislocation, it is necessary to con-

firm concentric reduction (the joint space is equidistant on plain radi-

ograph or CT scan). The absence of concentric reduction suggests an

interposition of soft tissue in the joint. Early diagnosis and treatment

of this serious complication can avoid the poor results of open and

deferred treatments.21

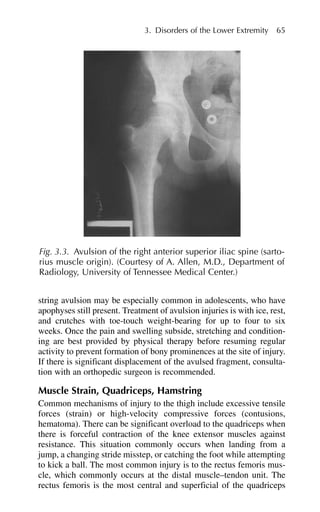

Pelvic Avulsion Injuries

The bony attachments of the sartorius [anterior superior iliac spine

(ASIS)], rectus femoris (anterior inferior iliac spine), and the ham-

strings (ischial tuberosity) can be individually avulsed by sudden

overloading of the respective muscles (acute muscular contraction

against a fixed resistance). The history is typically a sudden onset of

extreme pain following sudden, forceful acceleration or deceleration.

Localized pain and swelling at the site of injury and increased dis-

comfort with passive stretching and muscle contraction against resist-

ance suggest the diagnosis. Plain radiographs confirm the injury (Fig.

3.3). Subtleties may make the diagnosis obscure, and MRI may be a

more sensitive and accurate way to establish the diagnosis. The ham-

64 Kenneth M. Bielak and Bradley E. Kocian](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/musculoskeletalpocketbook-230104013636-e7f180fd/85/musculoskeletal-pocketbook-pdf-78-320.jpg)

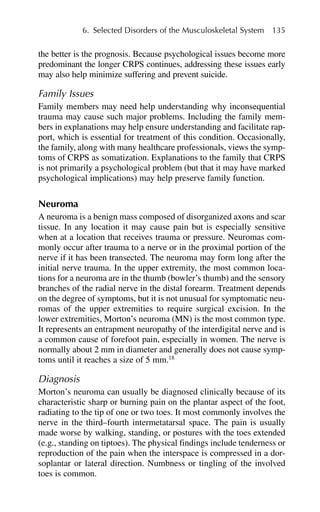

![management strategies for OA include periods of rest (one to two

hours) when symptoms are at their worst, avoidance of repetitive

movements or static body positions that aggravate symptoms, heat

(or cold) for the control of pain, weight loss if the patient is over-

weight, adaptive mobility aids to diminish the mechanical load on

joints, adaptive equipment to assist in activities of daily living

(ADL), range of motion exercises, strengthening exercises, and

endurance exercises.11,12

Immobilization should be avoided. The use

of adaptive mobility aids (e.g., canes, walkers) is an important strat-

egy, but care must be taken to ensure that the mobility aid is the cor-

rect device, properly used, appropriately sized, and in good repair.

Medial knee taping to realign the patella in patients with

patellofemoral OA, and the use of wedged insoles for patients with

medial compartment OA and shock-absorbing footwear may help

reduce joint symptoms.10,13

Pharmacological approaches to the treatment of OA include aceta-

minophen, salicylates, nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) specific inhibitors, top-

ical analgesics, and intra-articular steroids.14,15

Acetaminophen is

advocated for use as first-line therapy for relief of mild to moderate

pain, but it should be used cautiously in patients with liver disease or

chronic alcohol abuse. Salicylates and NSAIDs are commonly used as

first-line medications for the relief of pain related to OA. Compliance

with salicylates can be a major problem given their short duration of

action and the need for frequent dosing; thus NSAIDs are preferable to

salicylates. There is no justification for choosing one nonselective

NSAID over another based on efficacy, but it is clear that a patient who

does not respond to an NSAID from one class may well respond to an

NSAID from another. The choice of a nonselective NSAID versus a

COX-2 specific inhibitor should be made after assessment of risk for

GI toxicity (e.g., age 65 or older, history of peptic ulcer disease, previ-

ous GI bleeding, use of oral corticosteroids or anticoagulants). For

patients at increased risk for upper GI bleeding, the use of a nonselec-

tive NSAID and gastroprotective therapy or a COX-2 specific inhibitor

is indicated. NSAIDs should be avoided or used with extreme caution

in patients at risk for renal toxicity [e.g., intrinsic renal disease, age 65

or over, hypertension, congestive heart failure, and concomitant use of

diuretics or angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors].10

COX-

2 inhibitors increase the risk of heart attack and stroke.

Topical capsaicin may improve hand or knee OA symptoms when

added to the usual treatment; however, its use may be limited by

cost and the delayed onset of effect requiring multiple applications

daily and sustained use for up to four weeks. Intra-articular steroids

92 Alicia D. Monroe and John B. Murphy](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/musculoskeletalpocketbook-230104013636-e7f180fd/85/musculoskeletal-pocketbook-pdf-106-320.jpg)

![with a platelet count as low as 20,000 cells/mm.3,23

Furthermore, SLE

patients have higher incidences of both arterial and venous thromboem-

bolic events. Some studies have shown up to a fiftyfold increase in risk

of myocardial infarction among reproductive-aged women with SLE,

compared to age-matched controls.18

Some investigators have recom-

mended prophylactic aspirin or other anticoagulation treatment for all

SLE patients, regardless of antiphospholipid status,24

and aggressive

anticoagulation with warfarin [with a goal international normalized ratio

(INR) of 2.5–3.5] for patients with known antiphospholipid antibodies.18

Treatment

Treatment of SLE is best tailored to individual patients and their specific

symptoms. Current treatment regimens have in general been successful

in decreasing the morbidity and mortality associated with SLE. Current

data indicate that more than 90% of patients survive at least 15 years.

All SLE patients are encouraged to minimize sun exposure and to use

sunscreen. The most common complaint, arthralgias, can often be ade-

quately treated with NSAIDs. Patients being treated long term with

NSAIDs should be monitored periodically for renal and hepatic side

effects. Glucocorticoids have also been used to treat severe symptoms,

but they increase the risk of side effects. Cutaneous manifestations of

SLE generally respond well to treatment with antimalarials (i.e.,

hydroxychloroquine or quinacrine). For treatment of skin disease resist-

ant to either of these agents, small studies have used dapsone, azathio-

prine, gold, intralesional interferon, and retinoids. Methotrexate is more

effective than placebo for moderate SLE without renal involvement.18

The foundation of treatment of SLE patients with renal disease has

long been glucocorticoid therapy; however, this practice is being chal-

lenged. Patients with mild disease can often be managed with low-

dose prednisone; patients with diffuse proliferative or severe focal

proliferative glomerulonephritis may require a two-month course of

high-dose prednisone (1 mg/kg) followed by a prolonged taper.

However, studies using cyclophosphamide have shown this drug to be

effective as either a single agent or in combination with glucocorti-

coids, and more effective than glucocorticoids alone.18,23

Like treatment of renal disease, the mainstay for treating thrombocy-

topenia has long been glucocorticoids. Patients with disease resistant to

glucocorticoid treatment may respond to splenectomy, but prior to con-

sideration of splenectomy providers must weigh the benefits against the

risks posed by decreased immune function. Cyclophosphamide and

chemotherapeutic agents such as vincristine and procarbazine have also

been used in patients with severe disease.23

118 Joseph W. Gravel Jr., Patricia A. Sereno, Katherine E. Miller](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/musculoskeletalpocketbook-230104013636-e7f180fd/85/musculoskeletal-pocketbook-pdf-132-320.jpg)

![bone resorption mediated by osteoclasts and are effective in Paget’s

disease. These treatments have significant potential side effects and

complications. The alkaline phosphatase level can be used to monitor

disease activity.

Prognosis. The later in life that Paget’s disease begins, the better is

the prognosis. The progression is usually slow, over years. Renal

complications and malignant degeneration of lesions are associated

with a poor prognosis.

References

1. Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: More than just a musculoskeletal disease. Am

Fam Physician. 1995;52:843–51.

2. Goldenberg DL. Fibromyalgia syndrome: An emerging but controversial

condition. JAMA. 1987;257:2782–7.

3. Stormorken H, Brosstad F. Fibromyalgia: Family clustering and sensory

urgency with early onset indicate genetic predisposition and thus a “true”

disease [letter]. Scand J Rheumatol. 1992;21:207–11.

4. Silman A, Schollum J, Croft P. The epidemiology of tender point counts

in the general population [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(suppl):48.

5. Granges G, Littlejohn GO. A comparative study of clinical signs in

fibromyalgia/fibrositis syndrome, healthy and exercising subjects. J

Rheumatol. 1993;20:344–51.

6. Reynolds WJ, Moldofsky H, Saskin P, et al. The effects of cyclobenza-

prine on sleep physiology and symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia. J

Rheumatol. 1991;18:452–4.

7. Simms RW, Goldenberg DL. Symptoms mimicking neurologic disorders

in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1271–3.

8. Pellegrino MJ, Van Fossen D, Gordon C, et al. Prevalence of mitral valve

prolapse in primary fibromyalgia: A pilot investigation. Arch Phys Med

Rehabil. 1989;70:541–3.

9. Goldenberg DL. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheum Dis

Clin North Am. 1989;15:499–512.

10. Felson DT, Goldenberg DL. The natural history of fibromyalgia. Arthritis

Rheum. 1986;29:1522–6.

11. Yunus MB, Kalyan-Raman UP, Kalyan-Raman K. Primary fibromyalgia

syndrome and myofascial pain syndrome: Clinical features and muscle

pathology. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69:451–4.

12. Thompson JM. Tension myalgia as a diagnosis at the Mayo Clinic and its

relationship to fibrositis, fibromyalgia, and myofascial pain syndrome.

Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:1237–48.

13. Harden RN, Bruehl SP, Gass S, Niemiec C, Barbick B. Signs and symp-

toms of the myofascial pain syndrome: A national survey of pain man-

agement providers. Clin J Pain. 2000;16(1):64–72.

14. Lederhaas G. Complex regional pain syndrome: New emphasis. Emerg

Med. 2000;32:18–22.

6. Selected Disorders of the Musculoskeletal System 145](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/musculoskeletalpocketbook-230104013636-e7f180fd/85/musculoskeletal-pocketbook-pdf-159-320.jpg)

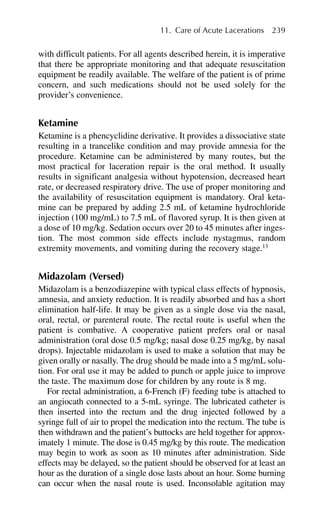

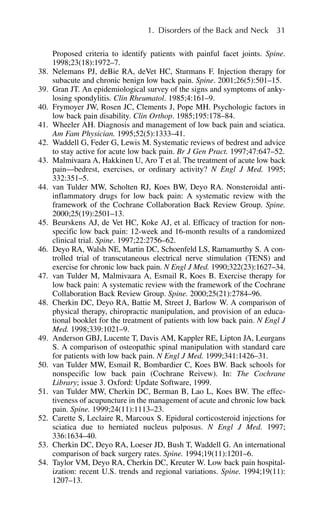

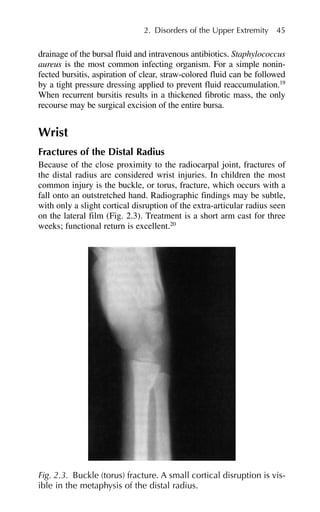

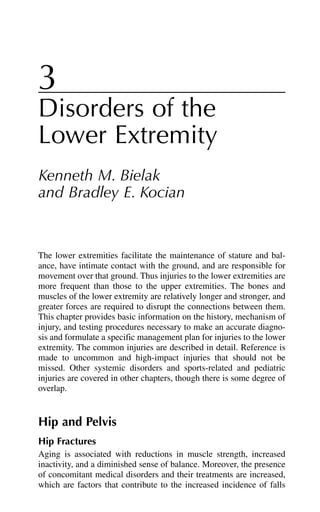

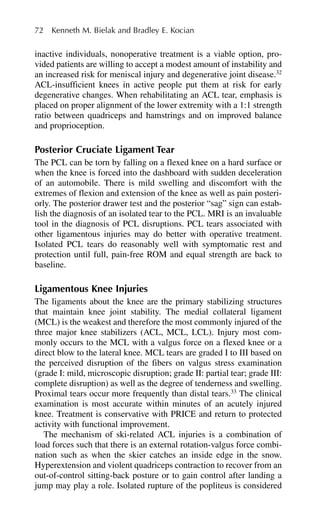

![Terminology

Definitions of the terms used in this chapter are as follows.

Angle of gait (foot progression angle): Angle of the intersection

between the foot axis and the line progression. It is the result of

static and dynamic influences from the foot to the hip. This angle

remains relatively stable at 8 to 12 degrees of out-toeing through

growth. There is a wide range of normal values varying from 3

degrees in-toeing to 20 degrees out-toeing; in one study of 130 chil-

dren, 4.5% had an in-toeing gait.2

Abnormalities anywhere along

this kinetic chain (including hip, leg, and foot) can change the angle

of gait.

Femoral antetorsion: Anteversion beyond the normal range [2 stan-

dard deviations (SD)].

Femoral anteversion: Angular difference between the forward

inclination of the femoral neck and the transcondylar femoral axis

(Fig. 7.2).

148 Mark D. Bracker et al.

A

C D E

c

B

b

a

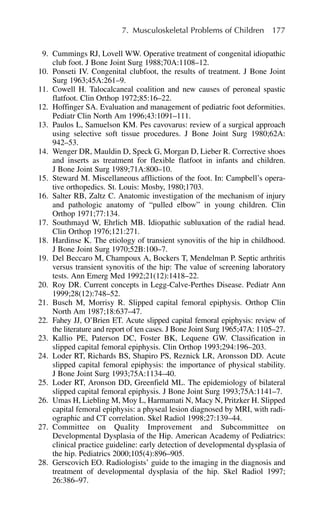

Fig. 7.1. Tests for torsional deformities (see text for full discus-

sion). (A) Foot progression angle (a) is formed by the foot axis (B)

and the line of progression (b). (B) Foot axis. (C) Measurement of

internal femoral rotation. (D) Measurement of external femoral

rotation. (E) Thigh-foot angle (c) is formed by the longitudinal axis

of the femur and the foot axis. (From Lillegard and Kruse,50

with

permission.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/musculoskeletalpocketbook-230104013636-e7f180fd/85/musculoskeletal-pocketbook-pdf-162-320.jpg)

![Management

Modification of shoulder activity and antiinflammatory measures [the

RICE protocol, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)] are

instituted early. Swimmers will need to alter the strokes during their

training periods and reduce the distance that they swim to the point

that the pain is decreasing daily. Rehabilitation exercises should con-

sist of both aggressive shoulder stretching to lengthen the cora-

coacromial ligament and improve range of motion. The use of an

upper arm counterforce brace will alter the fulcrum of the biceps in

such a way as to depress the humeral head further. Strength training

of the supraspinatus and biceps internal and external rotator muscles

should be performed to aid in depressing the humeral head when

stressed, thus increasing the subacromial space. In advanced calcific

tendonitis, steroid injection into the subacromial bursa or surgical

removal of the calcific tendon may be required.18

Tennis Elbow (Lateral Epicondylitis)

Lateral epicondylitis is characterized by point tenderness of the lateral

epicondyle at the attachment of the extensor carpi radialis brevis. The

most common sports that cause this syndrome are tennis, racquetball,

and cross-country skiing.19

The mechanism of injury in all of the sports

is the repetitive extension of the wrist against resistance. Adolescent or

preadolescent athletes are at highest risk of significant injury if the

growth plate that underlies the lateral epicondyle is not yet closed. If

the inflammation of the epicondyle is not arrested, the soft growth car-

tilage can fracture and rotate the bony attachment of the extensor liga-

ments, requiring surgical reimplantation of the epicondyle. Without

surgery, a permanent deformity of the elbow will result.

Diagnosis

Patients will complain of pain with active extension of the wrist local-

ized to the upper forearm and lateral epicondyle. There is usually

marked tenderness of the epicondyle itself. Pain with grasping a

weighted cup (Canard’s test) or with resisted dorsiflexion is also diag-

nostic. X-ray studies are not necessary but may show calcific changes

to the extensor aponeurosis in chronic cases. Comparison views of the

unaffected elbow may be helpful in the adolescent in whom a stress

fracture is suspected and the growth plate is not yet closed. Stress

fractures of the lateral epicondyle are best diagnosed with a tech-

netium-99 (Te-99) bone scan.

10. Athletic Injuries 223](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/musculoskeletalpocketbook-230104013636-e7f180fd/85/musculoskeletal-pocketbook-pdf-237-320.jpg)