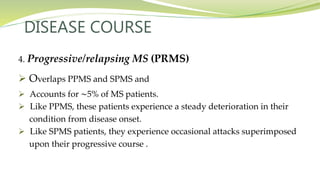

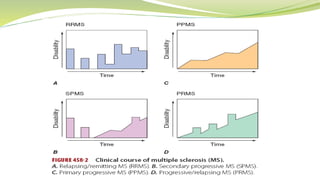

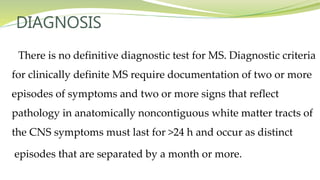

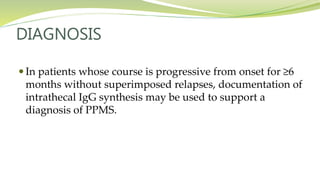

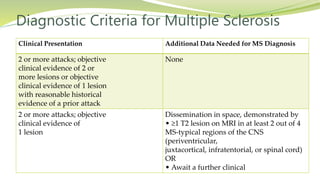

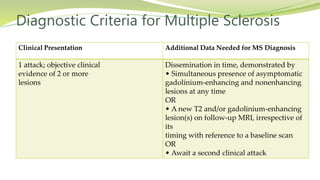

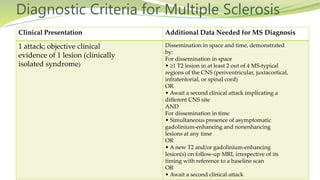

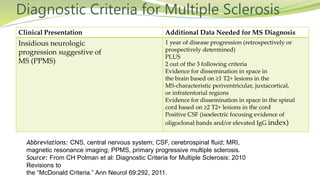

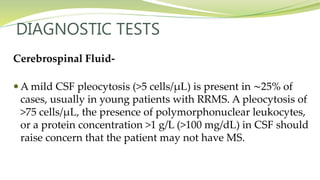

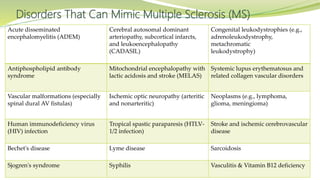

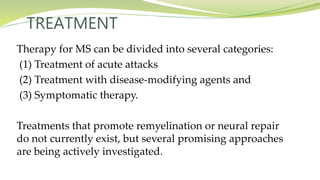

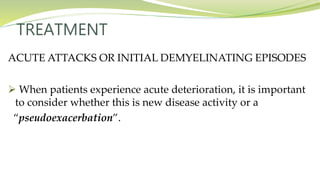

Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease that affects the central nervous system. It is characterized by chronic inflammation, demyelination, and scarring of the brain and spinal cord. Lesions typically develop in different areas of the central nervous system at different times. Approximately 350,000 people in the US and 2.5 million worldwide have MS. The clinical course can vary significantly between individuals. There is no definitive test for diagnosing MS, but criteria require evidence of lesions in different areas of the central nervous system separated in time and space, supported by MRI or other tests.