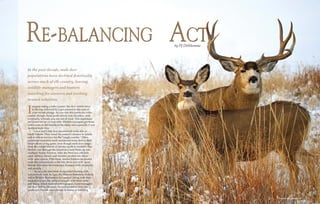

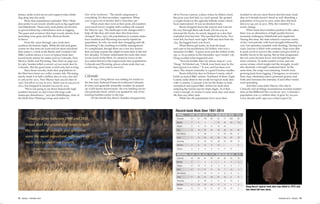

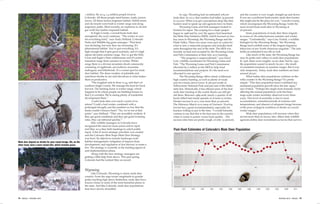

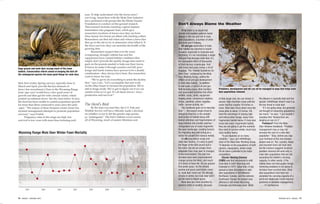

This document summarizes the history of mule deer populations in the western United States and some of the key factors that have impacted their numbers. It describes how mule deer populations exploded in the late 1800s and early 1900s due to landscape changes from settlement and resource extraction. Numbers hit historic highs from the 1950s-1970s but have since declined drastically across much of the West. Reasons for the decline include less landscape disturbances, invasive species that reduced habitat quality, prolonged drought, and increased competition from growing elk populations. The document focuses on population trends and management efforts in Colorado and Wyoming to understand the challenges facing mule deer recovery.