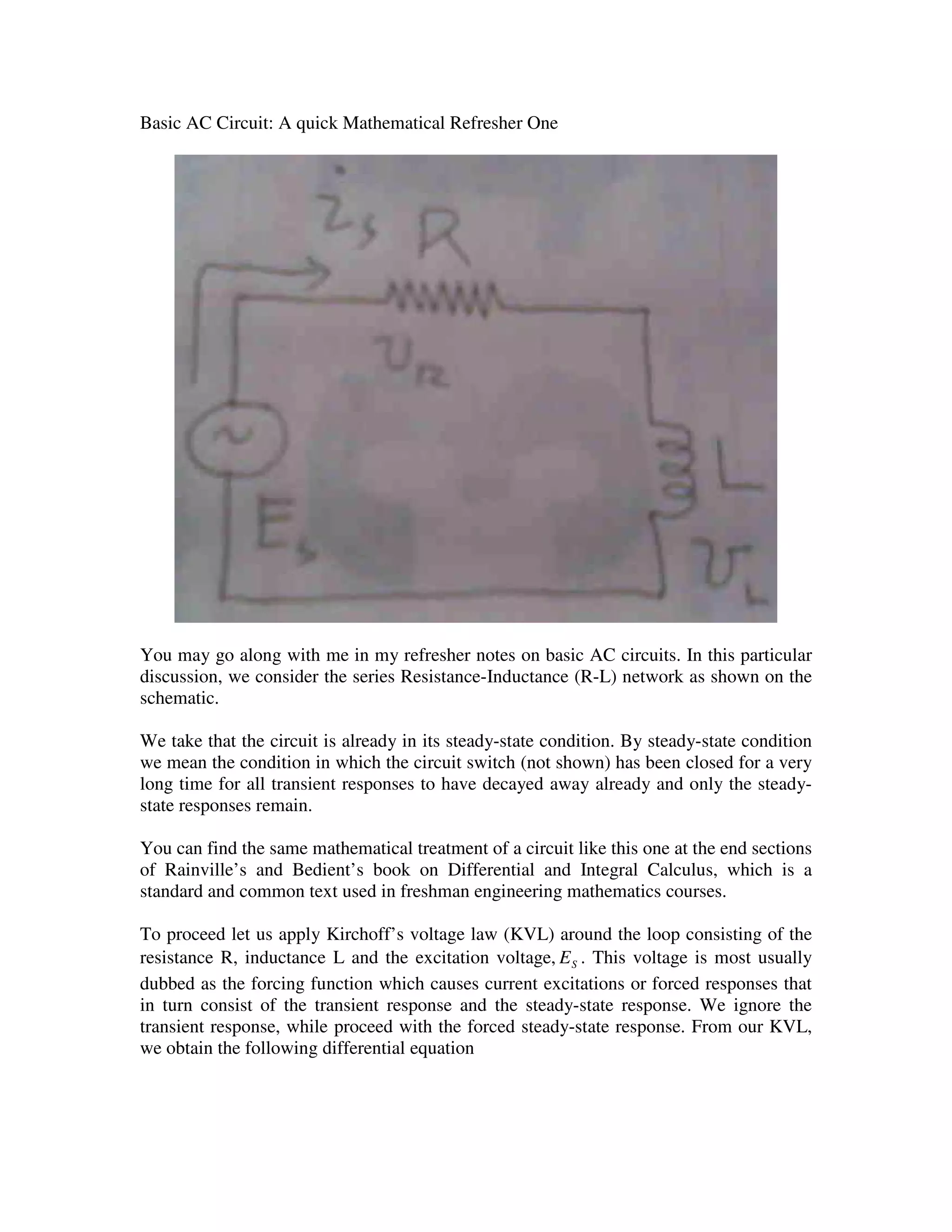

1) The document discusses the mathematical analysis of a basic AC circuit consisting of a resistor and inductor connected in series and driven by an external sinusoidal voltage source.

2) Kirchhoff's voltage law is applied to derive the differential equation governing the circuit and the forced steady-state response is shown to be a sinusoidal current lagging the driving voltage by a phase angle.

3) Expressions are derived relating the phase lag to the circuit properties and defining the real and reactive power consumed based on the circuit response.