Java Foundations Introduction To Program Design And Data Structures 2nd Edition 2nd Edition John Lewis

Java Foundations Introduction To Program Design And Data Structures 2nd Edition 2nd Edition John Lewis

Java Foundations Introduction To Program Design And Data Structures 2nd Edition 2nd Edition John Lewis

![All Java applications have a main method, which is where processing begins.

Each programming statement in the main method is executed, one at a time in order,

until the end of the method is reached. Then the program ends, or terminates. The

main method definition in a Java program is always preceded by the words public,

static, and void, which we examine later in the text. The use of String and args

does not come into play in this particular program. We describe these later also.

The two lines of code in the main method invoke another method called

println (pronounced print line). We invoke, or call, a method when we want it

to execute. The println method prints the specified characters to the screen. The

characters to be printed are represented as a character string, enclosed in double

quote characters ("). When the program is executed, it calls the println method

to print the first statement, calls it again to print the second statement, and then,

because that is the last line in the main method, the program terminates.

The code executed when the println method is invoked is not defined in this

program. The println method is part of the System.out object, which is part of

4 CHAPTER 1 Introduction

L I S T I N G 1 . 1

//********************************************************************

// Lincoln.java Java Foundations

//

// Demonstrates the basic structure of a Java application.

//********************************************************************

public class Lincoln

{

//-----------------------------------------------------------------

// Prints a presidential quote.

//-----------------------------------------------------------------

public static void main (String[] args)

{

System.out.println ("A quote by Abraham Lincoln:");

System.out.println ("Whatever you are, be a good one.");

}

}

O U T P U T

A quote by Abraham Lincoln:

Whatever you are, be a good one.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1177801-250514101831-6cf35add/85/Java-Foundations-Introduction-To-Program-Design-And-Data-Structures-2nd-Edition-2nd-Edition-John-Lewis-37-320.jpg)

![1.1 The Java Programming Language 9

code may have trouble figuring out what you meant. It might not even be clear to

you two months after writing it.

A name in Java is a series of identifiers separated by the dot (period) character.

The name System.out is the way we designate the object through which we in-

voked the println method. Names appear quite regularly in Java programs.

White Space

All Java programs use white space to separate the words and symbols used in a

program. White space consists of blanks, tabs, and newline characters. The

phrase white space refers to the fact that, on a white sheet of paper with black

printing, the space between the words and symbols is white. The way a program-

mer uses white space is important because it can be used to emphasize parts of the

code and can make a program easier to read.

Except when it’s used to separate words, the computer ignores

white space. It does not affect the execution of a program. This fact

gives programmers a great deal of flexibility in how they format a

program. The lines of a program should be divided in logical places

and certain lines should be indented and aligned so that the pro-

gram’s underlying structure is clear.

Because white space is ignored, we can write a program in many different

ways. For example, taking white space to one extreme, we could put as many

words as possible on each line. The code in Listing 1.2, the Lincoln2 program, is

formatted quite differently from Lincoln but prints the same message.

//********************************************************************

// Lincoln2.java Java Foundations

//

// Demonstrates a poorly formatted, though valid, program.

//********************************************************************

public class Lincoln2{public static void main(String[]args){

System.out.println("A quote by Abraham Lincoln:");

System.out.println("Whatever you are, be a good one.");}}

O U T P U T

A quote by Abraham Lincoln:

Whatever you are, be a good one.

L I S T I N G 1 . 2

KEY CONCEPT

Appropriate use of white space

makes a program easier to read

and understand.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1177801-250514101831-6cf35add/85/Java-Foundations-Introduction-To-Program-Design-And-Data-Structures-2nd-Edition-2nd-Edition-John-Lewis-42-320.jpg)

![10 CHAPTER 1 Introduction

Taking white space to the other extreme, we could write almost every word

and symbol on a different line with varying amounts of spaces, such as Lincoln3,

shown in Listing 1.3.

All three versions of Lincoln are technically valid and will exe-

cute in the same way, but they are radically different from a reader’s

point of view. Both of the latter examples show poor style and make

the program difficult to understand. You may be asked to adhere to

particular guidelines when you write your programs. A software

//********************************************************************

// Lincoln3.java Java Foundations

//

// Demonstrates another valid program that is poorly formatted.

//********************************************************************

public class

Lincoln3

{

public

static

void

main

(

String

[]

args )

{

System.out.println (

"A quote by Abraham Lincoln:" )

; System.out.println

(

"Whatever you are, be a good one."

)

;

}

}

O U T P U T

A quote by Abraham Lincoln:

Whatever you are, be a good one.

L I S T I N G 1 . 3

KEY CONCEPT

You should adhere to a set of guide-

lines that establishes the way you

format and document your

programs.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1177801-250514101831-6cf35add/85/Java-Foundations-Introduction-To-Program-Design-And-Data-Structures-2nd-Edition-2nd-Edition-John-Lewis-43-320.jpg)

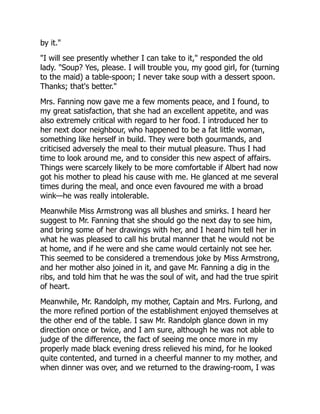

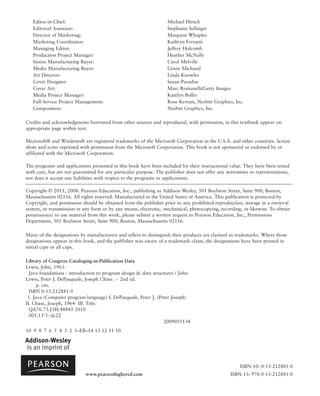

![1.2 Program Development 13

high-level language code must be translated into machine language in order to

be executed.

Some programming languages are considered to operate at an even higher level

than high-level languages. They might include special facilities for automatic report

generation or interaction with a database. These languages are called fourth-generation

languages, or simply 4GLs, because they followed the first three generations of

computer programming: machine, assembly, and high-level.

Editors, Compilers, and Interpreters

Several special-purpose programs are needed to help with the process of develop-

ing new programs. They are sometimes called software tools because they are

used to build programs. Examples of basic software tools include an editor, a

compiler, and an interpreter.

Initially, you use an editor as you type a program into a computer and store it

in a file. There are many different editors with many different features. You

should become familiar with the editor you will use regularly because it can dra-

matically affect the speed at which you enter and modify your programs.

Figure 1.3 on the next page shows a very basic view of the program development

process. After editing and saving your program, you attempt to translate it from

high-level code into a form that can be executed. That translation may result in er-

rors, in which case you return to the editor to make changes to the code to fix the

problems. Once the translation occurs successfully, you can execute the program

and evaluate the results. If the results are not what you want, or if you want to en-

hance your existing program, you again return to the editor to make changes.

The translation of source code into (ultimately) machine language for a partic-

ular type of CPU can occur in a variety of ways. A compiler is a program that

FIGURE 1.2 A high-level expression and its assembly language

and machine language equivalent

High-Level Language Assembly Language Machine Language

<a + b> 1d [%fp–20], %o0

1d [%fp–24], %o1

add %o0, %o1, %o0

...

1101 0000 0000 0111

1011 1111 1110 1000

1101 0010 0000 0111

1011 1111 1110 1000

1001 0000 0000 0000

...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1177801-250514101831-6cf35add/85/Java-Foundations-Introduction-To-Program-Design-And-Data-Structures-2nd-Edition-2nd-Edition-John-Lewis-46-320.jpg)