This document discusses Flex and Bison, which are tools for generating lexical analyzers and parsers.

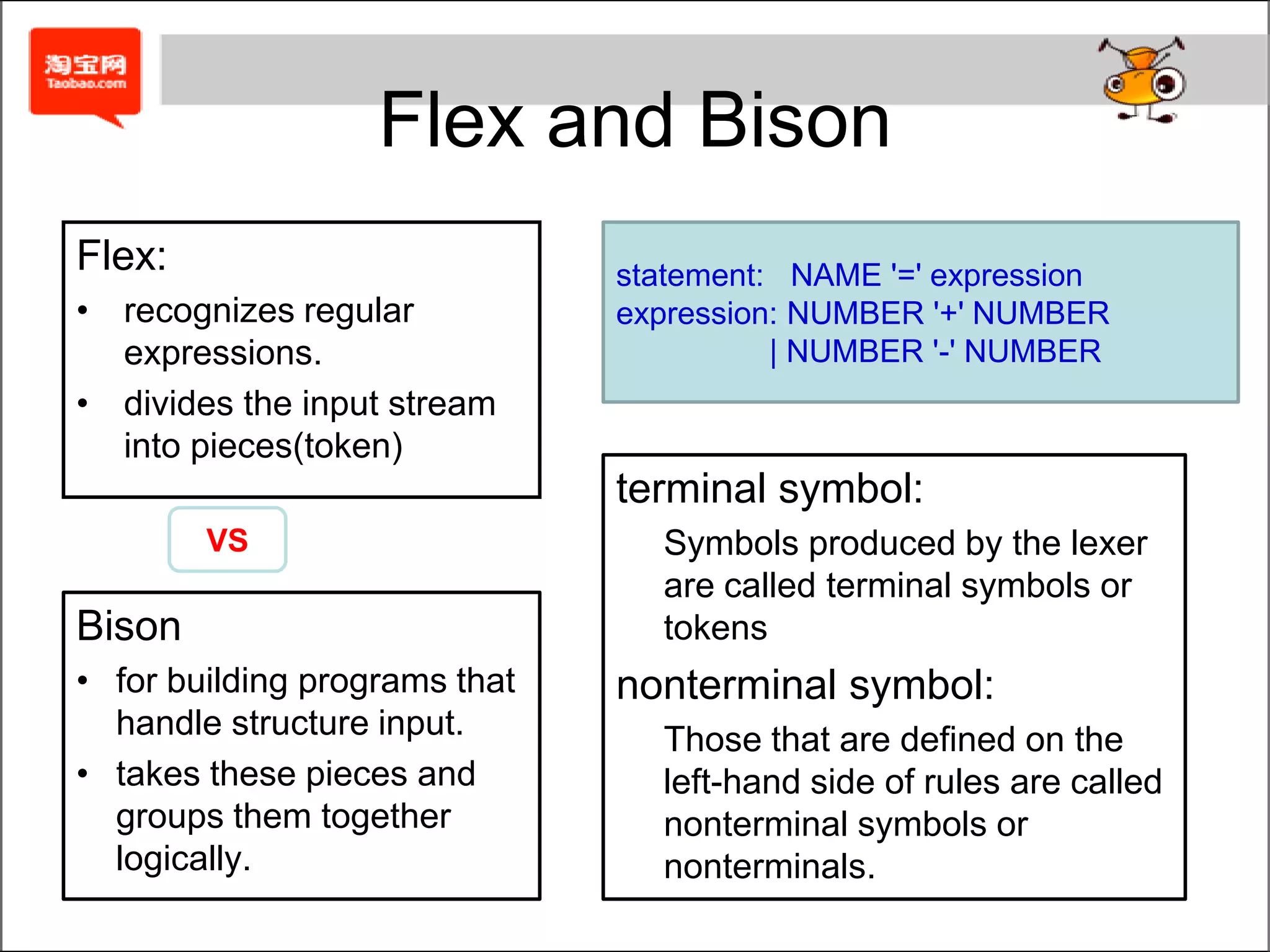

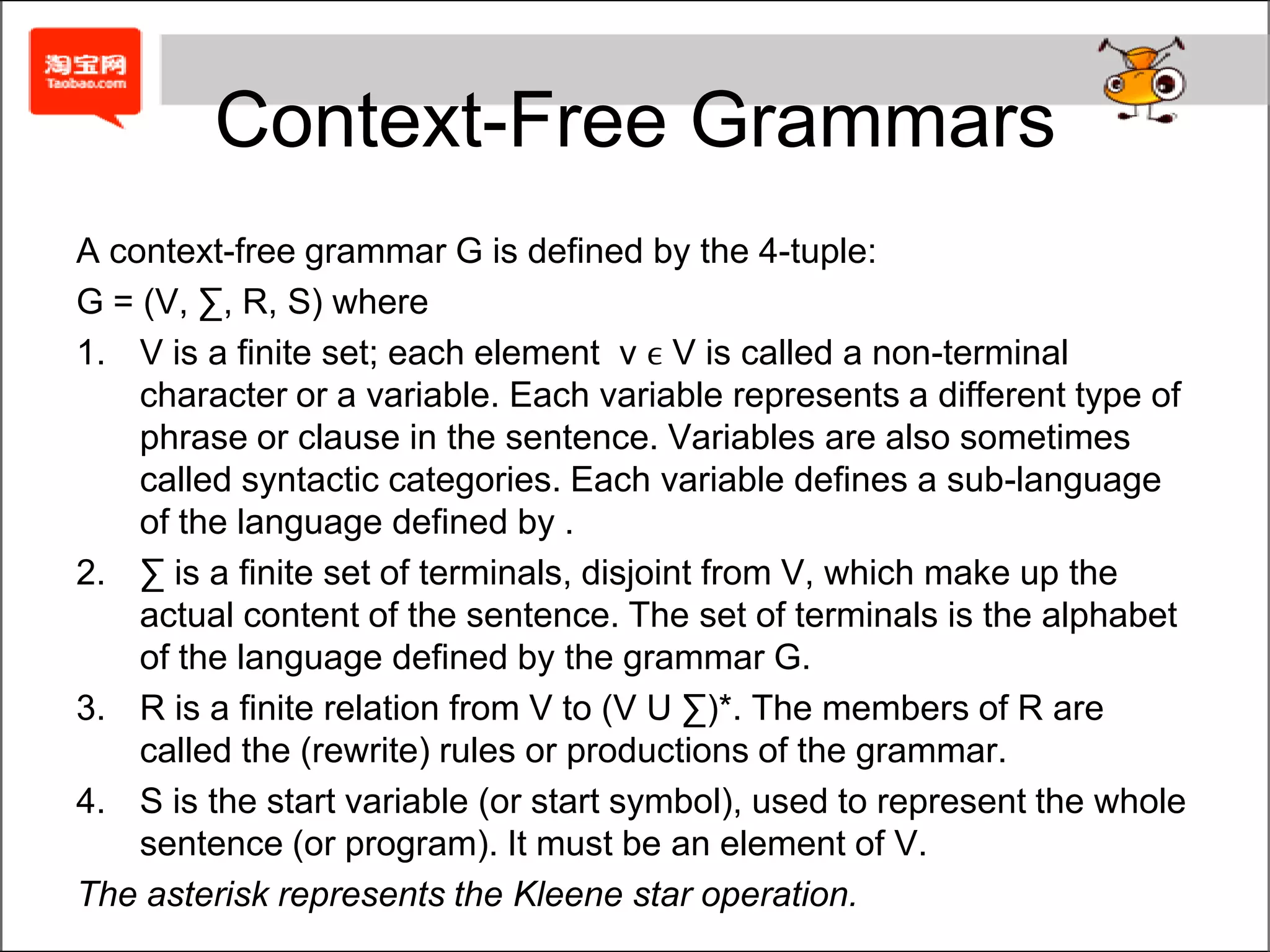

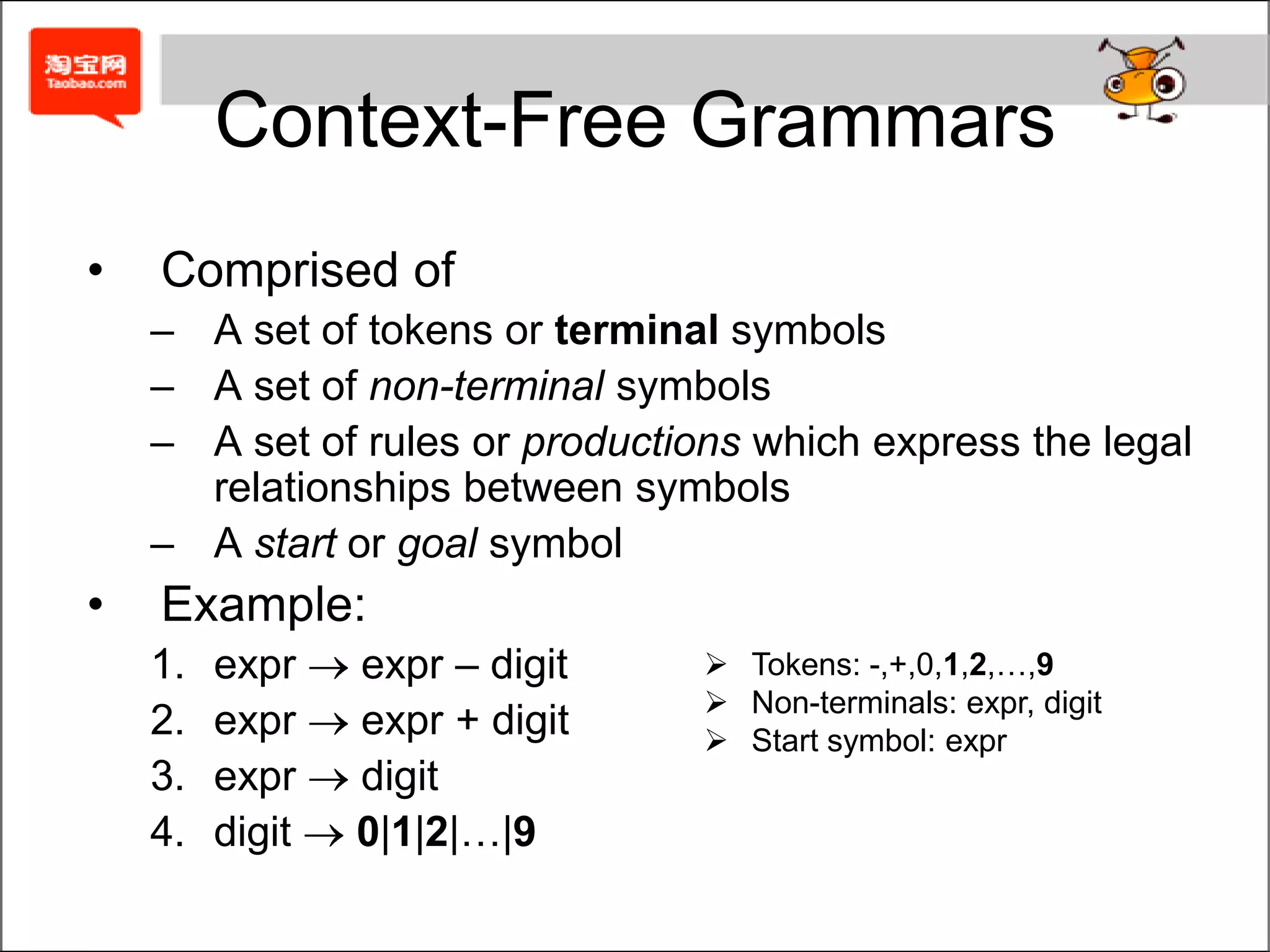

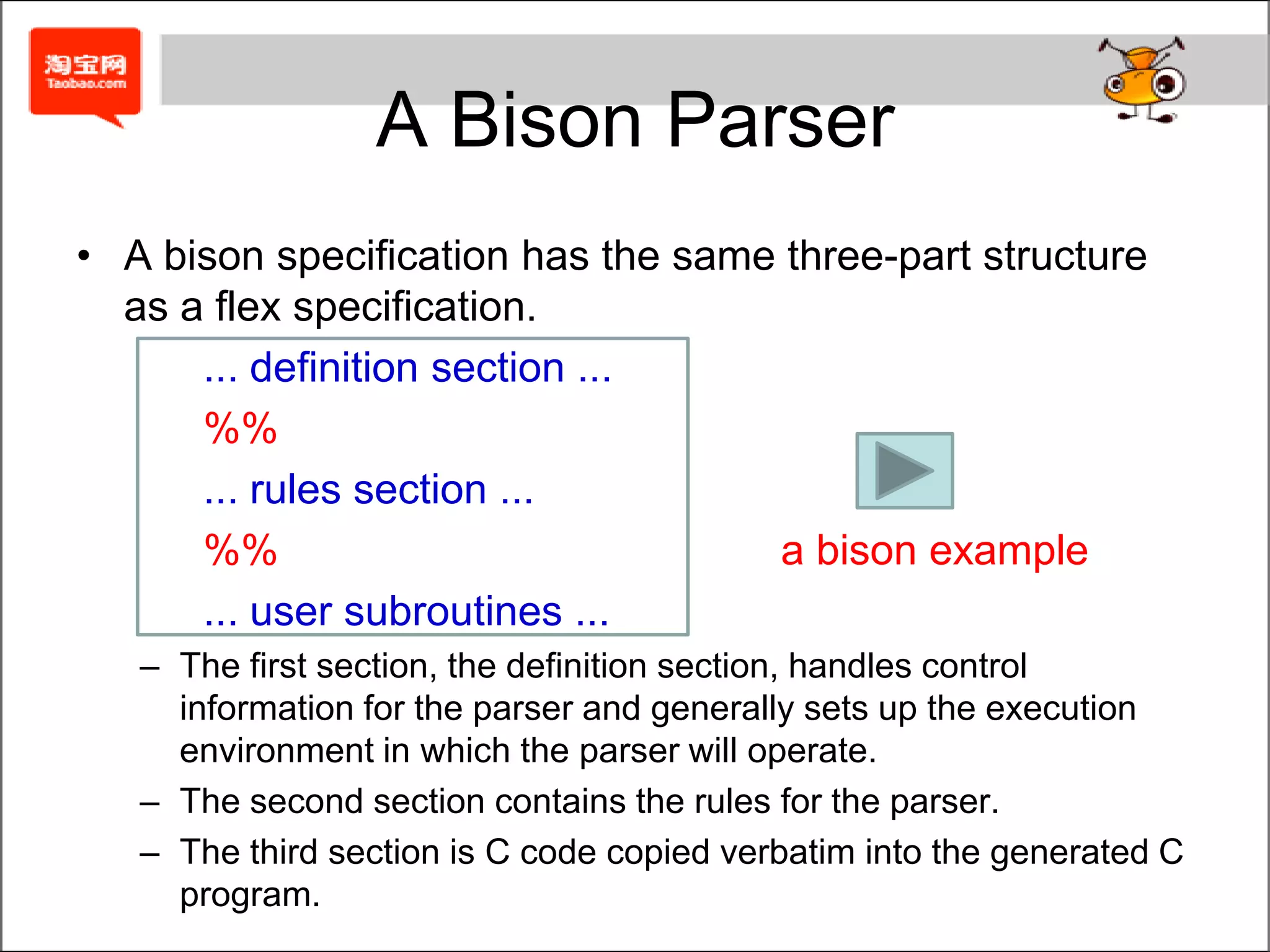

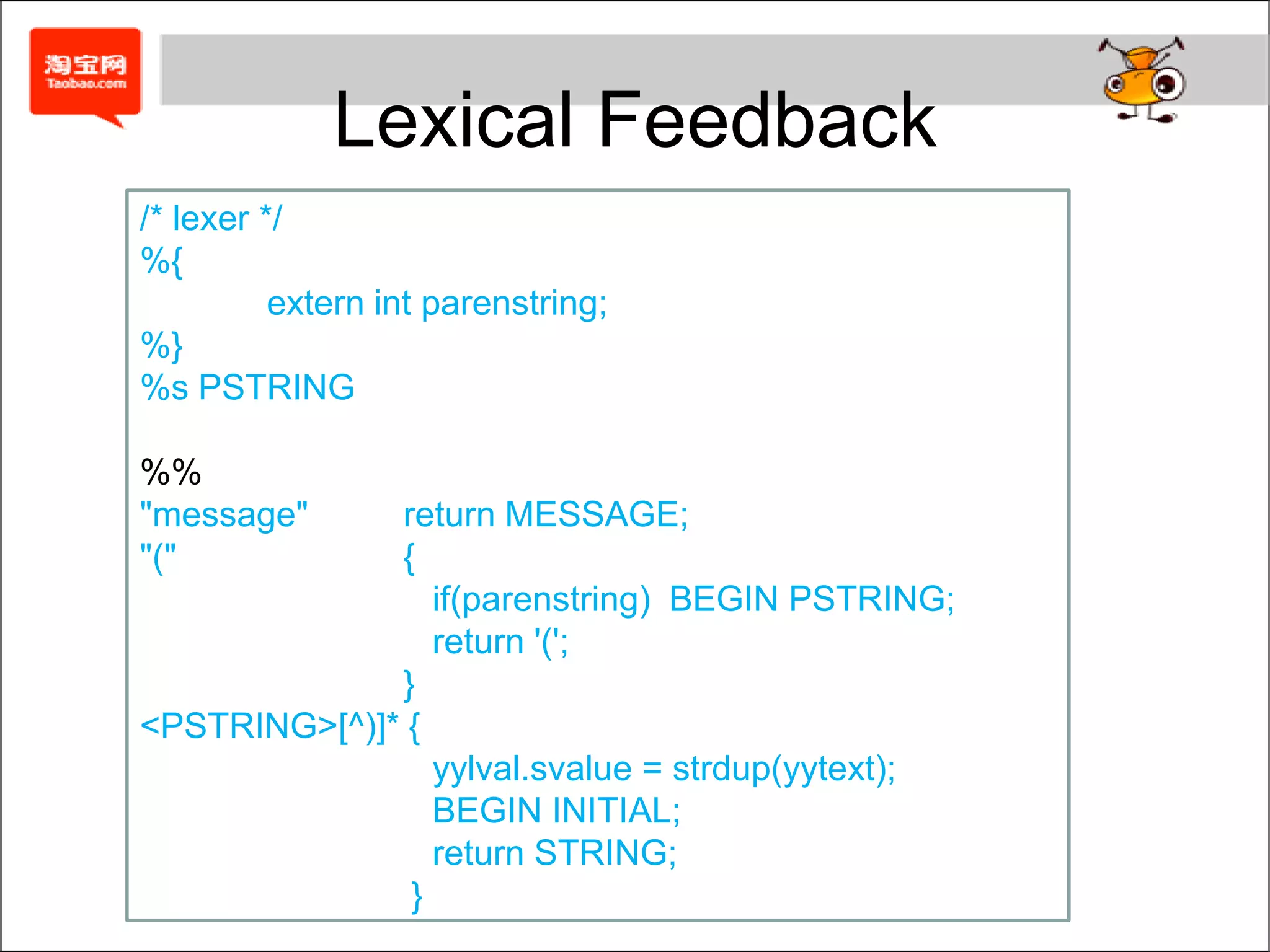

Flex is used for recognizing regular expressions and dividing input streams into tokens. Bison is used for building programs that handle structured input by taking tokens from Flex and grouping them logically based on context-free grammars.

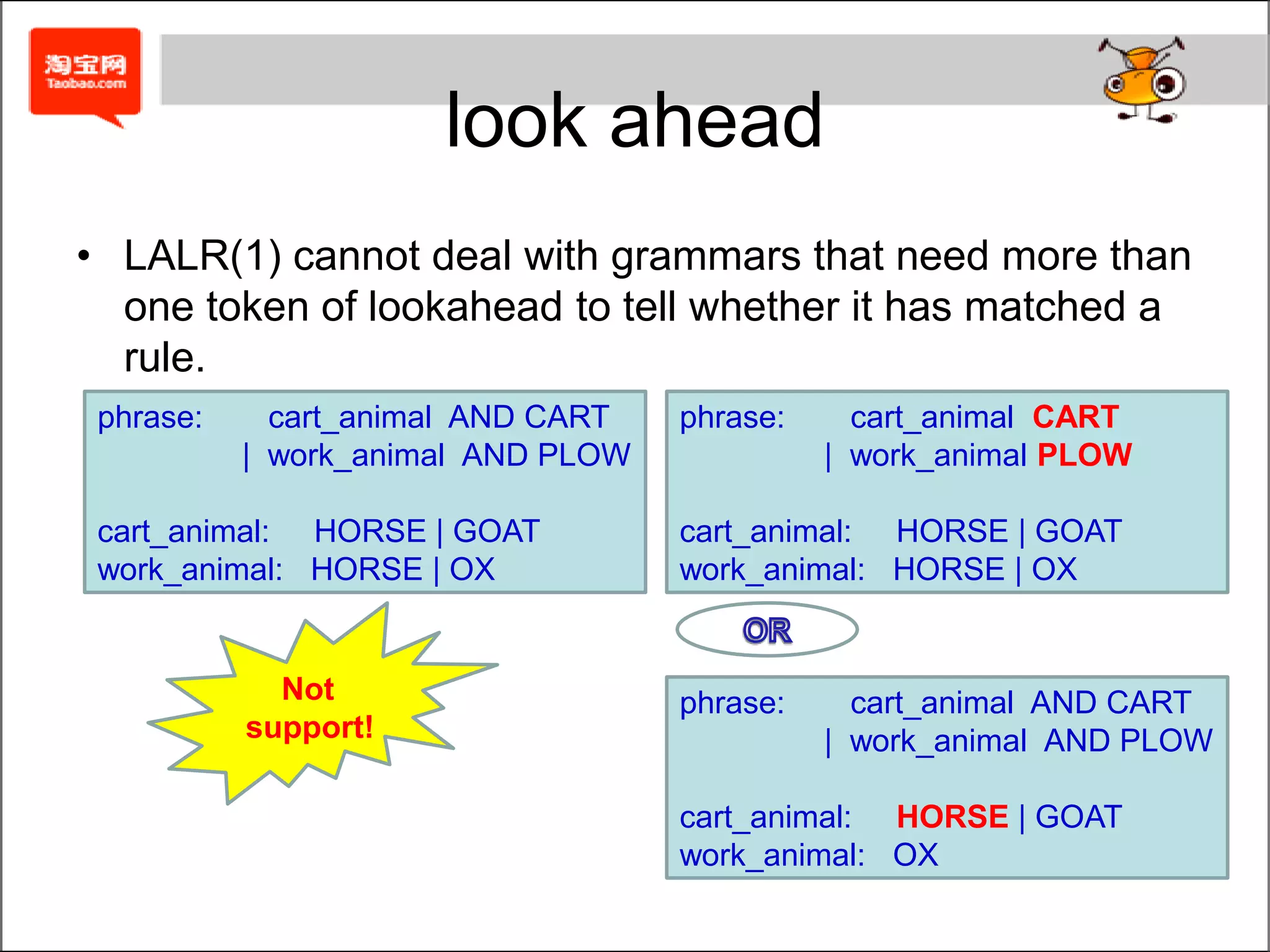

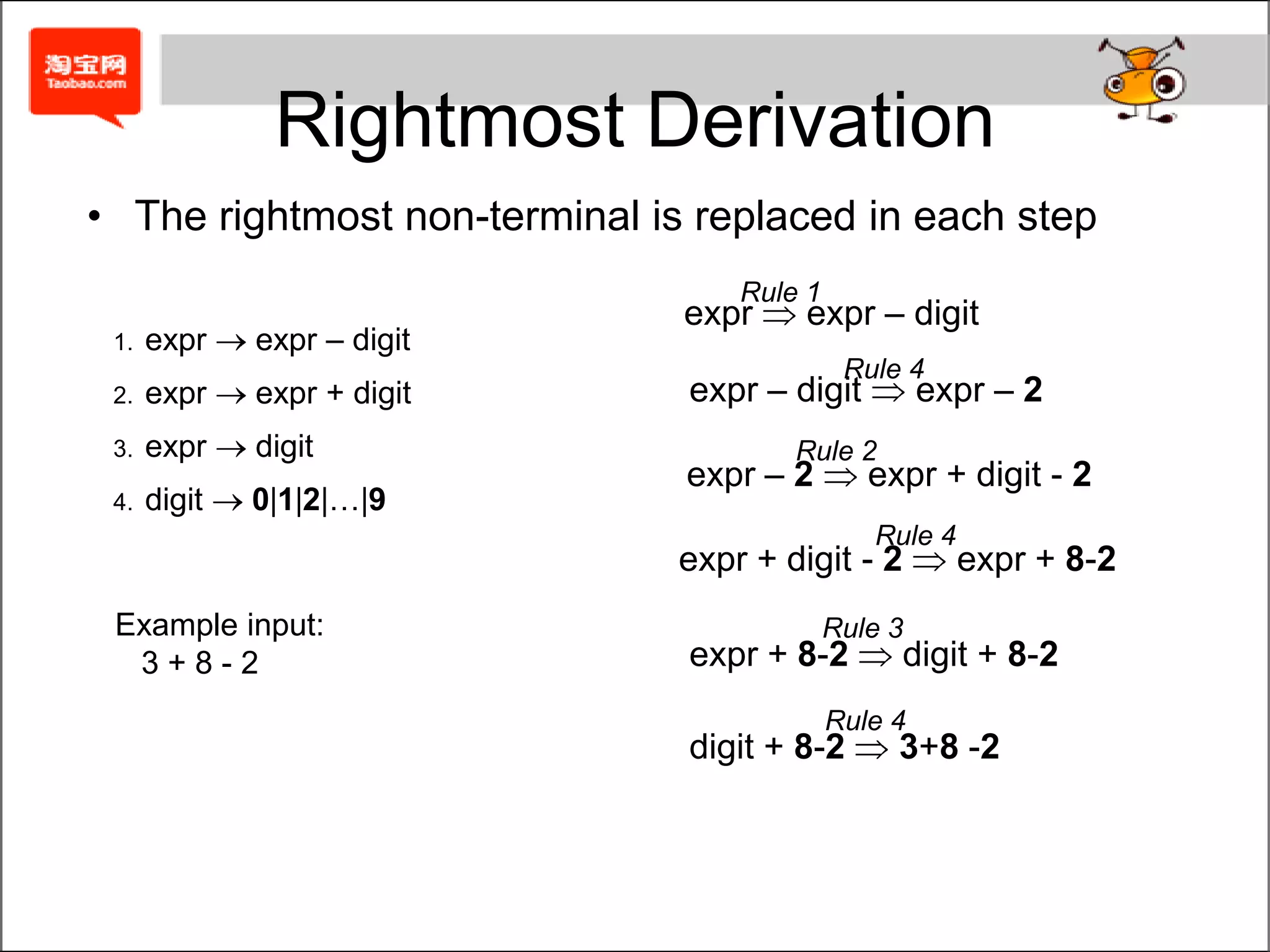

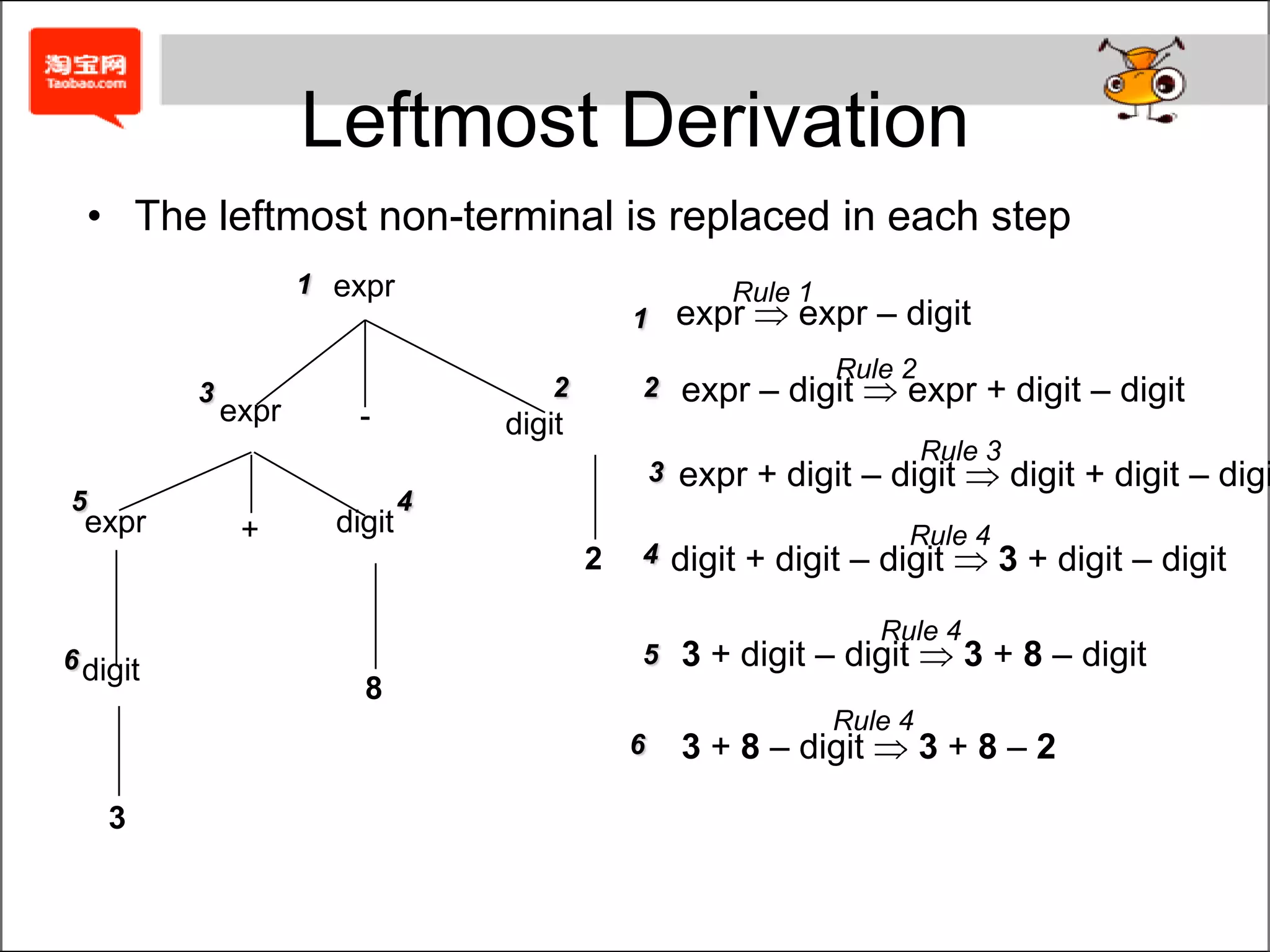

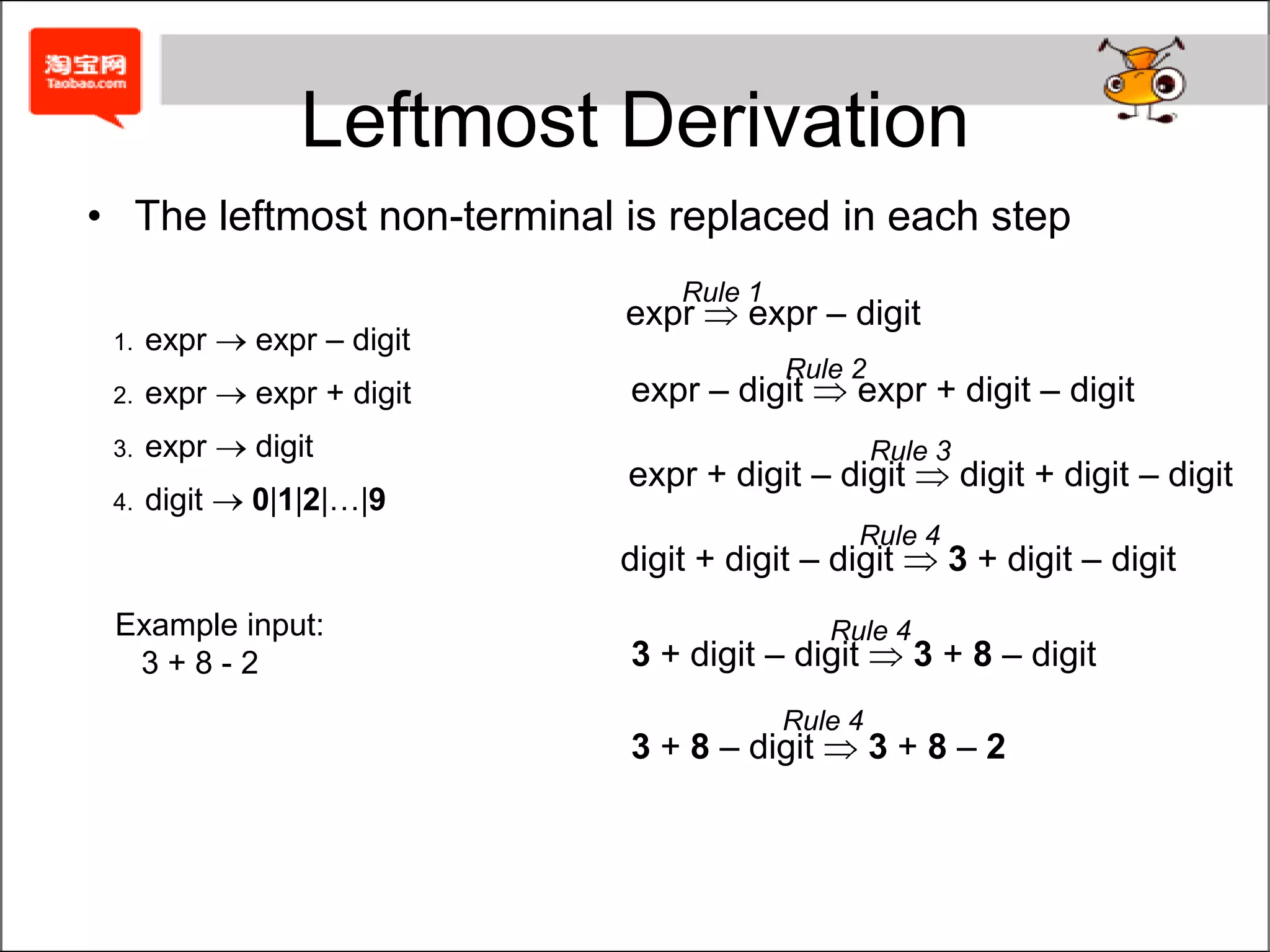

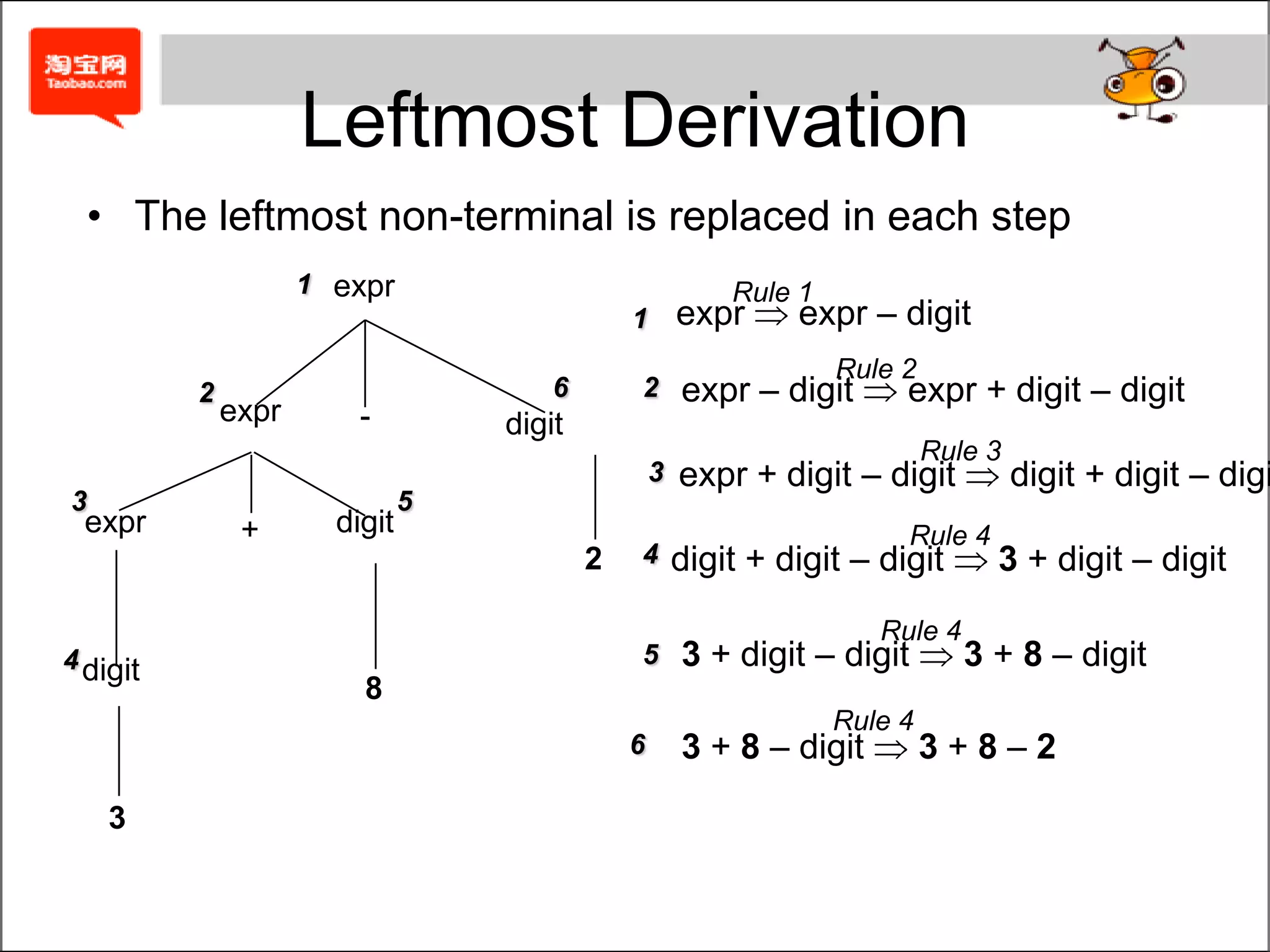

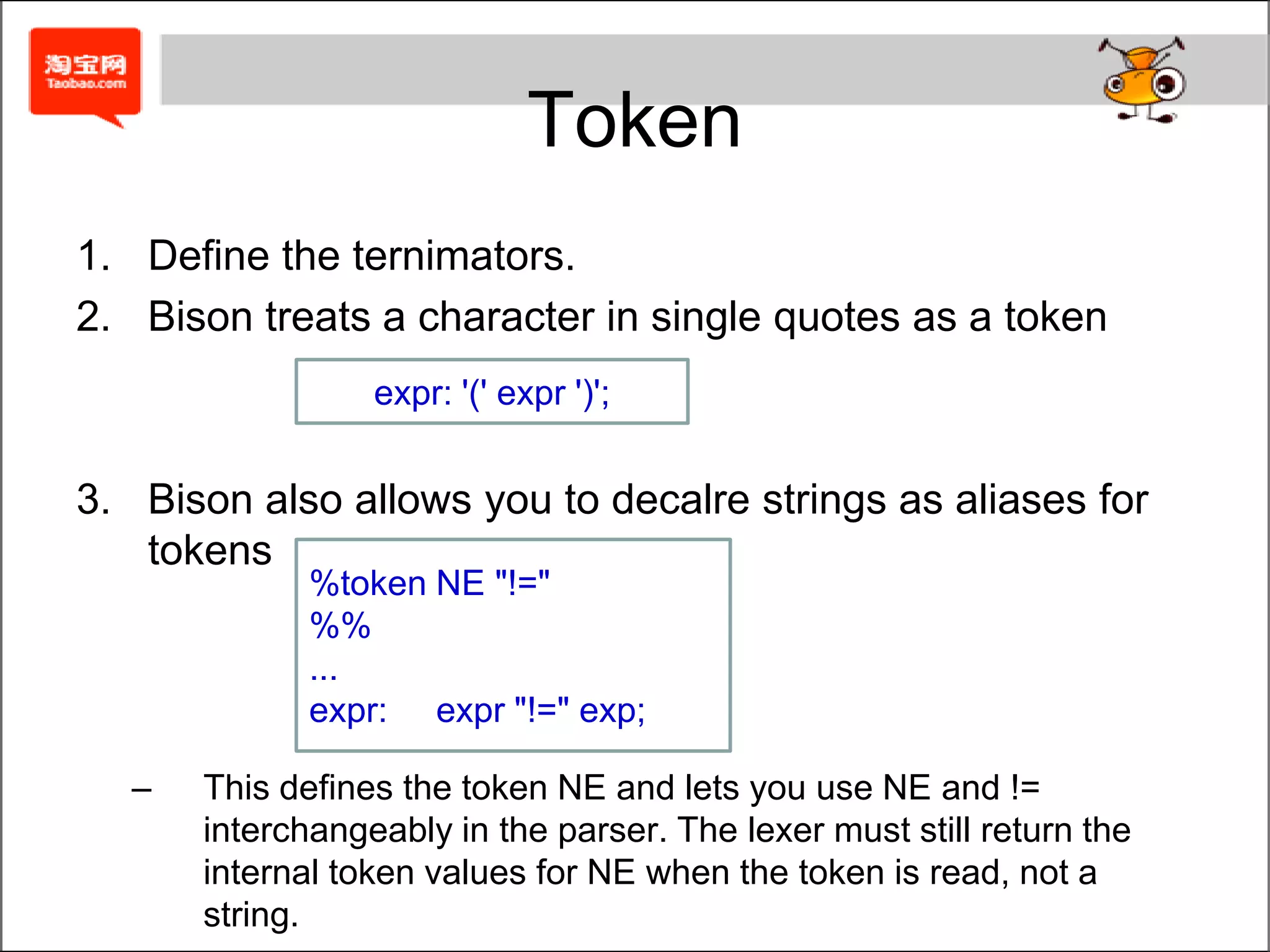

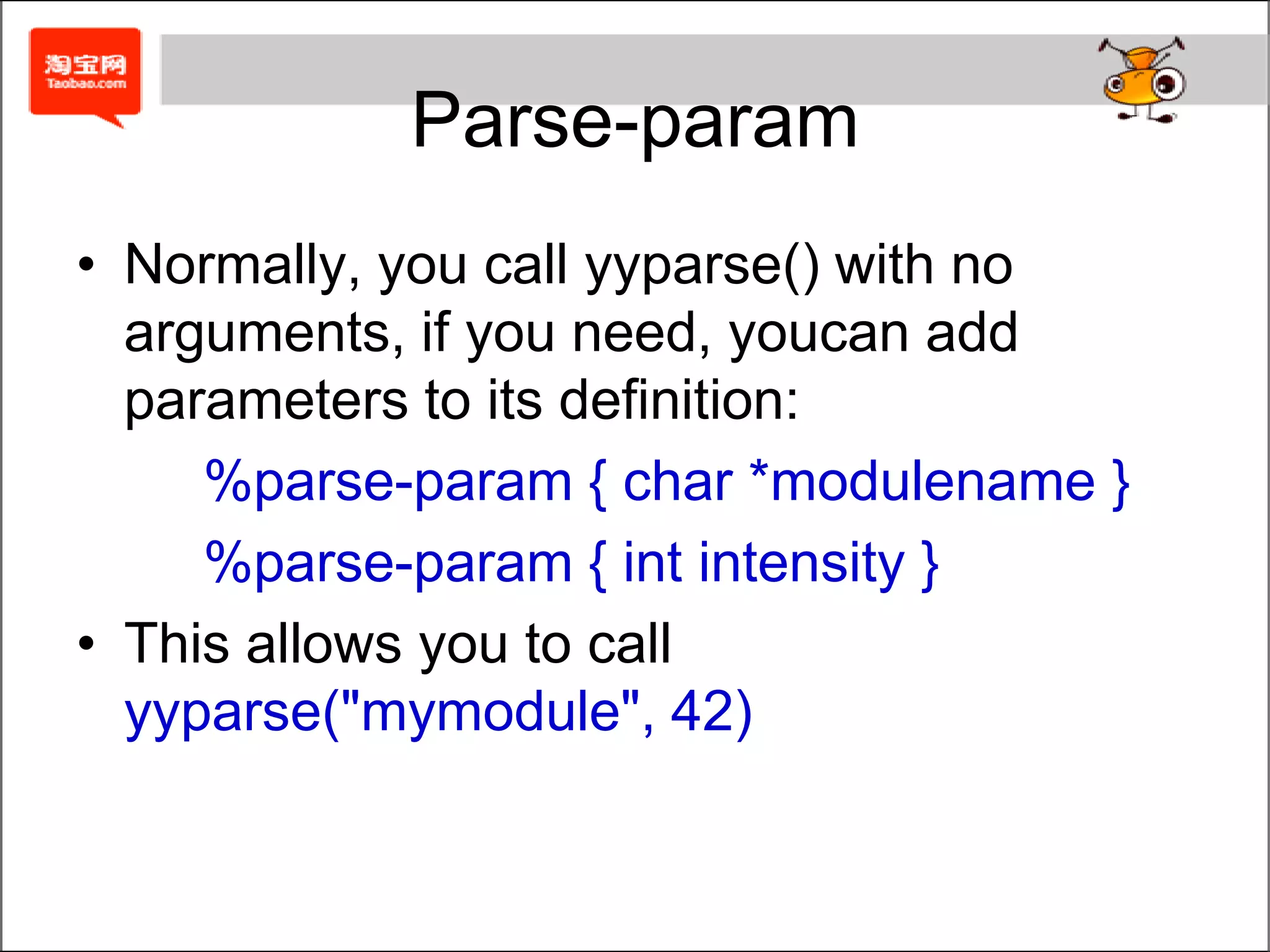

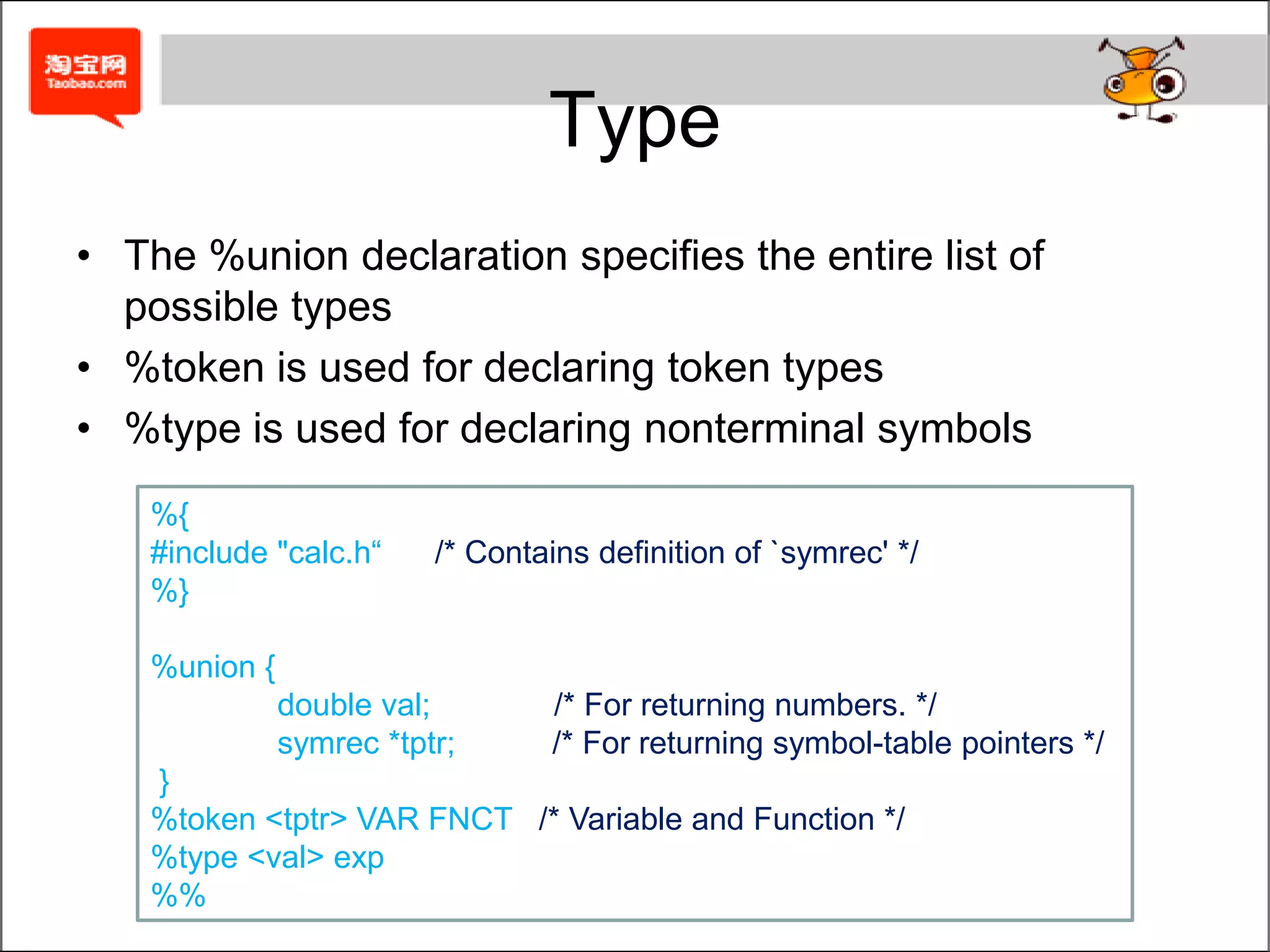

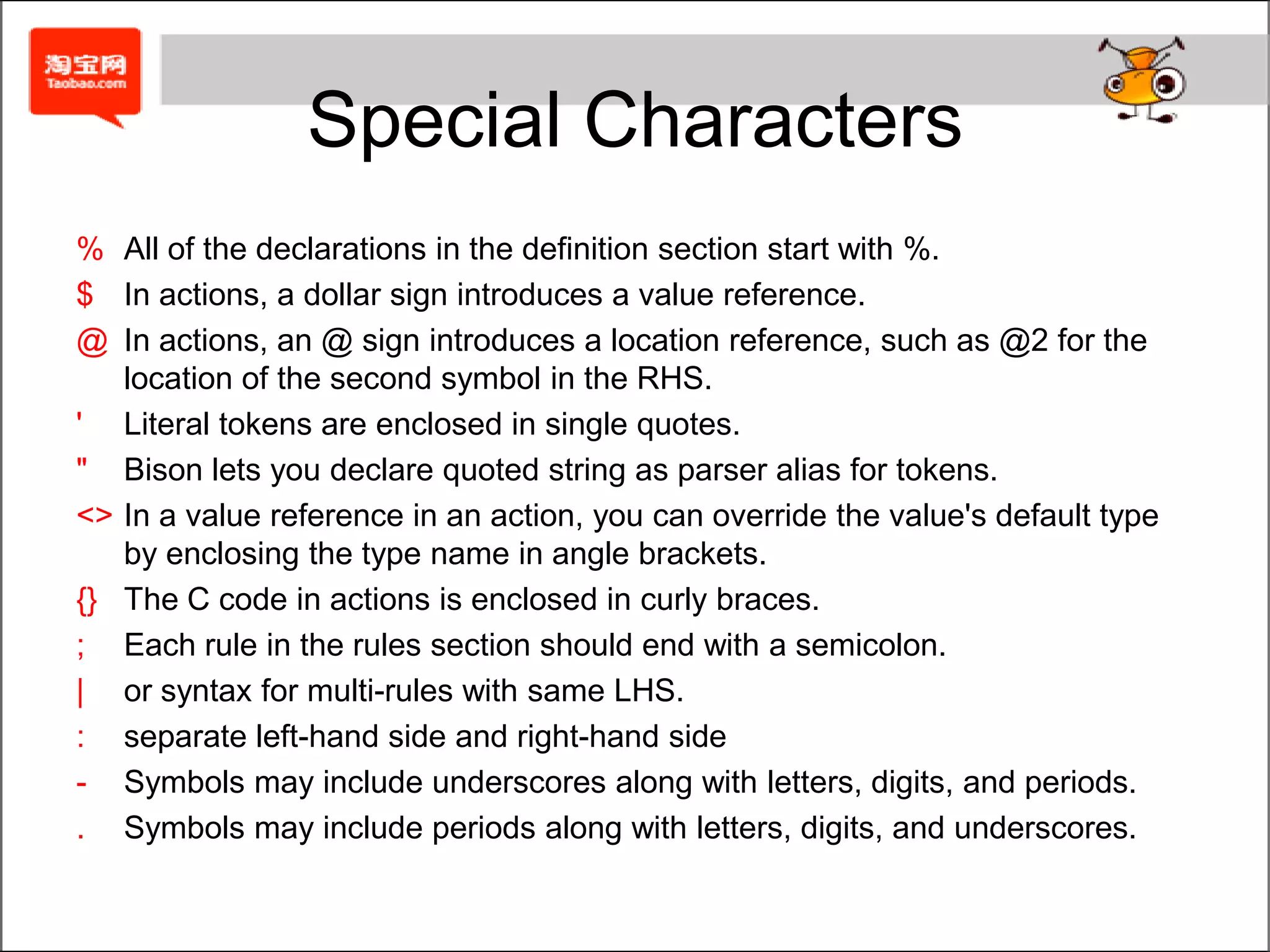

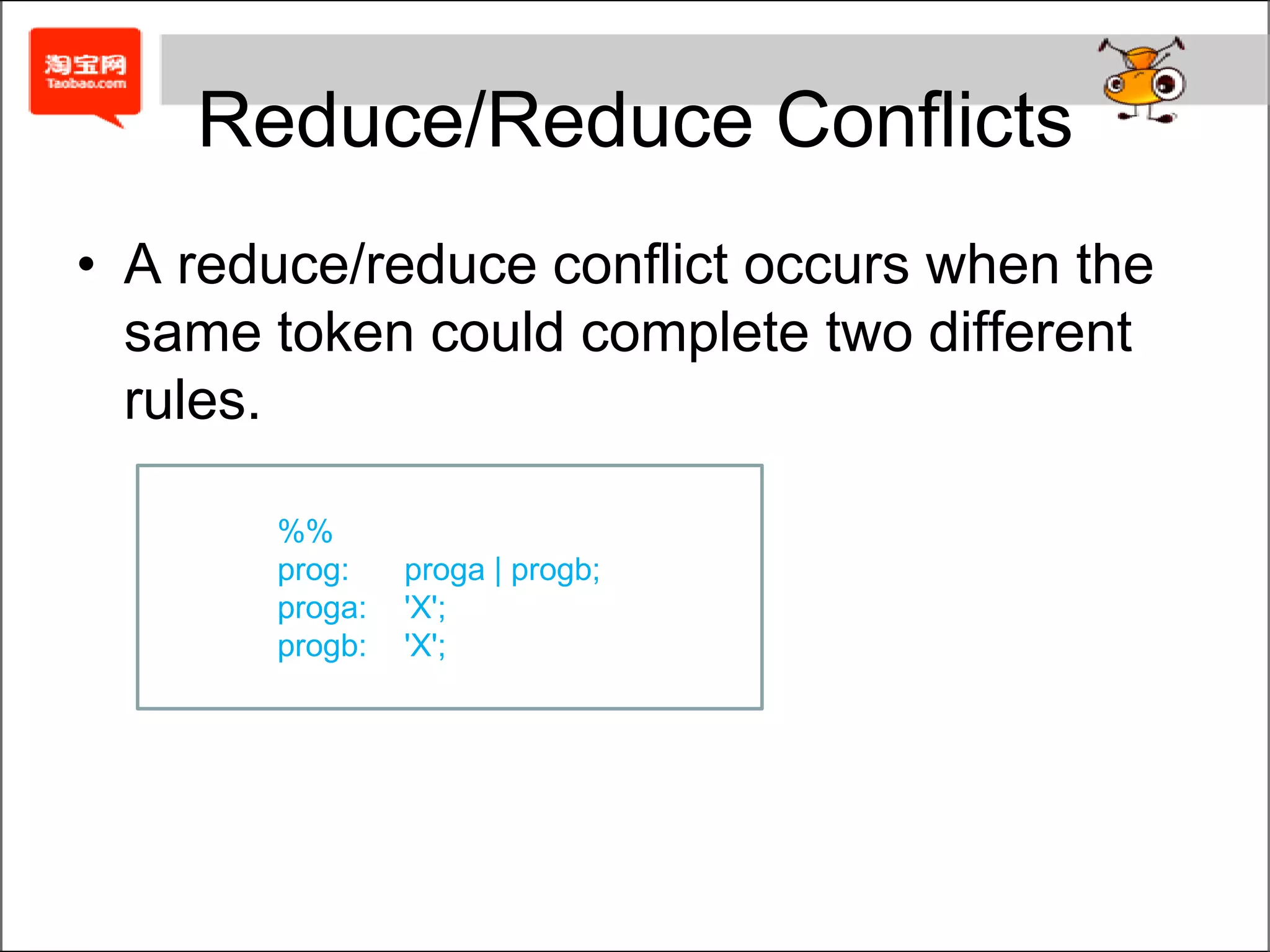

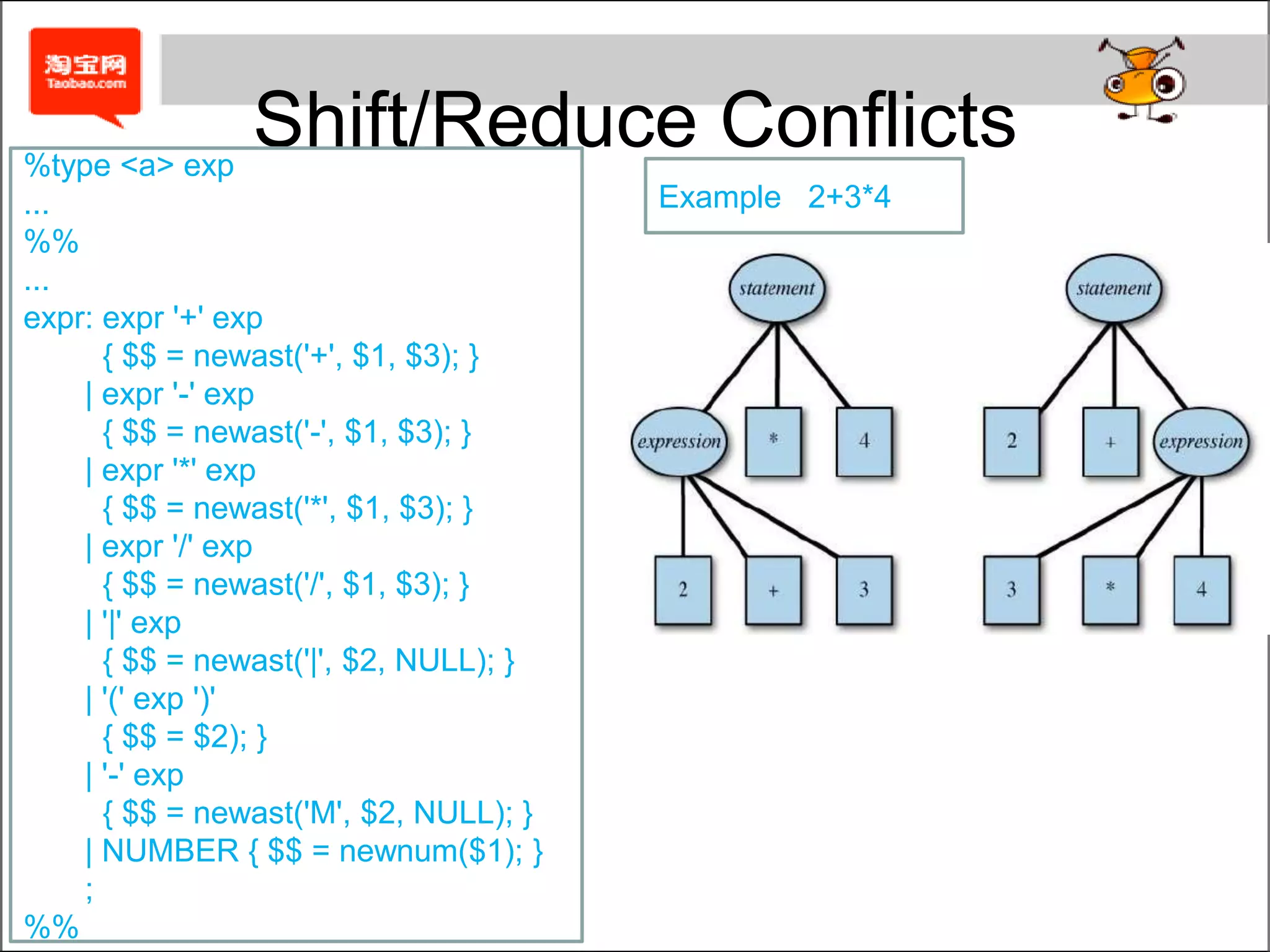

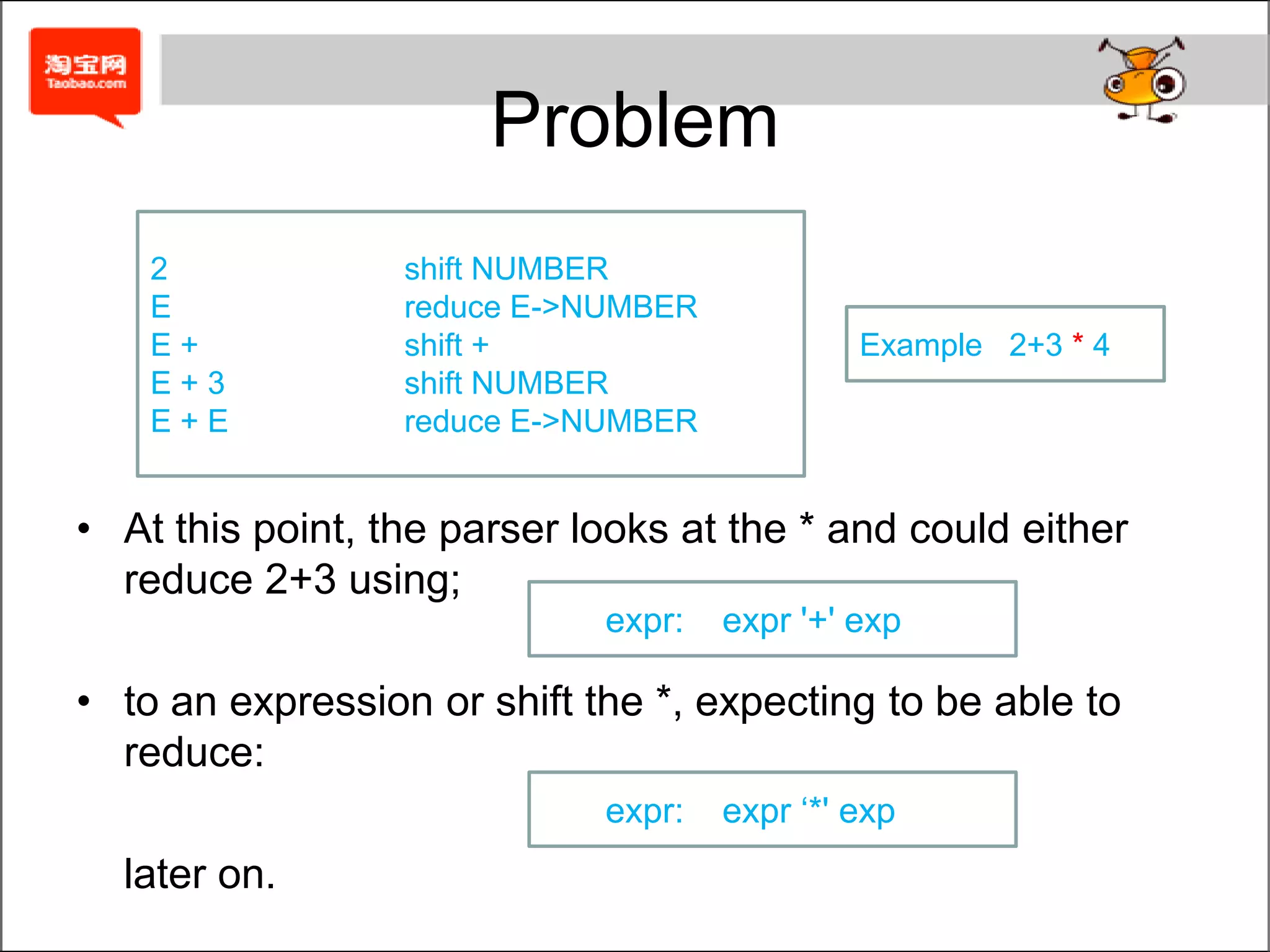

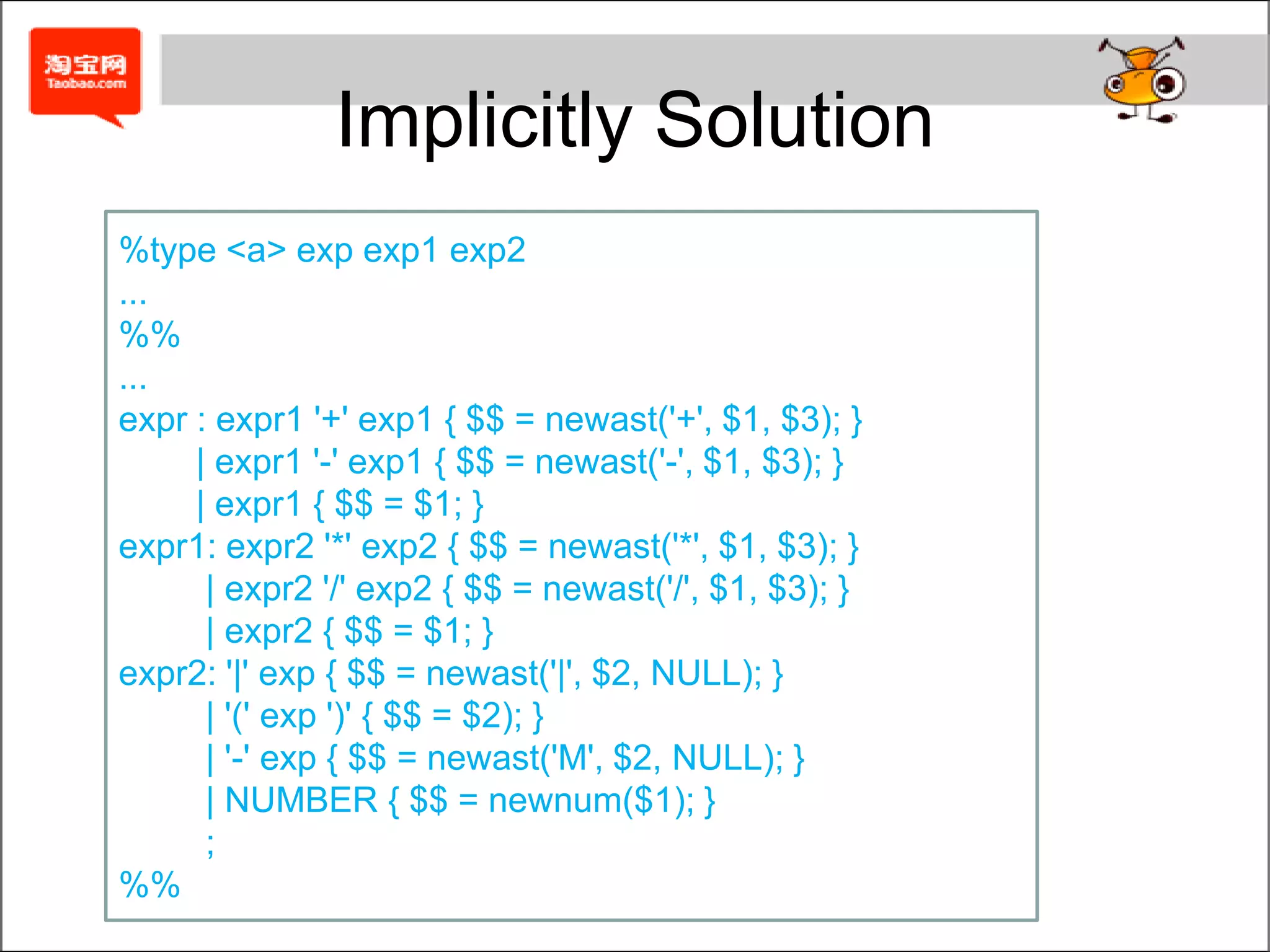

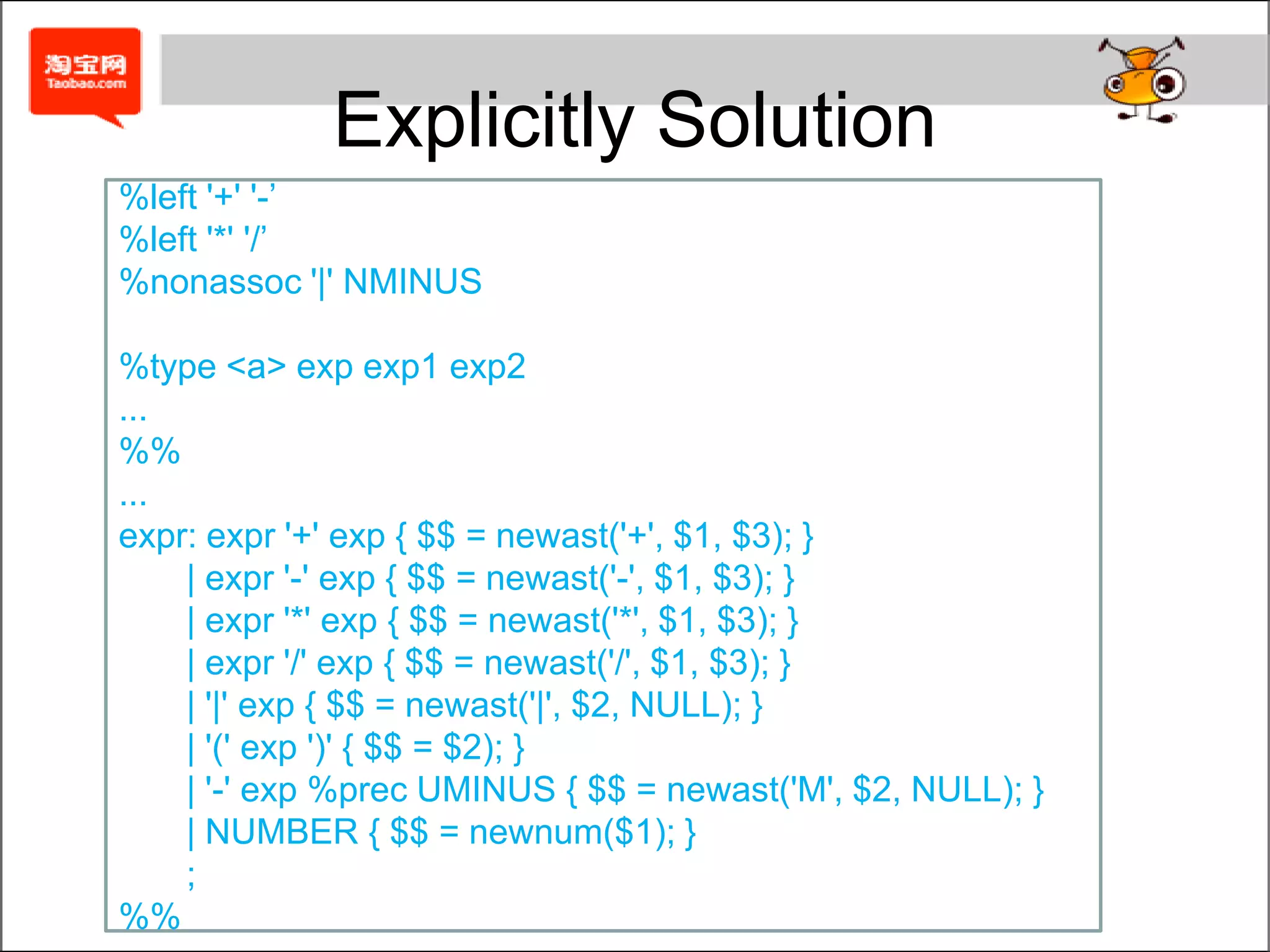

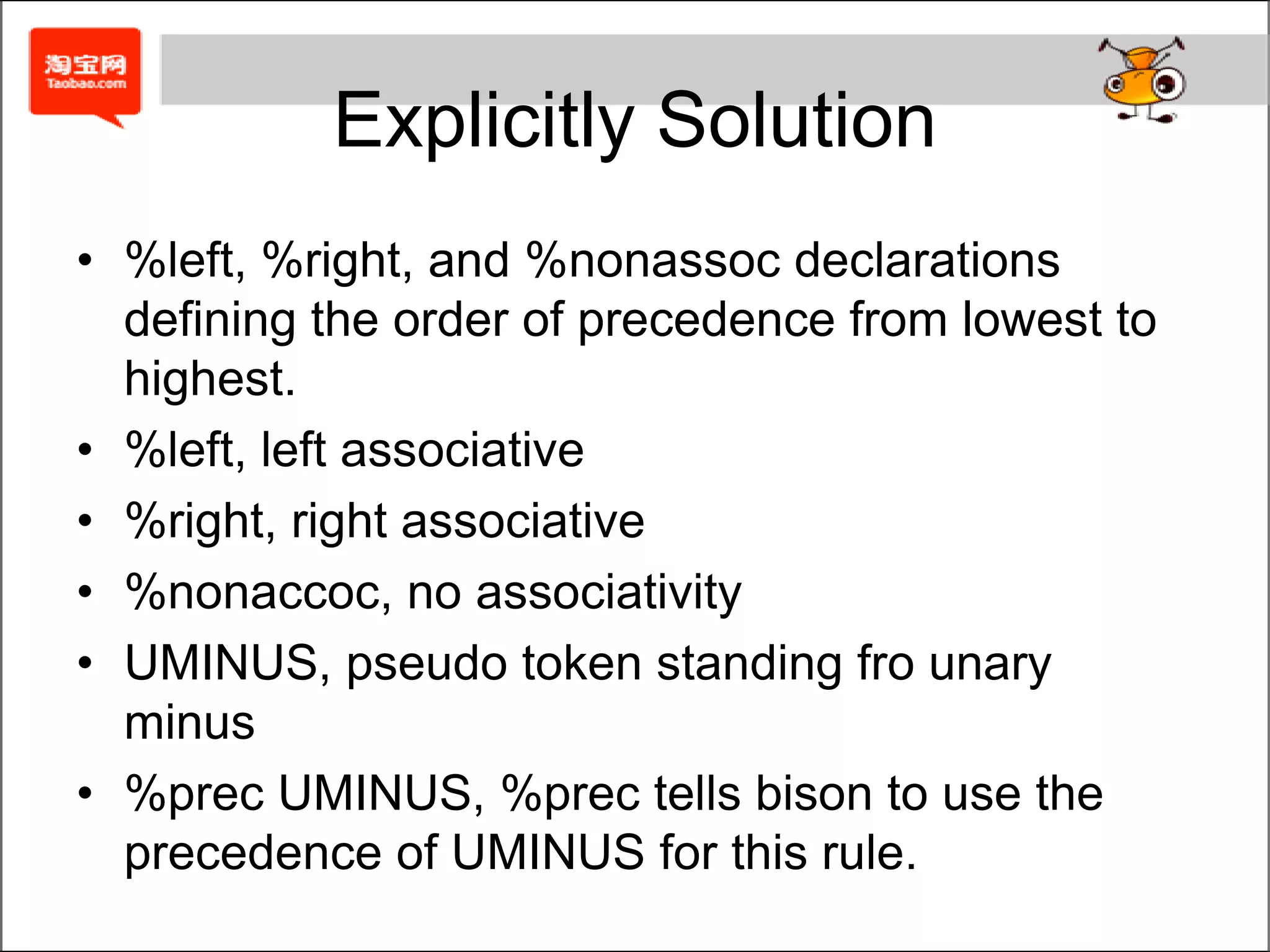

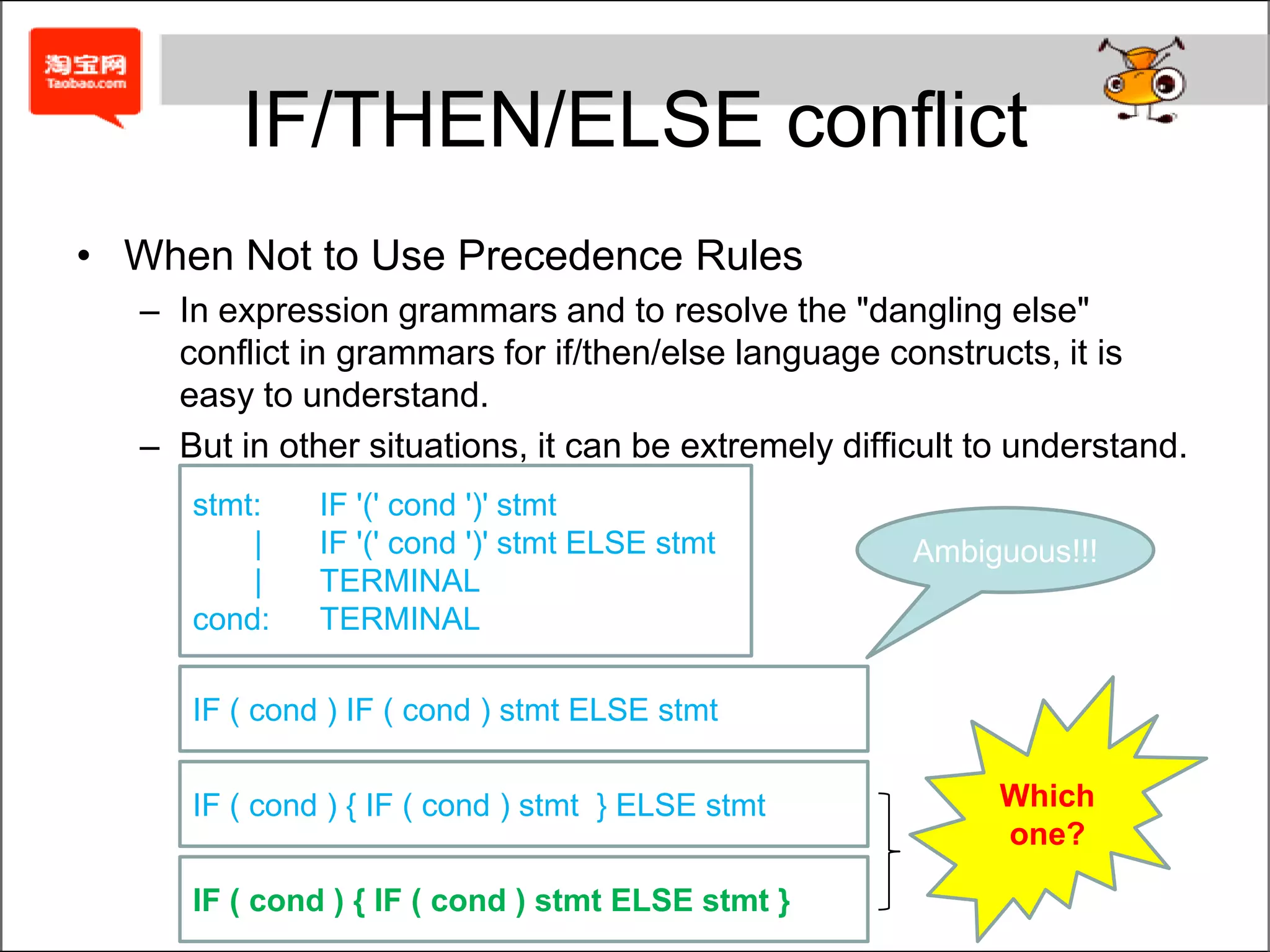

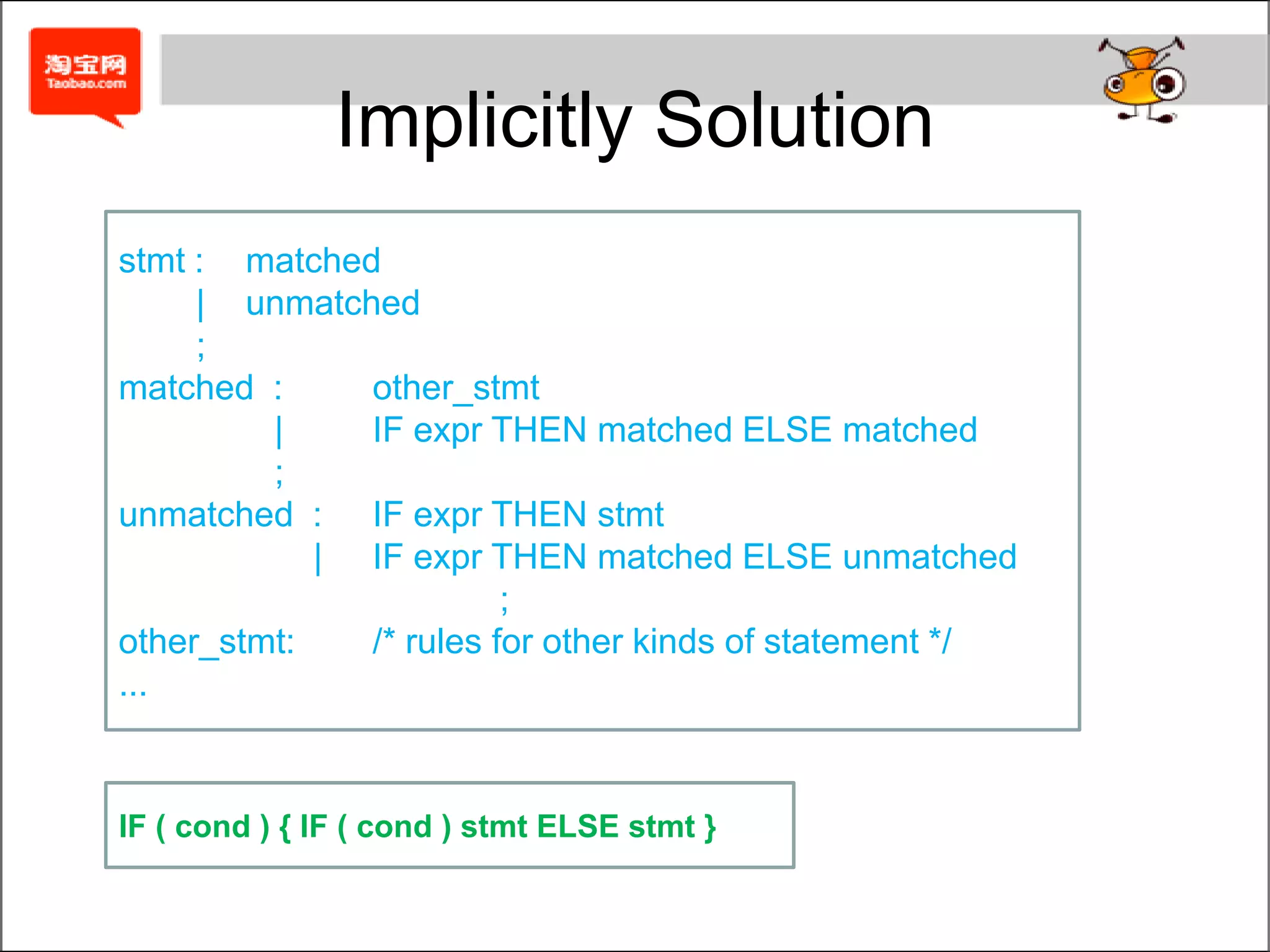

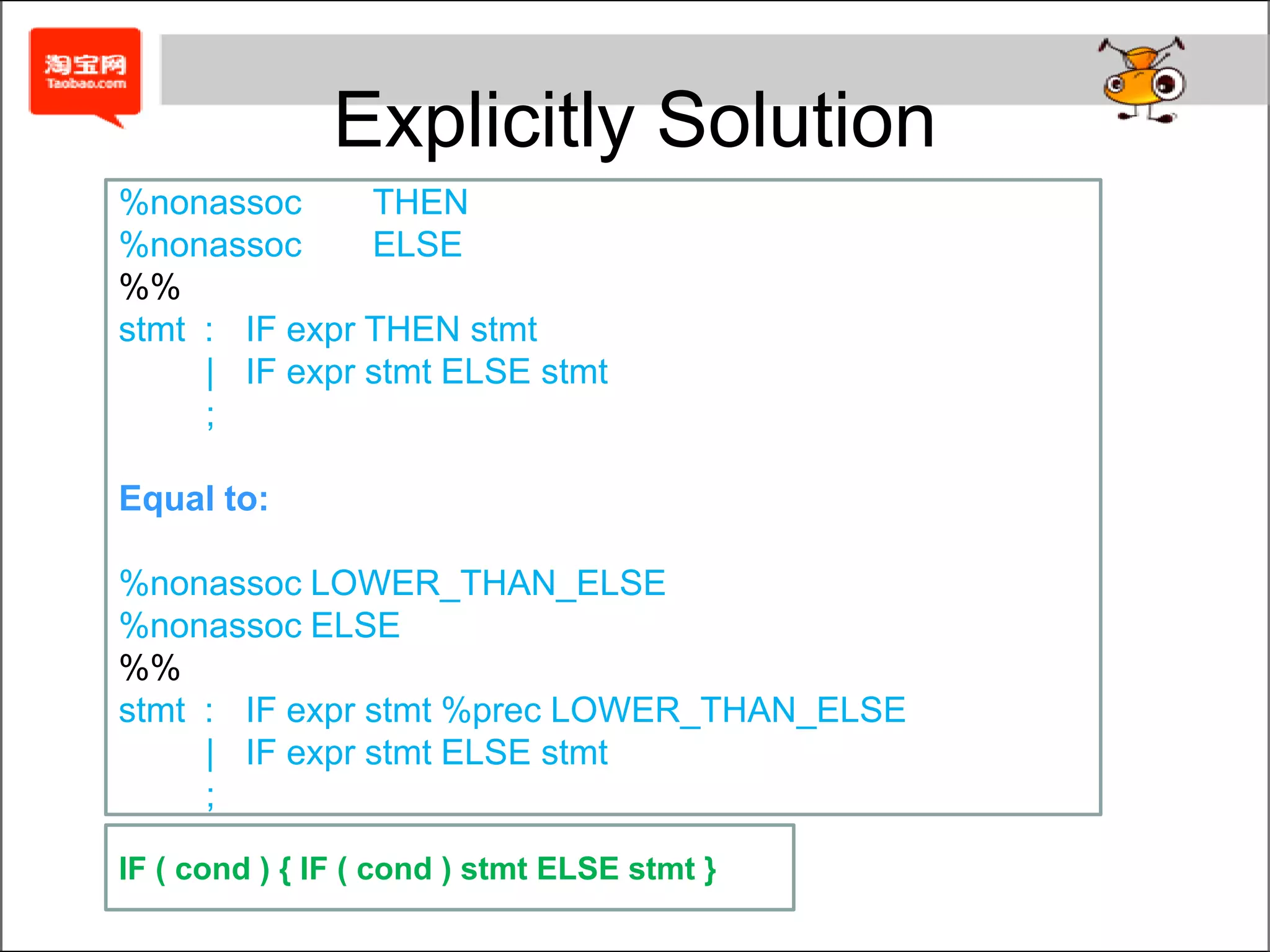

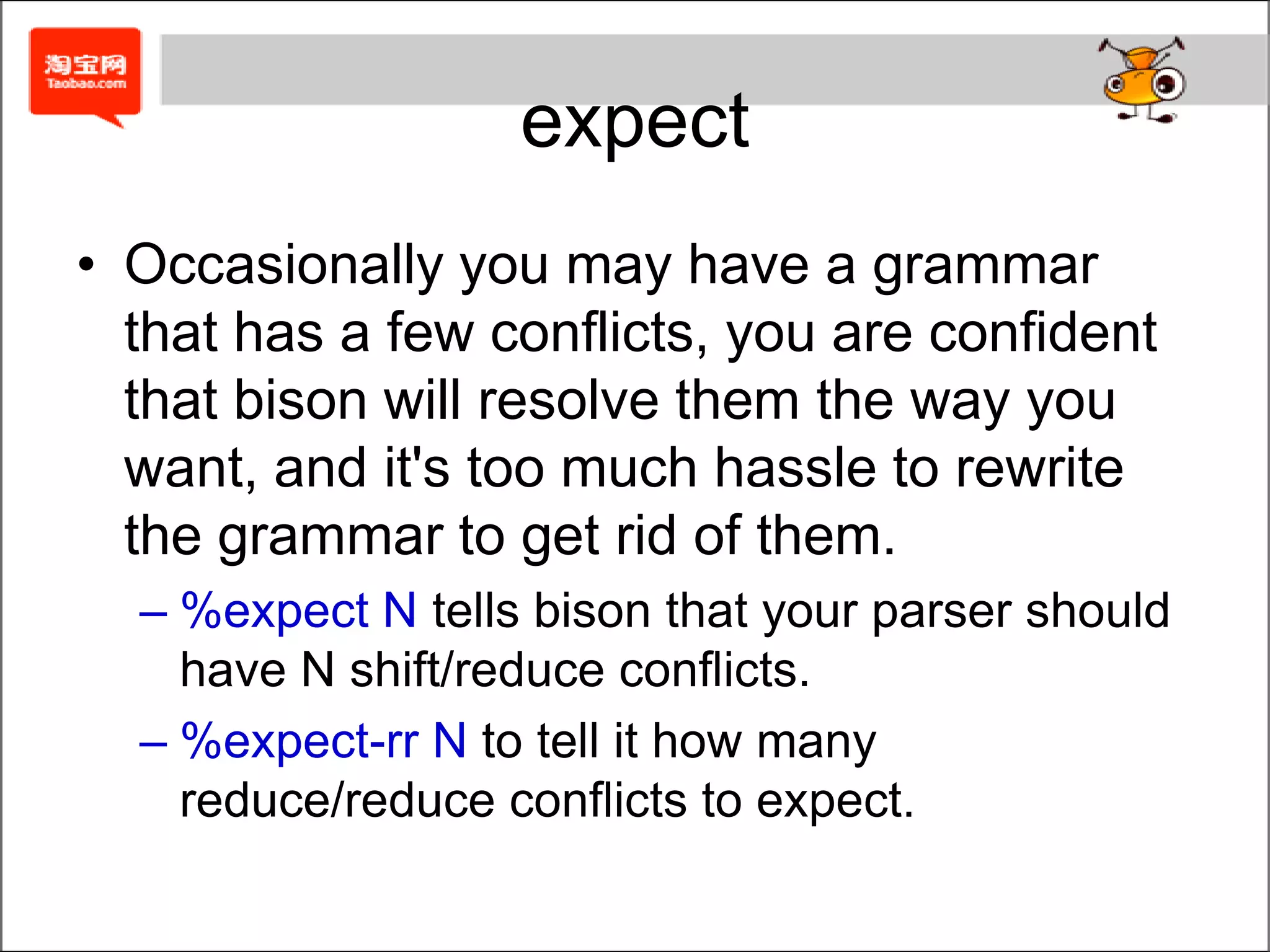

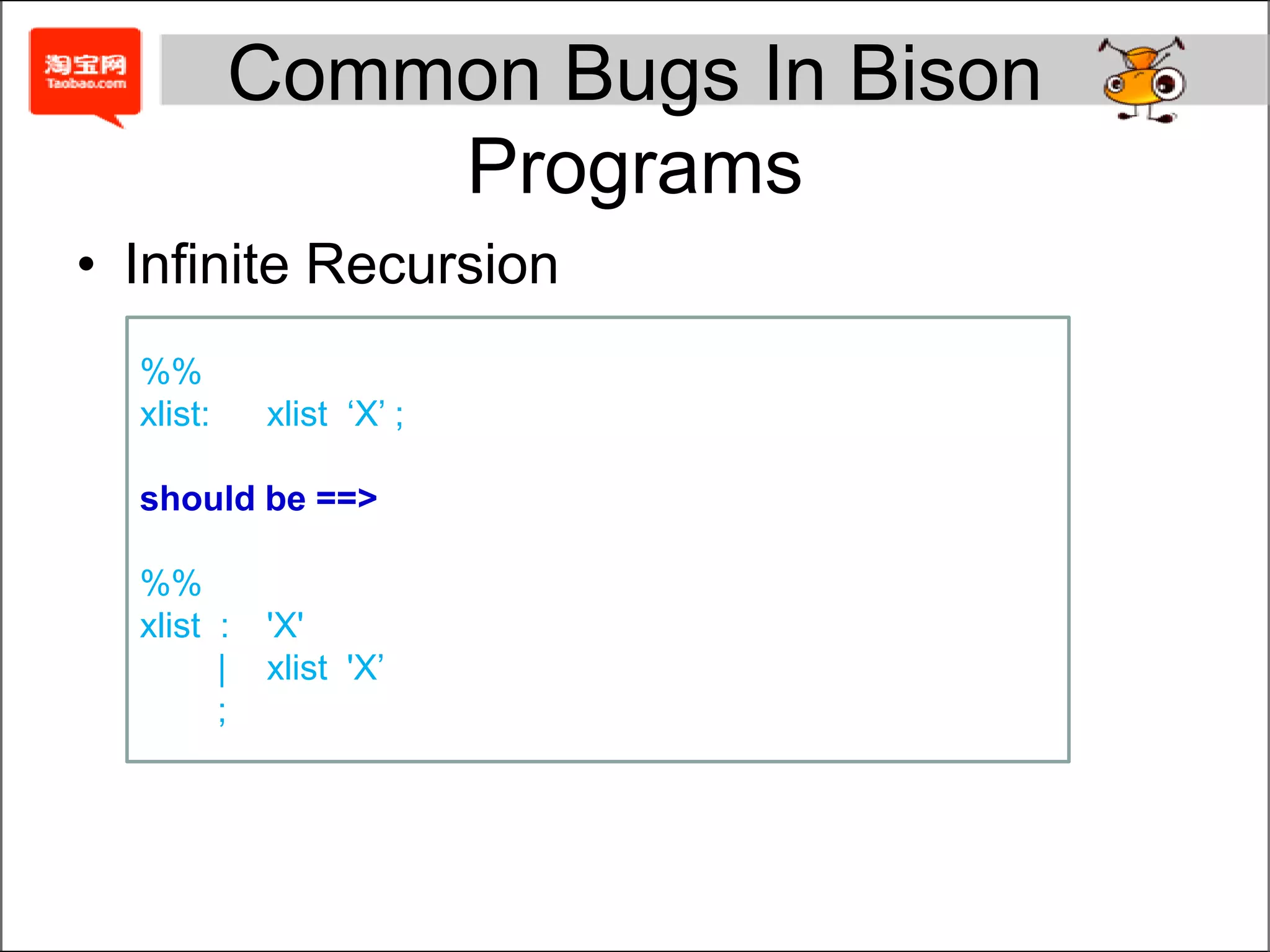

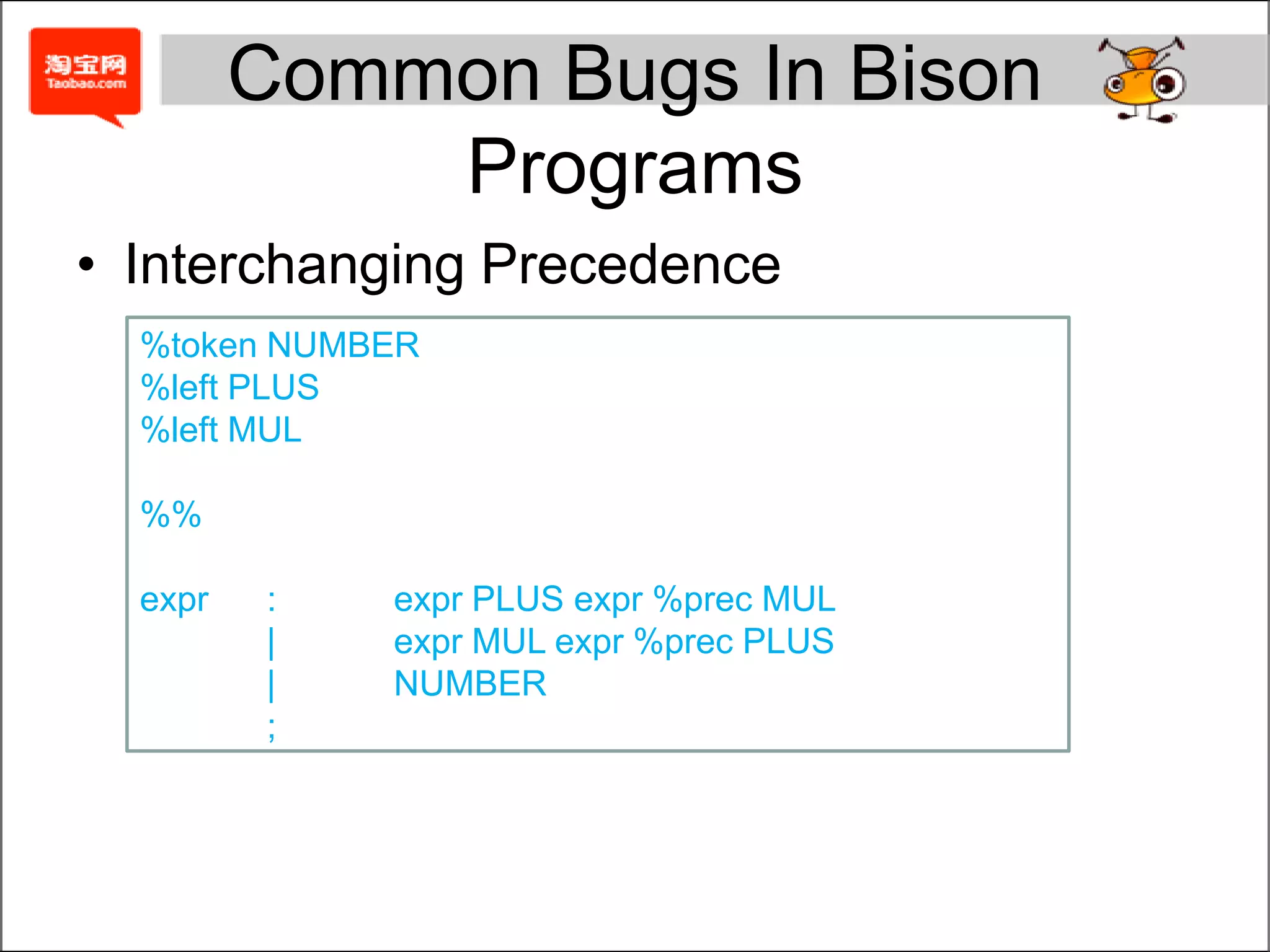

The document explains key concepts such as shift-reduce parsing, lookahead, leftmost and rightmost derivations, and how to specify grammars, tokens, types, rules and actions in a Bison specification to build a parser. It also covers ambiguity, conflicts and how precedence and associativity help resolve shift-reduce conflicts.

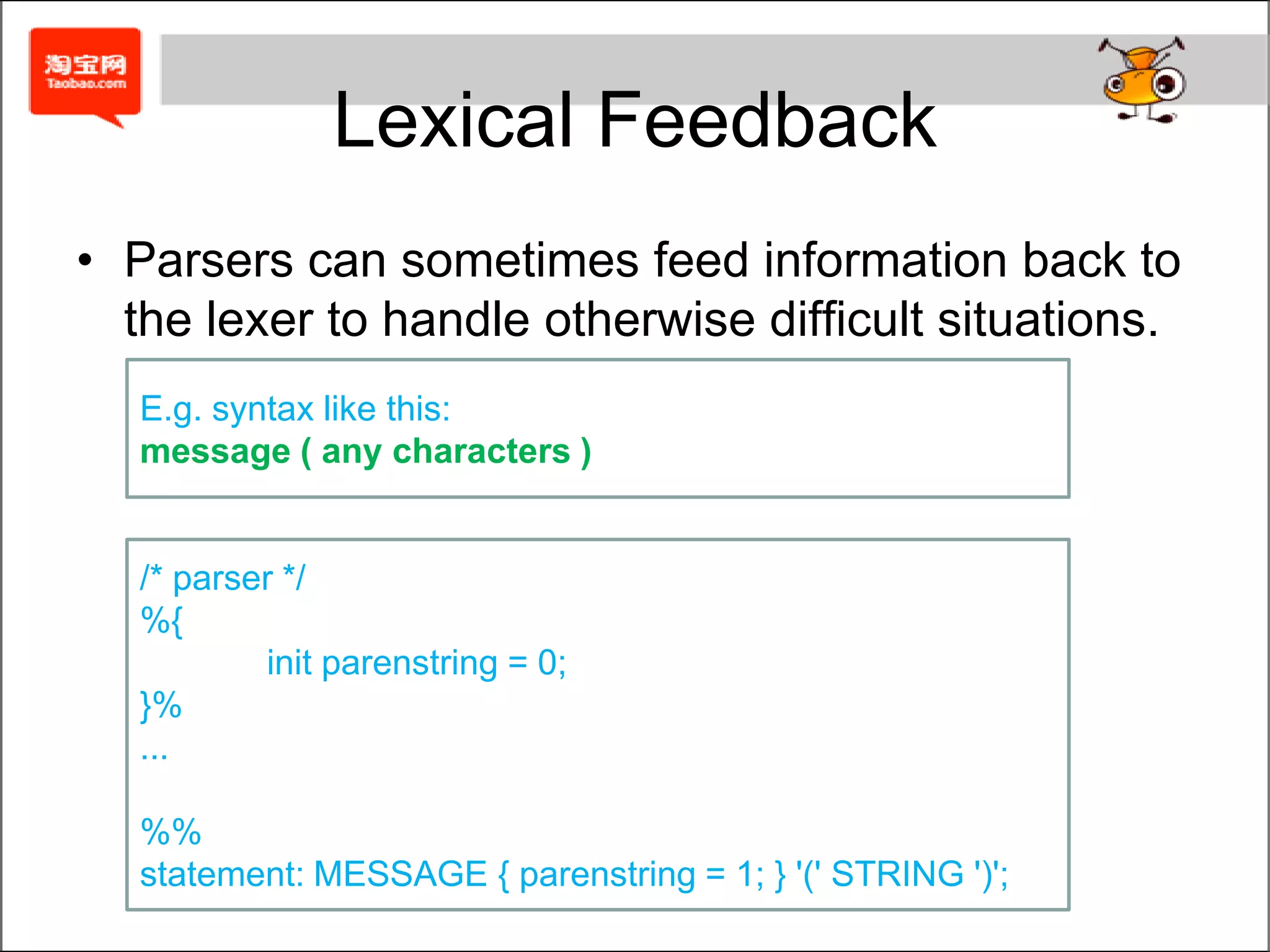

![Lexical Feedback/* lexer */%{ extern int parenstring;%}%s PSTRING%%"message" return MESSAGE;"(" { if(parenstring) BEGIN PSTRING; return '('; }<PSTRING>[^)]* { yylval.svalue = strdup(yytext); BEGIN INITIAL; return STRING; }](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductionofbison-110922020230-phpapp01/75/Introduction-of-bison-44-2048.jpg)