Gaussian Multiplicative Chaos (GMC) is a canonical construction that turns a sufficiently regular Gaussian field into a random measure of the form exp (γX(x)) dx,where X is a log-correlated Gaussian field. The theory originates in the work of Kahane on

multiplicative chaos and random measures [1], and has since evolved into a central tool at the intersection of probability theory, mathematical physics, and fractal geometry

![7 GMC in mathematical physics 10

7.1 Liouville quantum gravity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

7.2 KPZ relation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

7.3 Liouville conformal field theory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

8 GMC, stochastic PDEs, and KPZ-type structures 11

8.1 Stochastic heat equation and KPZ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

8.2 SPDE-based approximations to GMC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

8.3 Renormalization and regularity structures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

8.4 A schematic SPDE–GMC diagram . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

9 GMC, Markov random fields, and exponential tilts 12

9.1 Gaussian Markov random fields and log-correlated limits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

9.2 Exponential tilts and Gibbs measures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

9.3 DLR equations and infinite-volume limits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

9.4 A simple factor-graph style diagram . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

10 GMC and holographic analogies (conservative viewpoint) 13

10.1 Boundary fields and bulk geometries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

10.2 Liouville CFT and AdS3/CFT2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

10.3 Boundary random measures and bulk observables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

10.4 A schematic holographic diagram . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

11 Random matrices and analytic number theory 14

11.1 Characteristic polynomials of random unitary matrices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

11.2 Random Hermitian matrices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

11.3 Riemann zeta function . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

12 GMC in turbulence and finance 15

12.1 Kolmogorov–Obukhov model and intermittency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

12.2 Financial time series and volatility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

13 Open problems and further directions 15

1 Introduction

Gaussian Multiplicative Chaos (GMC) is a canonical construction that turns a sufficiently regular

Gaussian field into a random measure of the form

eγX(x)

dx,

where X is a log-correlated Gaussian field. The theory originates in the work of Kahane on

multiplicative chaos and random measures [1], and has since evolved into a central tool at the

intersection of probability theory, mathematical physics, and fractal geometry.

The basic phenomenon is that many models in analysis and physics involve Gaussian fields

whose covariance diverges logarithmically at short distances. These fields do not admit pointwise

values. Nevertheless, one can regularize them and consider exponentials of the form

exp

γXε(x) −

γ2

2

E[Xε(x)2

]

,

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-2-2048.jpg)

![and then study the limit as the regularization scale ε → 0. When this limit exists and is non-trivial,

one obtains a random measure Mγ which is highly singular and exhibits multifractal behavior.

Gaussian multiplicative chaos now appears in a wide range of contexts: Liouville quantum

gravity and Liouville conformal field theory, random planar maps and KPZ-type relations, random

matrix theory, the Riemann zeta function, turbulence and intermittency, and models of multi-scale

volatility. There is also a deep structural connection with multiplicative cascades and branching

random walks.

The purpose of this article is to give a survey-style overview of:

• the construction and phase diagram of Gaussian multiplicative chaos,

• the main structural and multifractal properties of GMC measures,

• applications in probability, analysis, and mathematical physics,

• connections to stochastic partial differential equations (SPDEs), Markov random fields (MRFs),

and conservative holographic analogies (such as the relationship between Liouville CFT and

AdS3/CFT2).

We emphasize a unified probabilistic viewpoint, following the foundational works of Kahane

[1], Robert–Vargas [2], Shamov [3], and the detailed survey of Rhodes–Vargas [4]. Our aim is to

provide a readable but technically informed introduction suitable for researchers with background

in probability or mathematical physics.

2 Gaussian log-correlated fields

2.1 General set-up

Let D ⊂ Rd be a bounded domain and let X be a centered Gaussian field indexed by D (more

precisely, a Gaussian random distribution on D). We say that X is log-correlated if its covariance

kernel has a logarithmic singularity along the diagonal. A canonical form is

E[X(x)X(y)] = log

1

|x − y|

+ g(x, y), (2.1)

for x, y in D, where g is a bounded, continuous function near the diagonal. This structure appears

in many models, including the two-dimensional Gaussian Free Field (GFF), one-dimensional 1/f

noises, and scaling limits of branching random walks and random matrix characteristic polynomials.

Since the covariance diverges when x → y, X is typically only a generalized function. In

particular, X(x) is not defined pointwise but only when tested against smooth functions. This

motivates the regularization approach.

2.2 Examples

Two-dimensional Gaussian Free Field. On a simply connected domain D ⊂ R2 with Dirichlet

boundary conditions, the Gaussian Free Field h is a centered Gaussian process indexed by test

functions f with covariance

E[h(f)h(g)] =

Z

D

Z

D

f(x)GD(x, y)g(y) dx dy,

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-3-2048.jpg)

![where GD is the Green’s function of the Laplacian on D. Near the diagonal, one has

GD(x, y) = −

1

2π

log |x − y| + H(x, y),

with H continuous. Thus, if one attempts to think of h(x) informally, its covariance behaves like a

logarithm at short distances, and h is a prototypical log-correlated field in dimension two.

Circle GFF and Fourier series. On the unit circle T, one can consider the random trigono-

metric series

X(θ) =

∞

X

n=1

1

√

n

(an cos(nθ) + bn sin(nθ)) ,

where (an, bn) are i.i.d. standard Gaussian pairs. This formal series defines a log-correlated Gaussian

distribution on T, with covariance behaving like − log |eiθ − eiθ′

| near the diagonal.

Random matrix characteristic polynomials. For a Haar-distributed unitary matrix U, one

can define

XN (θ) := log | det(1 − e−iθ

U)|,

with a suitable choice of branch. After centering and rescaling, these processes converge in distri-

bution as N → ∞ to a log-correlated Gaussian field on the circle. This is a remarkable connection

between random matrix theory and the GMC universality class, studied in [8, 9, 10].

3 Construction of Gaussian multiplicative chaos

3.1 Regularization and renormalization

Let X be a log-correlated Gaussian field on D with covariance of the form (2.1). In order to define

the exponential measure formally given by eγX(x) dx, we consider a family of smooth approximations

(Xε)ε0, for example

Xε(x) := (X ∗ ρε)(x),

where ρε is a mollifier at scale ε. For each ε 0, Xε is a smooth Gaussian field, and the object

exp γXε(x)

is well defined pointwise.

However, as ε → 0, the variance E[Xε(x)2] diverges like log(1/ε). The key renormalization is

to subtract the variance at the exponent level. For γ ∈ R, define the random measures

Mγ,ε(dx) := exp

γXε(x) −

γ2

2

E[Xε(x)2

]

dx. (3.1)

The subtraction of γ2

2 E[Xε(x)2] ensures that E[Mγ,ε(A)] remains of constant order as ε → 0 for

reasonable sets A ⊂ D.

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-4-2048.jpg)

![3.2 Kahane’s multiplicative chaos

Kahane introduced the notion of multiplicative chaos in a fairly general setting involving random

measures built from (possibly non-Gaussian) independently scattered noise [1]. In the Gaussian

case, his approach yields existence and non-triviality results for Mγ,ε in a range of parameters γ.

A fundamental result is that when |γ| is smaller than a critical parameter γc (depending on

the dimension and the covariance), the measures Mγ,ε converge (along suitable subsequences) to

a non-degenerate limit Mγ in the weak topology of measures. This limit is called the Gaussian

multiplicative chaos associated with the field X and parameter γ.

3.3 Shamov’s characterization and universality

Shamov [3] developed an intrinsic, approximation-free definition of subcritical Gaussian multiplica-

tive chaos. Let X be a centered Gaussian field on a measure space (T, µ) with covariance kernel

K. The law of X can be viewed as a Gaussian measure on a suitable Hilbert space. A random

measure M on T is called a (subcritical) Gaussian multiplicative chaos associated with X if:

(i) E[M(A)] = µ(A) for all measurable A ⊂ T,

(ii) for every deterministic ξ in the Cameron–Martin space of X, the shift property holds

M(X + ξ, dt) = eξ(t)

M(X, dt) a.s.

Under mild conditions, this characterizes the law of M uniquely in the subcritical regime. In

particular, any sequence of approximations (Xε) which converges to X in the Gaussian sense and

satisfies basic regularity conditions will generate the same limiting GMC measure (up to determin-

istic factors). This universality is a key reason why GMC appears in so many different models.

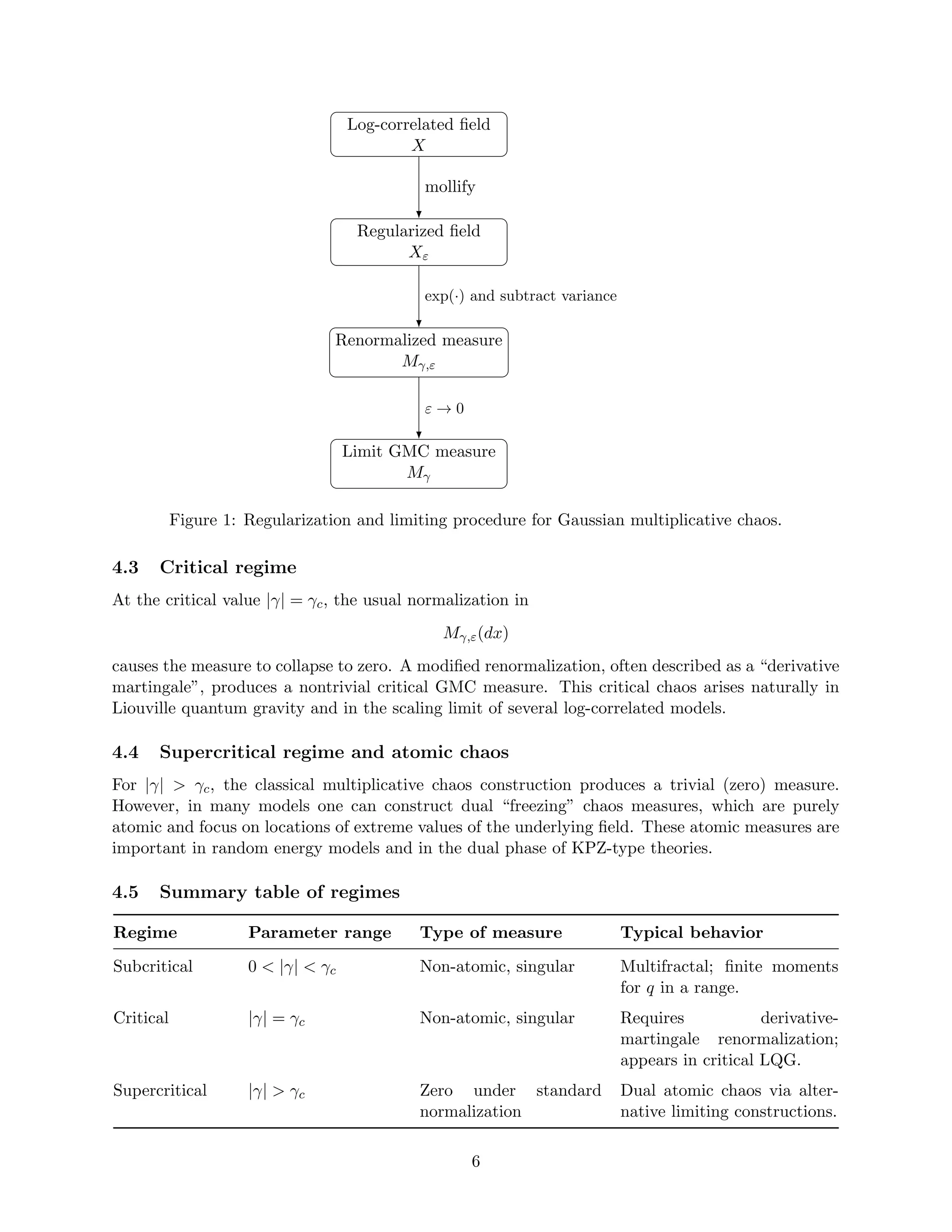

3.4 A schematic diagram of the construction

4 Phase diagram: subcritical, critical, and supercritical regimes

4.1 Critical value and normalization

For log-correlated fields in dimension d, the critical parameter is typically

γc =

√

2d

under a standard normalization of the covariance. For |γ| γc, the GMC is called subcritical and

yields a non-degenerate random measure. At γ = γc, a different renormalization scheme is needed

to obtain a non-trivial limit (critical GMC). For |γ| γc, the standard normalization leads to

trivial (zero) measures, although dual, purely atomic chaos measures can be constructed in various

ways.

4.2 Subcritical regime

In the subcritical phase 0 |γ| γc, the random measure Mγ is almost surely non-atomic and

singular with respect to the reference measure µ. It exhibits multifractal behavior: local masses

satisfy

Mγ(B(x, r)) ≈ rα(x)

,

with a random exponent α(x) having a nontrivial distribution related to thick points of the Gaussian

field.

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-5-2048.jpg)

![5.3 Star-scale invariance

GMC measures are examples of ∗-scale invariant random measures. Informally, this means that if

one zooms in by a factor r, the measure decomposes into a random multiplicative factor determined

by the increment of the field, times an independent copy of the original measure. This property

is shared with multiplicative cascades and plays a key role in the connection between discrete and

continuous models.

More precisely, in many settings one has a relation of the form

Mγ(dx)

d

=

Z

exp

γYr(x) − γ2

2 E[Yr(x)2

]

M(r)

γ (dx),

where Yr is an appropriate Gaussian increment at scale r, and M

(r)

γ is a rescaled version of Mγ,

independent of Yr. Such relations link GMC to canonical models of multiplicative cascades and to

the theory of log-infinitely divisible random measures.

5.4 A schematic star-scale invariance diagram

Mγ

global measure

M

(r)

γ

rescaled copy

eγYr−γ2

2

EY 2

r

multiplicative factor

zoom in field increment

))

Mγ

d

= (multiplicative factor) × M

(r)

γ

Figure 2: Informal star-scale invariance structure of GMC measures.

5.5 Universality and stability

Shamov’s characterization ensures that subcritical GMC measures are stable under changes of ap-

proximation. For example, mollification by different kernels, spectral truncation, or circle-averaging

procedures all yield the same limiting measure, provided the approximations converge to the same

Gaussian field. This universality is a key reason why GMC appears in so many different models: as

long as the underlying field is log-correlated and the covariance structure is compatible, the limiting

measure is essentially unique.

Moreover, many quantitative properties of GMC (such as moment bounds, tail behavior, and

thick point geometry) depend only on a small number of parameters (e.g. the variance normalization

of X and the dimension d), reinforcing the idea that GMC defines a robust universality class for

multifractal random measures.

6 GMC in probability and analysis

6.1 Extremes of log-correlated fields

The maximum of a log-correlated Gaussian field on a bounded domain exhibits non-trivial fluctu-

ations. A recurring theme is that the extreme values of X are closely related to the peaks of the

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-8-2048.jpg)

![GMC measure Mγ. In many models, the asymptotic distribution of the centered maximum can be

expressed in terms of the limit of certain functionals of Mγ, and the tail behavior is influenced by

the multifractal structure.

For instance, consider a log-correlated field X on a domain D and define

MN := max

x∈DN

X(x),

where DN is a discrete mesh approximating D at scale N−1. Under appropriate normalization,

MN converges in law to a randomly shifted Gumbel distribution. The shift is often expressed in

terms of a derivative-type chaos or related limit of GMC functionals. This picture is well developed

for branching Brownian motion and branching random walks, and analogous results exist for the

2D GFF and for characteristic polynomials of random matrices.

The link between extremes and GMC is conceptually natural: the most singular points of Mγ

correspond to locations where X takes unusually large values. Thus, understanding the geometry

of thick points and the multifractal spectrum of Mγ informs the asymptotic behavior of extremes.

6.2 Liouville Brownian motion

Given a GMC measure Mγ on a domain D, one can define a time-change of standard Brownian

motion using Mγ as a speed measure. Let (Bt)t≥0 be a Brownian motion on D (with reflection or

absorption at the boundary). Define the additive functional

At =

Z t

0

exp

γX(Bs) − γ2

2 E[X(Bs)2

]

ds

in a suitable regularized sense, or more abstractly,

At =

Z t

0

f(Bs) ds with f dx = Mγ(dx).

The inverse time-change

τu = inf{t ≥ 0 : At u}

defines a new process

Zu = Bτu ,

known as Liouville Brownian motion. Intuitively, Z is Brownian motion in the random geometry

encoded by the Liouville measure Mγ. This construction provides a probabilistic model for diffusion

on Liouville quantum gravity surfaces and is closely related to Dirichlet form techniques and time-

change theory.

6.3 Fractal geometry and Hausdorff measures

GMC is closely connected with the theory of random fractals and Hausdorff measures. In many

cases, one can regard Mγ as a random density that, when combined with deterministic or random

metrics, gives rise to natural random Hausdorff measures on fractal sets. For example, if d(x, y) is

a metric on D (possibly random), one can define a Hausdorff measure with gauge function modified

by the local density of Mγ. The multifractal formalism for Mγ then provides detailed information

about the local dimensions and scaling properties of such measures.

From a technical standpoint, tools from potential theory, capacity, and Frostman-type lemmas

are often used together with GMC to obtain lower and upper bounds on Hausdorff dimensions of

random sets. This interplay has been particularly fruitful in the study of level sets and thick points

of GFF-type fields.

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-9-2048.jpg)

![7 GMC in mathematical physics

7.1 Liouville quantum gravity

Liouville quantum gravity (LQG) is a probabilistic model of random two-dimensional geometry. In

the original physics literature, it arises from the Liouville action for a scalar field ϕ coupled to the

metric on a 2D surface. Formally, the volume form of the random metric can be written as

eγϕ(z)

dz,

where ϕ is essentially a Gaussian Free Field. The measure theory of LQG thus rests on giving a

meaning to these exponentials, which is precisely what GMC provides.

Duplantier and Sheffield [5] formulated LQG in probabilistic terms and established the KPZ

relation connecting Euclidean and quantum fractal dimensions. The Liouville measure on a planar

domain is, by definition, the GMC measure associated with a 2D GFF and a coupling constant γ

in a certain range. This random measure describes the area element of the random surface.

LQG also arises as the scaling limit of random planar maps. Various ensembles of random

triangulations and quadrangulations, when rescaled appropriately, converge to continuum random

surfaces whose area measure is described by Liouville GMC. This link between discrete combina-

torial models and continuum random geometry is a major success of the GMC framework.

7.2 KPZ relation

The KPZ relation is a quadratic transformation linking the Euclidean dimension of a fractal set

and its dimension with respect to the LQG measure. If a set K has Euclidean Hausdorff dimension

dE, then its Liouville (or “quantum”) dimension dQ is given by an explicit function

dE =

γ2

4

d2

Q +

1 −

γ2

4

dQ.

This relation was conjectured in the physics literature and proved rigorously in [5, 6]. GMC plays

a central role in the proof, as the Liouville measure determines the quantum geometry in which the

fractal dimension is measured.

Practically, the KPZ relation allows one to transfer dimension estimates between the Euclidean

geometry of subsets of the plane and their geometry in the random metric induced by LQG. This

has been used to analyze the fractal structure of interfaces, geodesics, and other geometric objects

in random planar maps and in continuum LQG.

7.3 Liouville conformal field theory

Liouville conformal field theory (LCFT) is a non-rational conformal field theory whose correlation

functions can be expressed in terms of GMC measures. Expectation values of vertex operators

eαϕ(z) can be written as integrals involving powers of GMC measures.

Remy [7] used this connection to prove the Fyodorov–Bouchaud formula, which gives the exact

distribution of the total mass of a subcritical GMC measure on the unit circle. The argument

proceeds by relating negative moments of the total mass to Liouville CFT correlation functions

and using BPZ-type differential equations to identify the law. This provides a striking example in

which ideas from conformal field theory and GMC combine to yield an exact probabilistic result.

More generally, the probabilistic construction of LCFT via GMC offers a rigorous interpretation

of Liouville correlation functions, including the DOZZ structure constants. While many technical

details remain quite intricate, the GMC viewpoint has become standard in mathematical treatments

of LCFT.

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-10-2048.jpg)

![8 GMC, stochastic PDEs, and KPZ-type structures

8.1 Stochastic heat equation and KPZ

The Kardar–Parisi–Zhang (KPZ) equation in one spatial dimension,

∂th =

1

2

(∂xh)2

+

1

2

∂xxh + ξ,

where ξ is space-time white noise, is formally connected to the stochastic heat equation with

multiplicative noise via the Cole–Hopf transform

Z = eh

.

Formally, Z solves

∂tZ =

1

2

∂xxZ + ξZ.

Solutions to the stochastic heat equation with multiplicative noise exhibit intermittency and multi-

scale fluctuations reminiscent of multiplicative chaos. In particular, the random field Z(t, x) can

have moments that grow super-exponentially in time, and the logarithm of Z can display rough

spatial behavior.

Although the KPZ equation and its universality class differ in structure from the static log-

correlated fields used in GMC, there are conceptual parallels: both involve exponential transforms

of Gaussian-type objects and produce random measures with intermittent peaks. In certain scaling

regimes, asymptotic fields derived from stochastic heat equations and related models have log-

correlated limits, and their exponential transforms can give rise to GMC-type measures.

8.2 SPDE-based approximations to GMC

In some constructions, log-correlated fields can be represented as time-integrals of solutions to

linear SPDEs. For example, one may represent a GFF as an integral over the heat kernel or as the

stationary solution of a suitable stochastic PDE. When such representations are available, they can

be used to construct GMC via SPDE approximations rather than direct spectral or convolutional

regularization.

The general idea is to consider a family of Gaussian fields

XT (x) =

Z T

0

Φt(x) dWt,

where (Φt) is a deterministic family of operators (often involving the heat semigroup) and Wt is a

cylindrical Brownian motion. As T → ∞, XT converges in distribution to a log-correlated field X.

One can then consider the measures

Mγ,T (dx) = exp

γXT (x) − γ2

2 E[XT (x)2

]

dx

and study their convergence to a GMC measure Mγ. This viewpoint connects the GMC construction

to techniques from SPDEs and stochastic quantization.

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-11-2048.jpg)

![8.3 Renormalization and regularity structures

In the theory of singular stochastic PDEs, renormalization is used to make sense of equations whose

nonlinearities are ill-defined when driven by distributions (rather than functions). A well-known

example is Hairer’s theory of regularity structures. The renormalization procedures in SPDEs often

involve subtracting divergent constants in a way that is reminiscent of the variance subtraction in

GMC. This parallel is conceptual: both theories use renormalization to define nonlinear functionals

of distributions, although the technical frameworks are different.

8.4 A schematic SPDE–GMC diagram

Linear SPDE

(e.g. stochastic heat equation)

Gaussian field XT

(approximate GFF)

GMC measure Mγ,T

time-integral, T → ∞ exp(·), renorm.

Figure 3: Conceptual link between SPDE-based Gaussian fields and GMC measures.

9 GMC, Markov random fields, and exponential tilts

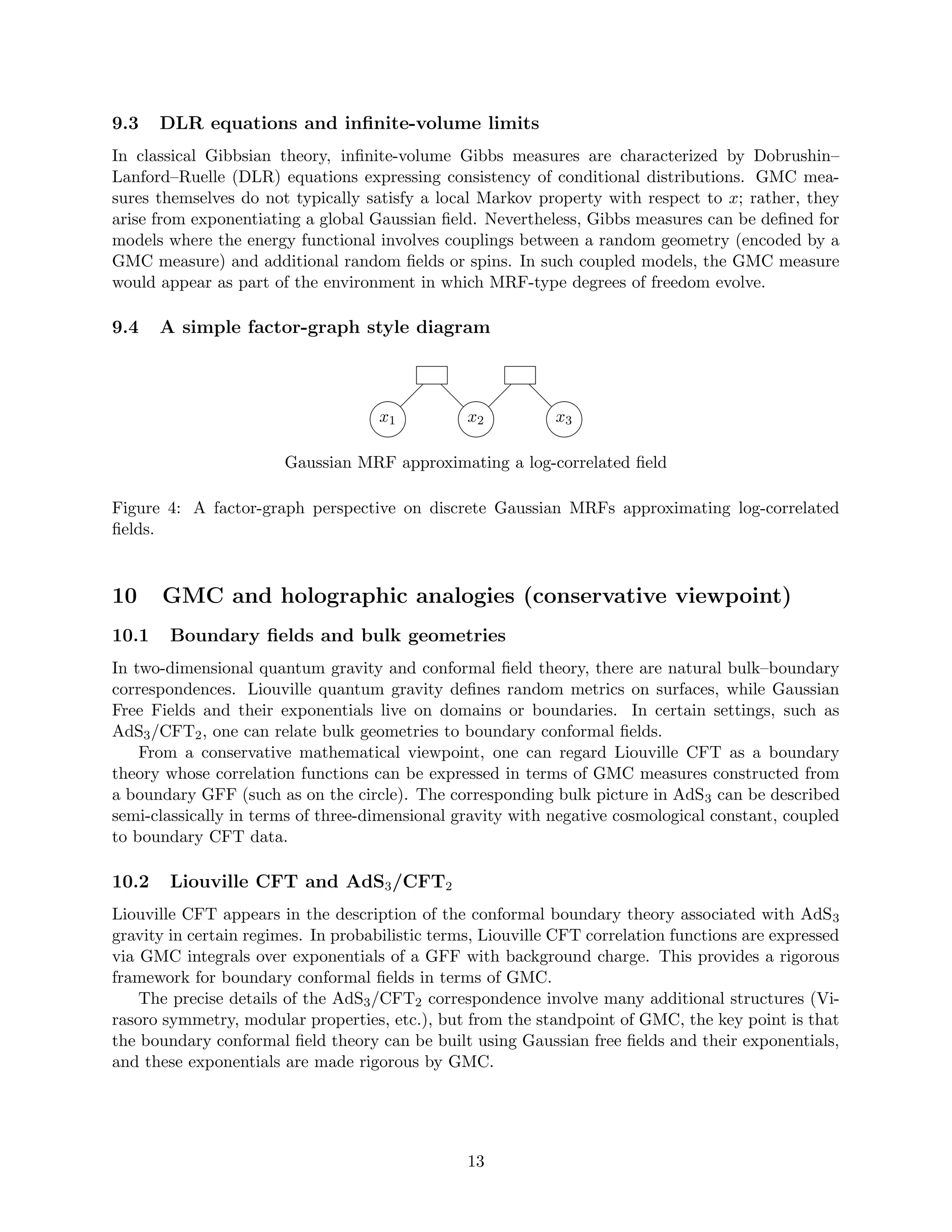

9.1 Gaussian Markov random fields and log-correlated limits

Markov random fields (MRFs) are random fields whose finite-dimensional distributions satisfy con-

ditional independence properties encoded by a graph or a geometry. Gaussian MRFs are Gaussian

fields whose covariance structure and conditional independence properties are determined by a

precision matrix or an elliptic operator.

Discrete approximations of log-correlated fields, such as the discrete Gaussian free field on a

lattice, are Gaussian MRFs. The continuum GFF can be regarded as a scaling limit of these

discrete MRFs. In this sense, GMC measures constructed from log-correlated fields can be viewed

as exponential tilts of measures associated with continuum limits of Gaussian MRFs.

9.2 Exponential tilts and Gibbs measures

In finite dimensions, if X is a Gaussian vector and V (x) is a potential, one can define a Gibbs

measure

µV (dx) ∝ e−V (x)

µ0(dx),

where µ0 is the Gaussian measure. In the context of GMC, one considers exponentials of linear

functionals of X:

exp

γX(x) − γ2

2 E[X(x)2

]

.

Integrating these exponentials with respect to a base measure µ yields the GMC measure. At a

formal level, one can think of GMC as the exponential tilt

dMγ

dµ

(x) = exp

γX(x) − γ2

2 E[X(x)2

]

.

For each realization of X, this defines a density with respect to µ.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-12-2048.jpg)

![10.3 Boundary random measures and bulk observables

One can think of GMC measures on the boundary as encoding random weights that influence bulk

observables. For example, certain gravitational observables in the bulk can be related to insertions

of vertex operators in the boundary theory, whose correlation functions involve GMC. From this

perspective, GMC provides a probabilistic language for the boundary side of a holographic relation,

while the bulk side is described by geometric or gravitational models.

10.4 A schematic holographic diagram

Boundary CFT with GMC

Bulk geometry (e.g. AdS3)

holographic map

Figure 5: Conservative schematic of a bulk–boundary relation: GMC measures on the boundary

enter Liouville CFT, which is related to a bulk gravitational model.

11 Random matrices and analytic number theory

11.1 Characteristic polynomials of random unitary matrices

For the Circular Unitary Ensemble (CUE), the characteristic polynomial

PN (θ) = det(1 − e−iθ

U)

has logarithm XN (θ) = log |PN (θ)| that converges in distribution to a log-correlated Gaussian field

on the circle after suitable centering and normalization. Webb [8] showed that in the L2 regime,

exponentials of XN converge to a GMC measure on the circle, and Nikula–Saksman–Webb [9]

extended this to the L1 phase, establishing convergence for the full subcritical range of γ.

These results link the multifractal structure of characteristic polynomials to GMC and provide

a detailed description of their thick points and extreme values.

11.2 Random Hermitian matrices

Berestycki [10] proved analogous results for a broad class of random Hermitian matrices, showing

that the logarithms of characteristic polynomials converge to log-correlated fields and that their

exponentials converge to GMC measures. This demonstrates the robustness of the GMC description

across random matrix ensembles and supports the universality of log-correlated Gaussian fields in

spectral statistics.

11.3 Riemann zeta function

Fyodorov, Hiary, and Keating conjectured that the maxima of |ζ(1/2 + it)| over intervals behave

like the maxima of log-correlated Gaussian fields. Saksman and Webb [11] proved that, in an

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-14-2048.jpg)

![appropriate mesoscopic scaling regime, the Riemann zeta function on the critical line can be de-

composed into a product of a smooth factor, a diverging scalar factor, and a complex Gaussian

multiplicative chaos. This identifies the “rough” part of zeta fluctuations with GMC and reinforces

the universality of the log-correlated / GMC picture.

These connections between GMC, random matrices, and the zeta function provide a rich inter-

play between probability, spectral theory, and analytic number theory, and continue to be a very

active area of research.

12 GMC in turbulence and finance

12.1 Kolmogorov–Obukhov model and intermittency

Kahane was partly motivated by turbulence when developing multiplicative chaos. The Kolmogorov–

Obukhov model of turbulence assumes a log-normal cascade for energy dissipation across scales.

Robert and Vargas [2] constructed a rigorous version of this model using GMC, providing a mathe-

matically precise turbulence dissipation measure with log-normal statistics. The resulting measures

exhibit intermittency properties similar to those observed experimentally.

In these models, the energy dissipation at scale r is modeled by a multiplicative cascade, which

in the continuum limit becomes a GMC measure over scales or spatial locations. The multifractal

properties of GMC then capture the observed multi-scale variability of turbulence, such as bursts

of high dissipation interspersed with calmer regions.

12.2 Financial time series and volatility

In quantitative finance, log-normal multiplicative cascades have been used to model volatility at

multiple time scales. Bacry and Muzy proposed continuous-time cascade models in which volatility

is driven by a multiplicative cascade across scales. In the continuum limit, these models can be

formulated in terms of Gaussian multiplicative chaos, with the volatility measure at a given time

represented by a GMC measure over scales.

This provides a flexible framework for modeling heavy tails and intermittency in return dis-

tributions. The GMC viewpoint clarifies the role of multi-scale randomness and suggests ways to

connect empirical scaling laws (such as multiscaling of moments) with the underlying probabilistic

structure of volatility.

13 Open problems and further directions

Gaussian multiplicative chaos is a mature topic, but many important questions remain. Among

them:

• Precise understanding of the supercritical phase and the structure of dual atomic chaos measures

in general settings. While specific constructions exist in branching random walk and certain log-

REM models, a unified theory for broad classes of log-correlated fields is still under development.

• Extensions of GMC to non-Gaussian log-correlated fields and to fields with more complex cor-

relation structures, including anisotropic or non-stationary models. Some progress exists in the

direction of non-Gaussian multiplicative chaos, but many questions remain open.

• Deeper connections between GMC and singular SPDEs, particularly in situations where both

theories require renormalization of nonlinear functionals of distributions. A more systematic

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-15-2048.jpg)

![dictionary between renormalization in GMC and renormalization in regularity structures or

paracontrolled calculus would be of great conceptual interest.

• Further clarification of the role of GMC in random matrix theory and analytic number the-

ory, including finer asymptotics for maxima, high-moment behavior, and extreme statistics for

characteristic polynomials and zeta values.

• Rigorous holographic interpretations in which boundary GMC measures are directly related

to bulk geometric or gravitational observables in higher dimensions. While Liouville CFT and

AdS3/CFT2 provide important motivating examples, a fully developed probabilistic holographic

framework remains an open direction.

These questions sit at the intersection of probability, analysis, geometry, and mathematical

physics and illustrate the continuing importance of GMC as a unifying concept.

Acknowledgements

This survey-style document synthesizes results from a large body of work by many authors. The

reader is encouraged to consult the original papers for precise statements and proofs.

References

[1] J.-P. Kahane, Sur le chaos multiplicatif, Ann. Sci. Math. Québec 9(2), 105–150 (1985).

[2] R. Robert and V. Vargas, Gaussian multiplicative chaos revisited, Ann. Probab. 38(2), 605–631

(2010).

[3] A. Shamov, On Gaussian multiplicative chaos, J. Funct. Anal. 270(9), 3224–3261 (2016).

[4] R. Rhodes and V. Vargas, Gaussian multiplicative chaos and applications: a review, Probab.

Surv. 11, 315–392 (2014).

[5] B. Duplantier and S. Sheffield, Liouville quantum gravity and KPZ, Invent. Math. 185(2),

333–393 (2011).

[6] B. Duplantier, R. Rhodes, S. Sheffield, and V. Vargas, Renormalization of critical Gaussian

multiplicative chaos and KPZ, Commun. Math. Phys. 330, 283–330 (2014).

[7] G. Remy, The Fyodorov–Bouchaud formula and Liouville conformal field theory, Probab. The-

ory Relat. Fields 176, 345–378 (2020).

[8] C. Webb, The characteristic polynomial of a random unitary matrix and Gaussian multiplica-

tive chaos: the L2-phase, Electron. J. Probab. 20, 1–21 (2015).

[9] M. Nikula, E. Saksman, and C. Webb, Multiplicative chaos and the characteristic polynomial

of the CUE: the L1-phase, Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 373(6), 3905–3965 (2020).

[10] N. Berestycki, Random Hermitian matrices and Gaussian multiplicative chaos, Probab. Theory

Relat. Fields 172, 103–189 (2018).

[11] E. Saksman and C. Webb, The Riemann zeta function and Gaussian multiplicative chaos:

statistics on the critical line, Adv. Math. 305, 109–163 (2017).

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-16-2048.jpg)

![[12] Y. V. Fyodorov and J.-P. Bouchaud, Freezing and extreme-value statistics in a random energy

model with logarithmically correlated potential, J. Phys. A 41, 372001 (2008).

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/gaussianmultiplicativechaos-251211185015-d3ba8978/75/Gaussian-Multiplicative-Chaos-Theory-Structure-and-Applications-17-2048.jpg)