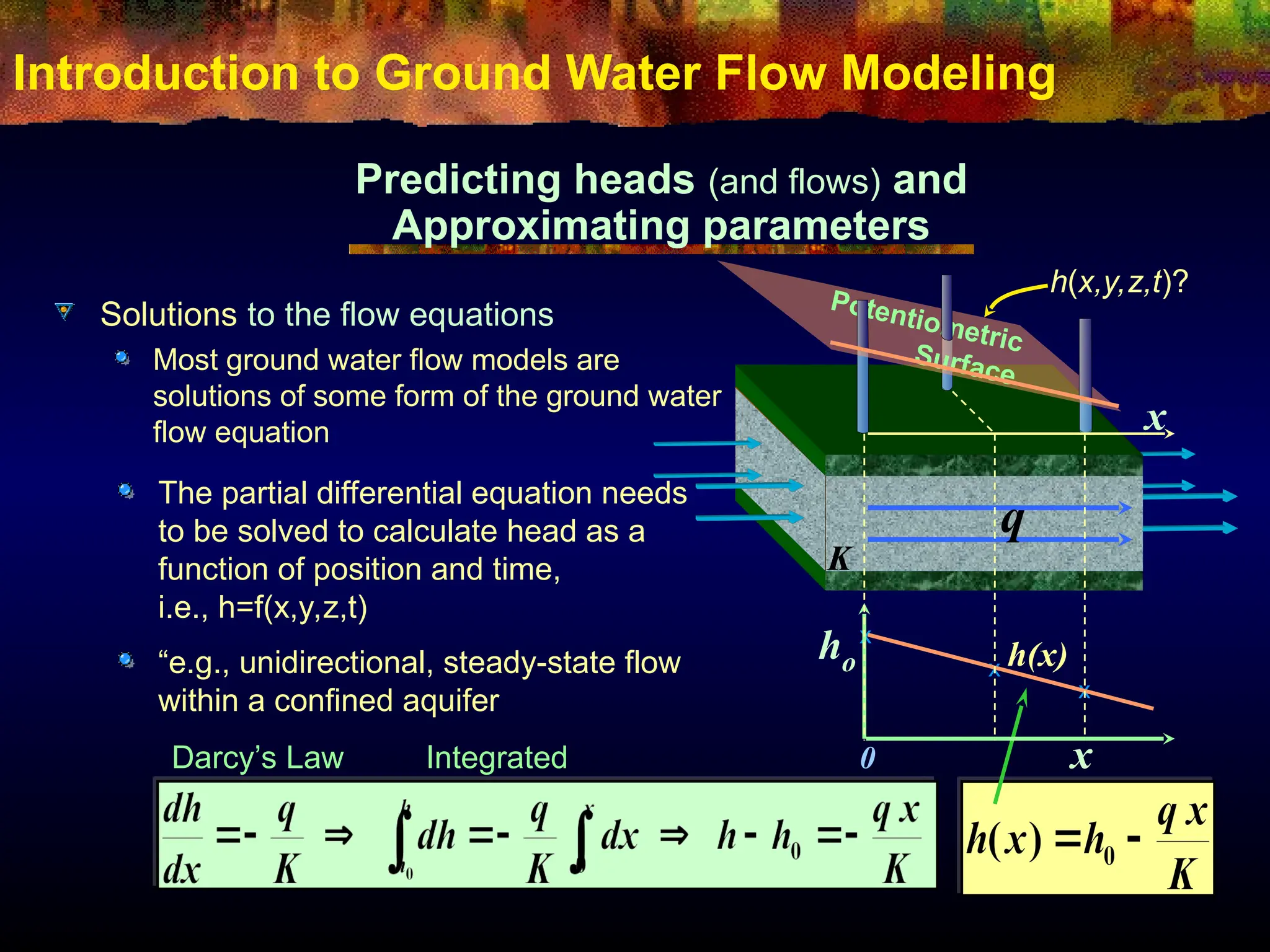

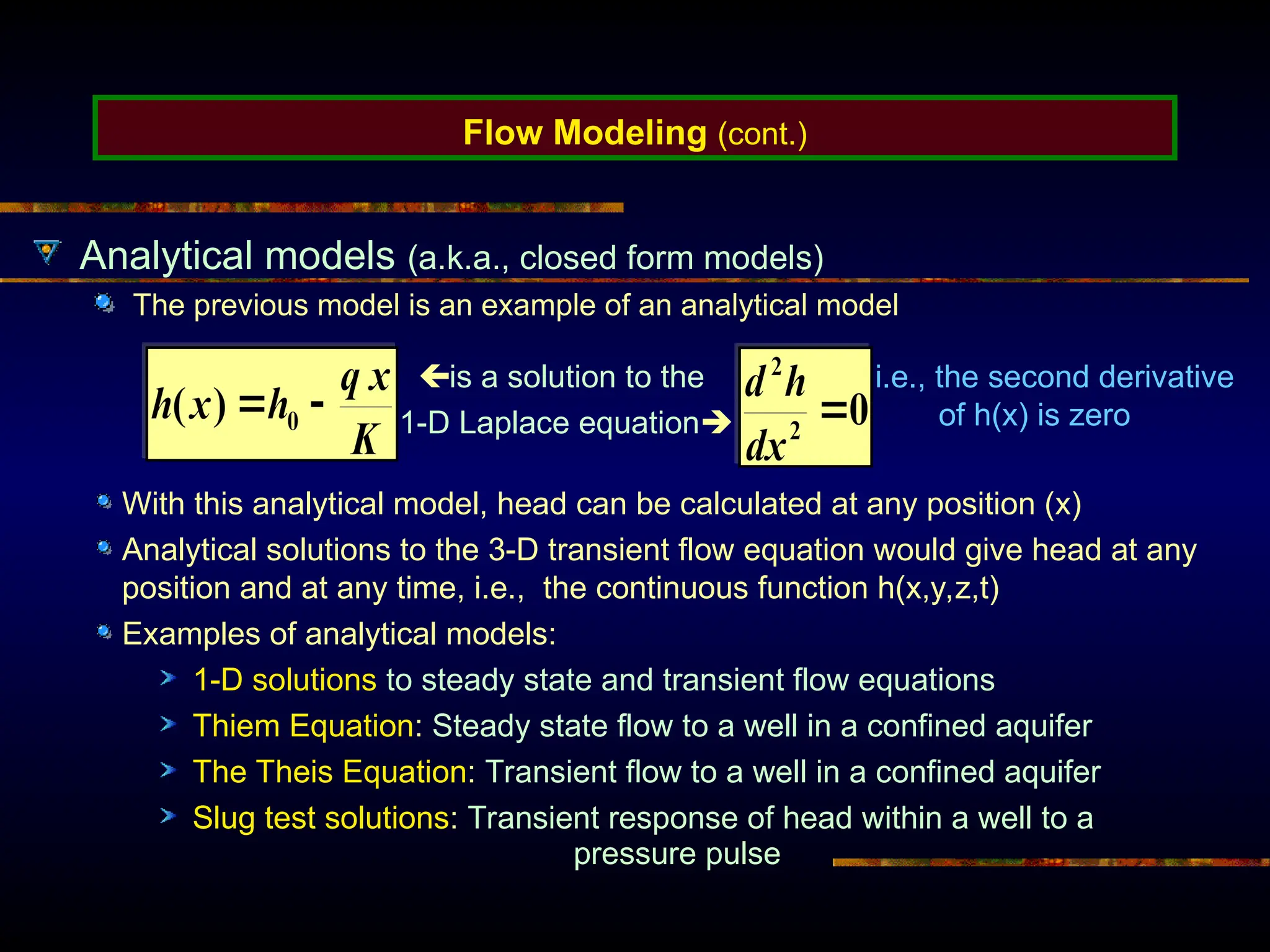

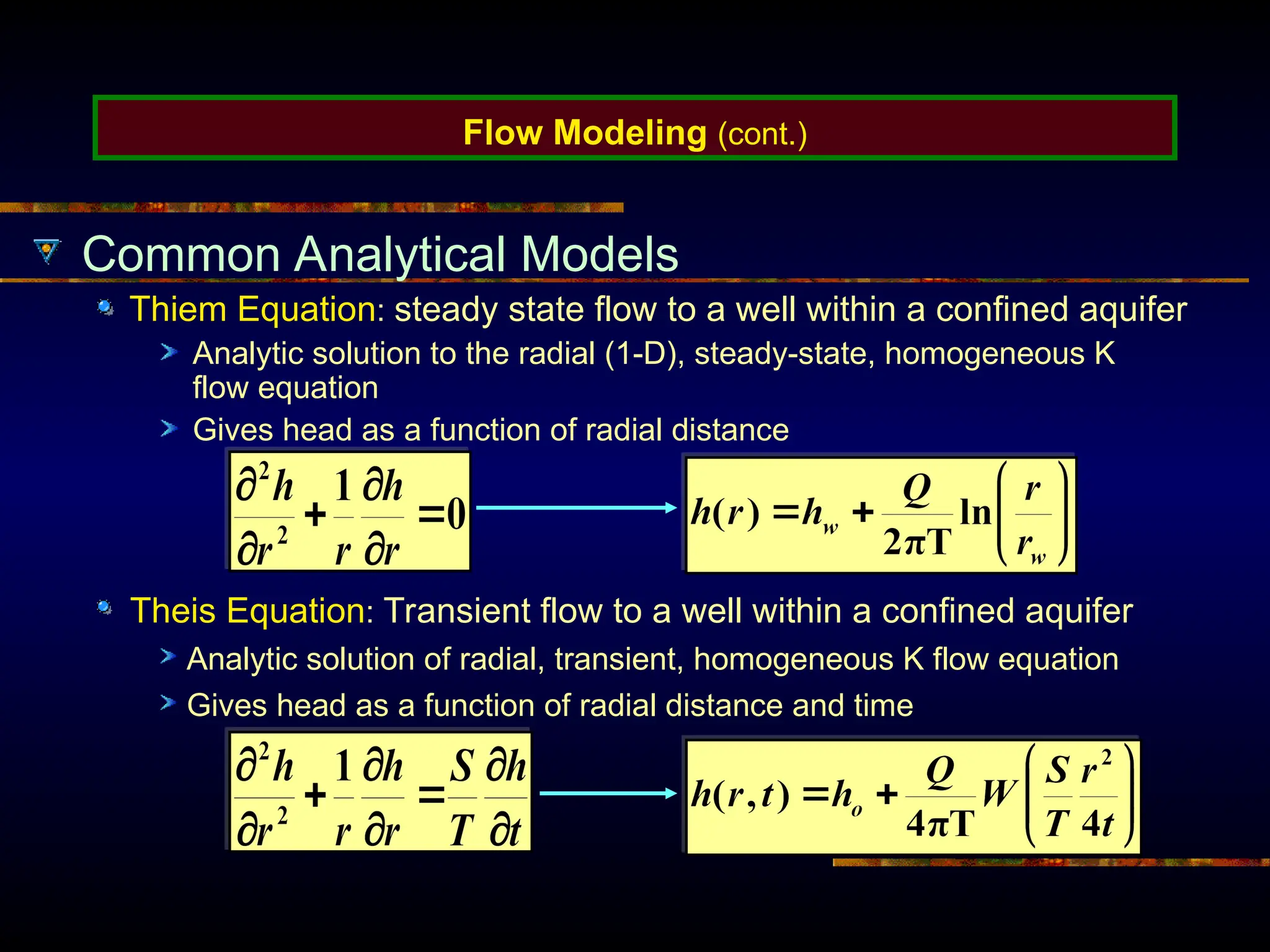

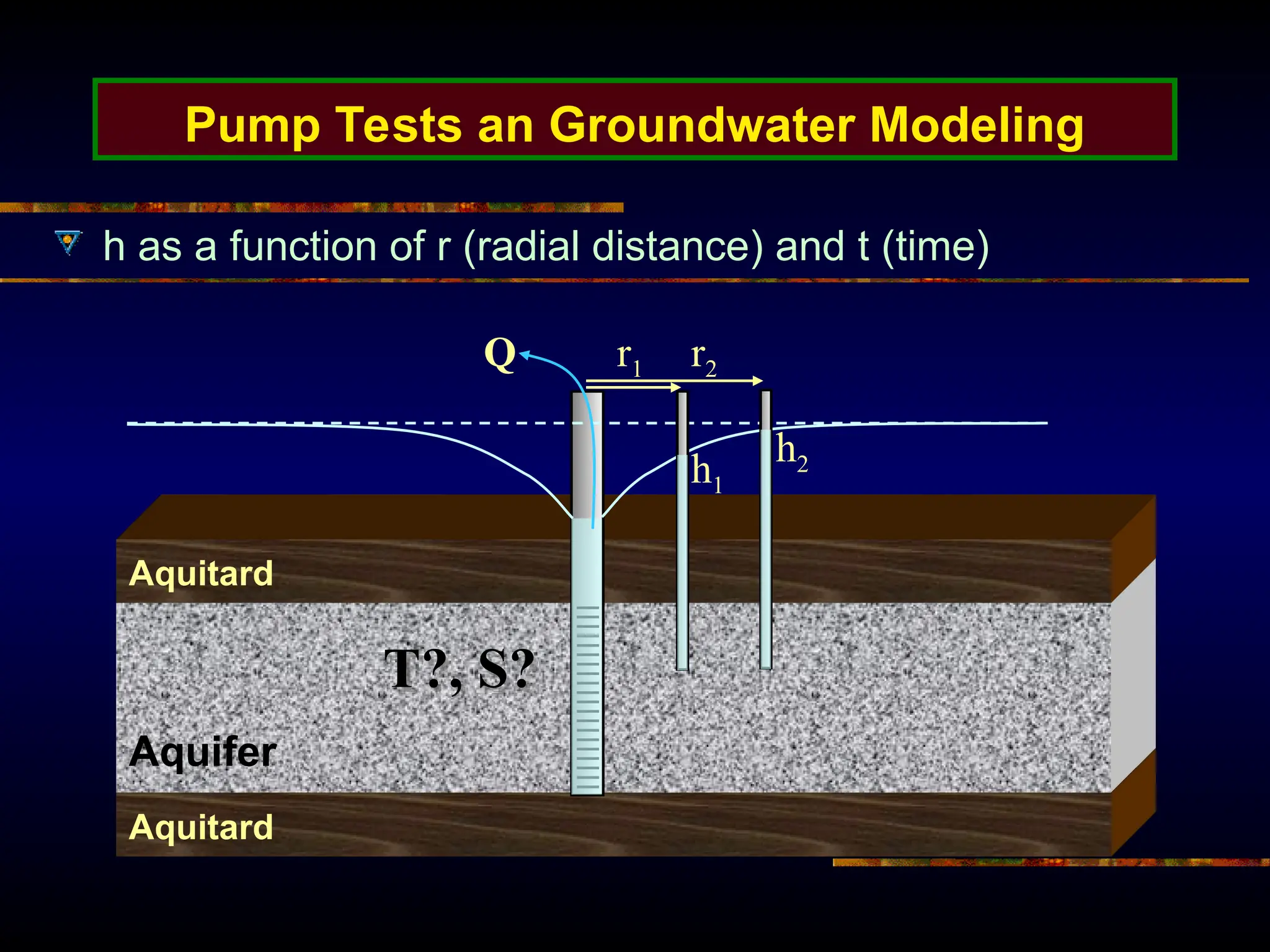

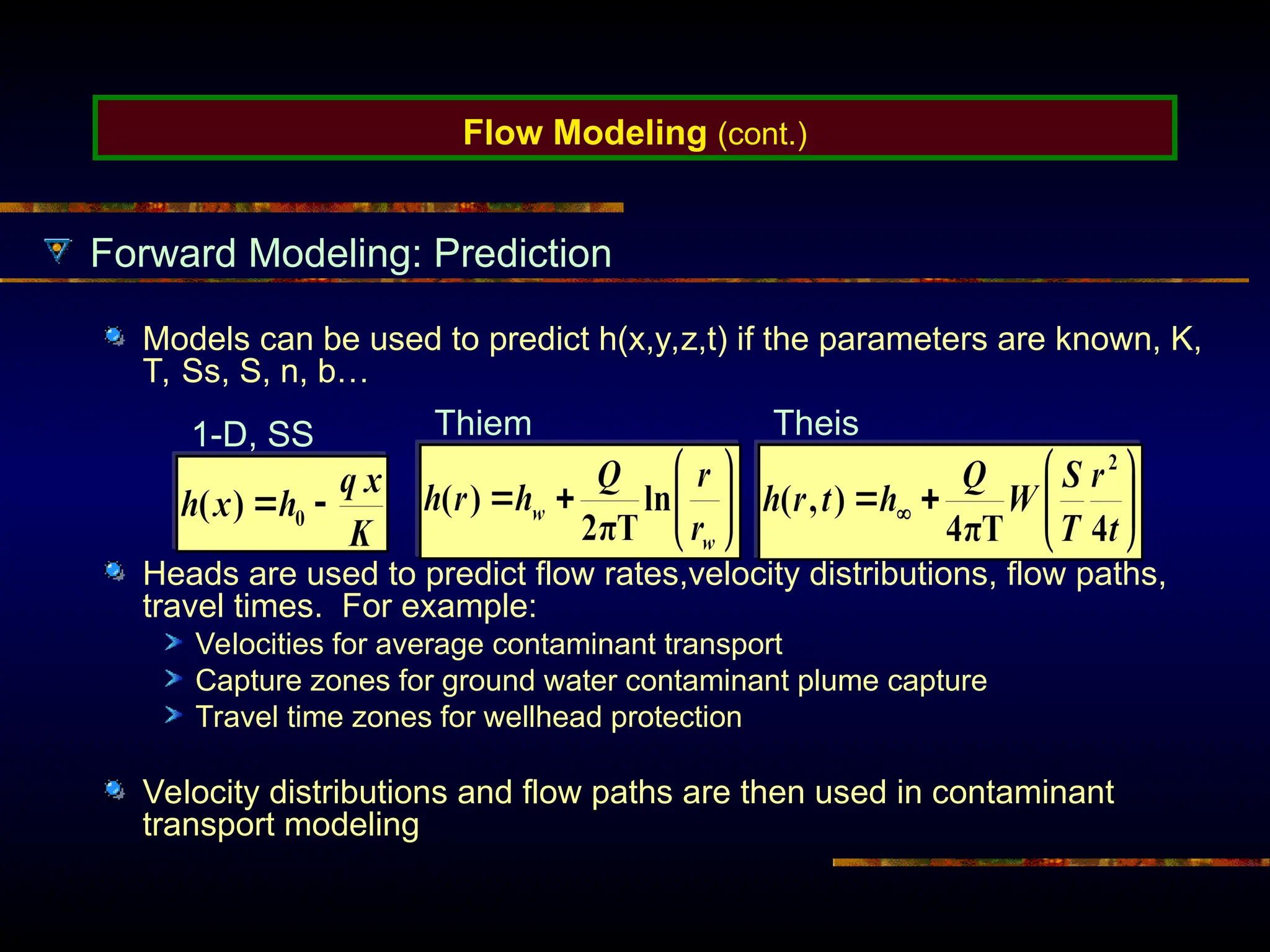

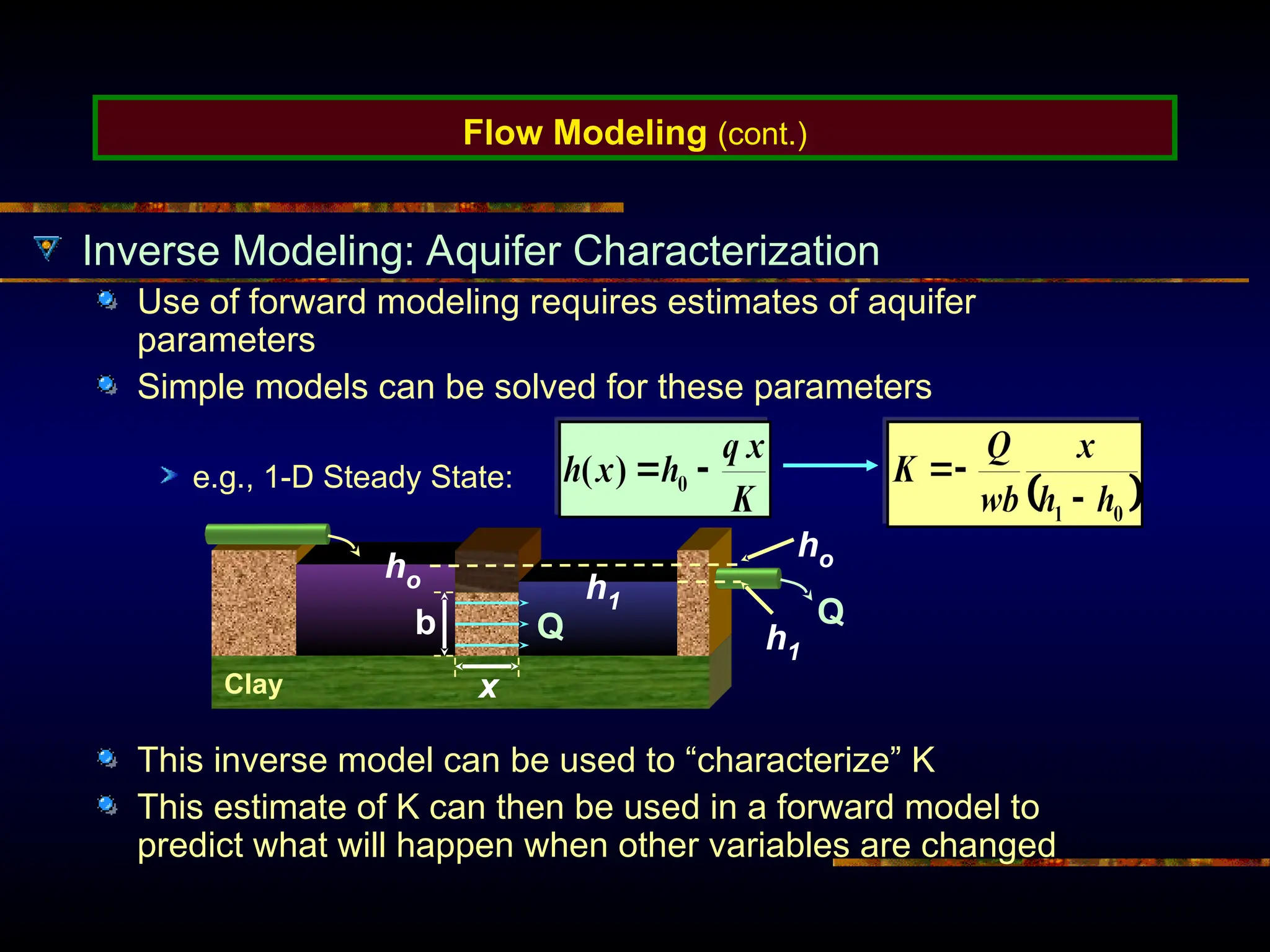

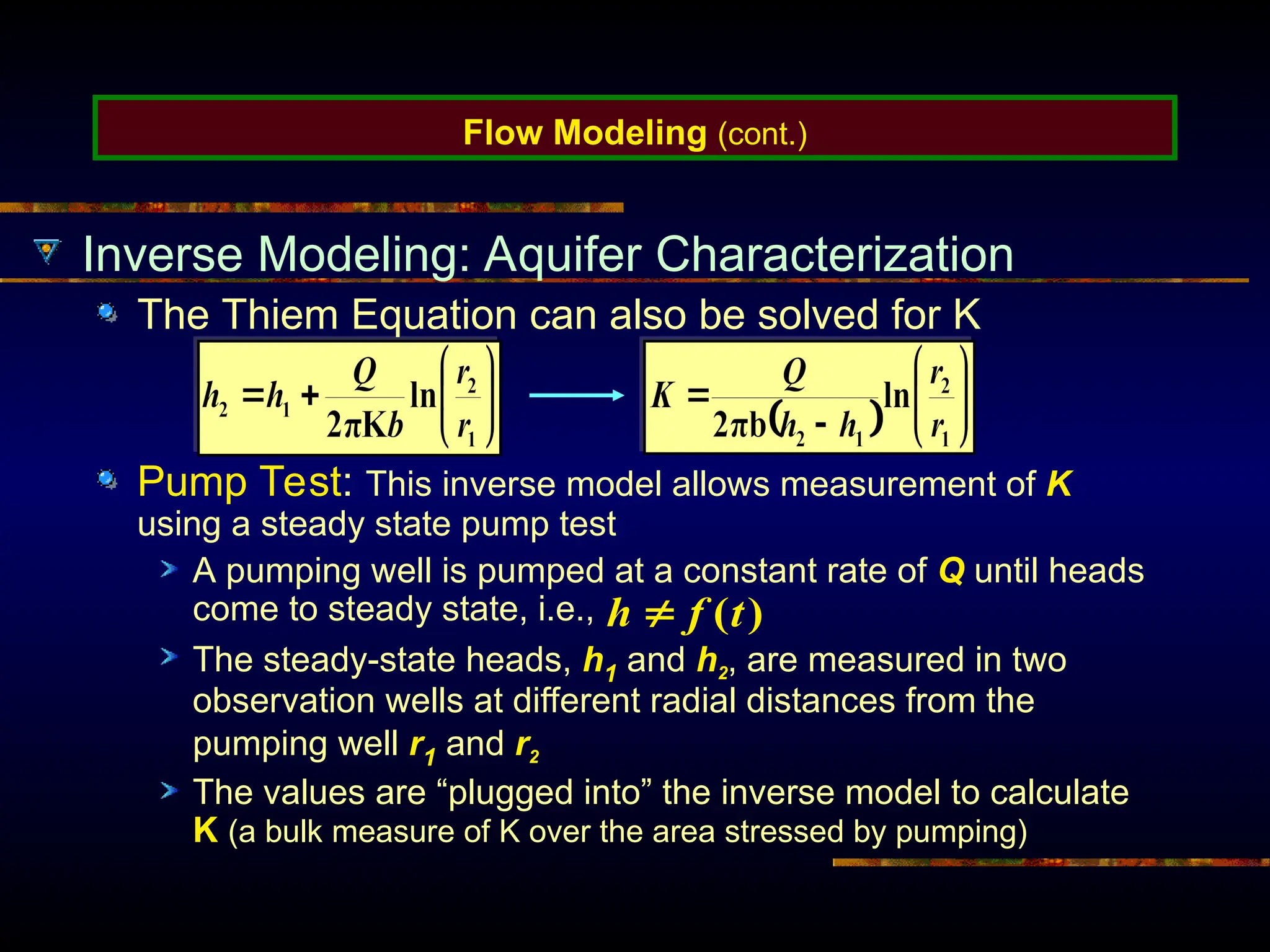

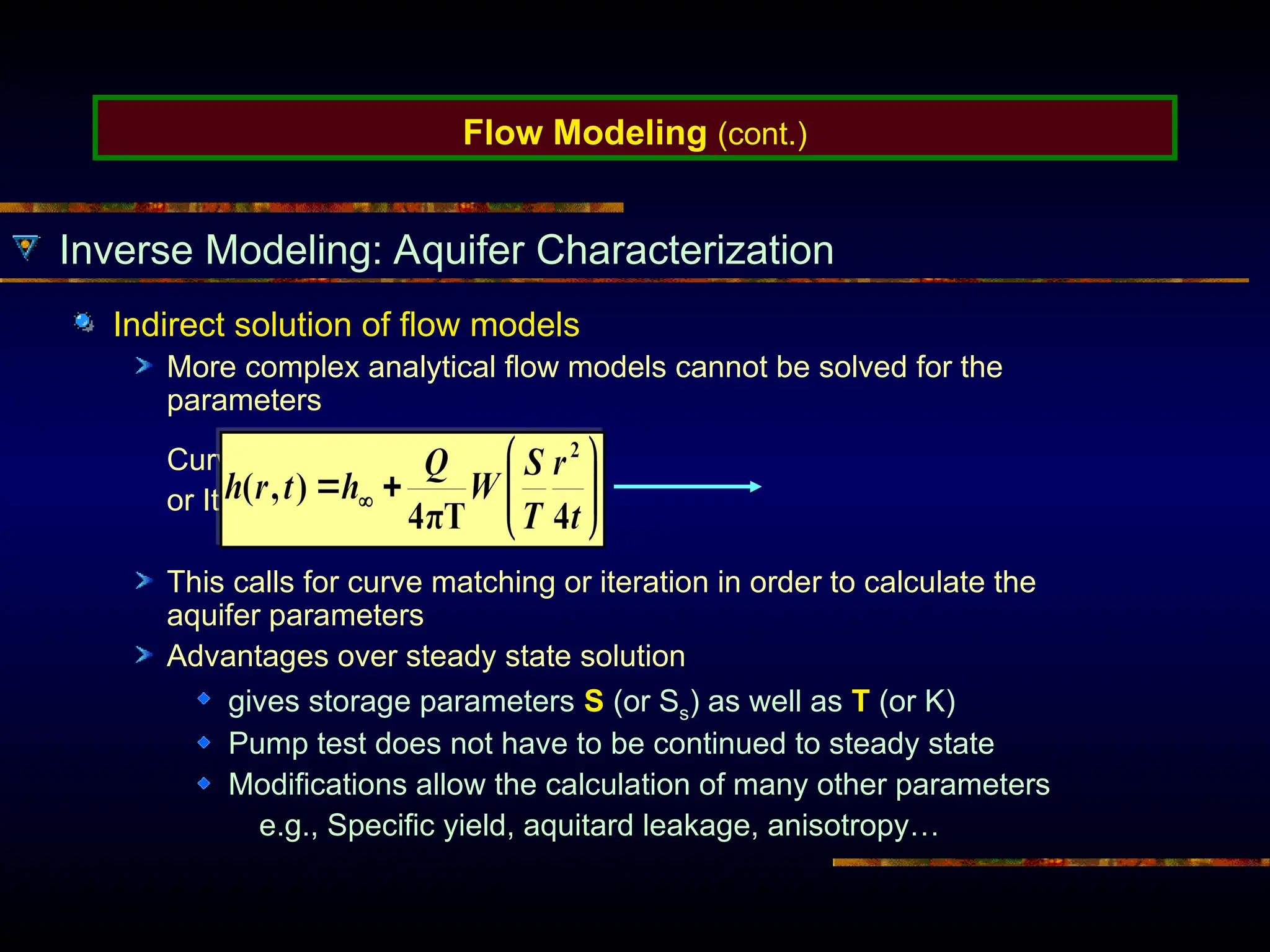

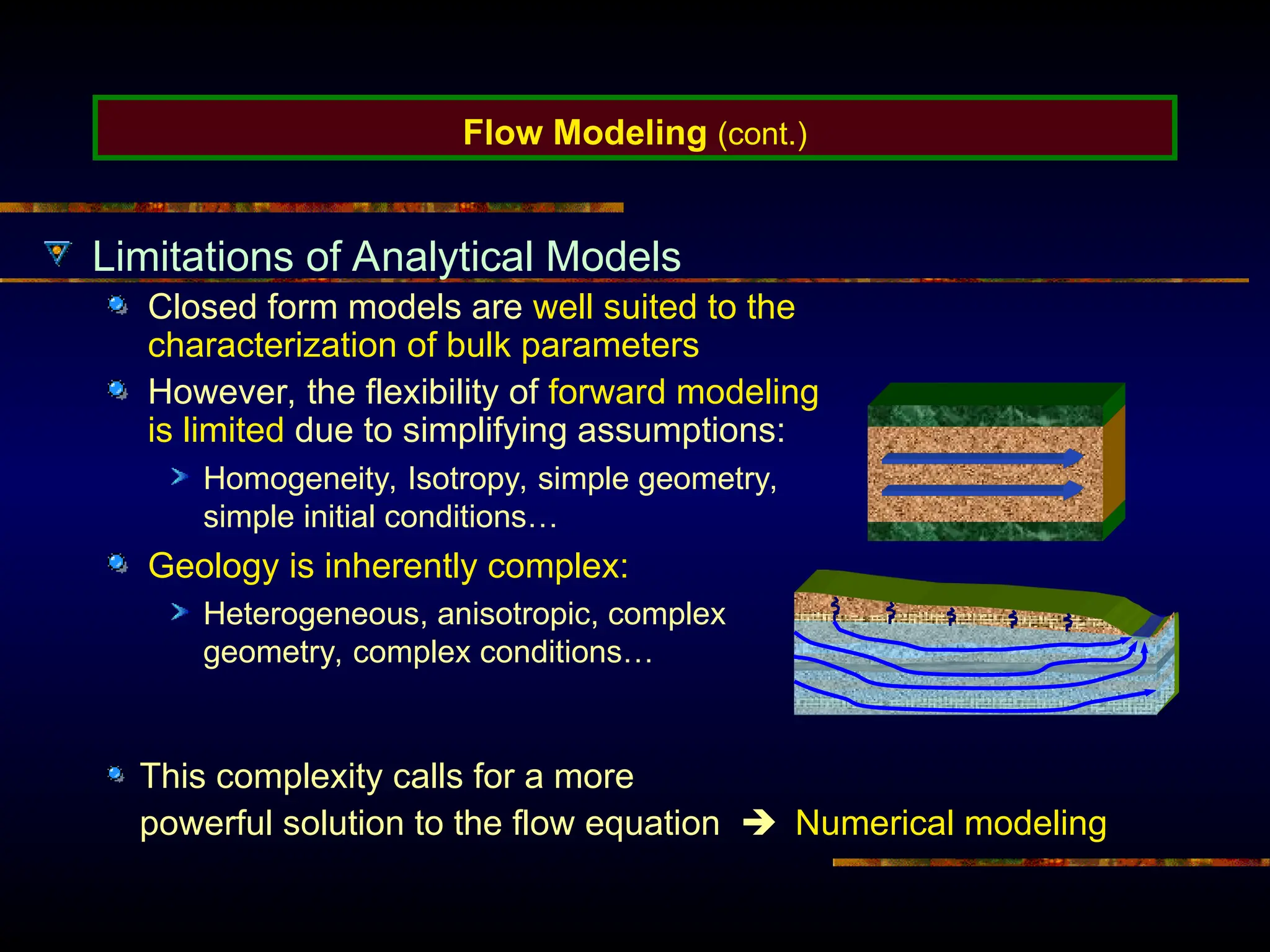

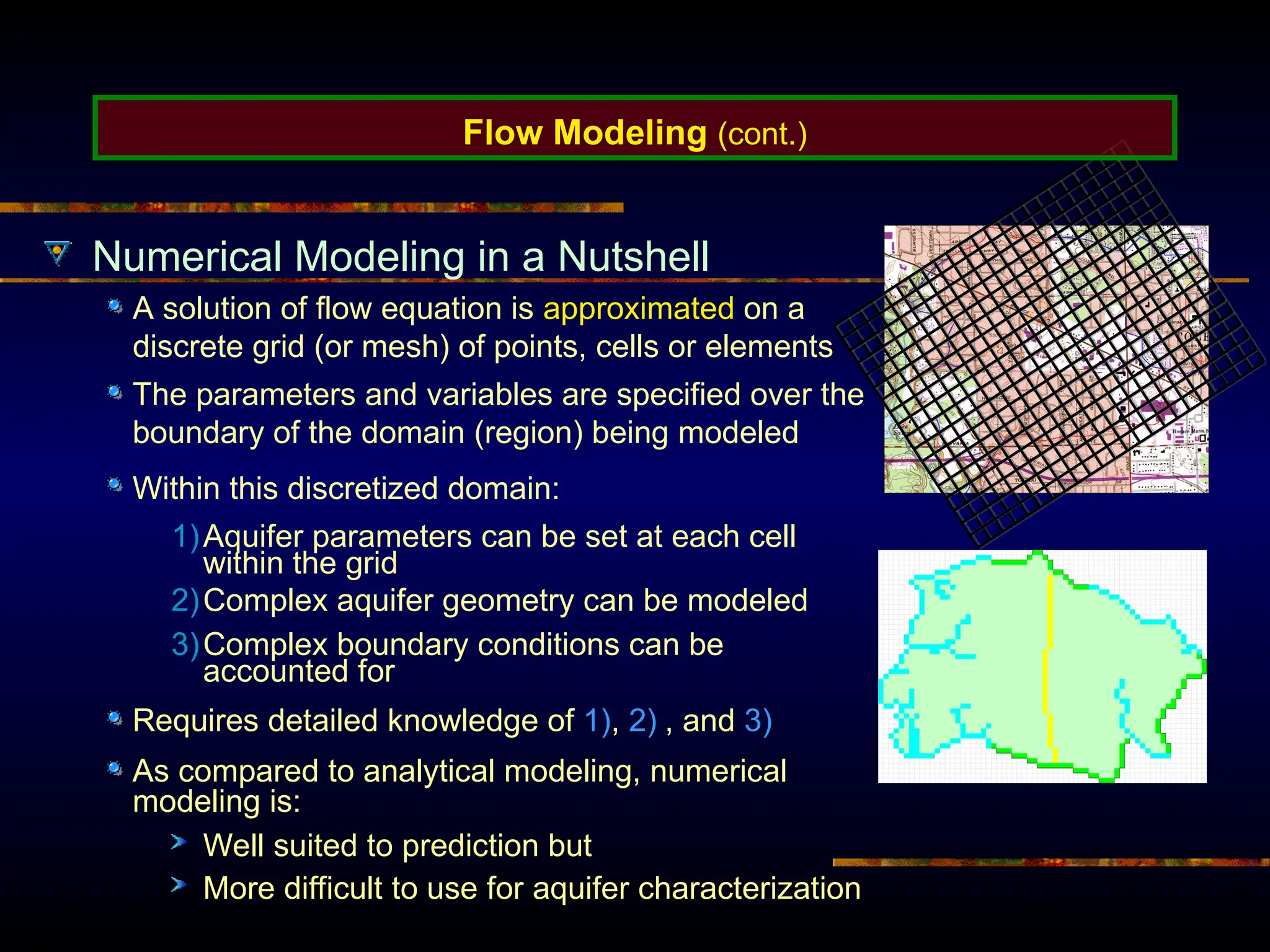

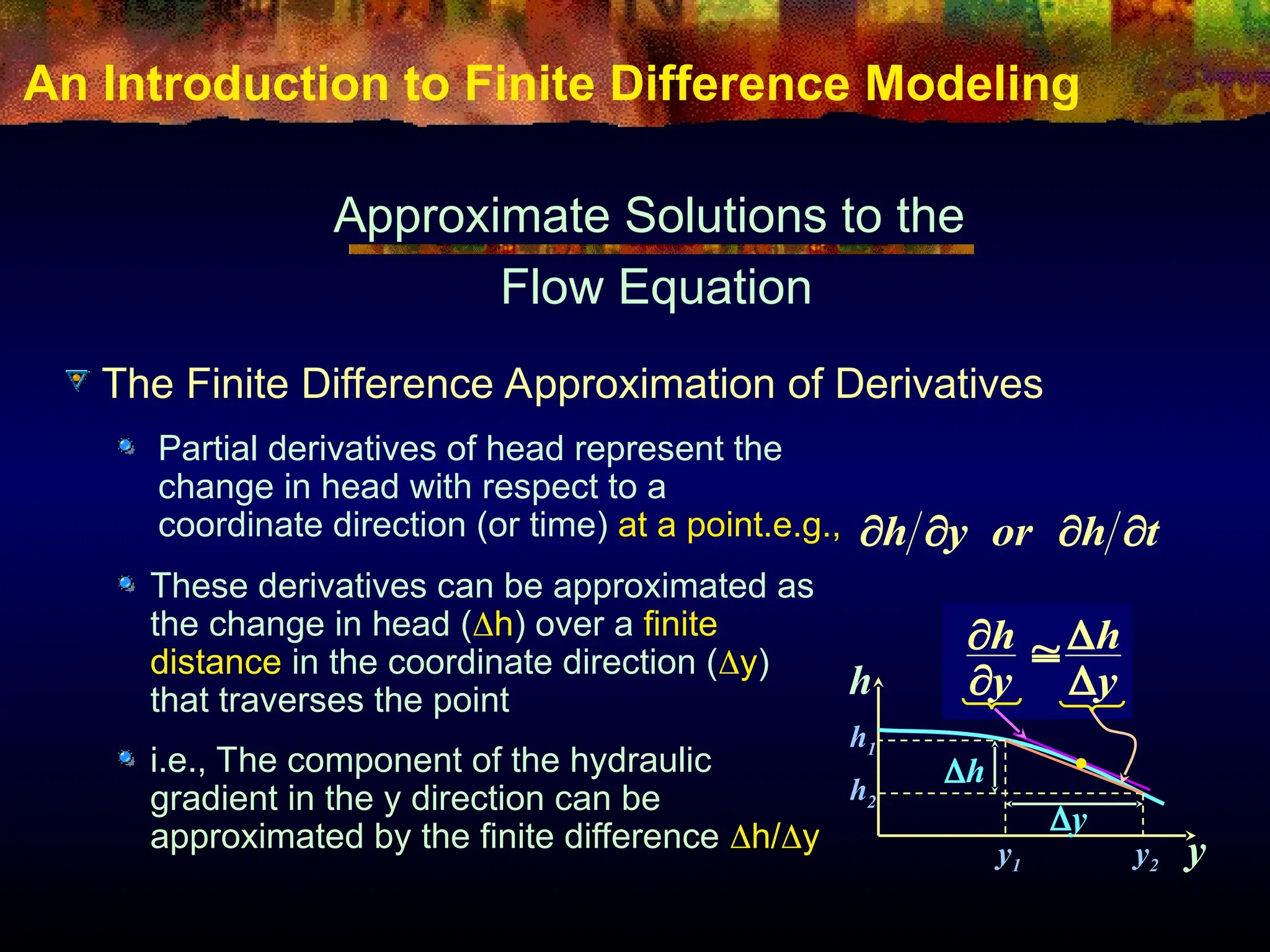

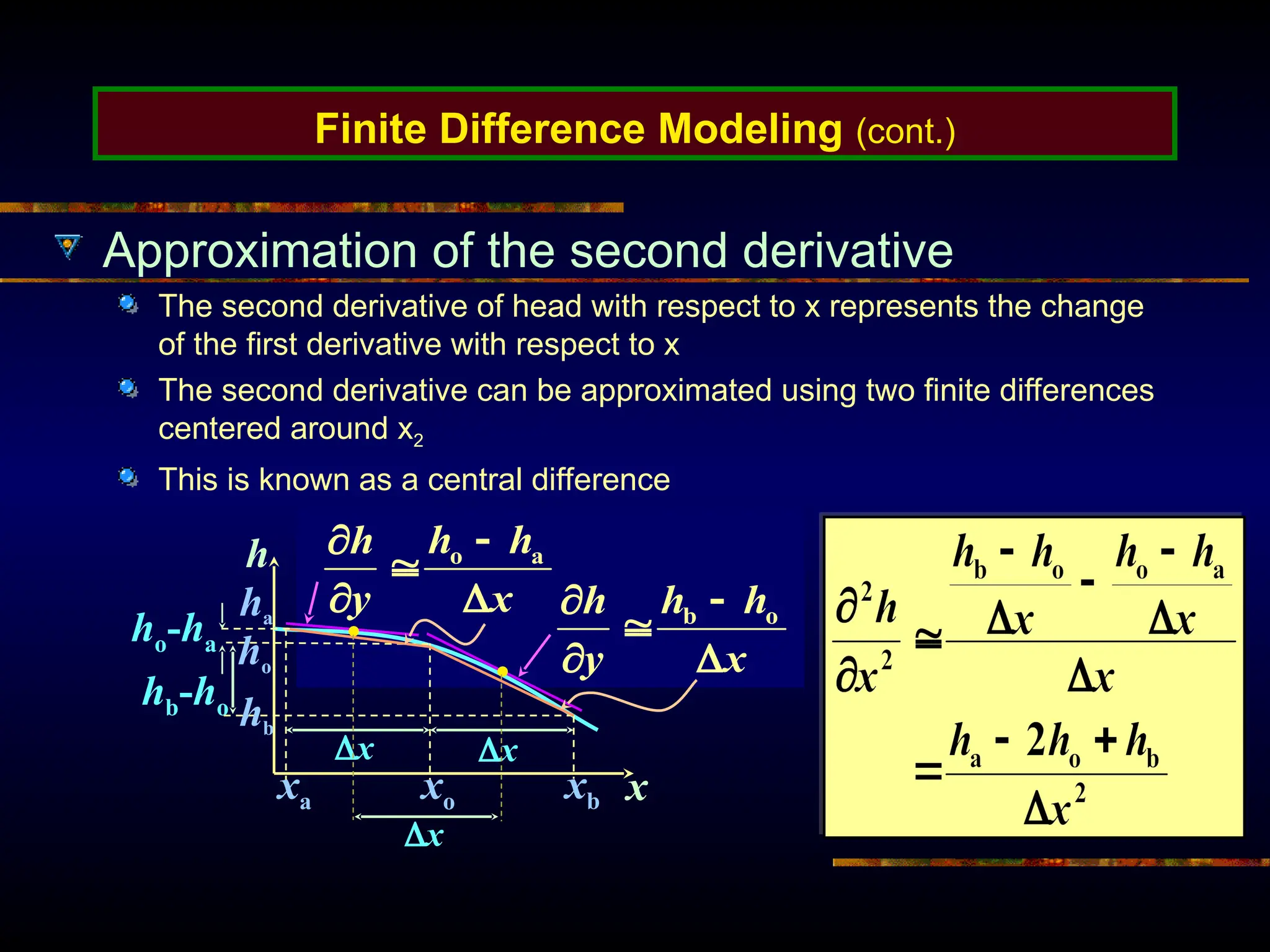

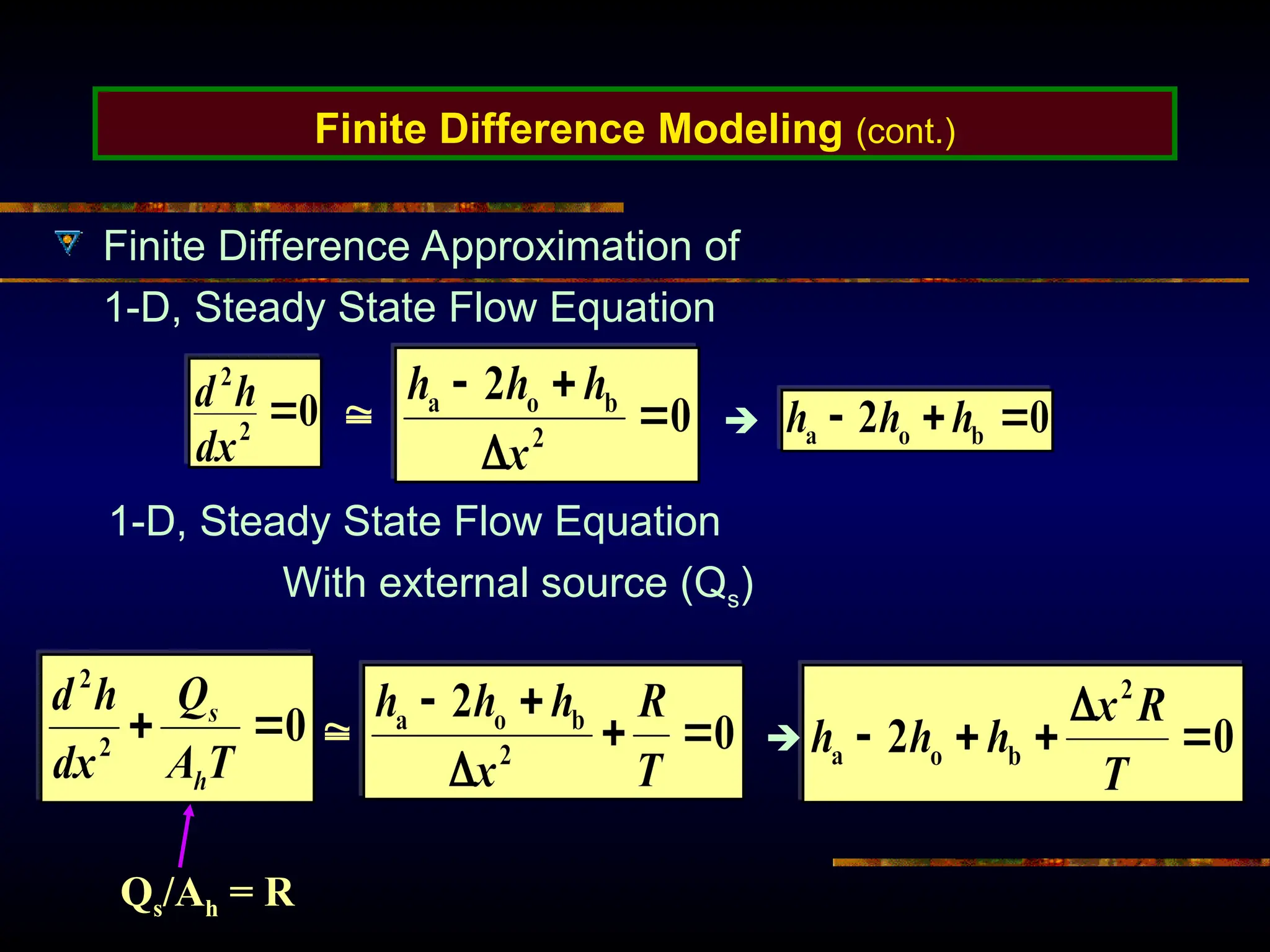

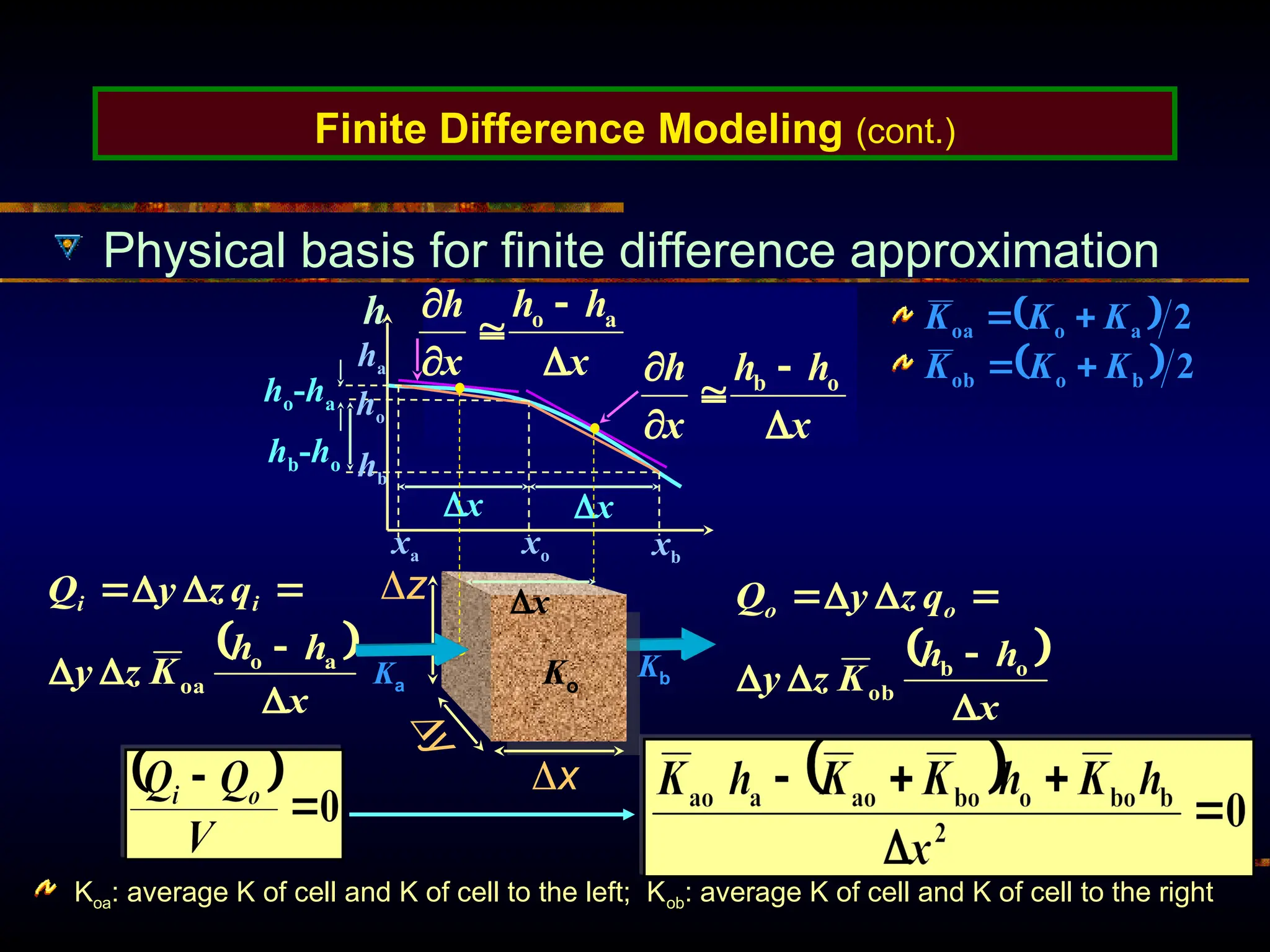

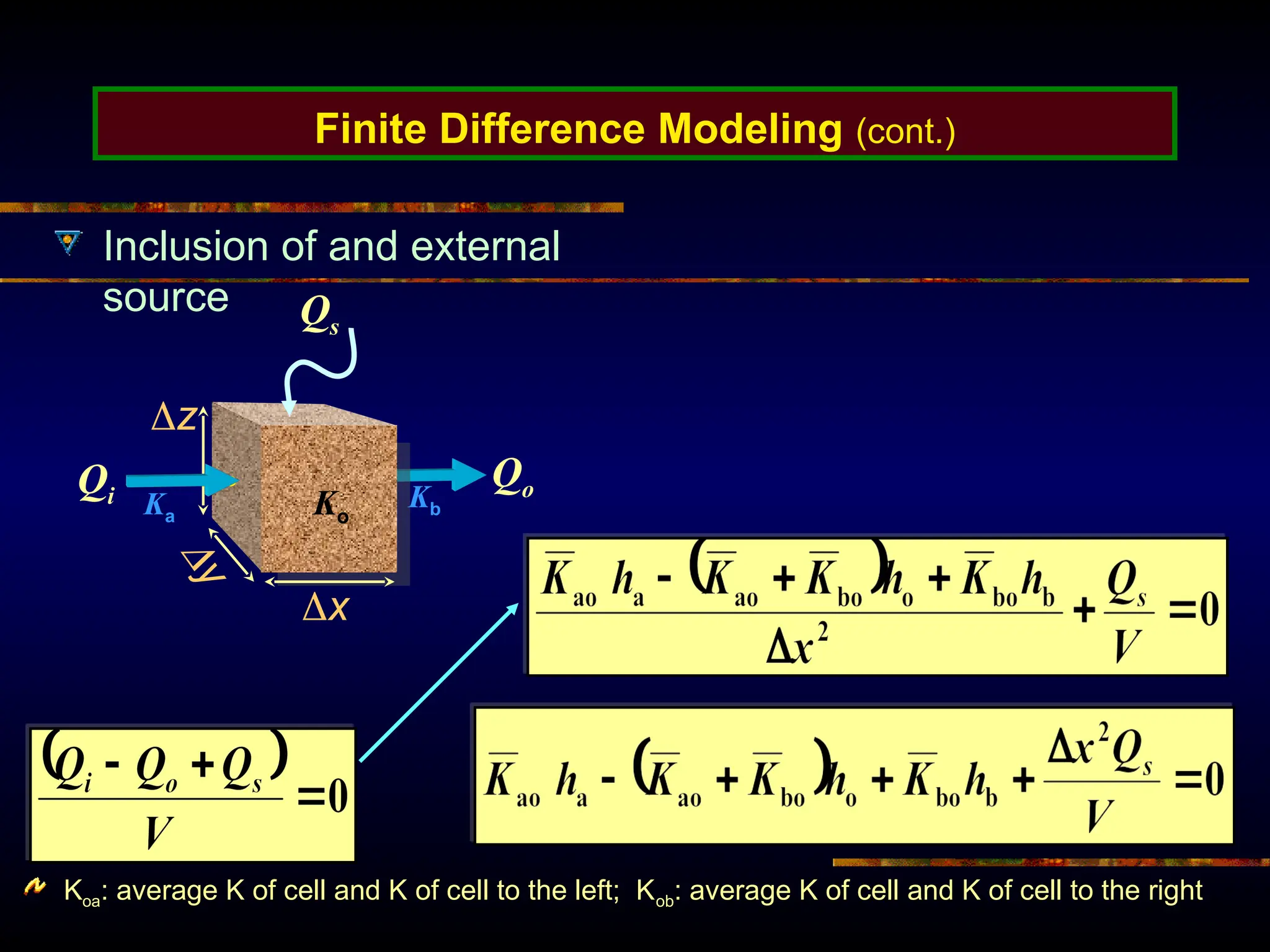

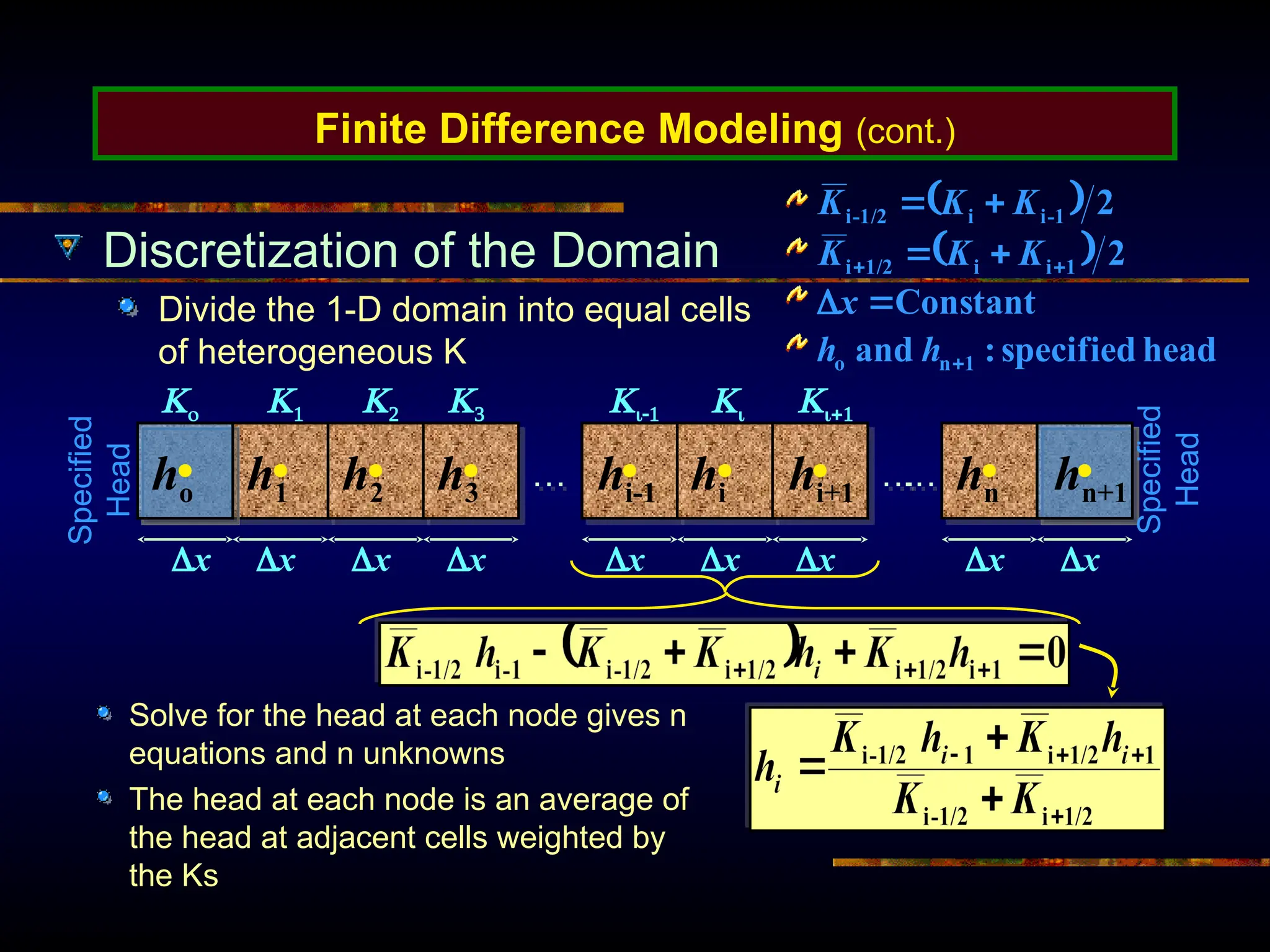

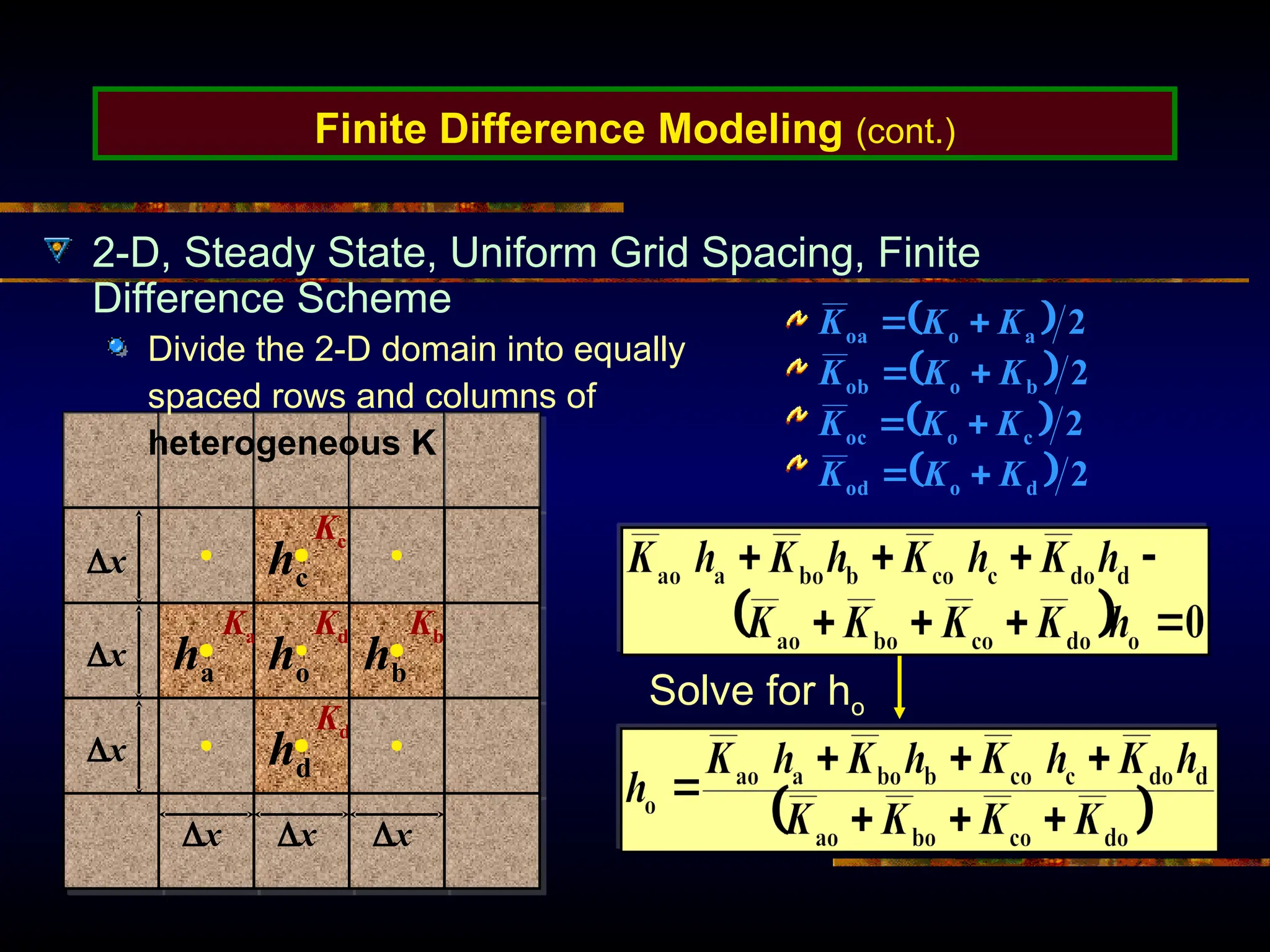

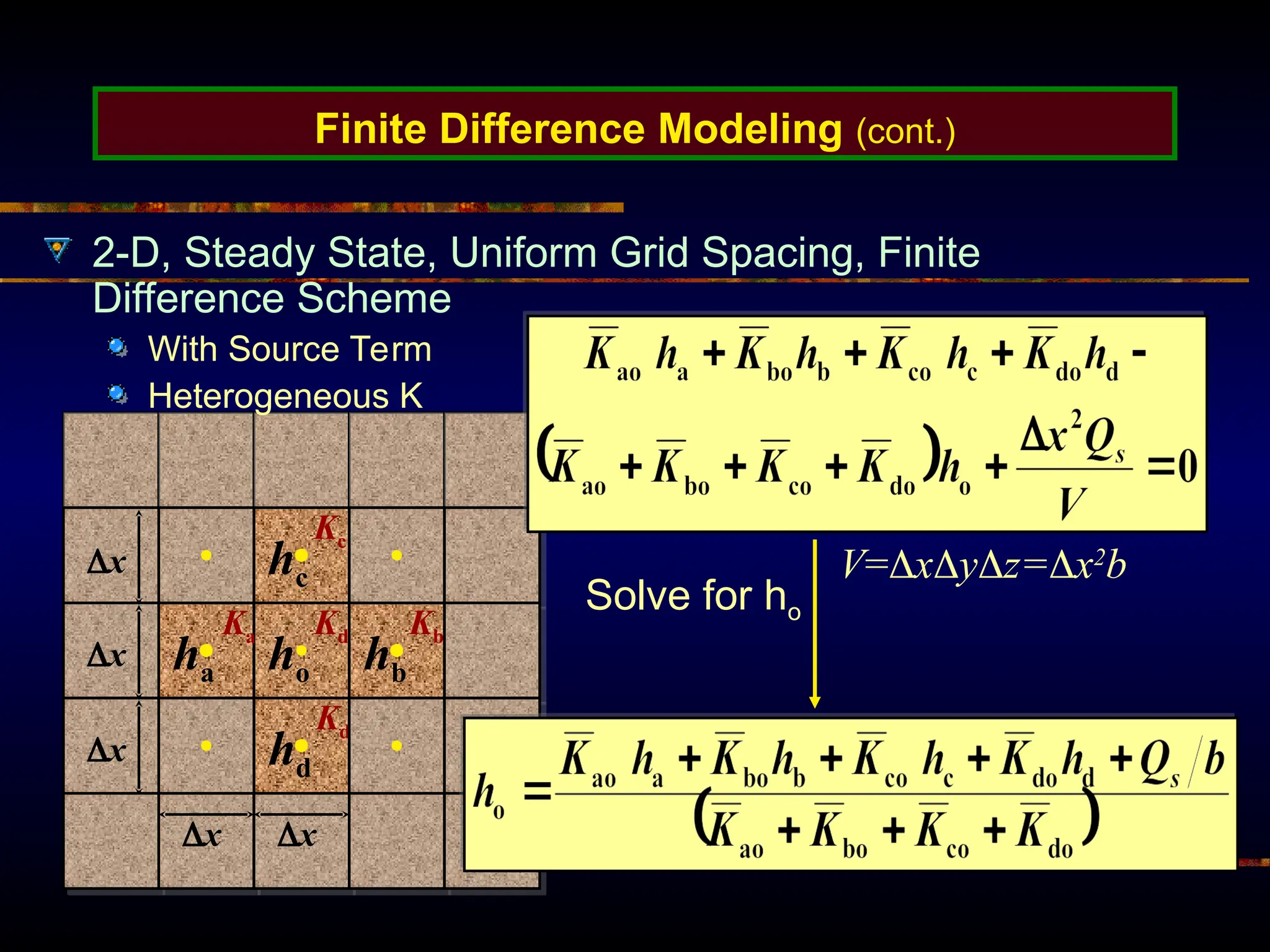

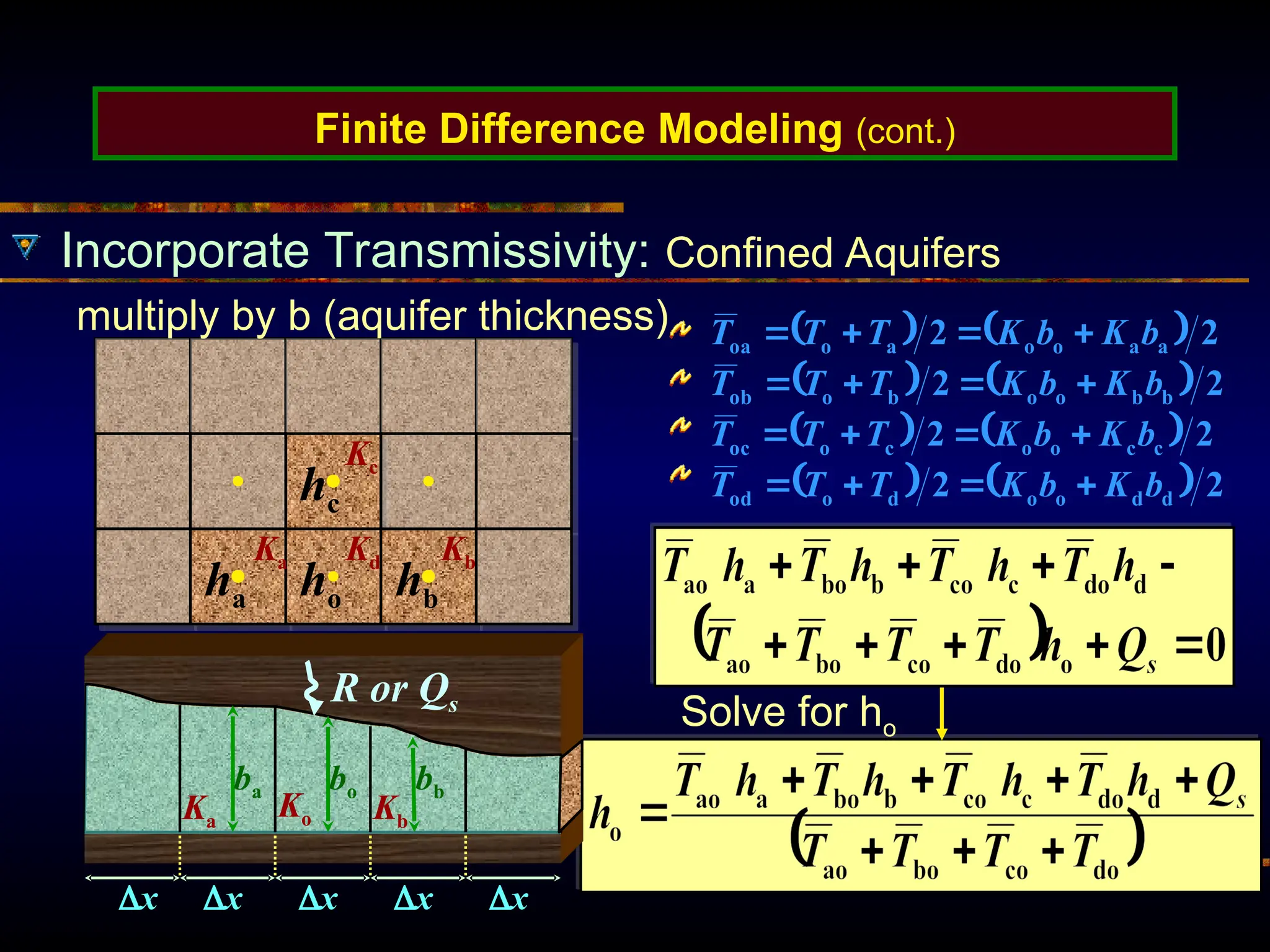

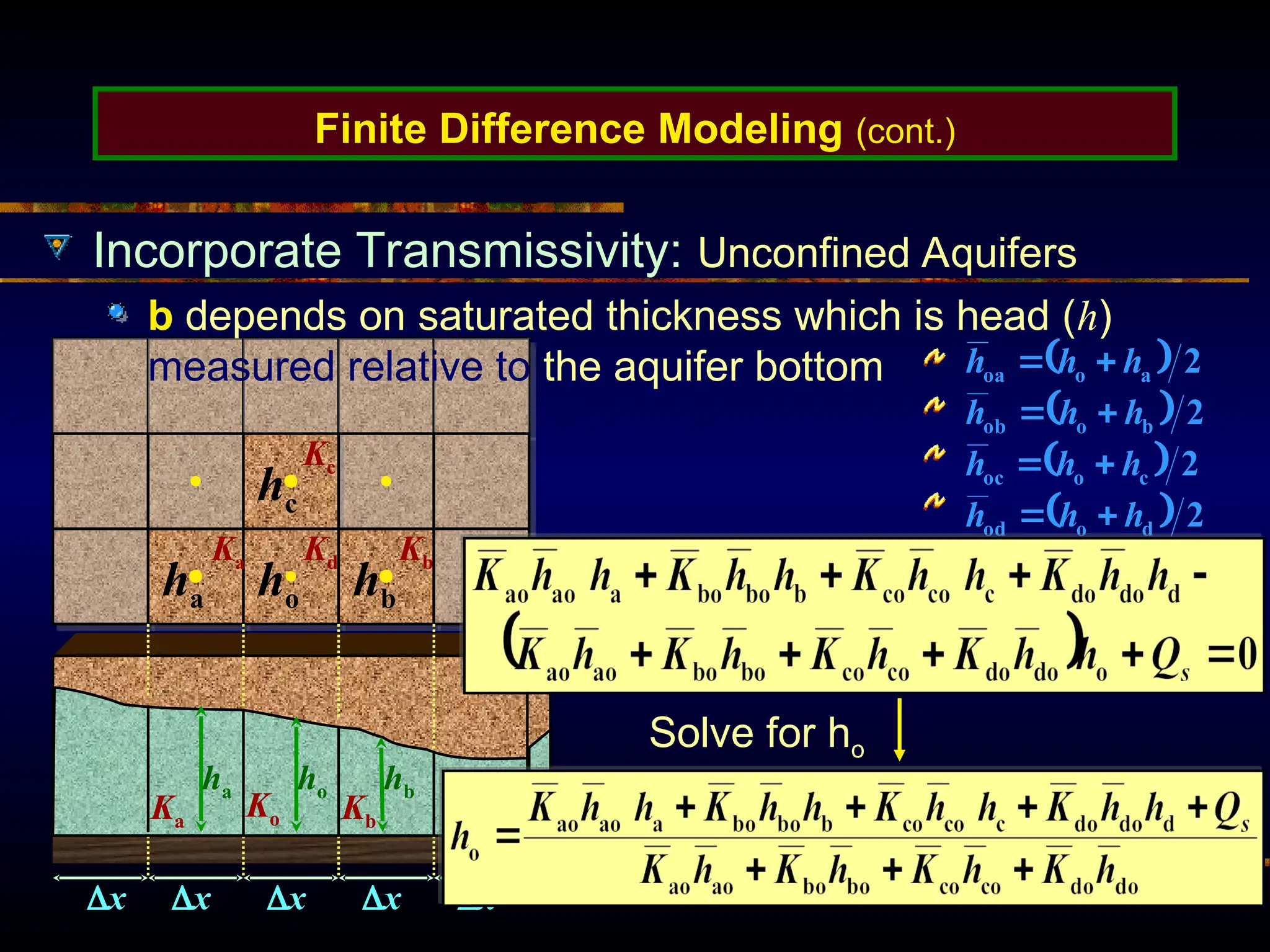

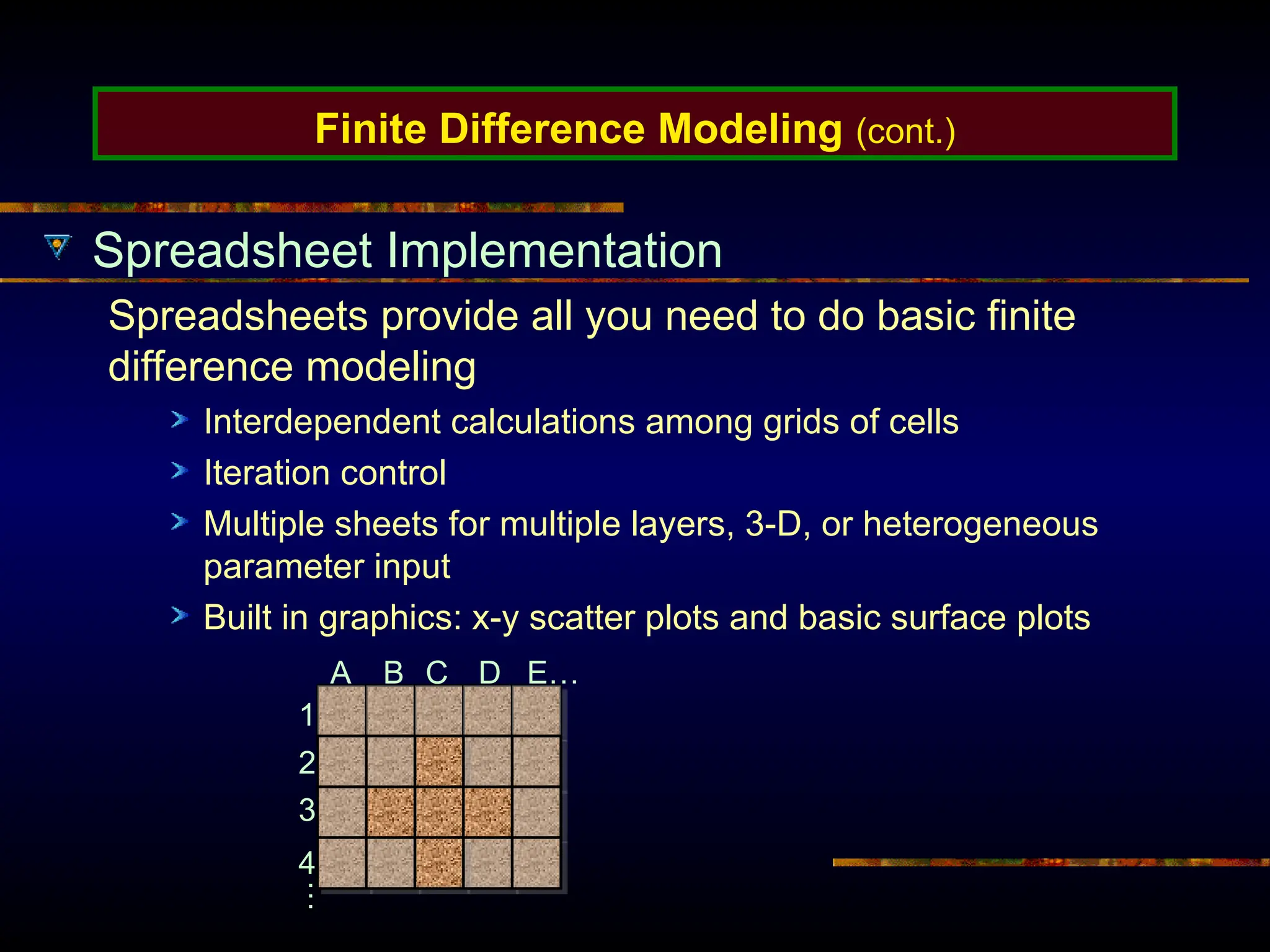

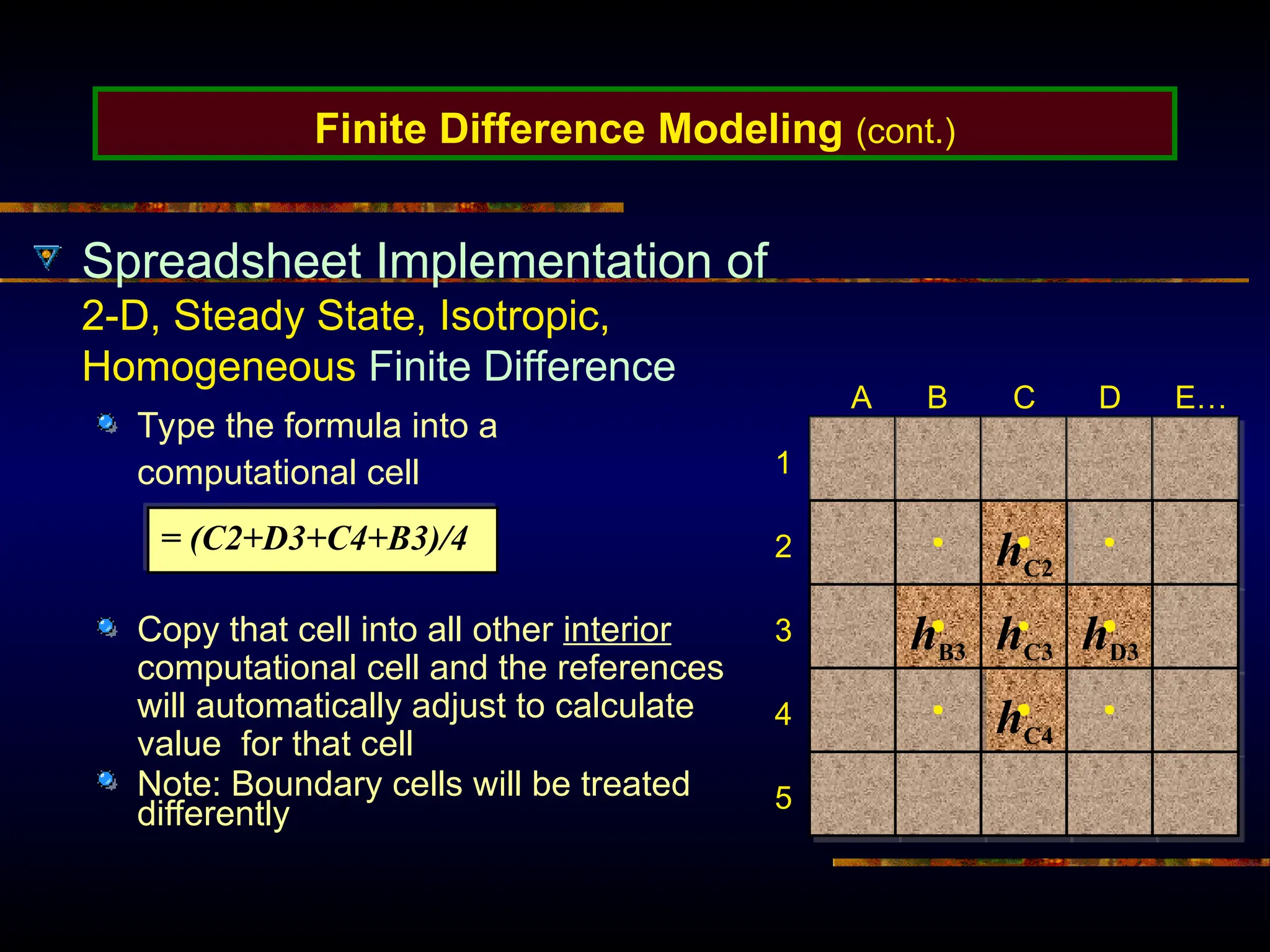

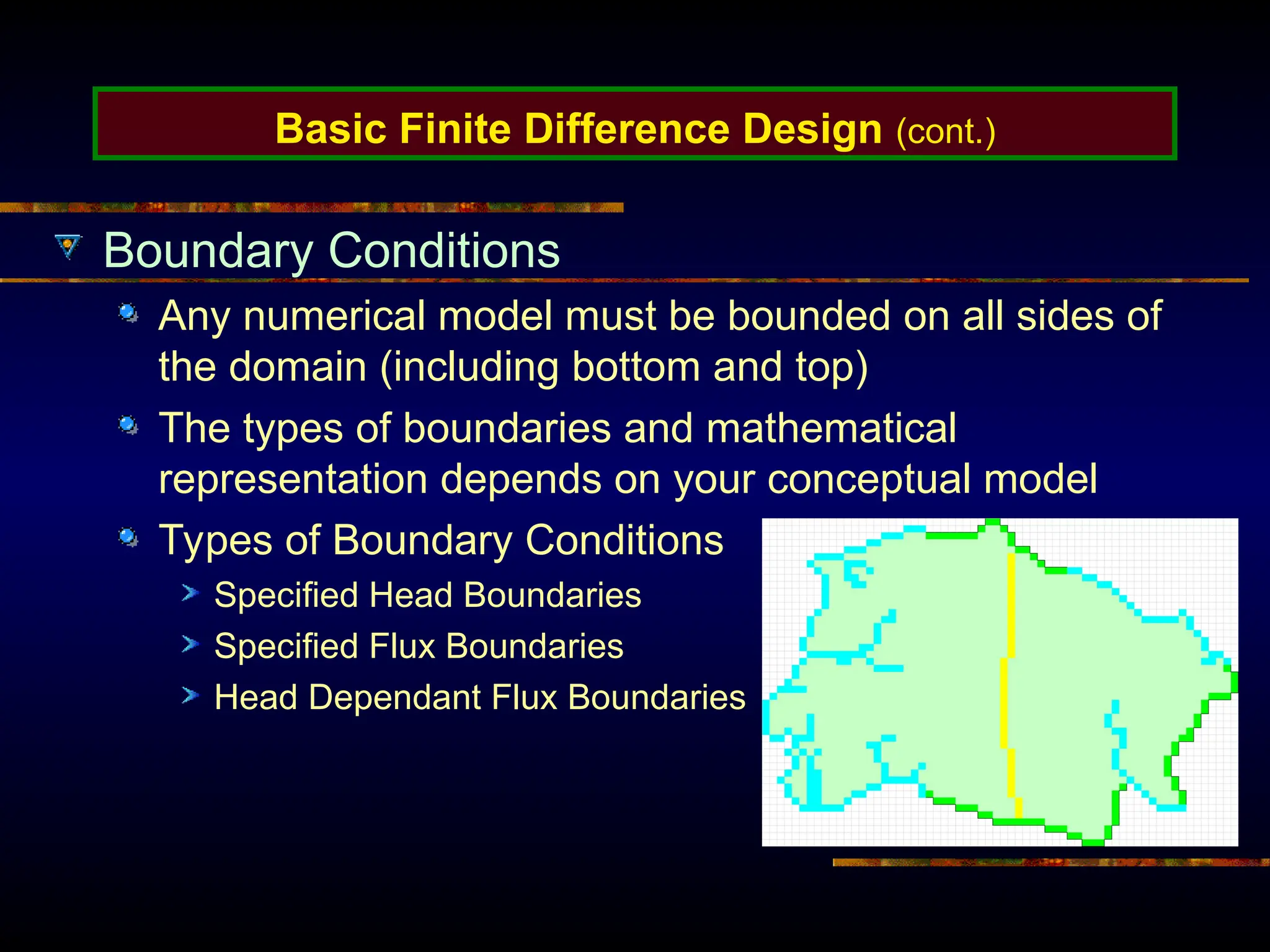

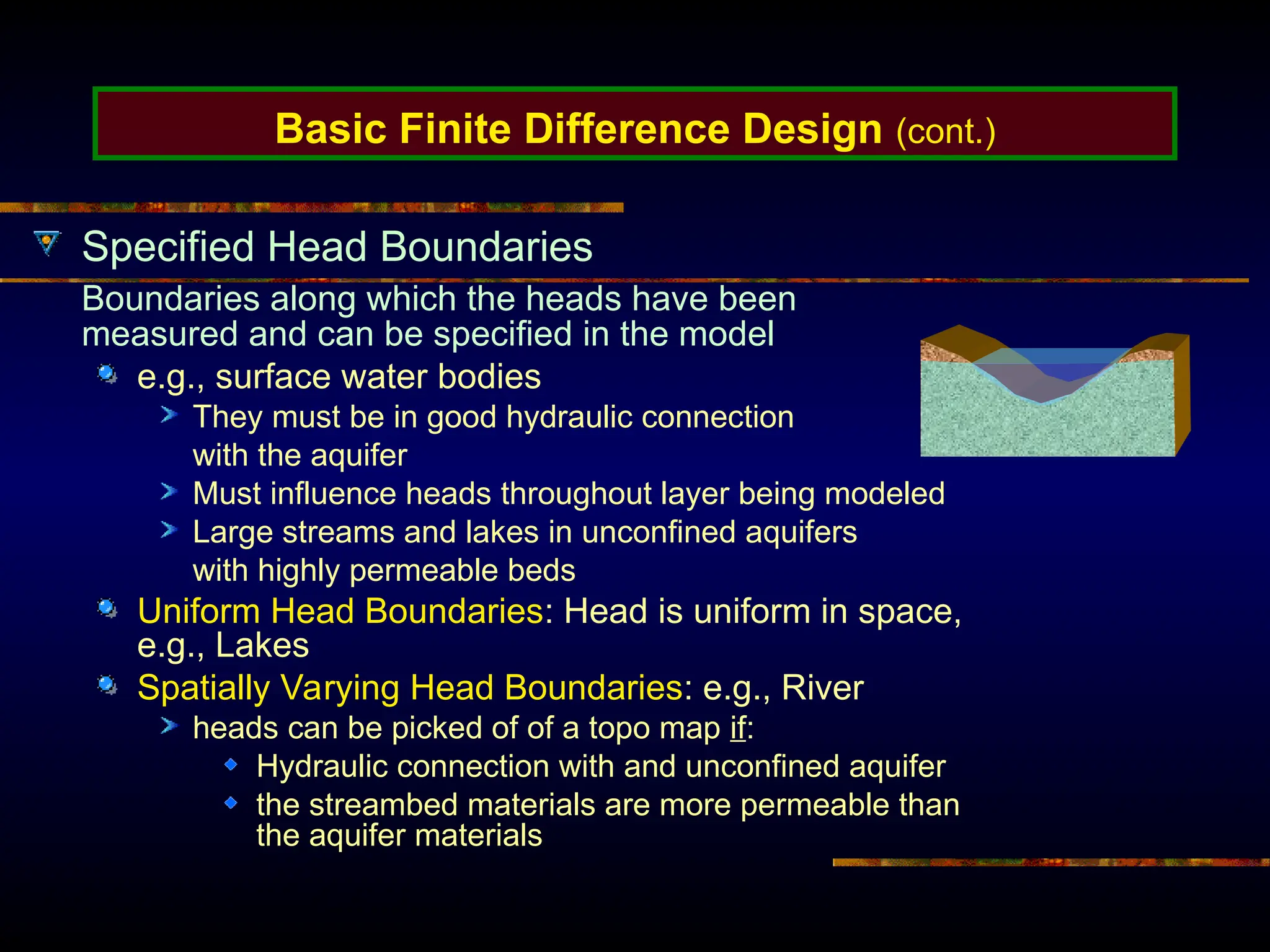

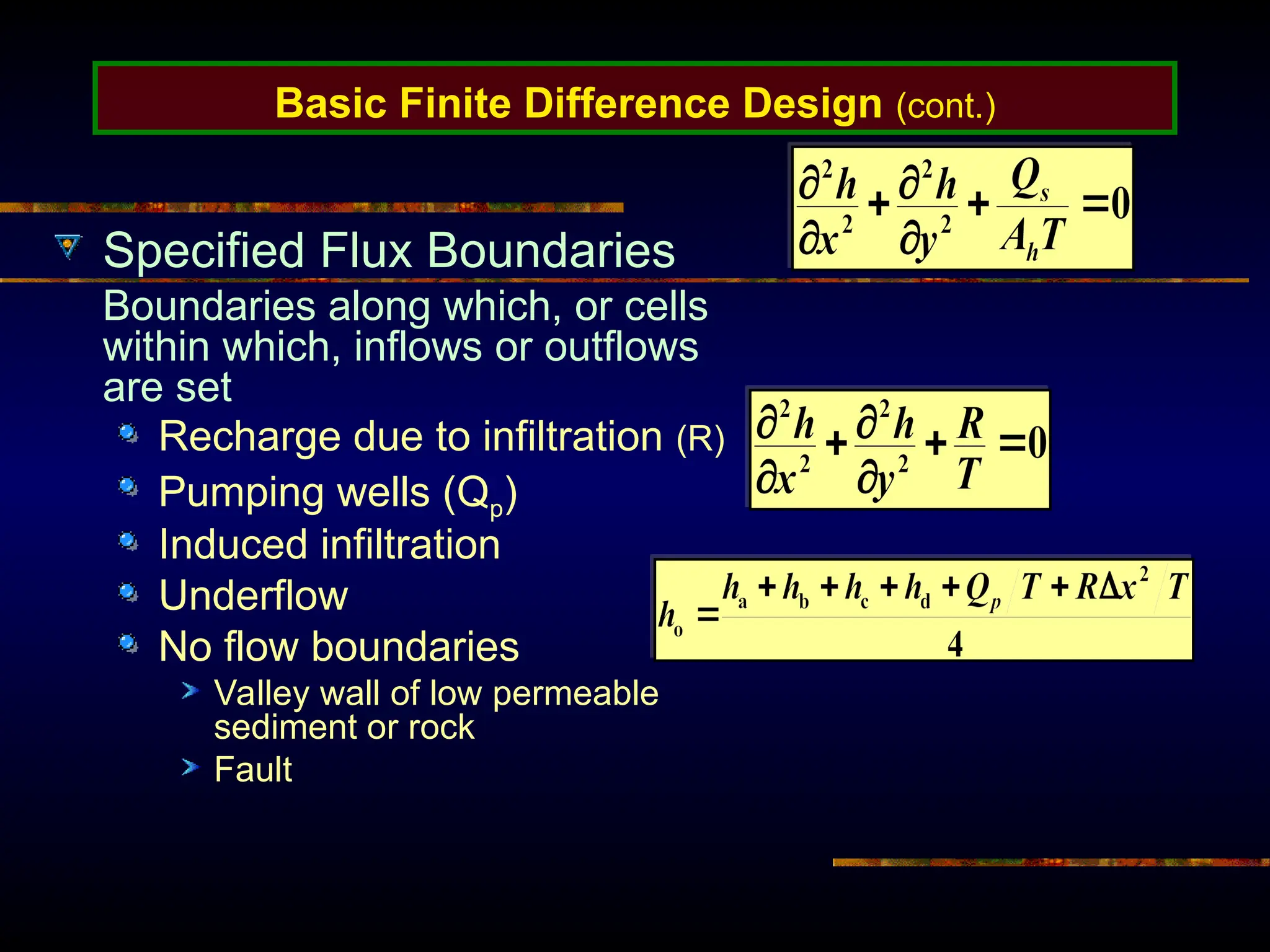

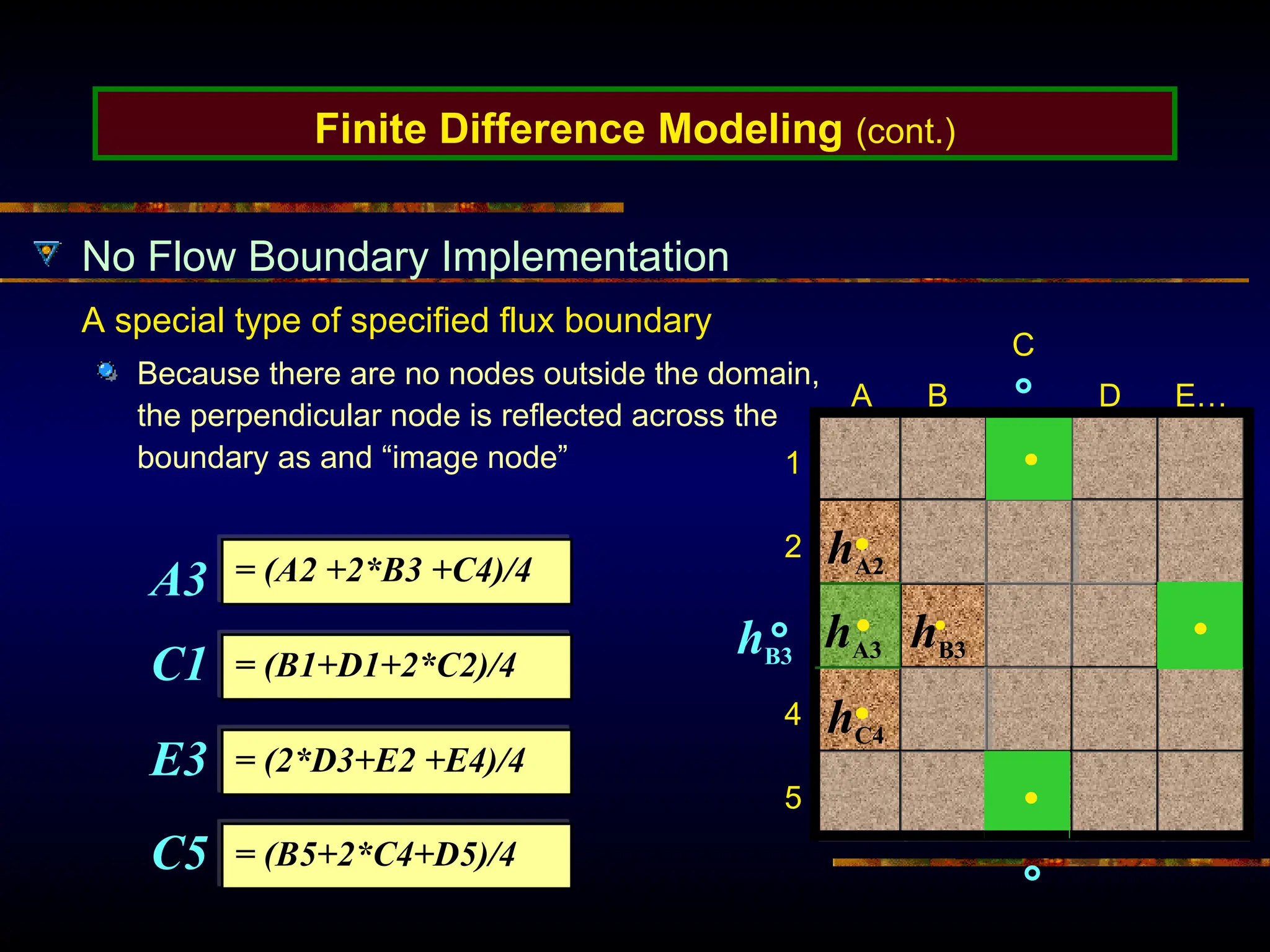

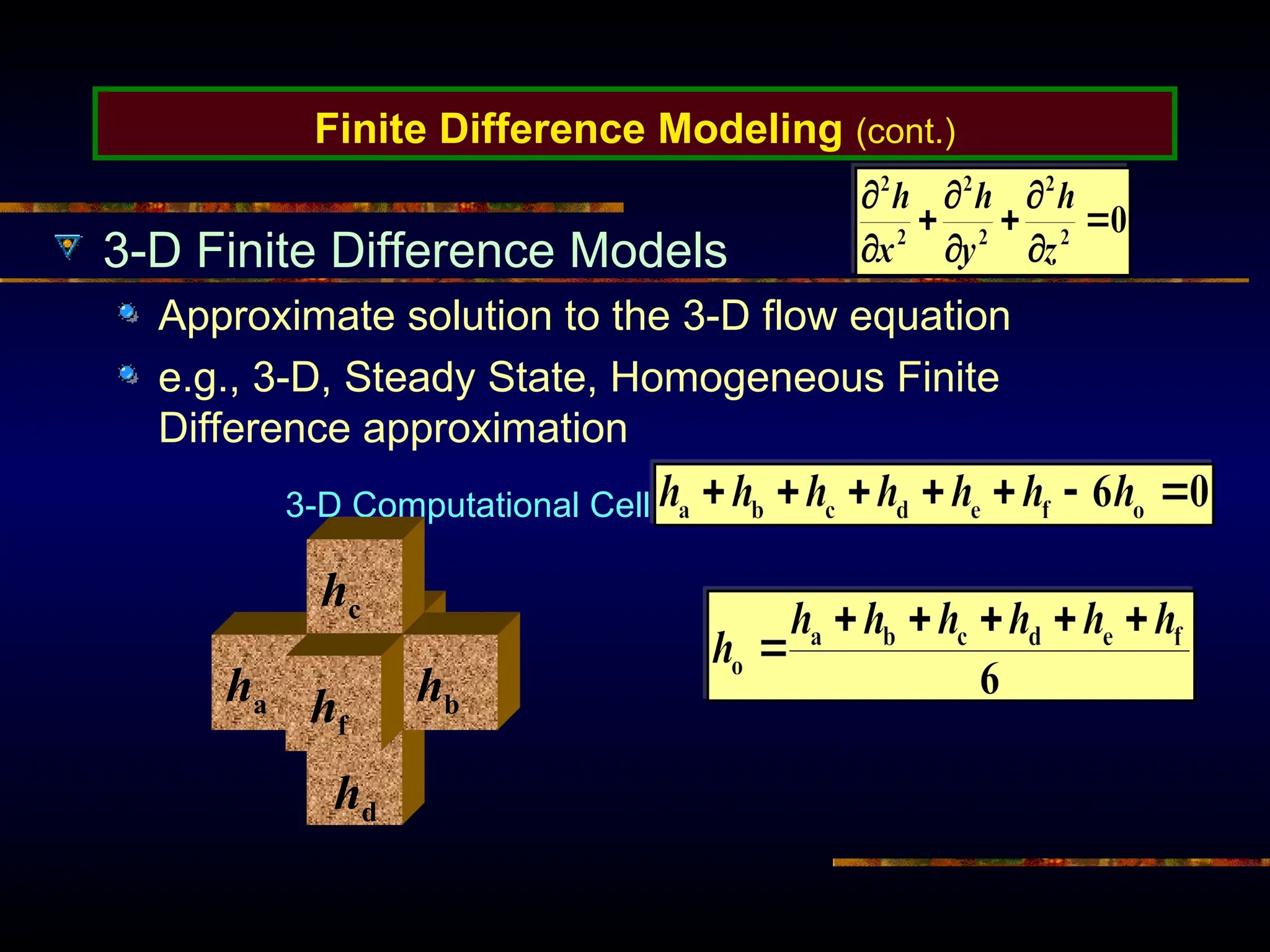

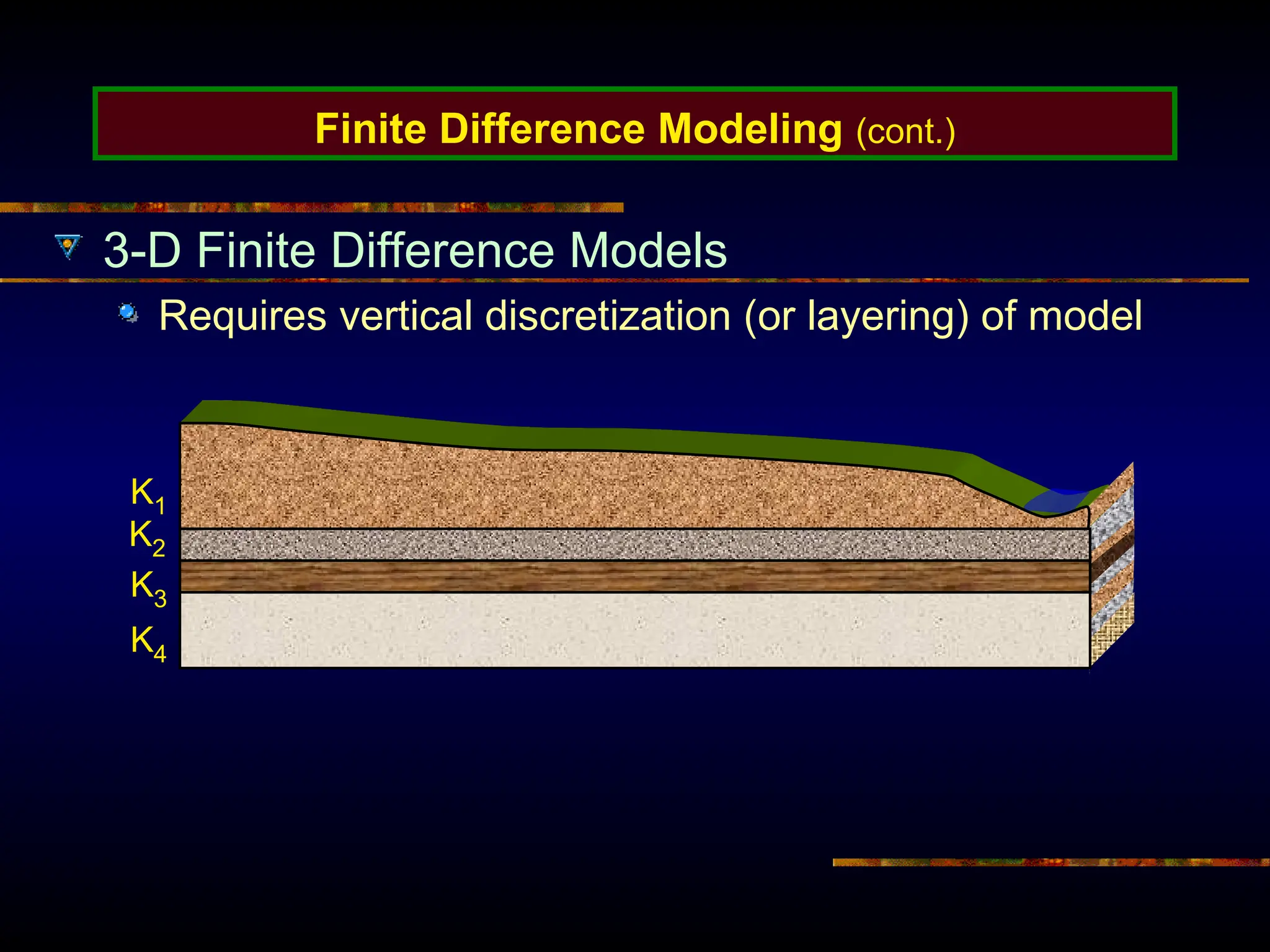

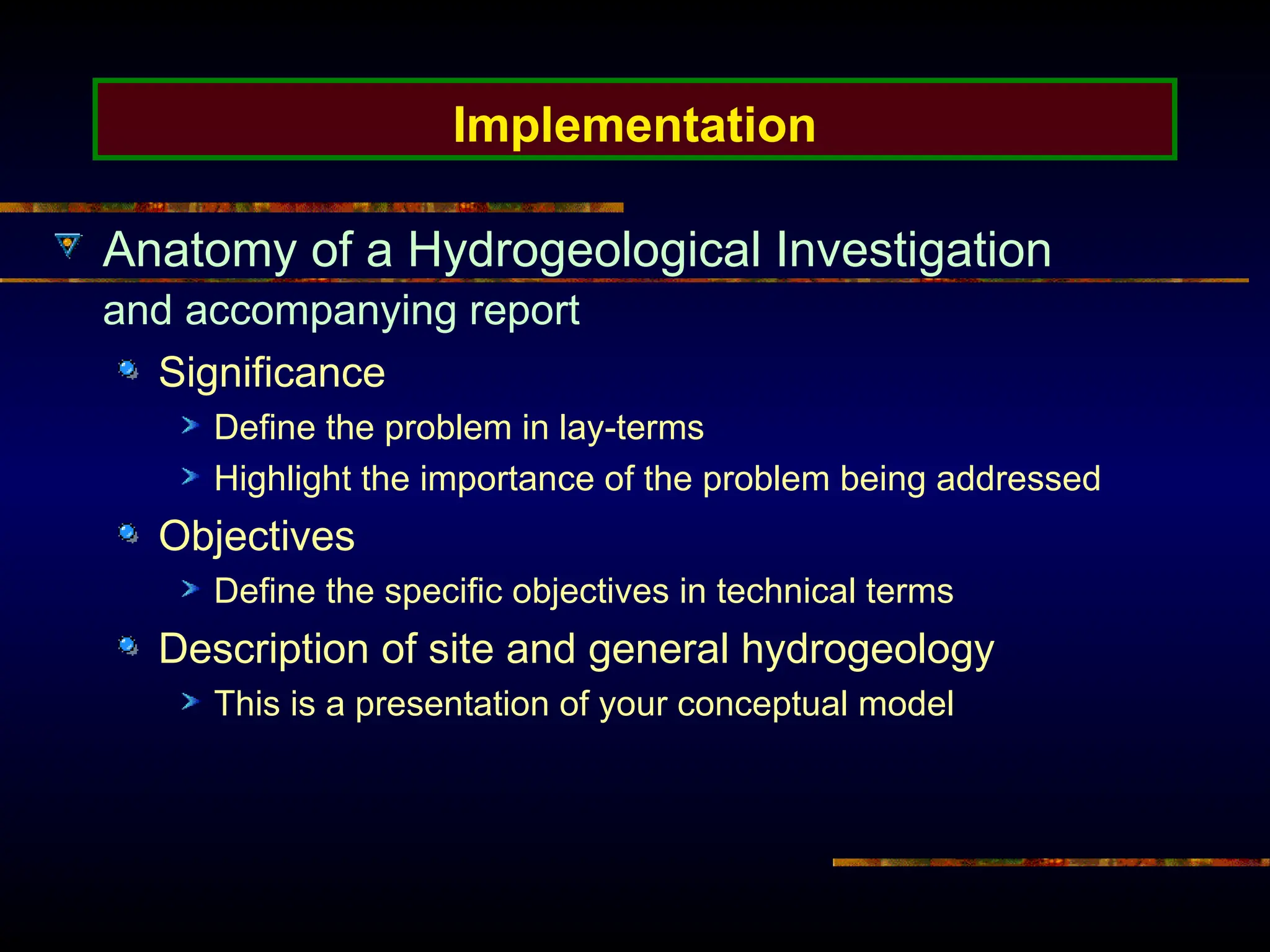

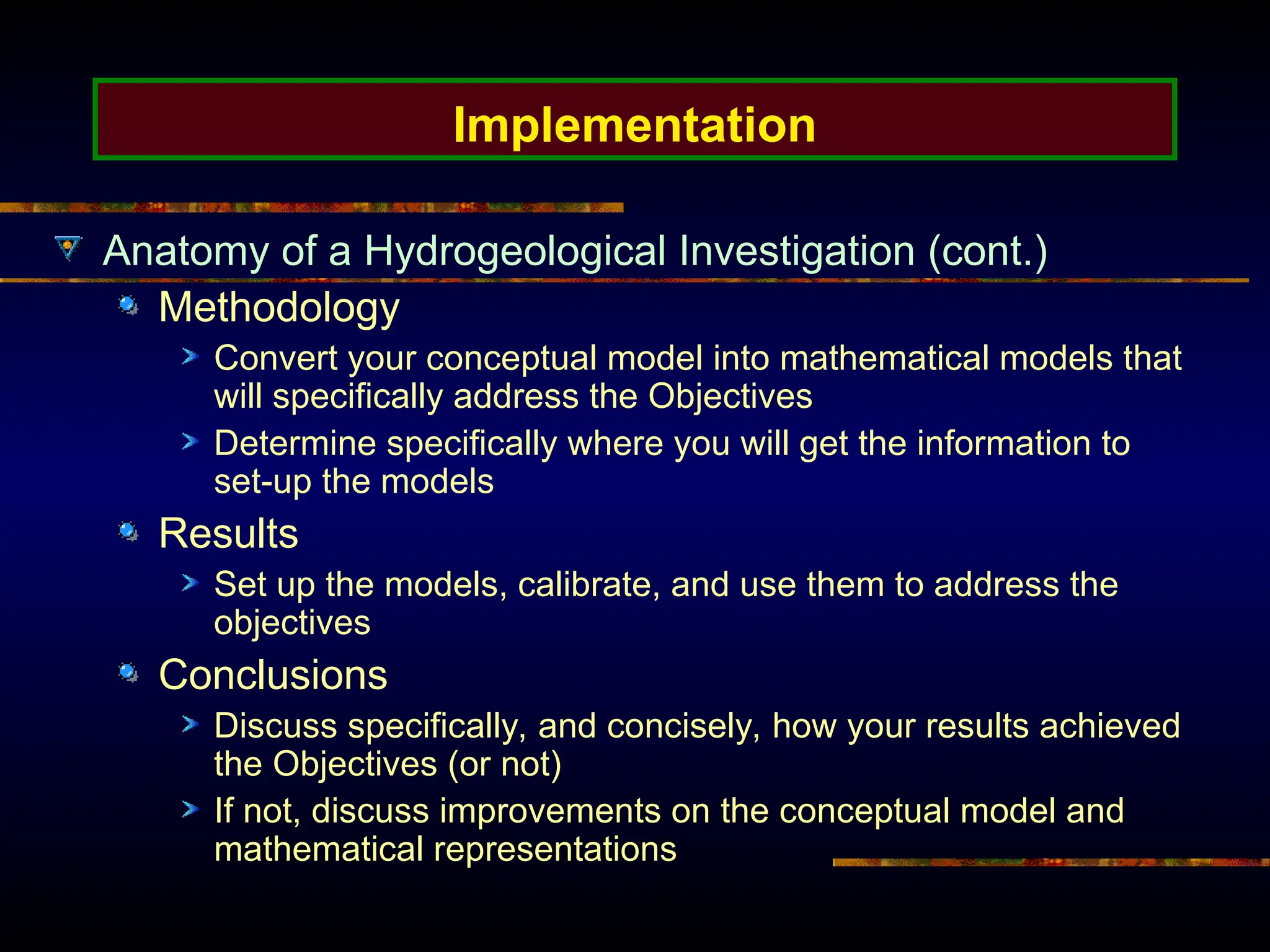

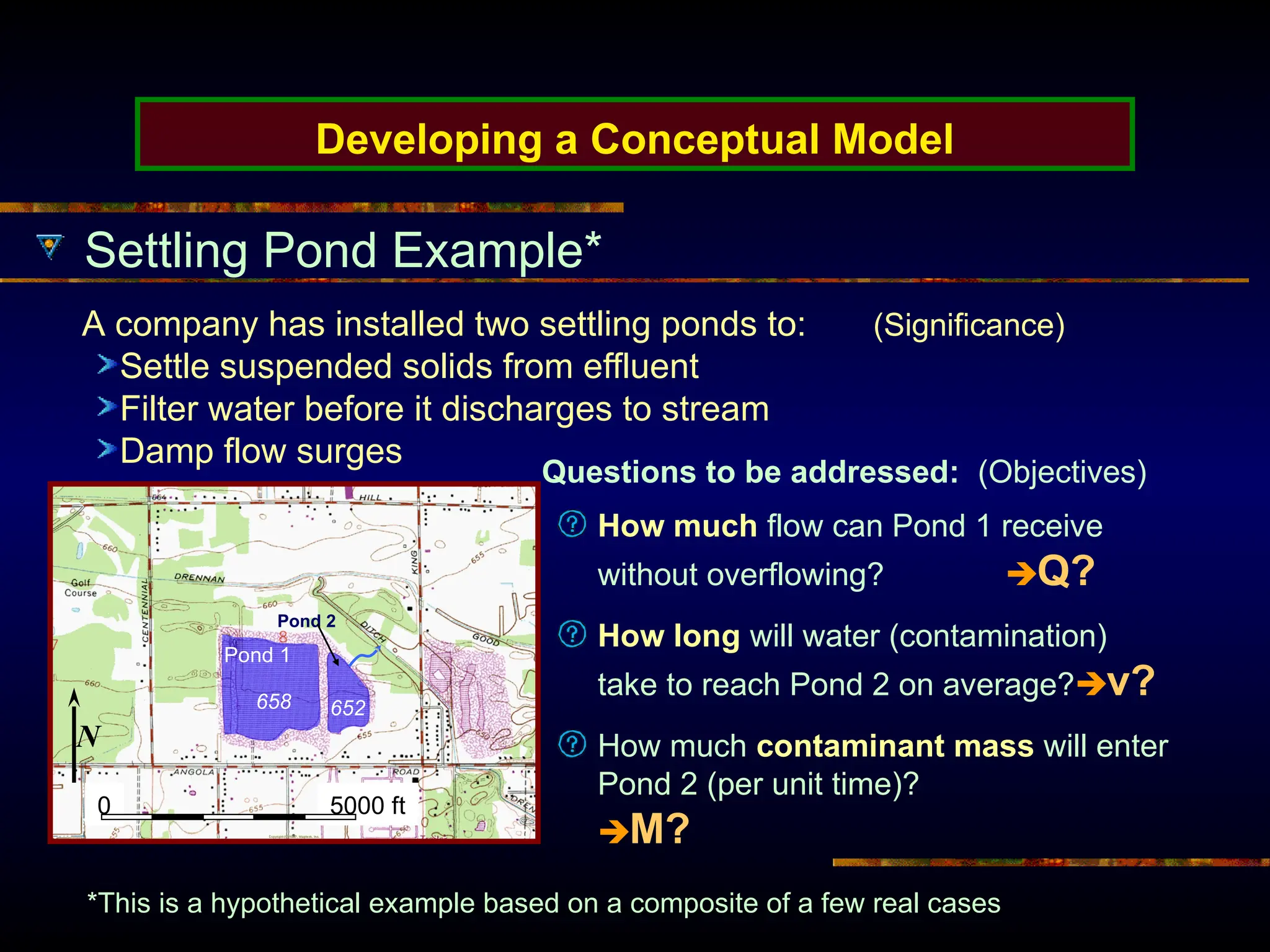

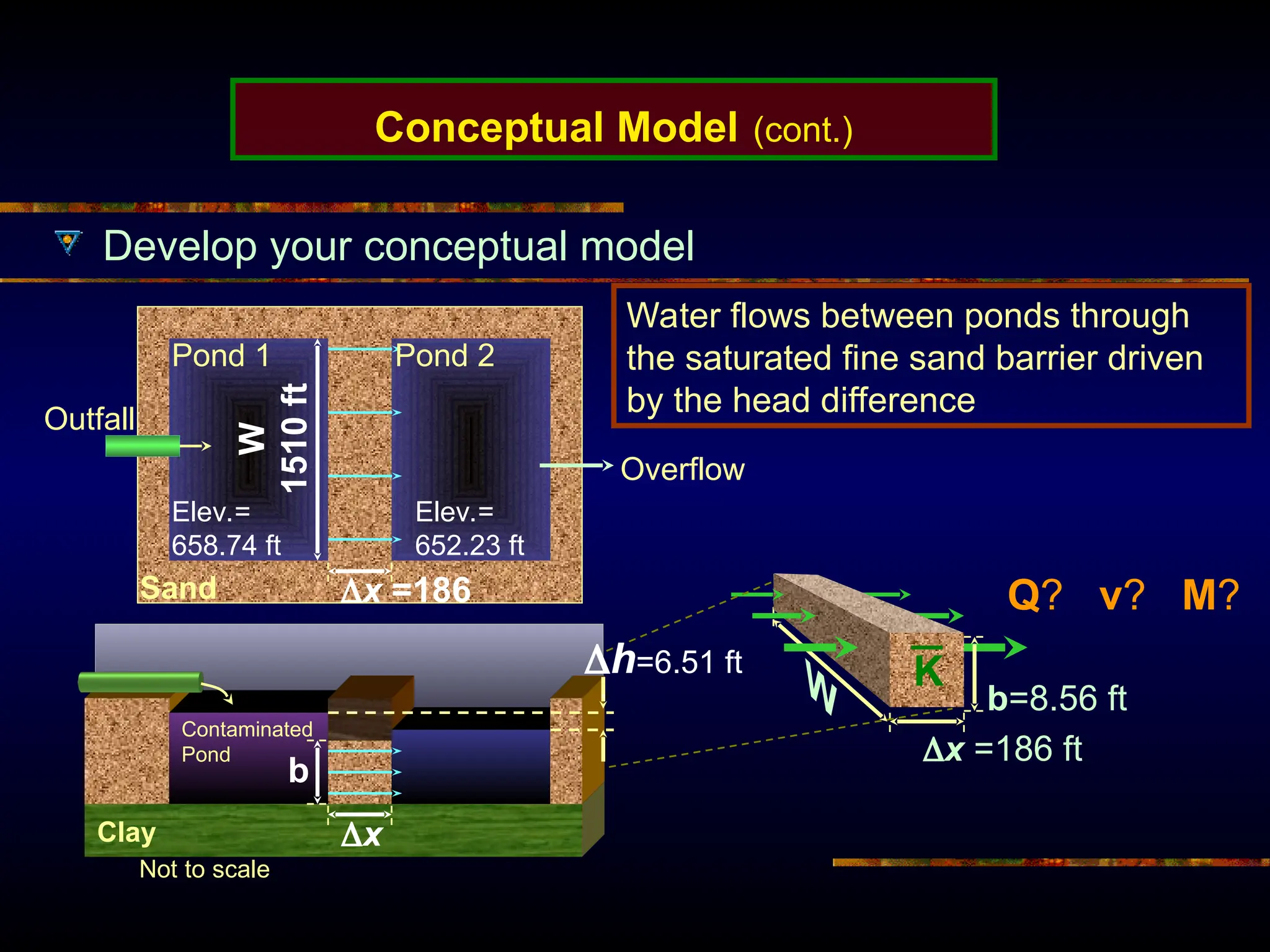

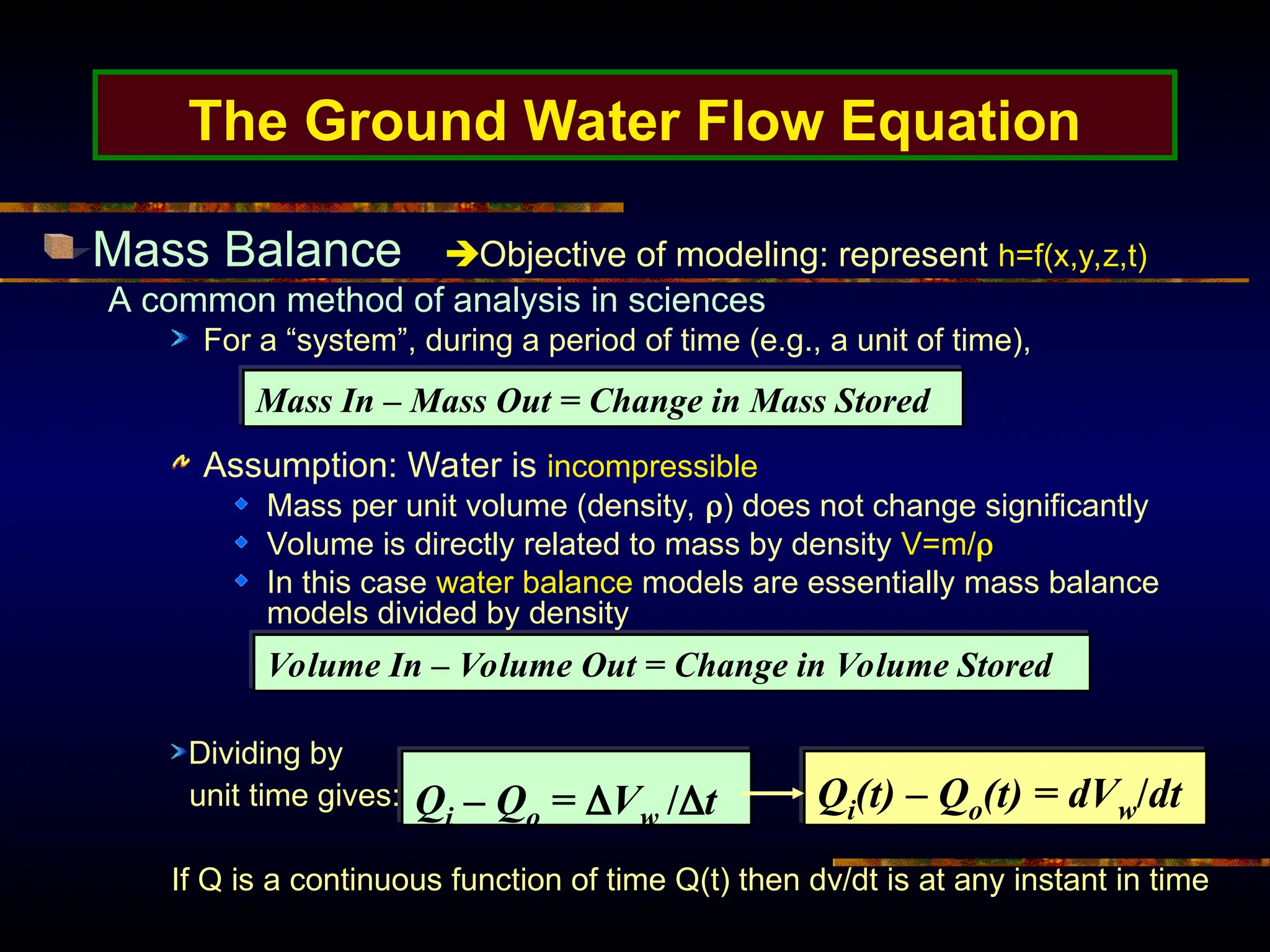

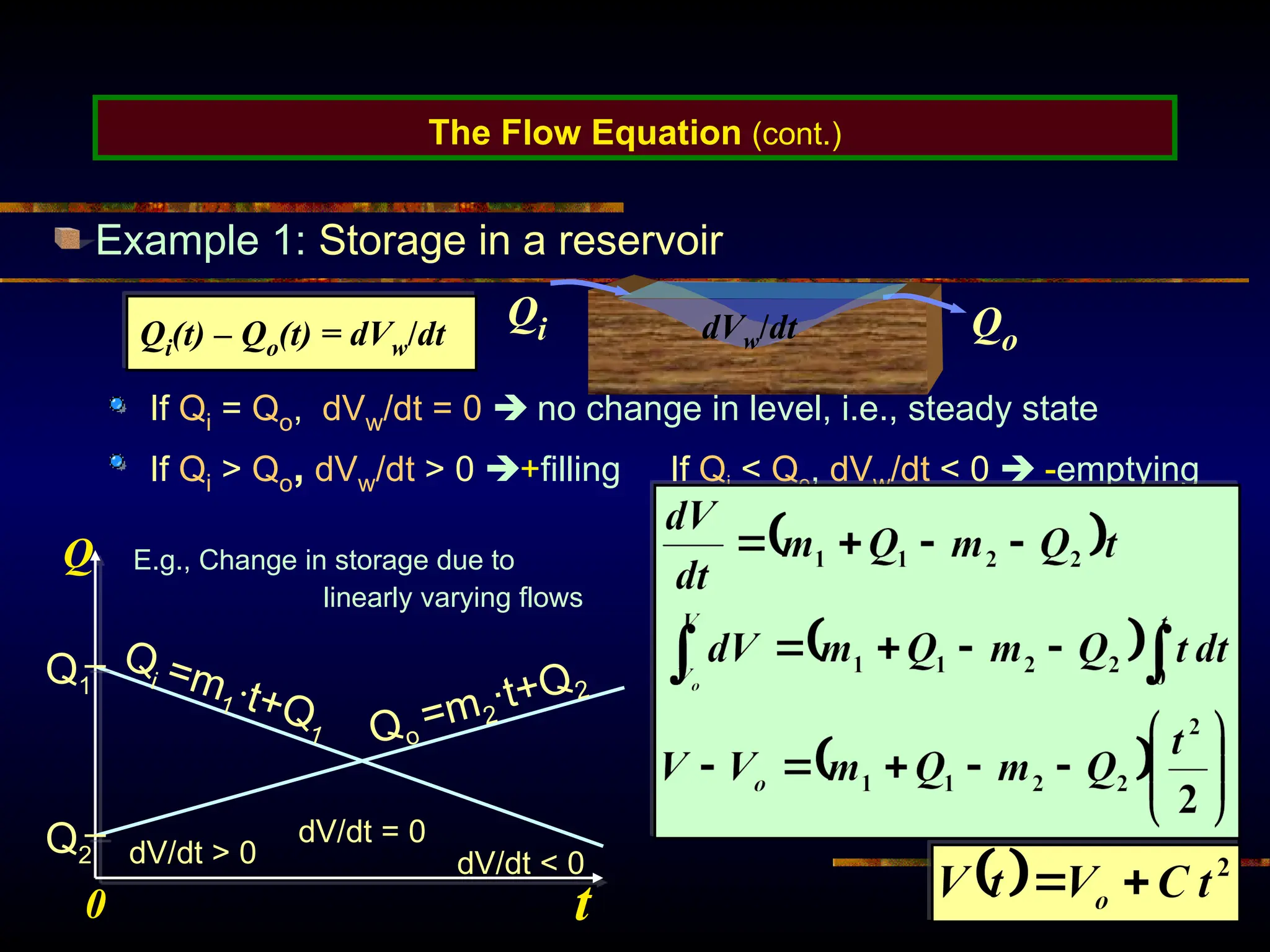

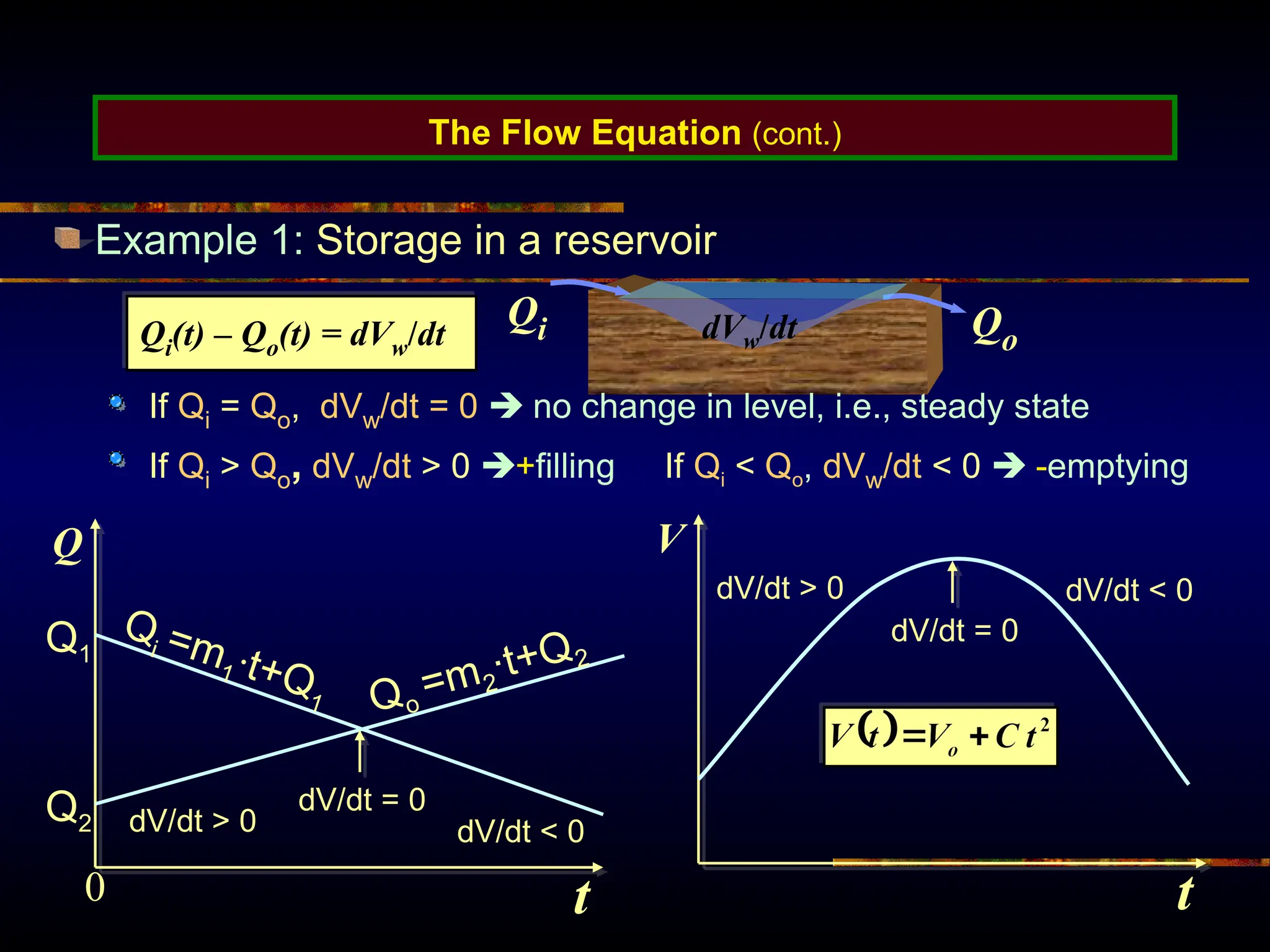

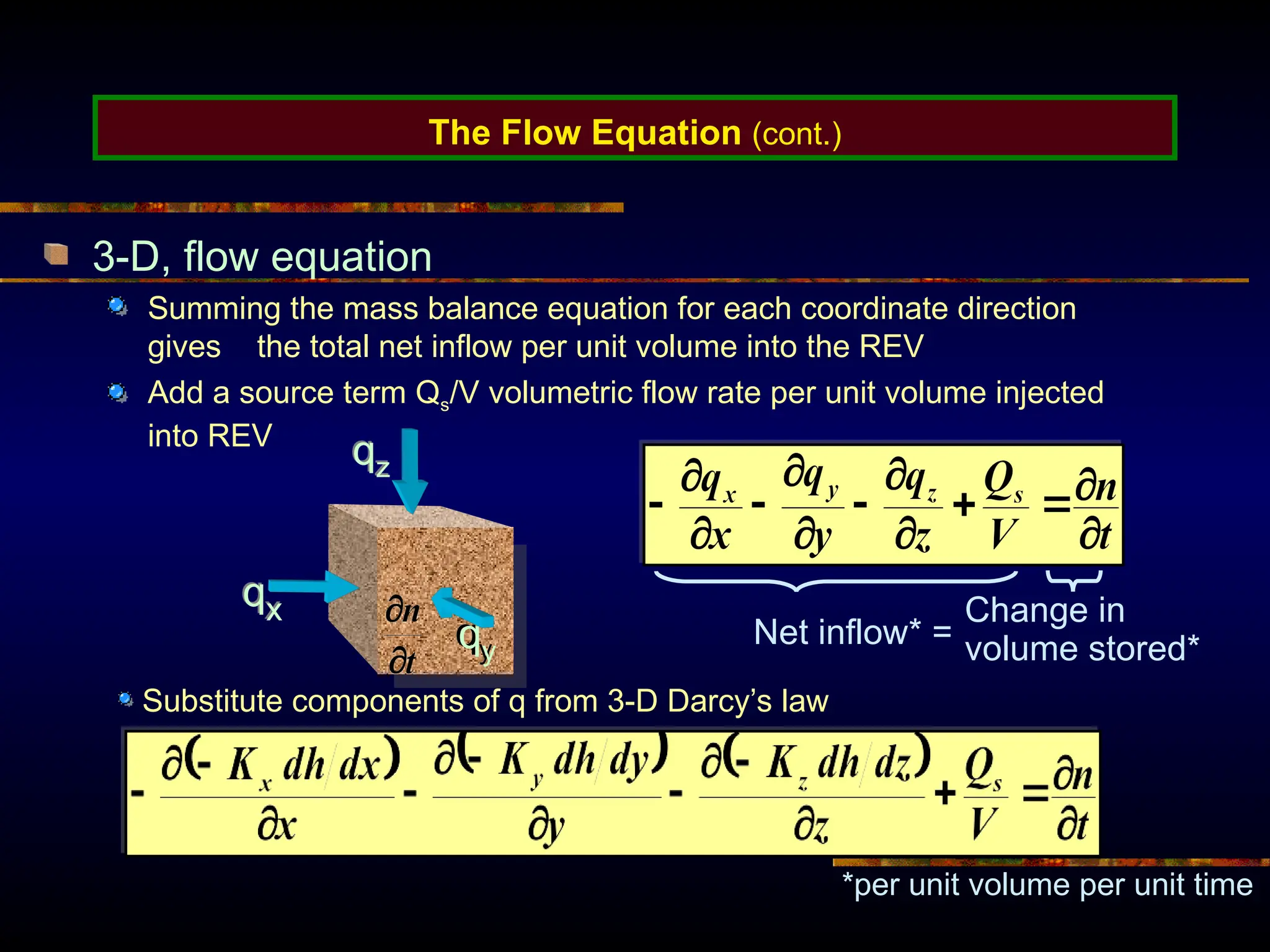

The document provides an introduction to ground water flow modeling, emphasizing the importance of the mass balance equation and the flow equation in modeling strategies. It discusses analytical and numerical methods for solving flow equations, including forward and inverse modeling, as well as the use of finite difference methods for approximating solutions. The limitations of analytical models and the need for more complex numerical modeling to address geological complexities are also highlighted.

![The Flow Equation (cont.)

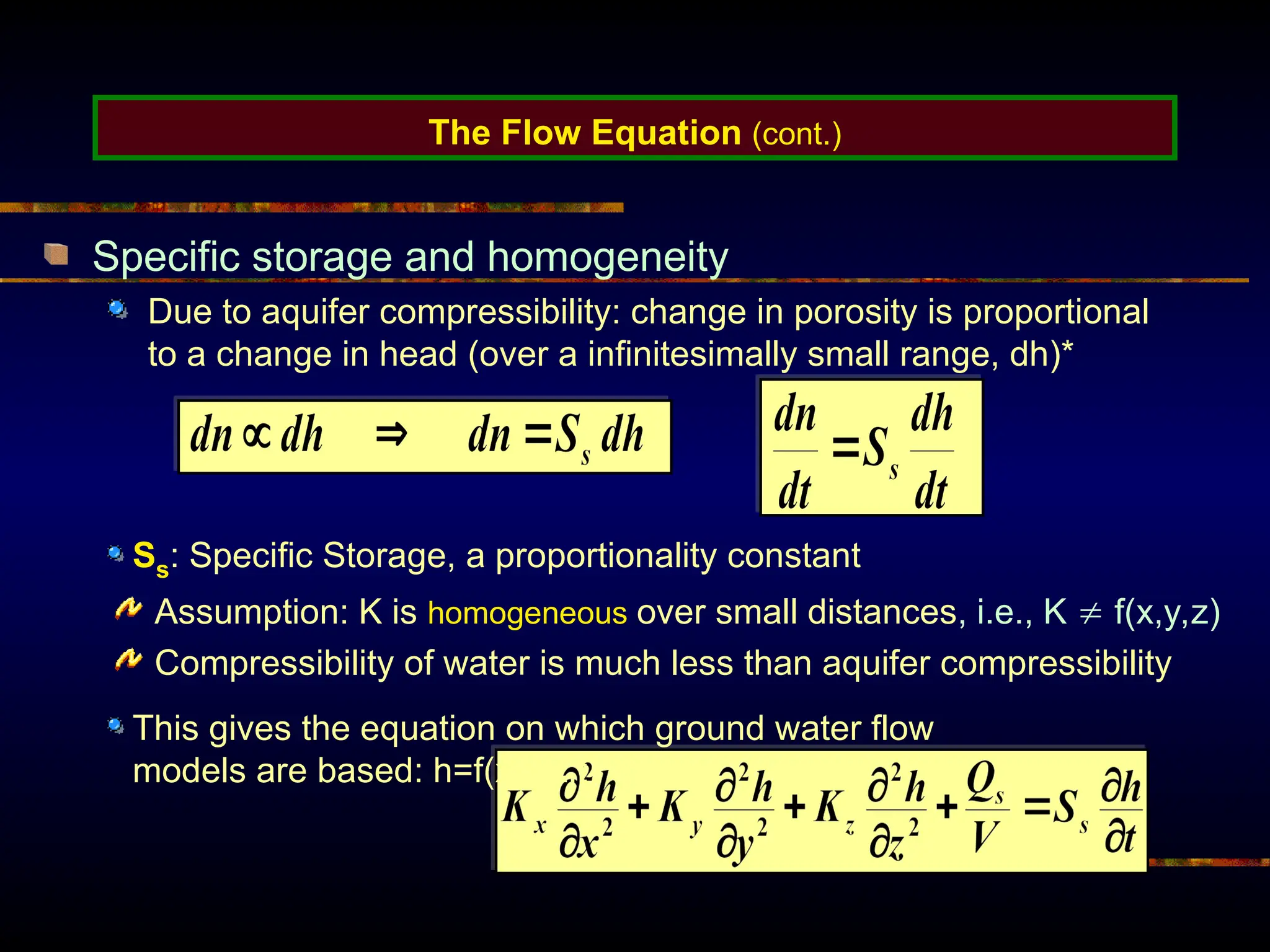

Flow Equation Simplifications

0

Our job is not yet finished, h=f(x,y,z,t)?

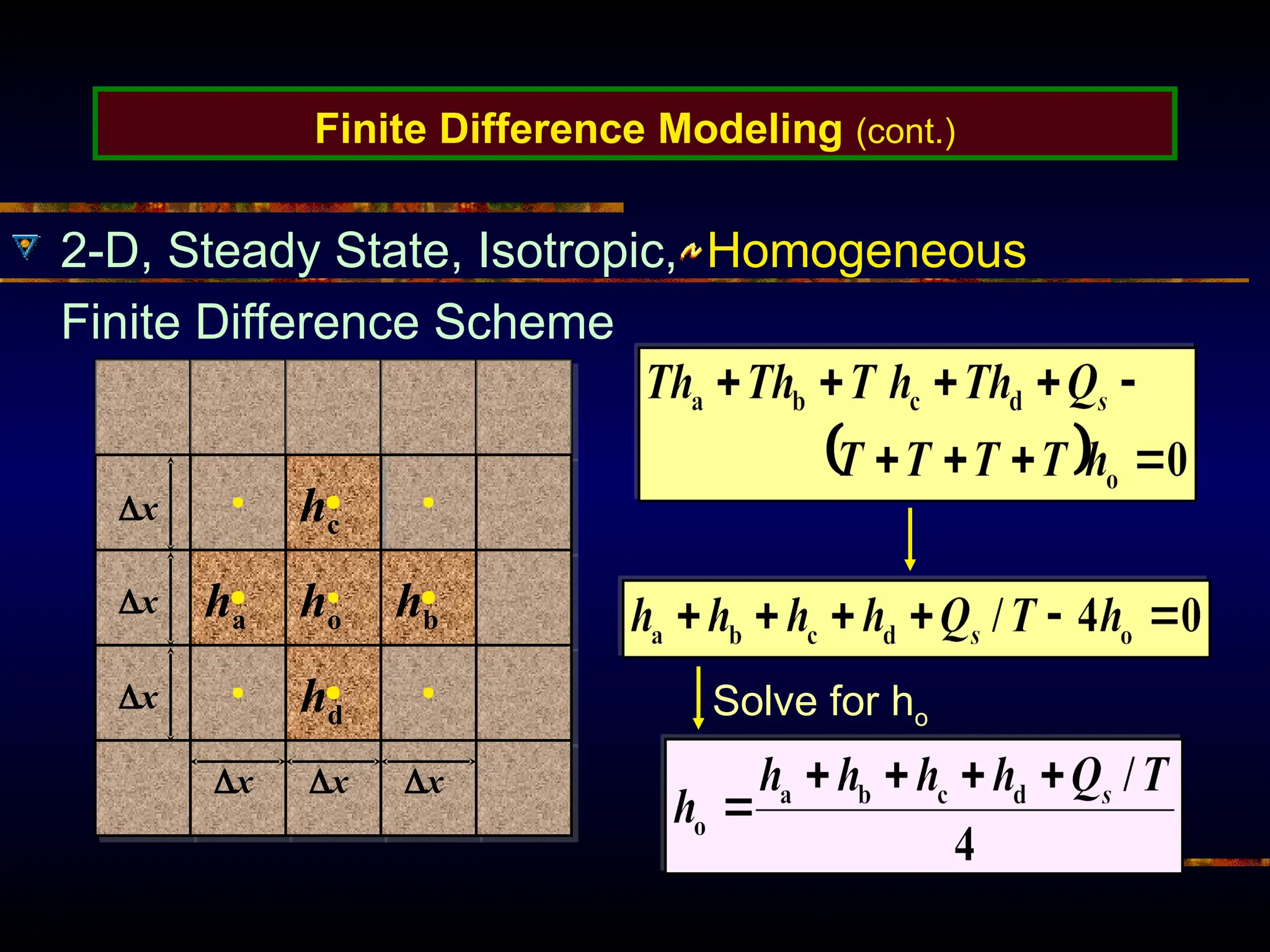

Isotropic, 2-D, steady state flow equation

(without source term), a.k.a.: The Laplace Equation

2-D, horizontally isotropic flow equation

Kx=Ky=Kh

T=Kh b units: [L2

/T], S=Ss b

Ah: horizontal area of recharge

Ss/Kh=S/T hydraulic diffusivity

Two dimensional flow equation

Horizontal flow (Dupuit assumption)

Thus: dh/dz = 0

Steady State Flow Equation

If inflow = out flow, Net inflow = 0

Change in storage = 0

0

0 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finitedifferencegwmodeling-compatibilitymode-repaired-241025144050-b05461d0/75/FiniteDifference-GW-modeling-Compatibility-Mode-Repaired-ppt-10-2048.jpg)