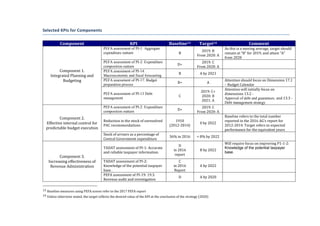

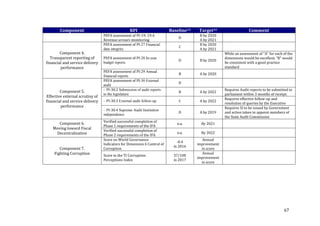

The document outlines Zambia's Public Financial Management Reform Strategy for 2019-2022. It discusses reforms in six key areas: 1) Integrated planning and budgeting, 2) Effective internal control for budget execution, 3) Increasing revenue mobilization, 4) Transparent reporting of financial and service delivery performance, 5) Effective external scrutiny of performance, and 6) Moving toward fiscal decentralization. For each area, it discusses the ideal state, current challenges, and strategic reform priorities. The strategy was developed through stakeholder consultations to ensure government ownership of reforms. While the previous reform strategy saw mixed success, achievements like rolling out an integrated financial management system provide a foundation to build on.