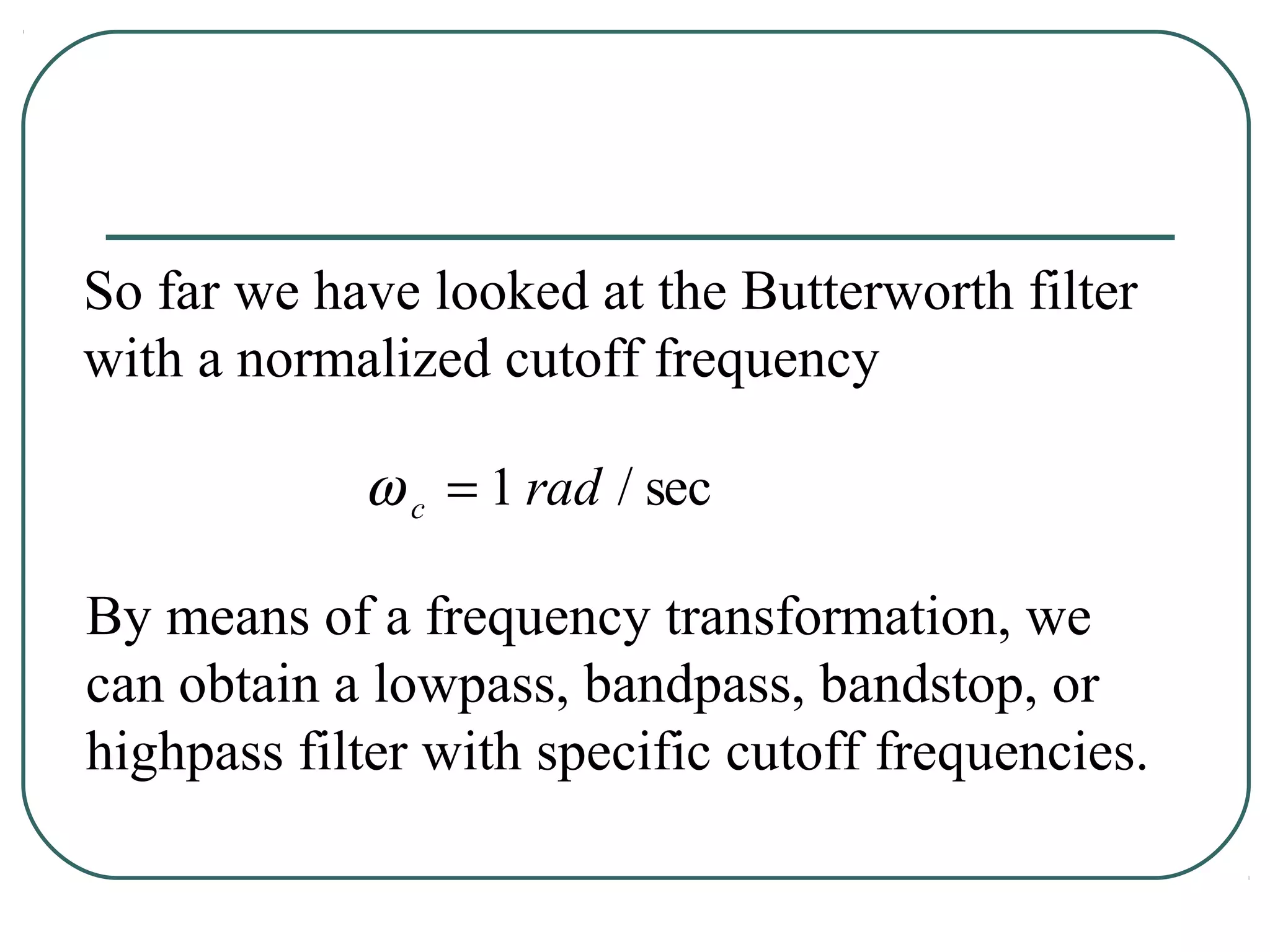

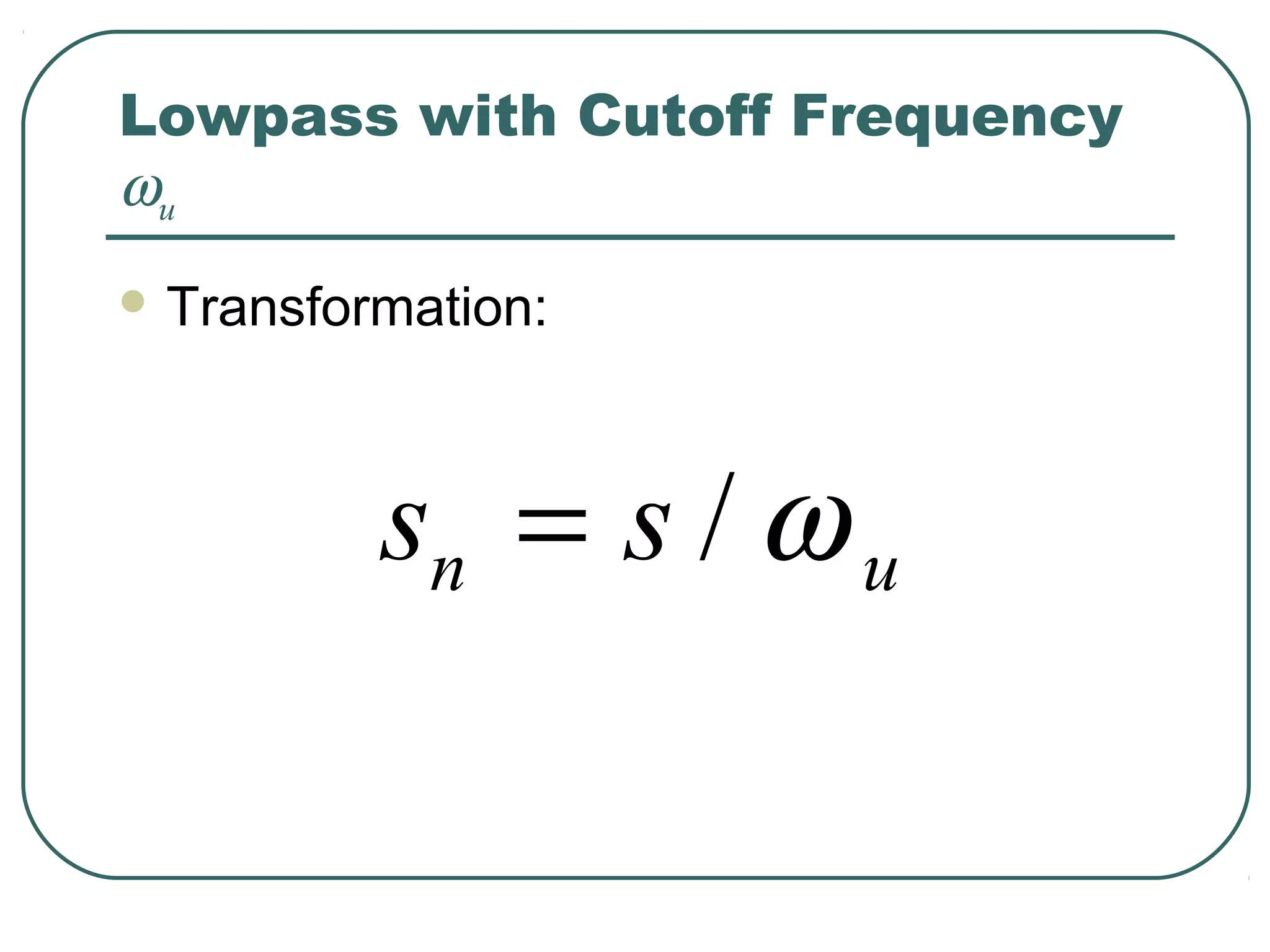

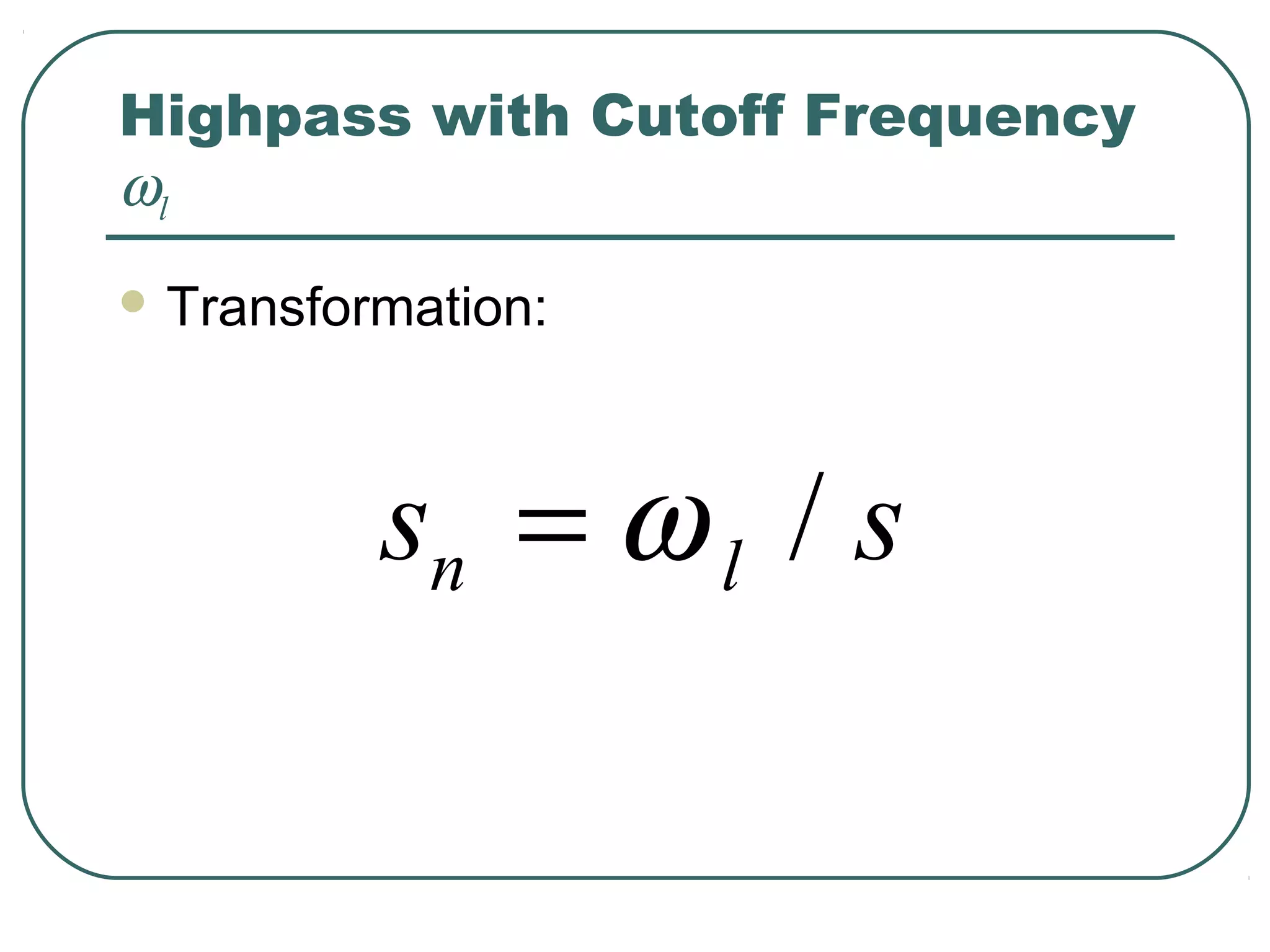

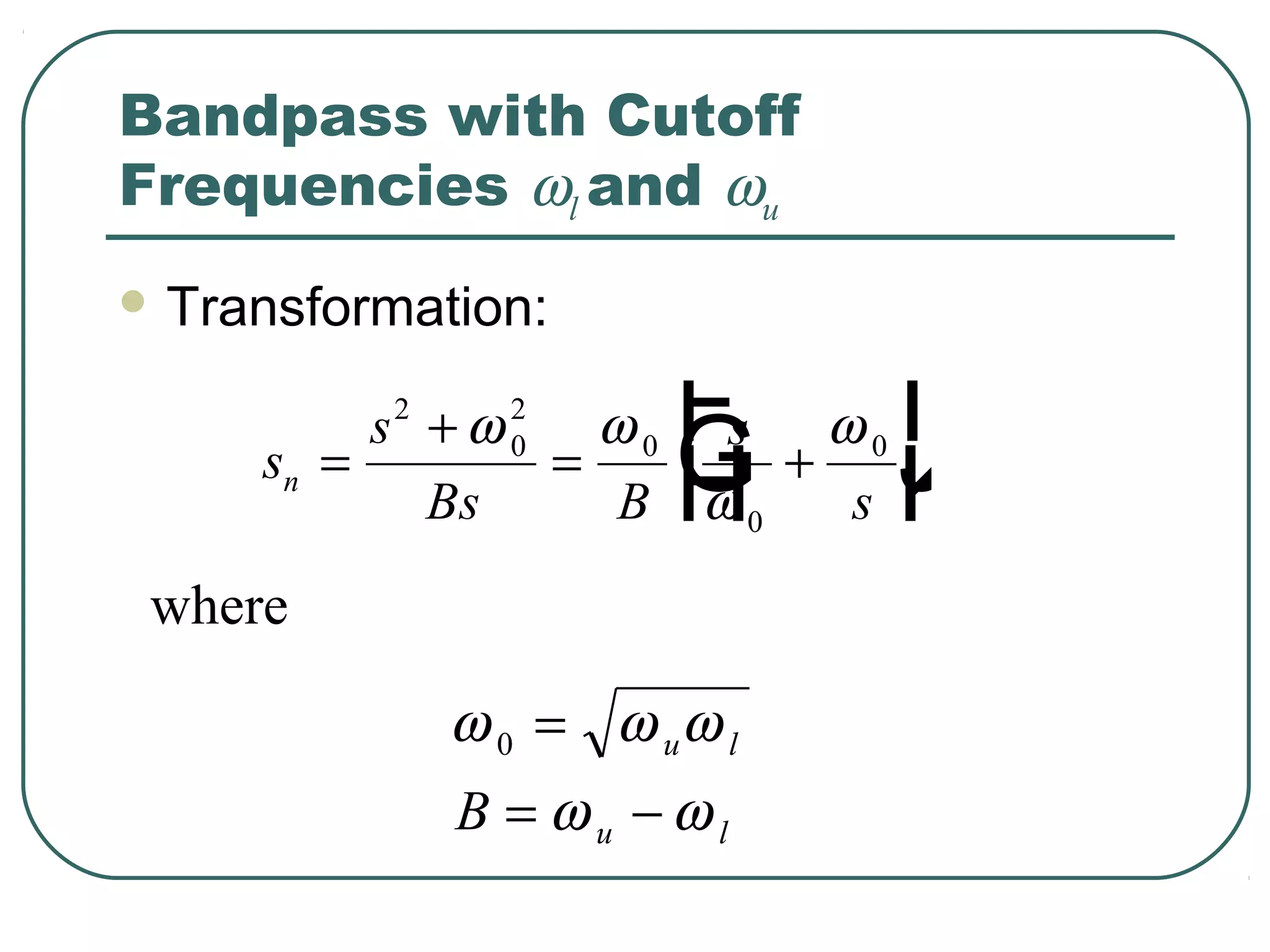

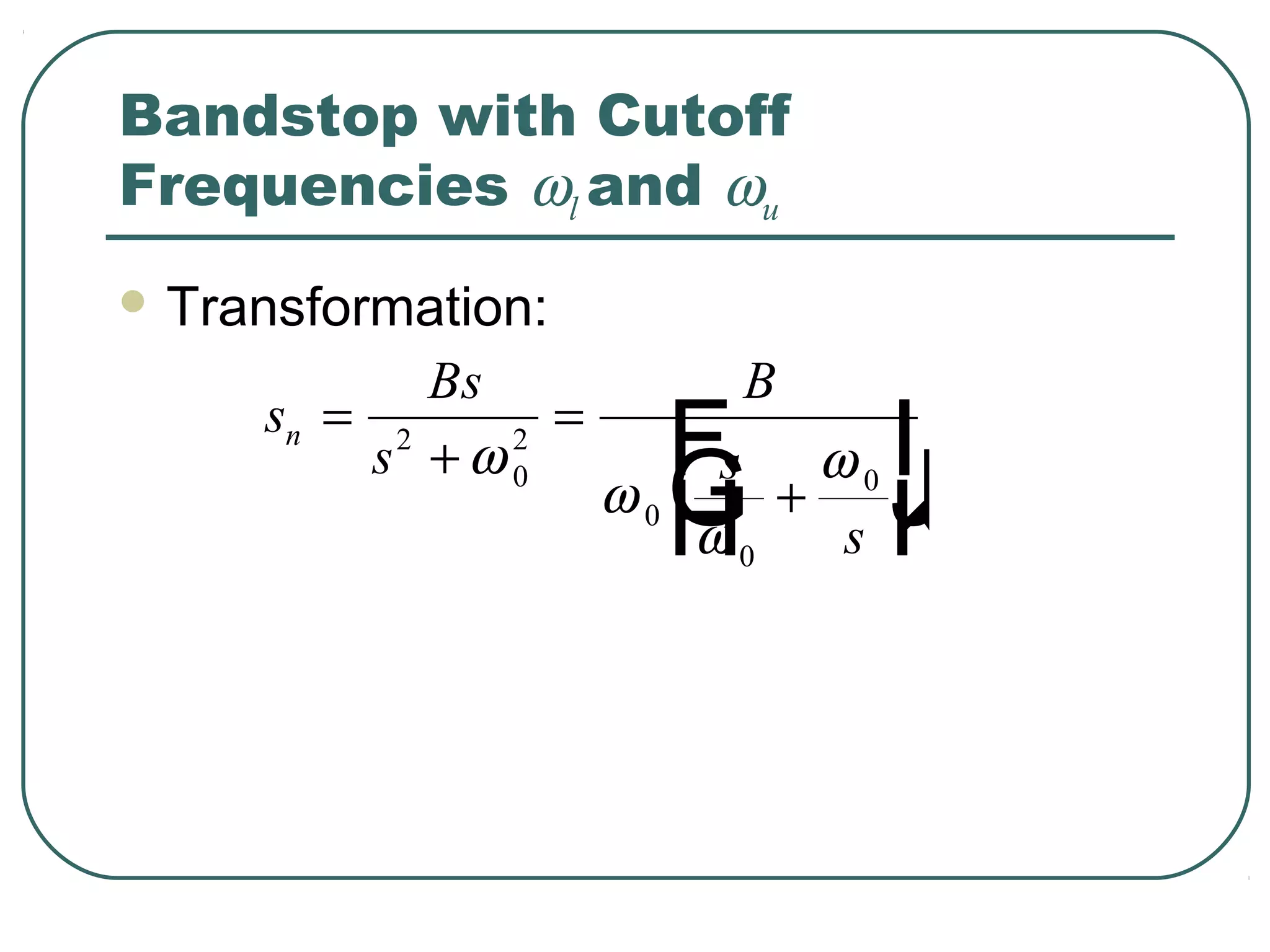

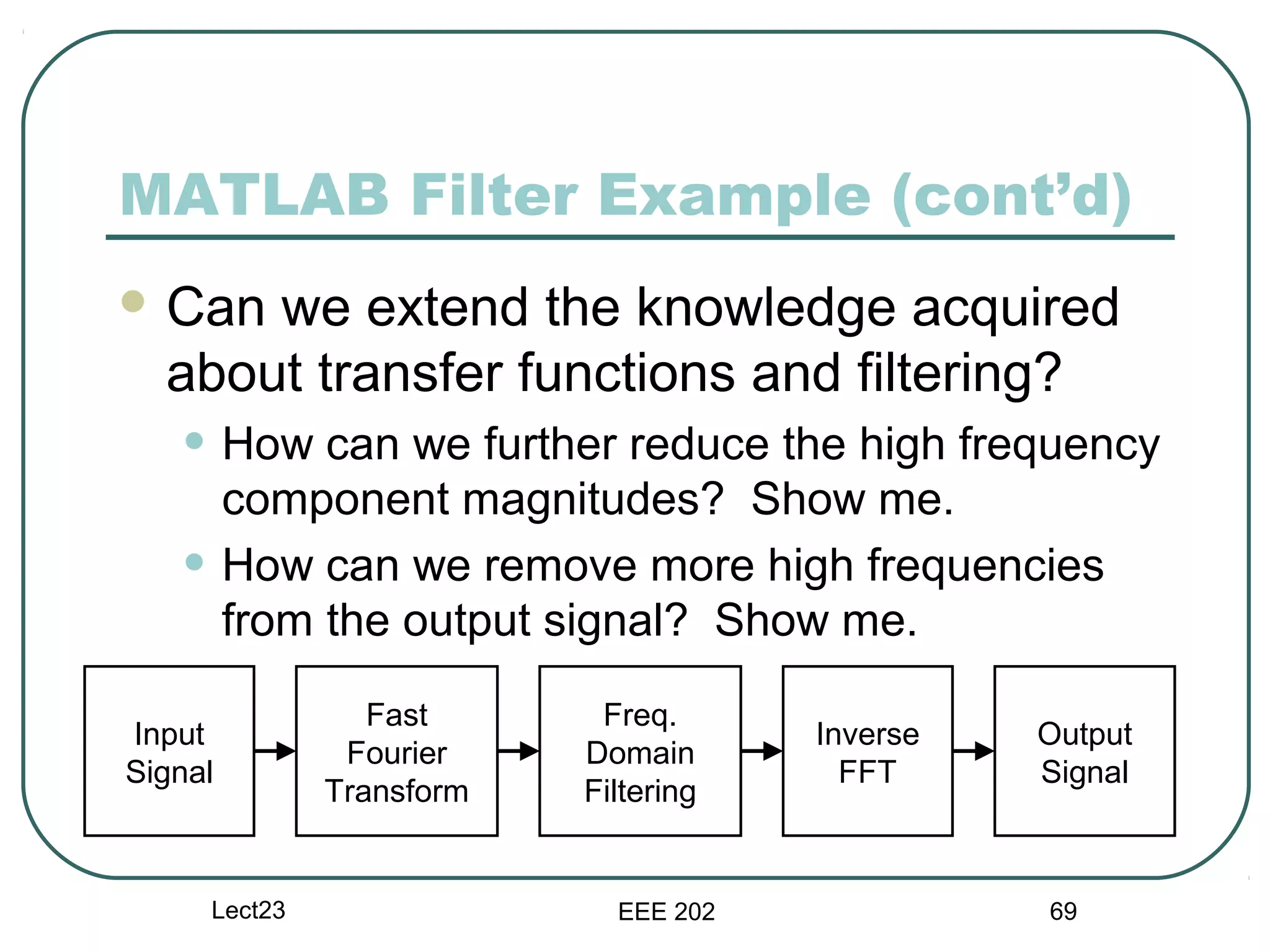

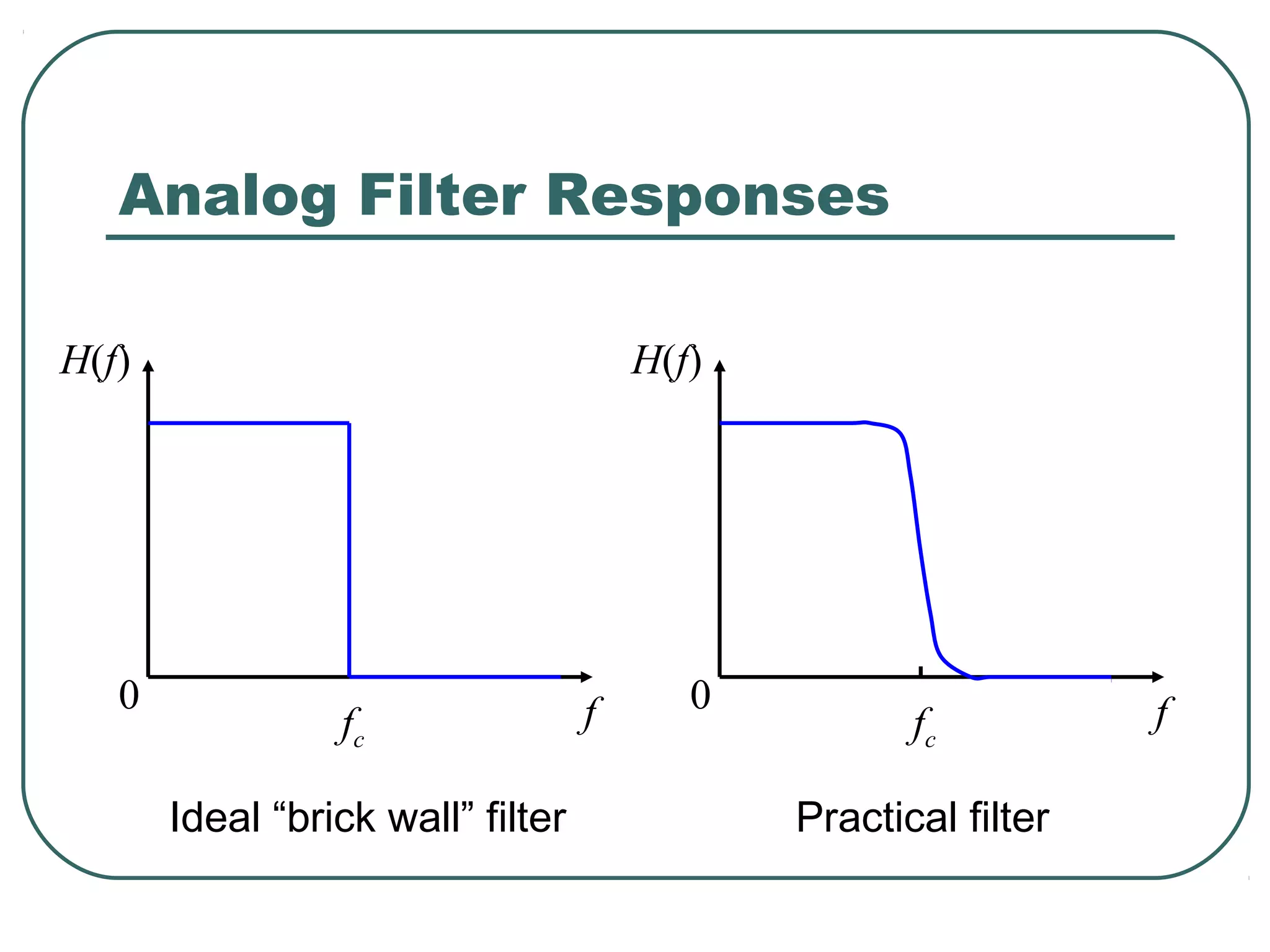

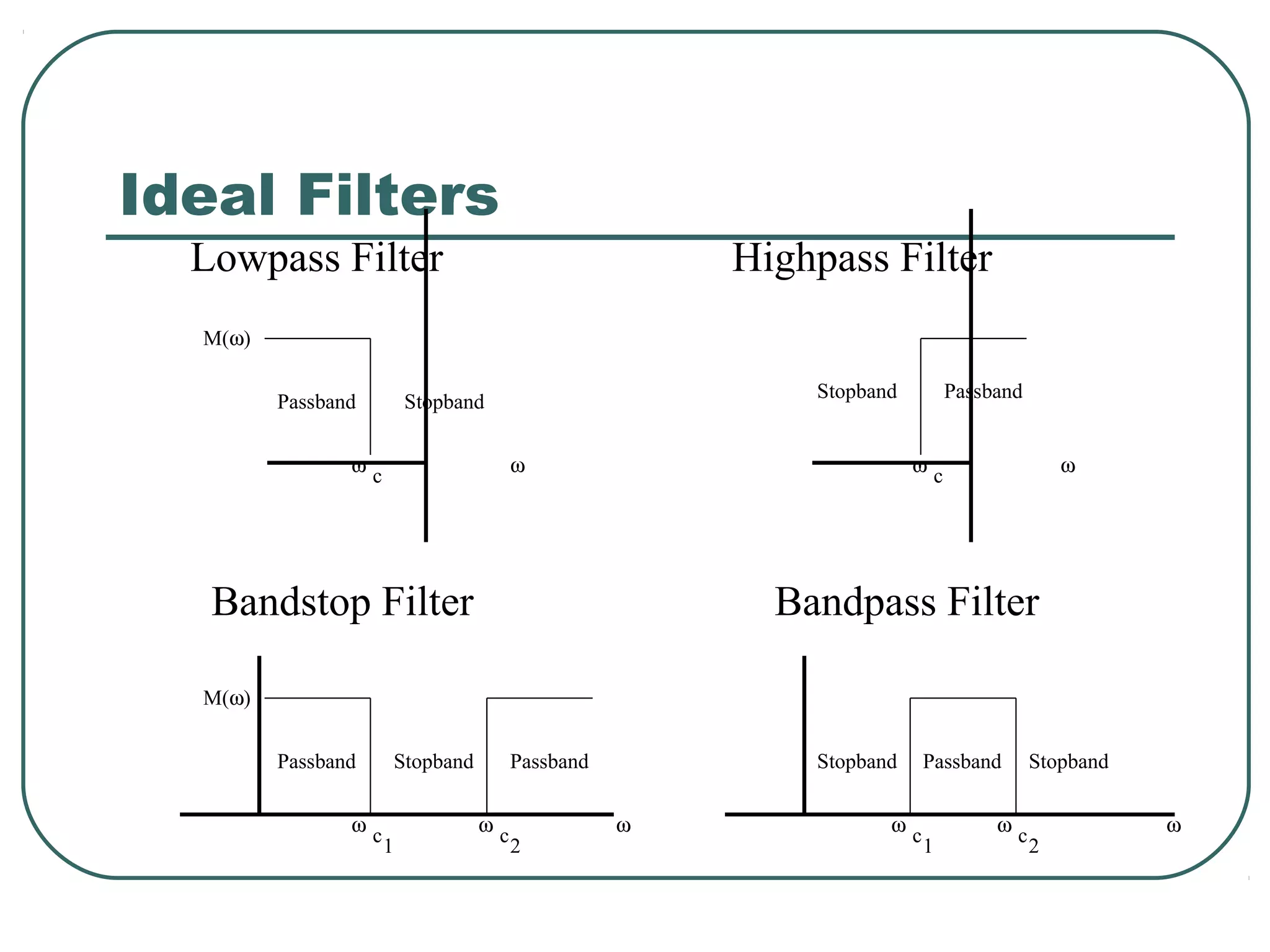

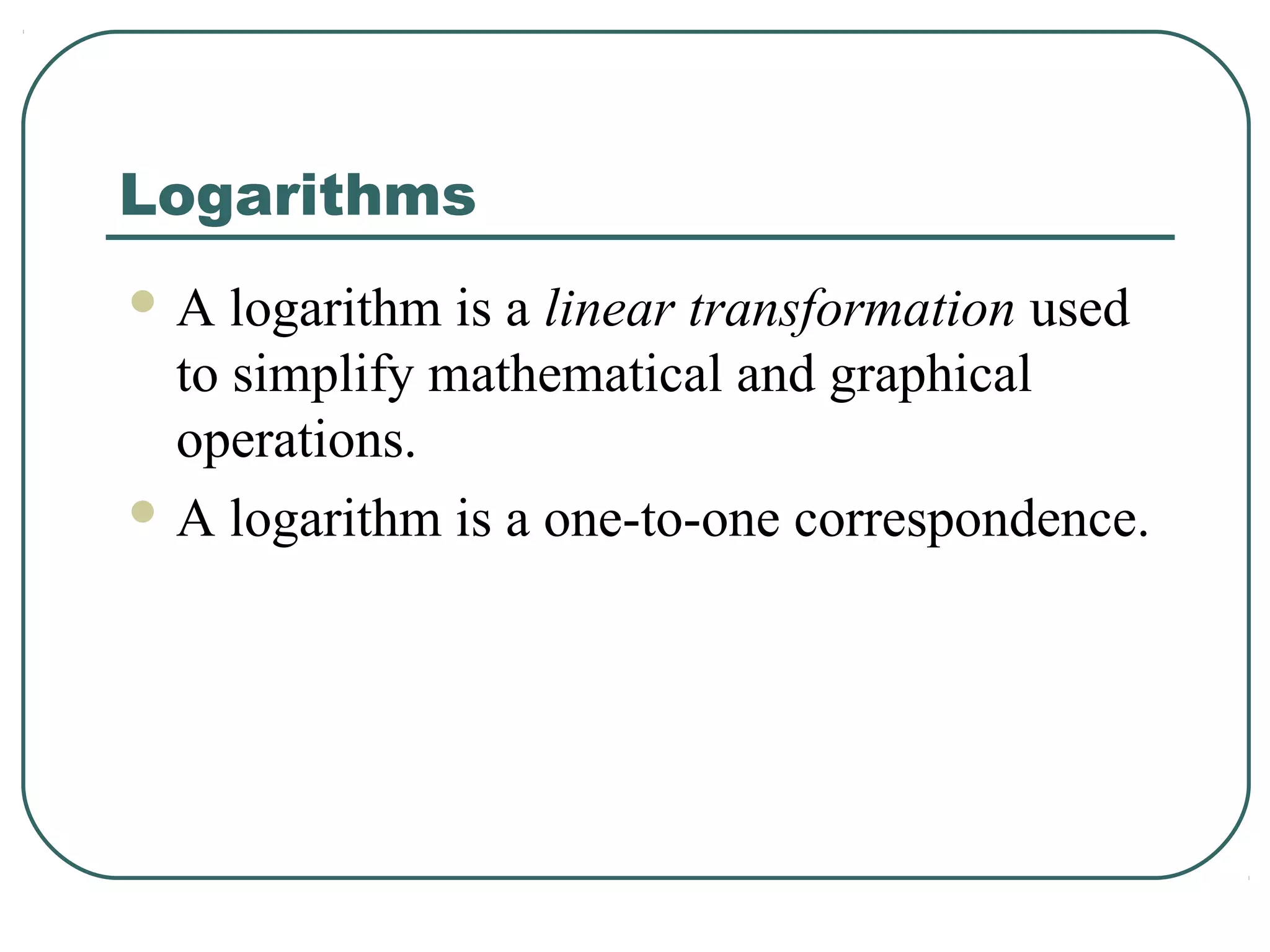

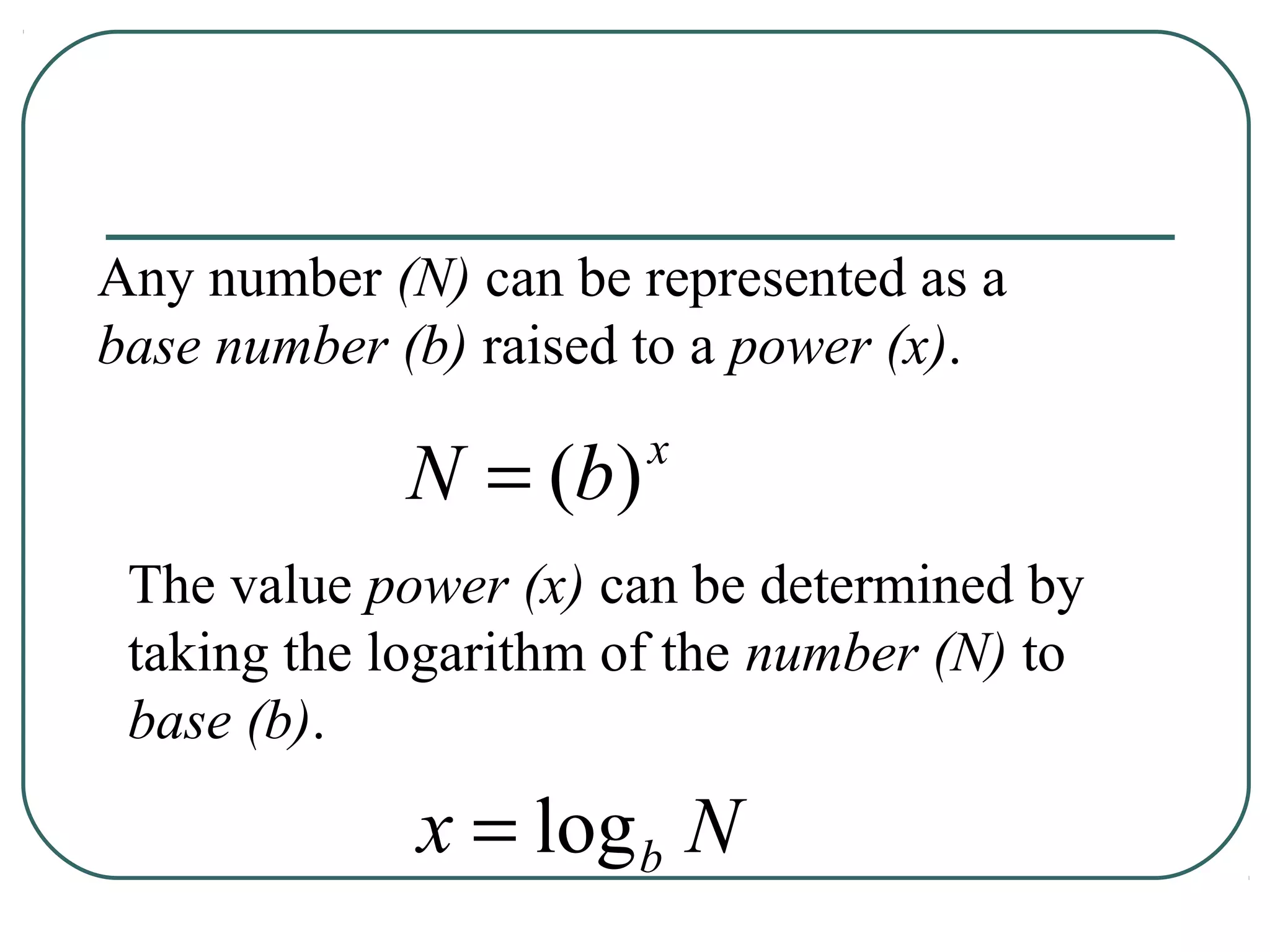

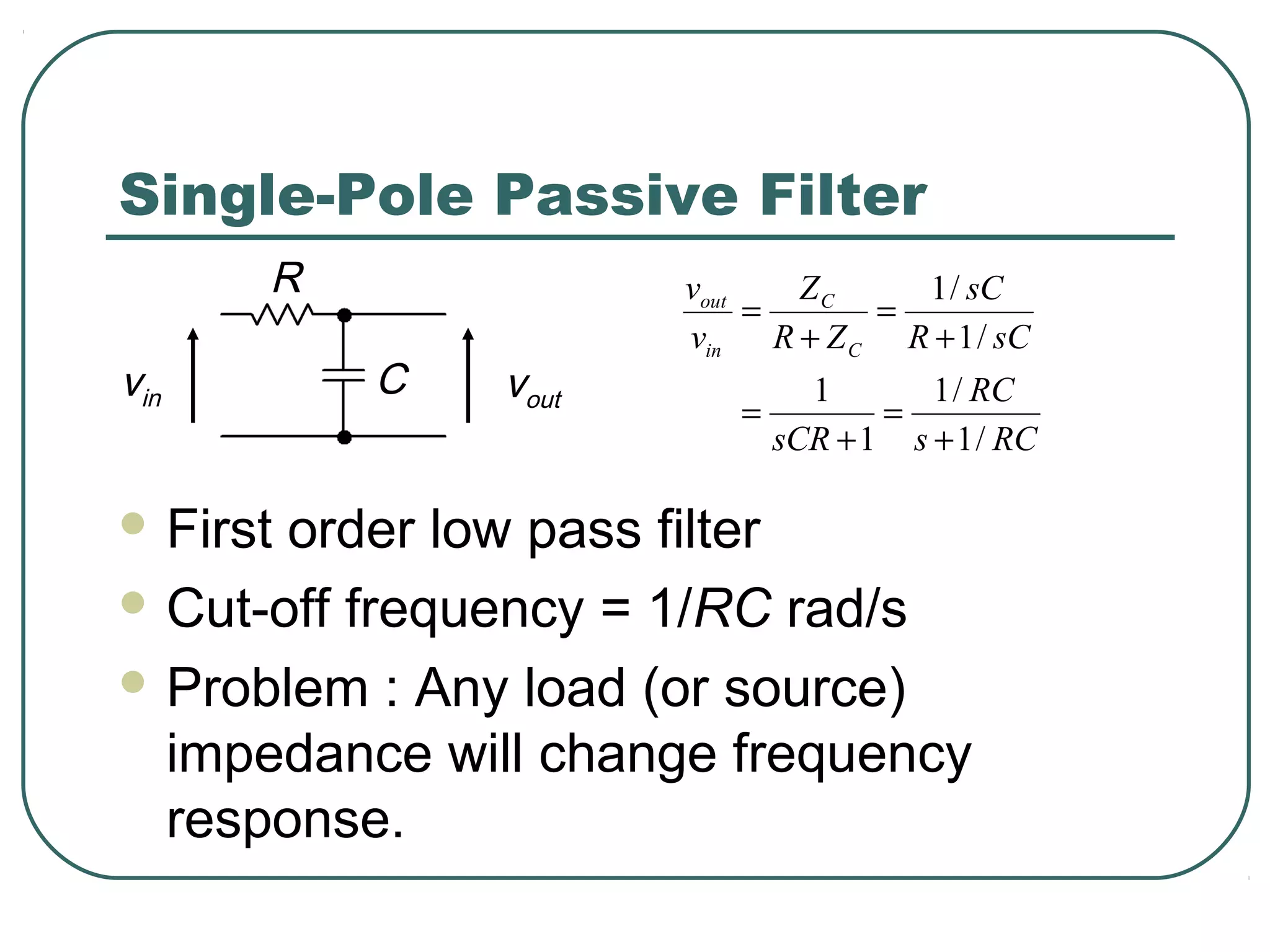

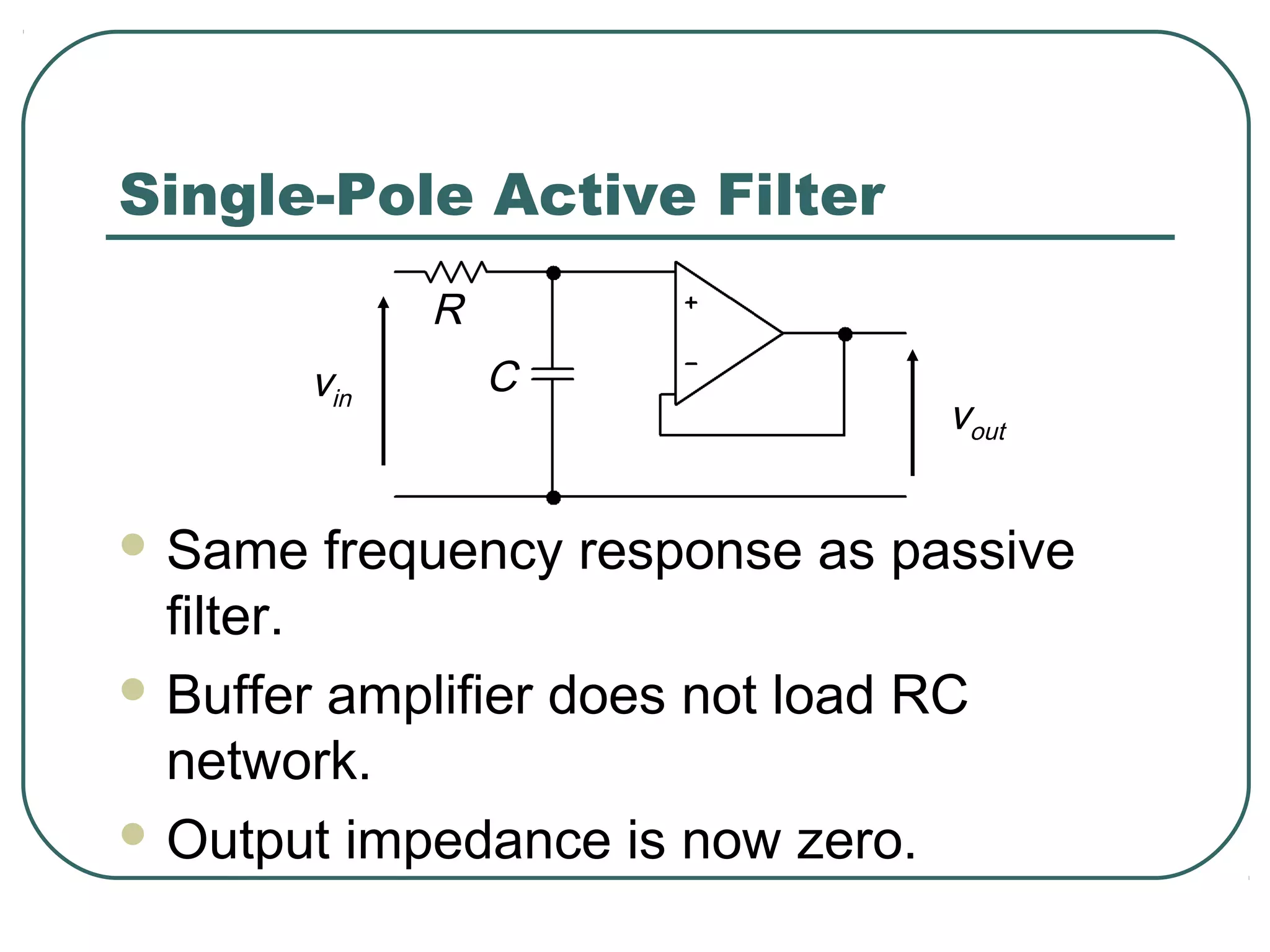

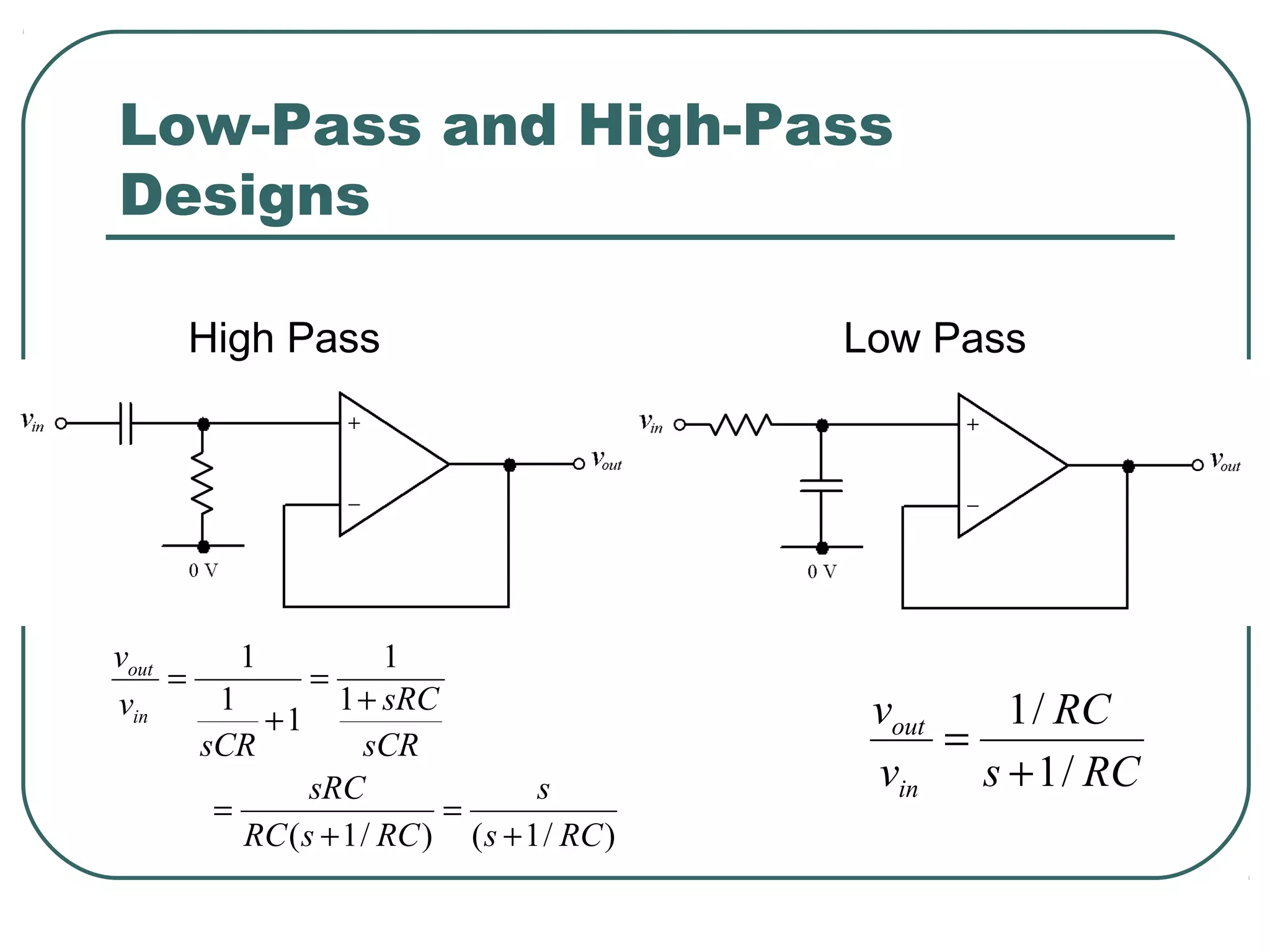

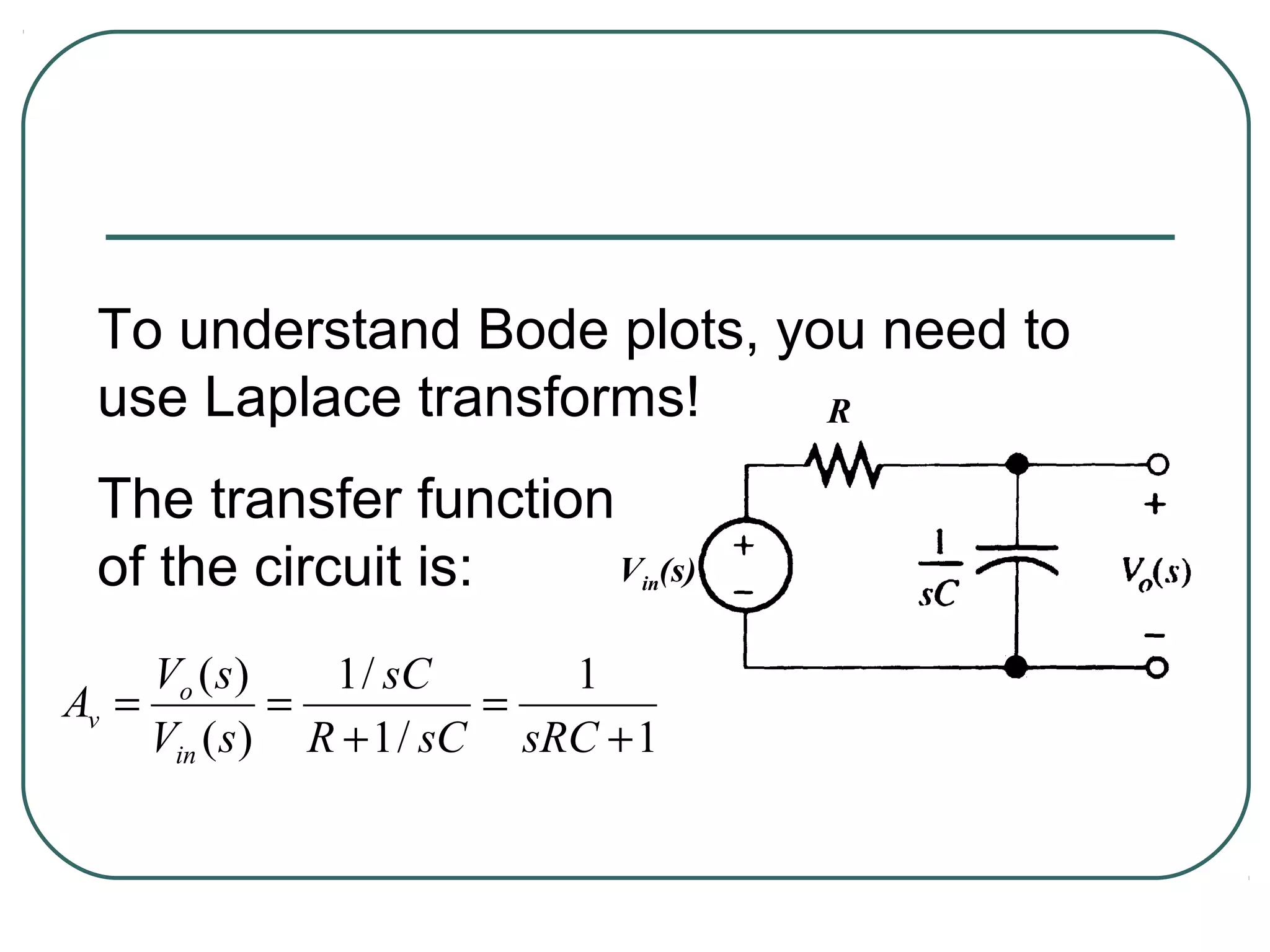

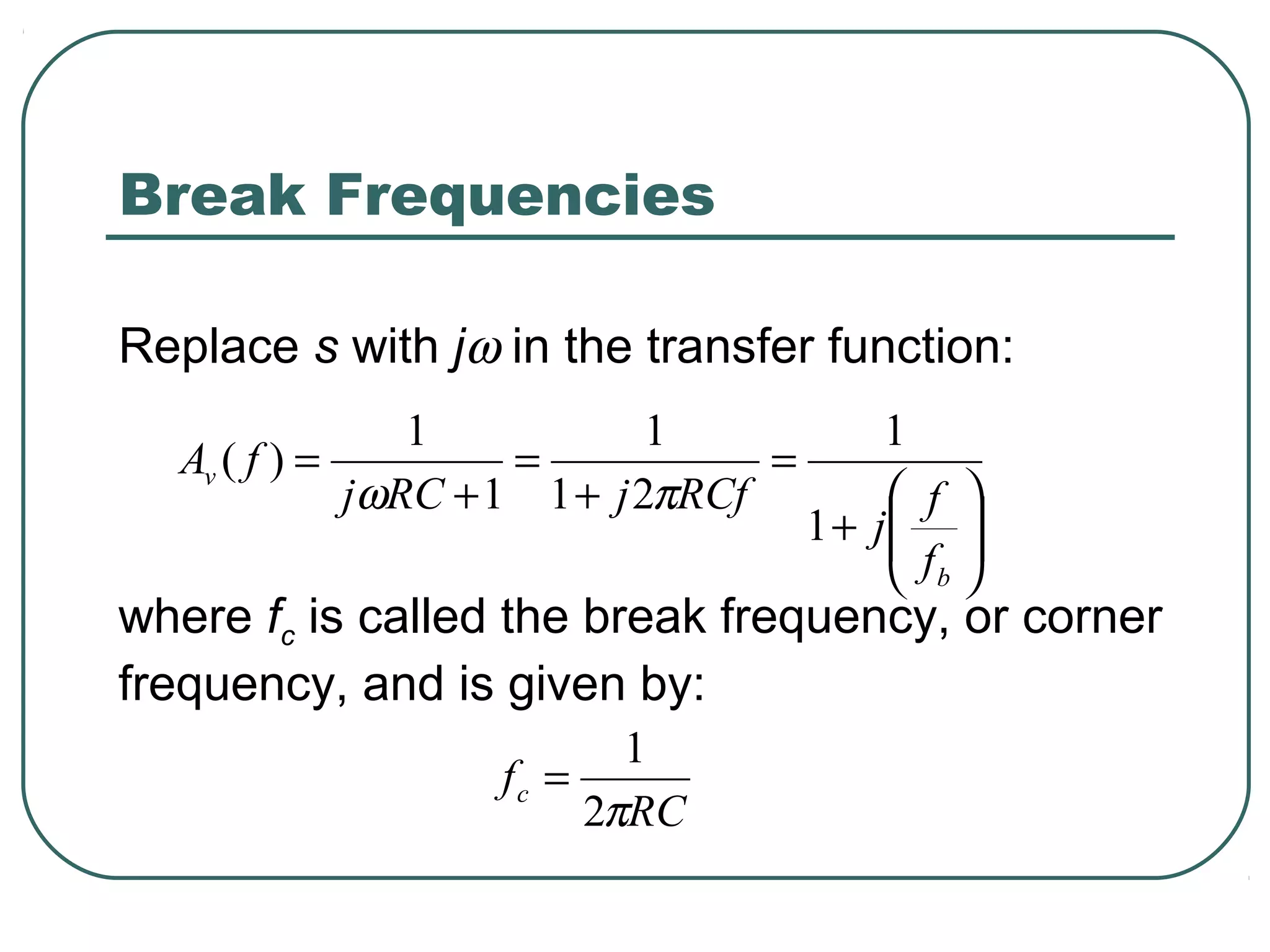

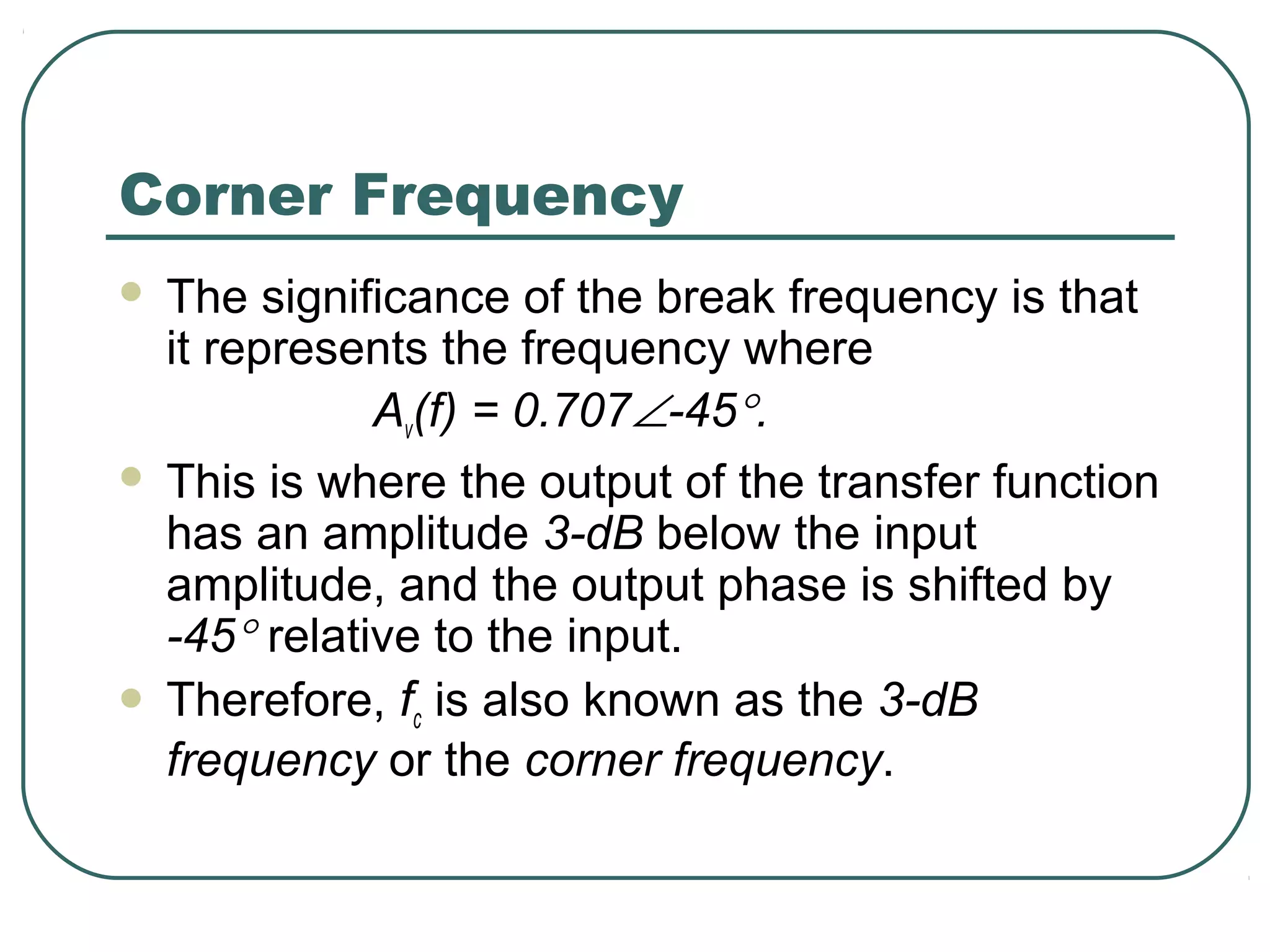

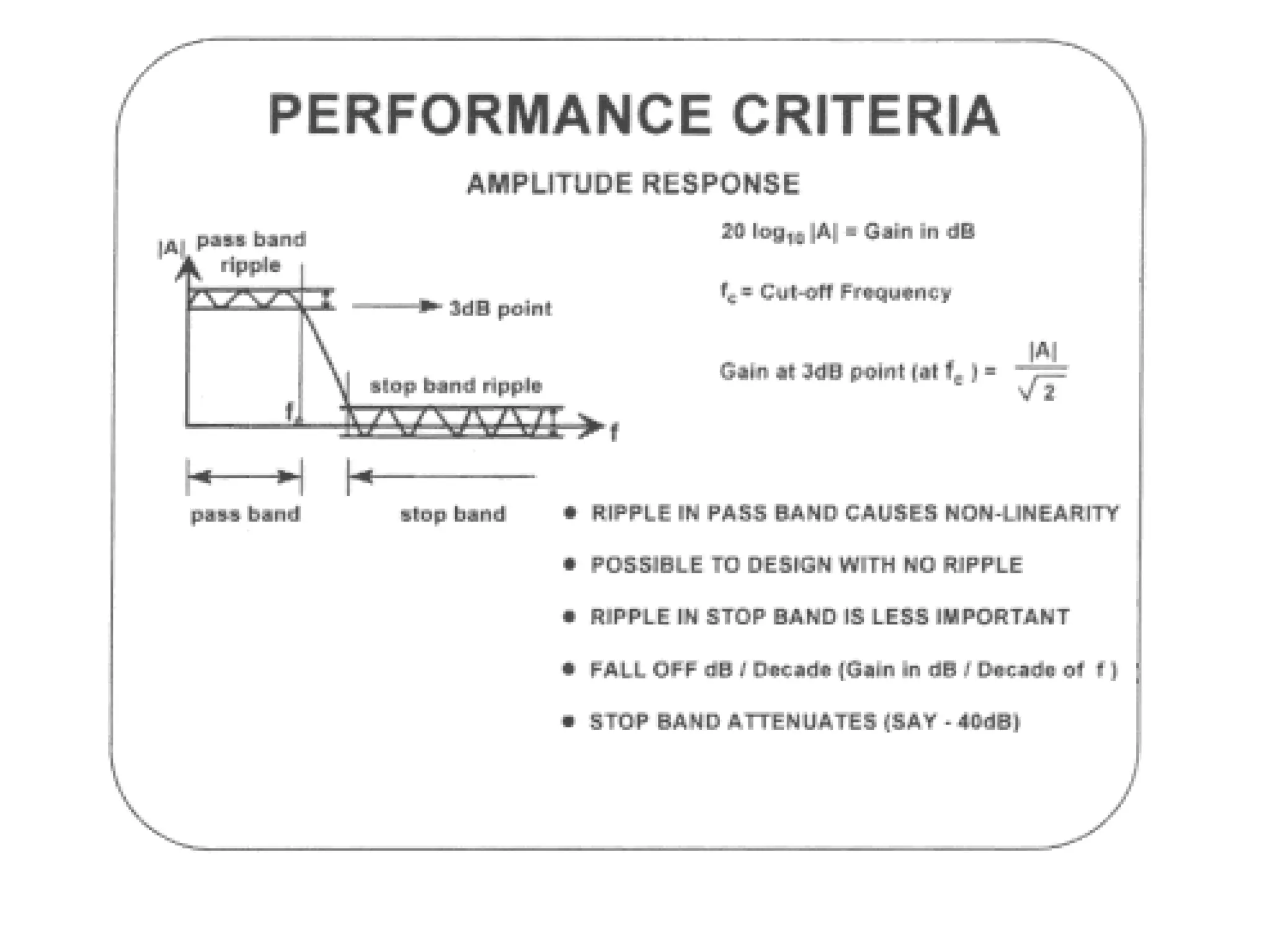

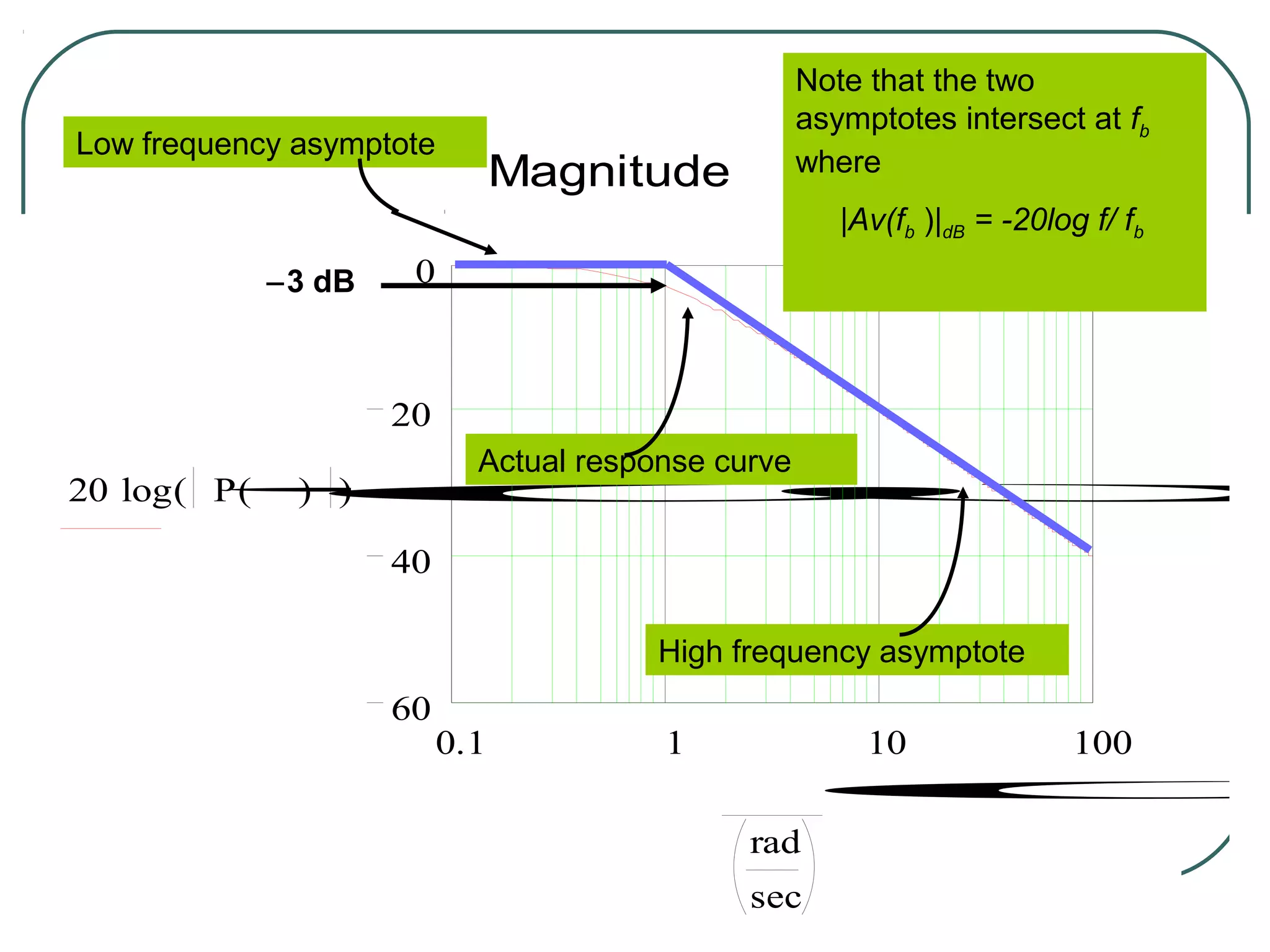

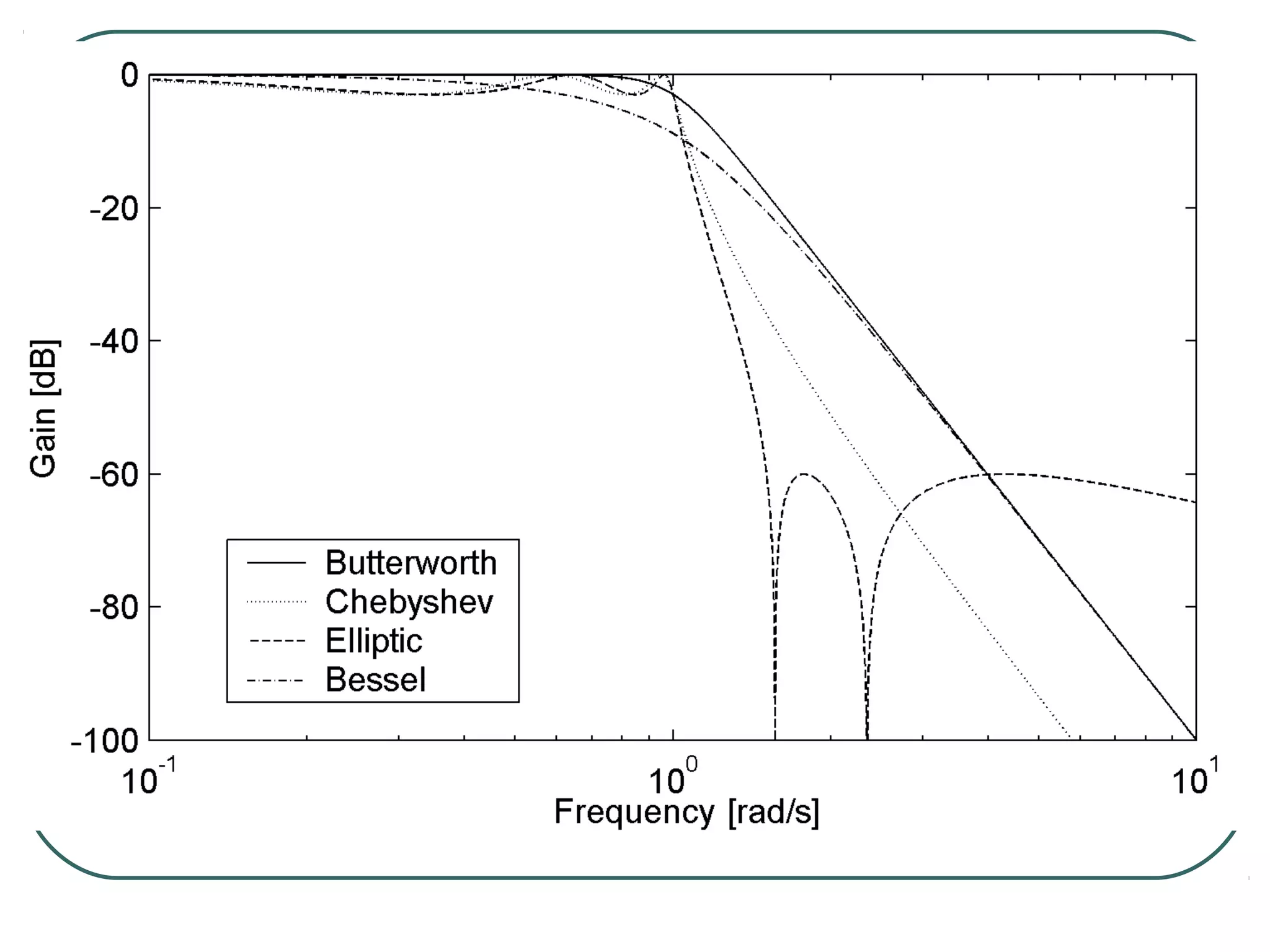

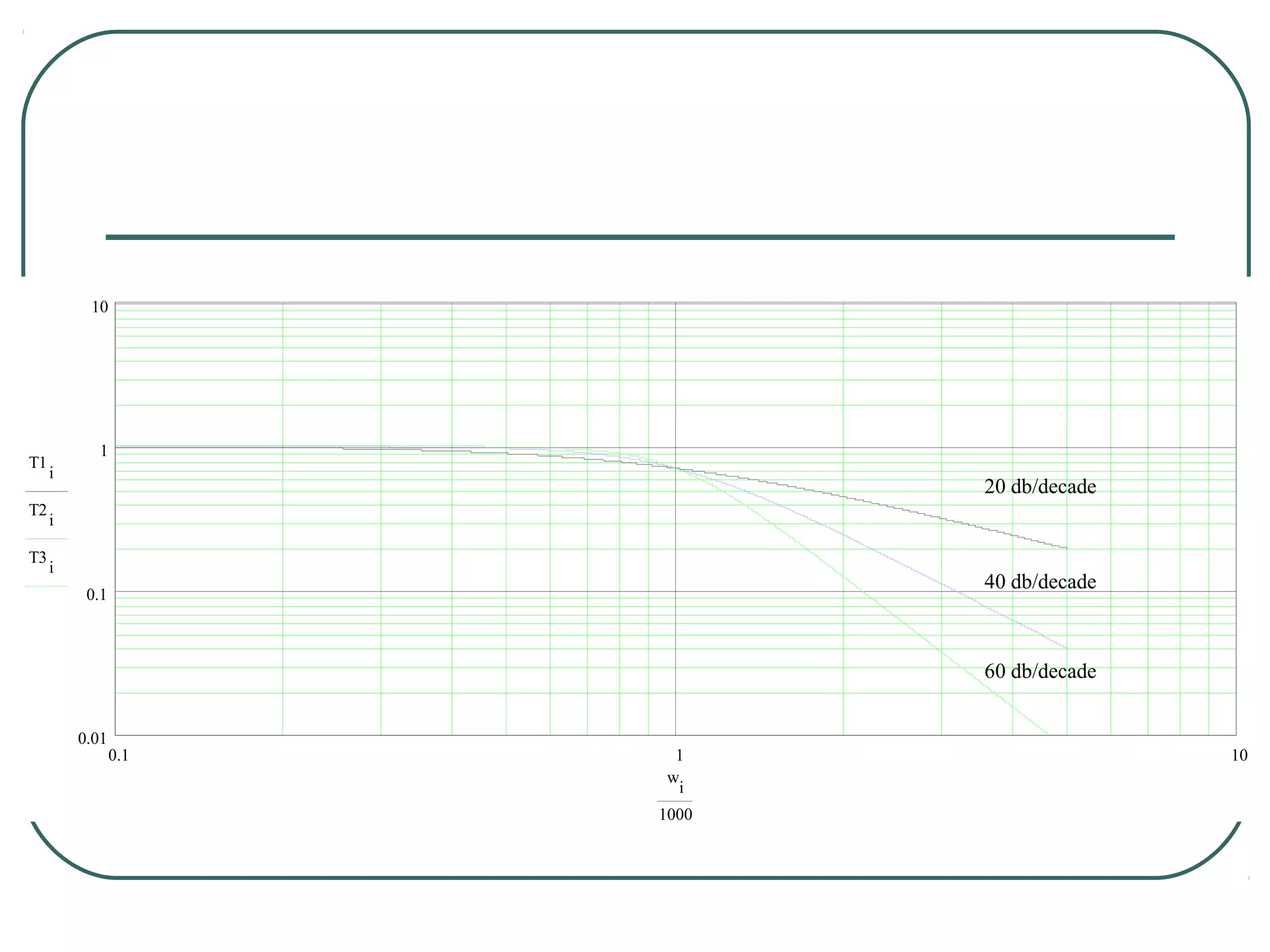

The document discusses different types of filters and their frequency responses. It describes that filters can be either analog and process continuous signals, or digital and process discrete signals. There are four main types of filters: lowpass, highpass, bandstop, and bandpass. The frequency response of these filters can be modeled using concepts like poles, zeros, break/corner frequencies, and Bode plots. Bode plots use logarithmic scales to show how the magnitude and phase of a filter's transfer function change over frequency.

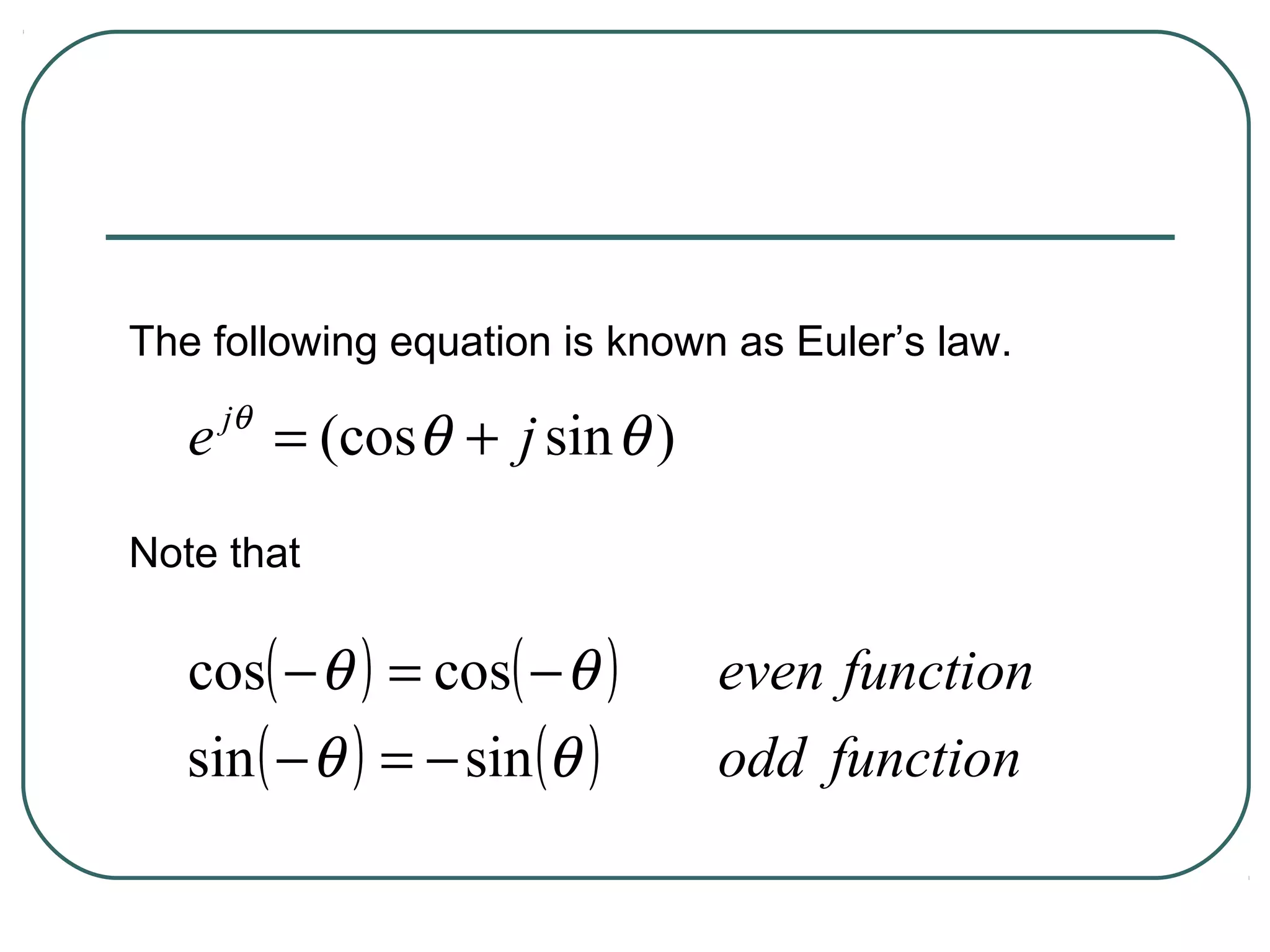

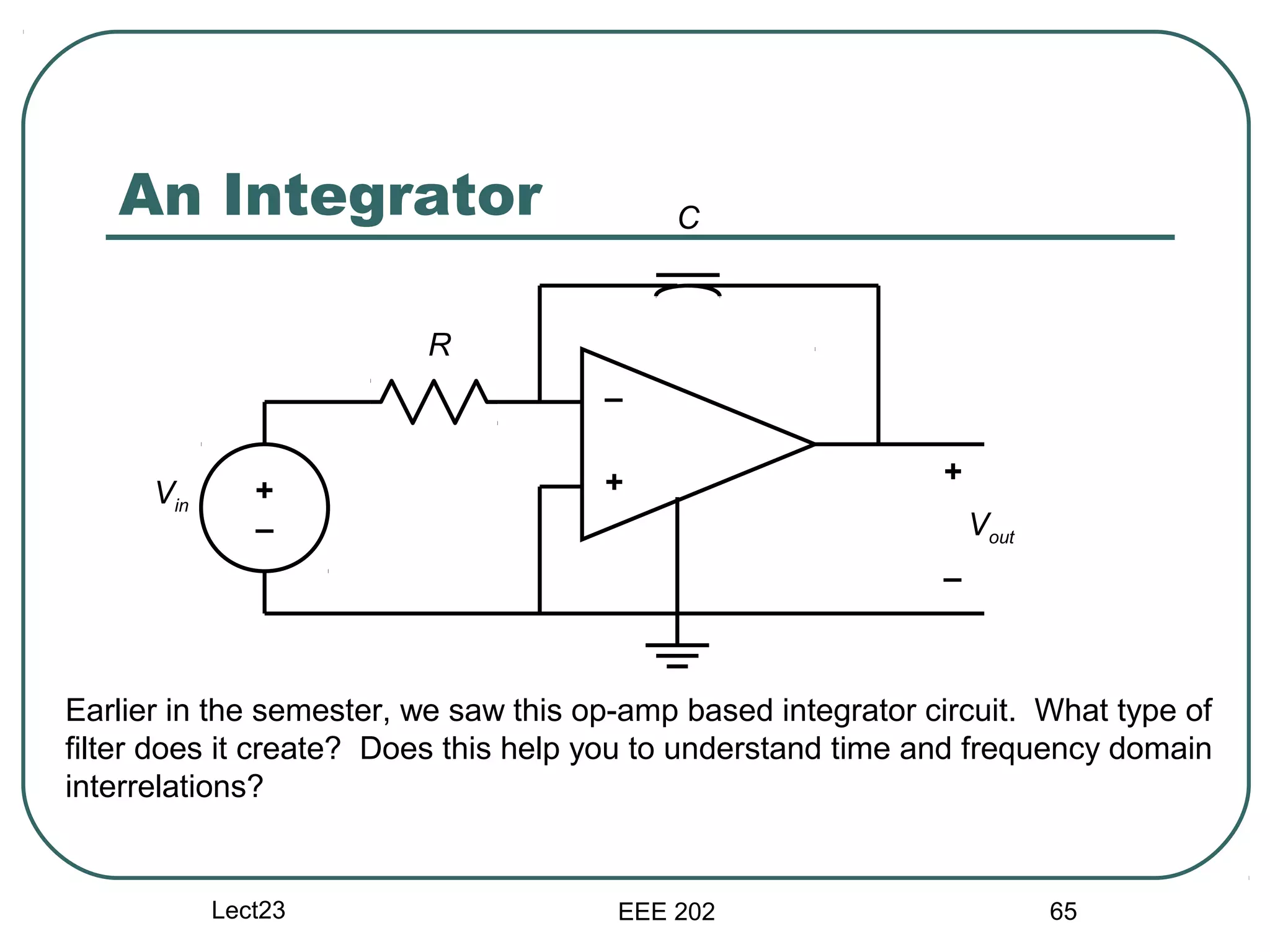

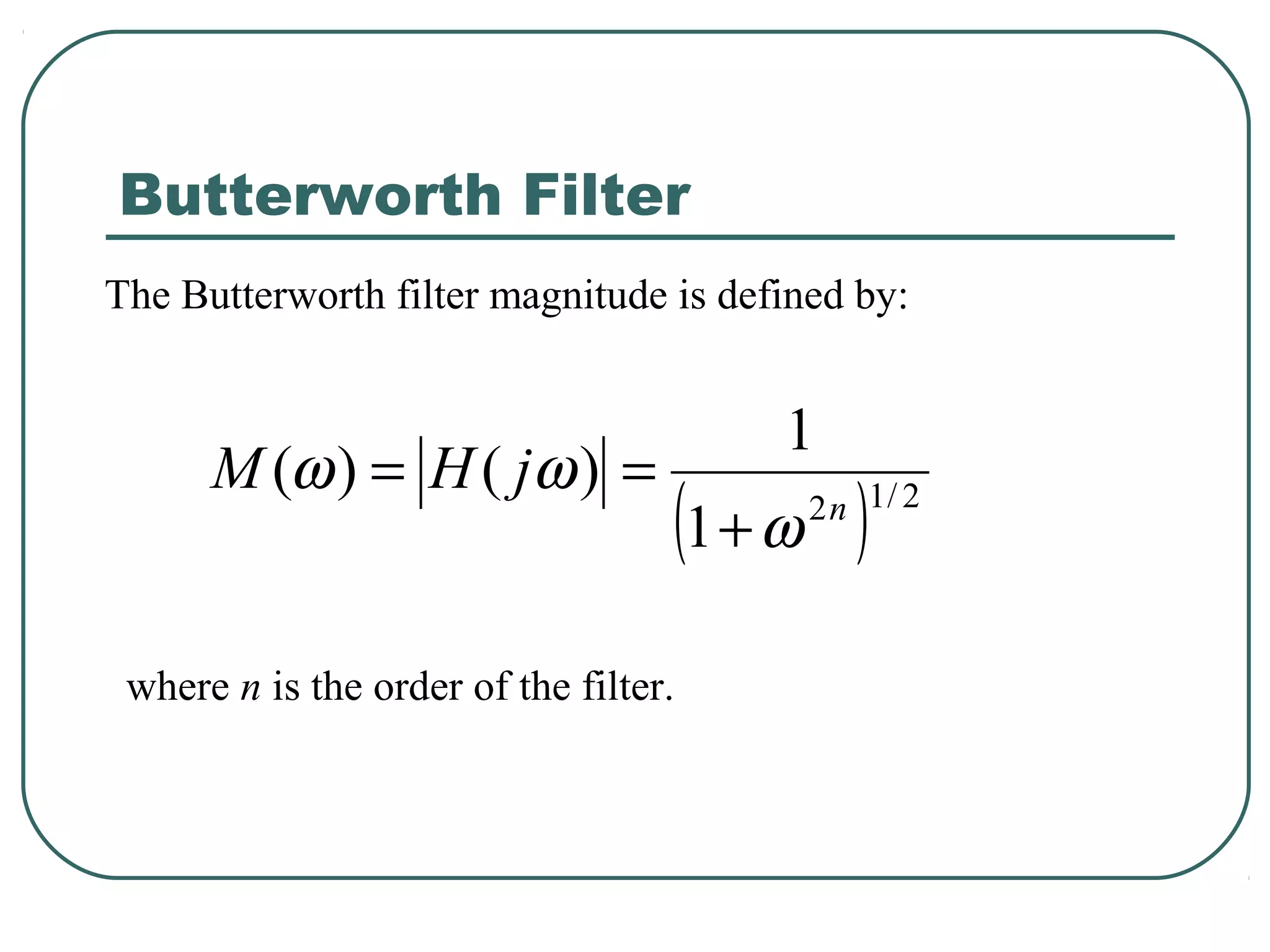

![ Consider the magnitude of the transfer

function: 1

Av ( f ) =

1 + ( f / fb )

2

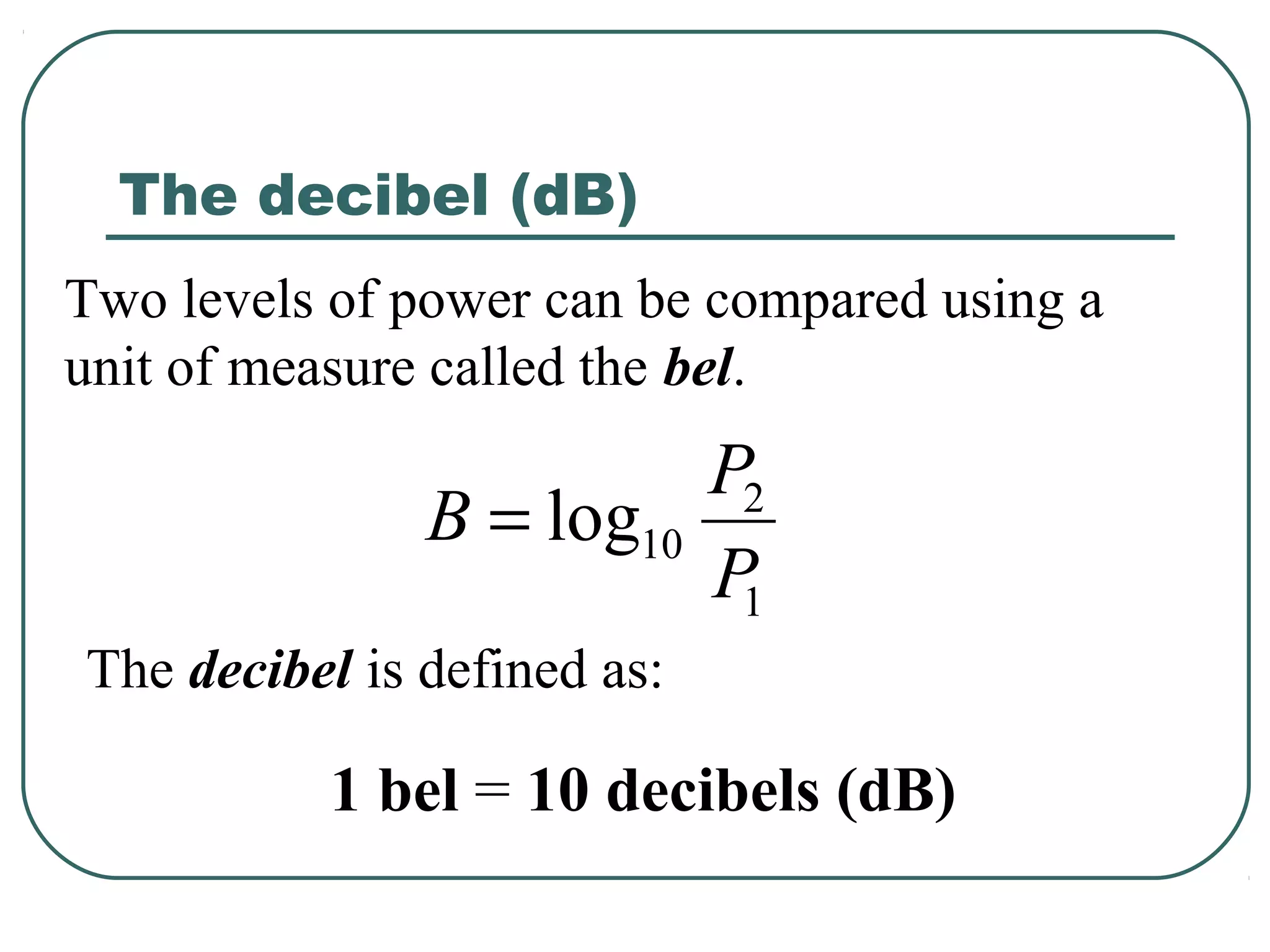

Expressed in dB, the expression is

Av ( f ) dB = 20 log 1 − 20 log 1 + ( f / f b )

2

[

= −20 log 1 + ( f / f b ) = −10 log 1 + ( f / f b )

2 2

]

= −20 log( f / f b )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/filter-dengan-op-amp-120911070757-phpapp01/75/Filter-dengan-op-amp-27-2048.jpg)

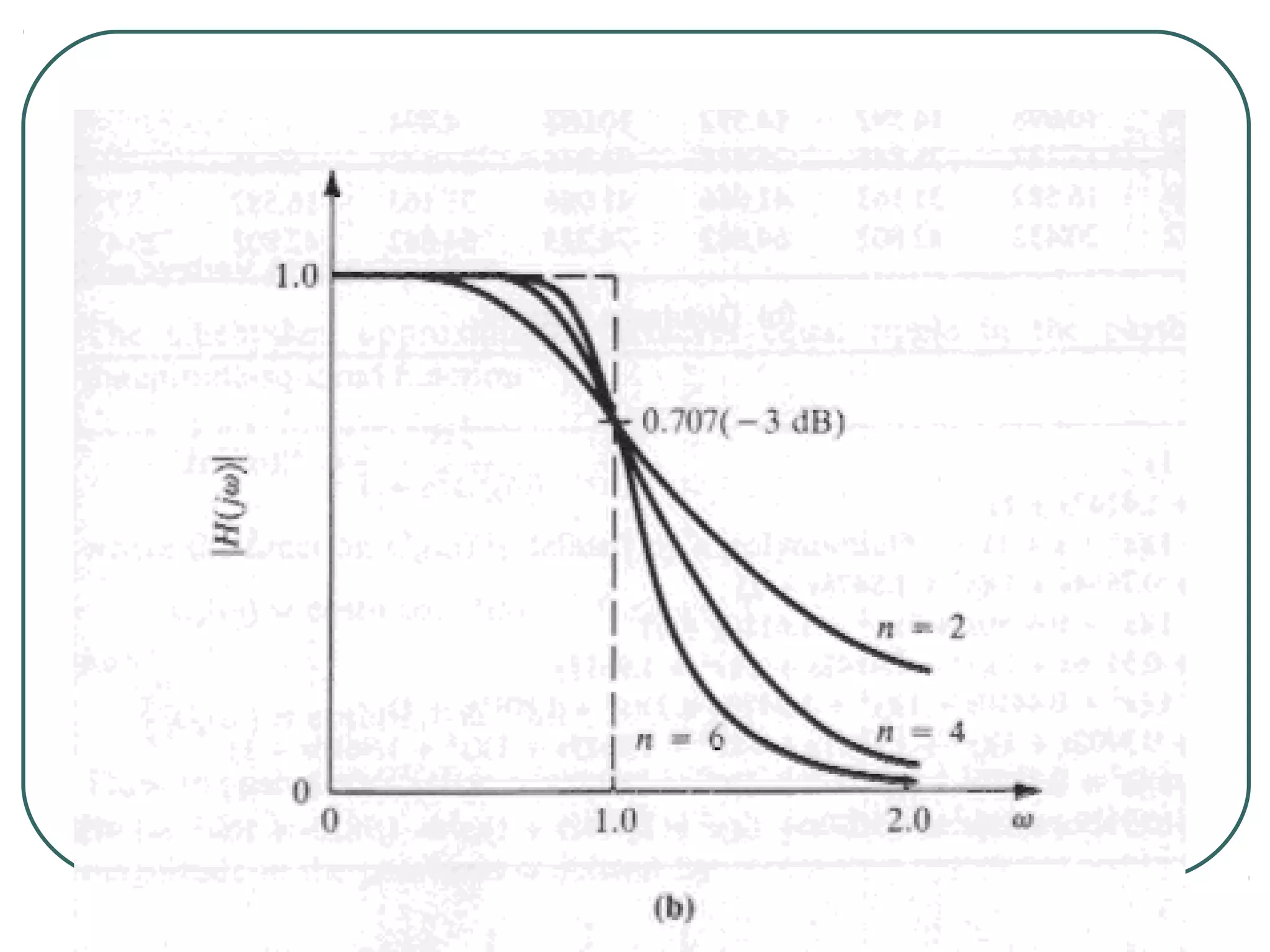

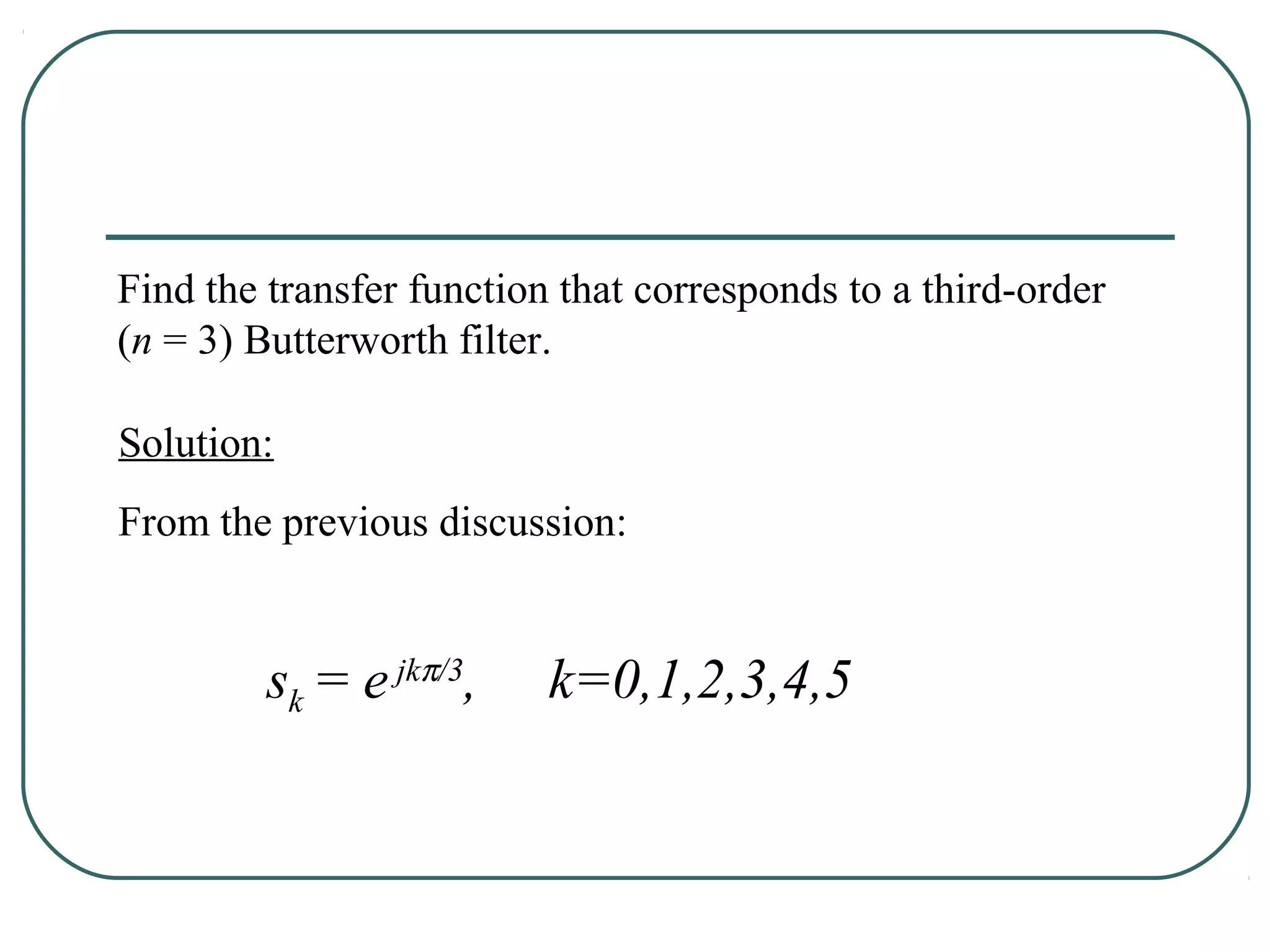

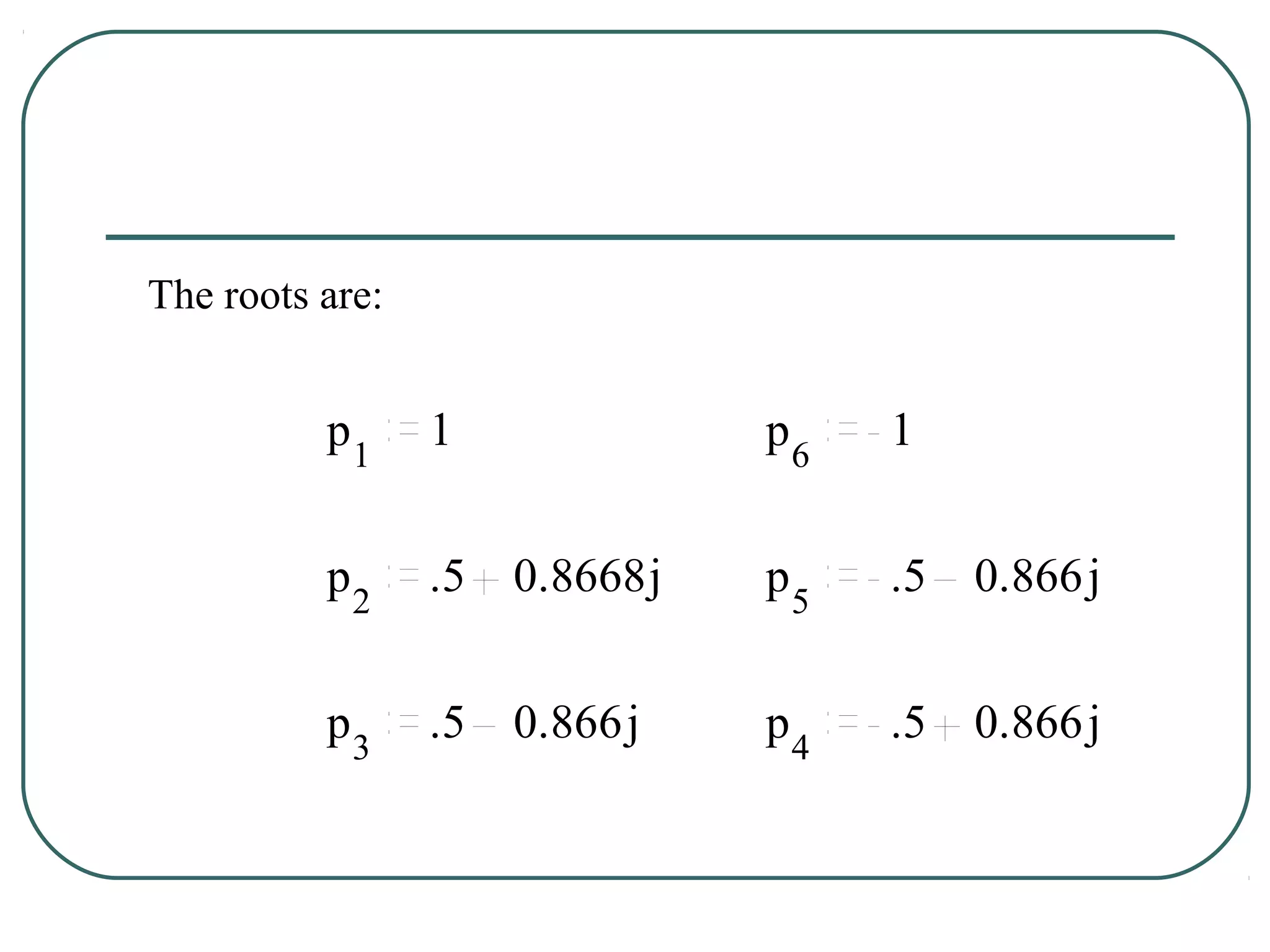

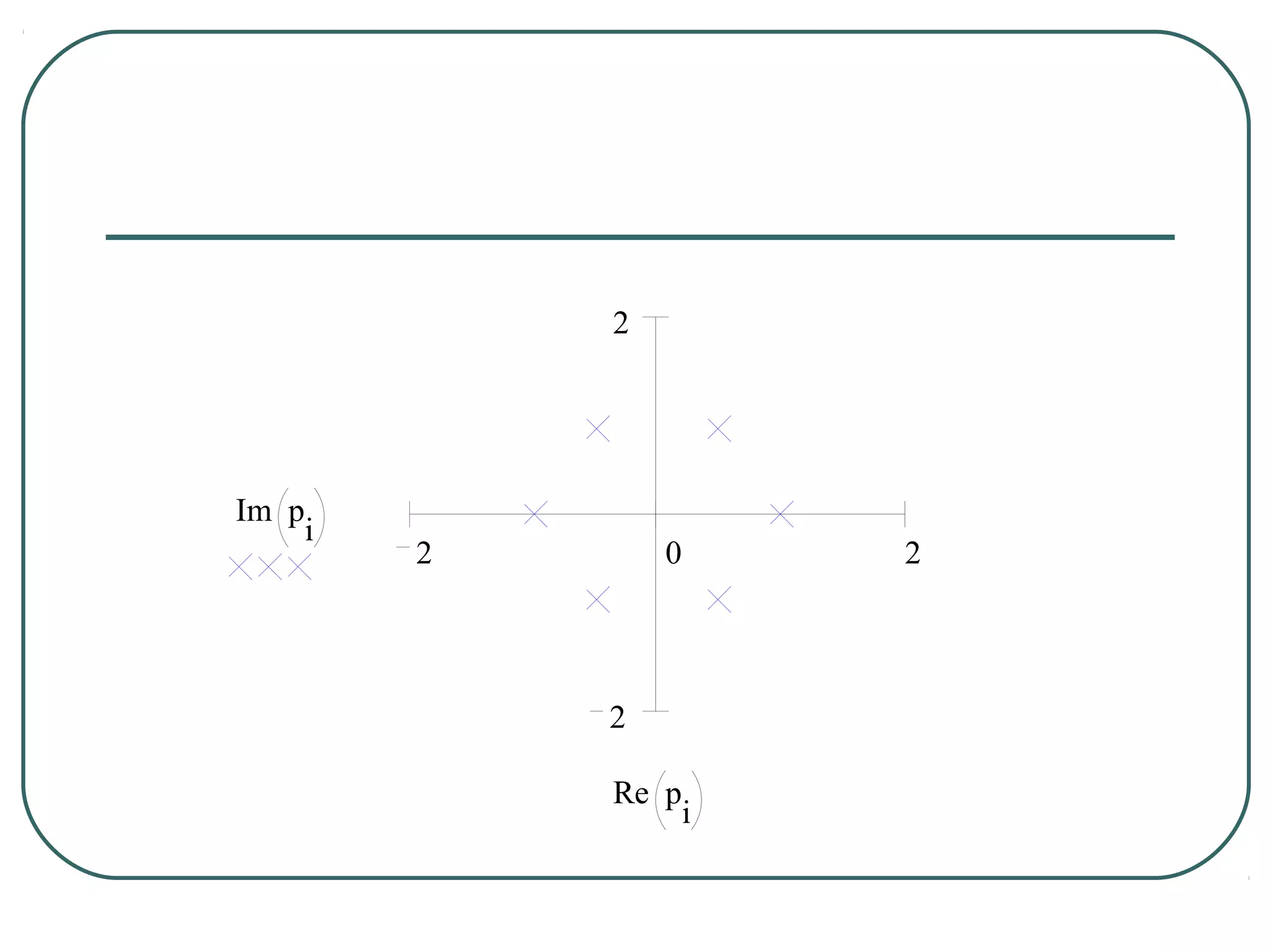

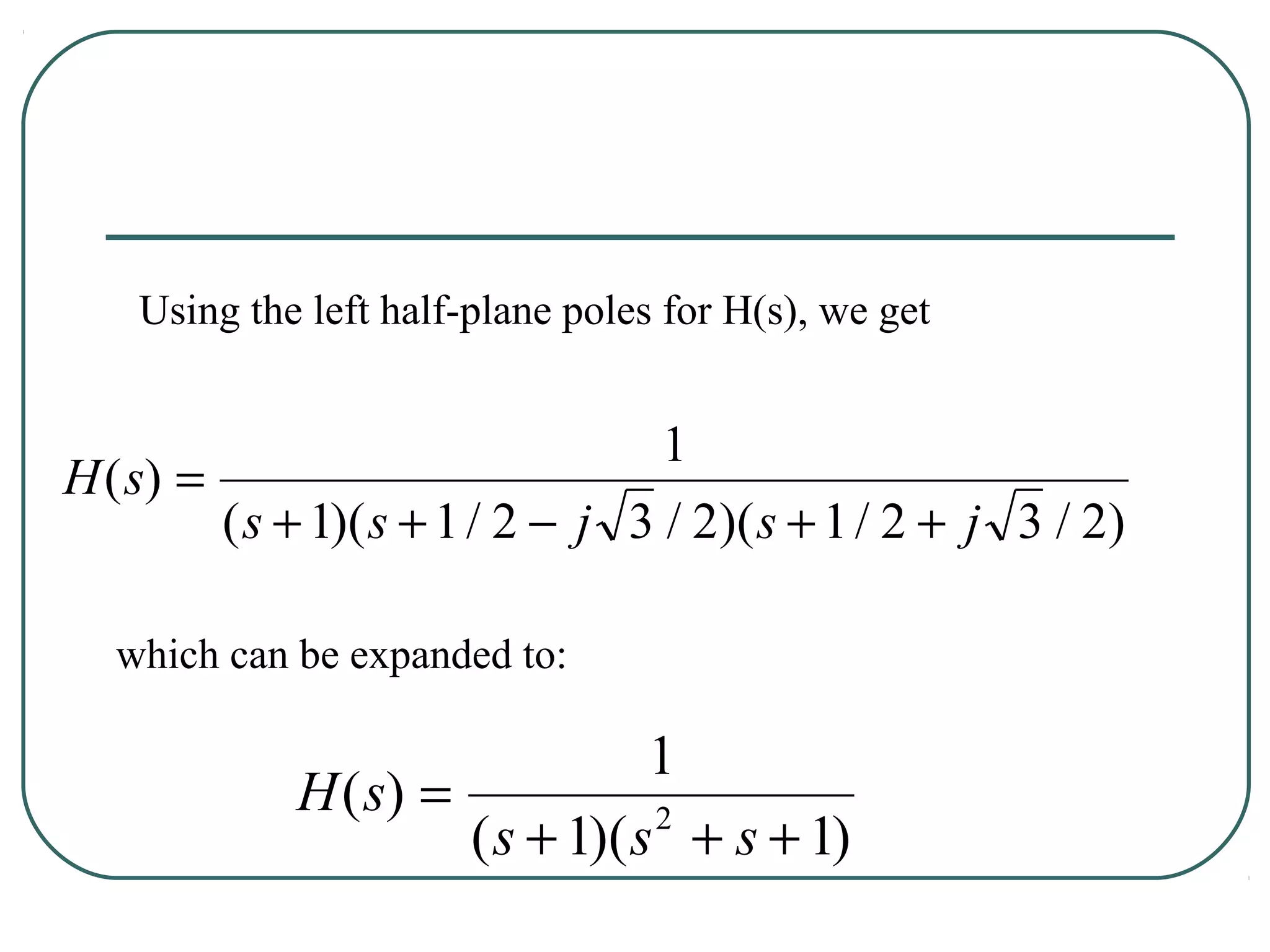

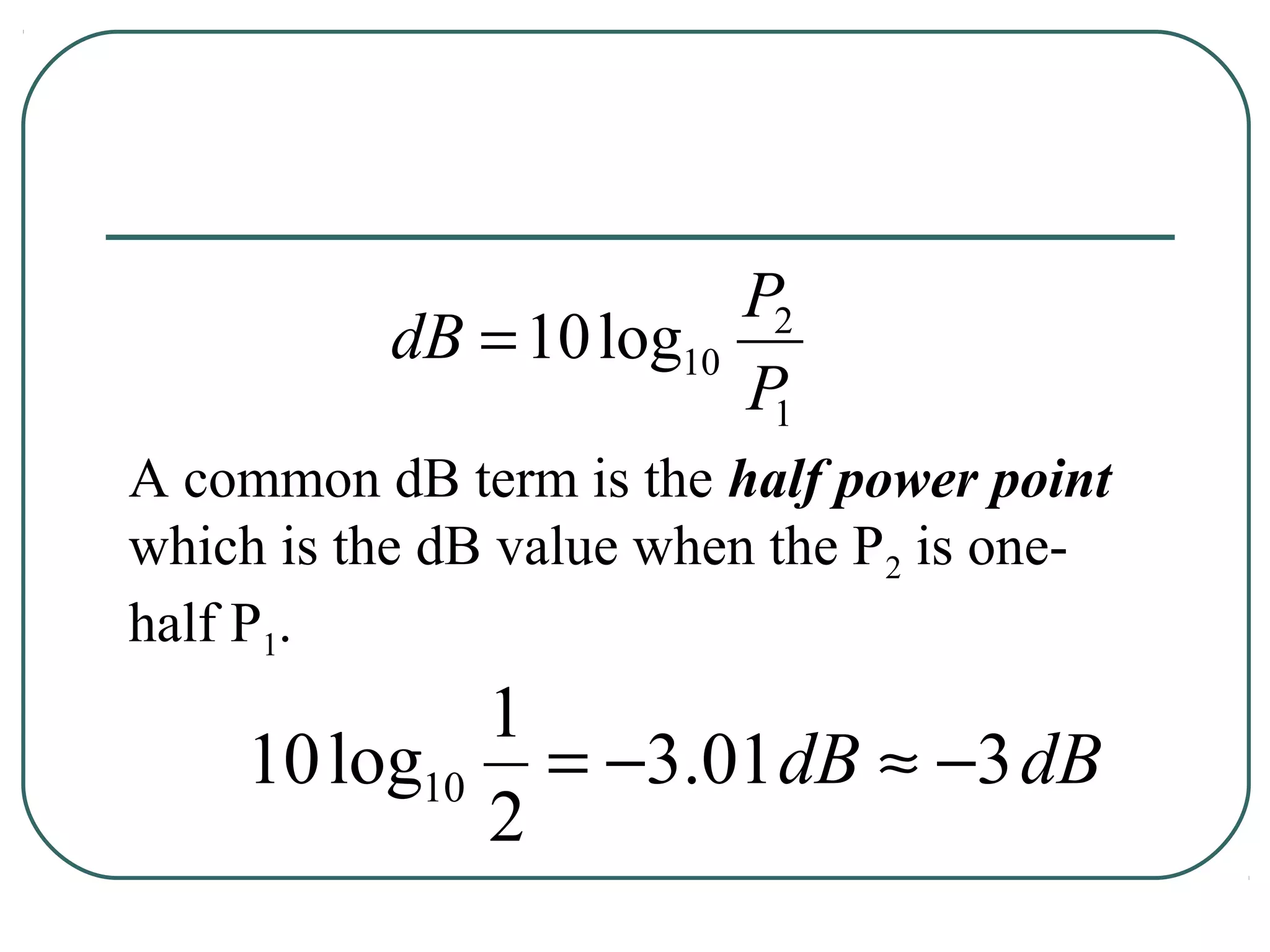

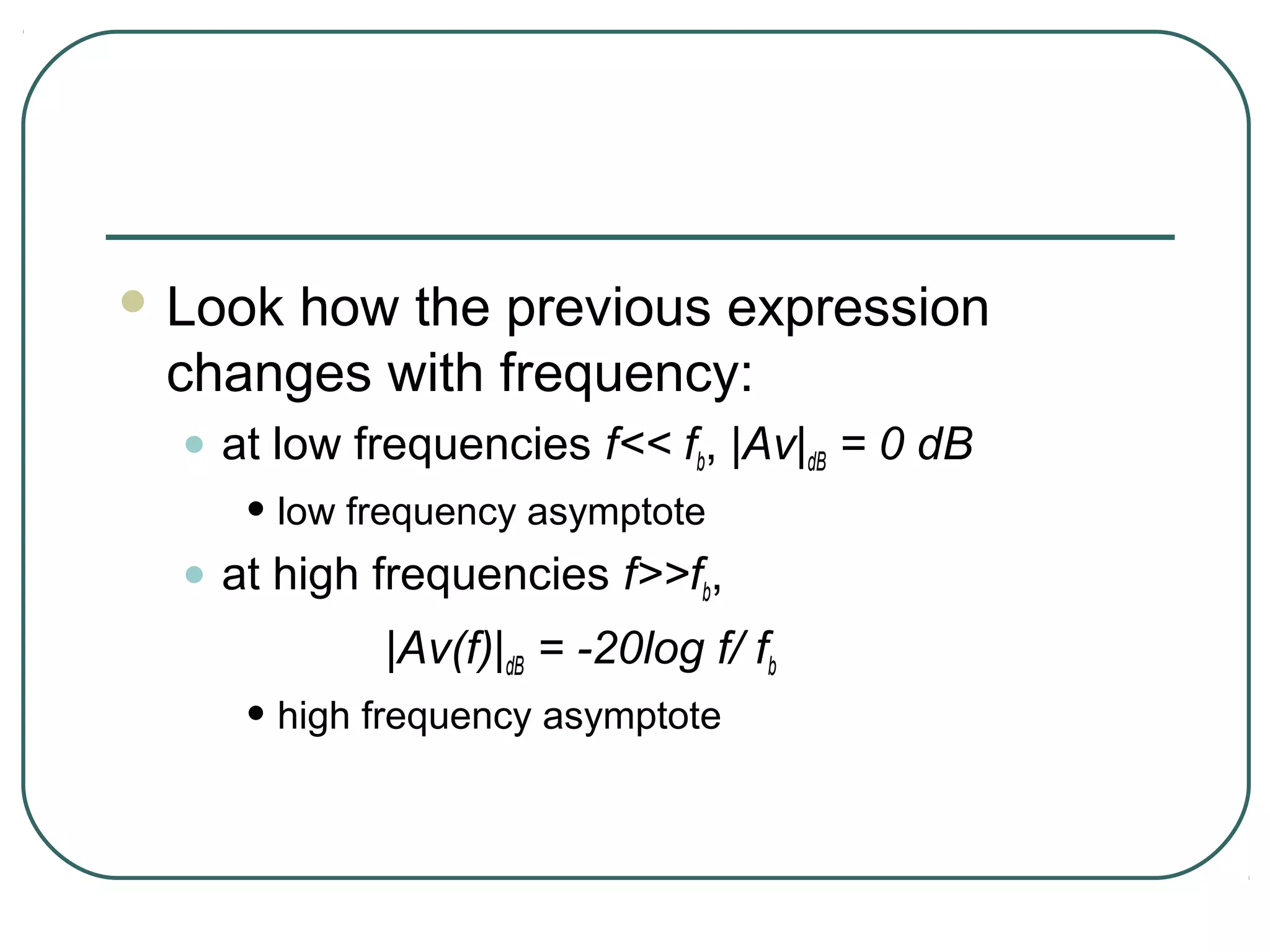

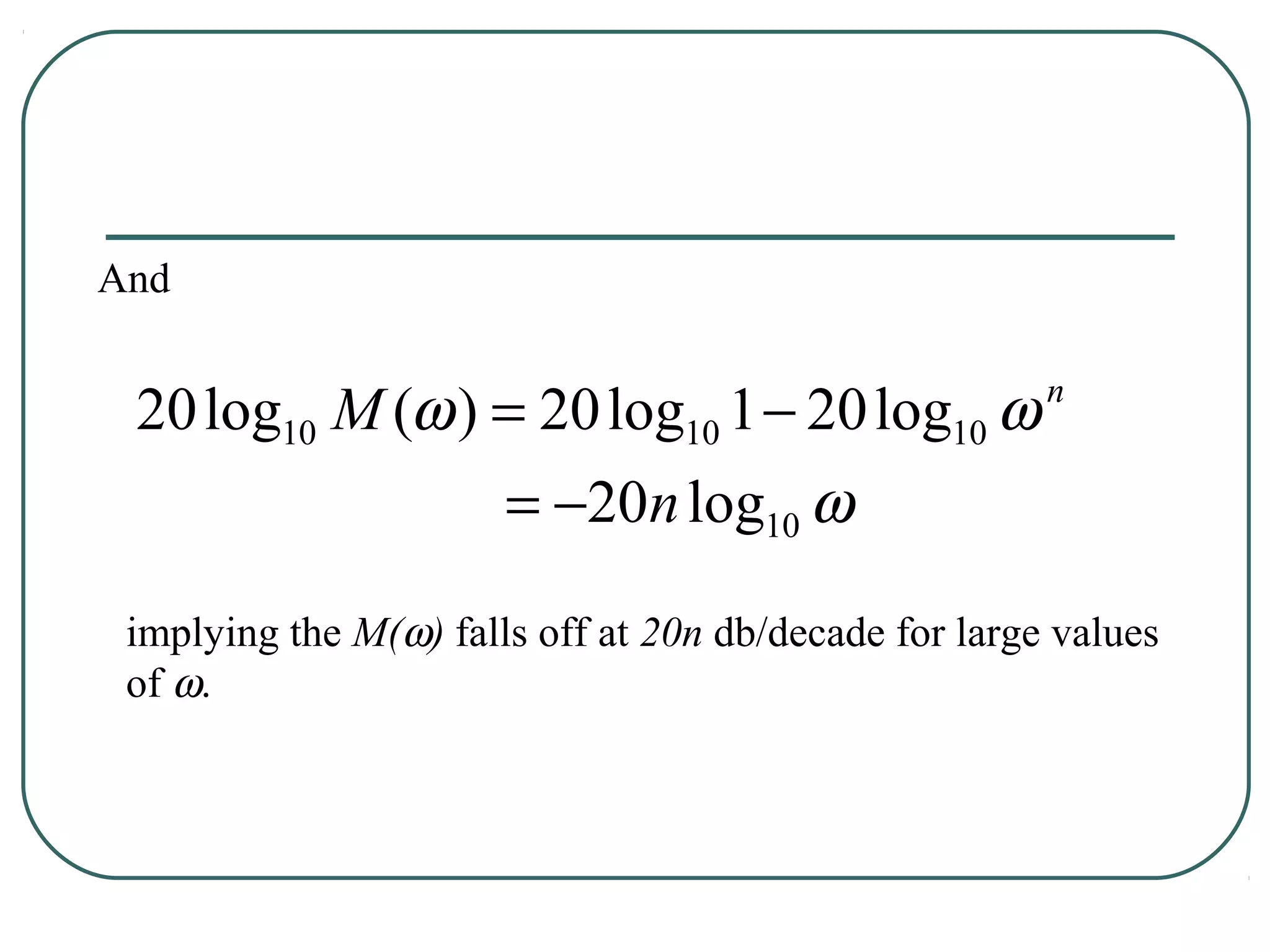

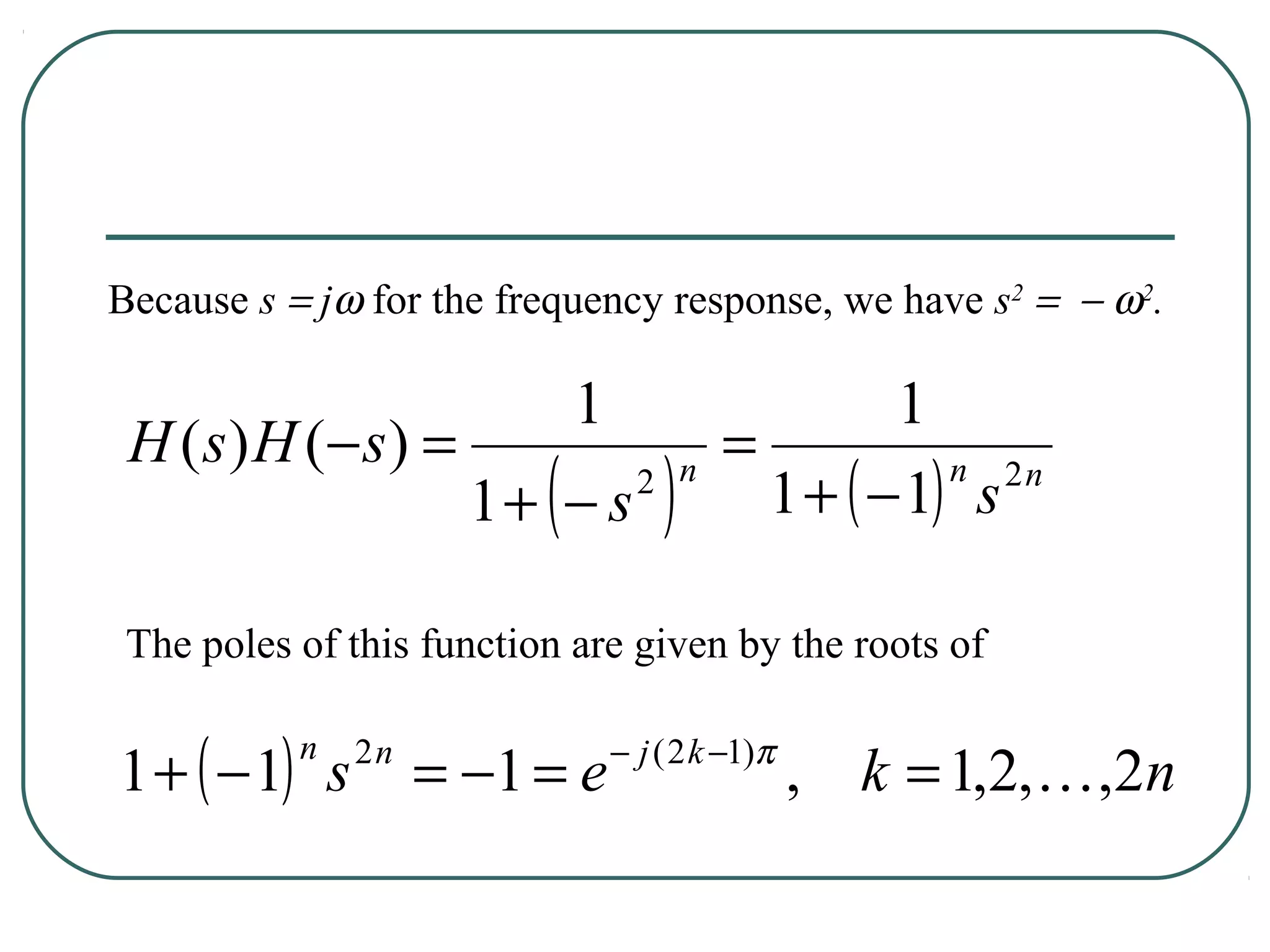

![The 2n pole are:

e j[(2k-1)/2n]π n even, k = 1,2,...,2n

sk =

e j(k/n)π n odd, k = 0,1,2,...,2n-1

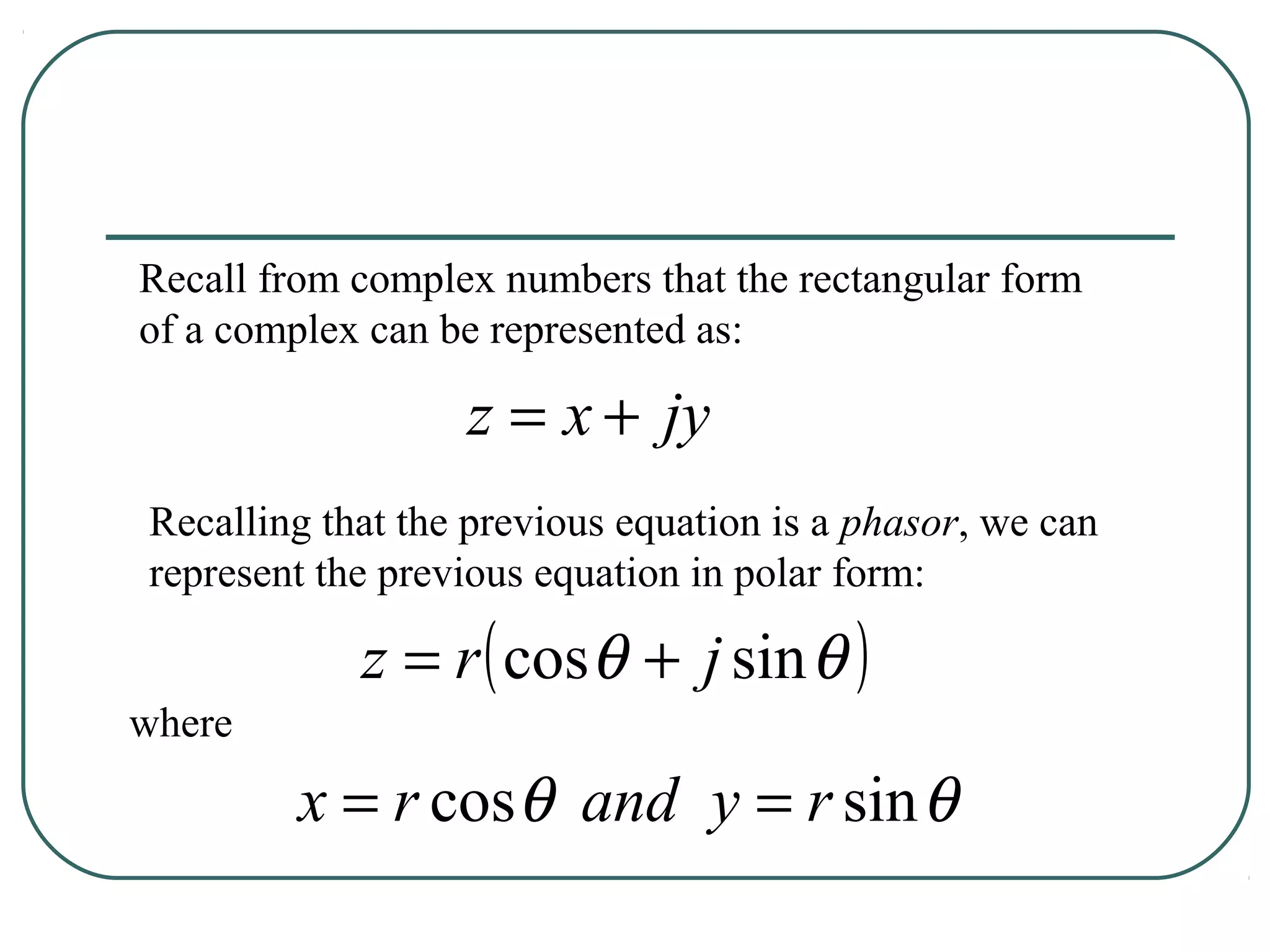

Note that for any n, the poles of the normalized Butterworth

filter lie on the unit circle in the s-plane. The left half-plane

poles are identified with H(s). The poles associated with

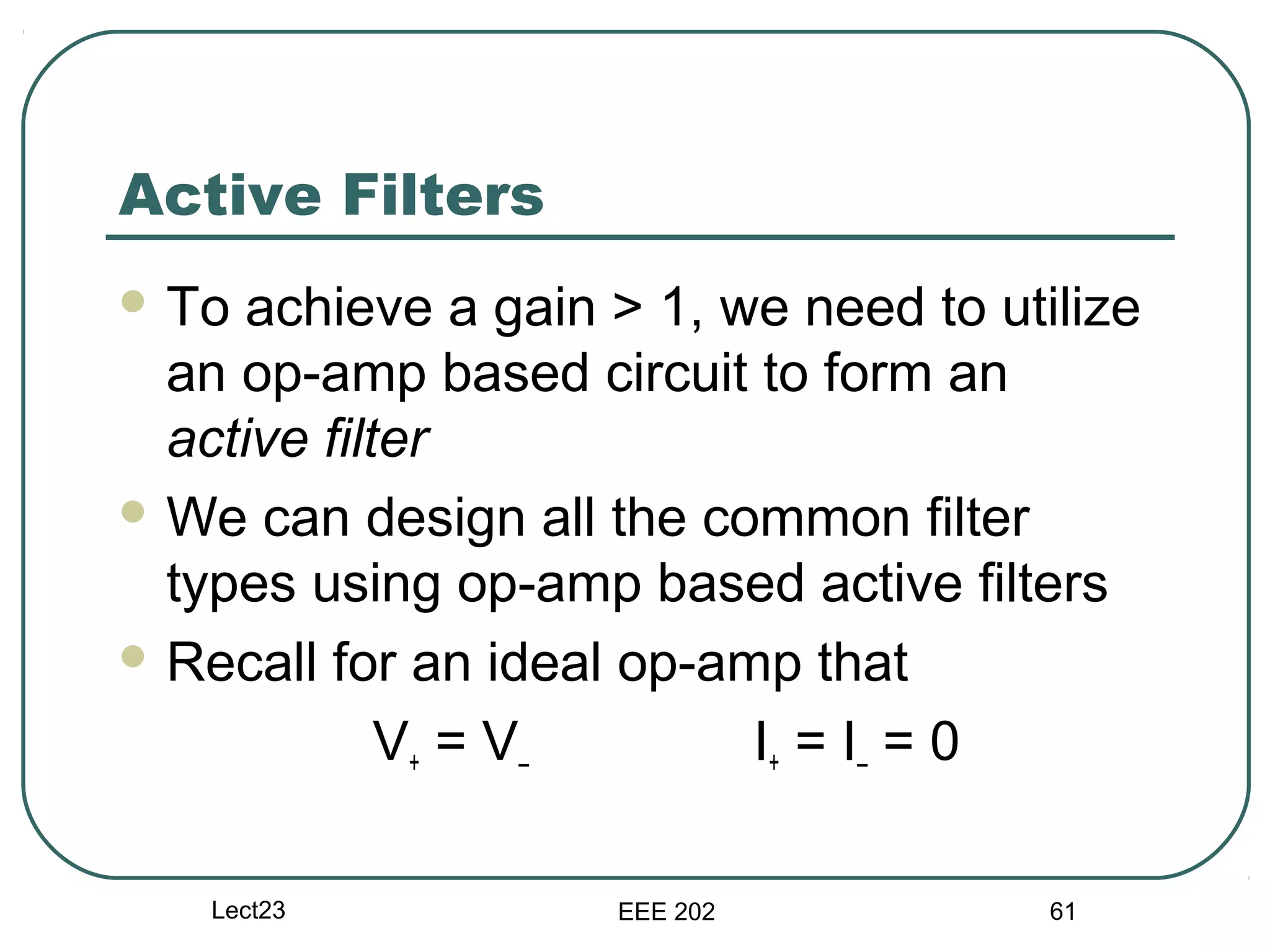

H(-s) are mirror images.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/filter-dengan-op-amp-120911070757-phpapp01/75/Filter-dengan-op-amp-40-2048.jpg)