This chapter defines an epileptic seizure as transient abnormal neuronal activity in the brain. Around 5% of people experience seizures in their lifetime, with incidence highest in infants and elderly adults. Epilepsy is defined as recurrent seizures and the consequences of this condition. A diagnosis of epilepsy can be made after one seizure if EEG or MRI findings indicate increased epileptogenicity. Drug-resistant epilepsy persists despite adequate treatment with two tolerated anti-seizure medications. Seizure freedom requires being seizure-free for at least one year while on medication.

![If the clinical history and the EEG, however, point to a

genetic epilepsy syndrome and neurologic examination

findings are normal, MRI is typically unrevealing. Genetic

epilepsy syndromes without significant imaging abnormali-

ties include rolandic epilepsy, childhood absence epilepsy,

juvenile absence epilepsy, and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

(see Table 1 in ‘‘Epilepsy Syndromes’’) (Gaillard et al.

2009).

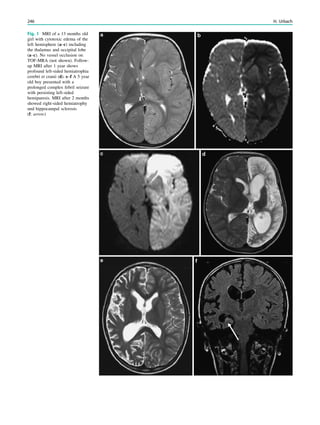

Febrile seizures occur with an incidence of 2–5% until the

age of 5 years. They are defined as seizures occurring in

febrile children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years

who do not have an intracranial infection, metabolic distur-

bance, or a history of febrile seizures. They occur most fre-

quently between the 18th and 24th months of age (90% below

3 years of age, 50% within the second year of life). Febrile

seizures are subdivided into two categories: simple (80–90%)

and complex (10–20%). Simple febrile seizures last for less

than 15 min, are generalized (without a focal component), and

occur once in a 24-h period, whereas complex febrile seizures

are prolonged (mote than 15 min), are focal, or occur more

than once in 24 h. Simple febrile seizures are not associated

with subsequent epilepsy or cognitive deficits, whereas

complex febrile seizures are linked with the development of

temporal lobe epilepsy and hippocampal sclerosis. Whether

temporal lobe epilepsy is the consequence of complex febrile

seizures or the child has complex febrile seizure because the

hippocampus was previously damaged by a prenatal or

perinatal insult or by genetic predisposition is a matter of

debate. The current concept is to consider the association

between complex febrile seizures and temporal lobe epilepsy

resulting from complex interactions between several genetic

and environmental factors. Simple febrile seizures are not an

indication for MRI, whereas complex febrile seizures are

(King et al. 1998; Bernal and Altman 2003). In patients with

temporal lobe epilepsy, 30% of patients with hippocampal

sclerosis as compared with 6% of patients without hippo-

campal sclerosis had complex febrile seizures in childhood

(Falconer et al. 1964).

1.2 Children with Epilepsy Syndromes

Children with epileptic encephalopathies (see Table 1 in

‘‘Epilepsy Syndromes’’) are studied with MRI to find an

underlying structural lesion. For example, in infants with

infantile spasms (West syndrome) tuberous sclerosis is a

common finding. However, in around 40% of patients with

this encephalopathic syndrome, no lesions are found

(Osborne et al. 2010). Rarely, a circumscribed lesion may

be found, enabling surgical resection and dramatically

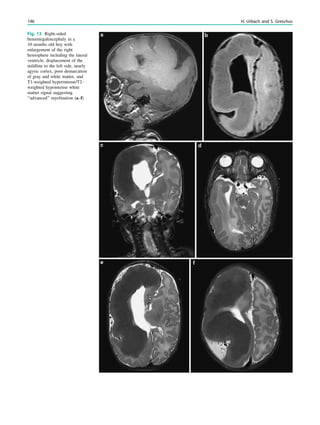

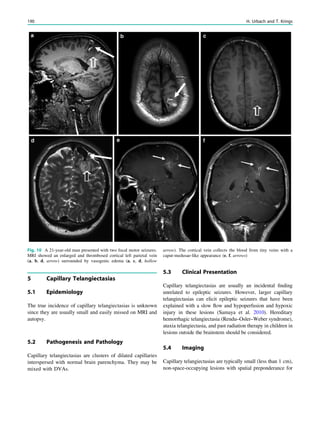

changing the child’s prognosis (Fig. 1).

In children with seizure types, age at presentation, and

EEG findings pointing to a genetic epilepsy syndrome of

(see above), MRI is typically unrevealing. Because some

nongenetic epilepsies may sometimes mimic these genetic

epilepsy syndromes, MRI is recommended in these patients

if they present with any atypical features such as abnormal

neurologic or intellectual development, difficult-to-treat

seizures, or unusual course. There is insufficient evidence to

comment on the role of not imaging in other less common

‘‘benign’’ or generalized epilepsy syndromes which may be

difficult to differentiate from symptomatic epilepsies [e.g.,

other idiopathic focal epilepsies (childhood epilepsy with

occipital paroxysms), primary reading epilepsy, and idio-

pathic generalized epilepsies (benign neonatal convulsions,

benign myoclonic epilepsies of infancy, and epilepsy with

seizures precipitated by specific modes of activation)]

(Caraballo et al. 1997a, b).

In children with focal, possibly drug-resistant epilepsy

syndromes, the effort to generate high-quality magnetic

resonance images is greatest. If these patients are uncoop-

erative and unable to tolerate sequences lasting around 5

min, general anesthesia including sedation and intubation is

needed. This effort is derived from the fact that focal cor-

tical dysplasias which may be subtle are one of the most

common causes of seizures in children with drug-resistant

epilepsy, accounting for nearly 80% of all surgically treated

cases in children under 3 years of age (Cepeda et al. 2006).

2 Preparation

Young children or those with learning difficulties are gen-

erally unable to lie still for neuroimaging. If general anes-

thesia is not available, orally administered chloral hydrate

(50–100 mg/kg body weight, maximum 2 g) may serve as

alternative (Cox et al. 2011; Schulte-Uentrop and Goepfert

2010). Finding the right chloral hydrate dose is difficult

because children may refuse, spit out, or vomit the unpal-

atable syrup. If contrast-medium injection is needed, a

‘‘needle’’ has to be placed before administering chloral

hydrate, otherwise the child will wake up, rendering con-

trast-enhanced MRI impossible. About 20% of the patients

need oxygen to keep oxygen saturation above 92%. Snoring

leads to vibration artifacts and the requirement of a special

head and neck position in the scanner.

3 Imaging

Brain magnetic resonance images of children up to 3 years

of age are different from those of adults mainly due to

incomplete white matter myelination. After 3 years of age,

the signal characteristics are similar to those in adult brains,

but the heads are smaller. In children 8 years of age or older,

the head size not longer increases appreciably with age.

38 R. Sassen and H. Urbach](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-44-320.jpg)

![Prototypically in epilepsy patients with tuberous sclero-

sis, the presence of multiple bilateral lesions can make it

difficult to identify a single lesion responsible for intractable

epileptic seizures. Using MRS, a lactate peak was detected

in the regions corresponding to an epileptic focus in some

patients (Yapici et al. 2005).

In contrast to the numerous 1

H-MRS of TLE, there are

only a few reports in other types of localization-related

epilepsies. These studies suggest that the potential of correct

seizure focus lateralization is less than in TLE.

6 MRS in Tumors

There is a wealth of literature on the use of MR spectroscopy

in neurooncology [for a systematic review, see Hollingworth

et al. (2006)]. Malignant tumors may be characterized by a

relatively large increase in choline, a loss of NAA, and

sometimes the detection of lactate or lipids. A ratio of Cho/

NAA larger than 2 has been associated with brain malig-

nancy, but it remains unclear whether this is more accurate

than results from MRI with contrast enhancement (or whe-

ther this is more accurate than MR perfusion). The incre-

mental benefit of MRS in the differentiation of low- from

high-grade brain tumors is unclear.

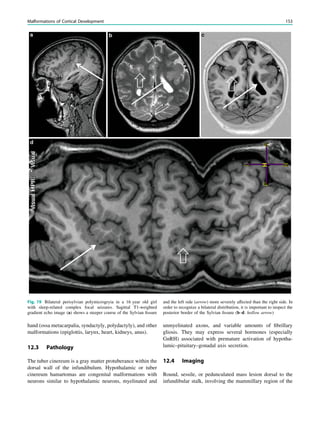

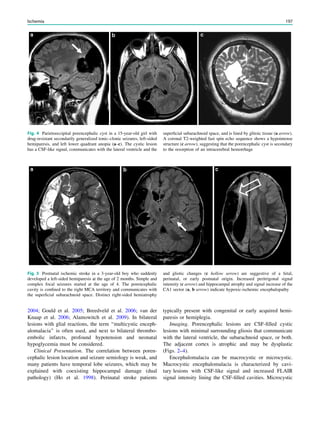

In MRS of low-grade tumors, an increase of choline

might be visible (Fig. 3).

7 MRS in Metabolic Disease and Epilepsy

In the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCL), probably the

most common progressive metabolic encephalopathies of

childhood associated with seizures, MRS is said help to

distinguish different subtypes. Infantile NCL was charac-

terized by a complete loss of NAA, a marked reduction of

Cr and Cho, and an elevation of myo-inositol and lactate in

both gray and white matter. Reduced NAA and elevated

lactate were also detected in gray and white matter of late

infantile NCL. In contrast to the infantile forms, juvenile

NCL exhibited normal metabolic profiles (McLean et al.

2008). It is questionable whether these differences are more

important for diagnosis than the age of onset.

Lactate is usually not seen in spectra of normal adult

brain. Lactate has been detected in patients with mito-

chondrial encephalopathies, but as with all other means

used to diagnose rare disorders, MR spectroscopy does not

depict elevated lactate in all cases.

8 MRS in Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy is a frequent electroclinical

epilepsy syndrome. It is considered to be a generalized

epilepsy that is treated medically and not surgically. A long-

Fig. 3 MRS a with increase in

choline b in a low grade tumor in

the right temporal lobe

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Chronic Epilepsy 61](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-65-320.jpg)

![SPECT and PET

Wim Van Paesschen, Karolien Goffin and Koen Van Laere

Contents

1 Introduction.......................................................................... 63

2 Ictal Onset Zone, Propagation Pathways,

and Functional Deficit Zone............................................... 64

2.1 Ictal SPECT........................................................................... 64

2.2 2-[18

F]Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET.................................. 64

3 Coregistration of SPECT and PET with MRI ................ 64

4 Functional Nuclear Imaging in the Presurgical

Evaluation of Refractory Focal Epilepsy ......................... 64

4.1 Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy with Hippocampal

Sclerosis ................................................................................. 64

4.2 Malformations of Cortical Development.............................. 66

4.3 Dual Pathology ...................................................................... 68

4.4 MRI-Negative Refractory Focal Epilepsy............................ 68

5 Conclusion ............................................................................ 70

References...................................................................................... 70

Abstract

Ictal perfusion single photon emission computed tomog-

raphy and positron emission tomography of brain

metabolism are functional nuclear imaging modalities

that are useful in the presurgical evaluation of patients

with refractory focal epilepsy, and provide information

on the ictal onset zone, seizure propagation pathways,

and functional deficit zones. Combined with electro-

physiological and coregistered MRI data, these tech-

niques allow a noninvasive presurgical evaluation in a

growing number of patients with refractory focal

epilepsy, and are particularly useful in patients with

normal MRI findings, focal dysplastic lesions, dual

pathology and discordant seizure symptoms, and elec-

trophysiology and morphological data. In addition, these

techniques may provide crucial information in the

planning of invasive electroencephalography studies.

1 Introduction

Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)

and positron emission tomography (PET) are functional

nuclear imaging modalities. SPECT allows the study of

cerebral perfusion during the ictal and interictal states

(Kapucu et al. 2009), and PET allows the study of cerebral

metabolic and neurochemical processes. In the epilepsy

clinic, 2-[18

F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET (FDG-PET) is

commonly used to assess interictal and rarely ictal cerebral

metabolism.

Functional nuclear imaging is most useful in the

presurgical evaluation of patients with refractory focal

epilepsy, and can delineate the ictal onset, seizure

propagation, and functional deficit zones (Rosenow and

Lüders 2001). ‘‘Functional’’ means that the imaging results

are critically dependent on the timing of tracer injection,

i.e., ictal, postictal, or interictal, and the seizure type

(Van Paesschen et al. 2007a; Goffin et al. 2008). For ictal

W. Van Paesschen (&)

Department of Neurology, University Hospital Leuven,

Herestraat 49, 3000 Leuven, Belgium

e-mail: wim.vanpaesschen@uzleuven.be

K. Goffin Á K. Van Laere

Division of Nuclear Medicine, University Hospital

Leuven and Katholieke Universiteit Leuven,

Leuven, Belgium

H. Urbach (ed.), MRI in Epilepsy, Medical Radiology. Diagnostic Imaging,

DOI: 10.1007/174_2012_561, Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013

63](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-67-320.jpg)

![SPECT interpretation, it is, therefore, important to be aware

of the seizure types, the timing of the injection, ictal

symptoms, and electroencephalography (EEG) data. Both

FDG-PET and ictal SPECT can predict seizure-free out-

come after epilepsy surgery (Knowlton et al. 2008). Ictal

SPECT is probably the most sensitive imaging modality to

delineate the ictal onset zone in extratemporal lobe epilepsy

(Knowlton et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2009).

2 Ictal Onset Zone, Propagation

Pathways, and Functional Deficit Zone

Focal seizures start in the ictal onset zone, and can propa-

gate through the brain (Rosenow and Lüders 2001). The

functional deficit zone is the part of the cortex with an

abnormal function between seizures, due to morphological

or functional factors, or both. Understanding these concepts

is crucial for proper interpretation of functional nuclear

images.

2.1 Ictal SPECT

In the absence of seizure propagation, the largest hyper-

perfusion cluster with the highest z score represents the ictal

onset zone. This pattern is usually observed with early ictal

injections during simple or complex focal seizures, or in

brain regions where ictal propagation is slow, and allows a

reliable localization of the ictal onset zone on blinded

assessment without prior knowledge of other data from the

presurgical evaluation (Dupont et al. 2006).

Often, ictal SPECT shows propagated ictal activity,

which is due to the slow time resolution of ictal SPECT

with respect to seizure propagation. The transit time of a

perfusion tracer from an arm vein to cerebral arteries is

around 30 s. In addition, there is often a delay between

seizure onset and injection of the perfusion tracer. Further,

only around 60% of the perfusion tracer is extracted by

nerve cells on the first pass (the other 40% is extracted

later), contributing to the slow time resolution of ictal

SPECT. Propagation patterns can be seen in all focal epi-

lepsies, but most often in frontal lobe epilepsy (Dupont

et al. 2006). Ictal SPECT injections during secondary gen-

eralized seizures show more areas of propagation than

during focal seizures without generalization (Varghese et al.

2009). In the case of propagation, ictal hyperperfusion can

be observed outside the ictal onset zone. The propagated

activity may be represented by the largest hyperperfusion

cluster with the highest z score, and is usually con-

nected with the hyperperfusion cluster of the ictal onset

zone though a small trail of hyperperfusion, which we

have called an ‘‘hourglass pattern’’ (Dupont et al. 2006).

Propagation may be towards another lobe, ipsilateral, or

contralateral. A reliable blinded assessment of subtraction

ictal SPECT coregistered with MRI (SISCOM) data without

knowledge of the other data from the presurgical evaluation

is often not possible.

2.2 2-[18

F]Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET

Hypometabolism on FDG-PET usually encompasses the

ictal onset zone, but tends to be larger. There is evidence to

suggest that both the ictal onset zone and seizure propaga-

tion pathways become hypometabolic interictally, repre-

senting the functional deficit zone (Rosenow and Lüders

2001; Van Paesschen et al. 2007a). The pattern of hypo-

metabolism reflects the seizure types prior to PET scanning

(Savic et al. 1997). The difference between the ictal onset

zone and the functional deficit zone is most clearly dem-

onstrated in the rare event of ictal FDG-PET scanning (Van

Paesschen et al. 2007b). In these cases, the ictal onset zone

is hypermetabolic and the functional deficit zone is hypo-

metabolic (Fig. 1).

3 Coregistration of SPECT and PET

with MRI

The most common epileptic lesions causing refractory focal

epilepsy include hippocampal sclerosis, malformations of

cortical development, tumor, vascular malformations, and

infarct/contusion (Li et al. 1995). Subtraction ictal SPECT

is routinely coregistered with MRI (SISCOM) because it

improves the clinical usefulness in localizing the ictal onset

zone and is predictive of seizure outcome (O’Brien et al.

1998, 2000). FDG-PET/MRI coregistration improves the

detection of small dysplastic lesions (Chassoux et al. 2010;

Goffin et al. 2010; Salamon et al. 2008).

4 Functional Nuclear Imaging

in the Presurgical Evaluation

of Refractory Focal Epilepsy

4.1 Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

with Hippocampal Sclerosis

4.1.1 Ictal SPECT

Ictal SPECT during a complex focal seizure in mesial

temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis usually

shows early ipsilateral neocortical temporal lobe hyperper-

fusion, frontal lobe hypoperfusion (ipsilateral more than

contralateral), contralateral cerebellar hypoperfusion, and

later parietal lobe hypoperfusion (Van Paesschen et al.

64 W. Van Paesschen et al.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-68-320.jpg)

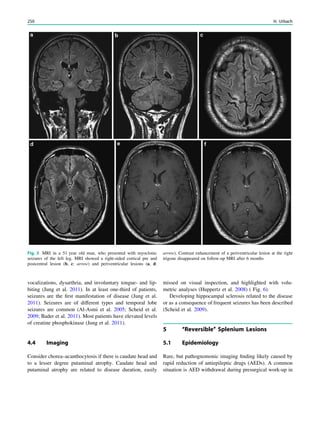

![2003; Blumenfeld et al. 2004) (Fig. 2). Ictal SPECT during

simple focal seizures in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with

hippocampal sclerosis can show a small hyperperfusion

cluster confined to the temporal lobe, or may reveal no

hyperperfusion in around 40% of cases (Van Paesschen

et al. 2000; Van Paesschen and Ictal 2004), probably

because the hyperperfusion is below the spatial resolution

of ictal SPECT, which is around 7 mm. Seizure propagation

towards the ipsilateral basal ganglia together with hypo-

perfusion of associative brain regions correlates with con-

tralateral dystonic posturing of the arm (Kim et al. 2007;

Chassagnon et al. 2009). Seizures can propagate to the

contralateral temporal lobe, and when the ictal SPECT

injection is given after seizure propagation, SISCOM may

show hyperperfusion in the contralateral temporal lobe

(Cho et al. 2010). Early ictal SPECT injection can obviate

this problem of seizure propagation (Van Paesschen et al.

2000). Different propagation patterns in mesial temporal

lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis are not of prog-

nostic significance with respect to seizure outcome after

epilepsy surgery (Kim et al. 2007).

4.1.2 2-[18

F]Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET

Interictal FDG-PET findings in mesial temporal lobe epi-

lepsy with hippocampal sclerosis have been well described.

Hypometabolism is present in the ipsilateral temporal lobe

in around 95% of cases, but also in regions outside the ictal

onset zone, including the contralateral temporal lobe in up

to 40% of cases, the ipsilateral thalamus in around 65% of

cases, ipsilateral basal ganglia in 45% of cases, the ipsi-

lateral insula in 50% of cases, the ipsilateral basal frontal

lobe in around 30% of cases, and the ipsilateral parietal lobe

in up to 30% of cases (Henry et al. 1990, 1993) (Fig. 2). In

mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis,

the extent and severity of hypometabolism is not related to

surgical outcome (Lee et al. 2002). Interictal ipsilateral

frontal lobe hypometabolism in mesial temporal lobe epi-

lepsy with hippocampal sclerosis tends to coincide with

ictal SPECT hypoperfusion, which could represent surround

inhibition (Nelissen et al. 2006). Frontal lobe hypometab-

olism in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal

sclerosis could explain frontal lobe cognitive deficits

(Takaya et al. 2006; Jokeit et al. 1997).

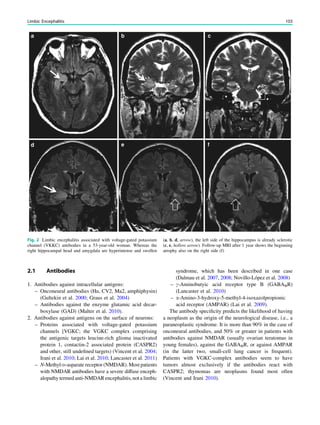

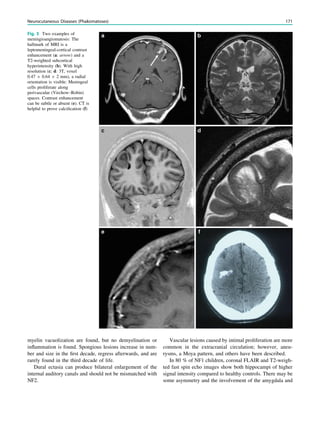

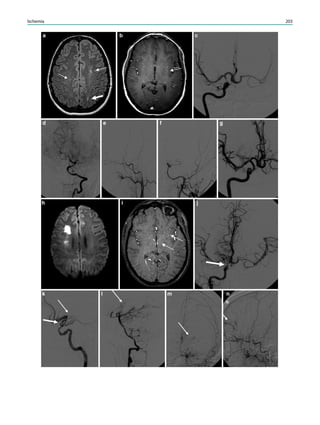

Fig. 1 2-[18

F]Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomogra-

phy (PET) in Rasmussen encephalitis. a Three-dimensional stereotac-

tic surface projection analysis of ictal PET. The patient was a

26-year-old woman with Rasmussen encephalitis affecting the right

cerebral hemisphere, with left-sided focal motor status epilepticus.

Ictal PET was performed because electroencephalography did not

allow lateralization, and showed hypermetabolism in the right

hemisphere, consistent with status epilepticus. The left hemisphere

was severely hypometabolic. b Stereotactic surface projection analysis

of interictal PET images 1 year after a right functional hemispherot-

omy, which rendered her seizure-free. The right hemisphere became

hypometabolic. The structurally normal left hemisphere became

normometabolic, which was accompanied by important cognitive

improvements, consistent with a recovery of the functional deficit zone

SPECT and PET 65](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-69-320.jpg)

![outcome. In refractory focal epilepsy due to a single MRI-

visible focal dysplastic lesion, we found that overlap between

the SISCOM hyperperfusion cluster and the MRI-visible

focal dysplastic lesion in a noninvasive presurgical evalua-

tion with concordant data may suffice to proceed to epilepsy

surgery aimed at removing the MRI-visible focal dysplastic

lesion and the part of the hyperperfusion cluster within and

immediately surrounding the focal dysplastic lesion (Dupont

et al. 2006) (Fig. 3).

4.2.2 2-[18

F]Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET

Focal cortical dysplasia shows a focal or regional area of

hypometabolism on FDG-PET in around 65–80% of cases

(Chassoux et al. 2010; Goffin et al. 2010; Salamon et al.

2008; Kim et al. 2011). FDG-PET/MRI coregistration and

partial volume correction improves detection of cortical

dysplasia (Chassoux et al. 2010; Goffin et al. 2010; Salamon

et al. 2008). FDG-PET is especially useful to detect the

milder Palmini type I lesions, which may not be visible on

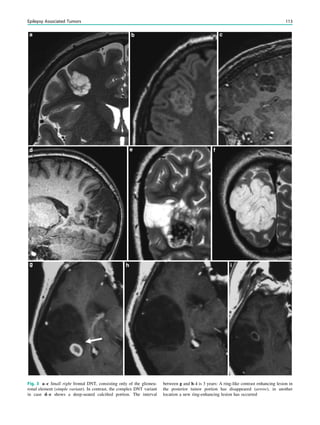

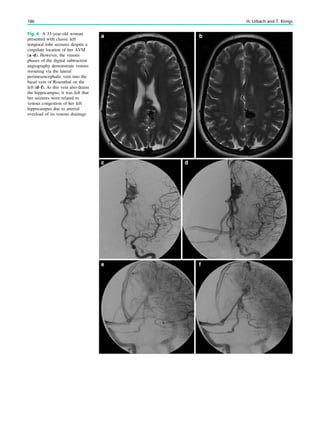

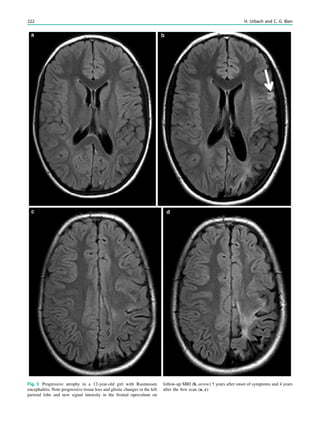

Fig. 3 Multimodality imaging

in the presurgical evaluation of

refractory focal epilepsy. The

patient was a 14-year-old boy

with refractory frontal lobe

epilepsy with focal motor

seizures in his left limbs. a Fluid-

attenuated inversion recovery

(FLAIR) showed a focal cortical

dysplasia that was visible as an

area of slightly hyperintense and

thickened cortex, located on the

medial border of the right

superior frontal gyrus (white

cross). b Multimodal imaging

including magnetization-

prepared rapid gradient echo,

subtracted ictal SPECT (red), and

motor functional MRI of the foot

(yellow), hand (green), and

corticospinal tract (blue),

coregistered with FLAIR (a). The

SISCOM hyperperfusion cluster

overlapped with the focal cortical

dysplasia, which provided an

excellent delineation of the

epileptogenic zone, i.e., the

region that the neurosurgeon has

to remove to render the patient

seizure-free. However, motor

functional MRI of the foot

confirmed that the epileptic

lesion was within eloquent

cortex. Surgery has not been

offered

SPECT and PET 67](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-71-320.jpg)

![MRI (Kim et al. 2009; Salamon et al. 2008) (Fig. 4). FDG-

PET hypometabolism is often present outside the location

of the focal dysplastic lesion, consistent with the observa-

tion that the functional deficit zone tends to be larger than

the epileptogenic zone (Goffin et al. 2010). It remains,

therefore, important to interpret FDG-PET in the context of

a full presurgical evaluation.

4.3 Dual Pathology

Dual pathology, i.e., two or more epileptic lesions, is detected

on MRI in around 5–20% of patients referred for presurgical

evaluation (Li et al. 1999). Often, one of the two lesions is

hippocampal sclerosis. Malformations of cortical develop-

ment and porencephalic cysts are more frequently associated

with hippocampal sclerosis than other epileptic lesions, such

as low-grade gliomas and vascular malformations (Blümcke

et al. 2011; Cendes et al. 1995). Focal cortical dysplasia

type III occurs in combination with hippocampal sclerosis,

epilepsy-associated tumors, vascular malformations, and

epileptogenic lesions acquired in early life (i.e., traumatic

injury, ischemic injury, or encephalitis) (Blümcke et al. 2011).

4.3.1 Ictal SPECT

In patients with dual pathology including hippocampal

sclerosis, removal of the two lesions may be the best sur-

gical approach (Li et al. 1999). However, patients with

mesial temporal lobe epilepsy and hippocampal sclerosis

and an extratemporal porencephalic cyst can be rendered

seizure-free after temporal lobectomy (Burneo et al. 2003).

In our experience, ictal SPECT can be highly accurate to

pinpoint hippocampal sclerosis as the ictal onset zone in

patients with dual pathology (Fig. 5). Valenti et al. (2002)

reported ictal SPECT hyperperfusion within dysembryo-

plastic neuroepithelial tumors, extending into areas of

dysplastic tissue that were not visible on MRI.

4.3.2 2-[18

F]Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET

Diehl et al. (2003) reported FDG-PET in patients with

hippocampal sclerosis with and without associated micro-

scopic cortical dysplasia. In hippocampal sclerosis with

concurrent temporal neocortical microscopic cortical dys-

plasia, the most prominent hypometabolism was in the

temporal neocortex. In isolated hippocampal sclerosis

without cortical dysplasia, the most pronounced hypome-

tabolism was in the mesial temporal lobe. Patients with

tuberous sclerosis complex tend to have multiple tubers.

Removal of the epileptic tubers may render these patients

seizure-free. FDG-PET is useful in the non-invasive pre-

surgical evaluation of these patients. Some of the tubers in

the epileptogenic zone may display the largest volume of

hypometabolism relative to the actual tuber volume

(Salamon et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2010).

4.4 MRI-Negative Refractory

Focal Epilepsy

Around 25% of patients with refractory focal epilepsy have

no epileptic lesion on MRI (Li et al. 1995; Duncan 2010).

As a group, around 40% of patients with MRI-negative

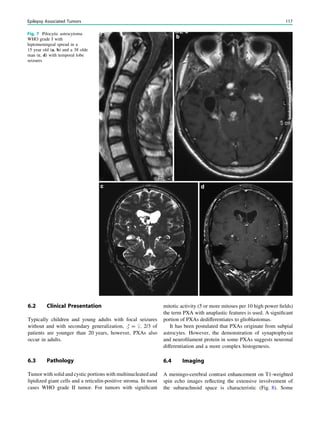

Fig. 4 MRI-negative, SPECT/

PET-positive temporal lobe

epilepsy. The patient was a

27-year-old man with a 5-year

history of refractory MRI-

negative temporal lobe epilepsy.

SISCOM showed a left

anterotemporal hyperperfusion

cluster. FDG-PET showed left

temporal hypometabolism. He

underwent a left anterotemporal

lobectomy, including the

amygdala and with sparing of the

hippocampus. He has remained

seizure-free for more than 1 year.

Pathology demonstrated focal

cortical dysplasia type I

68 W. Van Paesschen et al.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-72-320.jpg)

![focal epilepsy are rendered seizure-free after epilepsy sur-

gery, and have a worse prognosis compared with patients

with refractory focal epilepsy and an epileptic lesion on

MRI (Lee et al. 2005).

4.4.1 Ictal SPECT

In MRI-negative refractory focal epilepsy, reevaluation of the

MRI, guided by the ictal SPECT, reveals small focal dys-

plastic lesions in around 15% of cases (Van Paesschen et al.

2007a; Van Paesschen and Ictal 2004) (Fig. 6). SISCOM can

be used to guide placement of intracranial electrodes

(Ahnlide et al. 2007). SISCOM may alter and extend the

strategy for electrode placement in invasive recording.

Favorable surgical outcome has been observed when intra-

cranial EEG was concordant with SISCOM hyperperfusion.

SISCOM localization, therefore, is an independent method

with an impact in patients with refractory partial epilepsy

scheduled for intracranial EEG studies. In comparison with

MRI, FDG-PET, magnetoencephalography, and scalp EEG,

ictal SPECT is probably the most sensitive technique to

localize the ictal onset zone in extratemporal lobe epilepsy,

and to predict a seizure-free outcome after epilepsy surgery

(Knowlton et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2009).

4.4.2 2-[18

F]Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET

FDG-PET may be useful in MRI-negative temporal lobe

epilepsy. Good surgical results have been reported in

patients with MRI-negative refractory temporal lobe epi-

lepsy and unilateral temporal hypometabolism (Fig. 4).

MRI-negative, PET-positive temporal lobe epilepsy may

represent a surgically remediable syndrome distinct from

mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, with focal hypometabolism

involving primarily lateral neocortical rather than mesial

temporal structures (Lee et al. 2005; Carne et al. 2004).

FDG-PET is most useful in patients with temporal lobe

epilepsy when MRI findings are normal or when MRI does

not show unilateral temporal lobe abnormalities, and when

ictal EEG results are not concordant with MRI findings or

seizure symptoms (Uijl et al. 2007).

5 Conclusion

Ictal SPECT and FDG-PET are functional nuclear imaging

modalities which may provide additional information in the

noninvasive presurgical evaluation of patients with refrac-

tory focal epilepsy when MRI shows a malformation of

cortical development (Dupont et al. 2006), dual pathology,

or MRI-negative cases, or when the data from the presur-

gical evaluation are discordant. Both may facilitate the

detection of a subtle focal dysplastic lesion when the MRI

findings were initially reported as normal, and may allow

epilepsy surgery after a noninvasive presurgical evaluation.

Ictal SPECT may guide placement of electrodes and grids

for invasive EEG studies. Ictal SPECT and FDG-PET can

be integrated in a multimodal image, including MRI, trac-

tography, EEG–functional MRI and magnetoencephalog-

raphy, allowing accurate surgical planning. Both FDG-PET

and ictal SPECT can predict seizure-free outcome after

epilepsy surgery (Knowlton et al. 2008).

References

Ahnlide JA, Rosen I, Linden-Mickelsson TP, Kallen K (2007) Does

SISCOM contribute to favorable seizure outcome after epilepsy

surgery? Epilepsia 48:579–588

Barkovich AJ, Kuzniecky RI, Jackson GD, Guerrini R, Dobyns WB

(2005) A developmental and genetic classification for malforma-

tions of cortical development. Neurology 27(65):1873–1887

Blümcke I, Thom M, Aronica E et al (2011) The clinicopathologic

spectrum of focal cortical dysplasias: a consensus classification

proposed by an ad hoc task force of the ILAE Diagnostic Methods

Commission. Epilepsia 52:158–174

Blumenfeld H, McNally KA, Vanderhill SD et al (2004) Positive and

negative network correlations in temporal lobe epilepsy. Cereb

Cortex 14:892–902

Burneo JG, Faught E, Knowlton RC et al (2003) Temporal lobectomy

in congenital porencephaly associated with hippocampal sclerosis.

Arch Neurol 60:830–834

Carne RP, O’Brien TJ, Kilpatrick CJ et al (2004) MRI-negative PET-

positive temporal lobe epilepsy: a distinct surgically remediable

syndrome. Brain 127:2276–2285

Cendes F, Cook MJ, Watson C et al (1995) Frequency and

characteristics of dual pathology in patients with lesional epilepsy.

Neurology 45:2058–2064

Chang EF, Wang DD, Barkovich AJ et al (2011) Predictors of seizure

freedom after surgery for malformations of cortical development.

Ann Neurol 70:151–162

Chassagnon S, Namer IJ, Armspach JP et al (2009) SPM analysis of

ictal-interictal SPECT in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: relation-

ships between ictal semiology and perfusion changes. Epilepsy Res

85:252–260

Chassoux F, Rodrigo S, Semah F et al (2010) FDG-PET improves

surgical outcome in negative MRI Taylor-type focal cortical

dysplasias. Neurology 14(75):2168–2175

Cho JW, Hong SB, Lee JH et al (2010) Contralateral hyperperfusion

and ipsilateral hypoperfusion by ictal SPECT in patients with

mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 88:247–254

Diehl B, LaPresto E, Najm I et al (2003) Neocortical temporal FDG-

PET hypometabolism correlates with temporal lobe atrophy in

hippocampal sclerosis associated with microscopic cortical dys-

plasia. Epilepsia 44:559–564

Duncan JS (2010) Imaging in the surgical treatment of epilepsy. Nat

Rev Neurol 6:537–550

Dupont P, Van Paesschen W, Palmini A et al (2006) Ictal perfusion

patterns associated with single MRI-visible focal dysplastic

lesions: implications for the noninvasive delineation of the

epileptogenic zone. Epilepsia 47:1550–1557

Goffin K, Dedeurwaerdere S, Van Laere KJ, Van Paesschen W (2008)

Neuronuclear assessment of patients with epilepsy. Semin Nucl

Med 38:227–239

Goffin K, Van Paesschen W, Dupont P et al (2010) Anatomy-based

reconstruction of FDG-PET images with implicit partial volume

correction improves detection of hypometabolic regions in patients

70 W. Van Paesschen et al.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-74-320.jpg)

![with epilepsy due to focal cortical dysplasia diagnosed on MRI.

Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 37:1148–1155

Henry TR, Mazziotta JC, Engel J Jr et al (1990) Quantifying interictal

metabolic activity in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J Cereb Blood

Flow Metab 10:748–757

Henry TR, Mazziotta JC, Engel J Jr (1993) Interictal metabolic anatomy

of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol 50:582–589

Jokeit H, Seitz RJ, Markowitsch HJ, Neumann N, Witte OW, Ebner A

(1997) Prefrontal asymmetric interictal glucose hypometabolism

and cognitive impairment in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.

Brain 120(Pt 12):2283–2294

Kapucu OL, Nobili F, Varrone A et al (2009) EANM procedure guideline

for brain perfusion SPECT using 99mTc-labelled radiopharmaceuti-

cals, version 2. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 36:2093–2102

Kim JH, Im KC, Kim JS et al (2007) Ictal hyperperfusion patterns in

relation to ictal scalp EEG patterns in patients with unilateral

hippocampal sclerosis: a SPECT study. Epilepsia 48:270–277

Kim JT, Bai SJ, Choi KO et al (2009) Comparison of various imaging

modalities in localization of epileptogenic lesion using epilepsy

surgery outcome in pediatric patients. Seizure 18:504–510

Kim YH, Kang HC, Kim DS et al (2011) Neuroimaging in identifying

focal cortical dysplasia and prognostic factors in pediatric and

adolescent epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia 52:722–727

Knowlton RC, Elgavish RA, Bartolucci A et al (2008) Functional imaging:

II. Prediction of epilepsy surgery outcome. Ann Neurol 64:35–41

Lee SK, Lee DS, Yeo JS et al (2002) FDG-PET images quantified by

probabilistic atlas of brain and surgical prognosis of temporal lobe

epilepsy. Epilepsia 43:1032–1038

Lee SK, Lee SY, Kim KK, Hong KS, Lee DS, Chung CK (2005)

Surgical outcome and prognostic factors of cryptogenic neocortical

epilepsy. Ann Neurol 58:525–532

Li LM, Fish DR, Sisodiya SM, Shorvon SD, Alsanjari N, Stevens JM

(1995) High resolution magnetic resonance imaging in adults with

partial or secondary generalised epilepsy attending a tertiary

referral unit. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 59:384–387

Li LM, Cendes F, Andermann F et al (1999) Surgical outcome in patients

with epilepsy and dual pathology. Brain 122(Pt 5):799–805

Lüders H, Schuele SU (2006) Epilepsy surgery in patients with

malformationsofcorticaldevelopment.CurrOpinNeurol19:169–174

Marusic P, Najm IM, Ying Z et al (2002) Focal cortical dysplasias in

eloquent cortex: functional characteristics and correlation with

MRI and histopathologic changes. Epilepsia 43:27–32

Nelissen N, Van Paesschen W, Baete K et al (2006) Correlations of

interictal FDG-PET metabolism and ictal SPECT perfusion

changes in human temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal

sclerosis. Neuroimage 15(32):684–695

O’Brien TJ, So EL, Mullan BP et al (1998) Subtraction ictal SPECT

co-registered to MRI improves clinical usefulness of SPECT in

localizing the surgical seizure focus. Neurology 50:445–454

O’Brien TJ, So EL, Mullan BP et al (2000) Subtraction peri-ictal

SPECT is predictive of extratemporal epilepsy surgery outcome.

Neurology 12(55):1668–1677

O’Brien TJ, So EL, Cascino GD et al (2004) Subtraction SPECT

coregistered to MRI in focal malformations of cortical develop-

ment: localization of the epileptogenic zone in epilepsy surgery

candidates. Epilepsia 45:367–376

Palmini A, Najm I, Avanzini G et al (2004) Terminology and

classification of the cortical dysplasias. Neurology 23(62):S2–S8

Rosenow F, Lüders H (2001) Presurgical evaluation of epilepsy. Brain

124:1683–1700

Salamon N, Kung J, Shaw SJ et al (2008) FDG-PET/MRI coregistra-

tion improves detection of cortical dysplasia in patients with

epilepsy. Neurology 11(71):1594–1601

Savic I, Altshuler L, Baxter L, Engel J Jr (1997) Pattern of interictal

hypometabolism in PET scans with fludeoxyglucose F 18 reflects

prior seizure types in patients with mesial temporal lobe seizures.

Arch Neurol 54:129–136

Takaya S, Hanakawa T, Hashikawa K et al (2006) Prefrontal

hypofunction in patients with intractable mesial temporal lobe

epilepsy. Neurology 14(67):1674–1676

Uijl SG, Leijten FS, Arends JB, Parra J, van Huffelen AC, Moons KG

(2007) The added value of [18F]-fluoro-D-deoxyglucose positron

emission tomography in screening for temporal lobe epilepsy

surgery. Epilepsia 48:2121–2129

Valenti MP, Froelich S, Armspach JP et al (2002) Contribution of

SISCOM imaging in the presurgical evaluation of temporal lobe

epilepsy related to dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors. Epi-

lepsia 43:270–276

Van Paesschen W (2004) Ictal SPECT. Epilepsia 45(Suppl 4):

35–40

Van Paesschen W, Dupont P, Van Heerden B et al (2000) Self-

injection ictal SPECT during partial seizures. Neurology 23(54):

1994–1997

Van Paesschen W, Dupont P, Van Driel G, Van Billoen H, Maes A

(2003) SPECT perfusion changes during complex partial seizures

in patients with hippocampal sclerosis. Brain 126:1103–1111

Van Paesschen W, Dupont P, Sunaert S, Goffin K, Van Laere KJ

(2007a) The use of SPECT and PET in routine clinical practice in

epilepsy. Curr Opin Neurol 20:194–202

Van Paesschen W, Porke K, Fannes K et al (2007b) Cognitive deficits

during status epilepticus and time course of recovery: a case report.

Epilepsia 48:1979–1983

Varghese GI, Purcaro MJ, Motelow JE et al (2009) Clinical use of ictal

SPECT in secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Brain

132:2102–2113

Wu JY, Salamon N, Kirsch HE et al (2010) Noninvasive testing, early

surgery, and seizure freedom in tuberous sclerosis complex.

Neurology 2(74):392–398

SPECT and PET 71](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-75-320.jpg)

![4. Electromagnetic compatibility.

5. Acoustic noise.

6. Interaction among devices

7. Safe functioning of the device.

8. Safe operation of the MRI system.

The greatest concern is thermal injury from RF pulses.

Heating may occur around the VNS or DBS or along the

subdural or depth electrodes, but is more likely to occur at

the noninsulated ends of the electrodes. Experimental

investigations of cardiac pacemakers showed a higher

temperature increase in patients with abandoned leads than

in patients with leads attached to the pacemaker (Langman

et al. 2011). Thus, patients with abandoned or broken leads

around the vagus nerve after explanting a VNS could show

a higher temperature increase than patients with an

implanted VNS. Heating is considered harmful as it could

result in tissue damage in the brain parenchyma or the vagus

nerve and/or surrounding structures in the carotid sheath.

A measure to assess the amount of energy deposited by a

radiofrequency field in a certain mass of tissue is the spe-

cific absorption rate. The units for SAR are therefore given

in watts per kilogram [W/kg]. The SAR produced during an

MRI study is a complex function of various variables. SAR

is proportional to the square of the field strength, the square

of the RF flip angle, the duty cycle which is influenced by

the repetition time, the type of transmit coil and the volume,

electrical conductivity and anatomical configuration of the

tissue contained within the transmit coil. This relationship

already implies that stronger magnets and larger RF flip-

angles applied in a short time interval will result in higher

energy deposition (Shellock 2008). Unfortunately, the SAR

is calculated differently by different MRI system manufac-

turers and even varies for different systems with identical

field strength produced by the same manufacturer. For

example, the SAR is higher in a long-bore system than in a

short-bore system. The SAR can be averaged over the

whole body or the head only, and the averaged whole-body

SAR should not exceed 4 W/kg in any MRI examination.

For a given MRI system, a higher SAR leads to greater

heating.

Other concerns with respect to VNS or DBS are inad-

vertent device reset erasing historical information stored in

the device or inadvertent magnet mode activation from the

magnetic fields.

In 2005, ASTM International introduced the criteria

MRI-safe, MRI-conditional and MRI-unsafe (ASTM Inter-

national 2005). With respect to these criteria, the devices

mentioned above are defined as MRI-conditional, i.e., MRI

is considered safe under specified conditions of use. Inter-

estingly, neither the FDA nor the International Electro-

technical Commission has specified these conditions for the

different metallic implants, but instead has left this task to

the manufacturers (Gupte et al. 2011). The manufacturers

provide this information within their manuals and MRI

healthcare professionals are advised to contact the respec-

tive manufacturer to obtain the latest safety information.

Provisional information and guidance to the respective

manufacturer’s websites can be obtained via the website

http://www.mrisaftey.com.

In general, MRI examinations with implanted VNS or

DBS or subdural grid or strip electrodes or depth electrodes

should be performed as follows: magnetic field strength

of 1.5 T or less; head SAR of less than 0.1 W/kg; dB/

dt 20 T/s; output current of the implanted pulse generator

set to 0 mA; testing and reprogramming of the devices after

scanning (Benbadis et al. 2001; Roebling et al. 2009;

Shellock et al. 2006; Shellock 2002; Kainz 2007; Gupte

et al. 2011).

Fig. 2 Reduced susceptibility artifacts of depth electrodes at 1.5 T (b, c) compared with 3 T (a)

Metallic Implants 87](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-90-320.jpg)

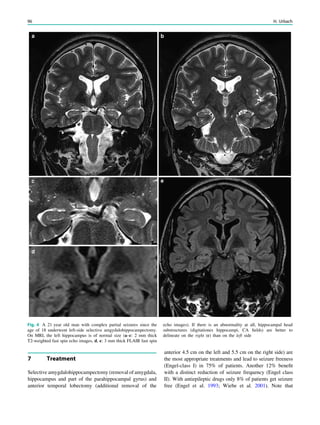

![with familial TLE show hippocampal sclerosis on MRI

(Kobayashi et al. 2002).

If patients develop temporal lobe seizures or subacute

memory deficits after the age of 20, one has to think of

limbic encephalitis, which is mediated via antibodies and

found in up to 30% of patients in this age group (Soeder

et al. 2009).

4 Clinical Presentation

A typical mesial temporal lobe seizure starts with an epi-

gastric aura (definition of aura = initial part of a partial

seizure, that is remembered after the seizure has termi-

nated). The aura is followed by objective phenomena

like staring, restlessness, oroalimentary automatism, and

(ipsilateral) head deviation, which last from around 30

seconds to several minutes. In the postictal phase, gradual

reorientation occurs which may be accompanied by dys-

phasia and other sympoms.

5 Pathology

Hippocampal sclerosis is characterized by neuronal loss and

gliosis, most prominent in the CA1 field of the hippocam-

pus, followed by the hilus, CA3 field, and dentate granule

layer, while the CA2 field is relatively spared. These

alterations are accompanied by a dispersion of the dentate

granuale layer with ectopic neurons being found in the

molecular layer.

Extent of hippocampal sclerosis is graded according to

Wyler et al. (Table 1) or more recently according to Blümcke

et al. (Table 2) (Wyler et al. 1992; Blümcke et al. 2007). Note

that more than 90% of patients, who undergo selective am-

ygdalohippocampectomy with MRI suspected hippocampal

sclerosis have Wyler grade III and IV hippocampal sclerosis.

Both are easily recognized on perfectly angulated high res-

olution T2- and FLAIR images due to their atrophy and

increased signal intensity. In contrast, only a minority of

patients (3–5%) has atypical variants either confined to

the CA1 field or CA4 field (= end folium sclerosis). These

atypical variants do not show significant atrophy and may be

only detected due to a loss of the internal hippocampal

structure (Fig. 1). However, if a hippocampus is normal on

MRI an unrevealing histology is more likely.

6 Imaging

MRI correlate of hippocampal slerosis are atrophy and

increased signal intensity, which are best visualized on

coronal FLAIR and T2-weighted fast spin echo images

angulated perpendicularly to the hippocampal long axis.

Increased signal intensity T2-signal abnormalities appears

to correlate with gliosis and may not be directly related

to the degree of neuronal loss (Briellman et al. 2002).

On FLAIR sequences, contrast to noise ratio (C/N) is higher

Table 1 Neuropathological grading of hippocampal sclerosis [adapted from Wyler et al. (1992)]

Grade Classfication Neuropathological description MRI

Wyler I Mild mesial temporal

damage

Gliosis with slight (10%) or no hippocampal

neuronal dropout involving sectors CA1, CA3,

and/or CA4

Not visible

Wyler II Moderate mesial

temporal damage

Gliosis with moderate (10–50%) neuronal dropout

of CA1, CA3, and/or CA4. If Involvement limited

to CA3 and 4 = end folium sclerosis

Loss of internal structure on high

resolution T2-weighted images

Wyler III ‘‘Classical’’ ammon’s

horn sclerosis

Gliosis with [50% neuronal dropout of CA1, CA3,

and CA4, but sparing CA2

Atrophy and increased T2/FLAIR

signal

Wyler IV ‘‘Total’’ ammon’s

horn sclerosis

Gliosis with [50% neuronal dropout of all sectors Atrophy and increased T2/FLAIR

signal visible

Table 2 Neuropathological grading of hippocampal sclerosis [adapted from Blümcke et al. (2007)]

Grade Description Frequency (%) MRI

Blümcke MTS 1a Severe neuronal loss in CA1,

moderate neuronal loss in other subfields

23 Atrophy and increased T2/FLAIR signal

Blümcke MTS 1b Extensive neuronal loss in all subfields 68 Atrophy and increased T2/FLAIR signal

Blümcke MTS 2 Severe neuronal loss restricted to CA1 7 ?

Blümcke MTS 3 Severe neuronal loss restricted to hilar

region = end folium sclerosis

5 Loss of internal structure on high resolution

T2-weighted images

92 H. Urbach](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-94-320.jpg)

![Table 1 Imaging and genetic classification according to Barkovich [modified from Barkovich et al. (2012), with permission]

Disturbance of neuronal and glial proliferation or apoptosis

1. Congenital microcephaly (premigrational proliferation ;/apoptosis :) (a) Microcephaly with severe intrauterine growth deficiency and short

stature

(b) Microcephaly with variable short stature (severe intrauterine

growth deficiency to mildly short), moderate to severe

(c) Microcephaly with mildly short stature or normal growth, mild to

moderate developmental delay, normal to thin cortex, with or without

simplified gyral pattern, with or without callosal hypogenesis, and

with or without periventricular nodular heterotopia

(d) Microcephaly with mildly short stature or normal growth, severe

developmental delay, variable cortical development with simplified

gyral pattern or cortical dysgenesis, and with or without callosal

hypogenesis

(e) Microcephaly with variable anomalies and less well characterized

syndromes (with or without simplified gyral pattern, with or without

callosal hypogenesis, and with or without cerebellar hypoplasia)

(f) Microcephaly with severe developmental delay and evidence of

degeneration, with or without simplified gyral pattern, with or without

enlarged extra-axial spaces, with or without callosal hypogenesis, and

with or without atypical cortical dysgenesis

(g) Microcephaly with lissencephaly (cortex thick or relatively thick,

smooth gray–white matter border)

(h) Microcephaly with brain volume loss and enlarged ventricles

(hydrocephalus ex vacuo or hydranencephaly), with or without

cortical dysgenesis, and with or without callosal hypogenesis

2. Megalencephaly (a) Megalencephaly with normal cortex (or presumed normal cortex)

(b) Megalencephaly with periventricular nodular heterotopia

(c) Megalencephaly with polymicrogyria and other cortical

dysgenesis

3. Malformations due to abnormal cell proliferation (a) Cortical hamartomas of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)

(b) Focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) with balloon cells

(c) Hemimegalencephaly

Disturbance of neuronal migration

1. Malformations with neuroependymal abnormalities: Periventricular

heterotopia

(a) Anterior predominant and diffuse periventricular nodular

heterotopia

(b) Posterior predominant (temporal-trigonal or infrasylvian)

periventricular nodular heterotopia

(c) Periventricular heterotopia, not nodular (uni- or bilateral)

2. Malformations due to generalized abnormal transmantle migration

(radial and nonradial)

(a) Anterior predominant or diffuse classic (four-layered)

lissencephaly and subcortical band heterotopia

(b) Posterior predominant or diffuse classic (four-layered) and two-

layered (without cell sparse zone) lissencephaly and subcortical band

heterotopia

(c) X-linked lissencephaly (three-layered, without cell sparse zone)

with callosal agenesis, ambiguous genitalia

(d) Reelin-type lissencephaly (inverted cortical lamination, without

cell sparse zone)

(e) Variant lissencephaly

3. Malformations presumably due to localized abnormal late radial or

tangential transmantle migration

(a) Subcortical heterotopia (clinically defined with unknown cause)

(b) Sublobar dysplasia (clinically defined with unknown cause)

4. Malformations due to abnormal terminal migration and defects in

pial limiting membrane

(a) Dystroglycan-laminin complex abnormalities with cobblestone

malformation complex, with or without congenital muscular

dystrophy (Walker–Warburg syndrome, muscle–eye–brain disease,

Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy, congenital muscular

dystrophy with cerebellar hypoplasia)

(b) Cobblestone malformations in congenital disorders of

glycolysation

(c) Cobblestone malformations with no known glycolysation defect

(d) Other syndromes with cortical dysgenesis and marginal

glioneuronal heterotopia, but with normal cell types

(continued)

Malformations of Cortical Development 127](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-128-320.jpg)

![Table 1 (continued)

Disturbance of neuronal and glial proliferation or apoptosis

Disturbance of cortical organization

1. Malformations with polymicrogyria or cortical malformations

resembling polymicrogyria

(a) Polymicrogyria with transmantle clefts (schizencephaly) or

calcification

(b) Polymicrogyria without transmantle clefts or calcification,

classified by location

(c) Syndromes with polymicrogyria

2. Cortical dysgenesis secondary to inborn errors of metabolism (a) Mitochondrial and pyruvate metabolic disorders

(b) Peroxisomal disorders

3. Focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) without dysmorphic neurons, due to

late developmental disturbances

4. Postmigrational developmental microcephaly (birth occipito-

frontal diameter (OFD)—3 SD or lower, later OFD-4 SD, no evidence

of brain injury)

Classification considers normal cortical development as separated into three overlapping steps and distinguishes malformations caused by

disturbed neuronal/glial proliferation and apoptosis (Step 1), neuronal migration (Step 2), and cortical organization (Step 3). The classification

scheme has been continuously updated, incorporating new genetic findings, and is considered to be a framework but not a finalized classification

(Barkovich et al. 1996, 2001, 2005, 2012)

Table 2 Neuropathologic classification according to Palmini and Lüders and Blümcke et al. [adapted from Palmini and Lüders (2002), Palmini

et al. (2004), and Blümcke et al. (2011)]

Palmini type Blümcke type Neuropathological

description

MRI

Mild malformations of cortical

development type 1 = ectopic neurons

in or adjacent to cortical layer 1

Molecular layer

neurons

Persistent subpial

granular layer

Marginal

glioneuronal

heterotopia

Normal

Mild malformations of cortical

development type 2 = neuronal

heterotopia outside layer 1

Small aggregates of

heterotopic white

matter neurons

Dysgenesis of the

hippocampal

formation

Normal

or

Gray–white matter demarcation

loss

FCD type 1A, 1B = cytoarchitectural

abnormalities without dysmorphic

neurons or balloon cells

FCD type 1a

FCD type 1b

FCD type 1c

A: dyslamination

only

B: dyslamination and

hypertrophic or

immature neurons

a: microcolumnar

(vertical)

dyslamination

b: radial

dyslamination

c: vertical and radial

dyslamination

Normal (1/3 of cases)

or

Gray–white matter demarcation

loss

FCD type 2A, 2B = cytoarchitectural

abnormalities with dysmorphic neurons

or balloon cells

FCD type 2A,

2B = cytoarchitectural

abnormalities with dysmorphic

neurons or balloon cells

A: dysmorphic

neurons

B: dysmorphic

neurons and balloon

cells

A: cortical thickening, abnormal

depth of sulcus

B: cortical thickening, abnormal

depth of sulcus, subcortical

funnel-shaped hyperintensity

Classification considers histopathological cell types and cortical lamination. It distinguishes normal neurons in an abnormal location and

distribution; hypertrophic, immature, and dysplastic neurons; as well as balloon cells. Recent ILAE classification introduces a Focal cortical

dysplasia (FCD) type III, in which mild and FCD type I malformations are associated with hippocampal sclerosis (FCD IIIa), tumors (FCD IIIb),

vascular malformations (FCD IIIc), or other principal lesions acquired during early life (FCD IIId)

128 H. Urbach and S. Greschus](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-129-320.jpg)

![In SBH, the brain surface appears superficially normal,

except that the sulci between gyri are shallow, and the

cortex is normal and not thick (Barkovich et al. 1994;

Dobyns et al. 1996). Just beneath the cortex, often separated

from it by just a few millimeters of white matter, lies a

smooth band of neurons that never reached the true cortex.

This band has a variable thickness and thin bands are easily

overlooked but highlighted by voxel-based morphometric

analysis (Fig. 7) (Huppertz et al. 2008).

The spectrum of LIS and SBH varies from complete or

nearly complete absence of cerebral convolutions or agyria

(grades 1 and 2) to abnormally wide convolutions or

pachygyria (grade 4) to normal convolutions separated by

shallow sulci overlying SBH (grade 6). Intermediate grades

consist of mixed agyria–pachygyria (grade 3) and mixed

pachygyria–SBH (grade 5) (Dobyns 2010).

Paucity of cerebral gyri often shows a gradient, which is

useful in determining the most likely genetic cause. If lis-

sencephaly and SBH are pronounced in the anterior frontal

lobes, a DCX mutation should be considered. More severe

changes in the parietal and occipital lobes point to LIS1 or

TUB1A mutations. Lissencephaly with cerebellar hypopla-

sia point to RELN and VLDLR mutations, if pronounced in

the frontal lobes, and to TUB1A mutations, if pronounced in

the posterior frontal lobes, perisylvian, or parietal and

occipital lobes, repectively. Lissencephaly with corpus

callosum agenesis point to ARX mutations if agyria or

pachygyria is pronounced in the temporal and posterior

brain regions.

Most lissencephalies have a genetic cause, however,

periventricular and subcortical calcifications suggest an

infectious (particularly CMV) cause (Figs. 5-7).

3 Cobblestone Lissencephaly, Congenital

Muscular Dystrophies

3.1 Definition

Congenital muscular dystrophy syndromes or so-called

dystroglycanopathies represent a heterogeneous group of

congenital diseases affecting the muscles and frequently the

brain and eyes, which are characterized by defective protein

glycolization. Protein glycolization is a complex mechanism,

in which sugars (glycans) are attached to proteins modulating

their stability, conformity, and function (Barkovich et al.

2005). For example, in the developing brain radial glial cells

have end feet attached to the pial basement membrane, and

defective basement membrane formation results in cobble-

stone lissencephaly with neurons migrating too far (e.g.,

neurons destinated for cortex layers II and III migrate and

populate the marginal zone) (Clement et al. 2008).

The clinical spectrum comprises severe [Walker–Warburg

syndrome (WWS), Fukuyama congenital muscular dystro-

phy, muscle–eye–brain disease] and milder forms with or

without brain involvement (congenital muscular dystrophy

CMD, merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy,

merosin-positive congenital muscular dystrophy C1C,

merosin-positive congenital muscular dystrophy C1D, limb

girdle muscular dystrophies LGMD2I, LGMD2K, LGMD2L,

LGMD2M). Several mutations in genes encoding for proteins

of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex have been found

(protein-O-mannosyl transferase 1 POMT1, OMIM 607423;

protein-O-mannosyl transferase 2 POMT2, OMIM 607439;

protein-O-mannose 1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase1

Fig. 5 Type I lissencephaly with ‘‘posterior’’ accentuation suggesting a LIS1 gene mutation. This 17 months year old girl showed global

developmental delay and suffered from generalized seizures since the age of 8 months

134 H. Urbach and S. Greschus](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-135-320.jpg)

![spectroscopic study of epileptogenic hypothalamic hamartomas:

analysis of 72 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 25:450–462

Friede R (1989) Developmental neuropathology, 2nd edn. Springer,

Berlin

Garavelli L, Guareschi E, Errico S, Simoni A, Bergonzini P, Zollino M,

Gurrieri F, Mancini GM, Schot R, Van Der Spek PJ, Frigieri G,

Zonari P, Albertini E, Giustina ED, Amarri S, Banchini G,

Dobyns WB, Neri G (2007) Megalencephaly and perisylvian

polymicrogyria with postaxial polydactyly and hydrocephalus

[MPPH]: report of a new case. Neuropediatrics 38:200–203

Garbelli R, Milesi G, Medici V, Villani F, Didato G, Deleo F,

D’Incerti L, Morbin M, Mazzoleni G, Giovagnoli AR, Parente A,

Zucca I, Mastropietro A, Spreafico R (2012) Blurring in patients

with temporal lobe epilepsy: clinical, high-field imaging and

ultrastructural study. Brain, Aug 135(Pt 8):2337–2349

Giordano L, Vignoli A, Pinelli L, Brancati F, Accorsi P, Faravelli F,

Gasparotti R, Granata T, Giaccone G, Inverardi F, Frassoni C,

Dallapiccola B, Valente EM, Spreafico R (2009) Joubert syndrome

with bilateral polymicrogyria: clinical and neuropathological

findings in two brothers. Am J Med Genet A 149A:1511–1515

Gripp KW, Hopkins E, Vinkler C, Lev D, Malinger G, Lerman-Sagie T,

Dobyns WB (2009) Significant overlap and possible identity of

macrocephaly capillary malformation and megalencephaly poly-

microgyria-polydactyly hydrocephalus syndromes. Am J Med Genet

A 149A:868–876

Guerrini R, Dobyns WB (1998) Bilateral periventricular nodular

heterotopia with mental retardation and frontonasal malformation.

Neurology 51(2):499–503

Hayashi N, Tsutsumi Y, Barkovich AJ (2002) Polymicrogyria without

porencephaly/schizencephaly. MRI analysis of the spectrum and

the prevalence of macroscopic findings in the clinical population.

Neuroradiology 44(8):647–655

Hermier M, Montavont A, Dupuis-Girod S, Cho TH, Honnorat J,

Plauchu H (2010) Polymicrogyria: an underrecognized cause of

epilepsy in in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

(Rendu-Osler disease). Epilepsia 51(Suppl 4):1–189

Hevner RF (2005) The cerebral cortex malformation in thanatophoric

dysplasia: neuropathology and pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol

110(3):208–221

Hildebrandt M, Pieper T, Winkler P, Kolodziejczyk D, Holthausen H,

Blümcke I (2005) Neuropathological spectrum of cortical dysplasia

in children with severe focal epilepsies. Acta Neuropathol

110(1):1–11

Hoyt CS, Billson F, Ouvrier R, Wise G (1978) Ocular features of

Aicardi’s syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 96:291–295

Huppertz HJ, Wellmer J, Staack AM, Altenmüller DM, Urbach H,

Kröll J (2008) Voxel-based 3-D MRI analysis helps to detect subtle

forms of subcortical band heterotopia. Epilepsia 49(5):772–785

Jackson AP (2002) Identification of microcephalin, a protein impli-

cated in determining the size of the human brain. Am J Hum Genet

71(1):136–142

Jansen A, Andermann E (2005) Genetics of the polymicrogyria

syndromes. J Med Genet 42(5):369–378

Jissendi-Tchofo P, Kara S, Barkovich AJ (2009) Midbrain–hindbrain

involvement in lissencephalies. Neurology 72(5):410–418

Kallmann FT, Schoenfeld WA, Barrera SE (1944) The genetics aspects

of primary eunuchoidism. Am J Mental Deficits 48:203–208

Kirschstein T, Fernandez G, Grunwald T, Pezer N, Urbach H,

Blümcke I, Van Roost D, Lehnertz K, Elger CE (2003) Heterot-

opias, cortical dysplasias and glioneural tumors participate in

cognitive processing in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.

Neurosci Lett 338:237–241

Knorr JR, Ragland RL, Brown RS, Gelber N (1993) Kallmann

syndrome: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 14(4):845–851

Krsek P, Maton B, Korman B, Pacheco-Jacome E, Jayakar P, Dunoyer C,

Rey G, Morrison G, Ragheb J, Vinters HV, Resnick T, Duchowny M

(2008) Different features of histopathological subtypes of pediatric

focal cortical dysplasia. Ann Neurol 63(6):758–769

Krsek P, Pieper T, Karlmeier A, Hildebrandt M, Kolodziejczyk D,

Winkler P, Pauli E, Blümcke I, Holthausen H (2009a) Different

presurgical characteristics and seizure outcomes in children with

focal cortical dysplasia type I or II. Epilepsia 50(1):125–137

Krsek P, Maton B, Jayakar P, Dean P, Korman B, Rey G, Dunoyer C,

Pacheco-Jacome E, Morrison G, Ragheb J, Vinters HV, Resnick T,

Duchowny M (2009b) Incomplete resection of focal cortical

dysplasia is the main predictor of poor postsurgical outcome.

Neurology 72(3):217–223

Kuzniecky R, Andermann F, Guerrini R (1993) Congenital bilateral

perisylvian syndrome: study of 31 patients. The congenital bilateral

perisylvian syndrome multicenter collaborative study. Lancet

341:608–612

Lerner JT, Salamon N, Hauptman JS, Velasco TR, Hemb M, Wu JY,

Sankar R, Donald Shields W, Engel J Jr, Fried I, Cepeda C,

Andre VM, Levine MS, Miyata H, Yong WH, Vinters HV,

Mathern GW (2009) Assessment of surgical outcomes for mild

type I and severe type II cortical dysplasia: a critical review and the

UCLA experience. Epilepsia 50:1310–1335

Leventer RJ, Jansen A, Pilz DT, Stoodley N, Marini C, Dubeau F,

Malone J, Mitchell LA, Mandelstam S, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF,

Andermann F, Andermann E, Guerrini R, Dobyns WB (2010)

Clinical and imaging heterogeneity of polymicrogyria: a study of

328 patients. Brain 133:1415–1427

Lewis AJ, Simon EM, Barkovich AJ, Clegg NJ, Delgado MR,

Levey E, Hahn JS (2002) Middle interhemispheric variant of

holoprosencephaly: a distinct cliniconeuroradiologic subtype.

Neurology 59(12):1860–1865.

Matsunaga E, Shiota K (1977) Holoprosencephaly in human embryos:

epidemiologic studies of 150 cases. Teratology 16:261–272

Miller SP, Shevell MI, Patenaude Y, Poulin C, O’Gorman AM (2000)

Septo-optic dysplasia plus: a spectrum of malformations of cortical

development. Neurology 54:1701–1703

Moog U, De Die-Smulders CE, Schrander-Stumpel CT, Engelen JJ,

Hamers AJ, Frints S, Fryns JP (2001) Holoprosencephaly: the

Maastricht experience. Genet Couns 12(3):287–298

Oba H, Barkovich AJ (1995) Holoprosencephaly: an analysis of

callosal formation and its relation to development of the inter-

hemispheric fissure. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 16:453–460

Palm L, Hägerstrand I, Kristoffersson U, Blennow G, Brun A, Jörgensen

C (1986) Nephrosis and disturbances of neuronal migration in male

siblings–a new hereditary disorder? Arch Dis Child 61(6):545–548

Palmini A, Lüders H (2002) Classification issues in malformations

caused by abnormalities of cortical development. Neurosurg Clin N

Am 13:1–16

Palmini A, Najm I, Avanzini G, Babb T, Guerrini R, Foldvary-

Schaefer N, Jackson G, Lüders HO, Prayson R, Spreafico R,

Vinters HV (2004) Terminology and classification of the cortical

dysplasias. Neurology 62(6 Suppl 3):S2–S8. Review

Pattison L, Crow YJ, Deeble VJ, Jackson AP, Jafri H, Rashid Y,

Roberts E, Woods CG (2000) A fifth locus for primary autosomal

recessive microcephaly maps to chromosome 1q31. Am J Hum

Genet 67:1578–1580

Pilz DT, Matsumoto N, Minnerath S, Mills P, Gleeson JG, Allen KM,

Walsh CA, Barkovich AJ, Dobyns WB, Ledbetter DH, Ross ME

(1998) LISI and XLIS (DCX) mutations cause most classical

lissencephaly, but different patterns of malformation. Hum Mol

Genet 7:2029–2037

Pilz DT, Kuc J, Matsumoto N, Bodurtha J, Bernadi B, Tassinari CA,

Dobyns WB, Ledbetter DH (1999) Subcortical band heterotopia in

162 H. Urbach and S. Greschus](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-163-320.jpg)

![Chiang KL, Chang KP, Wong TT, Hsu TR (2009) Linear scleroderma

‘‘en coup de sabre’’: initial presentation as intractable partial

seizures in a child. Pediatr Neonatol 50(6):294–298

Claeys KG, Claes LR, Van Goethem JW et al (2007) Epilepsy and

migraine in a patient with Urbach–Wiethe disease. Seizure

16:465–468

Cohen MM Jr, Hayden PW (1979) A newly recognized hamartom-

atous syndrome. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser 15:291–296

Dietrich RB, Glidden DE, Roth GM et al (1998) The Proteus

syndrome: CNS manifestations. Am J Neuroradiol 19(5):987–990

Enjoltas O, Riche MC, Merland JJ (1985) Facial port-wine stains and

Sturge–Weber syndrome. Pediatrics 76:48–51

Gill DS (2006) Age-related findings on MRI in neurofibromatosis type

1. Pediatr Radiol 36:1048–1056

Gonçalves FG, de Melo MB, de L Matos V et al (2010) Amygdalae

and striatum calcification in lipoid proteinosis. Am J Neuroradiol

31(1):88–90

Gorlin RJ, Cohen MM, Hennekam RCM (2001) Syndromes of the

Head and Neck, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, New York,

pp 484–488

Greene AK, Rogers GF, Mulliken JB (2007) Schimmelpenning

syndrome: an association with vascular anomalies. Cleft Palate

Craniofac J 44:208–215

Happle R (2010) The group of epidermal nevus syndromes. Part I.

Well defined phenotypes. J Am Acad Dermatol 63(1):1–22

Hennel SJ, Ekert PG, Volpe JJ, Inder TE (2003) Insights into the

pathogenesis of cerebral lesions in incontinentia pigmenti. Pediatr

Neurol 29(2):148–150

Hornstein OP, Knickenberg M (1974) Zur Kenntnis des Schimmel-

penning-Feuerstein-Mims-Syndroms (Organoide Naevus-Phako-

matose) [in German]. Arch Derm Forsch 250:33–50

Hsieh DT, Chang T (2011) Incontinentia pigmenti: skin and magnetic

resonance imaging findings. Arch Neurol 68(8):1080

Hubert JN, Callen JP (2002) Incontinentia pigmenti presenting as

seizures. Pediatr Dermatol 19(6):550–552

Ito M (1952) Studies of melanin: XI. Incontinentia pigmenti achrom-

iens. Tohoku J Exp Med 55(suppl):55–57

Jallo GI, Kothbauer K, Mehta V et al (2005) Meningioangiomatosis

without neurofibromatosis: a clinical analysis. J Neurosurg 103(4

Suppl):319–324

Krueger DA, Care MM, Holland K et al (2010) Everolimus for

subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis.

N Engl J Med 363(19):1801–1811

Longo D, Paonessa A, Specchio N et al (2011) Parry–Romberg

syndrome and Rasmussen encephalitis: possible association. Clin-

ical and neuroimaging features. J Neuroimaging 21(2):188–193

McCall S, Ramzy MI, Cure JK, Pai GS (1992) Encephalocraniocu-

taneous lipomatosis and the Proteus syndrome: distinct entities

with overlapping manifestations. Am J Med Genet 43:662–668

Meuwissen ME, Mancini GM (2012) Neurological findings in

incontinentia pigmenti; a review. Eur J Med Genet 55(5):323–331

NIH Consensus Development Conference (1988) Neurofibromatosis:

conference statement. Arch Neurol 45:575–578

Osborne JP, Fryer A, Webb D (1991) Epidemiology of tuberous

sclerosis. Ann NY Acad Sci 615:125–127

Pascual-Castroviejo I, Roche MC, Martinez Fernández V et al (1994)

Incontinentia pigmenti: MR demonstration of brain changes. Am J

Neuroradiol 15(8):1521–1527

Pavone L, Curatolo P, Rizzo R et al (1991) Epidermal nevus

syndrome: a neurologic variant with hemimegalencephaly, gyral

malformation, mental retardation, seizures, and facial hemihyper-

trophy. Neurology 41:266–271

Roach ES, Gomez MR, Northrup H (1998) Tuberous Sclerosis

Complex Consensus Conference: revised clinical diagnostic crite-

ria. J Child Neurol 13:624–628

Sapp JC, Turner JT, van de Kamp JM et al (2007) Newly delineated

syndrome of congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malfor-

mations, and epidermal nevi (CLOVE syndrome) in seven patients.

Am J Med Genet 143A:2944–2958

Seifert F, Bien CG, Schellinger PD et al (2011) Parry–Romberg

syndrome with chronic focal encephalitis: two cases. Clin Neurol

Neurosurg 113(2):170–172

Sugarman JL (2007) Epidermal nevus syndromes. Semin Cutan Med

Surg 26(4):221–230

Turner JT, Cohen MM, Biesecker LG (2004) Reassessment of the

Proteus syndrome literature: application of diagnostic criteria to

published cases. Am J Med Genet 130A:111–122

Urbach E, Wiethe C (1929) Lipoidosis cutis et mucosae. Virch Arch

Pathol Anat 273:285–319

Wiedemann HR, Burgio GR, Aldenhoff P et al (1983) The Proteus

syndrome. Partial gigantism of the hands and/or feet, nevi,

hemihypertrophy, subcutaneous tumors, macrocephaly or other

skull anomalies and possible accelerated growth and visceral

affections. Eur J Pediatr 140(1):5–12

Wolf NI, Krämer N, Harting I et al (2005) Diffuse cortical necrosis in a

neonate with incontinentia pigmenti and an encephalitis-like

presentation. Am J Neuroradiol 26:1580–1582

176 H. Urbach](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/epilepsymri-140818120139-phpapp02/85/Epilepsy-mri-176-320.jpg)

![Cognard C, Gobin YP, Pierot L, Bailly AL, Houdart E, Casasco A,

Chiras J, Merland JJ (1995) Cerebral dural arteriovenous fistulas:

clinical and angiographic correlation with a revised classification

of venous drainage. Radiology 194:671–680

da Costa L, Thines L, Dehdashti AR, Wallace MC, Willinsky RA,

Tymianski M, Schwartz ML, ter Brugge KG (2009) Management

and clinical outcome of posterior fossa arteriovenous malforma-

tions: report on a single-centre 15-year experience. J Neurol

Neurosurg Psychiatry 80(4):376–379

Del Curling O Jr, Kelly DL Jr, Elster AD, Craven TE (1991) An

analysis of the natural history of cavernous angiomas. J Neurosurg

75:702–708

Englot DJ, Han SJ, Lawton MT, Chang EF (2011) Predictors of

seizure freedom in the surgical treatment of supratentorial cavern-

ous malformations. J Neurosurg 115(6):1169–1174

Fierstra J, Conklin J, Krings T, Slessarev M, Han JS, Fisher JA,

Terbrugge K, Wallace MC, Tymianski M, Mikulis DJ (2011)

Impaired peri-nidal cerebrovascular reserve in seizure patients with

brain arteriovenous malformations. Brain 134(Pt 1):100–109

Flacke S, Stuer C, Stoffel M, Urbach H (2006) Symptomatic

developmental venous anomaly after spontaneous thrombosis of

the collector vein. Clin Neuroradiol 16:131–133

Garcin B, Houdart E, Porcher R, Manchon E, Saint-Maurice JP, Bresson

D, Stapf C (2012) Epileptic seizures at initial presentation in

patients with brain arteriovenous malformation. Neurology 78(9):

626–631

Gross BA, Lin N, Du R, Day AL (2011) The natural history of

intracranial cavernous malformations. Neurosurg Focus 30(6):E24

Hadizadeh DR, Kukuk GM, Steck DT, Gieseke J, Urbach H,

Tschampa HJ, Greschus S, Kovàcs A, Möhlenbruch M, Bostroem

A, Schild HH, Willinek WA (2012) Noninvasive evaluation of

cerebral arteriovenous malformations by 4D-MRA for preoperative

planning and postoperative follow-up in 56 patients: comparison

with DSA and intraoperative findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol

33(6):1095–1101

Hon JM, Bhattacharya JJ, Counsell CE, Papanastassiou V, Ritchie V,

Roberts RC, Sellar RJ, Warlow CP, Al-Shahi Salman R (2009)

SIVMS Collaborators. The presentation and clinical course of

intracranial developmental venous anomalies in adults: a system-

atic review and prospective, population-based study. Stroke

40(6):1980–1985

Josephson CB, Leach JP, Duncan R, Roberts RC, Counsell CE, Al-

Shahi Salman R (2011) Scottish Audit of Intracranial Vascular

Malformations (SAIVMs) Steering committee and collaborators.

Seizure risk from cavernous or arteriovenous malformations:

prospective population-based study. Neurology 76(18):1548–1554

Josephson CB, Bhattacharya JJ, Counsell CE, Papanastassiou V,

Ritchie V, Roberts R, Sellar R, Warlow CP, Al-Shahi Salman R

(2012) On behalf of the Scottish Audit of Intracranial Vascular

Malformations (SAIVMs) steering committee and collaborators.

Seizure risk with AVM treatment or conservative management: