This document provides an introduction to the Encyclopedia of Human Resources Information Systems: Challenges in e-HRM. It is edited by Teresa Torres-Coronas and Mario Arias-Oliva and published by IGI Global. The encyclopedia rigorously analyzes key critical HR variables and defines previously undiscovered issues in the HR field. It contains contributions from over 150 authors from around the world on topics related to personnel management, information storage and retrieval systems, management information systems, and the management of knowledge workers.

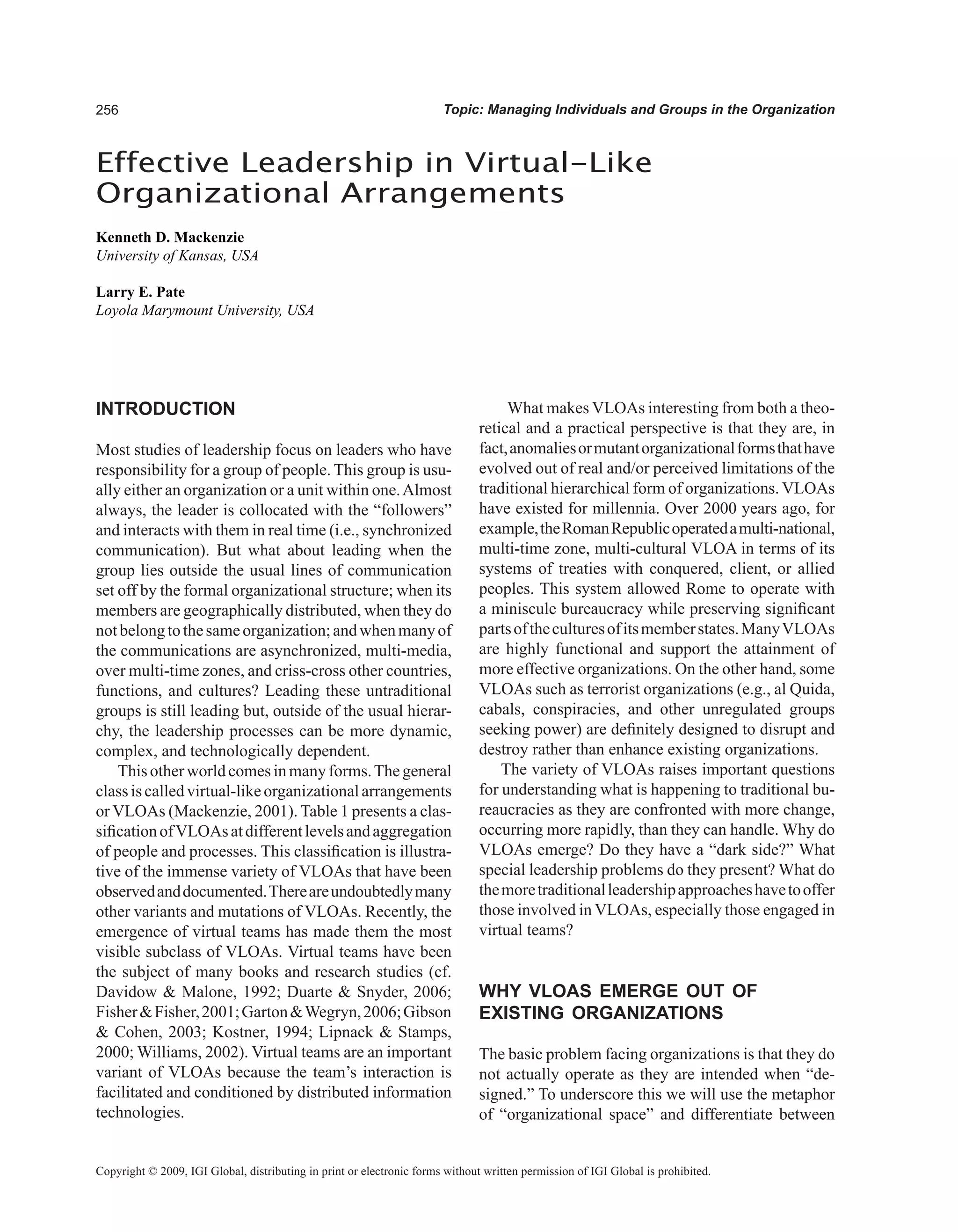

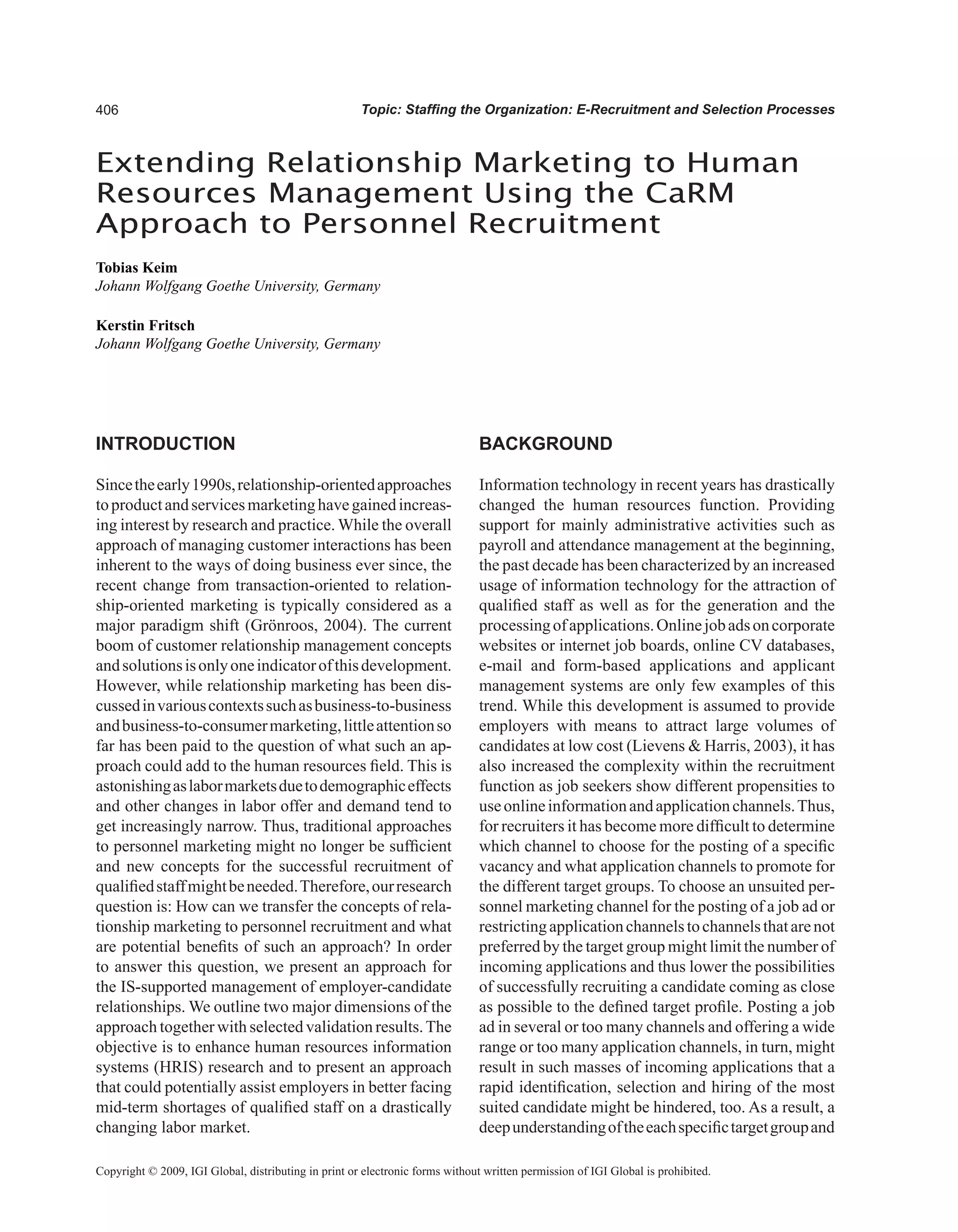

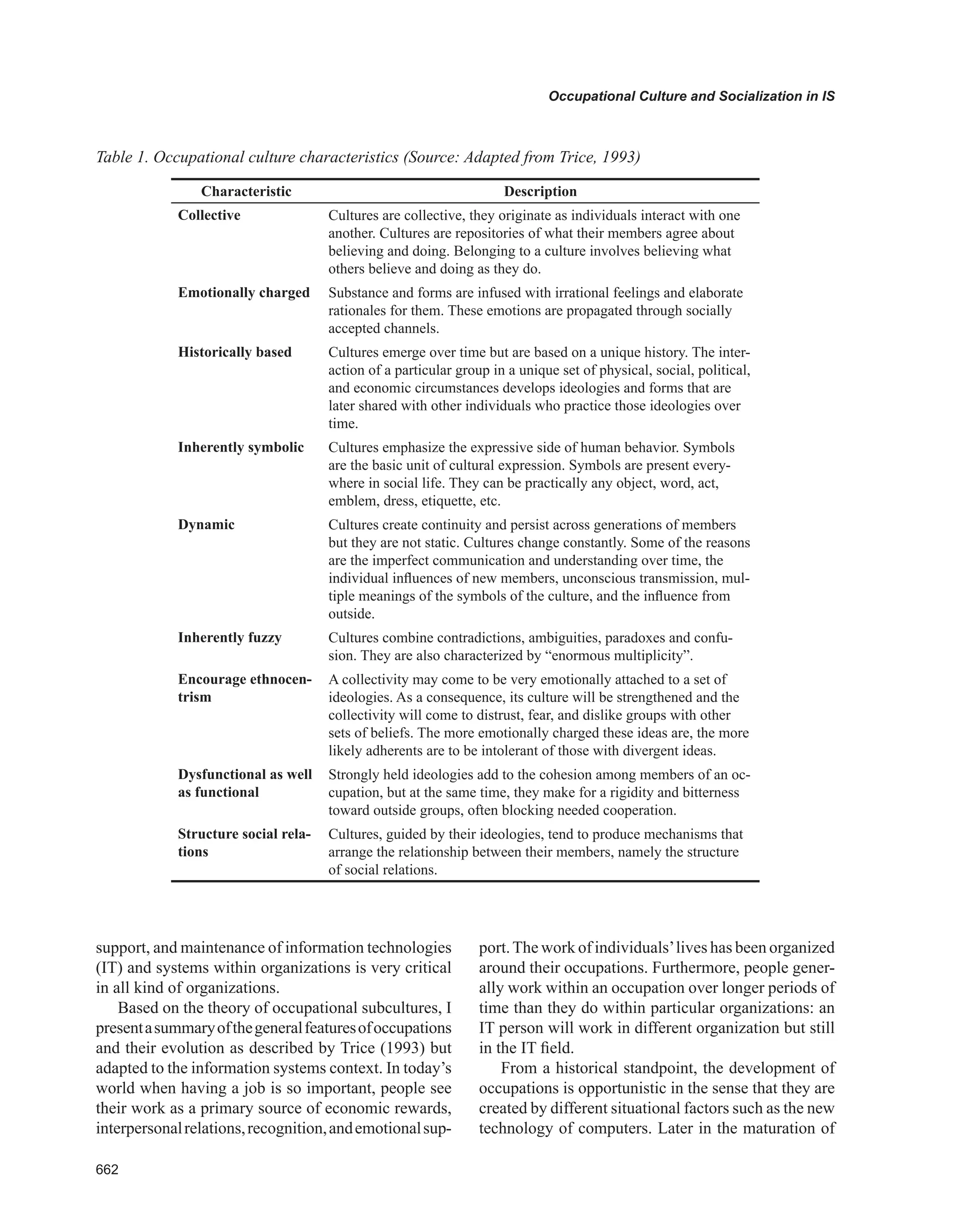

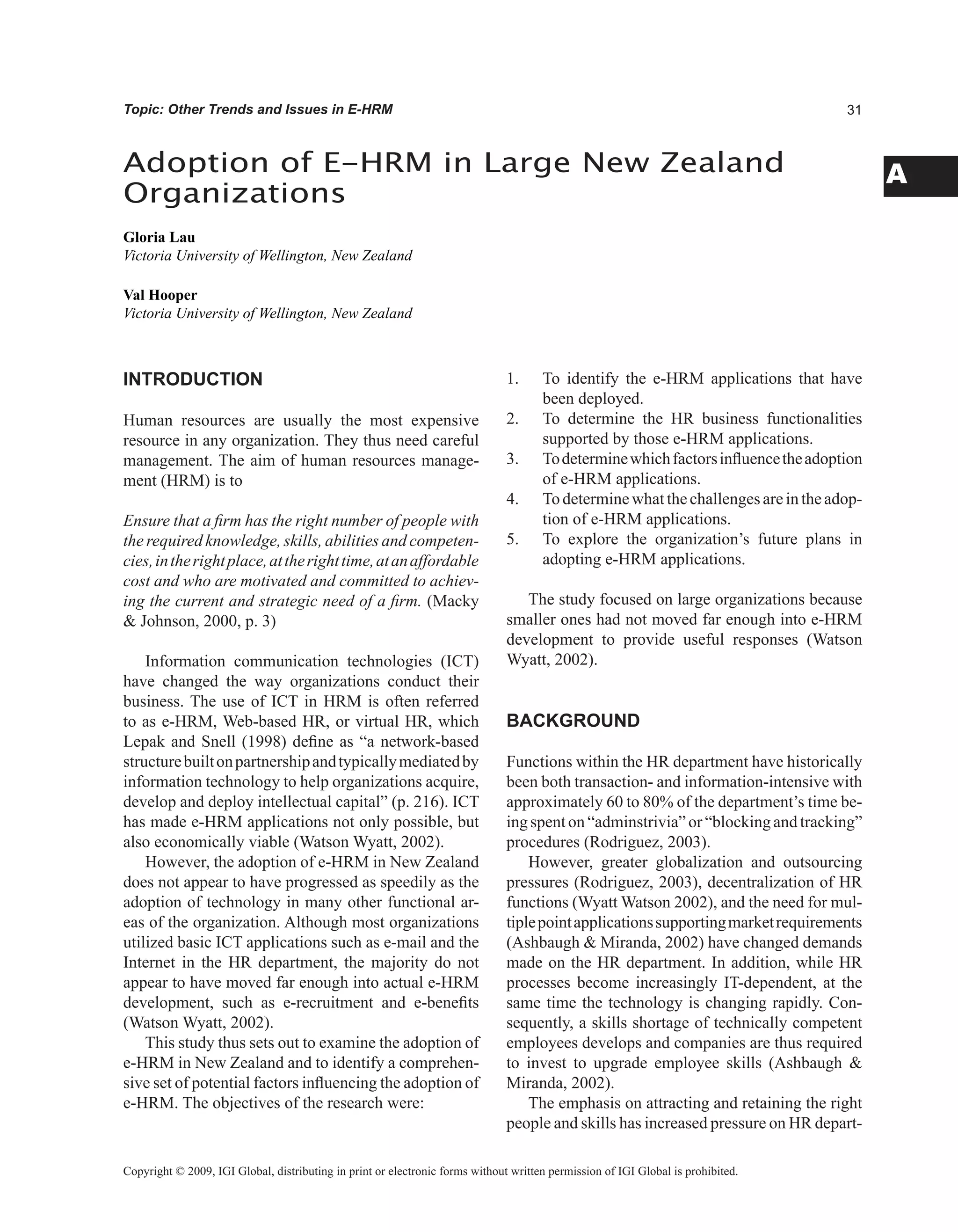

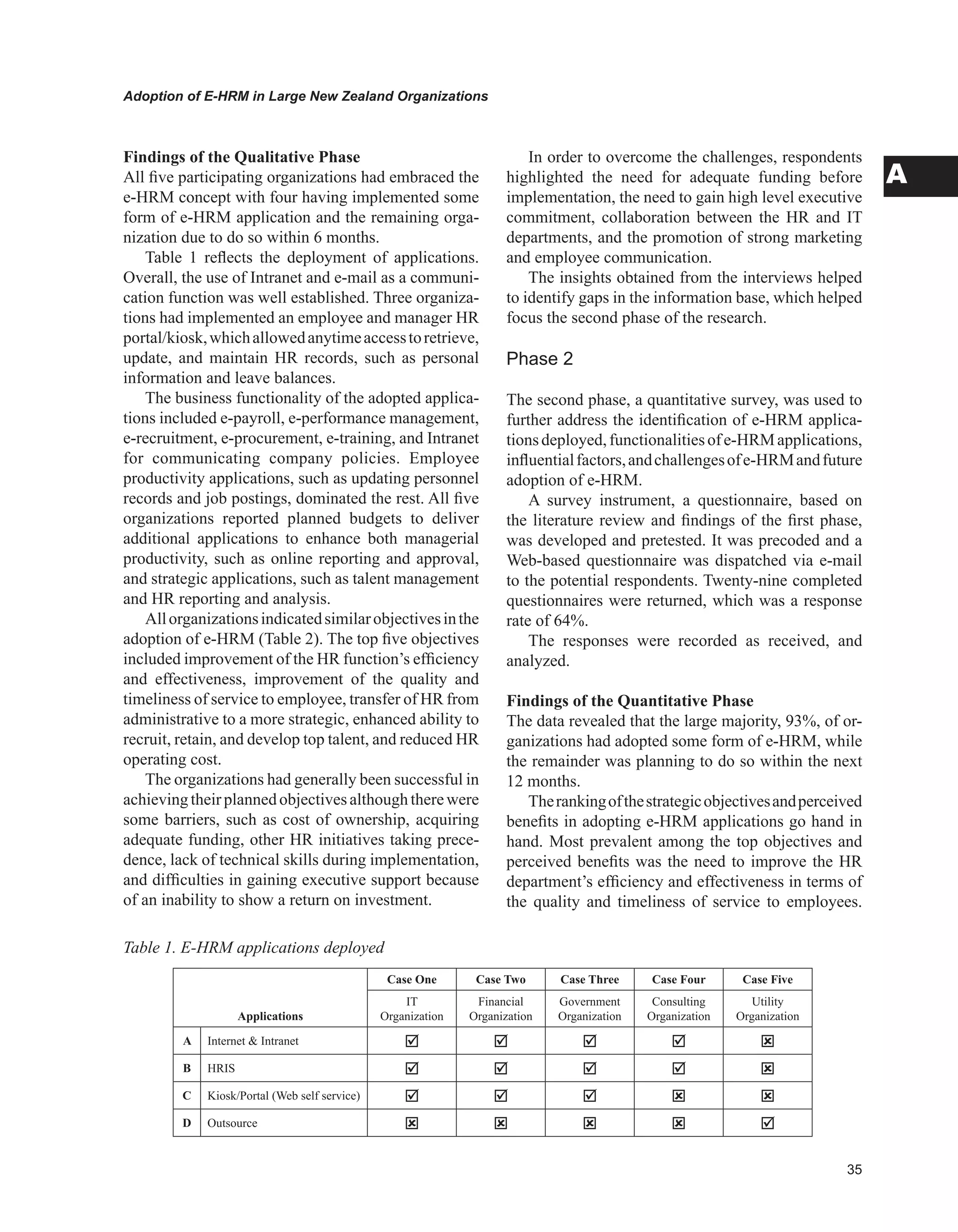

![A

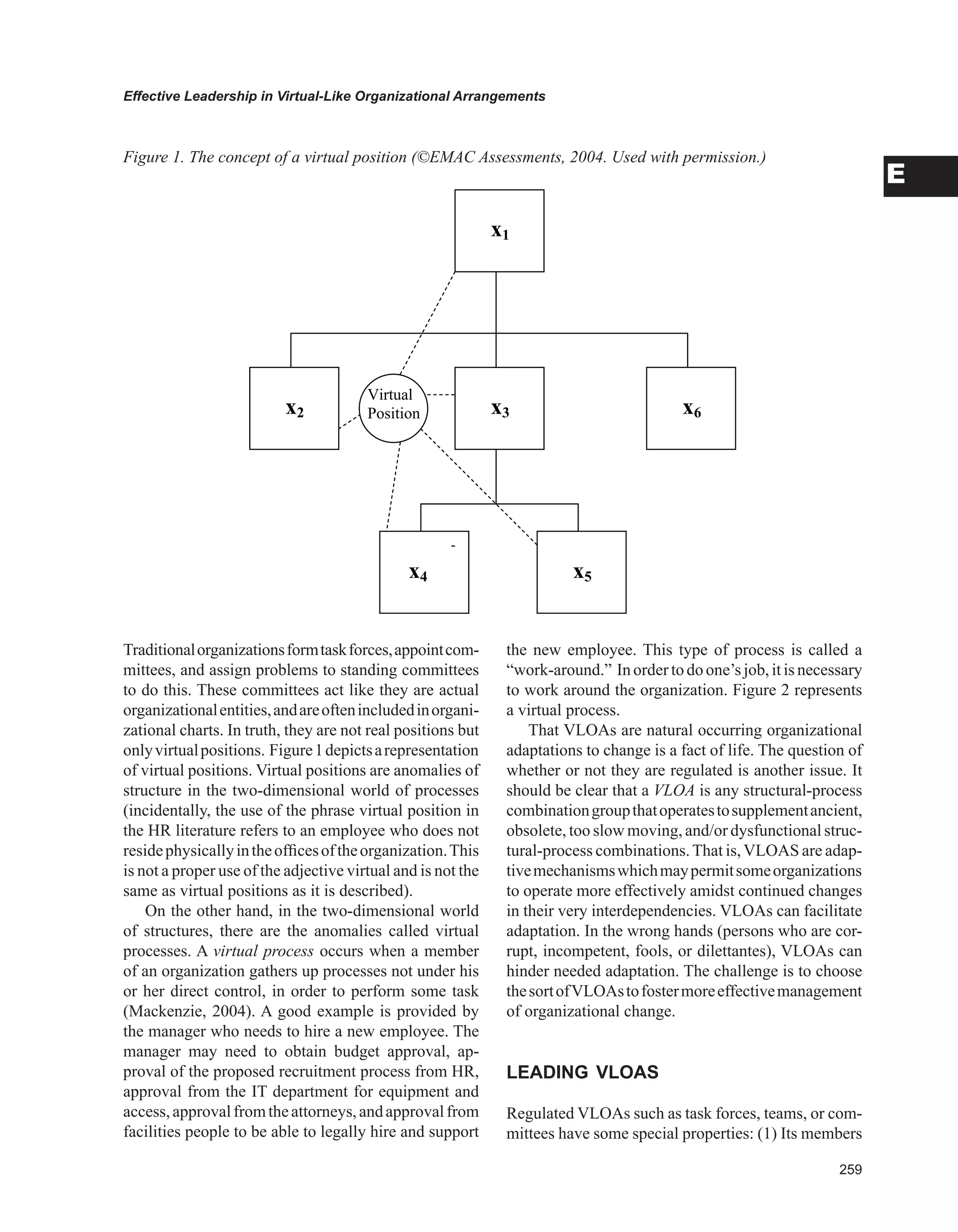

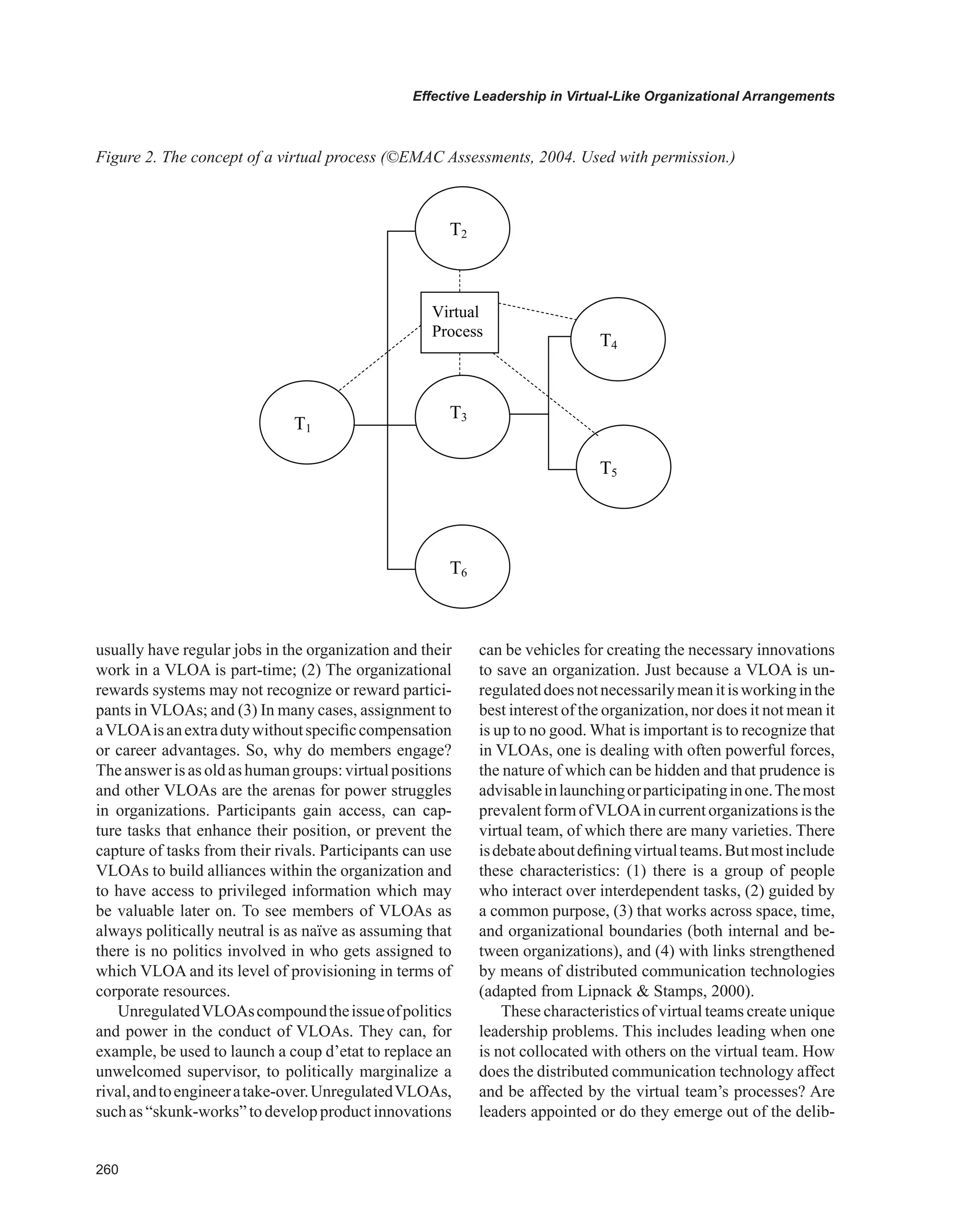

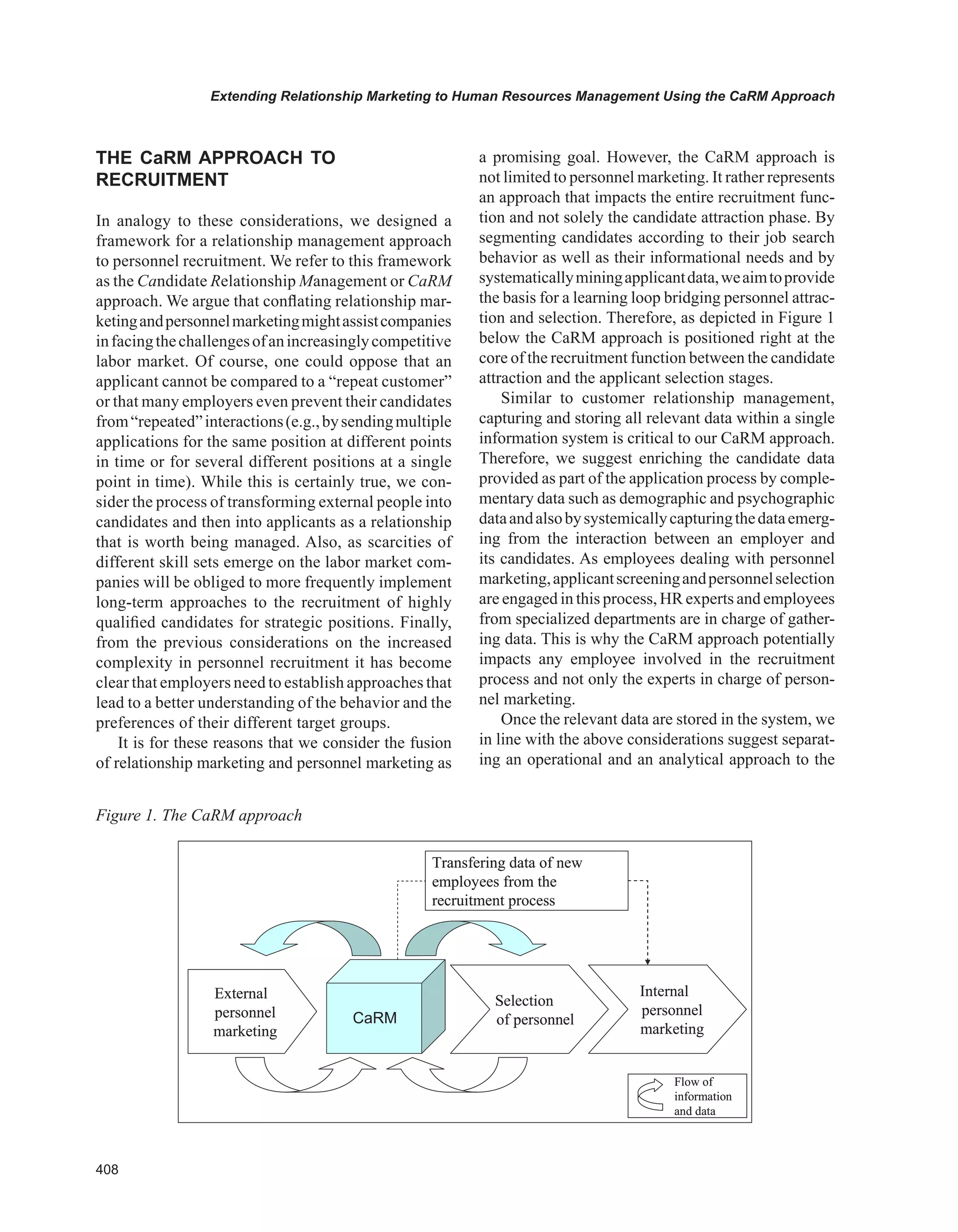

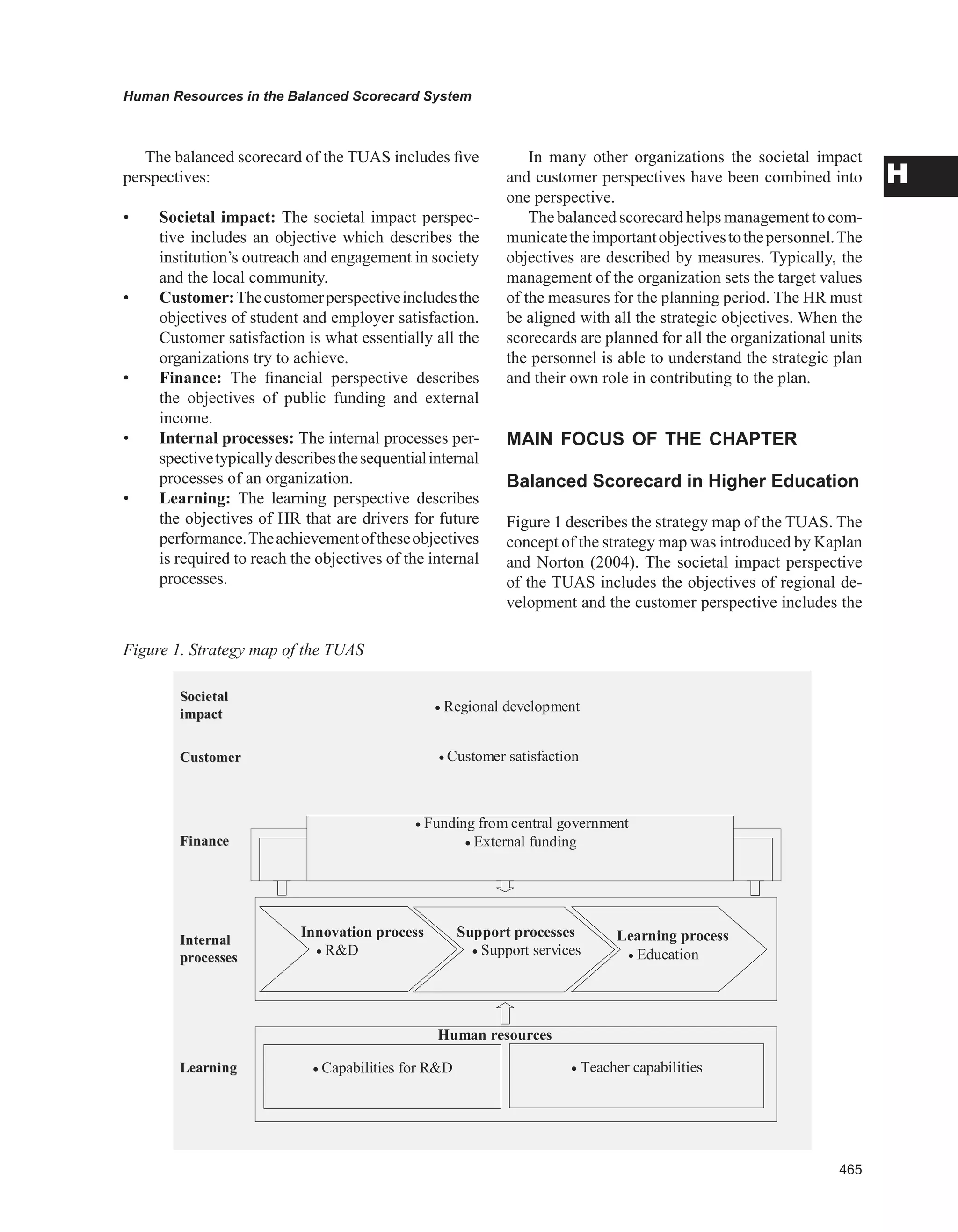

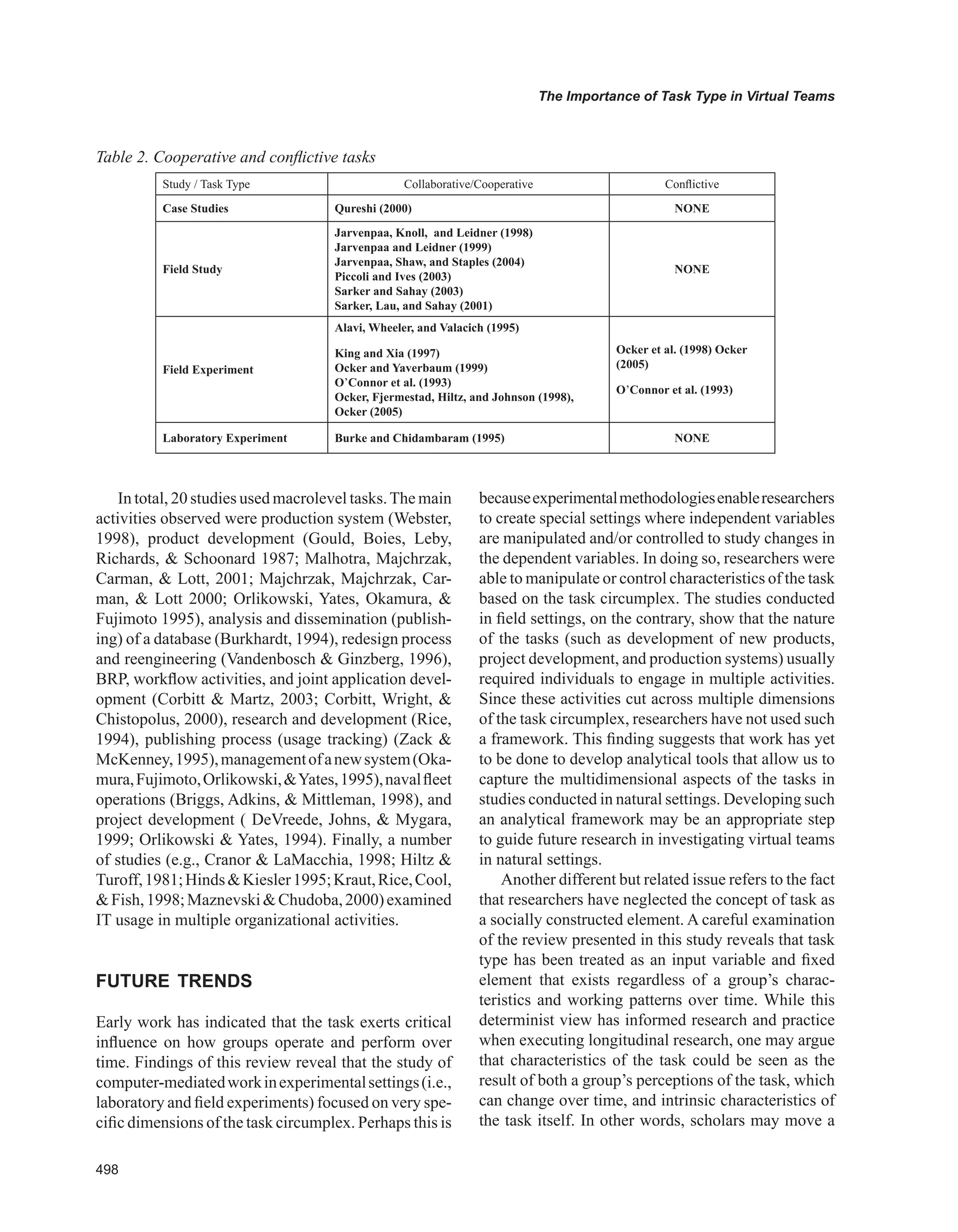

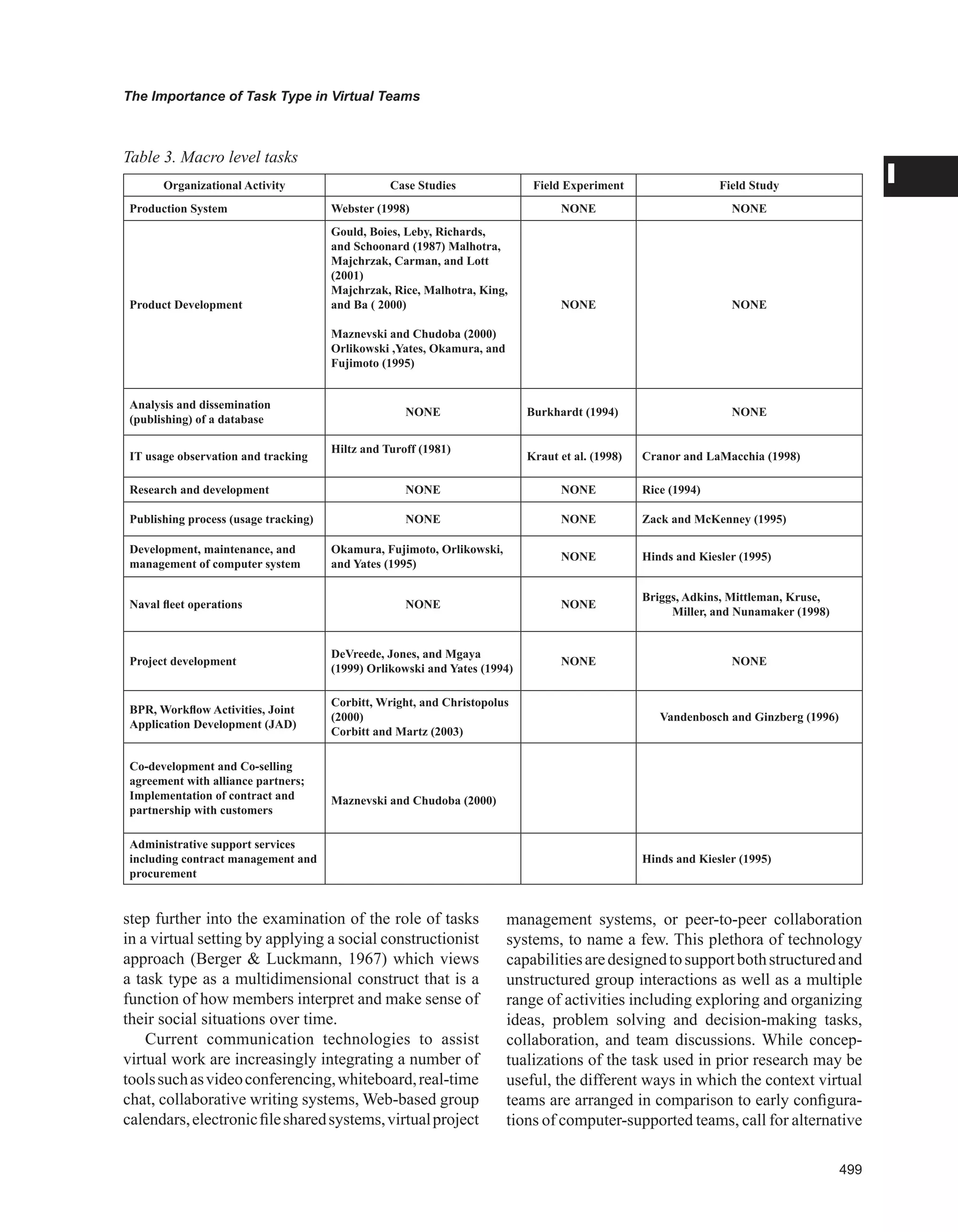

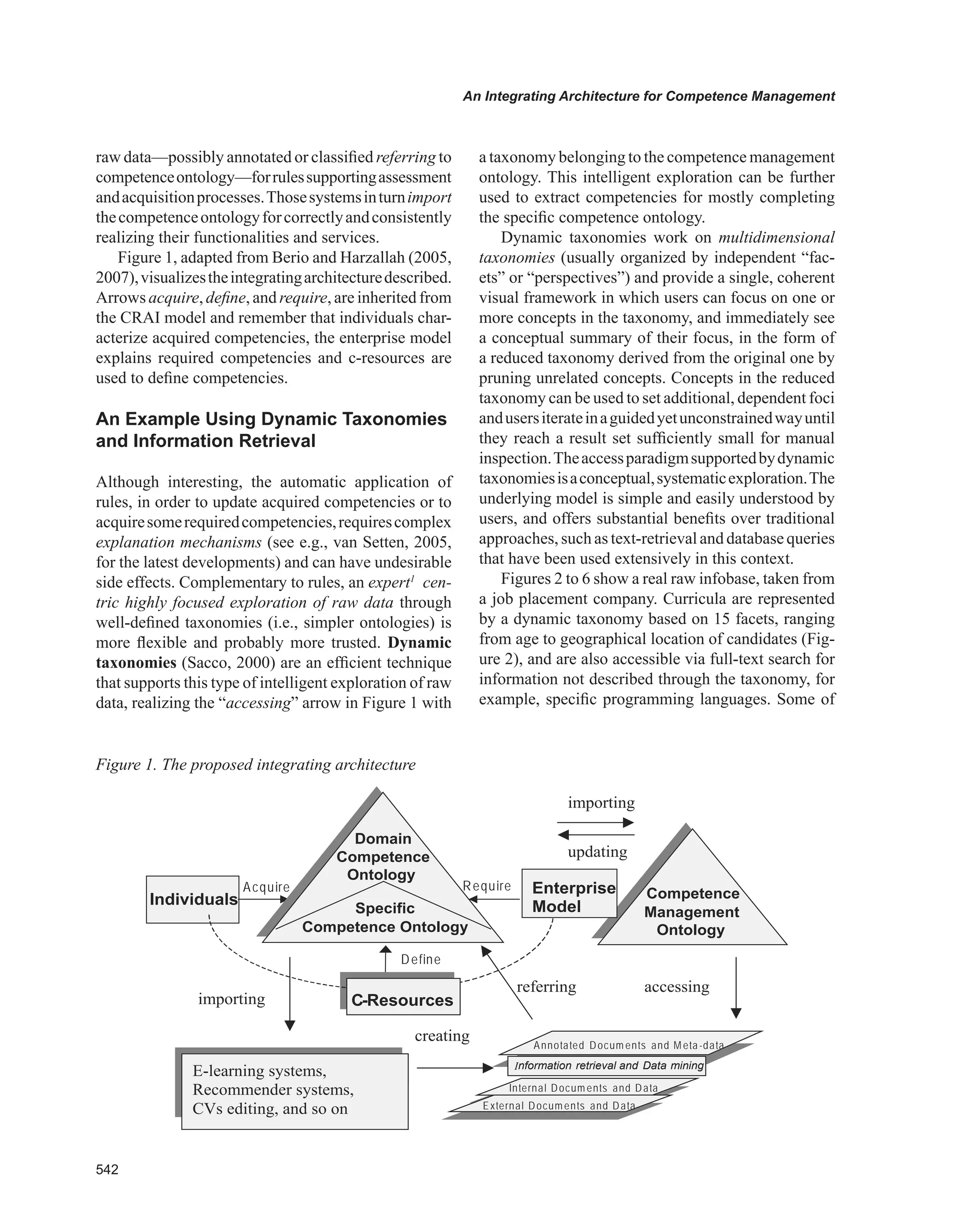

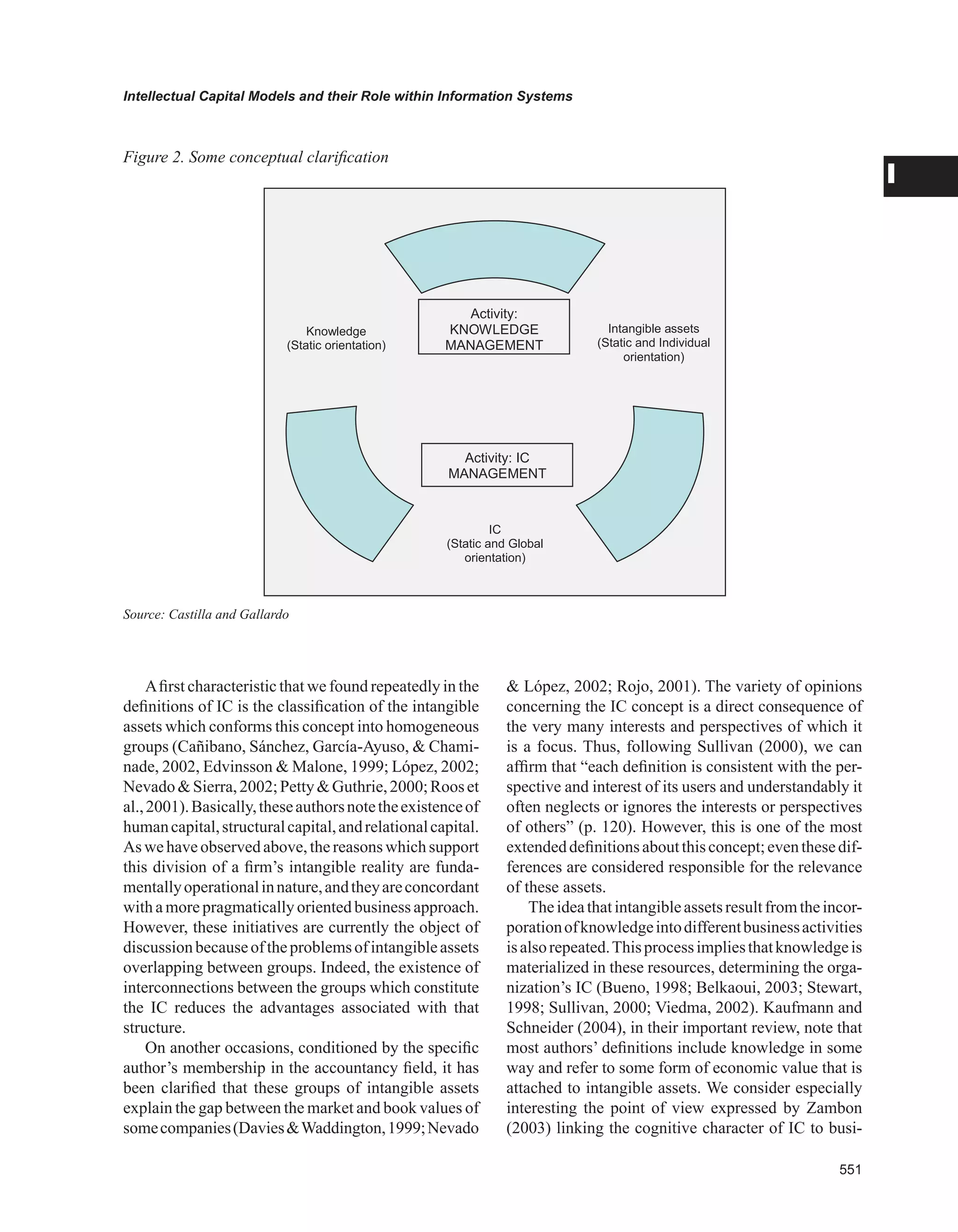

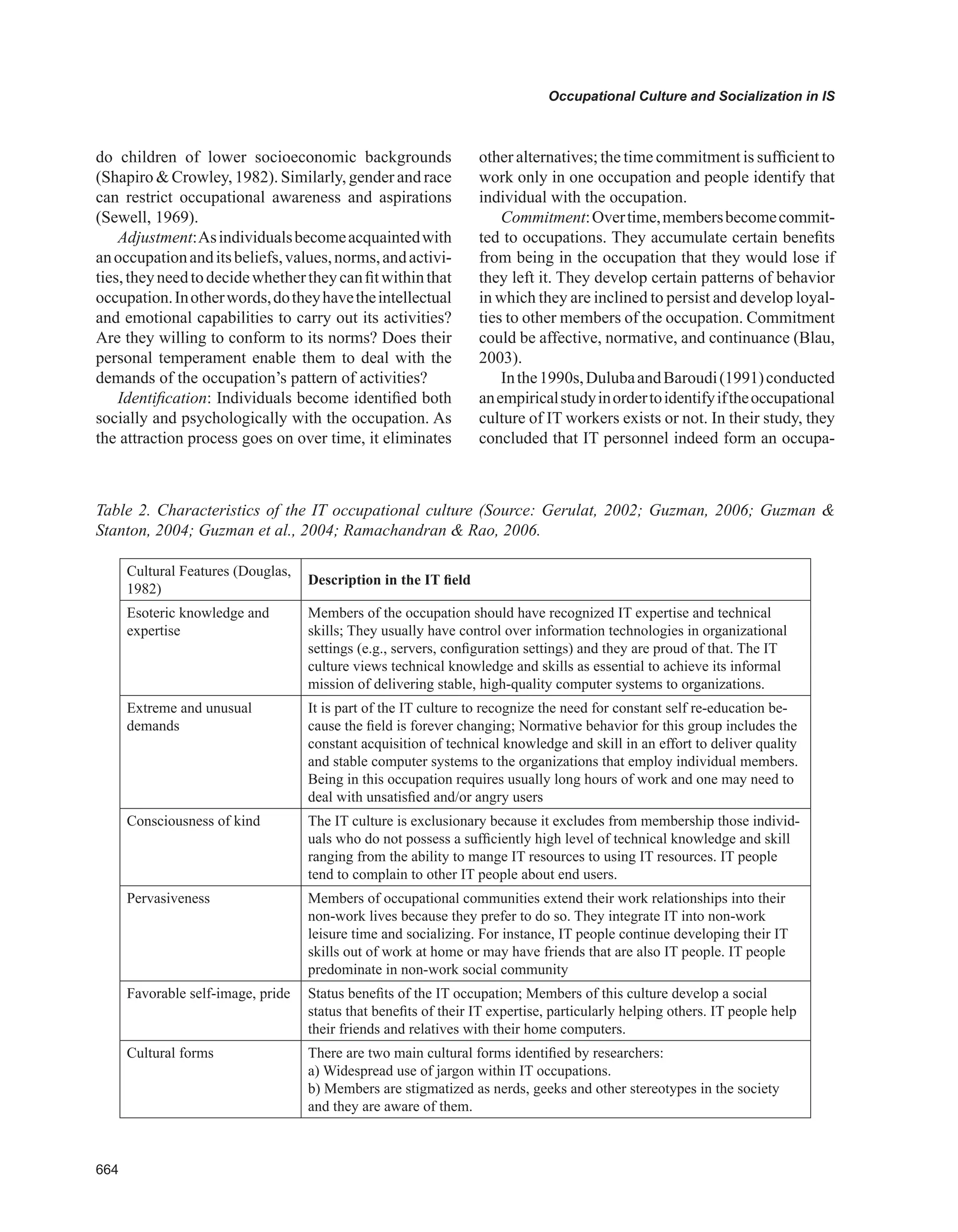

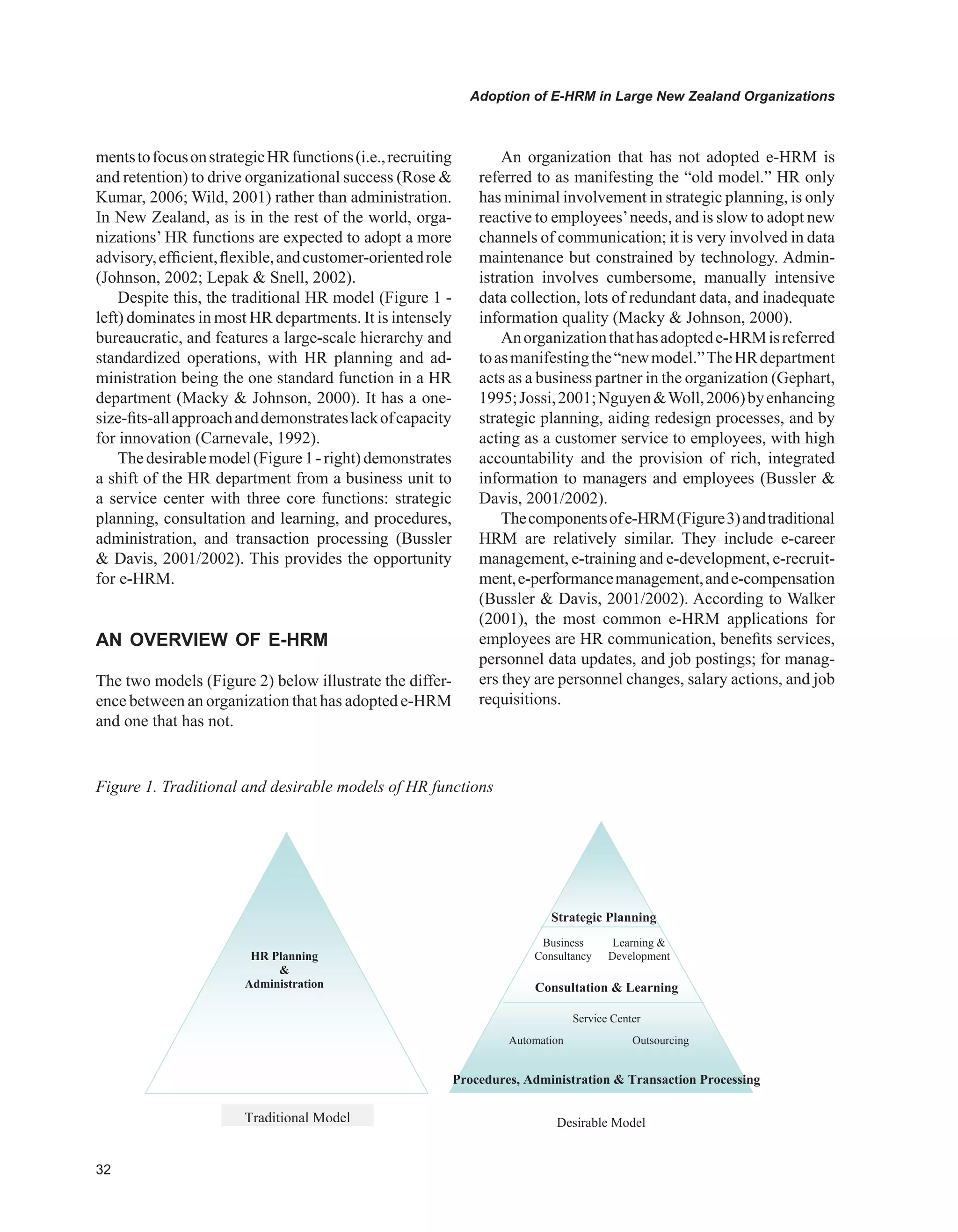

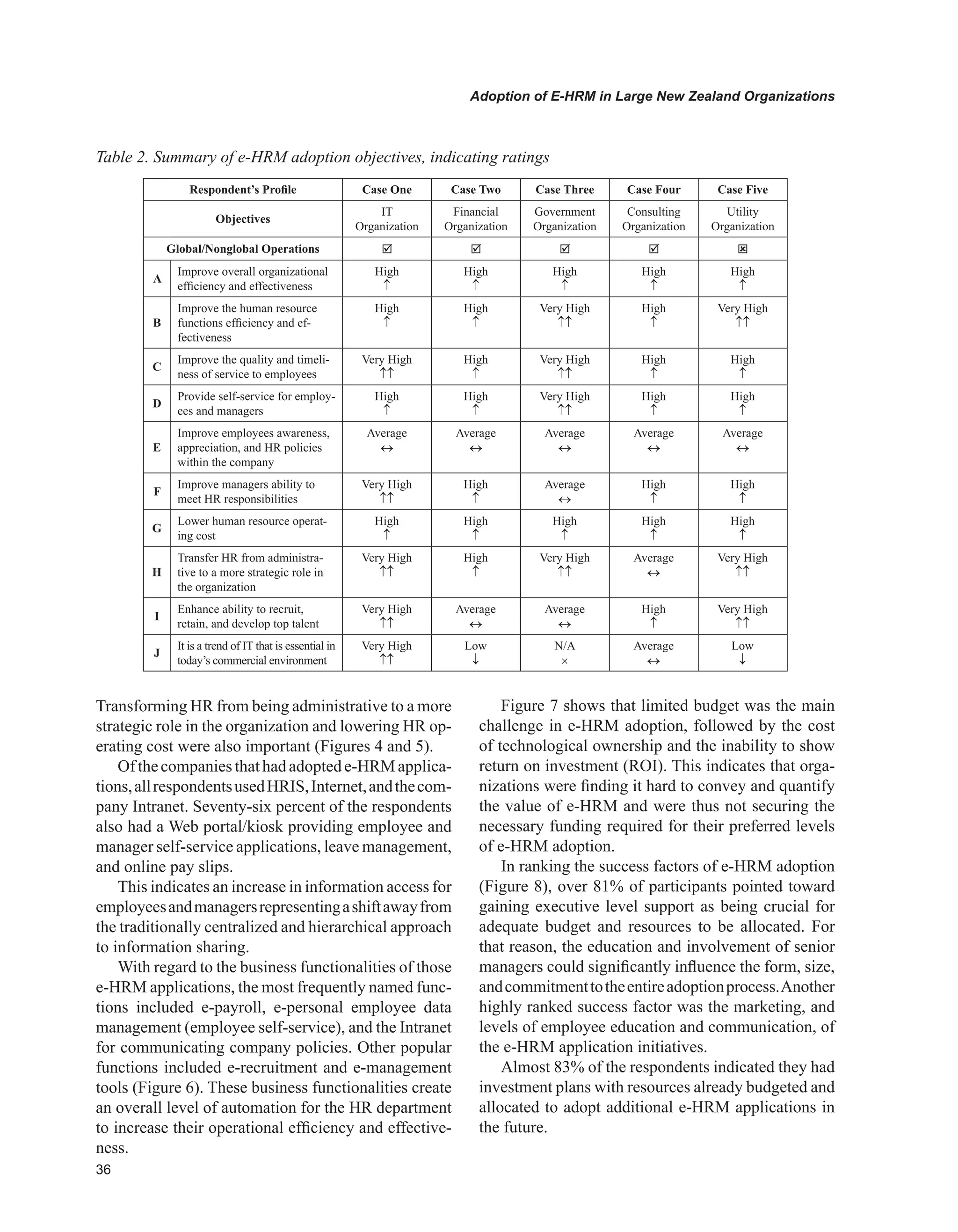

Topic: Knowledge and Organizational Learning

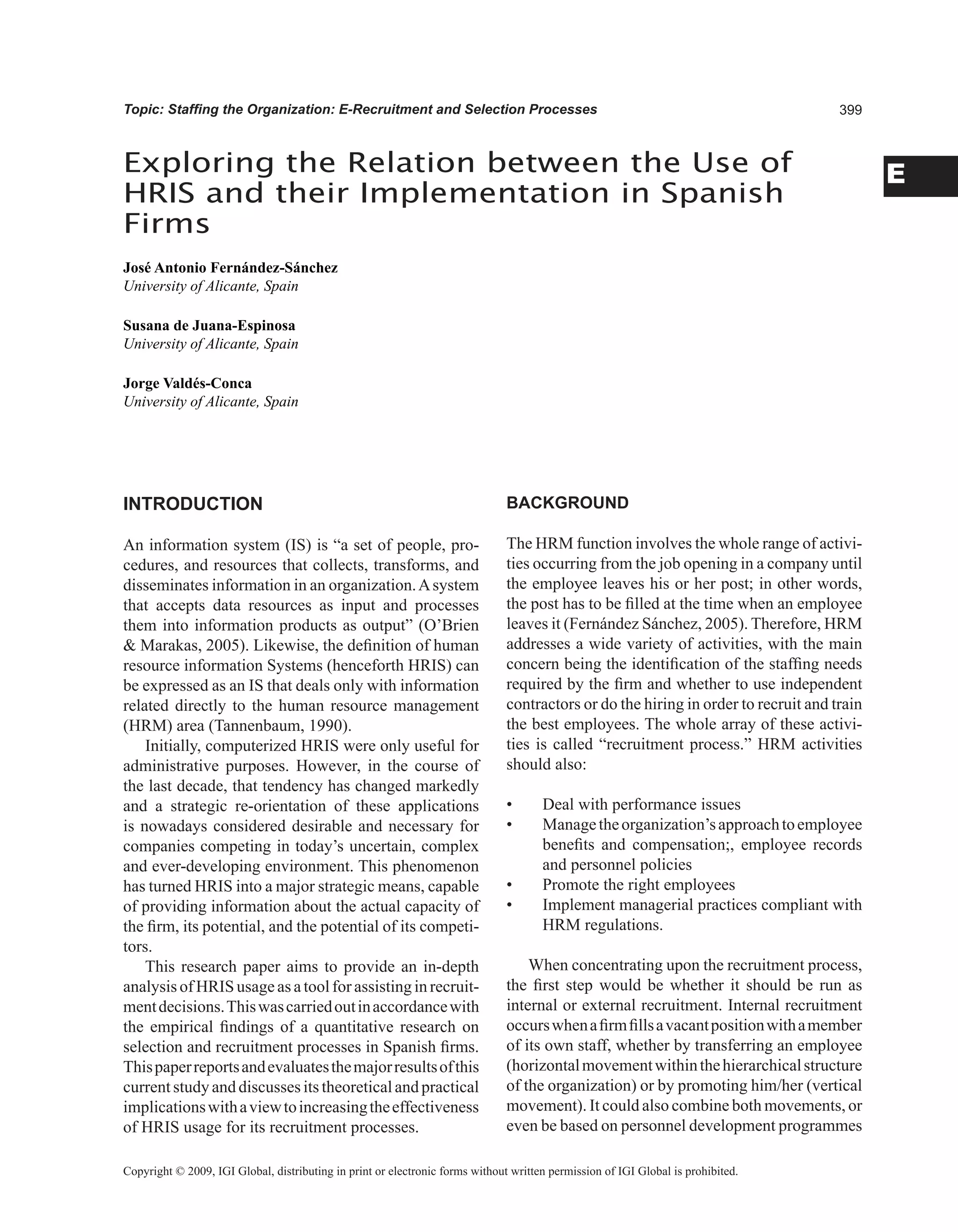

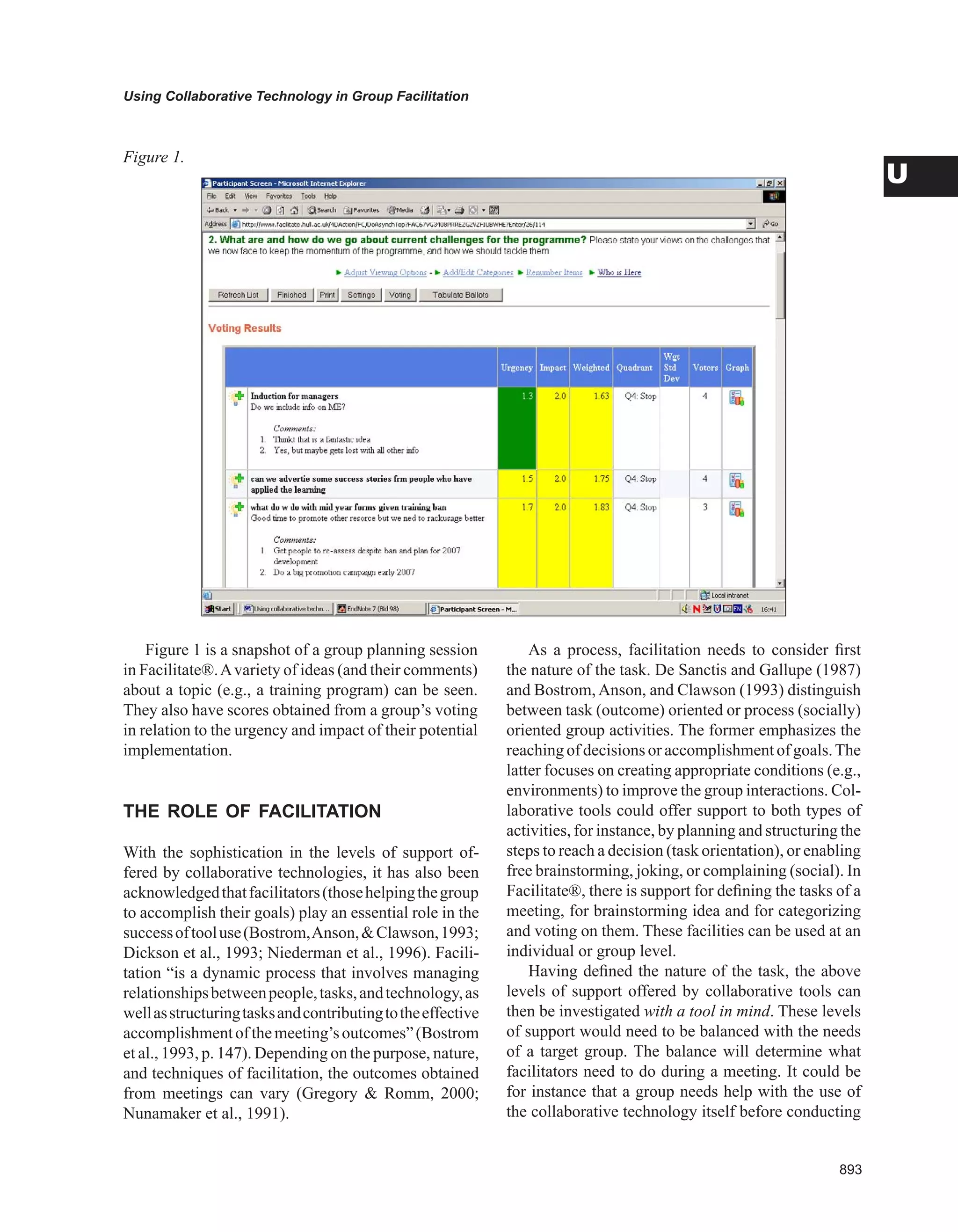

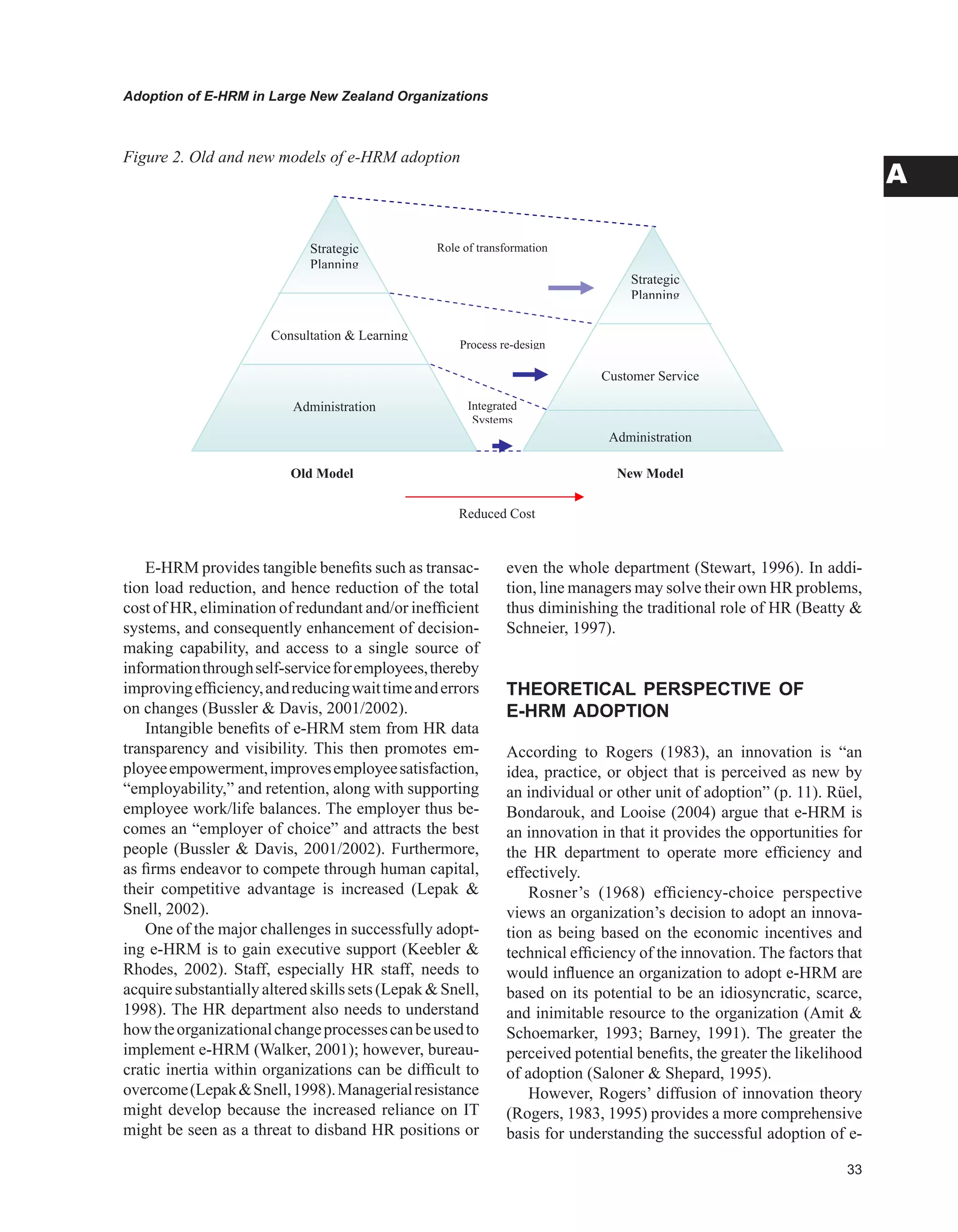

INTRODUCTION

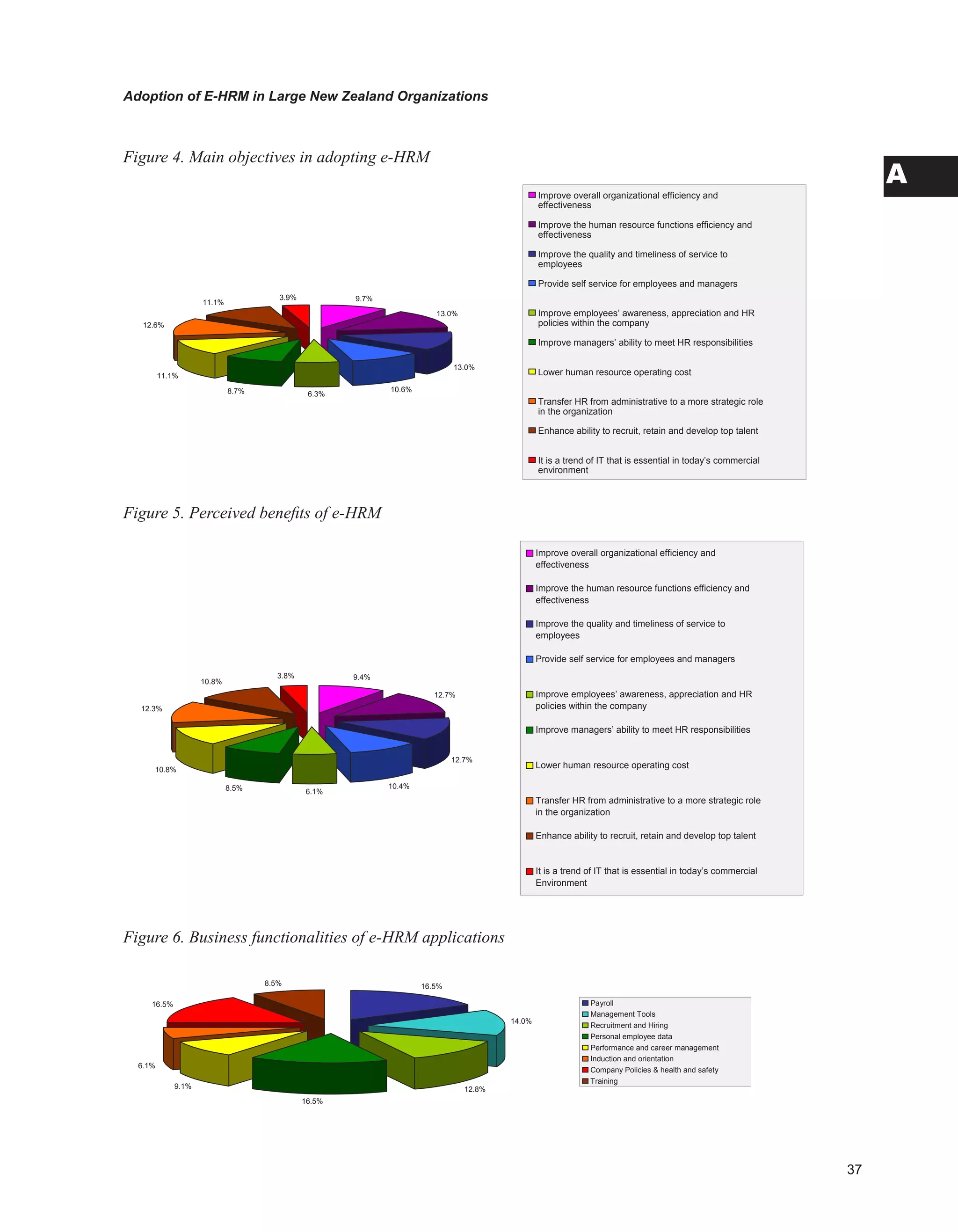

The free licenses specify the principles of use and dif-

fusion of the free software while supporting the open

and collective innovation (Chesbrough, 2003). Often,

the successes of the open-source community seem like

an implausible form of magic (see the magic cauldron

from Raymond [1999]). As Demazière, Horn, and

Zune (2006) recall it, if open source projects can be

regarded as virtual teams (Lipnack Stamps, 2000),

it should also be stressed that they seem like a true

“enigma” in sociologists eyes. Open source rests on

voluntary developers (Muffato) and does not function

on modes of production framed by wage. Moreover

these communities are not subjected to a strong plan-

ning of work but rather to a flexible calendar. What is

the human resources (HR) secret management of open

source project? In this article two main elements will

be discussed: firstly the activity theory and HR and

secondlytheopensourceprojectandtheorganizational

learning development.

BACKGROUND

Several theoretical fields propose practice, action,

and experiment to understand the field of computer

supported cooperative work. The theory of distributed

cognition makes the assumption that knowledge is not

only in the human brain but also in cognitive systems

including/understanding of the interactions between

users and the artifacts which they use (Hutchins). The

theory of situated action is centered on human activity

which emerges from a situation of work. The unit of

analysis is not the individual but the actor in the actor’s

environment (Suchmann). The activity theory concen-

trates on the mediation towards the tool and offers a

body of concepts making it possible to make bridges

with other approaches coming from social sciences. It

locatestheconscienceinthedailypracticalexperiment

and affirms that the actions are always integrated in a

social group composed of individuals and artifacts. It

integrates analysis of individual knowledge, processes

of distributed cognition, artifacts, social contexts, and

interrelationships between these elements.

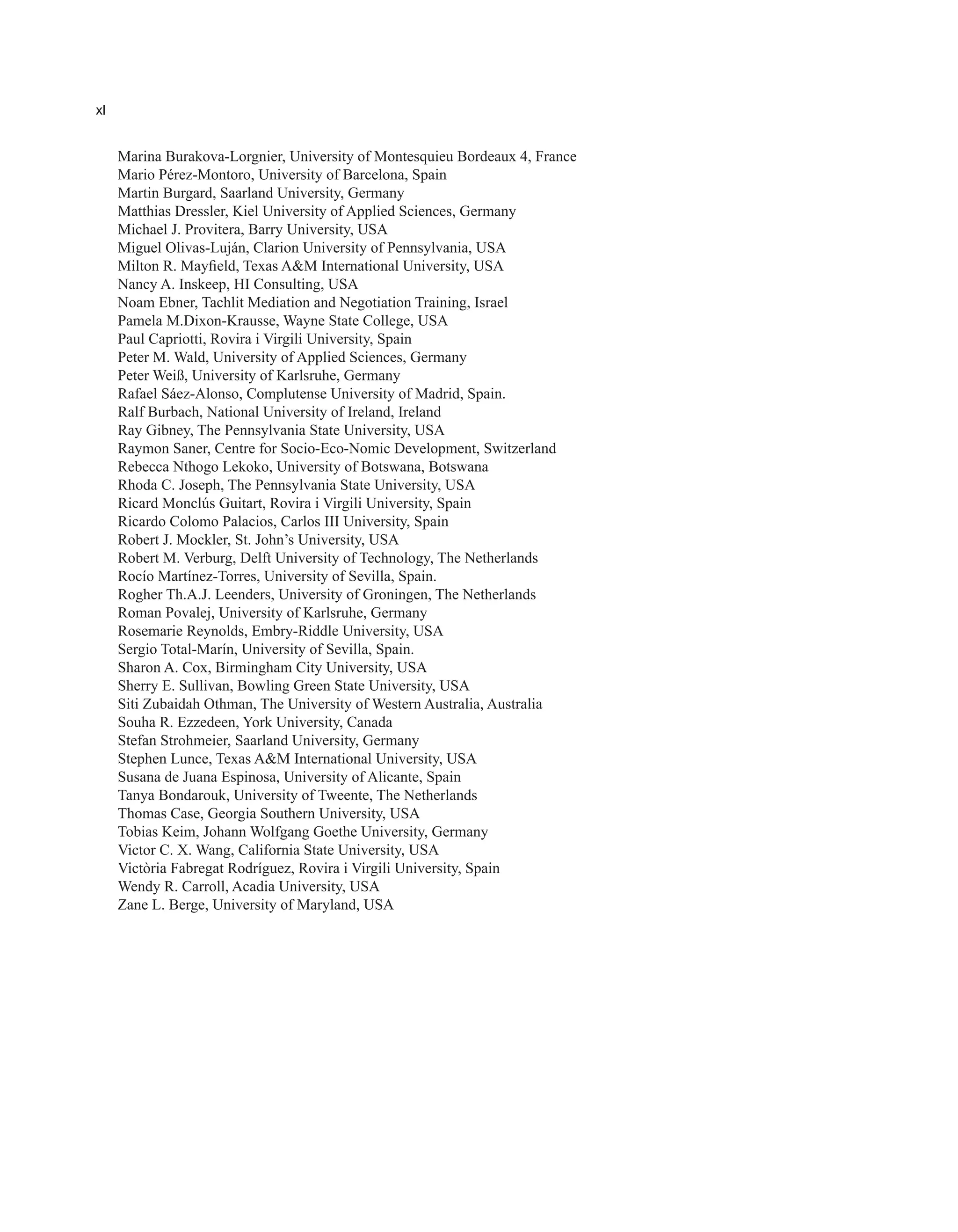

Elementsofthemodelincludeobject,subjects,tool,

community, rules, and division of labor.

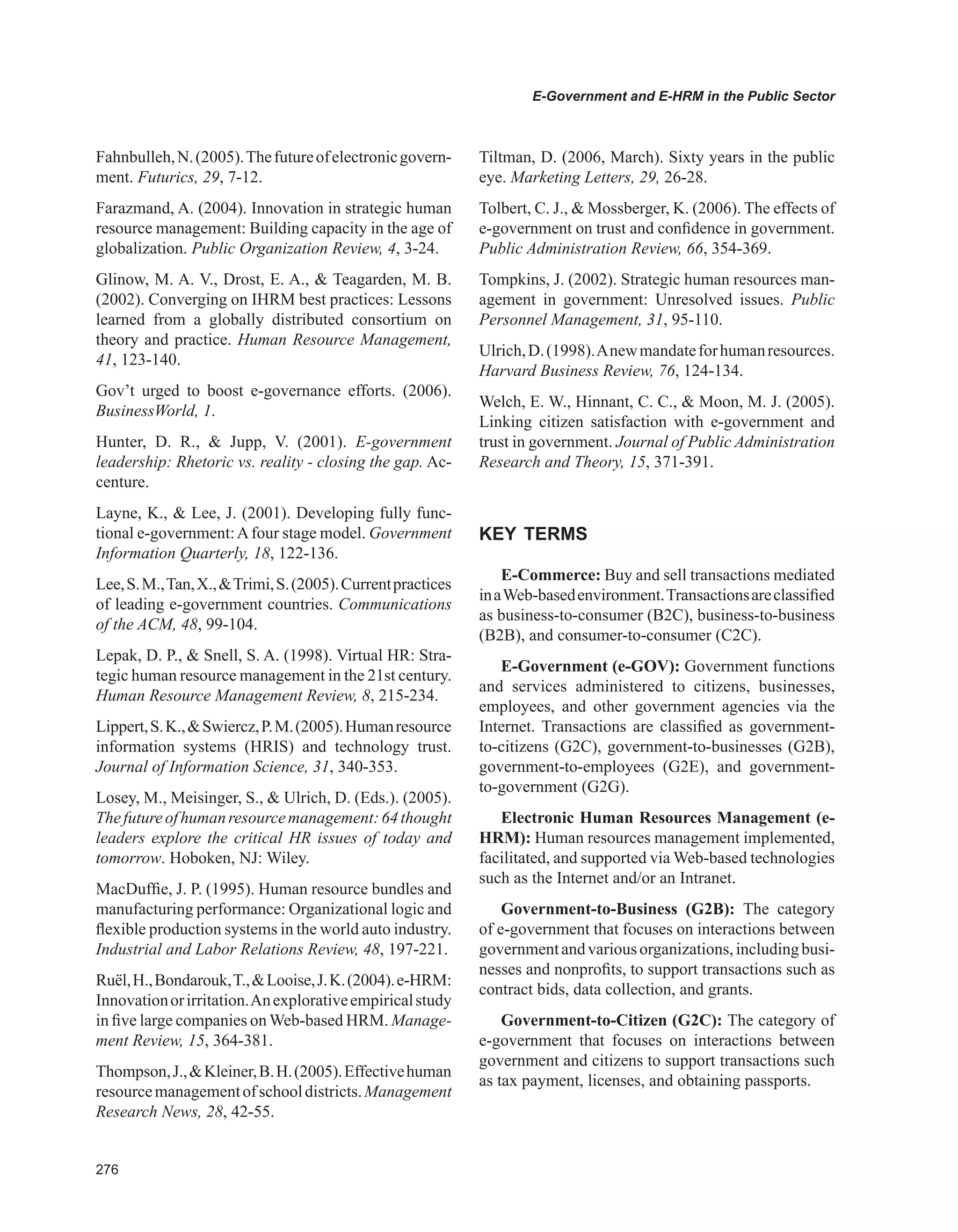

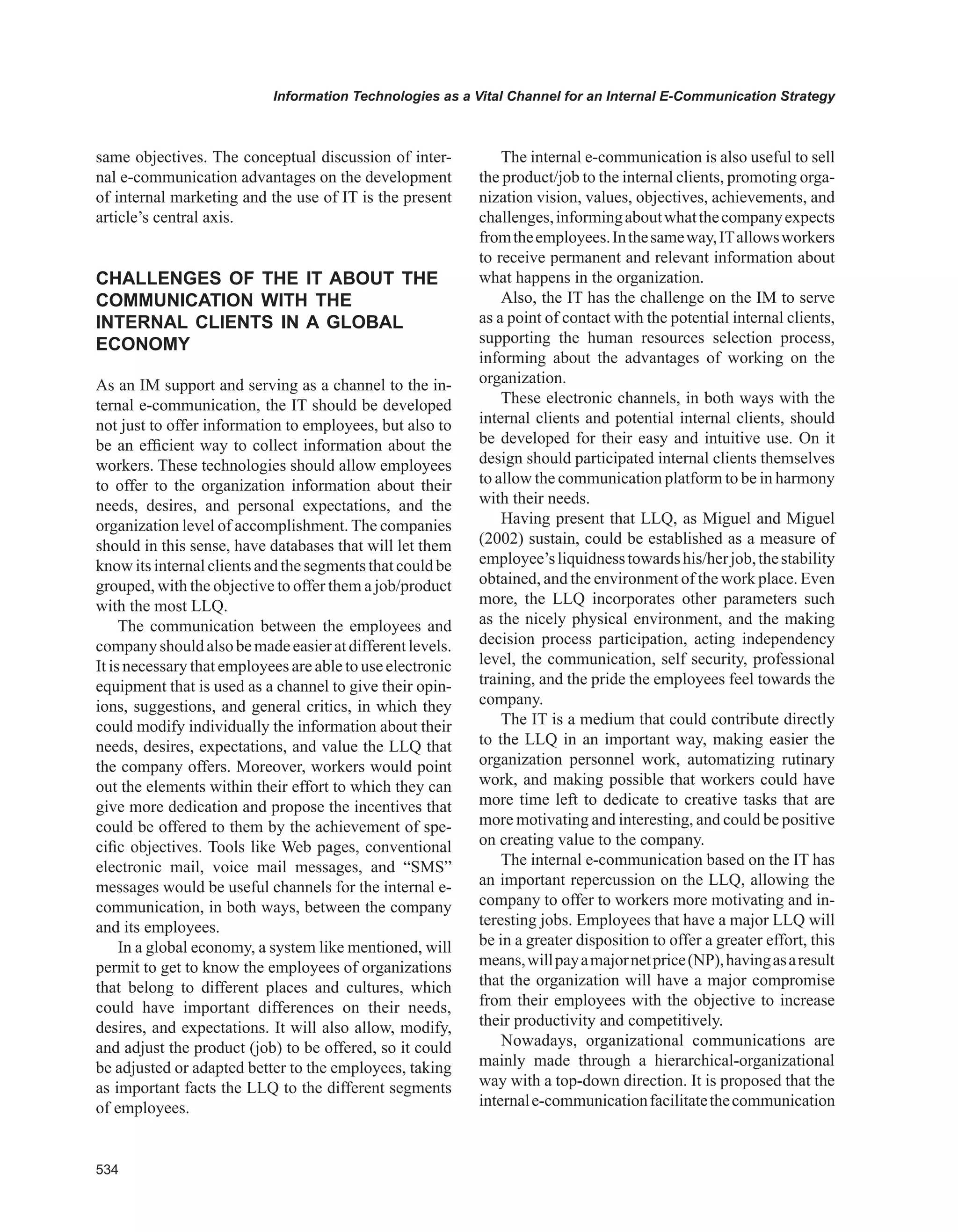

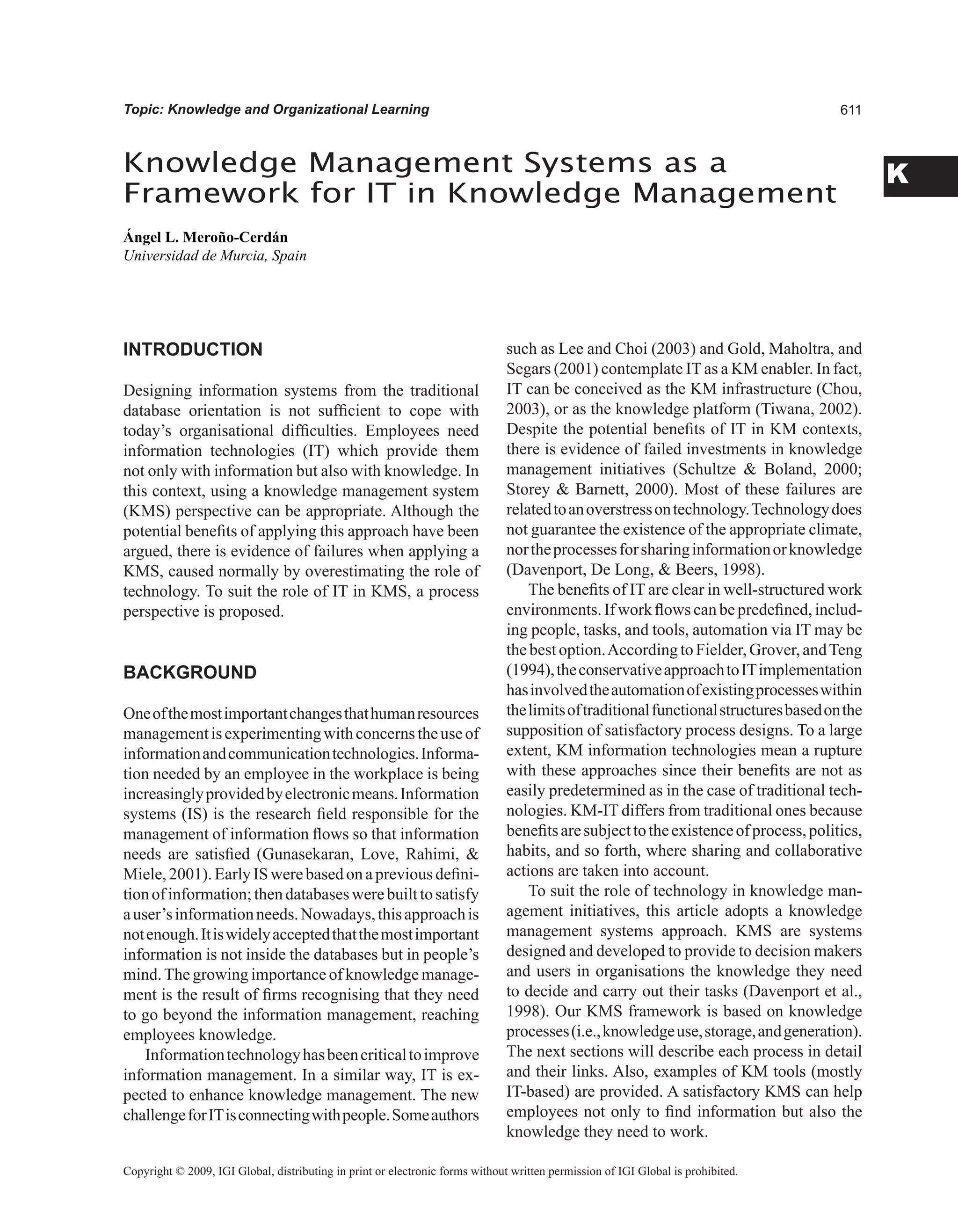

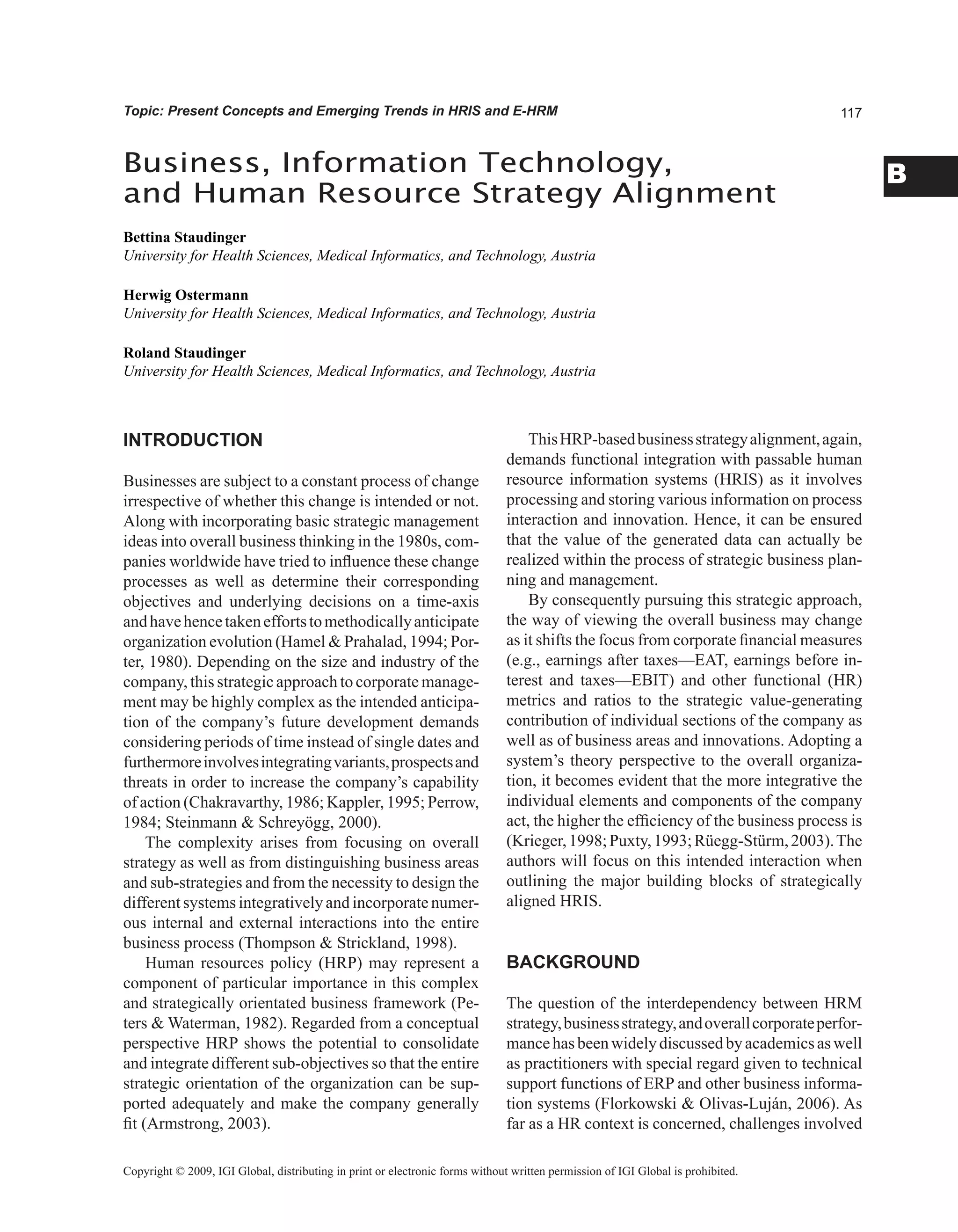

The next schema shows mediation by the tool at the

individual and collective level (Engeström, 2001)

Themodelintegratesobjectoftheactivity,theopen

source project usually accessible in a forge.

Communityisassociatedwithsubjectswhoadhere

to the same object of activity. They can be associated

with an “epistemic community” as a producer of the

open source project knowing (Cohendet, Creplet,

Dupouët 2003) and with hybridization, because they

can bring different points of view since the innova-

tion can be simultaneously worked by heterogeneous

rationalities. The community can be described as

hybrid since it mixes heterogeneous profiles driven

by divergent interests, but they are carrying changes

since they are relying on different intentionnalities

(Engeström, 2001).

Tool represents material tools (data processing)

or intellectual tools (language) used in the process of

transformation.

Rules are more or less explicit and represent stan-

dards, conventions, and accepted practices of work.

Rules carry in them cultural heritage. Concept of rule

mediates the relation between subject and commu-

nity. Within the framework of collaborative systems,

awareness is an element necessary to the activity of

a group (De Araujo Borges, 2007). The objective

is to give to users of collaborative platform dynamic

information on the activity of others. There is visibility

ofeverybodyactions.Carroll,Neale,Isenhour,Rosson,

An Activity Theory View of E-HR and Open

Source

Veronique Guilloux

Université Paris XII, France

Michel Kalika

Ecole de Management de Strasbourg, France

Copyright © 2009, IGI Global, distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-50-2048.jpg)

![Addressing Global Labor Needs Using E-Training

Tan, 2005). Generally, distance education students

perform better; i.e., their classroom performance, as

evidenced by their grades on examinations, quizzes,

assignments, projects, research papers and student

retention rates (i.e., the ratio of the number of students

who continue their education to the number that began

their studies) are also higher.

The meta-study of Zhao et al. (2005) is perhaps the

most comprehensive and robust. The results of their

study also identify an additional critical variable to

the overall success of distance education: the degree

of collaboration. As the instructor direct involvement

in the students’ learning is increased (e.g., telephone

calls, audio-conferencing, live discussions, Q-and-

A) the effectiveness of distance education improves

Johnson and Johnson (1996) found that collaboration

has a significant impact on learning, regardless of the

method of delivery chosen for that education. Students

engagedincollaborativelearningdobetterthanthosein

non-collaborative situations and enjoy it more, too.

Isonedistanceeducationtechnologymoreeffective?

Yes,manystudieshavecomparedvariousdistanceedu-

cationtechnologiesandoneofthem--TVI--performsthe

best.TVIdeliversinstruction/trainingbyrequiringthat

students/trainees gather in groups to watch videotapes

of students that are working in a classroom with a live

instructor and then undergo a structured discussion of

that experience. Discussions are led by a tutor that has

been trained to lead such discussions, charged with

stopping the videotape when student questions arise

or when students wanted to interject their thoughts.

Gibbons,Kincheloe,andDown(1977)provideareport

of the initial development of this technology.

TVI is especially effective when used in the teach-

ing of conceptual and applied-knowledge topics.

Subsequent studies of the use of TVI include those by

Anderson, Dickey, and Perkins (2001), Lowell and

Clelland-Dunham (2000), Murray and Efendioglu

(2004), and Sipusic et al. (1999). In the last example

we report on the use of TVI to deliver an entire MBA

curriculum, in English, to students in China. Generally

the students enrolled liked their experiences with this

program, and there was no significant cultural prefer-

ence for or against TVI demonstrated by the students

(as compared to those students taking their MBA

education live on campus).

Enhancing TVI’s Effectiveness: Almost all studies

of the effectiveness of TVI conclude that the tutor is

the most important element in this distance education

technology. Subsequent studies have been directed

an enhancing the role of the tutor (i.e., improving the

tutor’seffectiveness).VanDeGriffandAnderson(2002)

reported on one study that focused on designing better

waystobetterguidediscussions.Theydiscoveredwhen

specific tools were designed to guide each discussion

theywerefoundtobehighlycorrelatedwithoverallstu-

dent satisfaction and performance. Further, an analysis

of instructor/tutor responses suggested that these tools

provided “a catalyst for questions” as well “helping”

[to assess] the students’levels of understanding” of the

materials included in the videotaped materials.

A second attempt at tutor enhancement, called

supplemental instruction, focused on the quality and

quantity of tutor-student interactions. Working in

groups, the students are directed by the discussion

leadertodevelopanswerstoquestionsthatdevelopfrom

the discussions and to predict exam questions. There

is also a video version of this technique: video-based

supplemental instruction (VSI). Studies of effective-

ness of VSI conclude that these students using this

technique generally earn higher grades, have higher

course completion rates, and higher graduation rates

(Martin, Arendale, Blanch, 1997).

Since the success of TVI is a direct function of the

quality and quantity of discussions, can technology

somehow “create” a replacement for the discussions?

One comprehensive model, DistributedTutoredVideo

Instruction(DVTI),wasdesignedbySunMicrosystems

to simulate face-to-face TVI sessions.

The [DVTI] system uses an open microphone archi-

tecture in which anyone can speak and be heard at

the same time. Students wear stereo headphones with

a built-in microphone attached . . . Real-time video of

each participant’s face and upper body is delivered

from a camera positioned beside the monitor. These

images are arrayed in individual cells of a 3x3 “Brady

Bunch”matrix.Videotapeofthecourselectureplaysin

the lower right cell . . . The tutor controls the VCR that

plays the course video. Students can verbally request

thatthetutorpausethetapeorcansendapauserequest

message to the tutor by pressing a button on the user

interface (Sipusic et al., 1999, p. 6-7)

A comparison study of DTVI against TVI showed

that there was no statistical difference between the stu-

dentsatisfactions,althoughtheTVIstudents“enjoyed”

theircoursemorethanthosethatweretakingthecourse](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-57-2048.jpg)

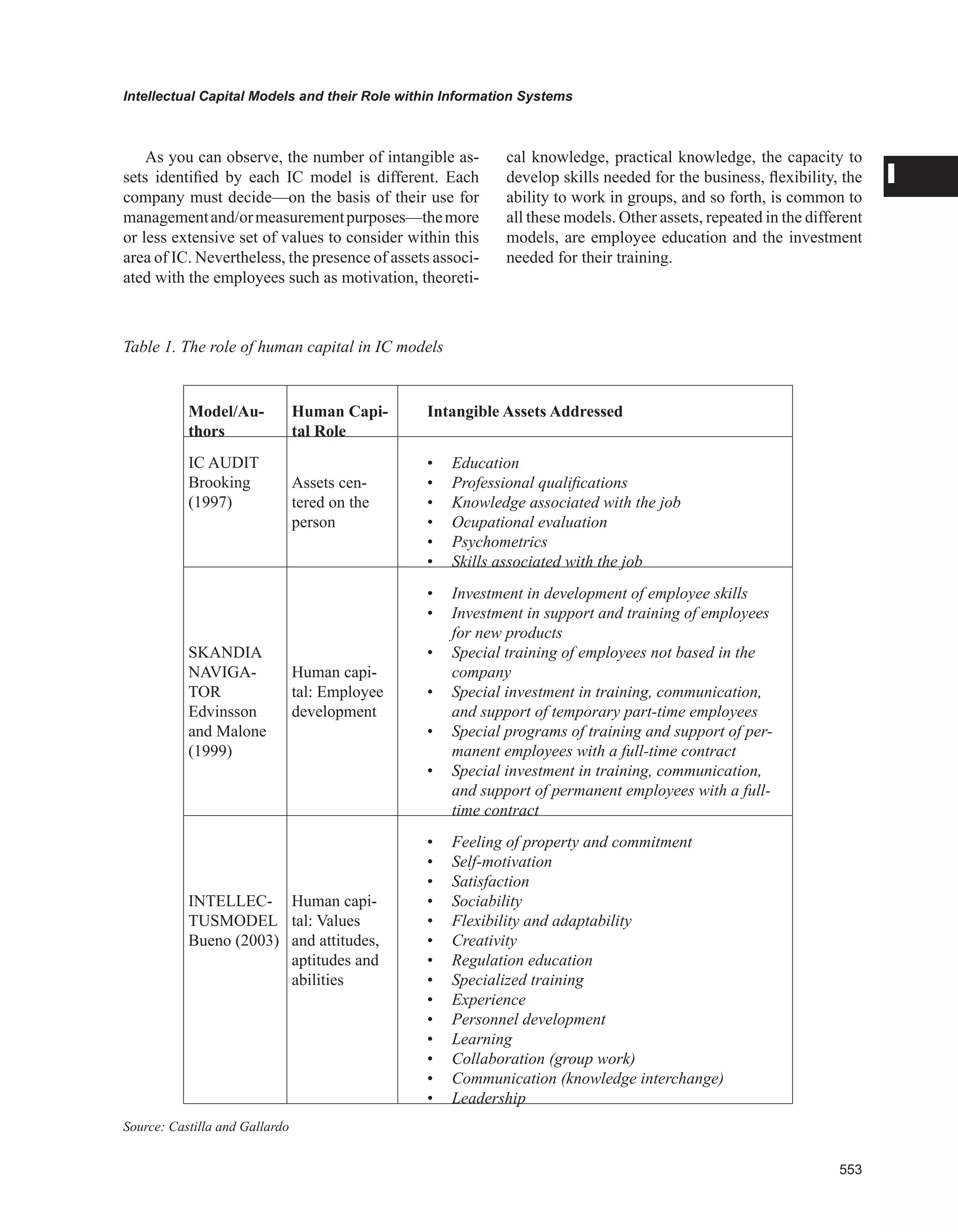

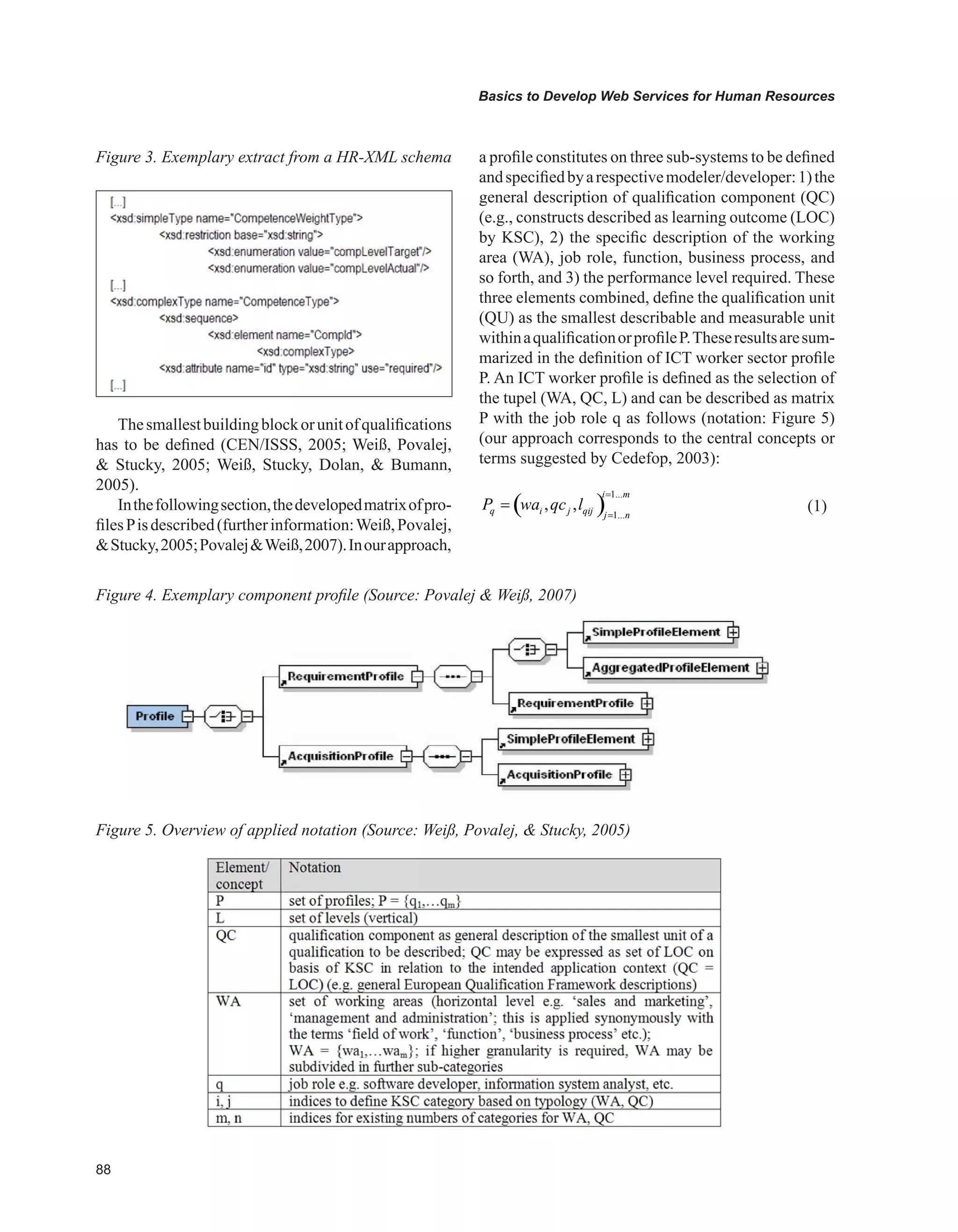

![Topic: Competence Development and Compensation

INTRODUCTION

Inthisarticlecertainpillarsasbasicsarepresentedbeing

necessary to develop Web services (W3C, 2007) sup-

porting human resource (HR) processes like assessing,

hiring, modeling information systems, staffing, and so

forth; by the help of these Web services. Current HR

information systems in general do not adequately sup-

porttasksrelatedtocross-organizationalorglobalskills

and competence management. In the following, the

topic is presented which relates to knowledge manage-

ment especially to “communities of practice,” as well

as related topics such as e-skills and ICT (information

andcommunicationtechnologies)professionalism;the

latter currently being broadly discussed by experts in

Europe.

HR managers of a company or an organization

are challenged through the need to formalize skills

requirements and to continuously monitor the skills

demand inside the company. Obtaining ICT skills are

not a one-time event. Technological change advances

at a high speed and requires that skills need continu-

ally to be kept up-to-date and relevant (The European

e-Skills Forum [ESF], 2005).

During the last years, new concepts have emerged

which intend to empower learners and individuals to

steer learning processes to a large extent on their own.

Learning objectives tend to be increasingly individual

in character (ESF, 2005).

In this context, providing an appropriate infra-

structure which supports the continuing professional

development (CPD) of employees is today a key is-

sue. CPD processes require a respective infrastructure

encompassesbesidesqualifications,skills/competence

frameworks and body of knowledge, as well required

standards for competence, skills, and appropriate ca-

reer and development services. Standards encompass

educational and industry-oriented performance stan-

dards which in turn are expressed preferably through a

common language as competence and skills standards.

ThegovernanceandadministrationoftheCPDprocess

require the availability of flexible and personalized

certification services which offer the formal validation

of individuals’ learning achievements independent of

where and how they were acquired.

Recruitment and internal mobility are typical use

cases to identify the right people wanted, by matching

theirassessmentoutcomeswithjobpositionsrequested.

In case a company needs new ICT competence, the

HR manager in charge has to draw up a job advertise-

ment, which describes the required knowledge, skills,

competences (KSC), and qualifications for the specific

job role. The information is generally structured in a

job profile, which mirrors ideally the companies core

competences; but how can this be efficiently done or

supported by a concept method and/or tool, how can

be potential employees be addressed independently of

their national origin? Further scenarios can be derived

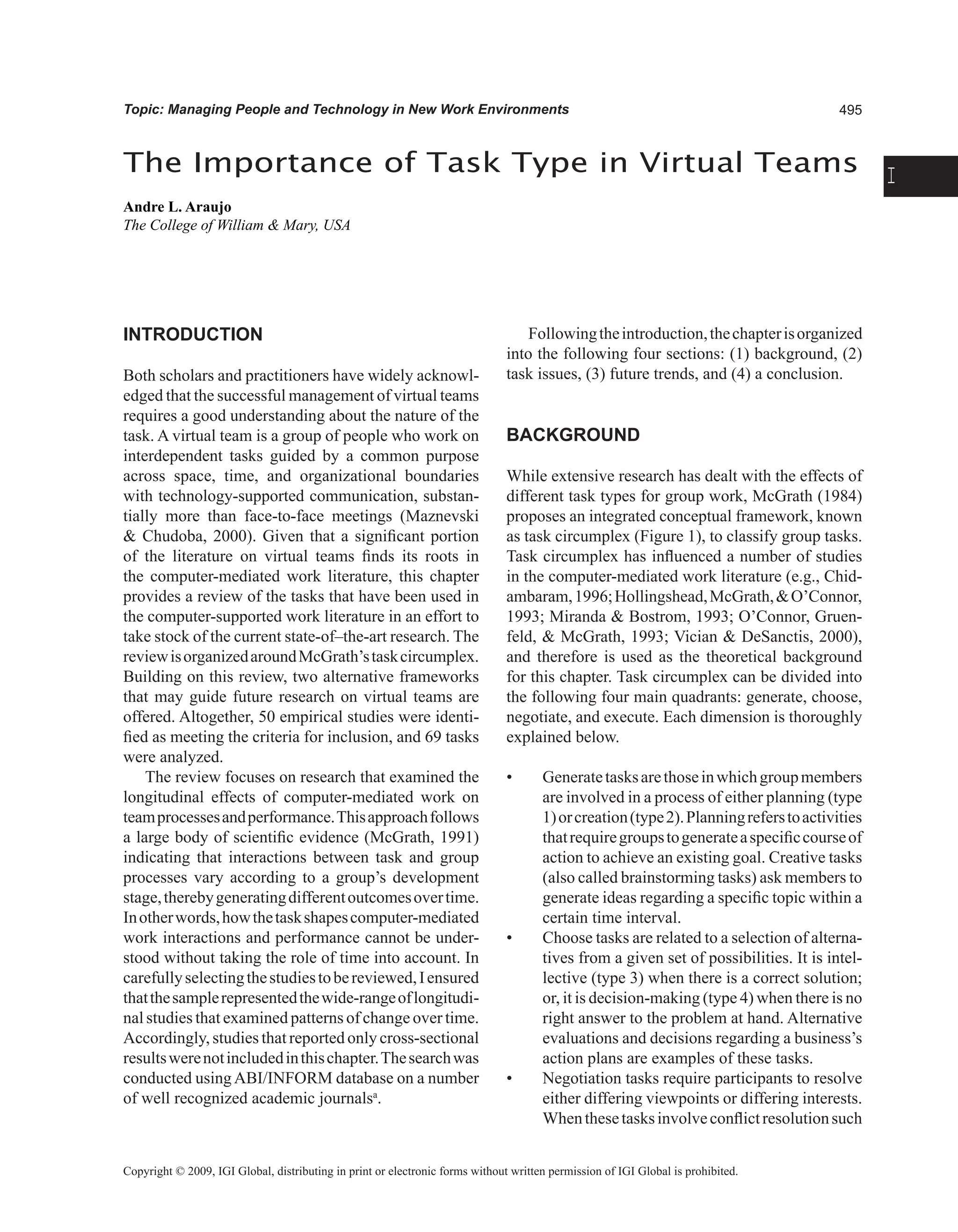

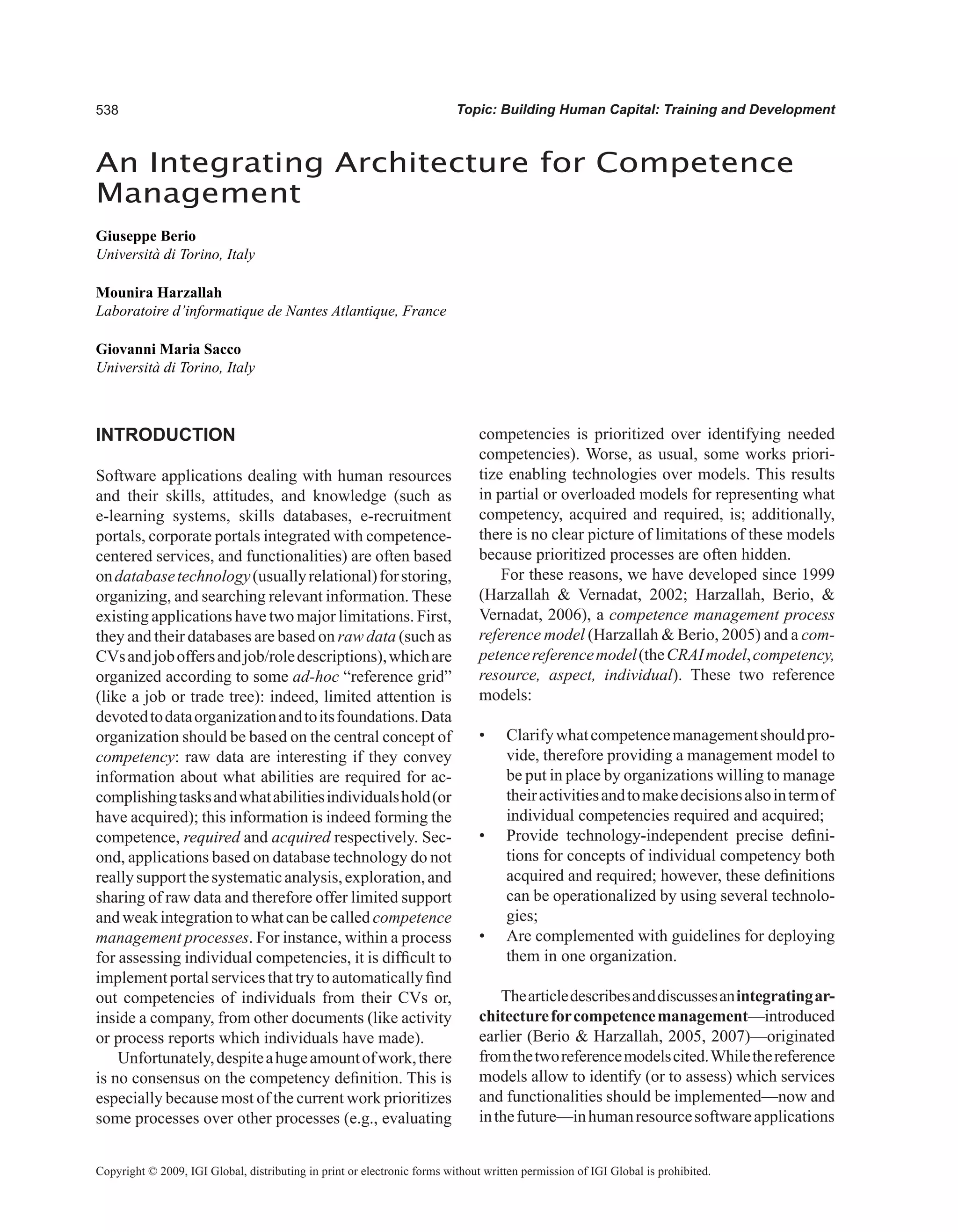

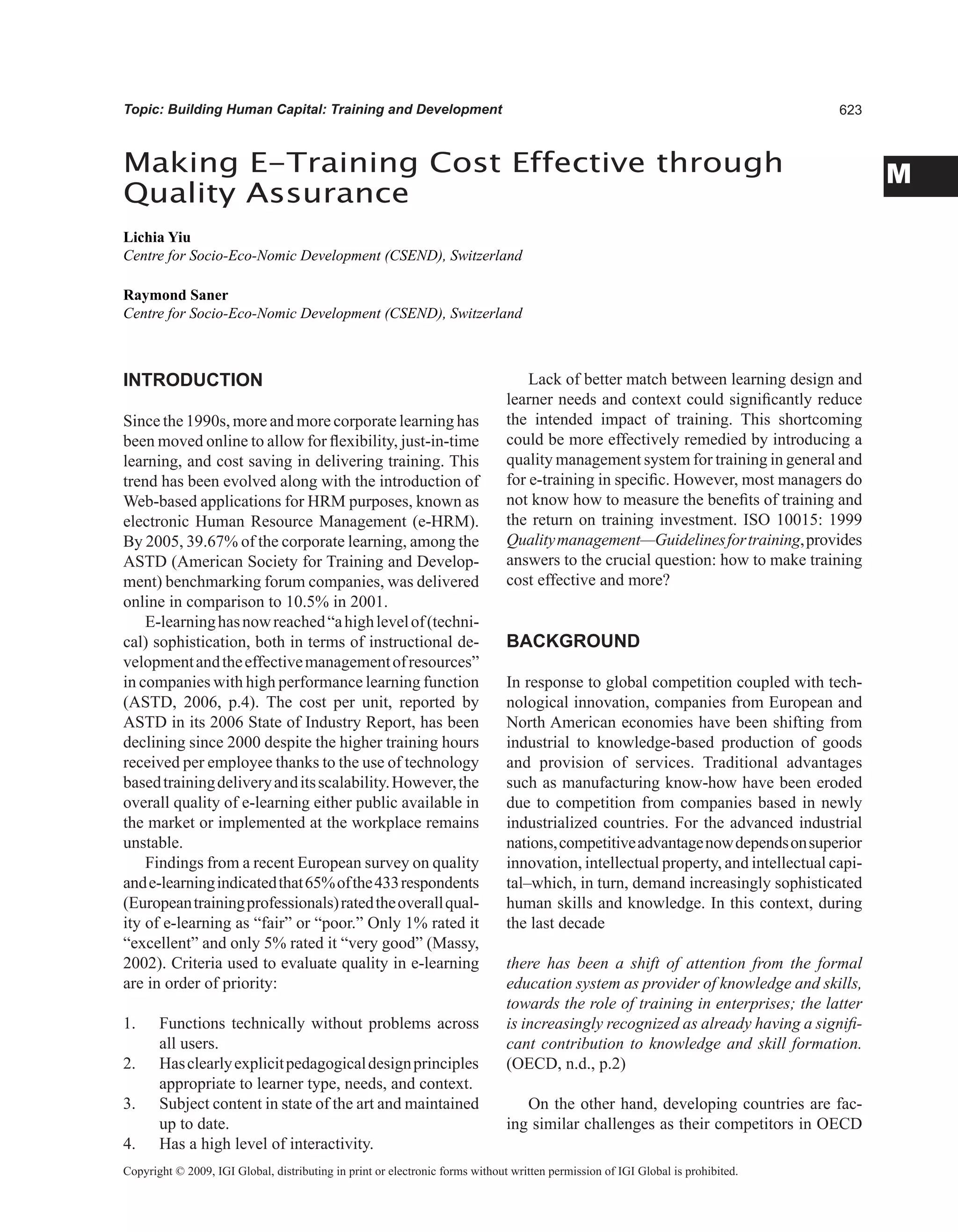

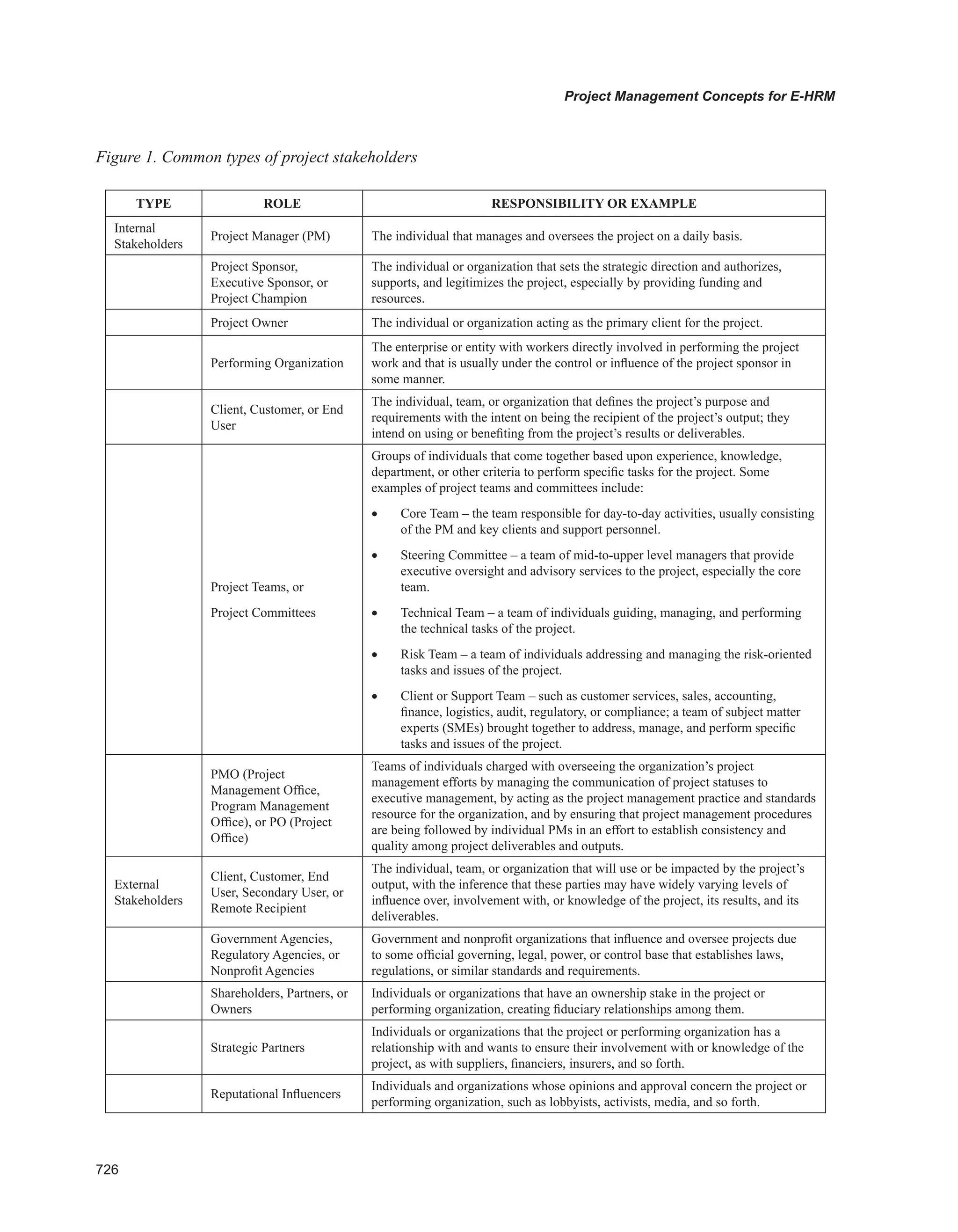

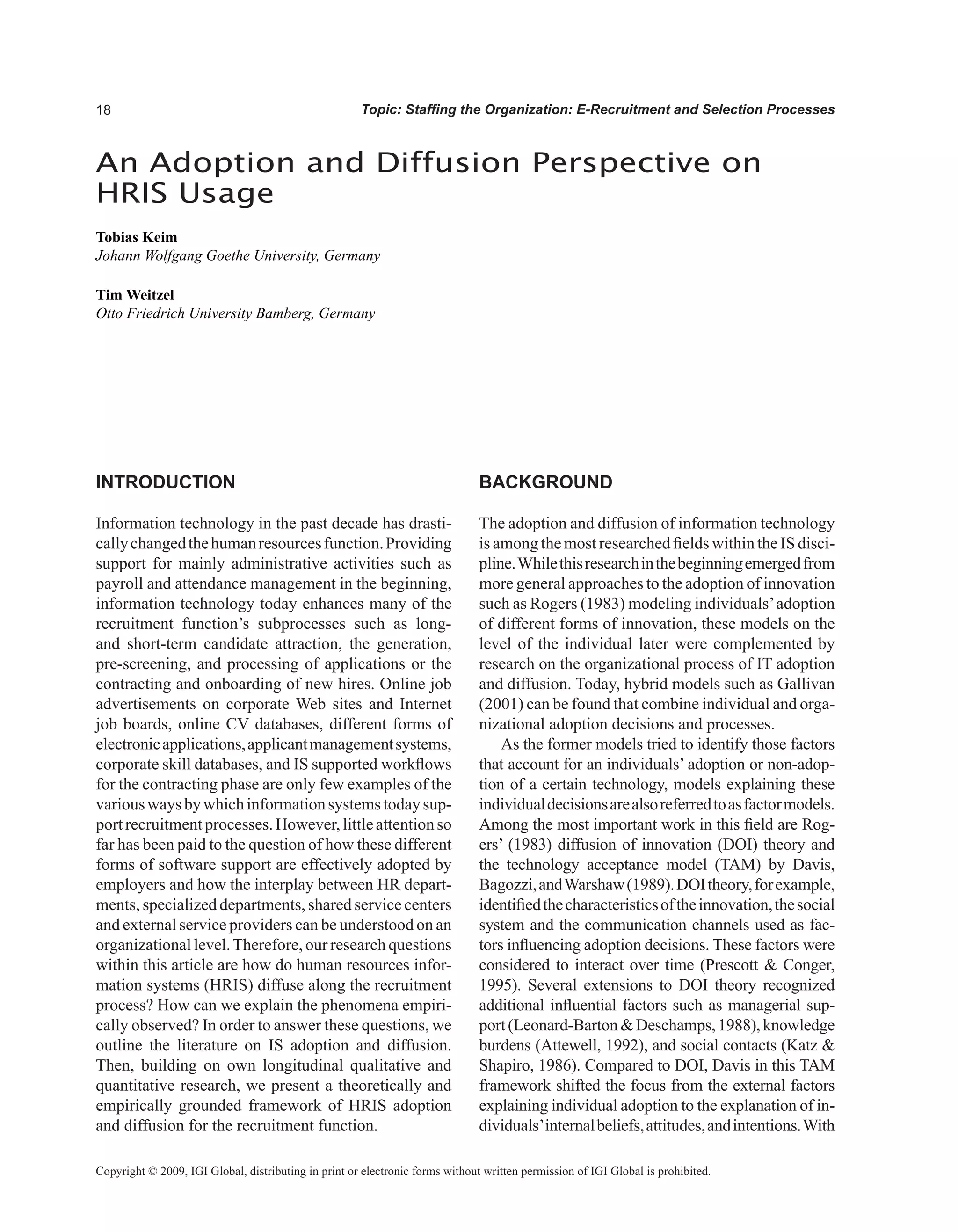

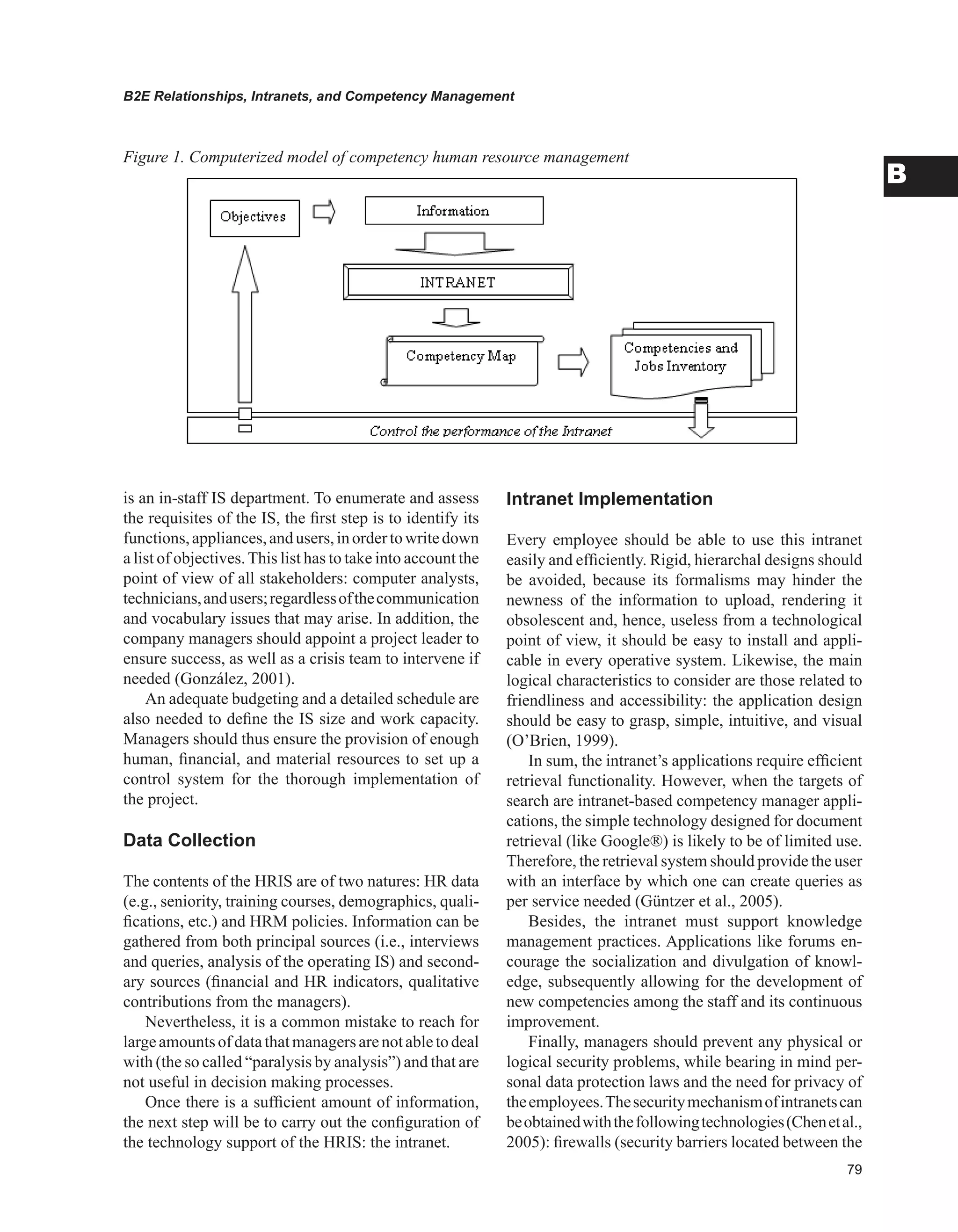

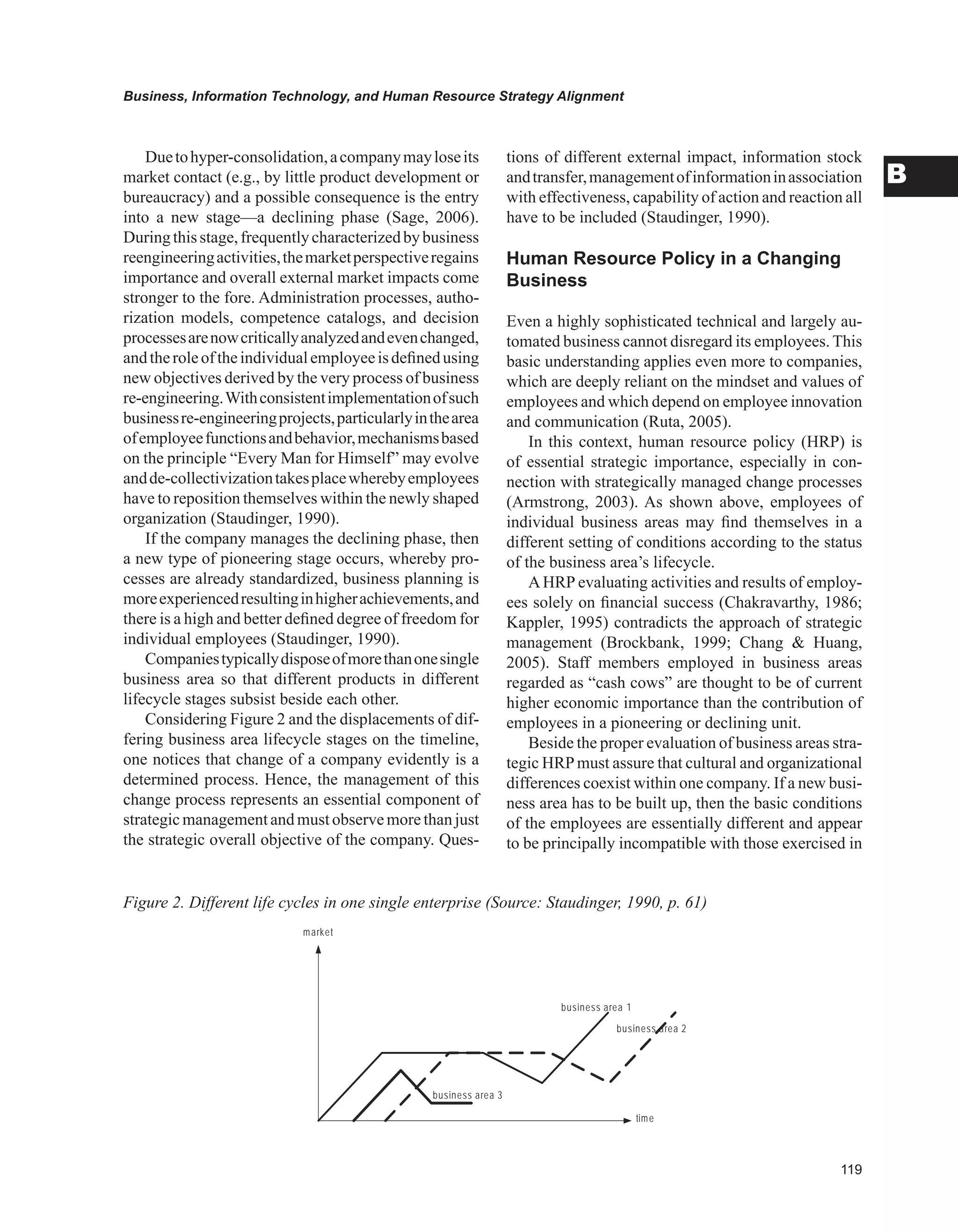

from Figure 1.

Noticeably, information about requirements is ex-

changedamongstvariousplayersalongthevaluechain.

Hence, looking at ICT skills requirements necessitates

looking at the belonging processes as a whole. This

relates to a common language which allows exchang-

ing information amongst the various players involved

and exchange of data stored in respective HR-systems.

The latter, in particular, motivates data services which

facilitate sharing of data required for the execution of

tasks along the HR processes (such as recruitment of

ICT professionals). Typically, systems do not have

the required interoperability because the applied data

models differ in structure and semantics. In the follow-

ing, we look at how to achieve better interoperability

of systems and an enhanced sharing of information

about ICT skills requirements typically stored in job

or ICT worker profiles.

Basics to Develop Web Services for Human

Resources

Roman Povalej

University of Karlsruhe (TH), Germany

Peter Weiß

University of Karlsruhe (TH), Germany

Copyright © 2009, IGI Global, distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-127-2048.jpg)

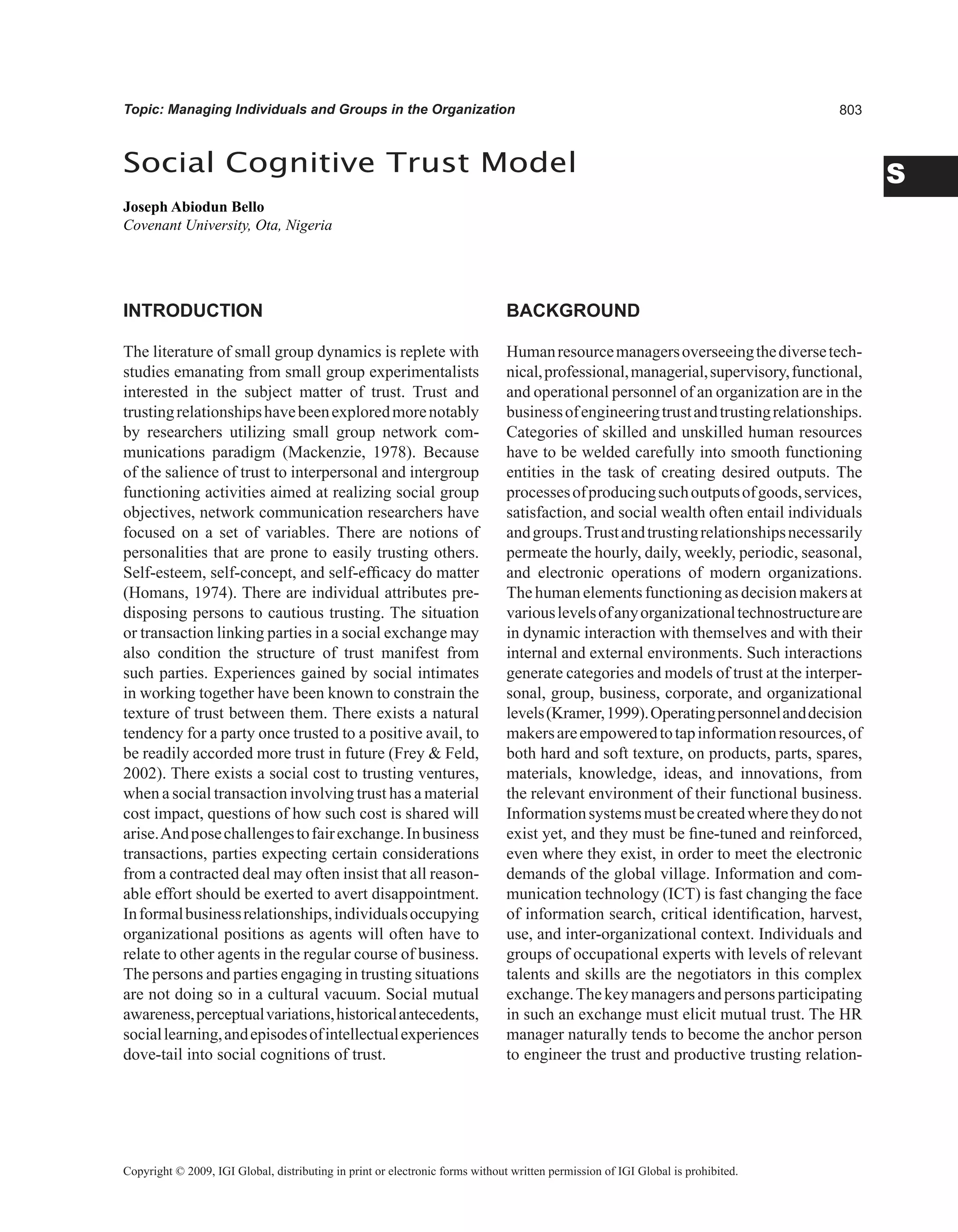

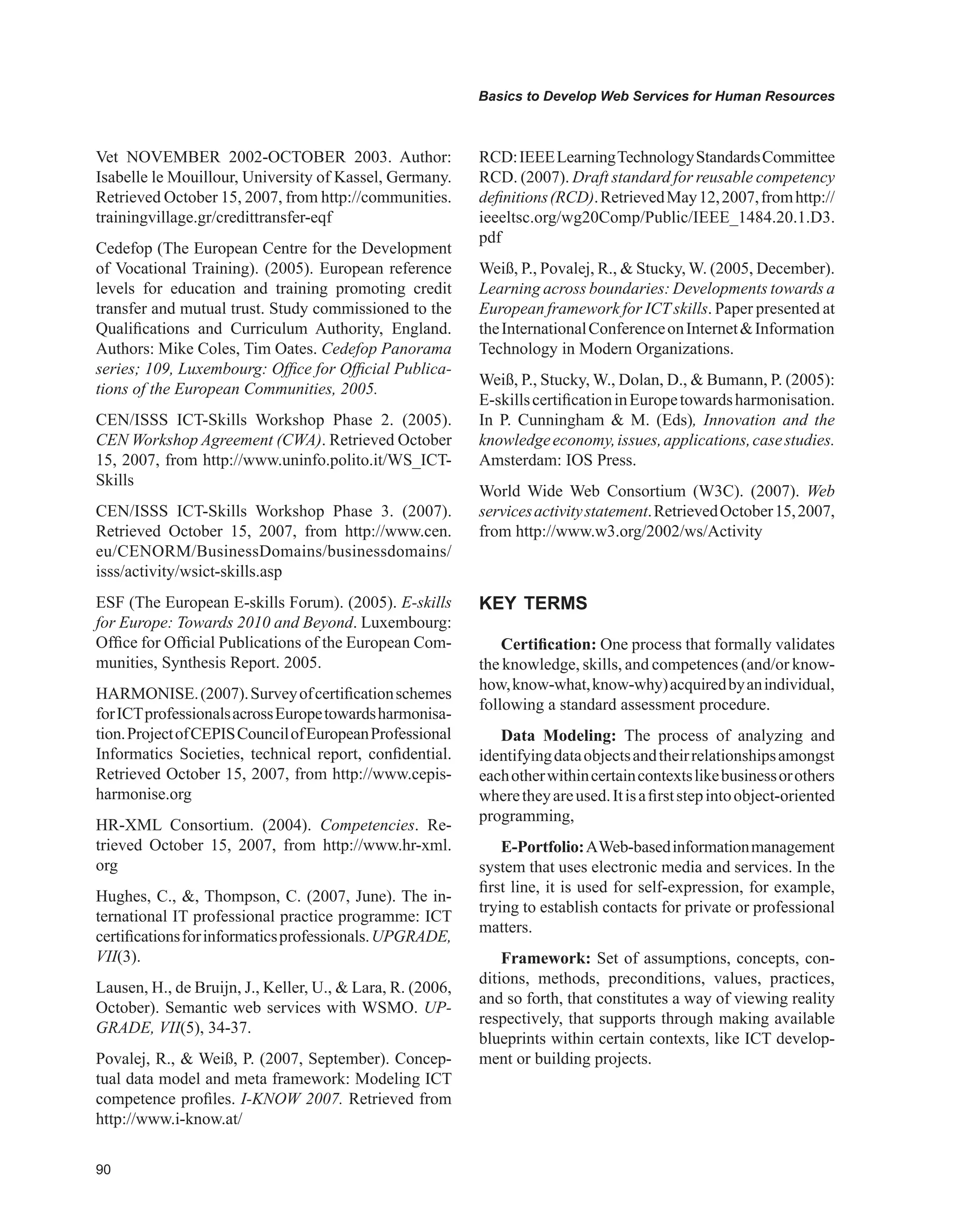

![Basics to Develop Web Services for Human Resources

B

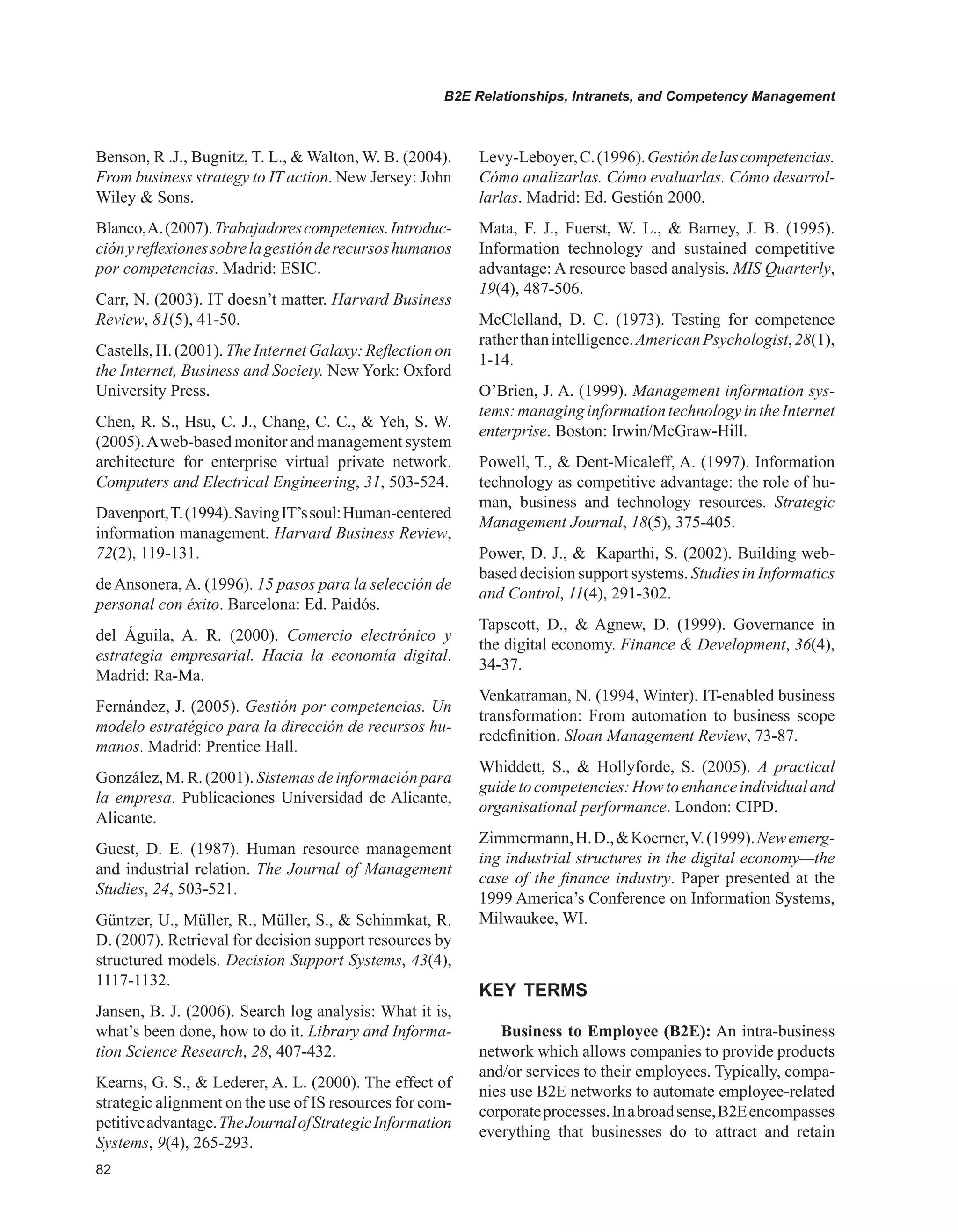

Competence-based professional profiles are a

referred concept to define and exchange information

about respective professional standards. The profile

is the description of competence required to oper-

ate on a process, on a service, or for a definite role,

inside a direction or a function, a working team, or a

project. It shows as much explicit as possible which

type of know-how needs an organization has in terms

of competence. In a most diffused configuration, the

competence based profile is defined with reference to

an organizational position or role. The competence

based profile of a role has to be built up without any

reference to single persons that occupied this role or

are candidates to cover the role in the future.

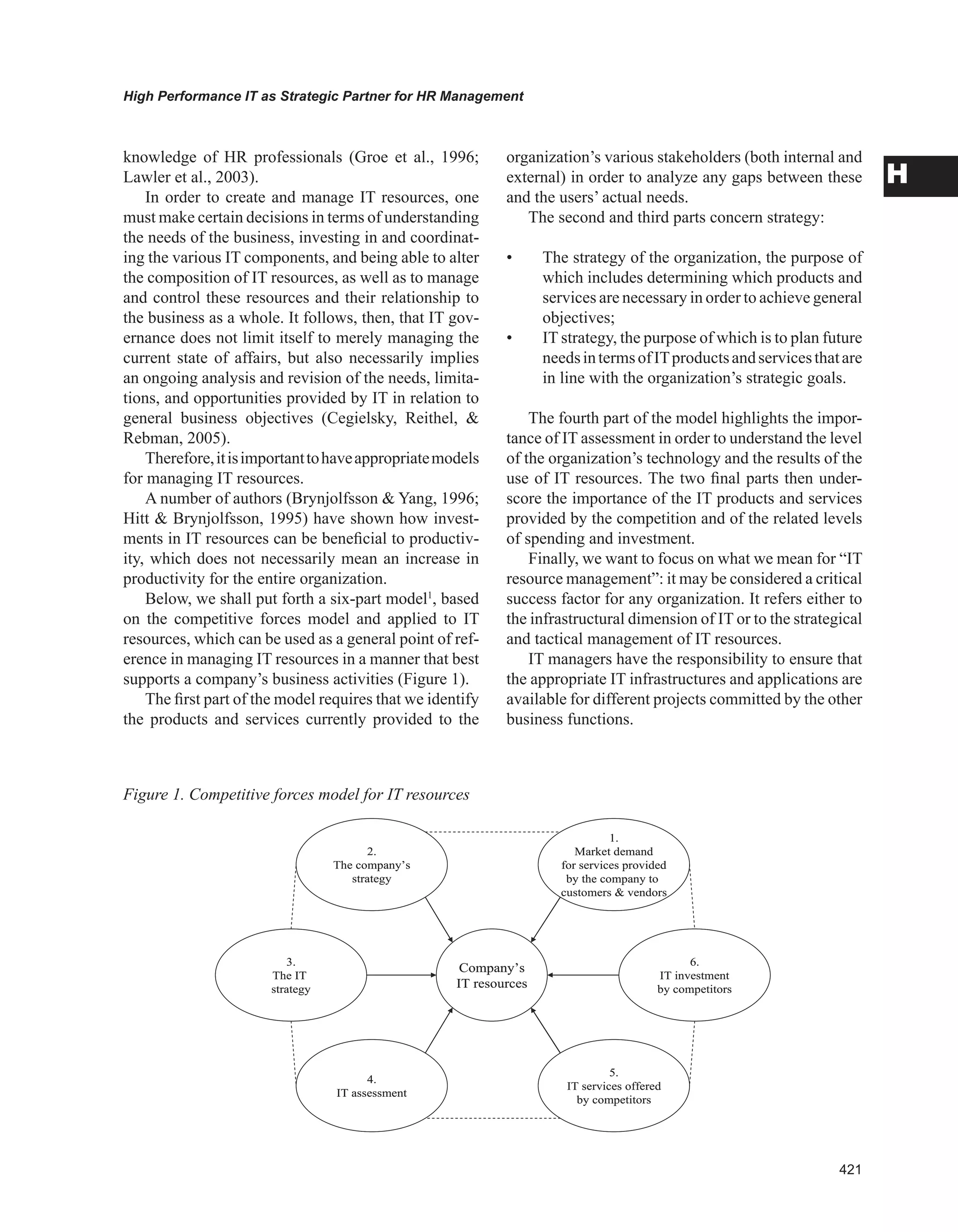

In the following, the article looks at a common

language and ICT worker profiles as a constituent part

and central element of an adequate management of HR

processes in general and CPD processes specifically.

The article presents a conceptual model which allows

expanding existing barriers of HR systems. Web ser-

vices are seen as an appropriate concept to implement

required functionality and processes.

BACKGROUND

The competitiveness of European industry depends on

boththeeffectiveuseofICTforindustrialandbusiness

processes and the KSC and qualifications of existing

and new employees (ESF, 2005).

Today, nearly every area of economic activity is

affected by ICT and the pace of technological change

and short technology life cycles makes these the most

dynamicofoccupations(Cedefop,2005);scilicetcom-

panies as well as ICTemployees (and also others) have

an ongoing need to keep their KSC and qualifications

up-to-date to prevail against competitors. In respect

thereof, ICT certifications are useful to validate ICT

employees’marketvalueand oftentheyrank akeyrole

in the hiring process.

In the first place, ICT companies, but actually all

companies, employ people with ICT skills as well as

people with a range of other relevant skills. Often the

number of ICT practitioners in such ICT user organi-

zations (e.g., banks, manufacturing companies, and

airlines) is greater than the number employed in ICT

companies.

New competency-based systems of certification

of individual employees and/or others were, are, and

further on, will be established within the information

technology field and offered on the market; this is

mainly driven by ICT vendors, the expected profit is

highly valued.

Competence encompasses “[…] the demonstration

of relevant, up-to-date skills and capabilities appropri-

ate to a particular task or role with practical experience

to complement theoretical knowledge” (Hughes

Thompson,2007).Thisincludesaswell,necessarysoft

skills such as inter-personal and communication skills

aswellasanunderstandingofthebusinessdomain.We

argue that performance components are an adequate

means to develop necessary skills and to avoid that

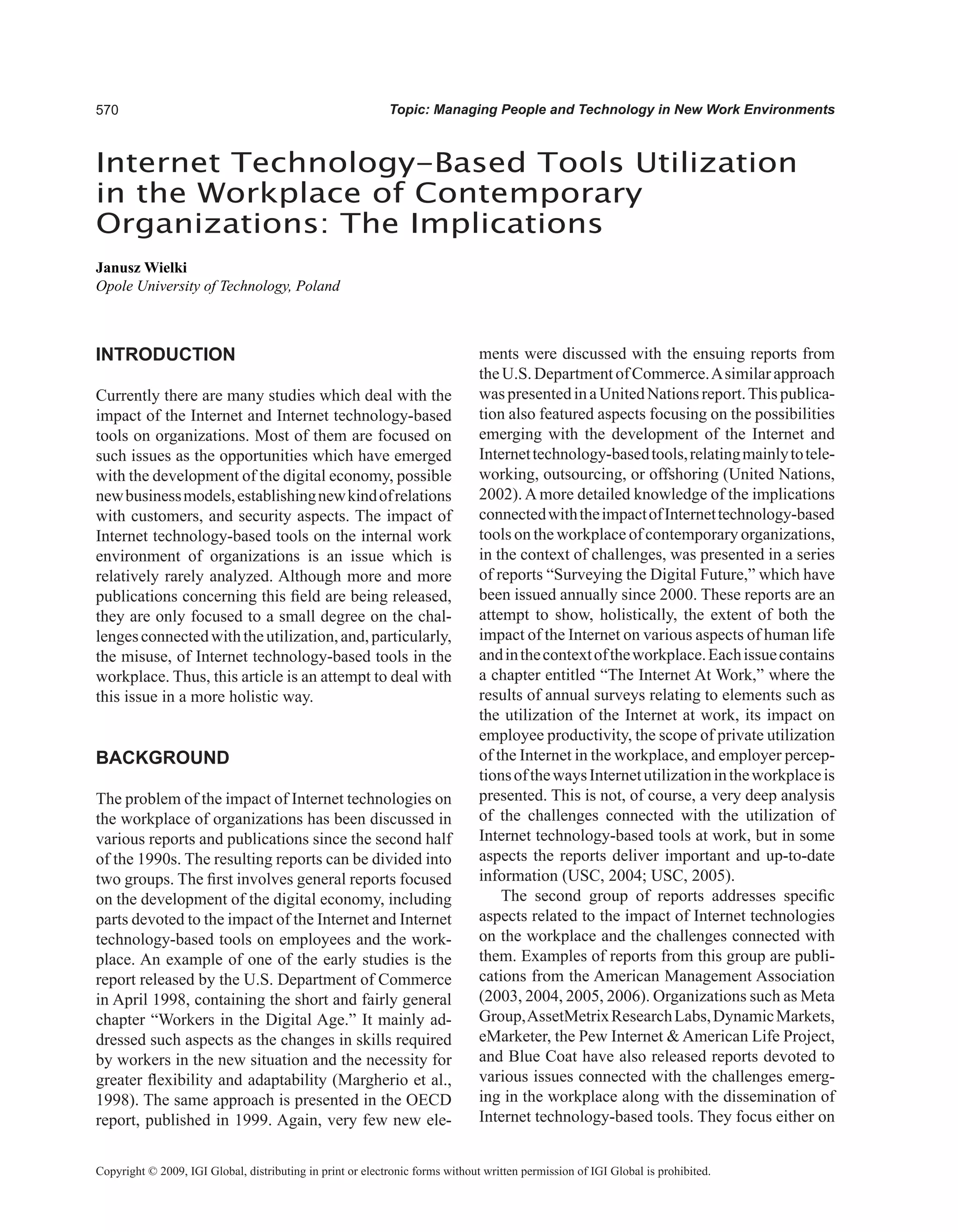

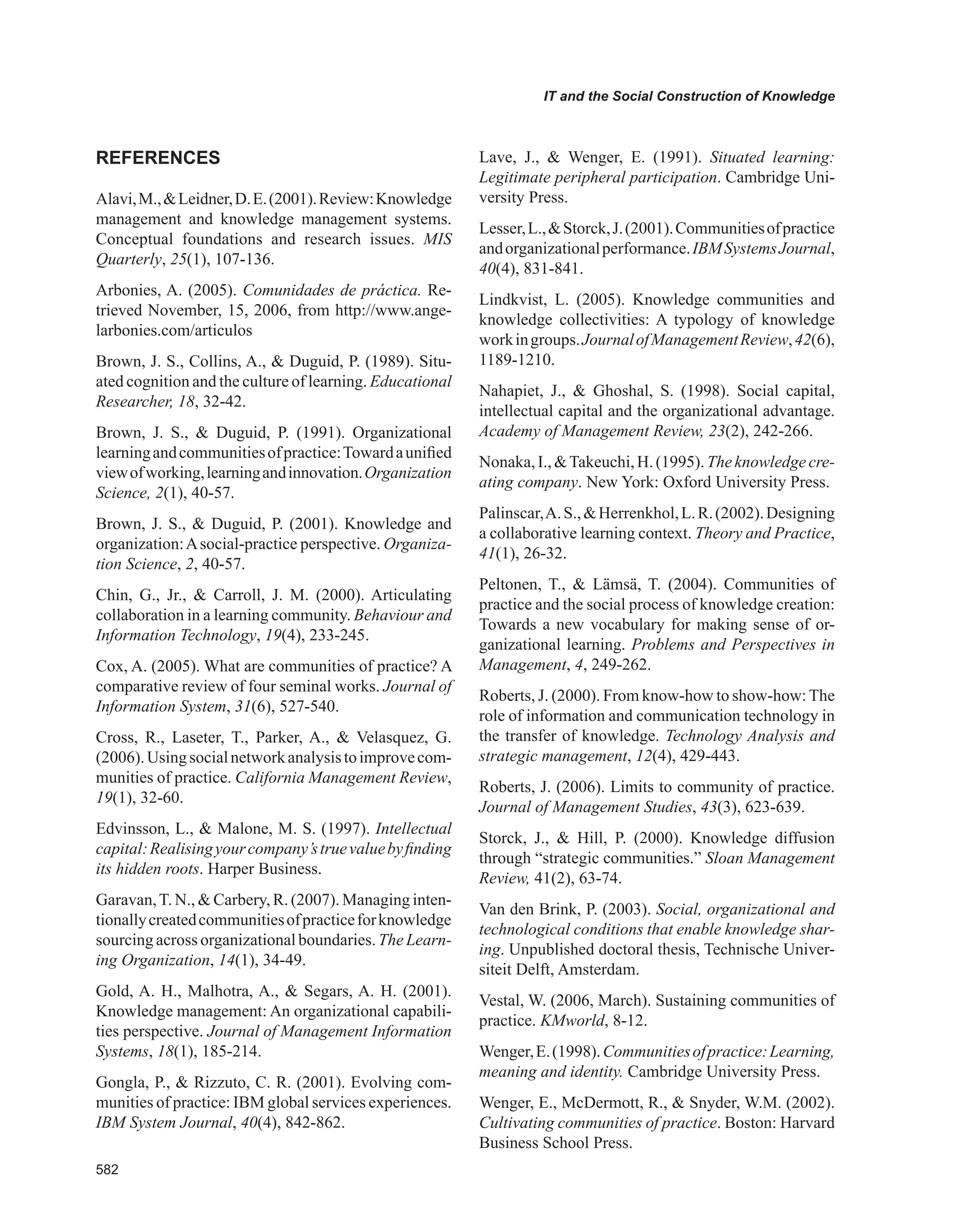

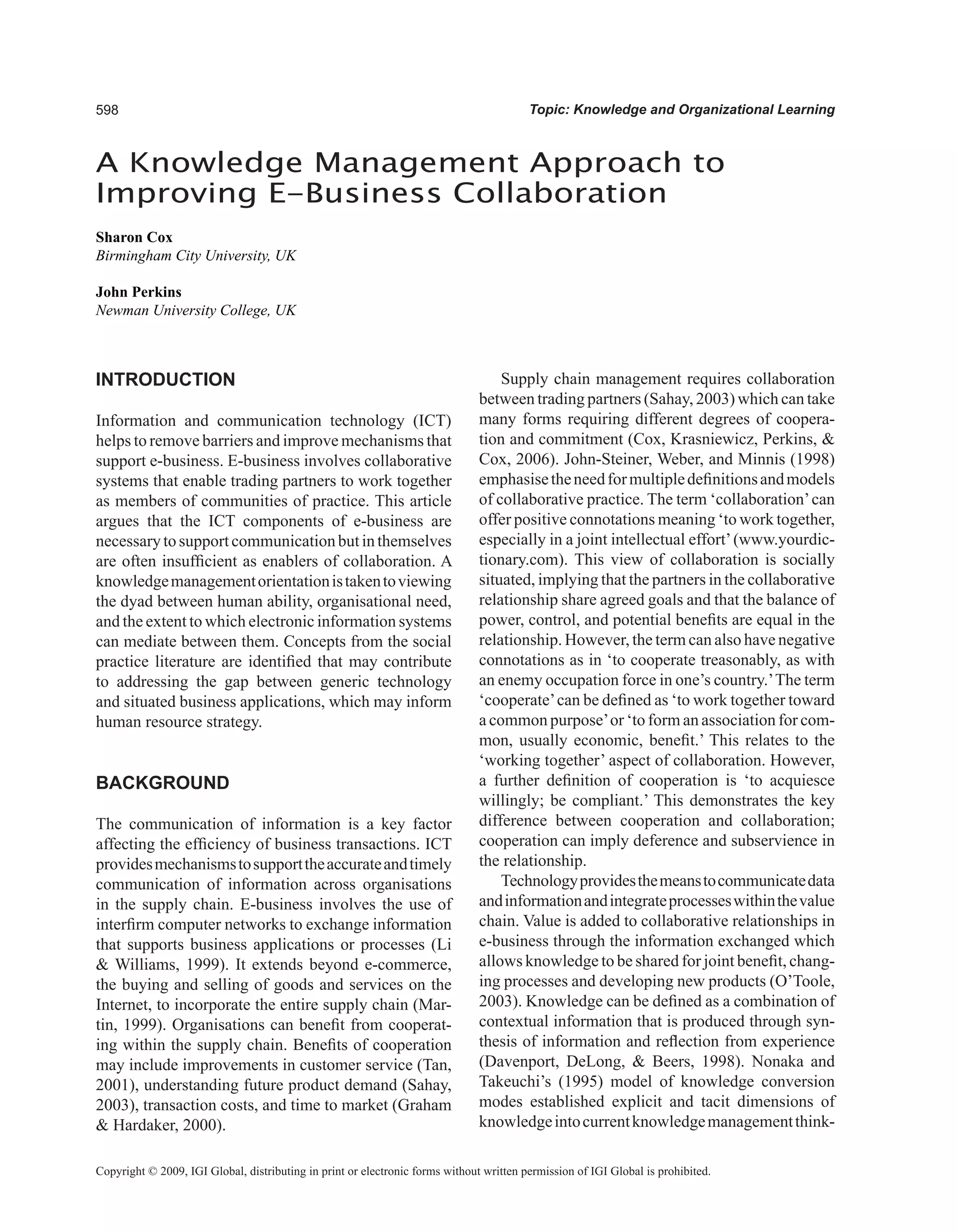

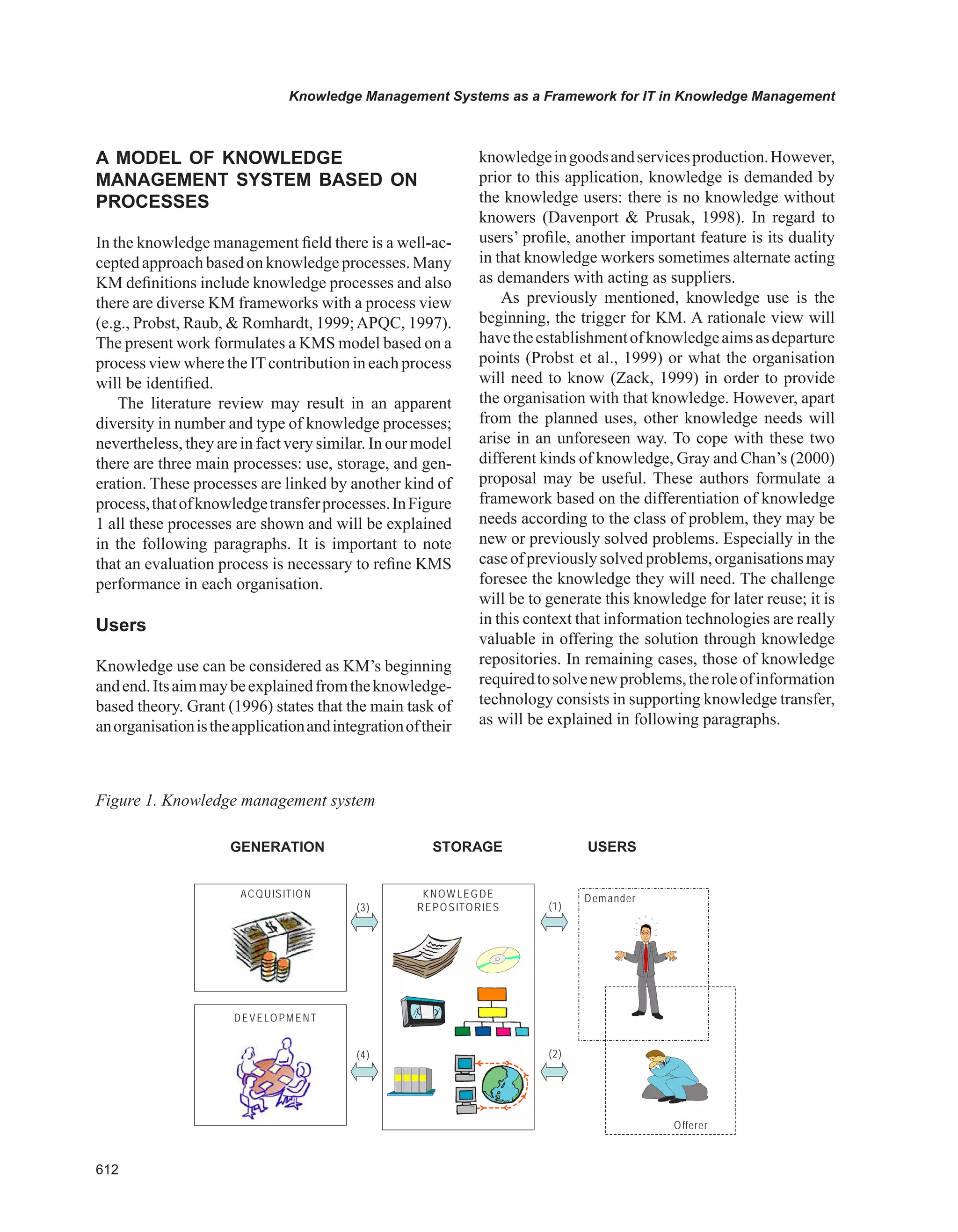

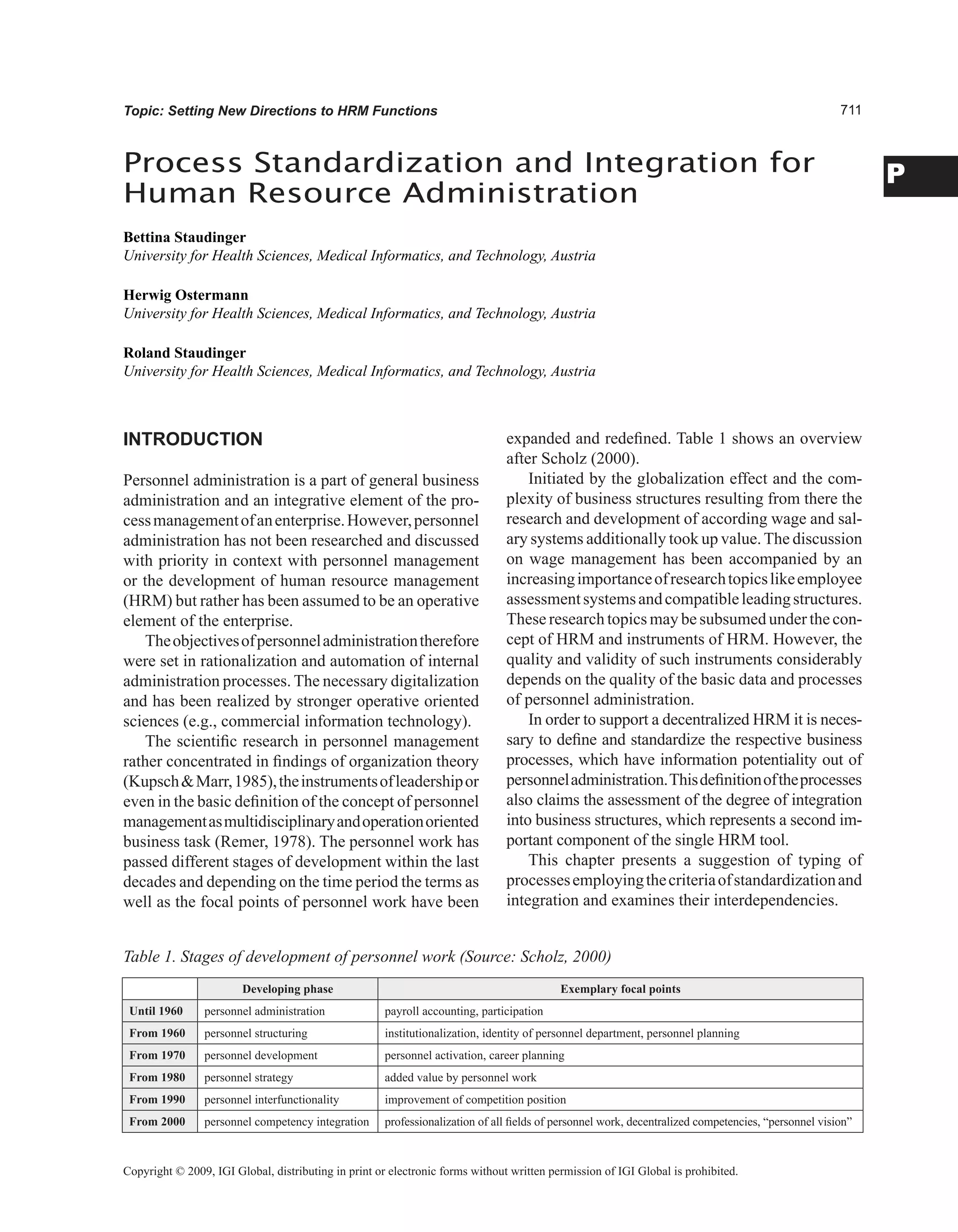

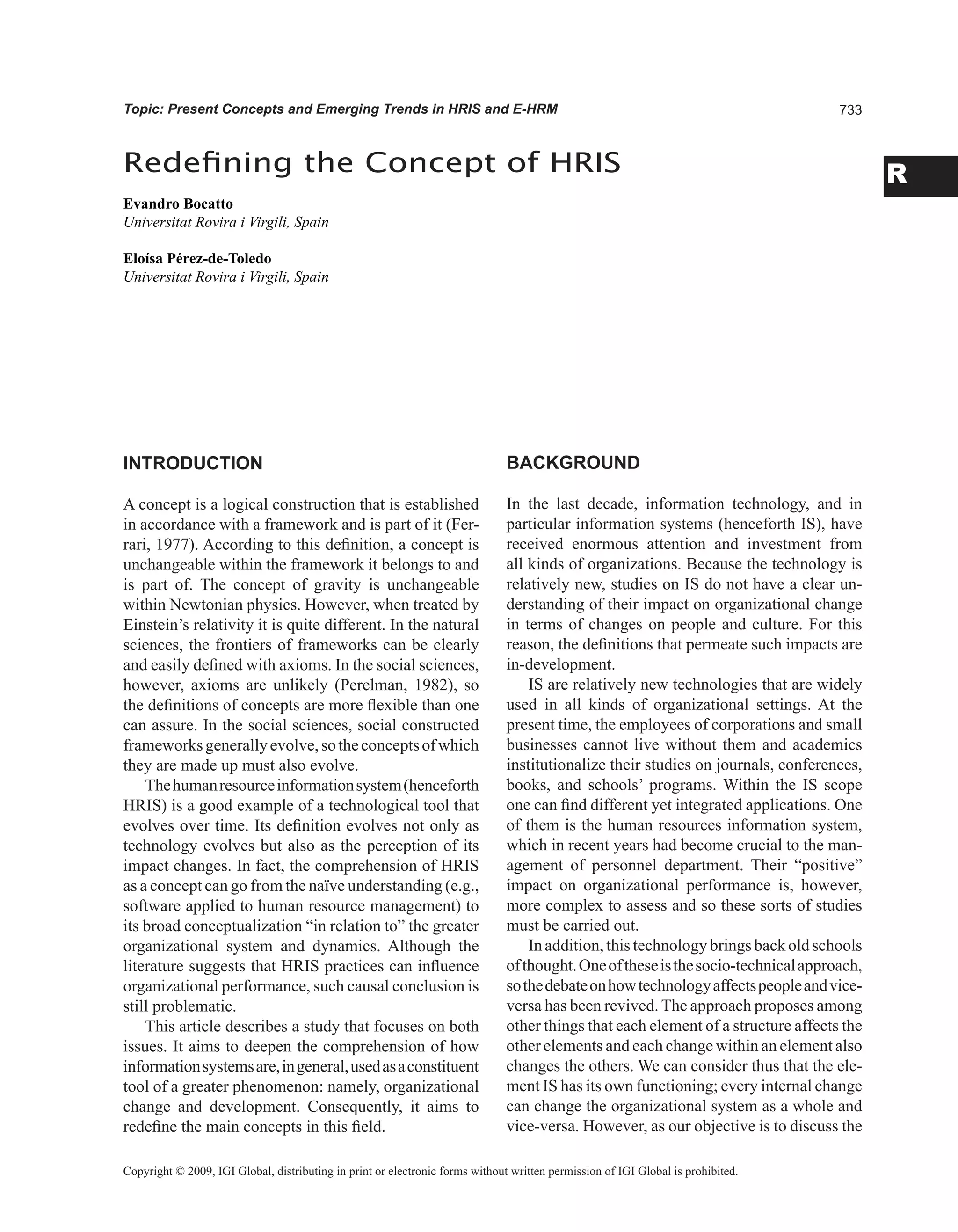

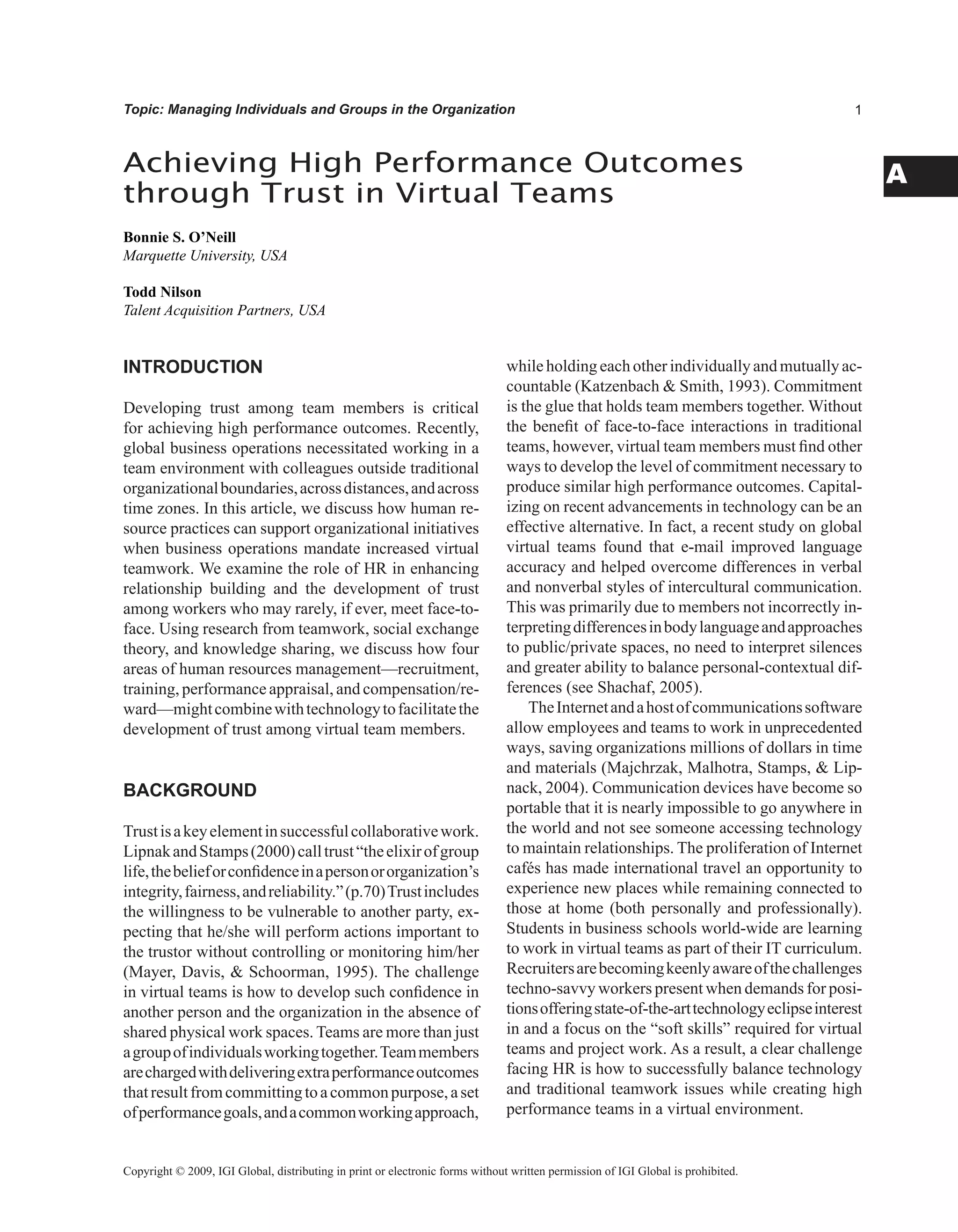

qualification measures coincide. Figure 1 shows the

supply and demand of e-skills.

E-skills present a mainly political driven joint

initiative of stakeholders in Europe such as the Euro-

peanCommission,ICTprofessionalsassociations,and

international ICTvendor industry associations. Subse-

quently, we argue why e-skills require joint activities

and concerted actions.

Each stakeholder determines their own needed and

relevant e-skills requirements (profile A). Education

institutions determine their curricula (profile B) which

consistofe-skillswhichshouldbetaughttothestudents.

Industryandemployersdeterminetheire-skillsrequire-

ments (profileA) to manage their tasks and challenges

in the economy. Sometimes the requirements of these

two groups do not exactly match, for example, parts

of the curricula are in general concepts, methods, and

tools about databases; however, the industry demands

product-related knowledge about a specific database,

often they do not notice that the parts of the curricula

will be actual on the long run, whereas product-related

knowledgeaboutonespecificdatabasecouldbeshortly

unusable,becausethebelongingsoftwareproductisno

longer offered and used.After education, every person

becomes part of the e-skills stock (profile C) with their

ownportfolio(profileD),andwiththeirparticipationat

the labor market they build the e-skills supply (profile

C+D). The relevant job profiles are managed within

companies’skills framework (profileA’) and are influ-

enced by the e-skills requirements (profile A), e-skills

stocks (profile C and profile D), and e-skills supply

(profile C+D). It is a big challenge to compare and/or

to match these (job) profiles (profile A, B, C, D, C+D,

A’) among themselves because of lack of a common

language. The degree of difficulty is much higher on

the European level.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-128-2048.jpg)

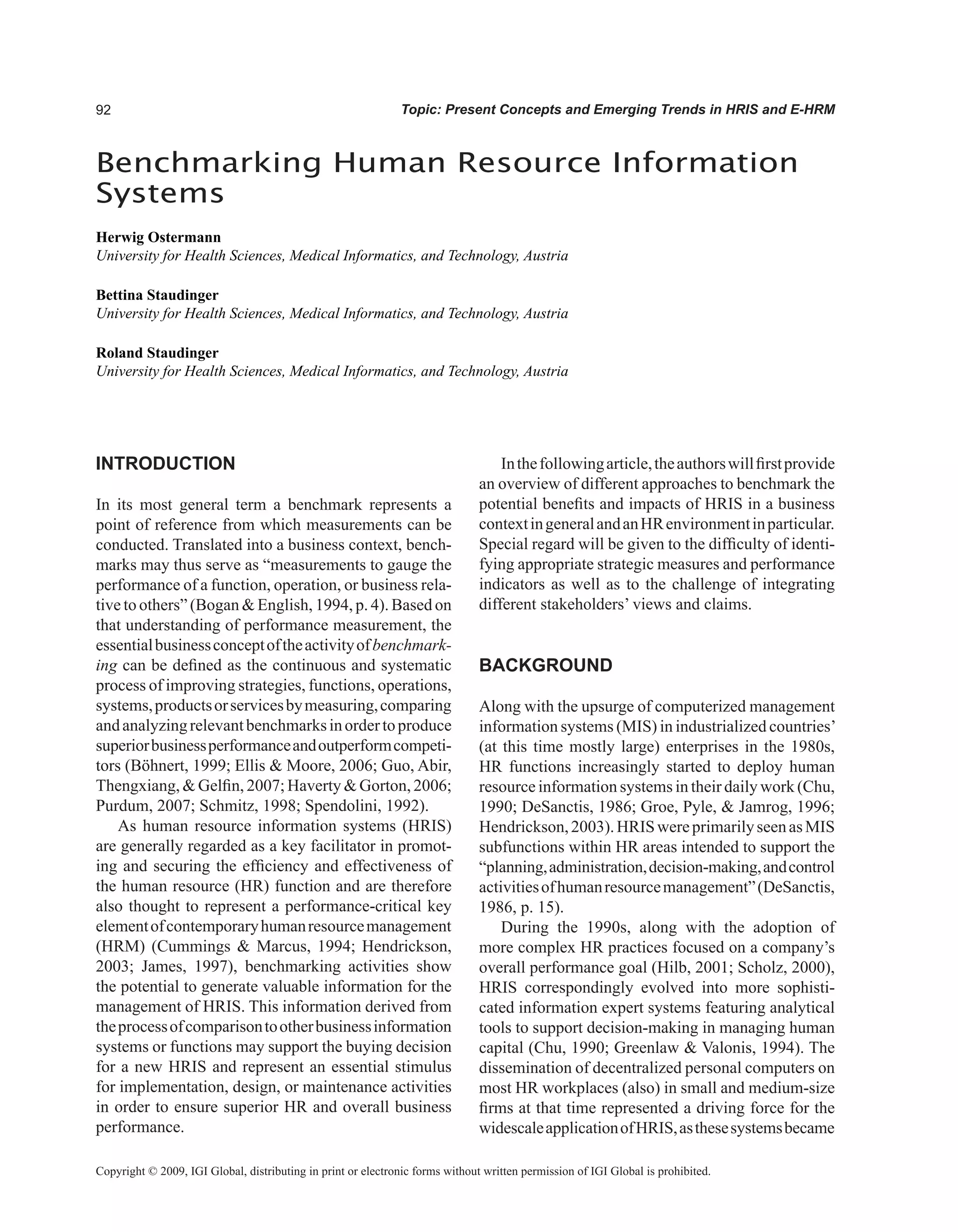

![00

Benchmarking Human Resource Information Systems

Haux, R., Winter, A., Ammenwerth, E., Brigl, B.

(2004).Strategicinformationmanagementinhospitals:

An introduction to hospital information systems. New

York: Springer.

Haverty, M., Gorton, M. (2006). Integrating market

orientation and competitive benchmarking: A meth-

odological framework and application. Total Quality

Management Business Excellence, 17, 1077-1091.

Hendrickson, A. R. (2003). Human resource informa-

tion systems: Backbone technology of contemporary

human resources. Journal of Labor Research, 24(3),

381-394.

Hilb, M. (2001). Integriertes Personal-Management

(9th

ed.). Neuwied: Luchterhand.

Howes, P., Foley, P. (1993). Strategic human re-

source management:AnAustralian case study. Human

Resource Planning, 16(3), 53-64.

James, R. (1997). HR megatrends. Human Resource

Management, 36, 453-463.

Kämpf,M.,Köchel,P.(2004).EinOptimierungsmo-

delfürProduktions-undLagerhaltungsnetze.Retrieved

November 15, 2006, from http://www.tu-chemnitz.

de/informatik/HomePages/ModSim/Publikationen/

pko_mkae_04_2.pdf.

Kanthawongs, P. (2004). Does HRIS matter for HRM

today? Retrieved October 15, 2006, from http://www.

bu.ac.th/knowledgecenter/epaper/jan_june2004/pen-

jira.pdf.

Kappler, E. (1995). Was kostet eine Tasse? Oder:

Rechnungswesen und Evolution. In E. Kappler T.

Scheytt (Eds.), Unternehmensführung—Wirtschafts-

ethik--Gesellschaftliche Evolution (pp. 297-330).

Gütersloh: Bertelsmann.

Kappler, E. (1975). Zielsetzung und Zieldurchset-

zungsplanung in Betriebswirtschaften. Wiesbaden:

Gabler.

Kovach, K. A., Cathcart, C. E. (1999). Human

resource information systems (HRIS): Providing busi-

ness with rapid data access, informationexchange, and

strategic advantage. Public Personnel Management,

28, 275-282.

Kunstelj,M.,Vintar,M.(2004).Evaluatingtheprog-

ress of e-government development: A critical analysis

[Electronic version]. Information Polity, 9, 131-148.

Lengnick-Hall, C.A., Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2006).

HR, ERP, and knowledge for competitive advantage.

Human Resource Management, 45, 179-194.

Morrish,K.(1994).Navigatinghumanresourcebench-

marking: A guide for human resource managers. Re-

trievedOctober15,2006,fromhttp://www.dpc.wa.gov.

au/psmd/pubs/wac/navbench/benchmk.pdf

Ostermann,H.,Staudinger,R.(2005).Benchmarking

E-Government: Formale Aspekte der Anwendbarkeit

unter Berücksichtigung differenzierter Zielsetzungen.

Wirtschaftsinformatik, 47, 367-377.

Preparing to measure HR success. (2002). HRfocus,

79(12), 1 and 11-14.

Purdum, T. (2007). Benchmarking outside the box.

Industry Week, 256(3), 36-38.

Puxty, A. G. (1993). The social and organizational

context of managerial accounting. London:Academic

Press.

Rampton, G. M., Turnbull, I. J., Doran, J.A. (1999).

Human resource management systems:Apractical ap-

proach (2nd

ed.). Scarborough, Ontario: Carswell.

Roberts, B. (2006). New HR systems on the horizon.

HR Magazine, 51(5), 103-111.

Roehling,M.V.etal.(2005).ThefutureofHRmanage-

ment:Researchneedsanddirections.HumanResource

Management, 44, 207-216.

Schmitz, J. (1998). Prozessbenchmarking: Methodik

zur Verbesserung von Geschäftsprozessen. Controller

Magazin, 22, 407-415.

Scholz, C. (2000). Personalmanagement (5th

ed.).

München: Vahlen.

Shih, H. A., Chiang, Y. H. (2005). Strategy align-

ment between HRM, KM, and corporate development.

International Journal of Manpower, 26, 582-603.

Spendolini,M.J.(1992).Thebenchmarkingbook.New

York: American Management Association.

The best HR software now. (2001). HRfocus, 78(3),

11-13.

Thomas, S., Skitmore, M. A., Sharma, T. (2001).

TowardsahumanresourceinformationsystemforAus-

tralianconstructioncompanies.Engineering,Construc-

tion and Architectural Management, 8, 238-249.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-143-2048.jpg)

![Collaboration Intricacies of Web 2.0 for Training Human Resource Managers

characters. Educational Uses of Second Life describes

severaloftheinnovationsthatareoccurring“in-world.”

One notable event was the presentation by actress Mia

Farrow and John Heffernan, Director of the Genocide

prevention Initiative for the U.S. Holocaust Memorial

Museum’s Committee on Conscience, who both spoke

atanin-worldbriefingongenocide.In-worldeventsare

sometimes videotaped and shared to an even broader

audience on services like Google and YouTube™

.

Some companies, such as Thompson NetG, actually

conductMicrosoftcertification,businessdevelopment,

and sales training in a virtual classroom (“educational

uses”). There are also virtual campuses in Second Life

devoted to demonstrations and exhibitions, such as

Cybrary City and New Media Consortium Campus.

Other features of Second Life include the International

Spaceflight Museum,Alzheimer’exhibit, a virtual hal-

lucination room, the S P 500 graphical depiction, a

virtual Morocco, as well as recreations of other cities

both ancient and present (“educational uses”). Virtual

worldslikeSecondLifemaybecomeevenmoreimpor-

tant as the Web itself engages in a 3D metamorphosis.

On a related note, Palmisano of IBM has announced

a project to construct a 3D internet premised on the

interactivity within Second Life (Kirkpatrick, 2007),

an initiative which may bringWeb 2.0 by force into the

hands of a large number of personal computer users.

One cautionary note regarding virtual environments

(particularlyonesthatorganizationsrequireindividuals

to join), is the potential harm that can result to one’s

avatar through violence, harassment, or assault (for a

full description, see Bugeja (2007)).

CONCLUSION

Web 2.0 is not just about technology, for the very basis

of its applications is driven by a sense of community.

AJAXWorld (2005, para. 5) states that it is people cen-

tered: “Web 2.0 fundamentally revolves around us and

seekstoensurethatweengageourselves,participateand

collaboratetogether,andmutuallytrustandenricheach

other, even though we could be separated by the entire

worldgeographically.”Withpeopleasitscentralfocus,

Web 2.0 tools and virtual worlds in particular serve a

verybasichumanneed-thatofconnection,acceptance,

and social outlet. Human resource managers who take

notice of and incorporate these tools into their training

sessions may reap the benefits of a more united and

more cohesive work unit. With 65 and 62.5 percent of

higher educational institutions offering graduate and

undergraduate online as well as face to face courses

respectively (Allen Seaman, 2005) the potential to

incorporate a plethora of tools that create community

early in students’ careers is immense. Their degree of

exposure may ultimately determine their receptivity

and later eagerness to embrace these technologies in

the working environment.

REFERENCES

AjaxWorld News Desk. (2005). Five reasons why

Web 2.0 matters. Retrieved June 18, 2007, from SOA

WorldMagazineWebsitehttp:///webservices.sys-con.

com/read/161874.htm

Allen, I. E., Seaman, J. (2005). Growing by degrees:

Online education in the United States. Retrieved No-

vember15,2007,fromhttp://www.sloan-c.org/publica-

tions/survey/pdf/growing_by_degrees.pdf

Beck, J. C., Wade, M. (2004). Got game: How the

gamergenerationisreshapingbusinessforever.Boston:

Harvard Business School Press.

Berners-Lee, T. (1998). The world wide Web: A very

short personal history. Retrieved June 21, 2007, from

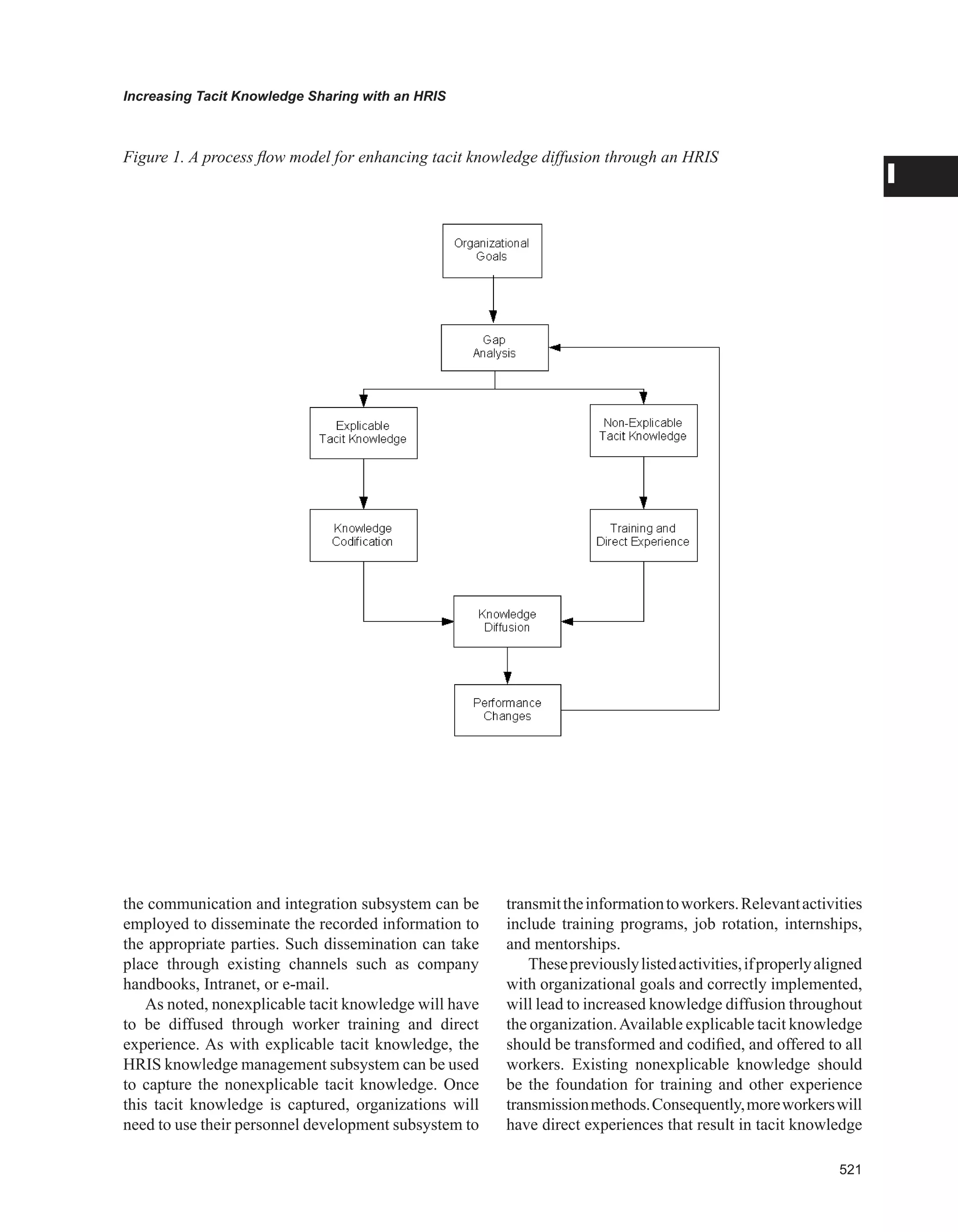

http://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/ShortHistory.

html

Bridges, W. (1994, September 19). The end of the job.

Fortune, 130, 62-74.

Bugeja, M. J. (2007, September 14). Second thoughts

about Second Life [Electronic version]. The Chronicle

of Higher Education, 54, C1-C4.

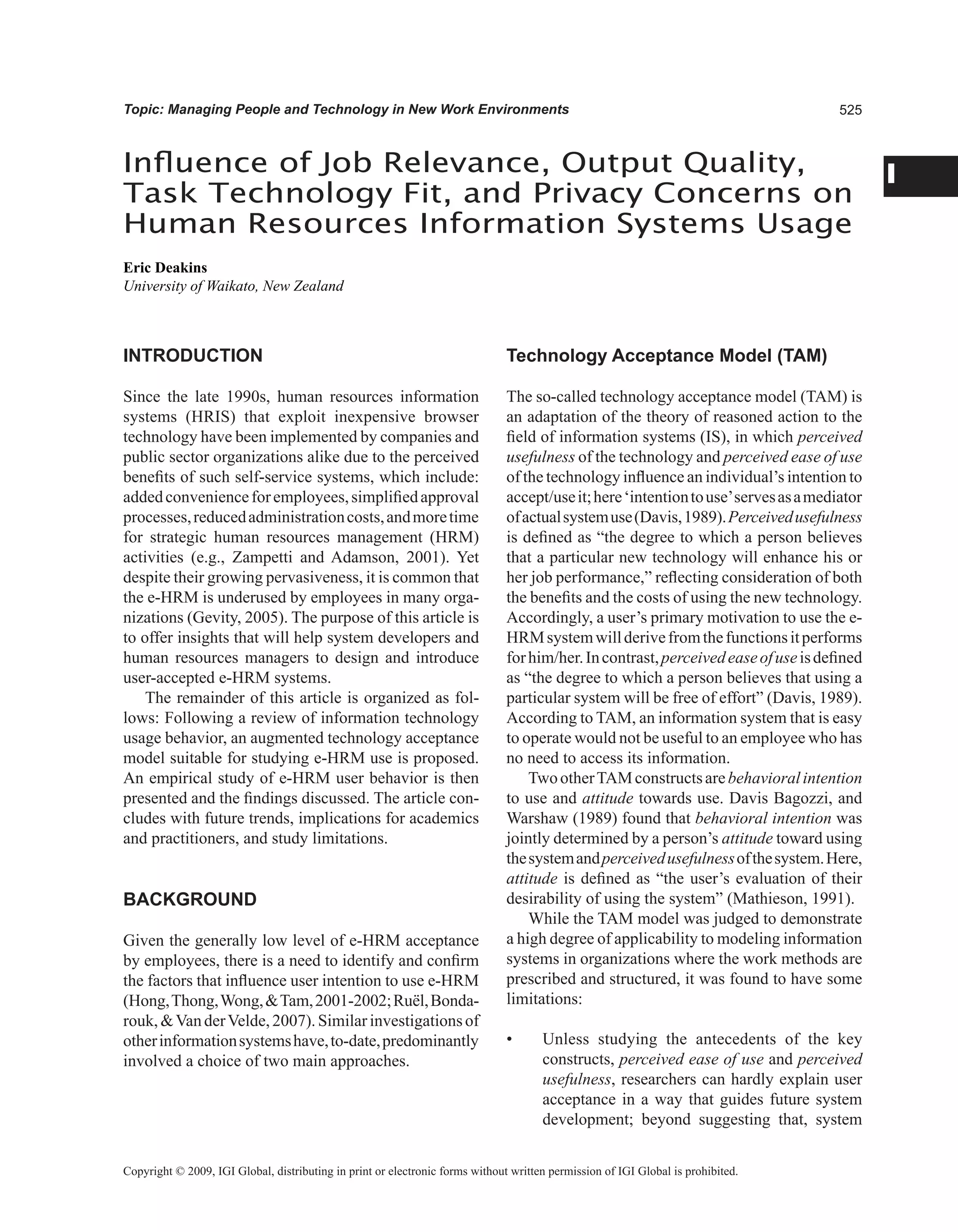

CooperativeLearning.(n.d.).RetrievedJune18,2007,

from http://edtech.kennesaw.edu/intech/cooperative-

learning.htm

Davis, V.A. (2006). The web 2.0 classroom. Retrieved

June 18, 2007, from http://k12online.wm.edu/Web-

20classroom.pdf

Downes, S. (2006). E-learning 2.0. Retrieved June

18, 2007, from http:///www.elearnmag.org/subpage.

cfm?section=articlesarticle=29-1

Educational uses of Second life. (n.d.). Retrieved June

20,2007,fromhttp://sleducation.wikispaces.com/edu-

cationaluses](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-177-2048.jpg)

![Collaboration Intricacies of Web 2.0 for Training Human Resource Managers

C

Fisher, A. (2005, March 7). Starting a new job? Don’t

blow it [Electronic version]. Fortune, 151, 48.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., Archer, W. (2000).

Criticalinquiryinatext-basedenvironment:Computer

conferencing in higher education. The Internet and

Higher Education, 2, 87-105.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T. (1998). Cooperative

learningandsocialinterdependencetheory.Retrieved

November 15, 2007, from http://www.co-operation.

org/pages/SIT.html

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T. (1989). Cooperation

and competition: Theory and research. Edina, MN:

Interaction Book Company.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. (2007). Fortune on Second Life. Re-

trievedApril17,2007,fromhttp://bgnonline.blogspot.

com/2007/01/fortune-on-second-life.html

O’Reilly, T. (2005). What is web 2.0: Design pat-

terns and business models for the next generation of

software. Retrieved June 18, 2007, from http://www.

oreilly.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-

is-web-20.html

Raelin, J.A. (2003). Creating leaderful organizations:

Howtobringoutleadershipineveryone.SanFrancisco:

Berrett-Kohler Publishers, Inc.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory

for the digital age. Retrieved November 15, 2007,

from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectiv-

ism.htm

Van Eck, R. (2007, April). Generation G and the 21st

century:Howgamesarepreparingtoday’sstudentsfor

tomorrow’s workplace. Paper presented at the Middle

Tennessee State University Instructional Technology

Conference, Murfreesboro, TN.

Web 2.0 tools in your classroom. (n.d.). Retrieved June

20, 2007, from http://www.slideshare.net/markwool-

ley/web-20-tools-in-your-classroom/

Williams, A. J. (2007, February). Using web 2.0 in

your classroom (online or not). Paper presented at

the Tennessee Board of Regents Distance Learning

Conference, Nashville, TN.

Wong, G. (2006). Educators explore ‘Second Life’

online.RetrievedApril16,2007,fromhttp://www.cnn.

com/2006/TECH/11/13/second.life.university/

TERMS AND DEFINITIONS

Collaboration:Aunitive effort among individuals

with the intent to share, create, and display informa-

tion.

Connectivity: With regard to human participants

in an “e-world,” this term refers to the linkages cre-

ated by access and usage of Web 2.0 tools, in which an

electronic community of participants is formed.

Cooperative Learning: A teaching strategy in

which students work together (either in pairs or in

groups) to master a particular lesson.

“G-Generation”: Individuals born in the 1980s

and 1990s (Van Eck, 2007), who use Web 2.0 tools

and digital gaming with ease and on a routine basis.

They are suggested as a group to be highly adaptable

to new situations, good problem solvers, and effective

team players (Van Eck, 2007).

SecondLife:Athreedimensionaluniverseinwhich

avatars can transact business, meet one another, and

purchase user created electronic objects (along with

pieces of virtual land) using Linden dollars.

Virtual Worlds: Three dimensional electronic

recreations of physical spaces, in which users can

interact via an “avatar” with other users, and engage

in a wide range of activities that are user orchestrated

and maintained.

Web 1.0: The first incarnation of the internet, used

forgatheringinformationonvarioustopics.Thisversion

was used by the government and educational institu-

tions,wheretheemphasiswasonindividualsearching,

as opposed to dynamic and interactive contribution

capabilities.

Web 2.0: The conception of the Web as a large,

everchangingrepositoryofusercontributedandedited

content. This version of the Web is “living,” in that it

continually changes in response to user input, such as

wikis, blogs, and social networking.

Web 2.0 Community: an electronic collection of

individuals who proactively participate in the creation

and editing of their resources.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-178-2048.jpg)

![Collaborative Technologies, Applications, and Uses

C

A Common Attachment to Cooperation…

Besidesthispermanentconcerntoputtheuserintheheart

of the design process, the multitude of articles attached

to CSCW share a common attachment to the notion of

cooperation. It is this which has enabled them to differ-

entiatethemselvesfromthetwopre-existing disciplines:

the study of information systems on the one hand (office

automation,managementinformationsystemorIS)and

on the other hand the design applications intended for

individual computers (human computer interaction or

HCI). While the discipline of information systems is

working on the design of the “large” systems for firms

(company servers, electronic data interchanges [EDI],

reservation, command, or transaction software between

customerandsupplier),theHCIdisciplineisinvolvedin

thedesignofcomputertoolswhichareusedtoconstructa

dialoguebetweenanindividualandanisolatedmachine.

Compared with these two disciplinary “monsters,” the

CSCWhasmadeanefforttooccupyadomainwhichboth

ofthemperceivedbadly:theorganizationofcooperation

of small (and medium) groups of people who work in

networks or in project groups (Cardon, 1997).

…But a (Too Much) wide Spectrum of

works

Beyond this common attachment for the instrumenta-

tion of cooperation in groups, the growing inflation of

articles in this discipline leads to a very wide diversity

in the scientific work, the machines, and the software.

Thus,itisdelicatetoproposeatypologywhichputsorder

into this diversity. However, Cardon (1997) proposes to

organize all collaborative technologies by using three

complementary variables:

• time (synchronous/asynchronous),

• space (in presence/remote; room/office),

• and the different representation and visualization

techniques (i.e., audio/photo/video, board/com-

puter screen/video monitor/virtual reality).

Using these variables, he distinguishes seven sets of

different technologies:

1. Shared design spaces: for example, Videodraw,

TeamWorkStation.

2. Mediaspaces:Collab,Videowindow,Thunderwire

(audiospace).

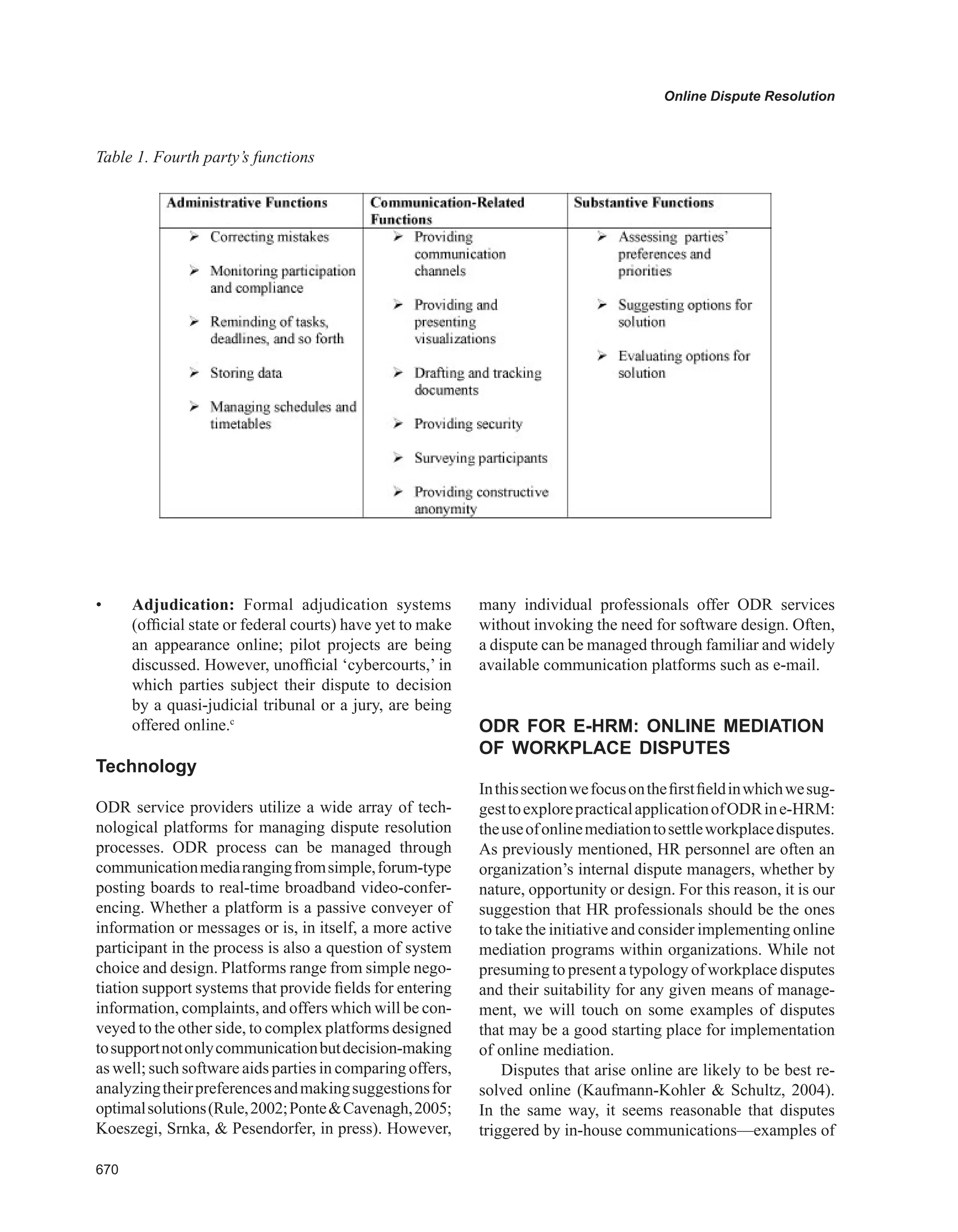

3. Asynchronous cooperative tools: Lotus Notes,

LinkWork, Coordinator

4. Cooperative PC: Cruiser, Piazza, Forum.

5. Electronic tables: LiveBoards, Smart.

6. Electronicmeetingsystems:Colab,Groupsystems,

Dolphin.

7. Virtual environments: Dive, Massive, Freewalk.

As with all kinds of typologies, the latter is open

to discussion. It would, however, seem that it may be

used to come to terms with the diversity of the techni-

cal innovations produced in the domain. Its usefulness

does, however, derive more from the examples that it

gives which may be used to illustrate the field of this

discipline than its comprehensive character. Indeed, it

seemed unprofitable to us—and perhaps even impos-

sible—to propose a typology which might attempt to

organize artificially a production which is from the ori-

gin marked by the multitude of specific uncoordinated

developments. The point was made above that what

really unites the works associated with the CSCW are

the common principles of the “user-centered” approach

and the support for activities of cooperation.

A RECENT ATTENTION TO

“REAL USES”

But, even if it has placed the uses at the very center of

its reflection, the CSCW talks little of “real” uses for

theirtechnologies.Indeed,theusesmentionedaboveare

moreoftenthoseofthedesignersthemselves—whotest

their tools in an attempt to improve them—or those of

specific users, often placed outside their classical work

conditions, put in the specific position of “testers” of a

technology. Indeed, if scientific works and prototypes

proliferate in the CSCW community, the successful

implantations of software remain rarer (Bowers, 1995;

Grudin, 1988; Markus Connolly, 1990; Olson Tea-

sley, 1996). This fact makes the analysis of uses more

delicate since it is known that the users positioned in a

roleof“codesigners”donothavethesamebehaviorasthe

“real”usersandthesetestsituations(evenreconstructed

or within the context of an experiment) are rather dif-

ferent to real-use situations (Bardini Horvath, 1995;

Woolgar, 1991).

On the basis of works of DeSanctis and Poole

(1994), Giddens (1984) and Orlikowski (2000) propose

a “structurational perspective on technology” which is

considered as a key point in the reflection on collabora-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-180-2048.jpg)

![0

Collaborative Technologies, Applications, and Uses

REFERENCES

Akrich, M. (1998). Les utilisateurs et les acteurs de

l’innovation. Education permanente, 134, 79-89.

Bardini,T.,Horvath,A.T.(1995).Thesocialconstruc-

tion of personal computer use. Journal of communica-

tion, 45(3), 40-65.

Bentley,R.,Dourish,P.(1995).Mediumversusmecha-

nism.Supportingcollaborationthroughcustomization.In

Proceedings of the ECSCW’95. Dordrecht: Kluwers.

Boullier, D. (2002). Les études d’usages: Entre nor-

malisation et rhétorique. Annales des communications,

57(3/4), 190-210.

Bowers, J. (1995). Making it work. A field study of a

CSCW Network. The Information Society, 11, 189-207.

Cardon,D.(1997).Lessciencessocialesetlesmachines

à coopérer. Réseaux, 85, 11-52.

David, A. (1998). Outils de gestion et dynamique du

change. Revue Française de Gestion, 120, 44-59.

DeSanctis, G., Poole, S. (1994). Capturing the com-

plexityinadvancedtechnologyuse:Adaptivestructura-

tion theory. Organization Science, 5(2), 121-147.

Giddens,A.(1984).Theconstitutionofsociety.Berkeley,

CA: University of Canada Press.

Gilbert, P. (1997). L’instrumentation de gestion [Man-

agement tooling]. Paris: Economica.

Grimand, A. (2006). Introduction: L’appropriation des

outils de gestion, entre rationalité instrumentale et con-

struction du sens. InA. Grimand (Ed.), L’appropriation

des outils de gestion. Vers de nouvelles perspectives

théoriques? (pp. 13-27). Publications de l’Université

de Saint-Etienne: Saint-Etienne.

Grudin, J. (1988). Why CSCW applications fail. Prob-

lems in the design and evaluation of organizational

interfaces. In Proceedings of the CSCW’88 (pp. 85-93).

New York: ACM/Sigchi and Sigois.

Guiderdoni,K.(2006,October).AssessmentofanHRIn-

tranetthroughmiddlemanagers’positionsanduses:How

tomanagethepluralityofthisgroupinthebeginningofan

e-HRconception.Presentedatthe1stEuropeanAcademic

Workshop on E-HRM, Twente, The Netherlands.

Haddon,L.(2003).Domesticationandmobiletelephony.

In J. Katz (Ed.), Machines that become us: The social

context of personal communication technology (pp. 43-

56). New Jersey: Transaction Publishers.

Hatchuel,A., Weil, B. (1992). L’expert et le système.

Paris: Economica.

Iribarne (d’),A., Lemoncini, S., Tchobanian, R. (1999,

June). Les outils multimédia en réseau comme supports à

lacoopérationdansl’entreprise:Lesenseignementsd’une

étude de case. In Proc. of the 2nd

Int. Conference on Uses

and Services in Telecommunications (ICUST),Arcachon.

Jouët, J. (2000). Retour critique sur la sociologie des

usages. Réseaux, 100, 486-521.

Kies, J. K., Williges, R. C., Rosson, M. B. (1998).

Coordinating computer-supported cooperative work:A

reviewofresearchissuesandstrategies.J.oftheAmerican

society for information science, 49(9), 776–791.

Lacroix,J.G.(1994).Entrezdansl’universmerveilleux

deVideoway.InJ.G.LacroixG.Tremblay(Eds.),De

la télématique aux autoroutes électroniques. Le grand

projetreconduit[Fromtelematicstoelectronichighways.

The great project revisited] (pp. 137-162). Sainte-Foy:

Presses de l’université du Québec et Grenoble/Presses

Universitaires de Grenoble.

Mallard,A.(2003,September).Followingtheemergence

of unpredictable uses? New stakes and tasks for the so-

cialsciencesunderstandingofICTuses.InProceedings

of “Good, Bad, Irrelevant – Conference on the user of

ICTs, Helsinki (Cost 269, pp. 10-20).

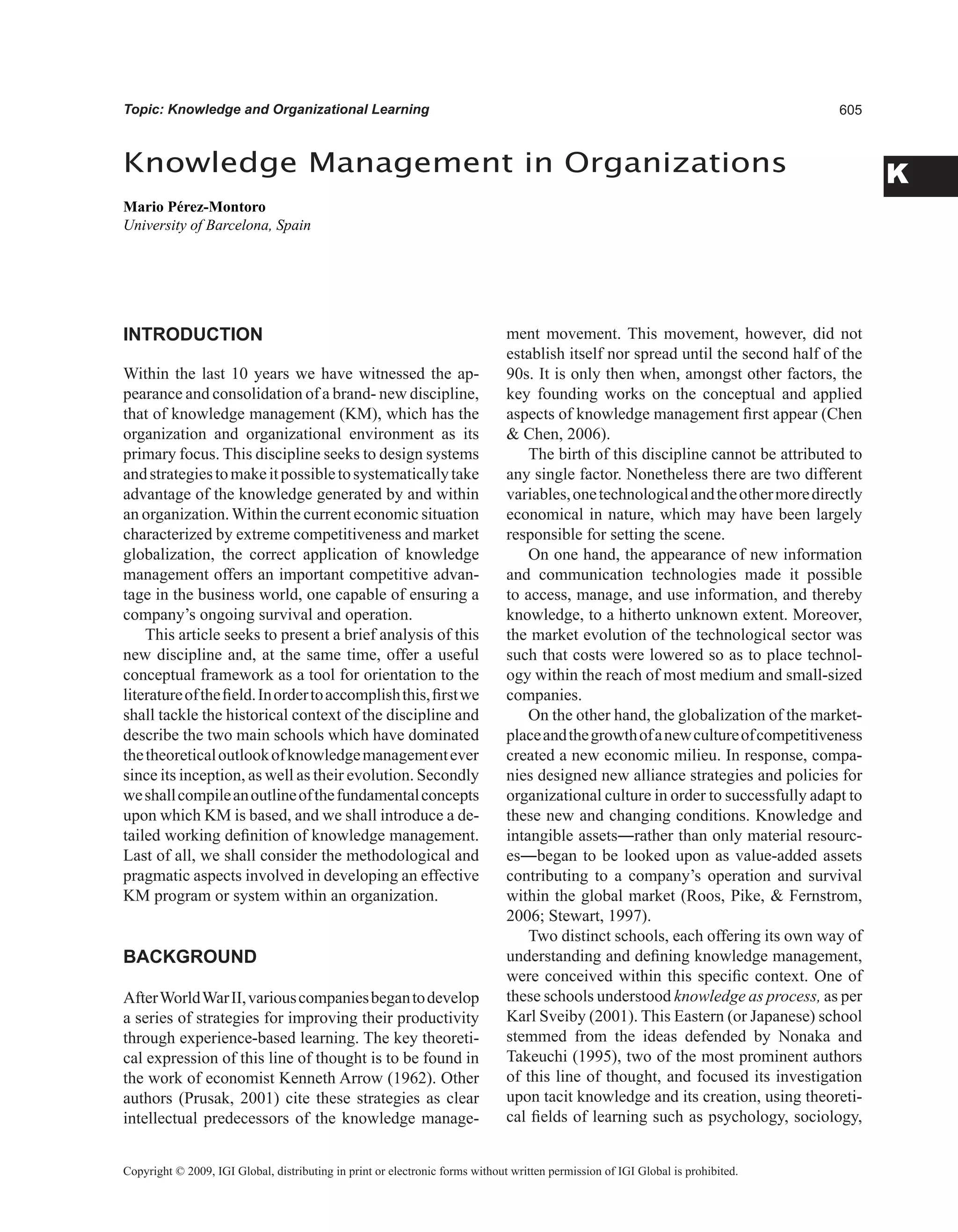

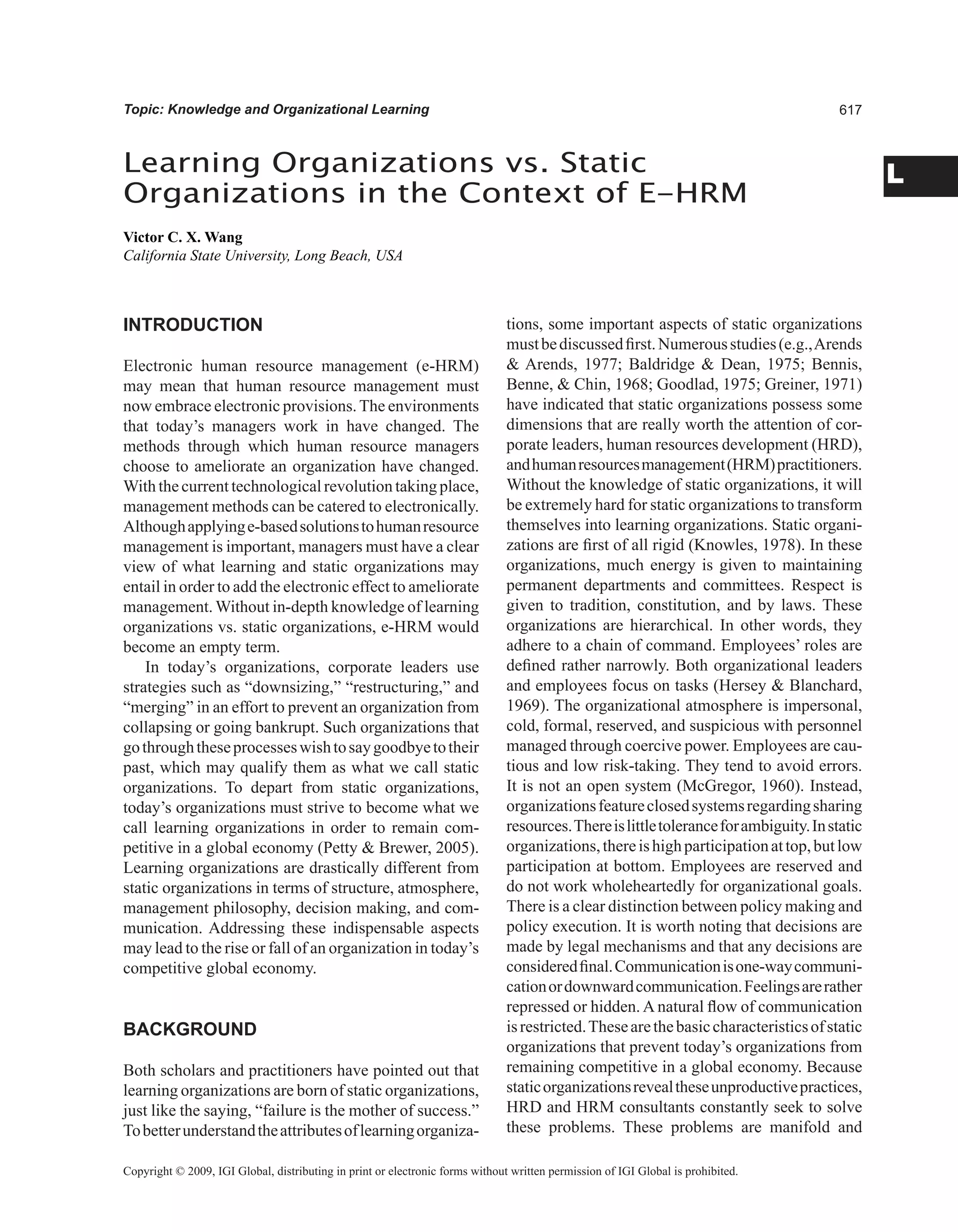

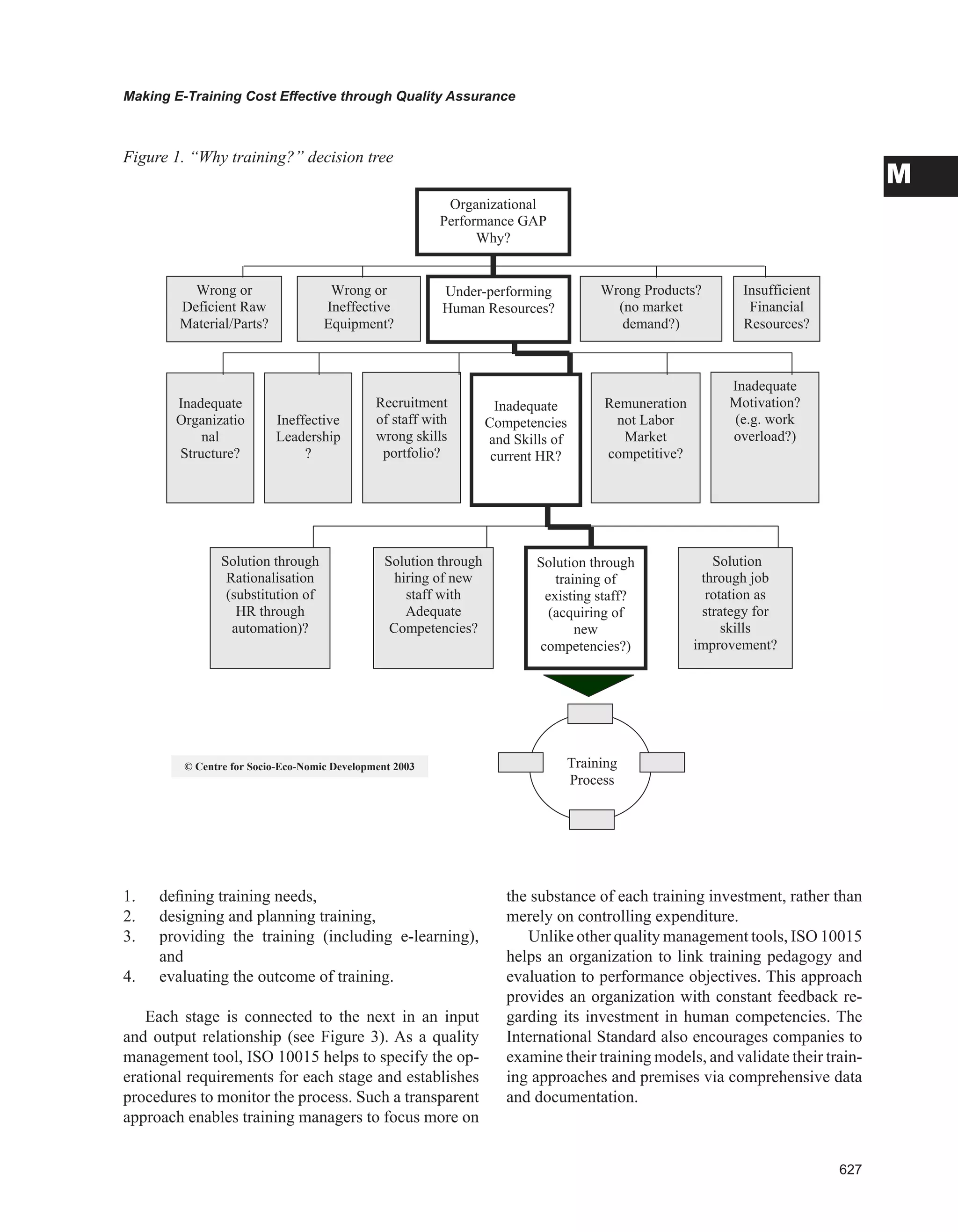

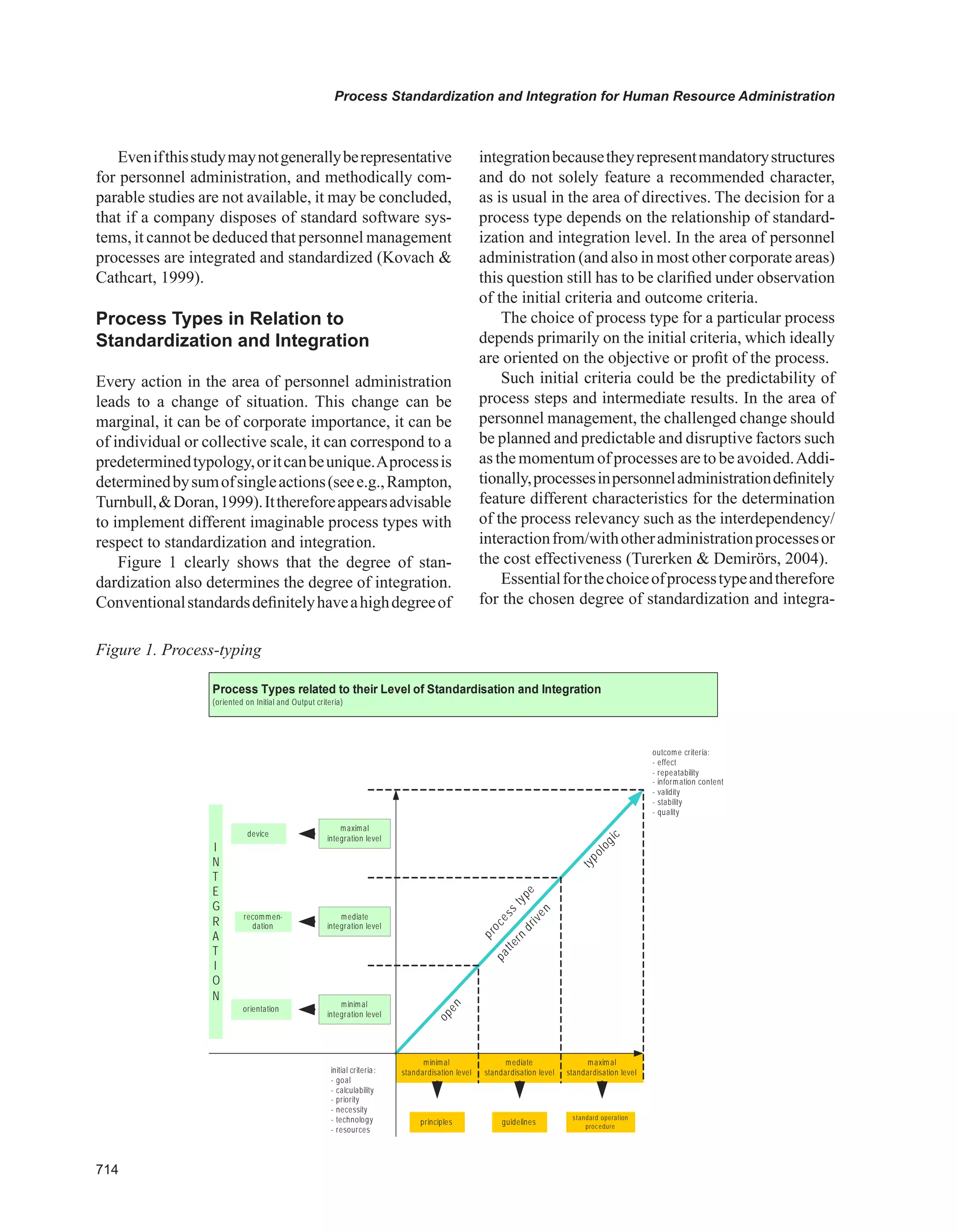

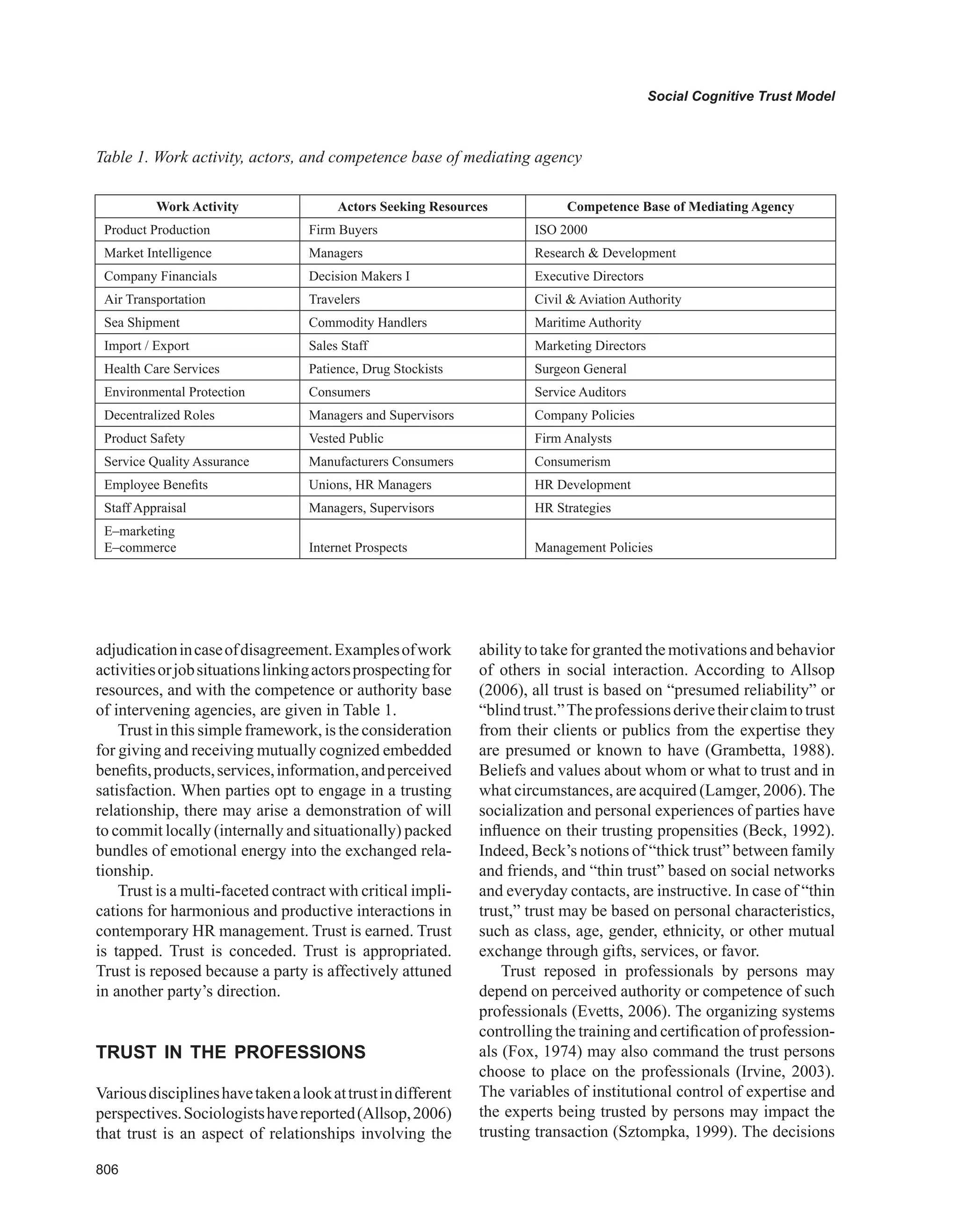

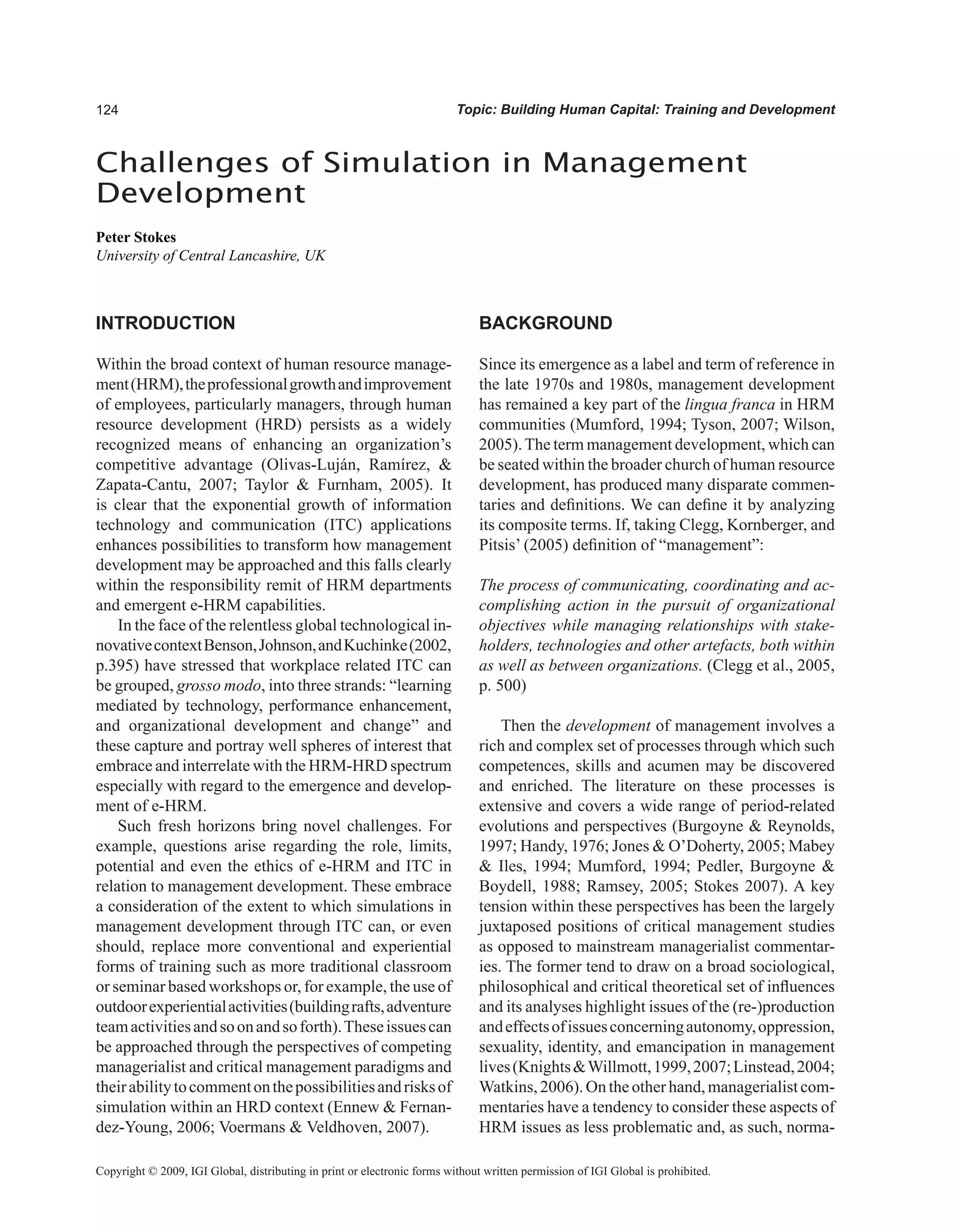

Figure3.Summaryrepresentationofusesasanarticula-

tion between an organization, a portfolio of collabora-

tive technologies and a collaborative technology

COLLABORATIVE TOOLS

NEW TOOLORGANISATION](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-183-2048.jpg)

![Collaborative Technologies, Applications, and Uses

C

Markus, M. L., Connoly, T. (1990, October). Why

CSCW applications fail. Problems in the adoption of in-

terdependent work tools. In Proc. of the CSCW’90, LA.

Oiry, E. (2004). De la qualification a la competence:

Rupture ou continuité? [From qualification to compe-

tence: rupture or continuity?] Paris: L’harmattan.

Oiry, E. (2006, October). E-learning effectiveness:

Should we not take its effects on socialization into

account? In Proceedings of 1st European Academic

Workshop on E-HRM, Twente, The Netherlands.

Olson,T.K.,Teasley,S.(1996).Groupwareinthewild.

Lessonslearnedfromayearofvirtualcollocation.InProc.

of the CSCW’96 (pp. 362-369). Boston: ACM Press.

Orlikowski,W.(2000).Usingtechnologyandconstitut-

ingstructures:Apracticelensforstudyingtechnologyin

organizations. Organization Science, 11(4), 404-428.

Pascal, A., Thomas, C. (2007, July). Role of bound-

ary objects in the co-evolution of design and use: the

KMP experimentation. In Proceedings of 23rd EGOS

Colloquium, Vienna, Austria.

Pérocheau, G. (2007, June). Comment piloter un projet

collaboratif d’innovation? In Proceedings of the 16th

Conference AIMS, Montréal, Canada.

Rabardel, P. (2005). Instrument, activité et développe-

ment du pouvoir d’agir. In R.Teulier P. Lorino (Eds.),

Entreconnaissanceetorganization:l’activitécollective

(pp. 251-265). La Découverte: Paris.

Schmidt, K., Simone, C. (1996). Coordination

mechanism.TowardsaconceptualfoundationofCSCW

systemsdesign.ComputerSupportedCooperativeWork,

5(2/3), 155-200.

Woolgar, S. (1991). Configuring the user: The case of

usability trials. In J. Law (Ed.), Asociology of monsters.

Essays on power, technology and domination (pp. 58-

99). London: Routledge.

KEY TERMS

Collaborative Technologies: Computer-based sys-

temsthatsupportgroupsofpeopleengagedinacommon

task (or goal) and that provide an interface to a shared

environment (Clarence, Ellis, Gibbs, Rein, 1991).

ComputerSupportedCooperativeWork(CSCW):

Generic term, which combines the understanding of the

way people work in groups with the enabling technolo-

gies of computer networking, and associated hardware,

software, services and techniques” (Wilson, 1991).

Social Uses: Modes of use demonstrating with suf-

ficient recurrence and in the form of uses which are

sufficiently integrated in daily life to be able to insert

and impose themselves in the range of pre-existing cul-

tural practices, to be able to reproduce themselves, and

eventually resist as specific practices against competing

orconnectedpractices(Lacroix,1994)toanticipatehow

real users interact with the technology they propose.

Structurational Perspective on Technology:

Wanda Orlikowski (2000) proposes to mobilize the

structurational theory (Giddens, 1984) to explain why

users develop different uses of a common technology.

She distinguishes two aspects in a technology:

• technologyasatechnicalartifact,“whichhasbeen

constructedwithparticularmaterialsandinscribed

withdevelopers’assumptionsandknowledgeabout

the world at a point in time” (Thomas Pascal,

2007), and

• technology as a technology-in-practice, “which

refers to the specific structure routinely enacted

by individuals as they use the artifact in recurrent

waysintheireverydaysituatedactivities”(Thomas

Pascal, 2007).

Those recurrent interactions and those “situated ac-

tivities” are different by themselves but, more than that,

they are “situated in the structural properties of social

systems. Thus, in interacting with a technology, users

mobilize many structurals, those borne by the technol-

ogy itself, and those deriving from different contexts

(group, community, organization, company, etc.) in

which their uses are developed” (Thomas Pascal,

2007). In this perspective, those different interactions

and those different structurals explain the diversity of

uses of a common technology.

User-Centered Design (UCD): User-centered de-

sign is a project approach that puts the needs, wants,

and limitations of intended users of a technology at the

center of each stage of its design and development. It

does this by talking directly to the user at key points

in the project to make sure the technology will deliver

upon their requirements. In this project approach, such

testingsarenecessarybecauseitisconsideredasimpos-

sible for the designers](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-184-2048.jpg)

![Communities of Practice

C

of systems and necessary structures for organizational

learning will play a decisive role in substantiating com-

petitive advantages.

However,otherauthorsdefendthatsuchapointisnot

necessarily true, because sometimes this process could

beengagedthroughoutmergersandacquisitions,which

embrace tremendous cultural problems.

REFERENCES

Ackerman, M., Pipek,V. Wulf,V. (2003) Sharing Ex-

pertise: Beyond Knowledge Management. Cambridge:

MIT Press.

Brown, J. S. and Duguid, P. (1996). Organisational

learningandcommunitiesofpractice:towardanunified

view of working, learning, and innovation. In Cohen

and Sproull (Eds.). Organisational learning, Thousand

Oaks: Sage.

Cardoso,G.(1998).Paraumasociologiadociberespaço.

Oeiras: Celta Editora.

Davenport,T.andPrusak,L.(1998).Workingknowledge:

how organisations manage what they know. Boston:

Harvard Business School Press.

Denison,D.,Hart,S.andKahn,J.(1996).FromChimneys

to Cross-Functional Teams: Developing and Validating

a Diagnostic Model,Academy of Management Journal,

39, 4, 1005-1023.

Fontaine, M. and Millen, D. (2004). Understanding

the benefits and impact of communities of practices.

In Hildreth and Kimble (Eds.). Knowledge networks:

innovation through communities of practices, Hershey,

London: Idea Group Inc, 1-13.

Gherardi, S. et al. (1995). Gender, symbolism and or-

ganizational cultures. London: Sage.

Grove,A.(1998).Onlytheparanoidsurvive.NewYork:

Gardners Books.

Hildreth, P. and Kimble, C. (2004). Knowledge Net-

works: Innovation through Communities of Practice.

Hershey, London: Idea Group Publishing.

Hislop, D. (2004). The paradox of communities of

practice: knowledge sharing between communities.

In Hildreth and Kimble (Eds.). Knowledge networks:

innovation through communities of practices, Hershey,

London: Idea Group Inc, 36-45.

Kaufman, P. (1995). New trading systems and methods.

4th ed. London: Wiley.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: le-

gitimateperipheralparticipation.Cambridge:University

of Cambridge Press.

Martin,V., Hatzakis,T. and Lycett, M. (2004). Cultivat-

ing a community of practice between business and IT.

In Hildreth and Kimble (Eds.). Knowledge networks:

innovation through communities of practices, Hershey,

London: Idea Group Inc, 24-35.

Orr, J. (1996). Talking about machines: an ethnography

of a modern job. [S.l.]: Cornell University.

Paccagnella, L. (2001). Online Community Action:

Perils and Possibilities. In Werry and Mowbray (Eds.).

Online Communities: Commerce, Community Action,

andtheVirtualUniversity,UpperSaddleRiver:Prentice

Hall, 365-404.

Pina e Cunha, M., Fonseca, J. and Gonçalves, F. (2001).

Empresas, caos e complexidade- gerindo à beira de um

ataque de nervos. Lisboa: Editora RH.

Qureshi, S. (2000). Organisational change through col-

laborative learning in a network, Group Decision and

Negotiation, 9, 129-147.

Szulanski, G. (2003). Sticky Knowledge: Barriers to

Knowing in the Firm Sage. Thousand Oaks: CA.

Wenger, E. and Snyder, W. (2000). Communities of

practice: the organizational frontier, Harvard Business

Review, January-February, 139-145.

Wenger, E. (1999) Communities of practice: learning,

meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press.

KEY TERMS

Community: Individuals’ group that is organized

around a physical, social, cultural, and technological

atmosphere.

Communities of Practices: Community of people

belongingtothesameprofessionalgroup,whichcreates

a culture, language, and rituals.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-190-2048.jpg)

![Topic: Managing Individuals and Groups in the Organization

Conception, Categorization, and Impact of

HR-Relevant Virtual Communities

Anke Diederichsen

Saarland University, Germany

Copyright © 2009, IGI Global, distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

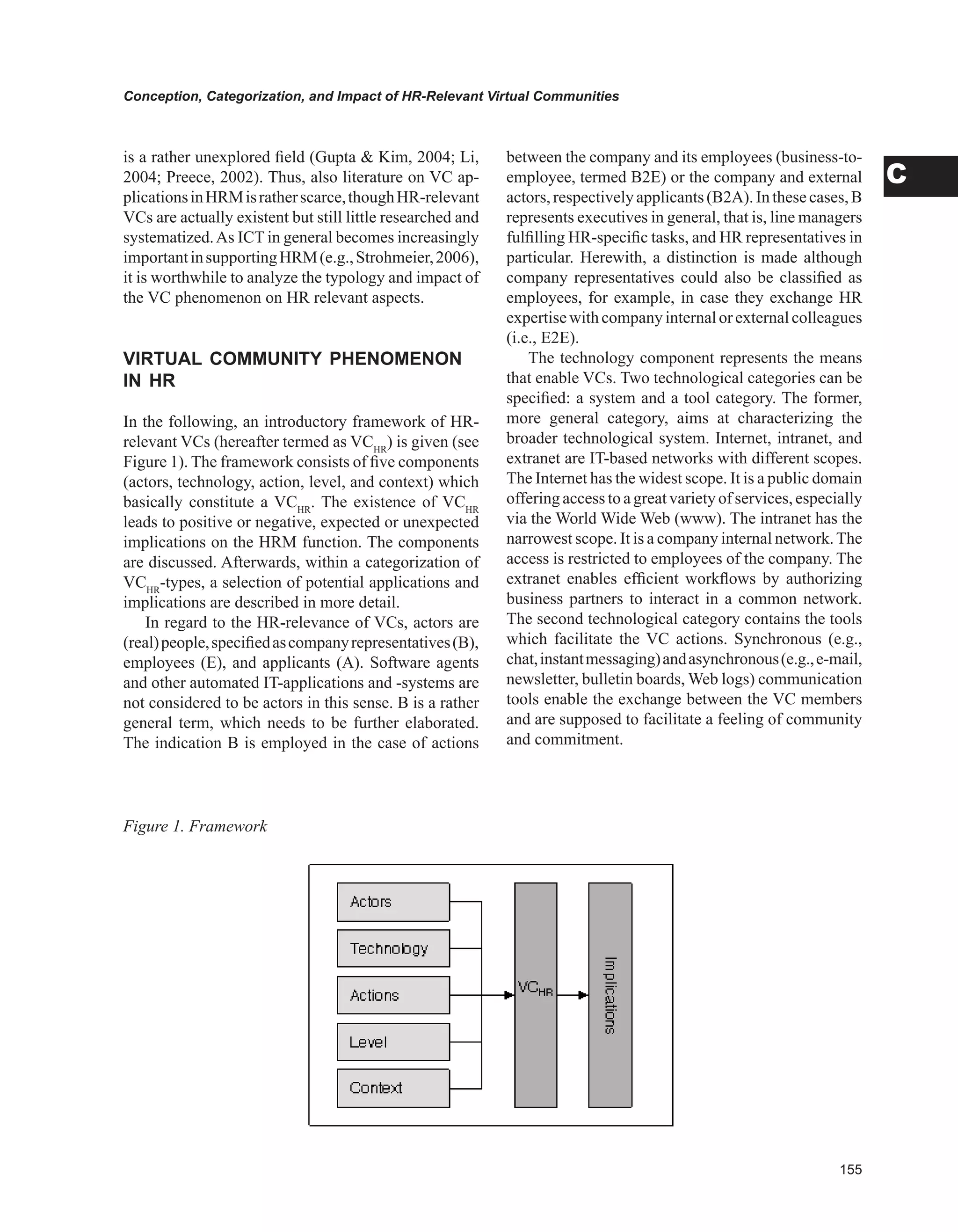

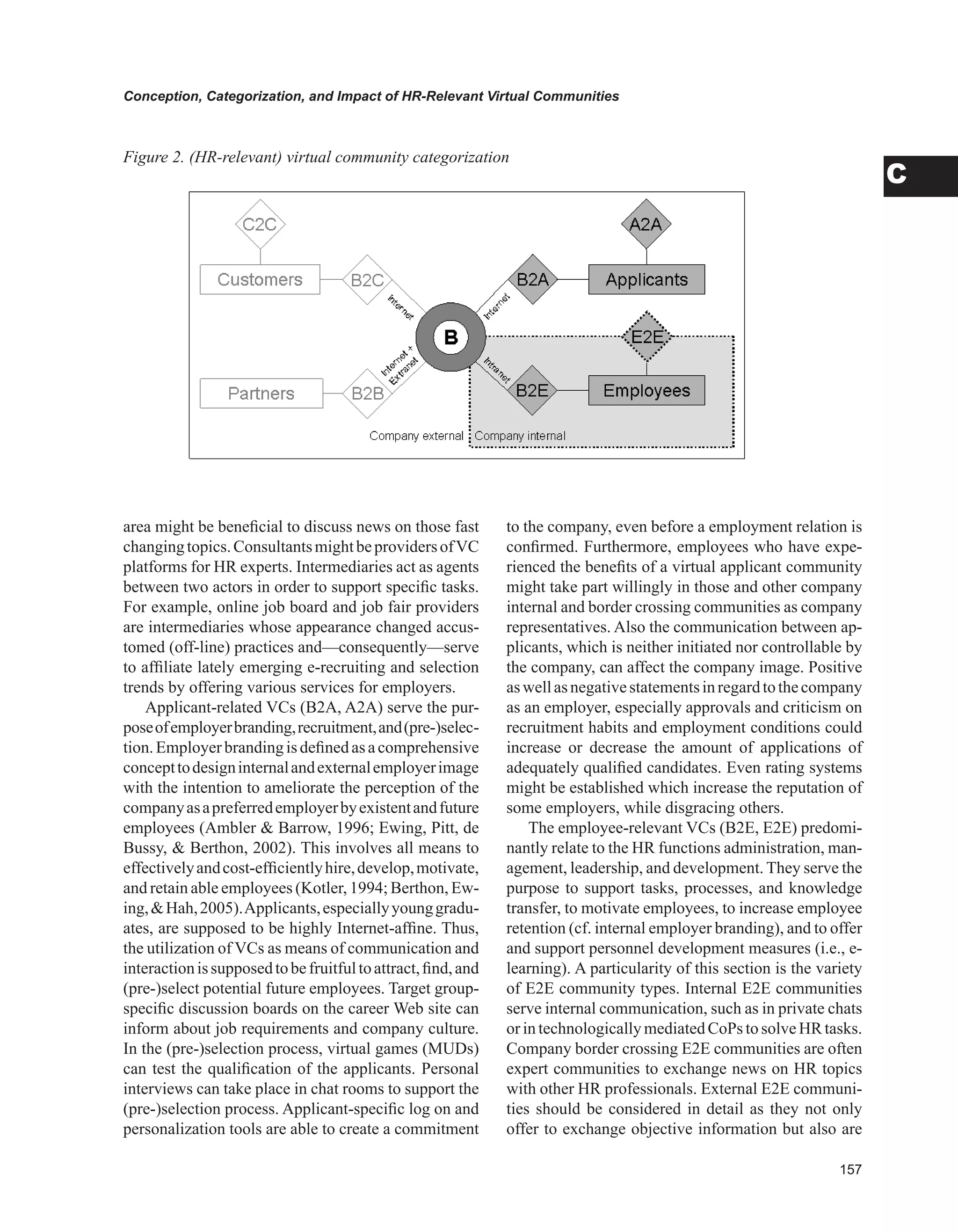

INTRODUCTION

Virtual community (VC), in its most general sense, is

an increasingly popular and apparently omnipresent

tool to communicate and interact on the Web. People

from diverse backgrounds meet in VCs for likewise

diverse purposes: social gatherings, information shar-

ing, entertainment, social, and professional support.

The phenomenon of virtual—or online—commu-

nities dates back to the late 1960s, when ARPANET,

a network for U.S.-military research purposes was

established (Licklider Taylor, 1968). The initially

provided e-mail service was later supplemented by a

chat functionality. In 1979, virtual social interaction

was enabled by USENET use-groups. Here, asynchro-

nous communication is enabled by e-mail and bulletin

boards.Inthesameyear,multiuserdungeons(MUDs),

a new form of text-based virtual reality games were

created. In 1985, The WELL was started. This mainly

bulletin board-based VC received public attention at

least by the publication of the community experiences

of one of its most active members, Howard Rheingold.

His book also marks the starting point of the virtual

community literature (Rheingold, 1993). In the late

1990s, the focus on VCs as Web-based enablers of

social interaction (e.g., Wellman, Salaff, Dimitrova,

Garton, Gulia, Haythornthwaite, 1996) shifted to

the perception of its potential economic value (e.g.,

Hagel Armstrong, 1997).

The aim of this article is to depict applications of

VCs in human resources (HR)-relevant processes.

Applications range from company internal employee

communitiestocompanyexternalapplicantcommuni-

ties. HR-relevant VCs reflect the increasing utilization

of modern information and communication technol-

ogy (ICT) in human resource management (HRM).

The application of VCs in HRM might be beneficial

but also may cause negative effects if current trends

are not observed or if the technology is not incorpo-

rated strategically. In the following, a definition, a

framework, and a categorization of HR-relevant VCs

is given. Examples outline potential applications and

implications for HRM.

BACKGROUND

Sincethe1990s,VCshavebecomeanomnipresentterm

andtool.InnumerableVCsontheWebandamultiplicity

of heterogeneous research confirm the importance and

impact of the VC development in private and business

life in the Internet era.

There are diverse definitions of the VC term, and

no consensus has been attained yet. Though, the tenor

of all definitions might be regarded as equal compris-

ing the main criteria: group of people, shared interest,

and technologically mediated. Rather generally, “[…]

a virtual community is defined as an aggregation of

individuals or business partners who interact around a

sharedinterest,wheretheinteractionisatleastpartially

supported and/or mediated by technology and guided

by some protocols or norms” (Porter, 2004). Then

again, a specification in regard to the field of HRM

is needed, so that VCs with an impact on HRM are in

the broadest sense defined as groups of people, who

join primarily in Web-based places to deliberately,

moderated or independent, communicate and interact

on HR-relevant aspects.

Research literature on VCs is abundant, yet rather

diverse and fragmented due to different perspectives,

for example, sociological and cultural, economical,

technological, experiential, scholarly and method-

ological, evolutionary and design-related, and finally

the application perspective. An inclusive research

framework, which integrates different perspectives,

is worthwhile, yet still missing. The predominant part

of VC research is presented in exploratory case stud-

ies and conceptual works. Recent scholarly studies

prevalentlyfocusondevelopmentanddesignissues,as

well as on VC dynamics. Research on VC application](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-197-2048.jpg)

![Conception, Categorization, and Impact of HR-Relevant Virtual Communities

C

Kim, A. J. (2000). Community building on the Web.

Amsterdam: Addison-Wesley Longman.

Kotler, P. (1994). Marketing management: Analysis,

planning, implementation and control (8th

ed.). Engle-

wood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Lechner,U.,Hummel,J.(2002).Businessmodelsand

system architectures of VCs: From a sociological phe-

nomenon to peer-to-peer architectures. International

Journal of Electronic Commerce, 6(3), 41-53.

Li, H. (2004, August). Virtual community studies: A

literature review, synthesis and research agenda. In

Proceedings of the Tenth Americas Conference on

Information Systems, New York, (pp. 2708-2715).

Licklider, J. C. R., Taylor, W. (1968, April). The

computerasacommunicationdevice.ScienceandTech-

nology, 21-41. Reprinted in Digital Research Center

(1990): In memoriam: J.C.R. Licklider (1915-1990).

Lopez, R. F. (2000). Corporate strategies for address-

ing internet “complaint” sites. Retrieved July 6, 2005,

fromhttp://www.thelenreid.com/index.cfm?section=a

rticlesfunction=ViewArticlearticleID=252

Porter, C. E. (2004).Atypology of VCs:Amulti-disci-

plinaryfoundationforfutureresearch.JournalofCom-

puter-Mediated Communication, 10(1), Article 3.

Preece, J. (2000). Online communities—designing

usability, supporting sociability. Chichester: John

Wiley.

Rheingold, H. (1993). The virtual community. Home-

steading on the electronic frontier. Cambridge and

London: MIT Press.

Strohmeier, S. (2006). Research in e-HRM: Review

and implications. Paper submitted to review.

Tapscott, D., Ticoll, D., Lowy, A. (2000). Digital

capital:Harnessingthepowerofbusinesswebs.Boston:

Harvard Business School Press.

Taras, D., Gesser, A. (2003). How new lawyers

use e-voice to drive firm compensation: The “greedy

associates” phenomenon. Journal of Labor Research,

14(1), 9-29.

Wellman, B., Salaff, J., Dimitrova, D., Garton, L.,

Gulia, M., Haythornthwaite, C. (1996). Computer

networks as social networks: Collaborative work,

telework, and virtual community. Annual Review of

Sociology, 22, 213-238.

Wenger, E. C., Snyder, W. M. (2000, January/Feb-

ruary). Communities of practice: The organizational

frontier. Harvard Business Review, 139-145.

KEY TERMS

Bulletin Board (System): Also discussion board,

message board, or discussion group. This type of com-

munication tool offers asynchronous communication.

The participants can post comments which relate to

each other and thus form so-called threads in regard

to a certain topic.

Chat: The Internet relay chat (IRC) was developed

in the 1980s and is a (mainly) text-based, synchronous

formofcommunication.Thecommunicationtakesplace

in so-called chat rooms or channels, the participants

often use nicknames.

Communities of Practice (CoP): CoPs are “[…]

groups of people informally bound together by shared

expertise and passion for a joint enterprise […]”

(Wenger Snyder, 2000). CoPs can but do not have

to be supported by ICT.

Complaint Sites: Also gripe boards. (Former)

employees and applicants share their experiences and

vent their frustrations.

MultiUserDungeon/Domain/Dimension(MUD):

MUDs are text-based, multi-player, online computer

games. The related MOOs (MUD object oriented) are

network-accessible, interactive systems which are

often used—besides the construction of virtual reality

games—for conferencing or distance education.

Online Job Board: An exchange place which of-

fers the opportunity to present vacancies and features

to apply for a job, often accompanied by matching and

entertainmentfeatures,aswellastools(predominantly

BBS and chat) to communicate on job- and applica-

tion-relevant topics.

Online Job Fair: Regularly held job fairs on the

Internet, which offer the possibility to get job-relevant

informationon virtualcompanystands andtointensify

contacts, or even apply for a job in personal chat ses-

sions with company representatives.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-202-2048.jpg)

![Topic: Knowledge and Organizational Learning

Conceptualization and Evolution of Learning

Organizations

Baiyin Yang

Tsinghua University, China

Copyright © 2009, IGI Global, distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

INTRODUCTION

Learningorganizationhasreceivedanincreasingatten-

tion in the literature of organization and management

studies, but only few empirical studies have been con-

ductedtoexamineitsnature,antecedents,andoutcomes.

Facilitating continuous human resource development

throughout all levels of the organization is becoming

a primary challenge for many HR professionals. In the

era of knowledge economy where intellectual capital

andlearningbecomemajorsourcesofcompetitiveness,

managers of all functions have to develop and nurture

a learning culture. Consequently, human resources

information systems need to embrace the concept of

learning organization. A robust information system

should enable organizational learning, knowledge

creation, sharing, and application.

This article discusses the definitions of learning

organization,reasonsforthepopularityofthisconcept,

emergingstudiesonthistopicincludingitsrelationship

with organizational performance, practical measures

used to build learning organization, and future trends

of this topic.

CONCEPTUALIzATION OF THE

LEARNING ORGANIzATION

Anumber of approaches to defining the construct have

emerged in the literature; they are system thinking,

learningperspective,strategicperspective,andcultural

perspective.

Senge (1990) applies the system thinking approach

anddefinesthelearningorganizationasanorganization

that possesses not only an adaptive capacity but also

a generativity, that is, the ability to create alternative

futures. Senge (1990) identifies the five disciplines

that a learning organization should possess: (1) team

learning with the emphasis on the learning activities of

groupprocessesratherthanonthedevelopmentofteam

process; (2) share visions, that is, the skills of unearth-

ing shared “pictures of the future” that foster genuine

commitment and enrollment rather than compliance;

(3) mental models and the deeply held internal images

of how the world works; (4) personal mastery, which is

the discipline of continually clarifying and deepening

personalvision,offocusingenergies,ofdevelopingpa-

tience,andofseeingrealityobjectively;and(5)system

thinking, that is, the ability of seeing interrelationships

rather than linear cause-effect chains.

Pedler, Burgoyne, and Boydell (1991) take a learn-

ing perspective and define the learning organization

as “an organization that facilitates the learning of all

of its members and continuously transforms itself in

order to meet its strategic goals” (p. 1). They identi-

fied eleven areas, that of, using learning approach to

strategy, participative policy making, informating,

formative accounting and control, internal exchange,

reward flexibility, enabling structures, using boundary

workers as environmental scanners, intercompany

learning, learning climate, and self-development for

everyone.

The strategic approach to the learning organization

maintainsthatbeingalearningorganizationrequiresan

understandingofthestrategicinternaldriversnecessary

for building learning capability. Garvin (1993) defines

“[a] learning organization is an organization skilled at

creating,acquiring,andtransferringknowledge,andat

modifying its behavior to reflect new knowledge and

insights” (p. 80). Having synthesized the description

of management practices and policies related to this

construct in the literature, Goh (1998) contends that

learningorganizationshavefivecorestrategicbuilding

blocks: (1) clarity and support for mission and vision,

(2)sharedleadershipandinvolvement,(3)aculturethat

encourages experimentation, (4) the ability to transfer

knowledge across organizational boundaries, and (5)

team work and cooperation.

The cultural perspective of a learning organization

views such organizations intentionally nurture and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-215-2048.jpg)

![Topic: Managing People and Technology in New Work Environments

Developments, Controversies,

and Applications of Ergonomics

Kathleen P. King

Fordham University, USA

James J. King

University of Georgia, USA

Copyright © 2009, IGI Global, distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

INTRODUCTION

Acommonmisconceptionisthathealthconcernsinthe

workplace are only relevant in manual-labor fields or

work zones that deal with hazardous materials or tools.

In modern society, however, nearly every workplace

can benefit from studying and applying techniques

and understanding that regard the human body and its

proper alignment or use.While damage to a secretary’s

wrists from day after day of typing on a carelessly-de-

signed keyboard might be as dramatic or immediate as

a laborer’s foot being crushed by a dropped concrete

slab, such subtle injuries can be just as debilitating and

dangerous over time.

Ergonomics, as a field, addresses the appropriate

alignment and use of the body in all sorts of activities.

Thecurrentschoolofthinkingfocusesonproactivehu-

man action; however, the scant notice that ergonomics

has gleaned has only been brought on because of the

injuriesincurredwhentheproactiveapproachhasbeen

ignored. So, ironically enough, the proactive-themed

field has only gained any notice or recognition due to

reactive action.

Due to the efforts of the US Department of Labor

(or, more specifically, the Occupational Safety and

Health Association [OSHA]), the field of ergonomics

has received increased press and familiarity with the

general public in recent years. However, this identity

has still largely been focused on workplace safety in

factories or manual labor, certainly not seemingly

benign and harmless office environments. The general

public is rarely made aware of the long-term effects of

improper posture from using increasingly ubiquitous

office/computer technologies because it is not associ-

ated with such heavy labor (Bright, 2006). Nagourney

(2002)hasdoneoneofmanystudieswhichdemonstrate

that even simple corrections to posture and equipment

positioning can result in improved physical health for

computer users (Also see ECCE, 2006).

Also of note is that numerous studies have docu-

mented that leaving small repetitive injuries uncor-

rected (e.g., injuries that result from improper posture

while using computers and other office equipment)

has been found to culminate in health problems over

time (Ullrich Ullrich Burke, 2006). Because of these

findingsandthedirectbenefitsofchangingpositionand

movement, public, workplace, and formal education

needs to be improved.

Ratherthanisolatedortemporaryinjuries,individu-

alsintheseconditionsexperiencecompoundingeffects

ofimproperposturesresultingincontinuing,repetitive

(oftentimes unnoticeable) injuries. Therefore OSHA

and a broad base of professionals need to continue to

educate the general public so that they understand that

ergonomics is more than health and safety codes for

manual labor or what may be generally perceived as

physically harmful workplace situations. At the same

time, both personal and public responsibility for health

and safety needs to be exercised in communicating

information and solutions, and then implementing

them in daily practice.

Ergonomics Example

What does ergonomics mean on a day to day basis for

people in 2008 and onward? In a word: responsibility.

Bringing ergonomics into a very practical example

for most readers, Kay’s article (2001), discusses the

dilemma we face with the opposing merits and draw-

backs of using laptop computers. Kay describes the

merits of the laptop computer, presents the drawbacks

in its improper use, and then identifies the ergonomic

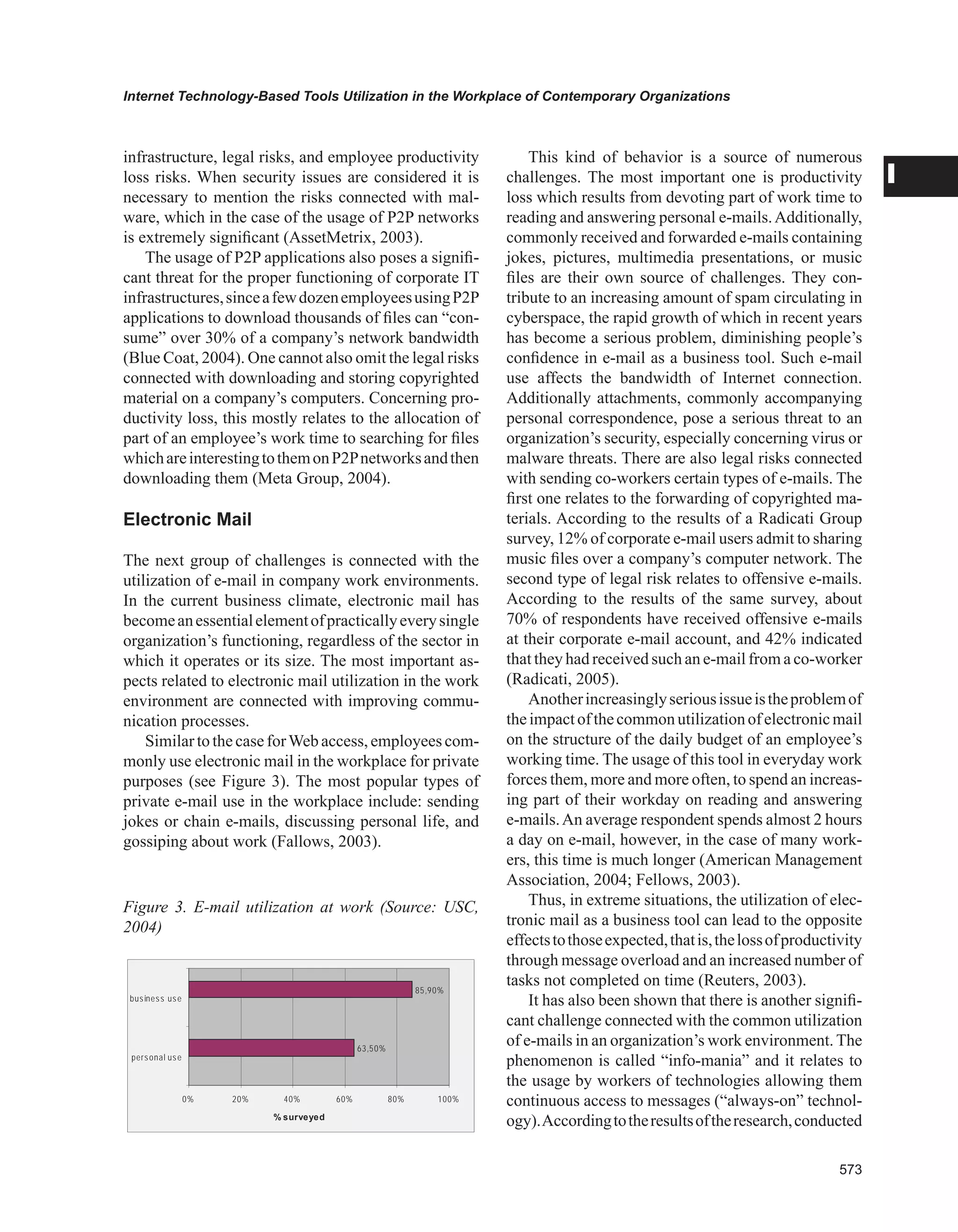

solutions:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/encyclopediaofhumanresourcesinformationsystemschallengesine-hrm-150618143559-lva1-app6892/75/Encyclopedia-of-human-resources-information-systems-challenges-in-e-hrm-279-2048.jpg)