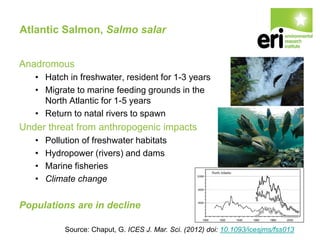

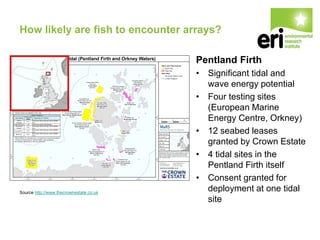

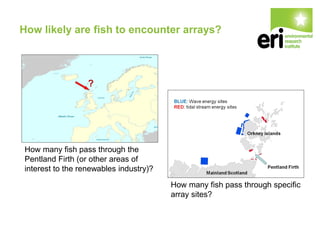

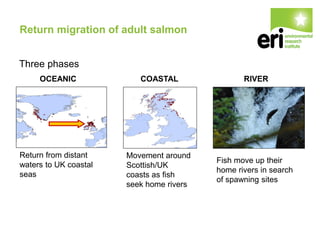

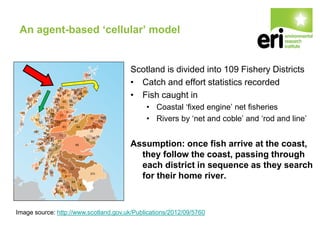

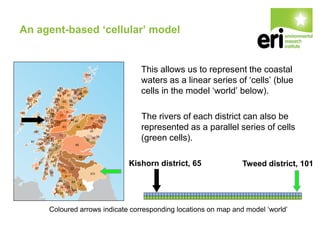

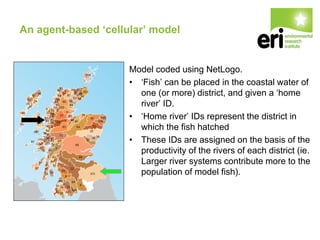

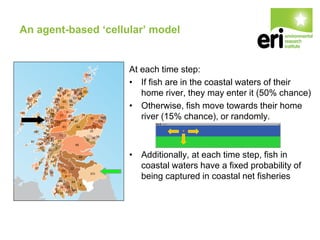

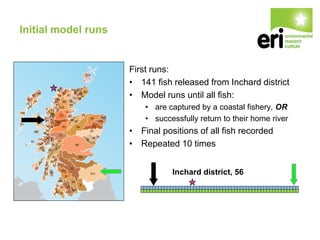

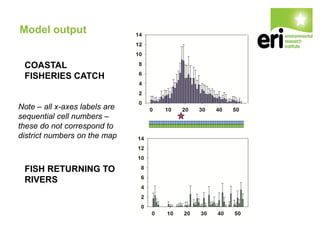

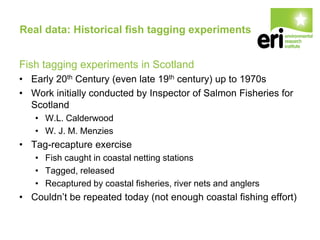

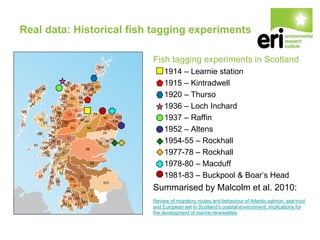

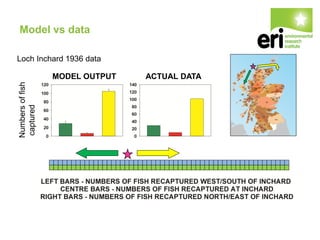

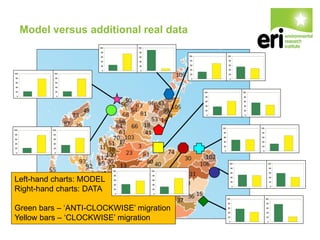

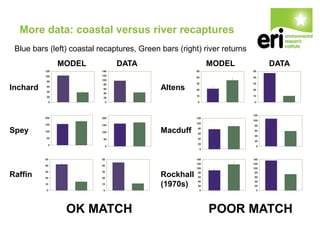

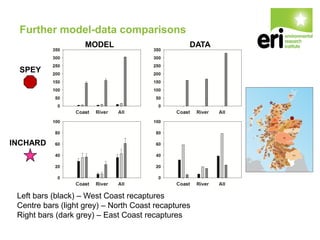

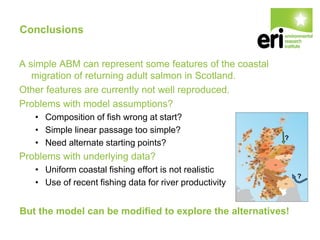

This document discusses the migration patterns of Atlantic salmon around Scottish coasts using historical tagging data and an agent-based modeling approach. It highlights the environmental threats faced by salmon populations and the potential impacts of marine renewable energy technologies on their migration routes. The research utilizes a model to simulate fish behavior and compares it with historical data to draw conclusions regarding the accuracy of the model in representing salmon migration dynamics.