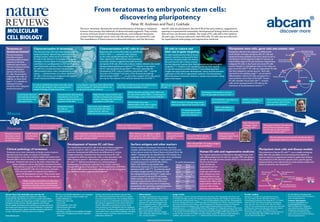

This document traces the history of research on teratomas and embryonic carcinoma (EC) cells from ancient times to present day, including several key discoveries and advances:

1) Rudolph Virchow coined the term "teratoma" in the 19th century to describe tumors containing tissues from all three germ layers.

2) In the 1950s-60s, mouse EC cells were discovered and shown to be pluripotent cancer stem cells capable of generating complex teratomas, resembling the early embryo.

3) The first human EC cell lines were established in the 1970s, though they differed from mouse EC cells. Surface antigens helped characterize both mouse and human EC cells and embryonic stem cells