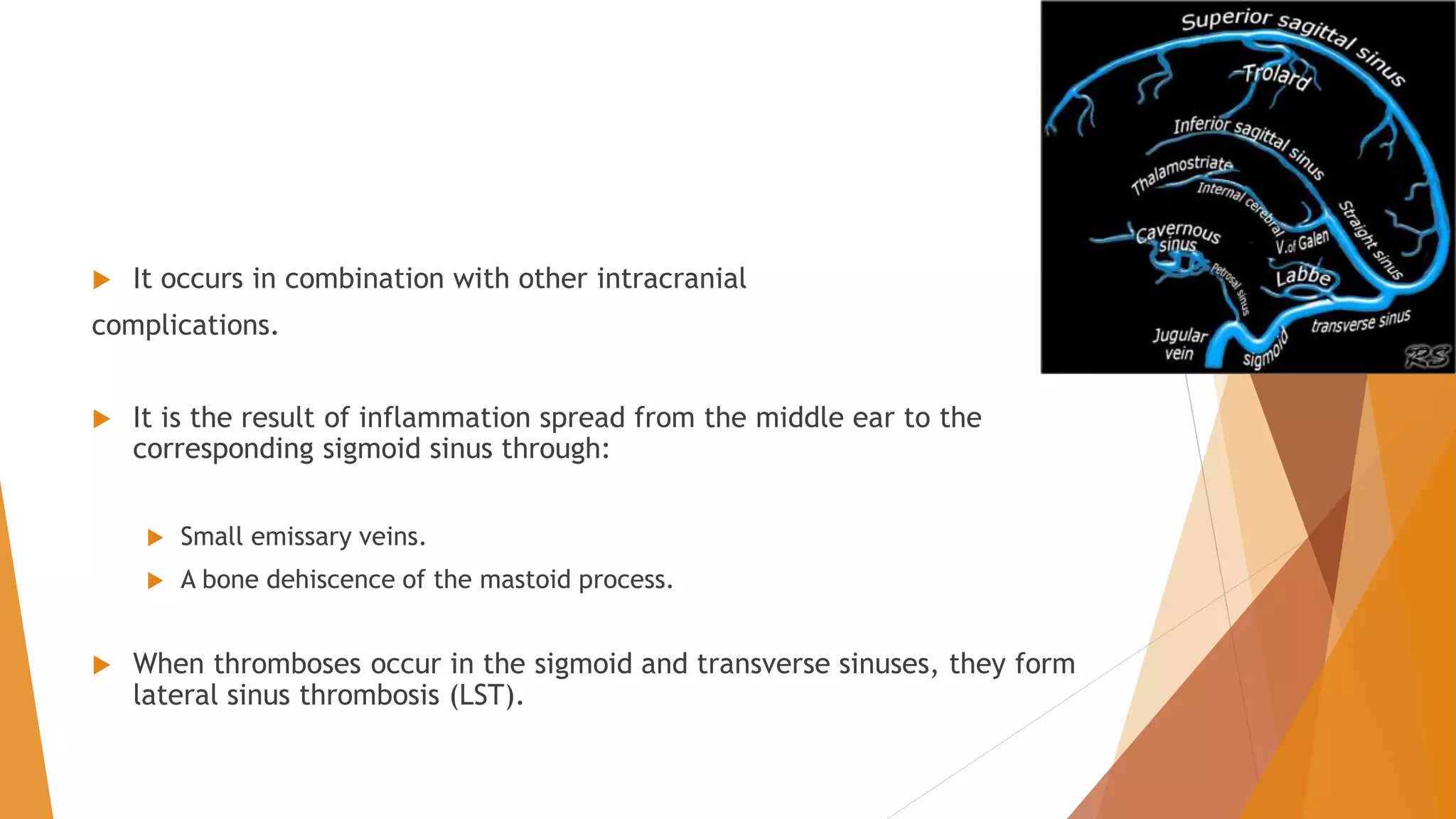

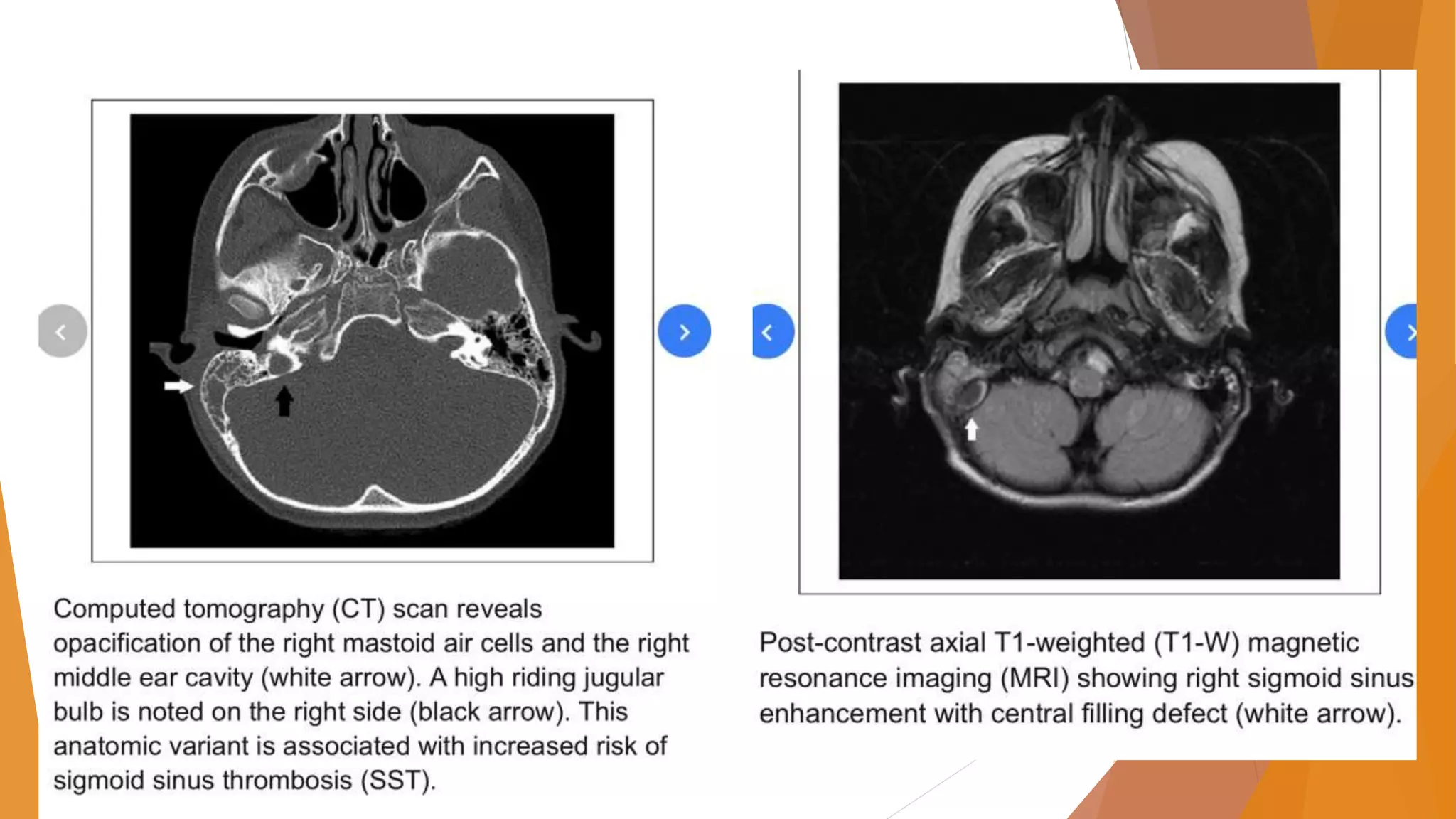

This document provides an overview of otogenic sigmoid sinus thrombosis. It discusses the epidemiology, etiology, presentation, management, and treatment of this condition. Sigmoid sinus thrombosis is usually caused by infections from acute or chronic otitis media. Clinical features vary depending on the stage but may include fever, headache, and postauricular edema. Diagnosis involves imaging studies like CT or MRI. Treatment involves long-term intravenous antibiotics as well as surgical drainage of the infection site via mastoidectomy. While controversial, some studies support the use of anticoagulation to prevent thrombus propagation, though it risks bleeding complications.