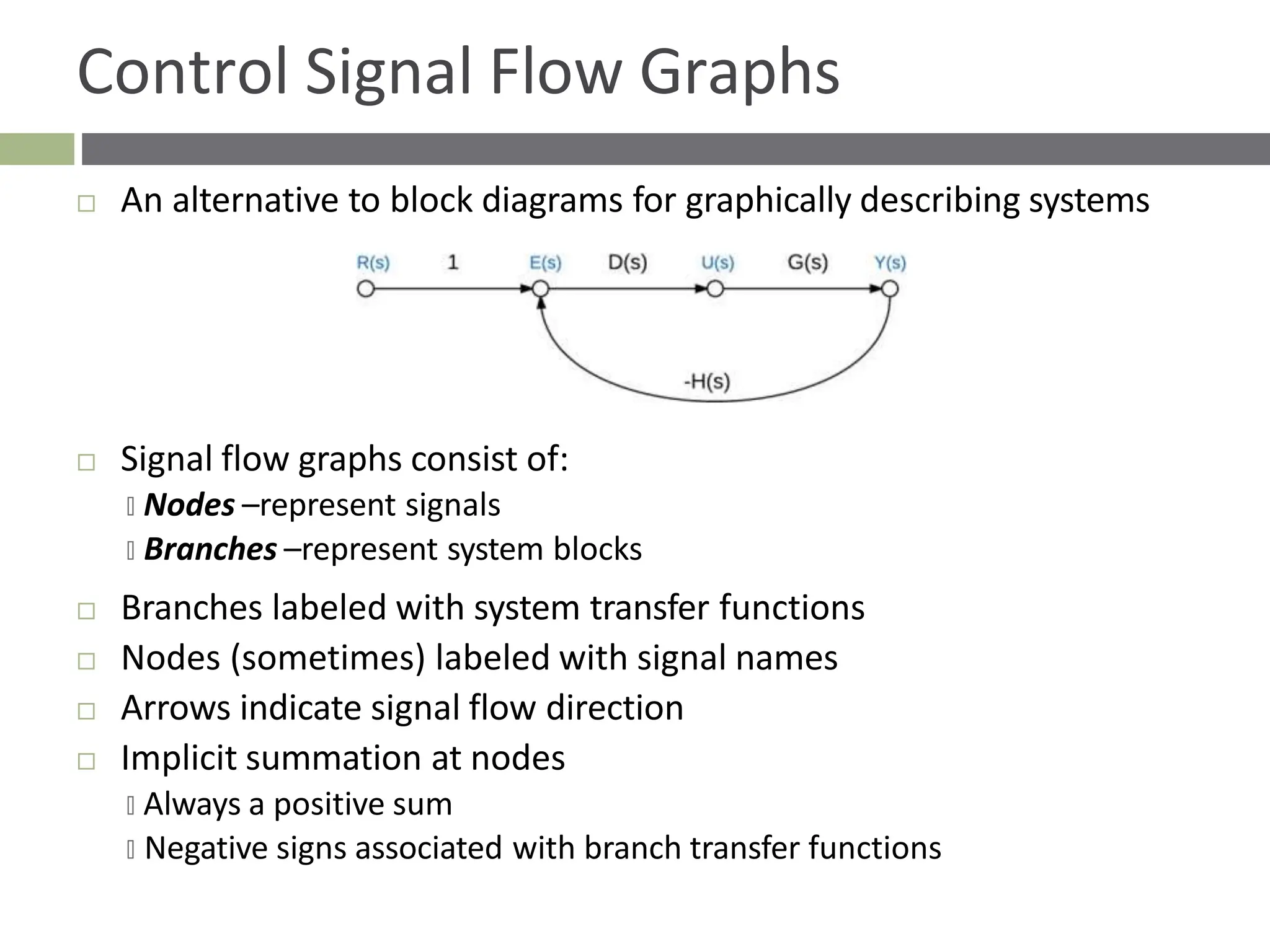

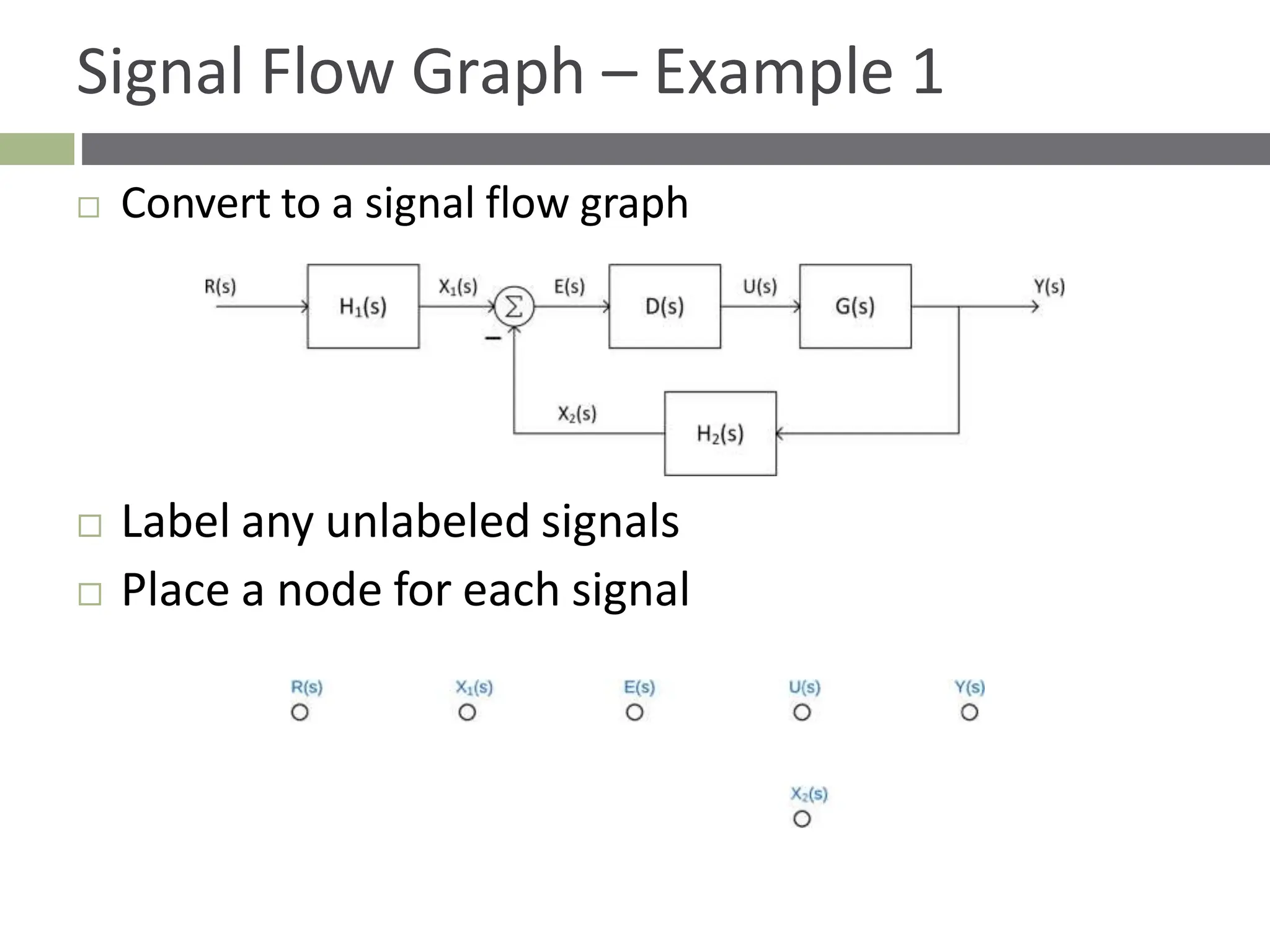

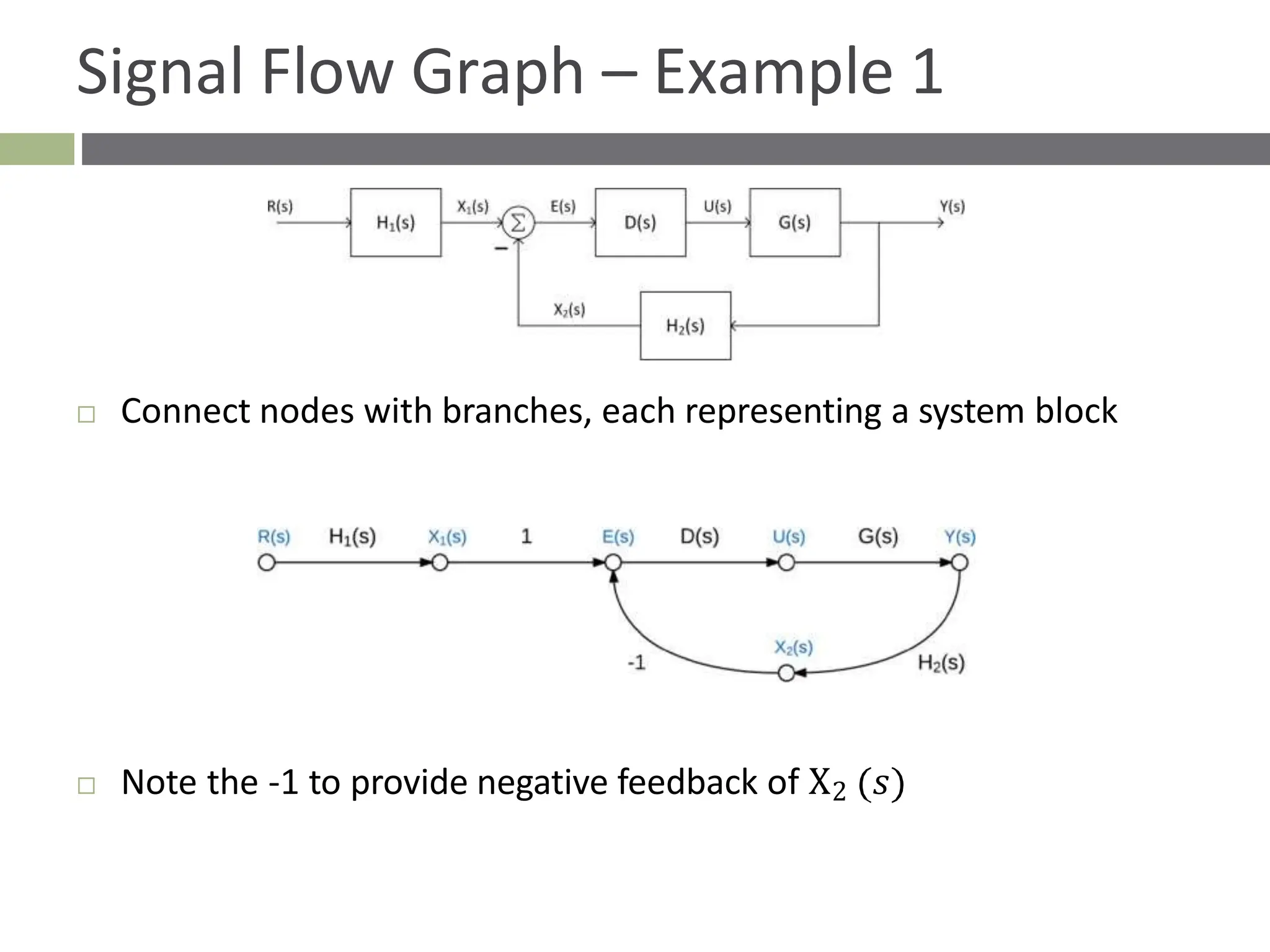

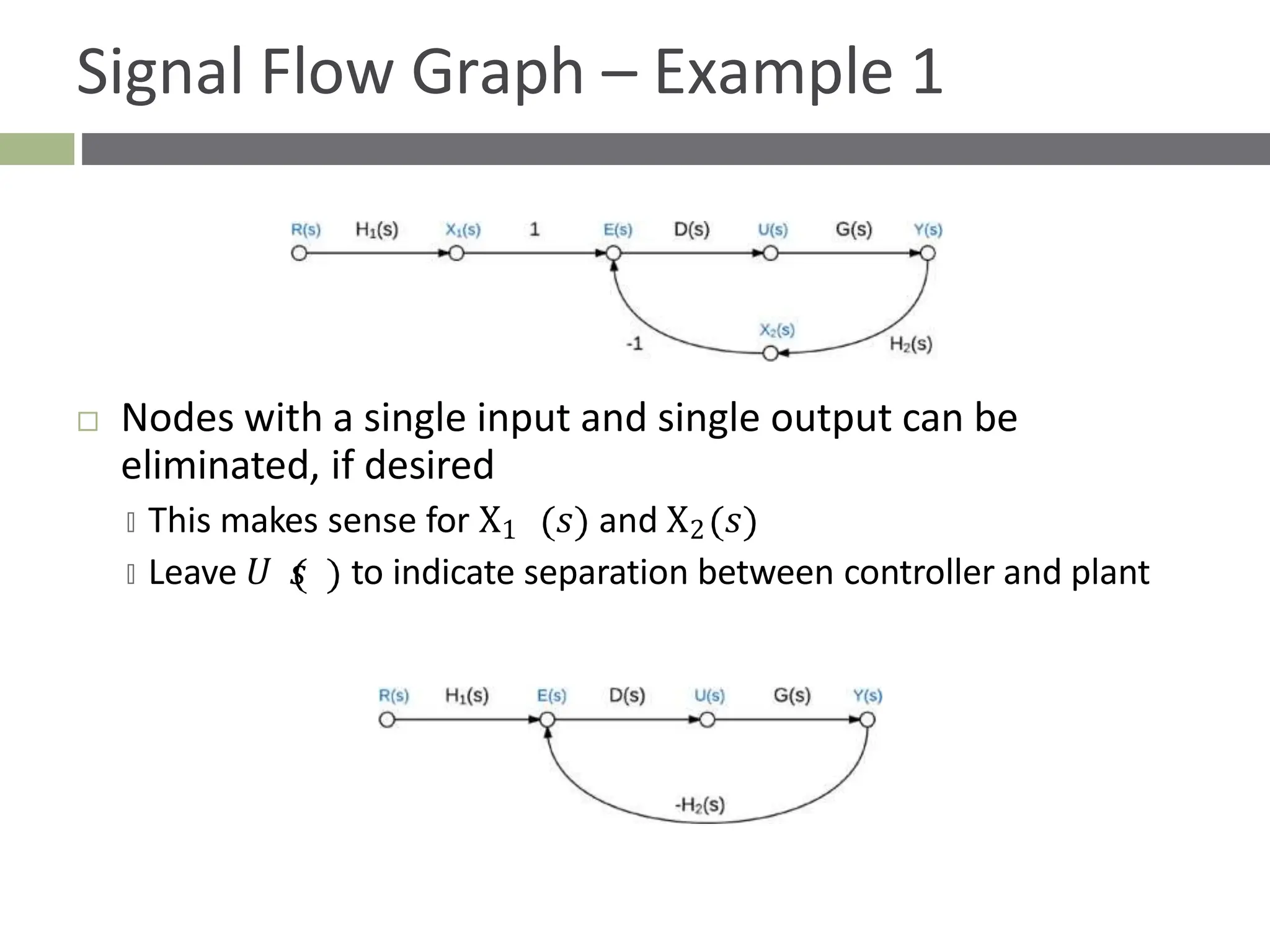

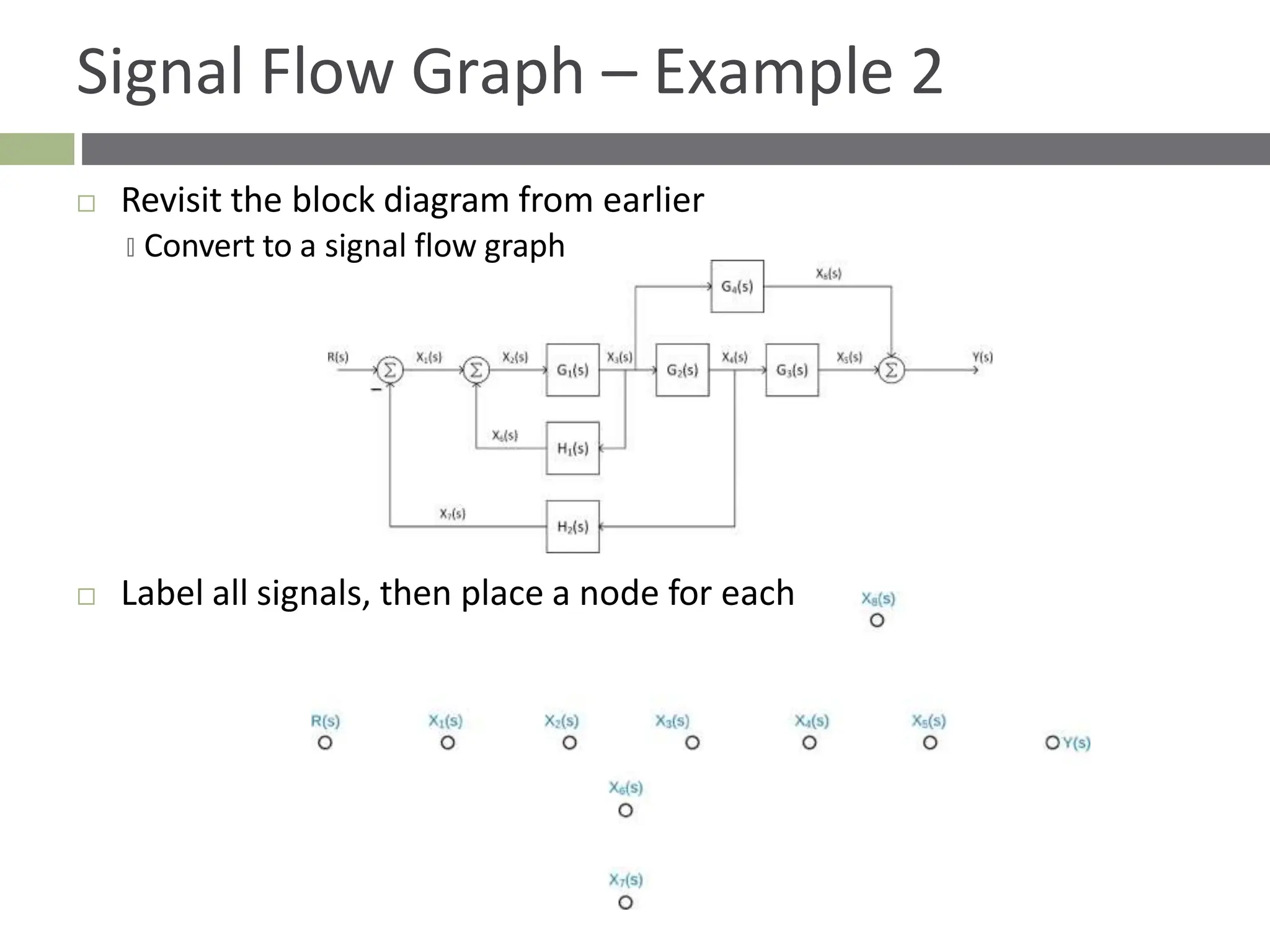

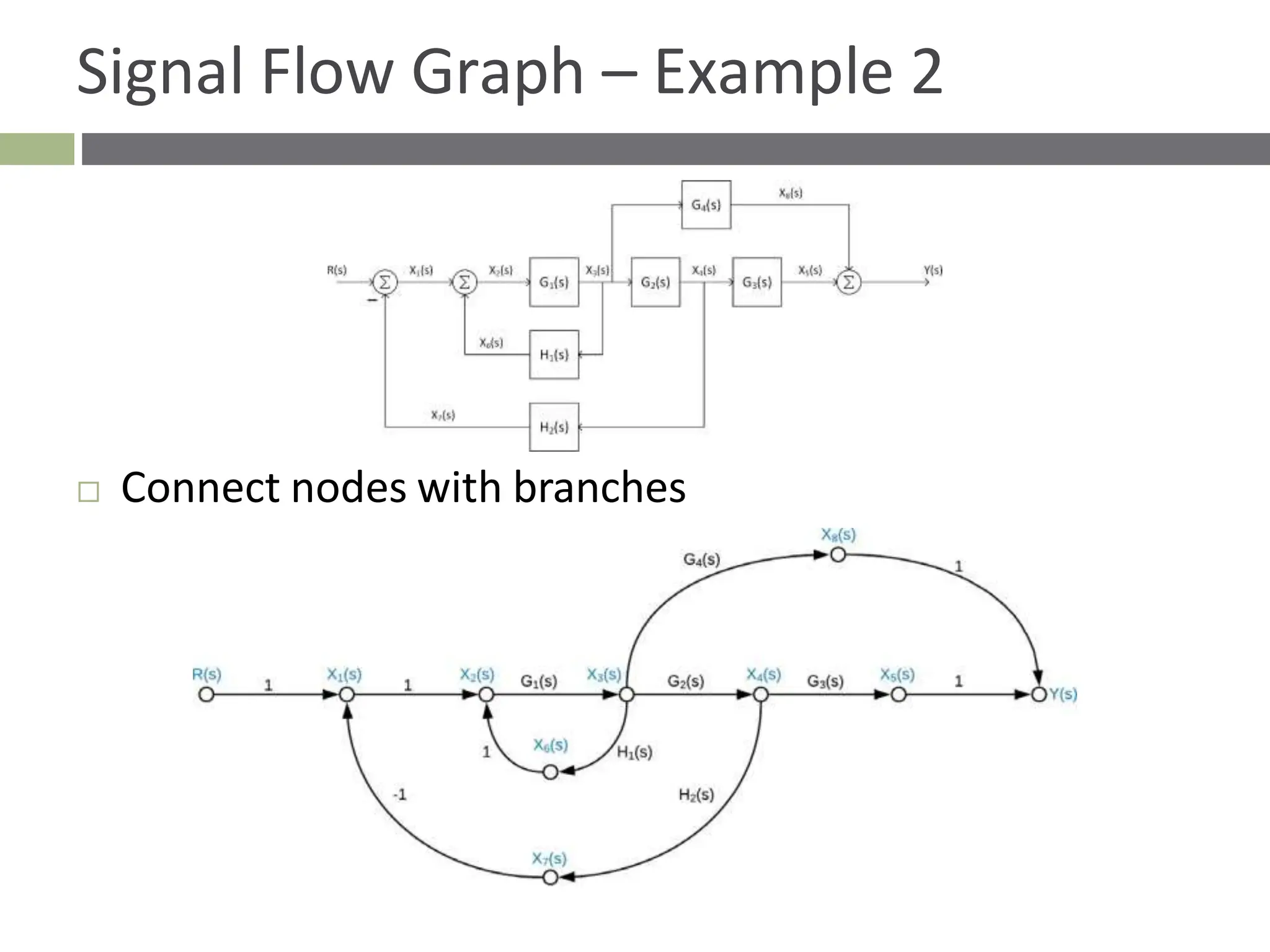

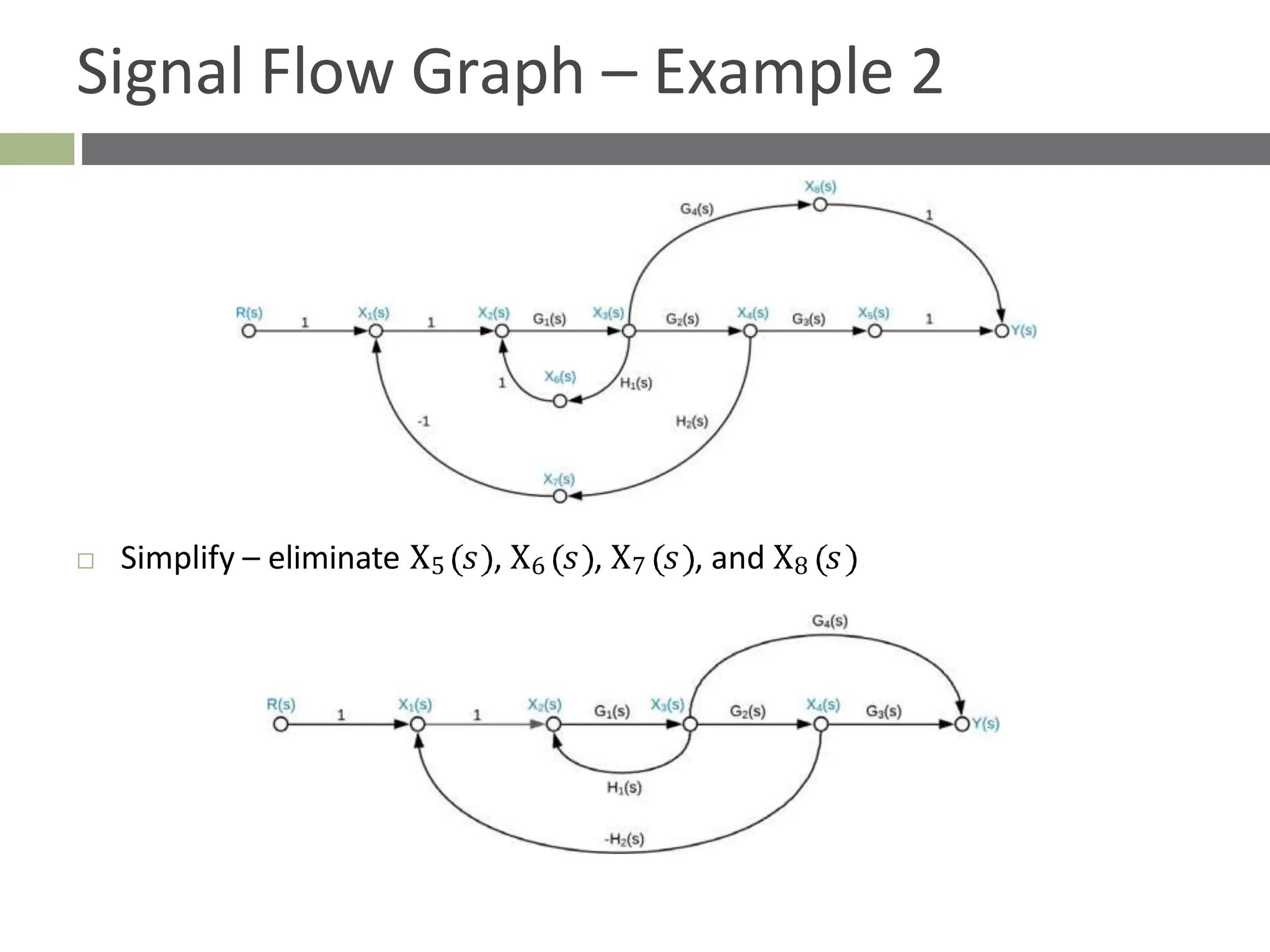

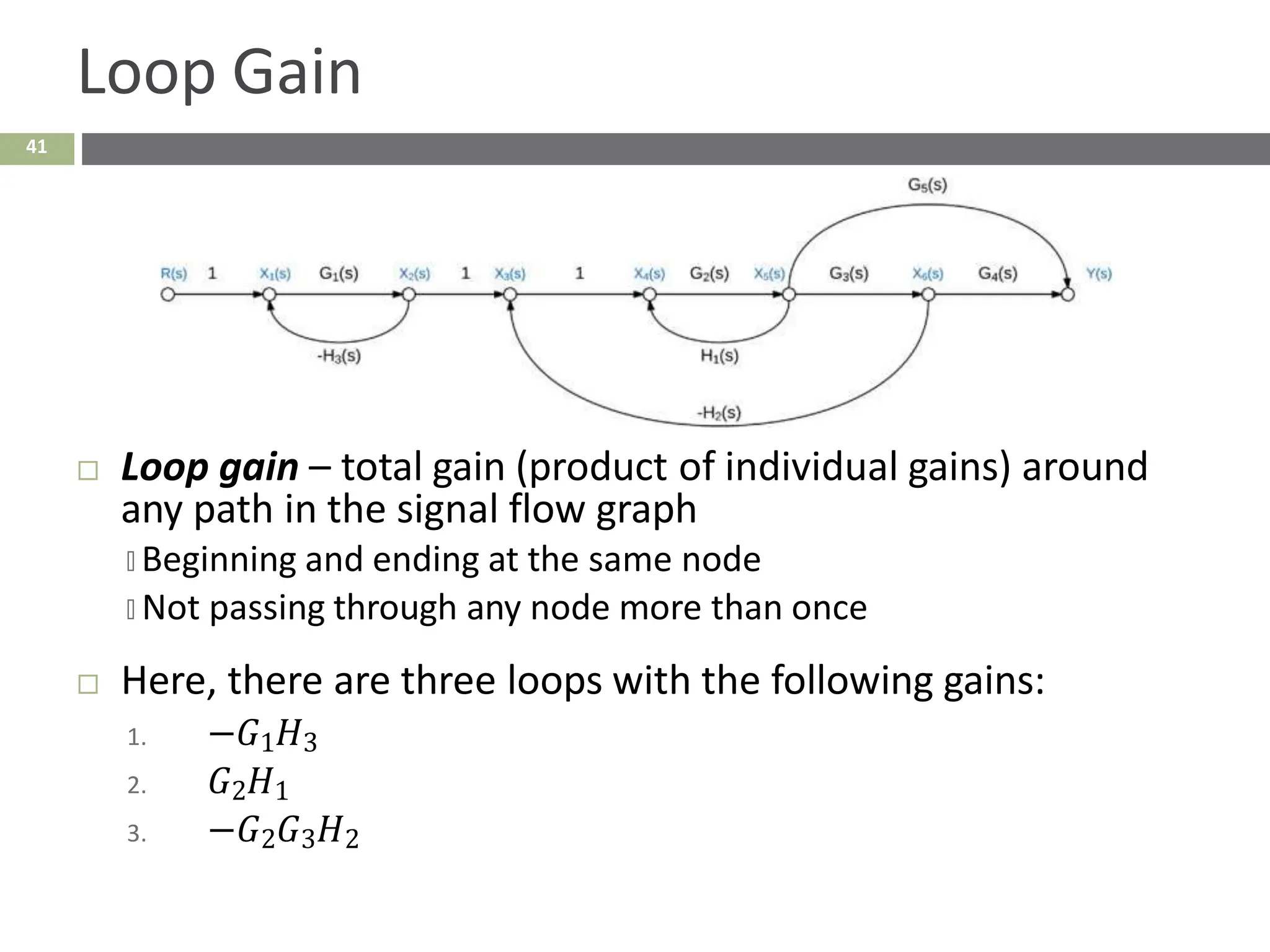

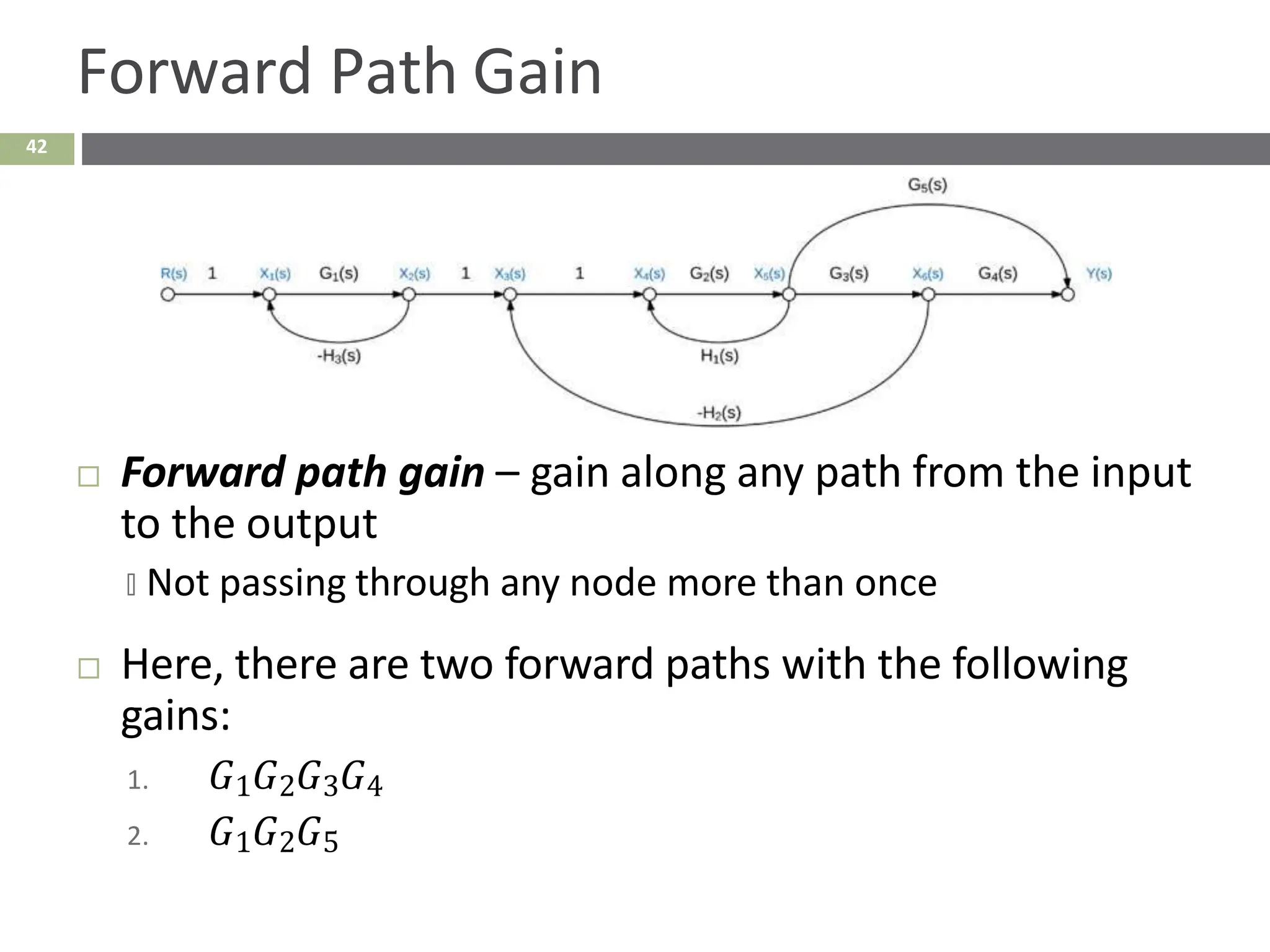

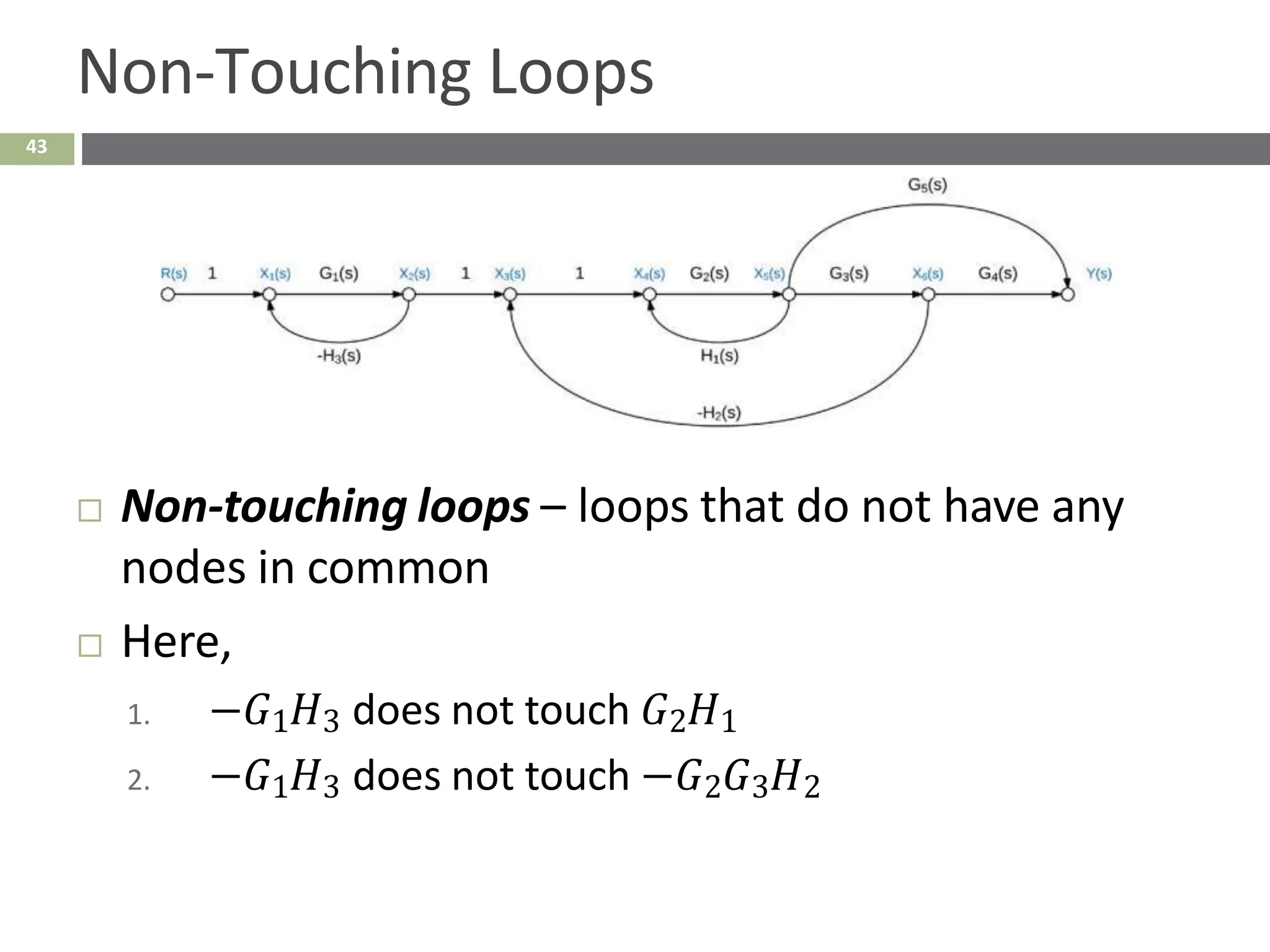

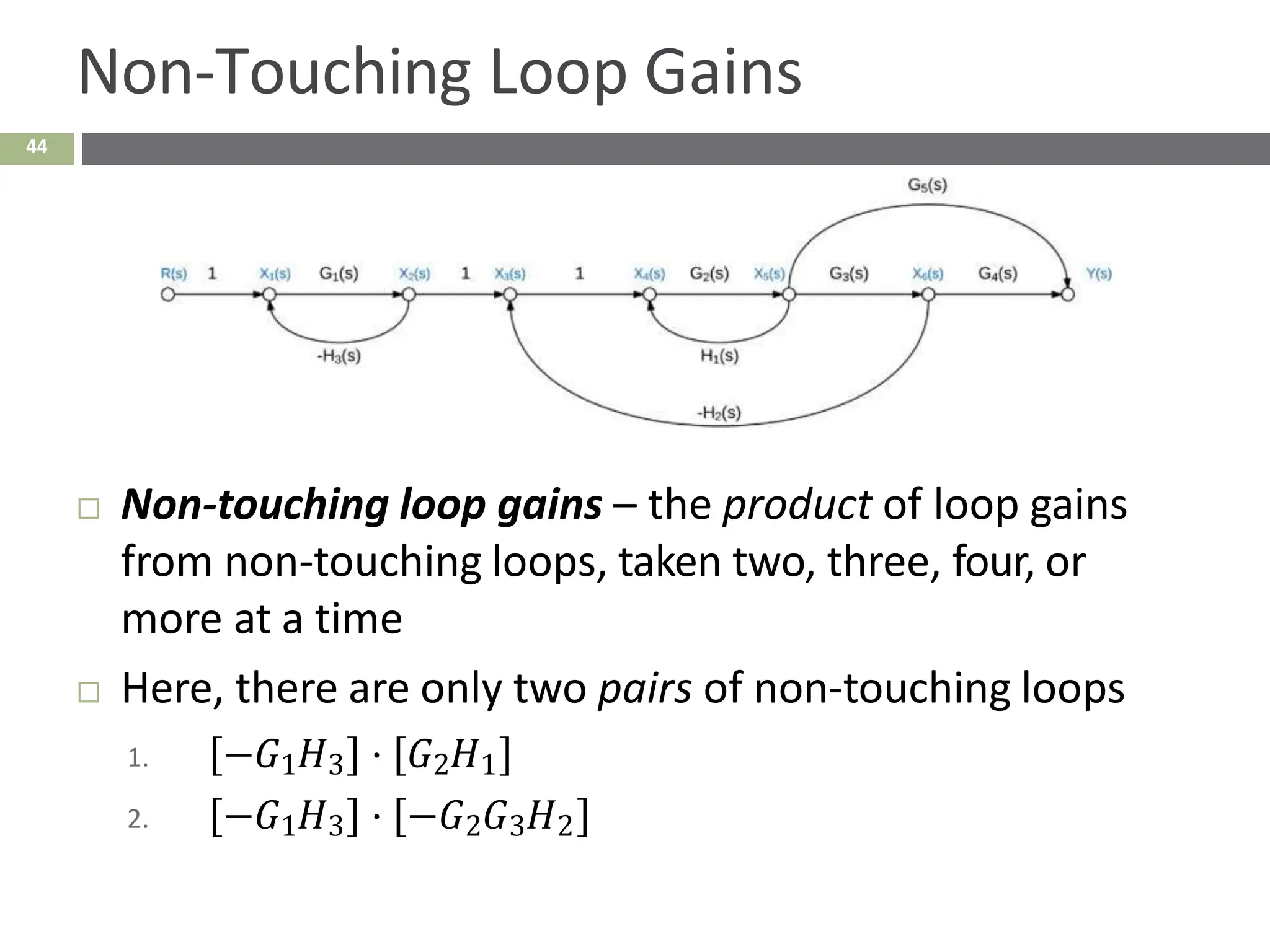

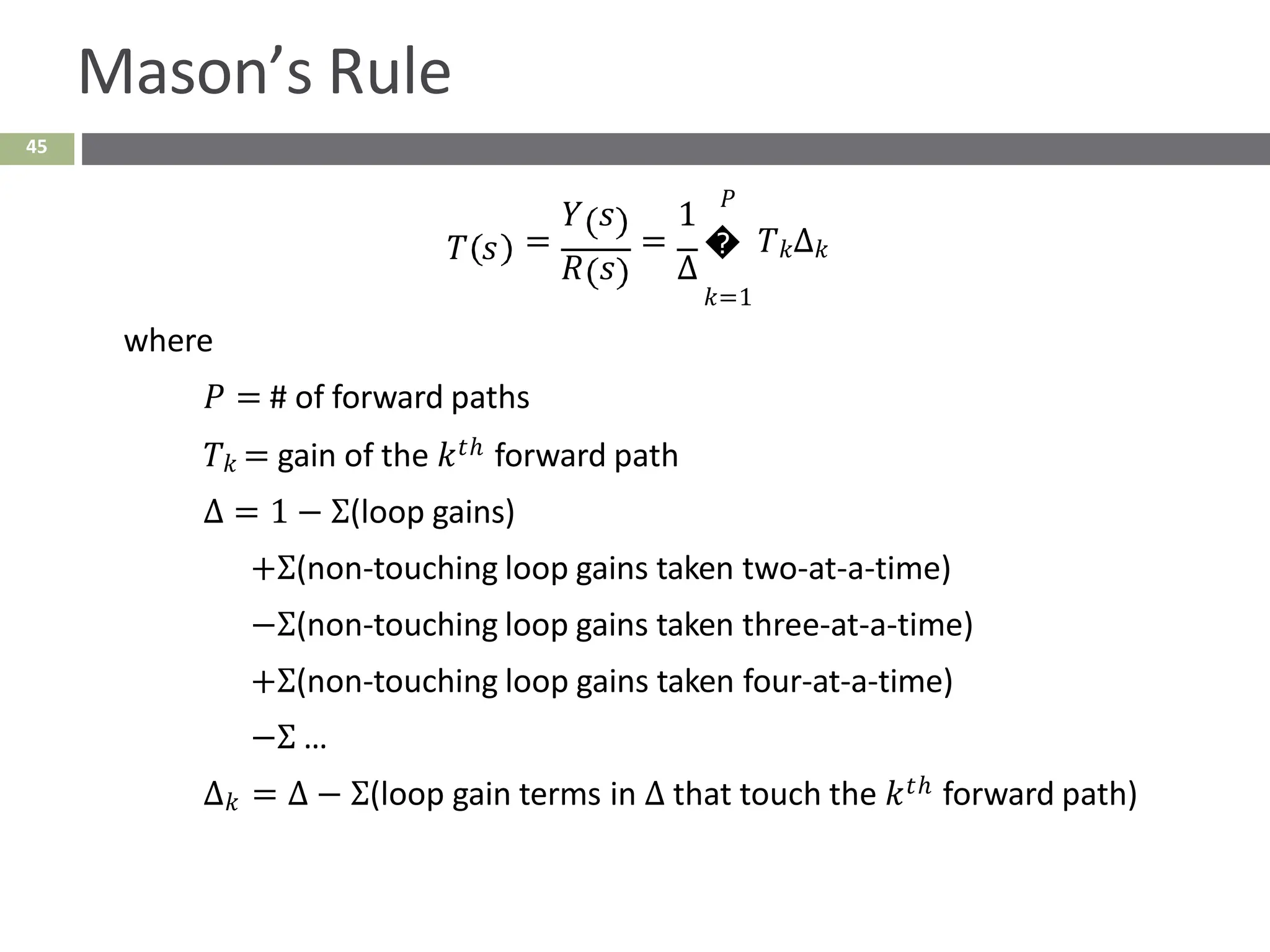

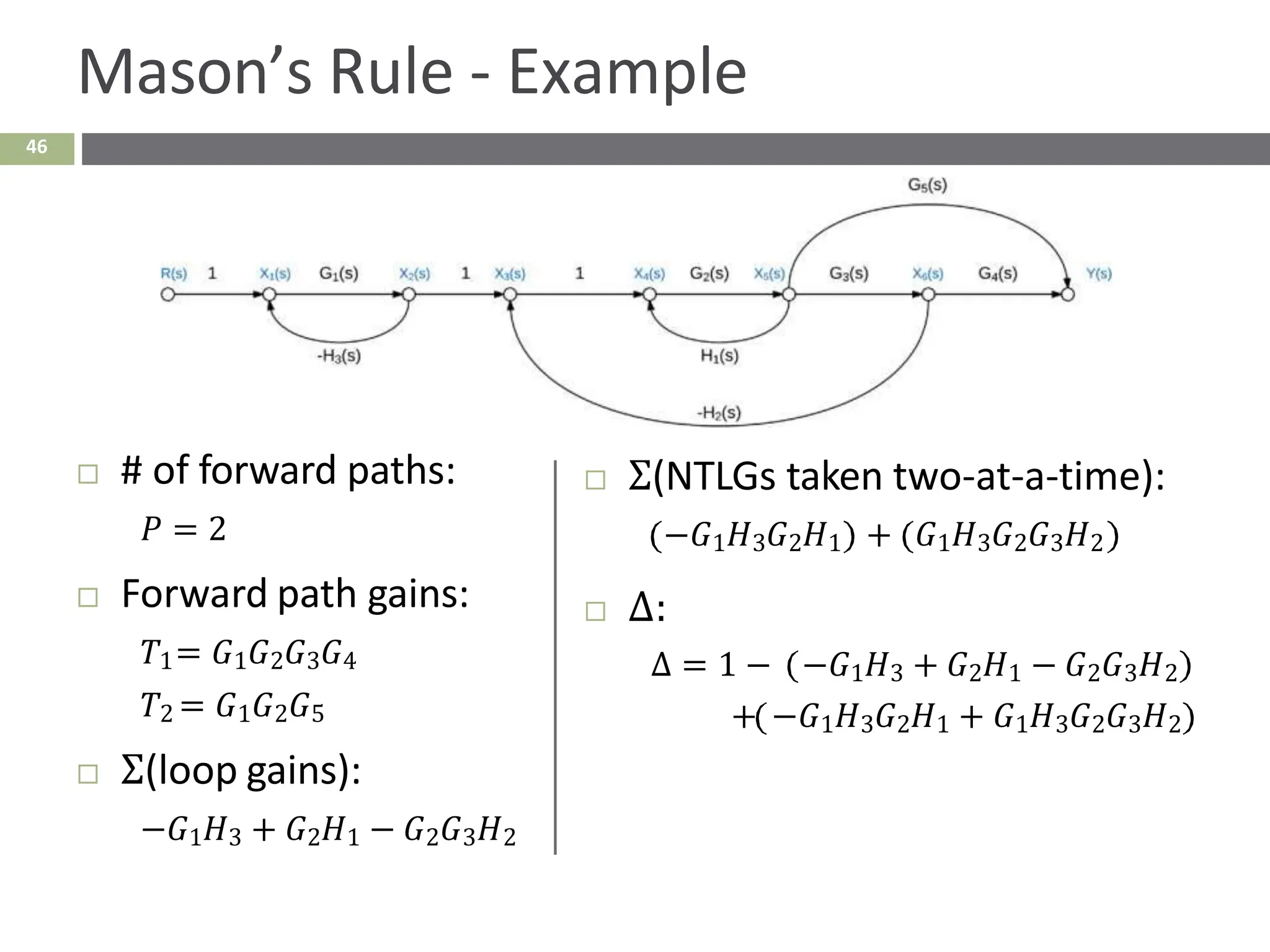

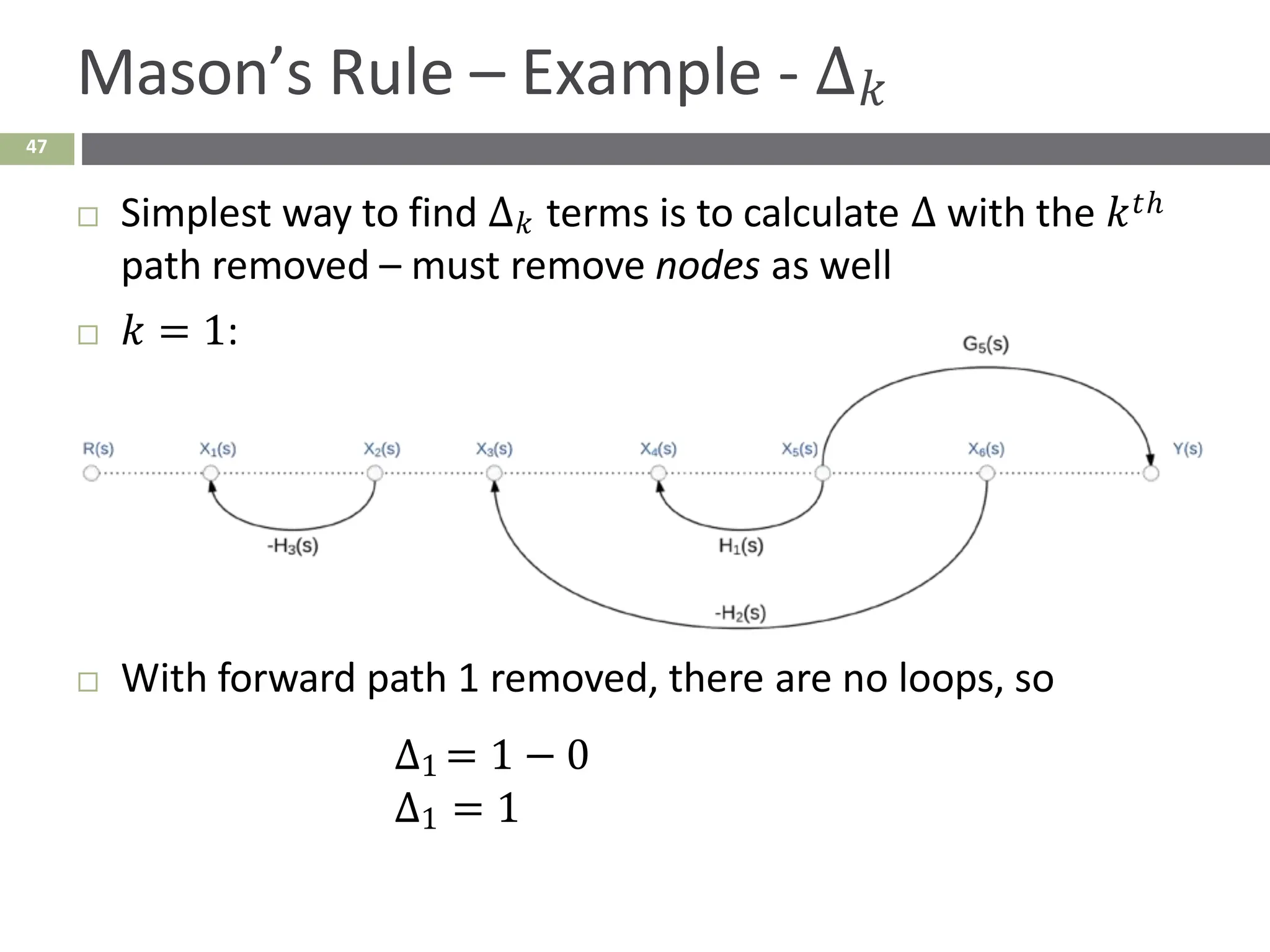

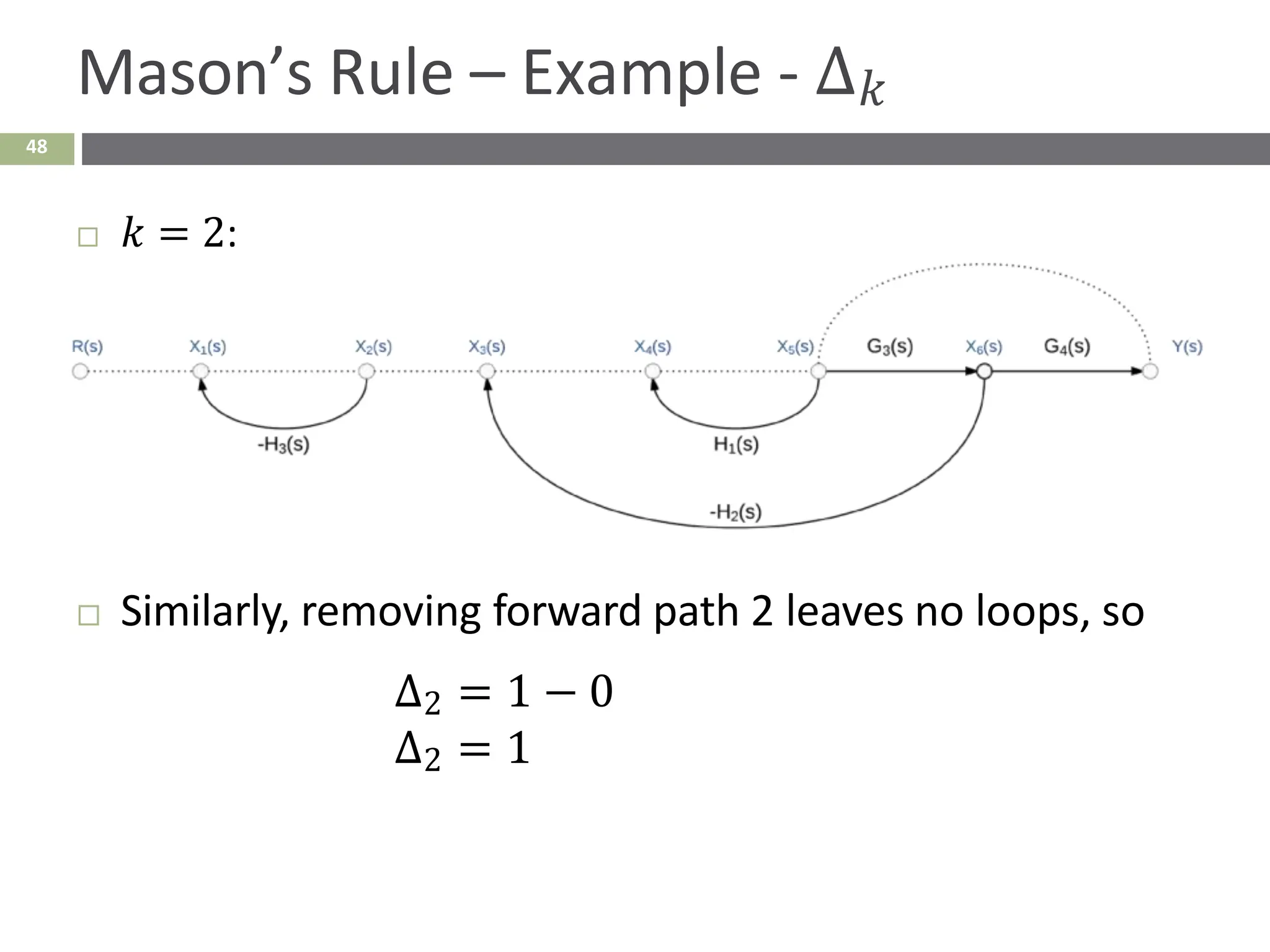

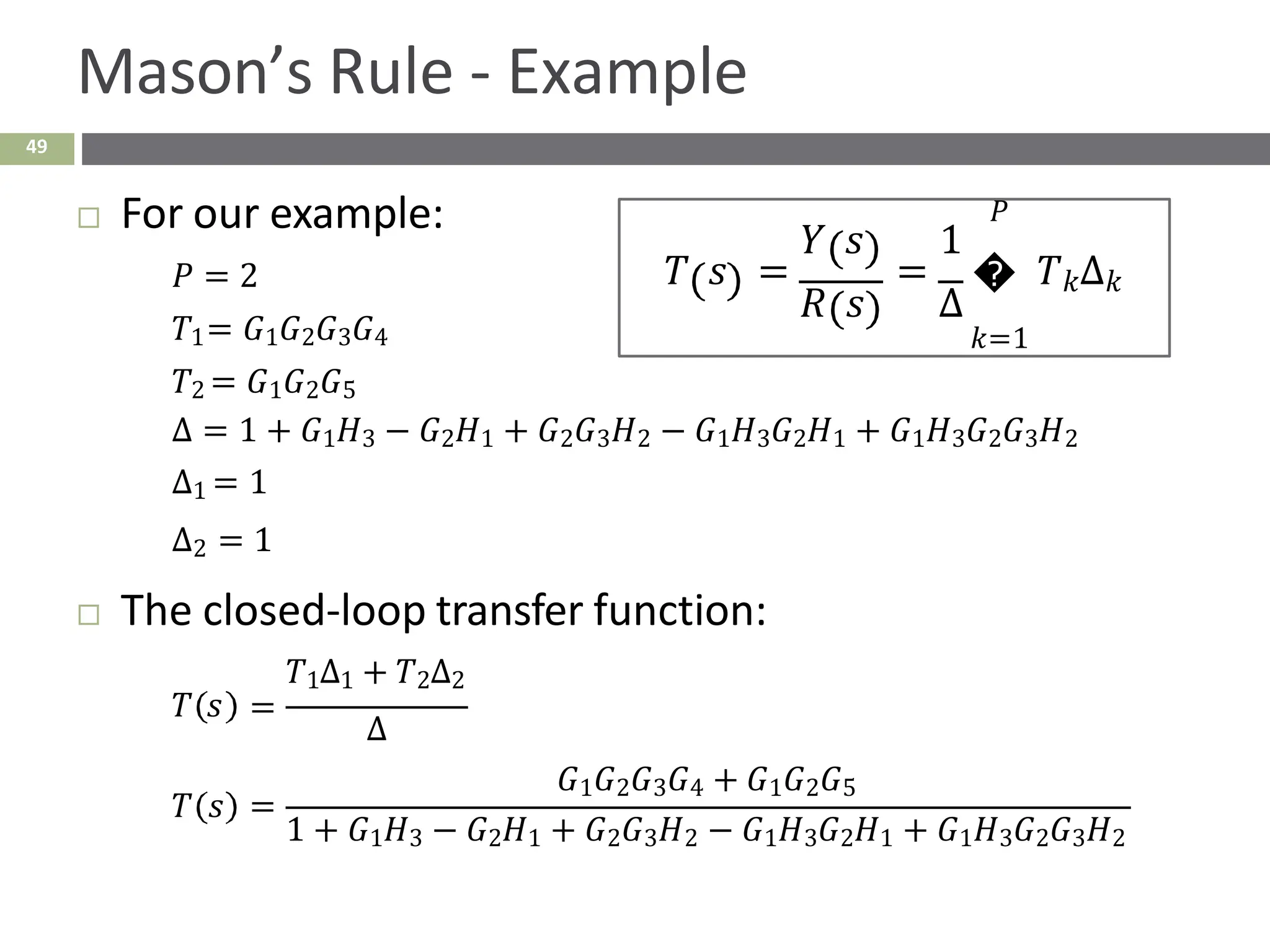

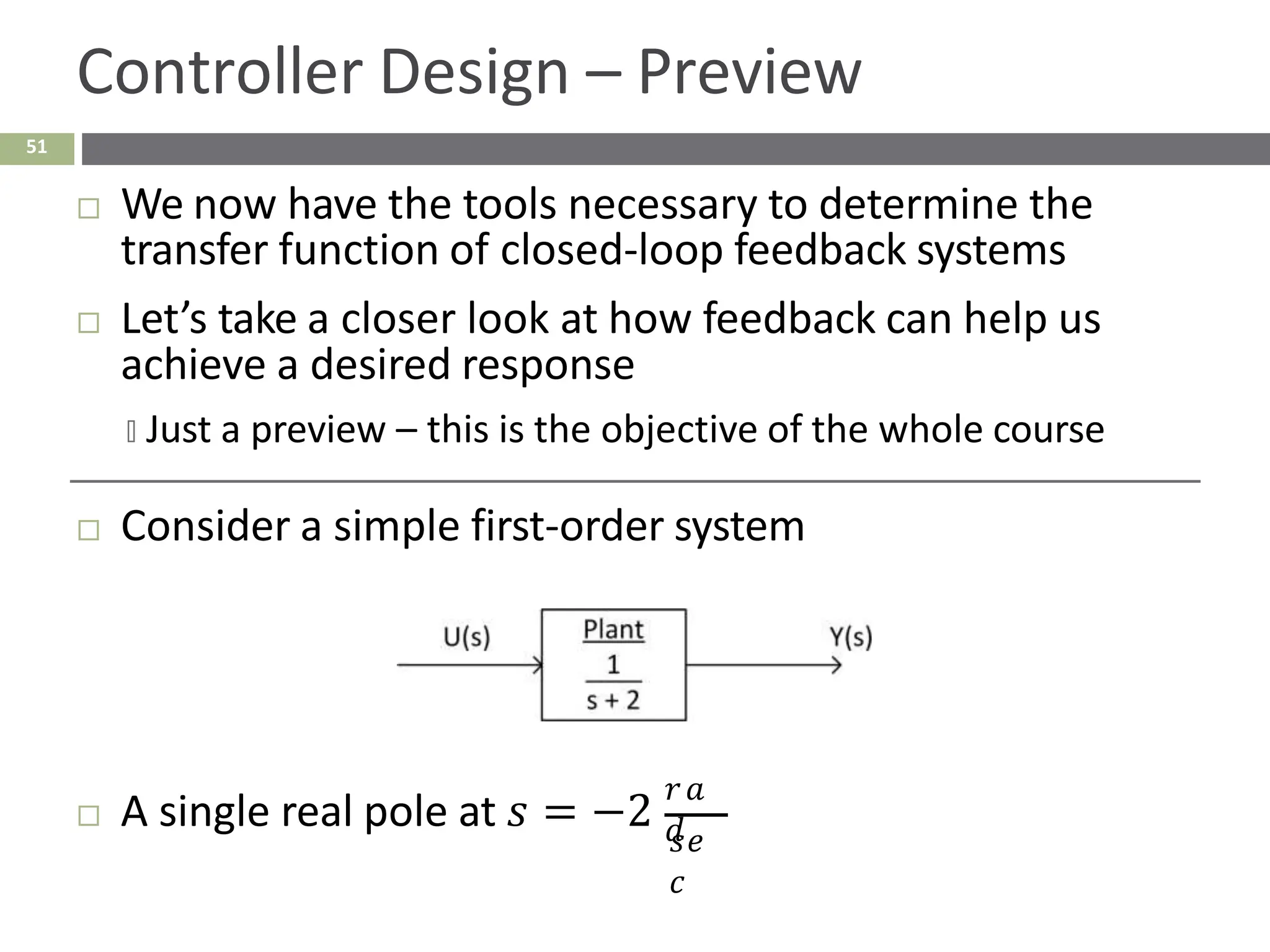

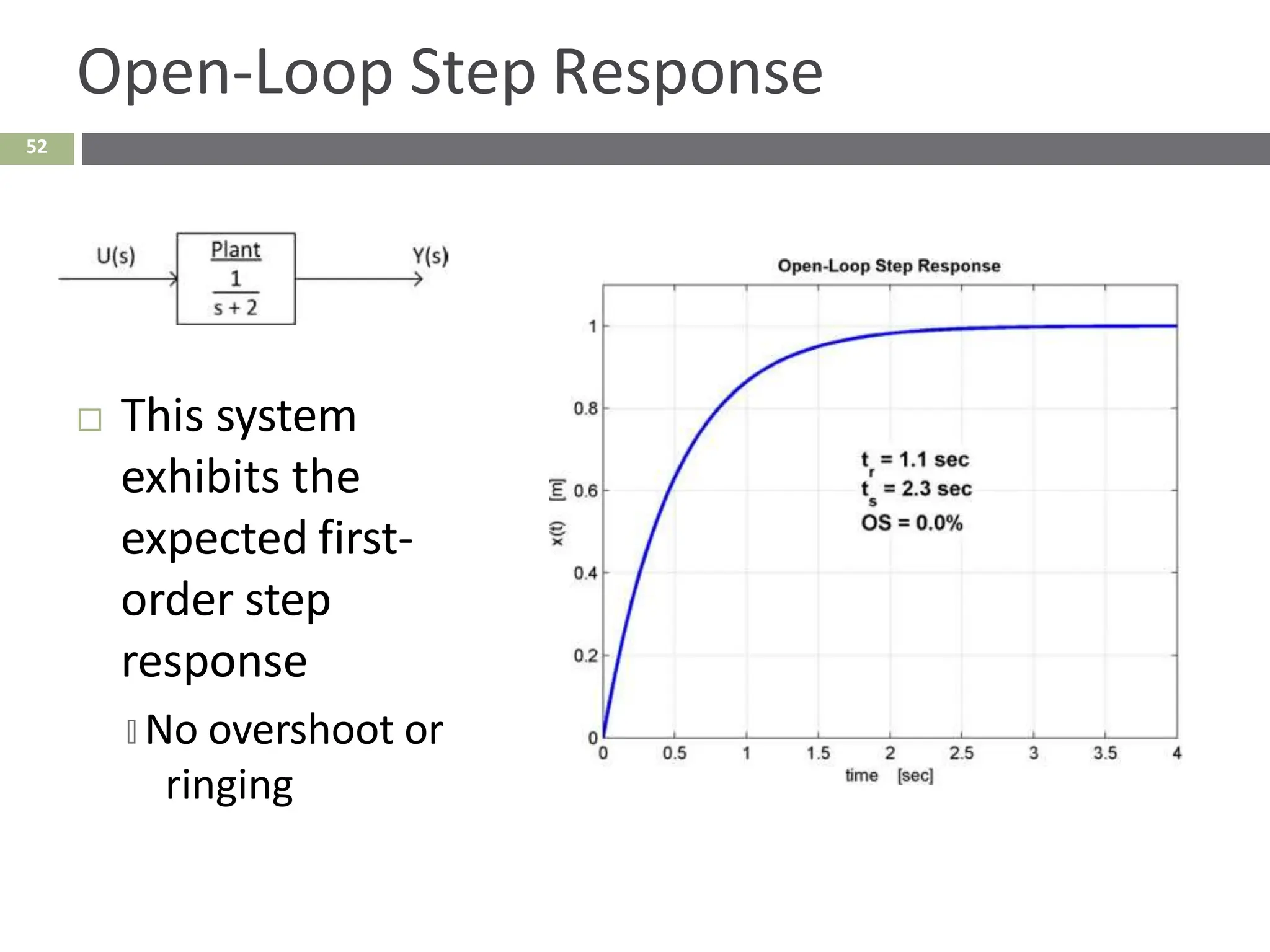

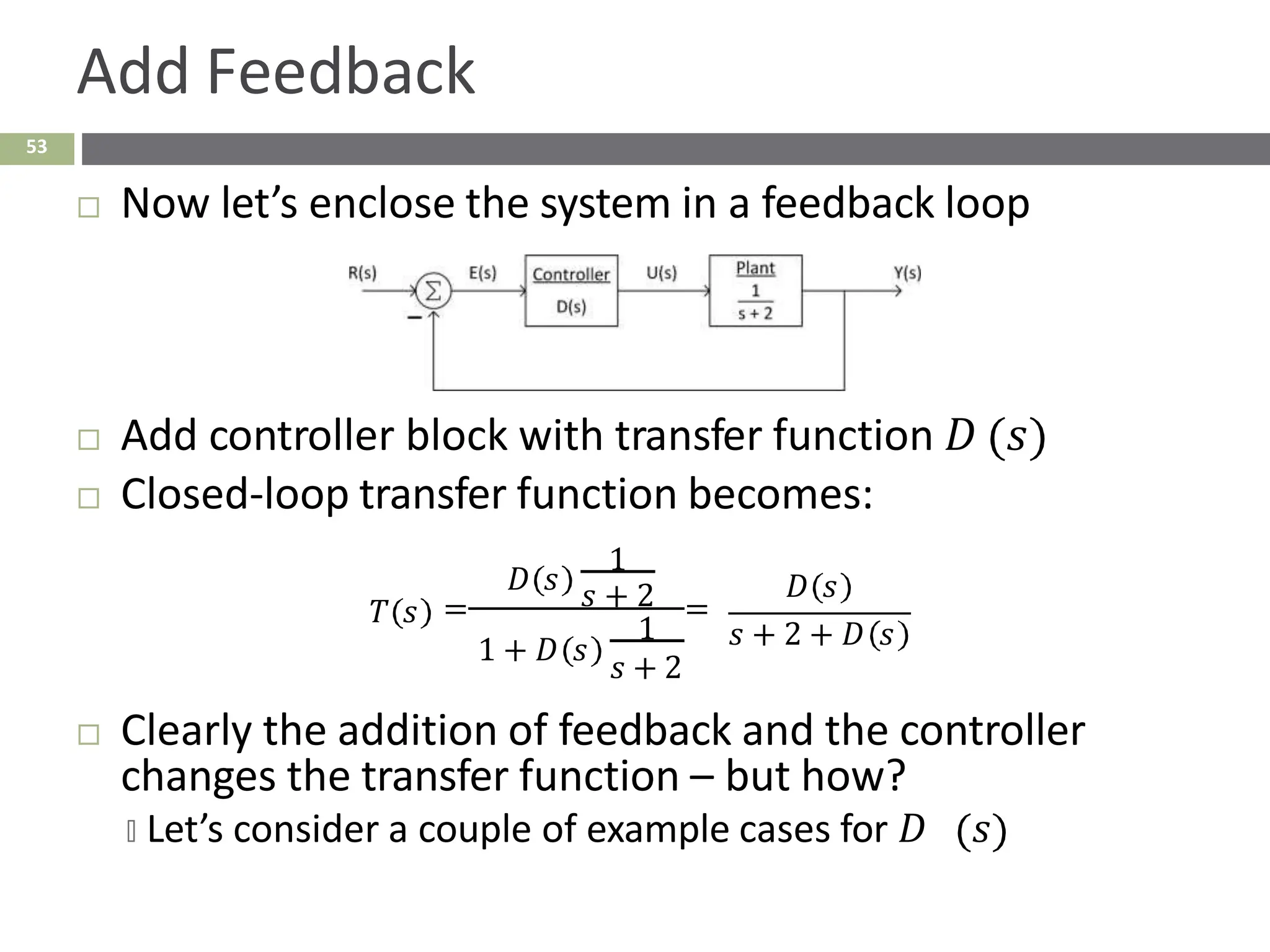

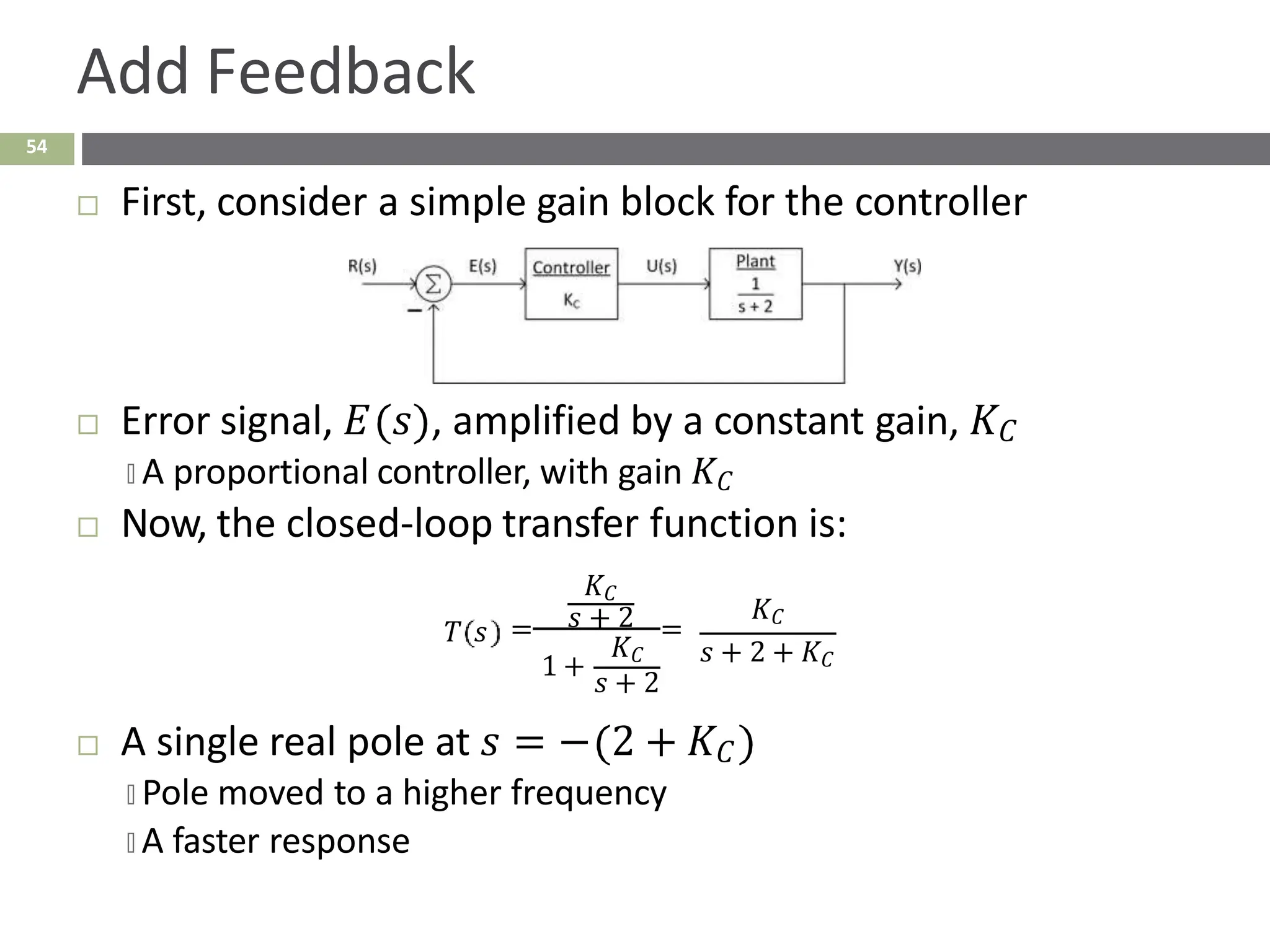

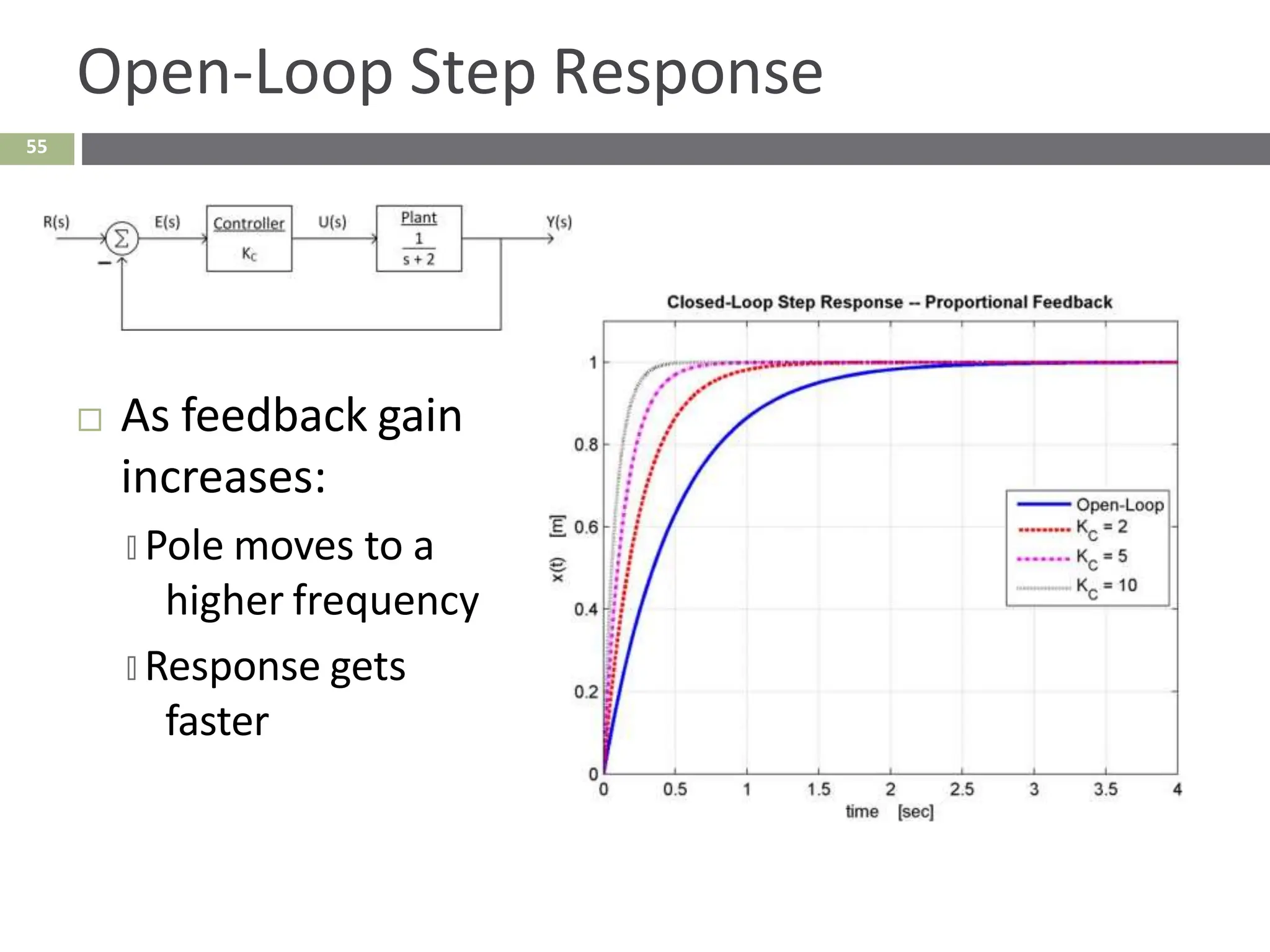

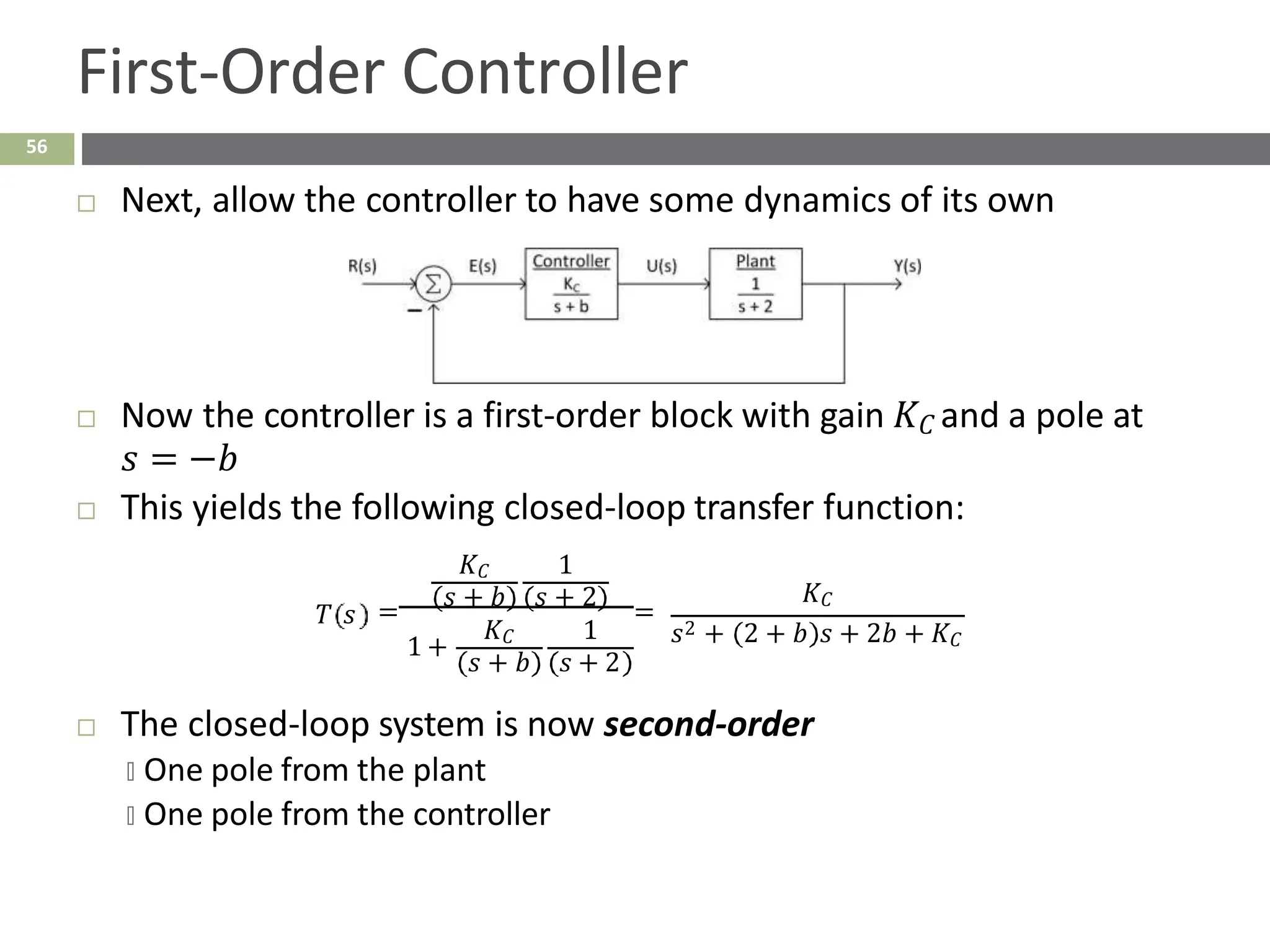

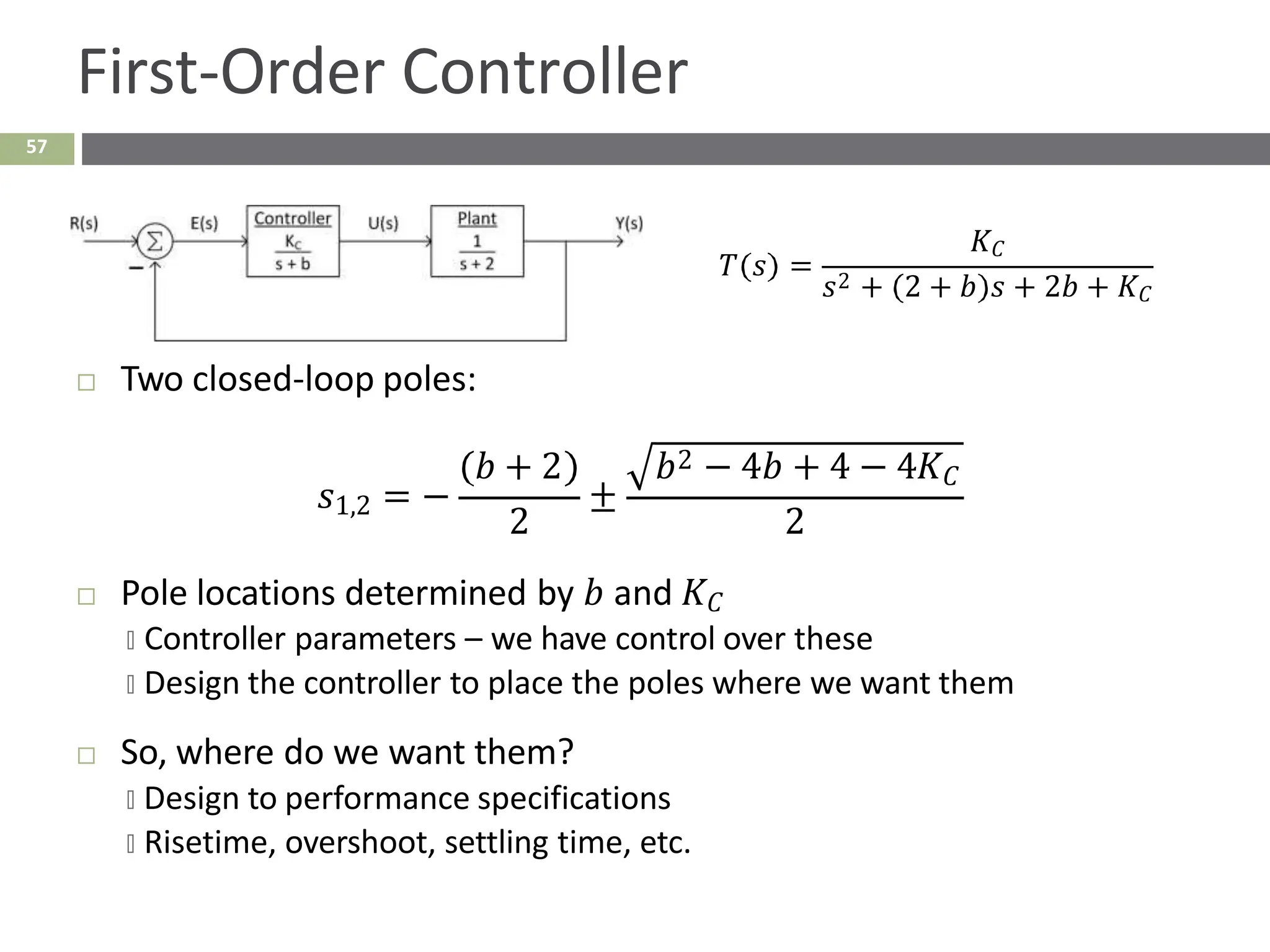

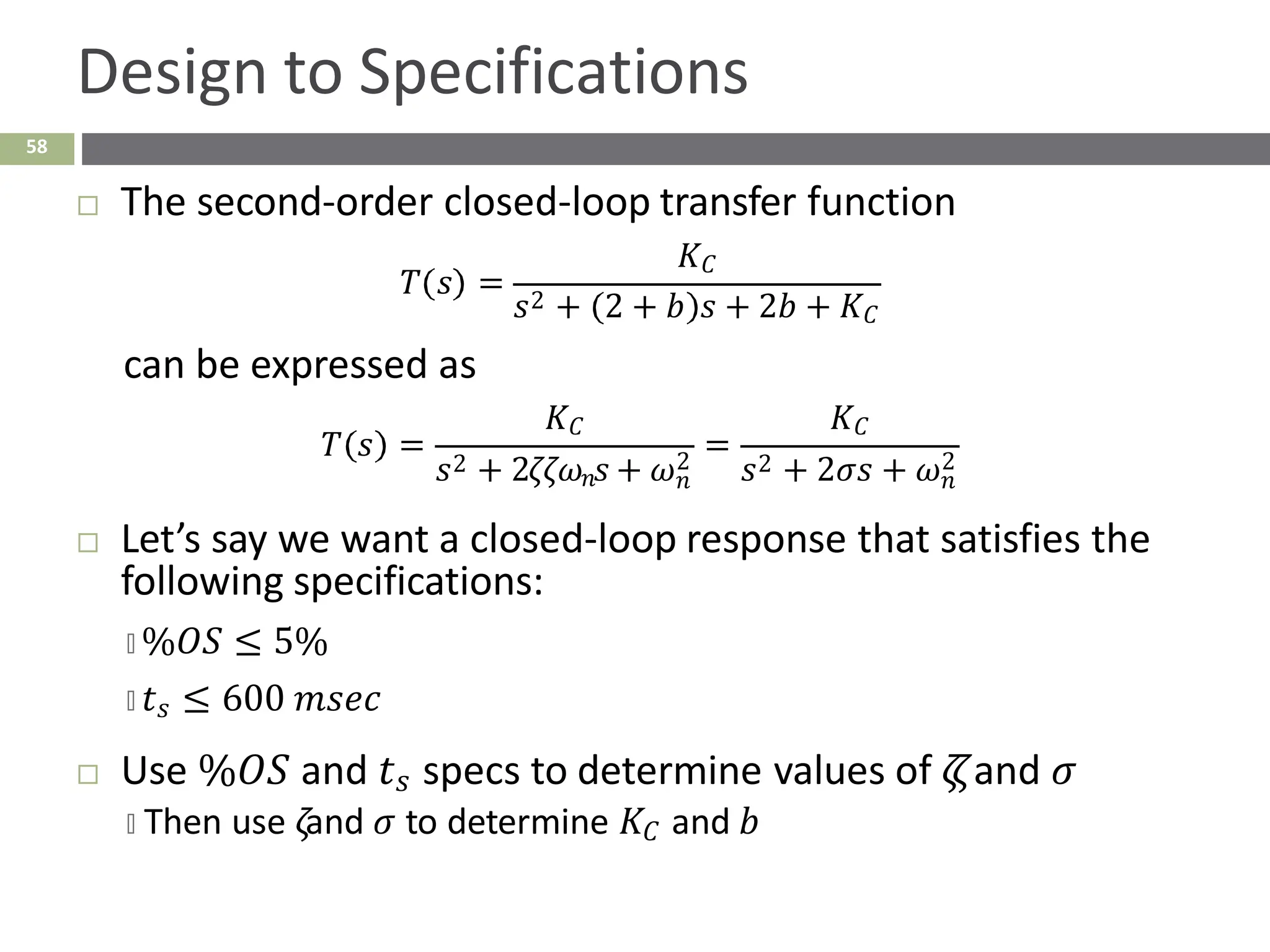

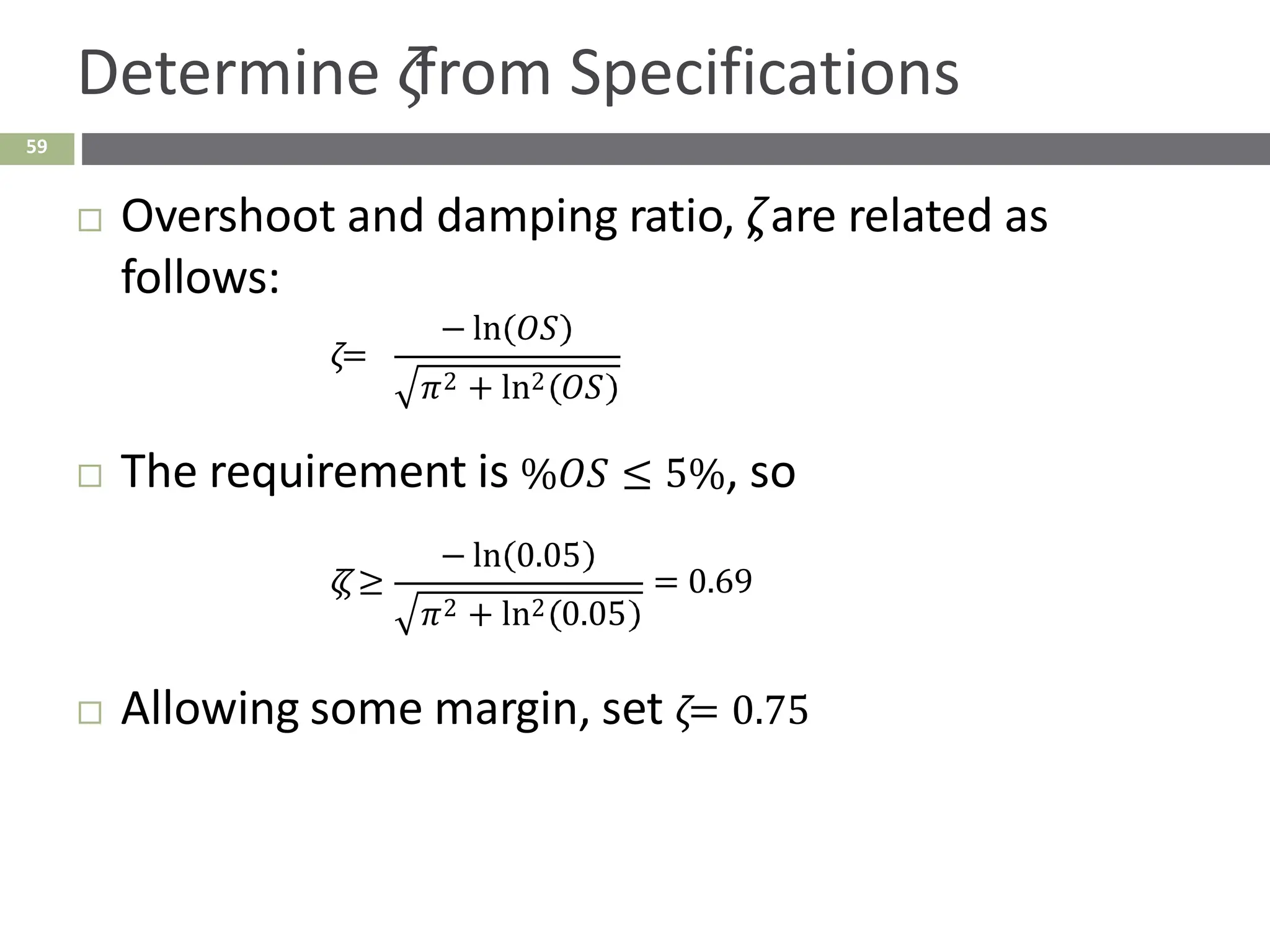

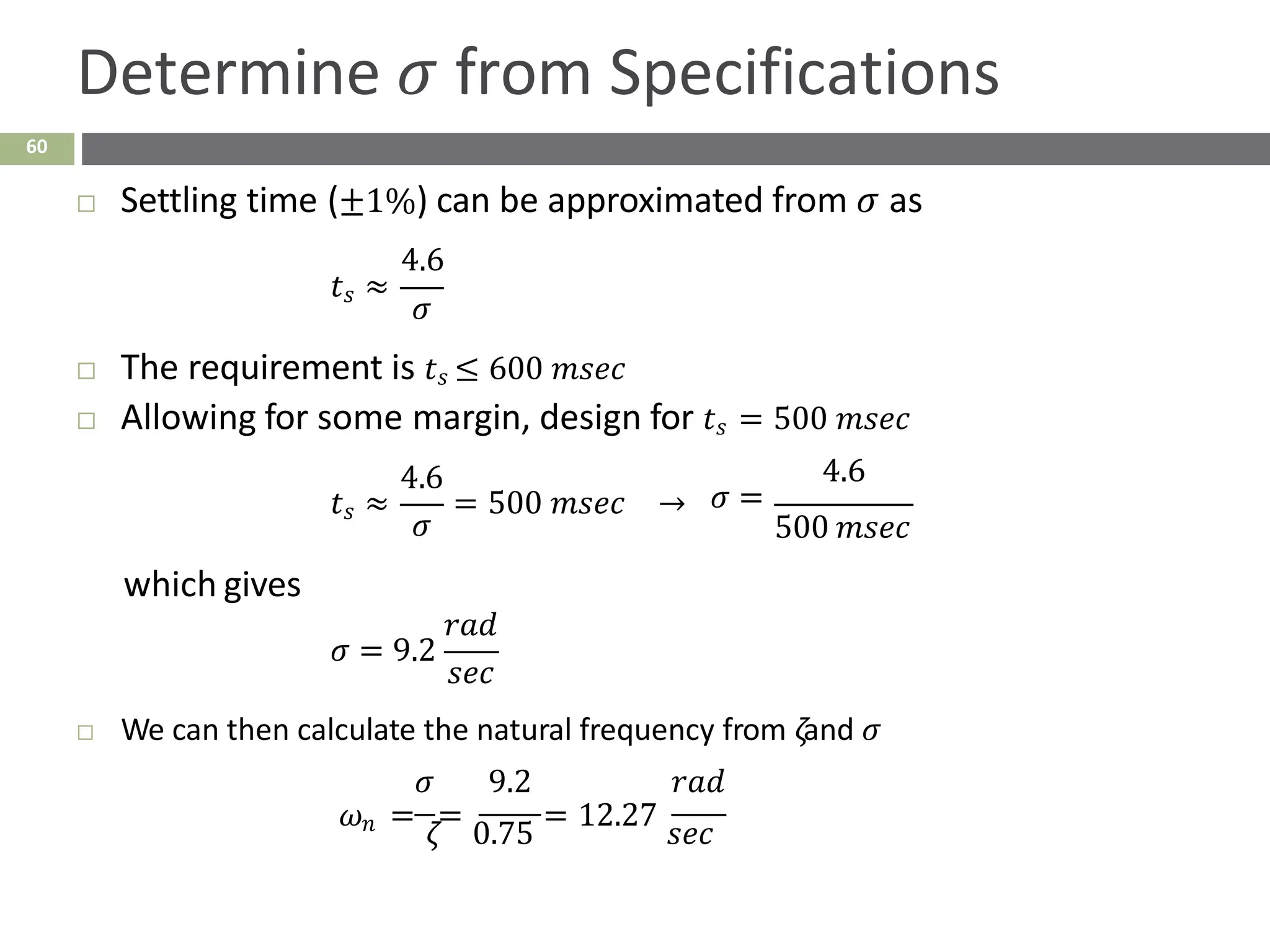

The document discusses the use of signal flow graphs as an alternative to block diagrams for representing systems, detailing how to convert block diagrams into signal flow graphs and simplifying them as needed. It introduces Mason’s rule for calculating overall transfer functions and provides examples of forward path gains, loop gains, and non-touching loops. The document also previews controller design concepts necessary for achieving desired feedback system responses, emphasizing the importance of pole placement and performance specifications.