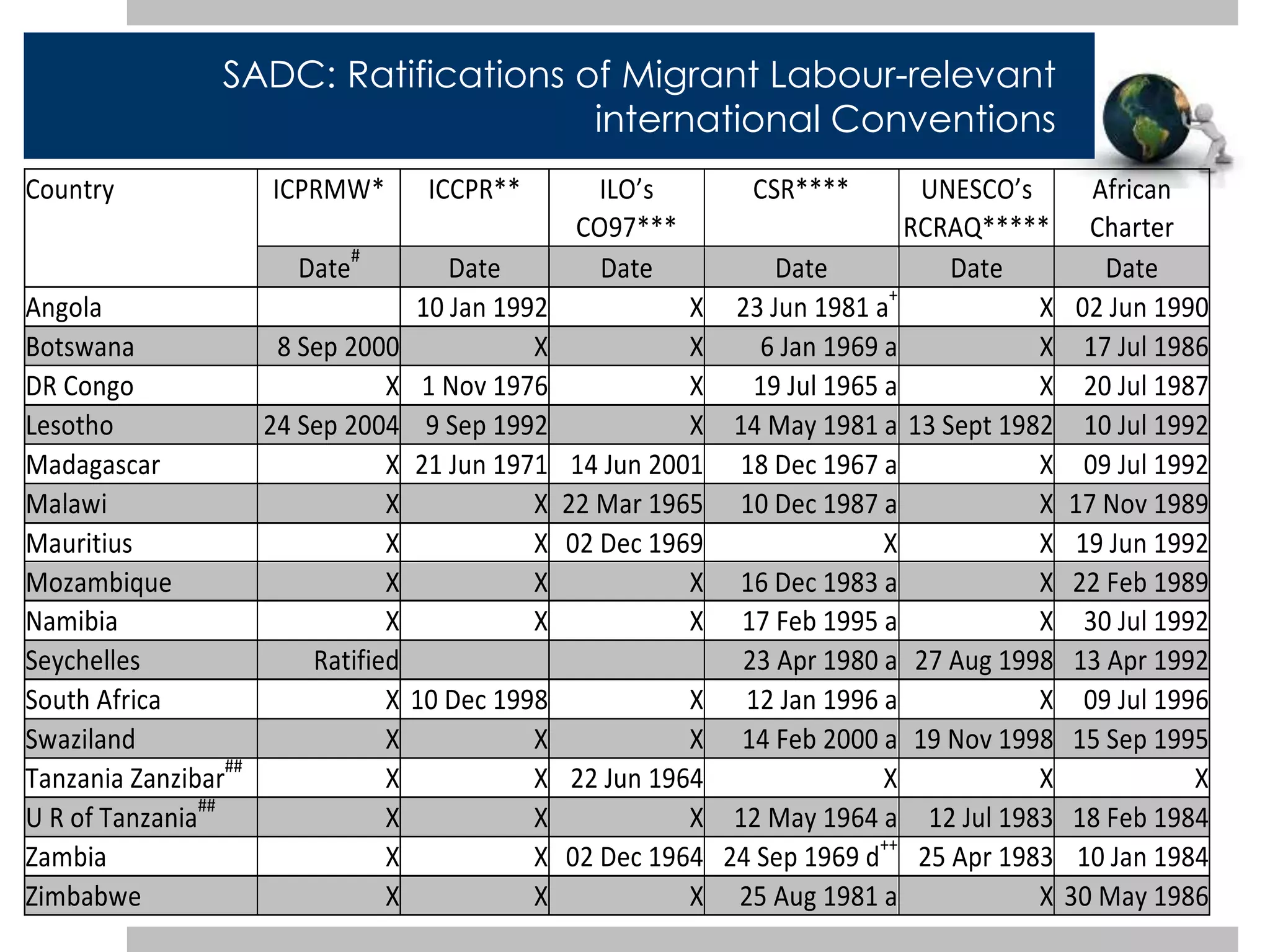

This document summarizes a research paper on prospects for freeing human mobility in Southern Africa. The research examines regional and bilateral policies on labor migration from Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Malawi to South Africa. It finds that while a free trade area exists in Southern Africa, human mobility is not fully free. The research aims to investigate existing frameworks and analyze South Africa's responses to migrant flows from neighboring countries in order to identify how free movement of people can be realized in the region. It concludes that Southern African states should formalize a rights-based regional labor migration mechanism and that South Africa should establish a multi-lateral framework to better manage issues like