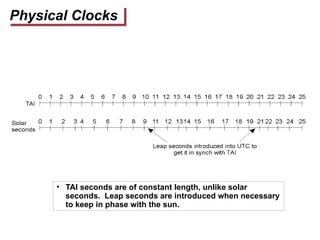

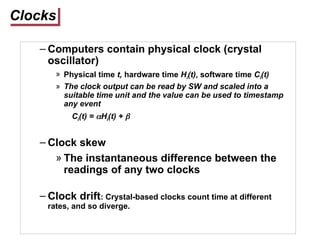

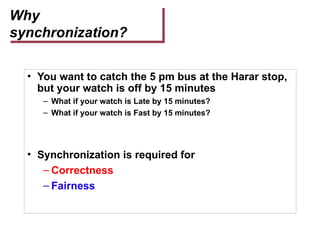

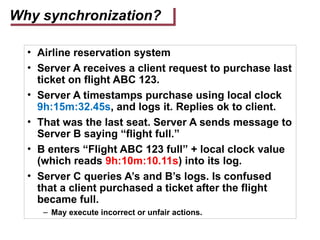

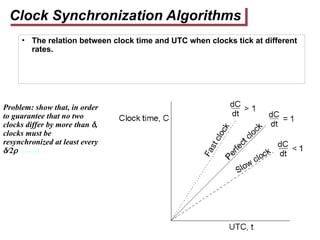

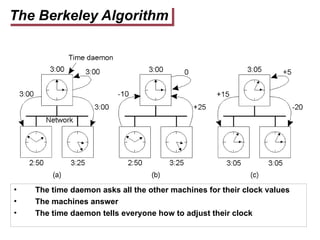

This document discusses synchronization in distributed systems, emphasizing the complexities of timekeeping and clock synchronization due to loose synchrony and varying clock rates. It explains the significance of accurate timing for event logging and fairness in processes, introducing concepts like UTC, NTP, clock drift, and various synchronization algorithms (Cristian’s and Berkeley's) along with their challenges and operational mechanisms. The importance of addressing propagation delays and establishing protocols to maintain time consistency across different systems is notably highlighted.