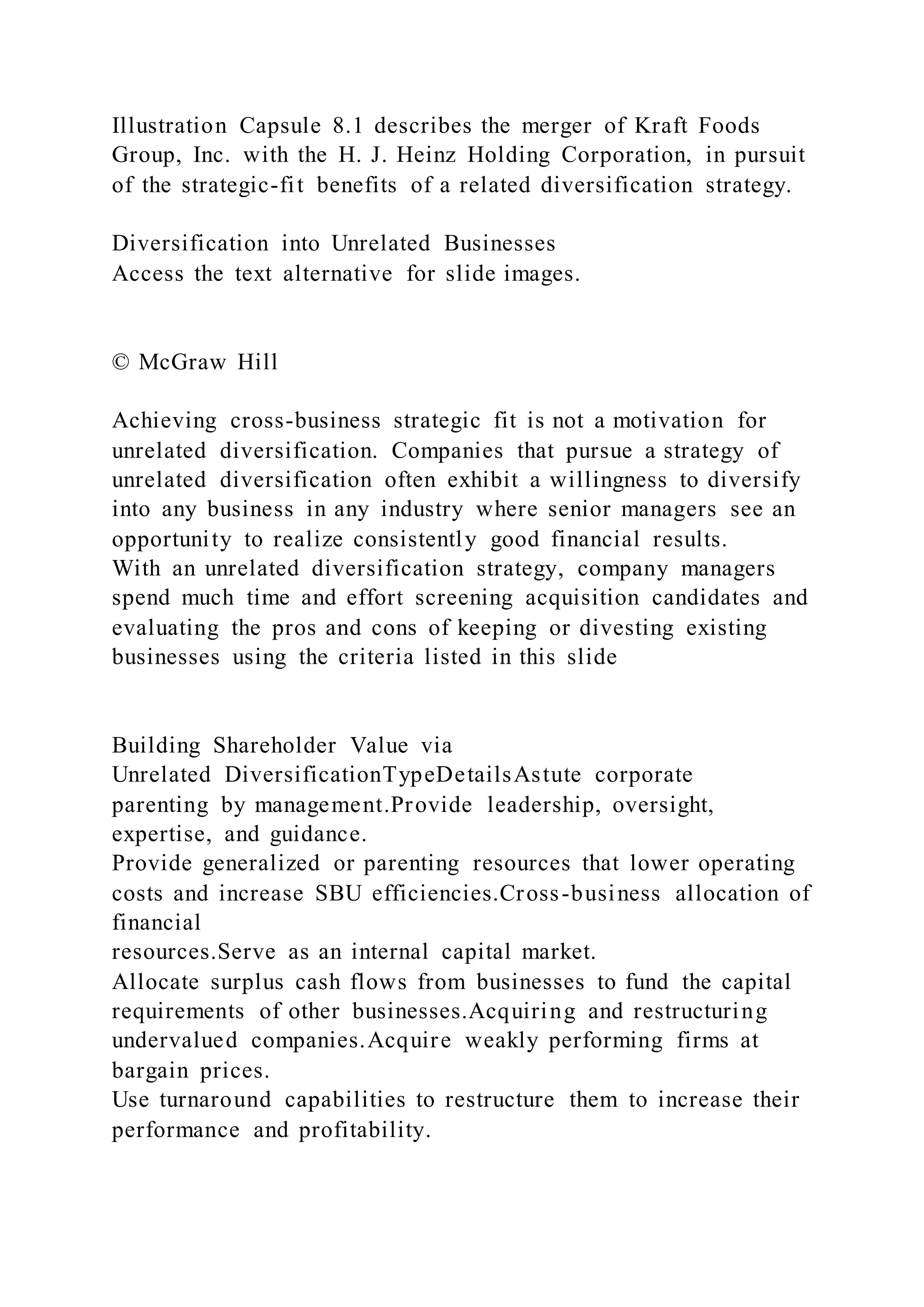

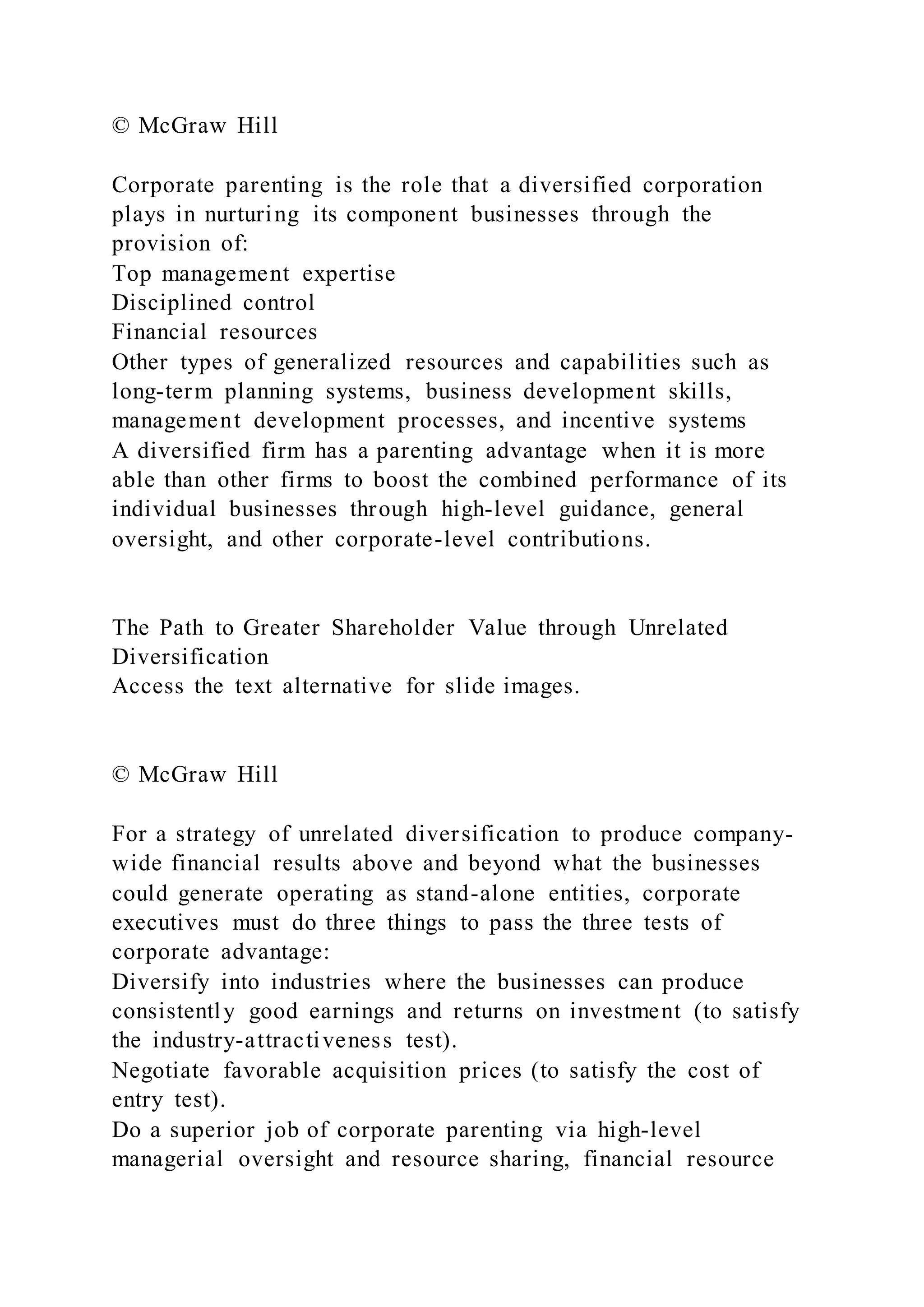

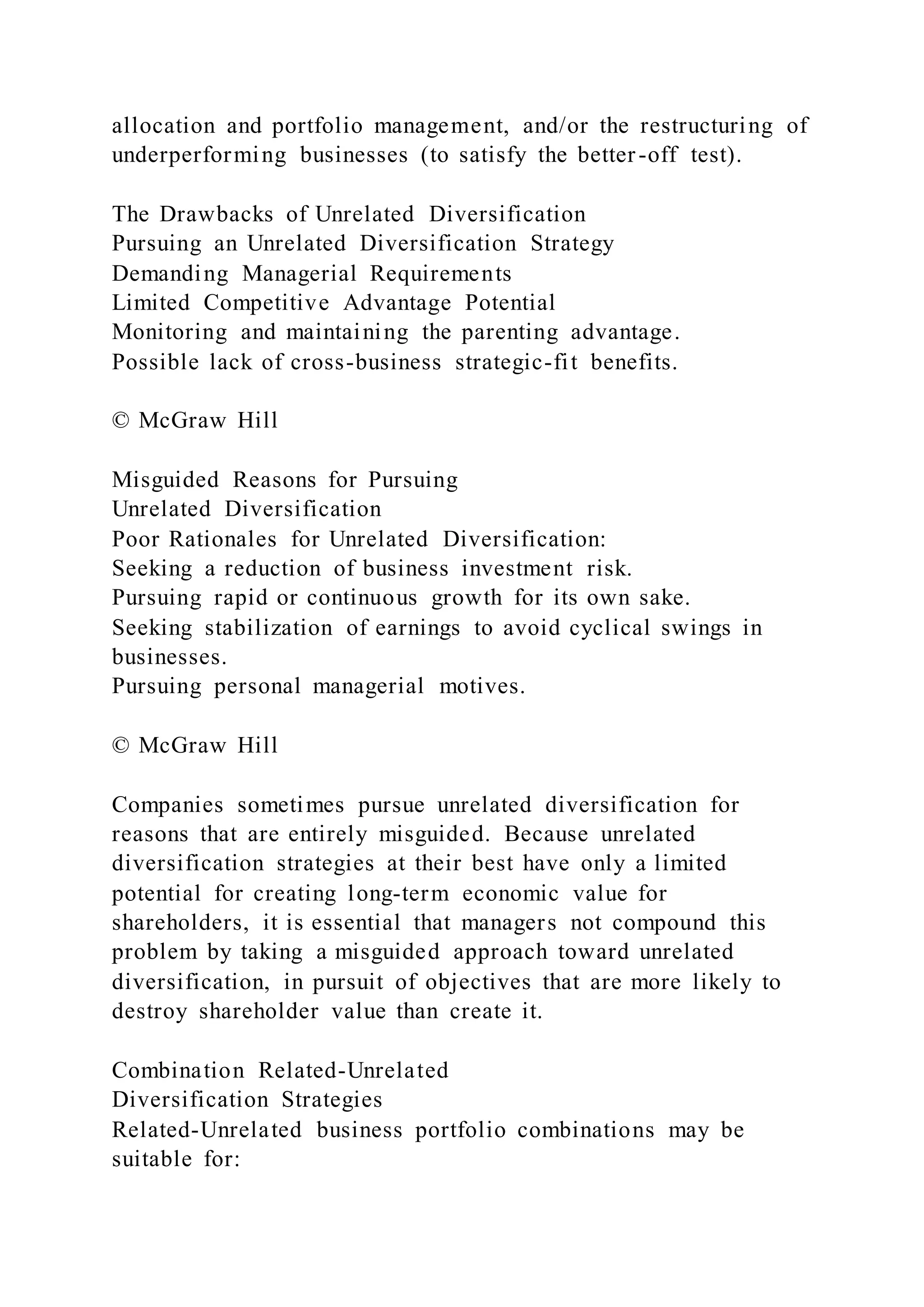

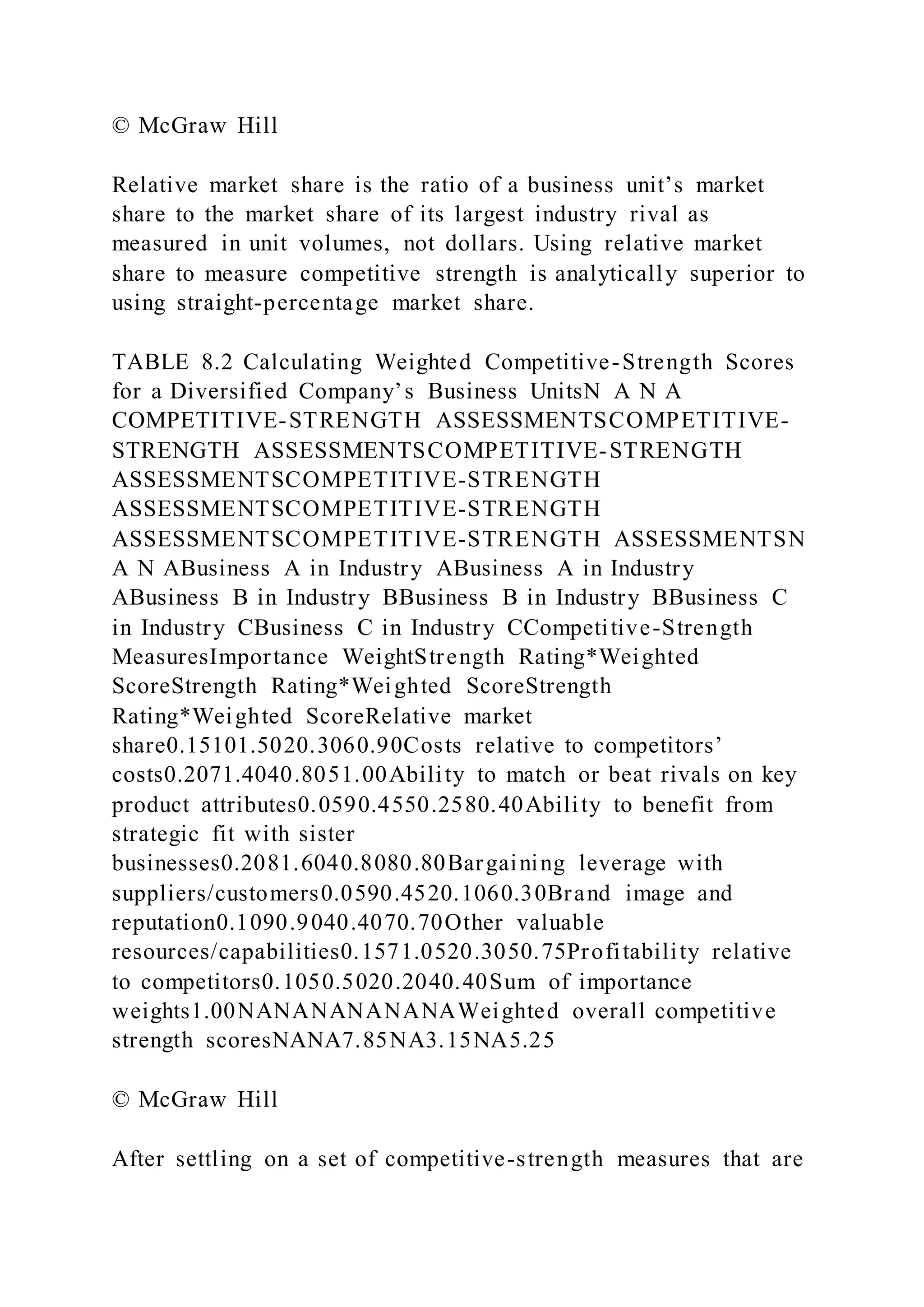

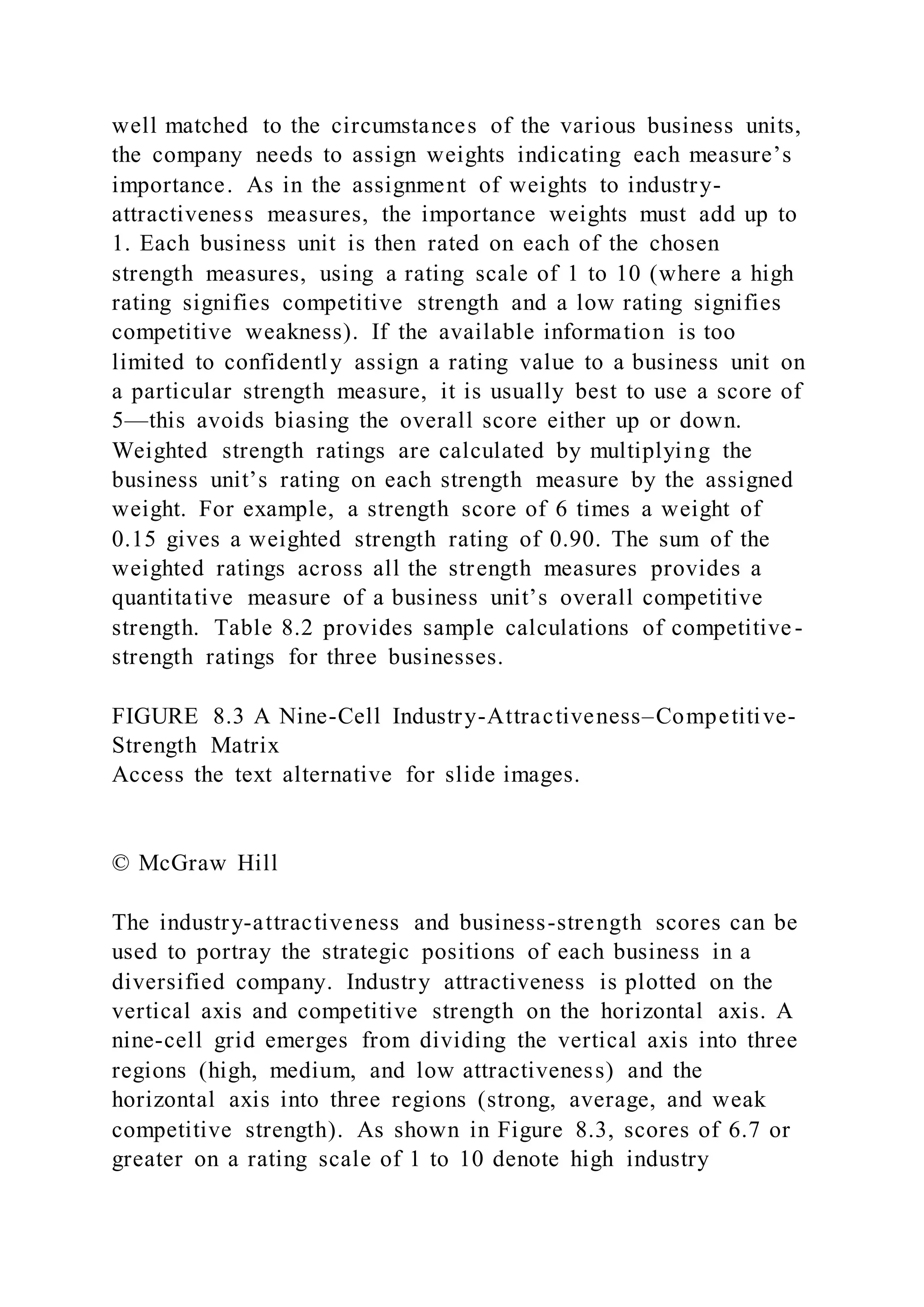

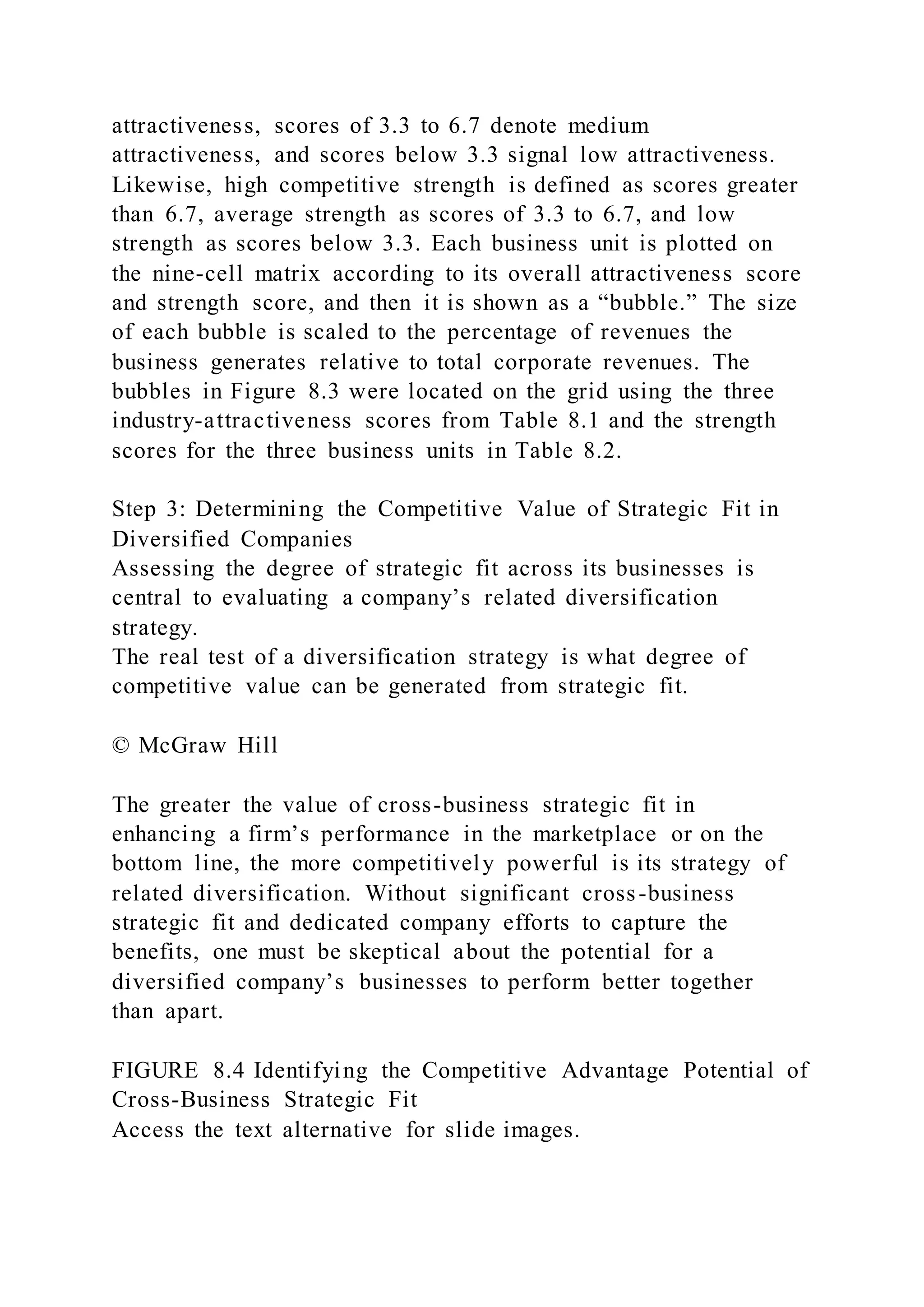

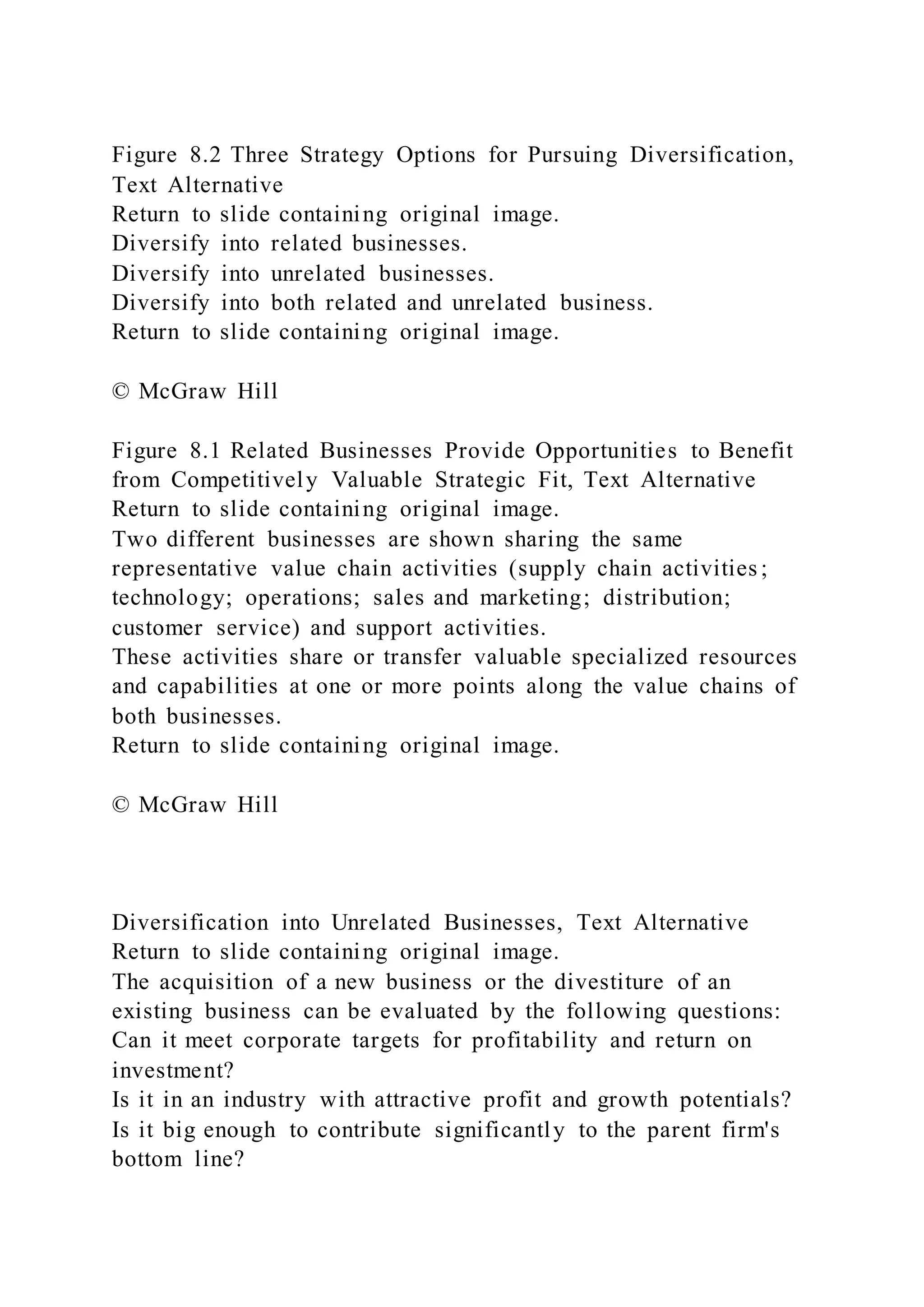

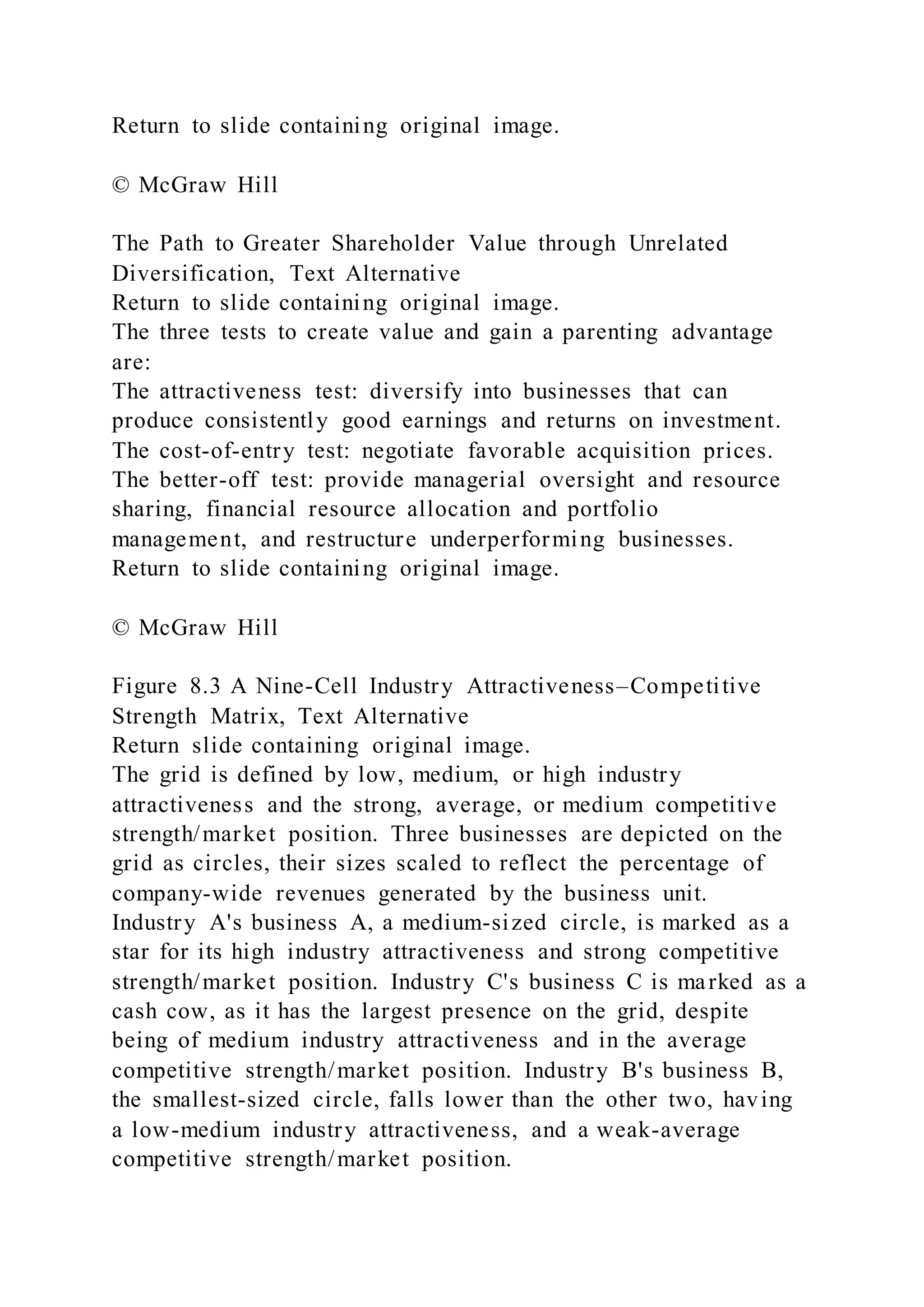

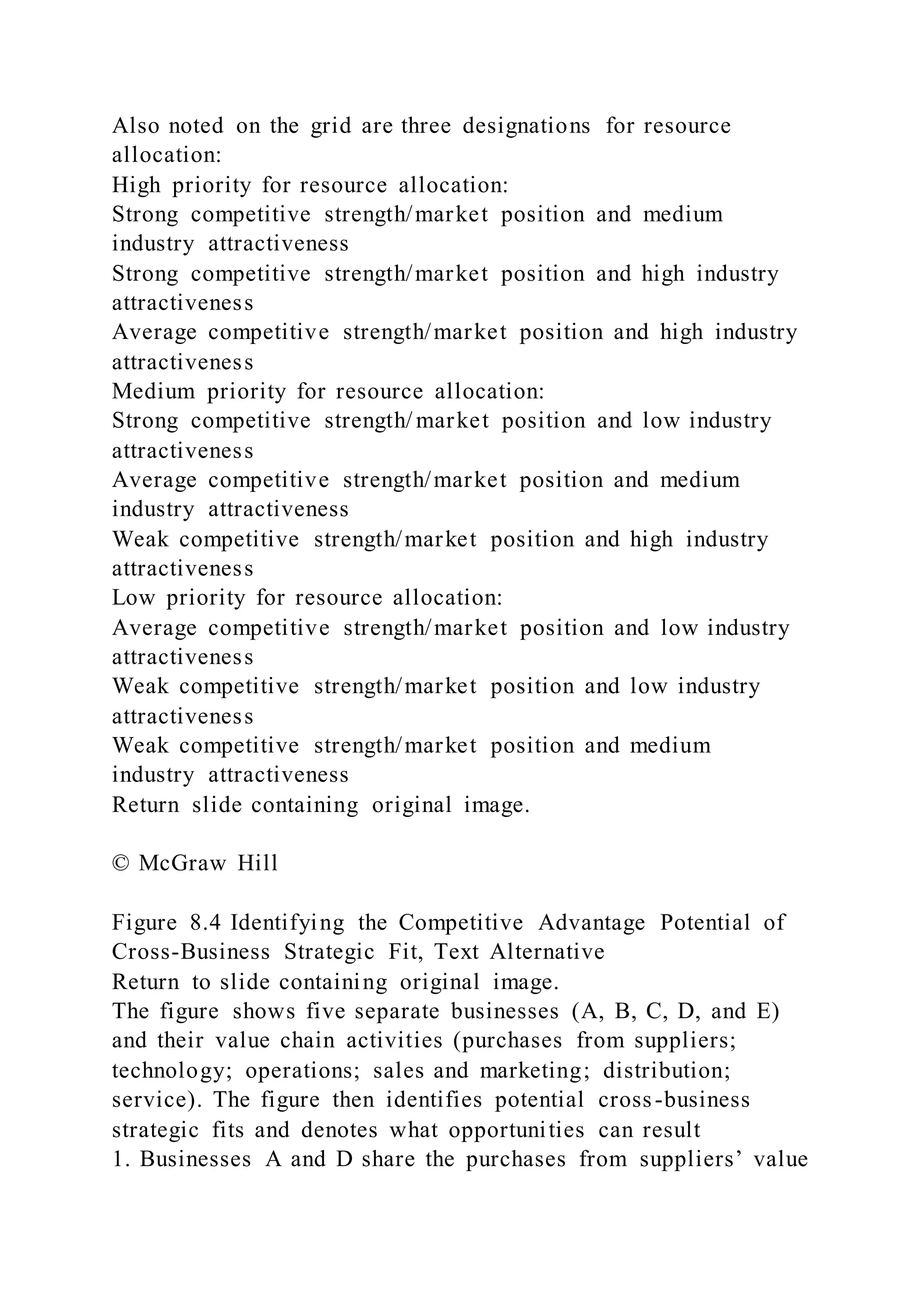

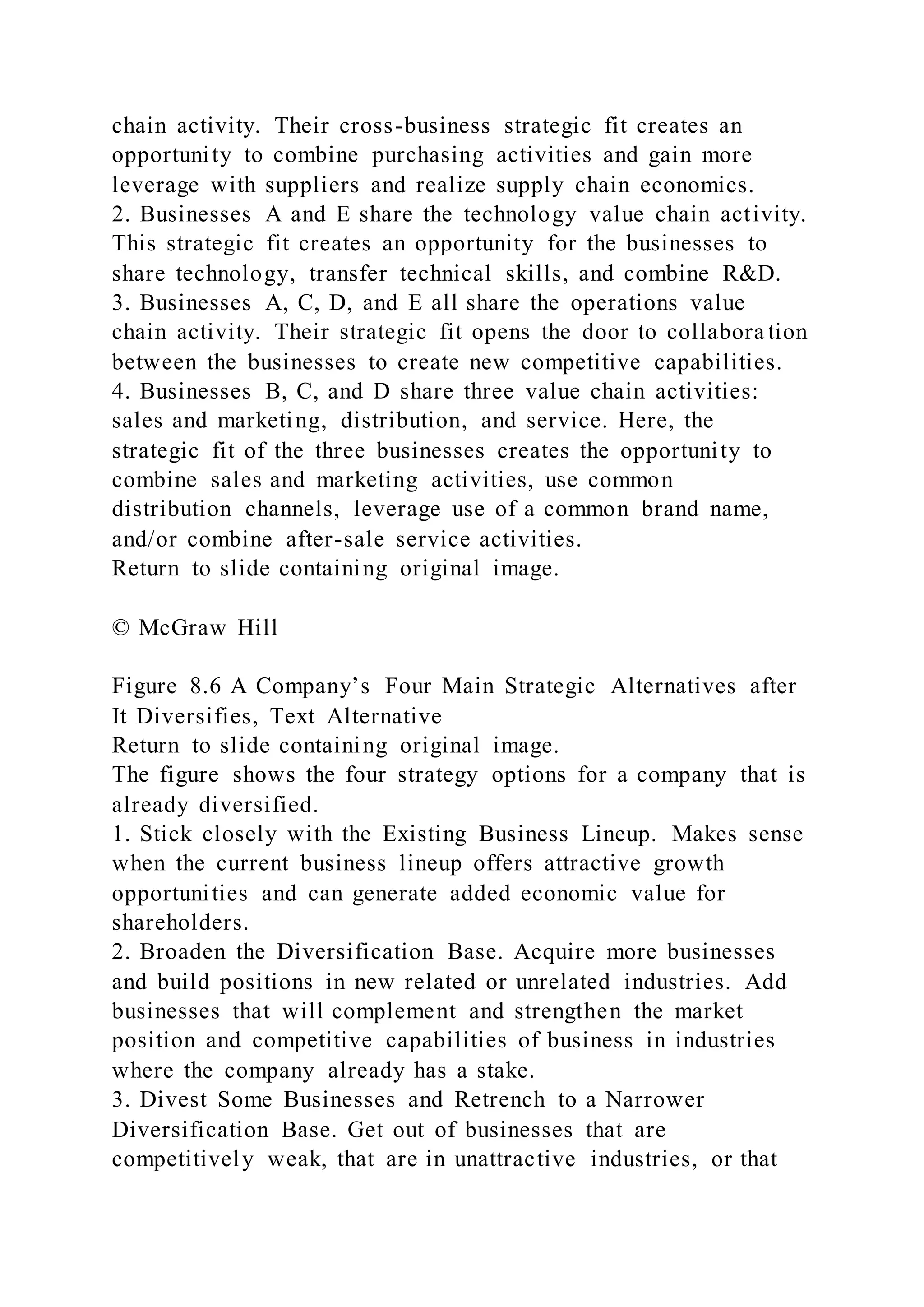

This chapter discusses corporate strategy for diversified multibusiness companies. It covers evaluating a company's diversification strategy, including pursuing related diversification through strategic fits across value chains. Related diversification can enhance shareholder value by leveraging specialized resources and capabilities between businesses. However, diversification only makes strategic sense if it passes tests showing the new industry is attractive, costs of entry can be overcome, and synergies will improve overall performance.