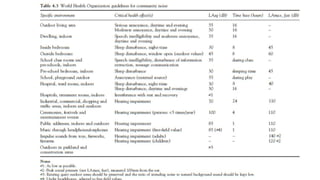

This document provides an overview of noise impact assessment for environmental impact assessments (EIAs). It discusses how virtually all development projects have noise impacts during construction and operation. It defines key noise terms and concepts, and outlines the legislative background for noise regulation. It describes the process for scoping and conducting baseline noise studies, predicting project noise impacts, identifying mitigation measures, and developing noise monitoring plans. The goal of noise assessment in EIAs is to quantify and objectively assess potential noise effects on people from projects.