This document provides an overview of bronchiolitis including pathogenesis, microbiology, risk factors, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment recommendations. Bronchiolitis is typically caused by viral infection, most commonly RSV, and causes inflammation in the small airways. Clinical diagnosis is based on symptoms of fever, cough and respiratory distress. Treatment focuses on supportive care like hydration and supplemental oxygen rather than medications like bronchodilators or steroids which studies have shown are not effective. High flow nasal cannula may help reduce respiratory distress. Prevention involves reducing exposure to tobacco smoke which increases risk and severity.

![■ Clinical presentation: Fever (usually ≤38.3ºC [101ºF]), cough, and respiratory distress

(eg, increased respiratory rate, retractions, increased work of breathing, wheezing,

crackles, hypoxia). It often is preceded by a one- to three-day history of upper

respiratory tract symptoms (eg, nasal congestion and/or discharge)

■ Clinical course:Typical illness with bronchiolitis begins with upper respiratory tract

symptoms, followed by lower respiratory tract signs and symptoms on days two to

three, which peak on days three to five and then gradually resolve.

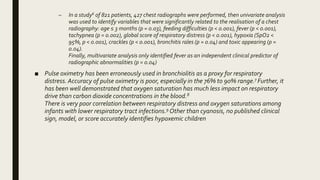

In a systematic review of four studies including 590 children with bronchiolitis, the

mean time to resolution of cough ranged from 8 to 15 days.1

■ Dehydration a major complication: Infants with bronchiolitis may have difficulty

maintaining adequate hydration because of increased fluid needs (related to fever and

tachypnea), decreased oral intake (related to tachypnea and respiratory

distress), and/or vomiting2.They should be monitored for dehydration (eg, increased

heart rate, dry mucosa, sunken fontanelle, decreased urine output](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiolitis-200527193507/85/Bronchiolitis-4-320.jpg)

![■ Clinicians should not administer systemic corticosteroids to infants with a diagnosis of

bronchiolitis in any setting (Evidence Quality:A; Recommendation Strength: Strong

Recommendation).3

■ Clinicians may choose not to administer supplemental oxygen if the oxyhemoglobin

saturation exceeds 90% in infants and children with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis

(Evidence Quality: D; Recommendation Strength:Weak Recommendation [based on

low-level evidence and reasoning from first principles])3

■ Clinicians should not administer systemic corticosteroids to infants with a diagnosis of

bronchiolitis in any setting (Evidence Quality:A; Recommendation Strength: Strong

Recommendation).3

■ Use of humidified, heated, high-flow nasal cannula to deliver air-oxygen mixtures

provides assistance to infants with bronchiolitis through multiple proposed

mechanisms.16 There is evidence that high-flow nasal cannula improves physiologic

measures of respiratory effort and can generate continuous positive airway pressure in

bronchiolitis.17-20

Clinical evidence suggests it reduces work of breathing21,22 and may decrease need for

shown by the retrospective study from Australia,23 which showed a decline in

intubation rate in the subgroup of infants with bronchiolitis from 37% to 7% after the

introduction of high-flow nasal cannula](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiolitis-200527193507/85/Bronchiolitis-12-320.jpg)