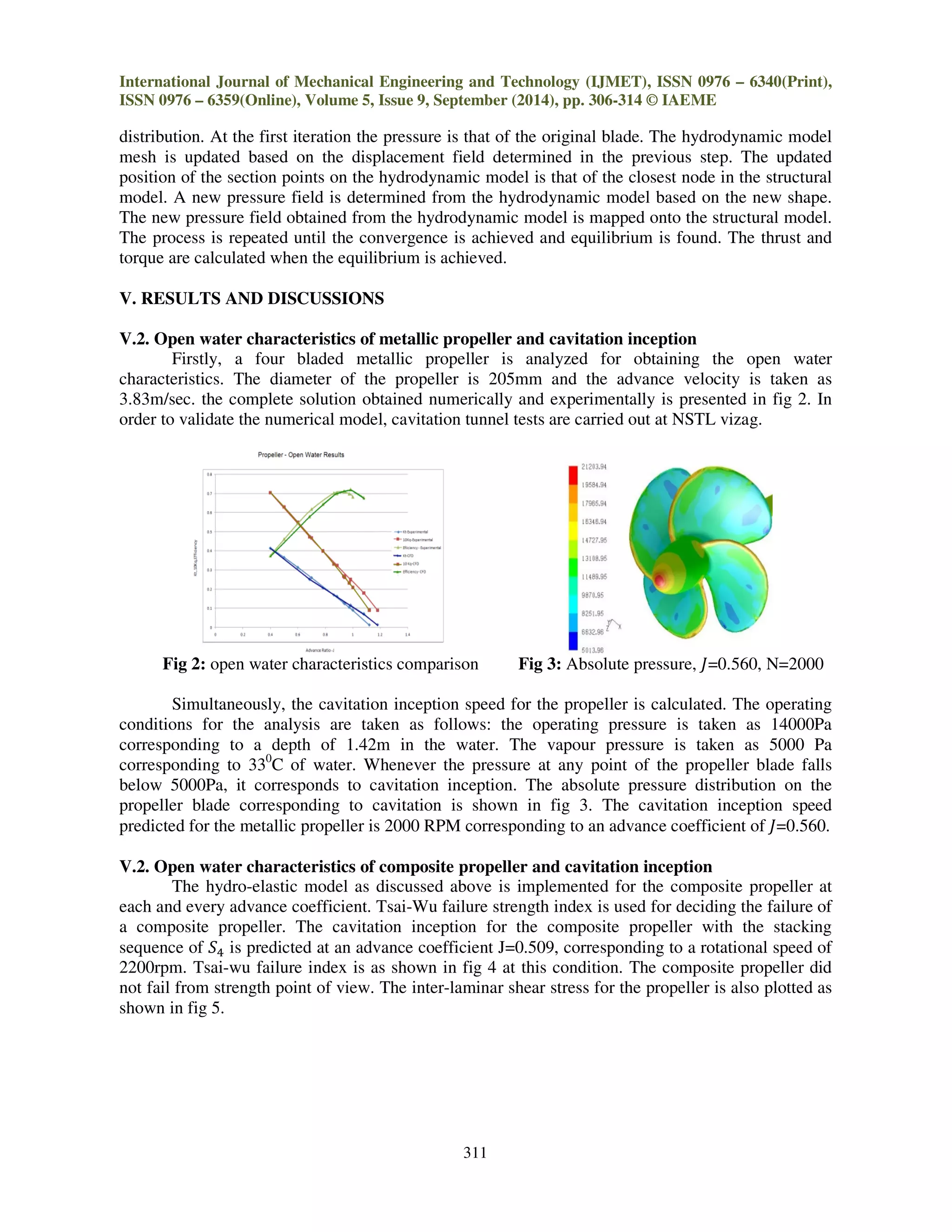

The document discusses the design and performance enhancement of composite marine propellers by utilizing bend-twist coupling, which helps mitigate cavitation effects associated with traditional metallic propellers. Through fluid structure interaction simulations and experimental validations in cavitation tunnels, it is shown that composite propellers can offer improved operating ranges and reduce noise and vibration resulting from cavitation. The research emphasizes the importance of stacking sequences in composite materials to achieve better performance compared to conventional propellers made from nickel-aluminum-bronze.

![International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology (IJMET), ISSN 0976 – 6340(Print),

ISSN 0976 – 6359(Online), Volume 5, Issue 9, September (2014), pp. 306-314 © IAEME

306

BEND-TWIST COUPLING AND ITS EFFECT ON CAVITATION INCEPTION

OF COMPOSITE MARINE PROPELLER

S. Solomon Raj1

, Dr. P.Ravinder Reddy2

1, 2

Department of Mechanical Engineering, Chaitanya Bharathi Institute of Technology,

Hyderabad-75, India

ABSTRACT

Cavitation in marine propellers has adverse effects such as noise, erosion and vibrations

which result in loss of lift and increase in drag. The radiated noise level of any form of cavitation is

of the order of magnitude higher than the noise level of non-cavitating flow. This is used by navy

ships to detect and locate other ships. Cavitation has to be discouraged from stealth point of view.

Generally marine propellers are made with NAB. The NAB propeller can be replaced with the

composite propeller which has intrinsic bend-twist coupling for performance enhancement. In this

work, the bend-twist coupling effects are used for designing the composite propeller, which replaces

the NAB propeller for increased operating range with regard to cavitation inception. Fluid structure

interaction (FSI) is carried out using the commercially available numerical codes FLUENT, ANSYS

and HYPERMESH. Experiments are carried out in cavitation tunnel to validate the numerical model.

The results showed that stacking sequence for the composite propeller can be selected to give

enhanced performance range when compared to metallic propeller from cavitation point of view.

Keywords: Bend-Twist Coupling, Cavitation Inception, Composite, Propeller.

I. INTRODUCTION

The propeller is that component of the ship which converts the engine power into the driving

force of the ship. These days, conventional marine propellers remain the standard propulsion

mechanism for surface ships and underwater vehicles. Composite materials have been fully

established as workable engineering materials and are now commonly used for many engineering

applications requiring high strength-to-weight and stiffness-to-weight ratios [1]. Traditional

propellers are made of high-stiffness metal materials such as nickel-aluminum-bronze (NAB) or

manganese bronze (MB). Rotors made of metallic alloys are typically designed to behave as rotating

rigid blades, and achieve the optimal performance at the design operating condition. When the

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING

AND TECHNOLOGY (IJMET)

ISSN 0976 – 6340 (Print)

ISSN 0976 – 6359 (Online)

Volume 5, Issue 9, September (2014), pp. 306-314

© IAEME: www.iaeme.com/IJMET.asp

Journal Impact Factor (2014): 7.5377 (Calculated by GISI)

www.jifactor.com

IJMET

© I A E M E](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bend-twist-coupling-and-its-effect-on-cavitation-inception-of-composite-marine-propeller-160218105350/75/BEND-TWIST-COUPLING-AND-ITS-EFFECT-ON-CAVITATION-INCEPTION-OF-COMPOSITE-MARINE-PROPELLER-1-2048.jpg)

![International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology (IJMET), ISSN 0976 – 6340(Print),

ISSN 0976 – 6359(Online), Volume 5, Issue 9, September (2014), pp. 306-314 © IAEME

307

operating condition changes from the design values, the blade geometry becomes sub-optimal

relative to the changed in flow. Consequently, the rotor efficiency decreases, and the rotor may be

subjected to strength, vibration and stability issues. The effect is more severe when a rotor is

operating in a spatially or temporally varying inflow. Fiber-reinforced composites are extensively

applied in various structures such as aerospace, renewable energy, and marine applications, because

of its light weight, high strength and corrosion resistance, better fatigue characteristics, lower life-

cycle costs.

Cavitation occurs when the local absolute pressure is less than local vapor pressure for the

fluid medium. In fluid power applications the evaporation pressure is reached when flow velocity is

increased sufficiently. Cavitation may lead to expensive problems if not acknowledged in an early

design stage. The inception of cavitation on hydrofoil is a basic phenomenon in hydrodynamics

which refers to the appearance of vapor phase when liquid flows around a hydrofoil. For thin

hydrofoils at moderate angle of attack, the first occurrence of cavitation is closely related to the

minimum pressure near the leading edge according to [2-6]. Under these conditions the inception of

cavitation marks the establishment of relatively large separated flow of vapor on the upper surface

near the leading edge commonly referred to as sheet cavitation. Once sheet cavitation is developed,

pressure on the upper surface of the hydrofoil is higher than the non cavitating flow. This in turn

limits the hydrofoils maximum lift, increases drag, changes the pitching moment. This may also

responsible for propeller’s noise and vibration as well as efficiency drop and material erosion. The

typical design objective of this work is to delay cavitation to higher angles of attack in order to widen

the performance of propeller’s blades. Cavitation inception is of direct importance to Navy vessels,

because of the sudden increase in noise levels causes trouble from stealth point of view at the onset

of cavitation.

This problem can be minimized by using blades made of anisotropic composites. Bend-twist

coupling effect is a unique characteristic of composite material. Structures can be stiffened or

deformed in a certain direction by arranging the orientation of the fibers [7]. Composite propellers

can aid in increasing cavitation inception speed. Most importantly, composite propellers can be

hydro-elastically tailored by exploiting the intrinsic deformation coupling behavior of anisotropic

composites to develop rapid, passive pitch adaptation, where the deformations are elastically tailored

to dynamically vary with the loading condition. With the increased use of fiber-reinforced

composites in structural components, studies involving the behavior of such structures and their

members are receiving considerable attention. This study is directed toward one such engineering

application, i.e., the composite propeller. The objective of this research is to study numerically the

behavior of a conventional propeller, made from composite material, under hydro-dynamic loading.

Emphasis is placed on understanding the effects of bend–twist coupling of composite laminates on

propeller performance. It is shown that the ply stacking sequence has an effect on the propeller

characteristics of a conventional propeller; by selecting a proper stacking sequence, a composite

propeller can be made to produce better performance than its metallic counterpart [8].

II. OPEN WATER CHARACTERISTICS

The open-water characteristics of the propeller are generally presented using the following

coefficients:

ܽ݀݁ܿ݊ܽݒ ܿݐ݂݂݊݁݅ܿ݅݁ ൌ ܬ ൌ

ܸ

݊ܦ

݁ݑݍݎݐ ܿݐ݂݂݊݁݅ܿ݁ ൌ ܭொ ൌ

ܳ

ߩ݊ଶܦହ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bend-twist-coupling-and-its-effect-on-cavitation-inception-of-composite-marine-propeller-160218105350/75/BEND-TWIST-COUPLING-AND-ITS-EFFECT-ON-CAVITATION-INCEPTION-OF-COMPOSITE-MARINE-PROPELLER-2-2048.jpg)

![International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology (IJMET), ISSN 0976 – 6340(Print),

ISSN 0976 – 6359(Online), Volume 5, Issue 9, September (2014), pp. 306-314 © IAEME

308

ݐݏݑݎ݄ݐ ܿݐ݂݂݊݁݅ܿ݅݁ ൌ ܭ் ൌ

ܶ

ߩ݊ଶܦସ

݂݂݁݅ܿ݅݁݊ܿݕ ൌ ߟ ൌ

ܸܶ

2ߨ݊ܳ

ൌ

ܭ் כ ܬ

2ߨܭொ

݁ݎ݄݁ݓ ܦ ൌ ݀ܽ݅݉݁ݎ݁ݐ ݂ ݄݁ݐ ;ݎ݈݈݁݁ݎ

ܸ ൌ ݈ܽܽ݅ݔ ;ݕݐ݈݅ܿ݁ݒ

݊ ൌ ݈ܽ݊݅ݐܽݐݎ ݕݐ݈݅ܿ݁ݒሺݏݎሻ;

ߩ ൌ ݂݈݀݅ݑ ݀݁݊;ݕݐ݅ݏ

ܶ ൌ ݐݏݑݎ݄ݐ

ܳ ൌ .݁ݑݍݎݐ (1)

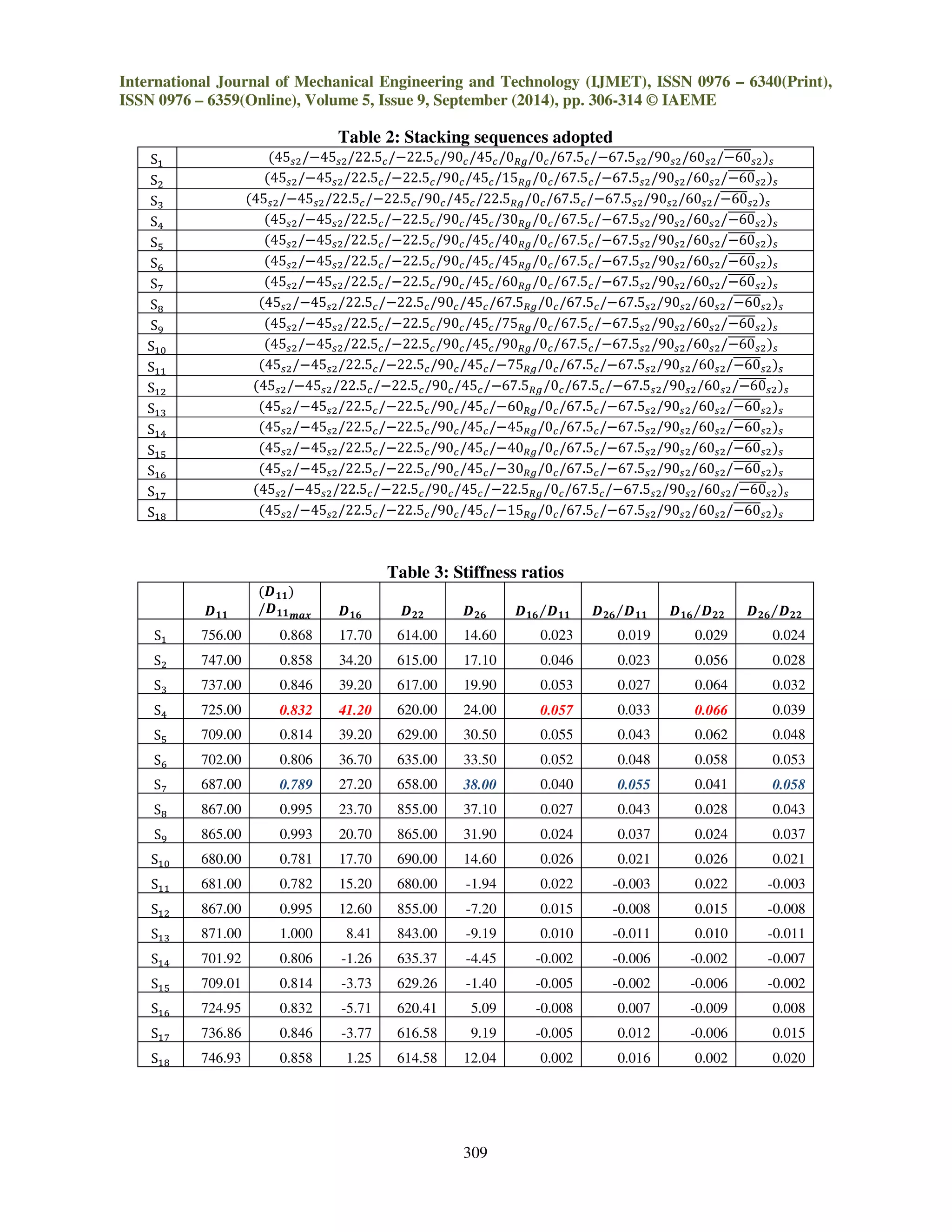

III. BEND-TWIST EFFECT ON PERFORMANCE OF COMPOSITE PROPELLER

Composites do possess variety of coupling effects such as extension-shear:ܣଵ, ܣଶ,

extension-bending:ܤଵଵ, ܤଵଶ, ܤଶଶ, extension –twisting:ܤଵ, ܤଶ, shear- bending:ܤଵ,ܤଶ, shear-

twisting:ܤ, bending- twisting: ܦଵ, ܦଶ, biaxial-extension:ܣଵଶ, and biaxial- bending:ܦଵଶ[11,12,13].

For the design of composite marine propellers researchers used exclusively the bend-twist coupling

phenomenon for performance enhancement compared to metallic propeller [9]. In this work, the

bend-twist coupling is investigated for a three material composite laminate made up of R-glass

roving UD/epoxy, S2 glass fabric/epoxy and carbon UD/epoxy, the properties of which are shown in

table 1. All the stacking sequences are assumed to be symmetric. As a result of selecting symmetric

laminates, extension-twist coupling is not investigated, i.e. ܤଵ and ܤଶ ൌ 0. For the purpose of

understanding the effect of bend-twist coupling on the performance of composite marine propeller,

the ply angle of the layer made of R-glass roving UD/epoxy is changed systematically in stacking

sequences ܵଵݐ ܵଵ଼ from 90

ݐ െ 90

as shown in table 2. For better understanding the propeller

characteristics, the stiffness ratios of ܦଵ/ܦଵଵ, ܦଶ/ܦଵଵ, ܦଵ/ܦଶଶ, ܽ݊݀ ܦଶ/ܦଶଶ versus ߠ for the

laminateሺ45௦ଶ/െ45௦ଶ/22.5/െ22.5/90/45/ߠோ/0/67.5/െ67.5௦ଶ/90௦ଶ/60௦ଶ/ െ60തതതതതത௦ଶሻ௦ are

tabulated for each of the sequences as shown in table 3 and are plotted in fig 1.

Table 1: Material properties

R Glass roving UD / Epoxy S2 Glass fabric /

Epoxy

Carbon UD / Epoxy

thickness 0.3 mm 0.32mm 0.3mm

Density (gm/cc) 2 1.8 1.6

۳( Gpa) 48.3 22.92 25

۳ 12.4 22.92 10

۳ 12.4 12.4 10

ૅ 0.16 0.12 0.16

ૅ 0.28 0.2 0.2

ૅ 0.28 0.2 0.16

۵(Gpa) 6.6 4.7 5.2

۵ 4.14 4.2 3.8

۵ 4.14 4.2 6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bend-twist-coupling-and-its-effect-on-cavitation-inception-of-composite-marine-propeller-160218105350/75/BEND-TWIST-COUPLING-AND-ITS-EFFECT-ON-CAVITATION-INCEPTION-OF-COMPOSITE-MARINE-PROPELLER-3-2048.jpg)

![International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology (IJMET), ISSN 0976 – 6340(Print),

ISSN 0976 – 6359(Online), Volume 5, Issue 9, September (2014), pp. 306-314 © IAEME

310

As ߠ is varied from 0

in either the positive or negative direction, ܦଵ/ܦଵଵ changes at higher

rate compared to ܦଶ/ܦଵଵ, and is maximum at plus or minus 30

. The ratio ܦଶ/ܦଵଵ changes at a

lower rate, peaking at േ60

. As expected ܦଶଶ/ܦଵଵ is minimum for 0

andേ90

. As reported in [8],

higher values of these ratios lead to the more twisting effect about the ࢞ and ࢟ axis thereby

producing more coupling effect. The propeller with the high values of ܦଵ ܦଵଵ⁄ , ܦଵ ܦଶଶ⁄ and

ܦଶ ܦଵଵ⁄ and ܦଶ ܦଶଶ⁄ , can attain the higher values of blade setting angles . Accordingly, stacking

sequences ܵସ and ܵ are chosen, which has got higher values ofܦଵ ܦଵଵ⁄ ,ܦଵ ܦଶଶ⁄ , ܦଶ ܦଵଵ⁄ and

ܦଶ ܦଶଶ⁄ , for the composite propeller. ܦଵଵ/ܦଵଵ௫

, will provide a measure of the relative bending

stiffness of the propellers. As it is maximum for sequence ܵସ , compared to sequenceܵ, sequence ܵସ

is selected for the composite propeller. The material data and layup sequence is incorporated in

hyper-mesh 9.0, having a total of 25 layers.

Fig 1: Stiffnesses of different stacking sequences

IV. FLUID-STRUCTURE INTERACTION (FSI)

The hydro-elastic model basically accounts for the fluid structure interaction (FSI), as

presented in [10]. The displacement field, {,}ݑ is determined using the finite element method in

structural model realized with ANSYS, and the hydrodynamic pressure field, {,} is determined

using the finite volume method in the hydrodynamic model realized through FLUENT. The

equilibrium between the hydrodynamic and structural forces is obtained by the hydro-elastic model.

That is, the hydro-elastic model determines the displacement vector {}ݑ which satisfies the

ሾܭሿሼݑሽ ൌ ሼሽ (2)

Where, [K] is the structural stiffness matrix which can be tailored by laminate lay-up

sequence. The displacement field is determined by the structural model for the given pressure

-90 -70 -50 -30 -10 10 30 50 70 90

-0.02

-0.01

0

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.05

0.06

0.07

0.8

0.85

0.9

0.95

1

D16/D11,D26/D11,D16,D22andD26/D22

D22/D11

θ in Degrees

Stiffnesses of different stacking sequences

(D22/D11) D16/D11 D26/D11 D16/D22 D26/D22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bend-twist-coupling-and-its-effect-on-cavitation-inception-of-composite-marine-propeller-160218105350/75/BEND-TWIST-COUPLING-AND-ITS-EFFECT-ON-CAVITATION-INCEPTION-OF-COMPOSITE-MARINE-PROPELLER-5-2048.jpg)

![International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology (IJMET), ISSN 0976 – 6340(Print),

ISSN 0976 – 6359(Online), Volume 5, Issue 9, September (2014), pp. 306-314 © IAEME

313

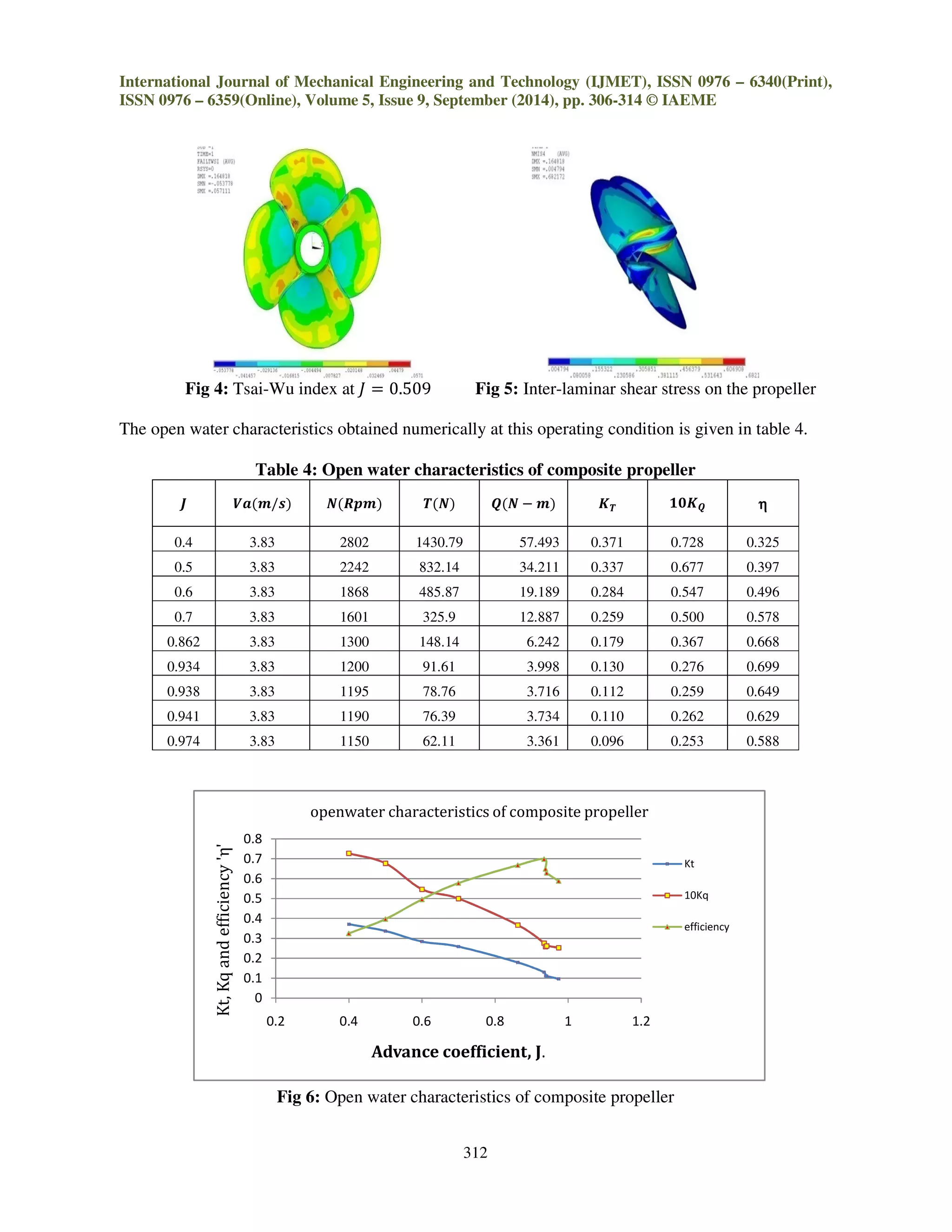

VI. CONCLUSIONS

Following conclusions are drawn from the above work.

1. The numerical method adopted in the research work successfully predicted the open water

characteristics of a marine propeller, validated through experiments.

2. Fluid structure interactions are accounted using the hydro-elastic model used for composite

propellers.

3. Bend-twist coupling in composites is explored systematically for the better performance of a

composite propeller compared to metallic propeller.

4. The effect of bend-twist coupling on the cavitation performance of a marine propeller is

studied systematically by varying the fiber orientation of the R glass roving/epoxy lamina.

5. The operating range of the metallic propeller over which, it can perform without cavitation

from design condition is between the advance coefficients 0.943-0.54. The maximum open

water efficiency in the given range is 71%.

6. The operating range for the composite propeller over which, it can perform without cavitation

is between the advance coefficients 0.934-0.45. The maximum open water efficiency in the

given range is 69.9%.

7. Without sacrificing the efficiency of a propeller, the range of advance coefficients over which

the composite propeller do not cavitate is increased by 22% compared to metallic propeller.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Authors would like to thank the NSTL, Vizag for permitting to conduct the cavitation

tunnel tests.

REFERENCES

Journal Papers

[1] Ya-Jung Lee, Ching-Chieh Lin, Optimized design of composite propeller, Mechanics of

advanced materials and structures, 11:17-30,2004.

[2] Arakeri V.H and Accosta AJ, 1973 “Viscous effects in the inception of cavitation on

axisymmetric bodies”.

[3] Arakeri, V. H., 1975, “Viscous Effects on the Position of Cavitation Separation from

Smooth Bodies,” J. Fluid Mech., 68, pp. 779–799.

[4] Arakeri, V. H., Carroll, J. A., and Holl, J. W., 1981, “A Note on the Effect of Short and Long

Laminar Separation Bubbles on Desinent Cavitation,” ASME J. Fluids Eng., 1031,

pp. 28–32.

[5] Van der Meulen, J. H. J., 1978, “A Holographic Study of the Influence of Boundary Layer

and Surface Characteristics on Inception and Developed Cavitation on Axisymmetric

Bodies,” Proceedings of 12th Symposium on Na- val Hydrodynamics, Washington, DC,

pp. 443–451.

[6] Van der Meulen, J. H. J., 1980, “Boundary Layer and Cavitation Studies of NACA 16–012

and NACA 4412 Hydrofoils,” Proceedings of 13th Symposium on Naval Hydrodynamics,

Tokyo, Japan, pp. 195–219.

[7] Ching-Chieh Lin, Ya-Jung Lee, Chu-Sung Hung, Optimization and experiment of composite

marine propellers, Composite structures, 2008.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bend-twist-coupling-and-its-effect-on-cavitation-inception-of-composite-marine-propeller-160218105350/75/BEND-TWIST-COUPLING-AND-ITS-EFFECT-ON-CAVITATION-INCEPTION-OF-COMPOSITE-MARINE-PROPELLER-8-2048.jpg)

![International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology (IJMET), ISSN 0976 – 6340(Print),

ISSN 0976 – 6359(Online), Volume 5, Issue 9, September (2014), pp. 306-314 © IAEME

314

[8] Abdul M.Khan, Daniel O.Adams, Effects of bend-twist coupling on composite propeller

performance, Mechanics of Composite materials and structures, 7: 383-401, 2000.

[9] S.Solomon Raj, and P.Ravinder reddy., “ Performance evaluation of composite marine

propeller using L8 orthogonal array,” International Journal of engineering science and

technology, Vol.3,No.11, November 2011.

[10] José Pedro Blasques,

, Christian Berggreen, Poul Andersen, Hydro-elastic analysis and

optimization of a composite marine propeller, Marine Structures Volume 23, Issue 1,

January 2010, Pages 22–38.

Books

[11] R.M.Jones, Mechanics of composites materials, second edition, Taylor&Francis.

[12] Ever J.Barbero, Introduction to composite material design, Taylor& Francis.

[13] Ronald F.Gibson, Principles of composite material mechanics, second edition, CRC press.

[14] Ever J.Barbero, Finite element analysis of composite materials, Taylor& Francis.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bend-twist-coupling-and-its-effect-on-cavitation-inception-of-composite-marine-propeller-160218105350/75/BEND-TWIST-COUPLING-AND-ITS-EFFECT-ON-CAVITATION-INCEPTION-OF-COMPOSITE-MARINE-PROPELLER-9-2048.jpg)