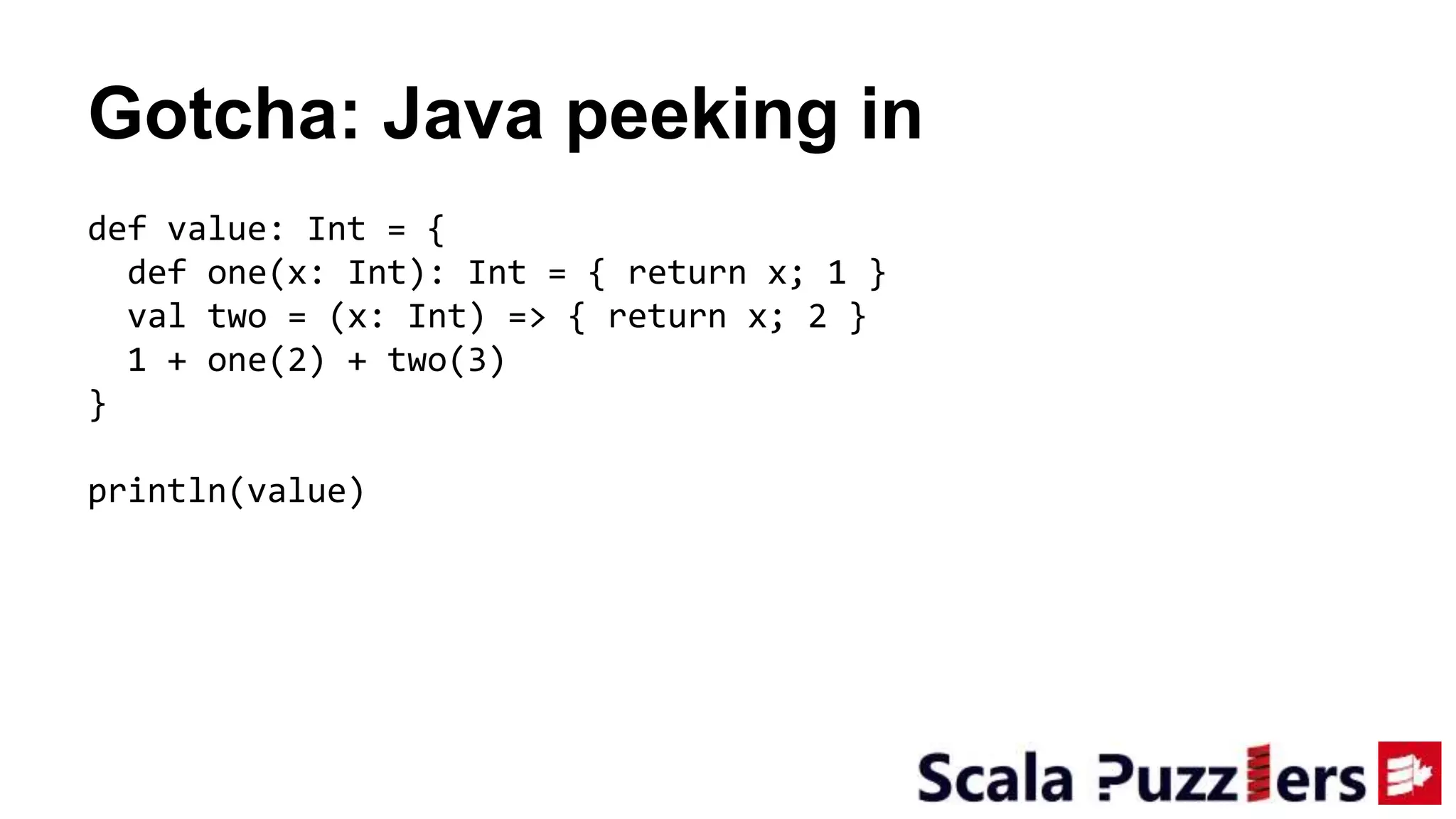

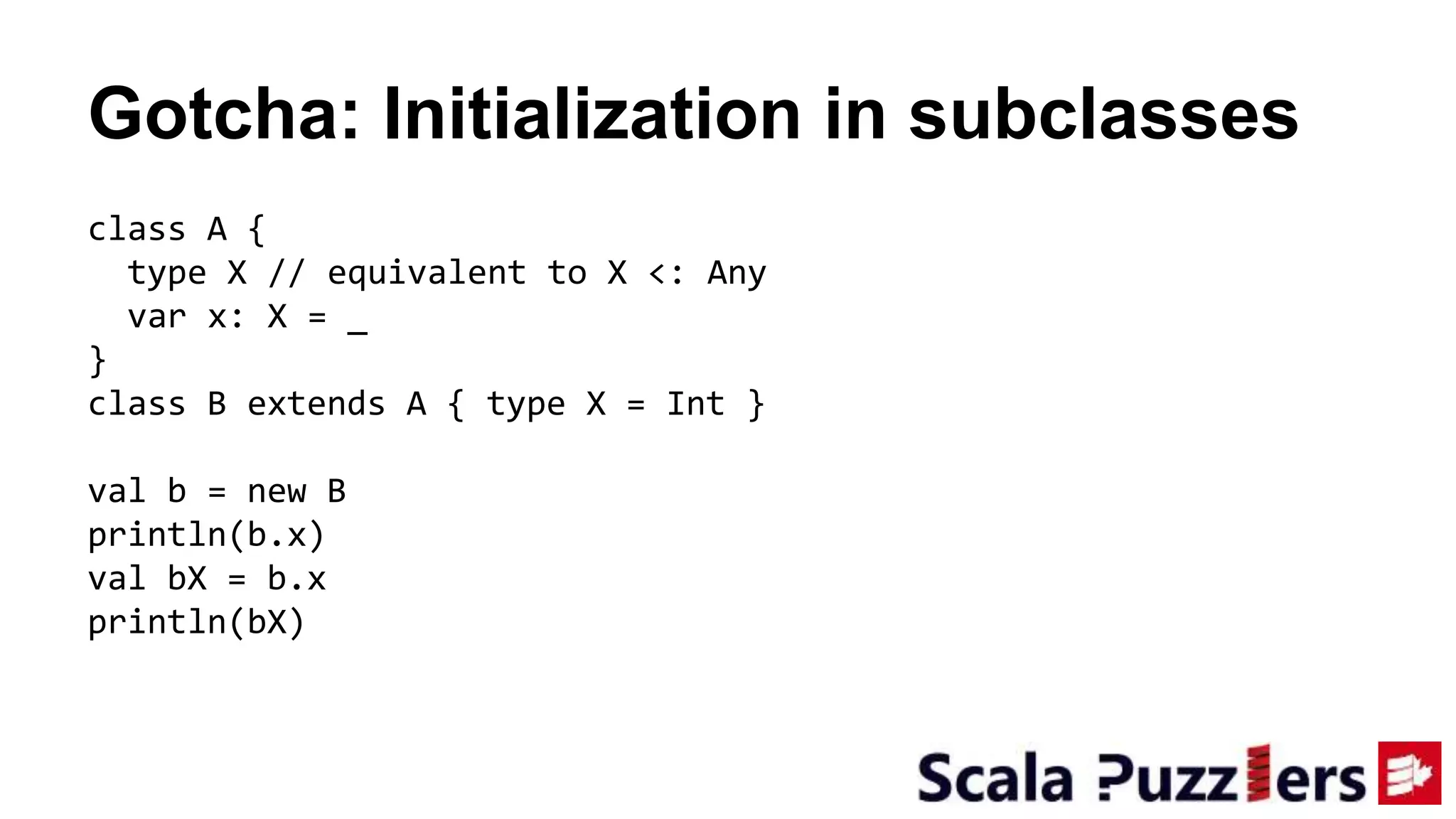

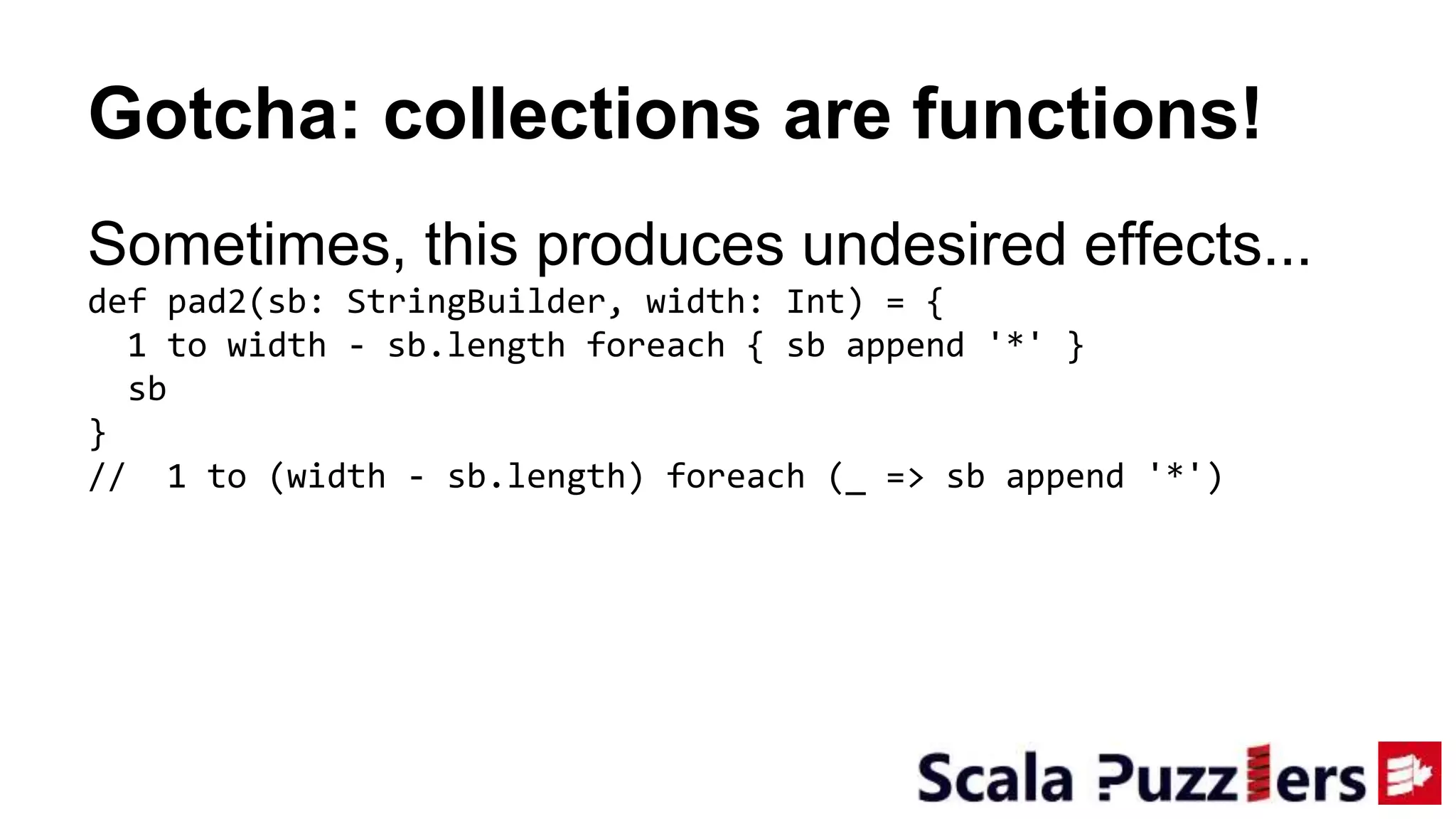

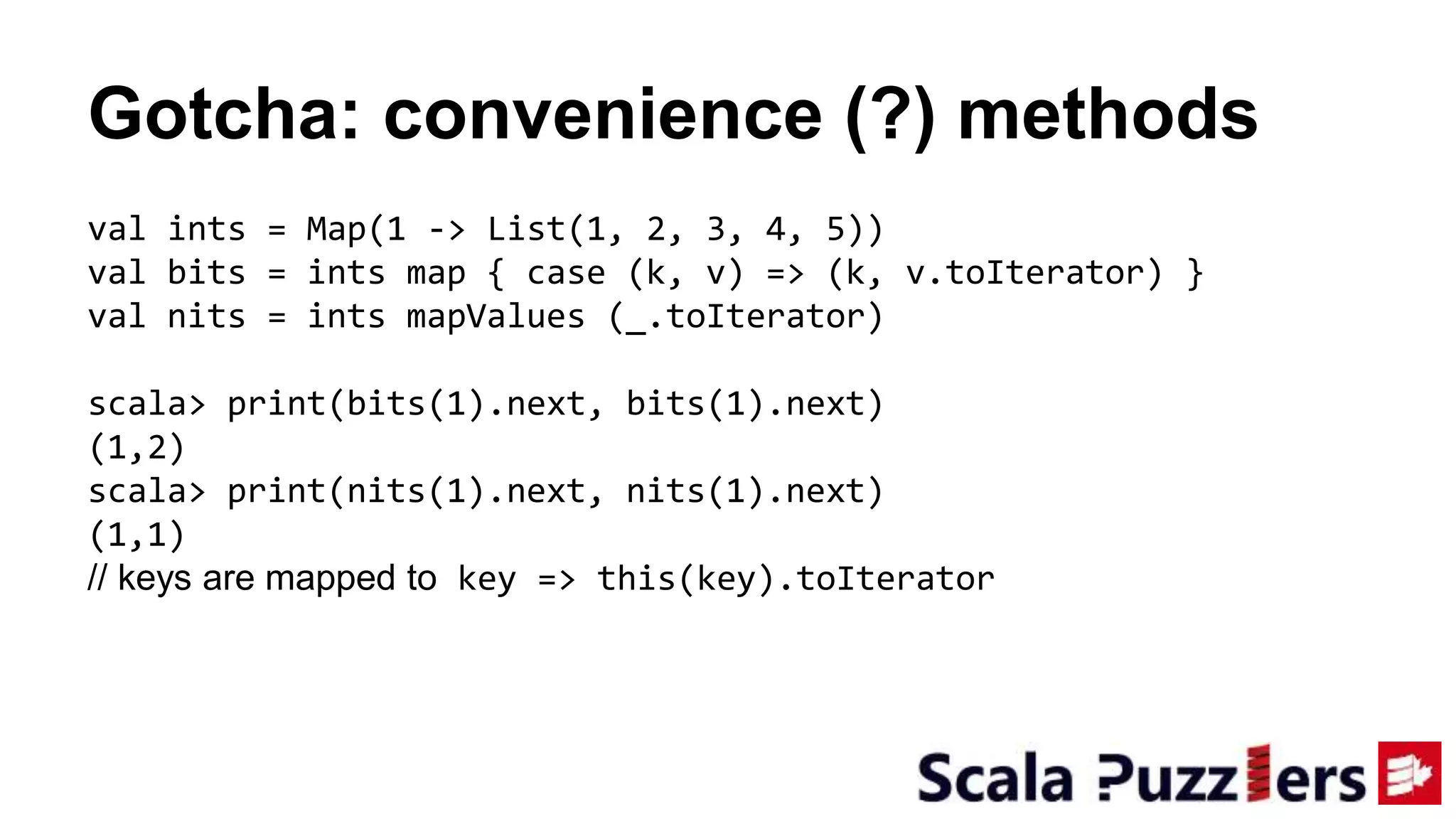

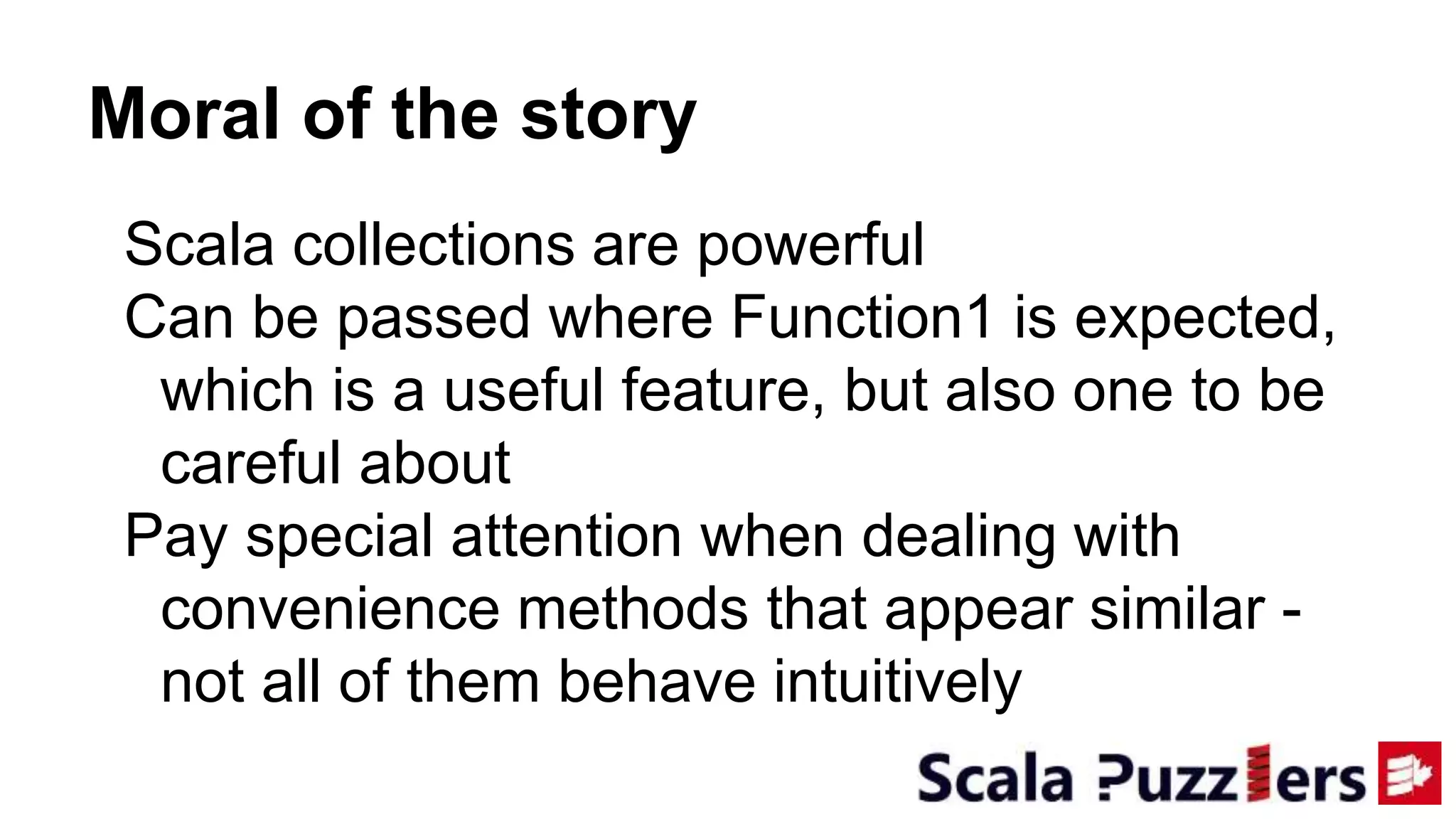

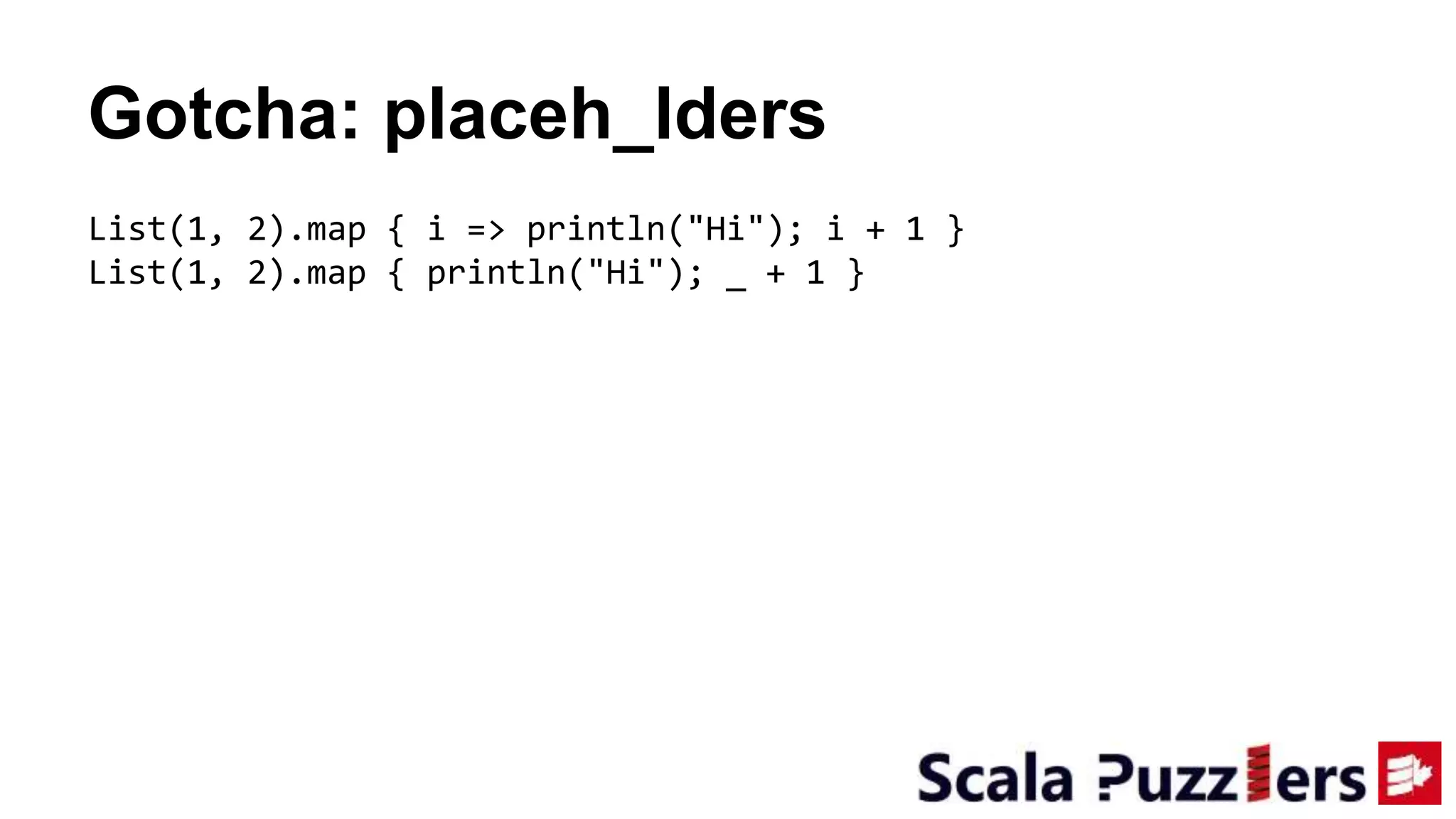

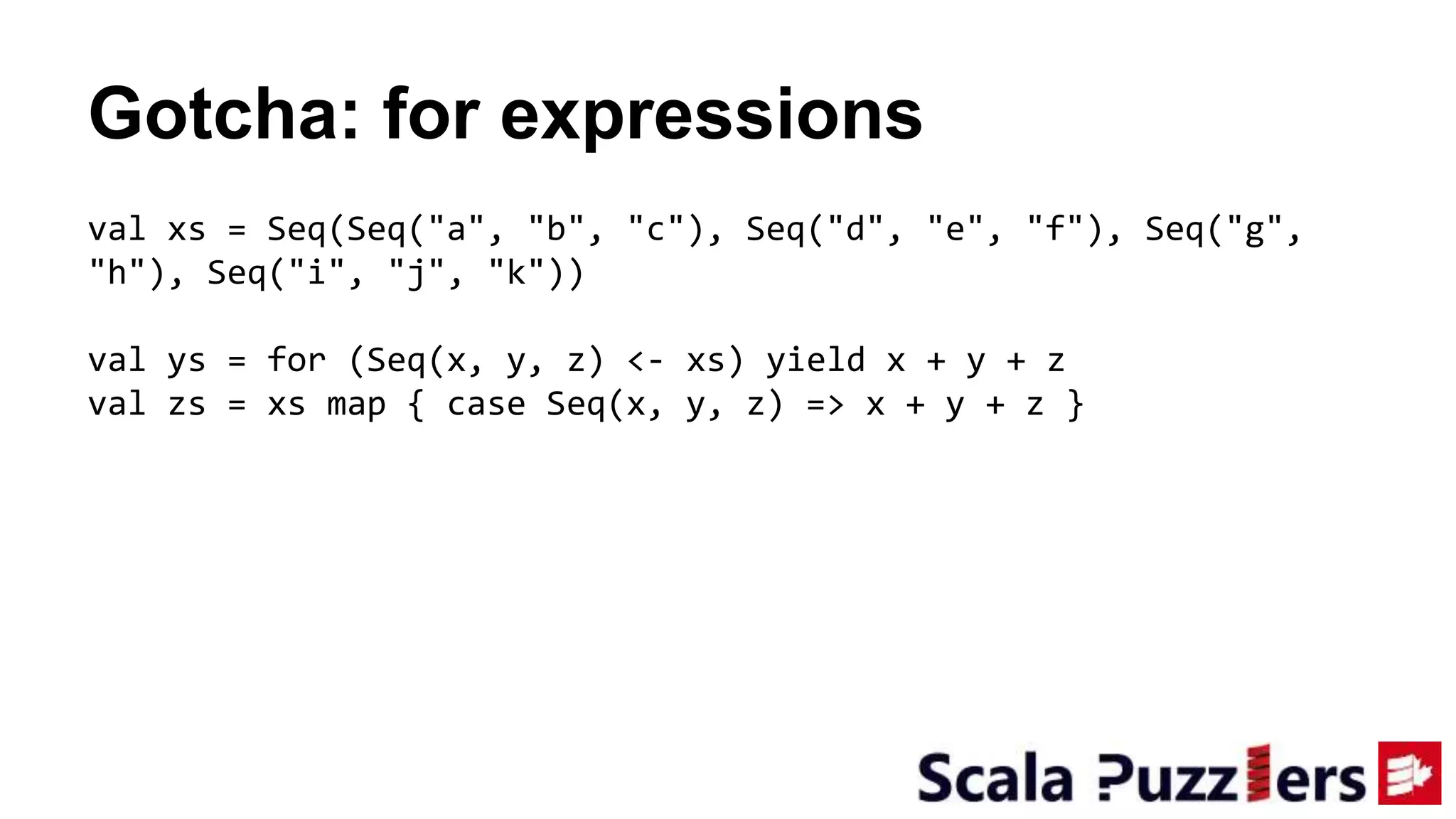

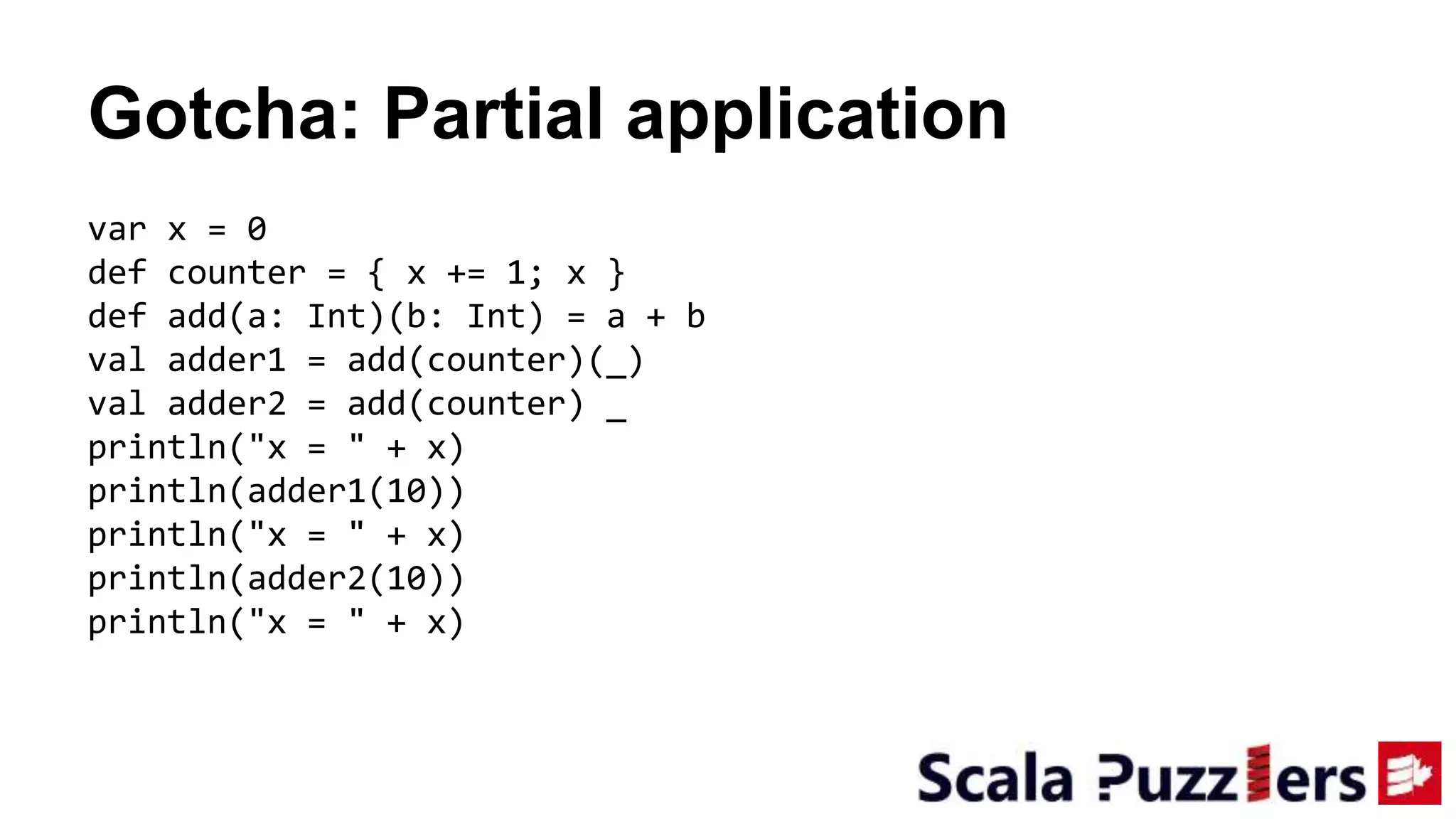

The document discusses the complexities and surprising behaviors in Scala programming, categorized into five clusters: object-orientation, collections, syntax sugar, the type system, and functional programming. It emphasizes the need to be cautious of pitfalls when leveraging Scala's features and the importance of using idiomatic practices to avoid confusion. The authors conclude that while Scala offers powerful functionalities, it requires careful consideration and understanding of its intricacies to prevent coding issues.

![Gotcha: Constructors

object HipNTrendyMarket extends App { // now extends App!

implicit val normalMarkup = new Markup

Console println makeLabel(3)

implicit val touristMarkup = new TouristMarkup

Console println makeLabel(5)

}

object OldSkoolMarket {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

implicit val normalMarkup = new Markup

Console println makeLabel(3)

implicit val touristMarkup = new TouristMarkup

Console println makeLabel(5)

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scalaupnorth-150930020449-lva1-app6891/75/Scala-Up-North-Analysing-Scala-Puzzlers-Essential-and-Accidental-Complexity-in-Scala-11-2048.jpg)

![Gotcha: convenience (?) methods

import collection.mutable.Queue

val goodies: Map[String, Queue[String]] = Map().withDefault(_ =>

Queue("No superheros here. Keep looking."))

val baddies: Map[String, Queue[String]] =

Map().withDefaultValue(Queue("No monsters here. Lucky you."))

println(goodies("kitchen").dequeue)

println(baddies("in attic").dequeue)

println(goodies("dining room").dequeue)

println(baddies("under bed").dequeue)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scalaupnorth-150930020449-lva1-app6891/75/Scala-Up-North-Analysing-Scala-Puzzlers-Essential-and-Accidental-Complexity-in-Scala-20-2048.jpg)

![Gotcha: implicit magic

case class Card(number: Int, suit: String = "clubs") {

val value = (number % 13) + 1 // ace = 1, king = 13

def isInDeck(implicit deck: List[Card]) = deck contains this

}

implicit val deck = List(Card(1, "clubs"))

implicit def intToCard(n: Int) = Card(n)

println(1.isInDeck)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scalaupnorth-150930020449-lva1-app6891/75/Scala-Up-North-Analysing-Scala-Puzzlers-Essential-and-Accidental-Complexity-in-Scala-26-2048.jpg)

![Gotcha: Type widening

val zippedLists = (List(1,3,5), List(2,4,6)).zipped

val result = zippedLists.find(_._1 > 10).getOrElse(10)

result: Any = 10

def List.find(p: (A) ⇒ Boolean): Option[A]

def Option.getOrElse[B >: A](default: ⇒ B): B

Type B is inferred to be Any - the least common

supertype between Tuple2 and Int](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scalaupnorth-150930020449-lva1-app6891/75/Scala-Up-North-Analysing-Scala-Puzzlers-Essential-and-Accidental-Complexity-in-Scala-30-2048.jpg)

![Gotcha: Type widening

For explicitly defined type hierarchies, this works as

intended:

scala> trait Animal

scala> class Dog extends Animal

scala> class Cat extends Animal

scala> val dog = Option(new Dog())

scala> val cat = Option(new Cat())

scala> dog.orElse(cat)

res0: Option[Animal] = Some(Dog@7d8995e)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scalaupnorth-150930020449-lva1-app6891/75/Scala-Up-North-Analysing-Scala-Puzzlers-Essential-and-Accidental-Complexity-in-Scala-31-2048.jpg)

![Gotcha: Type adaption galore

val numbers = List("1", "2").toSet() + "3"

println(numbers)

false3

def List.toSet[B >: A]: Set[B]

List("1", "2").toSet.apply() // apply() == contains()

Compiler implicitly inserts Unit value () and infers

supertype Any:

List("1", "2").toSet[Any].apply(())](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scalaupnorth-150930020449-lva1-app6891/75/Scala-Up-North-Analysing-Scala-Puzzlers-Essential-and-Accidental-Complexity-in-Scala-33-2048.jpg)

![Gotcha: Native function syntax

val isEven = PartialFunction[Int, String] {

case n if n % 2 == 0 => "Even"

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/scalaupnorth-150930020449-lva1-app6891/75/Scala-Up-North-Analysing-Scala-Puzzlers-Essential-and-Accidental-Complexity-in-Scala-40-2048.jpg)