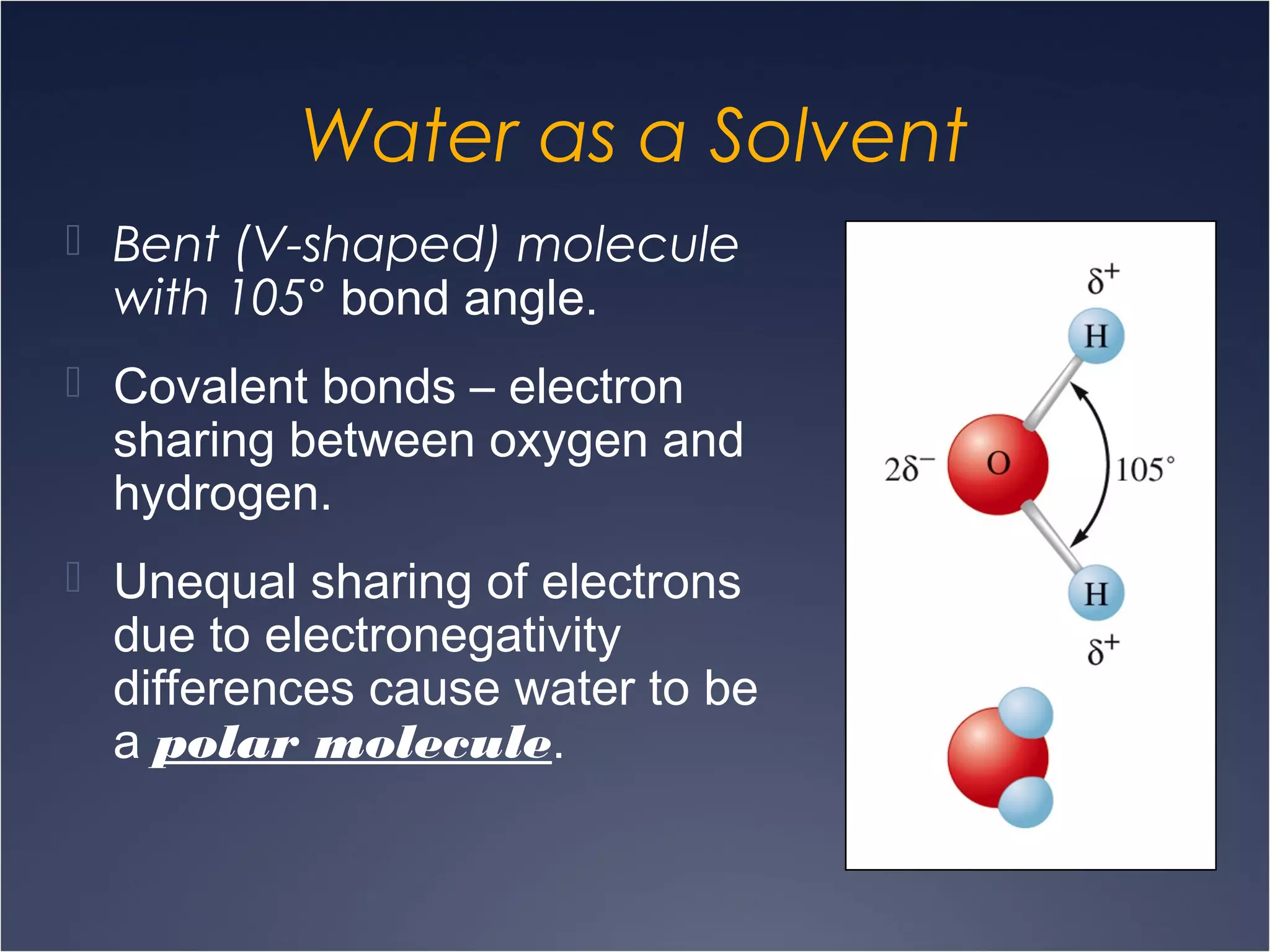

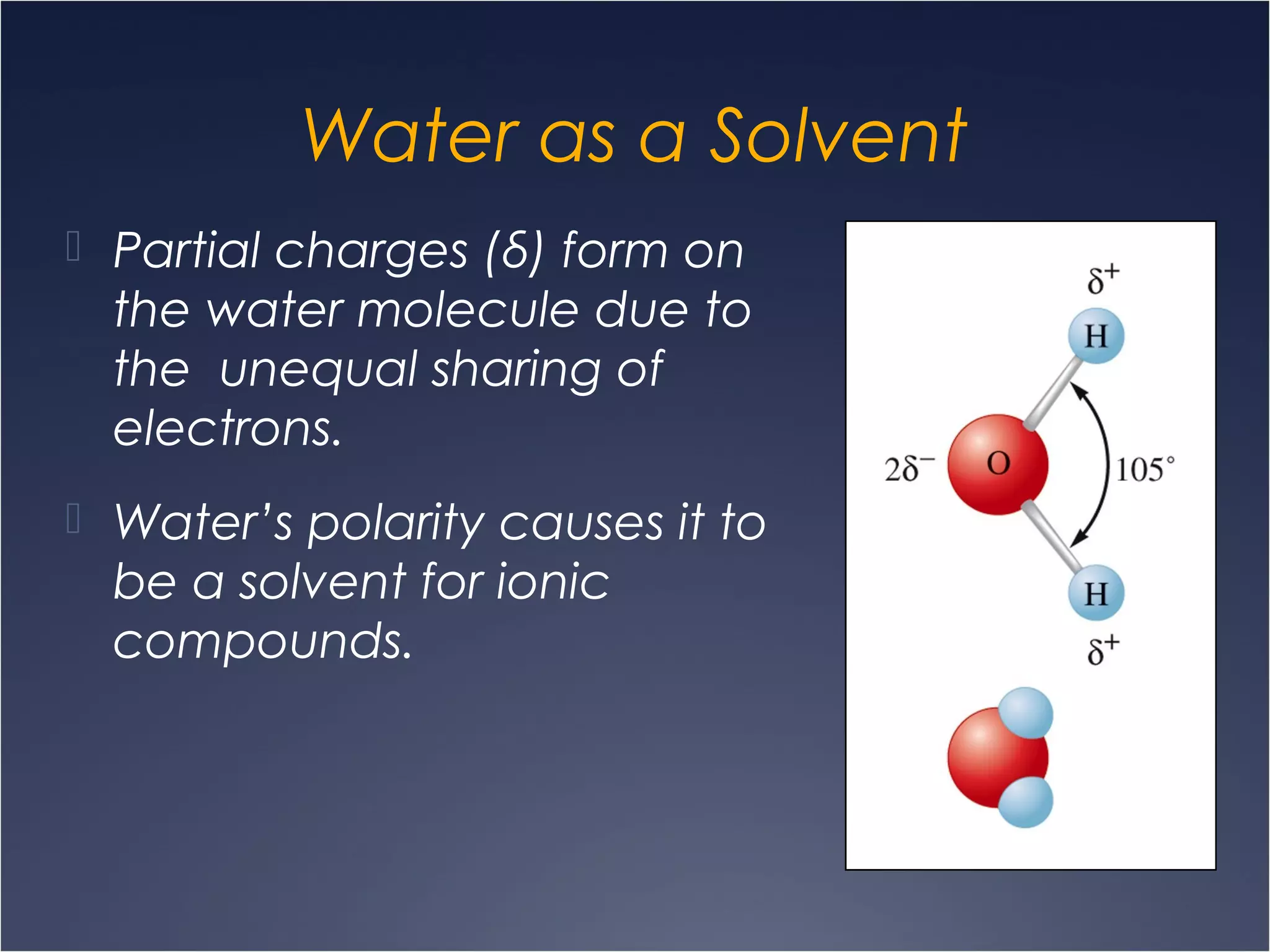

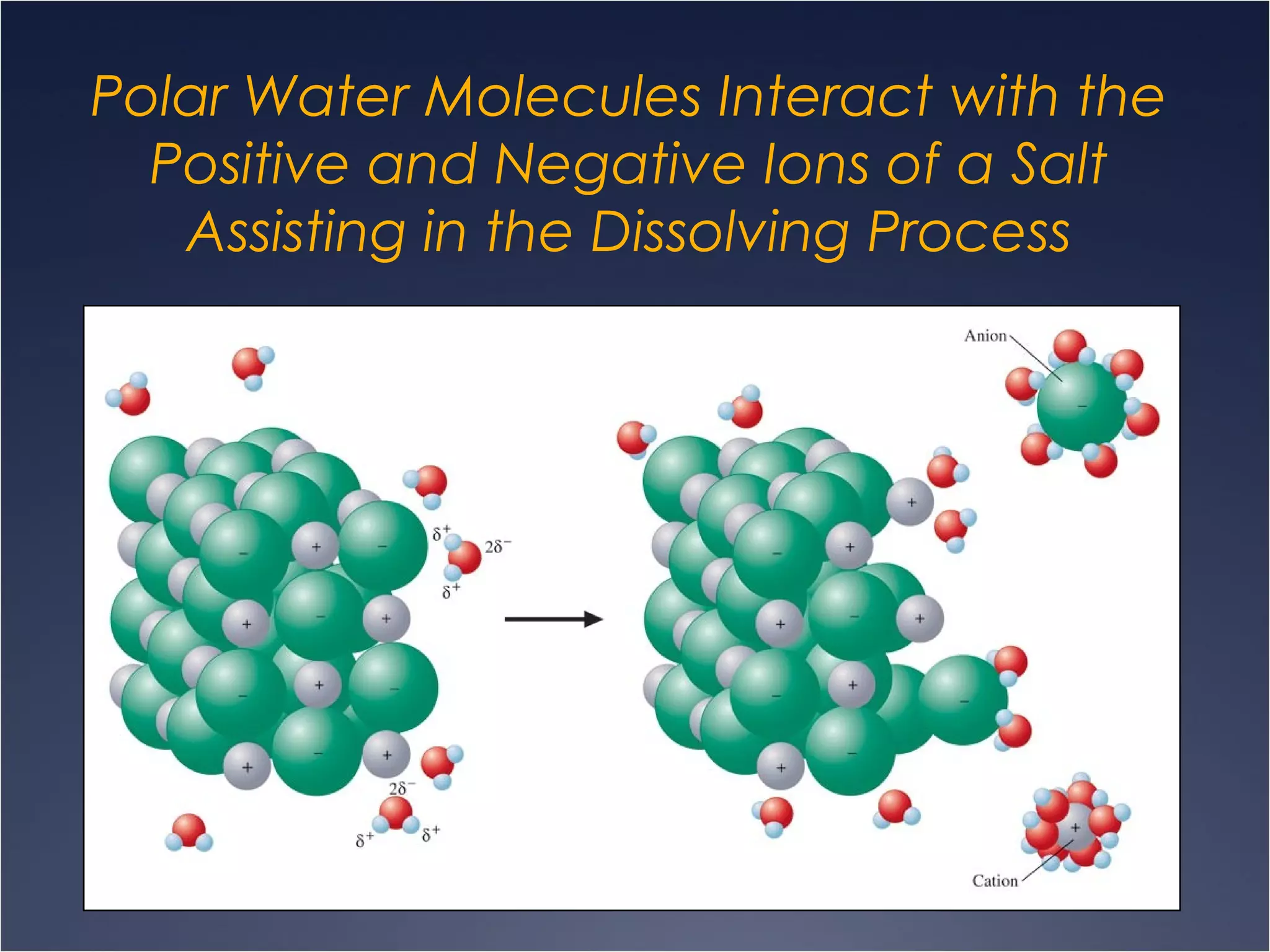

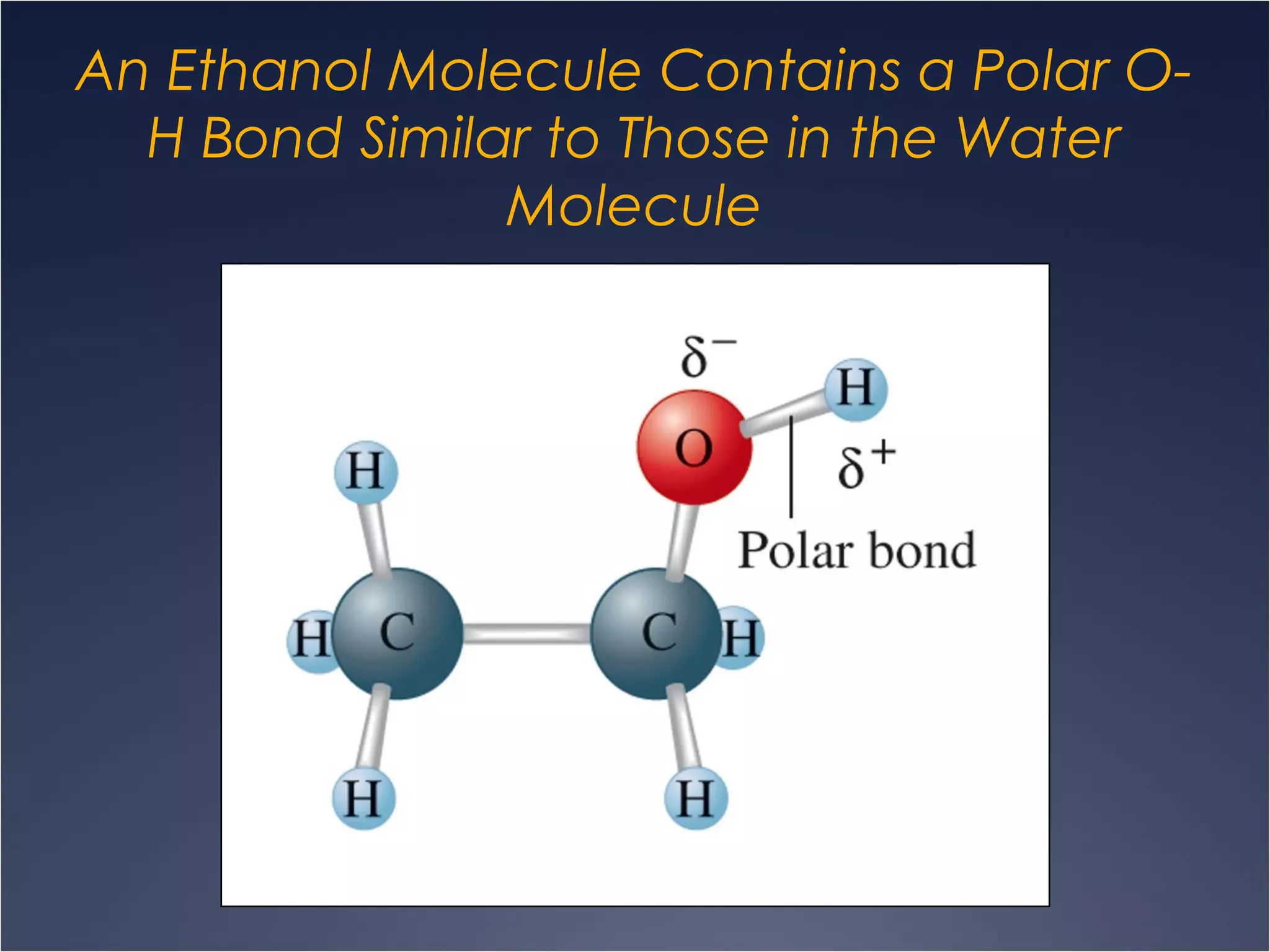

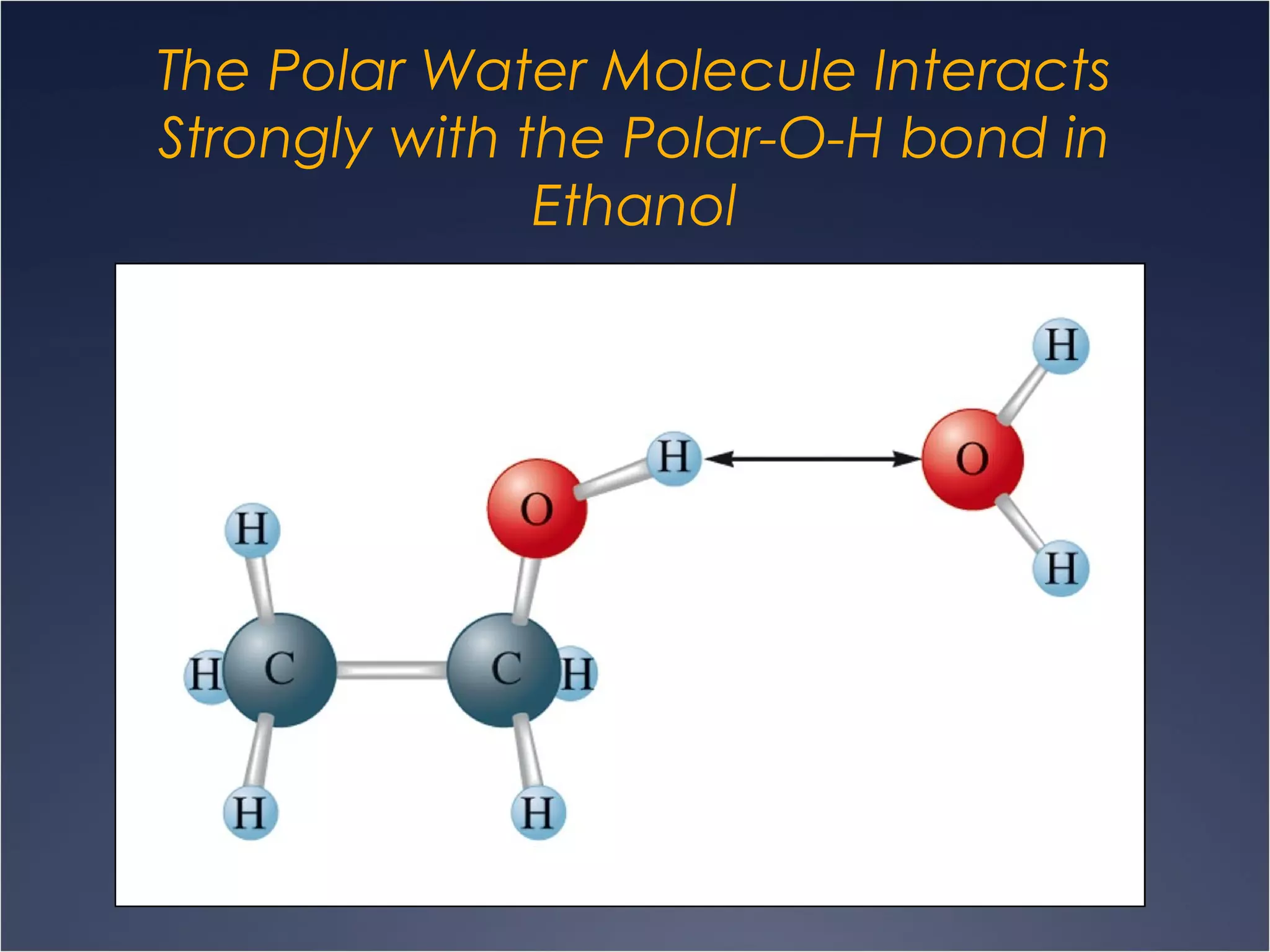

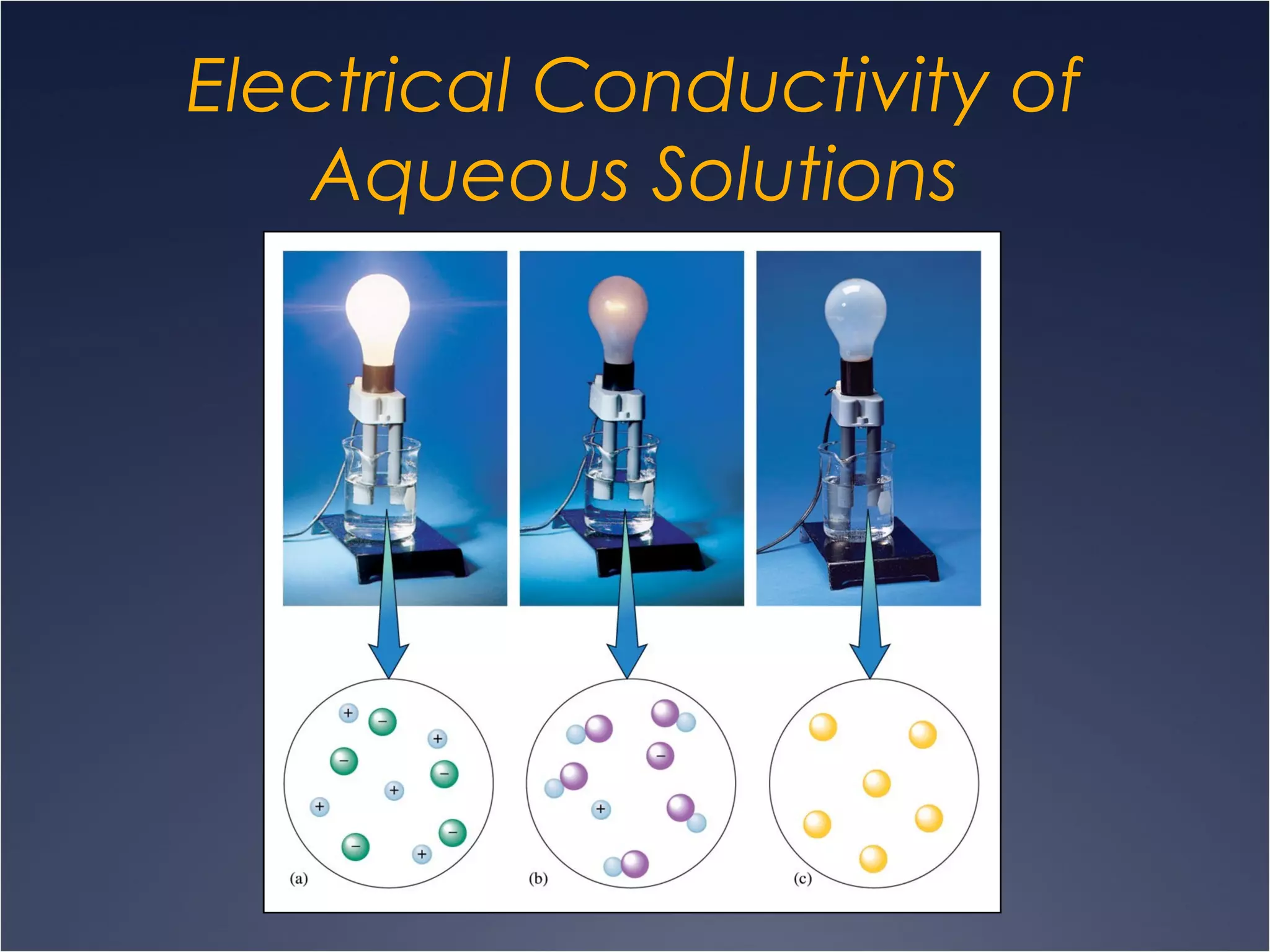

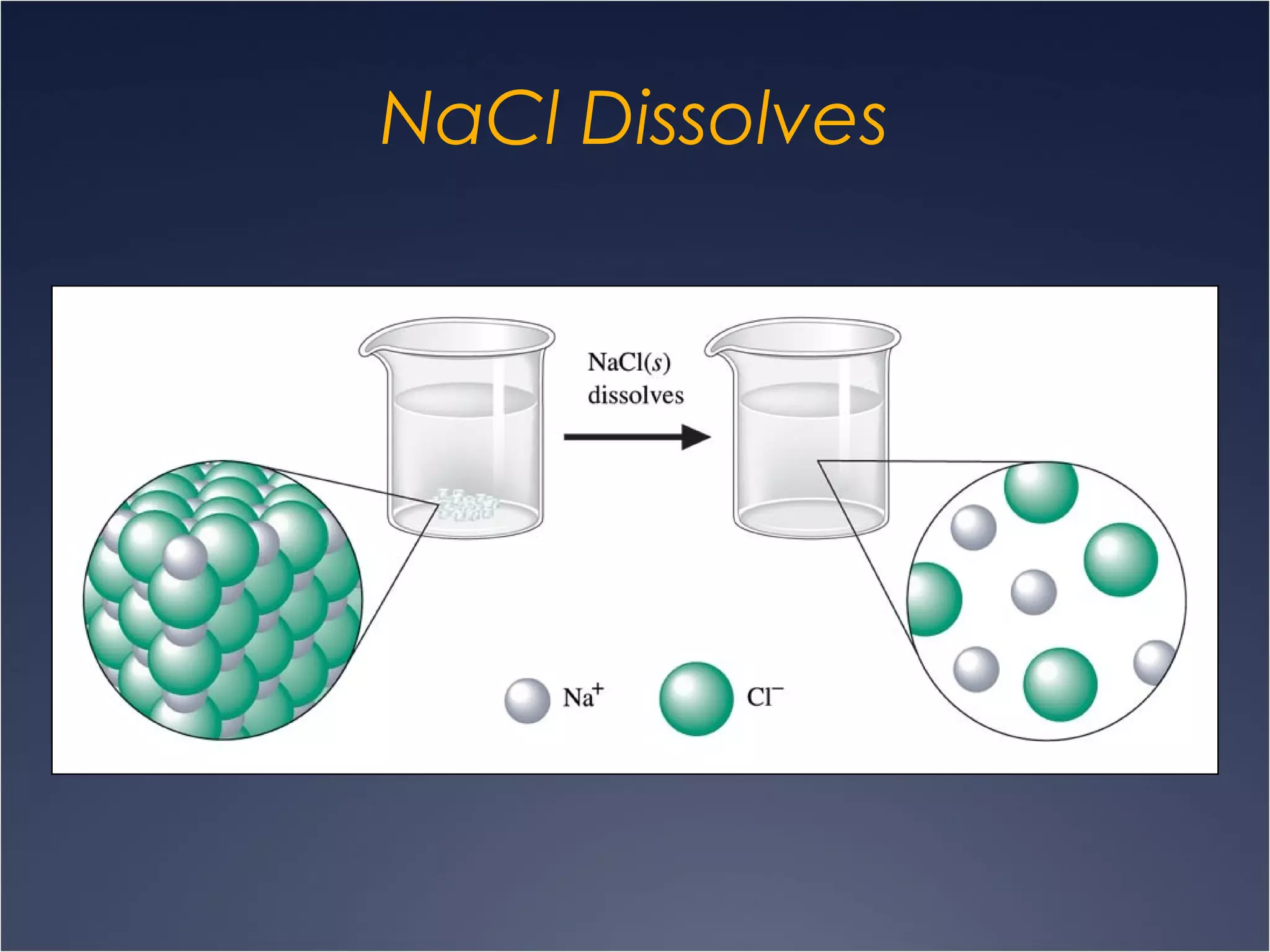

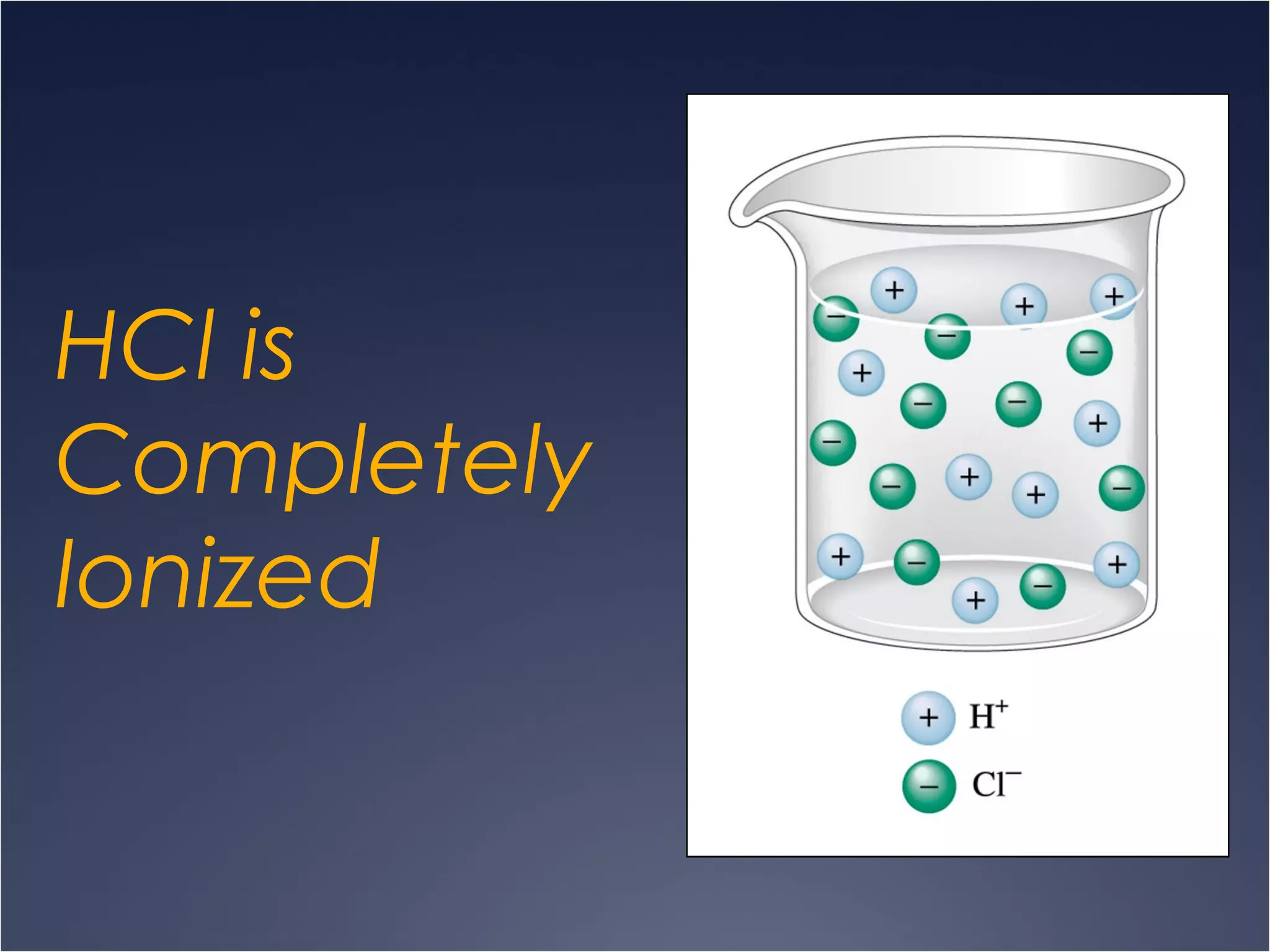

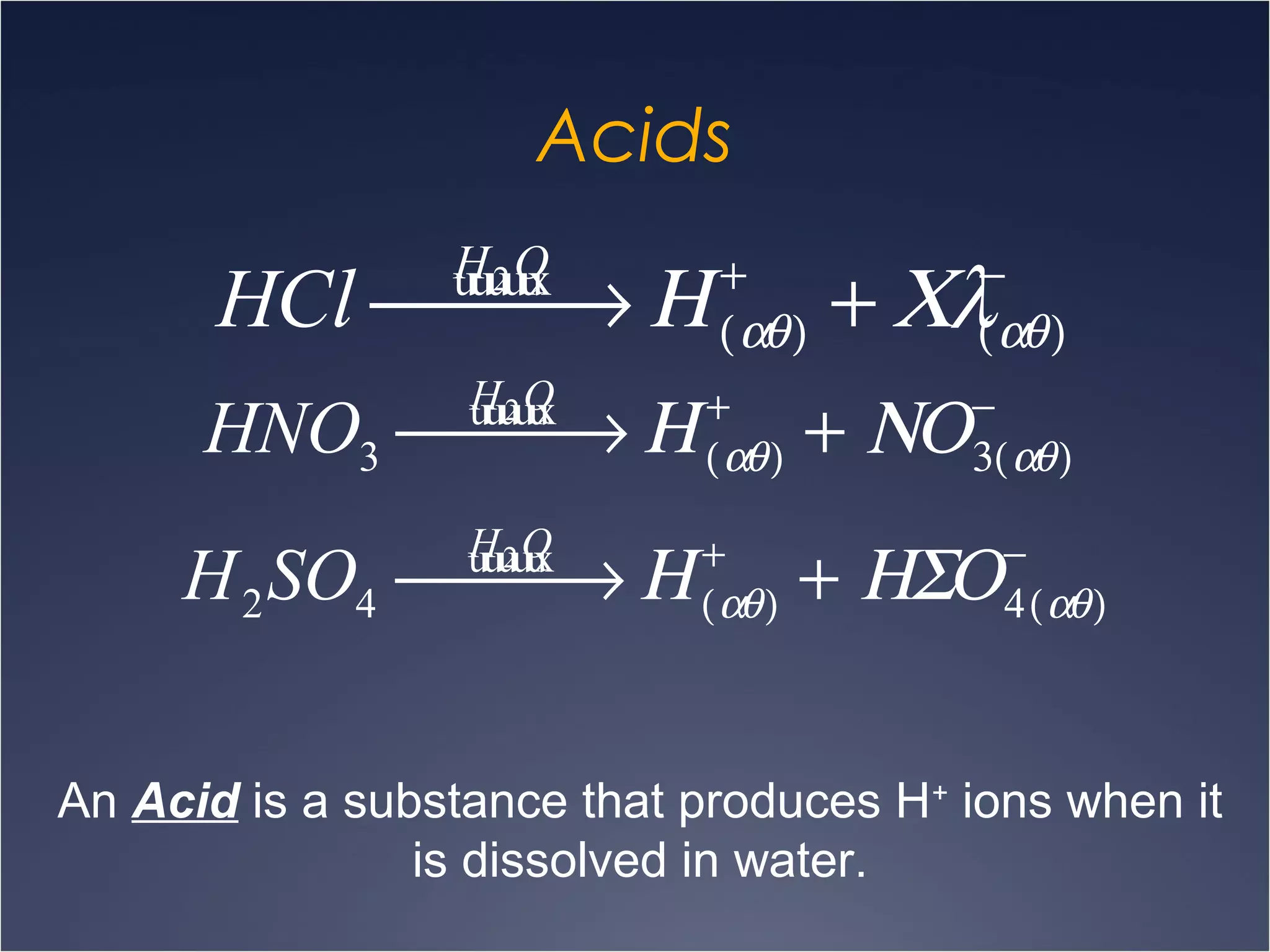

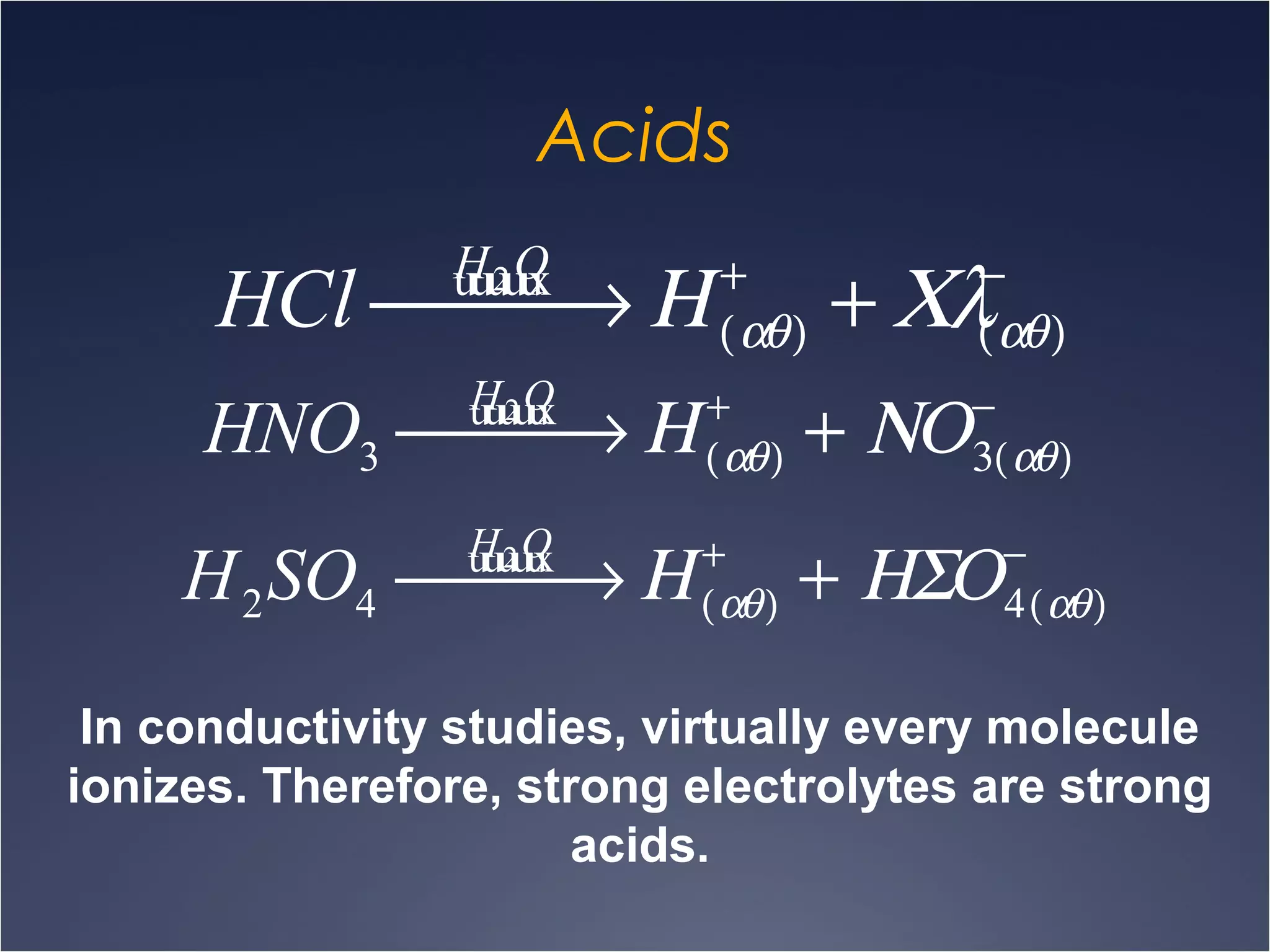

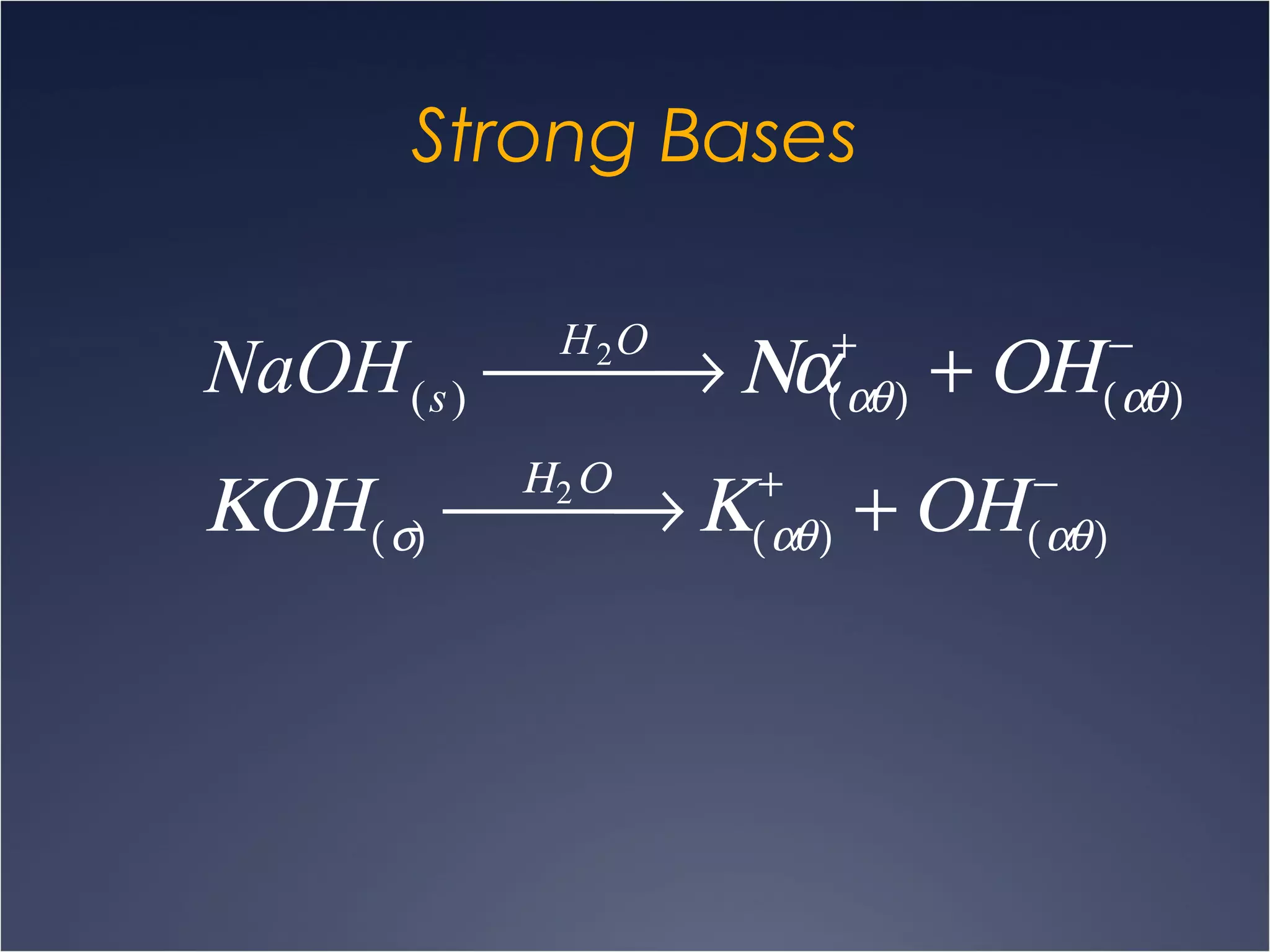

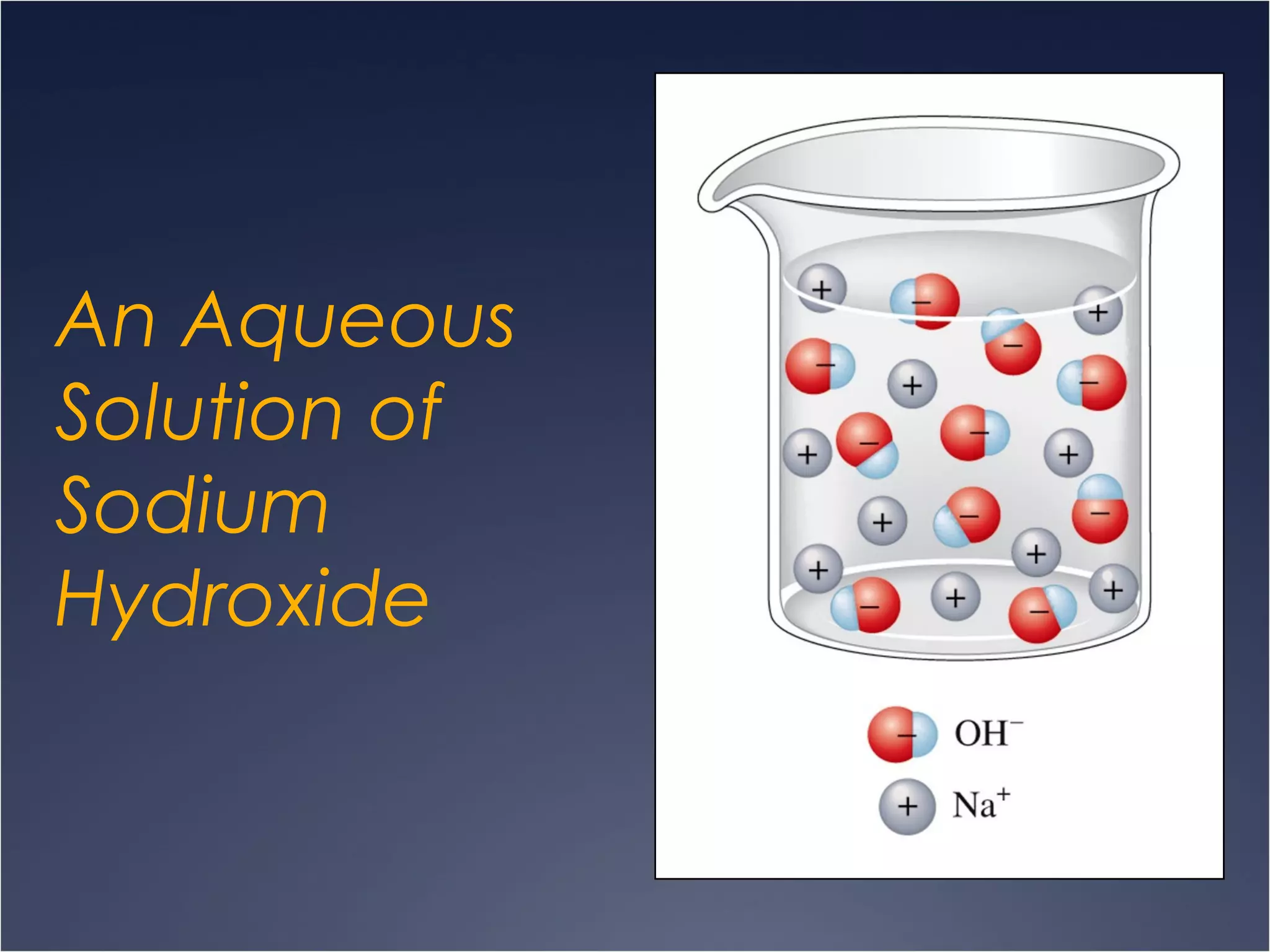

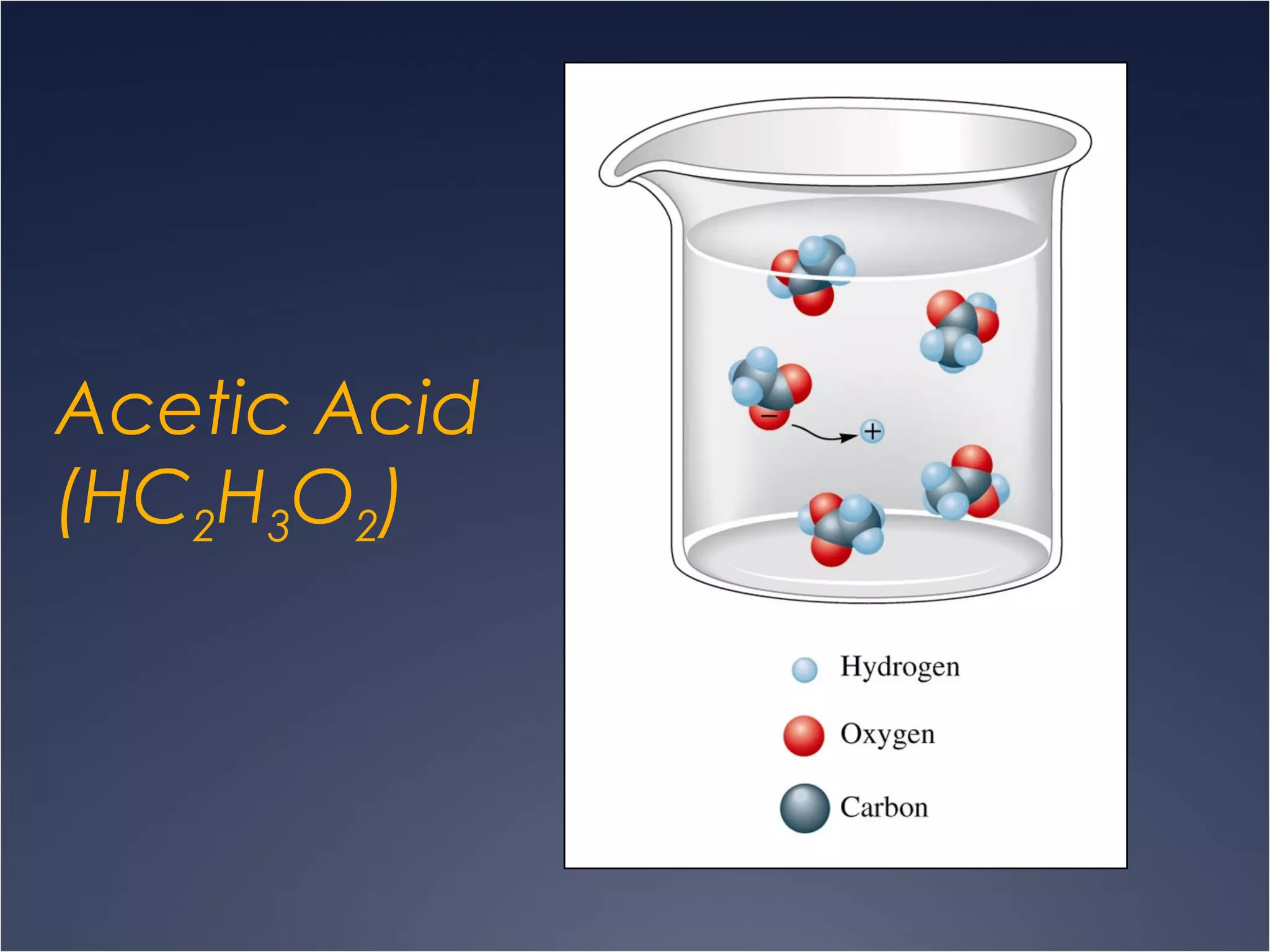

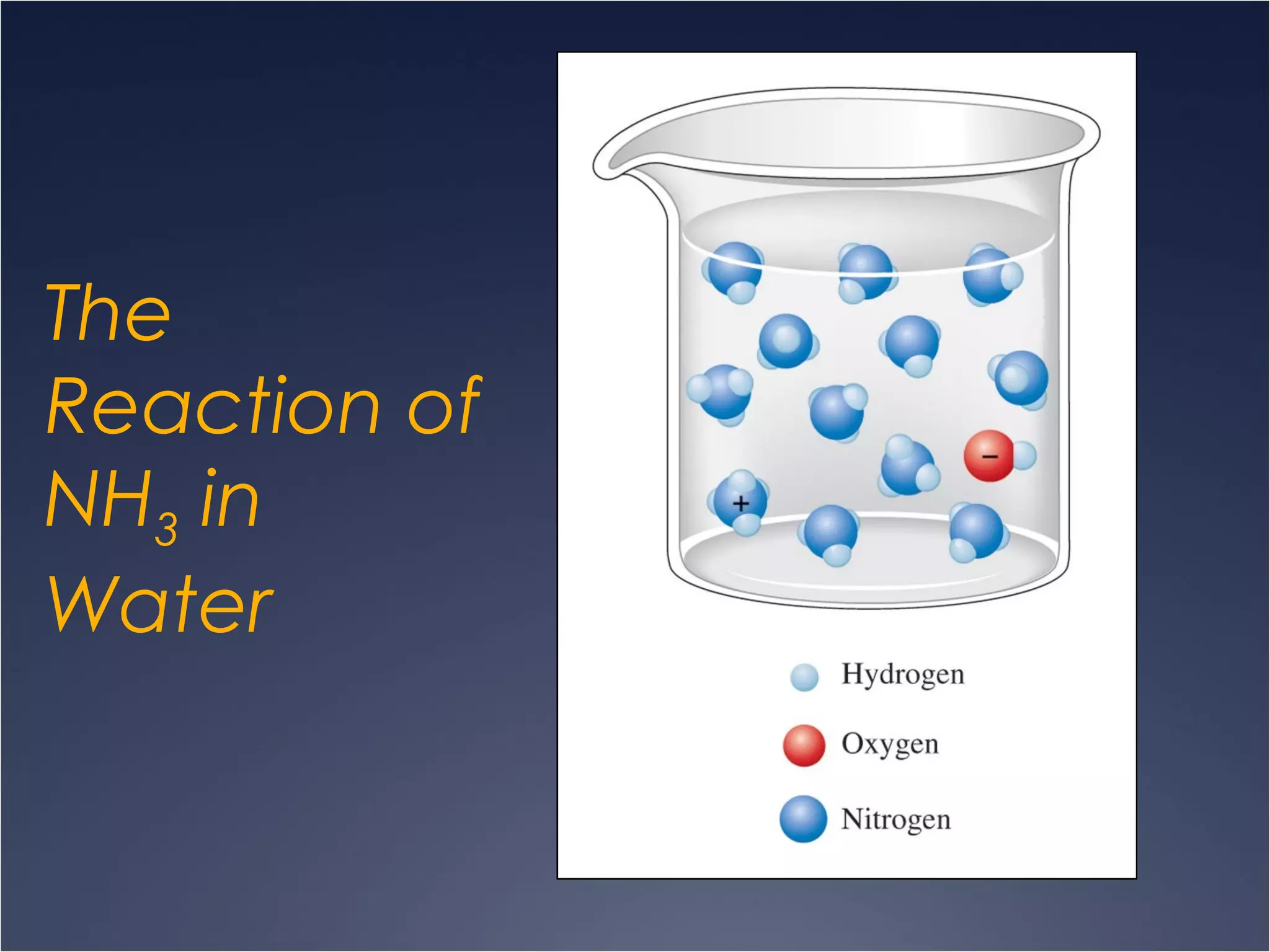

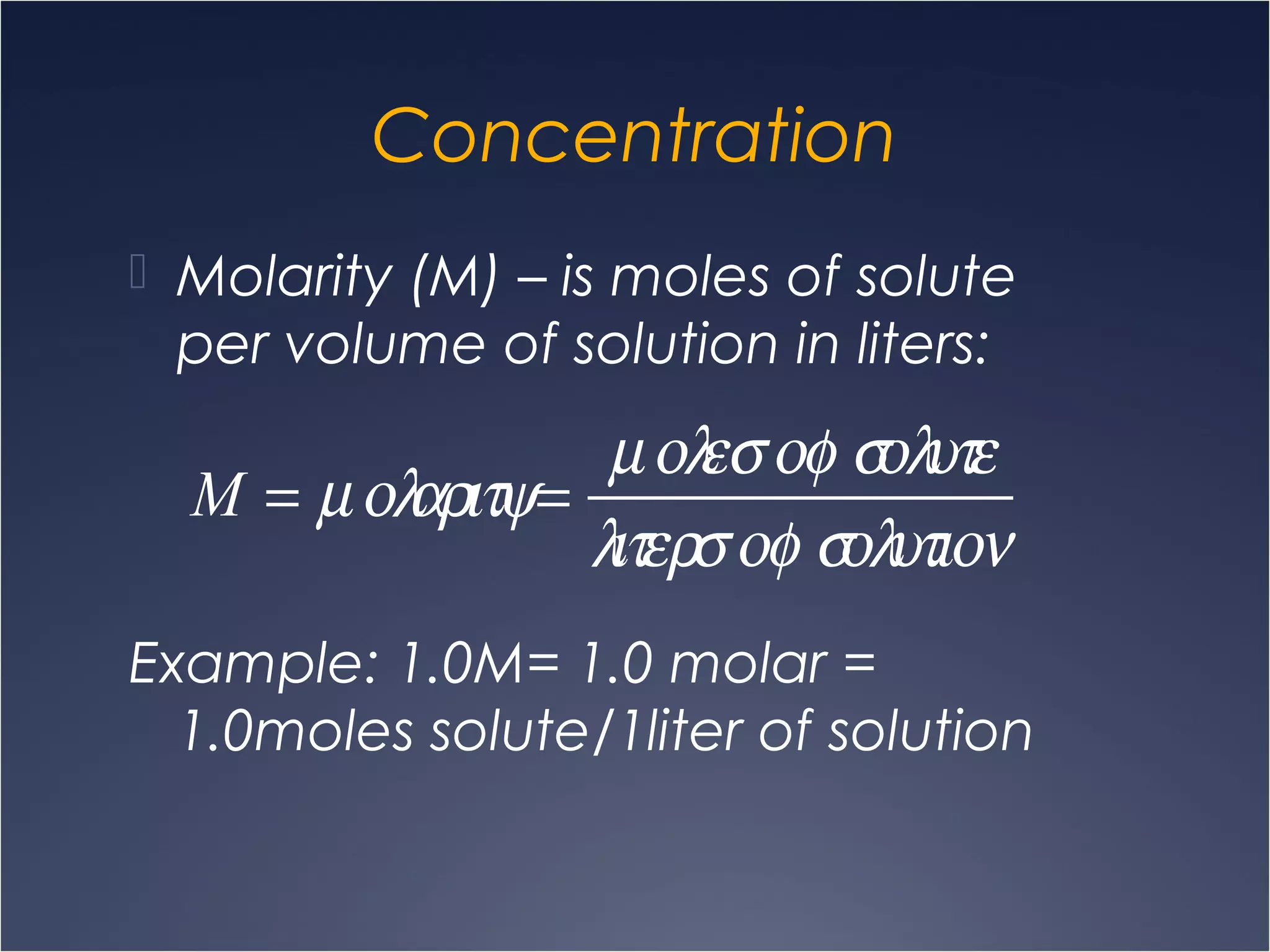

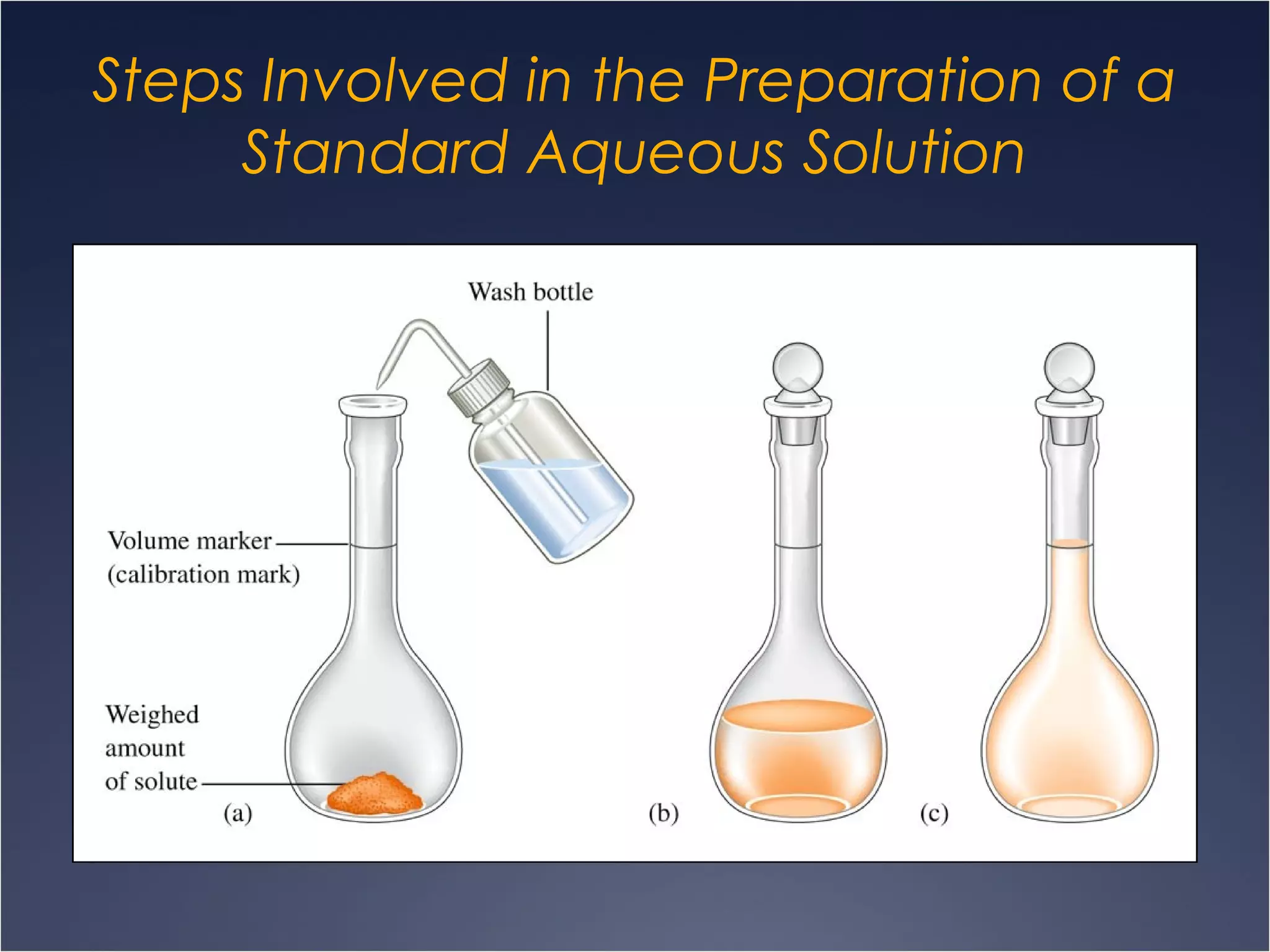

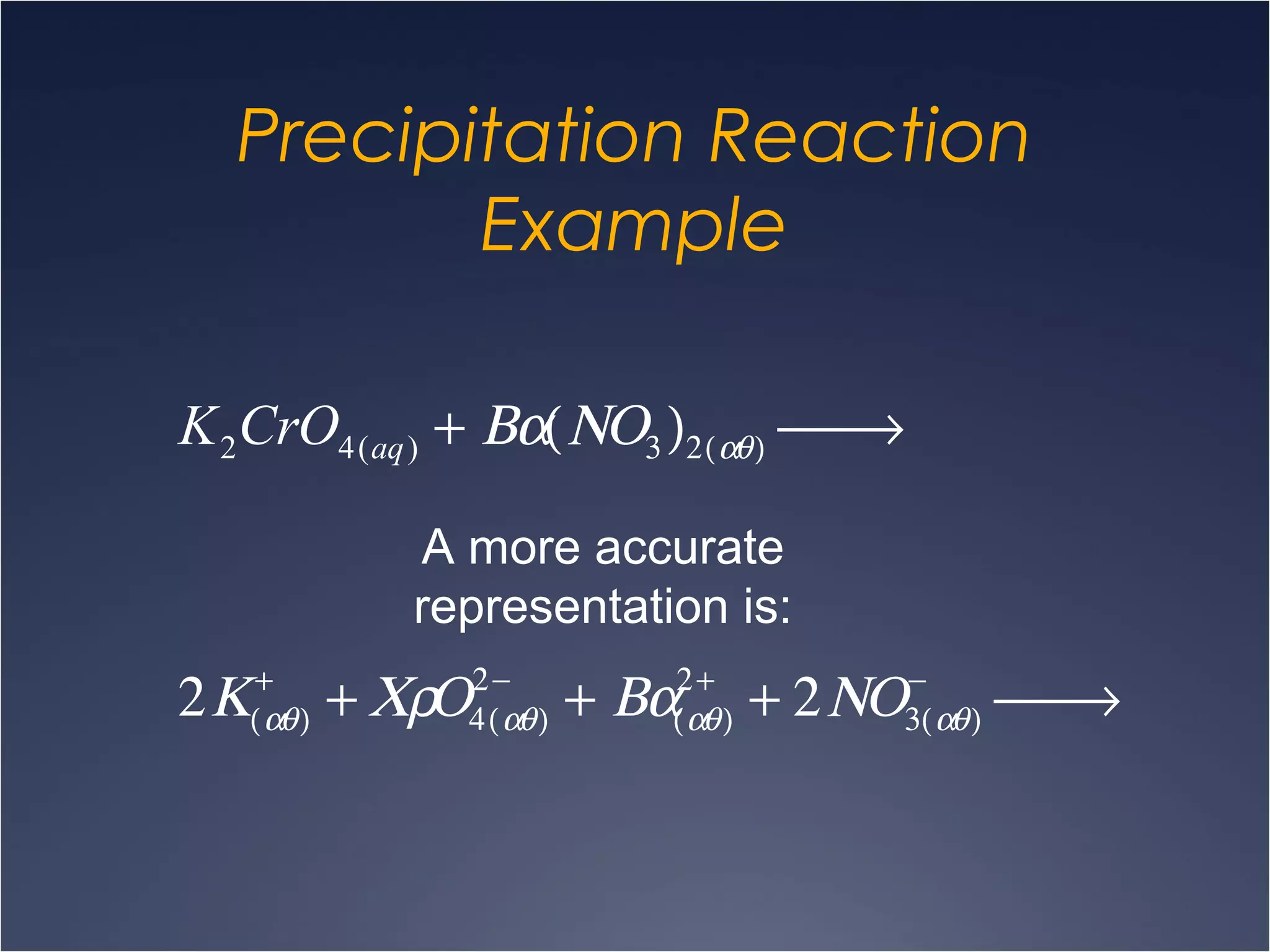

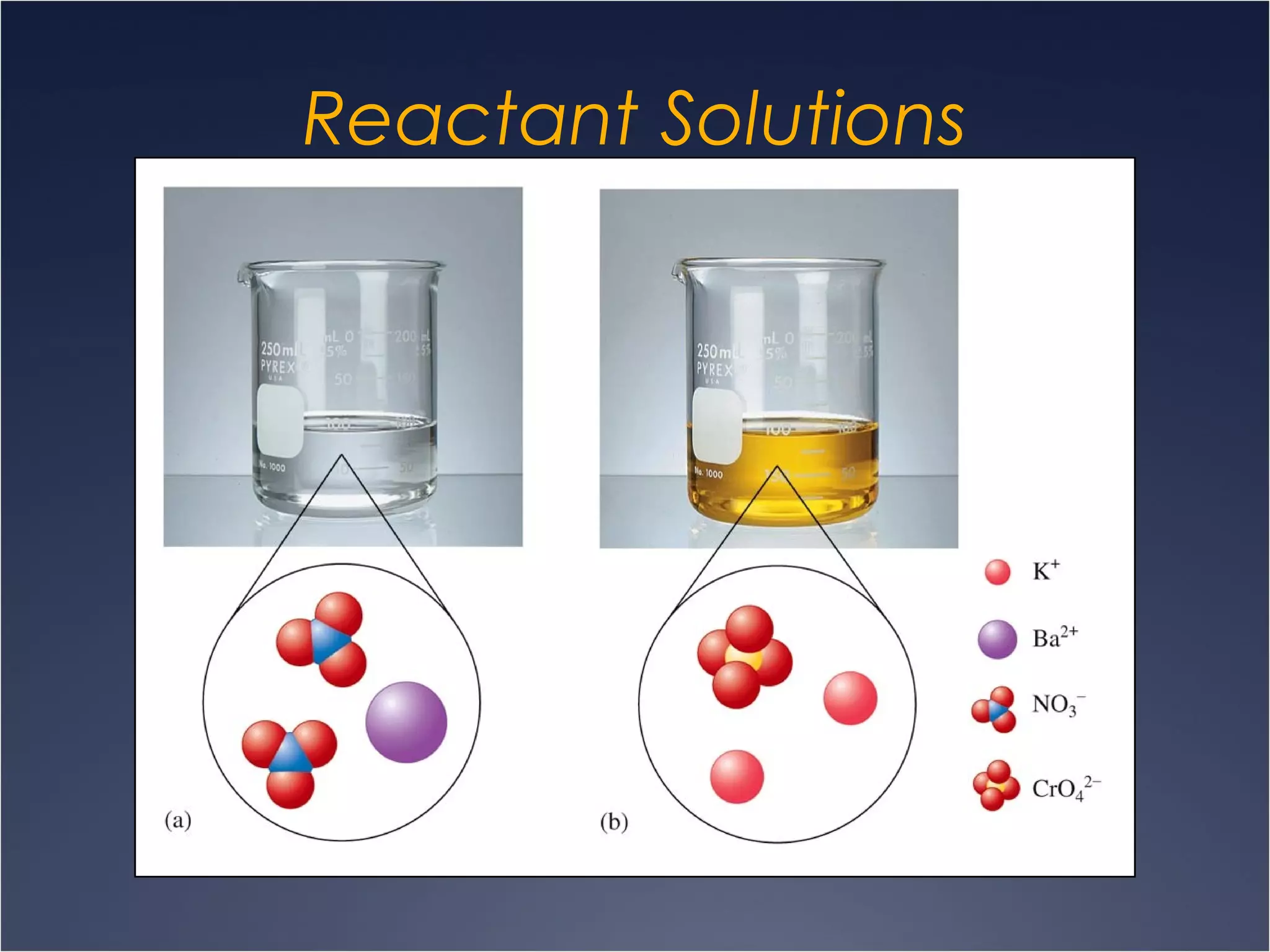

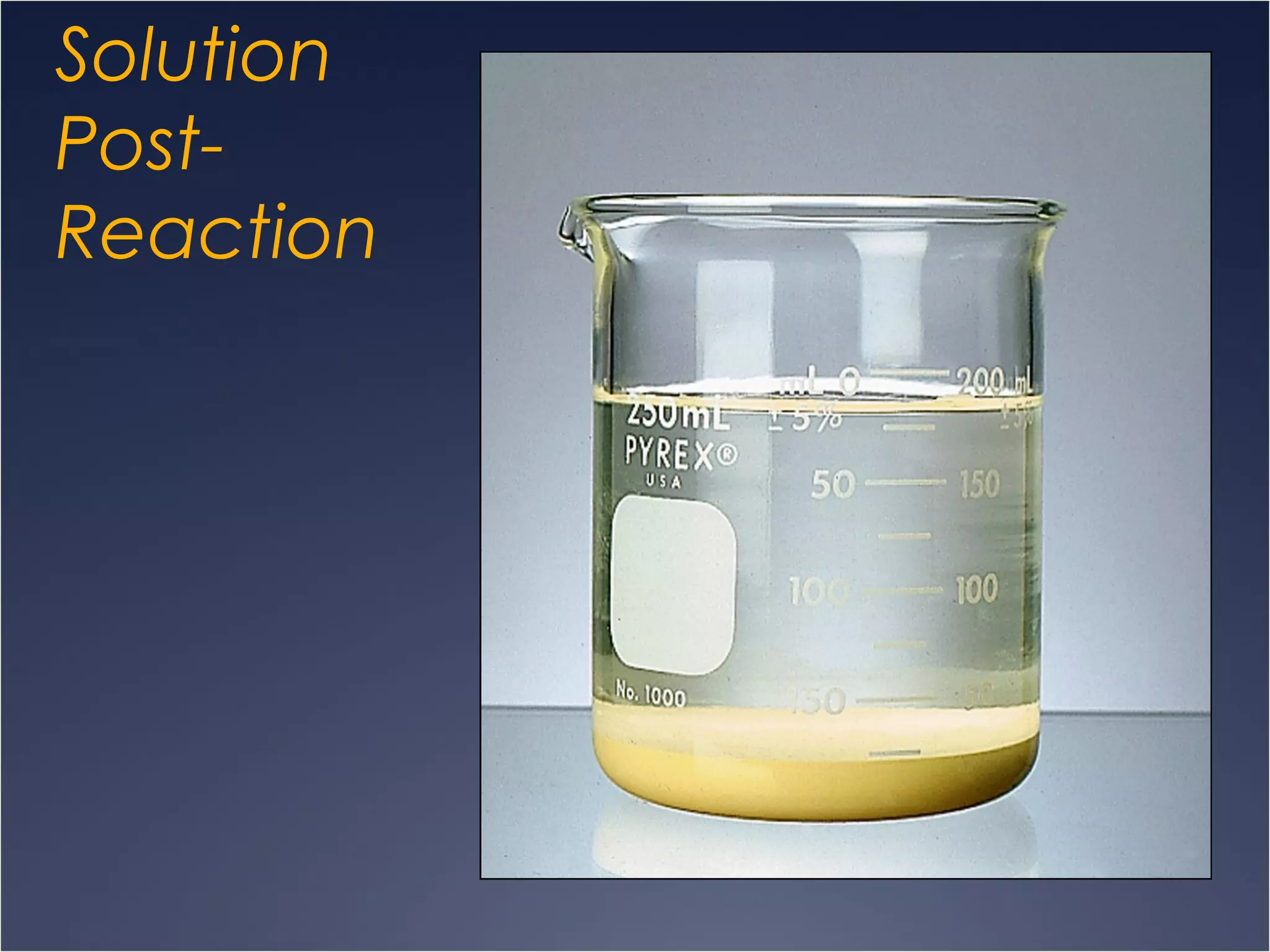

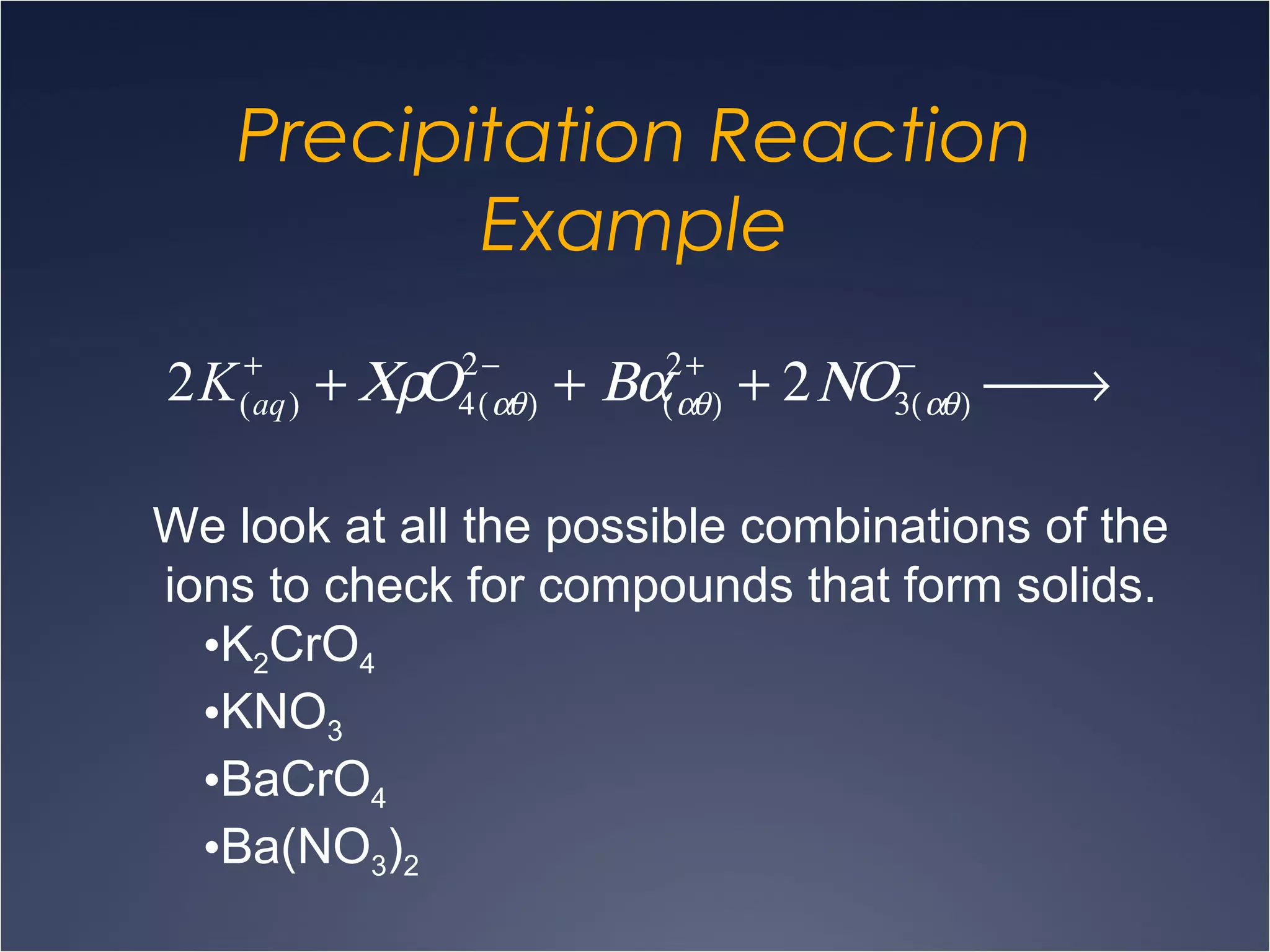

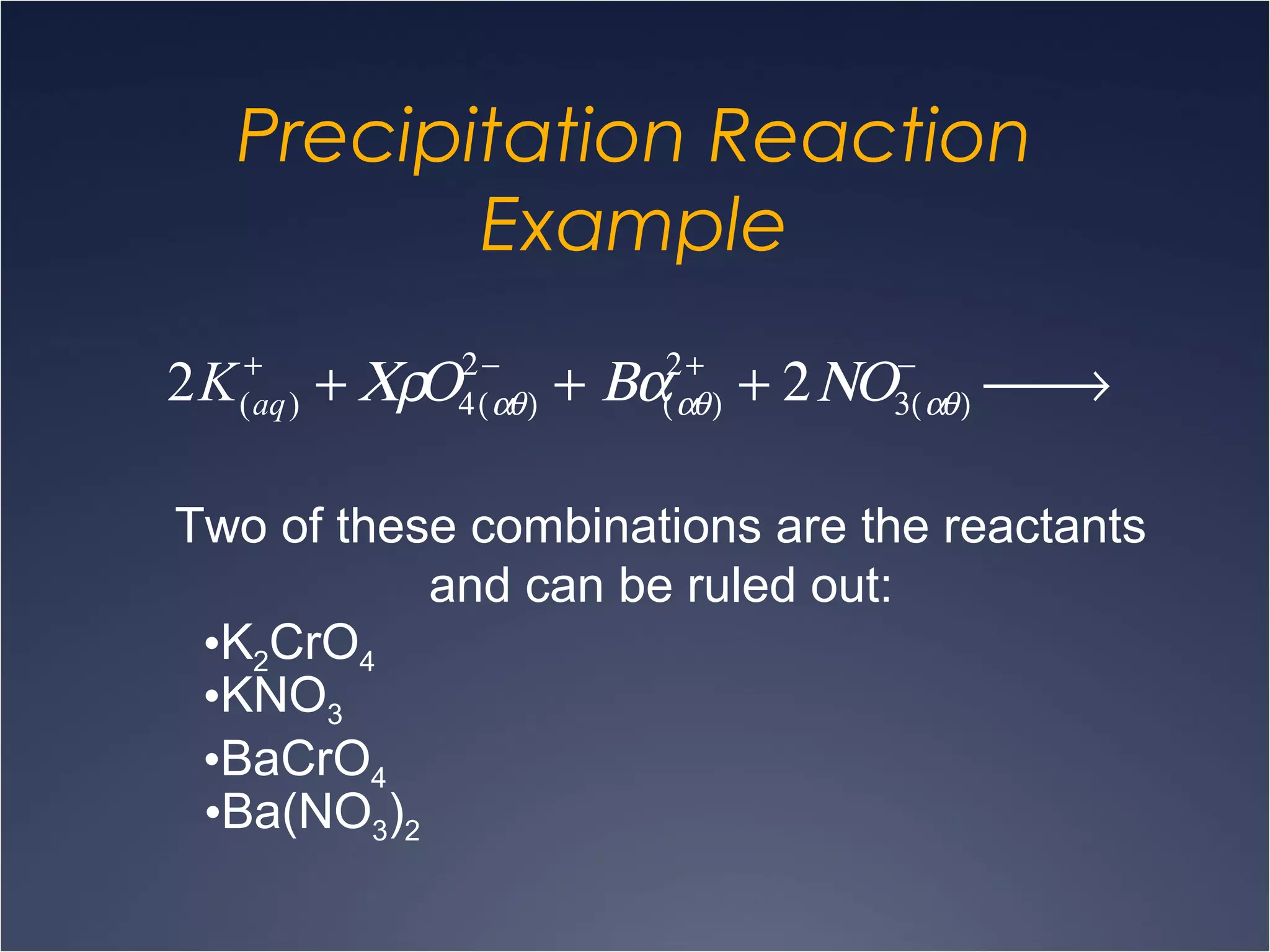

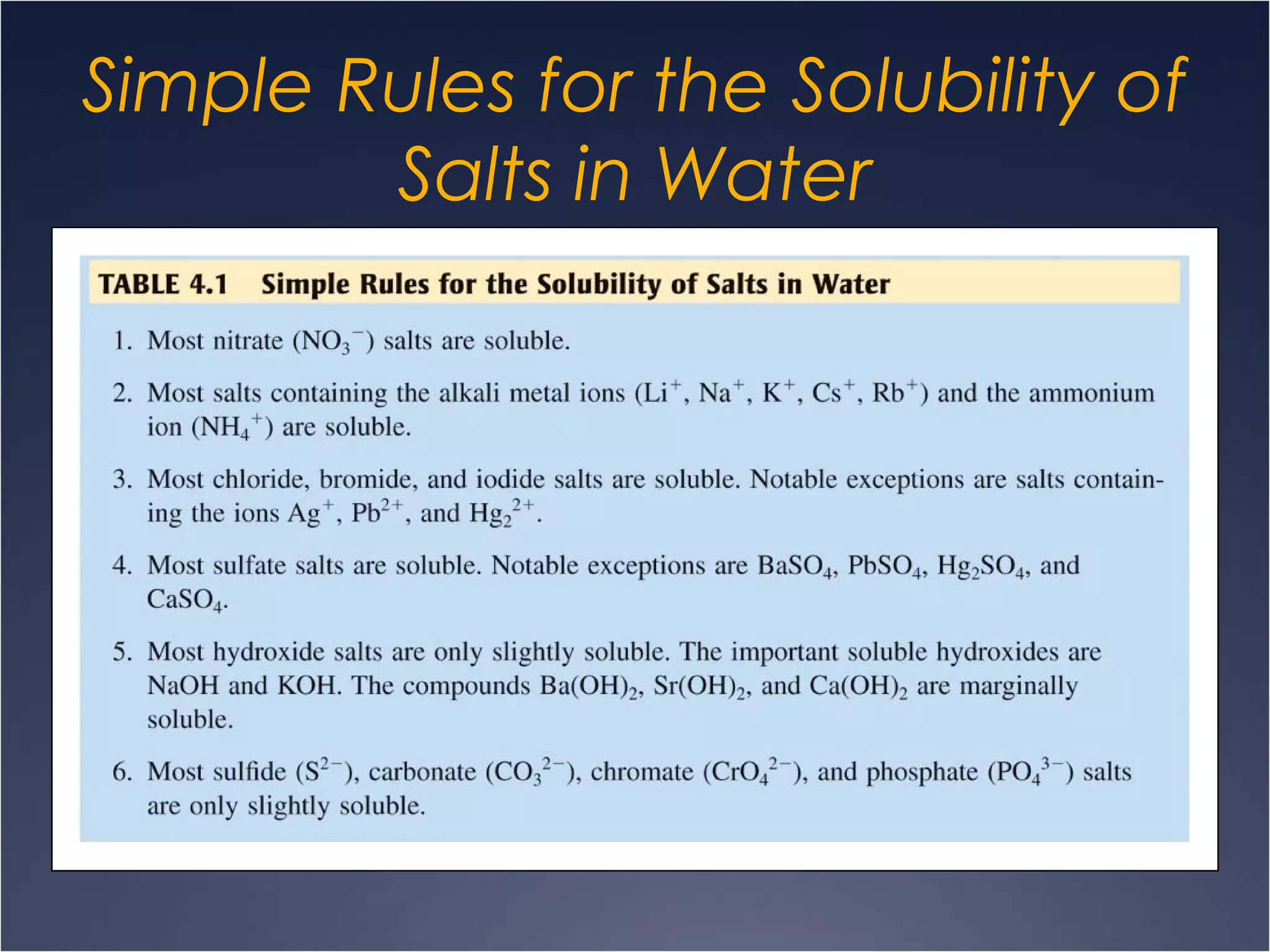

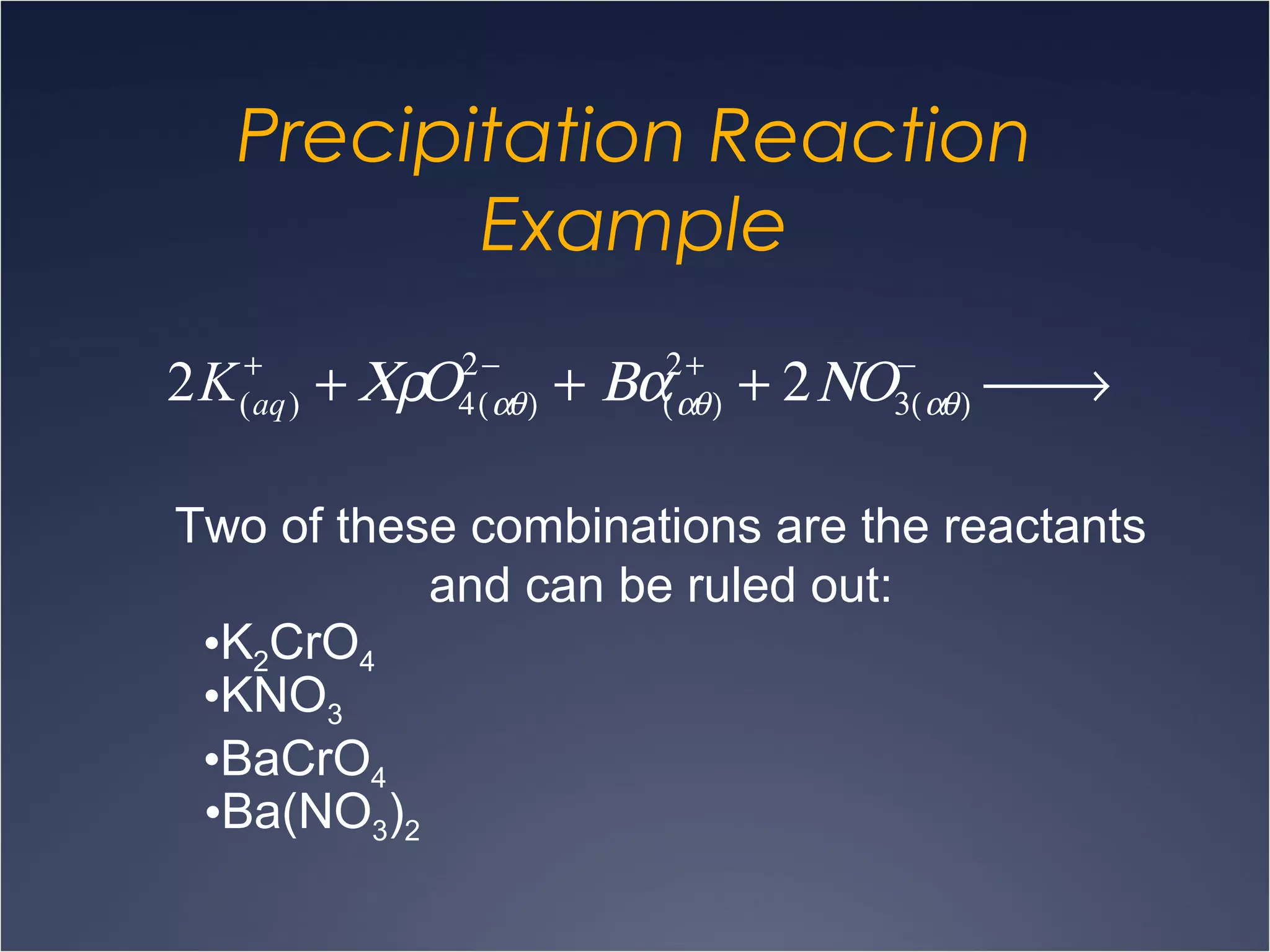

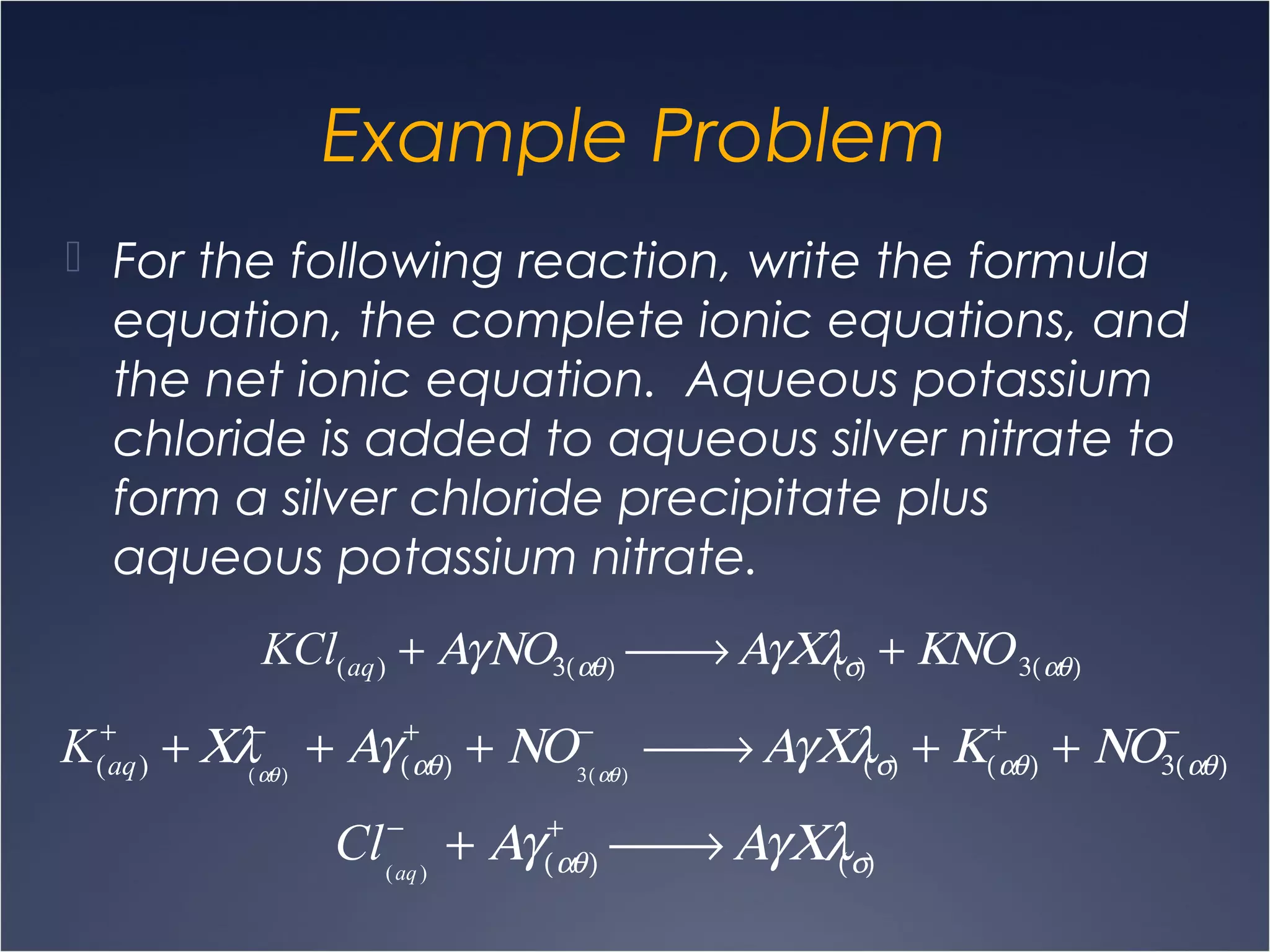

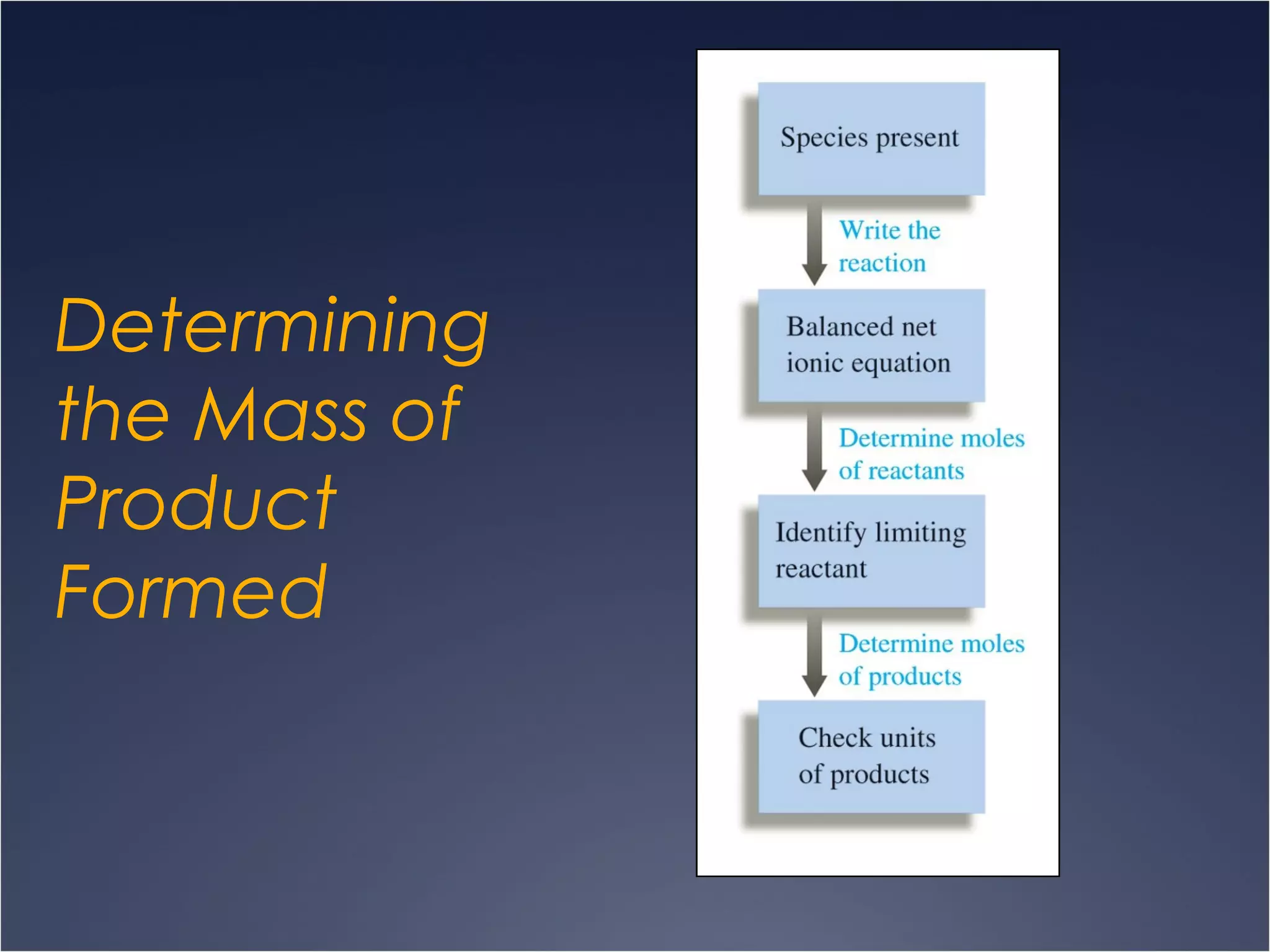

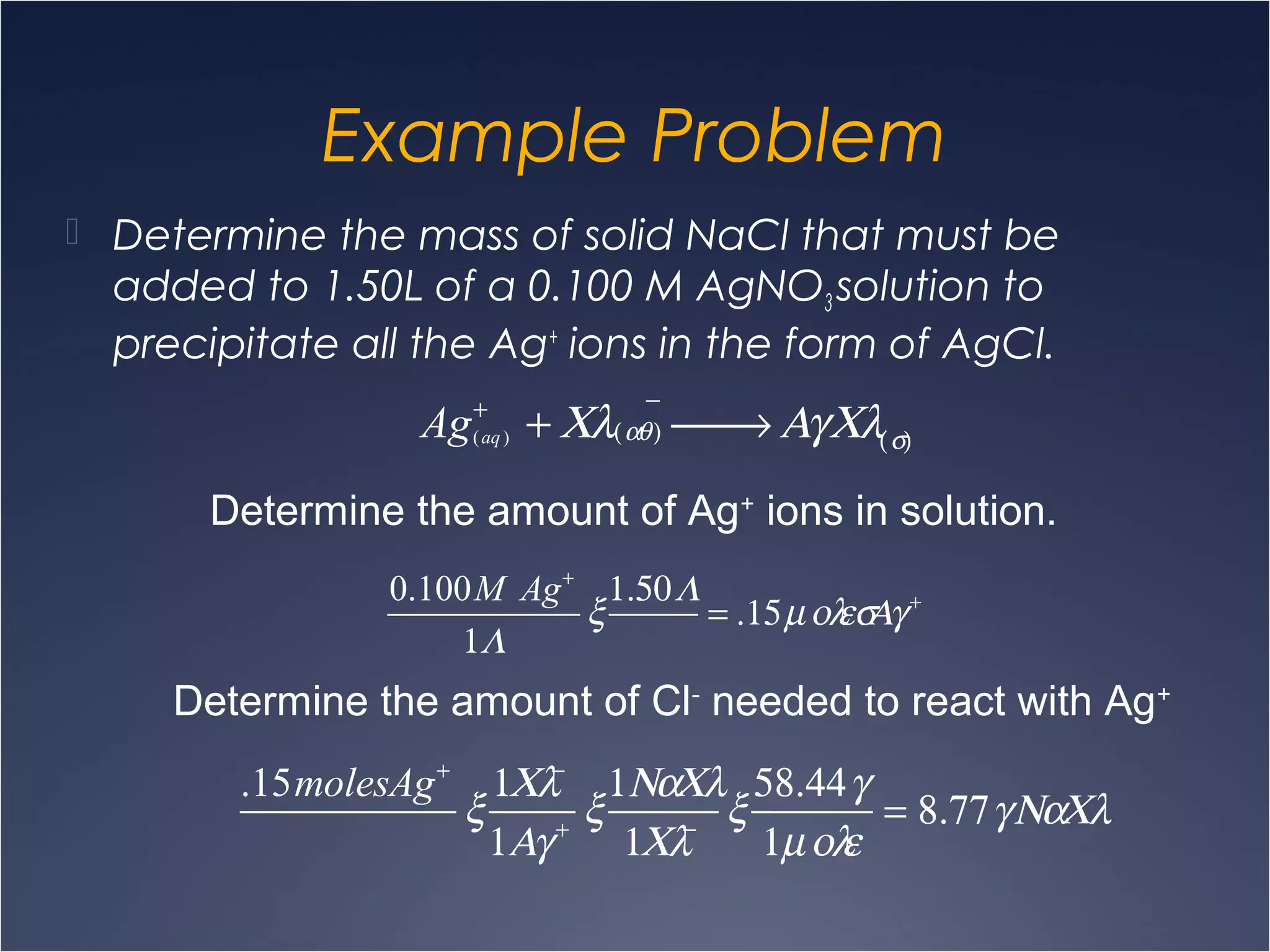

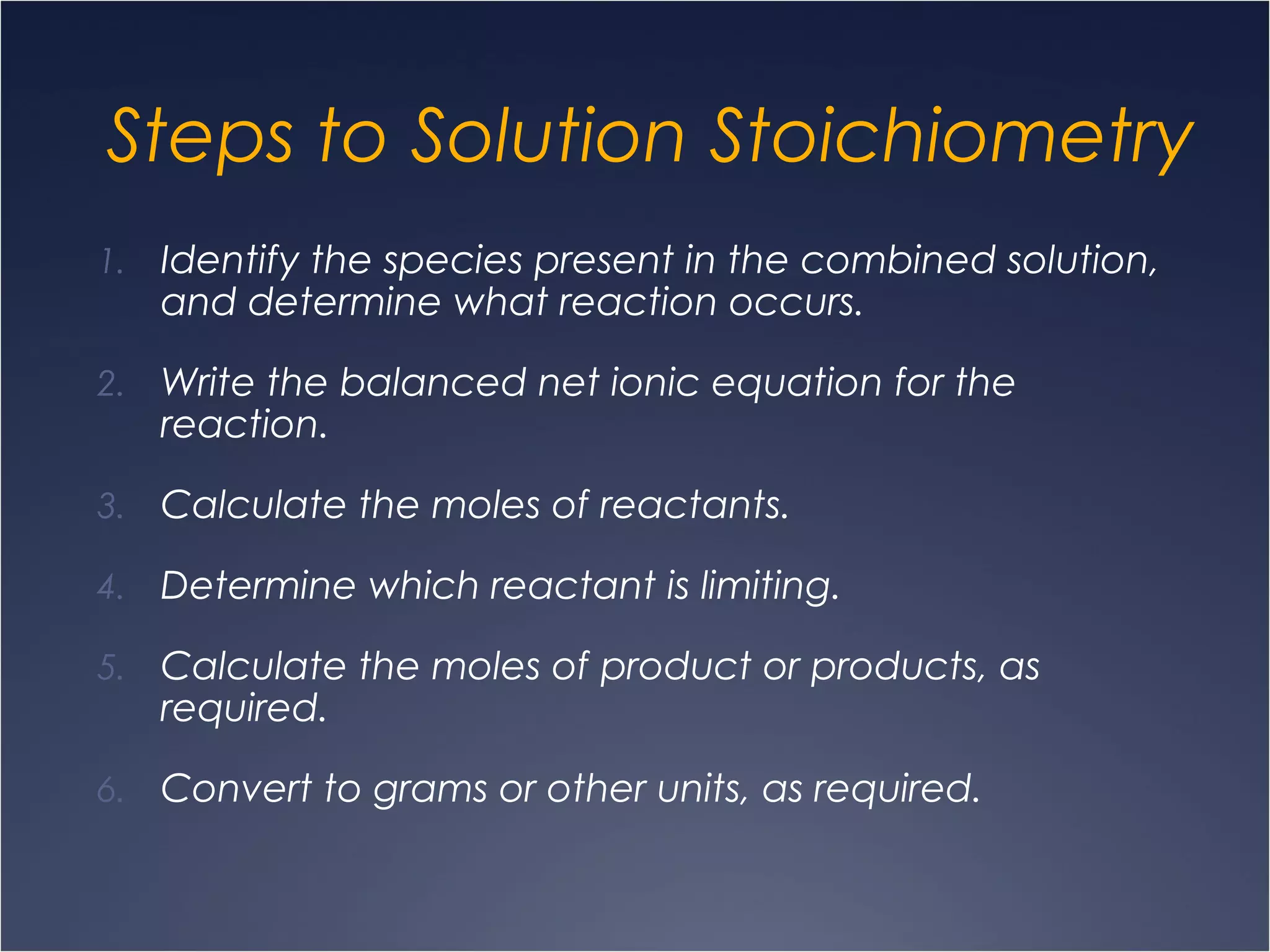

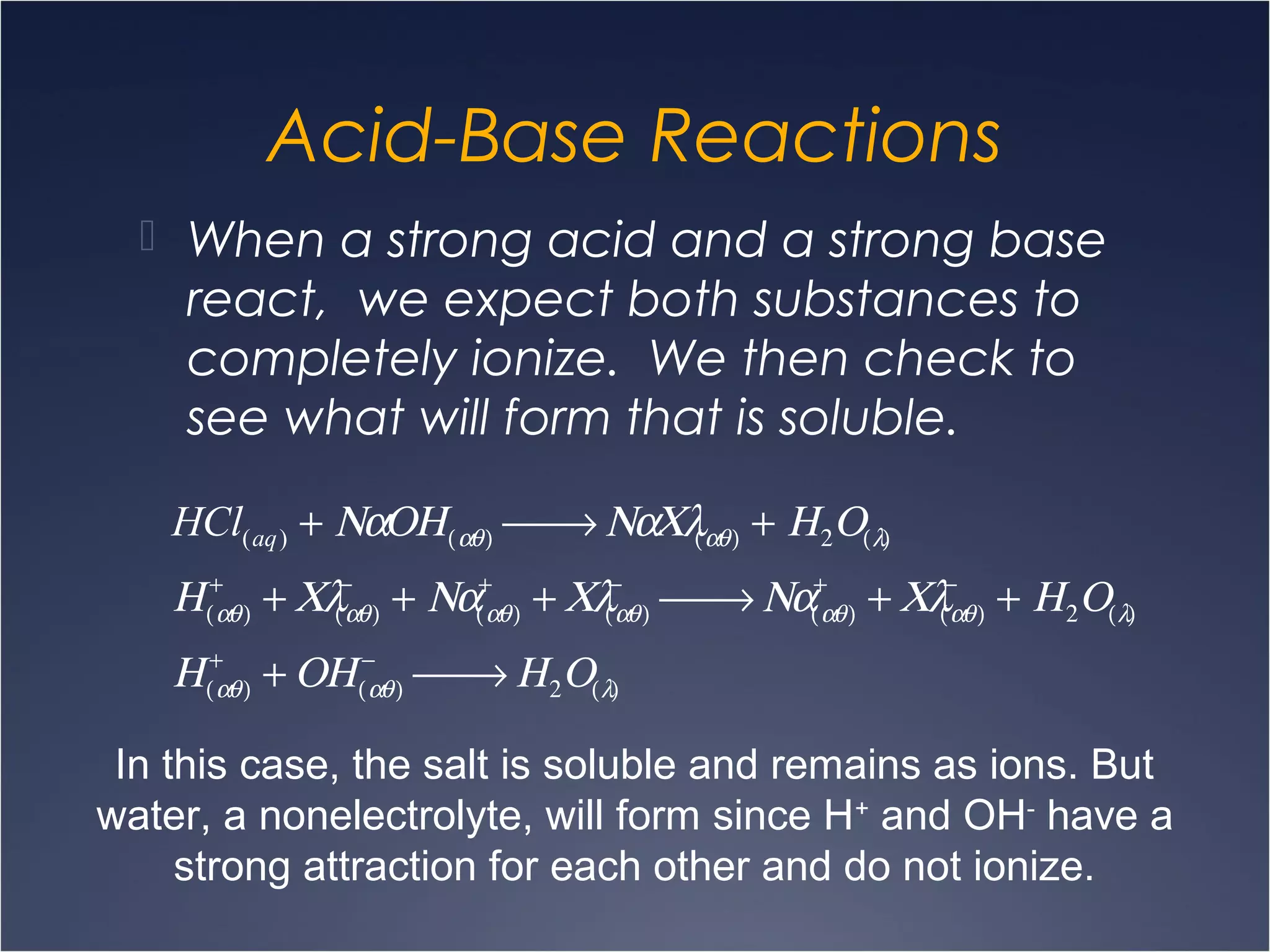

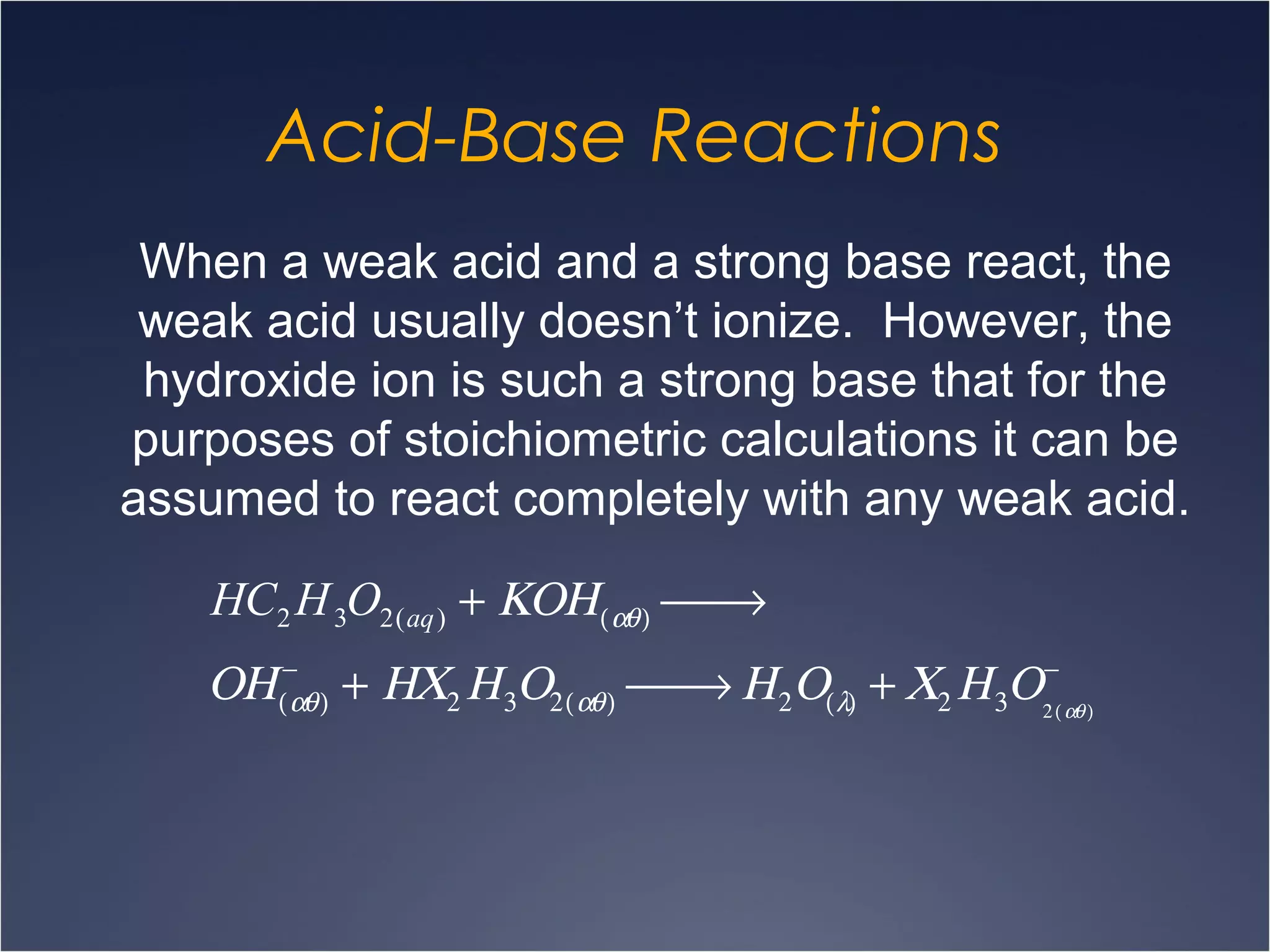

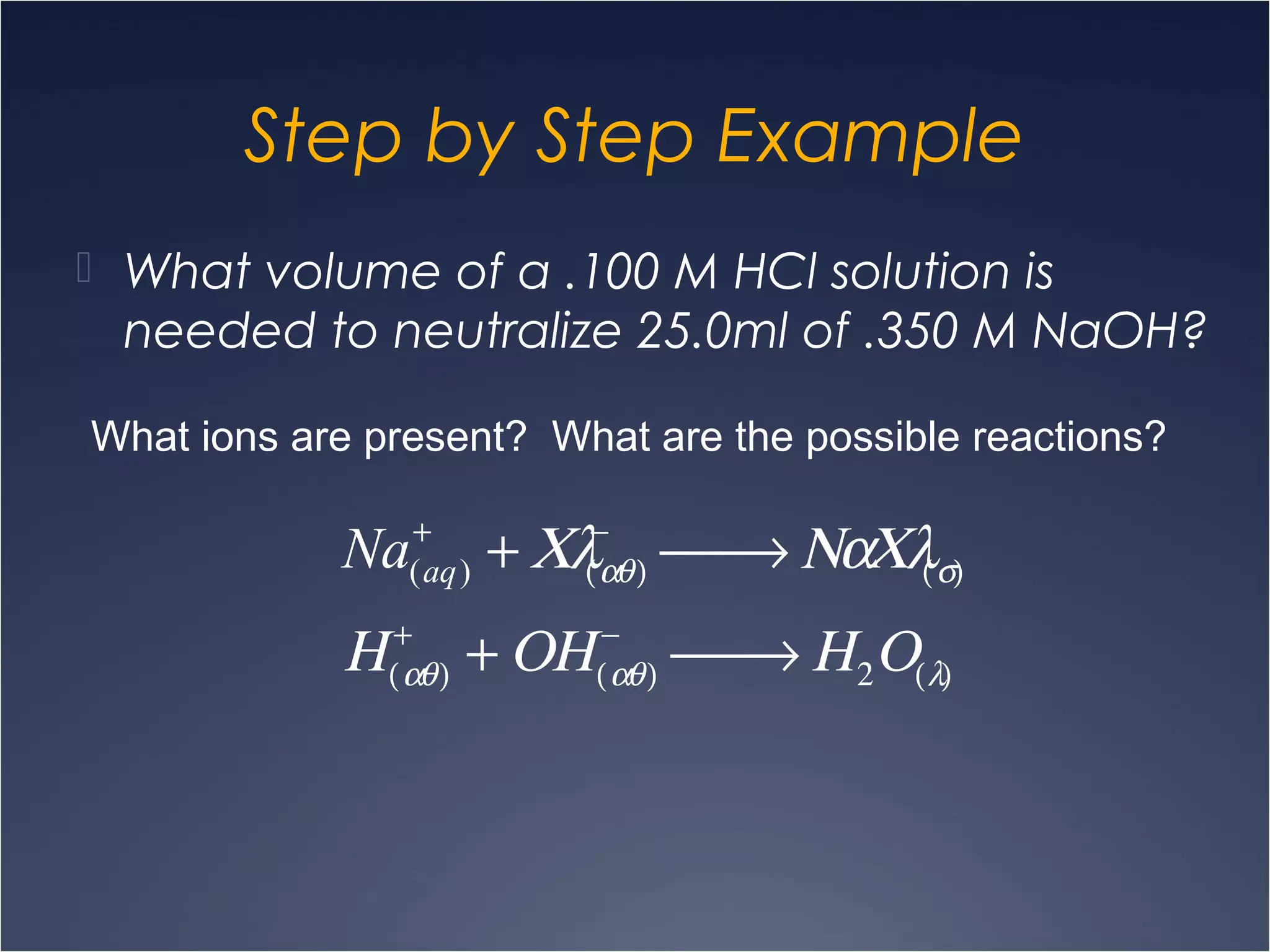

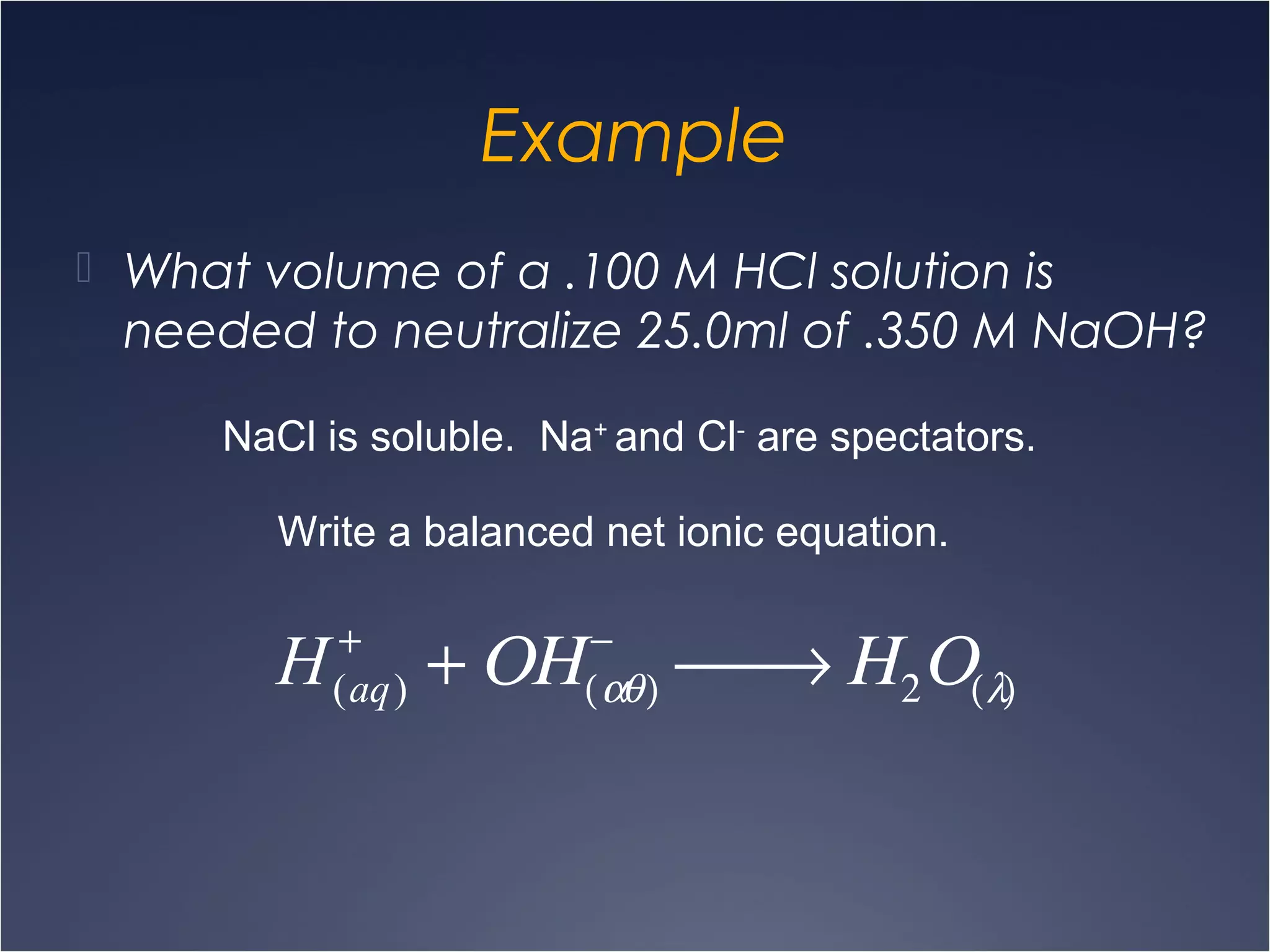

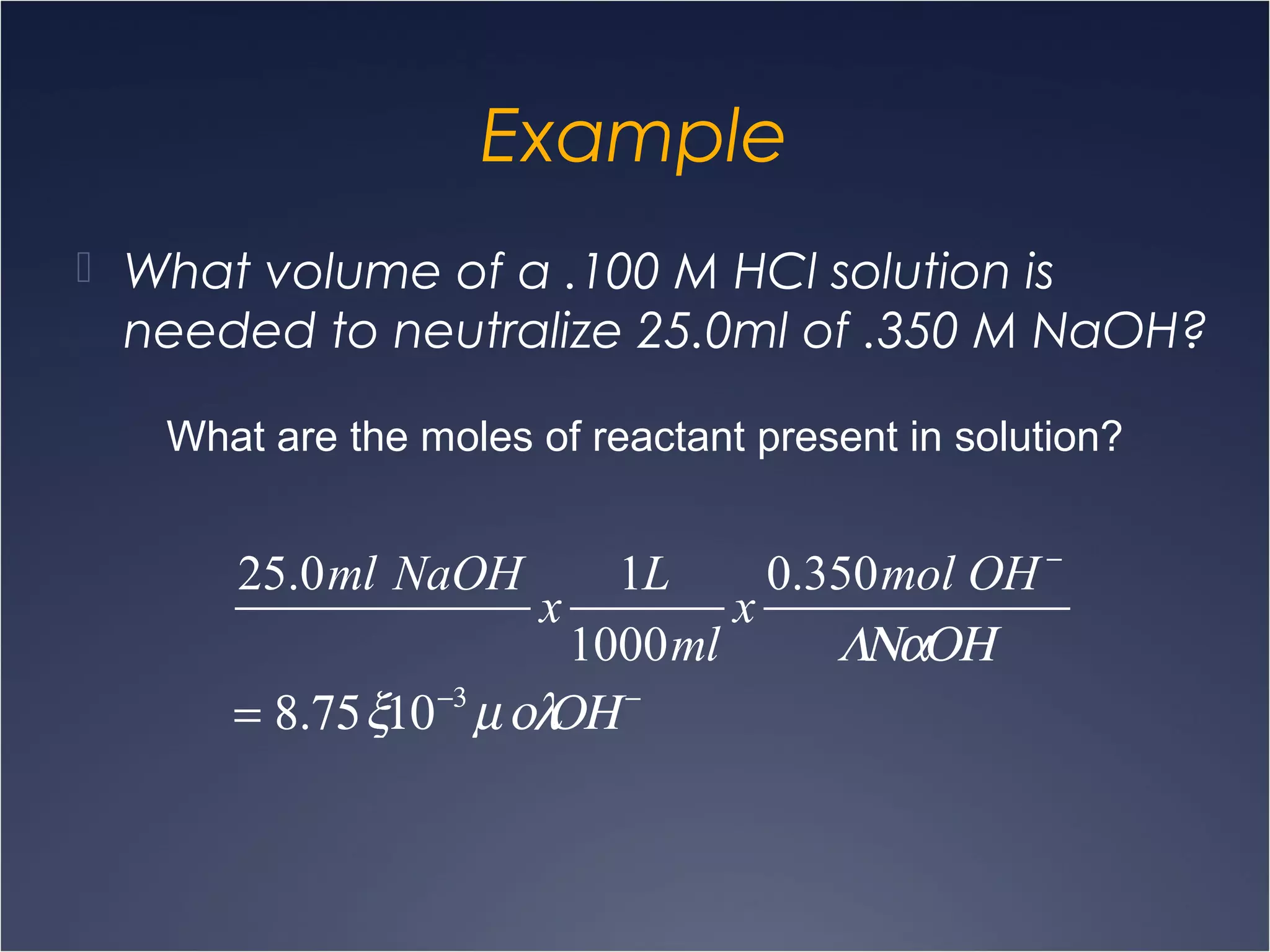

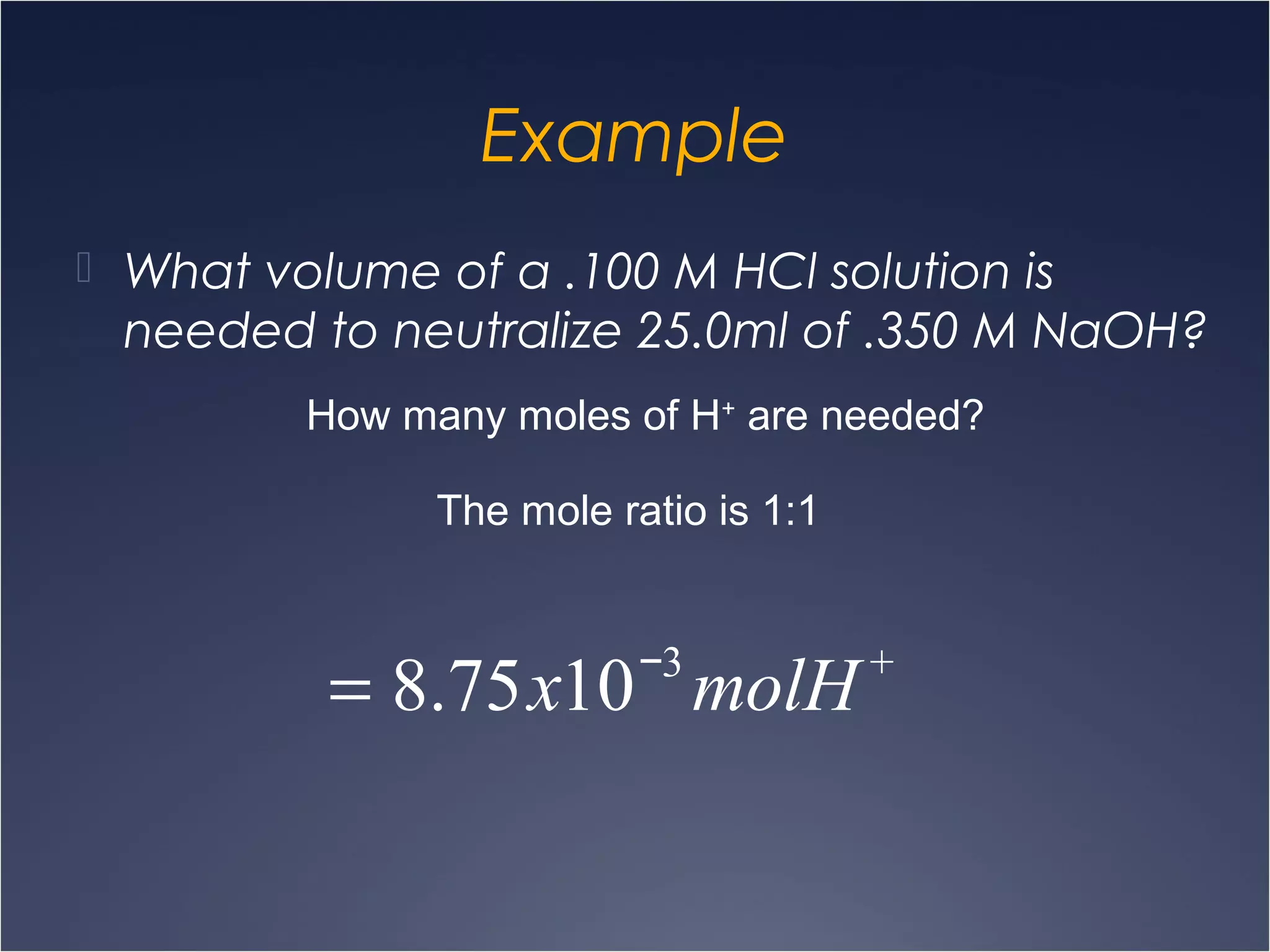

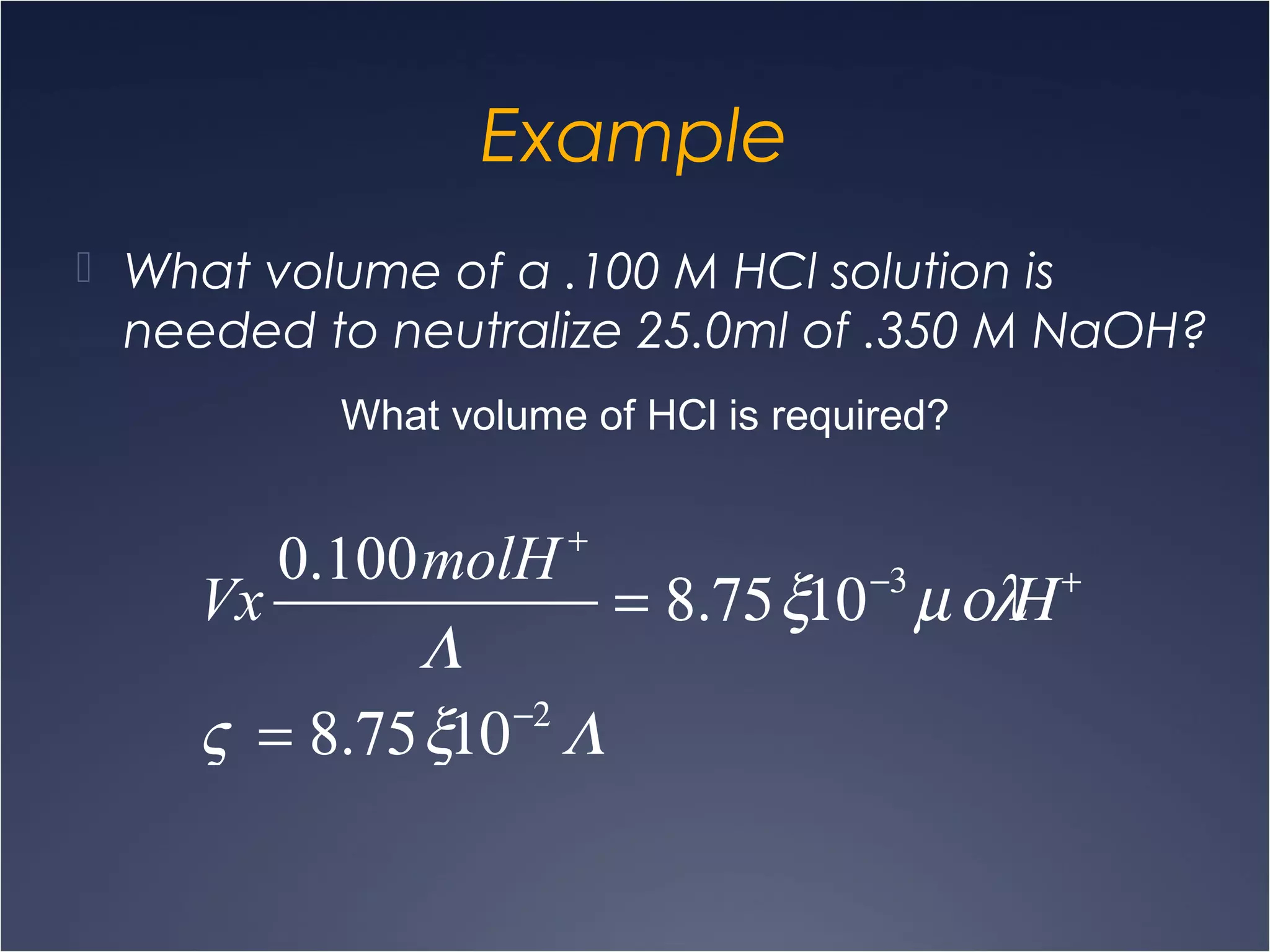

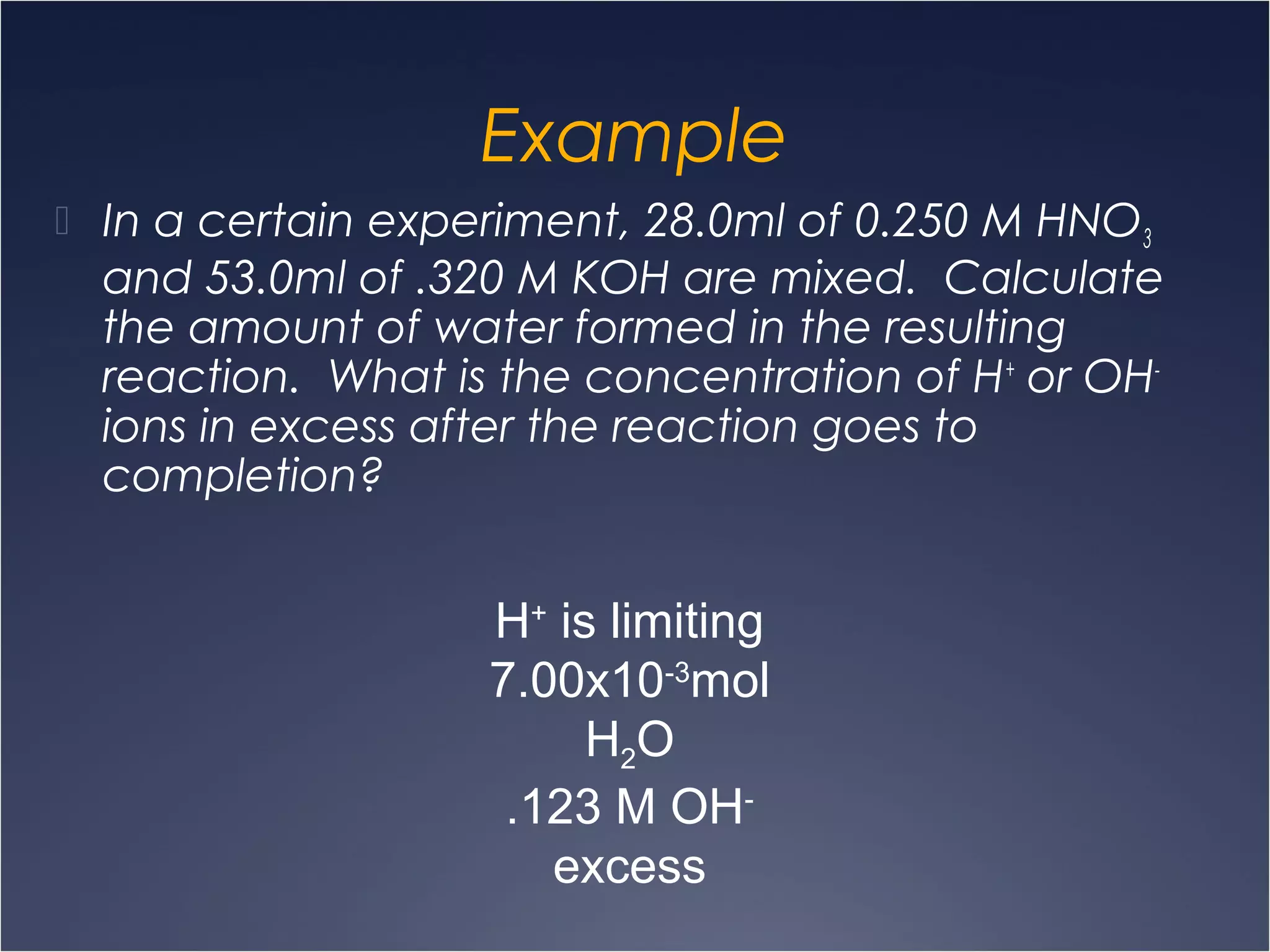

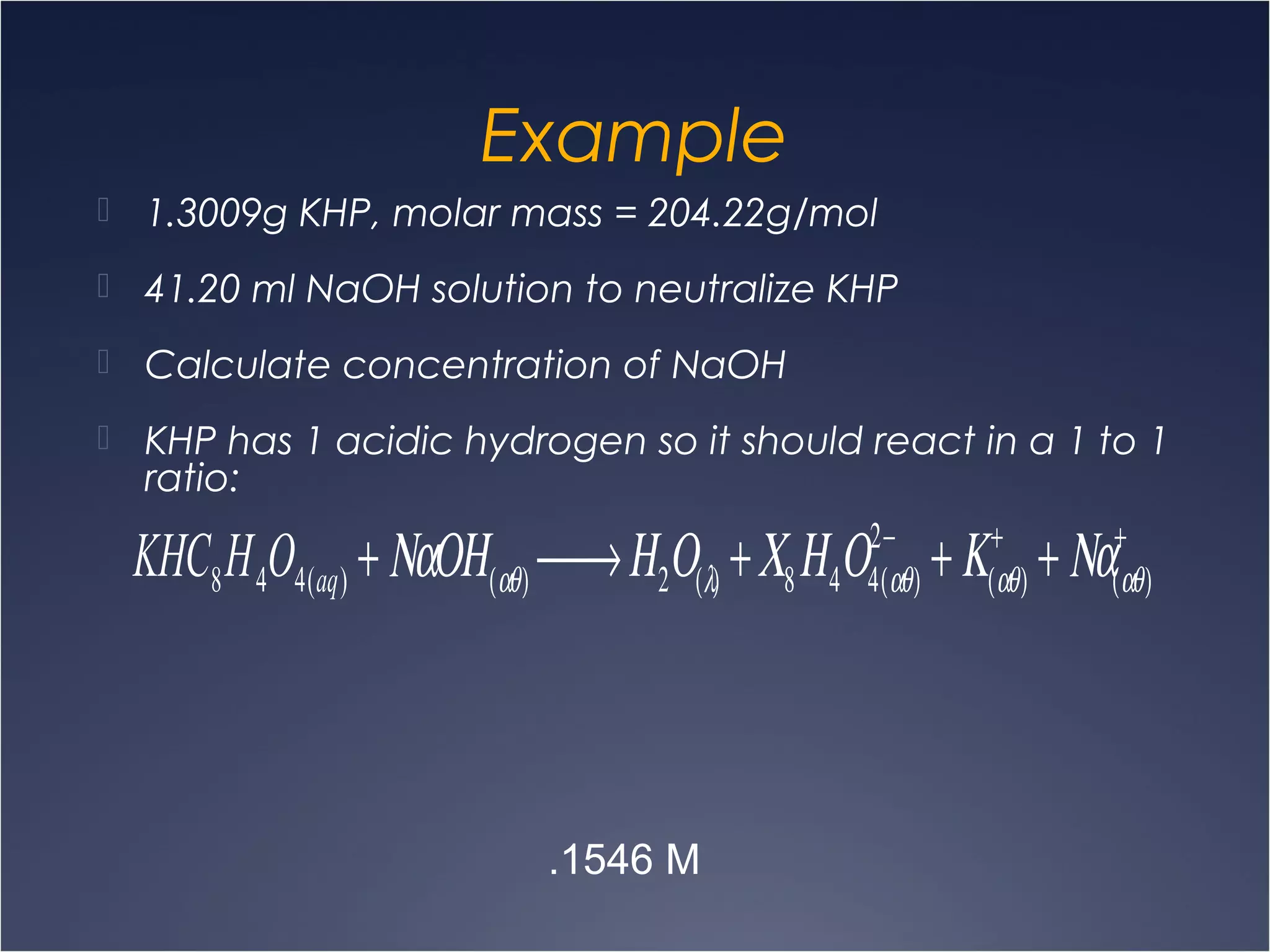

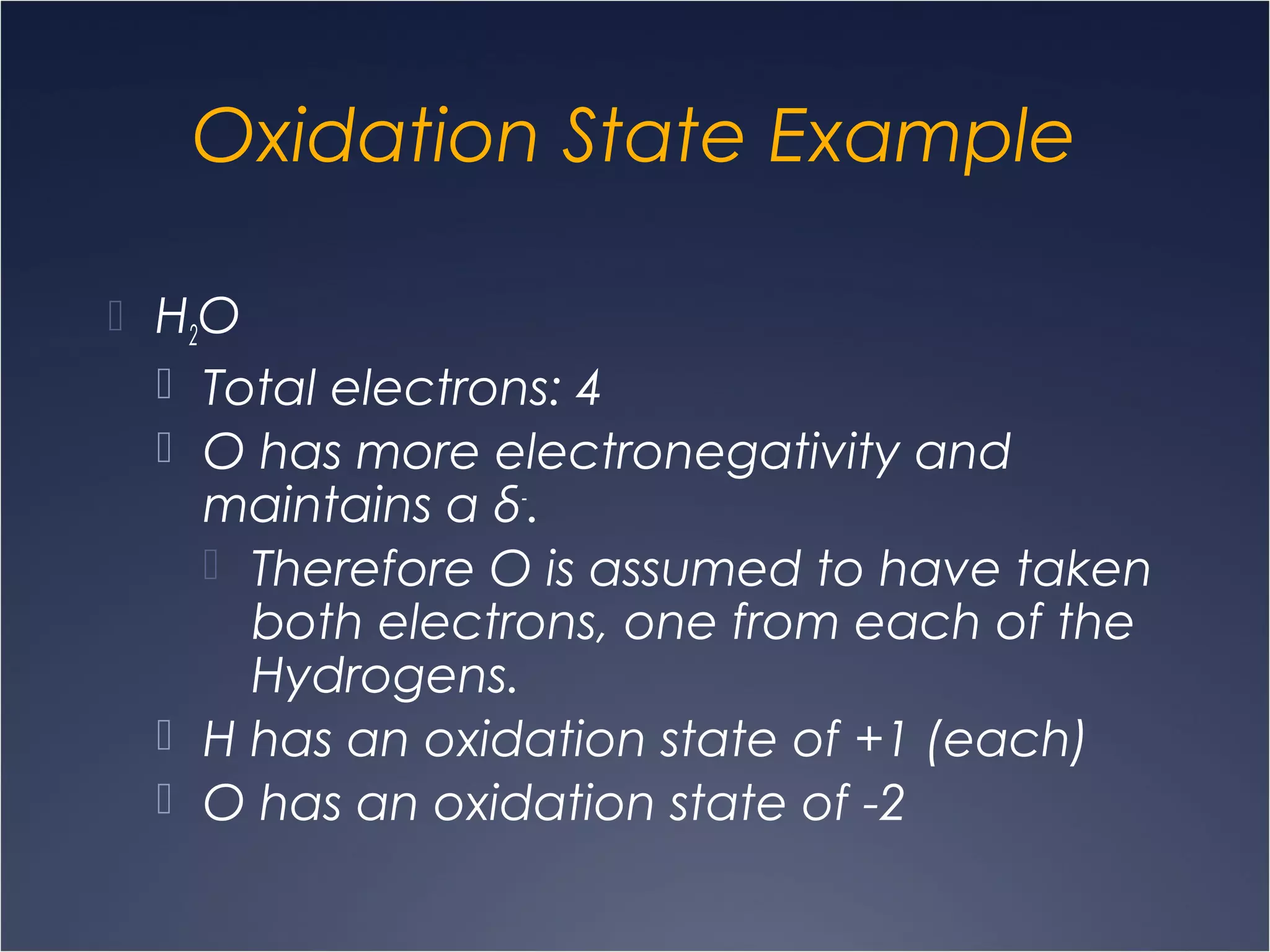

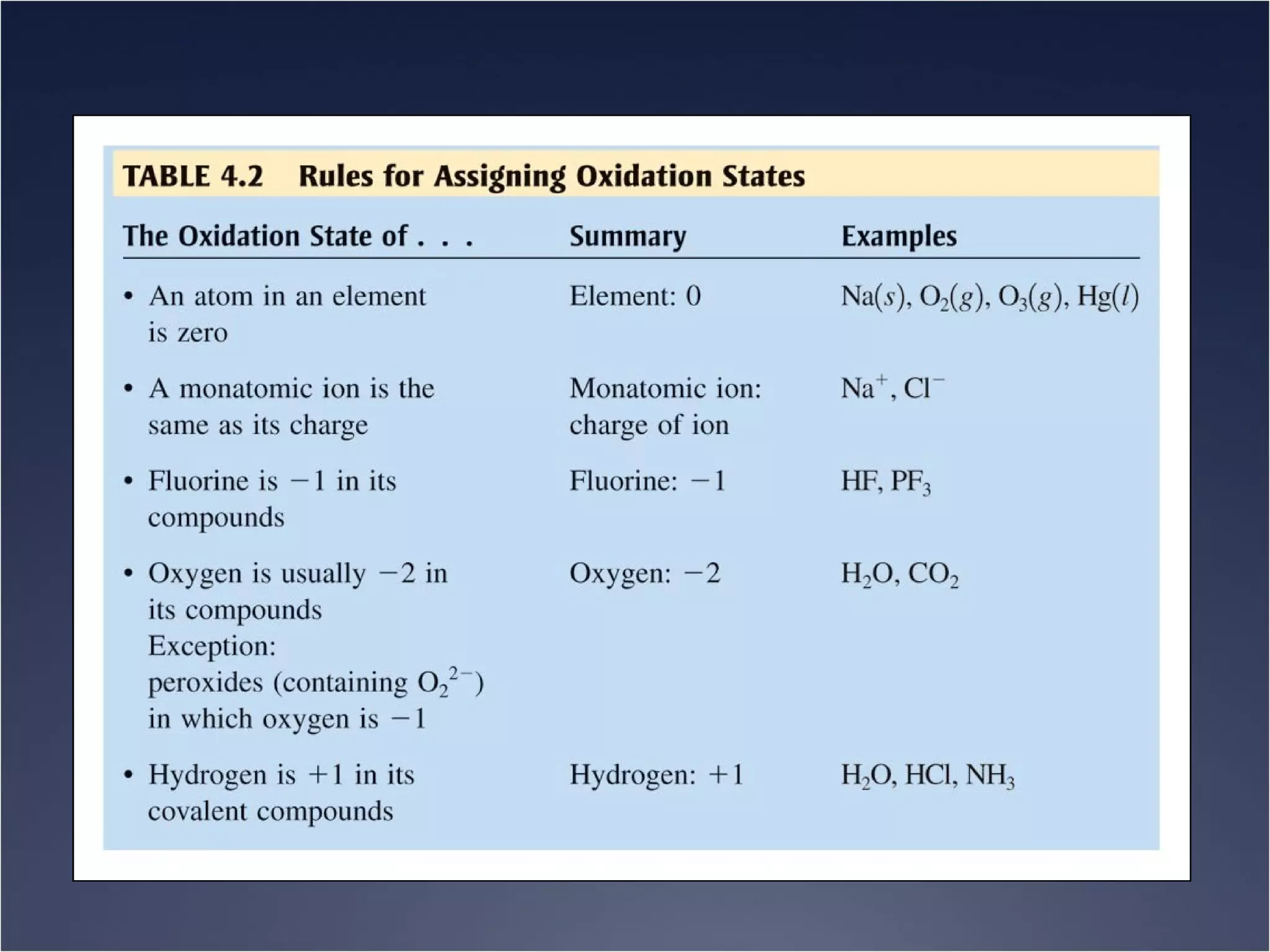

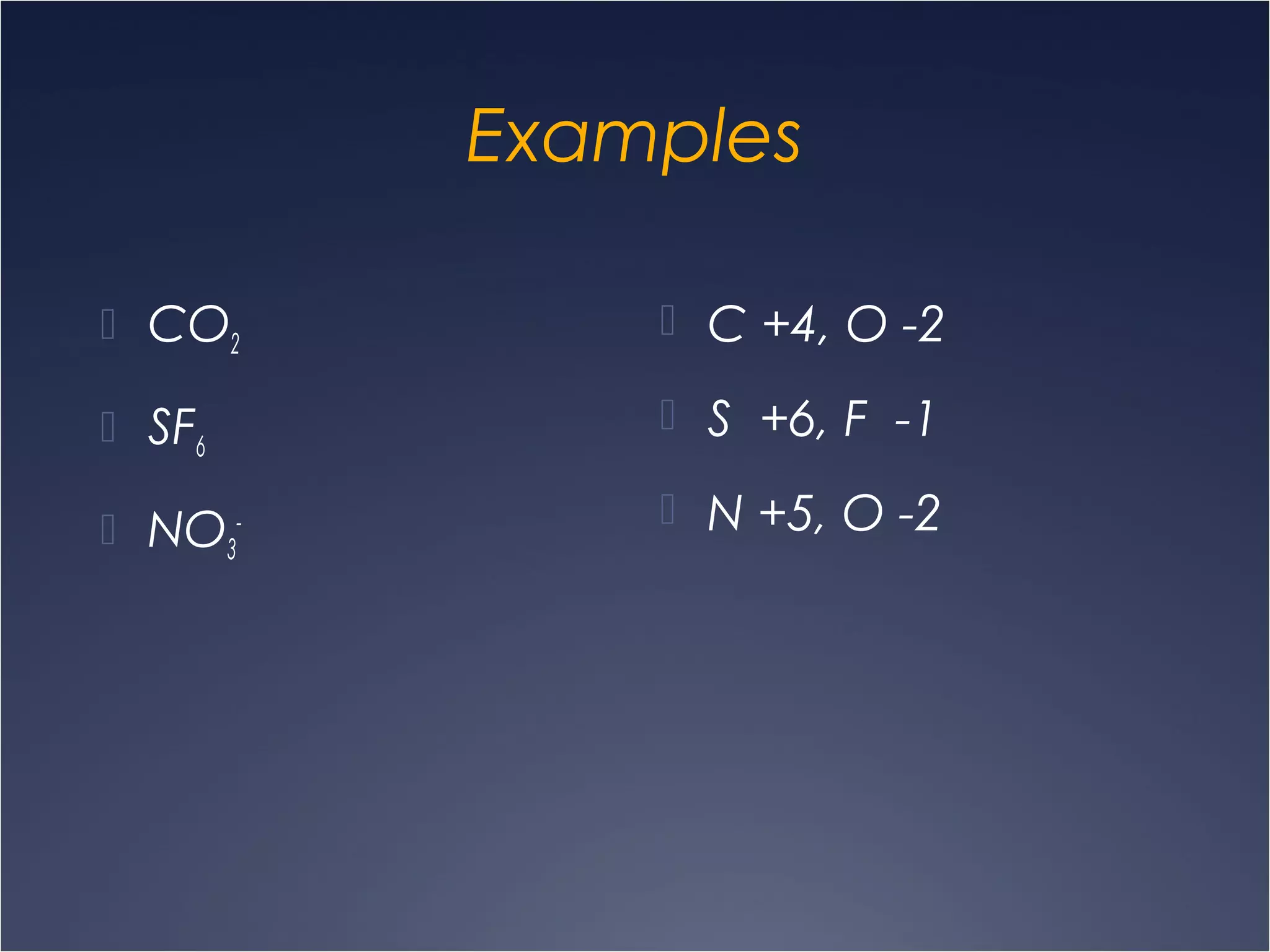

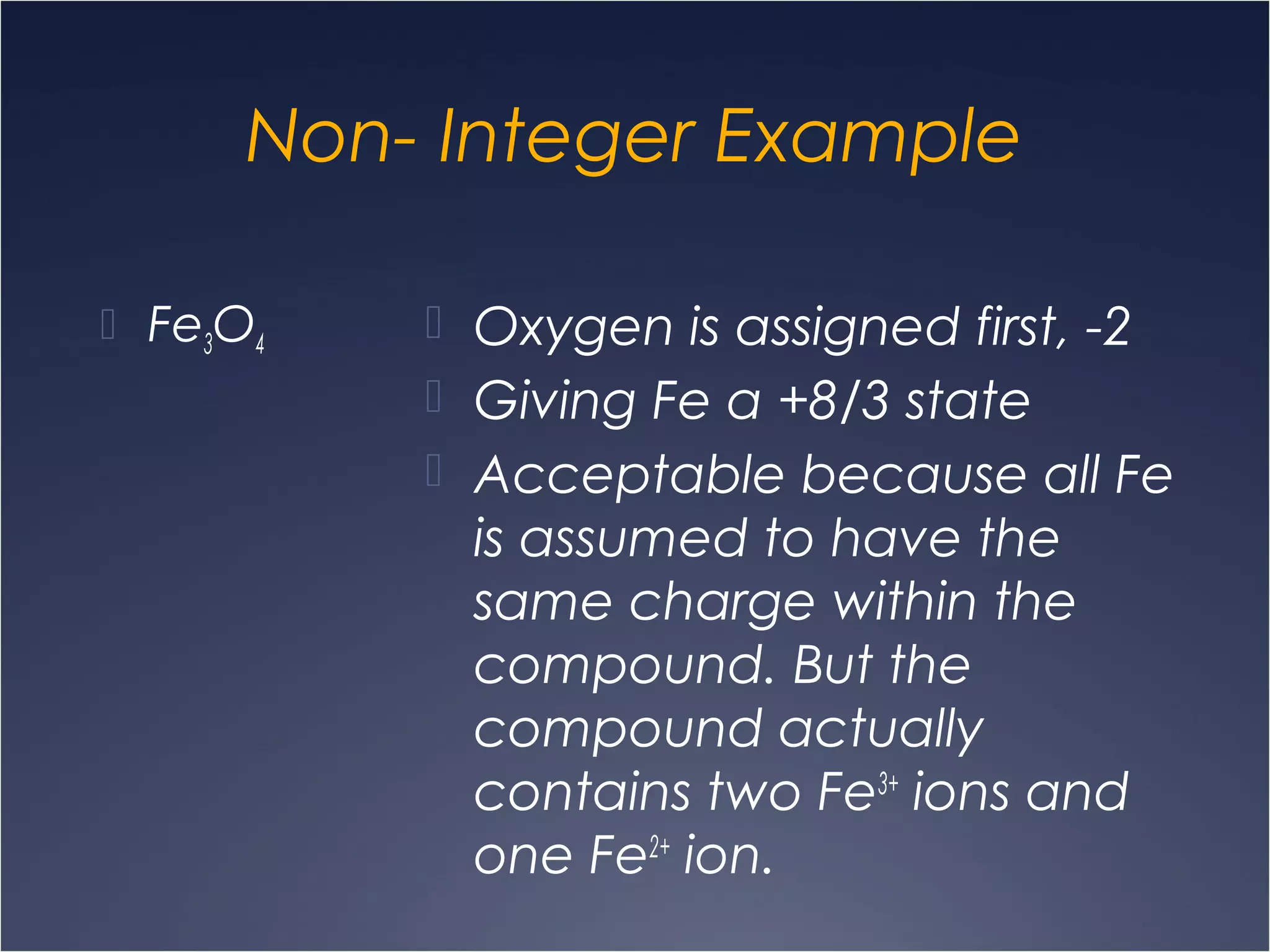

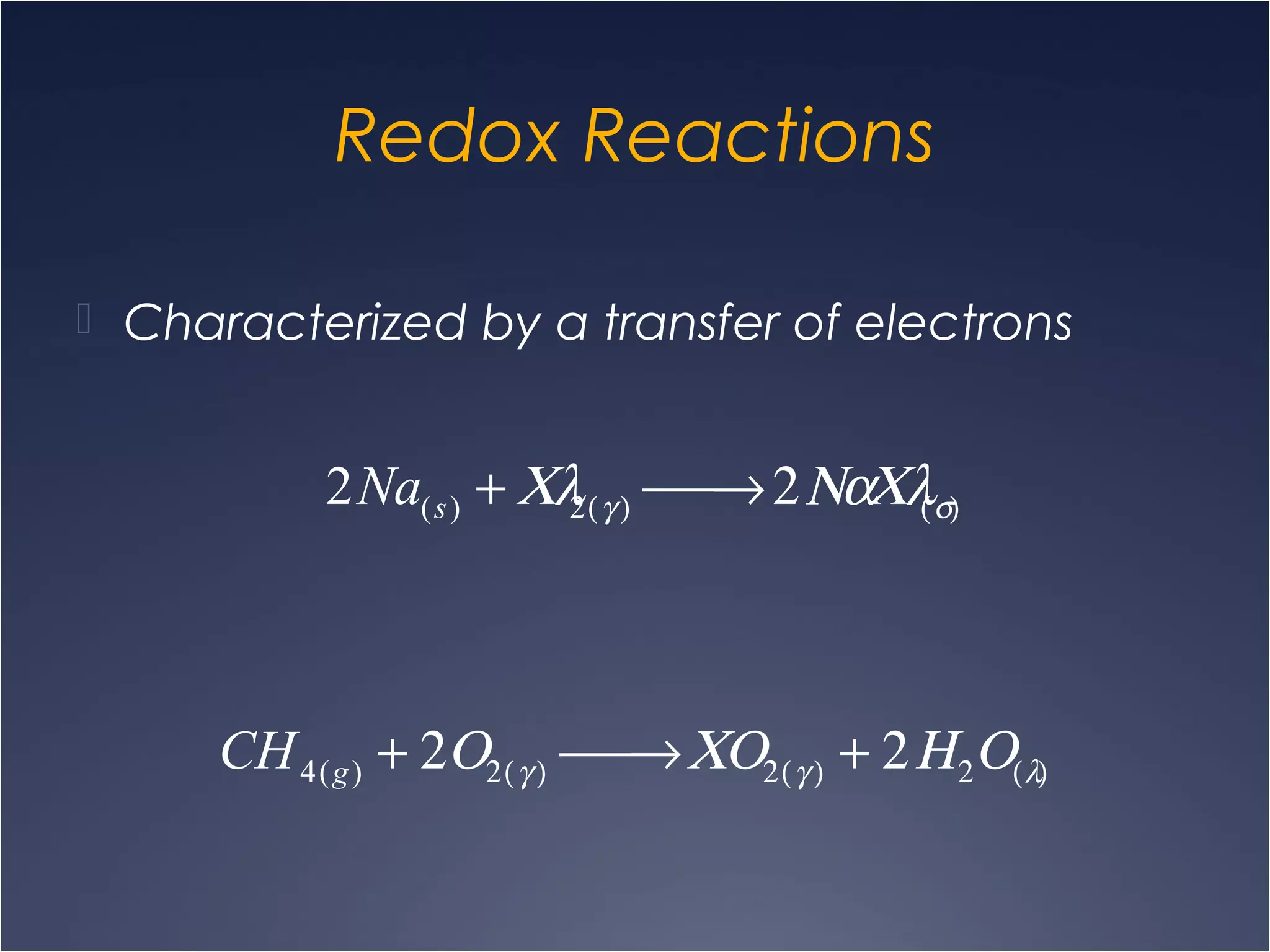

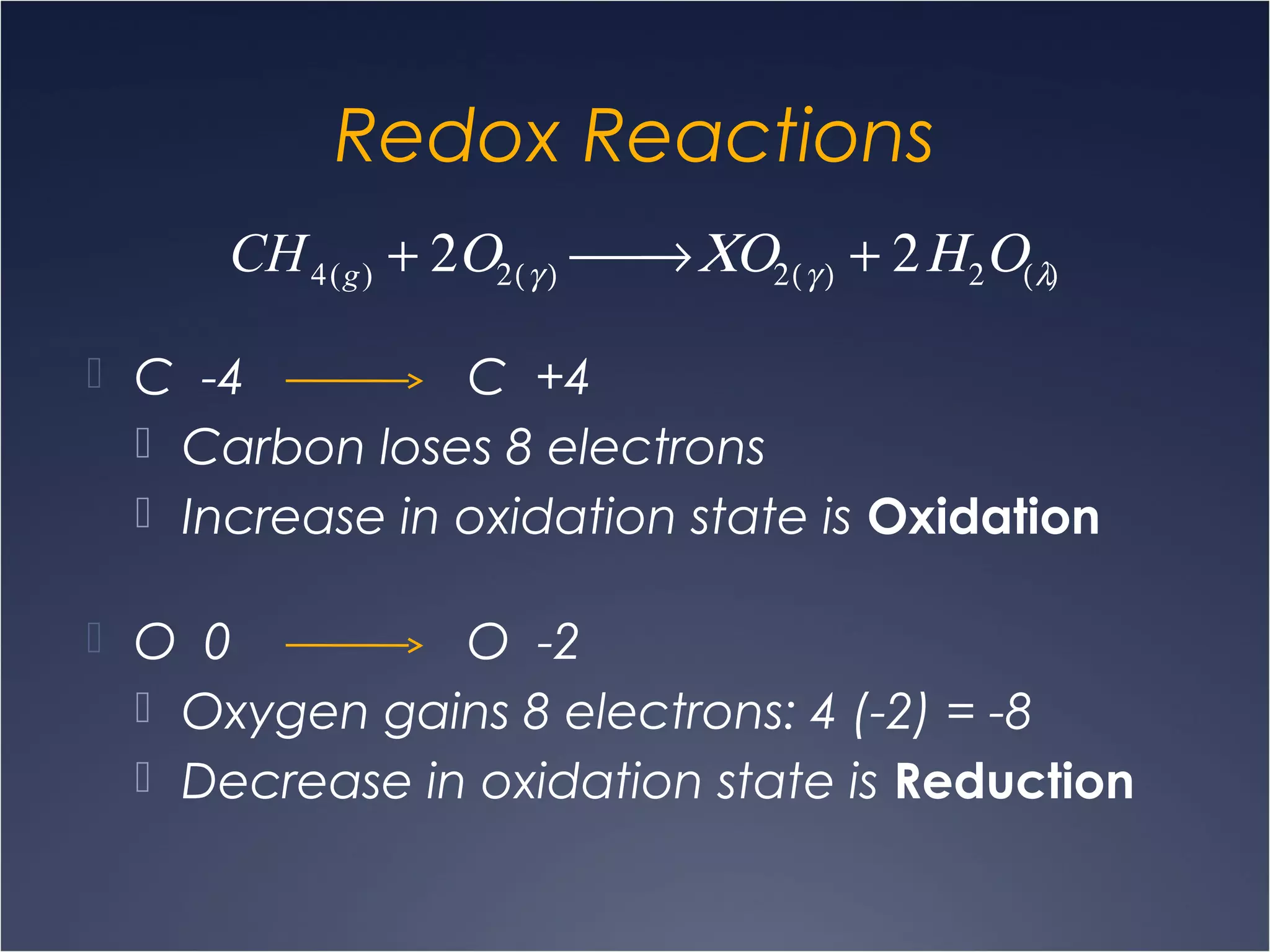

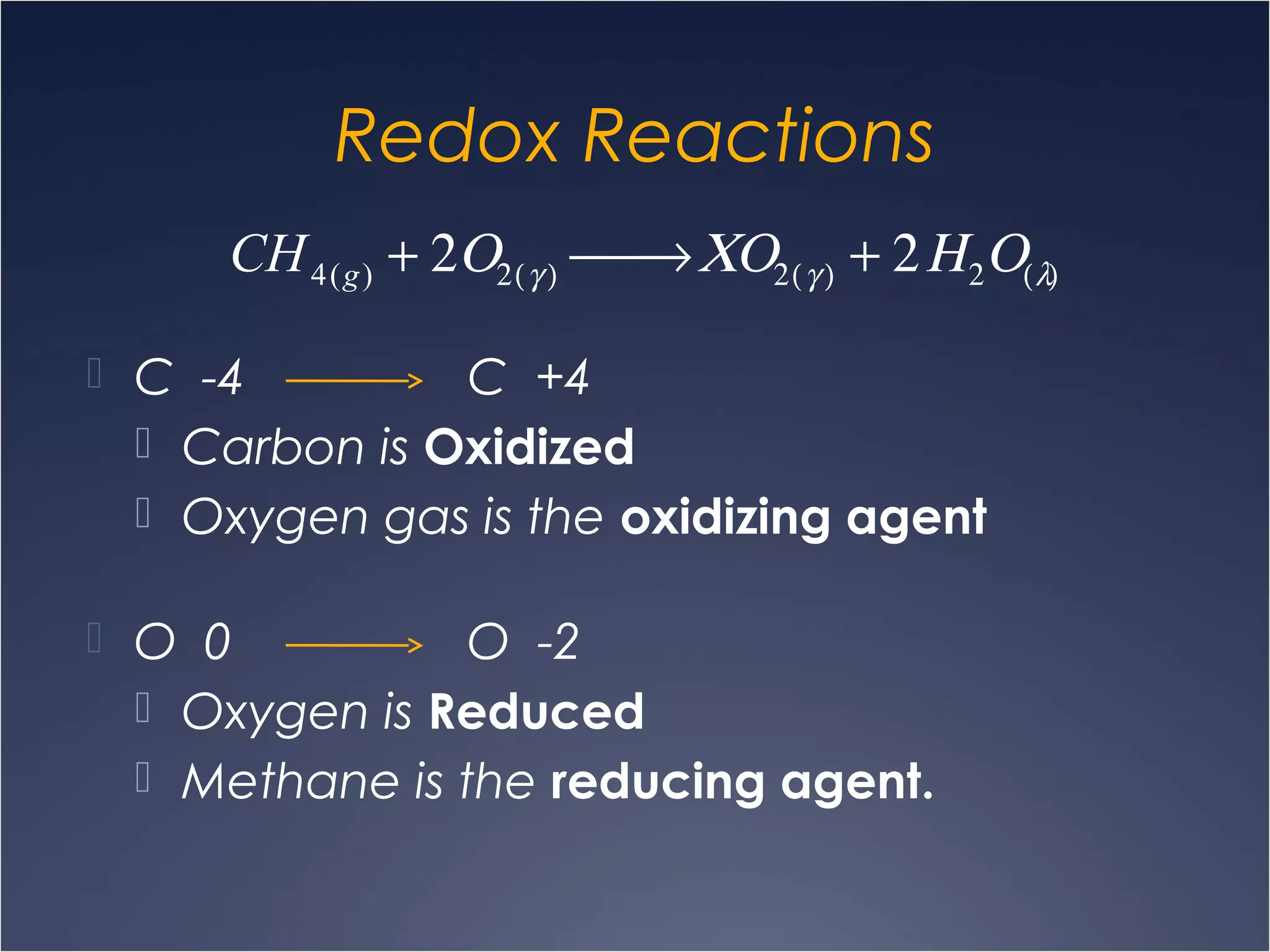

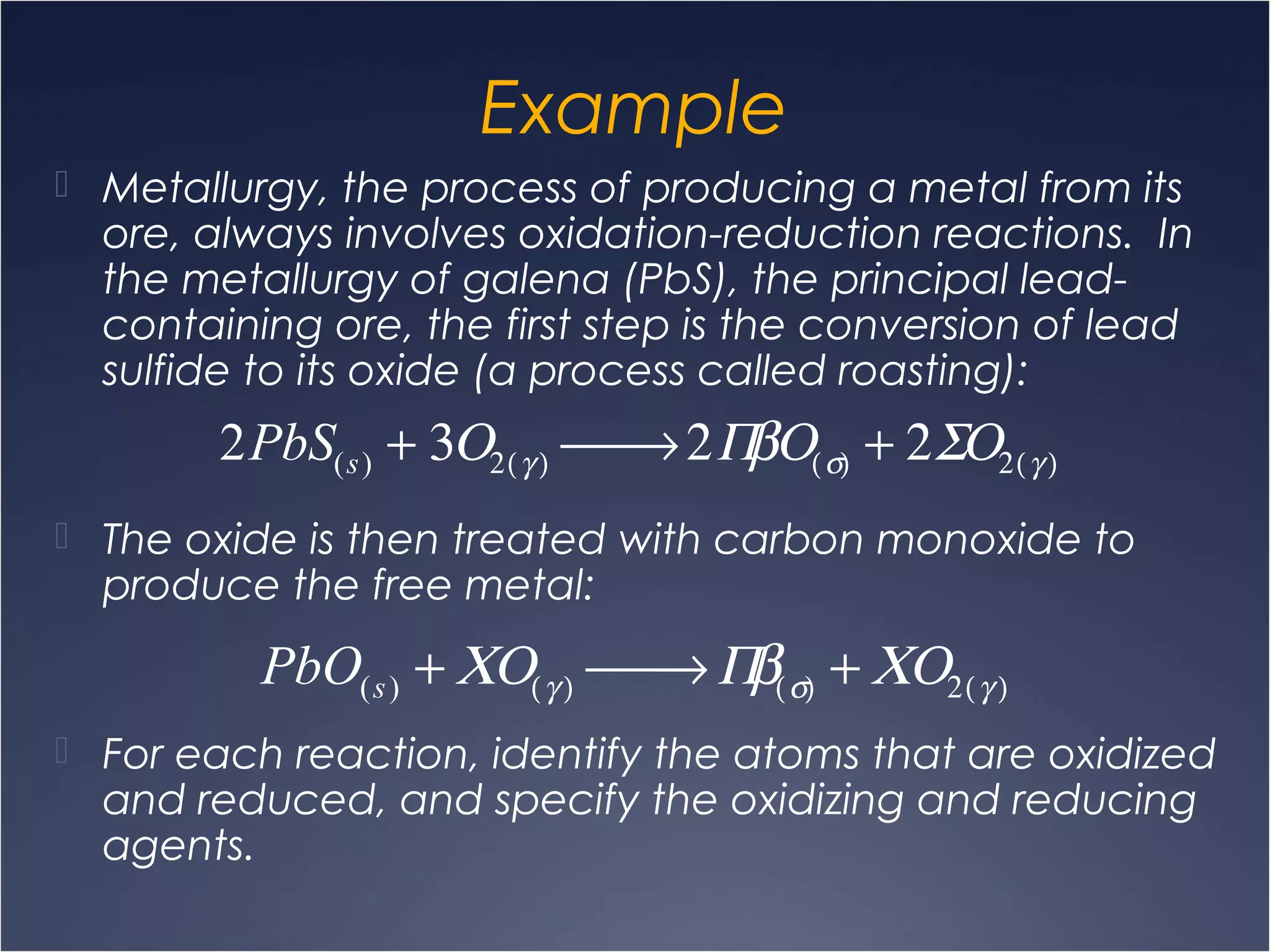

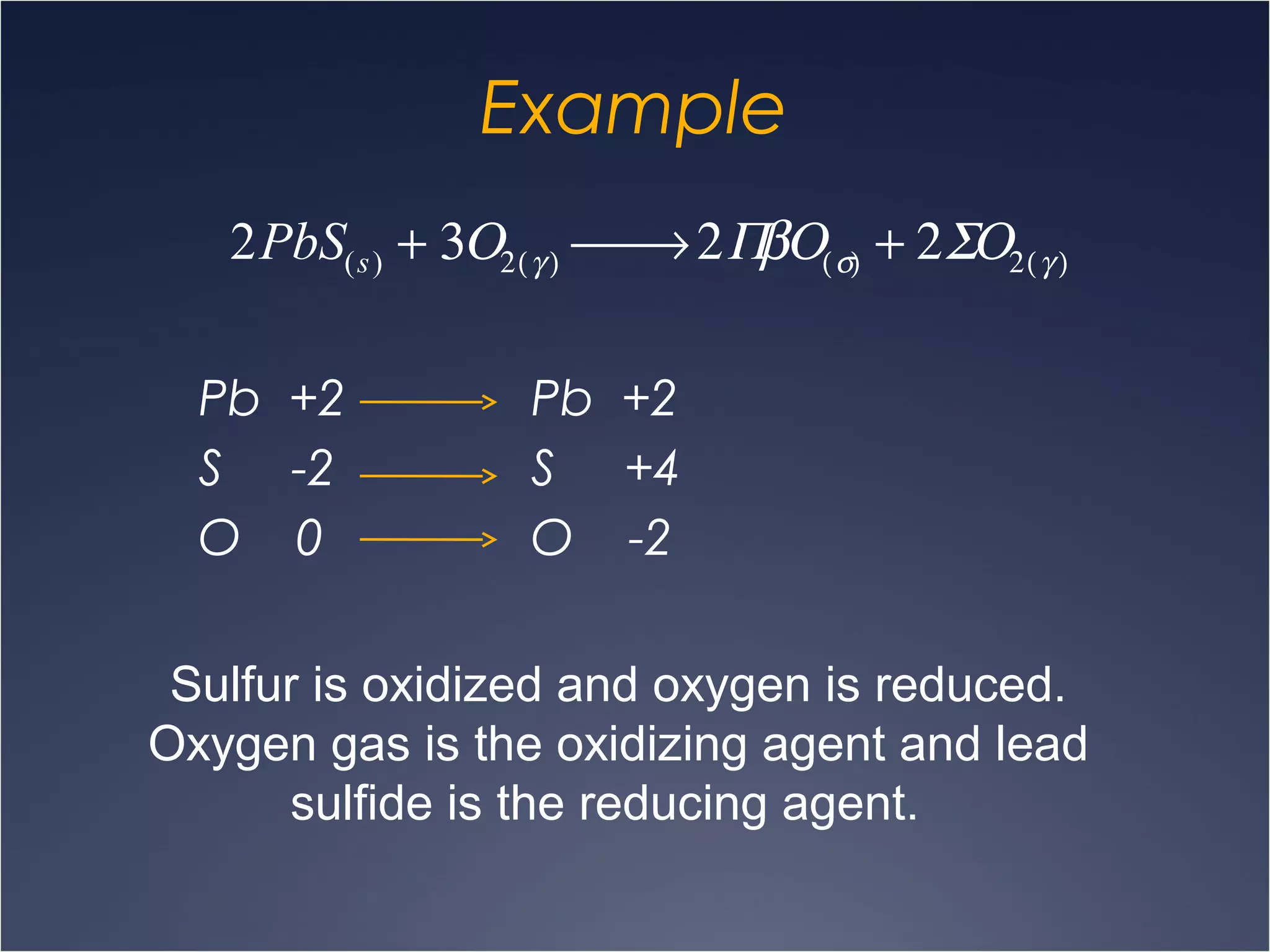

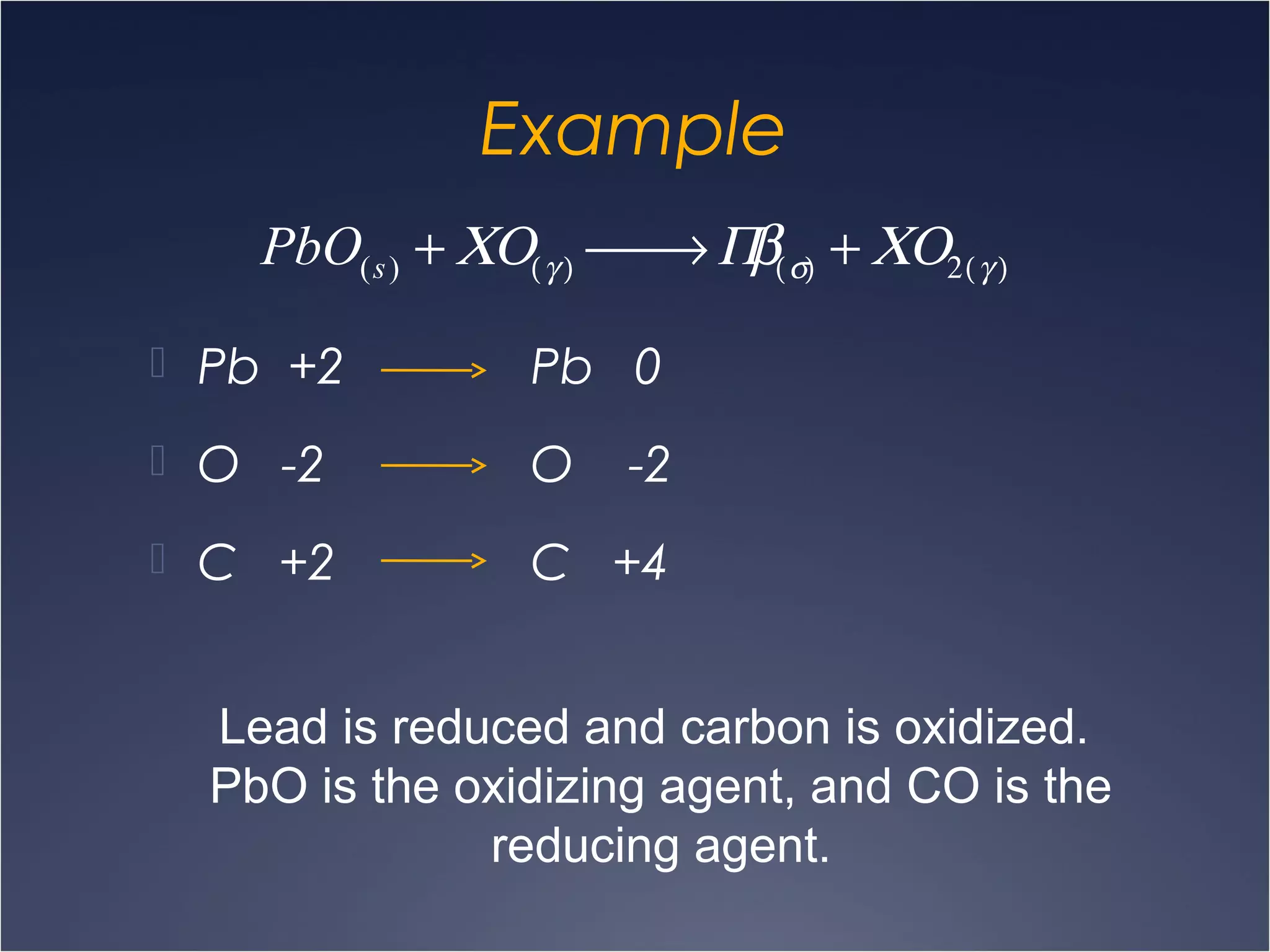

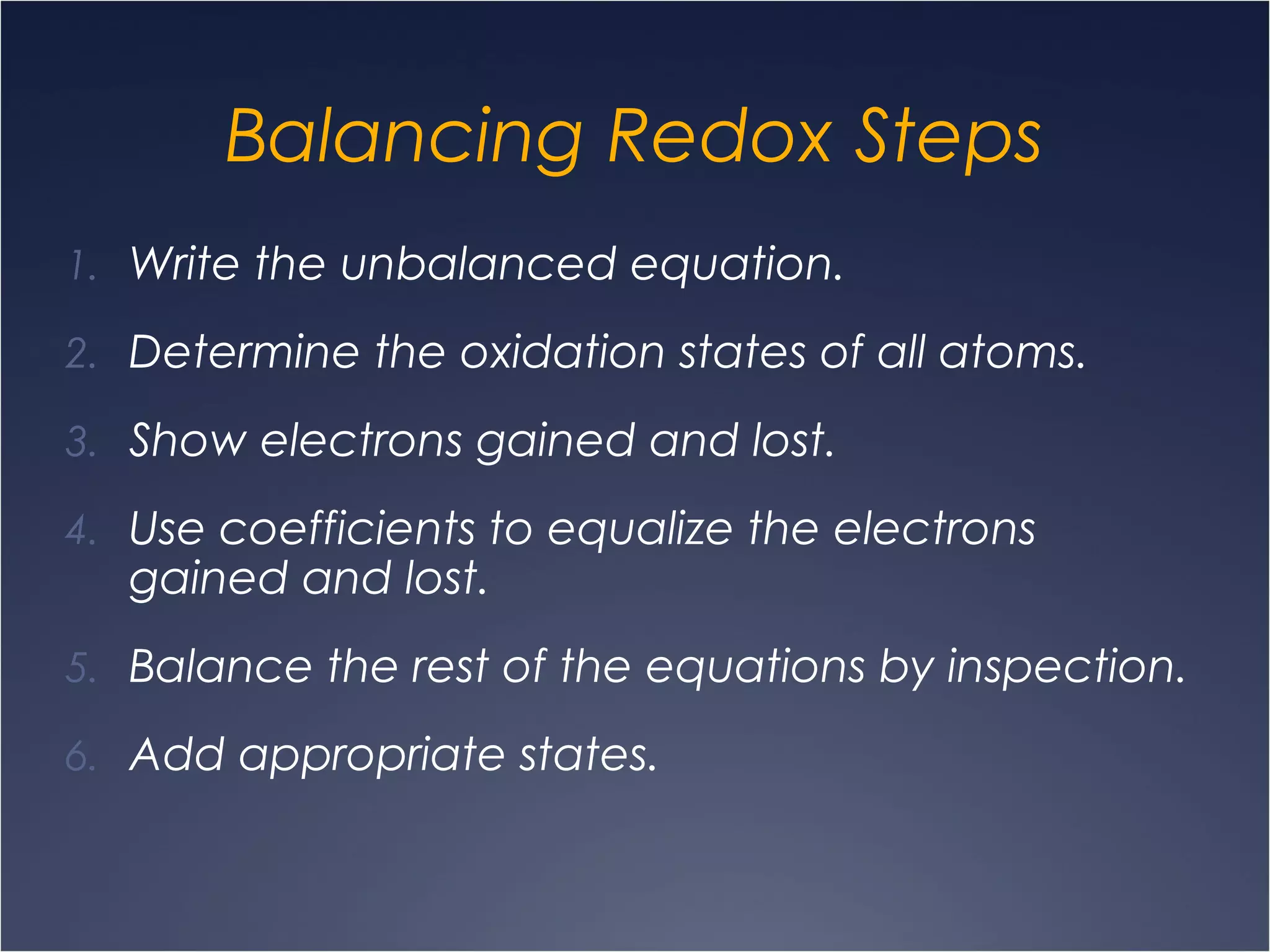

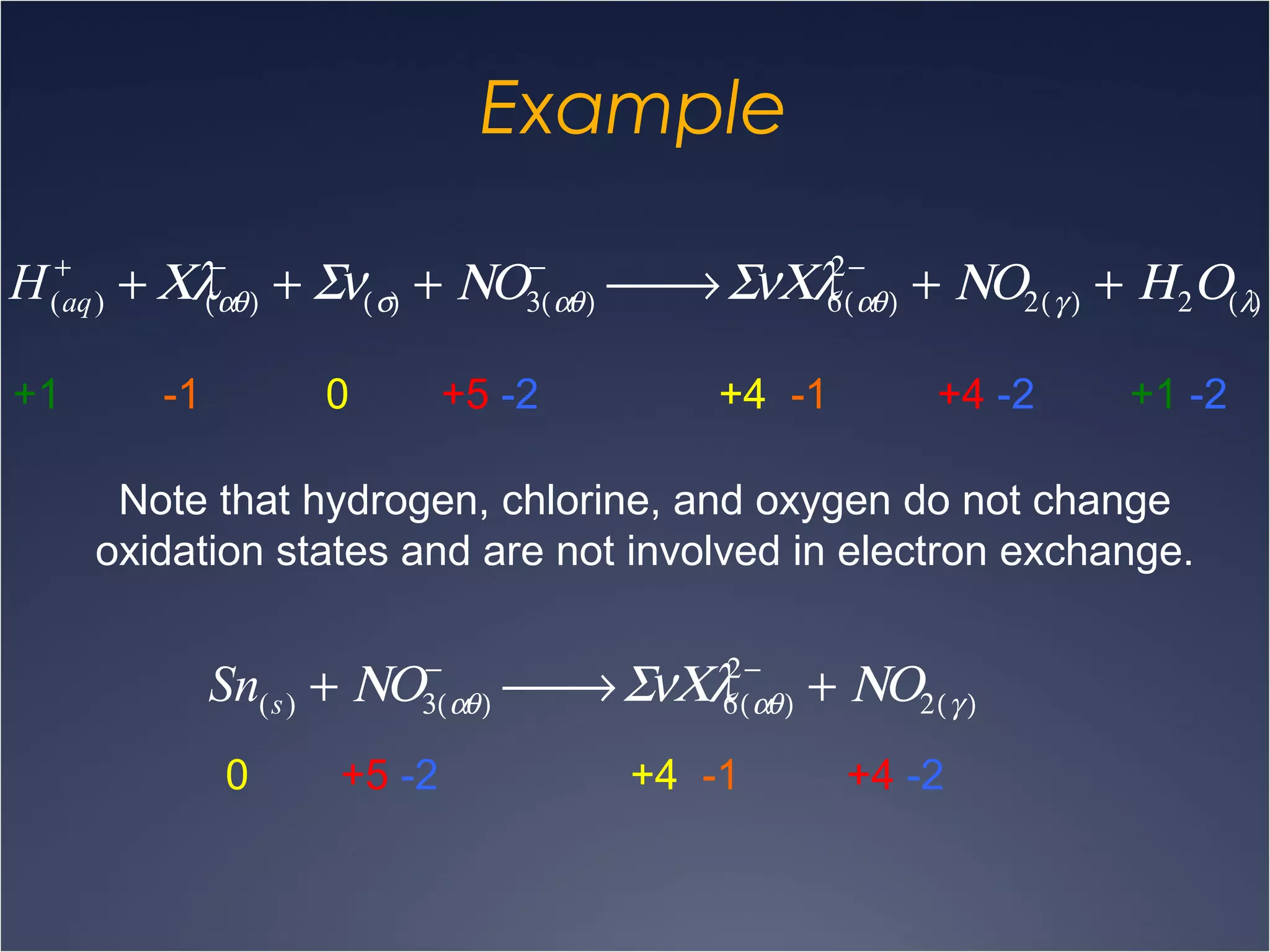

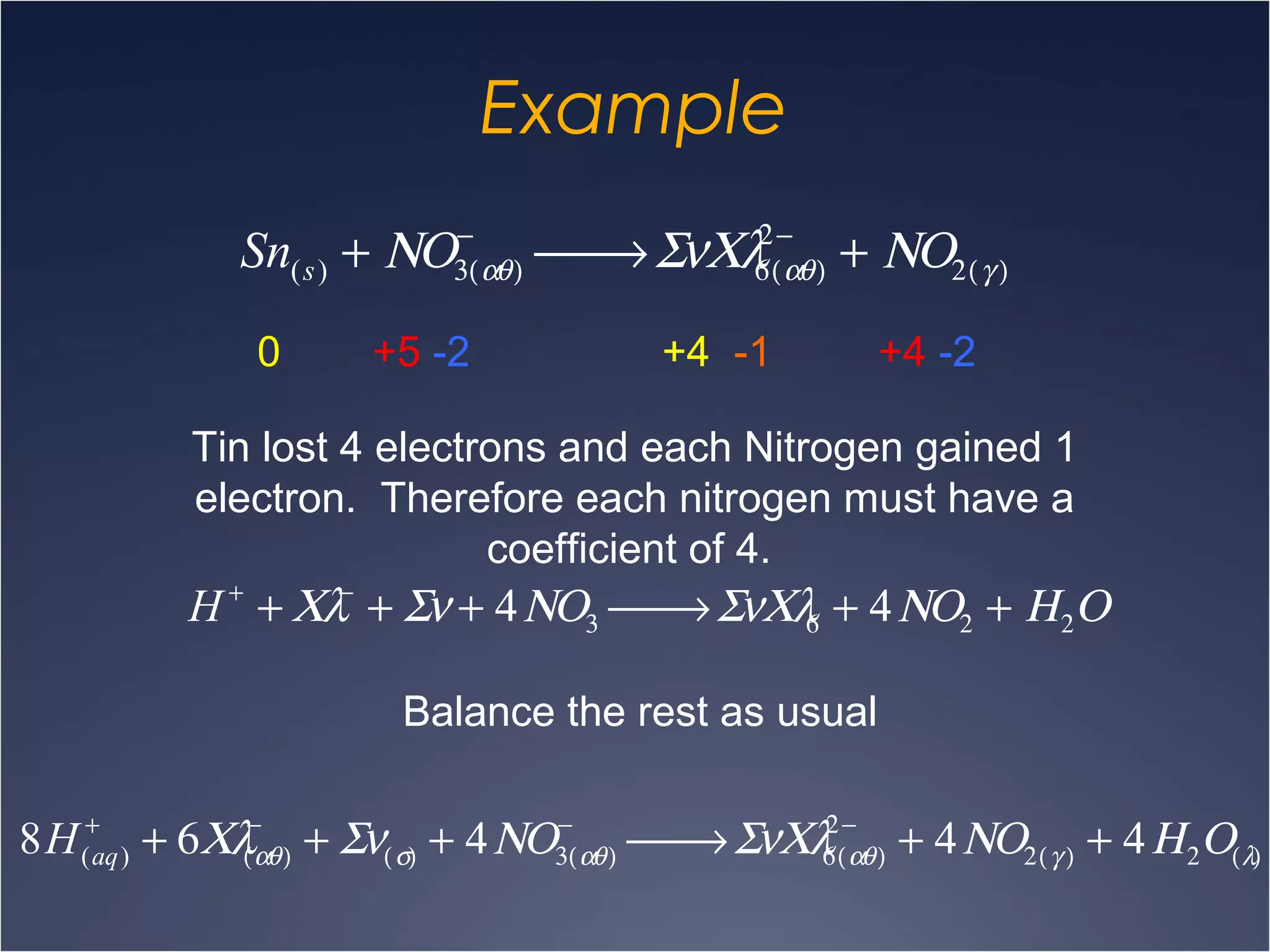

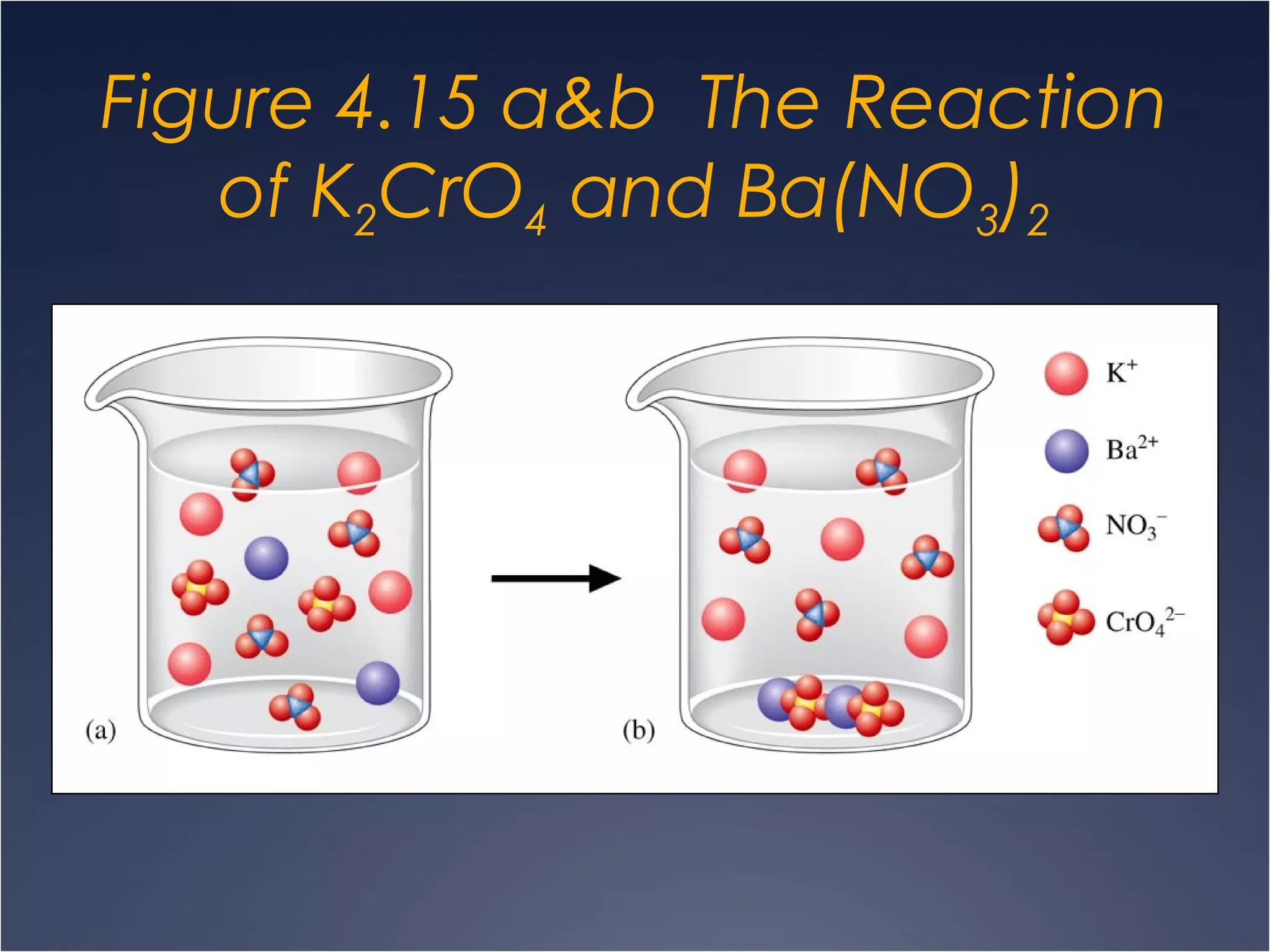

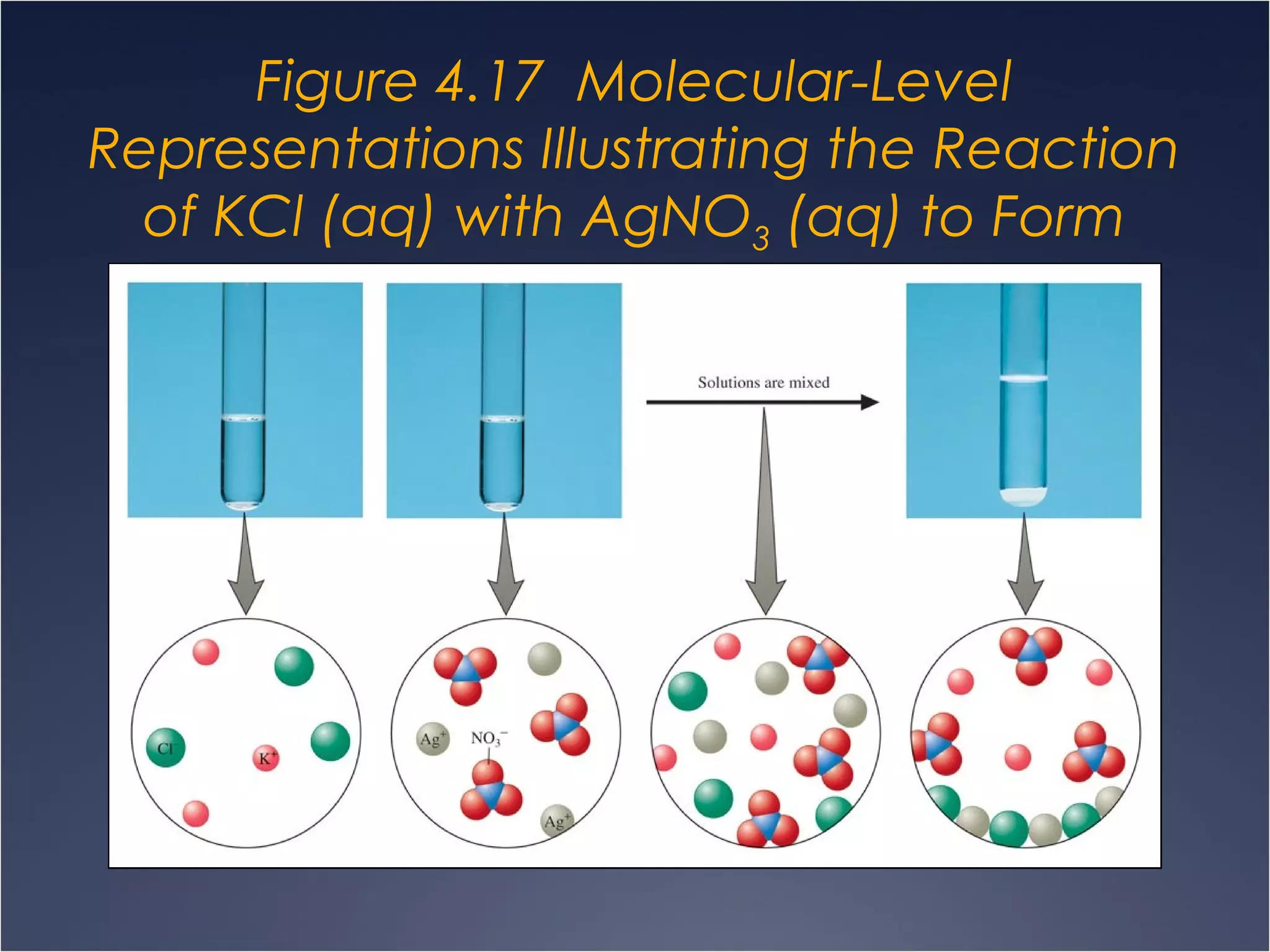

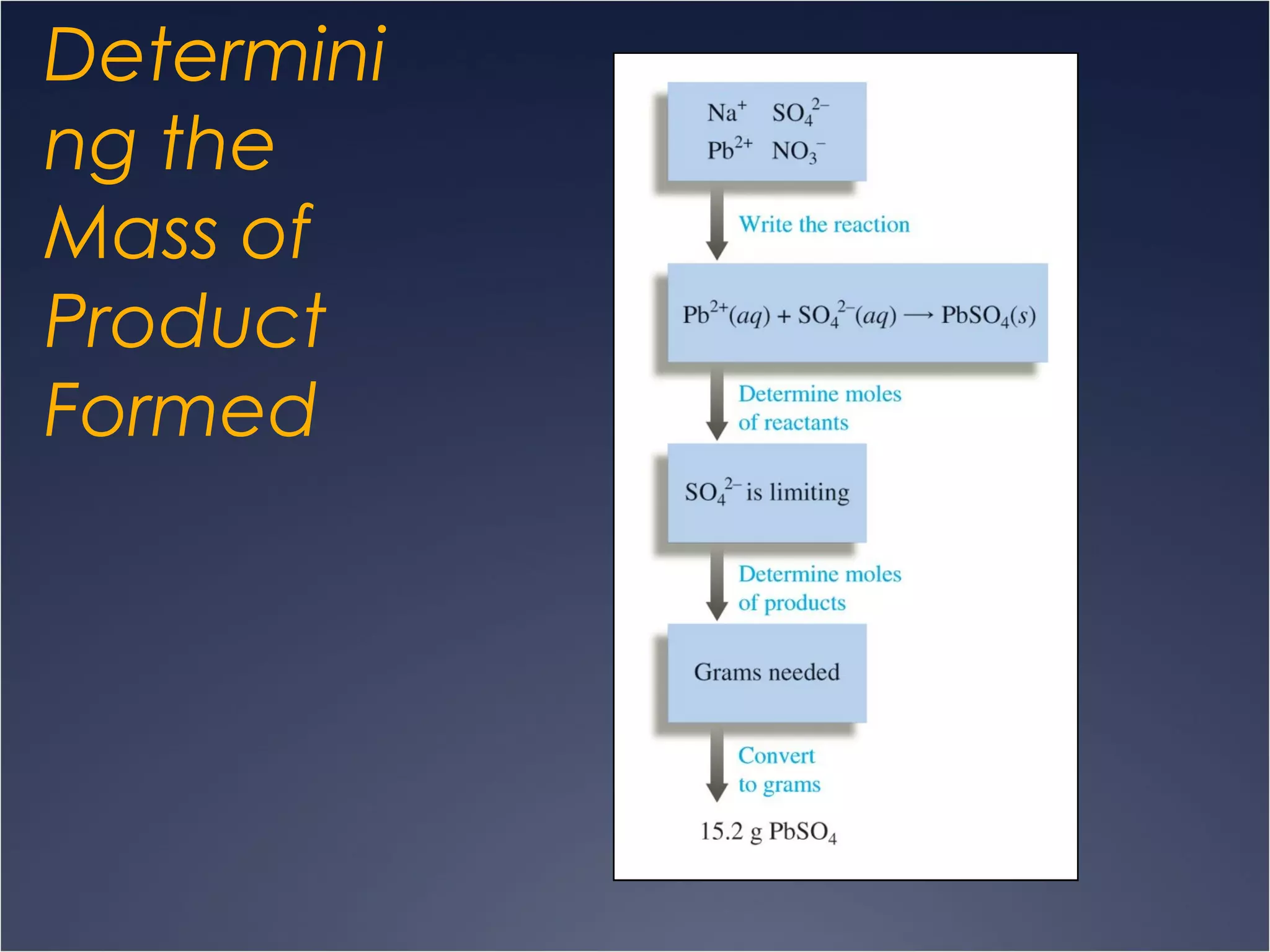

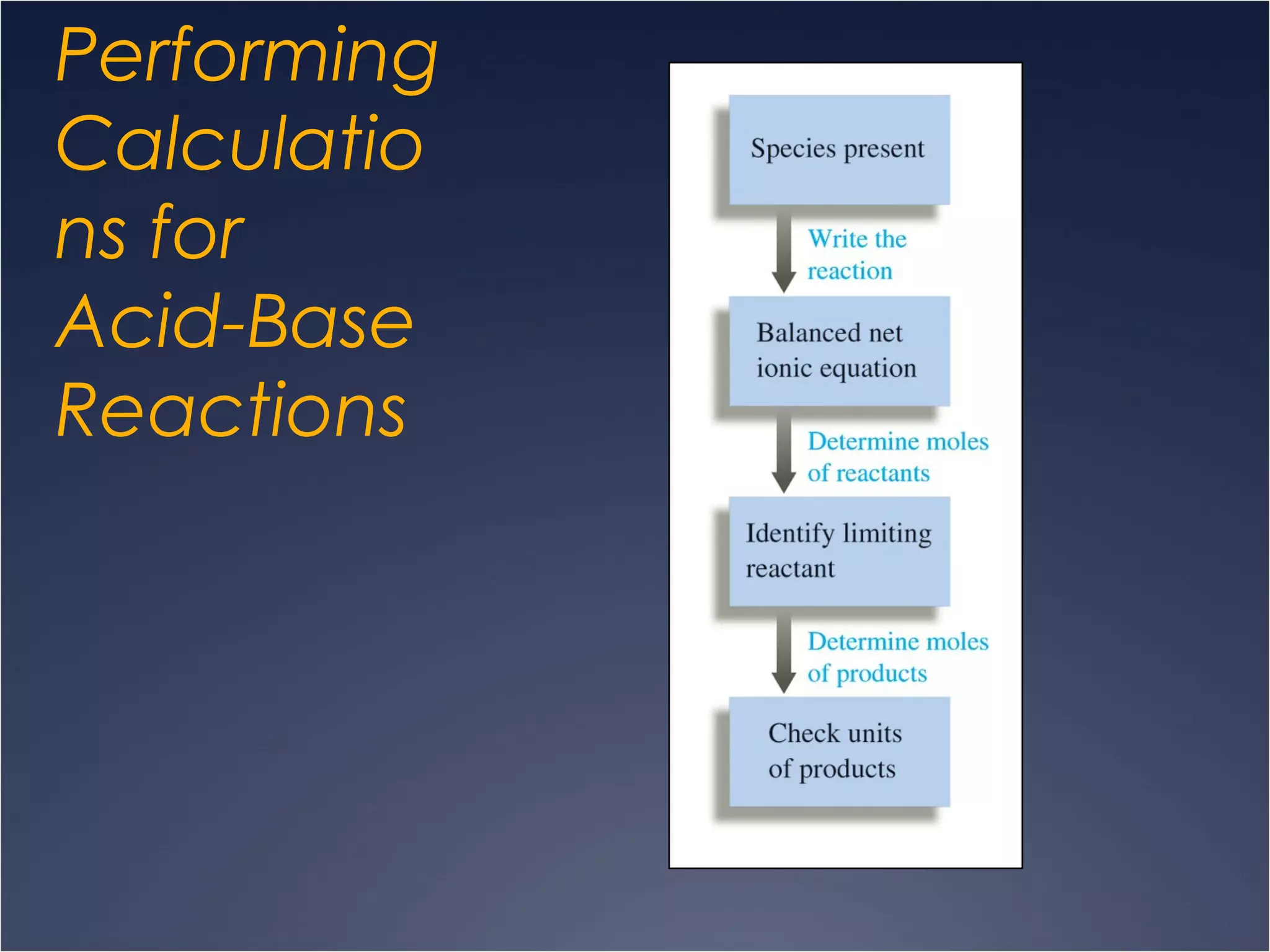

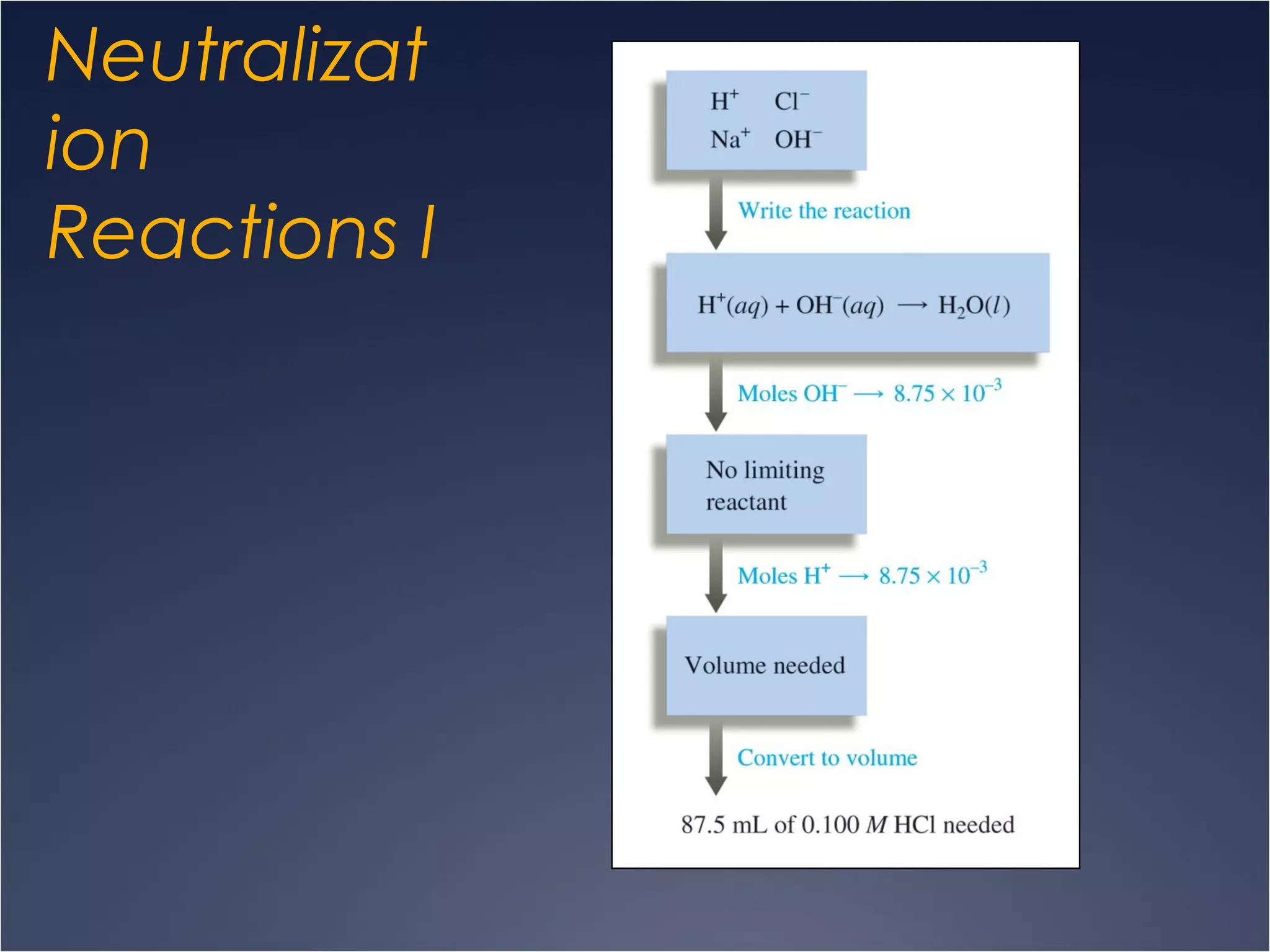

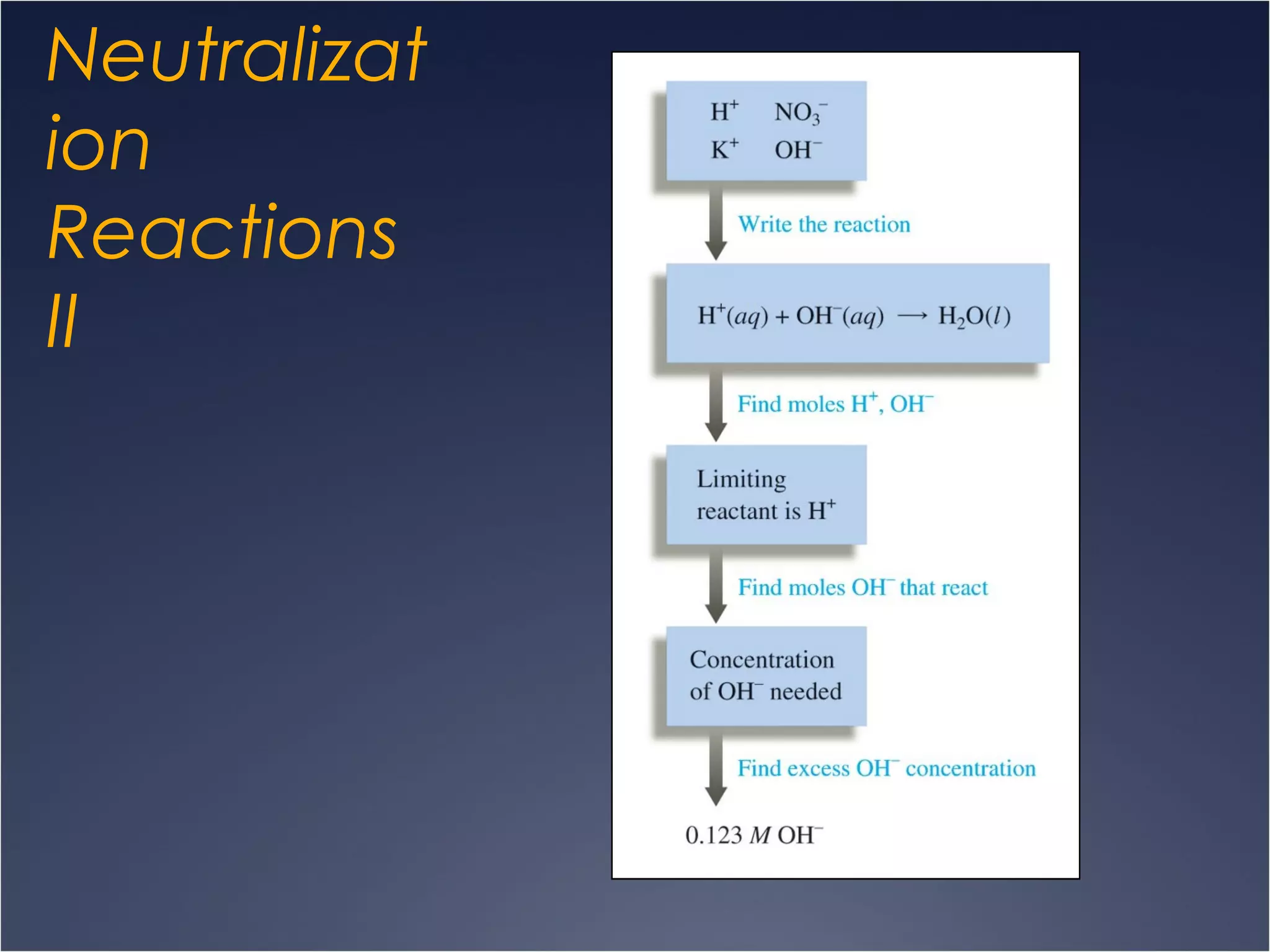

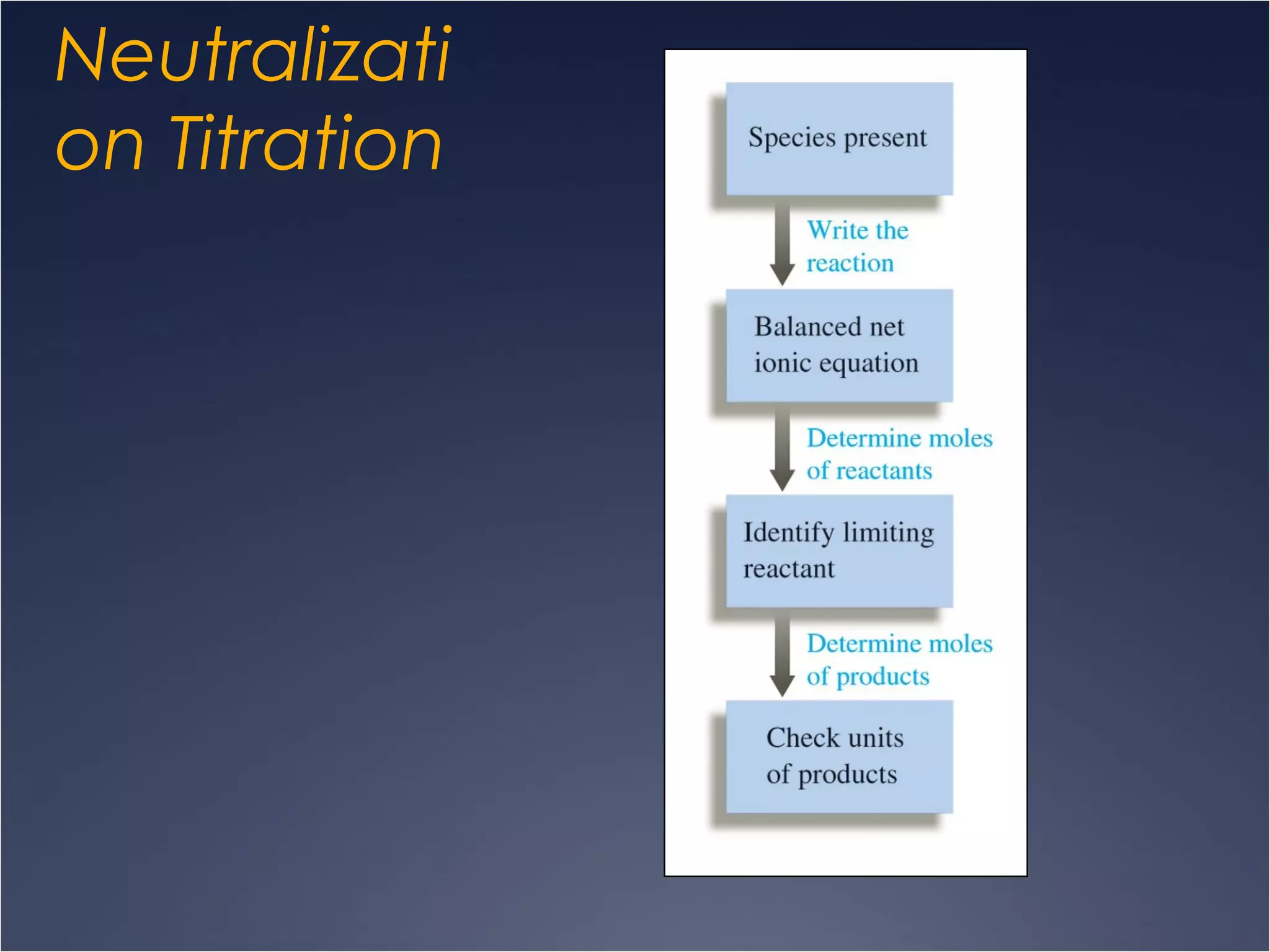

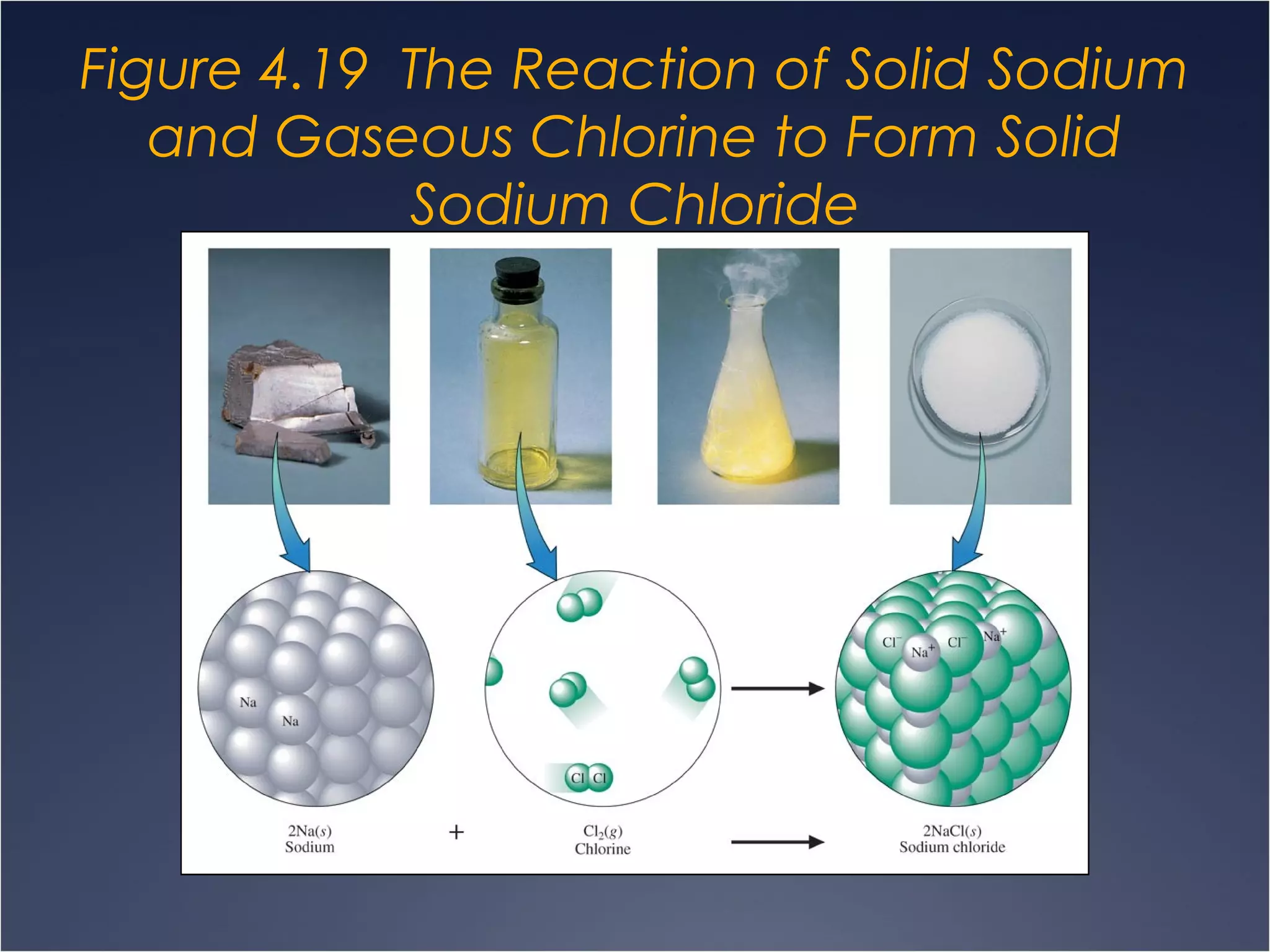

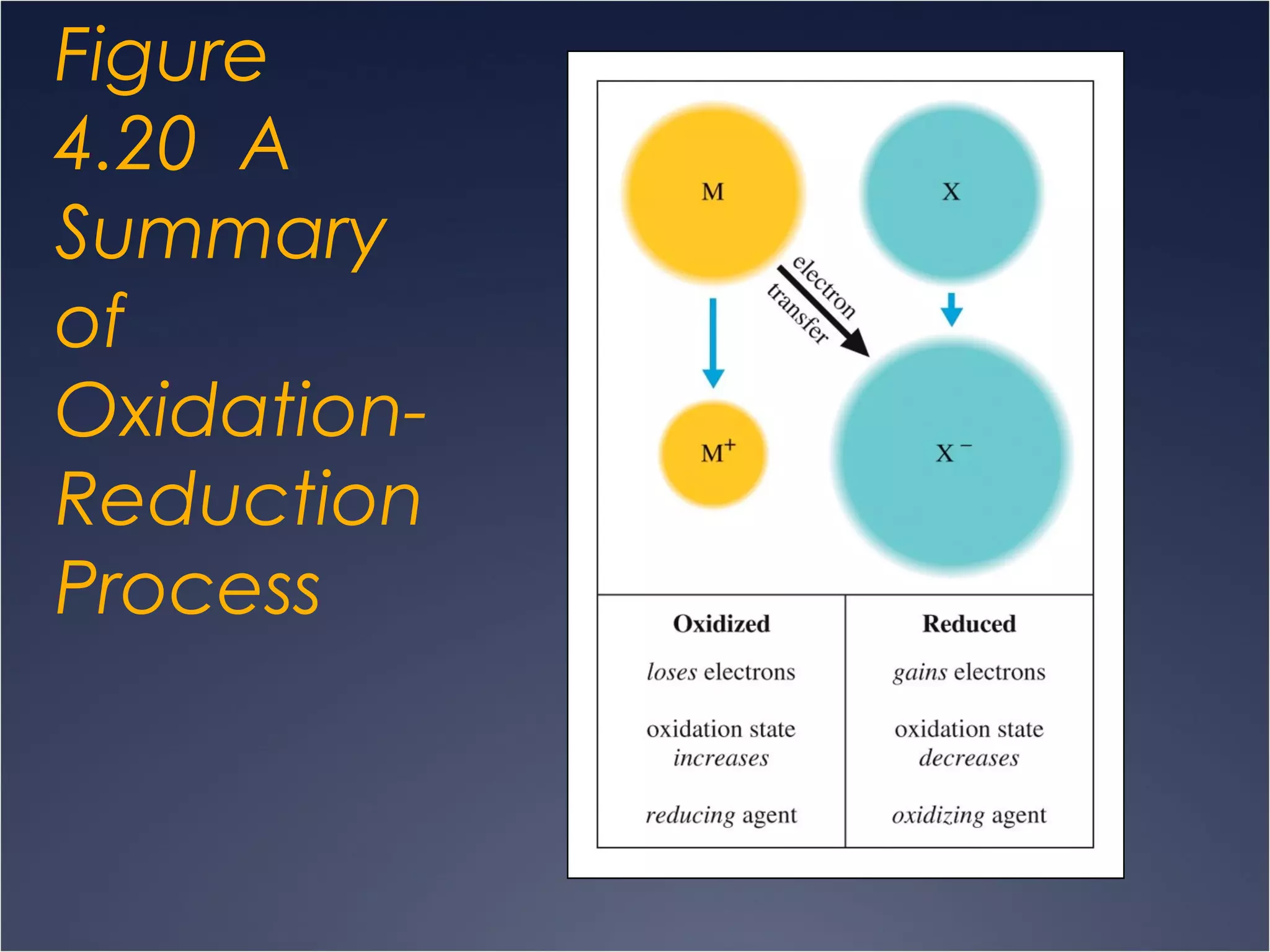

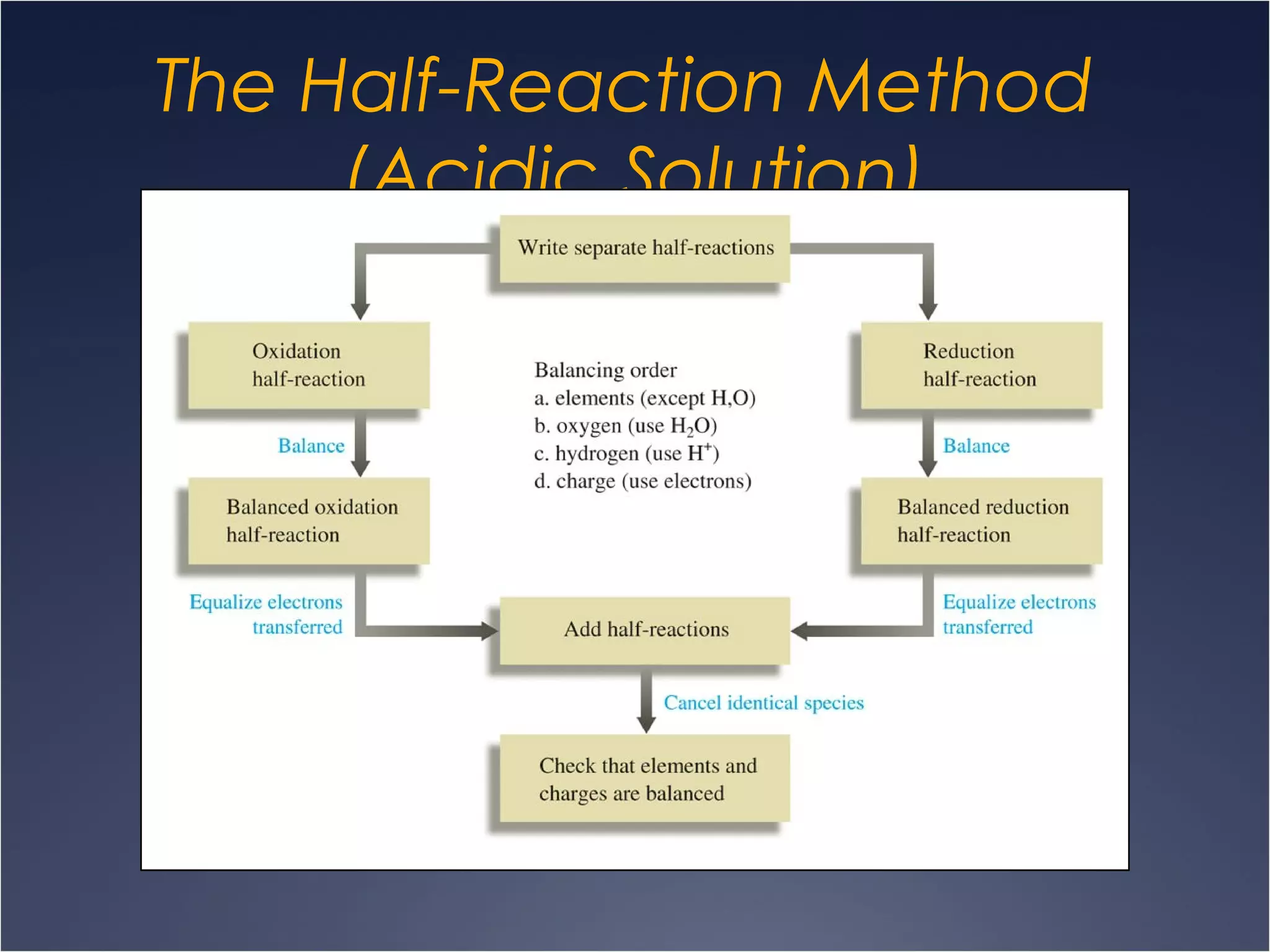

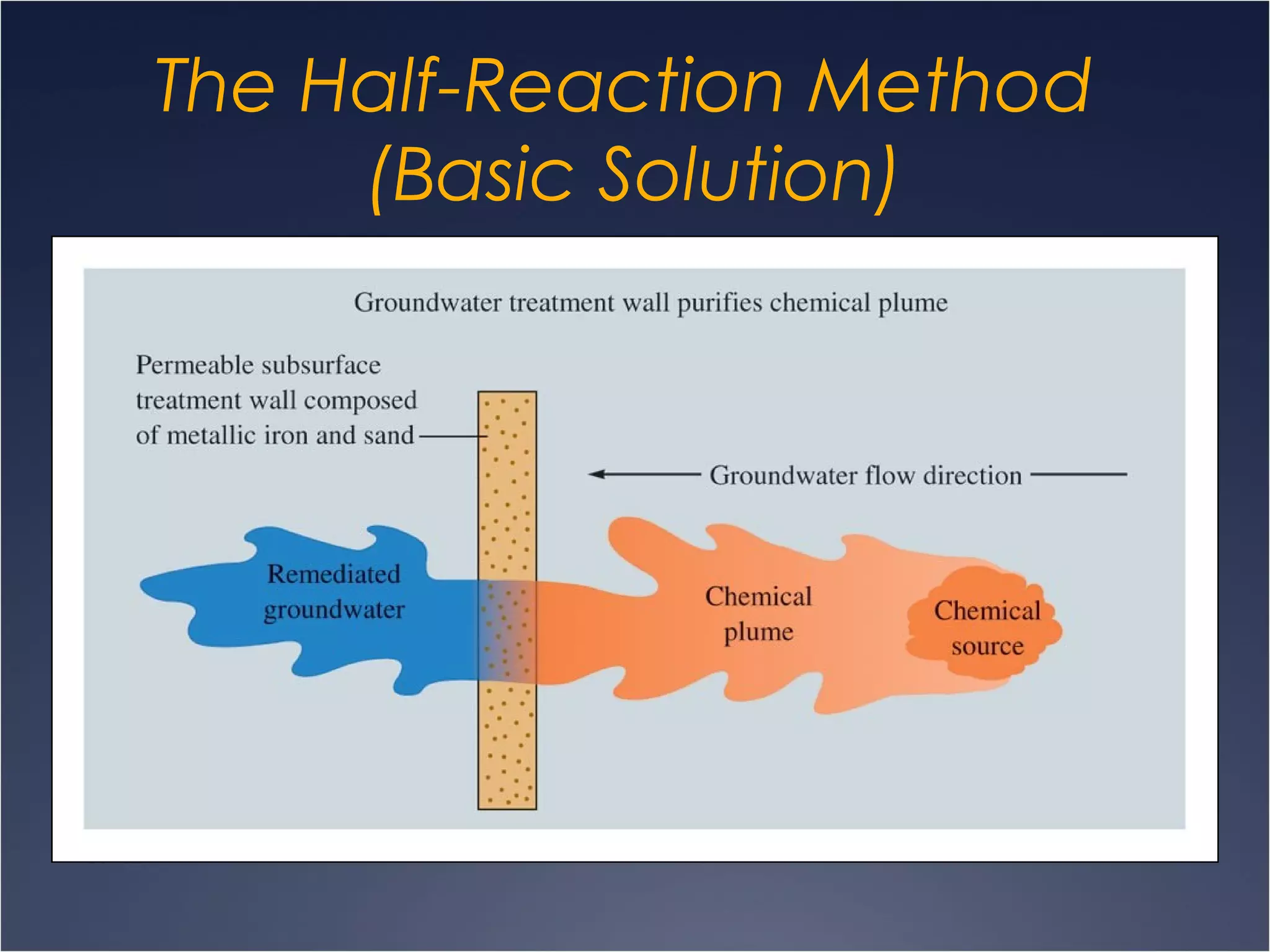

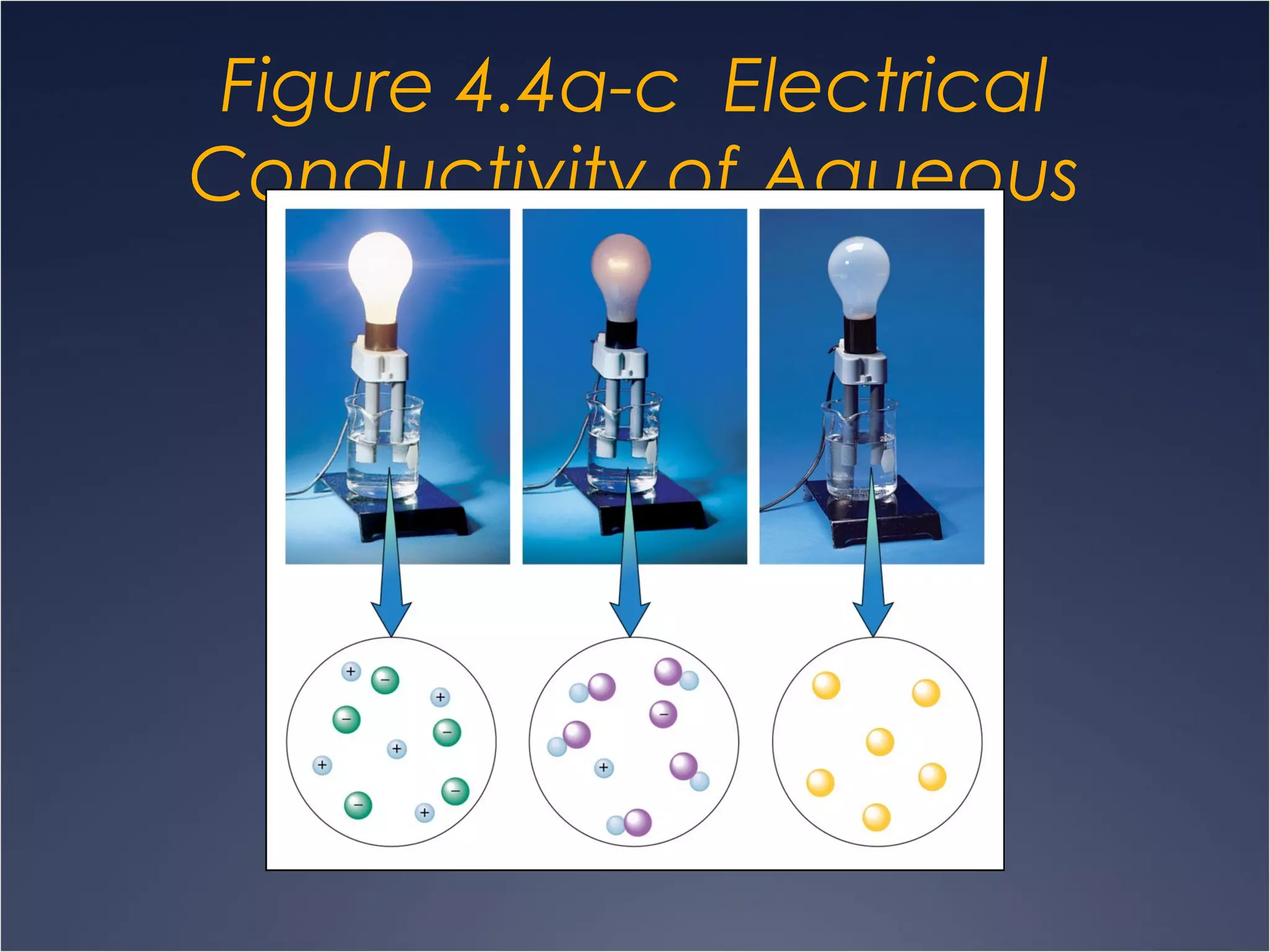

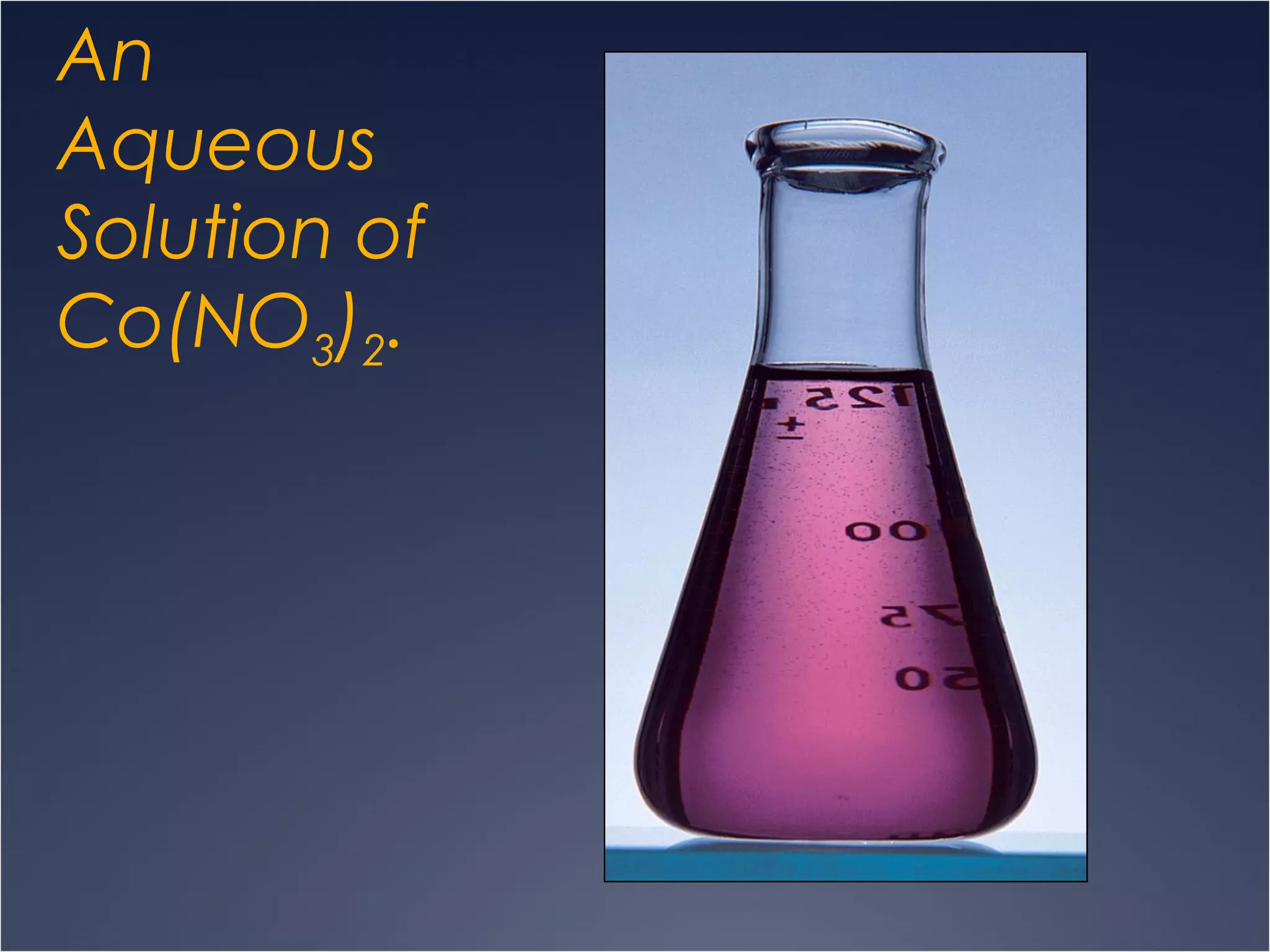

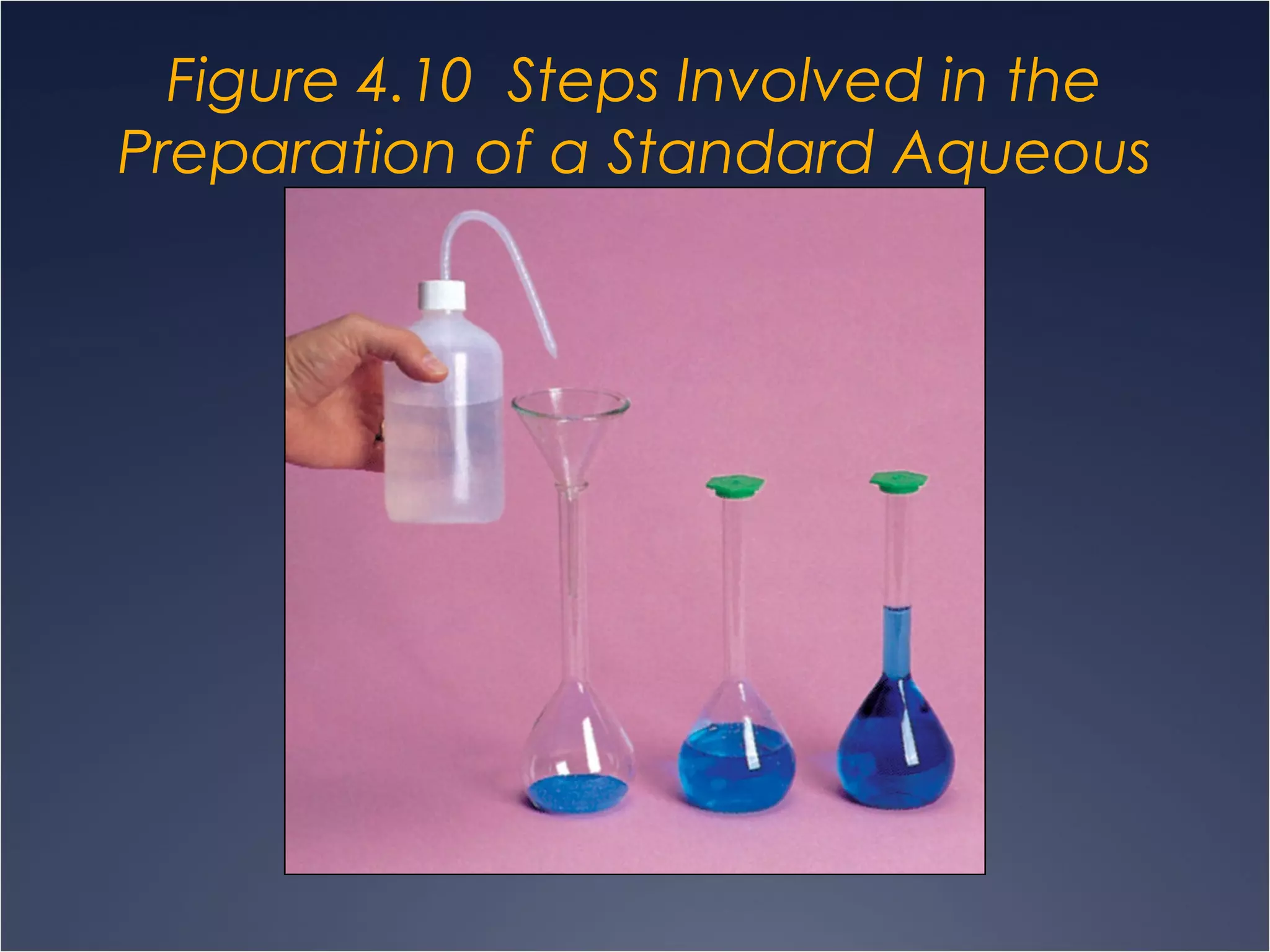

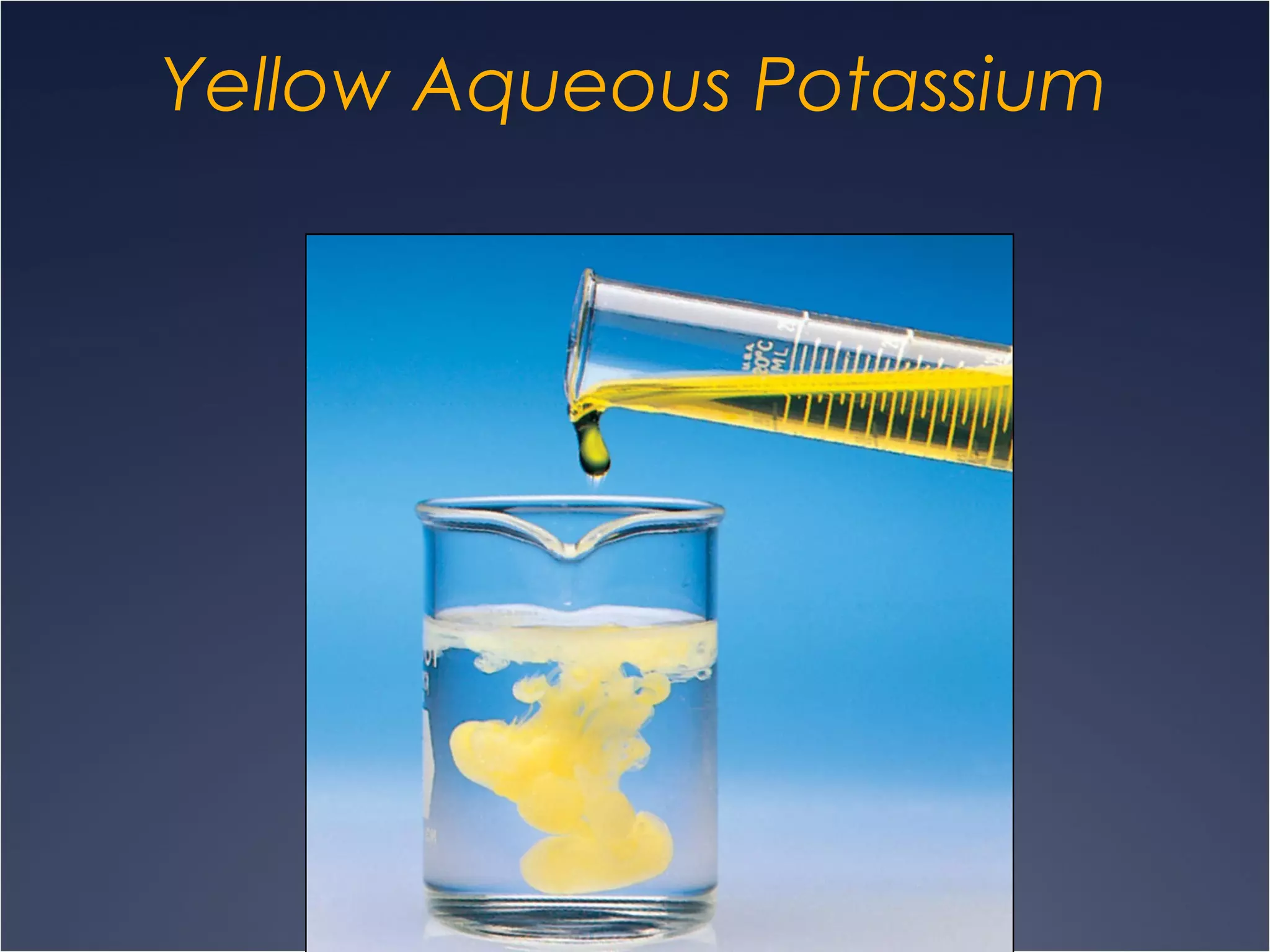

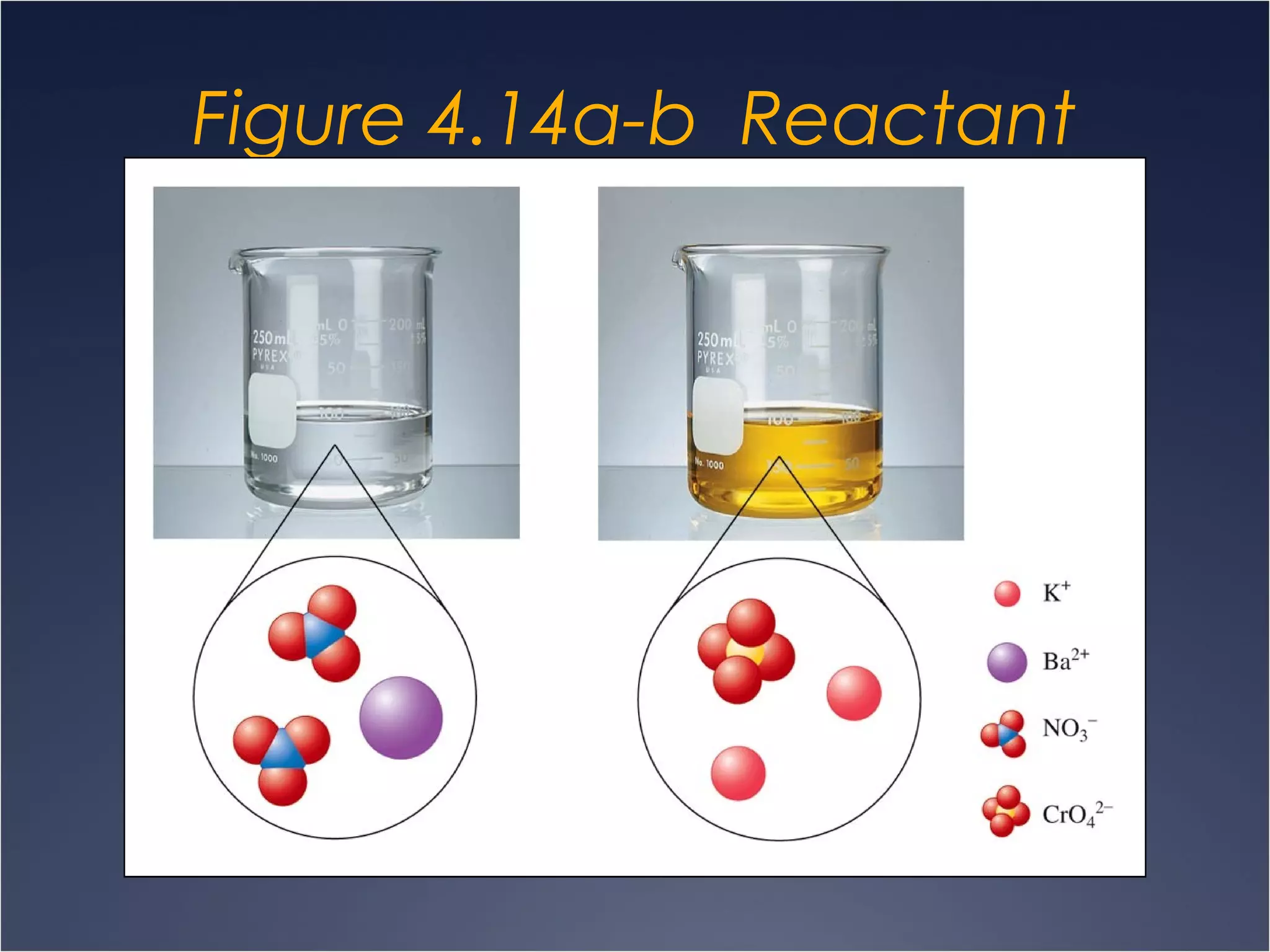

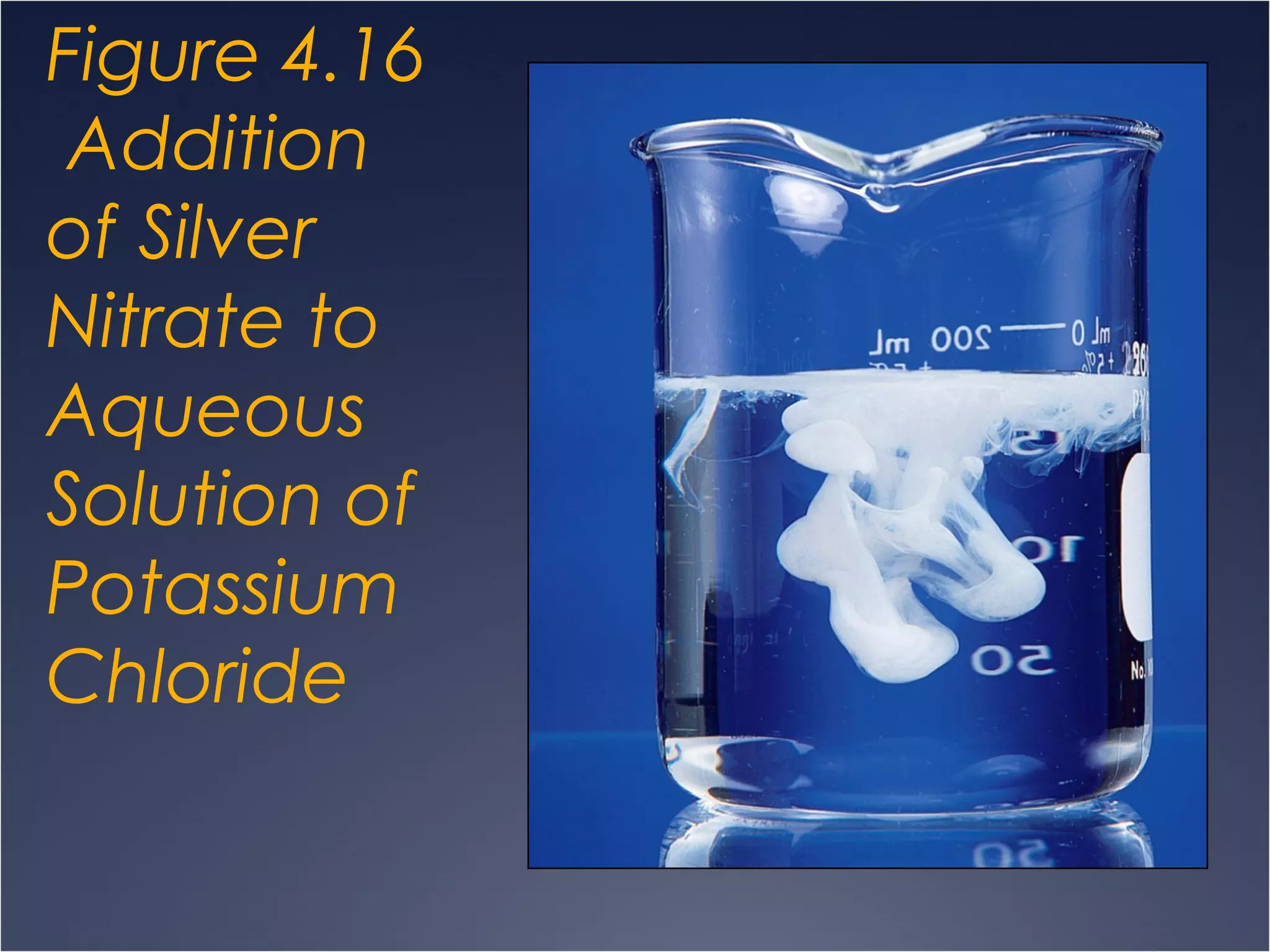

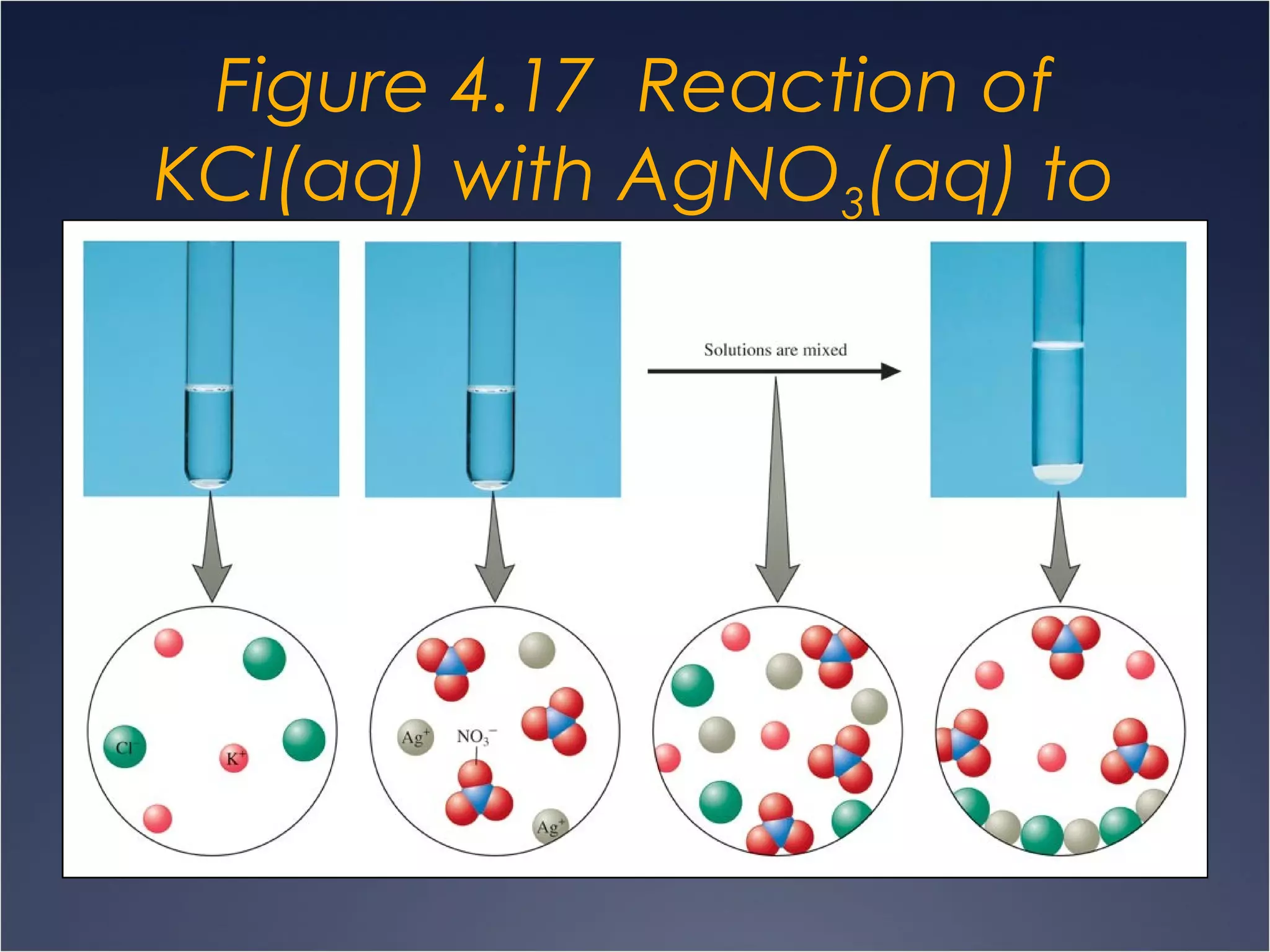

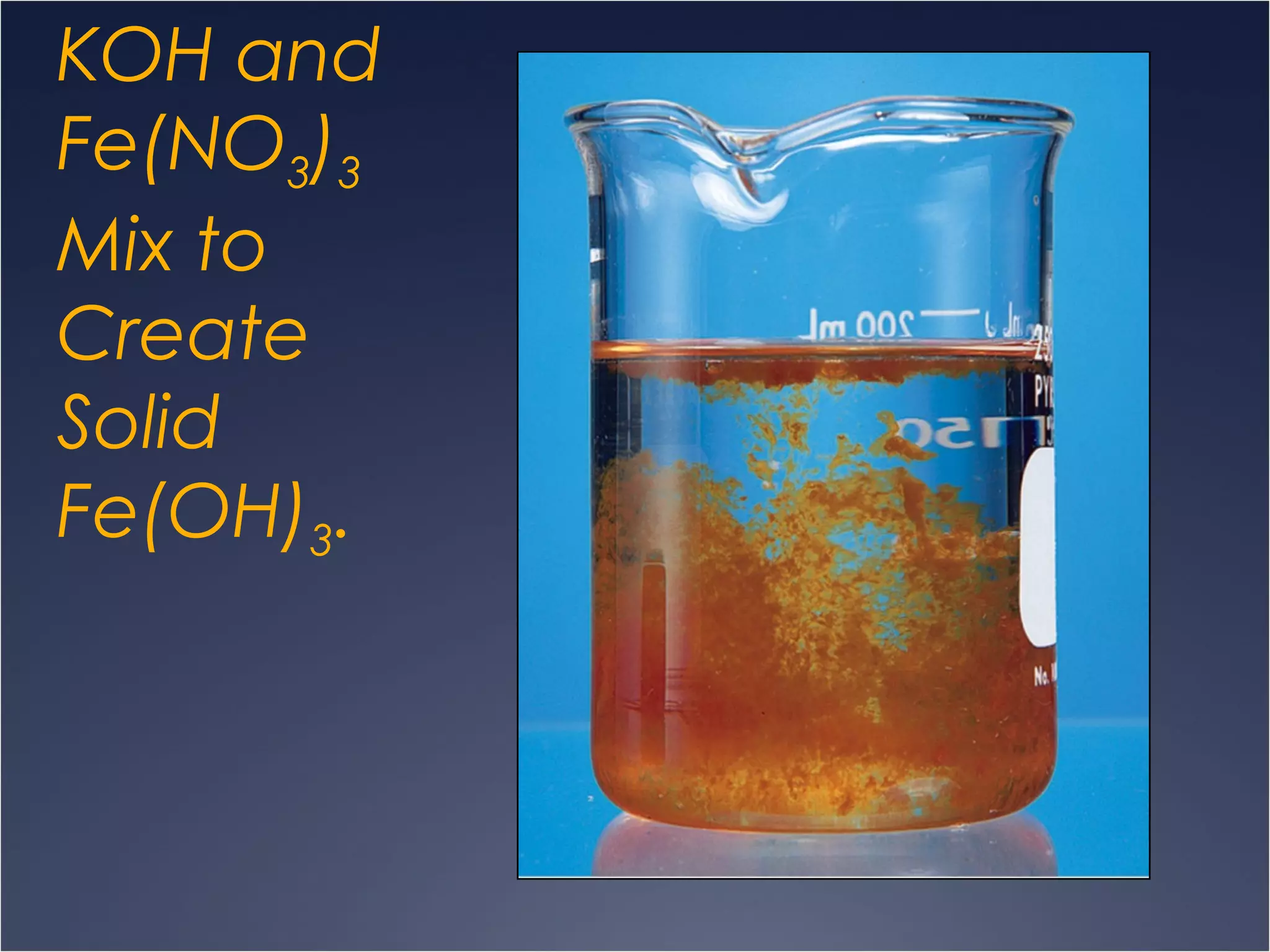

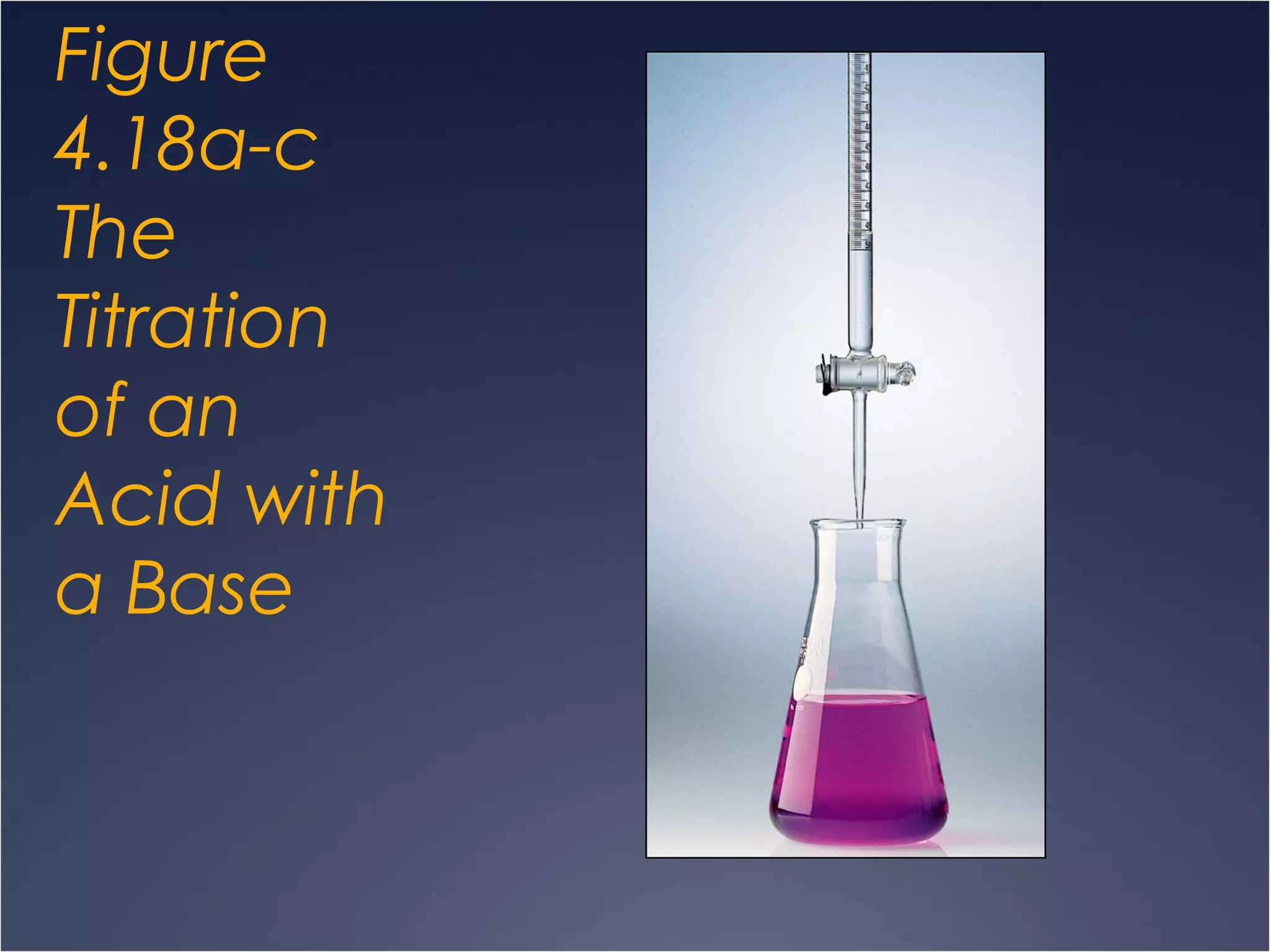

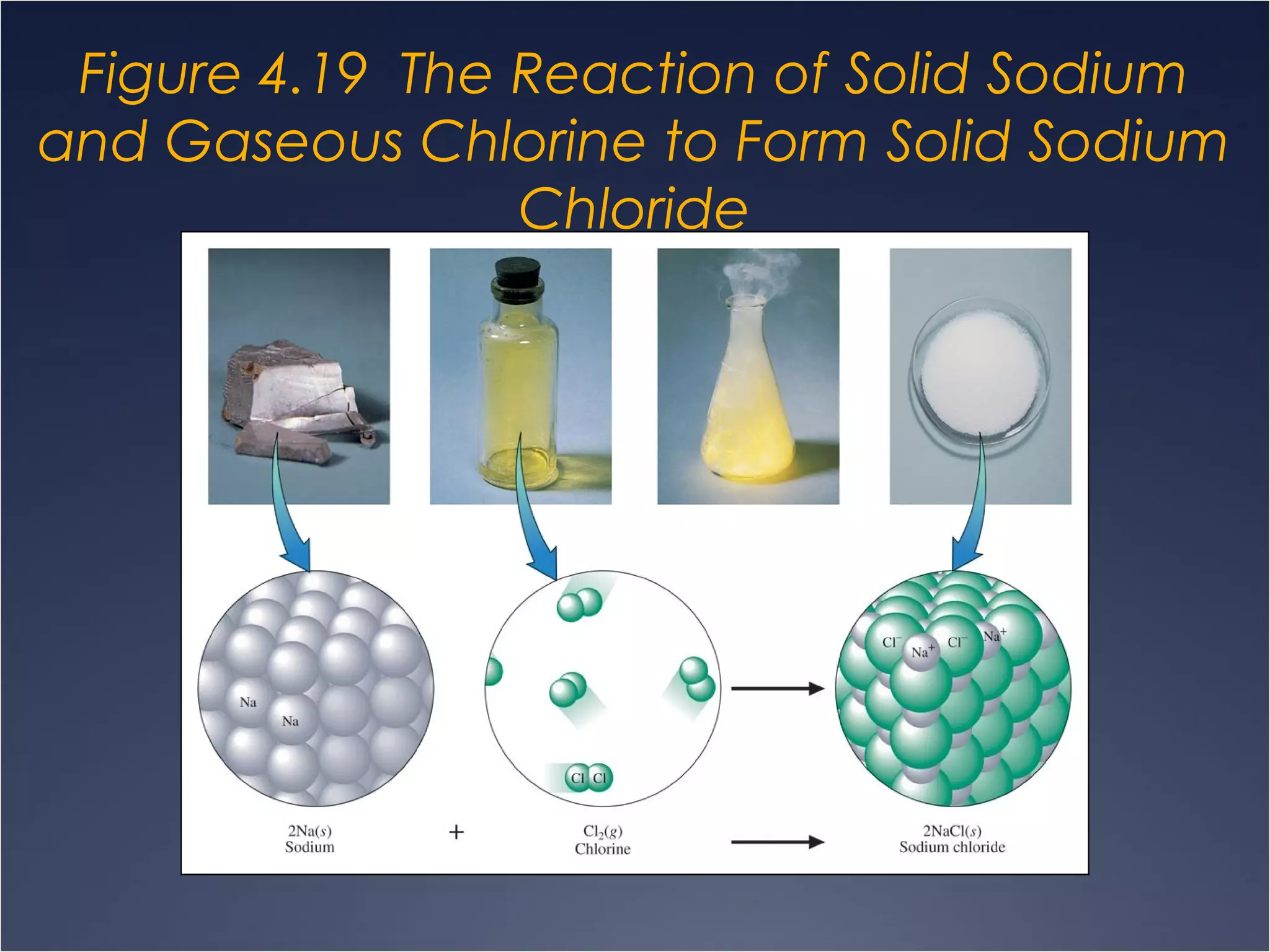

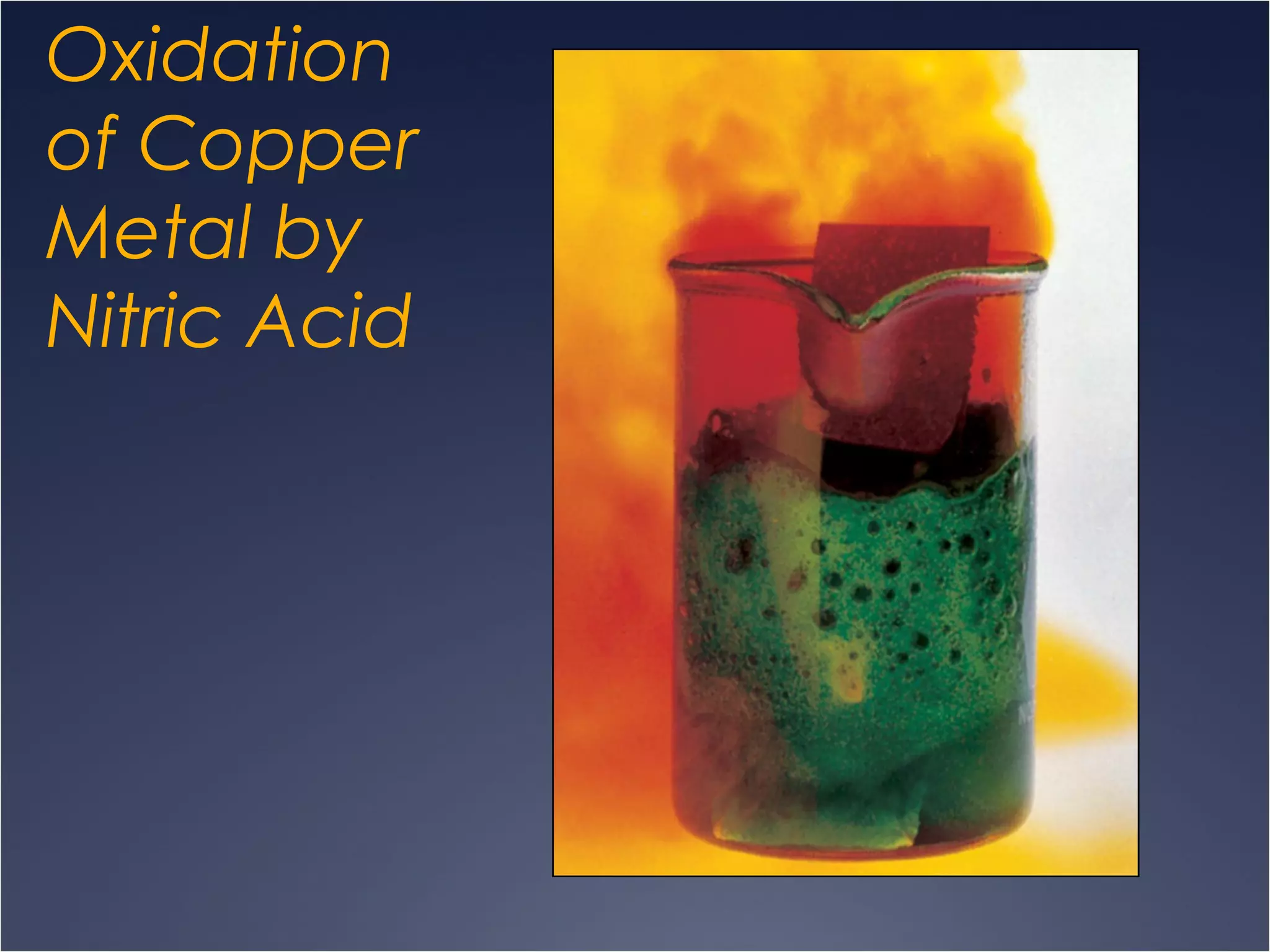

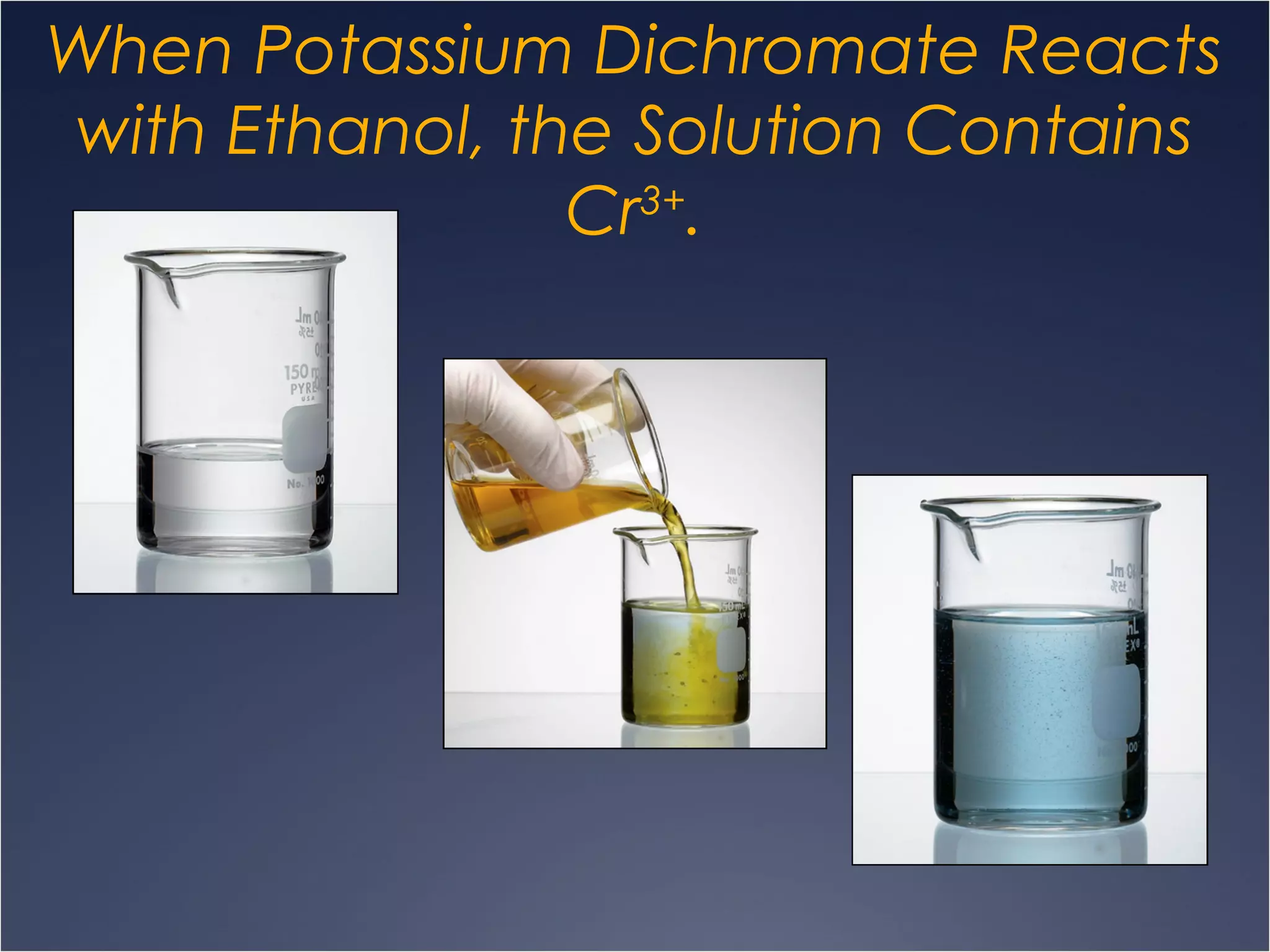

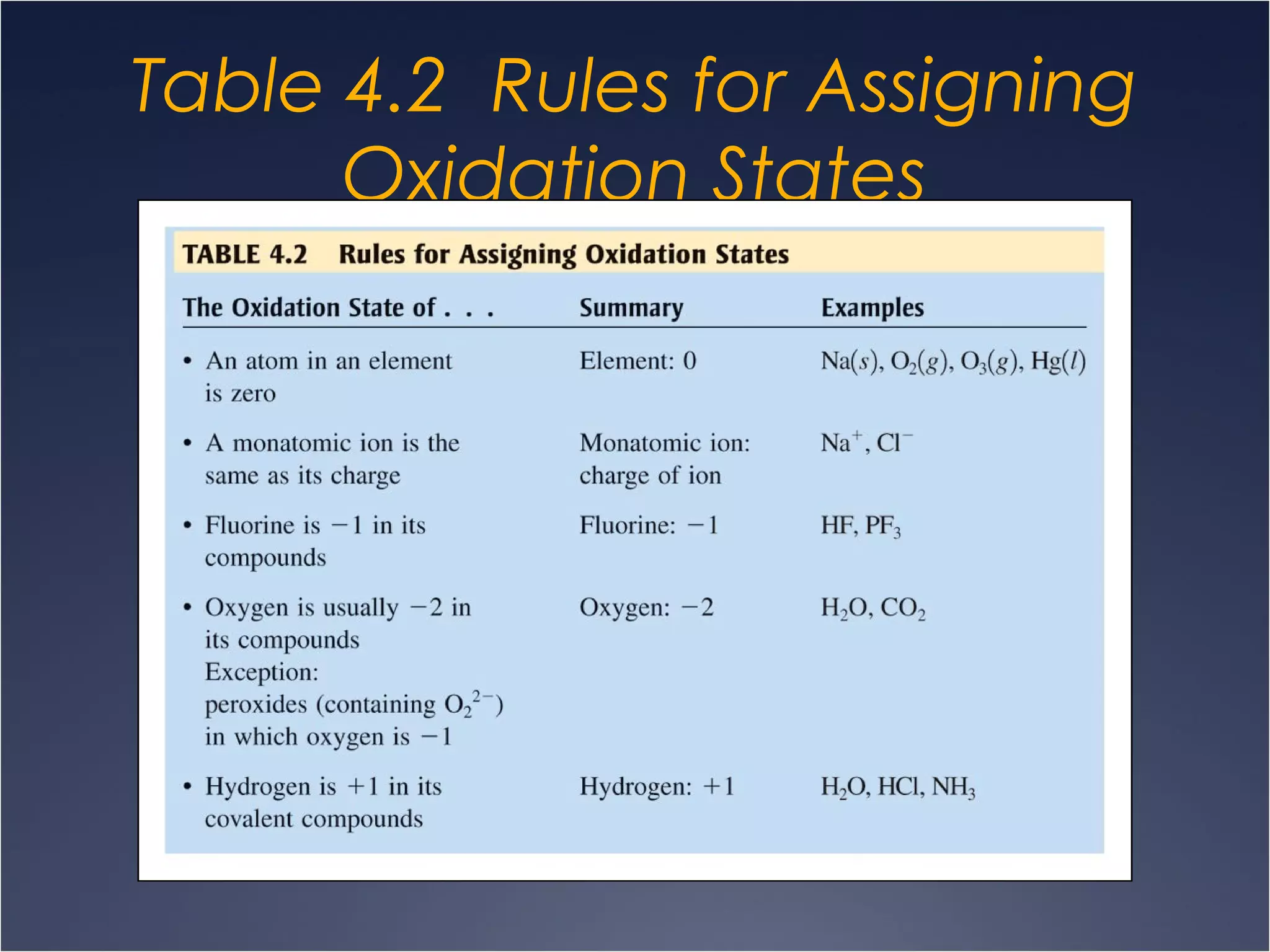

This document provides information on types of chemical reactions and solution stoichiometry. It discusses the common water molecule and how water acts as a solvent. It describes different types of solutions, including strong and weak electrolytes, and nonelectrolytes. Precipitation, acid-base, and oxidation-reduction reactions are introduced. Methods for writing balanced and net ionic equations are presented. Finally, techniques for performing stoichiometric calculations on reactions in solution, including determining limiting reactants and amounts of products formed, are covered.