The document provides 10 research-based tips for improving literacy instruction for students with intellectual disabilities (ID), emphasizing the need for effective strategies to enhance reading skills and independence. It discusses the importance of setting meaningful goals and utilizing a conceptual model for literacy education that balances traditional reading instruction with functional reading. The authors aim to equip educators with tools and frameworks to optimize reading practices and improve outcomes for students with ID.

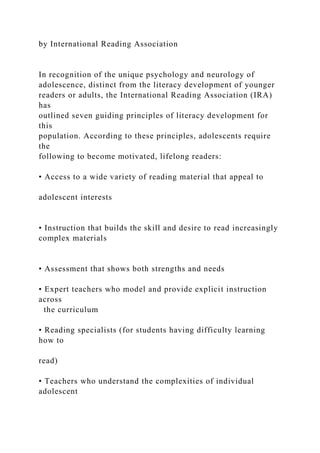

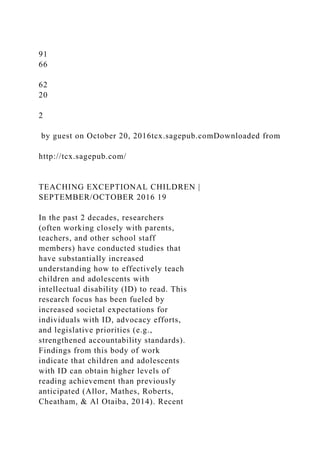

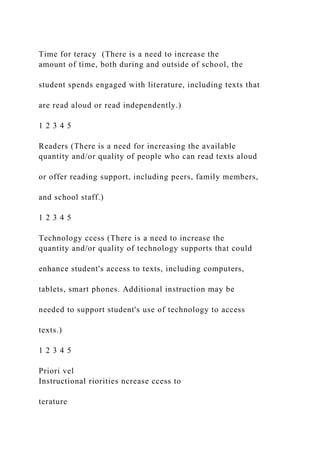

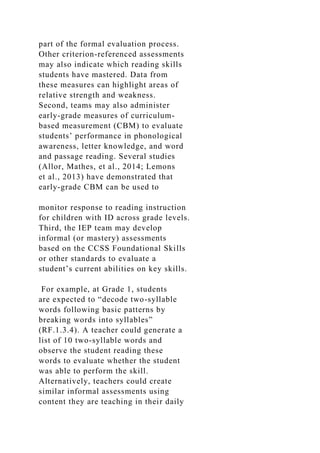

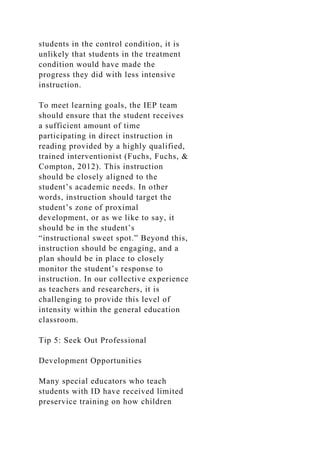

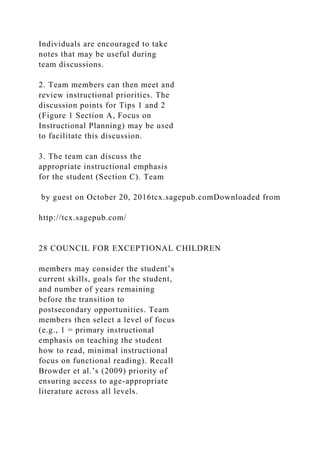

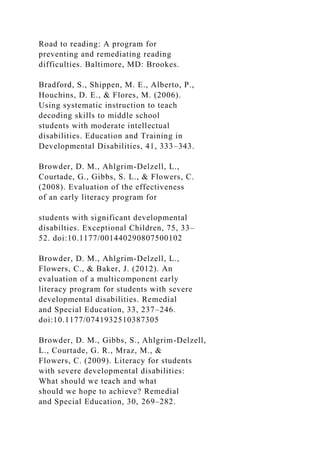

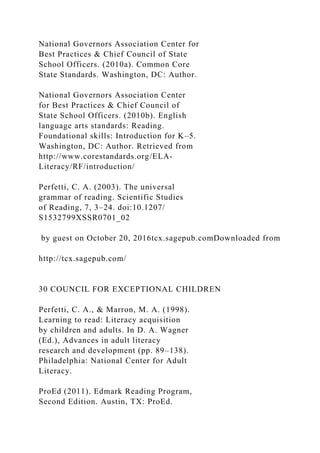

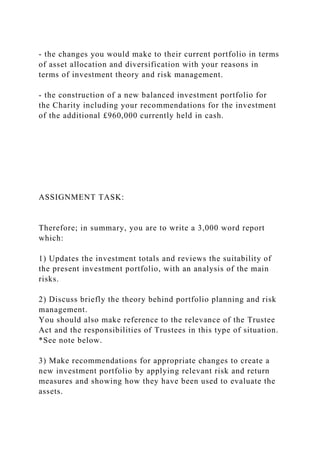

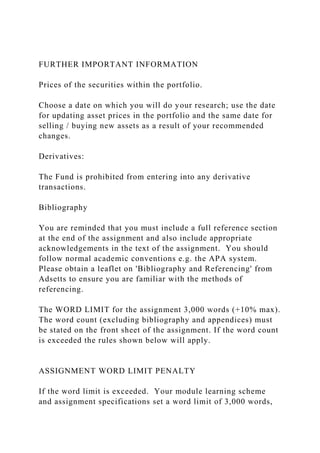

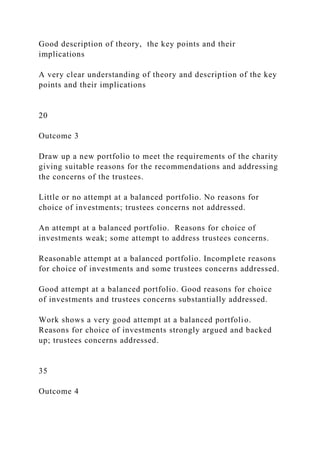

![Opportunities to ppl eneralize kills

Text pplications (Instruction and support is needed

for generalization of reading skills to novel texts.)

1 2 3 4 5

Functional ctivities (Instruction and support is

needed for generalization of reading skills into functional

activities [e.g., menus, newspapers, weather reports,

directions].)

1 2 3 4 5

Writing (Instruction and support is needed to extend

generalization of reading skills into writing, including

options to select pictures, phrases, etc. for students who

are not yet writing.)

1 2 3 4 5

Priori vel

Opportunities to ccess terature

Adapted s (There is a need to increase the

quantity and/or quality of adapted texts to support

learning. Additionally, instruction may be needed to

support student's use of adapted texts.)

1 2 3 4 5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10research-basedtipsforenhancingliteracyinstruct-230107110933-453a75b7/85/10-Research-Based-Tips-for-Enhancing-Literacy-Instruct-docx-12-320.jpg)

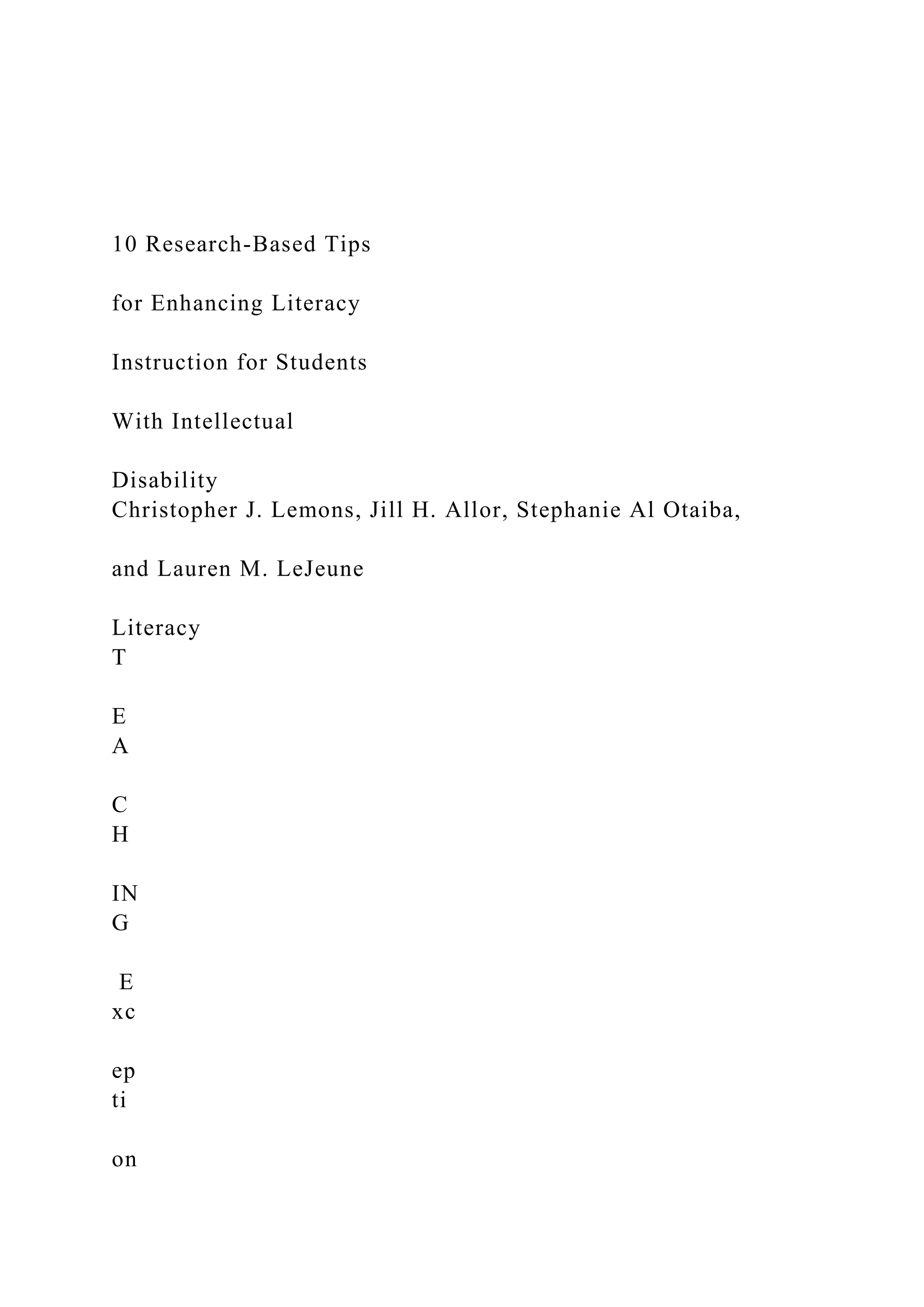

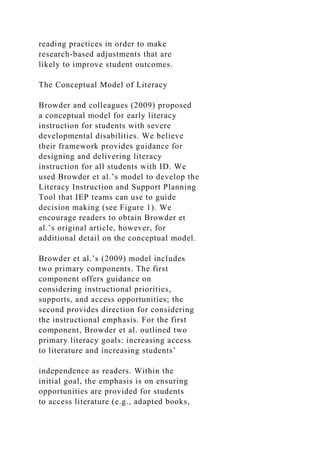

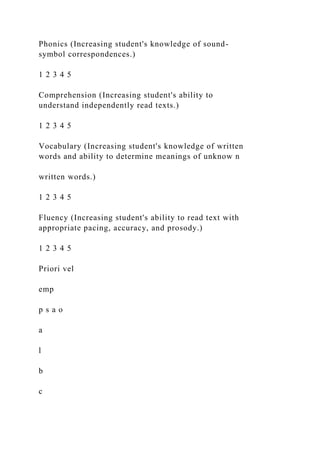

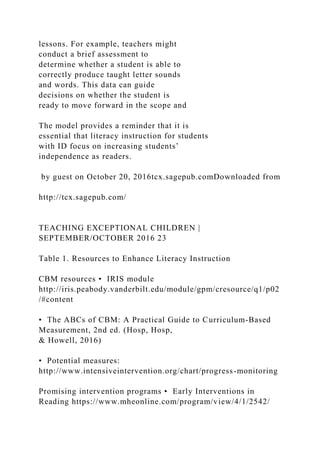

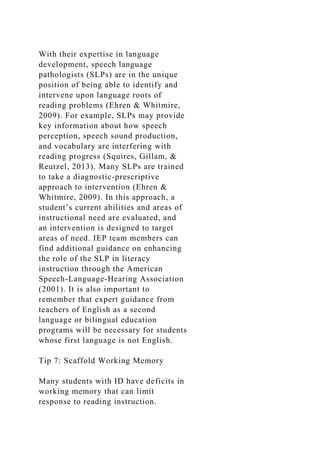

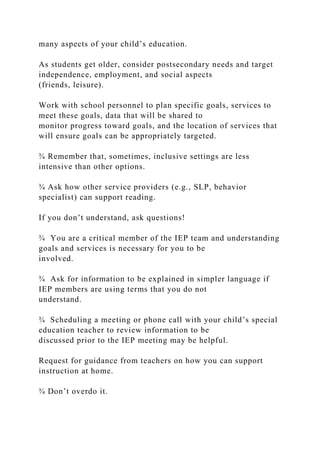

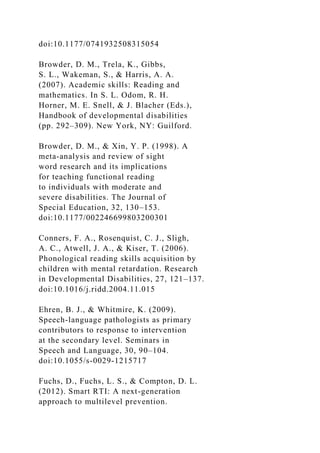

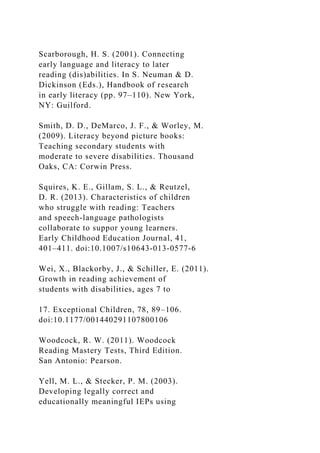

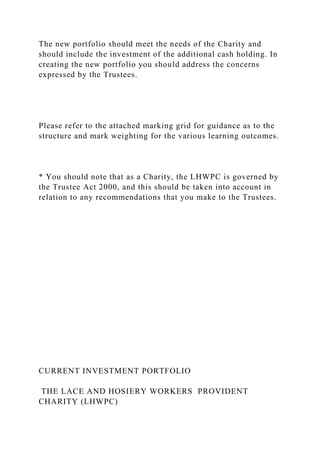

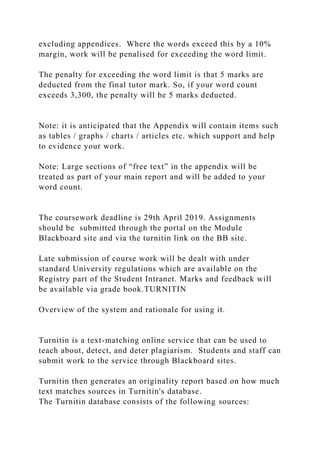

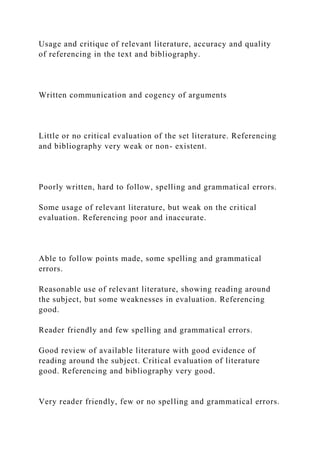

![Task nalysis for ead louds (Instructors need to

systematically plan instruction to support the student's

ability to benefit from texts that are read aloud.)

1 2 3 4 5

Text wareness (Instruction is needed to increase

student's awareness of text features during read alouds

[e.g., student points to key words during read aloud.)

1 2 3 4 5

Vocabulary (Instruction is needed to increase student's

understanding of words during read alouds.)

1 2 3 4 5

Listenin omprehension (Instruction is needed to

increase student's ability to apply grade-level aligned

reading comprehension skills to texts that are read aloud

[e.g., sequencing events, identifying main idea].)

1 2 3 4 5

Priori

Instructional riorities for eadin nstruction

Phonemic wareness (Increasing student's ability to

hear and manipulate sounds in spoken language.)

1 2 3 4 5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10research-basedtipsforenhancingliteracyinstruct-230107110933-453a75b7/85/10-Research-Based-Tips-for-Enhancing-Literacy-Instruct-docx-14-320.jpg)

![(e.g., Edmark [ProEd, 2011], PCI

[Haugen-McLane, Hohlt, & Haney,

2008]). We believe it is important to

integrate phonological awareness and

letter-sound instruction into these sight

word programs as early as possible to

ensure students have the ability to

decode words that are not directly

taught to them.

Tip 4: Provide Instruction With

Sufficient Intensity to Accomplish

Goals

Inclusion and the amount of time

spent with same-age peers without

disabilities in general education

settings are important to consider

when planning for children and

adolescents with ID. However, IEP

teams should consider whether

receiving all instruction in the general

education classroom will allow for a

sufficient level of intensive

intervention to support the student in

meeting reading goals (Zigmond &

Kloo, 2011). There are at least two

important points regarding intensity.

First, in informal discussions with

teachers who have participated in our

recent studies, many have reported

that a substantial number of their

students with ID spend a majority of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10research-basedtipsforenhancingliteracyinstruct-230107110933-453a75b7/85/10-Research-Based-Tips-for-Enhancing-Literacy-Instruct-docx-28-320.jpg)

![cirriculum-based measurement.

Assessment for Effective Intervention, 28,

73–88. doi:10.1177/073724770302800308

Zigmond, N., & Kloo, A. (2011). General

and special education are (and should

be) different. In J. M. Kauffman & D. P.

Hallahan (Eds.), Handbook of special

education (pp. 160–172). New York, NY:

Routledge.

Christopher J. Lemons, Assistant Professor,

Department of Special Education Peabody

College of Vanderbilt University, Nashville,

Tennessee. Jill H. Allor, Professor,

Department of Teaching and Learning,

Southern Methodist University, Dallas,

Texas. Stephanie Al Otaiba, Professor and

Patsy and Ray Caldwell Centennial Chair in

Teaching and Learning, Department of

Teaching and Learning Southern Methodist

University, Dallas, Texas. Lauren M.

LeJeune, Doctoral student, Department of

Special Education, Peabody College of

Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee.

Address correspondence regarding this article

to Chris Lemons, Vanderbilt University, 228

Peabody, Nashville, TN 37212 (e-mail: chris.

[email protected]).

Authors’ Note

The research described in this article was

supported in part by Grants R324A110162,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10research-basedtipsforenhancingliteracyinstruct-230107110933-453a75b7/85/10-Research-Based-Tips-for-Enhancing-Literacy-Instruct-docx-58-320.jpg)

![The department editors welcome reader comments. Douglas

Fisher is a

professor at San Diego State University, California, USA; e-

mail [email protected]

mail.sdsu.edu . Nancy Frey is a professor at San Diego State

University,

California, USA; e- mail [email protected] .

C O N T E N T A R E A L I T E R A C Y

trtr_1258.indd 594trtr_1258.indd 594 4/15/2014 7:54:40

AM4/15/2014 7:54:40 AM

C O N T E N T A R E A V O C A B U L A R Y L E A R N I

N G

595

www.reading.org R T

The value of vocabulary is not limited

to the English language arts standards.

Content area standards also emphasize

the importance of learning words. For

example, the math standards require the

following:

! Kindergarten students must “iden-

tify and describe shapes (squares,

circles, triangles, rectangles, hexa-

gons, cubes, cones, cylinders, and

spheres),” and they must “correctly

name shapes regardless of their](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10research-basedtipsforenhancingliteracyinstruct-230107110933-453a75b7/85/10-Research-Based-Tips-for-Enhancing-Literacy-Instruct-docx-80-320.jpg)

![document camera. Early in the text, they

encounter the word orbit . Mr. Samson

reads the text: “The moon does not stay

still. It travels around, or orbits, Earth”

(n.p.). In response, he says, “I ’ m not

really sure what the word orbit means.

The author says that the moon does

not stay still and that it travels. So I

think that orbit has to do with the moon

moving, but I don ’ t really know if I can

explain it any further. But look, I see that

the word is bolded and highlighted. I

know, when that happens, the word is

probably in the glossary. I ’ m going to

check. [pause] Yep, there it is. It ’ s a path

that the moon takes as it travels around.

I think I will look at the figure again to

see if that works. [returning to original

page] Much better. There ’ s an illus-

tration that shows me the orbit of the

moon around the Earth. That ’ s the path

it takes as it travels around. I think I can

explain that a lot better now, so I think

I ’ ll continue reading.”

Using Words in Discussion

Selecting the right words to teach and

modeling word solving approaches

are important aspects of instruction

necessary to meet the increased expec-

tations in the Common Core State

Standards, but they are insufficient

in and of themselves. Students need

to have time to use the words they

are learning with their teacher and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10research-basedtipsforenhancingliteracyinstruct-230107110933-453a75b7/85/10-Research-Based-Tips-for-Enhancing-Literacy-Instruct-docx-91-320.jpg)