The document discusses probabilistic analysis in the context of algorithm complexity, particularly focusing on the hiring problem and insertion sort. It presents the concept of modeling randomness through indicator random variables and the advantages of enforcing uniform distribution assumptions to improve average-case performance. The document also introduces algorithms for randomization and their implications for hiring and sorting processes.

![1 Introduction

Do you remember the words the “average case”? Actually, these words have a

deeper meaning with respect to what we call a probability and its associated

distribution. Thus, using probability is possible to model the inherent stochastic

event branch structure while running an specific algorithm in an input.

Once you realized the advantages of using probability for complexity anal-

ysis, it is clear that you require to know the distribution where your inputs

operate. Oh!!! Looks fancy, far from it because you already have a course of

probability making easy to understand the following way of modeling branch

randomness over an specific input. Not only that, there are algorithms where

given the “average input,” they behave better than in the worst case. Where

these “average inputs” are inputs randomized using a uniform distribution [2, 1].

Therefore, if we want to obtain the best behavior of those algorithms, we need

to prove that the randomization produce inputs coming from a uniform distri-

bution.

Therefore, to exemplify all these strategies we will start looking at the

stochasticity of the hiring problem [3].

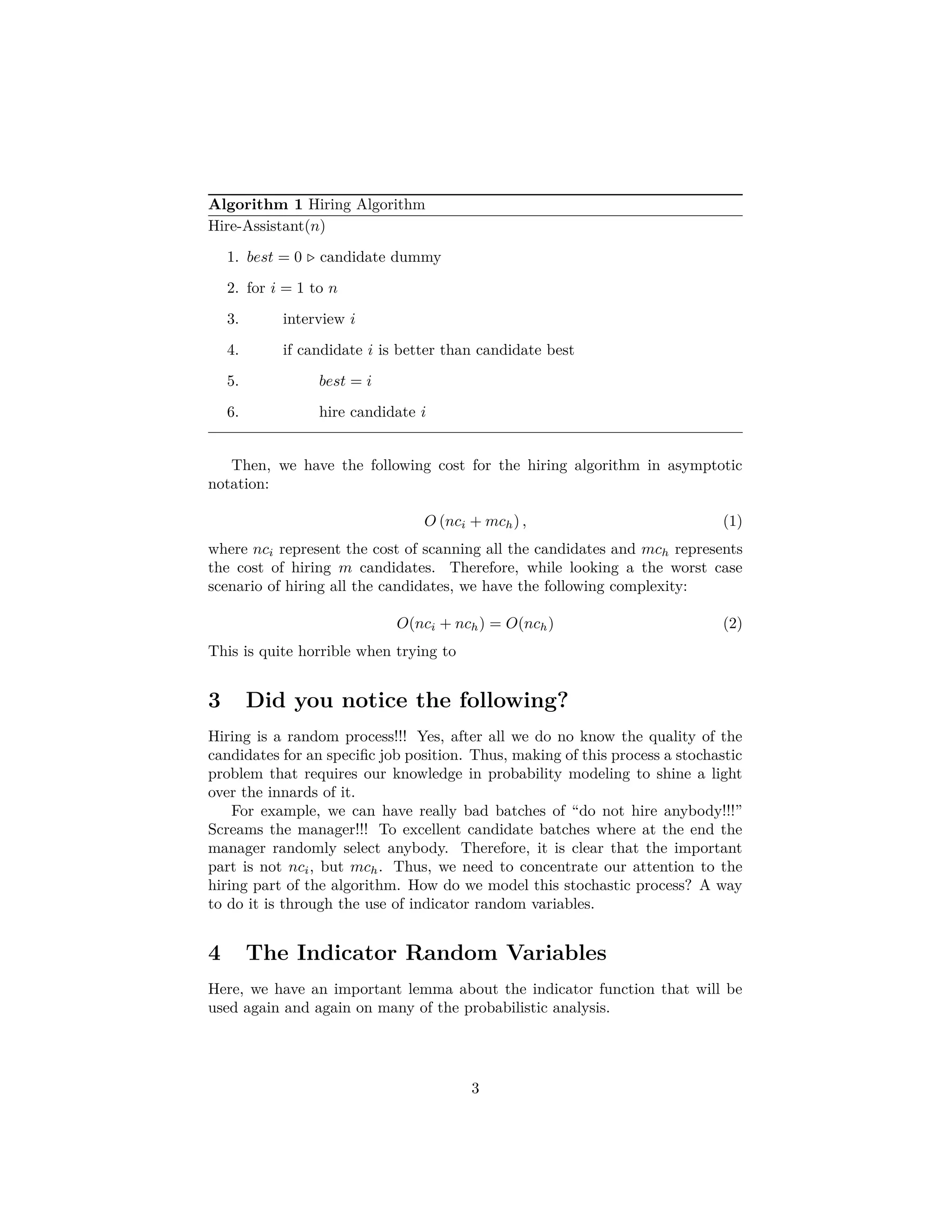

2 The Hiring Problem

The hiring problem exemplifies the classic problem of scanning trough an input

and taking decision on each section of that input. The problem is defined the

following way.

Definition 1. A company needs to hire a new office assistant from a batch

{x1, x2, ..., xn} of possible candidates provided by an employment agency. The

company has the following constraints about the hiring process:

1. We need to interview all the candidates.

2. The job position is never empty.

While looking at this definition of the hiring problem, we notice the following

constraints or restrictions:

• We might hire m of them.

• The cost constraints for each of the possible events are:

– Cost of interviewing: ci per candidate.

– Cost of hiring: ch per candidate.

In addition, we have that ch > ci i.e. the cost of hiring is larger than the cost

of doing an interview. Thus, we have the following algorithm (Algorithm 1) for

the hiring process.

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/03notes-160121170540/75/03-notes-2-2048.jpg)

![Lemma Given a sample space S and an event A in the sample space S, let

XA = I {A}. Then, E (XA) = Pr {A}.

Proof:

Simply look at this

E (XA) = E (I {A}) = 1 × Pr {A} + 0 × Pr A = Pr {A} (3)

Thus, it is possible to use the previous equivalence to solve many problems

by decomposing many complex events in a probability space by using a simple

formula.

Example 2. For example, given a coin being flipped n times. W can define the

following random variable X =The number of heads in n flips of a coin. This

can be decomposed into a sequence of random variables Xi = I{At ith flip you

get a head} by making the simple observation:

X = X1 + X2 + ... + Xn =

n

i=1

Xi (4)

Therefore, taking the expected value in both sides of the equation, we have that

E [X] = E

n

i=1

Xi =

n

i=1

E [Xi] =

n

i=1

1

2

=

n

2

(5)

Another example is using a Bernoulli distribution to guess how many nuclear

missiles will hit their targets.

Example 3. Given that the probability of hitting a target by nuclear missile

is p. Now, you launch n of them to it, thus ¿How many of them will hit the

target? First every launch is a Bernoulli trial. Now, given that Xi = I{The ith

launch hits the target}. The total number of successes is

X = X1 + X2 + ... + Xn (6)

Then, again using the Bernoulli and expected value:

E [X] = E [X1 + X2 + ... + Xn] (7)

Thus, by the linearity of the expectation E [X] = E [X1] + E [X2] + ... + E [Xn]

where E [Xi] = P (Ai) = p. Finally,

E [X] =

n

i=1

E [Xi] =

n

i=1

p = np.

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/03notes-160121170540/75/03-notes-4-2048.jpg)

![5 Analyzing Random Hiring

Now, we analyze the hiring from the randomized point of view. For this, we first

assume that the candidates are interviewed in a random way using a uniform

distribution which is called the Uniform Assumption. This allows to assume

that any of the candidates, when we have i of them, could be hired. This can

be represented by the following random indicator variable:

Xi = I {Candidate i is hired} =

1 if candidate i is hired

0 if candidate i is not hired

(8)

Thus, we have the following probability for the event “Candidate i is hired”:

Pr {Candidate i is hired} =

1

i

. (9)

This can only happen if candidate i is better than the previous i−1 candidates.

Finally, we have an “average case”:

E [Xi] = Pr {Cantidate i is hired} =

1

i

. (10)

Now, we can generate a new random variable that represents:

X = The total number of hirings, (11)

which can be decomposed in a sequence of simpler random variables:

X = X1 + X2 + ... + Xn (12)

Now, if we apply the expected value to both sides of the equation, we have

E [X] =E

n

i=1

Xi =

n

i=1

E [X] (Linearity of the Expected Value)

=

n

i=1

1

i

= 1 +

n

i=2

1

i

≤1 +

ˆ n

1

1

i

di (Decreasing Function)

=1 + ln n,

Therefore, the expected value or average case has the following complexity:

E [X] = ln n + O (1) (13)

Then, the final cost of hiring is O (ch ln n) . Actually this proof of the complexity

O(ch log n) is the same once we notice that the permutation of the elements is

giving us the same situation as in the hiring when the input order (The order

of interviewing) is drawn from a uniform distribution.

Therefore, given the differences between worst case hiring and randomized

hiring is quite extreme, it could be a good idea to enforce the uniform assumption

to get the better expected complexity.

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/03notes-160121170540/75/03-notes-5-2048.jpg)

![6 Enforcing the Uniform Assumption

Imagine now that

• The employment agency sends us a list of all n candidates in advance.

• On each day, we randomly choose a candidate from the list to interview.

• Instead of relaying on the candidate being presented to us in a random

order, we take control of the process and enforce a random order.

This is giving us the idea of a randomized algorithm where

• An algorithm is randomized if its behavior is determined in part by

values produced by a random-number generator.

• A random-number generator [4] is implemented by a pseudorandom-

number generator, which is a deterministic method returning numbers

that “look” random and can pass certain statistical tests.

An example of a randomized algorithm version of hiring can be seen in (Algo-

rithm 2).

Algorithm 2 Hiring Algorithm

Randomized-Hire-Assistant(n)

1. Randomly Permute the list of candidates

2. best ← 0 candidate dummy

3. for i = 1 to n

4. interview i

5. if candidate i is better than candidate best

6. best ← i

7. hire candidate i

We have a small problem in the line on where the algorithms “Randomly

Permute the list of candidates.” For this, we are required to have algorithms

that enforce the uniform assumption on that instruction. The algorithms that

we are going to see in this course are:

• Permute By Sorting (Algorithm 3).

• Randomize in Place (Algorithm ).

Each of them uses a lemma to prove that they enforce the uniform assump-

tion in an input.

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/03notes-160121170540/75/03-notes-6-2048.jpg)

![Algorithm 3 Permute By Sorting Algorithm

Permute-By-Sorting(A)

1. n = lenght[A]

2. for i = 1 to n

3. do P[i] = RANDOM 1, n3

4. sort A, using P as sort keys

5. return A

Algorithm 4 Randomize in Place Algorithm

Randomize-In-Place(A)

1. n = lenght[A]

2. for i = 1 to n

3. do swap A[i] ←→ A[RANDOM(i, n)]

6.1 Lemma for Permute By Sorting

In this section, we prove the fact that a randomization based in permutation

works if we can trust in our pseudo-random generator. Nevertheless, for a deeper

study on these random generators, we recommend to take a look at chapter 3

volume 2 of Donald Kunth “The Art of Computer Programming” [4].

Lemma 5.4

Procedure Permute-by-sorting produces a uniform random permutation

of the input, assuming that all probabilities are distinct.

Proof:

Case I

Assume A[i] receives the ith smallest priority. Let Ei be the event that

element A[i] receives the ith

smallest probability. Therefore, we wish to

compute the event the probability of event E1 ∩ E2 ∩ ... ∩ En, and given

that we haven! possible permutations of the ranking, we want to be sure

that the P(E1 ∩ E2 ∩ ... ∩ En) = 1

n! . This event is the most naive one,

it means that A[1]is the 1st element, A[2] is the 2nd element and so on.

Then, it is simply a case of using the chain rule:

P(E1, E2, ..., En) = P(En|E1, ..., En−1)P(En−1|E1, ..., En−2)...

P(E2|E1)P(E1)

(14)

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/03notes-160121170540/75/03-notes-7-2048.jpg)

![First imagine that you have n possible positions at your array and you

need to fill them. Now look at this:

• At E1 you have n different elements to put at position one or P(E1) =

1

n .

• At E2 you have n − 1 different elements to put at position two or

P(E2|E1) = 1

n−1 .

• etc.

Therefore, P(E1, E, ..., En) = 1 × 1

2 × 1

3 × ... × 1

n = 1

n! .

Case II

In the general case, we have that we can use for any permutation σ =

σ(1), σ(2), ..., σ(n) of the set {1, 2, ..., n}. Let us to assign rank ri to the

element A[i]. Then, if we define Ei as the event in which element A[i]

receives the σ(i)th

smallest priority such that ri = σ(i), we have the same

proof.

QED

6.2 Lemma for Randomize in Place

Now, we prove the the randomization in place can enforce the uniform assump-

tion.

Lemma 5.5

Procedure RANDOMIZE-IN-PLACE computes a uniform random permu-

tation.

Proof:

We use the following loop invariant, before entering lines 2-3 the array A[1, ..., i−

1] contains a (i − 1)-permutation with probability (n−i+1)!

n! .

Initialization. We have an empty array A[1, ..., 0] and i = 1, then P(A[1, ..., 0]) =

(n−i+1)!

n! = n!

n! = 1. This is because of vacuity.

Maintenance. Then, by induction, we have that the array A[1, ..., i − 1] con-

tains (i − 1)-permutation with probability (n−i+1)!

n! . Now, consider the

i-permutation contain the elements x1, x2, ..., xi = x1, x2, .., xi−1 ◦ xi.

Then, E1denotes the event for the (i − 1)-permutation with P(E1) =

(n−i+1)!

n! , and E2 denotes putting element xi at position A[i]. Therefore,

we have that P(E2 ∩ E1) = P(E2|E1)P(E1) = 1

n−i+1 × (n−i+1)!

n! = (n−i)!

n! .

Termination. Now with i = n + 1 we have that the array A[1, ..., n] contains

a n−permutation with probability (n−n+1)!

n! = 1

n! .

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/03notes-160121170540/75/03-notes-8-2048.jpg)

![7 Application of Probabilistic Analysis: Inser-

tion Sort

From chapter 1, it was possible to see that the total number of steps done by

the insertion sort is

n + I, (15)

where I is a random variable that count the total number of possible inversions.

Here, the event of an inversion at positions i and j of an array A can be described

by an indicator random variable:

Iij = I {if i < j A [i] > A [j]} . (16)

Then, we have that

I =

n

i=1

n

j=1,i=j

Iij. (17)

Now, we get the final formulation of the number of steps for insertion sort as

n + I = n +

n

i=1

n

j=1,i=j

Iij. (18)

Finally, we can apply the the expected value to both sides of the equation

E [n + I] = E

n +

n

i=1

n

j=1,i=j

Iij

, (19)

and because the linearity of the expected value (n is a constant), we have that

E [n + I] =n + E [I]

=n + E

n

i=1

n

j=1,i=j

Iij

=n +

n

i=1

n

j=1,i=j

E [Iij] .

Now, we have that, by assuming the uniform assumption,

E [Iij] =

1

2

. (20)

Finally,

E [n + I] = n +

n

i=1

n

j=1,i=j

1

2

= n +

1

2

n

i=1

n

j=1,i=j

1 = n +

n (n − 1)

2

, (21)

because

n

i=1

n

j=1,i=j 1 counts the number of different pair that you can count

with n elements. Thus, the complexity of insertion sort for the average case is

O n +

n (n − 1)

2

= O

n

2

+

n2

2

= O n2

. (22)

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/03notes-160121170540/75/03-notes-9-2048.jpg)

![References

[1] R.B. Ash. Basic Probability Theory. Dover Books on Mathematics Series.

Dover Publications, Incorporated, 2012.

[2] George Casella and Roger L. Berger. Statistical Inference. Pacific Grove:

Duxbury Press, second edition, 2002.

[3] Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford

Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Third Edition. The MIT Press, 3rd edi-

tion, 2009.

[4] Donald E. Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2 (3rd Ed.):

Seminumerical Algorithms - Chapter 3 - Random Numbers. Addison-Wesley

Longman Publishing Co., Inc., Boston, MA, USA, 1997.

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/03notes-160121170540/75/03-notes-10-2048.jpg)