Saving Land Spring 2015

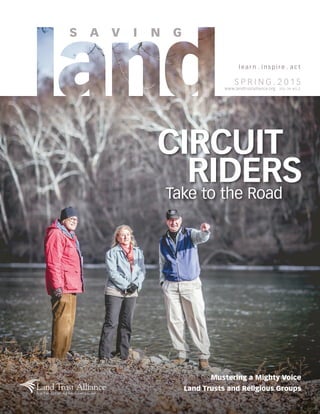

- 1. l e a r n . i n s p i r e . a c t S P R I N G . 2 0 1 5 www.landtrustalliance.org VOL.34 NO.2 Mustering a Mighty Voice Land Trusts and Religious Groups CIRCUIT RIDERSTake to the Road

- 2. 2 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org S P R I N G . 2 0 1 5 www.landtrustalliance.org VOL.34 NO.2 14 COVER STORY The Ever-Changing Life of a Circuit Rider By Kirsten Ferguson An exciting new regional program of the Land Trust Alliance sends specialists to provide assistance and support to small and all-volunteer land trusts. GREENBOMB STUDIOS ON THE COVER: Circuit rider Don Owen (right) in West Virginia meets with Grant Smith, president of the Land Trust of the Eastern Panhandle, and Liz Wheeler, executive director of the Jefferson County Farmland Protection Board. DJ GLISSON, II/FIREFLY IMAGEWORKS DJGLISSON,II/FIREFLYIMAGEWORKS

- 3. www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 3 OUR MISSION To save the places people love by strengthening land conservation across America. THE LAND TRUST ALLIANCE REPRESENTS MORE THAN 1,700 LAND TRUSTS AND PROMOTES VOLUNTARY LAND CONSERVATION TO BENEFIT COMMUNITIES THROUGH CLEAN AIR AND WATER, FRESH LOCAL FOOD, NATURAL HABITATS AND PLACES TO REFRESH OUR MINDS AND BODIES. DEPARTMENTS 5 From the President Invest in Yourself 6 Conservation News Citizen scientists lend a hand; local food lovers put their money where their mouths are; birds link western land trusts; and more news of note 10 Policy Roundup Land Trust Ambassadors cultivate relationships that bear fruit 12 Voiced The first woman to chair the Alliance board tells us about herself 28 Board Matters Do you have a crisis communications plan? 31 Accreditation Corner Great changes are being implemented based on feedback from land trusts 32 Fundraising Wisdom Turbocharge your land trust with these five tips 34 Resources Tools New risk management tool online; learning kits a big hit; western land trusts get a help desk; and more 36 People Places Board news; bird stories continued; time for Alliance awards nominations; Ear to the Ground 38 Inspired Praise from Capitol Hill table of CO NTENT Sl e a r n . i n s p i r e . a c t BOBWILBER FEATURE 18 Mustering a Mighty Voice By Christina Soto During two action-packed months at the end of 2014, the Land Trust Alliance rallied its allies in the fight for the conservation tax incentive, unifying its amazing members and partners and demonstrating the power of one voice. TOMCOGILLKIMBERLYSEESE LAND WE LOVE 20 Chronicling a Community’s Roots A book by the Cacapon and Lost Rivers Land Trust tells the stories of the people in this beautiful valley who love their land. FEATURE 24 Higher Ground By Edith Pepper Goltra Land trusts are uniquely positioned to advise religious entities about ways to address their financial needs while remaining true to the land entrusted to their care.

- 4. S A V I N G L AND TRUST ALLIANCE BOARD Laura A. Johnson CHAIR Jameson S. French VICE CHAIR Frederic C. Rich VICE CHAIR William Mulligan SECRETARY/TREASURER Lise H. Aangeenbrug Laurie Andrews Robert A. Ayres Alan M. Bell Maria Elena Campisteguy Lauren B. Dachs Michael P. Dowling IMMEDIATE PAST CHAIR Blair Fitzsimons Elizabeth M. Hagood Peter O. Hausmann Sherry F. Huber Cary F. Leptuck Fernando Lloveras San Miguel Mary McFadden George S. Olsen Steven E. Rosenberg Judith Stockdale Darrell Wood STAFF Rand Wentworth PRESIDENT Mary Pope Hutson EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT Marilyn Ayres CHIEF OPERATING FINANCIAL OFFICER Rob Aldrich Nancy A. Baker Lorraine Barrett Sylvia Bates Lindsay Blair Mary Burke Kevin Case Peshie Chaifetz Katie Chang Linette Curley Bryan David Laura E. Eklov Donyé Ellis Bethany Erb Suzanne Erera Katie Fales Hannah Flake Artis Freye Jennifer Fusco Daniel Greeley Joanne Hamilton Meme Hanley Heidi Hannapel Maddie Harris Erin Heskett Katrina Howey T.J. Keiter Renee Kivikko Justin Lindenberg Joshua Lynsen Bryan Martin Mary Ellen McGillan Sarah McGraw Andy McLeod Shannon Meyer Wendy Ninteman MaryKay O’Donnell Brad Paymar Loveleen “Dee” Perkins Leslie Ratley-Beach Sean Robertson Collette Roy Kimberly Seese Russell Shay Claire Singer Lisa Sohn Christina Soto Scott Still Patty Tipson Alice Turrentine Mindy Milby Tuttle Carolyn Waldron Elizabeth Ward Rebecca Washburn Andy Weaver Todd S. West Ethan Winter SAVING LAND Elizabeth Ward EXECUTIVE EDITOR Christina Soto EDITOR SAVING LAND ® , a registered trademark of the Land Trust Alliance (ISSN 2159-290X), is published quarterly by the Land Trust Alliance, headquartered at 1660 L St. NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20036, and distributed to members and donors at the $35 level and higher. © 2015 BY THE LAND TRUST ALLIANCE This publication is designed to provide accurate, authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is distributed with the understanding that the publisher, authors and editors are not engaged in rendering legal, accounting or other professional services. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. Bates Creative Group LLC DESIGN PRODUCTION 100% GREEN POWER WIND SOLAR GOETZ PRINTING www.landtrustalliance.org Your support of Together: A Campaign for the Land will accelerate the land conservation movement by increasing the pace, improving the quality and ensuring the permanence of land conservation now and into the future. Participate today at donate.lta.org. $500 MILLION+ over 10 years for the purchase of easements on farm and ranch lands in the 2014 Farm Bill 277 bipartisan votes to pass the enhanced tax incentive in the House (work continues to make it permanent) Increase the Pace of Land Conservation Improve the Quality of Land Conservation 75% of conserved land now held by accredited land trusts $2 Million in services to prepare land trusts for accreditation 301 accredited land trusts of acres under conservation easement now either held by Terrafirma members or organizations capable of self-insuring Ensure the Permanence of Land Conservation 454 89% member land trusts enrolled in Terrafirma 50 Million acres of land conserved by land trusts *as of January 1 $4.8 Million Still Needed Together, Our Progress $30.2 Million raised Over the past four years this campaign has funded the work of the Land Trust Alliance and enabled significant accomplishments for land conservation.

- 5. www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 5 from the PRESIDENT As a pilot with US Airways, Chesley Sullenberger’s job on January 15, 2009, was to fly an Airbus A320 with 150 passengers from La Guardia to Charlotte. He raced down the runway, lifted the nose of the plane and soared into the blue sky above New York City. Within two minutes, however, both engines lost power and the plane began to drop. Instead of panicking, he calmly guided the plane to the only open place available: the Hudson River. You may remember the riveting pictures of the plane slowly sinking in the frigid water while passengers climbed out onto the wings—Sullenberger was the last to leave the plane. He did not lose a single passenger. Sullenberger did not think of himself as a hero—he just did what he was trained to do. He was a lifelong learner: an Air Force fighter pilot, flight instructor, glider pilot and safety expert. That preparation made it possible for him to act when it counted. It takes skill and preparation to run a land trust. Whether you are a board member or staff, you need to be an expert in just about everything: real estate, law, marketing, fundraising and business management. That’s why each year we offer a host of work- shops, webinars and courses on our online Learning Center. Last year we provided training services to 3,500 land trust leaders. And now we offer customized training for board members of land trusts. In this issue of Saving Land you’ll read about our new circuit riders who travel from town to town and meet with board members of volunteer-led land trusts. They help boards organize records, conduct baseline documentation or qualify for Terrafirma. The Alliance also has created an online tool for boards to understand and manage the risks of owning property and running an organization (see page 13). You can learn more on The Learning Center at http://tlc.lta.org/riskmanagement. Leaders are not born; they are shaped over time. Invest in yourself and your land trust by taking advantage of one of our training programs. You will expand the impact of your land trust and save more land. As the “pilot” of your land trust, you are responsible for the lands that rely on you for their care and safety. We can help you develop the skills you need. Happy flying. Invest in Yourself DJGLISSON,II/FIREFLYIMAGEWORKS Fall 2013 Vol. 32 No. 4 SAVING LAND EDITORIAL BOARD David Allen Melanie Allen Sylvia Bates Story Clark Jane A. Difley Kristopher Krouse James N. Levitt Connie A. Manes David A. Marrone Larry Orman Andy Pitz Marc Smiley NATIONAL COUNCIL Peter O. Hausmann CHAIR Mark C. Ackelson David H. Anderson Sue Anschutz-Rodgers Matthew A. Baxter Tony Brooks Christopher E. Buck Joyce Coleman Lester L. Coleman Ann Stevenson Colley Ferdinand Colloredo- Mansfeld Debbie Craig James C. Flood Elaine A. French Natasha Grigg Marjorie L. Hart Alice E. Hausmann Albert G. Joerger David Jones Tony Kiser Sue Knight Anne Kroeker Glenn Lamb Kathy K. Leavenworth Richard Leeds Penny H. Lewis Gretchen Long Mayo Lykes Susan Lykes Bradford S. Marshall Will Martin Mary McFadden, J.D. Nicholas J. Moore John R. Muha Jeanie C. Nelson Caroline P. Niemczyk Michael A. Polemis Thomas A. Quintrell Thomas S. Reeve Christopher G. Sawyer Walter Sedgwick J. Rutherford Seydel, II Julie R. Sharpe Lawrence T.P. Stifler, Ph.D. Maryanne Tagney David F. Work Rand Wentworth

- 6. 6 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org V olunteer naturalists and hobbyists who collect and report data for citizen science projects are critical to our understanding of the timing of natural events, the health of waterways and the impacts of climate change, according to a March 2014 article in the journal Science. The article acknowledges that the science community has not universally accepted data from non-scientists as valid scientific research, but technology is helping to change this perspective. Through the Internet and mobile devices, amateurs can connect with and contribute data to scientific studies, and better volunteer training and computer data analysis are helping to ensure the validity of their information. “There are well over a million citizen scientists solving real-world problems: figuring out protein structures, transcribing the writing on ancient scrolls,” says lead author Rick Bonney, director of program development and evaluation at the Cornell Lab of Orni- thology. “People are studying genes to galaxies and everything in between.” Citizen science projects can serve the dual purpose of community outreach and scientific research, the article suggests. For example, a sea turtle monitoring network in northwest Mexico helped establish marine protected areas and sustainable fishery practices. In Oakland, California, individuals in a high-poverty neighborhood collected air quality and health data to document air pollution’s effects on residents. For more information see www.sciencemag.org/content/343/6178/1436. summary?sid=0c854a05-1170-4acc-876c-1968616900ed. • Applause for Citizen Scientists conservation N EWS COMPILED BY Kendall Slee CHRISTINEBARTHOLOMEW C onsumers are increasingly seeking locally produced foods, say food and agricultural trend watchers. “People believe in the integrity of small farmers and local food producers, seeing them as deeply invested in the quality of their products,” writes Laurie Demeritt, CEO of the Hartman Group, a research firm that produced the “Organic and Natural 2014” food report (www.hartman- group.com/publications/reports/organic- natural-2014). The report found organic food buyers are increasingly shopping farm markets. “‘Local’ is emerging as a category poised to surpass both organic and natural as a symbol of transparency and trust,” the report summarizes. In a December 2014 article, the agricul- tural news service Agri-View reported that a majority of people of all ages and income levels are willing to pay more for locally produced foods. • CHRISCIRKUS,WESTWINDSORCOMMUNITYFARMERSMARKET Locavores Rising Young people participate in the Great Backyard Bird Count citizen science project, held in February. Shoppers browse Slow Food Central New Jersey’s Winter Farmers Market at DR Greenway Land Trust’s Johnson Education Center in Princeton. DR Executive Director Linda Mead says providing a venue for the market “engages a broader audience in our work while keeping local foods in the Garden State.”

- 7. www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 7 T he golden-winged warbler has experienced one of the steepest declines of any North American songbird over the past 45 years. Once ranging across the northern Midwest, Great Lakes and Appalachian states, the bird has lost much of its shrubland breeding habitat to development, agriculture and maturing forests. The dwindling numbers of golden-winged warblers that breed around the Great Lakes now represent 95% of the world population. The Thousand Islands Land Trust and Indian River Lakes Conservancy are partnering with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Audubon New York, New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation and Clarkson University to protect the imperiled warbler in one of its last strongholds. Their St. Lawrence Valley Partnership for Golden-winged Warblers is supported by a New York State Conservation Partnership Program Catalyst Grant, awarded in 2014 by the Land Trust Alliance through New York’s Environmental Protection Fund. Partners will take a multipronged approach to enhancing and expanding the bird’s breeding habitat by providing training work- shops to organizations and individual landowners and distributing information on best management practices. Scientists will guide adaptive management of the warbler’s habitat on demonstration sites, says Thousand Islands Land Trust’s director of land conservation, Sarah Walsh. “We want to have these sites open to other land managers and the public to show they can do this, too. What we’re hoping to do is plant these seeds of small habitat restoration zones across the area.” • Partnering to Aid Imperiled Warbler H ow can local and regional land trusts scattered across 11 western states partner on conservation projects? The question arose during a 2010 Land Trust Alliance leader- ship training program. For Andrew Mackie of the Land Trust of the Upper Arkansas in Colorado and Marie McCarty of Kachemak Heritage Land Trust in Alaska, the answer was in the air. Migratory birds depend on habitat spanning states and even continents during their cycles of breeding, nesting, migration and overwintering. In the largely arid West, rivers and wetlands are particularly critical habitat. Mackie, who has served as a wetland ecologist for the Audubon Society, sees opportunities for land trusts to partner with bird conservation organizations, volunteers and experts. “There are more plans for birds than any other organisms in the United States, but land trusts don’t always have the time and expertise to incorporate all of that research into their conservation planning and communi- cations,” he says. To increase connections between bird conservation entities and land trusts, Mackie and McCarty organized a post-Rally meeting in 2013 to launch “Wings Over Western Waters,” an initiative that brought 16 western land trusts together with representatives of the Pacific Coast and Intermountain West Joint Ventures, the Audubon Society, Partners in Flight, Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory and the Land Trust Alliance. The initiative’s goal is “to help land trusts with the science and planning needed to identify key species and habitats for protection, to form partnerships with bird conservation organizations, to contribute toward large-scale conservation initia- tives and to bring in ‘big’ funding to help local land trusts complete projects,” says Mackie. Since the meeting, informal partnerships have blossomed and a steering committee came together to plan next steps and reach out to more land trusts. Next on the horizon? “Wings is working with the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology on several possible projects to help land trusts in the West,” says Mackie. “Stay tuned.” • KATHERINENOBLET A golden-winged warbler For the Birds, Part Two Birds Link Western Land Trusts

- 8. 8 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org T he California Council of Land Trusts released an initial report in 2014 laying out sweeping changes facing the land conservation movement in coming decades. The “Conservation Horizons” report graphically outlines trends in demographics, culture and attitude, funding, land and resources and land trusts in the state. Among its findings: • By 2050, the state’s population is forecasted to grow by 35%. The population will be older, more urban and more diverse, with Latinos accounting for 47%. •The report points out a lack of interest in nature among children and a lack of access to parks for urban populations. For example, Los Angeles has just one playground per 10,000 residents. • Natural resources will face unprecedented challenges due to climate change and population growth under current land use practices. • Rising sea levels and the risk of large wildfires will pose economic, environmental and health threats. • The state is projected to lose 1 million acres of farmland by 2050. • Only 4% of the Millennial generation (born between 1980 and 2000) rank environment and conservation as the cause they care most about. “The cultural, demographic, political, financial and climate change trends are moving in very different directions,” writes California Council of Land Trusts Executive Director Darla Guenzler in the report’s introduction. “We should understand who our conservation programs are serving, with whom we are working, what additional lands we need to conserve, and reconsider our rela- tionships to people, to land and between people and land.” To advance that process, Guenzler conducted more than 60 presentations and discussions on the report over the past year. The council plans to release a final version of the report with recommen- dations for land trusts in March. See www.calandtrusts.org/conservation-horizons. • A s city-dwellers embrace growing their own food, they should also take steps to ensure that their fresh-grown produce provides more health benefits than risks. A study by Johns Hopkins University researchers found that many community gardeners in Baltimore were not aware of possible soil contaminants (ranging from lead and heavy metals to animal excrement) or how to reduce their risk of exposure. Vegetables raised in contaminated soils can sometimes absorb toxins, but there is also a risk of incidental exposure from contaminated soil around clean garden plots. Gardeners can inadvertently ingest contaminants on fingers or vegetables that have not been thoroughly washed (children are most at risk). Contaminants can also be inhaled or absorbed through skin, so gardeners should wear gloves while gardening or change clothing afterward. Eileen Gallagher, senior project manager for community gardens with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, shares other tips for safer urban gardening: • Test garden soil with a reputable lab before planting. • Know the history of the site. Some contaminants such as petro- chemicals aren’t detected through standard soil tests. • When building raised beds, take care to choose wood that is not chemically treated, and put down a thick water-permeable barrier before placing clean soil. • Cover pathways and garden soil with mulch or a cover crop. This helps to keep contaminants out of garden beds and prevents soil from being kicked into the air. • Avoid planting vegetables next to busy streets. Plant a vine on a fence or a hedge between the garden and street to buffer pollution. • Tests the Horticultural Society conducted with the Department of Agriculture indicate that soil with a pH of 6.8 or higher can inhibit vegetables from absorbing lead and other heavy metals. Find a guide to soil safety and other resources at www.jhsph.edu/ research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-a-livable- future/research. • Challenges on California’s Changing Horizon Safety First in Urban Gardens conservation N EWS PENNSYLVANIAHORTICULTURALSOCIETY An employee of the Health Promotion Council demonstrates how to prepare produce fresh from a community garden in Germantown, Pennsylvania.

- 9. www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 9 O n a frigid November day in 2014, 75 volunteers for the Greenwich Land Trust planted 400 descendants of the American chestnut tree that once populated eastern forests. An imported Asian blight decimated the American chestnut population by 1950. The American Chestnut Foundation has been working for decades to develop a cross-bred variety with American traits but the blight resistance of its Chinese cousin. Greenwich Land Trust’s seedlings are from that disease-resistant line, although American Chestnut Foundation spokeswoman Ruth Goodridge points out that cultivating and evaluating viable lines of the tree is a work in progress. “We have found several families that show excellent blight resistance. This is very good news, as it’s only a matter of time before the chestnut can be returned to our eastern forests,” she says. Greenwich Land Trust designated the 1.5-acre American Chestnut Sanctuary on a preserve in Connecticut, and solicited donors for a deer fence and other supplies. “People in the community got really excited about the story of the chestnut and what an important tree it was,” says Executive Director Ginny Gwynn. The American Chestnut Foundation relies on government and nonprofit partners like Greenwich Land Trust for test and seed orchards. “Test plant- ings like this not only provide valuable information to our science program, these plantings serve as educational opportunities to all who may visit the site,” Goodridge says. • Planting Hope for the American Chestnut R esearchers at the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry announced in 2014 that they succeeded in developing a blight-resistant American chestnut through genetic modification. Rather than cross-breeding the tree as the American Chestnut Foundation is doing, the American Chestnut Research and Restora- tion Project is infusing a blight-fighting enzyme from wheat into the tree’s genetic code. The enzyme detoxi- fies the deadly oxalic acid in the blight, according to the project website (www.esf.edu/chestnut). The method has raised concerns among organiza- tions that oppose genetically modified products. The American Chestnut Foundation supports this research as part of its philosophy of exploring all the options for restoring the tree, says foundation spokes- woman Ruth Goodridge. Transgenic trees would go through a minimum five-year regulatory testing process before planting outside of a controlled setting, she adds. • A Biotech Chestnut? GREENWICHLANDTRUST Two young volunteers help plant an American chestnut in Greenwich Land Trust’s American Chestnut Sanctuary. A first of its kind study by the U.S. Forest Service calculates that trees in the contermi- nous United States are saving more than 850 human lives a year and preventing 670,000 incidences of acute respiratory symptoms by removing pollution from the air (www.nrs.fs.fed.us/news/release/ trees-save-lives-reduce-air-pollution). Using computer modeling, the study considered four pollutants for which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has estab- lished air quality standards: nitrogen dioxide, ozone, sulfur dioxide and particulate matter. “In terms of impacts on human health, trees in urban areas are substantially more important than rural trees due to their proximity to people,” says one of the study’s authors, Dave Nowak of the U.S. Forest Service’s Northern Research Station. “We found that, in general, the greater the tree cover, the greater the pollution removal, and the greater the removal and population density, the greater the value of human health benefits.” Urban Trees Save Lives

- 10. 10 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org policy ROUN DUP This more proactive approach to engaging elected officials has taken some getting used to, but as 2014 drew to a close, the impact of land trusts’ advocacy engagement was already on full display—from the halls of Washington to ballot boxes back home. Take the example of one Ambassador, Andy Chmar of New York’s Hudson Highlands Land Trust. “Our Congressman, Sean Patrick Maloney, cospon- sored the conservation tax incentive right away, so it would have been easy to rest on our laurels,” Chmar said. “But as an Ambassador, I felt I could do more to encourage the congressman to act on the bill’s behalf. I spoke with him at local events and regularly touched base with his staff. After he voted with us on July’s charities bill, we made sure to thank him in the local press. The impact was dramatic. Democratic leaders strongly opposed our December vote on the tax incentive, but Rep. Maloney stood firm and took the initiative to lobby his colleagues on our behalf.” On the other side of the country, Alicia Reban of Nevada Land Trust was cultivating Senators Harry Reid and Dean Heller during the push for the incentive. There are land trusts in every state across the country, and that local presence can be a mighty force on Capitol Hill. In the spring of 2014, the Land Trust Alliance launched the Land Trust Ambassadors initiative to harness that power. Over the past year, more than 100 land trust leaders have taken the pledge to become Ambassadors, making a commitment to cultivate relationships with their members of Congress so that when the time comes to ask for something, those members will listen. Relationships that Bear Fruit Texas land trust leaders meet with staff for Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee at the 2014 Advocacy Day. DJGLISSON,II/FIREFLYIMAGEWORKS BY Sean Robertson As part of a partnership with Feeding America, Alliance Executive Vice President Mary Pope Hutson presented a bag of apples from a conserved orchard to incoming Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch (UT). OFFICEOFSENATORORRINHATCH

- 11. www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 11 “We have worked with congressional offices on a number of occasions over the years,” says Reban, “but Nevada Land Trust understood how important this incentive is for ranchers and other landowners across Nevada and chose to step up our involvement around this issue. The Alliance asked for more in the fall, when it became clear we needed Senator Reid’s help to get the bill to the floor for a vote. So I was glad to take the Ambassadors pledge and invest in stronger relationships with our delegation.” She explains how NLT “shared examples of what we’d been able to accomplish when the incentive was in place, as well as what lands and waters were at greater risk without it in the near future.” NLT made sure to thank Nevada’s members of the House for their support in passing the bill in July. Now the stage is set for 2015. “We are beyond pleased with the support of the Nevada del- egation on this issue—and thrilled that our own Senator Heller has introduced conservation tax incentive legislation in the new Congress,” says Reban. “Nevada Land Trust is looking forward to taking Senator Heller and his staff out on one of our project sites to see first-hand what a difference the incentive can make—and to celebrate his leadership on this issue.” In December we fell eight votes short of the 66% we needed, but we exceeded expectations and, thanks to Ambassadors like Andy Chmar and Alicia Reban, we enter the 114th Congress with fresh sponsors and newfound enthusiasm for the Conservation Easement Incentive Act. Check out “Mustering a Mighty Voice” on page 18 for the full story. You can take the pledge to become an Ambassador at www.lta.org/ambassadors. Voters Approve $13.3 Billion for Land While the Ambassadors initiative has a federal focus, the Alliance also hopes to inspire greater advocacy engagement at all levels of government. Toward that end, the Alliance collaborated with Trust for Public Land’s conservation finance program to make $100,000 in grants to support local land trust participation in state and local ballot measure campaigns. As part of this partnership, the Alliance also retained Mark Ackelson, president emeritus of the Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation, to advise land trusts on ballot measure strategy. He notes, “Our collaboration demonstrates the effective role that even small land trusts with limited resources can successfully play in engaging their communities to create much-needed local funding for their missions. These land trusts developed new partnerships and capacity to enhance their work that will have lasting benefits forever.” Of the 10 campaigns we actively supported, eight passed, gener- ating a remarkable $11.4 billion for land conservation. These cam- paigns helped to make 2014 a record year at the ballot box. Voters from across the political spectrum came out to approve 35 measures, providing $13.3 billion to protect the places you love. Learn about the approved measures and our plans for 2016 at www.lta.org/statefunding. Join Us for Advocacy Day How will you celebrate Earth Day this year? We hope you will join us on April 21–22 for the fourth annual Land Trust Advocacy Day. P lease welcome Director of Advocacy Andy McLeod to the Alliance policy team. Andy manages and strengthens our national advocacy network and encourages engagement with new partners and members of the land trust community. Andy will also serve as regional advocacy lead for the South- east, where he will capitalize on his many contacts from his work as head of government relations for The Nature Conservancy and the Trust for Public Land in Florida, where he helped achieve reauthorization of the $300 million Florida Forever program. “Many of you already have had the opportunity to work with Andy as a consultant to the Alliance over the past few months, and I am enthusiastic to make him a permanent member of the team,” said Executive Vice President Mary Pope Hutson. “His understanding of how to mobilize relation- ships coupled with land trusts’ passion and teamwork will be key to our victories in Congress.” A native New Englander, Andy previously served as director of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and as a press secretary for U.S. Senators John Chafee (RI) and Lowell Weicker (CT). You can reach Andy at 202-800-2239 or amcleod@lta.org. • Meet Andy McLeod DJGLISSON,II/FIREFLYIMAGEWORKS Andy McLeod (left) and Sean Robertson Advocacy Day is an exciting two days of issue briefings, inspiring reception speakers, networking events and meetings with congressional delegations on Capitol Hill. Land trust leaders develop the skills and confidence to advocate for conservation priorities with their elected officials. The relationships initiated at Advocacy Day will result in a stronger political relevance for private land conservation and advance the tax incentives and funding that help you save the places you love. You will also have a great head start toward becoming an Ambassador, joining a community of land trust leaders who have taken a pledge to build relationships that support federal funding and tax incentives for land conservation. Learn more and register at www.lta.org/advocacyday.

- 12. 12 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org Meet our new Board Chair voiced sea and sky. One such place is on the south coast of Massachusetts called Allens Pond, a Mass Audubon sanctuary. Q. How did you come to love birds? A. When I lived briefly in California I found myself becoming a passionate—but very amateur—birdwatcher. I love birdwatching as a way to engage people because you can do it at so many levels—casually to very seriously— and you can do it anywhere in the world. Most important, it makes you look—really look—at things around you. Observation is an underappreciated skill in life. Q. What made you laugh really hard recently? A. I just spent a few days with a group of women friends I’ve known for 30 years. We laugh very hard with each other over shared memories, stories of awkward moments and other silly stuff. We can be pretty serious too. Q. Tell us something surprising about yourself. A. I love yoga! It’s both peaceful and non- competitive, but also physically pushes you. Q. What individual in the world of conser- vation has most inspired you and why? A. There are two. One is Jane Goodall. Her personal story is amazing, and her dedica- tion to making positive change in the world is inspirational. The other is Edward O. Wilson, who has provided the world with both compelling inspiration and substantial knowledge about biodiversity. Q. Your son now works for a land trust! What advice did you offer him, and what would you tell other young people who are considering a career in conservation? A. Follow your passion and commit with your heart to the mission. But make lasting change by also gaining concrete skills that can help you be successful— science, law, finance, marketing, etc. Commit to finding real solutions to make the world a better place. Laura Johnson joined the Land Trust Alliance Board of Directors in 2011, and this year becomes chair. She is past president of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, and prior to that worked for The Nature Conservancy. She graduated from Harvard University and received a J.D. from the New York University School of Law. Q. What was your first eye-opening experience with nature? A. Growing up in New England I roamed around the woods a lot as a child. But the biggest eye-opener was going to summer camp in Colorado where I experienced the mountains and the backcountry for the first time. I think that’s when I fell in love with nature. Q. Why did you decide to join the Land Trust Alliance board? A. I was honored to be approached about my interest in serving on the board a few years ago. I care passionately about land conservation, about the well-being of our children and the future of our communities. The Alliance is effective, strategic, focused—it’s making a difference for land trusts and land conservation all across the country. It’s great to be a part of that through serving on the board. Q. What do you hope your legacy will be as chair? A. To strengthen the organization so that it can continue to support the important work of land trusts around the country. Q. What is your favorite outdoor spot? A. I have so many…but I would say it’s an uncrowded beach, where I can watch shorebirds feeding, and listen to terns calling, and watch the changing Laura Johnson with birding binoculars at the ready TOOEY ROGERS

- 13. RISKS CHANGE Our New Risk Management Tool Lets You Easily Customize a Plan for Your Land Trust. Keep your risk management plan in the right proportions and be ready for new land trust opportunities with the free risk management course on The Learning Center*. It features a fun-to-use interactive tool to design your plan, which can then be updated and shared any time! http://tlc.lta.org/riskmanagement and now your plan can too! IT’S ENTERTAINING—quick video provides orientation to the benefits of risk management IT’S FUN—play with the risk sliders to test your tolerance for common land trust risks IT’S FLEXIBLE—take the course at your pace, whenever you want, wherever you want IT’S A BONUS—earn a $1 discount off each easement and fee preserve insured with Terrafirma, when your written plan is completed *The Learning Center is a service offered to Alliance member land trusts and partners, and to individual members at the $250 level and above. This easy-to-use tool walked us through the process of assessing our overall risk. We developed an effective plan that's been invaluable to my organization. —Erin Knight, Upstate Forever (SC)

- 14. 14 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org The Ever-Changing Life of a Circuit Rider The Alliance’s traveling circuit riders find that no day is ever like the one before. BY Kirsten Ferguson hat’s a typical day like in the life of a circuit rider? And what, exactly, is a circuit rider? It’s a romantic-sounding title given to a handful of Land Trust Alliance specialists who travel around their regions, providing assistance and support to small and all-volunteer land trusts. It turns out that there really is no typical day for a circuit rider. Connie Manes, Land Trust Alliance circuit rider GREENBOMB STUDIOS

- 15. www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 15 Connie Manes covers the territory of Connecticut, a moderate-size place geographically, but one not always easy to get around. “I drive over mountains and back roads quite a bit,” she says in a call from her home in the Berkshire Mountain foothills on a day off from traveling. “The whole idea and name of the circuit rider program are appropriate. I’ll show up at a meeting and people will ask me where my cowboy hat is.” The land trusts that Manes assists typically have few, if any, paid staff and often lack a permanent meeting place. “I go to homes, to senior centers, to libraries, small rented offices, town halls, a space above a store in the middle of a town. I go to one spot on protected land—the land trust’s headquarters is on top of this beautiful hill on its signature preserve. Or sometimes I meet people for coffee.” Manes was the very first circuit rider in a program launched after a 2012 Alliance national assessment studied the challenges and needs of all-volunteer land trusts. “One of the conclusions of the report was that all-volunteer land trusts have just as much interest as other land trusts in professionalizing, but they can’t always avail themselves of all the opportunities for learning because their board members are busy during the day at their daytime jobs,” Manes says. For Kevin Case, the Alliance’s Northeast director, Manes was part of the solution—someone who could bring training, services and support to the very doorsteps of Connecticut’s many all- volunteer land trusts. With a background in nonprofit law and public administration, Manes had served as a part-time executive director for Kent Land Trust and as a consultant in strategic plan- ning, grant-writing and performance improvement. “These smaller land trusts don’t have a lot of bandwidth to go to conferences,” says Case. “We found they were feeling isolated and would welcome more interaction. We decided the best way to engage them is to go to them. We’d work with them one-on-one to help them deal with risks. Do they have the capacity to defend the lands they’ve protected in the long term? We wanted to figure out ways to get them the resources they needed.” Moving Mountains “Kevin said recruiting might be slow,” Manes recalls of the circuit rider program’s start, when they first put the word out seeking land trusts to sign up. “Within a week, we had 10 land trusts in Connecticut. We were like, ‘Who would want to do this?’ And everyone wanted it.” By 2013, Manes was working with 10 land trusts in Connecticut and five in Rhode Island, helping them with everything from organizational assessments and record-keeping to strategic planning and establishing eligibility for Terrafirma, the member-owned insurance program that helps land trusts defend their conserved lands from legal challenges. Case and Manes noticed another benefit of the program: It was bringing land trusts together through events and workshops The protected Hoover property along the Shenandoah River in West Virginia lies in circuit rider Don Owen’s territory. DJ GLISSON, II/FIREFLY IMAGEWORKS

- 16. 16 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org where they could swap stories and build connections. “The thing I find extremely valuable about it is you can tell how it’s strengthening ties and boosting morale,” says Case. In Connecticut, six neighboring groups even decided to join forces and share services in their own collaborative: the Northern Fairfield Land Trust Coalition. In 2015, the plan is for Manes to focus on working with the growing number of Connecticut groups that want to take on the land trust accreditation process (she now focuses solely on the Nutmeg State and no longer covers Rhode Island). Out of 137 land trusts in Connecticut, only 11 have achieved accreditation, so there is “a lot of potential” to increase those numbers, while at the same time there “seems to be a lot of energy around accreditation” in the state, Manes says. Watching land trusts grow, and beautiful places in her home state of Connecticut become protected, more than compensates for the frequent travel that the job entails, Manes says. “For me, it’s the people. It’s the dedica- tion of the folks that serve on these land trust boards. They work so hard. They pour their time and hearts into their organizations. To be able to help them is very rewarding.” It’s also a great investment for the land trust movement, she believes. “It may seem like a lot to have one person out there just serving 10 land trusts, but I think the return on invest- ment is huge for this program,” she says. “The land trusts that are involved can go so far by participating. They can move mountains.” A Volunteer Movement The Appalachian Trail that runs through Connie Manes’ town in Connecticut connects her in a sense to Don Owen, the Alliance’s circuit rider for the Potomac River watershed in Virginia, Maryland and West Virginia. Owen spent 23 years working on the Appa- lachian Trail as an environmental protection specialist and resource management coordi- nator. He also served as the executive director of the Land Trust of Virginia for six years before “retiring” in 2014 and taking on his new challenge as a circuit rider. Like Manes, Owen most enjoys the time he spends with people involved in the all- volunteer and small land trusts. “Working with volunteers has always been incredibly satisfying for me,” he says from his home in Virginia. “It’s what I did most of my career on the Appalachian Trail, and it’s what I’m doing now.” “Volunteers at land trusts are in this busi- ness for all the right reasons—because it’s something they care about,” he says. “They’re devoting their time and money and energy to saving land. I meet some pretty neat people.” He likes the variety of the job, too—with every day a different place or a new chal- lenge. The Potomac River watershed is vast, covering 15,000 square miles—about nine- and-a-half million acres. The landscape has “got a little bit of everything,” he says. “It’s got mountains, beautiful sub-watersheds, the Chesapeake Bay.” And historical signifi- cance. “The Civil War was fought here. The region has an incredible wealth of natural and cultural resources worthy of protecting.” Over the course of a week, Owen met with land trusts working on organizational assessments and on accreditation documen- tation. He connected with Grant Smith, president of West Virginia’s Land Trust of the Eastern Panhandle, and they visited an easement on farmland along the Shenan- doah River. Owen helped the group by organizing workshops on how to recruit and retain board members and attract land- owners in the position to donate easements, Smith says. The workshops that Owen set up were especially helpful because they focused on the needs of land trusts without any staff, says Smith. “We’ve also had the benefit of having Don at board meetings where we worked through sections of the Alliance’s Assessing Your Organization, where he has been extremely helpful with practical, locally relevant suggestions.” After the president of Maryland’s Patuxent Tidewater Land Trust died and its director moved away, volunteers Frank Allen and his wife were faced with being the land trust’s only active local presence. They eventually found an energetic new director, and Owen helped them to build an active board and work toward accreditation. “Don acts as a connector to Alliance corporate knowledge, sharing success stories among the land trusts in his area and bringing Alliance expertise directly to us. Many of us are not in the position to attend the annual Rally. For us, it is hard to get a farm sitter,” says Allen, the current board president. Ultimately, the hardest part of any circuit rider’s job may be that there are not enough of them to go around. “It’s not easy work,” Owen says. “But most of the groups I’m working with recognize there’s a limit to what I can do.” Overall, he says, the hard work pays off. “I feel like I’m part of a collective movement that makes the world a better place. It’s very satisfying.” KIRSTEN FERGUSON IS A FREELANCE WRITER IN NEW YORK. 16 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org Don Owen, Land Trust Alliance circuit rider for the Potomac River watershed DJGLISSON,II/FIREFLYIMAGEWORKS

- 17. www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 17 A Chat with More Riders In addition to Connie Manes and Don Owen, Alliance circuit riders Lisa Smith and JoAnn Albert of E-Concepts, LLC jointly cover the western half of Pennsylvania, while Henrietta (Henri) Jordan operates in the state of New York. Here, they talk about life on the road, what they accomplish and good friendships. What are the main challenges that you help land trusts with? “The metaphor I like to use is I’m kind of like an outrigger on a canoe. I try to help keep things stable—keep them going in the right direc- tion and be a go-to person for them. I try to get them to know that someone really cares about what they’re doing and be a friendly face encouraging them and making them aware of how much they’ve achieved. To me, it’s a miracle that these small volunteer groups are able to do as much as they do.”—Henri Jordan How do you pass the time in the car while traveling? “We get a lot of work done! One of us drives while the other takes notes, and we are very good friends so lots of time is spent gabbing about life. Oh yeah, and eating together is one of our favorite pastimes.”—Lisa Smith What’s a typical week like for you? “A typical week for me will involve coaching an executive director through some sticky board issues and talking with a board president about how to lead more effectively. Or talking with a board president about an ease- ment violation that they’re working through, helping a land trust write a job description and handle a budget or providing model policies and procedures and assisting with questions about accreditation.” —Henri Jordan What do you like best about the landscape of the territory you cover? “Exploring and enjoying the natural areas of our state has been a part of our lives since we were children. I enjoy the amazing variety of landscapes in western Pennsylvania. We have the Lake Erie shoreline, boulder-filled stream valleys and unique geologic features that resulted from a glacial past, three large and varied river systems and the beau- tiful southeastern mountains. Within an hour or two of Pittsburgh, you can be in a completely different environment.”—JoAnn Albert How did you end up working as a circuit rider? “In 2008, as part of our company’s business plan, we presented an idea to a funder on providing technical assistance to land trusts in our region. We were excited to receive funding support, and approached the Alliance to be our nonprofit partner. Our concept fit perfectly with the circuit rider program that the Alliance was implementing in other areas.”—Lisa Smith Is there anything that makes your circuit rider program unique from the others? “We have a large geographic area. The land trusts we work with are separated by distance and they primarily connect with groups in their smaller region. One of our goals was to provide opportunities to bring the groups in the larger region together. The large geographic area also results in different land protection goals, from farmland to urban green- ways to forest preservation to biodiversity protection.” —JoAnn Albert What do you enjoy most about being a circuit rider? “Seeing small underserved groups, with the help of the Alliance and the New York State Conservation Partnership Program, become stronger and more effective is rewarding. The investment in time and resources pays off. My favorite thing is also the relationship with the people— seeing their passion and their dedication and their love for their commu- nities and how hard they work. It’s very humbling to see that.” —Henri Jordan Top, circuit rider Lisa Smith and bottom, circuit rider JoAnn Albert

- 18. 18 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org Mustering a MIGHTY VOICEHow the Land Trust Alliance rallied its members and partners to fight for the tax incentive BY Christina Soto

- 19. www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 19 Incentive 101 After his tenure as senior policy advisor at The Nature Conservancy, Shay joined the Land Trust Alliance in 1998. He has been working on the tax incentive in its various forms for more than a decade. Splitting his home life between Washington, D.C., and Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, while in town, Shay lives only a mile from the Capitol. “One of the most effective ways we increase the pace of land conservation is through tax incentives that help land- owners afford to choose conservation over development,” says Shay. “Land trusts have been enormously successful in using these incentives to protect special places across America. When incentives are in place, easement donations increase and more land gets saved.” In July, the House passed a bill to make permanent the enhanced tax incentive and other charity provisions with a bipartisan vote. The Alliance celebrated with its members and partners, but the victory was only part one. The measure had to go to the Senate. Although the Senate did not take up the legislation before the November election, it promised to deal with the incentive and 60 other expired tax provisions after Election Day, in a lame-duck session. The Senate wanted to simply extend the provisions for 2013 and 2014, but the House wanted to make some—including the easement incen- tive—permanent. That was the Alliance’s goal, and its policy team—Hutson, Shay, Andy McLeod, Sean Robertson, Bethany Erb and Bryan David—geared up to campaign intensively for it. Mobilizing for the Big Fight The incentive has been consistently selected as a top policy priority by Alliance members for years. Much work had been done by the Alliance throughout 2014 leading up to the end-of-year push. In late October, the organization had hired on a temporary basis Andy McLeod, a veteran conservation lobbyist and policy specialist, to help win permanence for the incentive (he has since become permanent, see p. 11). “We hired Andy to oversee all the outreach and coordination with our regional policy leaders, Russ and myself, as well as to be the key regional policy lead in the Southeast as we entered the last 60 days of the congressional calendar,” says Hutson. The Alliance created a toolkit of outreach materials, arming regional advocacy leads who engaged one-on-one with legions of land trust advocates in key districts across the country. Many of these advocates had a head start, having previ- ously taken the Land Trust Ambassador pledge to proactively build relationships with their members of Congress. Communications was a huge part of the mobilization for the incentive. “Before the House vote in July, we had hired a commu- nications company to reach land trusts in key districts, place op-eds and use social media strategically,” says Elizabeth Ward, communications director for the Alliance. “During the lame-duck session, D.C.-based HDMK worked with Joshua Lynsen, our media relations manager, to craft and pitch content to many outlets.” And as land trust people around the country called their representatives to advocate for the tax incentive, staff members of the Alliance were also making calls to their reps. “We weren’t asking our members to do anything that we weren’t doing ourselves,” says Ward. “We practice what we preach.” Apples, Ads and Allies With Thanksgiving approaching, the Alliance saw an opportunity to tie the incentive to a message that would resonate with all people: food. But how to convey the message? That’s when Western Advocacy and Outreach Manager Bethany Erb’s suggestion came into play: Deliver apples to every member of the Senate. “Feeding America, the great charity that feeds America’s hungry through its network of food banks, suggested we contact a Virginia farm that donates apples to a local food bank at the end of each season,” says Ward. Serendipitously, Crooked Run Orchard has 41 acres held in a conservation easement by the Land Trust of Virginia. continued on page 22 Opposite: The Alliance policy team, clockwise: Mary Pope Hutson, Russ Shay, Andy McLeod, Bryan David, Bethany Erb, Sean Robertson DJ GLISSON, II/FIREFLY IMAGEWORKS R uss Shay didn’t wake up early on the morning of the vote on the charities bill that included making the conservation tax incentive permanent. He didn’t have to because he hadn’t slept. The vote, coming just hours before Congress adjourned in 2014, was the culmination of two action-packed, all-hands-on-deck months of mustering allies and resources in a feat of organizing that outdid anything the Land Trust Alliance had ever done before. The fight enlisted eight of America’s top charity organizations and their powerful memberships, land trust people around the country, allies in Congress and every staff member of the Alliance. Shay, the Alliance’s director of public policy, and Mary Pope Hutson, executive vice president and head of the policy team, stood at the center of the vortex and waited for the vote.

- 20. 20 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org land we love PHOTOGRAPH BY TOM COGILL

- 21. www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 21 chronicling a Community’s Roots “There are places in our country where a handshake is still more important than a contract, where caring for land is still more important than being a millionaire. One of those places is the Cacapon and Lost River Valley.” –Peter Forbes T he Cacapon and Lost River Valley in West Virginia is still dominated over large areas by functional and largely intact natural ecosystems. Its forests, which make up approximately 85% of the watershed, are responsible for supporting its unparalleled biodiversity. Founded 25 years ago, the Cacapon and Lost Rivers Land Trust, an accredited land trust, has worked since its inception to forge strong relationships with valley landowners who care deeply for their land and who have a desire to preserve traditional land uses, such as farming, logging and hunting. The trust has focused its work on protecting connected parcels with conservation easements—forming agricultural, forested and wildlife hubs and corridors that are close by or connected to public lands. The trust’s recent book Listening to the Land: Stories from the Cacapon and Lost River Valley (West Virginia University Press, 2013) tells the story of the connection the people of this valley have with the land and chronicles the community’s dedication to land preservation—dedication like that of Ralph Spaid, who turned down millions from developers saying, “It is more than a farm, it is a living landscape of memories for future generations.”

- 22. 22 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org Two policy interns were asked to make the run to pick up 1,000 apples (one other farm was involved), so in a truck borrowed from Erb and with a blank, signed personal check from Ward, Jordan Giaconia and Kody Sprinkle set off on their own excel- lent adventure. “I was thrilled to get a chance to get out of the office and onto the land we strive to protect,” says Jordan. The apples were bagged with a letter from the Alliance and Feeding America stating the benefits of the easement incen- tive and the food donation incentive, both of which “are commonsense approaches that help feed Americans while safe- guarding the special places that define our heritage, character and people. We urge you to make these incentives permanent.” Delivery occurred the week of November 17, with a few bags of apples personally delivered to particular champions of the incentive, such as Senator Debbie Stabenow (MI) and Giaconia’s senator, Chris Murphy (CT). The moment was captured by a photographer from Roll Call. “Senator Murphy was incredibly personable and it really gave me a sense of civic pride being from a state that not only supports land conservation but has strong elected officials to make it happen,” says Giaconia. Around the time of the great apple advance, the Alliance began to fight on another front, through the print media, specifically Politico, the policy magazine widely read on Capitol Hill. “We ran three ads, deciding to do each one as our strategy evolved and as the situation on the Hill changed day to day,” says Ward. The last ad carried a unified call for action from the Alliance and eight charities that had joined the fight: Feeding America, United Way, Council on Foun- dations, The Jewish Federations of North America, Forum of Regional Associations of Grantmakers, Independent Sector, National Council of Nonprofits and Council of Michigan Foundations. All but a few, like Independent Sector, were new allies to the Alliance. A powerful coalition had formed. It seemed to be working. “There were discussions going on between the House and Senate on a big package dealing with not just three separate charity incentives, but all the other expired tax provisions, and things seemed to be going our way,” says Hutson “On November 25, we were told there was a deal and that we were going to like it.” The next message, however, came from President Obama’s staff, indicating that he would veto the bill because it was not paid for. “At that point everybody started tearing out their hair, although I don’t have any left,” says Shay. “All the tax pundits said we had lost. And although we at the Alliance felt terrible, we didn’t give up. There had to be a way.” Not the End of the Story After the veto threat, Shay sat in his office thinking how the big package of tax extenders was not going to make it through. But what if it were narrowed down to just the charity incentives? “The first person we went to to ask about this was Congressman Dave Camp (MI) because we knew he cared about our issues,” says Shay. “And the reason he cared is because Glen Chown, executive director of the Grand Traverse Regional Land Conservancy in Michigan and a Land Trust Ambassador, had taken the time over the years to form a strong and personal rela- tionship with the congressman.” The atmosphere in Congress was chaotic. After elections, members were clearing out of their offices and some didn’t even have offices anymore. In the midst of this, Rep. Camp, continued from page 19 For people hungry today For people committed to protecting and preserving the environment For older Americans who want to give back to their communities Vote YES on the Supporting America’s Charities Act (H.R. 5806). Help every community meet urgent needs now. The third ad created for Politico featured the logos of the nine charities who were part of the coalition. Russ Shay meets with Senator Debbie Stabenow (MI), a good friend of land conservation because of Land Trust Ambassador Glen Chown, who has cultivated a solid relationship with her and Rep. Dave Camp as well. ELIZABETHWARD A photographer from Roll Call captured Alliance policy intern Jordan Giaconia’s apple delivery to Senator Chris Murphy (CT).

- 23. www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 23 who was preparing to retire, told Chown, “Yes, I’ll help.” “He offered to present a bill with just three charitable provisions—food, easements and the IRA charitable rollover—to the lead- ership under a suspension of rules,” says Shay. “That means that the debate is limited to an hour; there are no amendments; and it needs two-thirds of the members for a winning vote.” It was a Hail-Mary move, but everyone was willing to try it. Hutson describes how Rand Wentworth, Alliance president, rolled up his sleeves and got on the phone. “He really helped pull the group of charities together by talking with the leaders of those groups. He knew many of them, and had worked with them earlier in the lame duck. It was another testament to the power of building relationships.” Hutson says everyone in the charities coalition worked together very well. “We were under a deadline so there was no time to quibble about anything. We had to make up our minds quickly to get things done.” And things were getting done, not just in D.C. but around the country. “Our land trust leaders were making calls, as were people in the United Way chapters, people involved with food banks, community foundations, etc. They were all advocating for the charities bill,” says Shay. He adds, “By the time the day of the vote came, we’d done everything we could do. We knew what was going on and we knew who was doing what. Most of our power comes through our members and their relationships with their representatives. We had tapped that power and demonstrated that we could not be ignored.” The vote came. Eight votes short of passage. A collective groan went through the Alliance offices. “Unlike in the movies, the good guys didn’t win,” says Shay. “But we lived to fight another day.” The incentive was only made retroactive for 2014, expiring on December 31. Wentworth sent a message to Alliance members and supporters after the vote: “While we did not achieve permanence in this Congress, we have much to be proud of, and we are better positioned to make our incentive permanent in the 114th Congress. With your help and support we built powerful coalitions of charities and conser- vation organizations, and we saw members of the land trust community take up this cause on Capitol Hill. Most important, we made ourselves heard on the Hill—and we have many friends and allies on both sides of the aisle.” Shay talks about the work ahead. “I’m a very practical person. For lots of Americans there are many more important things than conservation on their minds. We must never forget that. So we have to reach out and get more people to understand land conserva- tion. We have to continue talking to our representatives and building those relation- ships. Friends don’t just happen. We have to make friends.” Wentworth sent one last message to his staff before the holidays: “I call what happened this past year a victory. Staff throughout the organization pulled together on the incentive. It’s the entire organization that has brought its combined work, efforts and belief that this is something we can do. We continue until the job is done.” CHRISTINA SOTO IS EDITOR OF SAVING LAND. SHE DEDICATES THIS ARTICLE TO ALL THE STAFF MEMBERS OF THE LAND TRUST ALLIANCE. On December 20, 2014, the Columbia Land Conservancy (CLC) and the Alliance hosted a special event in Columbia County, New York, with Senator Chuck Schumer (NY) as part of the easement incentive strategy of building relationships with key officials. Senator Schumer is one of the most senior Democrats on the Senate Finance Committee and although Eastern Advocacy and Outreach Manager Sean Robertson had met numerous times with his tax counsel in D.C., few in the New York land trust community had a direct relationship with him. This fall’s negotiations presented Robertson and his team of Land Trust Ambassadors in New York a timely opportunity. “We started our outreach around Labor Day, meeting with his state director in Albany,” says Ethan Winter, Alliance New York conservation manager, who coordinated the event working closely with Robertson and Ambassadors Peter Paden of Columbia Land Conservancy and Andy Bicking of Scenic Hudson. “We filled CLC’s boardroom with easement donors, board members and directors from 10 land trusts.” During the event, Senator Schumer announced he would focus his efforts on making the incentive permanent. In the months ahead, the Alliance hopes to help Senator Schumer meet other New York land trust leaders and visit with landowners across the state. In early February, our congressional champions, Senators Dean Heller (NV) and Debbie Stabenow (MI), and Representatives Mike Kelly (PA) and Mike Thompson (CA), reintroduced the Conservation Easement Incentive Act. As this issue went to press, the House successfully voted 279-137, demonstrating a supermajority (67%) of support on H.R. 644. For current information, go to www.lta.org/policy. BUILDING MOMENTUM FOR 2015 Senator Chuck Schumer (center) with Greene Land Trust board member Rich Guthrie (left) and board president Bob Knighton TOMCROWELL

- 24. 24 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org Some of these groups today find them- selves at a crossroads, facing financial constraints or declining congregations, and their land is an important factor in the problem-solving. Consider Catholic orders, which have aging memberships, fewer younger people joining the ranks and sky- rocketing healthcare costs. As these orders look ahead and weigh financial realities, development of their land presents an ever- enticing option. Enter land trusts, which play a key role in helping faith-based organizations under- stand their options vis-à-vis land. Land trusts are uniquely positioned to advise religious entities about ways to address their financial needs while also remaining true to the land entrusted to their care. Understanding the Context Among religious organizations—and particu- larly Catholics—there has been an enormous shift in ecological consciousness in recent decades. The change began in the 1980s when Catholic orders began to understand and recognize the observable sciences. “There was a shift in understanding about how the universe came to be,” says Chris Loughlin, WHEN YOU THINK OF RELIGIOUS ORDERS, typically you don’t think about land. But the fact is that many own significant real estate: urban parcels, farmland, forests, camps along rivers, retreat houses and oceanfront property. These lands were often gifted to religious groups (or purchased at minimal cost) more than a century ago, and they have remained intact through the years. HIGHER GROUNDWhere Land Trusts and Religious Groups Meet By Edith Pepper Goltra Mass Audubon’s Bob Wilber photographed daughter Lindsey in Great Neck, protected through a project with the Congregation of Sacred Hearts. “I love this photo because of the obvious joy of being outside on a beautiful piece of land,” says Wilber. BOB WILBER With assistance from Sheila McGrory-Klyza

- 25. a Dominican sister and director of Crystal Spring Earth Learning Center. “This propelled religious orders to respond—to recognize that they are an intimate part of the Earth and not superimposed on it.” The reality of climate change also began to emerge at this time. The issue mobilized not only scientists and political leaders but churches and faith-based organizations, as well. As Pope John Paul II said on World Day of Peace in 1990: “We cannot interfere in one area of the ecosystem without paying due attention both to the consequences of such interference in other areas and to the well-being of future generations.” When it comes to land, the missions of religious groups and land trusts have begun to converge. While religious orders were originally focused primarily on the welfare of people, they are now broadening their focus to consider care of the Earth and all living things. Land trusts are expand- ing their focus to include diverse members of their communities in the larger social context of conservation. Already several stories are emerging of land trusts that have partnered with religious groups to save land. An Interconnectedness In the middle of Kalamazoo, Michigan, lies a 60-acre natural oasis of spring-filled fens, wildlife, wetlands and forests known as “Bow in the Clouds Preserve.” For more than four decades, this beautiful property has been lovingly cared for by the Sisters of the Congregation of St. Joseph—and spe- cifically by Sister Virginia “Ginny” Jones, a passionate environmentalist and naturalist. She explains how the name “Bow in the Clouds” signifies a Biblical covenant. “The covenant says, in essence: God not only cares about us, he cares about all creation. For me the land was the place where we could encounter God’s creation. We were called to care for it.” In the early 2000s, aware of the con- gregation’s aging membership, Sr. Ginny contacted the Southwest Michigan Land Conservancy (SWMLC). “I realized that I was physically tired. I could see that the land just wasn’t going to be maintained anymore,” she says. Despite some press- ing financial needs, the Sisters decided to donate the land outright to SWMLC. “This order of nuns completely blew away my vision of who nuns are,” says Nate Fuller, SWMLC’s conservation and stew- ardship director. “They love the land. There is a sense of interconnectedness. They would go and reflect and meditate on the land, hold drum circles. They see their mission as stewarding God’s creation.” The land trust, for its part, has tried to live up to the congregation’s high standards. It has conducted habitat rehabilitation, established public access and maintained and improved almost a mile of footpaths, including a 1,000-foot boardwalk built by Eagle Scouts under Sr. Ginny’s supervision. An important part of the the vision is that much of the site will be universally accessible to visitors of all abilities. “There is a need in our area to help make nature accessible to everybody, regardless of physical mobility, sight impairments or other challenges,” says Fuller. “We are also working with community leaders to identify how the preserve can be a resource for people of different cultural backgrounds in the surrounding neighborhood.” Sr. Ginny is very pleased. “The land conser- vancy has taken the dream I had and they’ve moved it beyond what I could have even hoped.” The Essence of Humans Since the early 1940s, the Congregation of Sacred Hearts in Wareham, Massachusetts, has operated on 120 acres of woods and “The land conservancy has taken the dream I had and they’ve moved it beyond what I could have even hoped.” –Sister Ginny Jones www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 25 A beautiful meadow in the Bow in the Clouds PreserveThe Sisters of the Congregation of St. Joseph working in the Bow in the Clouds Preserve SOUTHWESTMICHIGANLANDCONSERVANCY SOUTHWESTMICHIGANLANDCONSERVANCY

- 26. 26 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org marshland on Great Neck near Cape Cod. Several years ago, the congregation recog- nized that its religious retreat center needed to be upgraded and expanded, but it didn’t have the funds to do the work. Selling the land, it realized, was probably its best option for generating cash. At a 2010 chapter meeting—involving priests from nine different countries who had gathered in Massachusetts—a real estate developer proposed buying a portion of the Wareham property. But according to Father Stan Kolasa, it just didn’t feel right. “This is holy ground here,” Father Stan says. “The thought of having condos on this land violated my own sensitivities. What I heard inside myself was something from the Bible: What you receive as a gift, you give as a gift.” Bob Wilber, director of land conservation with Mass Audubon, was also at the 2010 meeting. He stood up and offered a different approach. He proposed placing a conserva- tion restriction over the property (paying the congregation $3.6 million for it, a frac- tion of its value). This approach would allow the Brothers to retain ownership of the land and continue operating their religious retreat center. Although there was some disagreement among the gathered priests, ultimately this proposal prevailed. “This project touched the very essence of us as humans,” says Father Stan. “To give up potential financial returns on land is a total act of faith. But in the end, we felt that the integrity of the land was greater than its financial value.” Championing a Small Creature It wasn’t land that brought Birmingham’s Faith Apostolic Church and the Freshwater Land Trust together, but rather the discov- ery of a tiny endangered fish, known as the watercress darter, in a limestone spring in the church’s backyard. What made the partnership so unusual was that Faith Apostolic is “not your tra- ditional conservation demographic,” says Wendy Jackson, executive director of the Freshwater Land Trust. “In fact, this inner- city church had always had a disconnect with conservation.” But the fish changed everything. “When I walked into the church,” says Dr. W. Mike Howell, professor emeritus, Samford University, “there were 20 deacons standing there, along with Bishop Heron Johnson, the pastor. They looked at me and said, ‘How can we help?’” Since that day, Bishop Johnson, now in his mid-90s, has been a champion for the fish, believing that God put the darter on the church’s property for a reason. He has instilled the importance of protecting this rare habitat in his congregation, relying on them to continue his conservation work and carry out his legacy. Members of the congregation have become certified water- quality monitors, collecting water samples with portable kits supplied by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Bishop Heron Johnson has become a champion of conservation across Birmingham, Alabama. FRESHWATER LAND TRUST More Info Online Read about the Religious Lands Conservation Project in Massachusetts, which has helped more than 20 land conservation deals come to fruition. Go to www.lta.org/savingland/ spring2015.

- 27. www.landtrustalliance.org SAVINGland Spring 2015 27 Planting Zen in Oregon In Portland, Oregon, the Dharma Rain Zen Center (Dharma Rain) has been working with the Columbia Land Trust to transform a former brownfield site into a beautiful green space that will serve as the Buddhist center’s new campus. The space will feature a traditional Buddhist temple surrounded by wooded areas, winding paths, gardens and a cluster of residential spaces. The project is designed to foster spiritual practice and bring the broader community together. “We hope that redeveloping this brownfield will spur a transformation of the surrounding neighborhood,” says Kakumyo Lowe-Charde, a priest at Dharma Rain. The partnership between Dharma Rain and the land trust was a natural fit. At its old location, the center had been involved with the Backyard Habitat Program—an initiative of the Audubon Society of Portland and the Columbia Land Trust that encourages landowners to plant gardens and create green space. “We were already aware of the land trust’s vision and values, and we felt a sense of alignment there,” says Lowe-Charde. The new facility is located in a diverse and economically distressed part of the city—a generally under-natured area that is isolated by freeways and topography from other parts of Portland. By partnering with Dharma Rain, Columbia Land Trust has been able to forge ties with this community and introduce some of the many benefits of nature and open space. “The site is located in an area where we haven’t typically gotten a high-level of enrollment in our program,” says Gaylen Beatty, manager of the Backyard Habitat Program. “And it’s been an opportunity to develop meaningful relationships within that community.” Columbia Land Trust, in turn, has helped Dharma Rain with environmental work and site assessments, as well as provided support for educational programs and outreach events. “This is a very big project—beyond our usual scope,” Lowe-Charde says. “The land trust ‘got’ the vision for this landscape.” “This is an example of the power of a religious organization getting involved in the environmental movement. We’ve seen young people, non-churchgoers, learn about what’s happening with the fish and actually come down and join the church. They want to get involved,” says Dr. Howell. The partnership between the Faith Apostolic Church and the Freshwater Land Trust garnered the attention of two- time Pulitzer Prize-winning biodiversity expert Edward O. Wilson, an Alabama native. Dr. Wilson has applauded the efforts of Bishop Johnson and the church, saying that “this kind of effort should be duplicated around the country.” Bishop Johnson’s conservation work has expanded beyond the boundaries of Seven Springs. He has been the Freshwater Land Trust’s partner in establishing Red Mountain Park, the Village Creek Greenway and several other preservation projects the land trust has spearheaded—becoming a voice for conservation across Birmingham. These are things that might never have happened, says Wendy Jackson, “but for this small fish and this man of God.” Lessons Learned When land trusts and religious orders work together, both move to a higher place—achieving things that neither could accomplish working alone. Here are a few pointers to help land trusts engage with religious entities in the most effective manner. • Do your homework. Try to learn about the religious order: who they are, what they believe in, how the organization is structured, how decision-making and governance occur. • Listen. Listen and understand how religious groups view their land, what their financial needs are and how they envision the future. • Explain and educate. Take the time to explain what land conservation is, how it works and the extent to which it helps advance the group’s mission and objectives. • Learn to speak each other’s language. But do not simply rely on secular reasoning. Call upon religious values and the sacred reasoning of different faith traditions, says Marybeth Lorbiecki, director of the Interfaith Ocean Ethics Campaign. Tell stories linking ecosystems and neighborhoods—for example, how protecting open space enriches the lives of children in nearby neighborhoods. • Be respectful. Respect that you are working with people of faith who are deeply committed to their beliefs. • Take time and develop trust. Be consistent, reliable, clear and honest. Allow time for the process to unfold. Many religious groups are not accustomed to partnering with outside organizations. Building trust is very important. • Focus on areas of commonality. Most important, seek common ground between the land trust and the religious entity. Find areas of overlap in terms of vision, goals and objectives. Recognize that both groups exist to make the world a better place. EDITH PEPPER GOLTRA IS A FREELANCE WRITER IN MASSACHUSETTS. Columbia Land Trust held a work party last summer at the Dharma site. Kakumyo Lowe-Charde, at right, speaks to the volunteers about the project. COLUMBIALANDTRUST

- 28. 28 Spring 2015 SAVINGland www.landtrustalliance.org board MAT TERS BY Jack Savage How to Communicate in a Crisis F or any land trust, large or small, credibility is the ultimate coin of the realm. After all, “trust” is in our names and inherent in our mission. All nonprofits rely on supporters believing that the staff and board of the organization are trustworthy. Land trusts depend on absolute confidence that we will act in accordance with our mission and will do so “in perpetuity.” JEFFLOUGEE Before conducting a controlled burn and any preparatory timber clearing on protected property, let your community know when these things will occur and how they will benefit the land.