This document provides a summary of analysis from the author's Macro Strategy Review publications from 2014 to 2015. It discusses the author's approach of combining fundamental and technical analysis. As an example, in 2014 the author correctly predicted a rally in the US dollar based on signals from the euro currency and implications for emerging markets. The summary highlights several insights the author provided regarding the dollar, euro, commodities, and emerging markets. It positions the Macro Strategy Review as a valuable resource that helps navigate challenging markets by incorporating both fundamental and technical analysis.

![Macro Strategy Review www.forwardinvesting.com18

dollar strength. According to the International Monetary Fund,

$650 billion has flowed into emerging markets as a result of

quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve. There is a significant

risk that some of this money will flow out of emerging economies

as their currencies depreciate. A rush for the exit has the potential

of igniting a currency crisis as affected central banks are forced to

defend their currency through direct intervention or interest

rate increases.

According to the Bank for International Settlements, more than

two-thirds of the $11 trillion in cross-border bank loans are

denominated in dollars and an unknown amount is not hedged.

This has the potential to be a big problem since nonhedged dollar

debt becomes more expensive as the dollar rises. For instance, if the

dollar rises by 12%, which it has since May, a $100 million loan that

is nonhedged may now be effectively $112 million if the currency

of the loan holder has fallen 12%. This is another aspect of why

the depreciation of the yen and euro amounts to those countries

exporting the very deflation they are attempting to ward off in

their own economies. The volatility in the currency market that the

BOJ and ECB have initiated is likely to intensify in coming months.

If it does, it is easy to see how it could spill over into global equity

markets, which have greeted every central bank intervention by

lifting stock valuations.

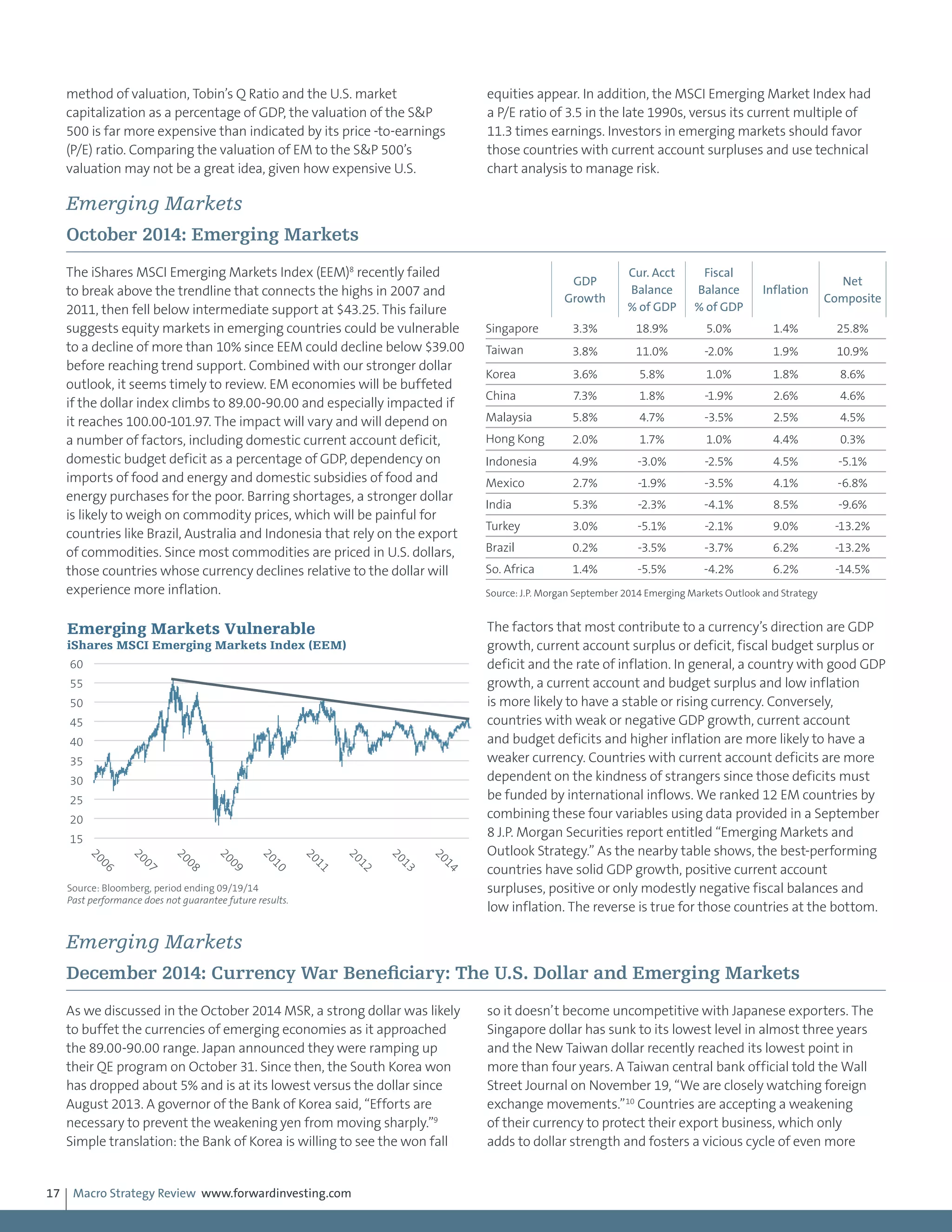

Emerging Markets

February 2015: U.S. Dollar and Foreign Currency

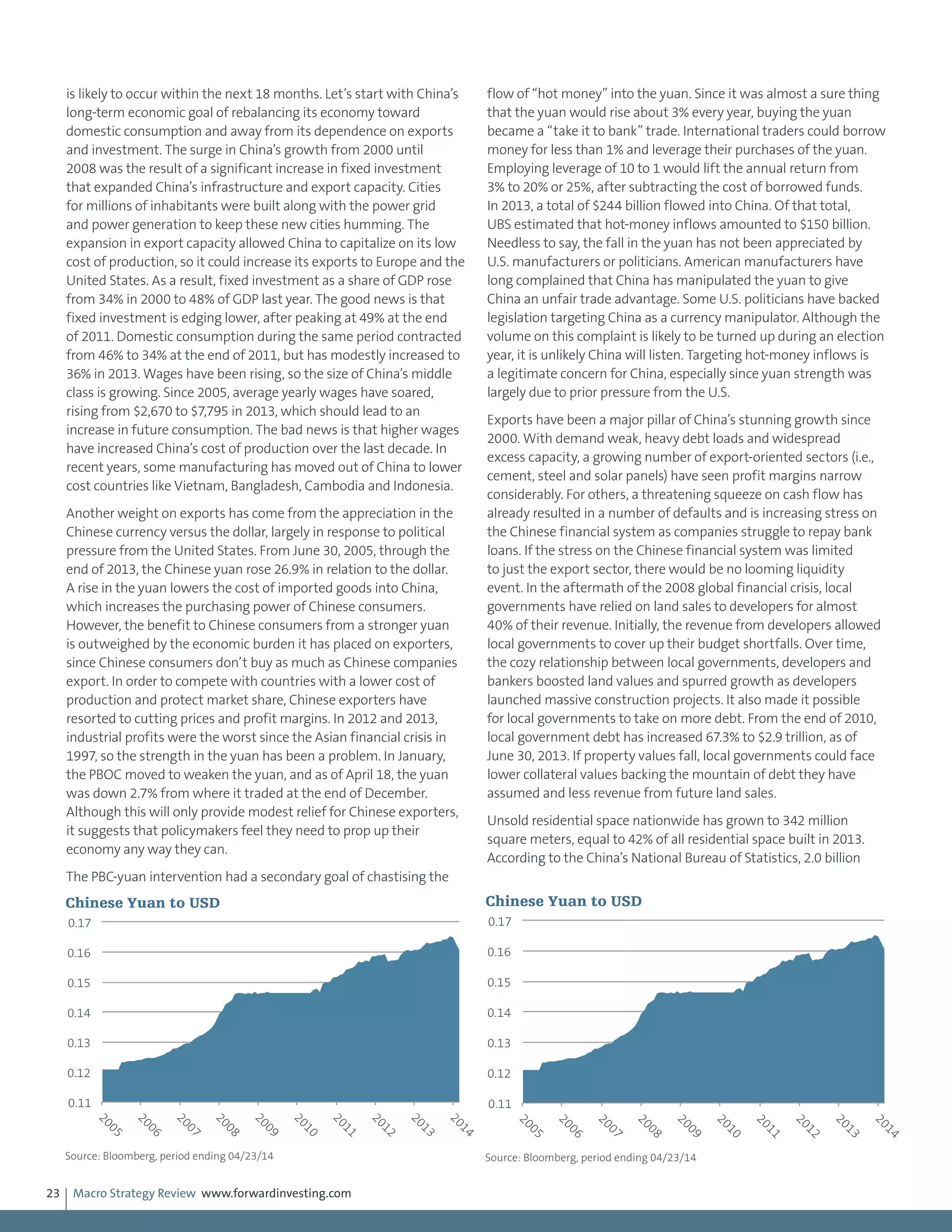

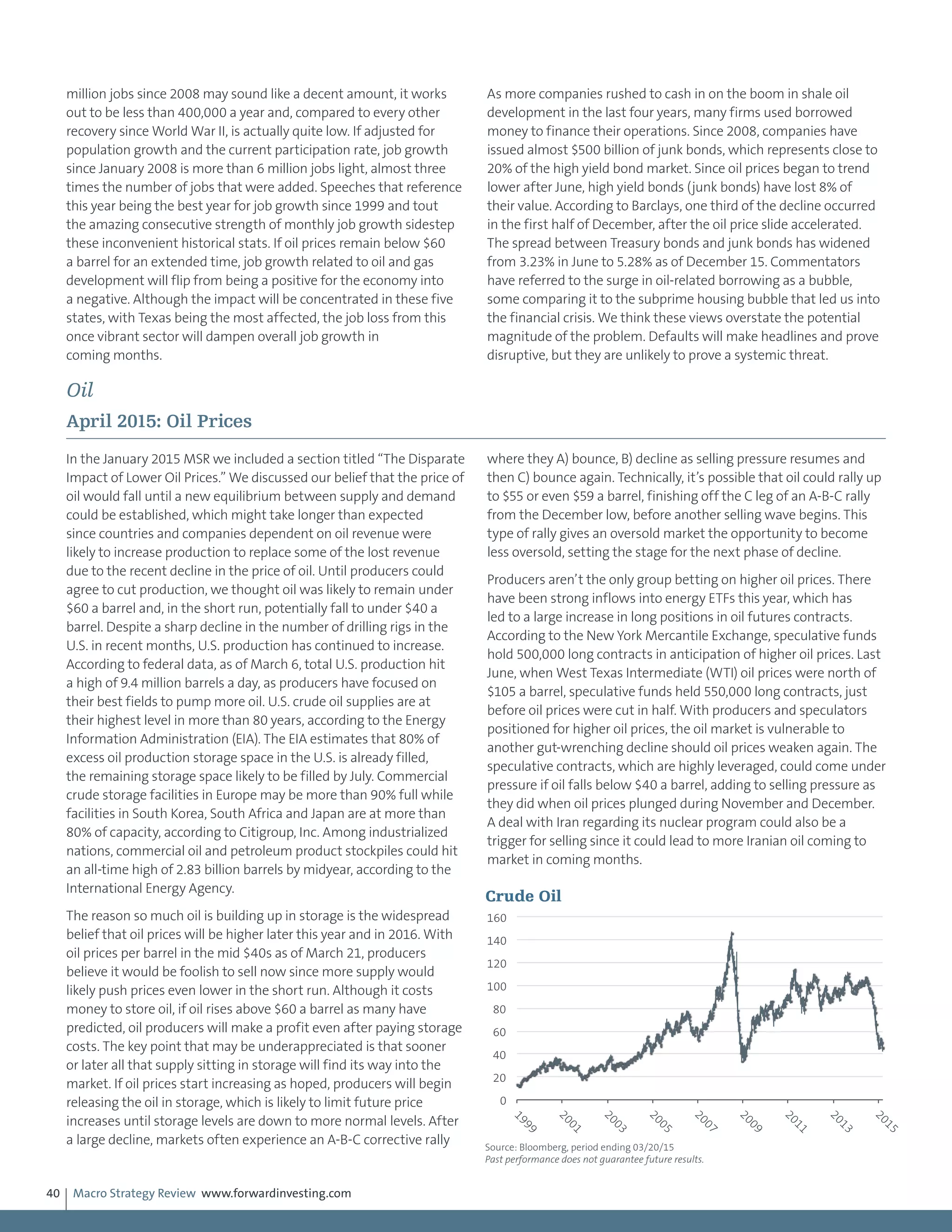

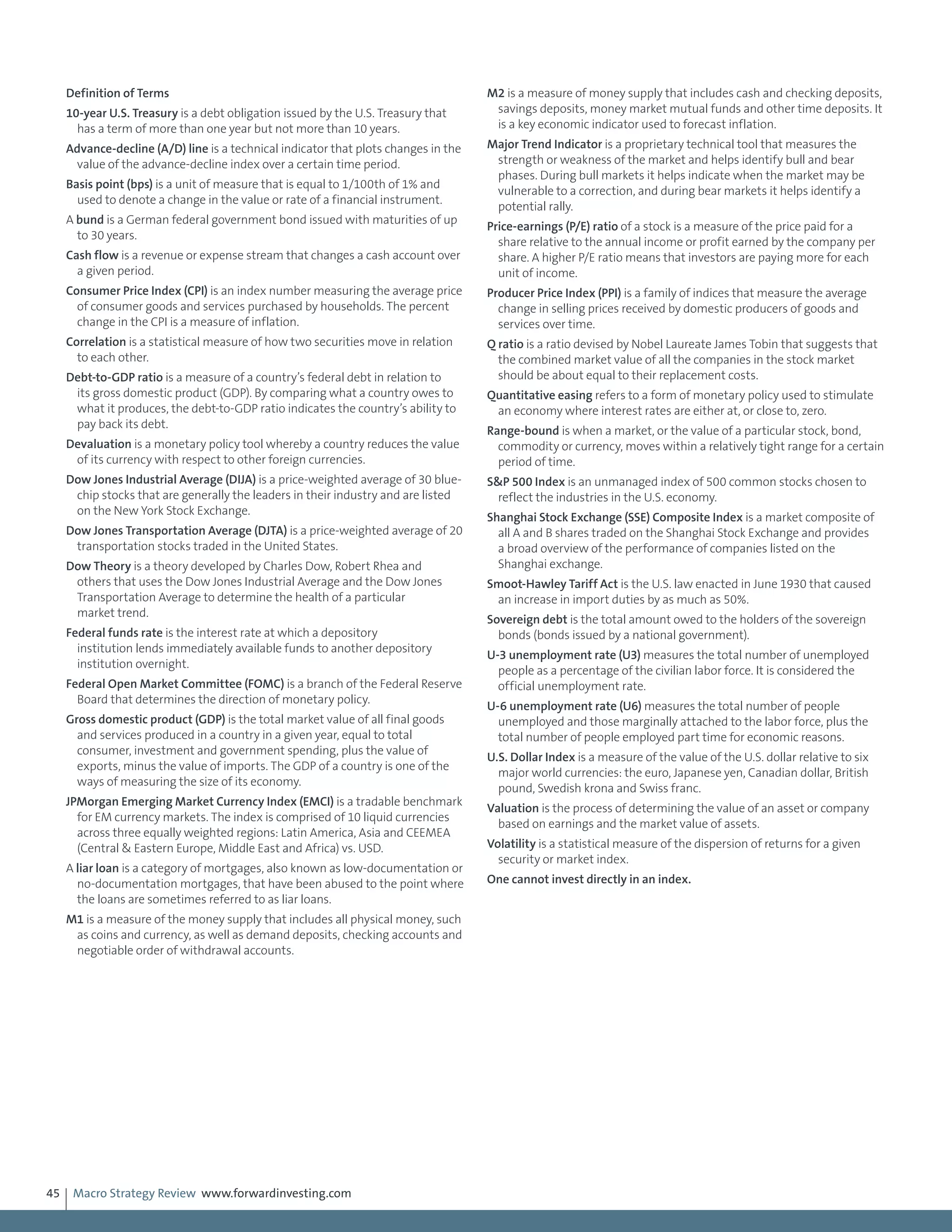

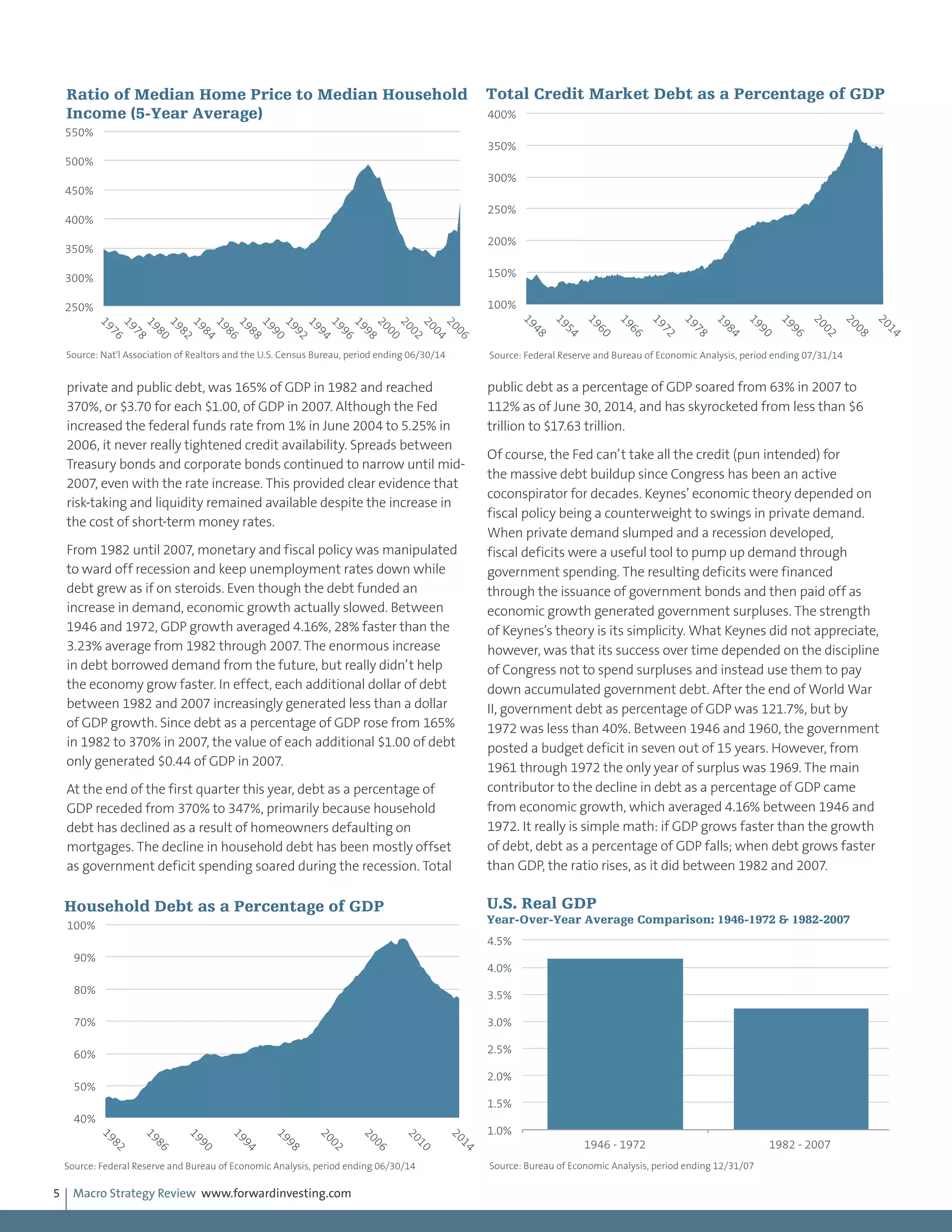

In the April 2014 MSR we wrote, “The collateral damage that might

flow from a weaker euro and stronger dollar could include renewed

weakness in emerging market [EM] currencies with current account

deficits and another decline in gold and a range of commodities,

since a stronger dollar is likely to increase deflationary pressures in

the global economy. There is a lot of debt denominated in dollars

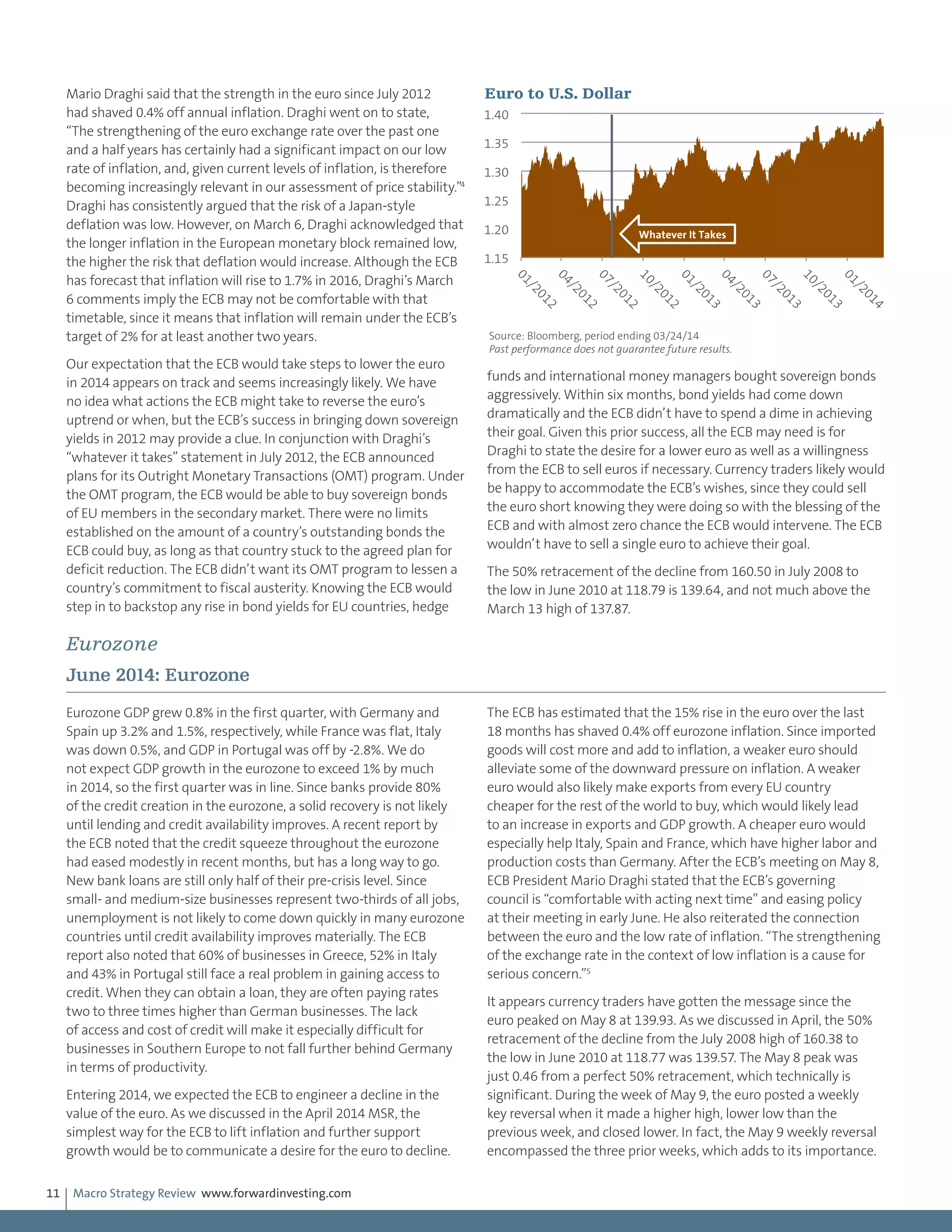

and most commodities are priced in dollars.” The euro experienced

a three week key reversal the week of May 9, 2014, which we

discussed in the June 2014 MSR. The technical key reversal in the

euro coincided with the beginning of the rally in the dollar. Based on

the J.P. Morgan basket of emerging market currencies (EMCI), dollar

strength has translated into a decline of 13.3% as this is written on

January 26. Since May 2014, the S&P Goldman Sachs Commodity

Index (GSCI) has declined by 41.5%. Certainly, a large portion of the

loss was due to the drop in oil, but many other commodities have

fallen, just less dramatically. Copper has declined -17.3% after falling

from $3.05 a pound last May to $2.52. As noted in previous MSRs,

we expected gold to break below its support at $1,180 as the dollar

strengthened. Gold bottomed on November 7, 2014, at $1,132

-10%

-8%

-6%

-4%

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

11/02/1201/02/1303/02/1305/02/1307/02/1309/02/1311/02/1301/02/1403/02/1405/02/1407/02/1409/02/1411/02/14

South Korea Taiwan Singapore China

U.S. Dollar vs. South Korea Won, Taiwan Dollar,

Singapore Dollar and China Yuan

Source: Bloomberg, period ending 11/21/14

Past

performance

does

not

guarantee

future

results.

75

80

85

90

95

100

105

110

01/2011

07/2011

01/2012

07/2012

01/2013

07/2013

01/2014

07/2014

01/2015

J.P. Morgan EM Currency Index

Source: J.P. Morgan, period ending 01/22/15

Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Taper Talk

Dollar Rally

350

400

450

500

550

600

650

700

750

01/2012

07/2012

01/2013

07/2013

01/2014

07/2014

01/2015

S&P GSCI

Source: Standard & Poor's, period ending 01/23/15

Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Dollar Rally](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3ca54fc7-5ea5-4e4e-85bb-b7d4f20a37b2-150930200801-lva1-app6891/75/Macro-Strategy-Review-Summary-Jan-2014-Aug-2015-18-2048.jpg)

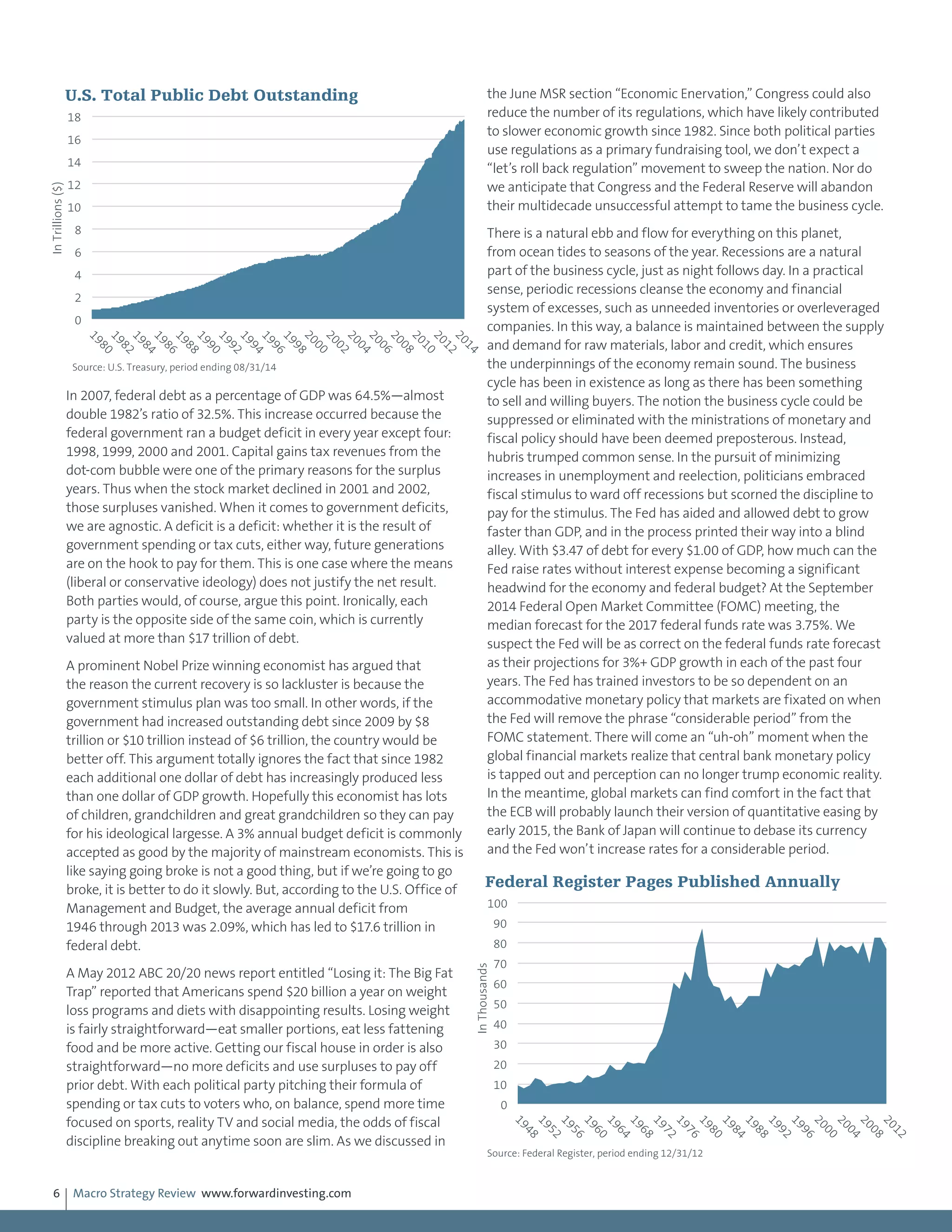

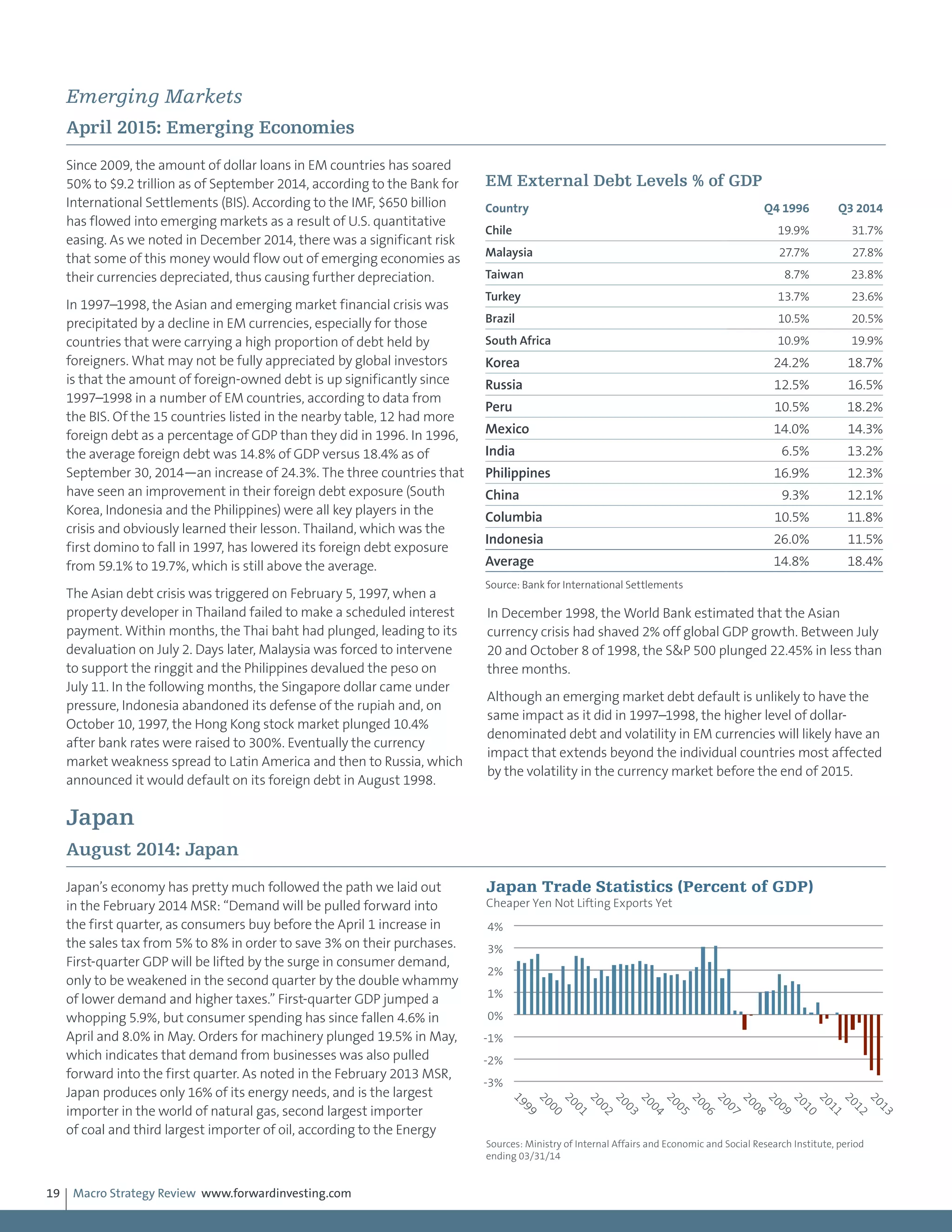

![Macro Strategy Review www.forwardinvesting.com20

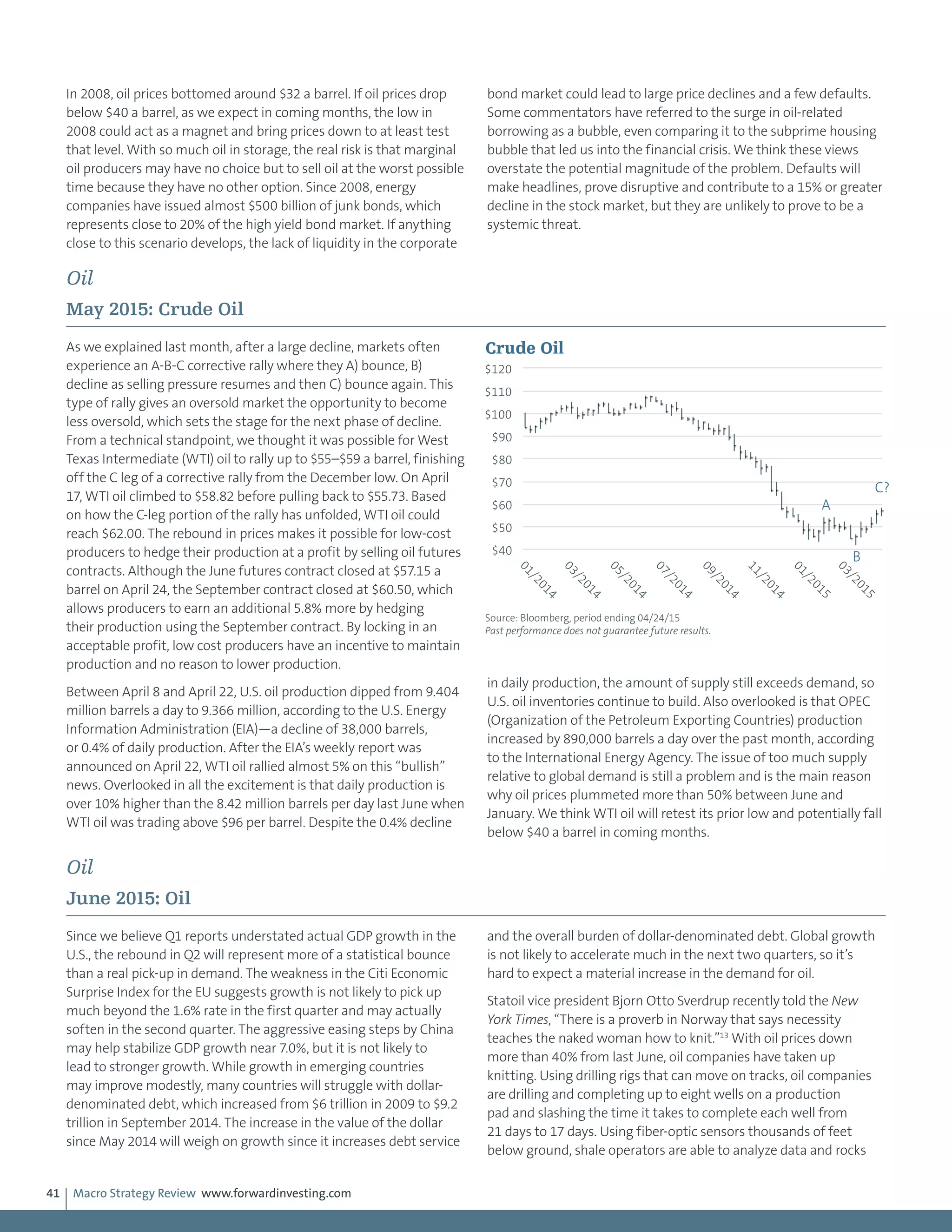

Information Administration. Since these commodities are priced in

dollars, we expected the decline in the yen to increase the cost of

these imports, resulting in more inflation and a larger trade deficit.

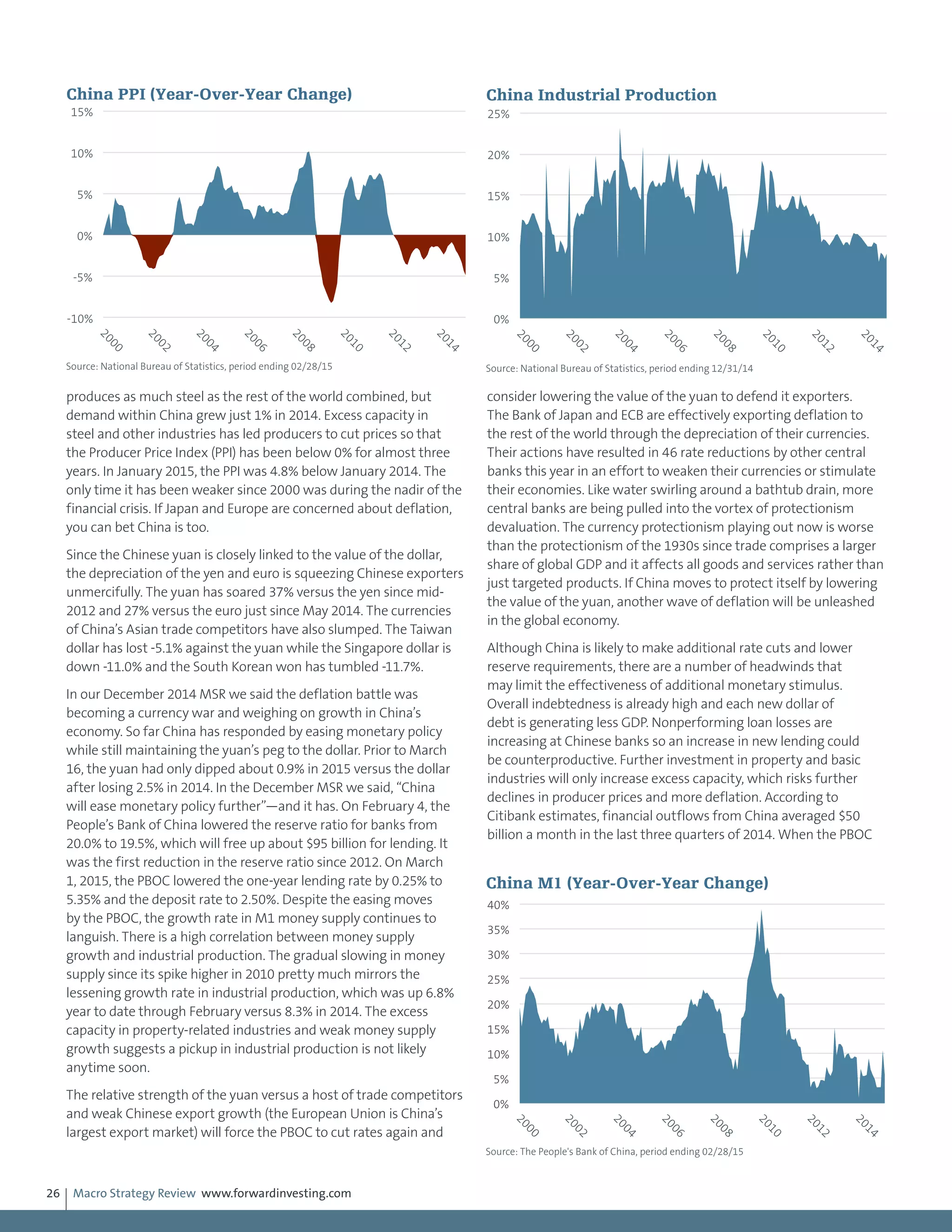

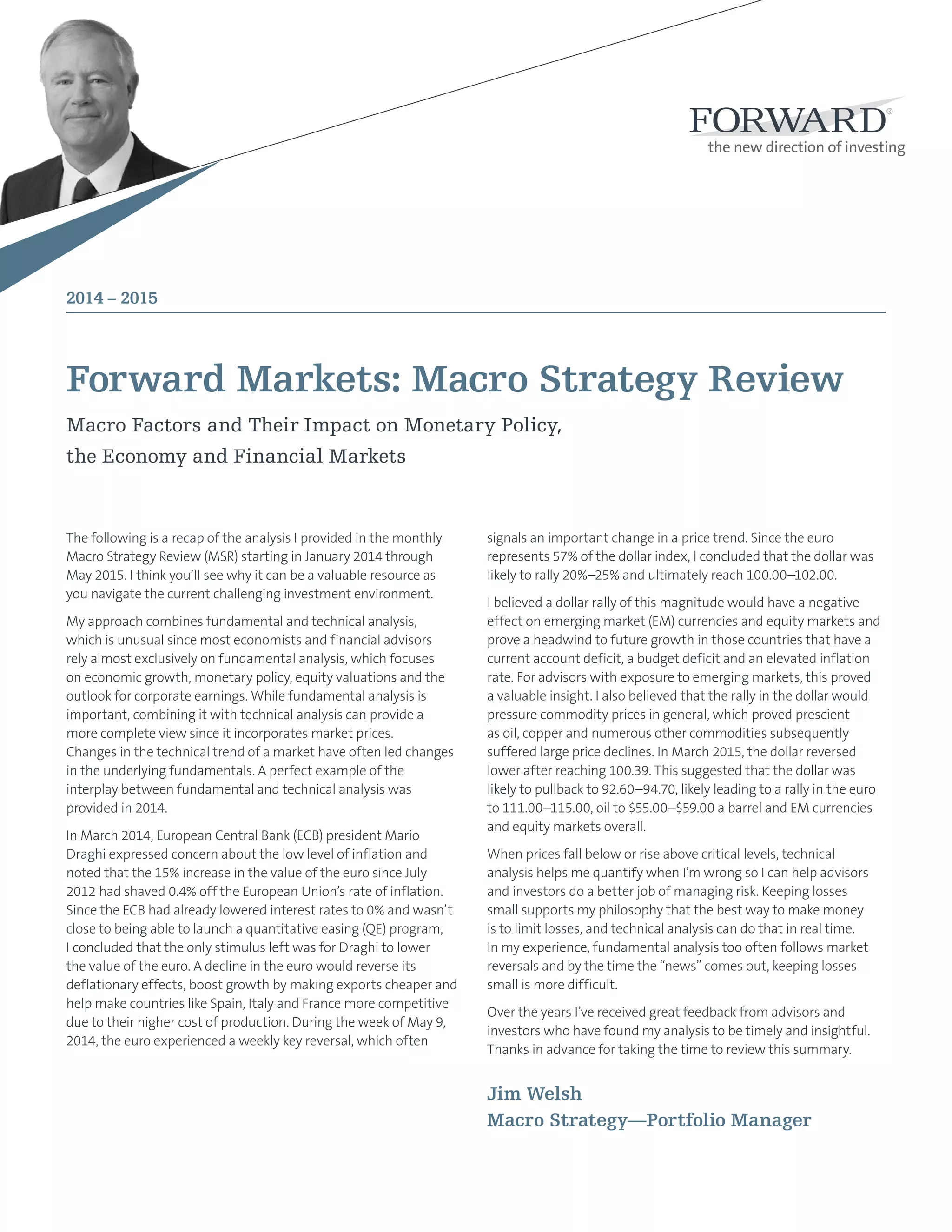

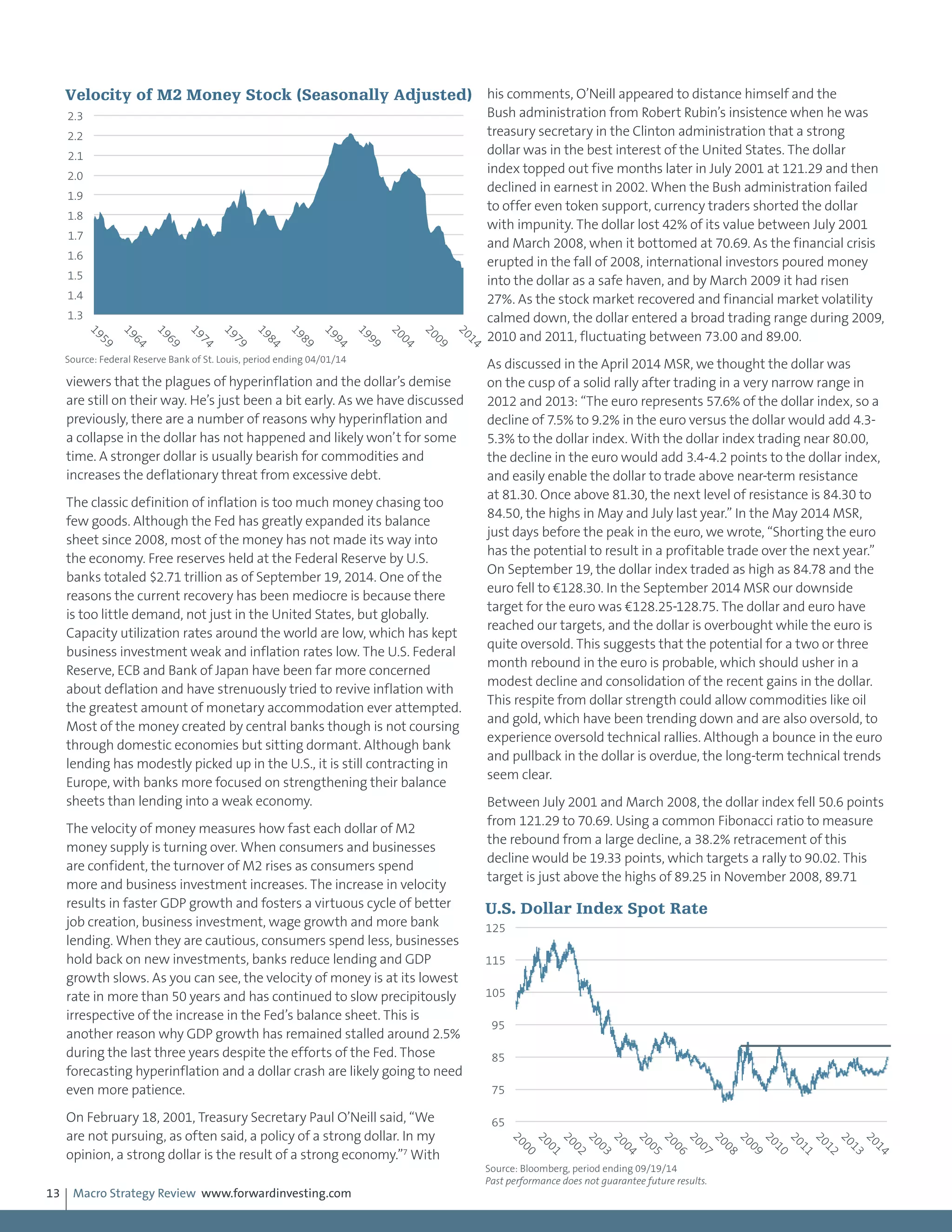

In May, Japan’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) was 3.7% higher than in

May 2013. As of March 31, 2014 (latest data available), Japan’s trade

deficit as a percentage of GDP was the largest in decades. Prime

Minister Shinzo- Abe has succeeded in reversing deflation, but he

may have succeeded too well since the cost of living is rising faster

than the increase in wages. This may hurt future consumption,

resulting in slower GDP growth in coming quarters. If Japan’s

economy does not shows signs of recovering from the tax increase

before year-end, the Bank of Japan may instigate another round of

QE to cheapen the yen further and boost Japan’s stock market.

Japan

December 2014: Japan

Japan’s newest round of quantitative easing, tax cuts and currency

devaluation was triggered by a -1.6% decline in third quarter GDP

after its economy contracted -7.3% in the second quarter. The

weakness in the second quarter was prompted by an increase

in Japan’s sales tax from 5% to 8% on April 1. As we noted in the

November 2013 MSR, “As consumers rush to buy before April

in order to save 3% on their purchases…first quarter [2014] GDP

will be lifted by the surge in consumer demand, only to weaken

significantly in the second quarter. This will be the first real test of

the durability of Abenomics.” While the first quarter strength of

6.7% and second quarter weakness was predictable, the contraction

in the third quarter illustrates how fragile the Japanese economy

remains. In the August 2014 MSR we wrote, “If Japan’s economy

does not show signs of recovering from the tax increase before

year-end, the Bank of Japan may instigate another round of QE to

cheapen the yen further and boost Japan’s stock market.”

With the contraction in the second and third quarters, Japan has

entered its fourth recession since 2007. The BOJ vote to increase

its QE program was a close 5 to 4, however, since some members

are concerned about the precariousness of Japan’s long-term fiscal

health. As Japan’s total debt-to-GDP ratio is a mind-blowing 640%,

their concern is more than justified.

Real household income, which adjusts for inflation, has declined for

15 consecutive months and has dropped from an increase of almost

3% in the first half of 2013 to -6.0% as of September 30, 2014.

Although wages rose for the seventh straight month in September

and were up 0.5% from September 2013, the improvement in

wages still lagged the 3.2% increase in Japan’s consumer price index

(CPI) in September. The purchasing power of the average Japanese

worker continues to worsen. In fact, a BOJ survey released in

October found that only 4.4% of households said they were better

off than a year ago. As consumers account for about 65% of Japan’s

GDP, their finances and outlook are important.

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

Japan CPI (Year-Over-Year Change)

Rising Faster Than Incomes

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs, period ending 05/31/14

Past performance does not guarantee future results.

-10%

-8%

-6%

-4%

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

03/31/07

09/30/07

03/31/08

09/30/08

03/31/09

09/30/09

03/31/10

09/30/10

03/31/11

09/30/11

03/31/12

09/30/12

03/31/13

09/30/13

03/31/14

09/30/14

Japan GDP Growth (Year-Over-Year)

Source: Economic and Social Research Institute, period ending 09/30/14

500%

520%

540%

560%

580%

600%

620%

640%

660%

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

Japan Debt Oustanding as a Percentage of GDP

Source: Morgan Stanley Research, period ending 06/30/14

-8.0%

-6.0%

-4.0%

-2.0%

0.0%

2.0%

4.0%

6.0%

8.0%

10.0%

01/01/07

07/01/07

01/01/08

07/01/08

01/01/09

07/01/09

01/01/10

07/01/10

01/01/11

07/01/11

01/01/12

07/01/12

01/01/13

07/01/13

01/01/14

07/01/14

Japan Household Income (Year-Over-Year)

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs, period ending 09/30/14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3ca54fc7-5ea5-4e4e-85bb-b7d4f20a37b2-150930200801-lva1-app6891/75/Macro-Strategy-Review-Summary-Jan-2014-Aug-2015-20-2048.jpg)