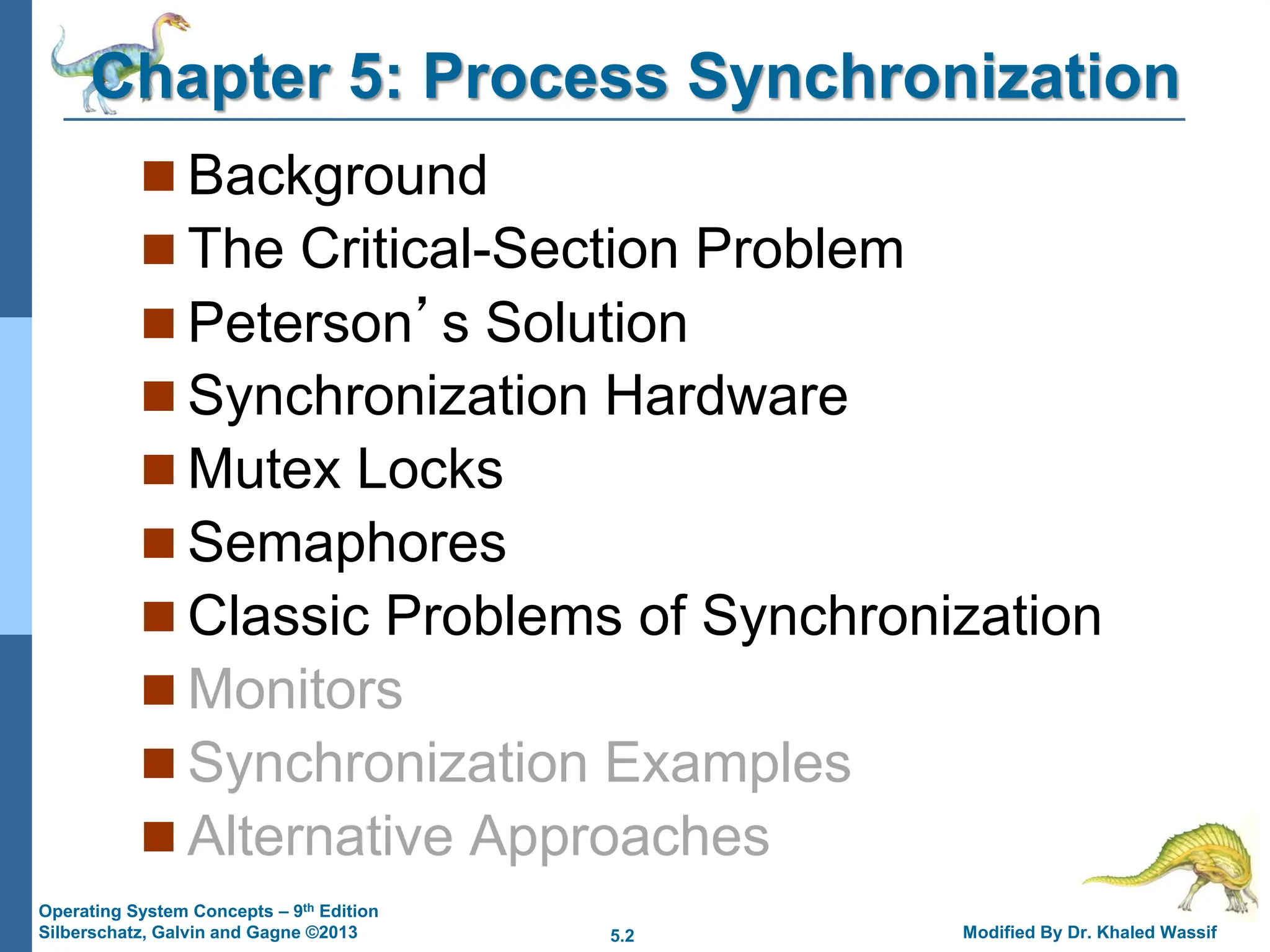

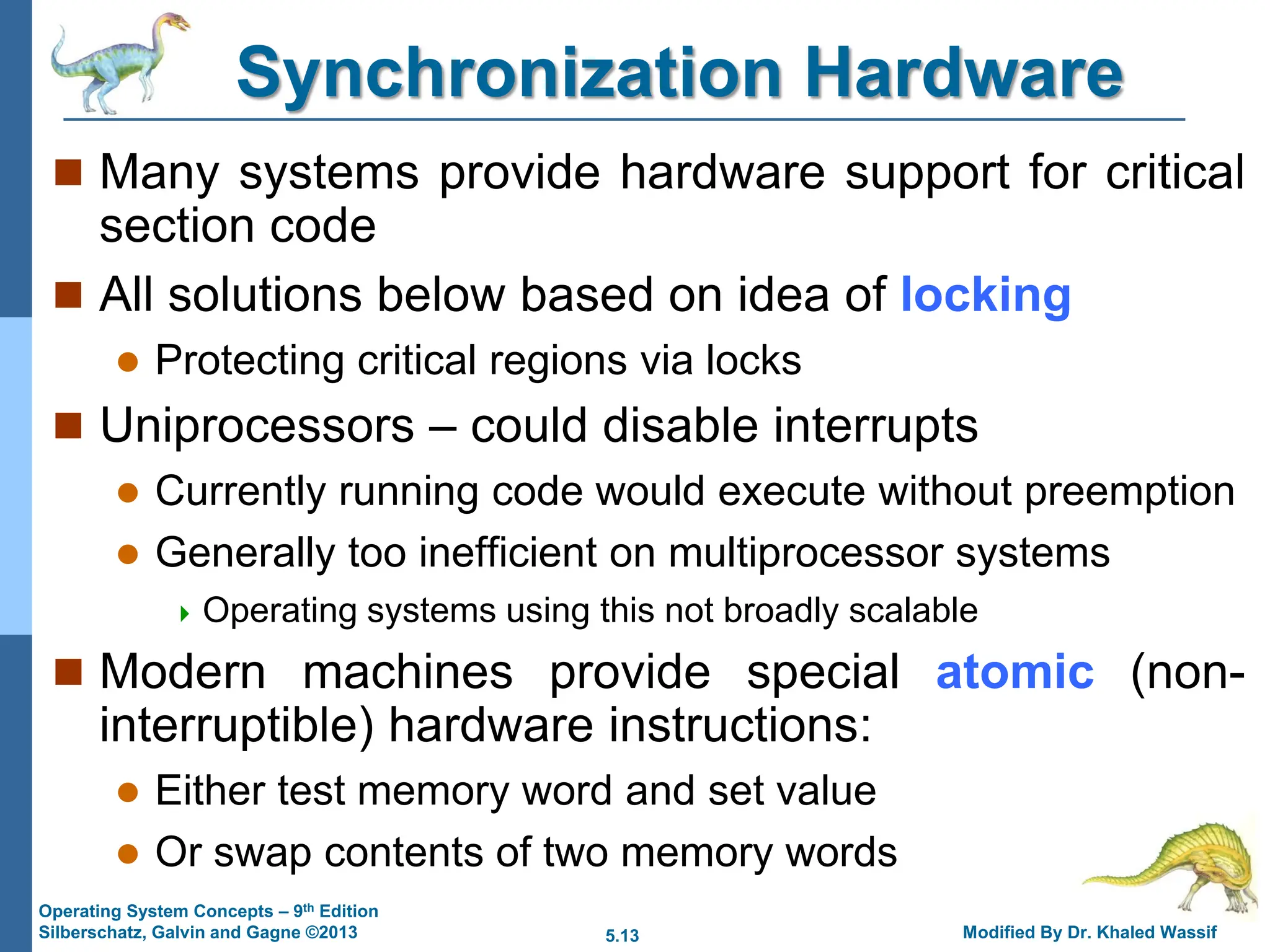

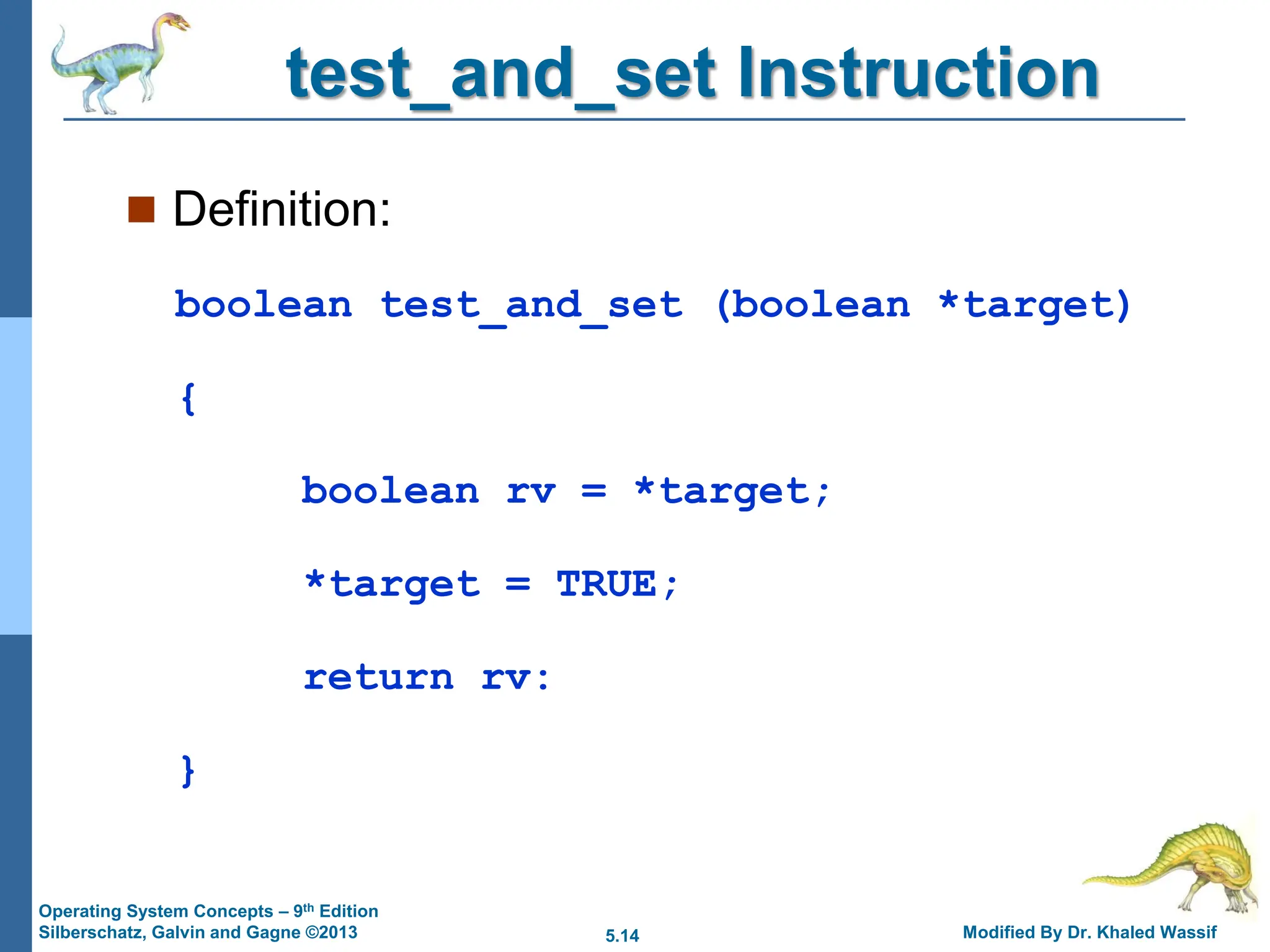

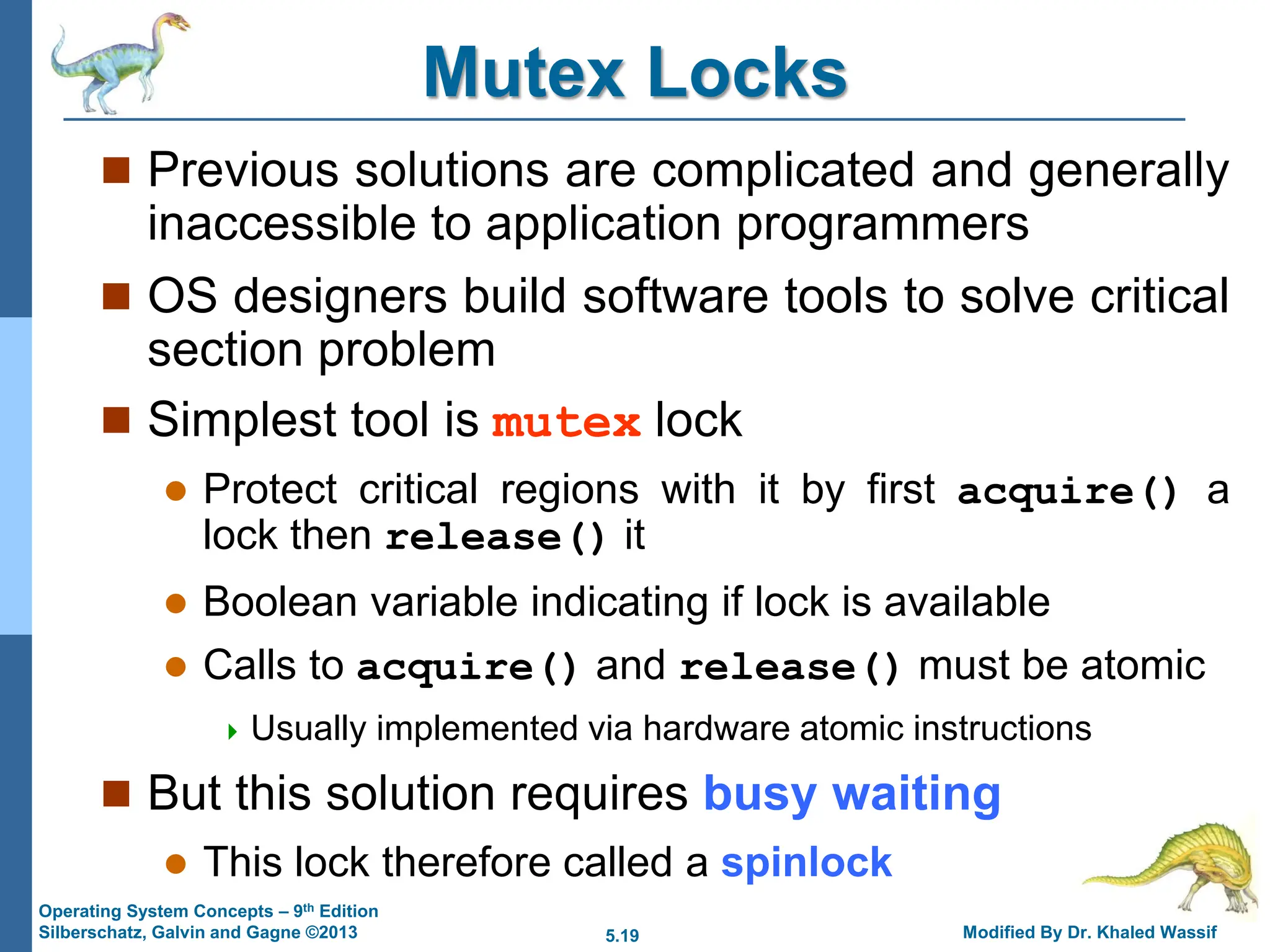

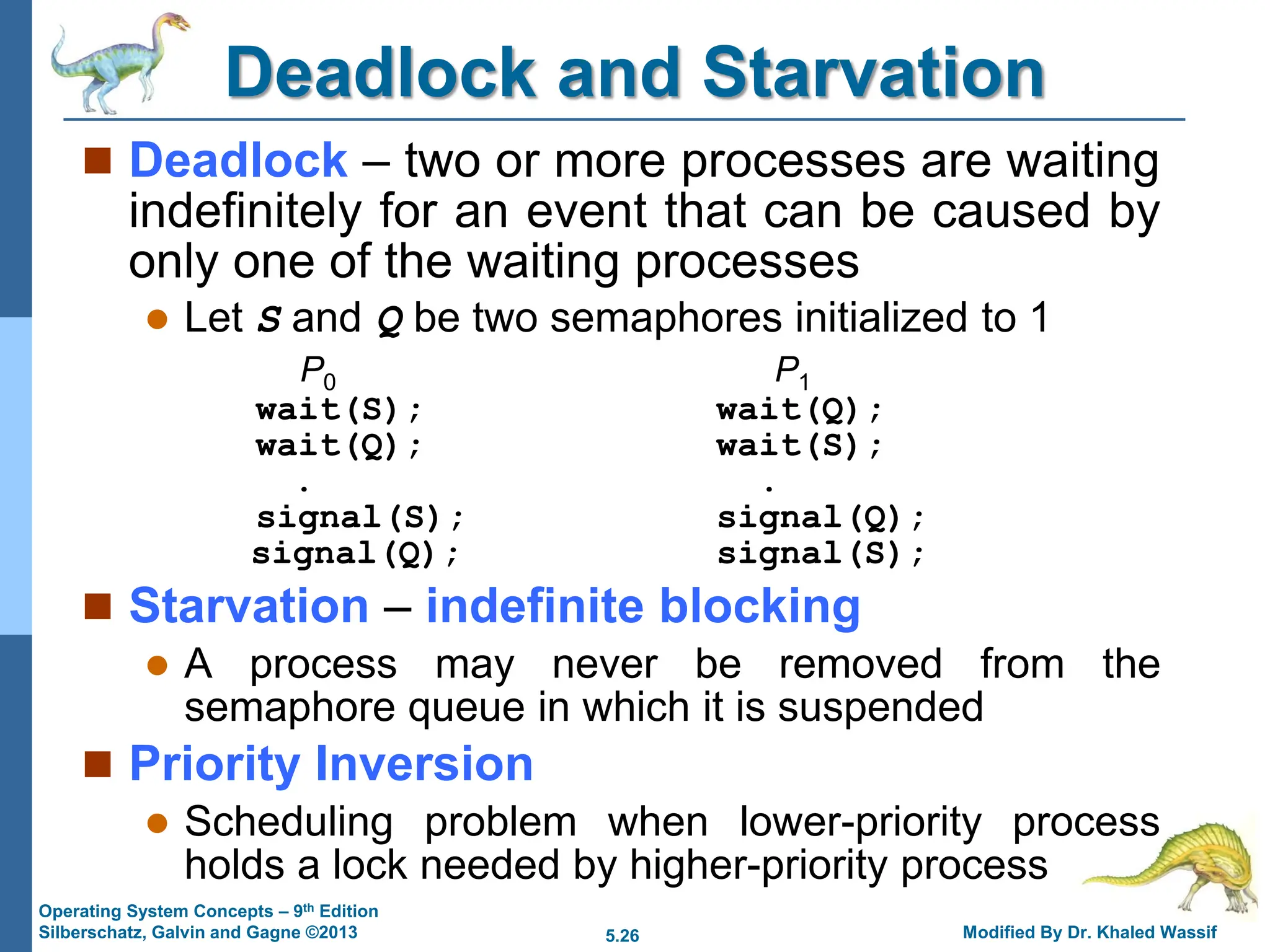

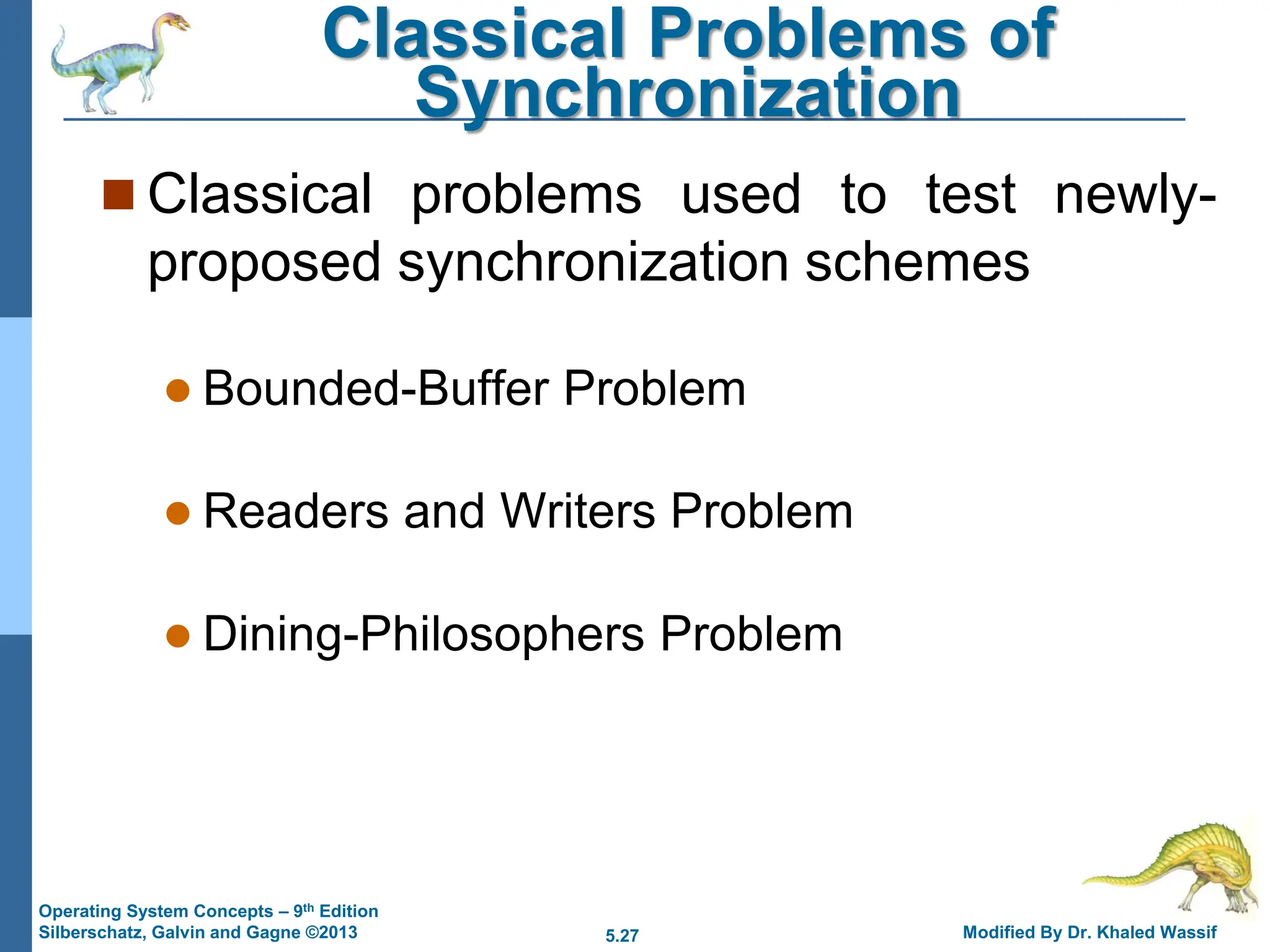

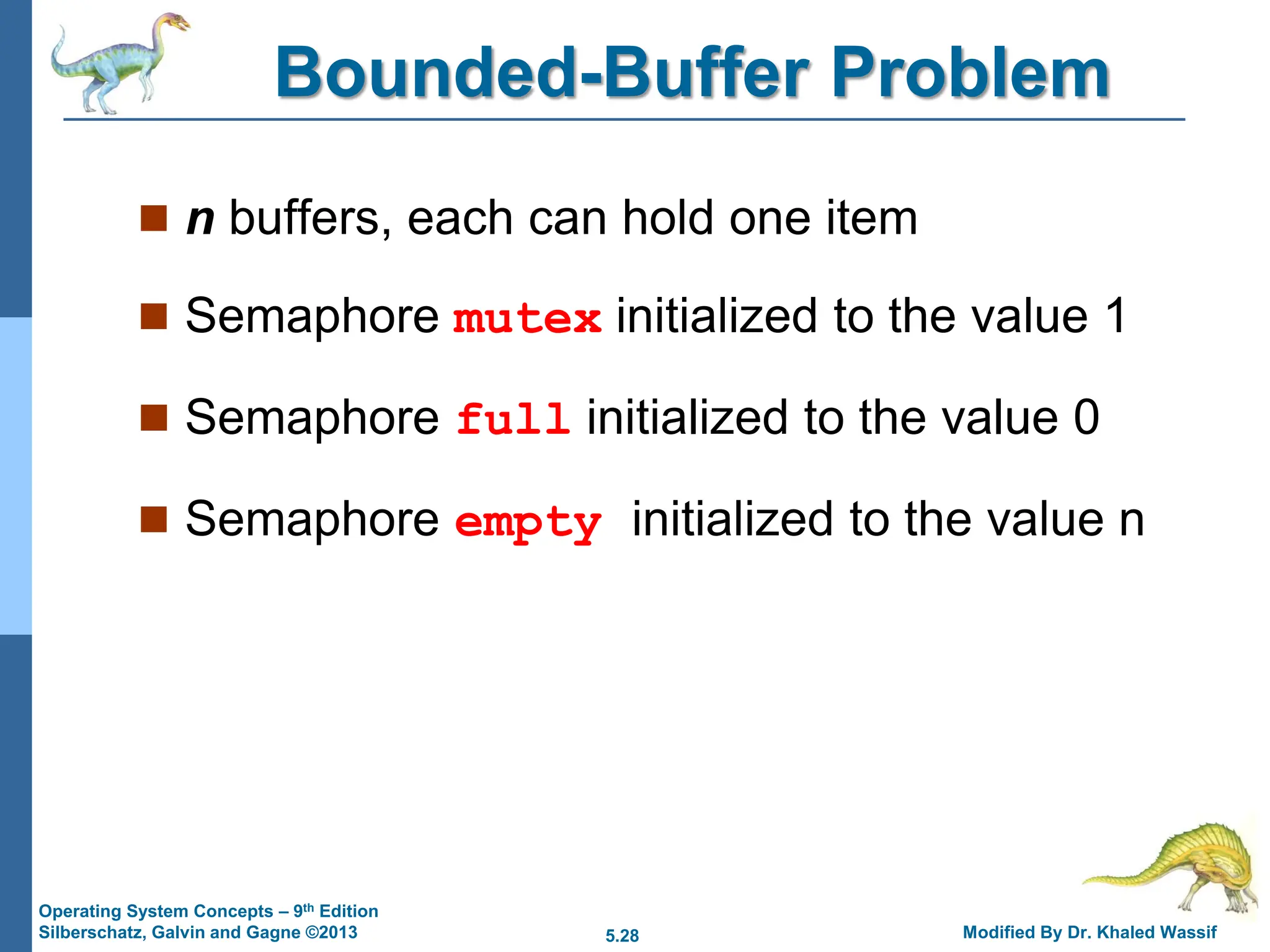

Chapter 5 of Operating System Concepts discusses process synchronization, focusing on the critical-section problem, its solutions, and various synchronization tools like mutex locks and semaphores. It introduces concepts like mutual exclusion, progress, and bounded waiting, and addresses classical synchronization challenges such as the producer-consumer, readers-writers, and dining philosophers problems. The chapter also presents algorithmic solutions including Peterson’s solution and hardware instructions for synchronization.

![5.5 Modified By Dr. Khaled Wassif

Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition

Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013

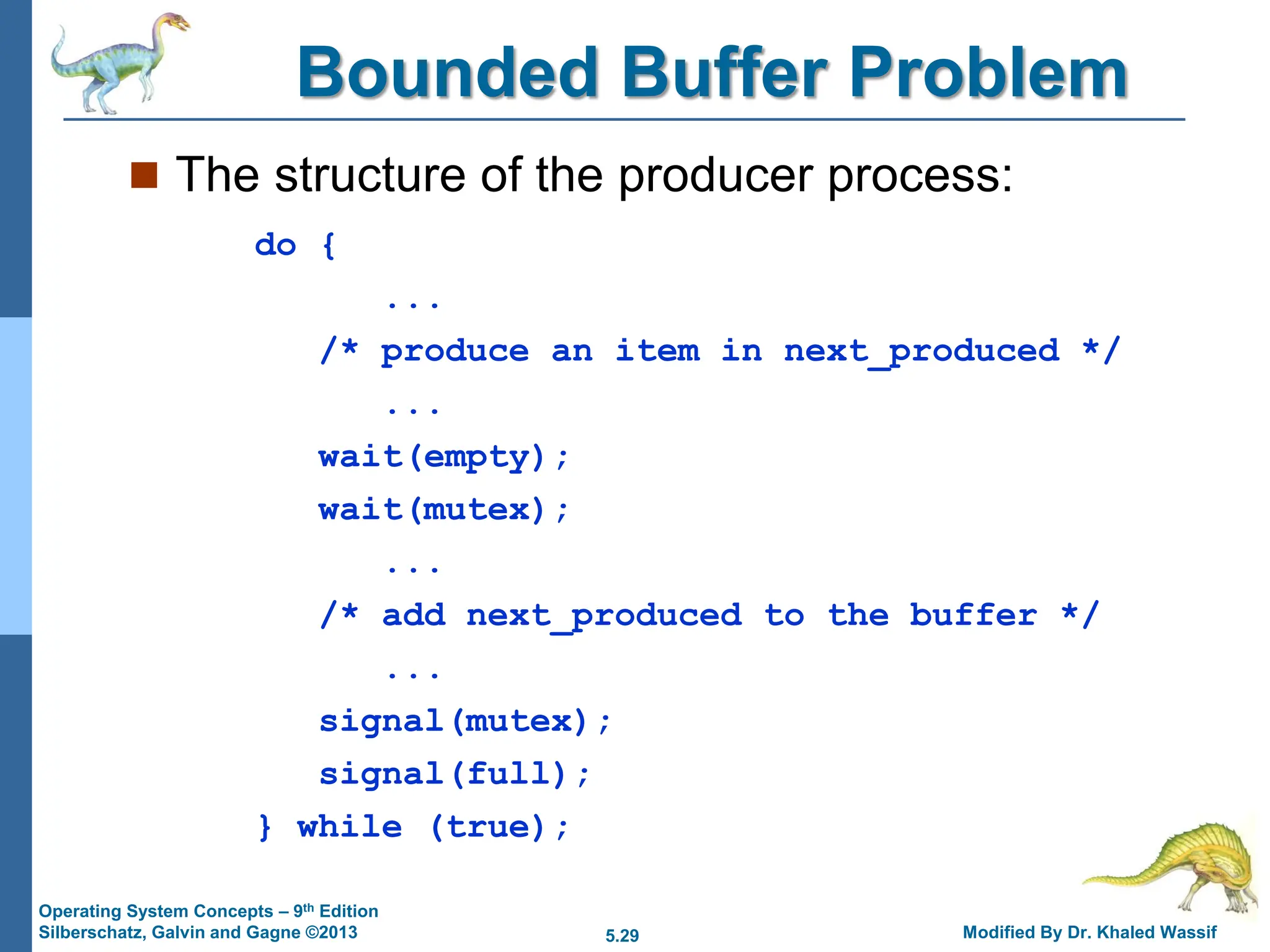

Producer

while (true) {

/* produce an item in next produced */

while (counter == BUFFER_SIZE)

; /* do nothing */

buffer[in] = next_produced;

in = (in + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

counter++;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w-ch05-250207000653-7854f029/75/W-ch05-pdf-semaphore-operating-systemsss-5-2048.jpg)

![5.6 Modified By Dr. Khaled Wassif

Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition

Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013

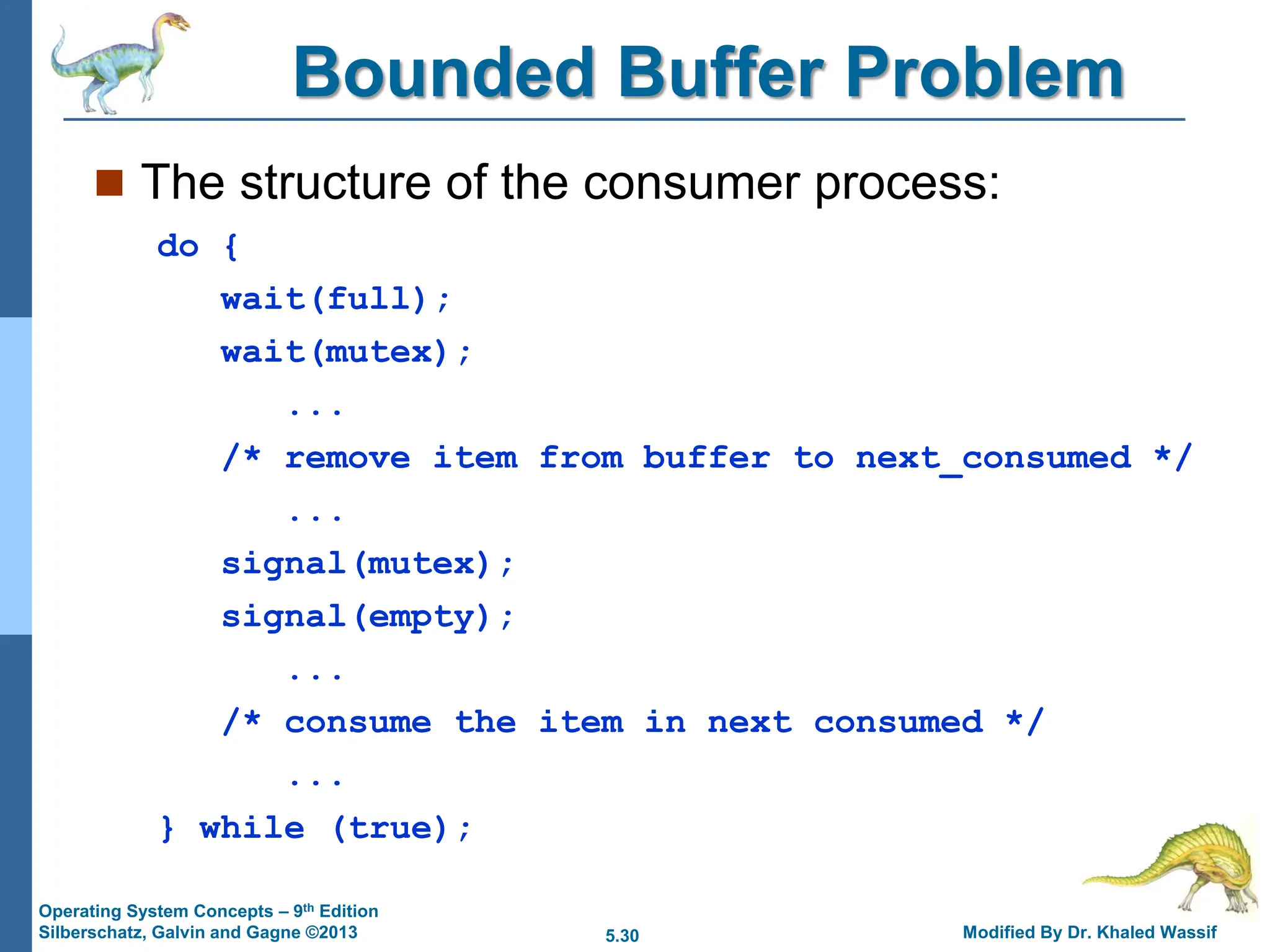

Consumer

while (true) {

while (counter == 0)

; /* do nothing */

next_consumed = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

counter--;

/* consume the item in next consumed */

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w-ch05-250207000653-7854f029/75/W-ch05-pdf-semaphore-operating-systemsss-6-2048.jpg)

![5.11 Modified By Dr. Khaled Wassif

Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition

Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013

Peterson’s Solution

Good algorithmic description of solving the problem

Two process solution (numbered Pi and Pj )

Assume that the load and store instructions are

atomic; that is, cannot be interrupted

The two processes share two variables:

int turn;

Boolean flag[2]

The variable turn indicates whose turn it is to enter the

critical section

The flag array is used to indicate if a process is ready

to enter the critical section.

flag[i] = true implies that process Pi is ready!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w-ch05-250207000653-7854f029/75/W-ch05-pdf-semaphore-operating-systemsss-11-2048.jpg)

![5.12 Modified By Dr. Khaled Wassif

Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition

Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013

do {

flag[i] = true;

turn = j;

while (flag[j] && turn == j);

critical section

flag[i] = false;

remainder section

} while (true);

Algorithm for Process Pi

Provable that

1. Mutual exclusion is preserved

2. Progress requirement is satisfied

3. Bounded-waiting requirement is met

Entry

section

Exit

section](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w-ch05-250207000653-7854f029/75/W-ch05-pdf-semaphore-operating-systemsss-12-2048.jpg)

![5.18 Modified By Dr. Khaled Wassif

Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition

Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013

Entry

section

Exit

section

Bounded-waiting with test_and_set

do {

waiting[i] = true;

key = true;

while (waiting[i] && key)

key = test_and_set(&lock);

waiting[i] = false;

/* critical section */

j = (i + 1) % n;

while ((j != i) && !waiting[j])

j = (j + 1) % n;

if (j == i)

lock = false;

else

waiting[j] = false;

/* remainder section */

} while (true);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w-ch05-250207000653-7854f029/75/W-ch05-pdf-semaphore-operating-systemsss-18-2048.jpg)

![5.36 Modified By Dr. Khaled Wassif

Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition

Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013

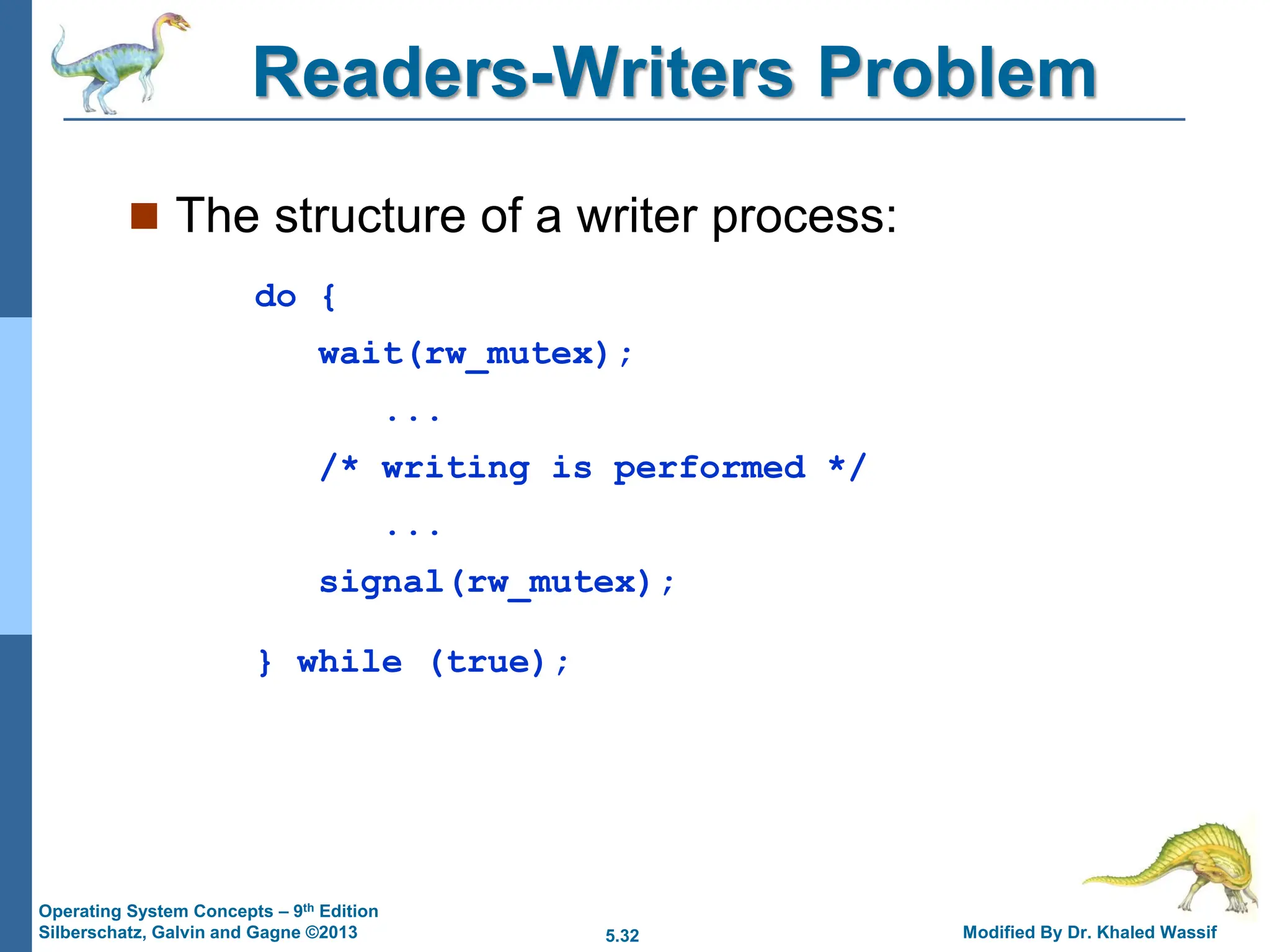

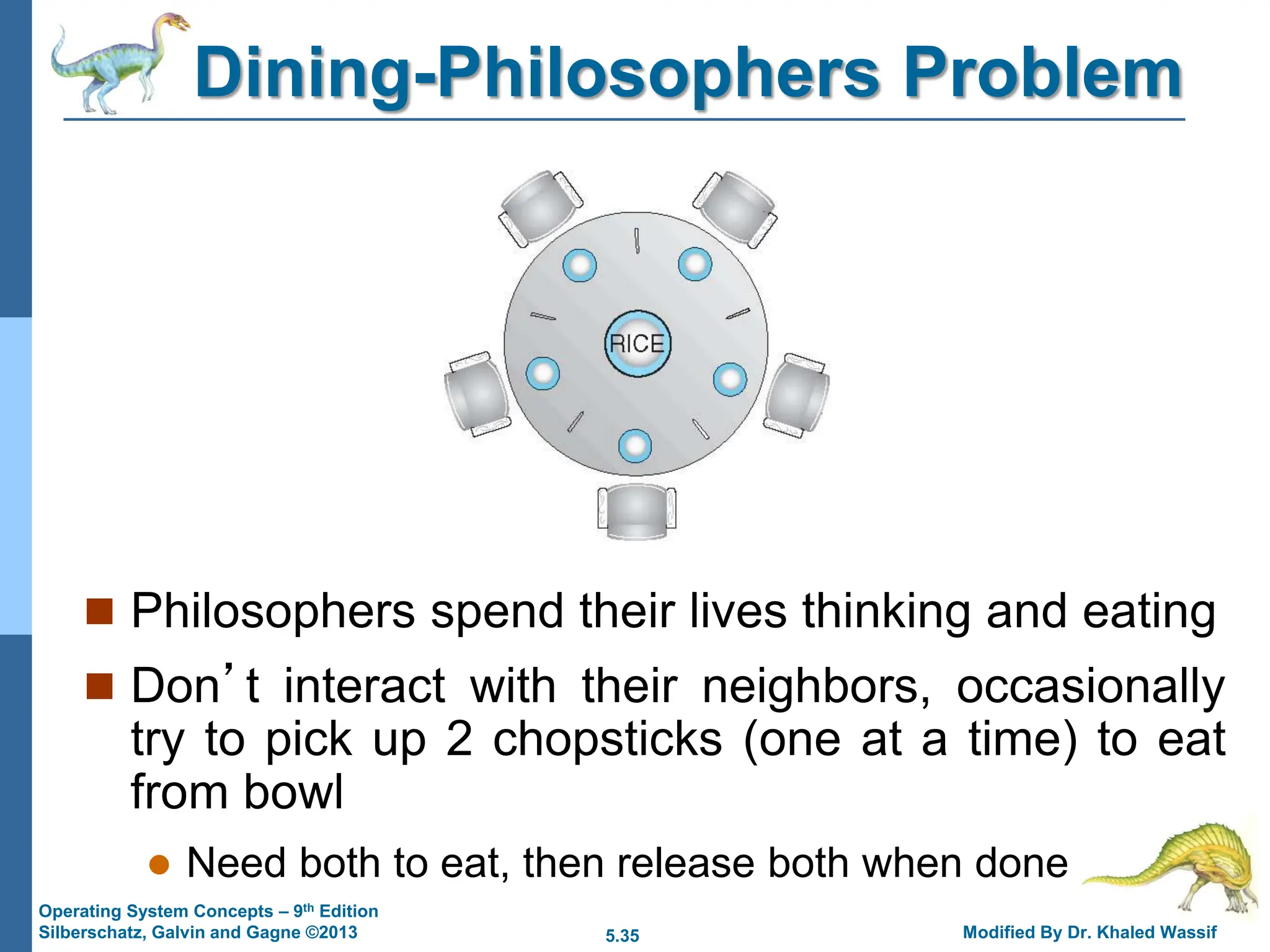

Dining-Philosophers Problem

Shared data (in the case of 5 philosophers)

Bowl of rice (data set)

Semaphore chopstick [5] initialized to 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w-ch05-250207000653-7854f029/75/W-ch05-pdf-semaphore-operating-systemsss-36-2048.jpg)

![5.37 Modified By Dr. Khaled Wassif

Operating System Concepts – 9th Edition

Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2013

Dining-Philosophers Problem

The structure of Philosopher i:

do {

wait (chopstick[i] );

wait (chopStick[ (i + 1) % 5]);

// eat

signal (chopstick[i] );

signal (chopstick[ (i + 1) % 5]);

// think

} while (TRUE);

What is the problem with this algorithm?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/w-ch05-250207000653-7854f029/75/W-ch05-pdf-semaphore-operating-systemsss-37-2048.jpg)