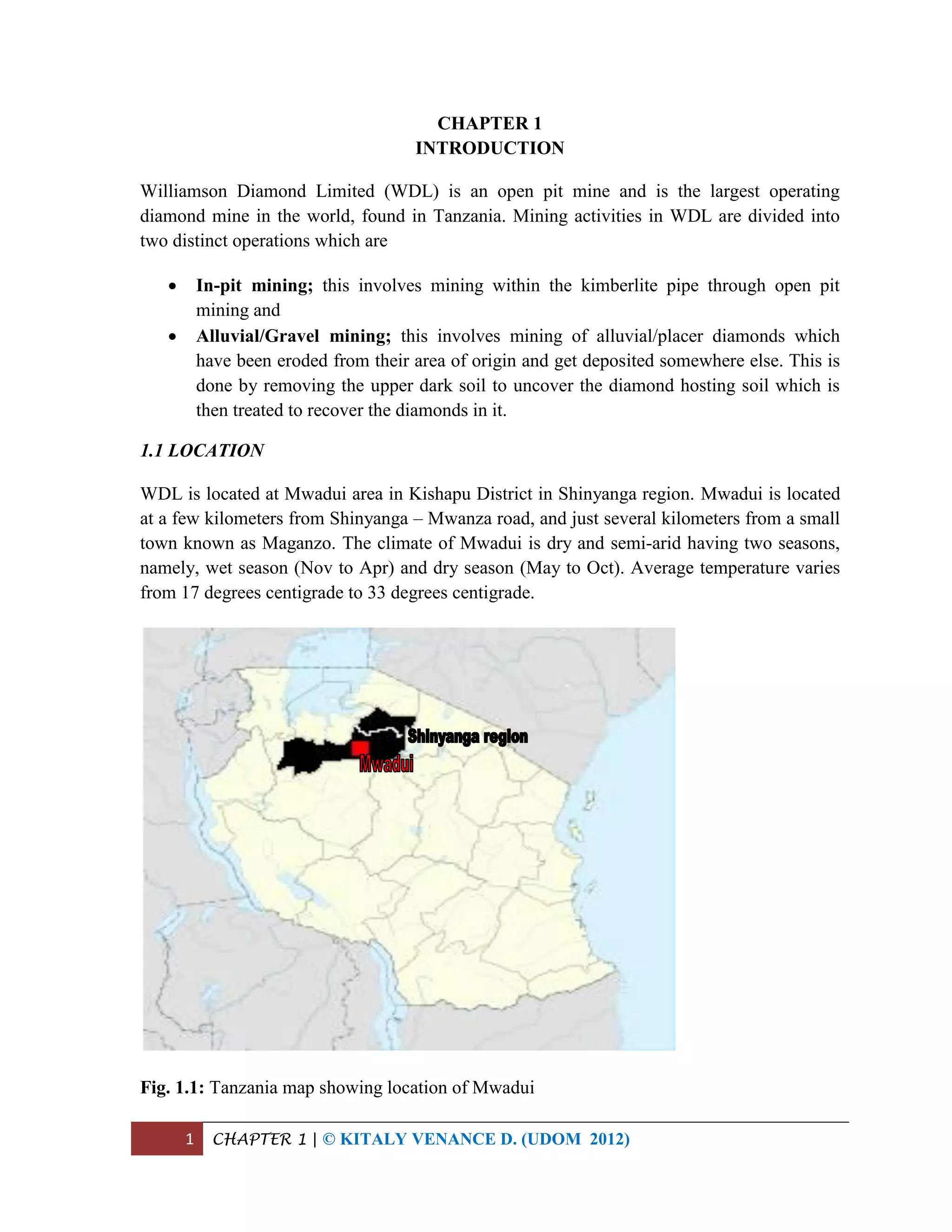

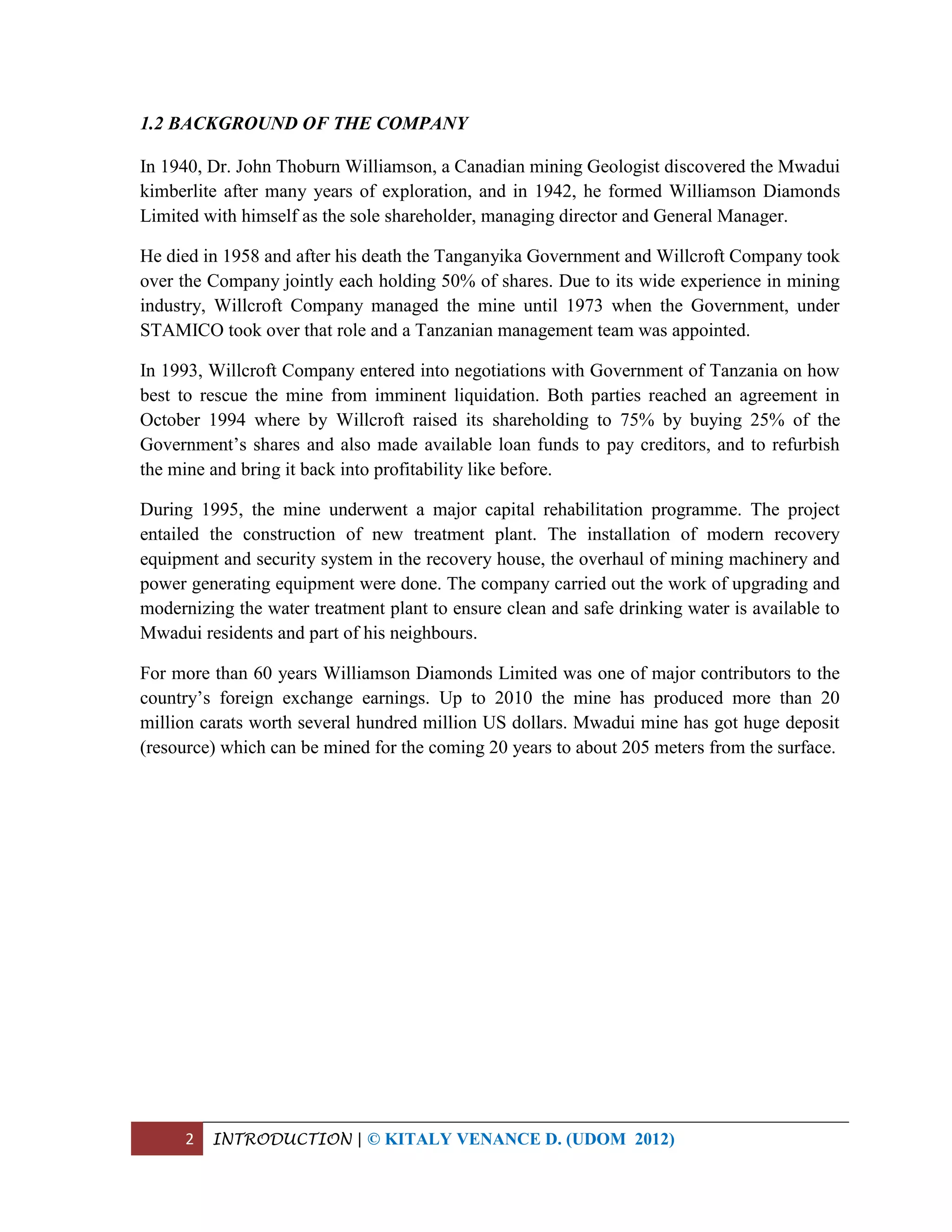

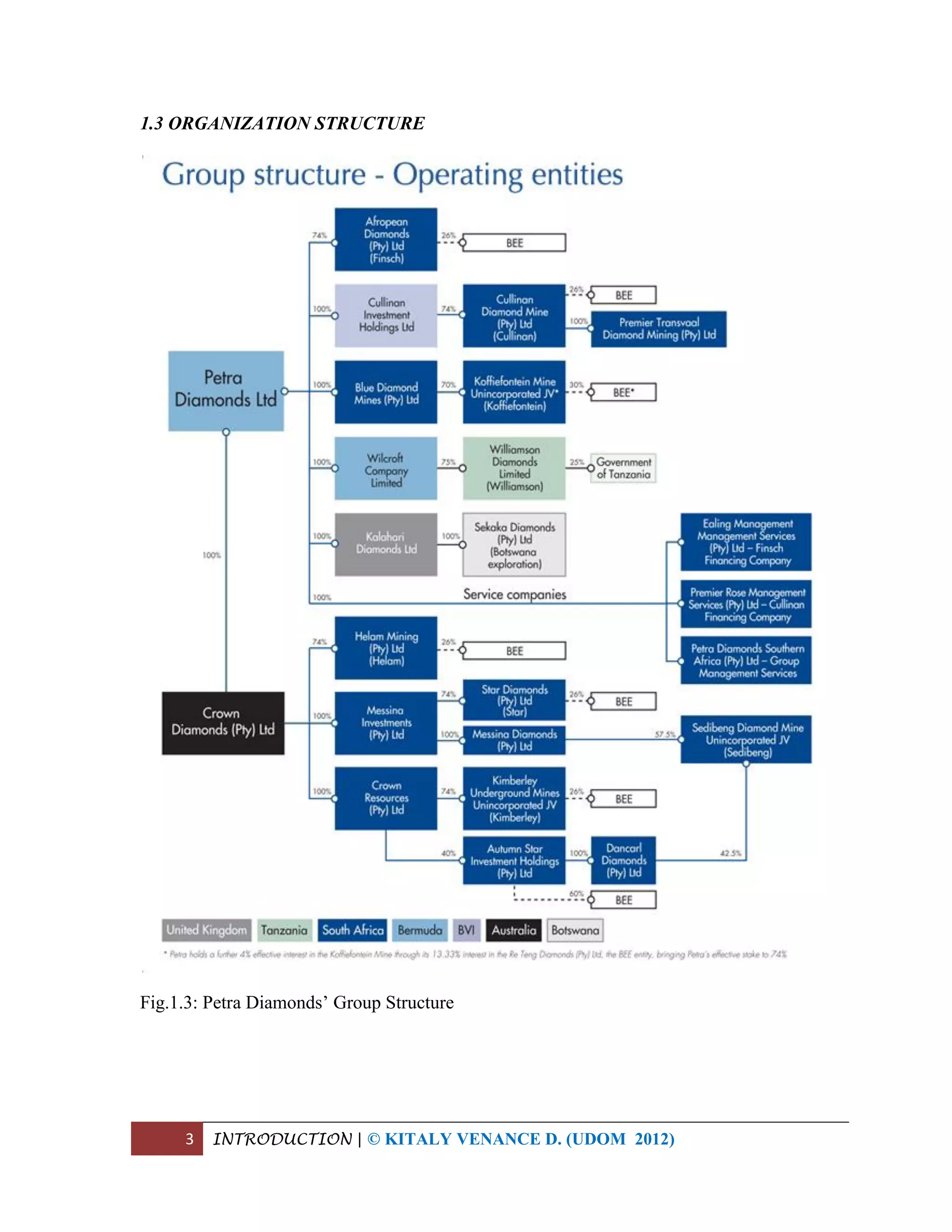

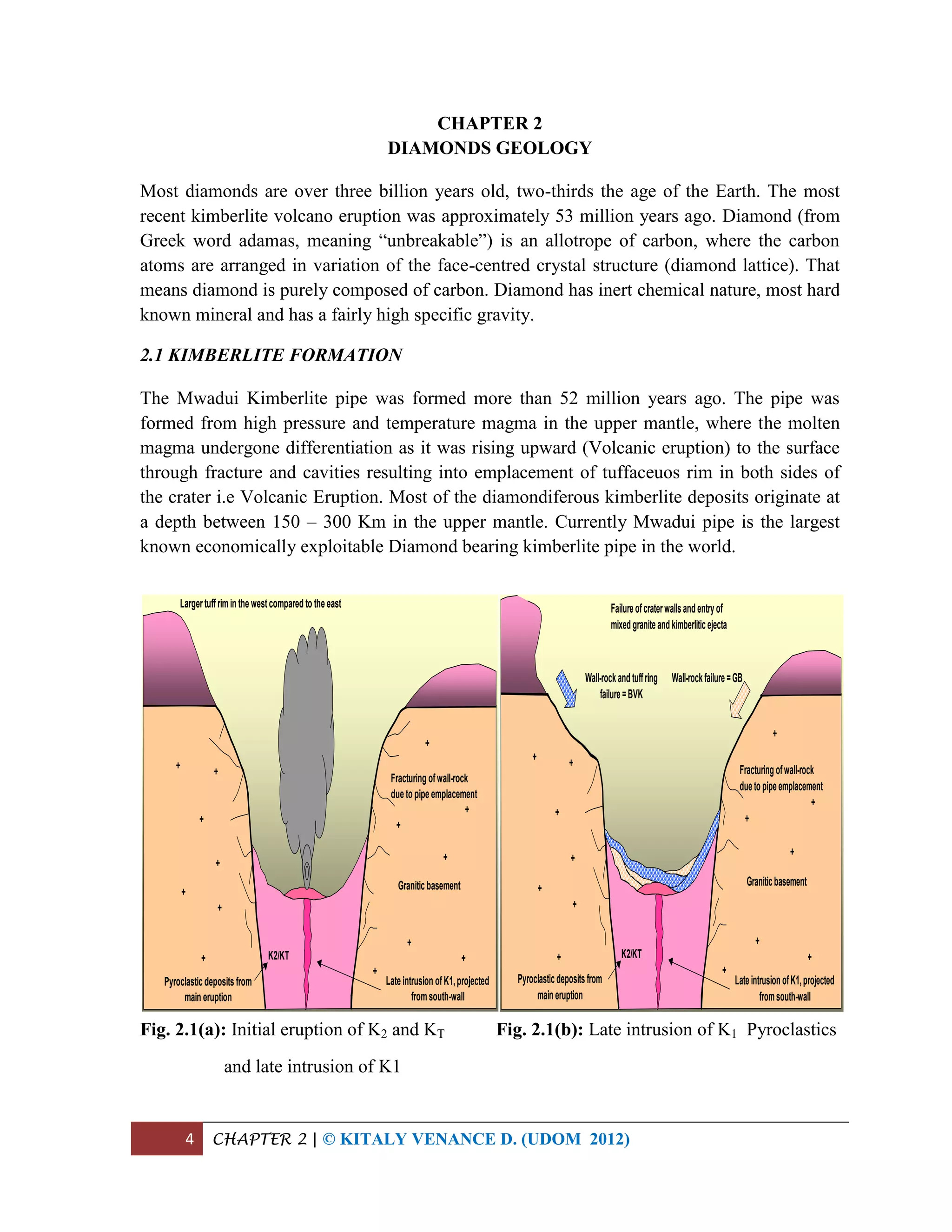

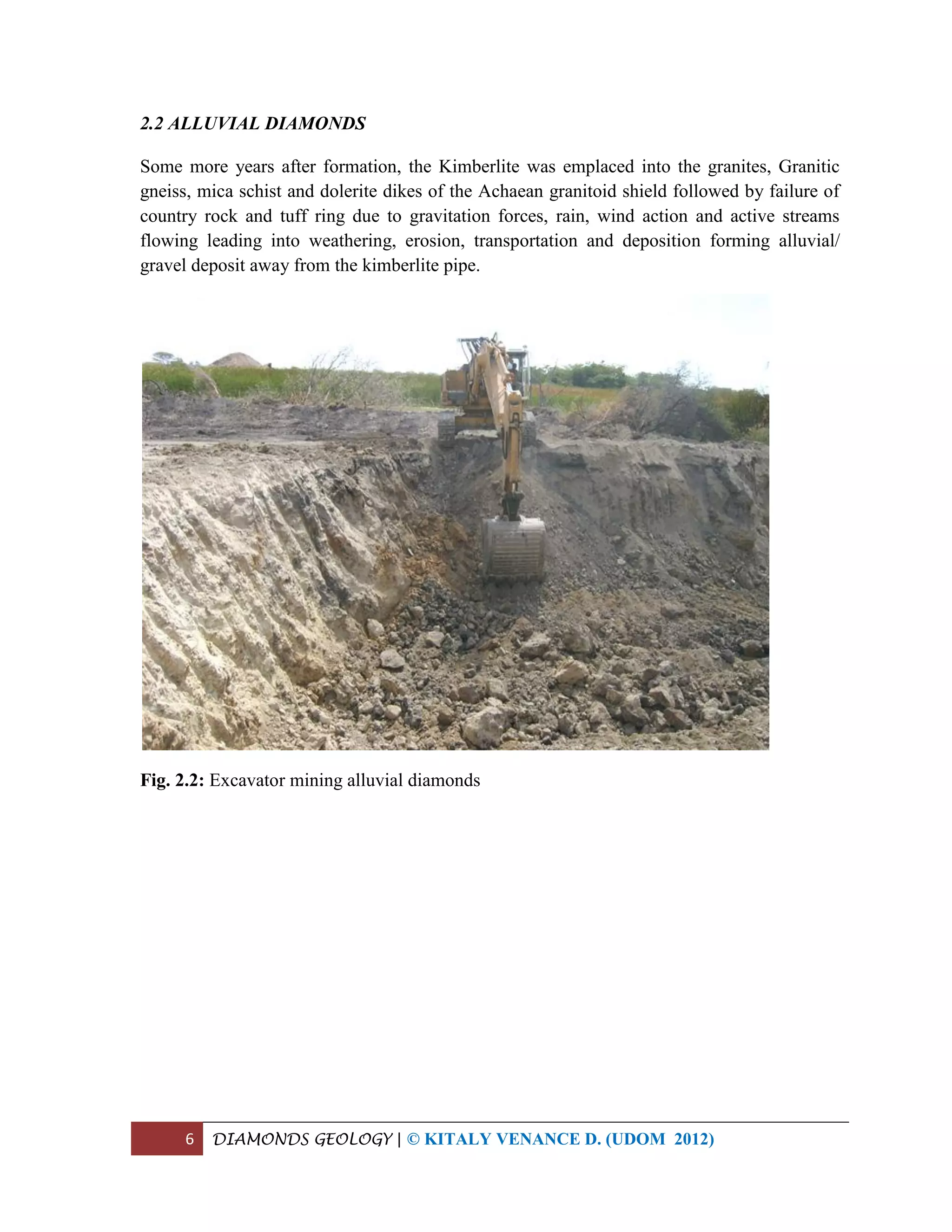

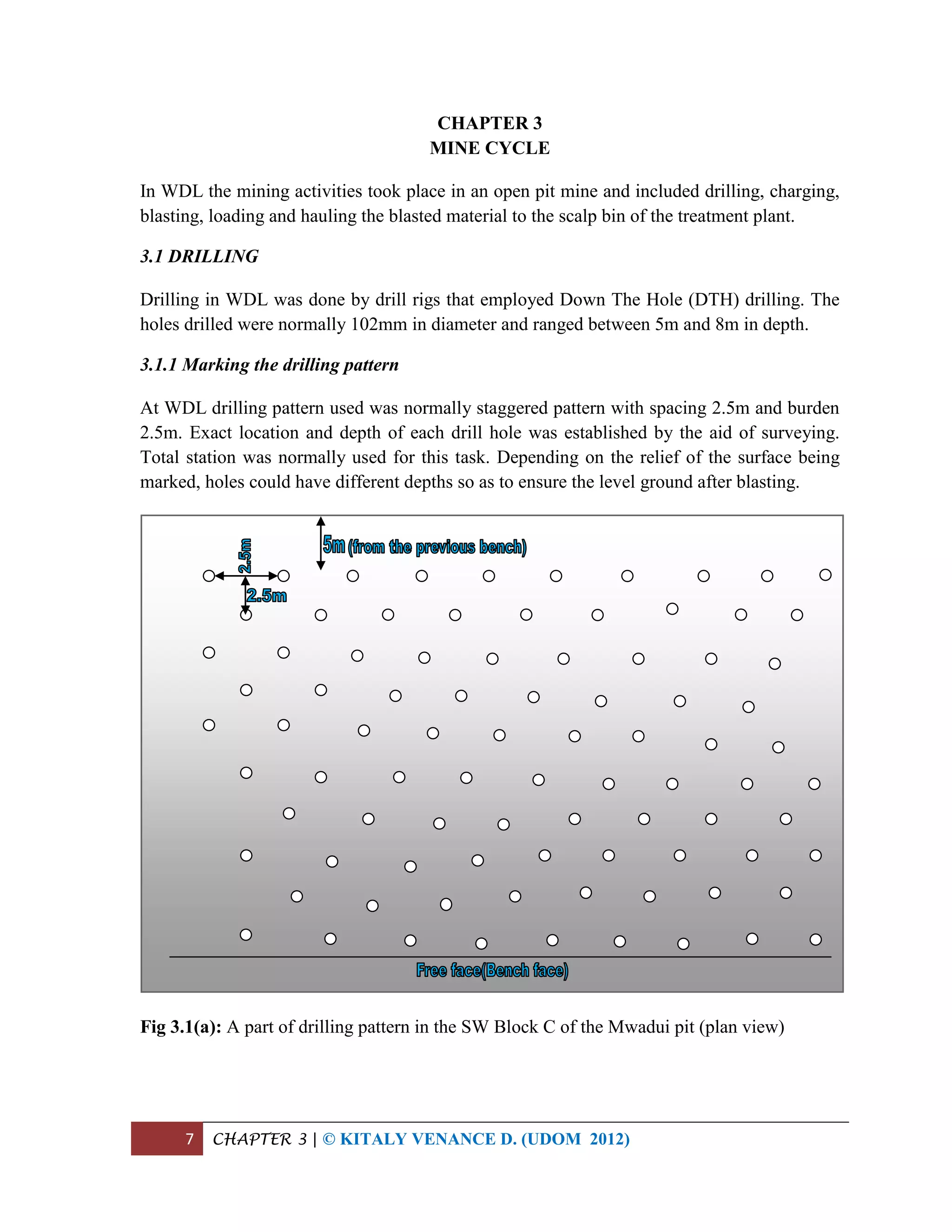

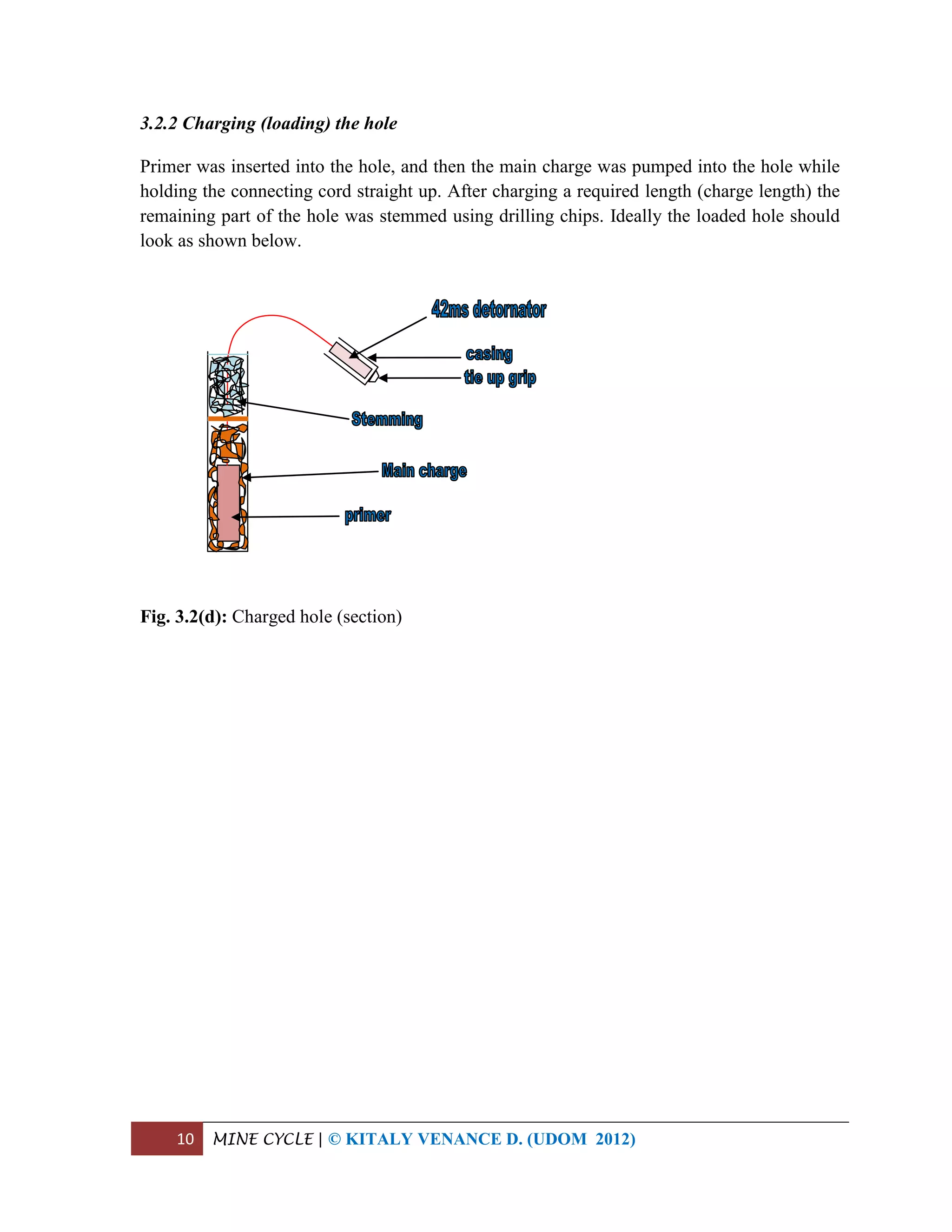

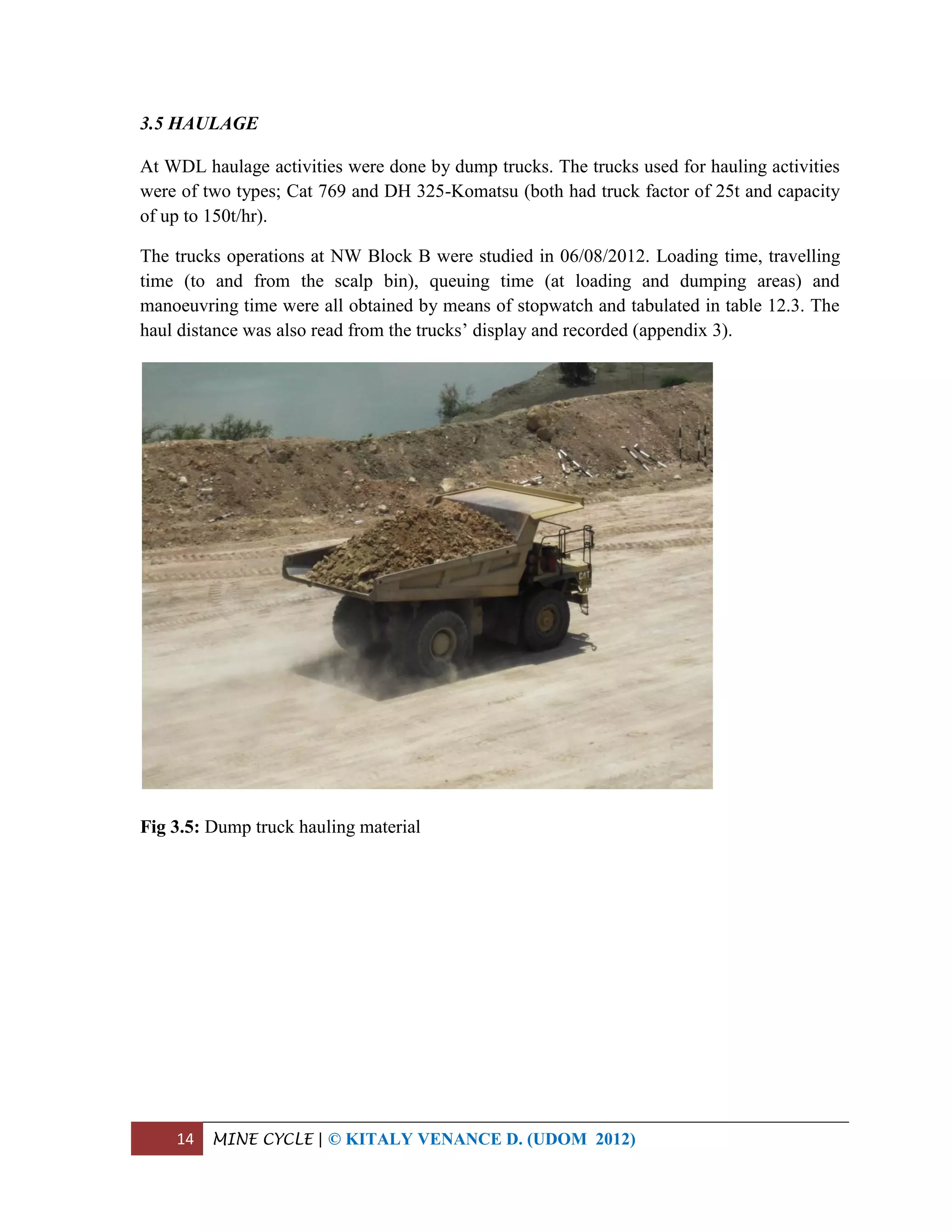

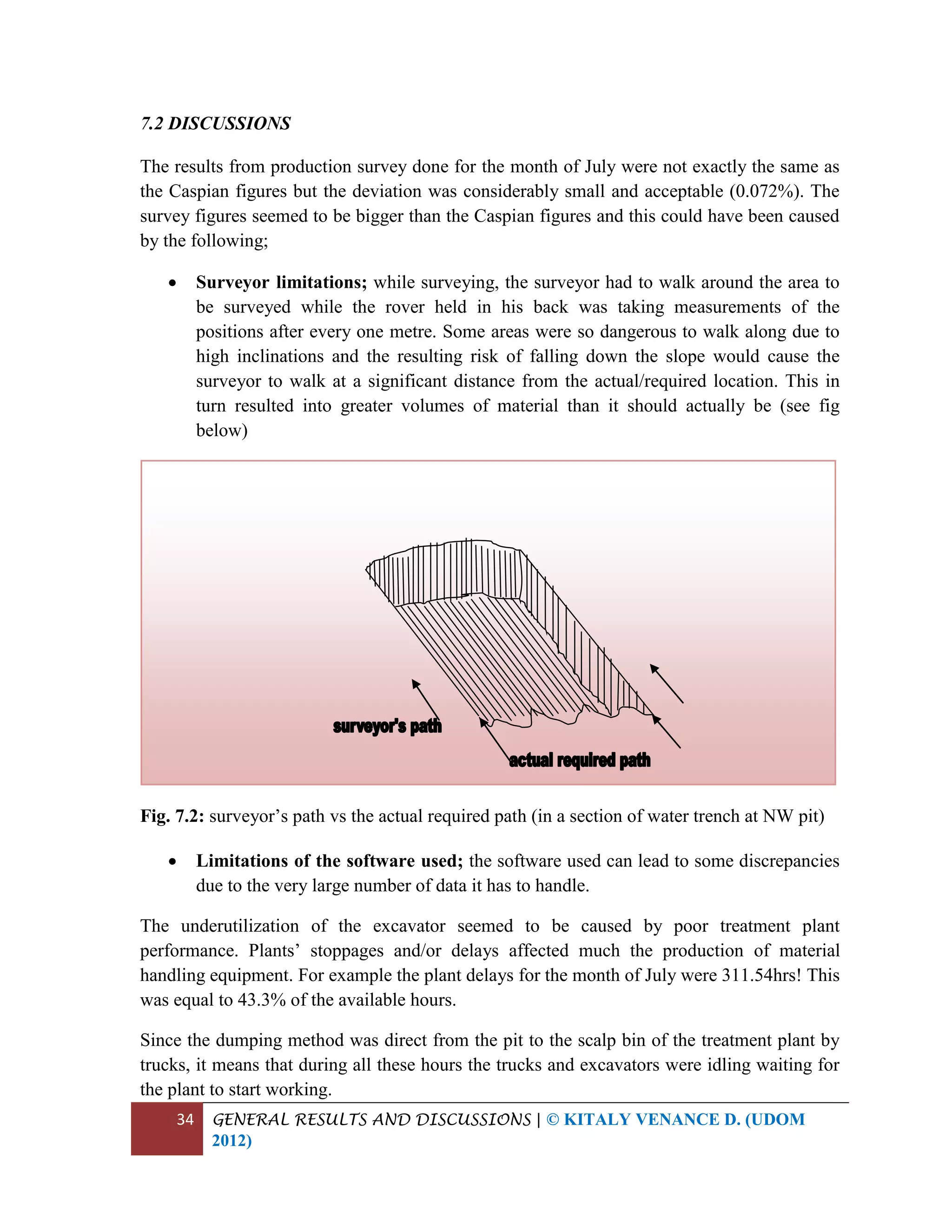

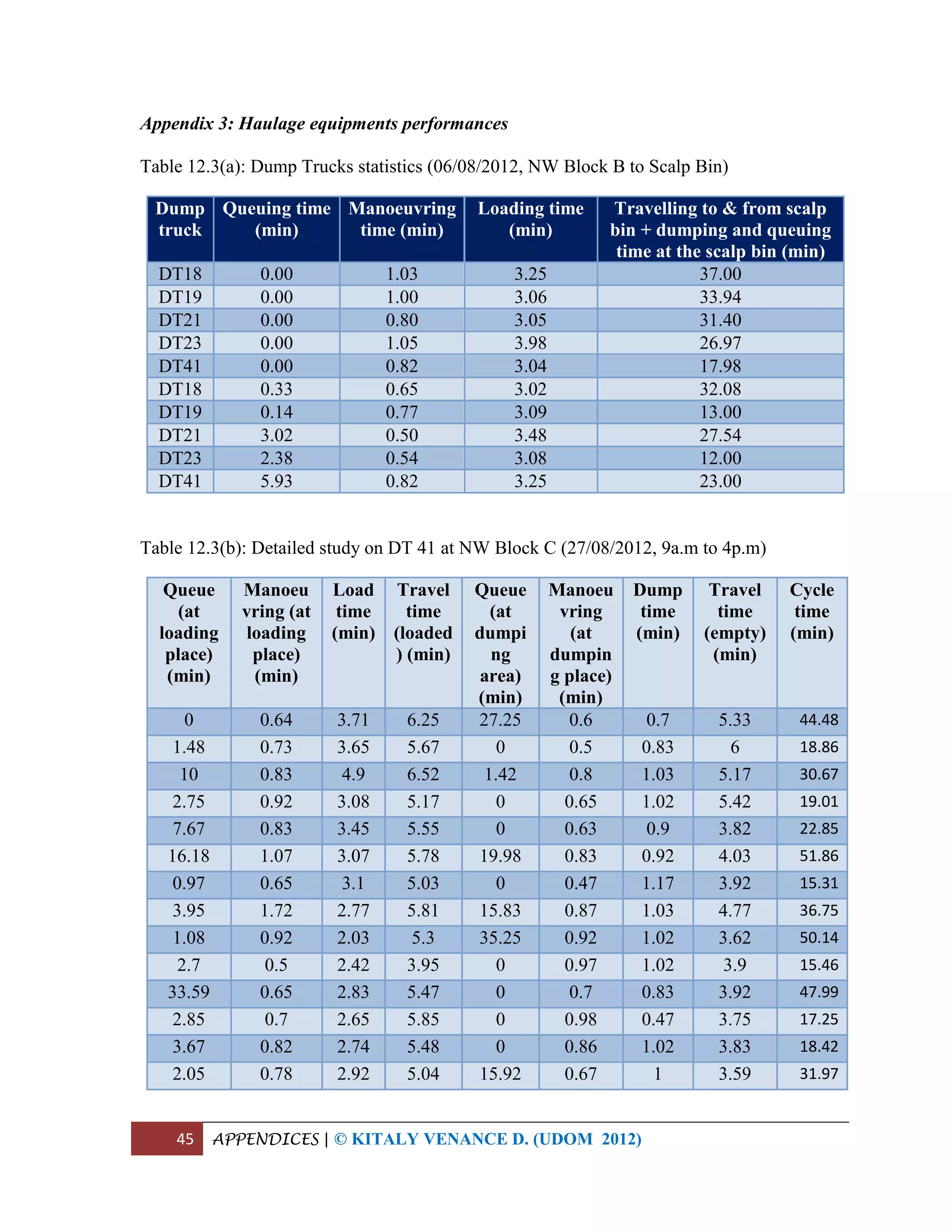

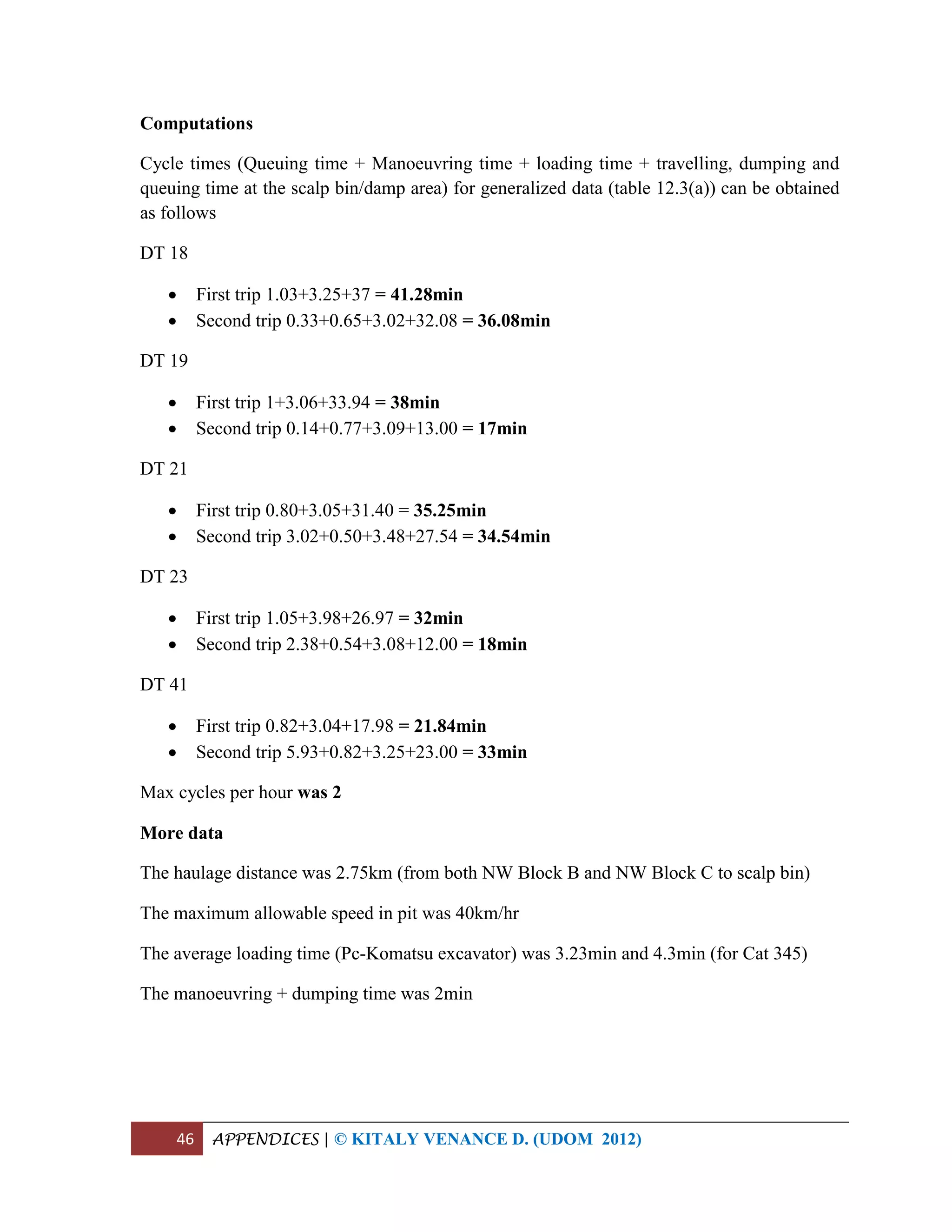

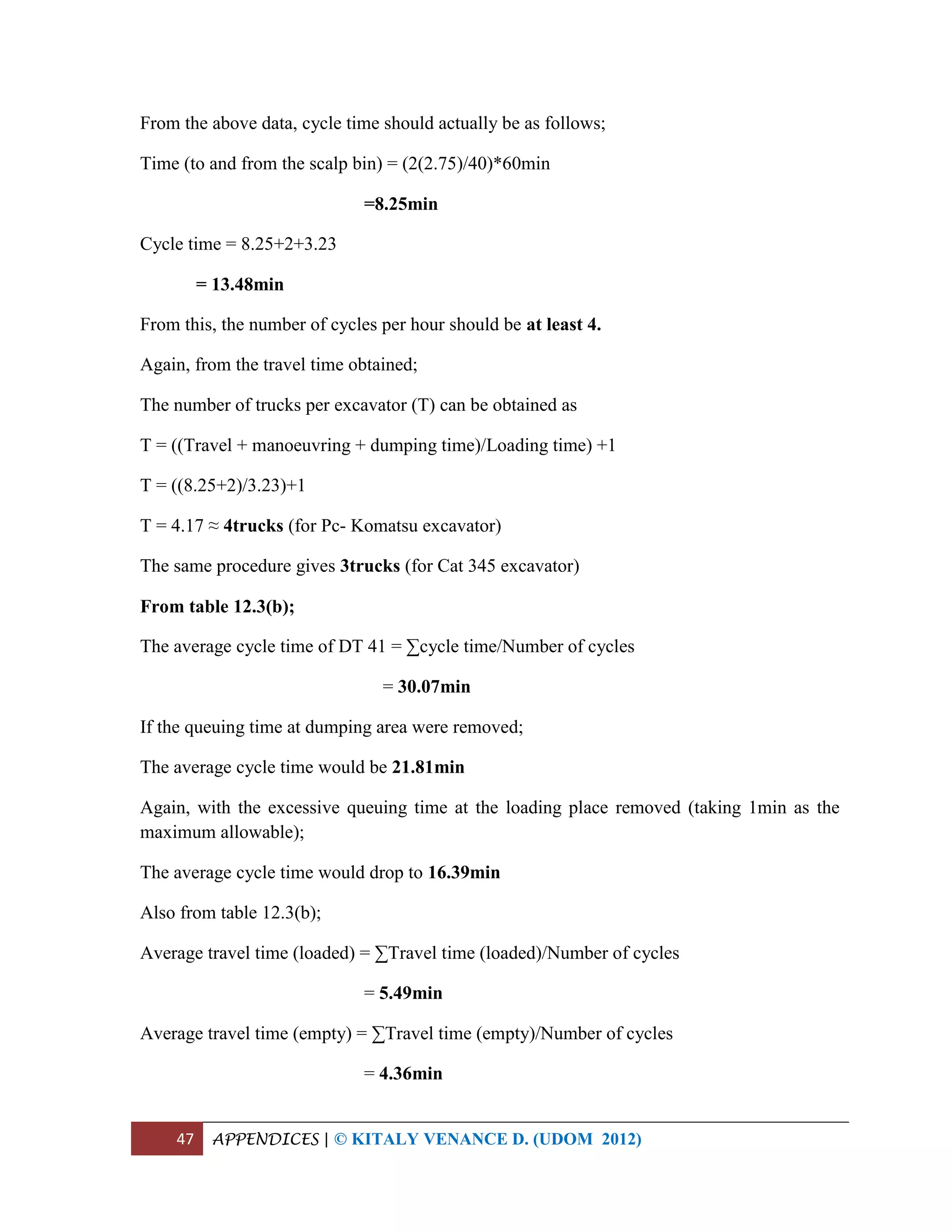

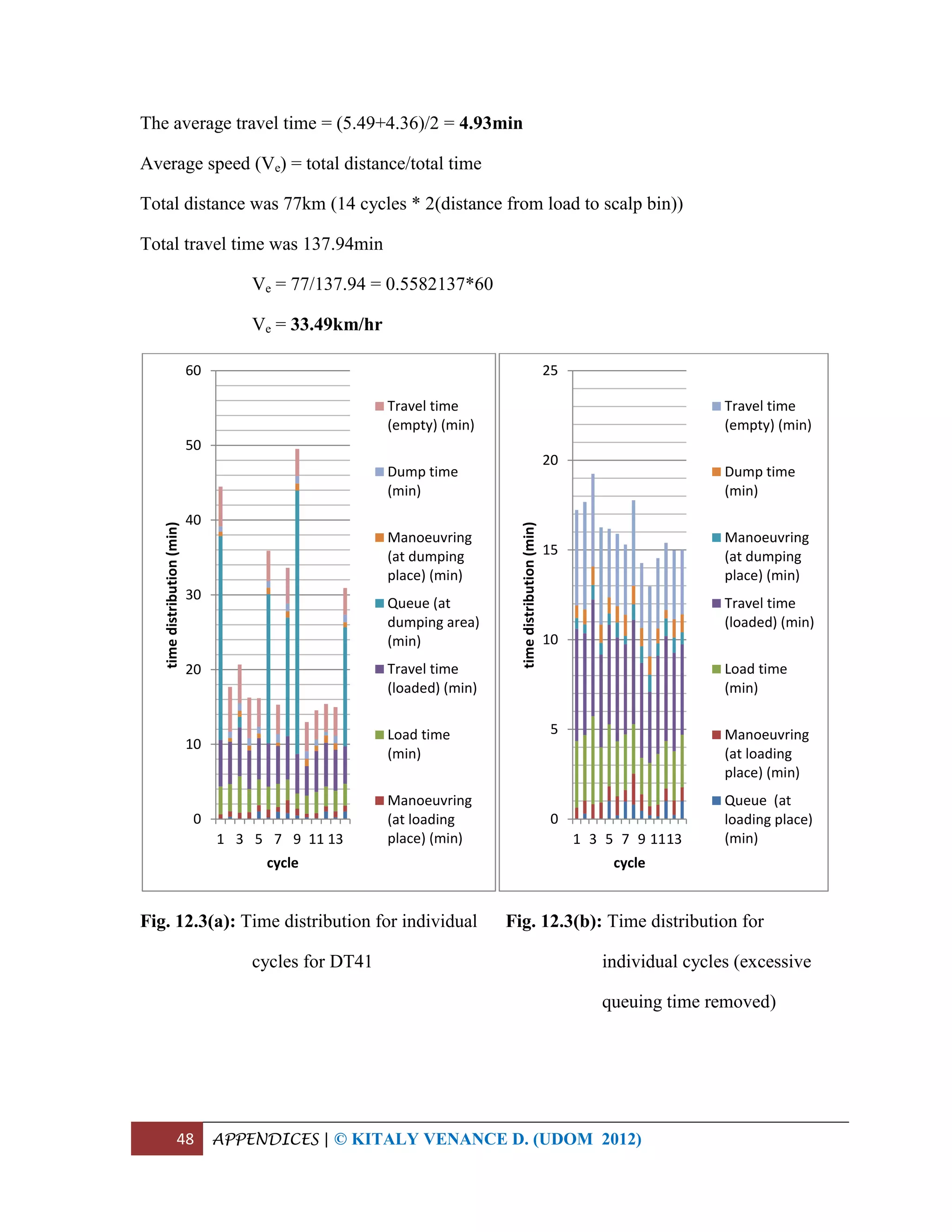

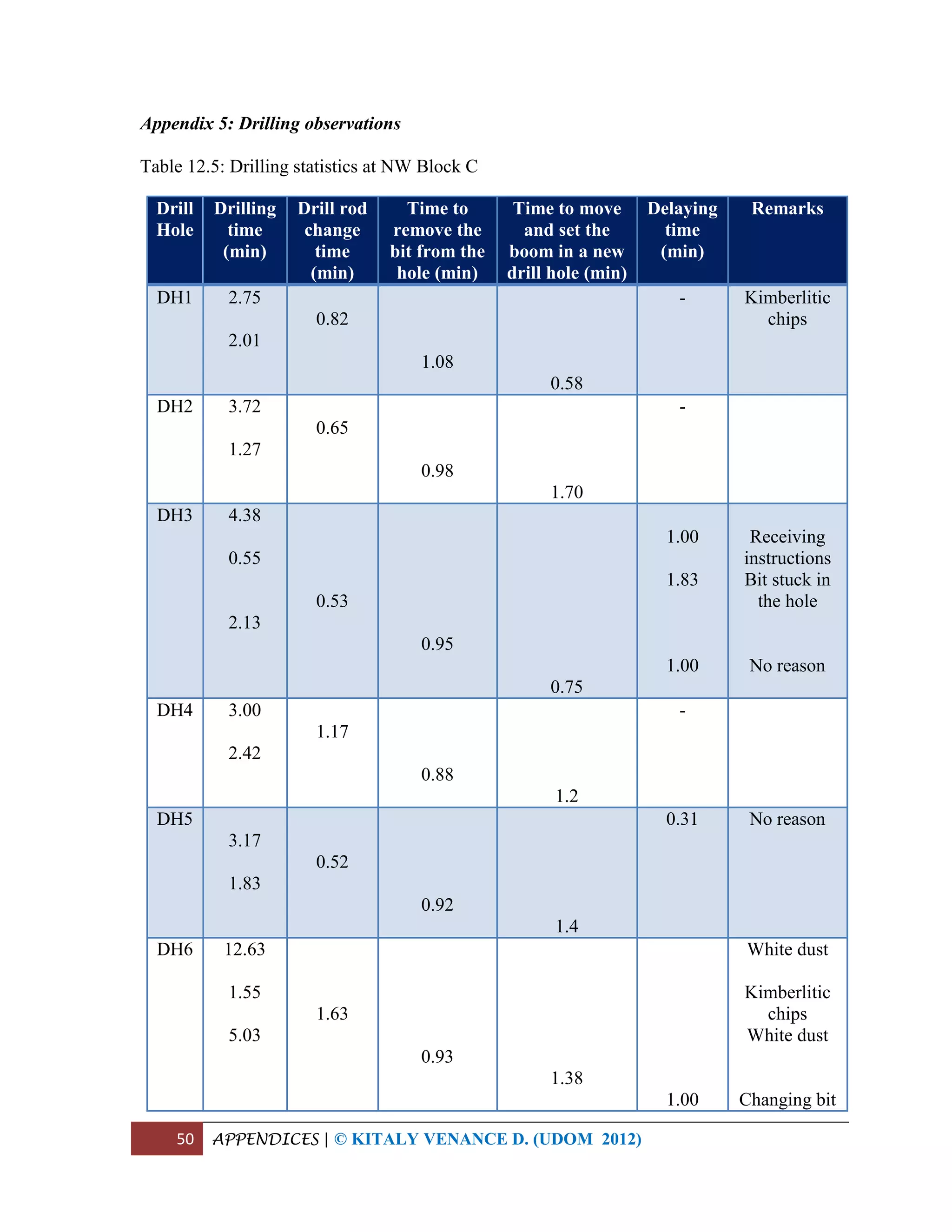

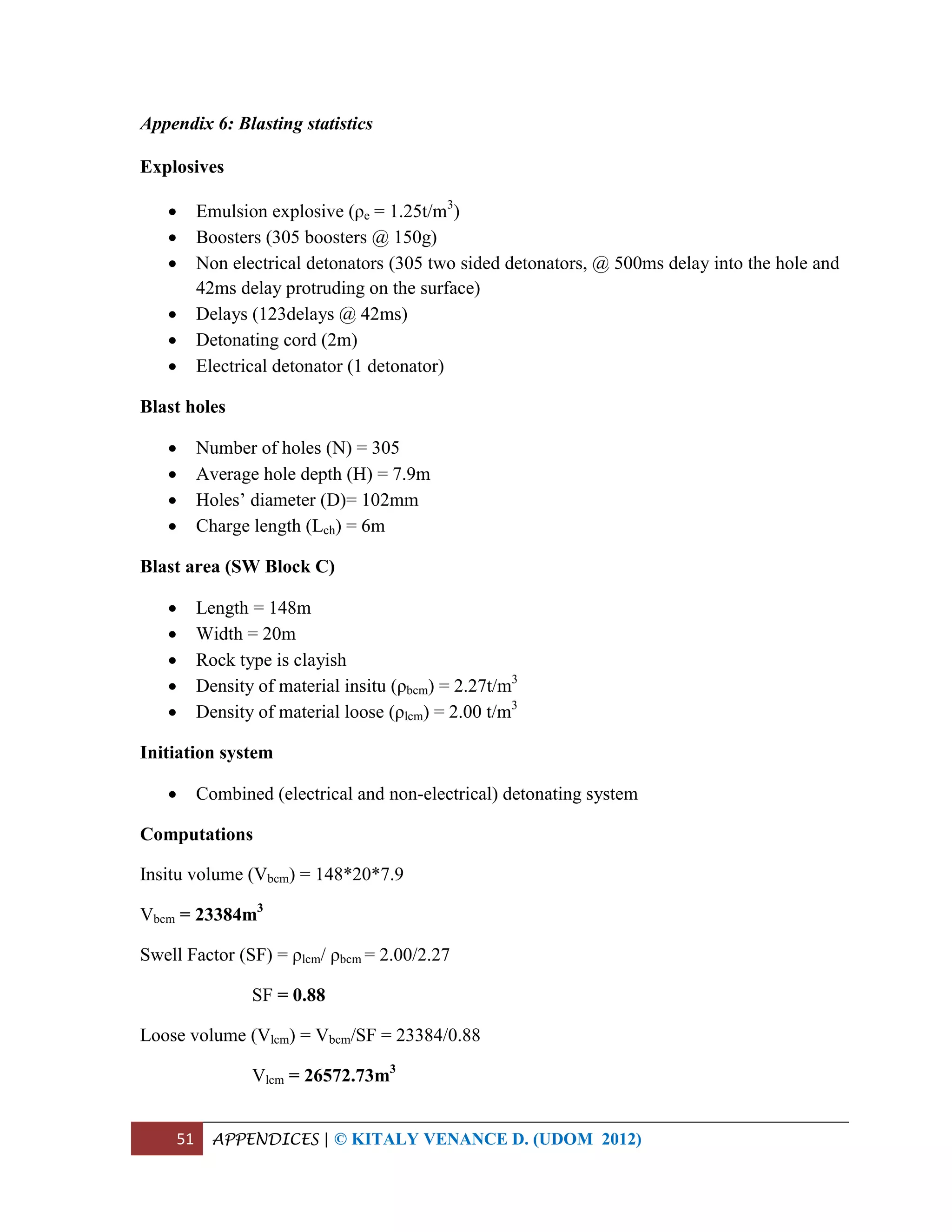

This document is a report from a student's practical training at Williamson Diamonds Limited-Mwadui mine. It includes acknowledgments, an abstract, table of contents, and sections on mine geology, the mining cycle of drilling, blasting, loading and haulage. It also covers mine safety, economic aspects like production surveys and cost estimates, and a project analyzing loading and haulage equipment productivity. The student directly observed operations and collected data on excavator and truck performance to analyze cycle times and recommend improvements to increase productivity and reduce costs.