This document describes Walter Jesuslee Savio Rodrigues' PhD dissertation from the University of Rome Tor Vergata. The dissertation focuses on accelerating atomistic simulations of nanostructured devices using graphics processing units (GPUs). It presents GPU implementations of eigenvalue solvers like the Lanczos method and benchmarks their performance. Applications to realistic nanostructure simulations are also demonstrated. The goal of the work is to make large-scale atomistic simulations more accessible to researchers by taking advantage of modern GPU hardware.

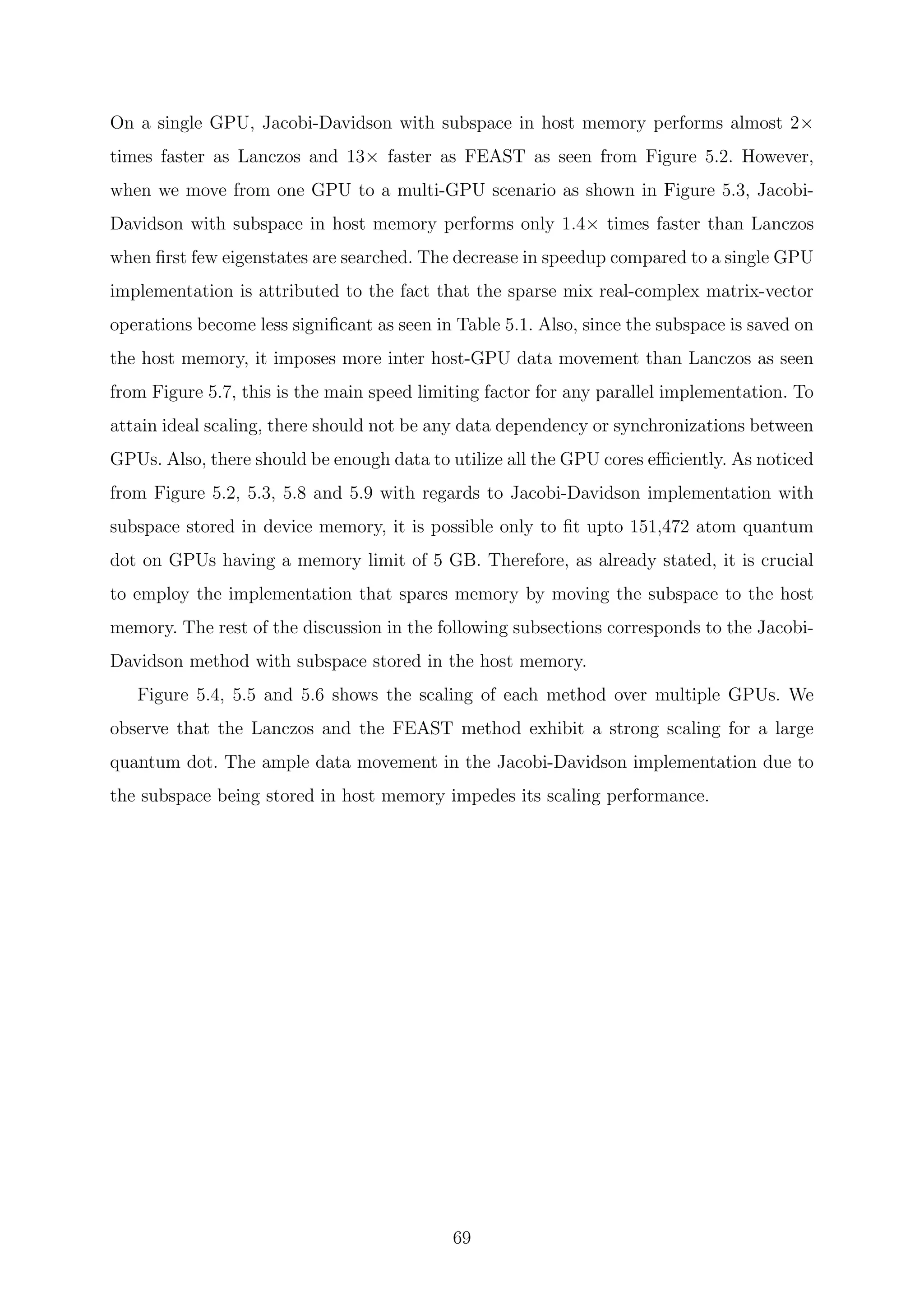

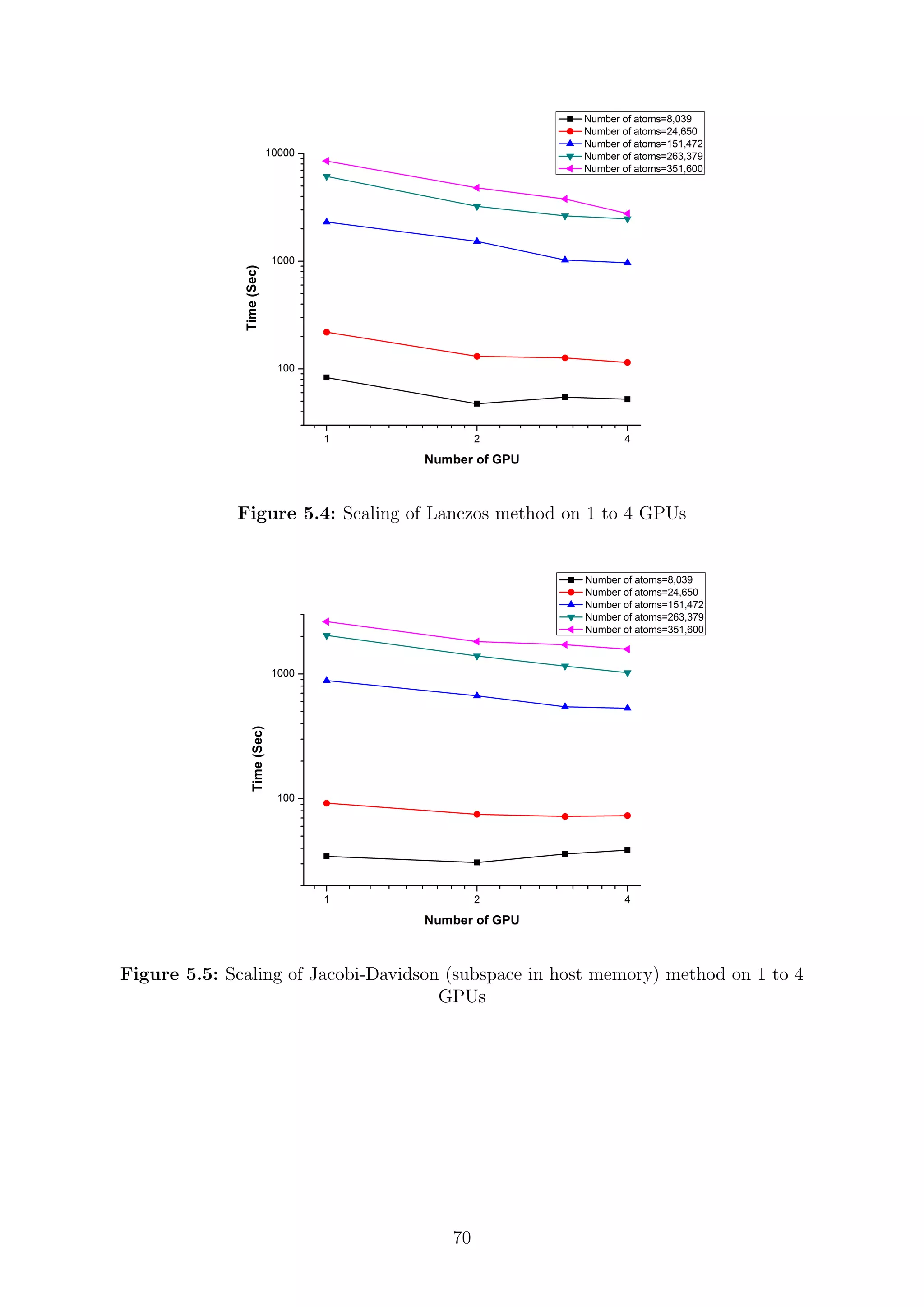

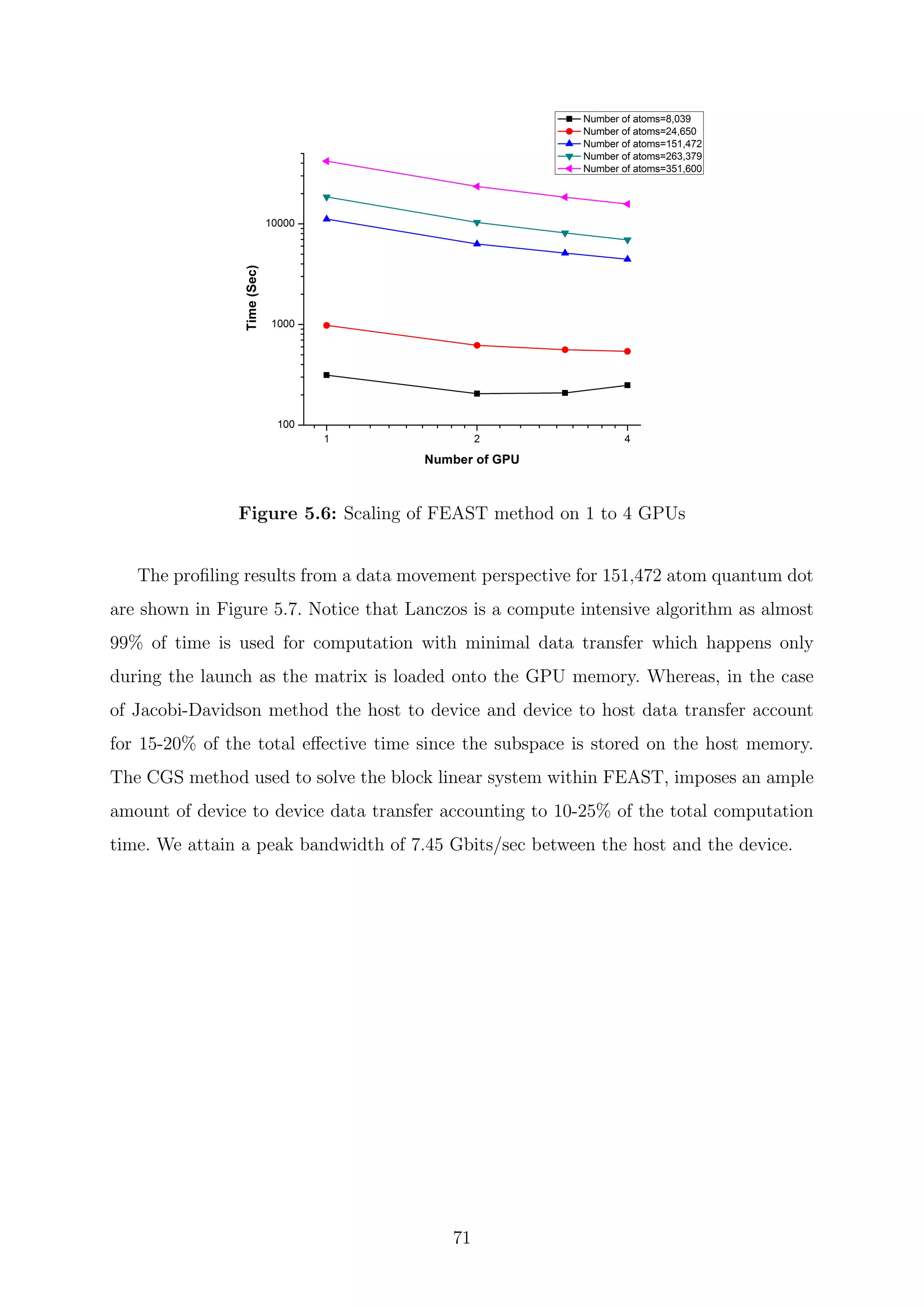

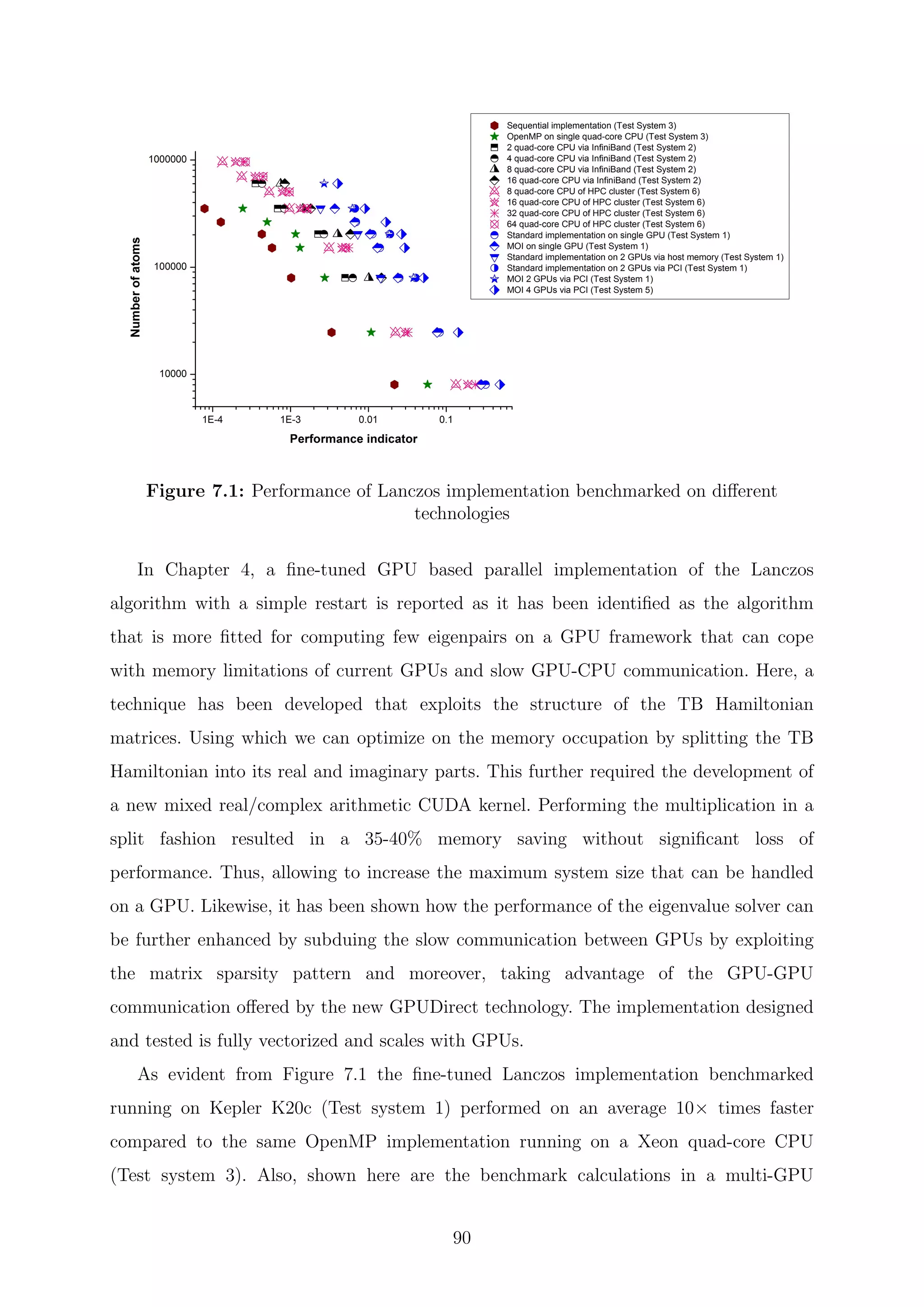

![Chapter 1

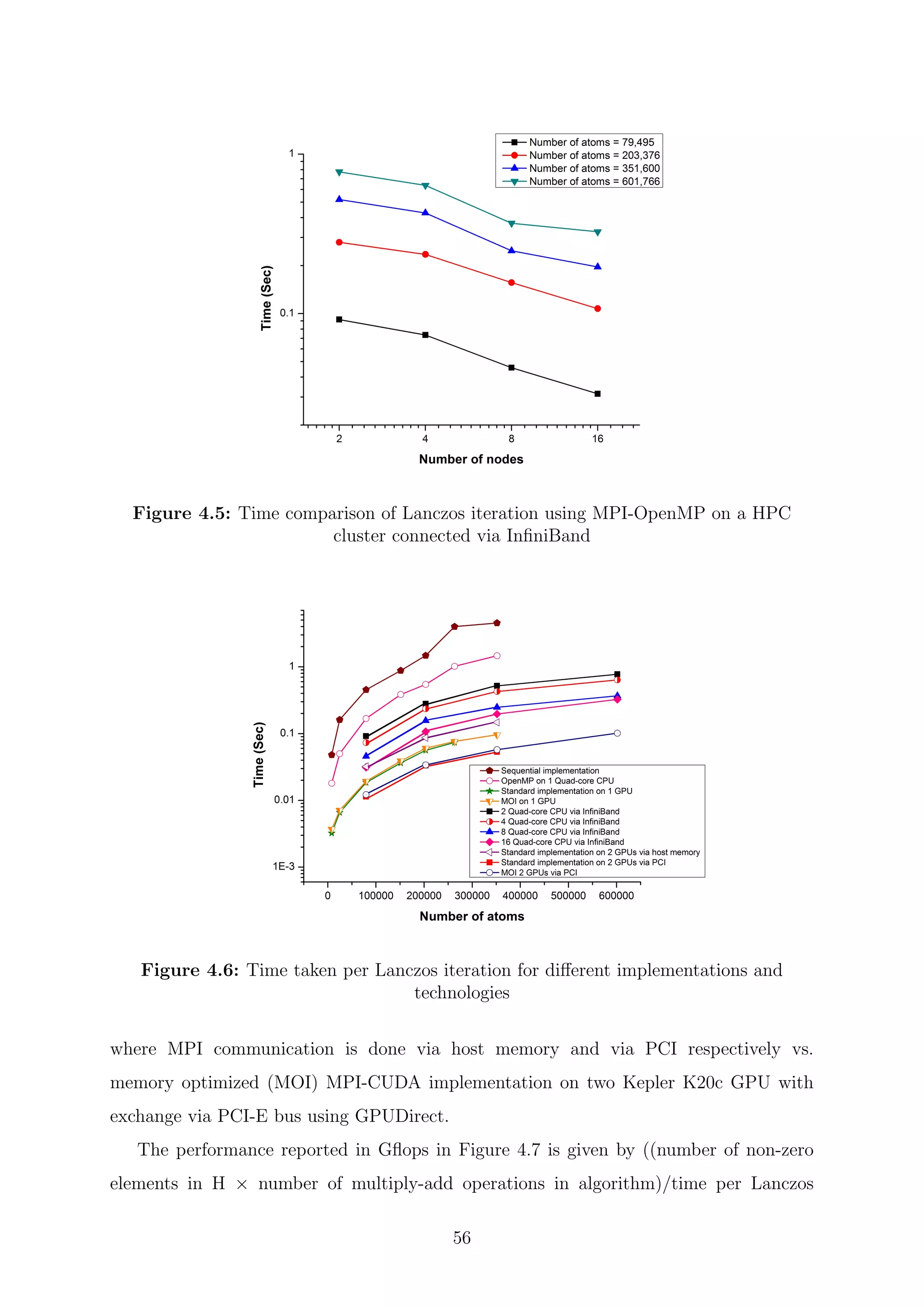

Introduction to tight binding model

and its computational challenges

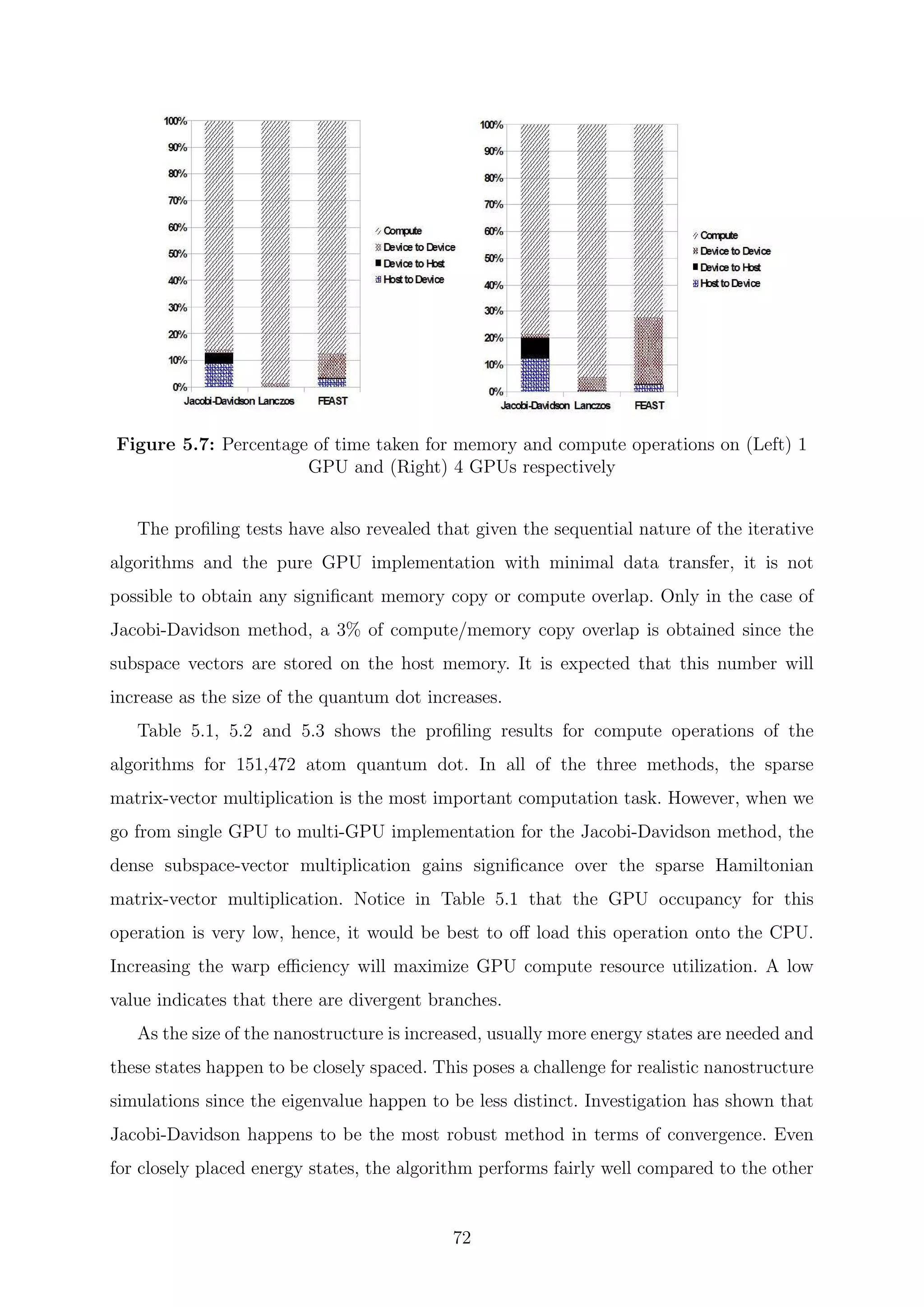

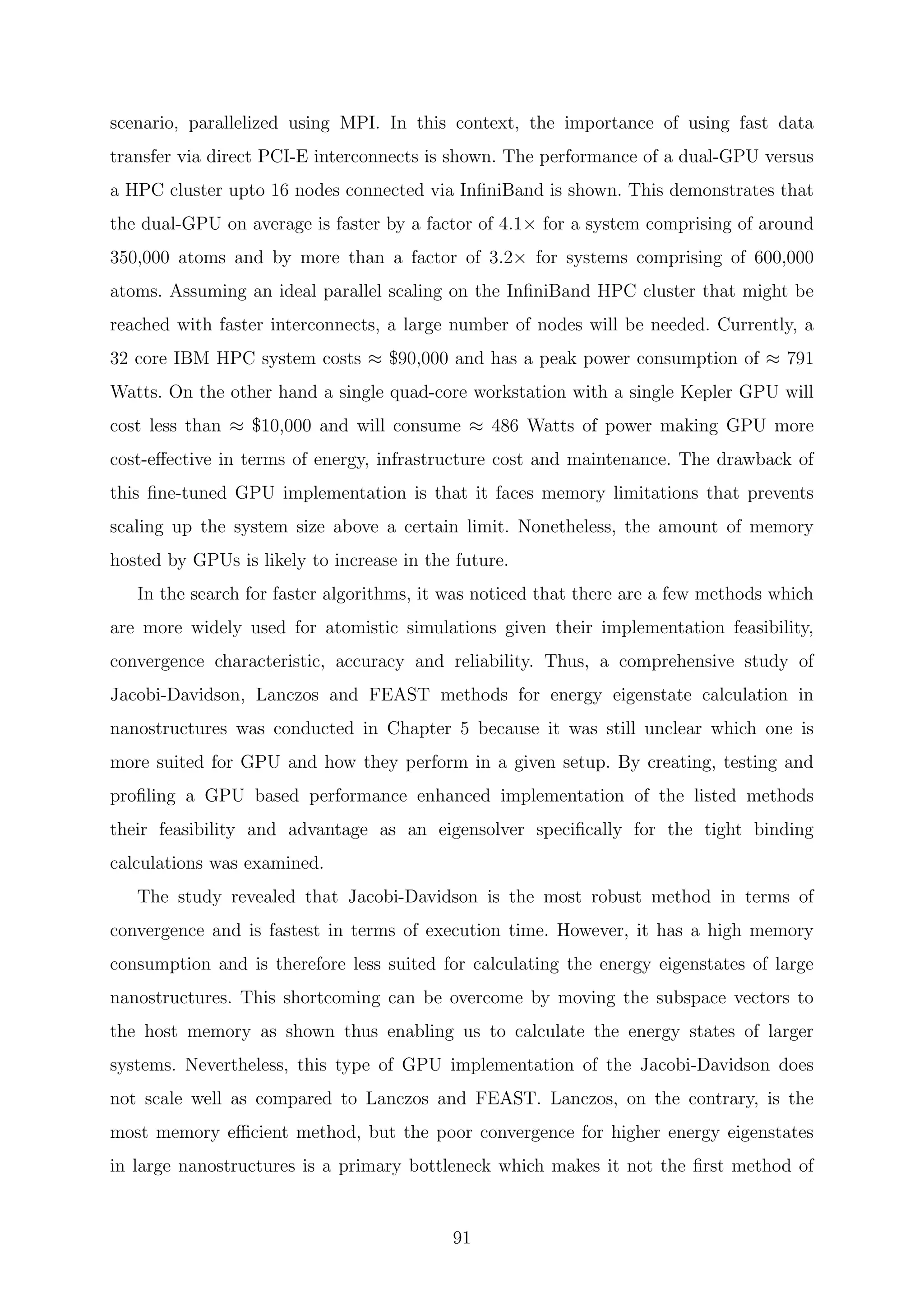

The birth of the use of computer simulations occurred around couple of decades ago,

but their impact in modern science has exactly mirrored the exponential growth in the

power of computers. In recent times, almost all fields of sciences have seen an explosion

of the use of computer simulations to the point where computational methods now stand

alongside with theoretical and experimental methods in value [1]. In turn, the growing

power of computers have spurred the development of methods and scientific software

packages, widening the potential of simulations to tackle a wide range of scientific issues

and placing sophisticated tools in the hands of a wider group of scientists.

Atomistic simulations are playing an increasingly important role in realistic,

scientific and industry applications in many areas including advance material design,

nanotechnology, modern chemistry and semiconductor research. Atomistic simulation is

the theoretical and computational modeling of what happens at the atomic scale in

solids, liquids, molecules and plasmas. Often, this means solving numerically the

classical or quantum-mechanical microscopic equations for the motion of interacting

atoms, or even deeper electrons and nuclei. Atomistic simulation is used to interpret

existing experimental data and predict new phenomena, to reach computationally where

simple theory alone cannot and to provide a way forward where experiments are not yet

possible. The predictive capability of these simulation approaches hinges on the

accuracy of the model used to describe atomic interaction. Modern models are optimized

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-11-2048.jpg)

![to reproduce experimental values and electronic structure estimates for the forces and

energies of representative atomic configuration deemed important for the problem of

interest.

Most solid-state applications are now making heavy use of density functional theory

(DFT) which has proved to be extremely successful in studying structural properties

and electronic states of materials from which formation energies, phase stability and

thermodynamic properties can be understood or even predicted. Many particle

corrections can be introduced as a perturbation, allowing also the exploration of optical

properties. Localized basis approaches like the Gaussian orbitals, wavelets or the

augmented-plane wave methods are used for calculating the electronic band structure of

solids allowing the prediction of many important properties [2]. All these methods

involve the development of quite complicated computer codes. Limited computational

resources, however, impose restrictions on both the system size and the level of theory

that can be used to calculate interaction between electrons and ions. In order to

overcome these limitations, more approximate methods have been developed and

advance optimization tactics either theoretical or practical are widely welcomed.

1.1 Empirical tight binding model

The model name “tight binding” suggests that it describes the properties of tightly

bound electrons in solids. The electrons in this model are considered to be tightly bound

to the atom to which they belong and they have limited interaction with states and

potentials of surrounding atoms. As a result, the wave function of the electron is rather

similar to the atomic orbital of the free atom to which it belongs. The energy of the

electron is close to the ionization energy of the electron in the free atom or ion because

the interaction with the potentials and states of neighboring atoms is limited. The tight

binding (TB) approach to electronic structure is one of the most used methods in solid

state systems [3]. The empirical tight binding (ETB) method, which dates back to the

work of Slater and Koster [4] assumes mostly two-center approximation and the matrix

elements of the Hamiltonian between orthogonal and atom-centered orbitals [5] are

treated as parameters fitted to experiment or first-principles calculations. ETB is widely

employed for the description of electronic structure of complex systems [6] like interfaces

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-12-2048.jpg)

![and defects in crystals, amorphous materials, nanoclusters, and quantum dots because it

is computationally efficient and provides physically transparent results. Indeed this

technique requires a relatively small number of parameters which are fitted to accurately

reproduce a given set of experimental data.

As stated, ETB considers a system where electrons are bound to atoms and the

perturbation produced from the linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) [4, 16]

(e.g. sp3

, sp3

d5

, etc). ETB employs an implicit basis composed of the localized

atomic-like orbitals in order to describe the band structure, but do not involve the direct

computation of inter-atomic overlaps. Consequently, many authors define ETB as a

formal expression over Wannier function. The Hamiltonian matrix elements are typically

obtained empirically from fits to more accurate calculations, experiments or derived

from first-principles expressions [7,8]. The ETB method used for calculations of particles

state of atomistic systems [9, 10] is generally less accurate and less transferable than

methods based on DFT, where the Hamiltonian is computed from explicit wave

functions, but it does provide a good alternative for simulating systems of larger

size [11] and over longer time scales than are currently tractable using first-principles

methods. In fact, the ETB is the model of choice for atomistic description of the

electronic properties of nanostructured devices [12–15].

According to the macroscopic device description and crystallographic orientation, the

atomistic structure needed for ETB calculations is generated internally in TiberCAD,

a multiscale CAD tool for the simulation of modern nanoelectronics and optoelectronics

devices [17]. The atomistic structure is deformed based on the strain calculations obtained

from a continuous media elasticity model by projecting the deformation field onto the

atomic positions [18]. In order to couple the atomistic calculation of electronic states

with the continuous media model for particle transport, the macroscopic electrostatic

potential calculated with the Poisson/drift-diffusion model has been projected onto the

atomic positions in a multiscale fashion [19]. The solution of the eigenvalue problem

resulting from the ETB provides the quantum energy eigenstates and consequently the

charge density. An ETB model based on a sp3

d5

s∗

+ spin-orbital parametrization has

been applied in this work [7].

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-13-2048.jpg)

![1.2 Mathematical formulation for empirical tight

binding model

ETB describes the system Hamiltonian (H) taking the linear combination of localized

orbitals centered on each atom position [20]. The function

|Ψ =

α,R

Cα(R)|α, R (1.1)

represents standing waves or atomic orbitals. Which is necessary to find an

approximation of the eigenenergies and a set of expansion coefficients Cα [21].

In the quantum atomistic approach, the energy levels, , of the stationary states can

be seen as the eigenvalues of the matrix H,

H|Ψ = |Ψ (1.2)

which is the time-independent Schr¨odinger equation. ETB, widely explained elsewhere,

determines the energy of H in terms of energy levels by solving the secular equation

det|H − I| = 0 (1.3)

where I is the overlap matrix elements which reduces to unit matrix when neglecting

inter-atomic overlaps [20] and are the energy levels (eigenvalues).

The matrix H in equation 1.2 for the sp3

d5

s∗

parametrization used here [7] includes the

spin-orbit interactions forming a block matrix of 20×20 for each atom. In later chapters

we shall see at length methods to solve similar equations efficiently. The solution of the

eigenvalue problem defined in equation 1.2 provides the quantum energy eigenstates which

gives the charge density and allows the prediction of many other important properties of

the system.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-14-2048.jpg)

![1.3 Schr¨odinger equation and the eigenvalue

problem

The wavefunction for a given physical system contains the measurable information

about the system. To obtain specific values for physical parameters, for example energy

eigenstates, one operates on the wavefunction with the quantum mechanical operator

associated with that parameter. The operator associated with energy is the Hamiltonian

and the operation on the wavefunction is the Schr¨odinger equation as given in equation

1.2. Thus, the time-independent Schr¨odinger equation in a linear algebra terminology is

an eigenvalue equation for the Hamiltonian operator [23] which is explained in more

detail in Chapter 3.

Solutions exist for the time-independent Schr¨odinger equation only for certain values

of energy and these values are called “eigenvalues” of energy. The band energy states

form a discrete spectrum of values, physically interpreted as quantization. Corresponding

to each eigenvalue is an “eigenfunction”. More specifically, the energy eigenstates form a

basis. The solution to the Schr¨odinger equation for a given energy i involves also finding

the specific function |Ψi which describes that energy state. Any wavefunction may be

written as a sum over the discrete energy states or an integral over continuous energy

states, or more generally as an integral over a measure.

1.4 Computational challenges of empirical tight

binding method

The pursuit for ever higher levels of detail and realism in nanoelectronics simulations

presents formidable modeling and computational challenges. Over the last two decades,

available computer power has grown as well as the size of system that can be considered

employing the TB method has also grown. As the nanostructure systems become larger,

however, the issue of scaling becomes crucial. The number of computational operations

required to diagonalize a matrix is proportional to the cube of the number of basis

functions, and thus to the number of atoms. This behavior is referred to as O(N3

)

scaling. As a result, a thousand-fold increase in computer power only buys a ten-fold

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-15-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 2

Introduction to GPU and general

purpose GPU computing

In 1965, Gordon E. Moore made an interesting observation that the number of

transistors in a dense integrated circuit would double approximately every two

years [24, 25]. His prediction has proven to be accurate and is termed as the “Moore’s

law.” The exponential increase in the number of transistors on a chip has dramatically

enhanced the effect of digital electronics in nearly every segment of life. In the last few

decades, the microprocessor performance has drastically increased as a result of many

related advances like increased transistor density, increased transistor performance,

wider data paths, pipelining, faster processor speed, superscalar execution, speculative

execution, caching, chip and system-level integration. As of 2012, every square

millimeters of chip area has up to 9 million transistors. Microprocessors are easy to

program because compilers evolved right along with the hardware they run on [26].

Users can ignore most of the complexity in modern central processing unit (CPU) since

its microarchitecture is almost invisible.

Multi-core chips have the same software architecture as older multiprocessor systems,

a simple coherent memory model and a few identical computing engines [27,28]. However,

CPU cores continue to be optimized for single-threaded performance at the expense of

parallel execution. This fact is most apparent when one considers that integer and floating-

point execution units occupy only a tiny fraction of the die area in a modern CPU. With

such a small part of the chip devoted to performing direct calculations, it is no surprise

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-18-2048.jpg)

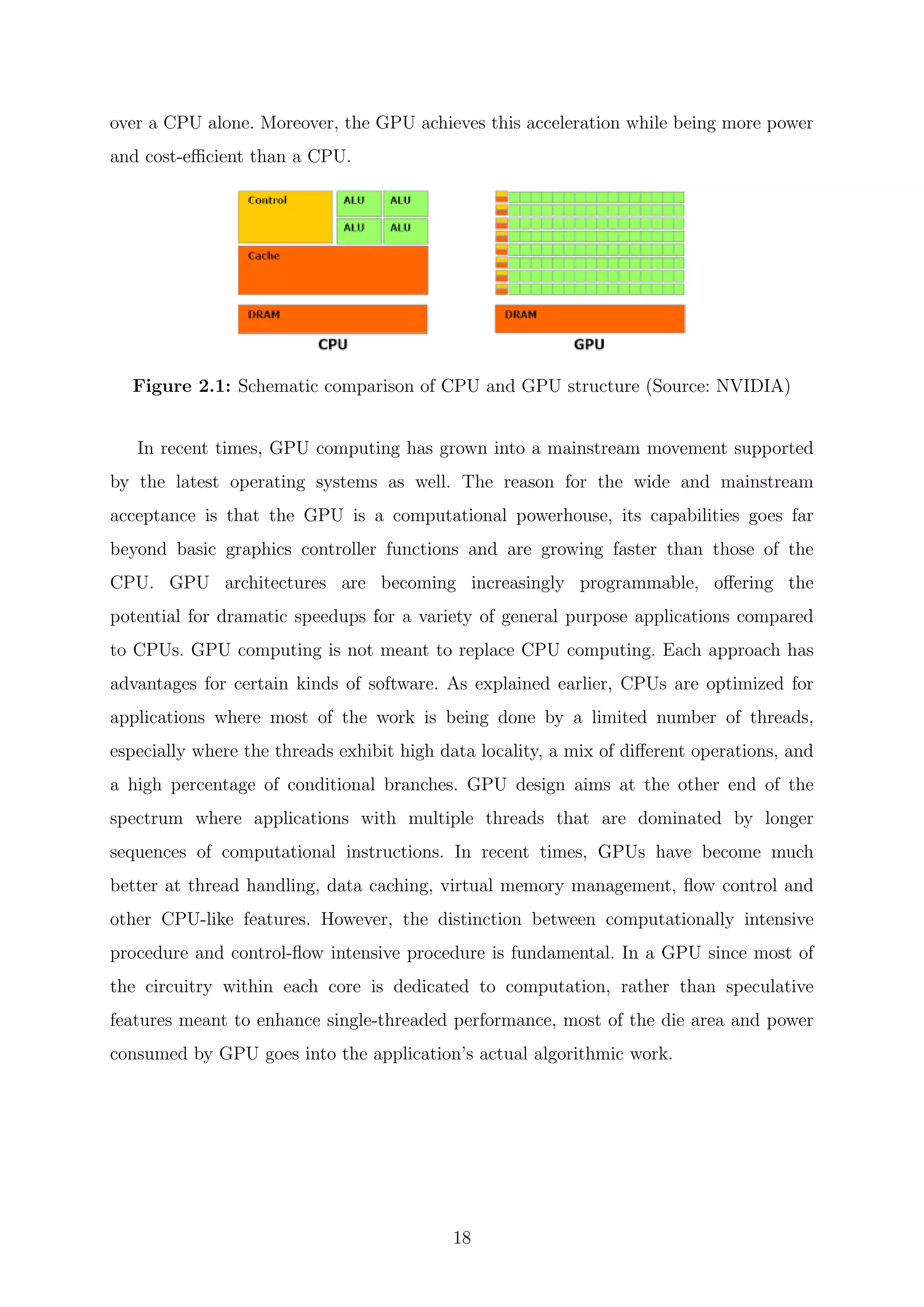

![that CPUs are relatively inefficient for HPC applications.

The need for CPU designers to maximize single-threaded performance is also behind

the use of aggressive process technology to achieve the highest possible clock rates.

However, this comes with significant costs. Faster transistors run hotter, cost more to

manufacture and leak more power even when they aren’t switching. Manufactures that

make high-end CPUs spend staggering amounts of money on process technology just to

improve single-threaded performance. The market demands general-purpose processors

that deliver high single threaded performance as well as multi-core throughput for a

wide variety of workloads. This pressure has given us almost three decades of progress

toward higher complexity and higher clock rates. Each new generation of process

technology requires ever more heroic measures to improve transistor characteristics.

These challenges have become more apparent in the late 20 century.

By 2005, the primary focus of processor manufactures have been to continue to increase

the core count on chips. This approach, however, has reached a point of diminishing

returns. Dual-core CPUs provide noticeable benefits for most CPU users, but are rarely

fully utilized except when working with multimedia content or multiple performance-

hungry applications. Most of the time quad-core CPUs are only a slight improvement.

As CPU core design continues to progress there will continue to be further improvements

in process technology, faster memory interfaces, and wider superscalar cores. However,

about a decade ago, processor architects realized that CPUs were no longer the preferred

solution for certain problems and started with a clean slate for a better solution.

Graphics processing unit (GPU) is a specialized electronic circuit designed to rapidly

manipulate data and alter memory [29,30]. In a GPU 80% of the transistors on the die

are devoted to data processing rather than data caching and flow control as in CPU

because they are designed to execute the same function on each element of data with

high arithmetic intensity. A simple way to understand a GPU is to look at the difference

between a CPU and GPU and to compare how each process tasks. Architecturally, the

CPU is composed of only few cores with lots of cache memory optimized for sequential

serial processing that can handle a few software tasks at a time. In contrast, a GPU

has a massively parallel architecture consisting of thousands of smaller, more efficient

cores designed for handling thousands of tasks simultaneously. The ability of a GPU with

thousands of cores to process thousands of tasks can accelerate some software by 100x

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-19-2048.jpg)

![2.1 Towards an unified graphics computing

architecture

The GPU is a processor with ample computational resources. The modern GPU has

evolved from a fixed function graphics pipeline to a programmable parallel processor with

computing power exceeding that of multicore CPUs. Traditional GPUs structure their

graphics computation in a similar organization called the graphics pipeline. This pipeline is

designed to allow hardware implementations to maintain high computation rates through

parallel execution. The pipeline is divided into several stages. All geometric primitives

pass through every stage. In hardware, each stage is implemented as a separate piece of

hardware on the GPU in what is termed a task-parallel machine organization [31–34].

The input to the pipeline is a list of geometry, expressed as vertices in object

coordinates. The output is an image in a frame buffer. The first stage of the pipeline,

the geometry stage, transforms each vertex from object space into screen space then

assembles the vertices into triangles and traditionally performs lighting calculations on

each vertex. The output of the geometry stage are triangles in screen space. The next

stage, rasterization, determines both the screen positions covered by each triangle and

interpolates per-vertex parameters across the triangle. The result of the rasterization

stage is a fragment for each pixel location covered by a triangle. The third stage, the

fragment stage, computes the color for each fragment using the interpolated values from

the geometry stage. In the final stage, composition, fragments are assembled into an

image of pixels usually by choosing the closest fragment to the camera at each pixel

location [33,34].

Over the years, graphics vendors have transformed the fixed-function pipeline into a

more flexible programmable pipeline [31–34]. This effort has been primarily

concentrated on two stages of the graphics pipeline: vertex processors operate on the

vertices of primitives such as points, lines, and triangles. Typical operations include

transforming coordinates into screen space which are then fed to the setup unit and the

rasterizer, and setting up lighting and texture parameters to be used by the

pixel-fragment processors. Pixel-fragment processors operate on rasterizer output which

fills the interior of primitives along with the interpolated parameters.

Vertex and pixel-fragment processors have evolved at different rates. Vertex

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-21-2048.jpg)

![processors were designed for low-latency, high-precision math operations. Whereas,

pixel-fragment processors were optimized for high-latency, lower-precision texture

filtering. Vertex processors have traditionally supported more complex processing, so

they became programmable first. Each new generation of GPUs have increased the

functionality and generality of these two programmable stages. The two processor types

were functionally converging as the result of a need for greater programming generality.

However, the increased generality also increased the design complexity and cost of

developing two separate processors. Since GPUs typically must process more pixels than

vertices, pixel-fragment processors traditionally outnumber vertex processors by about

three to one. However, typical workloads were not well balanced leading to inefficiency.

These factors influenced the decision to design a unified architecture.

A primary design objective was to execute vertex and pixel-fragment shader

programs on the same unified processor architecture. Unification would enable dynamic

load balancing of varying vertex, pixel-processing workloads and permit the introduction

of new graphics shader stages such as geometry shaders. It also would allow the sharing

of expensive hardware such as the texture units. The generality required of a unified

processor opened the door to a completely new GPU parallel-computing capability.

In November 2006, NVIDIA introduced the Tesla architecture [34, 35] which unifies

the vertex and pixel processors and extends them, enabling high performance parallel

computing applications written in the C language using the Compute Unified Device

Architecture (CUDA) [36–40]. The Tesla architecture is based on a scalable processor

array. Due to its unified-processor design, the physical Tesla architecture does not resemble

the logical order of graphic pipeline stages. The following section gives a brief overview

of the recent GPU microarchitecture based on the new Tesla unified graphics computing

architecture which is utilized here to benchmark this work.

2.2 Architectural overview of the Tesla Kepler GPU

In 2012, the GPU microarchitecture codename, Kepler was introduced which is the

successor to the Fermi microarchitecture. Developed by NVIDIA, it is comprised of 7.1

billion transistors making it the fastest and the most complex microprocessor ever built.

The Kepler microarchitecture uses a similar design to Fermi [41, 42], but with a couple

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-22-2048.jpg)

![Figure 2.2: Full chip block diagram of Kepler microarchitecture based GPU (Source:

NVIDIA)

of key differences [43]. The Kepler architecture focuses on efficiency, programmability

and performance. The Kepler architecture employs a new streaming multiprocessor

architecture called the next-generation streaming multiprocessor (SMX). Each SMX

contains 192 cores which suggests potential for considerably greater performance. The

polymorph engines have been redesigned to deliver twice the performance because all

those cores run at a lower clock speed than the previous Fermi’s core did. The GPU as a

whole uses less power even as it delivers more performance. The reason for Kepler’s

power efficiency is that the whole GPU uses a single Core clock rather than the

double-pump Shader clock [44]. The Kepler implementations include 15 SMX units and

six 64-bit memory controllers. Different products GK110/210 will use different

configurations.

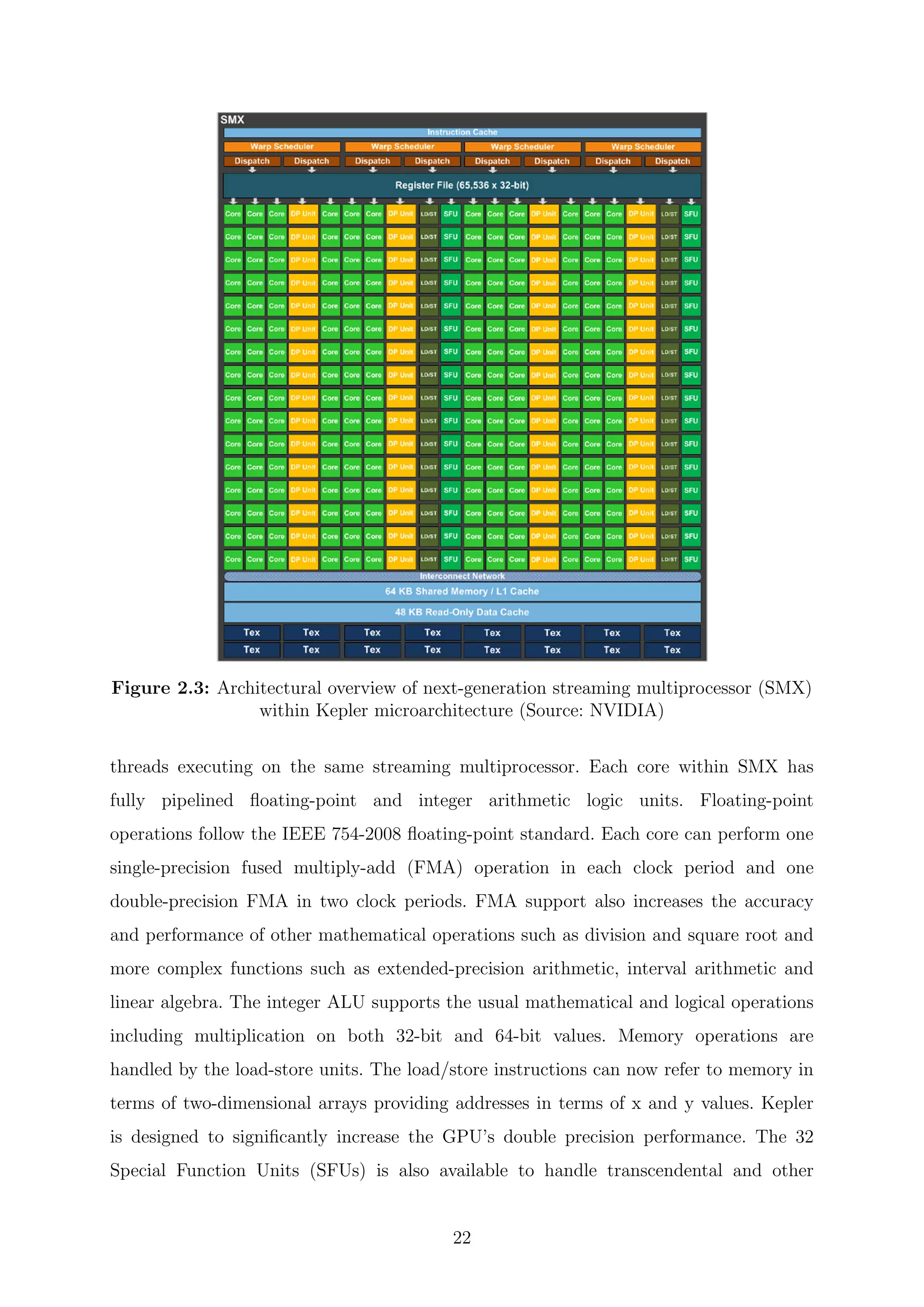

2.2.1 Next-generation streaming multiprocessor

Each SMX unit consists of 192 single-precision cores, 64 double-precision units, 32

special function units, and 32 load/store units, 64 KB of shared memory, and 48 KB of

read-only data cache. The shared memory and the data cache are accessible to all

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-23-2048.jpg)

![special operations such as sin, cos, exp (exponential) and rcp (reciprocal) [43,45–47].

2.2.2 Instruction scheduler

The SMX schedules threads in groups of 32 parallel threads called warps. Each SMX

features four warp schedulers and eight instruction dispatch units allowing four warps to

be issued and executed concurrently. Kepler’s quad warp scheduler selects four warps and

two independent instructions per warp can be dispatched each cycle. Kepler allows double

precision instructions to be paired with other instructions [45,48].

Figure 2.4: Warp scheduler within next-generation streaming multiprocessors (Source:

NVIDIA)

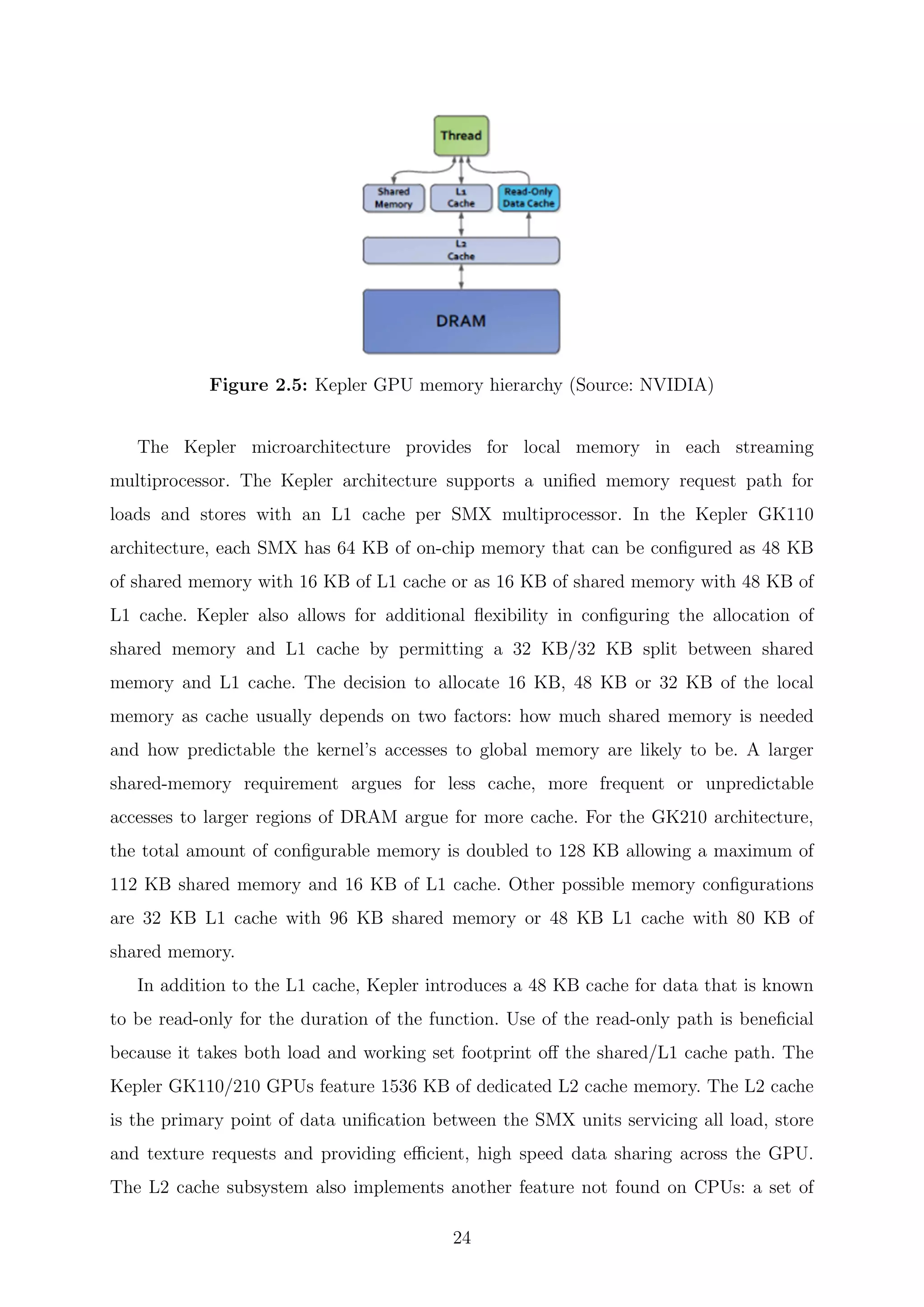

2.2.3 Memory model

The number of registers that can be accessed by a thread has been quadrupled in Kepler

allowing each thread access to up to 255 registers. Codes that exhibit high register pressure

or spilling behavior in previous microarchitecture may see substantial speedups as a result

of the increased available per-thread register count. Kepler also implements a new shuffle

instruction which allows threads within a warp to share data. Previously, sharing data

between threads within a warp required separate store and load operations to pass the

data through shared memory. With the shuffle instruction, threads within a warp can

read values from other threads in the warp in just about any imaginable permutation.

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-25-2048.jpg)

![memory read-modify-write operations that are atomic and thus ideal for managing access

to data that must be shared across thread blocks or even kernels. L1 and L2 caches help in

improving the random memory access performance while the texture cache enables faster

texture filtering. The programs also have access to a dedicated shared memory which is

a small software-managed data cache attached to each multiprocessor shared among the

cores. This is a low-latency, high-bandwidth, indexable memory which runs essentially at

register speeds. Kepler’s register files, shared memories, L1 cache, L2 cache and DRAM

memory are protected by a single-error correct double-error detect ECC code.

2.2.4 Advance features

In Kepler, Hyper-Q enables multiple CPU cores to launch work on a single GPU

simultaneously; thereby, expanding Kepler GPU hardware work queues from 1 to

32 [45, 46]. The significance of this being that having a single work queue meant that

previous GPU could be under occupied at times if there wasn’t enough work in that

queue to fill every streaming multiprocessor. By having 32 work queues, Kepler can in

many scenarios achieve higher utilization by being able to put different task streams on

what would otherwise be an idle SMX.

When working with a large amount of data, increasing the data throughput and

reducing latency is vital to increasing compute performance. Kepler GK110/210

supports the RDMA feature in NVIDIA GPUDirect which is designed to improve

performance by allowing direct access to GPU memory by third-party devices [45, 46].

GPUDirect provides direct memory access (DMA) between NIC and GPU without the

need for CPU side data buffering. GPUDirect enables much higher aggregate bandwidth

for GPU-to-GPU communication within a server and across servers with the

Peer-to-Peer and RDMA features.

Kepler has a possibility of dynamic parallelism which allows the GPU to generate

new work for itself, synchronize on results and control the scheduling of that work via

dedicated, accelerated hardware paths all without involving the CPU [45,46]. In previous

GPUs, all work was launched from the host CPU, run to completion, and return a result

back to the CPU. The result would then be used as part of the final solution or would

be analyzed by the CPU which would then send additional requests back to the GPU for

additional processing. In Kepler, any kernel can launch another kernel and can create the

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-27-2048.jpg)

![Figure 2.6: Direct Peer-to-Peer data transfer between two GPUs using GPUDirect

(Source: NVIDIA)

necessary streams, events and manage the dependencies needed to process additional work

without the need for host CPU interaction. This architectural innovation makes it easier

for developers to create and optimize recursive and data-dependent execution patterns

and allows more of a program to be run directly on GPU.

2.3 CUDA programming model

In November 2006, NVIDIA introduced CUDA, a general purpose parallel computing

architecture with a new parallel programming model and instruction set architecture.

CUDA comes with a software environment that allows developers to use C as a high-

level programming language [37, 49]. At its core are three key abstractions; a hierarchy

of thread groups, shared memories and barrier synchronization that are simply exposed

to the programmer as a minimal set of language extensions. These abstractions provide

fine-grained data parallelism and thread parallelism nested within coarse-grained data

parallelism and task parallelism. They guide the programmer to partition the problem

into coarse sub-problems that can be solved independently in parallel by blocks of threads

and each sub-problem into finer pieces that can be solved cooperatively in parallel by all

threads within the block [38–40].

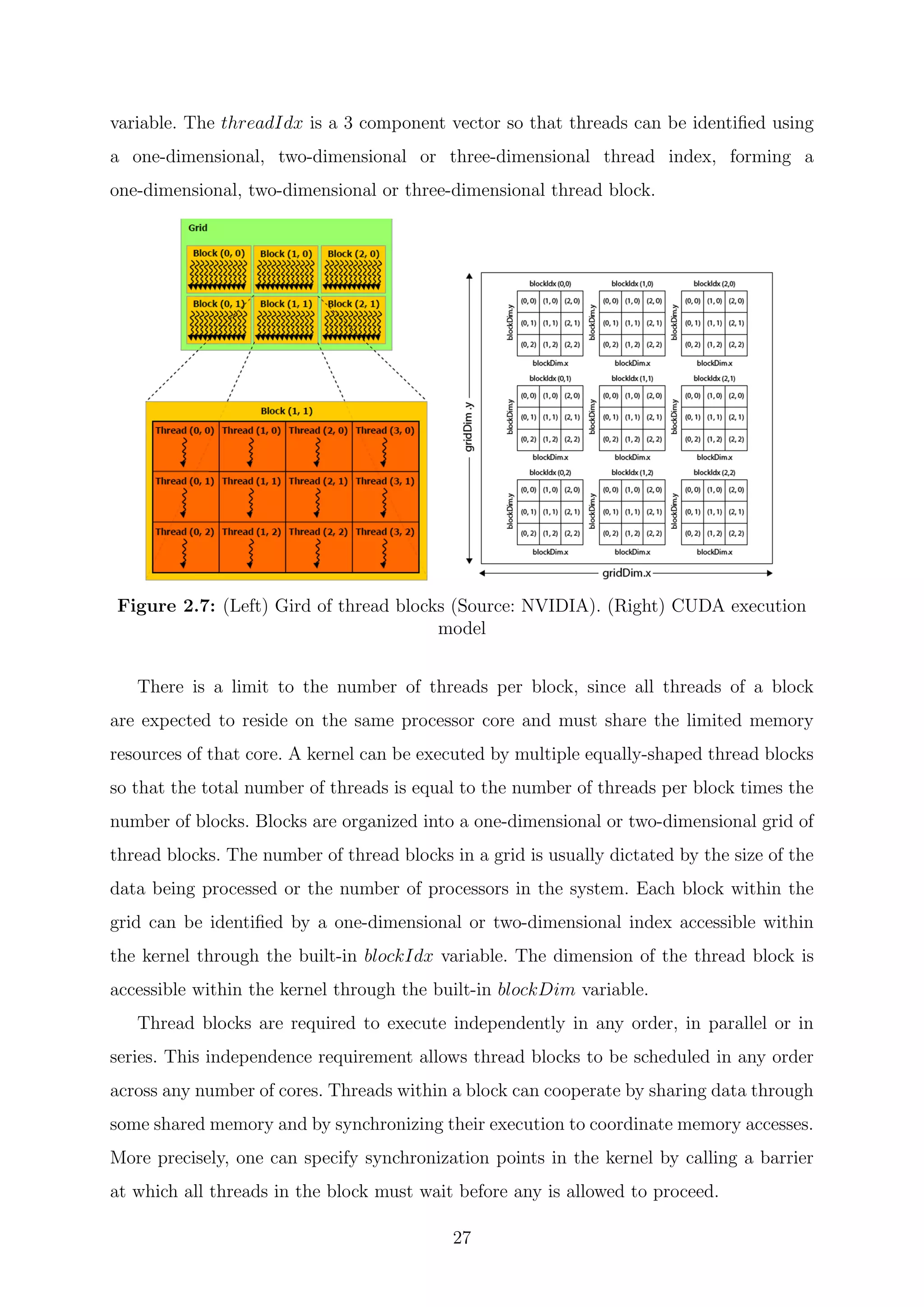

CUDA extends C by allowing the programmer to define C functions called

kernels [50]. Kernel is the parallel portion of the application that will execute on the

GPU. Kernels are executed N times in parallel by N different CUDA threads as opposed

to only once like regular C functions. Each thread that executes the kernel is given a

unique thread ID that is accessible within the kernel through the built-in threadIdx

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-28-2048.jpg)

![CUDA threads may access data from multiple memory spaces during their execution.

Each thread has private local memory. Each thread block has shared memory visible to all

threads of the block and with the same lifetime as the block. All threads have access to the

same global memory. There are also two additional read-only memory spaces accessible

by all threads: the constant and texture memory spaces. The global, constant and texture

memory spaces are persistent across kernel launches by the same application.

2.4 General-purpose computing on graphics

processing units

Traditionally, powerful GPUs have been useful mostly to gamers looking for realistic

experiences along with engineers and creatives needing 3D modeling functionality.

General-purpose computing on GPUs only became practical and popular after 2001 with

the advent of both programmable shaders and floating point support on graphics

processors. In particular, problems involving matrices and/or vectors especially two,

three or four-dimensional vectors were easy to translate to a GPU which acts with

native speed and support on those types. The scientific computing community’s

experiments with the new hardware started with a matrix multiplication routine. These

early efforts to use GPUs as general-purpose processors required reformulating

computational problems in terms of graphics primitives as supported by the two major

APIs for graphics processors, OpenGL and DirectX [33]. This cumbersome translation

was obviated by the advent of general-purpose programming languages and APIs such

as Sh/RapidMind, Brook and Accelerator [31,51,52].

These were followed by NVIDIA’s CUDA, which allowed programmers to ignore the

underlying graphical concepts in favor of more common high-performance computing

concepts [32, 53]. Newer, hardware vendor-independent offerings include Microsoft’s

DirectCompute and Apple/Khronos Group’s OpenCL [53]. This means modern GPGPU

pipelines can act on any big data operation and leverage the speed of a GPU without

requiring full and explicit conversion of the data to a graphical form [50].

GPU flexibility has increased over the last decade thanks to their massive multi-core

parallelization, delivering high throughput capabilities even on double-precision

arithmetic, to their increased on-board memory and the efforts made by vendors in

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-30-2048.jpg)

![facilitating programmability. GPU accelerated computing has revolutionized the HPC

industry. Researchers have quickly realized that many real world problems map very

well to the pipelined single instruction multiple data (SIMD) hardware in the GPU’s

streaming processors. There are many computational applications across a wide range of

fields already optimized for GPUs. Some examples are: Molecular dynamics [54–57],

Quantum chemistry [58–62], Materials science [63, 64], Bioinformatics [65–69],

Physics [70–74], Numerical analytics [75–77], Fluid dynamics [78–80], Medical

imaging [81–83], Finance [84,85].

While GPU has many benefits such as more computing power, larger memory

bandwidth and low power consumption, there are some constraints to fully utilize its

processing power. Developing codes for GPU takes more time and need more

sophisticated work, gaining relevant speedup requires that algorithms are coded to

reflect the GPU architecture, and programming for the GPU differs significantly from

traditional CPUs. In particular, incorporating GPU acceleration into pre-existing codes

is more difficult than just moving from one CPU family to another. A GPU-savvy

programmers need to dive into the code and make significant changes to critical

components. Also, GPU code runs in parallel so data partition and synchronization

technique are needed which also enforces access levels for different categories of memory.

The low bandwidth PCI-E bus that physically connects between the GPU and the rest

of the system is one of the main performance limiting factor. The performance of GPU

goes down an order of magnitude as transferring anything over PCI-E lowers the speeds

twentyfold compared to the onboard memory. These constraints make performance

optimization more difficult. Also, GPU’s debugging environment is not as powerful as

general CPU.

2.5 Summary

GPU is the most powerful computing engine available to computational scientists and is

being utilized in a wide range of scientific computing applications. What make the GPU

so powerful is its thousands of identical cores that run at lower clock rate than CPU but

optimized for recursive SIMD type operation on a big data set, along with its high memory

bandwidth and ease of programmability using a high level language. However, there are

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-31-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 3

Introduction to Eigensolvers

The theory and computation of eigenvalue problems are among the most successful and

widely used tools of applied mathematics and scientific computing. Eigenvalue problems

find its application in a variety of scientific and engineering applications including

acoustics, control theory, earthquake engineering, graph theory, Markov chains, pattern

recognition, quantum mechanics, stability analysis, quantum physics, material sciences

and many other areas. The increasing number of applications and the ever-growing scale

of problems have motivated fundamental progress in the numerical solution of eigenvalue

problems.

Eigenvalues are often introduced in the context of linear algebra or matrix theory.

However, historically, they arose in the study of quadratic forms and differential

equations. In the 18th

century, Euler studied the rotational motion of a rigid body and

discovered the importance of the principal axes. Lagrange realized that the principal

axes are the eigenvectors of the inertia matrix [86]. In the early 19th

century, Cauchy

saw how their work could be used to classify the quadric surfaces and generalized it to

arbitrary dimensions. At the start of the 20th

century, Hilbert studied the eigenvalues of

integral operators by viewing the operators as infinite matrices [87]. He was the first to

use the word “eigen.” The first numerical algorithm for computing eigenvalues and

eigenvectors appeared in 1929 when Von Mises published the power method [88].

An eigenvector of an N×N square matrix A is a non-zero vector v that, when multiplied

with A, yields a scalar (λ) multiple of itself.

31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-33-2048.jpg)

![Av = λv (3.1)

This equation is referred to as the standard eigenvalue problem. Here, λ is an eigenvalue

of A, v is the corresponding right eigenvector and (λ, v) is called an eigenpair. The set of

all eigenvectors of a matrix, each paired with its corresponding eigenvalue is called the

eigensystem of that matrix [89]. The full set of eigenvalues of A is called the spectrum and

is denoted by λ(A) = λ1, λ2, ..., λn. Any multiple of an eigenvector is also an eigenvector

with the same eigenvalue. An eigenspace of a matrix A is the set of all eigenvectors with

the same eigenvalue together with the zero vector. An eigenbasis for A is any basis for

the set of all vectors that consists of linearly independent eigenvectors of A.

In solving an eigenvalue problem, there are a number of properties that need be

considered like the type of matrix (real or complex), structure of the matrix (band,

sparse, structured sparseness, toeplitz), special properties of the matrix (symmetric,

hermitian, skew symmetric, unitary) and type of eigenvalues required (largest, smallest,

inner, sums of intermediate eigenvalues). These greatly affect the choice of algorithm.

There are a variety of more complicated eigenproblems. For instance, Ax = λBx and

more generalized eigenproblems like Ax + λBx + λ2

Cx = 0, higher order polynomial

problems, and nonlinear eigenproblems. All these problems are considerably more

complicated than the standard eigenproblem depending on the operators involved.

In numerical mathematics, several different techniques needed to calculate the

eigenpairs have been developed. These techniques can be divided into two main groups:

“direct methods” and “iterative methods.” First, the algorithms for medium sized

problems that calculate one up to all eigenvalues. Second, the methods for huge

eigenvalue equations that calculate only a few eigenpairs projecting the huge problem

onto a much smaller search space which is build up within the algorithm. The projected

system is small enough to be solved by techniques of the former group.

3.1 Direct methods

In this section, lets briefly discuss various direct methods for the computation of

eigenvalues of matrices that are small and can be stored in the computer memory as full

matrices. These direct methods are sometimes called transformation methods and are

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-34-2048.jpg)

![built up around similarity transformations. They transforms the matrix to a simpler

form and finds all the eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

3.1.1 QR algorithm

This algorithm finds all the eigenvalues and optionally all the eigenvectors. The basic

idea is to perform QR decomposition [90–92]. The QR algorithm consists of two separate

stages. First, by means of a similarity transformation, the original matrix is transformed

in a finite number of steps to Hessenberg form or in the Hermitian/symmetric case to real

tridiagonal form. This first stage of the algorithm prepares it for the second stage which is

the actual QR iterations that are applied to the Hessenberg or tridiagonal matrix [93]. It

takes O(n2

) floating point operations for finding all the eigenvalues of a tridiagonal matrix.

Since reducing a dense matrix to tridiagonal form costs 4

3

n3

floating point operations,

O(n2

) is negligible for large enough n. For finding all the eigenvectors as well, QR iteration

takes a little over 6n3

floating point operations on average.

3.1.2 Divide-and-conquer method

An eigenvalue problem is divided into two problems of roughly half the size, each of

these are solved recursively and the eigenvalues of the original problem are computed

from the results of these smaller problems. This algorithm was originally proposed by

Cuppen [94]. However, it took ten more years until a stable variant was found by Gu

and Eisenstat [95,96]. The advantage of divide-and-conquer comes when eigenvectors are

needed as well. If this is the case, reduction to tridiagonal form takes 8

3

n3

, but the second

part of the algorithm takes O(n3

) as well. For the QR algorithm with a reasonable target

precision, this is ≈ 6n3

, whereas for divide-and-conquer it is ≈ 4

3

n3

. The reason for this

improvement is that in divide-and-conquer the O(n3

) part of the algorithm is separate

from the iteration, whereas in QR, this must occur in every iterative step. Adding the

8

3

n3

flops for the reduction, the total improvement is from ≈ 9n3

to ≈ 4n3

flops. The

divide-and-conquer approach is now the fastest algorithm for computing all eigenvalues

and eigenvectors of a symmetric matrix of order larger than 25, this also holds true for

non-parallel computers. If the subblocks are of order greater than 25, then they are further

reduced else, the QR algorithm is used for computing the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of

the subblock [97].

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-35-2048.jpg)

![3.1.3 Bisection method and inverse iteration

Bisection may be used to find just a subset of the eigenvalues, like those in an interval [a, b].

It needs only O(nk) floating point operations, where k is the number of eigenvalues desired.

Thus the bisection method could be much faster than the QR method when k n. It

can be highly accurate, but may be adjusted to run faster if lower accuracy is acceptable

[98,99]. Inverse iteration can then be used to find the corresponding eigenvectors. In the

best case, when the eigenvalues are well separated, inverse iteration also costs only O(nk)

floating point operations. This is much less than either QR or divide-and-conquer, even

when all eigenvalues and eigenvectors are desired (k = n). On the other hand, when many

eigenvalues are clustered close together, Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization will be needed

to make sure that one does not get several identical eigenvectors. This will add O(nk2

)

floating point operations to the operation count in the worst case.

3.1.4 Jacobi method

Jacobi method is mostly used for solving Hermitian eigenvalue problems. This method

constructs an orthogonal transformation to diagonal form, A = XΛX∗

by applying a

sequence of elementary orthogonal rotations, each time reducing the sum of squares of

the nondiagonal elements of the matrix, until it is of diagonal form to working

accuracy [100]. The Jacobi algorithm has been very popular since its implementation is

very simple and gives eigenvectors that are orthogonal to working accuracy. However, it

cannot compete with the QR method in terms of operation counts. Jacobi needs 2sn3

multiplications for s sweeps, which is more than the 4

3

n3

needed for tridiagonal

reduction. There is one important advantage to the Jacobi algorithm. It can deliver

eigenvalue approximations with a small error in the relative sense, in contrast to

algorithms based on tridiagonalization, which only guarantee that the error is bounded

relative to the norm of the matrix [101,102].

3.2 Iterative methods

Theoretically, the numerical algorithms mentioned above are applicable for arbitrary

dimensions but practically they are limited by memory restrictions and computational

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-36-2048.jpg)

![time. The effort of the QR algorithm is in O(n3

) and cannot be handled for large N on

current computers. In this section, numerical methods are introduced that calculate a

few eigenvalues with less computational cost. The well-known iterative methods for

solving eigenvalue problems are the power method (the inverse iteration), the Krylov

subspace methods, the Jacobi-Davidson algorithm and FEAST method. Traditionally, if

the extreme eigenvalues are not well separated or the eigenvalues sought are in the

interior of the spectrum, a shift-and-invert transformation has to be used in combination

with these eigenvalue problem solvers.

3.2.1 Power iteration method

The power iteration is a very simple algorithm. It does not compute a matrix

decomposition, the basic idea is to multiply the matrix A repeatedly by a well chosen

starting vector, so that the component of that vector in the direction of the eigenvector

with largest eigenvalue in absolute value is magnified relative to the other

components [88]. The speed of convergence of the power iteration depends on the ratio

of the second largest eigenvalue to the largest eigenvalue.

It is interesting that the most effective variant is the inverse power method with shift

which can find interior as well as exterior eigenvalues [103]. The idea of this method is to

apply the power method on A−1

or on the inverse of the shifted matrix (A − µ0I)−1

. The

eigenvalues of A−1

are the inverse eigenvalues of A. Thus, the inverse power method finds

the eigenvalue closest to zero. The smallest eigenvalue of the shifted matrix (A − µ0I) is

the eigenvalue of A closest to µ0. Therefore, this method can find any simple eigenvalue

when an appropriate guess µ0 is available.

3.2.2 Rayleigh quotient iteration method (RQI)

RQI is an eigenvalue algorithm which extends the idea of the inverse iteration by using the

Rayleigh quotient to obtain increasingly accurate eigenvalue estimates [104]. Starting with

a normalized putative eigenvector a sequence of normalized approximate eigenvectors are

generated with their associated Rayleigh quotients. The RQI algorithm converges cubically

for Hermitian or symmetric matrices, given an initial vector that is sufficiently close to an

eigenvector of the matrix that is being analyzed. If the matrix is non-Hermitian then it is

still possible to get cubical convergence by using a two-sided version of the algorithm. The

35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-37-2048.jpg)

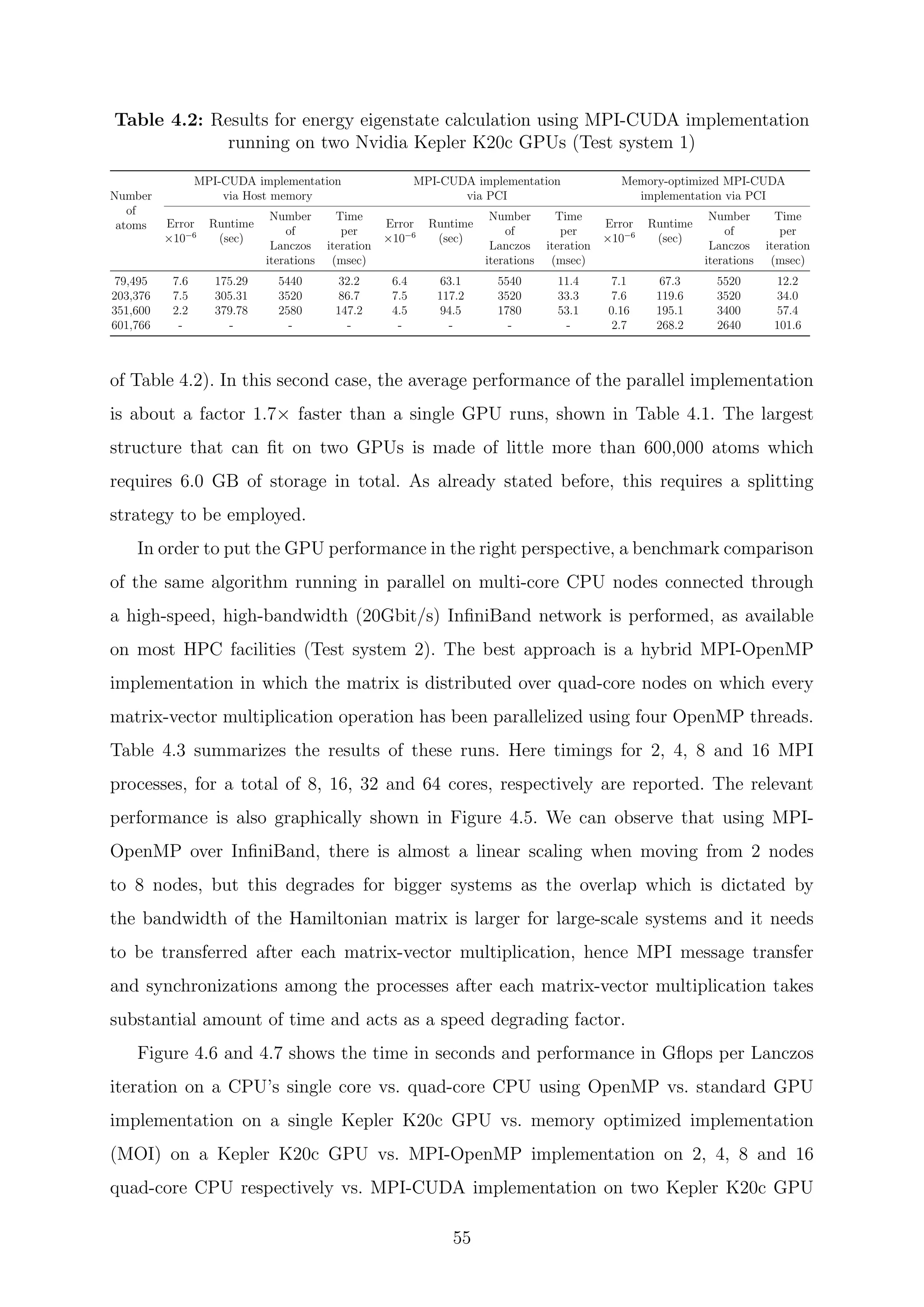

![drawbacks of the RQI method is that it may converge to an eigenvalue which is not the

closest to the desired one and the algorithm has a high computation cost since it requires

a factorization at every iteration.

3.2.3 Arnoldi method

The Arnoldi method was first introduced as a direct algorithm for reducing a general

matrix into upper Hessenberg form [105]. It was later discovered that this algorithm

leads to a good iterative technique for approximating eigenvalues of large sparse matrices.

Arnoldi method belongs to a class of linear algebra algorithms based on the idea of Krylov

subspaces that give a partial result after a relatively small number of iterations. It is an

orthogonal projection method onto a Krylov subspace. The procedure can be essentially

viewed as a modified Gram-Schmidt process for building an orthogonal basis of the Krylov

subspace Km

(A, v). The cost of orthogonalization increases as the method proceeds. A

convergence analysis of eigenvector approximation using the Arnoldi method can be found

in [106,107].

As CPU time and memory needed to manage the Krylov subspace increase with its

dimension, a subspace restarting strategy is necessary. Roughly speaking, the restarting

strategy builds a new subspace of smaller dimension by extracting the desired

approximate eigenvectors from the current subspace of a larger dimension. An elegant

implicit restarting strategy based on the shifted-QR algorithm was proposed by

Sorensen [108]. This method generates a new Krylov subspace of smaller dimension

without using matrix-vector products involving A. The resulting algorithm is called the

implicitly restarted Arnoldi (IRA) method.

3.2.4 Lanczos method

The Lanczos algorithm can be viewed as a simplified Arnoldi’s algorithm in that it

applies to Hermitian matrices. It’s algorithm is an effective iterative method to find

eigenvalues and eigenvectors of large sparse matrices by first building an orthonormal

basis and then forming approximate solutions using Rayleigh projection. It reduces a

large, complicated eigenvalue problem into a simpler one [109, 110] explicitly taking

advantage of the symmetry of the matrix. However, the Lanczos method diverges when

implemented on a finite precision architecture since the Lanczos vectors inevitably lose

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-38-2048.jpg)

![their mutual orthogonality [110, 111]. Hence, it needs a full reorthogonalization of each

newly computed vector against all preceding Lanczos vectors. This not only greatly

increases the number of computations required, but also requires that all the vectors be

stored. For large problems, it will be very expensive to take more than a few steps using

full reorthogonalization. Nevertheless, linear independence will surely be lost without

some sort of corrective procedure.

Selective orthogonalization interpolates between full reorthogonalization and simple

Lanczos to obtain the best of both worlds. Robust linear independence is maintained

among the vectors at a cost which is close to that of simple Lanczos [112,113]. Another

way to maintain orthogonality is to limit the size of the basis set and use a restarting

scheme by replacing the starting vector with an improved starting vector and computing

a new Lanczos factorization with the new vector.

3.2.5 Locally optimal block preconditioned conjugate gradient

method (LOBPCG)

LOBPCG is based on a local optimization of a three-term recurrence. It is designed to

find the smallest or the largest eigenvalues and corresponding eigenvectors of a symmetric

and positive definite eigenvalue problems [114]. Similar to other conjugate gradient based

methods, this is accomplished by the iterative minimization of the Rayleigh quotient, while

taking the gradient as the search direction in every iteration step. Which results in finding

the smallest eigenstates of the original problem. In the LOBPCG method the minimization

at each step is done locally, in the subspace of the current approximation, the previous

approximation, and the preconditioned residual. The subspace minimization is done by

the Rayleigh-Ritz method. Iterating several approximate eigenvectors, simultaneously, in a

block in a similar locally optimal fashion, results in the full block version of the LOBPCG.

3.2.6 Davidson method

Davidson came up with an idea of expanding the subspace in such a way that certain

eigenpairs would be favored. Bearing in mind the fact that if certain true eivenvector

lies in the subspace of current iteration, the eigen problem in the subspace would give

the exact corresponding eigenpair. Thus to achieve fast convergence, a better way to

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-39-2048.jpg)

![expand the subspace is to choose the new expansion vector to be the component of the

error vector which is orthogonal to the subspace [115,116]. If this orthogonal component

could be solved exactly and added to the subspace, then convergence is guaranteed to be

achieved in the next iteration in exact arithmetic. It has been reported that this method

can be quite successful in finding dominant eigenvalues of (strongly) diagonally dominant

matrices. Davidson [117] suggests that his algorithm (more precisely, the Davidson-Liu

variant) may be interpreted as a Newton-Raphson scheme and this has been used as an

argument to explain its fast convergence.

3.2.7 Jacobi-Davidson method

The Jacobi-Davidson method is a popular technique to compute a few eigenpairs of large

sparse matrices. It is motivated by the fact that standard eigensolvers often require an

expensive factorization of the matrix to compute interior eigenvalues. Such a factorization

is unfeasible for large matrices in large-scale simulations. In the Jacobi-Davidson method,

one still needs to solve inner linear systems, but a factorization is avoided because the

method is designed so as to favor the efficient use of iterative solution techniques based on

preconditioning [118]. Jacobi-Davidson method belongs to the class of subspace methods

which means that approximate eigenvectors are sought in a subspace. Each iteration of

this method has two important phases: the subspace extraction in which an approximate

eigenpair is sought with the approximate vector in the search space and the subspace

expansion in which the search space is enlarged by adding a new basis vector to it trying

to lead to a better approximate eigenpairs in the next extraction phase [119,120].

3.2.8 Contour integral spectral slicing

The contour integral spectral slicing method is based on the contour integral method

proposed by Sakurai-Sugiura [121] for finding certain eigenvalues of a generalized

eigenvalue problem that lie in a given domain of the complex plane. The method

projects the matrix pencil onto a subspace associated with the eigenvalues that are

located in the domain. The approach is based on the root finding method for an analytic

function. This method finds all of the zeros that lie in a circle using numerical

integration. The algorithm requires a region that includes several eigenvalues and an

estimate of the number of eigenvalues or clusters in the region. The major advantage of

38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-40-2048.jpg)

![this method is that iterative process for constructing subspace is not required. At each

contour point the projected matrix pencil with eigenvalues of interest are derived by

solution of linear systems. A Rayleigh-Ritz type variant of the method has been also

developed to improve numerical stability [122].

3.2.9 FEAST method

Lately, the FEAST algorithm which takes its inspiration from the density-matrix

representation and contour integration technique in quantum mechanics has been

developed [123]. Unlike the Lanczos and Jacobi-Davidson method, the aim of the

FEAST algorithm is to actually compute the eigenvectors instead of approximating

them. The algorithm deviates fundamentally from the traditional Krylov subspace

iteration based techniques. This algorithm is free from any orthogonalization procedures

and its main computational tasks consist of solving the inner independent linear systems

with multiple right-hand sides. The FEAST algorithm finds all the eigenpair in a given

search interval. It requires that one provides an estimate for the number of eigenpair

within the search interval which often is not possible to obtain beforehand [124].

3.3 Survey of available software packages for

eigenproblems

The history of reliable high quality software for numerical linear algebra started in 1971

with the book titled the “Handbook for Automatic Computation” [125]. This book

described state-of-the-art algorithms for the solution of linear systems and

eigenproblems. During the same decade, few research groups started the development of

two influential software packages: LINPACK and EISPACK. LINPACK covered the

numerical solution of linear systems. EISPACK concentrated on eigenvalue problems.

These packages can also be viewed as prototypes for eigenvalue routines in the bigger

software packages NAG and IMSL and in the widely available software package

MATLAB. EISPACK was replaced in 1995 by LAPACK.

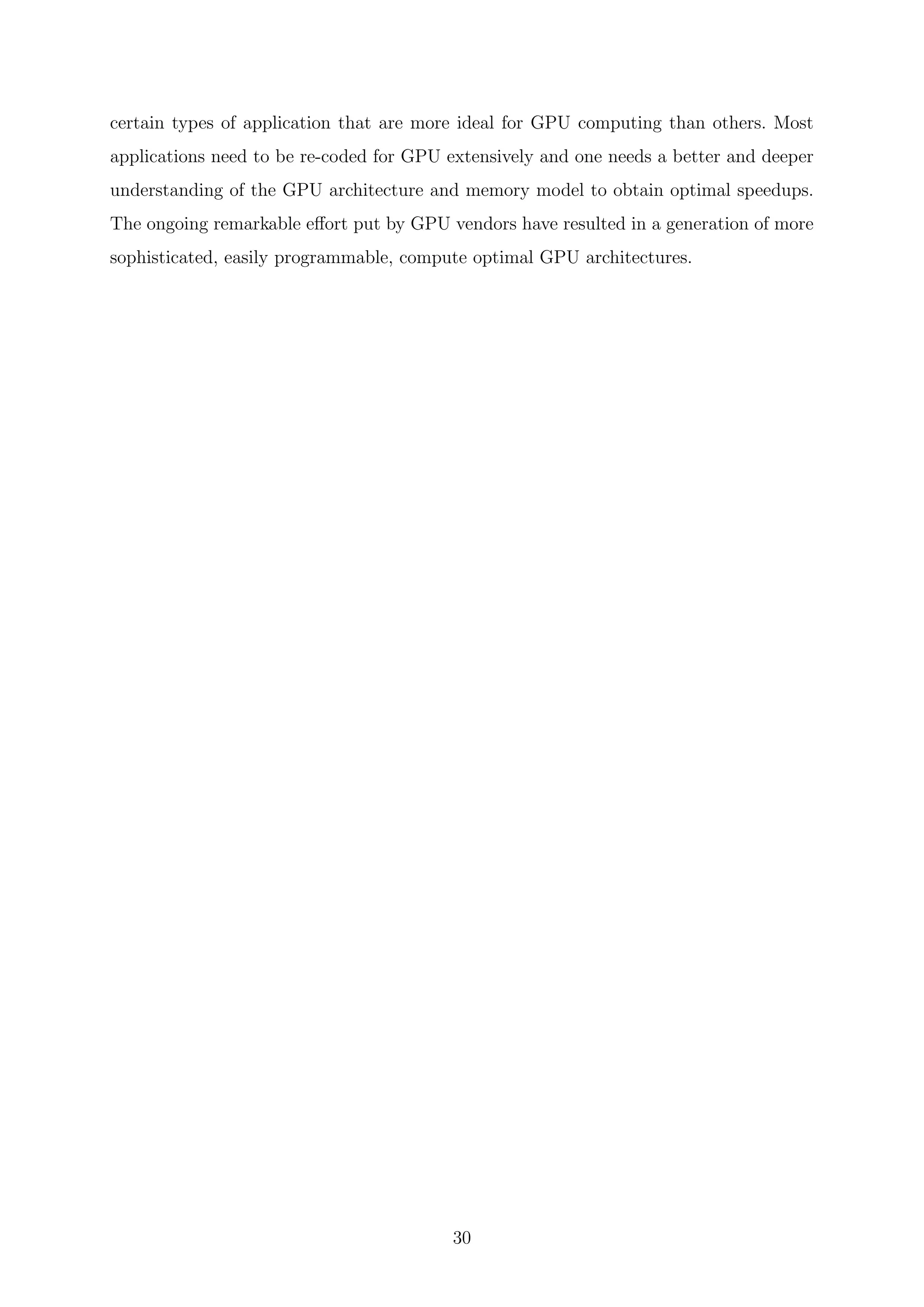

In Table 3.1, we can noticed that there are numerous commercial and open source free

packages available that support single and double precision, real or complex arithmetic

eigensolvers and even distributed computing via MPI or other technologies. Yet, there

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-41-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 4

Design of GPU based eigensolver for

atomistic simulation

There are two important aspects that must be considered while employing a numerical

method. The first one is the correct implementation of the physical governing equations

and the accuracy of the mathematical algorithms. The second one is directly related to

the nature of the hardware needed to execute the model. Each kind of platform used to

perform numerical simulations presents its own advantages and limitations. Parallelization

methods and optimization techniques are essential to perform simulations at a reasonable

execution time.

Iterative methods based on the Krylov subspace which were introduced in Chapter 3

are usually employed to compute few eigenstates of large sparse matrices. Among these

methods is the original Lanczos algorithm, Arnoldi [110], Krylov-Schur or

Jacobi-Davidson [126]. As already seen, some of the main standard libraries that include

iterative eigensolver routines are ARPACK (ARnoldi PACKage) [127], PRIMME

(PReconditioned Iterative MultiMethod Eigensolver) a library based on

Jacobi-Davidson algorithm [128], IETL (Iterative Eigensolver Template Library)

providing a generic template interface to performance solvers [116] and SLEPc, a

scalable library based on the linear algebra package PETSc [129]. All these libraries

support single and double precisions, real or complex arithmetic and even distributed

computations via MPI as well.

Most eigenvalue solvers have concentrated on computational techniques that

42](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-44-2048.jpg)

![accelerate separate components, in particular the matrix-vector multiplication [130] or a

new efficient sparse matrix storage formats [131]. However, there exists a limited amount

of work realized for taking advantage of modern day processor architectural

improvements for high performance computing in atomistic simulation which is

facilitated by their enhanced programmability and motivated by their attractive price to

performance ratio and incredible growth in speed [116,127,128].

This work has been motivated by the lack of specialized eigensolvers for large-scale

computations on GPUs. I concentrate on addressing some basic problems that hinder

the development of efficient eigensolver on GPUs: First, the choice of the algorithm

itself. Then its demonstrate how to overcome the problem of compute versus

communication gap that exists in GPUs and have also established ways to resolve the

computational and memory related bottlenecks. Finally, a multi-GPU implementation

that scales with GPUs is presented. Resulting in an eigensolver that accelerates

efficiently large-scale TB calculations. In the following sections, I start with the custom

implementation of the Lanczos algorithm with a simple restart that is optimized for

GPUs as it has been identified as a more fitted method for computing few eigenpairs on

a GPU framework that can cope with memory limitations of current GPUs and slow

GPU-CPU communication. I, also, discuss the enhancements and strategies developed

for optimal eigenslover implementations utilizing GPU and other HPC based distributed

technologies and present benchmark calculations performed on a GaN/AlGaN wurtzite

quantum dot similar to the one shown in Figure 4.1. I further the discussion in Chapter

5 by comparing our fine-tuned Lanczos implementation with GPU based

Jacobi-Davidson and FEAST method implementations.

Figure 4.1: Conical wurtzite GaN/AlGaN quantum dot with 30% Al. Atomistic

description: In yellow Aluminium, in red Gallium.

43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-45-2048.jpg)

![4.1 Lanczos method

We are interested in finding inner eigenvalues of the energy spectrum, near the energy

gap of the large GaN/AlGaN quantum dots nanostructure as shown in 4.1. Such

systems have important applications in modern nitride-based light emitting diodes

(LEDs) [9, 19]. However, the Lanczos algorithm converges fast to the extreme

eigenvalues. As stated in Chapter 3, different spectral transformations are used for the

purpose, like spectrum folding or shift-and-invert [110]. In this, implementation

spectrum folding is applied in order to avoid the computation of the matrix inverse that

might pose additional convergence problems. So, in general, the lowest eigenpairs of the

operator A = (H − sI)2

is computed, where s is the chosen spectrum shift [132]. The

implemented algorithm is a variant of that described in reference [133].

Algorithm. The Lanczos method

Assume H is a Hermitian matrix, q1 is a random vector with |q1| = 1

q0 = 0, β1 = 0

for i = 1 to m :

ui = (H − sI)qi

αi = ui · ui

qi+1 = (H − sI)ui − αiqi − βiqi−1

βi+1 = ||ui||2

After each iteration, we get αi and βi, the coefficients used to construct the tridiagonal

matrix,

T =

α1 β2 0

β2 α2 β3

β3 α3

...

...

... βm−1

βm−1 αm−1 βm

0 βm αm

Due to finite precision arithmetic, new q vectors slowly become less orthogonal to the

initial vectors [106]. Reorthogonalizing the current q vector against all previous qi takes

44](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-46-2048.jpg)

![a lot of resources and it is not done in our implementation. Other versions of the

Lanczos algorithm, performs a partial reorthogonalization keeping the subspace rather

small. Experience shows that the convergence rate increases when the subspace is

considerably enlarged at the expense of accurate orthogonality. In this implementation,

the Lanczos iterations are performed until orthogonality with respect to the initial

vector, q1, is preserved to an error of 10−5

. In this way, the typical size of the tridiagonal

matrix, T , becomes of the order of 1000, which can be diagonalized using standard

LAPACK routines, obtaining the eigenvalues, λ

(m)

i and corresponding eigenvectors,

w

(m)

i .

It can be proved that the eigenvalues of T are approximate eigenvalues of A. Here,

only the eigenvalues with lowest |λi| are considered, corresponding to the eigenvalue λi =

|λi|+s of H closer to s. The projected eigenvector, vi, can be calculated as vi = Qmw

(m)

i ,

where Qm is the transformation matrix whose column vectors are q1, q2, · · · , qm. The qi

vectors are recomputed on the fly by running the Lanczos iteration a second time. This

might seem a waste of time at first, but reducing the subspace size in order to store the qi

vectors in memory does not improve overall speed. Once the approximate eigenvector, vi,

has been computed, the algorithm is tested for convergence by considering the residual

norm || ¯vi|H|¯vi / ¯vi|¯vi − λi|| < tol.

One can notice from the algorithm that each iteration requires two sparse matrix-

vector (spMV) multiplications and four vector operations, which implies that, if Rmax is

the maximum number of non-zero elements in any one row of the sparse matrix H, then

the complexity of the spMV product operation is O(Rmax · N) [134]. The complexity per

iteration of the Lanczos algorithm is O(2(Rmax · N) + N) where the dominant operation

is given by the matrix-vector multiplication. Observe that the matrix remains unchanged

along this loop.

4.2 Implementation and optimization strategies for

parallel eigensolvers

Two different hardware technologies have been employed: CPUs and GPUs. Current

CPUs have multiple processing cores, making possible the distribution of workload

among the different cores using its multi-core shared-memory architecture. In addition,

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-47-2048.jpg)

![CPUs also present SIMD which allows performing an operation on multiple data

simultaneously. Open Multi-Processing (OpenMP) may be used for explicit direct

multithreaded, shared memory parallelism thus providing a portable, scalable model for

developers of shared memory parallel applications. OpenMP programs accomplish

parallelism exclusively through the use of threads [135].

As detailed in Chapter 2, the GPU architecture allows for the execution of threads on

a larger number of processing elements. Although these processing elements are typically

much slower than those of a CPU, having a large number of threads may make it possible

to surpass the performance of current multi-core CPUs [136]. Another characteristic of

parallel programming with GPUs is the ability to start a large number of threads with

little overhead [39]. This is unlike traditional CPU threads, where each individual thread

is treated as an entity independent of others, requiring separate resources such as stack

memory, and whose creation and management are not cheap [39]. GPU threads, on the

other hand, are cheaper to create and manage, since batches of GPU threads are treated

the same, it is possible to create a large number of them and run them for a shorter

duration.

The parallelization task on multiple computing systems can be performed by using

MPI for communicating via messages between distributed processes that are running in

parallel over the network. We combine MPI with OpenMP and CUDA to enable solving

tight binding problems with a H matrix that are too large to fit on a single node or

that would require an unreasonably long compute time on a single node. We also take

advantage of latest development in hardware technologies such as NVIDIA GPUDirect so

as to achieve additional improvements in performance.

4.2.1 MPI-OpenMP

In OpenMP, the goal is usually to parallelize loops. A serialized program can be

parallelized one loop at a time. When compiler directives are used, OpenMP will

automatically make loop index variables private within team threads (Master thread +

Worker threads) and global variables shared. Below is the pseudocode for spMV with

OpenMP.

Do i = 1 to Number_of_Rows

Start=row_index(i)

46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-48-2048.jpg)

![improvements may be possible using alternative sparse matrix representations such as

ELLPACK, although, it has been shown that CSR becomes very efficient when matrix

rows exceed four million [137].

Spin-orbit couplings add imaginary components to the Hamiltonian matrix doubling

the problem size and adding the burden of complex algebra operations. In conventional

TB approaches, based on the local atomic spin-orbit interaction, the size of the imaginary

part of the Hamiltonian is much smaller than the real part. Therefore, memory can be

saved by exploiting the sparsity if we split the complex TB Hamiltonian matrix into their

real and imaginary parts and then perform the eigenvalue calculation. The complex spMV

are substituted by two multiplications,

V = Mul(Hreal, q) + iMul(Himg, q) (4.1)

This has been achieved by designing a new CUDA kernel accepting mixed complex/real

arithmetic as explained in the following subsection 4.2.5.

4.2.5 Mix real-complex CUDA kernel

Sparse matrix-vector multiplication is an integral part of most numerical methods and it

is a bandwidth-limited operation on current hardware. On cache-based architectures, like

GPU, the main factors that influence performance are spatial locality in accessing the

matrix and temporal locality in re-using the elements of the vector. The new mix real-

complex CUDA kernel is based on the implementation discussed by Reguly and Giles [138]

who shows that it can outperform CUSPARSE library. The main idea of the kernel is to

let many threads cooperate on any row during spMV products, thereby increasing data

locality and decrease cache misses.

int tid = threadIdx.x;

int coopIdx = threadIdx.x%coop;

int i = (repeat*blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + tid)/coop;

__shared__ cuDoubleComplex sdata[ BLOCK_SIZE ];

for (int r = 0; r<repeat; r++)

{

cuDoubleComplex localSum = 0.0;

int rowPtr = rowPtrs[i];

49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-51-2048.jpg)

![int stop = rowPtrs[i+1]-rowPtr;

for (int j = coopIdx; j < stop; j+=coop)

{

localSum.x += values[rowPtr+j] * x[colIdxs[rowPtr+j]].x;

localSum.y += values[rowPtr+j] * x[colIdxs[rowPtr+j]].y;

}

sdata[tid] = localSum;

for (unsigned int s=coop/2; s>0; s>>=1)

if (coopIdx < s){

sdata[tid].x += sdata[tid + s].x;

sdata[tid].y += sdata[tid + s].y;

}

if (coopIdx == 0) y[i] = sdata[tid];

i += blockDim.x/coop;

}

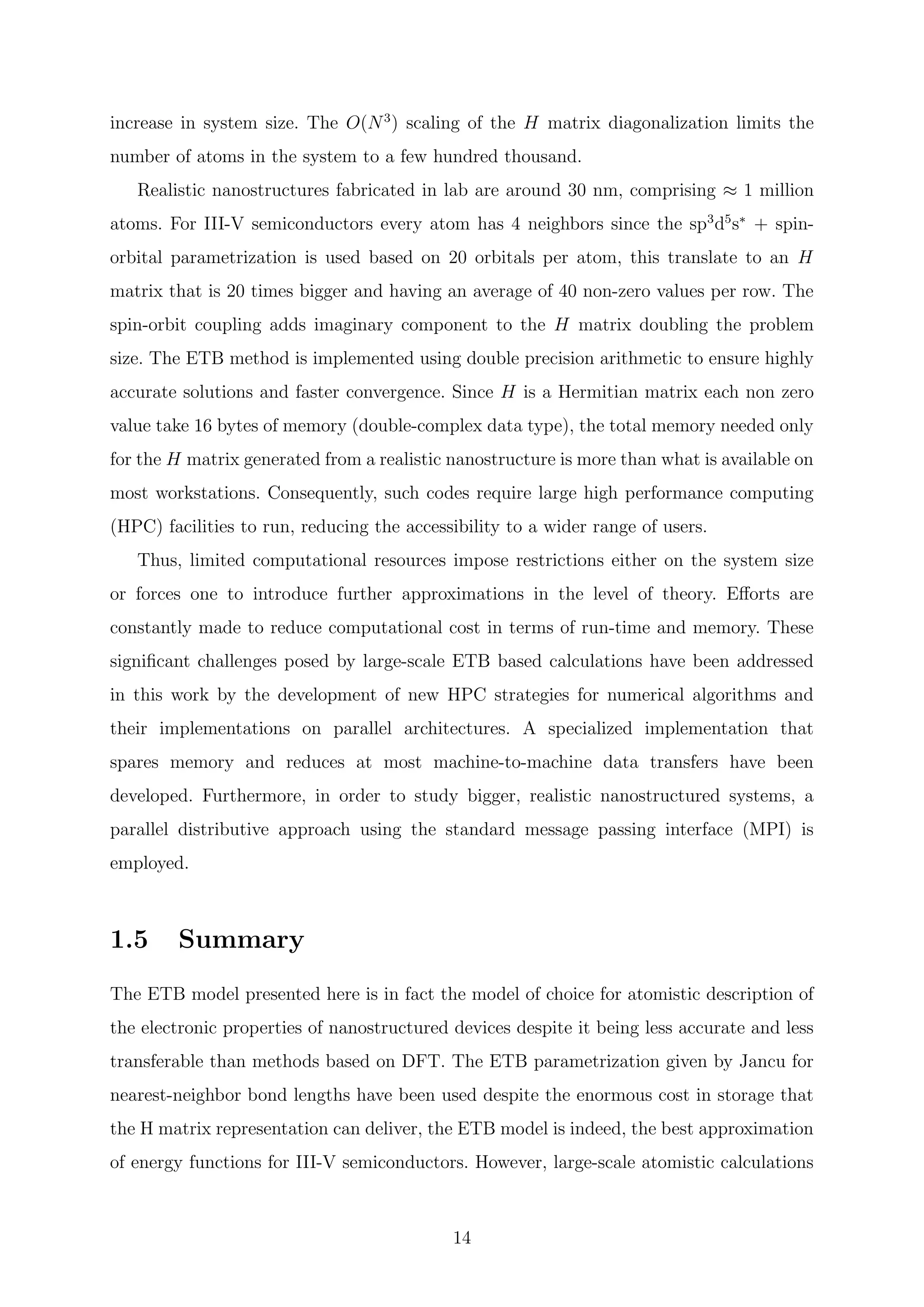

0 50000 100000 150000 200000 250000 300000 350000 400000

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

150

160

Time(Sec)

Number of atoms

Complex/Complex

Real/Real

Complex/Real

Figure 4.2: Performance of spMV operation on GPU employing different data types

Two different CUDA streams are used to carry out the matrix-vector multiplication

because the operations are independent of each other and can be executed in parallel if

enough GPU resources are available. For III-V semiconductors, every atom has 4

neighbors, Rmax ≈ 40. In contrast, the imaginary part has Rmax = 2. For this reason,

50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-52-2048.jpg)

![different tuning strategies are necessary for the two spMV operations. For the spMV

operations involving the real part, numerical experiments give the best performance

using coop = 8 and repeat = 2 in the notation of Ref. [138] and in the kernel reported

above. The spMV involving the imaginary parts is performed with coop = 1 and

repeat = 1. As seen in figure 4.2, this hybrid complex/real kernel performs much better

than the original implementation based on four real/real spMV operations that suffered

almost a factor of 2× performance degradation. This is due to the fact that the real

matrix needs to be fetched only once, decreasing the bandwidth utilization.

4.2.6 Performance enhancement using the Overlap technique

Figure 4.3: (Left) Typical sparsity pattern of a TB Hamiltonian and partitioning over

four nodes. (Right) Data exchanged between adjacent nodes

To facilitate the calculation of big nanostructures, MPI is utilized because it is one of

the dominant technologies used in HPC today. Distributive parallel computing nature of

MPI, along with being portable, efficient and flexible, is very ideal for scientific computing

bound by memory and speed limitations. However, the challenge with TB application is

that different parts of the TB Hamiltonian matrix has been distributed to different nodes

and the algorithm is executed in an independent fashion on each localized node. Therefore,

after each matrix-vector multiplication, a part of the resultant vector that is needed to

carry out future matrix-vector multiplication correctly needs to be transferred. This part

acts as an overlap between nodes that need to be exchanged. The bandwidth of the overlap

transferred is dictated by the bandwidth of the H matrix. Figure 4.3 shows the typical

51](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-53-2048.jpg)

![Chapter 5

GPU focused comprehensive study

of popular eigenvalue methods

As already outlined in Chapter 3, there are several methods that can be used to

calculate the needed eigenstates of the H matrix. Given the variety of possible methods,

it is still unclear which one is more suited and how their performance compares in a

given scenario. However, there are few methods which are more widely used given their

implementation feasibility, convergence characteristic, accuracy and reliability. Methods

such as Lanczos, Jacobi-Davidson and conjugate gradient are popular and widely

utilized in tight binding calculations [139–141]. Recently, a new method called FEAST is

gaining popularity [142, 143]. Hence studying, optimizing and benchmarking them for

recent HPC and GPU architectures is of importance for the given application domain.

Today, larger and faster computing systems are widely accessible. Supercomputers

and high-end expensive computing systems are being utilized to accelerate computation

in a parallel distributed, cluster or grid computing setting. The advent of GPUs have

grasped the attention of most of the scientific computation community. Developing

algorithms that can ideally scale over such a system is an important component for

transferring the hardware feature into actual beneficial speedups. In recent times, there

has been an extensive effort being put in translating algorithms initially designed for

sequential processors to now days HPC system which normally deal with either SIMD or

multiple-instruction-multiple-data (MIMD) scenario. However, a lot of aspects need to

be considered to result in speedups while dealing with parallel computing. Hence, often

60](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-62-2048.jpg)

![5.1.1 Jacobi-Davidson method

The Jacobi-Davidson method is an iterative subspace method for computing one or more

eigenpairs of large sparse matrices. In this method, each iteration has two phases: the

subspace extraction and the subspace expansion.

For the subspace expansion phase, given an approximate eigenpair (θi, ui) close to

(λi, vi), with ui ∈ U, where U is the subspace, and θi =

u∗

i Hui

u∗

i ui

is the Rayleigh quotient of

ui, taken as approximate eigenvalue because it minimizes the two-norm of the residual:

r = Hui − θiui . To expand U in an appropriate direction lets look for an orthogonal

correction t ⊥ ui such that ui + t satisfies the eigenvalue equation:

H(ui + t) = λi(ui + t) (5.1)

Lets try to find eigenvalues closest to some given target τ, initially, lets consider this

to be the same as the chosen Lanczos shift τ = s. In the above equation,

(H − τI)t = −r + (λi − θi)ui + (λi − τ)t (5.2)

t and | λ − τ | are small and can be neglected. When we multiply both sides of

equation 5.2 by the orthogonal projection I − uiu∗

i . We have the following equation

(I − uiu∗

i )(H − τI)(I − uiu∗

i )t = −r (5.3)

where t ⊥ ui. We solve equation 5.3 only approximately using generalized minimal

residual method (GMRES) and its approximate solution is used for the expansion of the

subspace [144].

To save GPU memory, the process is enhanced by restarting the Jacobi-Davidson

method with a few recently found ui in this way, the dimension of the search subspace is

restricted [145]. In order to avoid the found eigenvalues from reentering the

computational process, the new search vectors are explicitly made orthogonal to the

computed eigenvectors.

As stated above, the interior eigenvalues are of interest. The Ritz vectors represents

poor candidates for restart since they converge monotonically towards exterior eigenvalues.

One solution to this problem is using the harmonic Ritz vectors. The harmonic Ritz values

62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8ee4b26-cb6a-4d2f-a764-bedcd25f170c-160229035204/75/Thesis_Walter_PhD_final_updated-64-2048.jpg)

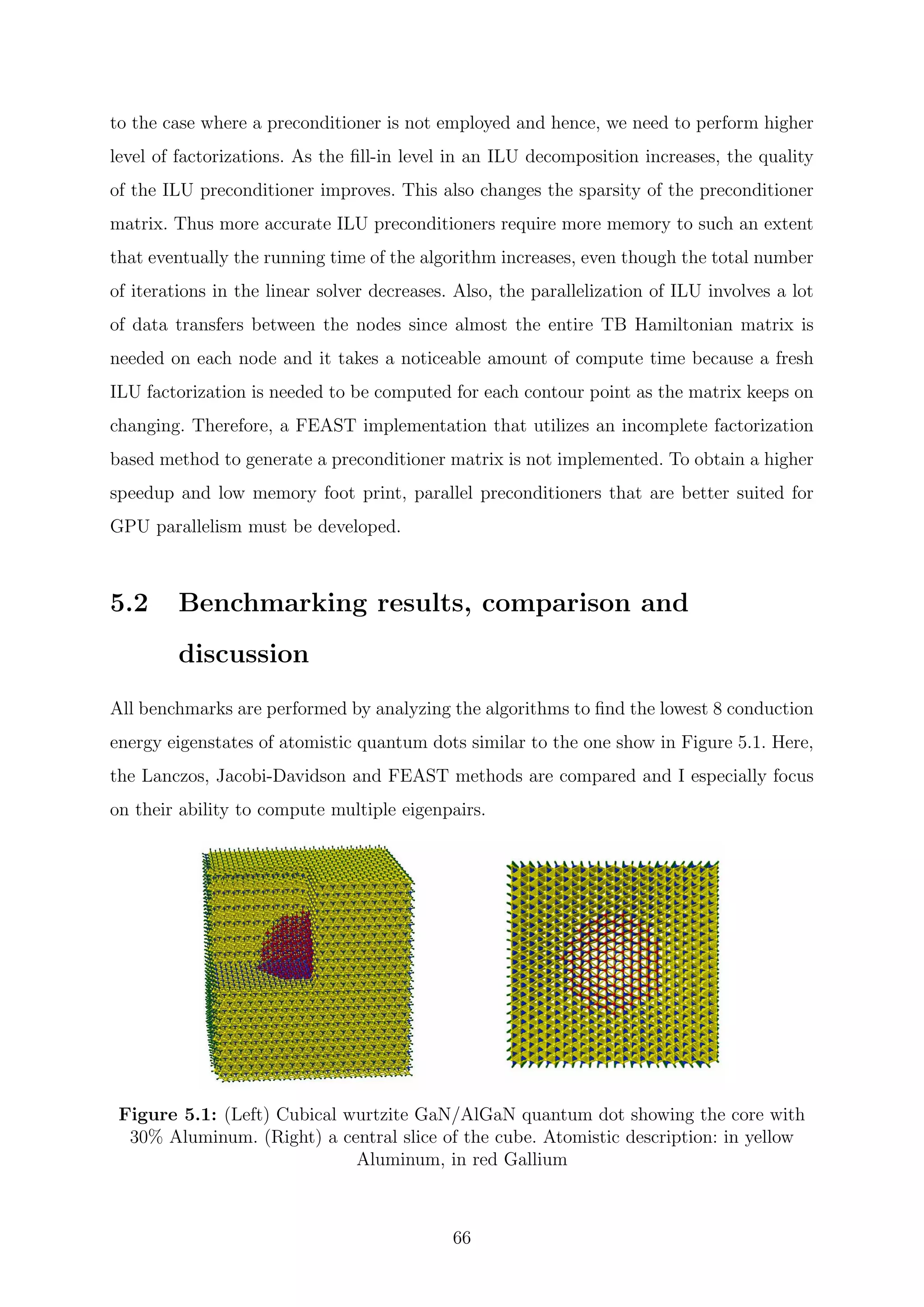

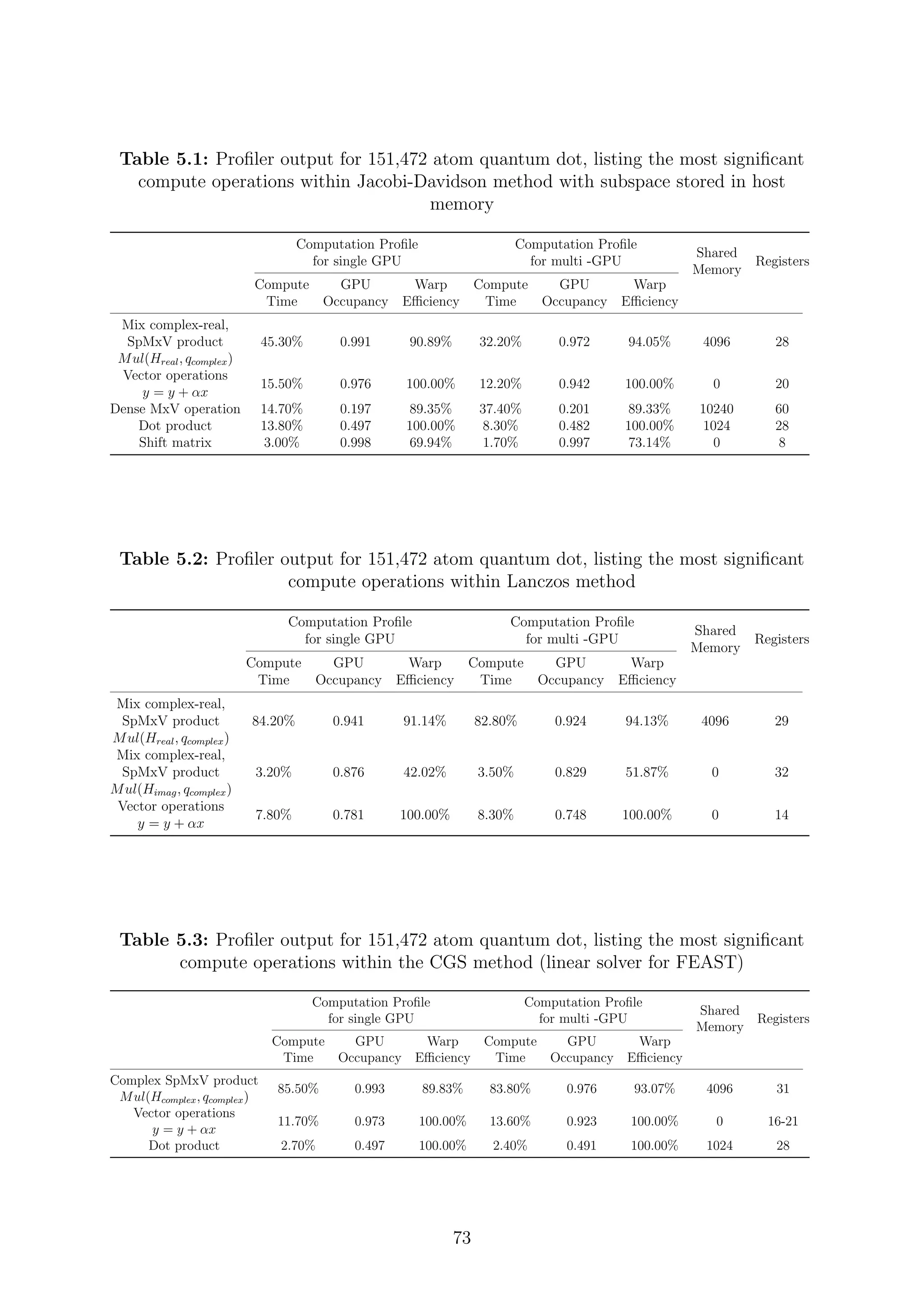

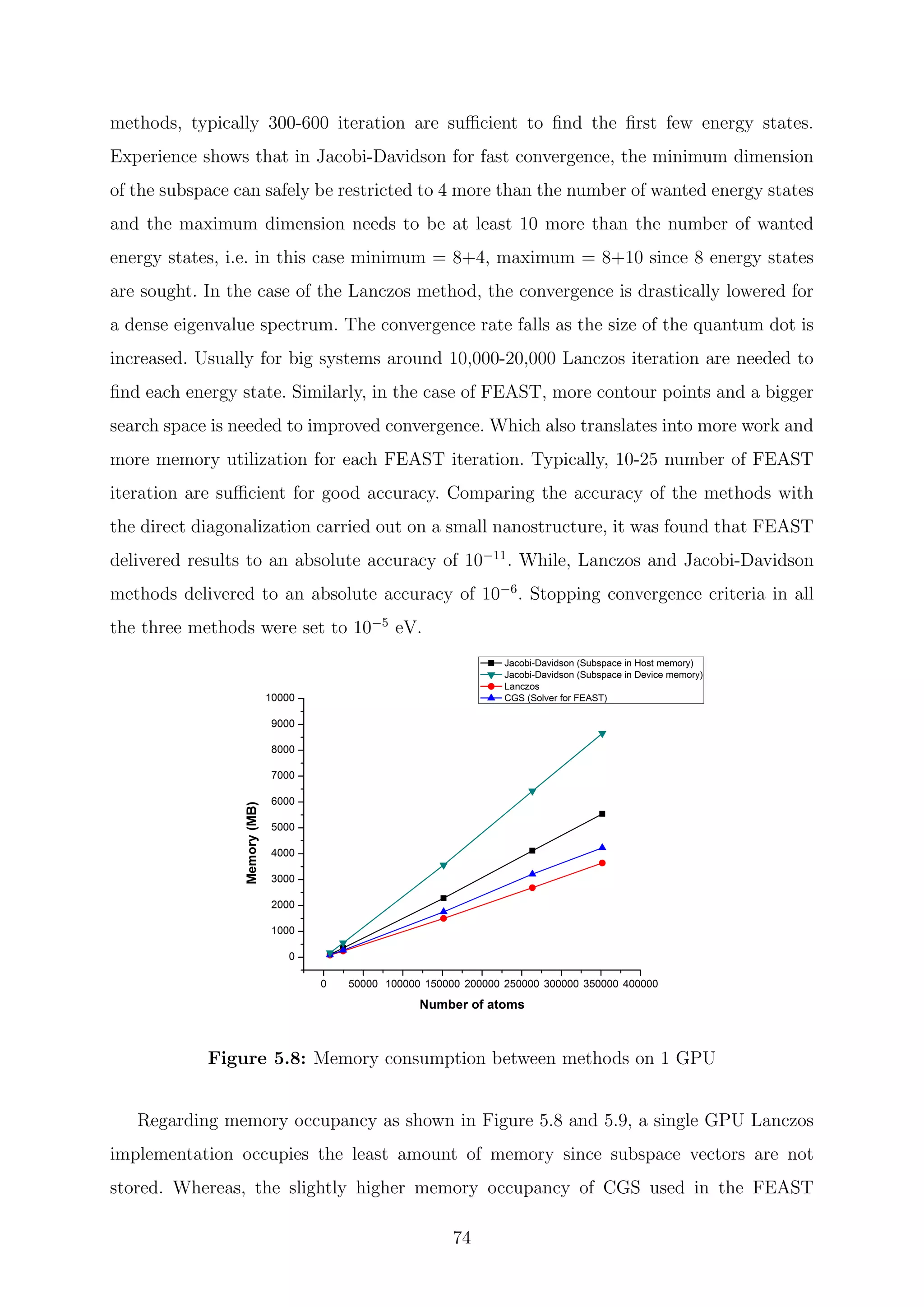

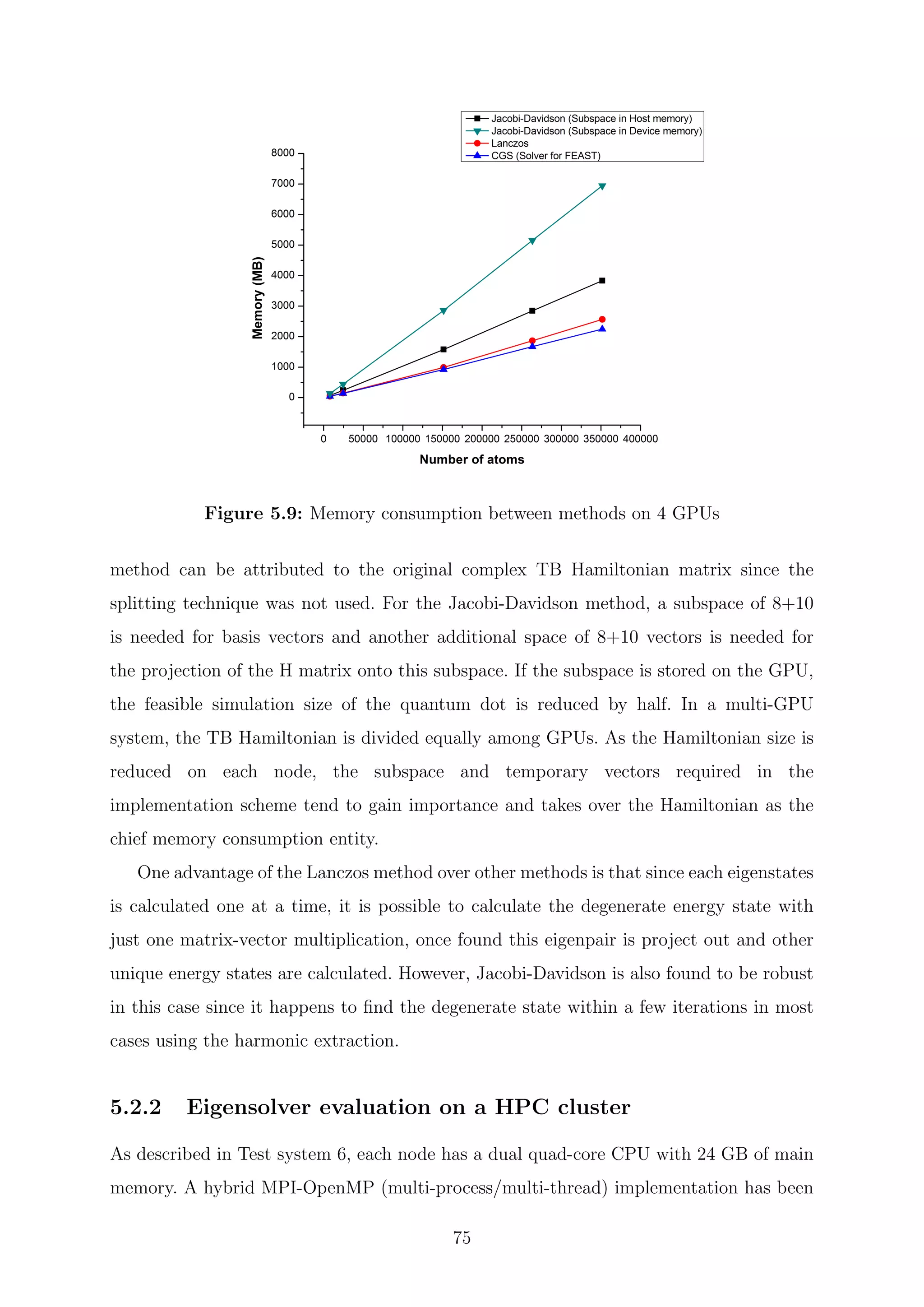

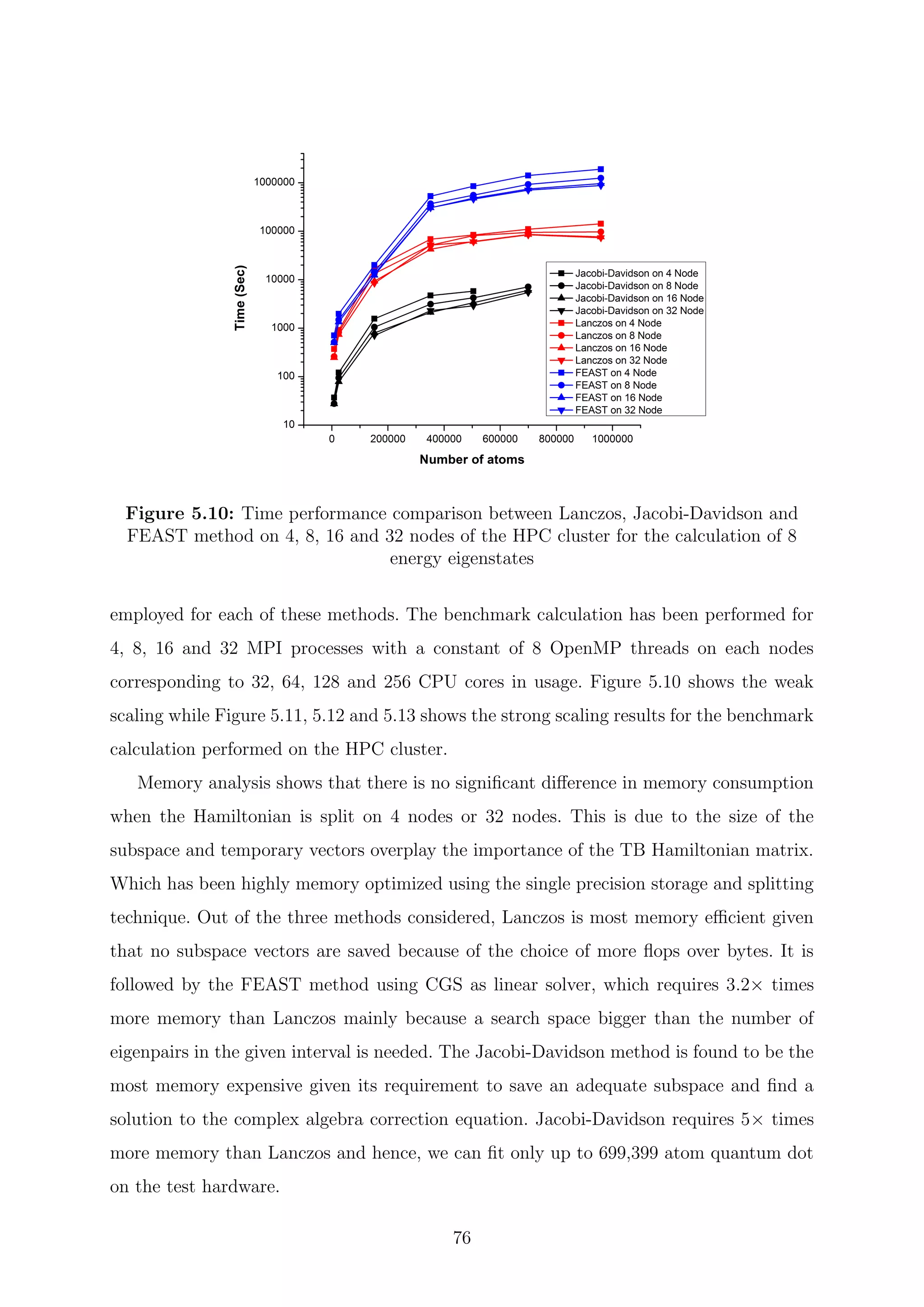

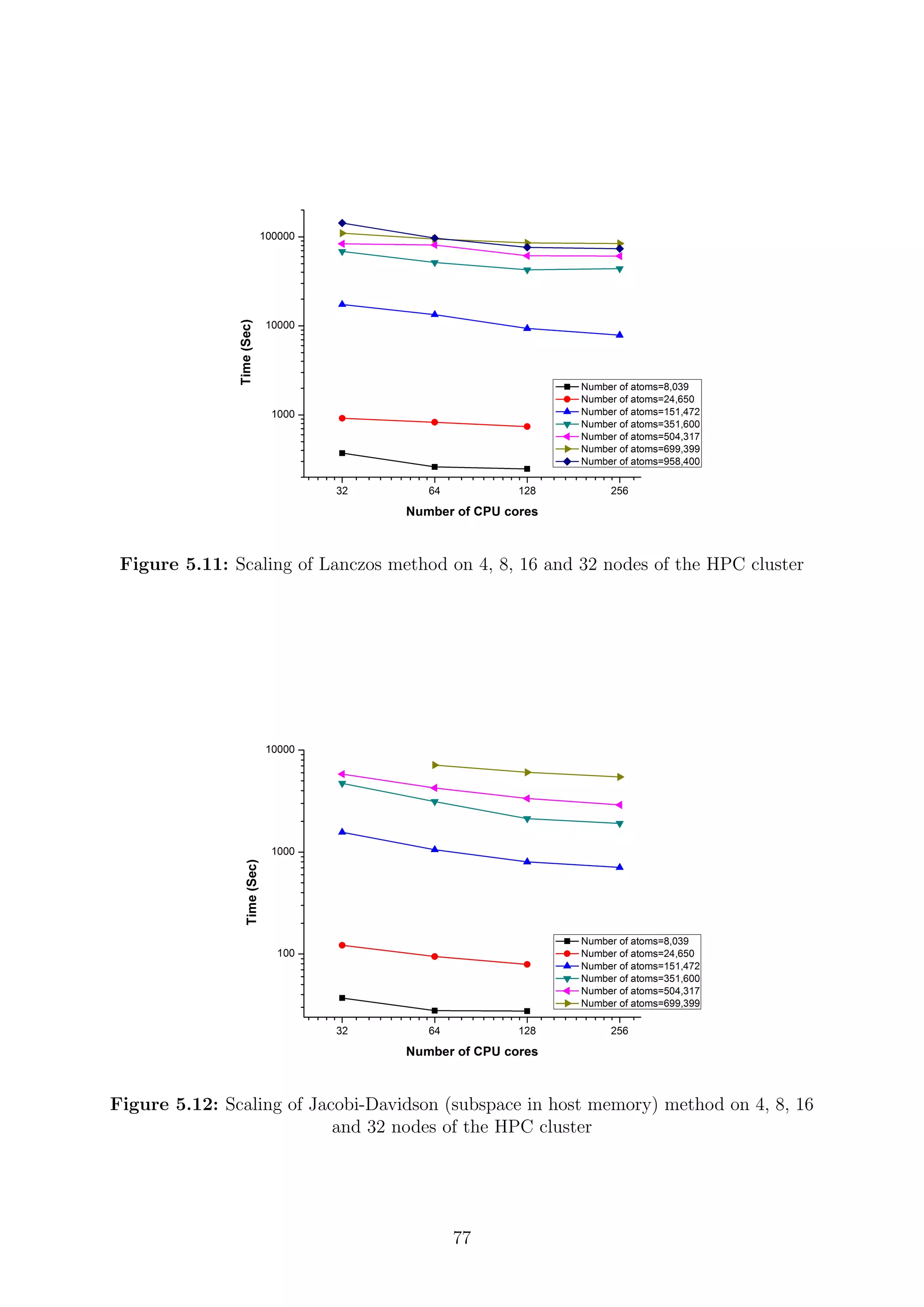

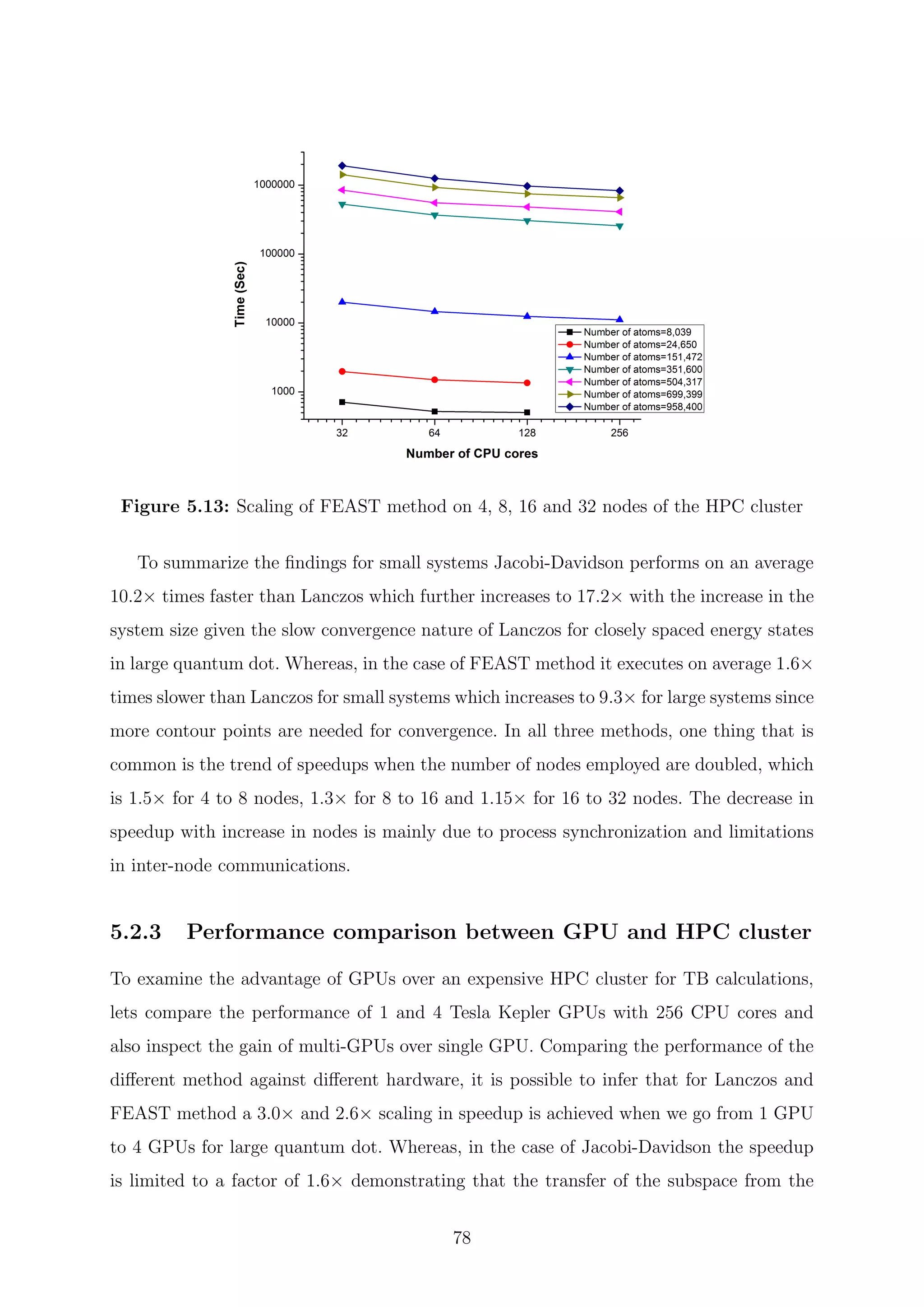

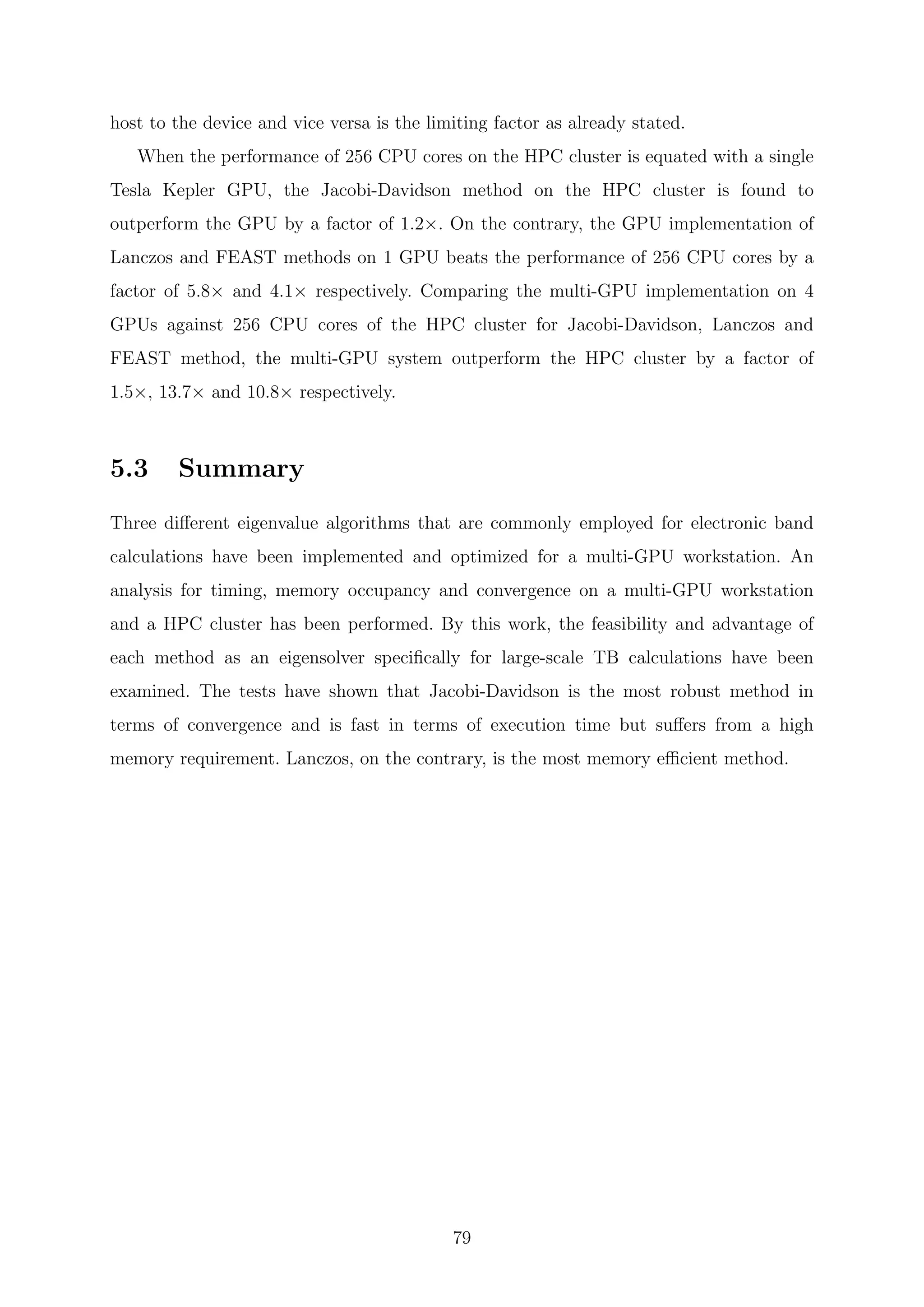

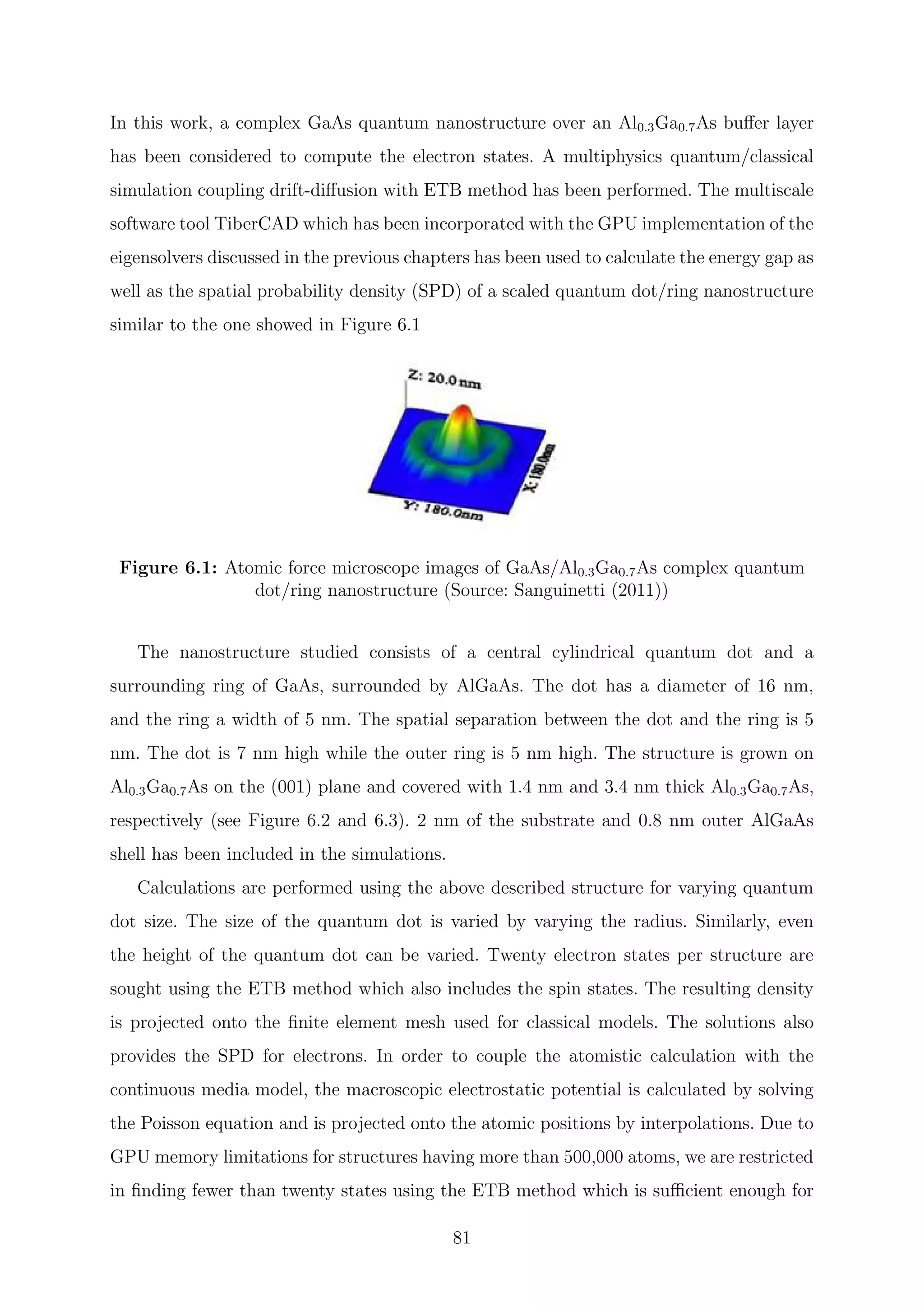

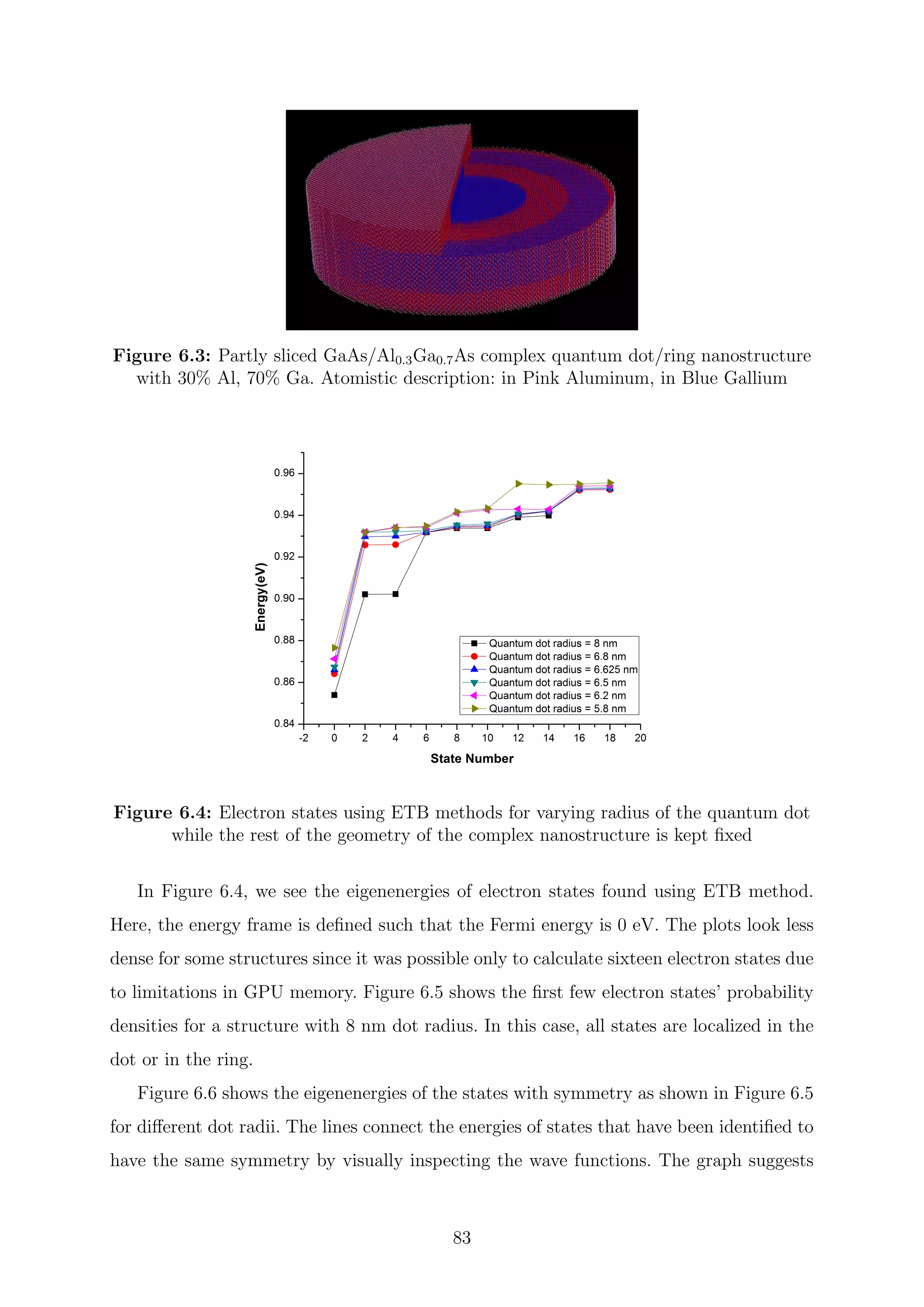

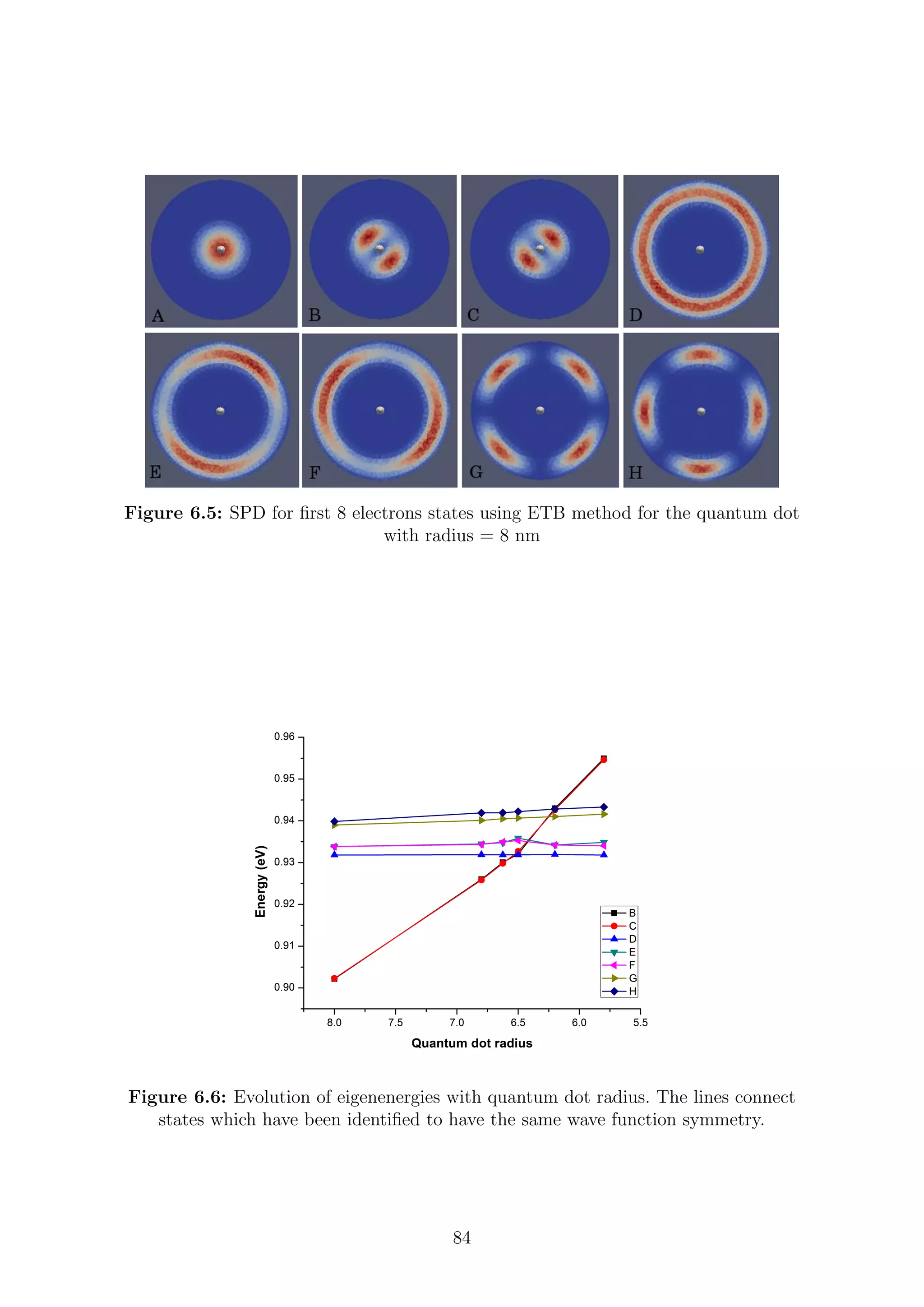

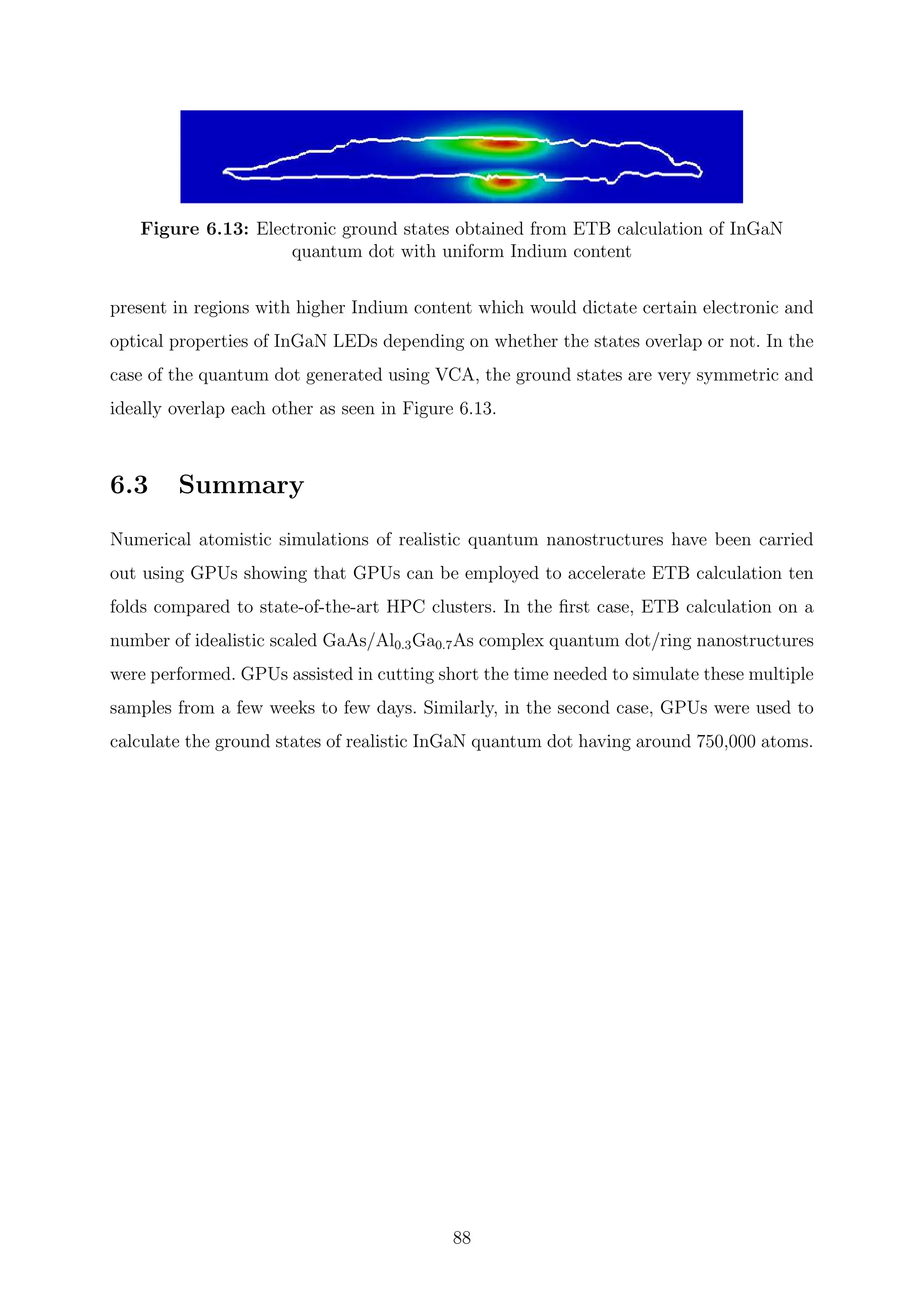

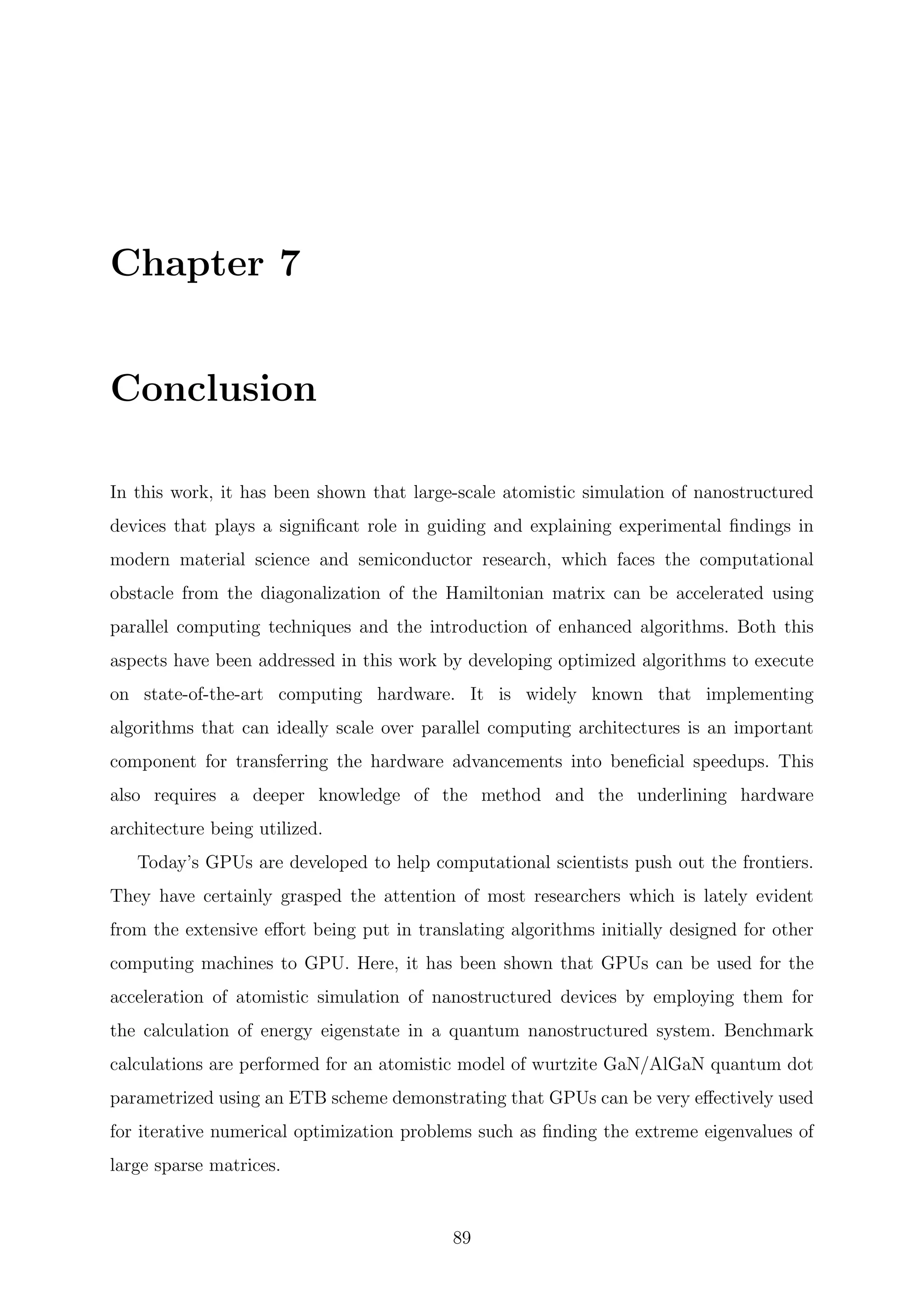

![are inverses of the Ritz values of H−1