Systems Engineering Tools And Methods Engineering And Management Innovations 1st Edition Ali K Kamrani

Systems Engineering Tools And Methods Engineering And Management Innovations 1st Edition Ali K Kamrani

Systems Engineering Tools And Methods Engineering And Management Innovations 1st Edition Ali K Kamrani

![30 ◾ Systems Engineering Tools and Methods

© 2011 by Taylor Francis Group, LLC

where each increment will have its own set of threshold and objective values set by

the user, dependent upon the availability of mature technology (DoD Instruction

Number 5000.02, 2008).

The distinguishing feature of highly complex, adaptive systems is that the over-

all behavior and properties cannot be described or predicted from the union of their

subsystems and subsystems’ interaction. The system–subsystem architecture and

subsystem interactions either do not simplify the complexity of the description or

fail to represent the system properties.

The reduction in total system entropy comes about through the dynamic emer-

gent properties and behaviors, rather than a static architecture and encapsulated

subsystem interactions.

Complex systems unite their subsystems (i.e., add organization) in a way that

reduces total entropy, and defy reduction in entropy through hierarchical decom-

position. The reduction in entropy is the result of the emergent properties and

behaviors. There are significant barriers to relating the components to the over-

all system (Abbott, 2007): (1) The complexity of the system’s description is not

reduced by formulating it in terms of the descriptions of the system’s components,

and (2) combining descriptions of the system’s components does not produce an

adequate description of the overall system, that is, such a description is no simpler

than propagating the descriptions of the components.

Natural systems that exhibit such complexity, such as organisms, are char-

acterized by robustness and adaptability, in contrast to human-designed systems

that exhibit fragile emergent properties. This has been attributed to the top-down

nature of the requirements-driven human-built system development process,

in contrast with the bottom-up processes that occur through natural selection

(Abbott, 2007):

One reason is that human engineered systems are typically built using a

top-down design methodology. (Software developers gave up top-down

design a quarter century ago. In its place we substituted object-oriented

design—the software equivalent of entity-based design.) We tend to

think of our system design hierarchically. At each level and for each

component we conceptualize our designs in terms of the functionality

that we would like the component to provide. Then we build something

that achieves that result by hooking up subcomponents with the needed

properties. Then we do the same thing with subcomponents… This is

quite different from how nature designs systems. When nature builds a

system, existing components (or somewhat random variants of existing

components) are put together with no performance or functionality

goal in mind. The resulting system either survives [or reproduces] in its

environment or it fails to survive.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1245042-250518112103-c696b448/75/Systems-Engineering-Tools-And-Methods-Engineering-And-Management-Innovations-1st-Edition-Ali-K-Kamrani-50-2048.jpg)

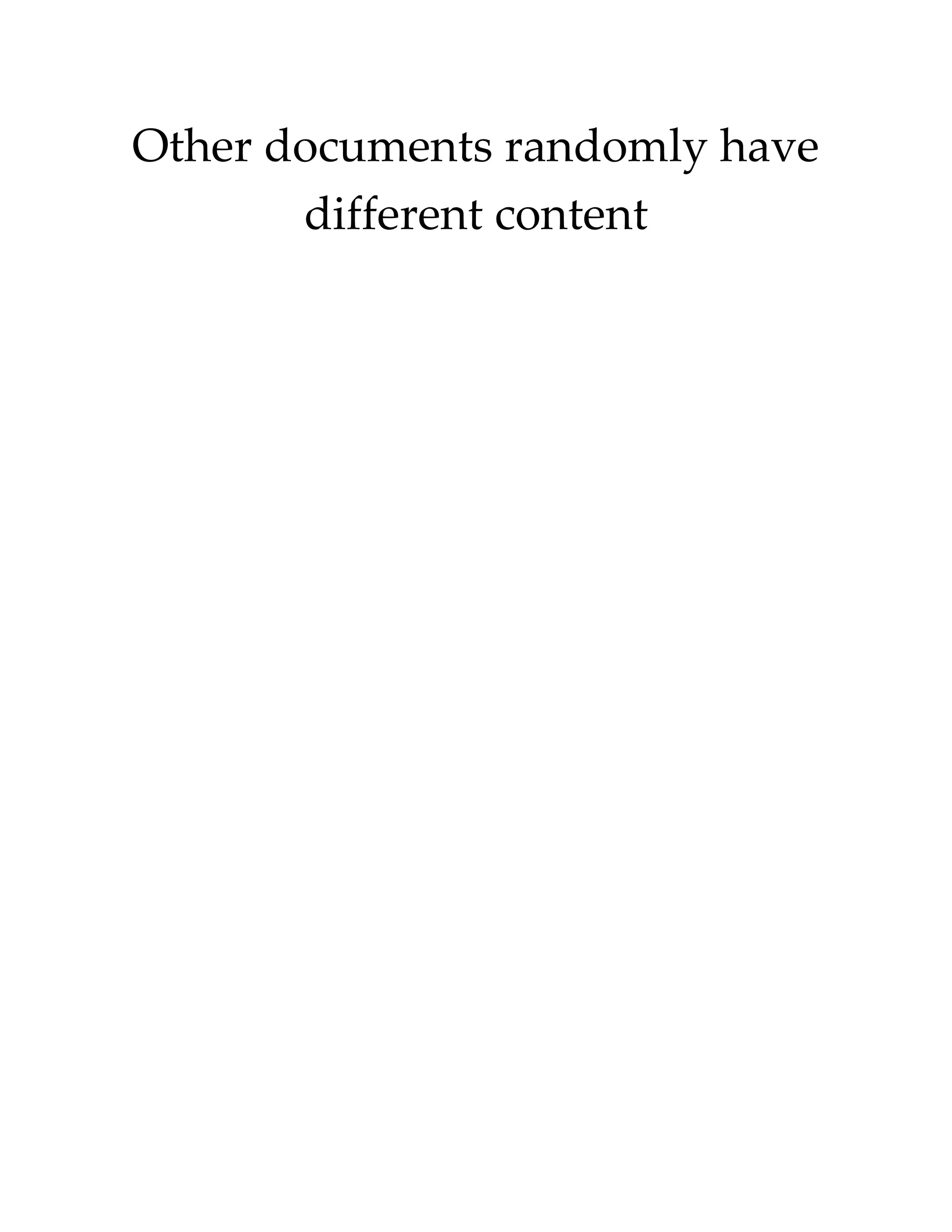

![Wenn wir eine einzelne Flimmerzelle nehmen, sie, ganz vom

Körper isolirt, frei schwimmen lassen und abwarten, bis

vollkommene Ruhe eingetreten ist, so können wir die eigenthümliche

Bewegung ihrer Cilien wieder hervorrufen, wenn wir eine kleine

Quantität von Kali oder Natron der Flüssigkeit zufügen, eine

Quantität, welche nicht so gross ist, dass ätzende Effecte auf die

Zelle hervorgebracht werden, welche aber genügt, um, indem ein

Theil davon in die Zelle eindringt, eine gewisse Veränderung an ihr

zu erzeugen. Es ist aber besonders interessant, dass die Zahl der

fixen Substanzen, durch welche wir das Flimmer-Epithel reizen

können, sich auf diese beiden beschränkt. Daraus erklärt es sich,

dass P u r k i n j e und V a l e n t i n, welche zuerst und zwar sogleich in

sehr ausgedehnter Weise Experimente über die Flimmerbewegung

anstellten, nachdem sie mit einer sehr grossen Zahl von Substanzen

experimentirt und, wer weiss was Alles versucht hatten,

mechanische, chemische und elektrische Reize, zuletzt zu dem

Schlusse kamen, es gebe überhaupt kein Reizmittel für die

Flimmerbewegung. Ich hatte das Glück, zufällig auf die

eigenthümliche Thatsache zu stossen, dass Kali und Natron solche

Reizmittel seien[145]. Neuerlich hat W. K ü h n e entdeckt, dass unter

den gasförmigen Substanzen sich noch ein mächtiger Erreger der

Flimmerbewegung findet, nehmlich der Sauerstoff, während

Kohlensäure und Wasserstoff dieselbe hemmen. Gewiss können wir

hier keinen Nerveneinfluss mehr zu Hülfe rufen; derselbe erscheint

um so weniger zulässig, als nach bekannten Erfahrungen die

Flimmerbewegung im todten Körper sich noch zu einer Zeit erhält,

wo andere Theile schon zu faulen angefangen haben. Ich sah die

Flimmer-Epithelien der Stirnhöhlen und der Trachea in menschlichen

Leichen noch 36 bis 48 Stunden post mortem in vollständiger](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1245042-250518112103-c696b448/75/Systems-Engineering-Tools-And-Methods-Engineering-And-Management-Innovations-1st-Edition-Ali-K-Kamrani-55-2048.jpg)

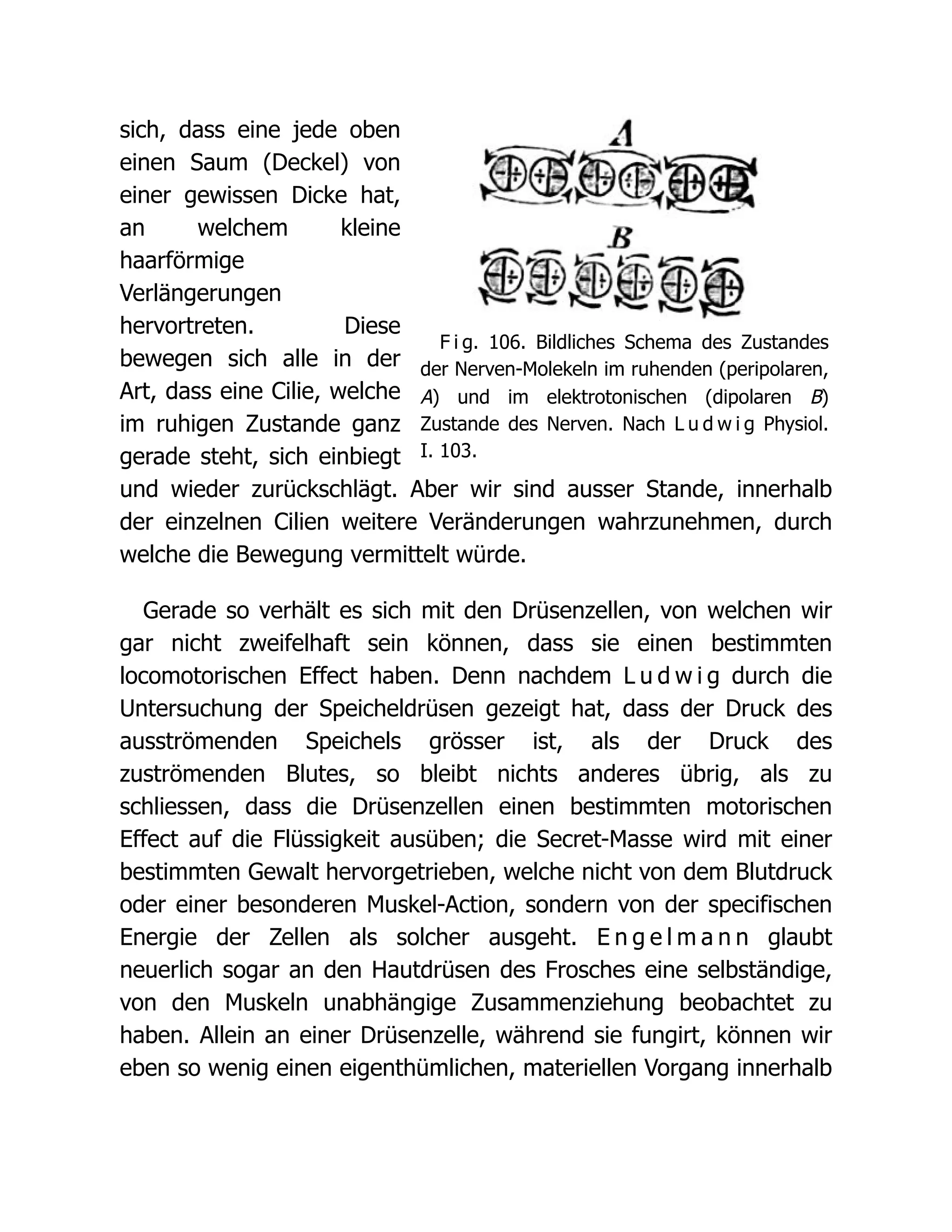

![elektrischen Strömungen die Ganglienzellen anzusehen hat. Ob

jedoch die Vorgänge im Innern dieser Zellen selbst elektrische sind,

das ist bis jetzt nicht bekannt. Gewiss liegt es nahe, zu vermuthen,

dass auch in den Ganglienzellen selbst elektrische Vorgänge

stattfinden, ja Manches spricht dafür, dass diese Zellen die Fähigkeit

besitzen, diese Vorgänge zu modificiren, d. h. abzulenken, zu

verstärken und zu schwächen. Die empfindenden Nervenfasern sind

fast durchgehends an ihren peripherischen Enden mit Nervenzellen

in Verbindung, so dass jede von aussen eintretende Veränderung

(Reizung) erst die Nervenzelle passiren muss, ehe sie in die

eigentliche Nervenfaser übergeht und zu den centralen

Ganglienzellen geleitet wird. Auch die motorischen Nervenfasern

laufen kurz vor ihrem Ende vielfach in besondere gangliöse Apparate

aus, gleichwie sie an ihrem Ursprunge aus Ganglienzellen

hervorgehen. Welche andere Bedeutung können diese Zellen haben,

als die einer S a m m l u n g der in den Nerven geschehenden

Bewegung, welche einerseits die Möglichkeit einer verschiedenen

A b l e n k u n g des Nervenstromes (Direction, Derivation),

andererseits die Möglichkeit einer zeitweisen A b s c h w ä c h u n g

und H e m m u n g desselben und dann einer nachfolgenden

V e r s t ä r k u n g mit vielleicht explosiver Wirkung gewährt?

Gleichwie früher das Studium der Reflexvorgänge, so führt

gegenwärtig die sich immer mehr ausdehnende Kenntniss der von

mir so genannten M o d e r a t i o n s - E i n r i c h t u n g e n im

Nervensystem[146], wofür zuerst der Vagus, dann der Splanchnicus,

schliesslich selbst das Gehirn so ausgezeichnete experimentelle

Beispiele geliefert haben, mit Nothwendigkeit auf Ganglienzellen und

nicht auf Nervenfasern zurück. Erscheinungen, wie die des

Elektrotonus, sind im lebenden Organismus nicht bekannt. Trotzdem

lassen die Vorgänge der Reflexion und Derivation, der Hemmung](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1245042-250518112103-c696b448/75/Systems-Engineering-Tools-And-Methods-Engineering-And-Management-Innovations-1st-Edition-Ali-K-Kamrani-63-2048.jpg)

![Manche Verschiedenheiten der eintretenden Thätigkeiten erklären

sich offenbar durch die v e r s c h i e d e n e E n e r g i e der einzelnen

Ganglienzellen: wie wir Bewegungs- und Empfindungszellen

unterscheiden, so können wir auch innerhalb der Bewegungszellen

die den einzelnen muskulösen Apparaten zugehörigen von einander

trennen, und ebenso innerhalb der Empfindungszellen die

gewöhnlichen spinalen Ganglienzellen von den Riech-, Seh- und

Hörzellen u. s. w. des Gehirns sondern. Andere Verschiedenheiten

dagegen resultiren aus der combinirten Erregung und

Zusammenwirkung (S y n e r g i e) mehrerer, in sich verschiedener

Ganglienzellen oder Ganglienzellen-Gruppen. Jede Reflex-Erregung,

jede bewusste und willkürliche Erregung setzt die gleichzeitige oder

doch innerhalb kurzer Zeiträume auf einander folgende Thätigkeit

verschiedener Ganglienzellen voraus. Für viele Fälle sind wir im

Stande, durch eine genaue Analyse des Vorganges diejenigen

Gruppen zu bezeichnen, welche in Wirksamkeit treten. Aber das

eigentliche Wesen der Erregung der einzelnen Zellen selbst zu

erklären, sind wir bis jetzt nicht befähigt.

Bei einer früheren Gelegenheit[147] habe ich darauf aufmerksam

gemacht, dass allerdings auch bei den Erregungsvorgängen der

Centren sich Zustände der S p a n n u n g und der E n t l a d u n g

unterscheiden lassen. „Man schliesst sich“, sagte ich damals, „mit

diesem bildlichen Ausdrucke sowohl an die Terminologie der

Psychologen, als auch an die der Physiker und Praktiker an, und man

gewinnt wenigstens einen, die Thatsachen kurz bezeichnenden

Ausdruck, welcher die Möglichkeit zulässt, ohne sie jedoch

nothwendig zu machen, dass auch die Zustände der Ganglien sich

den bekannten Zuständen elektrischer Theile unterordnen“. Die

kleinste peripherische oder centrale Erregung setzt zunächst eine](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1245042-250518112103-c696b448/75/Systems-Engineering-Tools-And-Methods-Engineering-And-Management-Innovations-1st-Edition-Ali-K-Kamrani-66-2048.jpg)

![einzelnen Zellen kleine (schwärzliche)

Fettkörnchen, in zweien Vacuolen. Vergr. 300.

begannen, wie ich schon

früher (S. 64, 189)

erwähnt habe, die Beobachtungen mit dem Studium der

Flimmerzellen, der Pigmentzellen und der farblosen Blutkörperchen,

denen sich endlich durch die Entdeckung v o n

R e c k l i n g h a u s e n's die, trotz aller meiner Anstrengungen bis

dahin von Vielen kaum noch als Elemente anerkannten

Bindegewebskörperchen, sowie die Eiterkörperchen anschlossen.

Manche der hier in Frage kommenden Erscheinungen waren

allerdings schon länger bekannt, aber anderen Reihen von

Vorgängen angeschlossen. Ich selbst hatte sie in höchst

charakteristischer Weise an zwei verschiedenen Arten von Elementen

gesehen und gezeichnet, nehmlich an Exsudatzellen und an

Knorpelkörperchen[148]. Indess war damals die Neigung, alle

Veränderungen der Zellen auf Exosmose und Endosmose

zurückzuführen, so vorherrschend, dass ich im Zweifel geblieben

war, ob ich nicht Erscheinungen der S c h w e l l u n g und

S c h r u m p f u n g vor mir hätte, welche durch bloss mechanische

Einwirkung von Flüssigkeiten verschiedener Concentration

herbeigeführt wurden. Die zum Theil sehr auffälligen osmotischen

Veränderungen[149] der Zellen entsprechen zum Theil dem, was ich

an einer anderen Stelle (S. 174, Fig. 61, e–h) von den rothen

Blutkörperchen beschrieben habe, gehen jedoch noch darüber

hinaus und sie konnten wohl als Grund der grössten

Formveränderungen angesehen werden. Die neueren Beobachter

sind gerade im Gegentheil so sehr von der Allgegenwart und

Allwirkung des Protoplasma überzeugt, dass manche von ihnen auch

alle diese, der wahren Osmose angehörigen Erscheinungen mit zu

den Wirkungen des Protoplasma rechnen. Wie mir scheint, wird noch](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1245042-250518112103-c696b448/75/Systems-Engineering-Tools-And-Methods-Engineering-And-Management-Innovations-1st-Edition-Ali-K-Kamrani-72-2048.jpg)