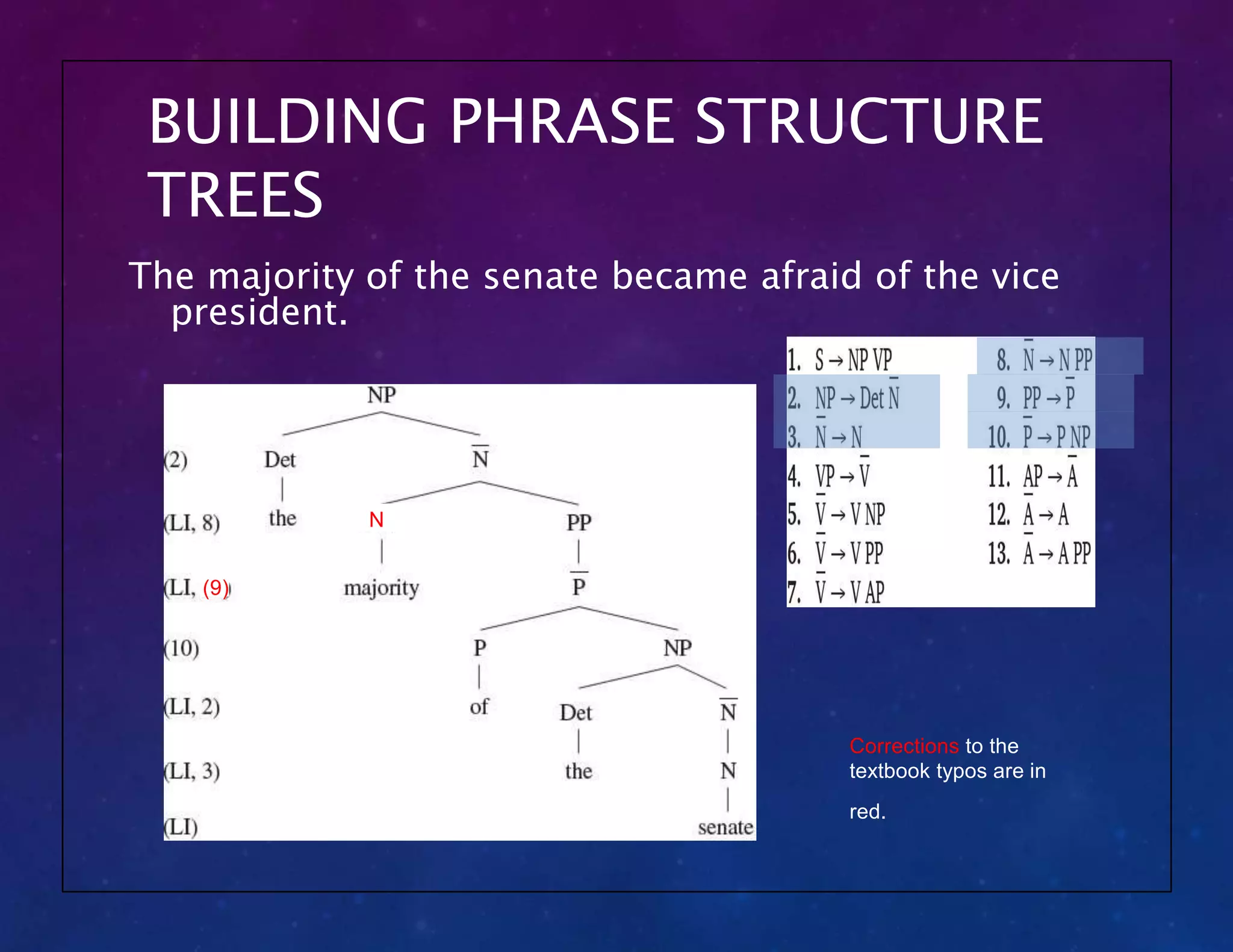

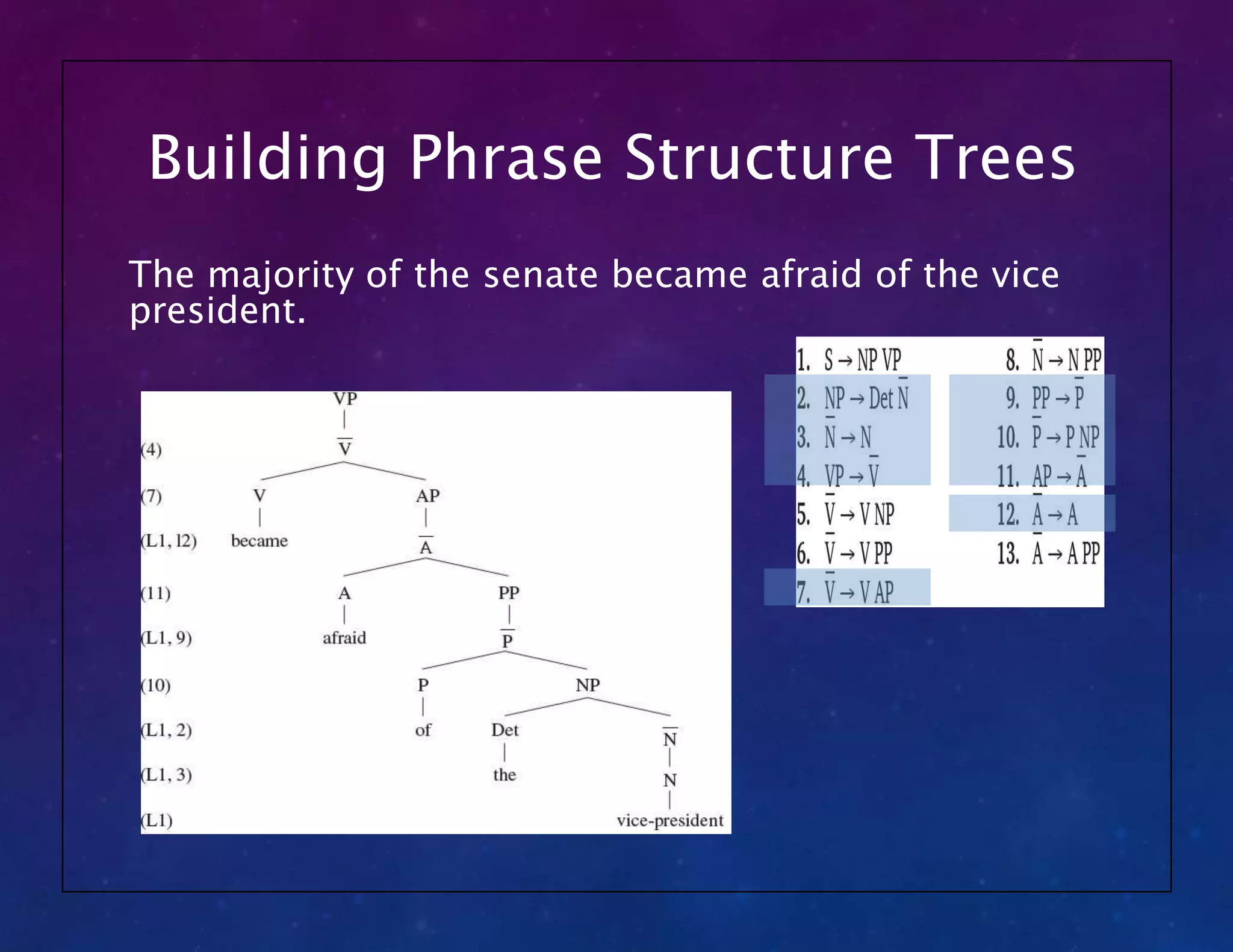

This document discusses syntax and sentence structure. It covers the following key points in 3 sentences:

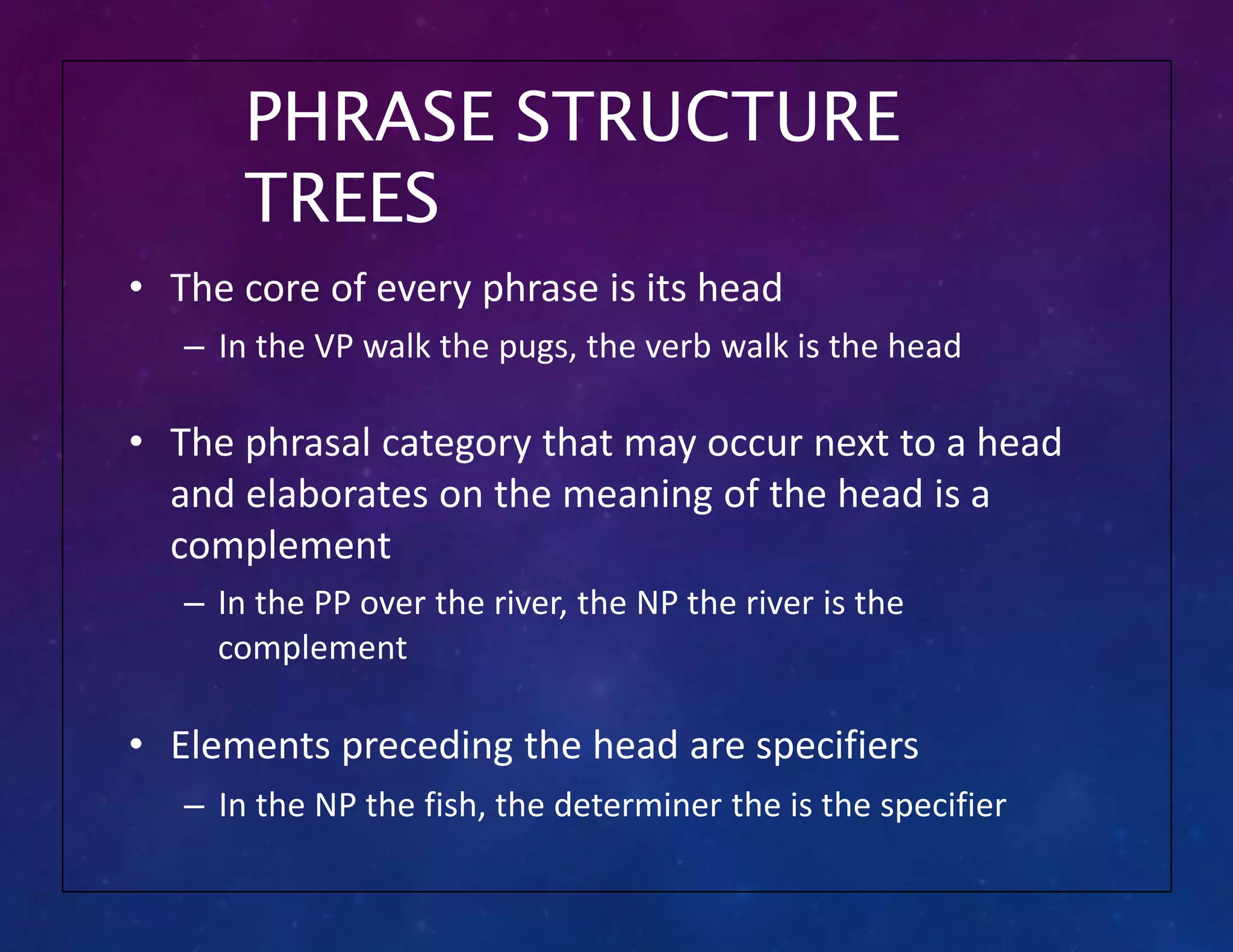

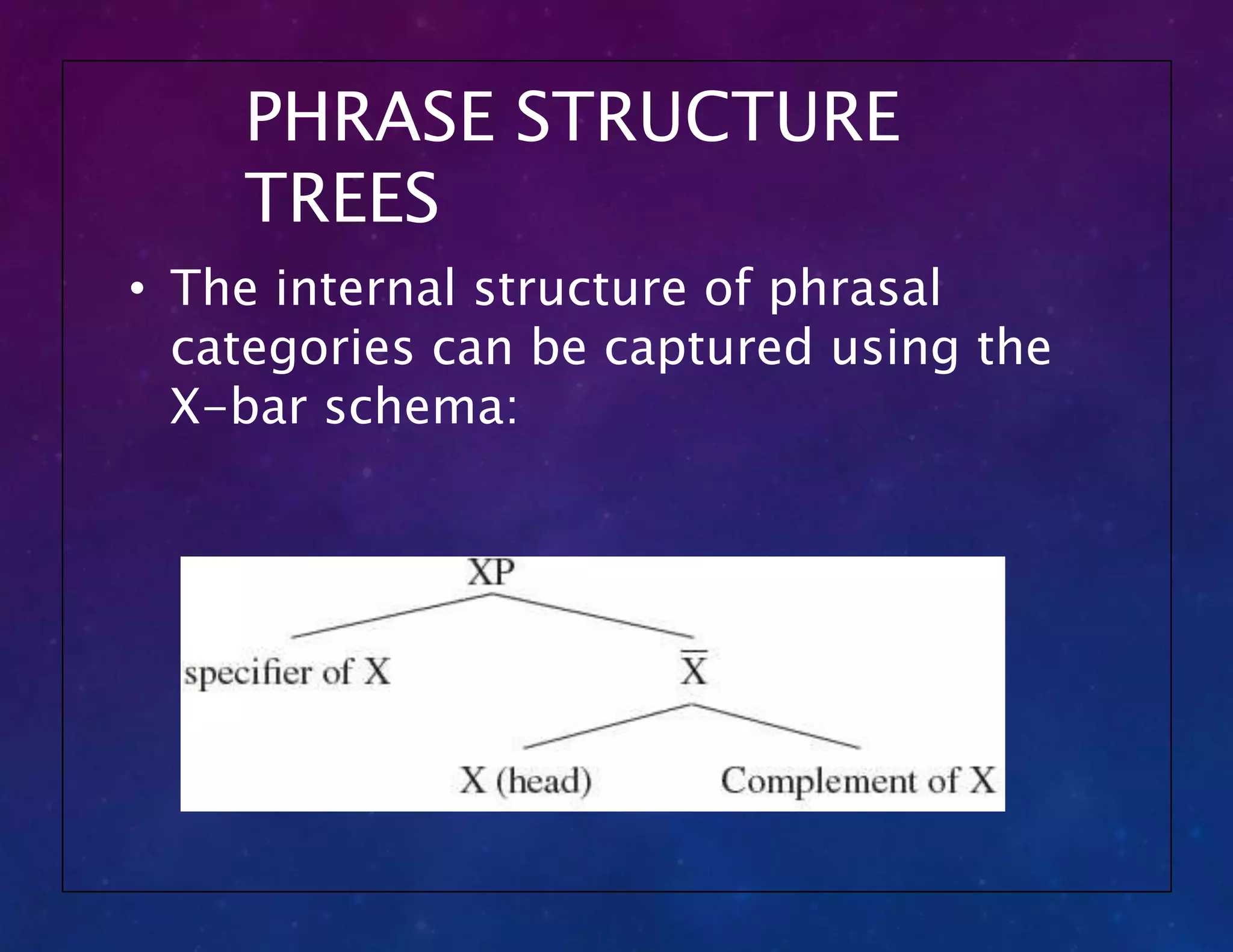

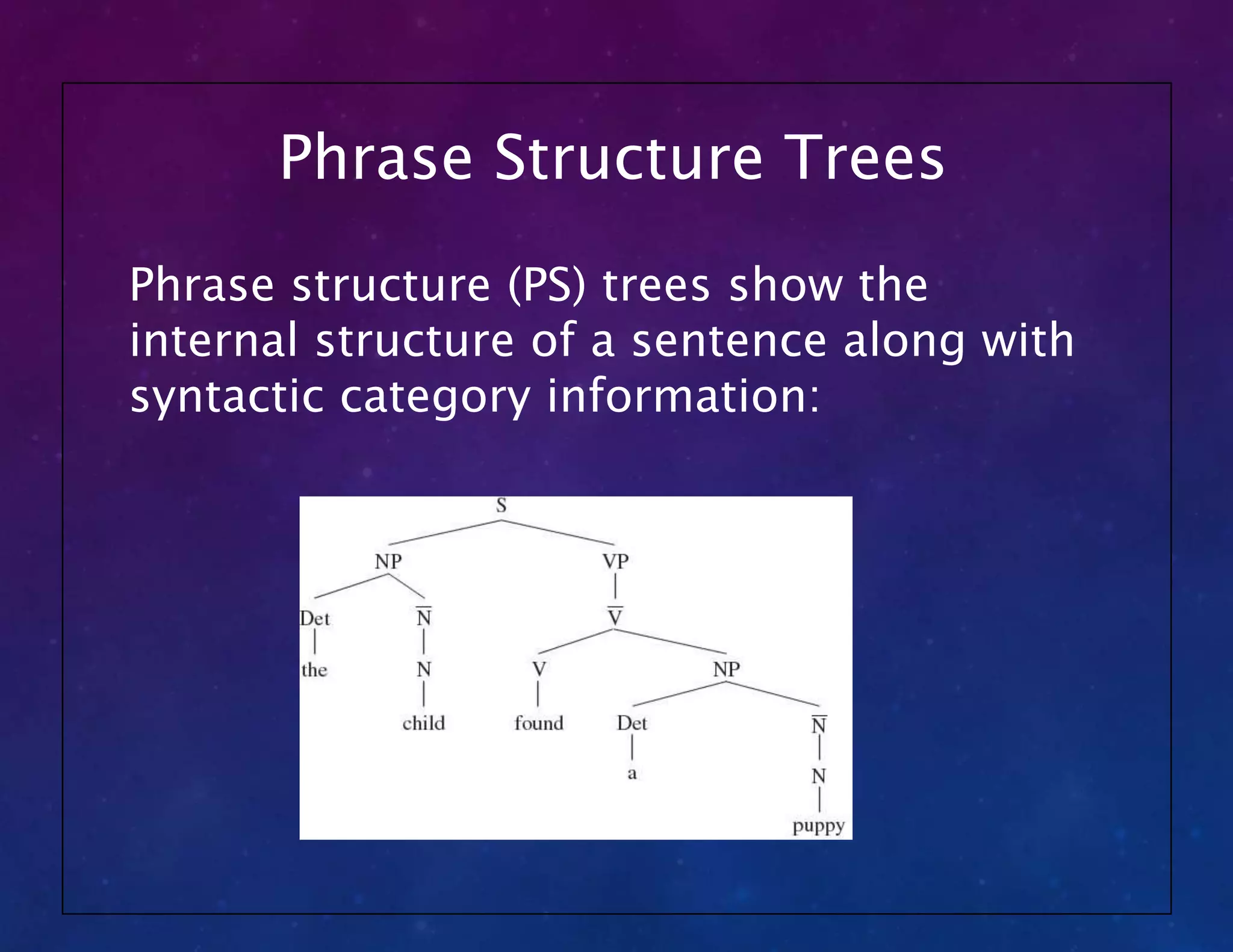

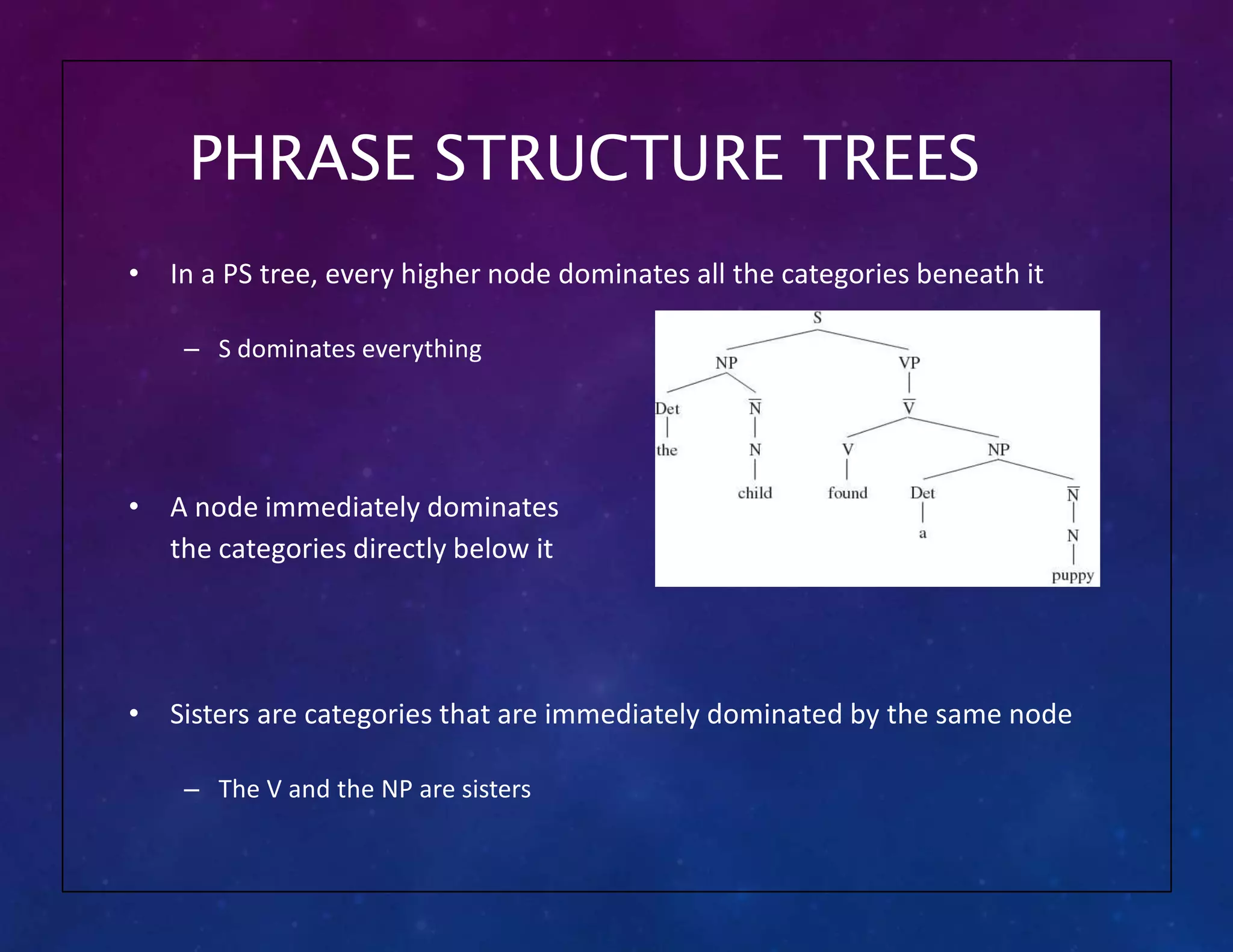

Syntax rules specify how words are combined into phrases and sentences, including word order and grammatical relationships. These rules allow humans to produce an infinite number of sentences, even though our mental dictionaries are finite. Phrase structure trees represent the hierarchical groupings of words in a sentence based on syntactic categories like noun phrases and verb phrases.

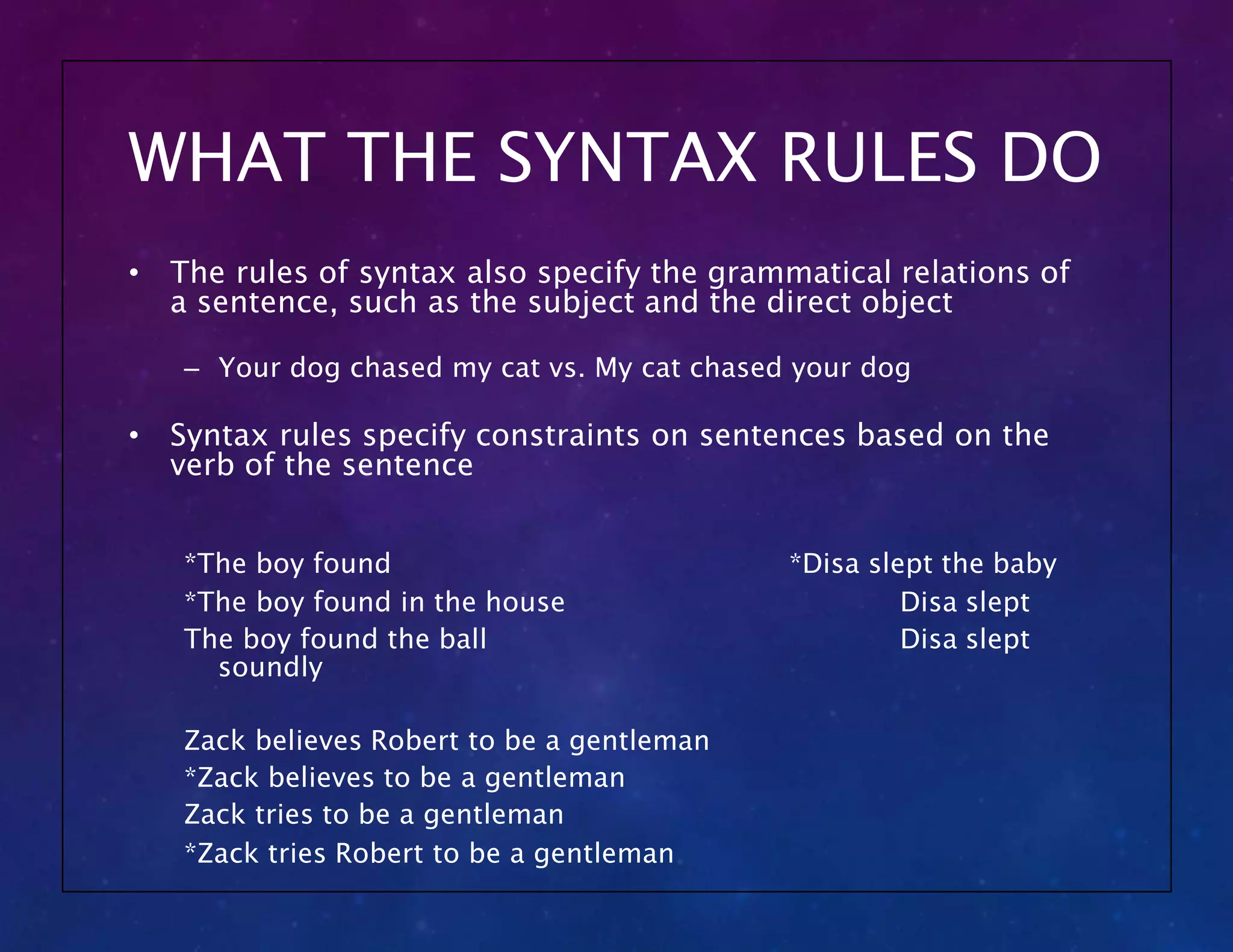

![WHAT THE SYNTAX RULES DO

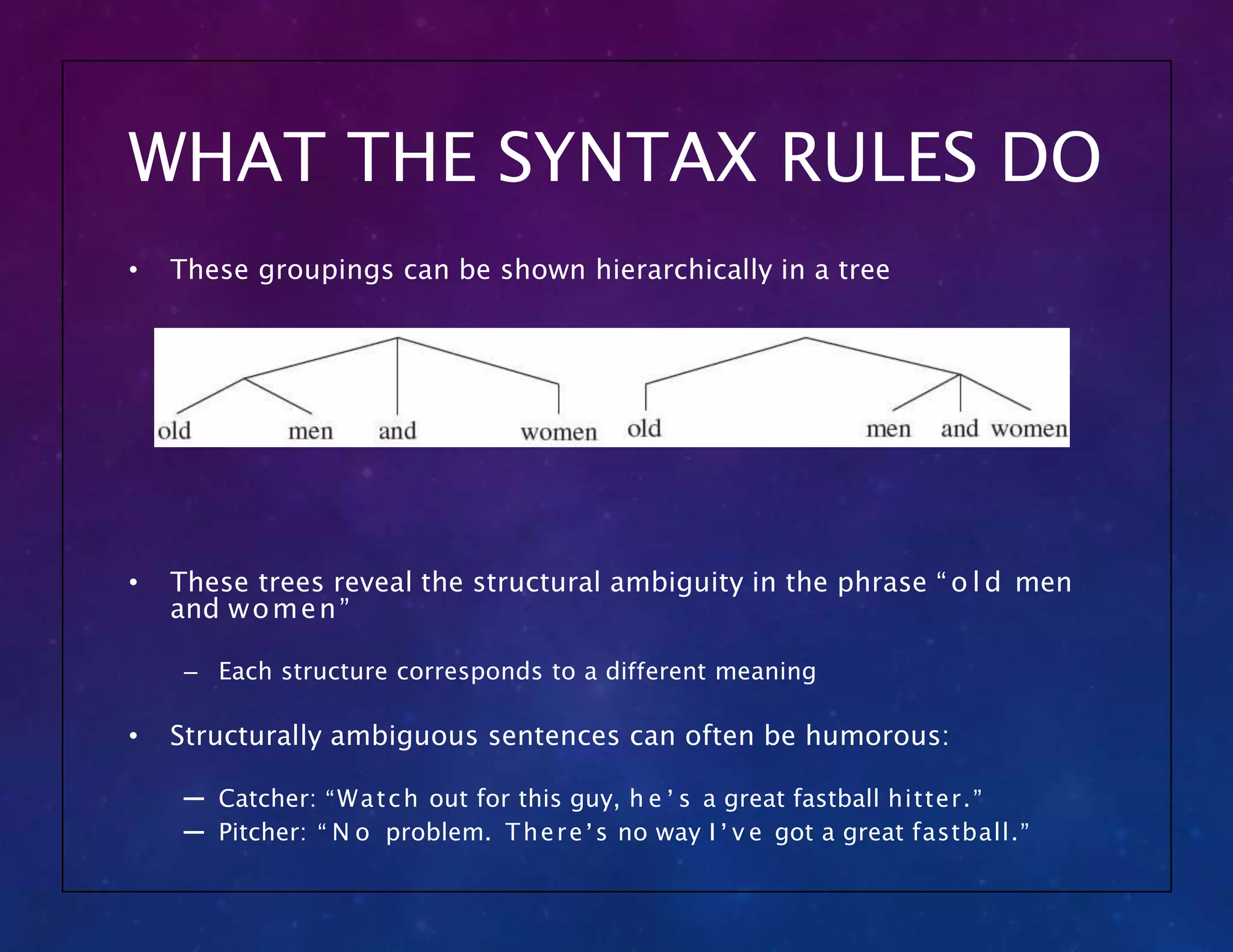

• Syntax rules also tell us how words form groups and are

hierarchically ordered in a sentence

“ T h e captain ordered the old men and women off the ship”

• This sentence has two possible meanings:

– 1. The captain ordered the old men and the old women off the ship

– 2. The captain ordered the old men and the women of any age off the

ship

• The meanings depend on how the words in the sentence are

grouped (specifically, to which words is the adjective ‘ o l d ’

applied?)

– 1. The captain ordered the [old [men and women]] off the ship

– 2. The captain ordered the [old men] and [women] off the ship](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/syntax-230606095533-4492648d/75/syntax-ppt-pptx-6-2048.jpg)

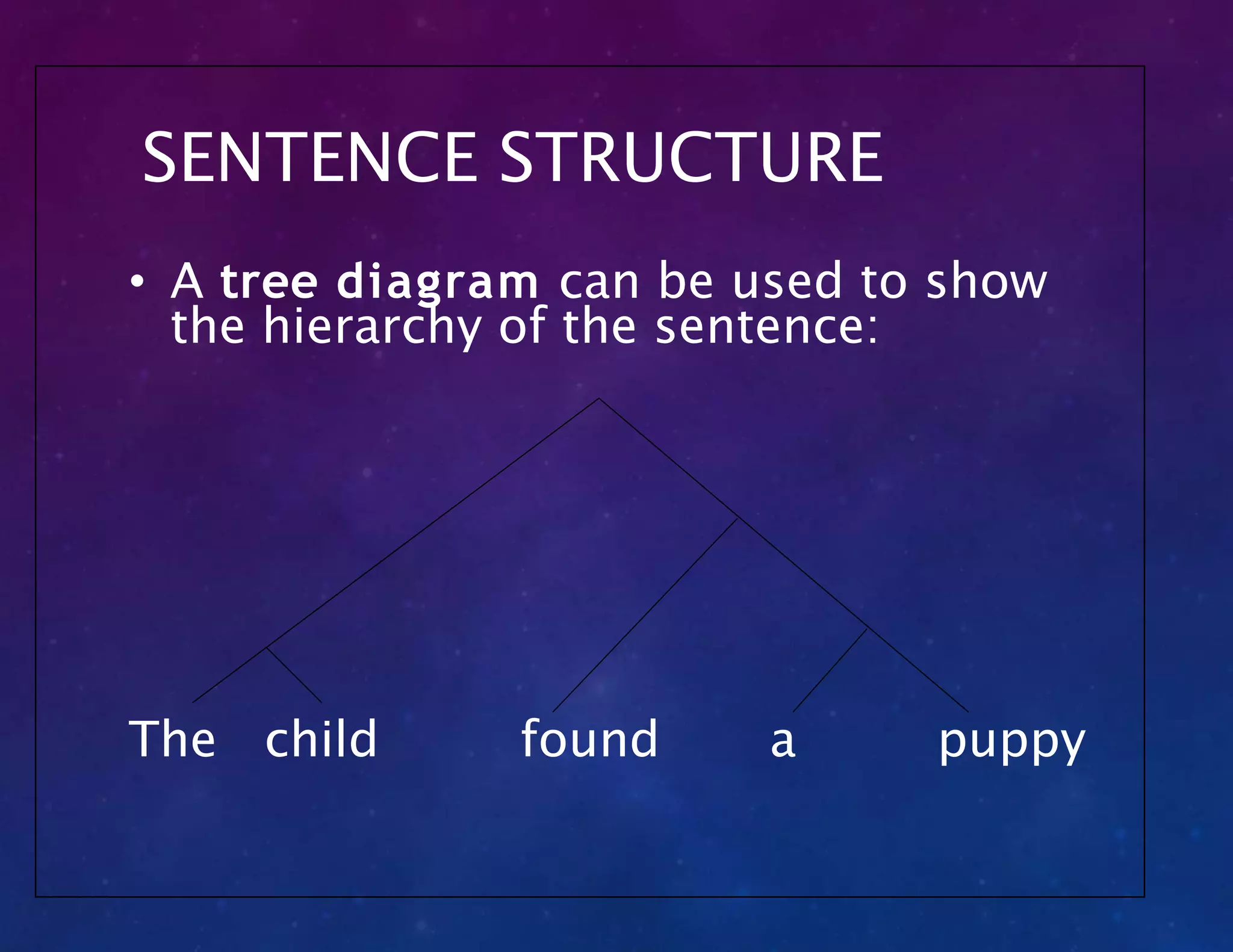

![SENTENCE STRUCTURE

• We could say that the sentence “ T h e child

found the puppy” is based on the

template:

Det—N—V—Det—N

– But this would imply that sentences are just

strings of words without internal structure

– This sentence can actually be separated into

several groups:

• [the child] [found a puppy]

• [the child] [found [a puppy]]

• [[the] [child]] [[found] [[a] [puppy]]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/syntax-230606095533-4492648d/75/syntax-ppt-pptx-9-2048.jpg)