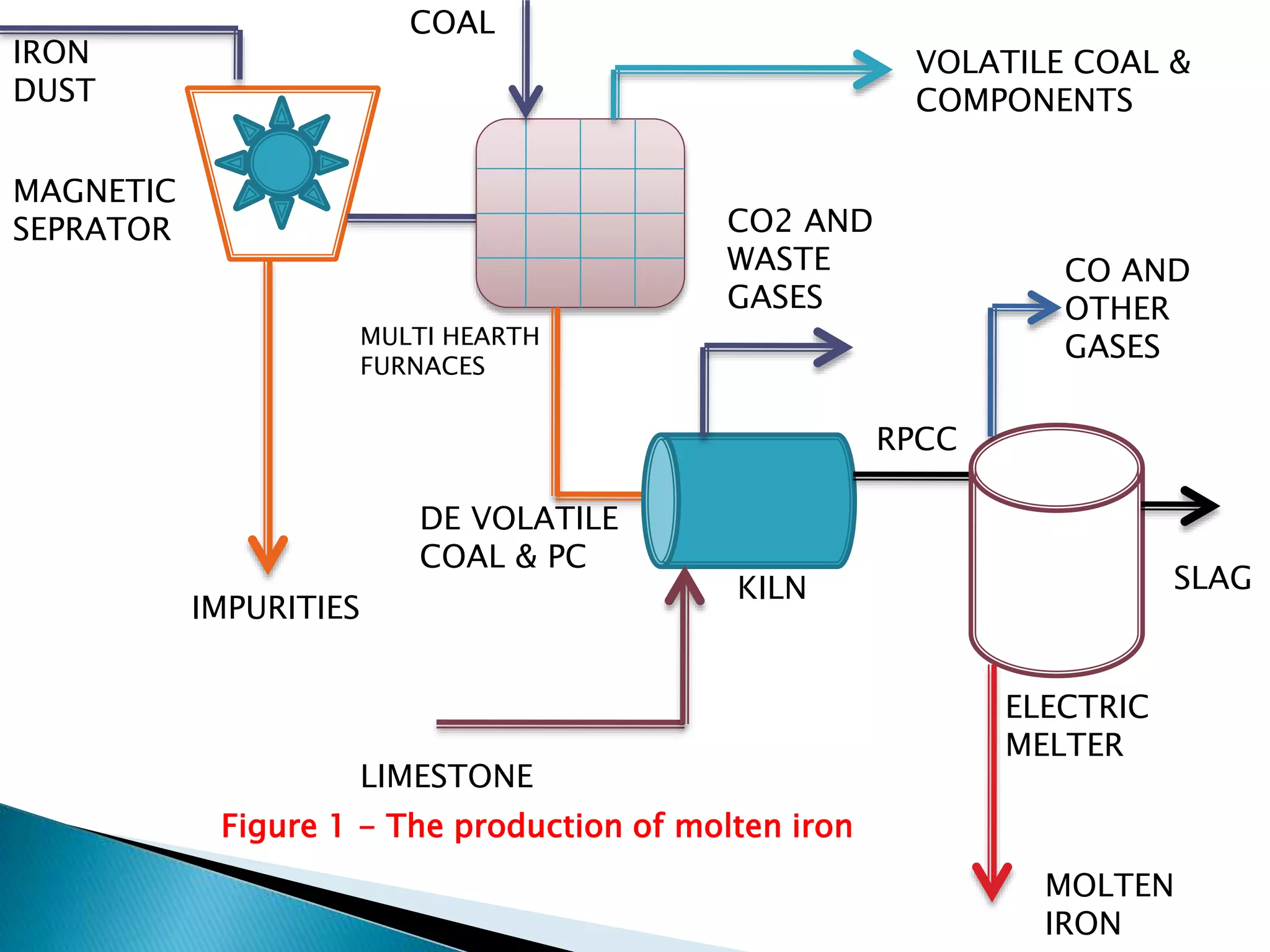

The document summarizes the process of converting iron ore into steel. It involves two main steps:

1. Production of molten iron from iron oxides through reduction in rotary kilns using carbon monoxide produced from coal and limestone. This yields a product called RPCC that is around 70% metallic iron.

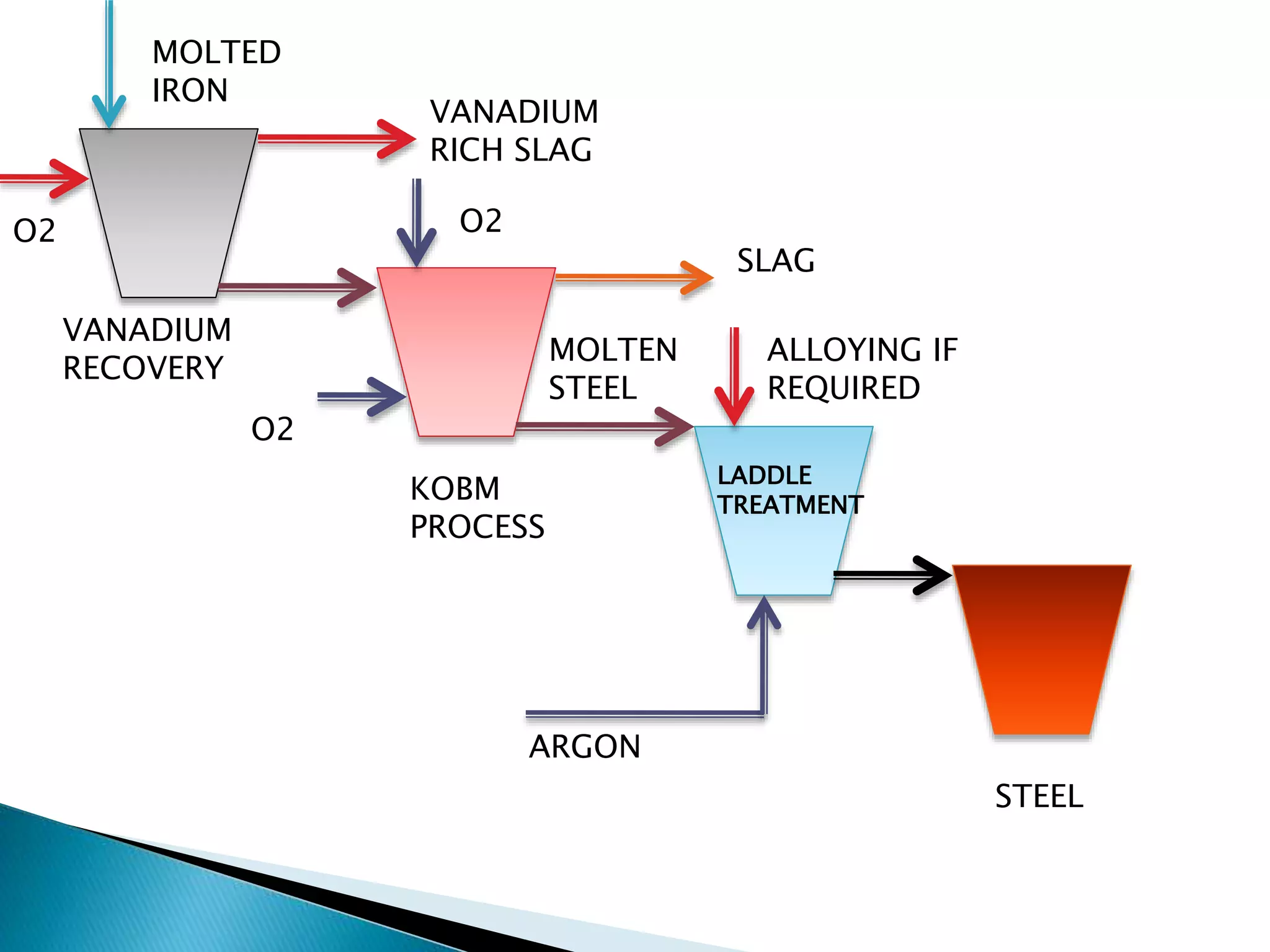

2. Steel making which involves removing impurities from the molten iron through oxidation and producing molten steel. Key processes include vanadium recovery, using oxygen to create slag and stirring the metal, and the KOBM process to blow oxygen and further purify the molten iron into steel.