Signal Processing and Optimization for Transceiver Systems 1st Edition P. P. Vaidyanathan

Signal Processing and Optimization for Transceiver Systems 1st Edition P. P. Vaidyanathan

Signal Processing and Optimization for Transceiver Systems 1st Edition P. P. Vaidyanathan

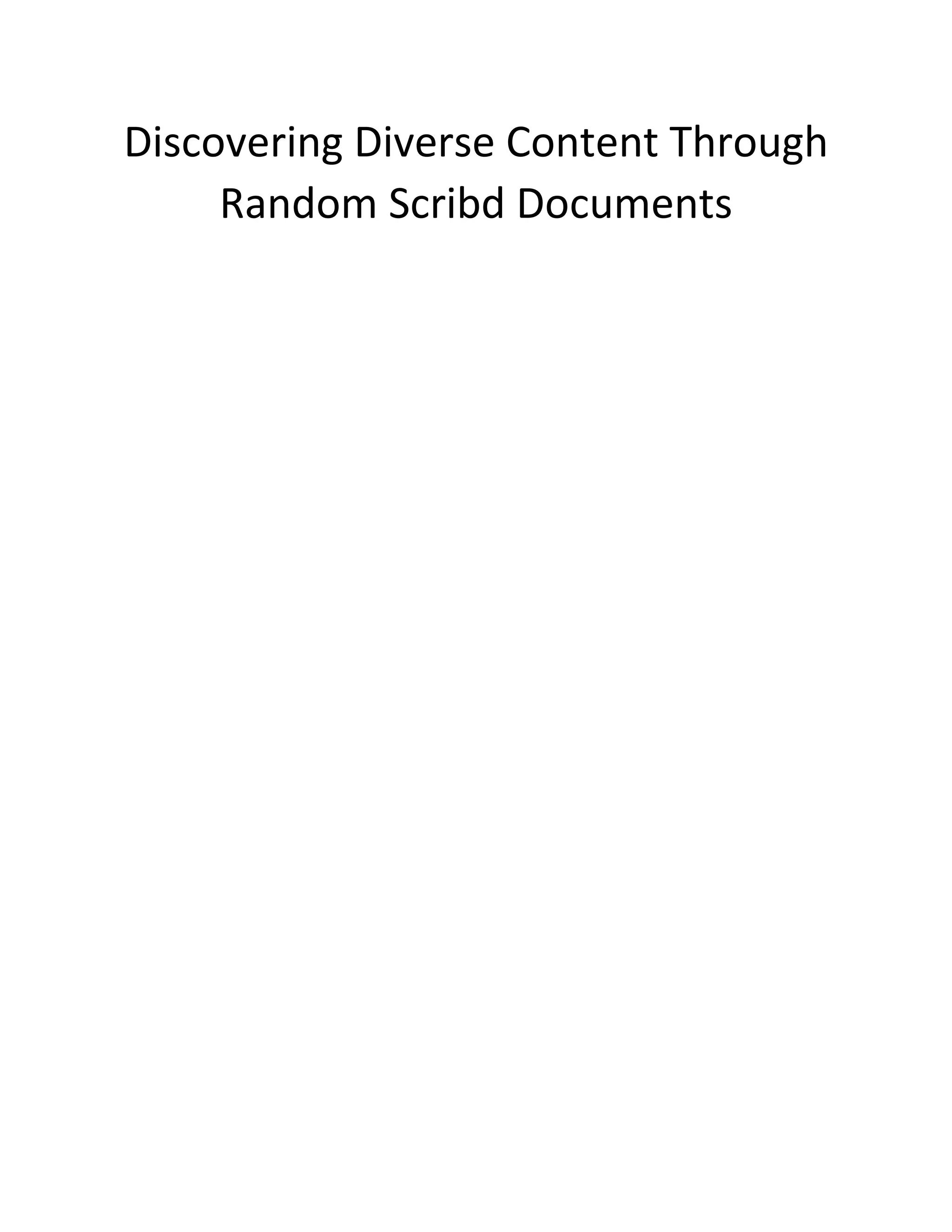

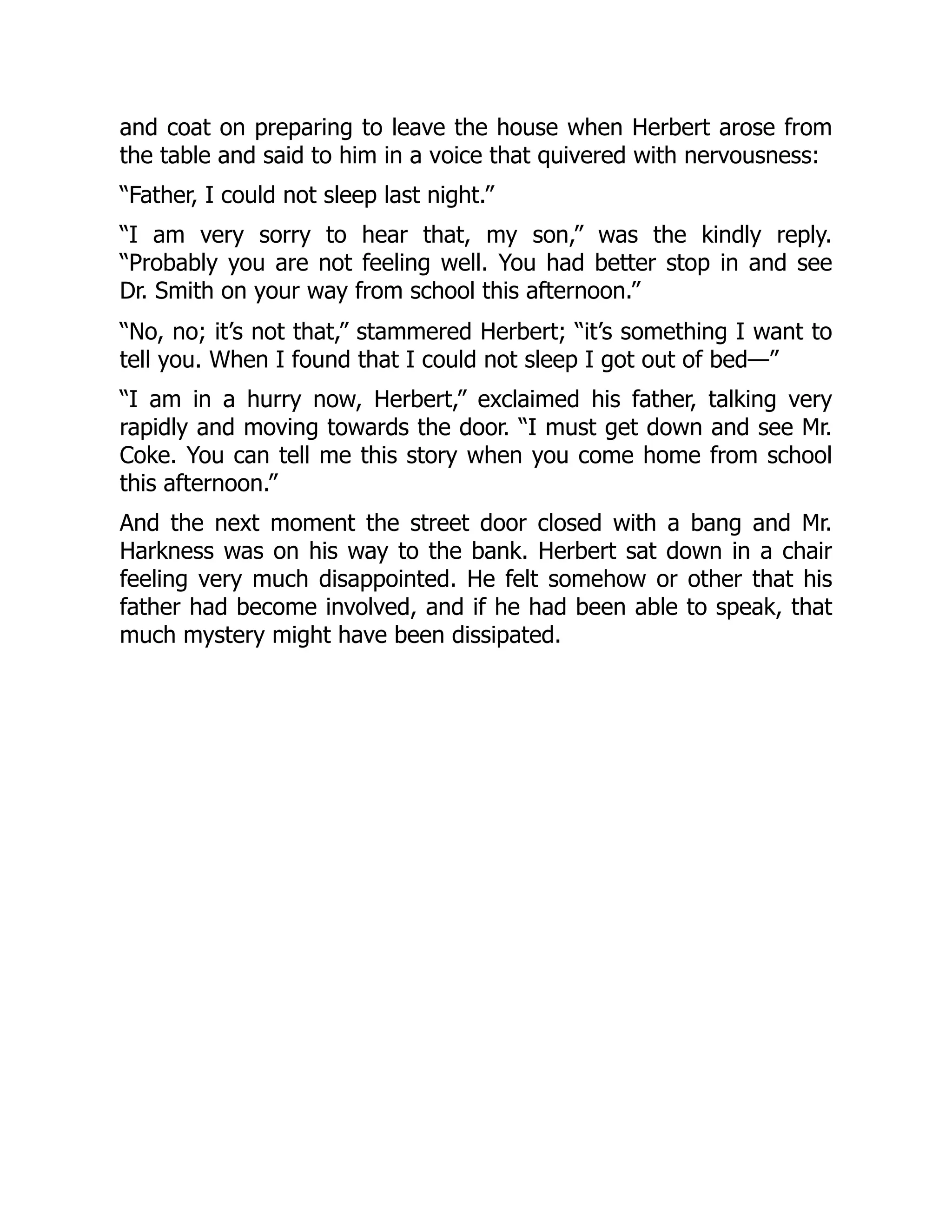

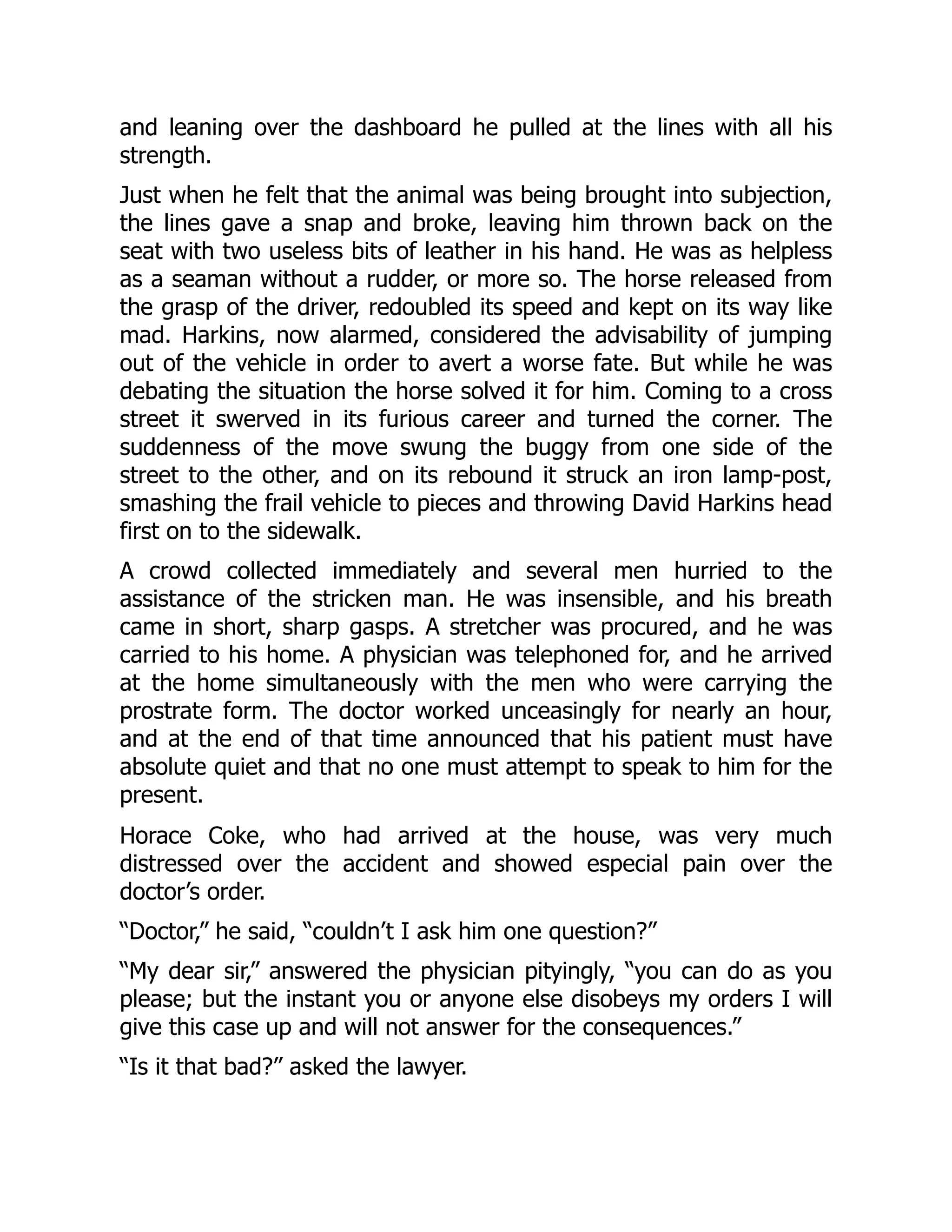

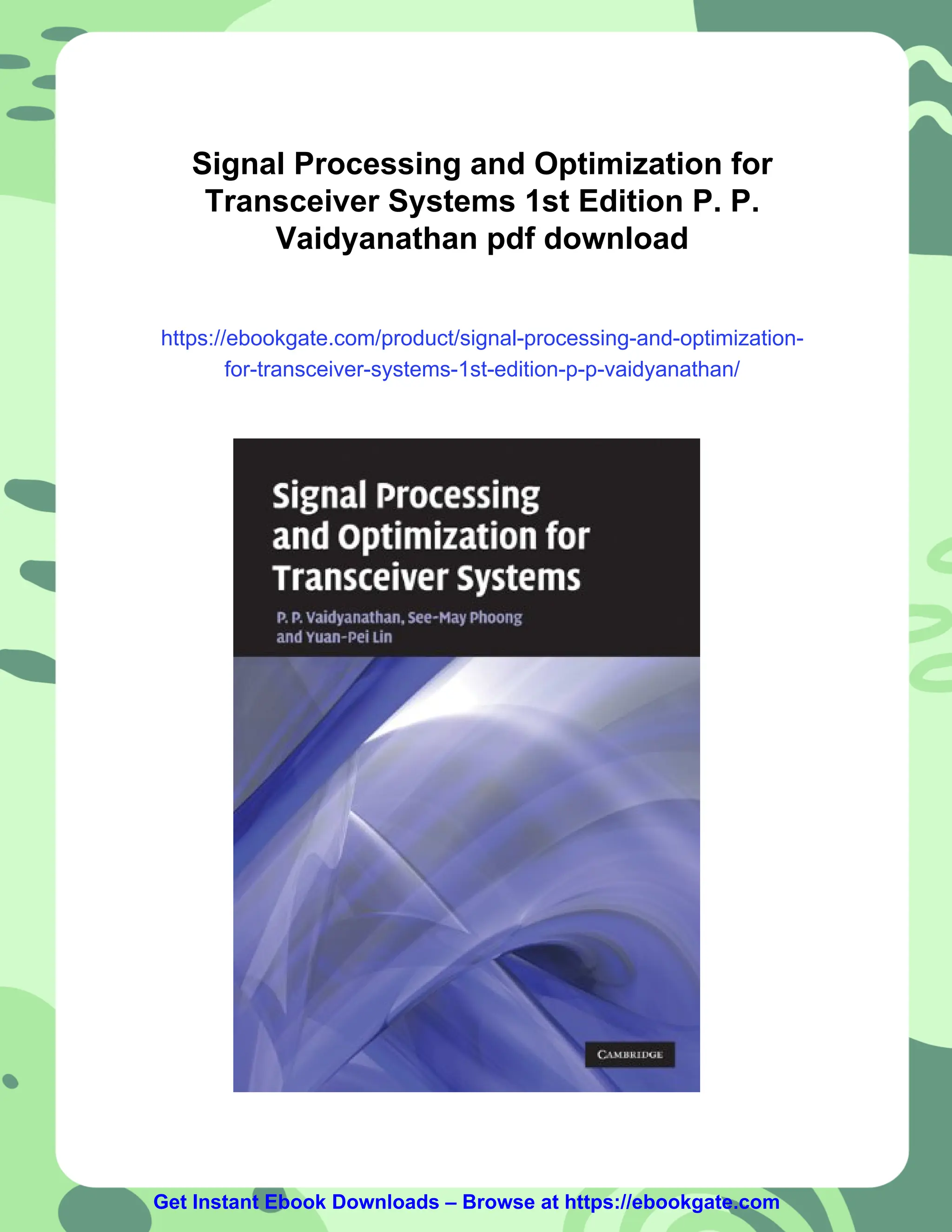

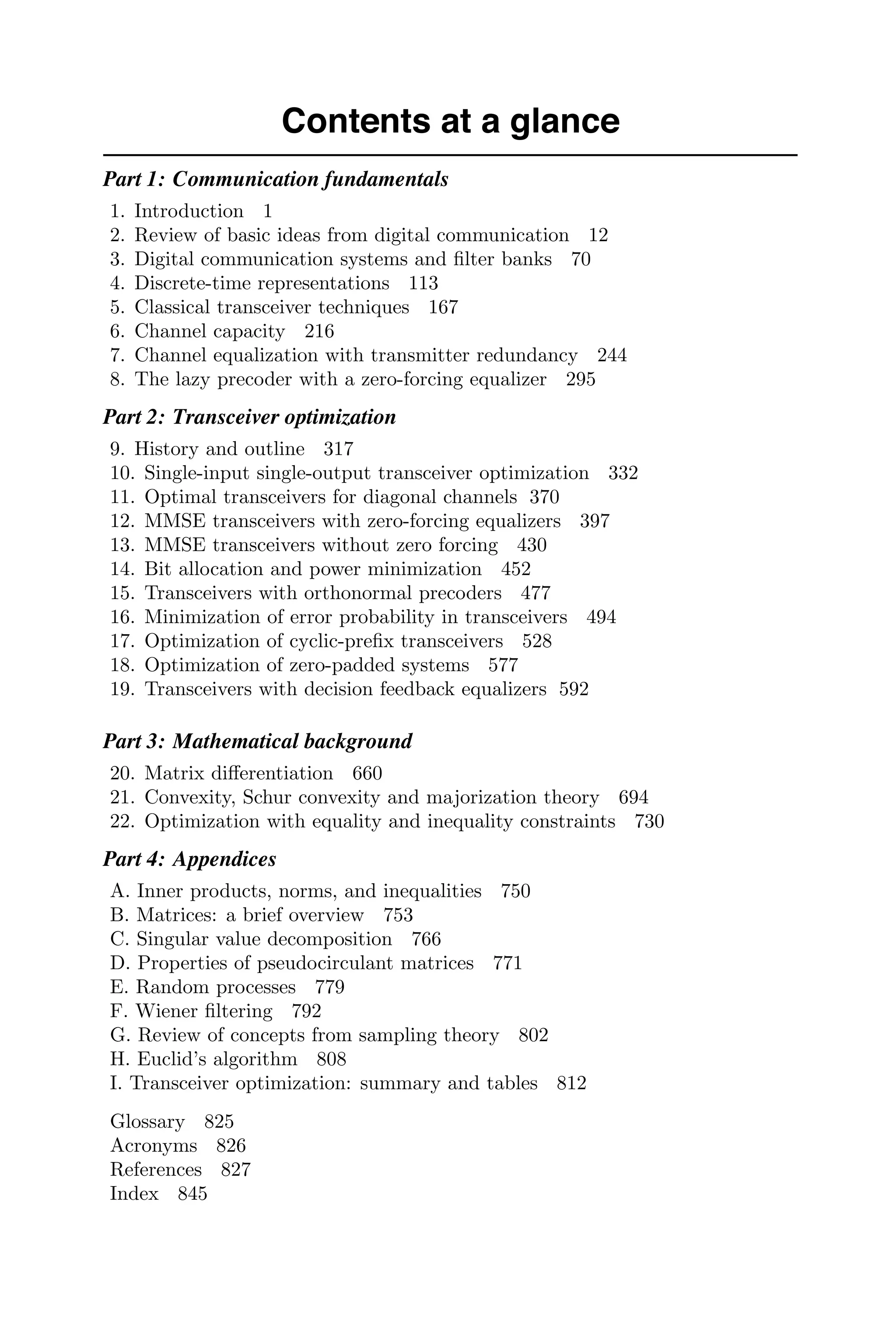

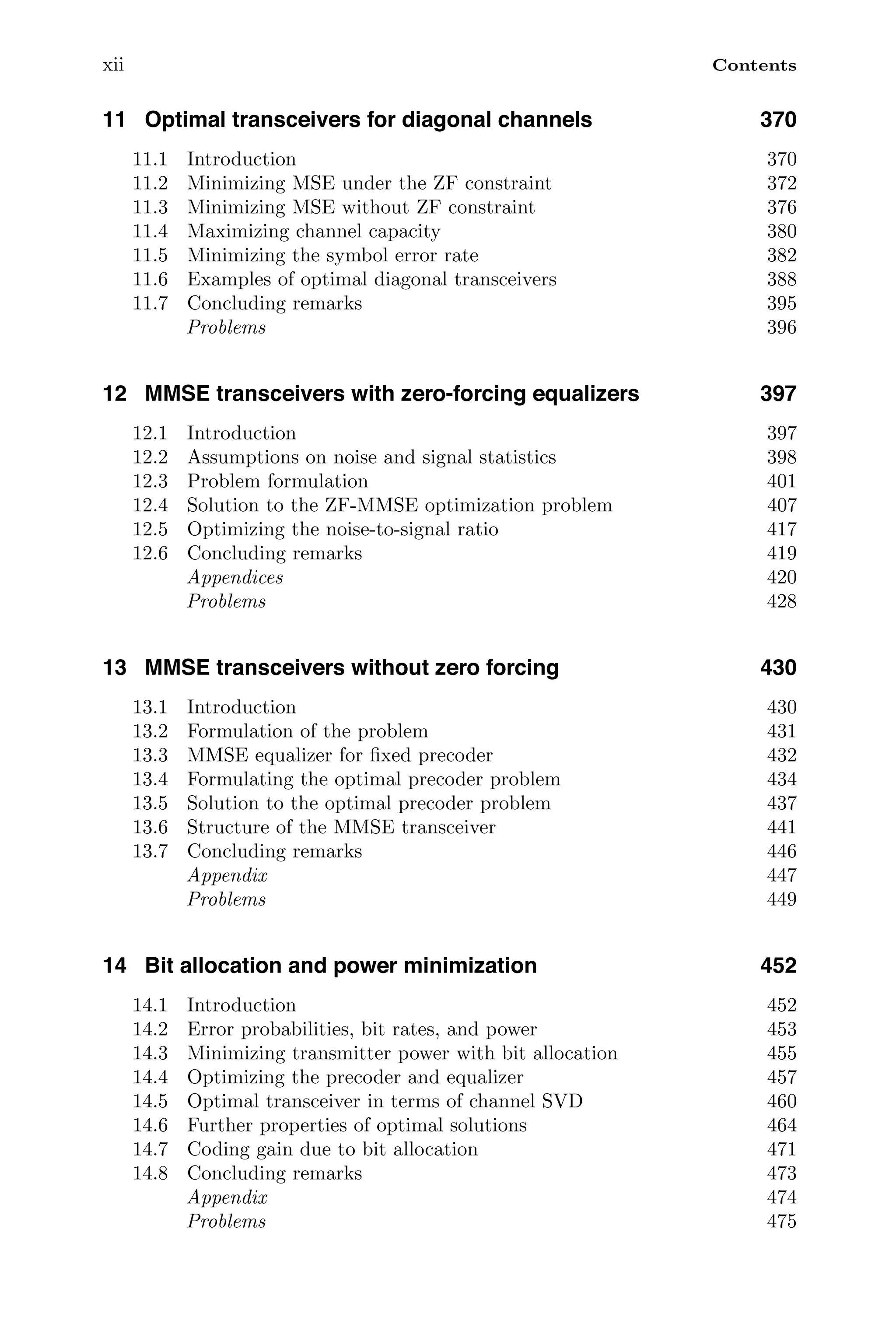

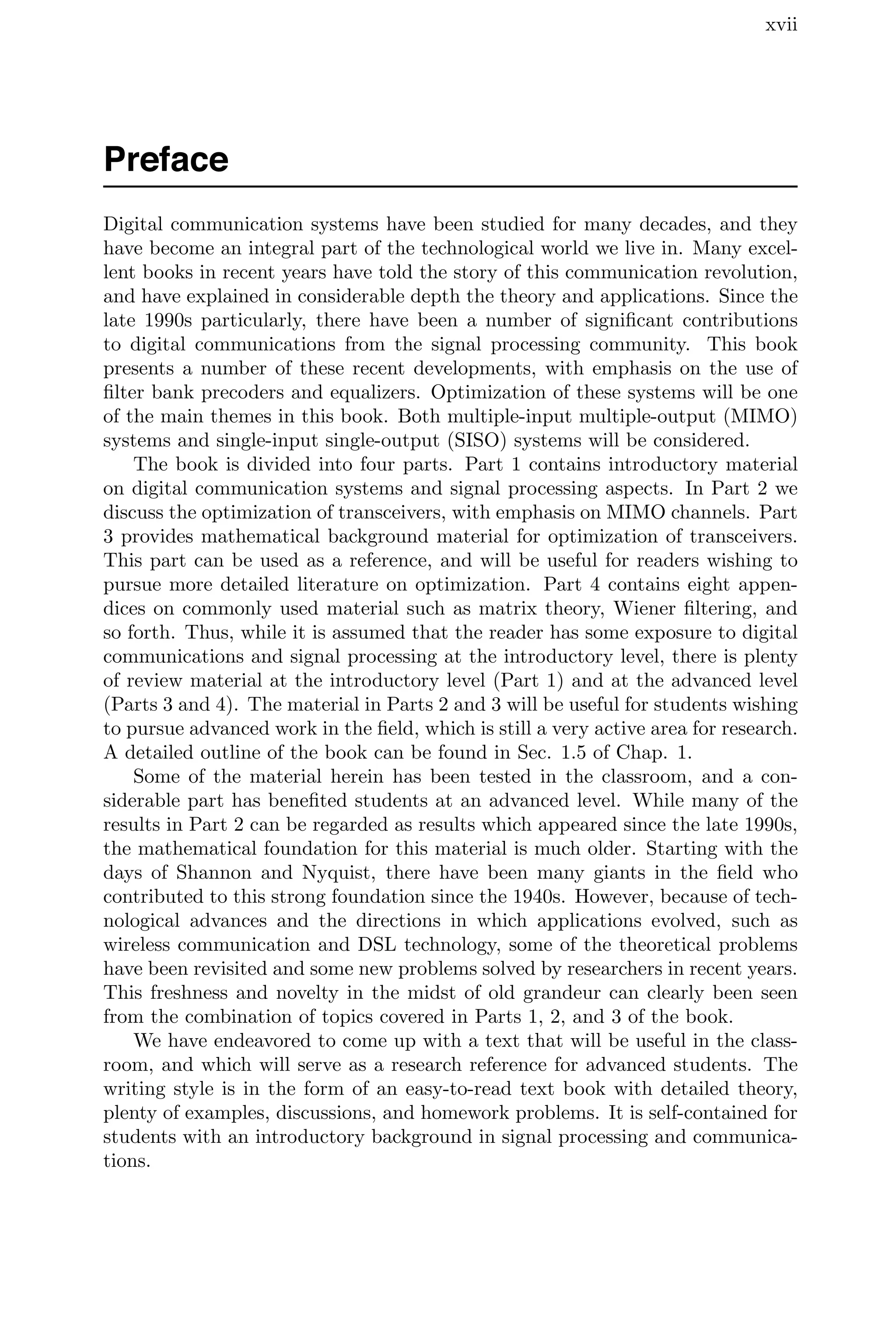

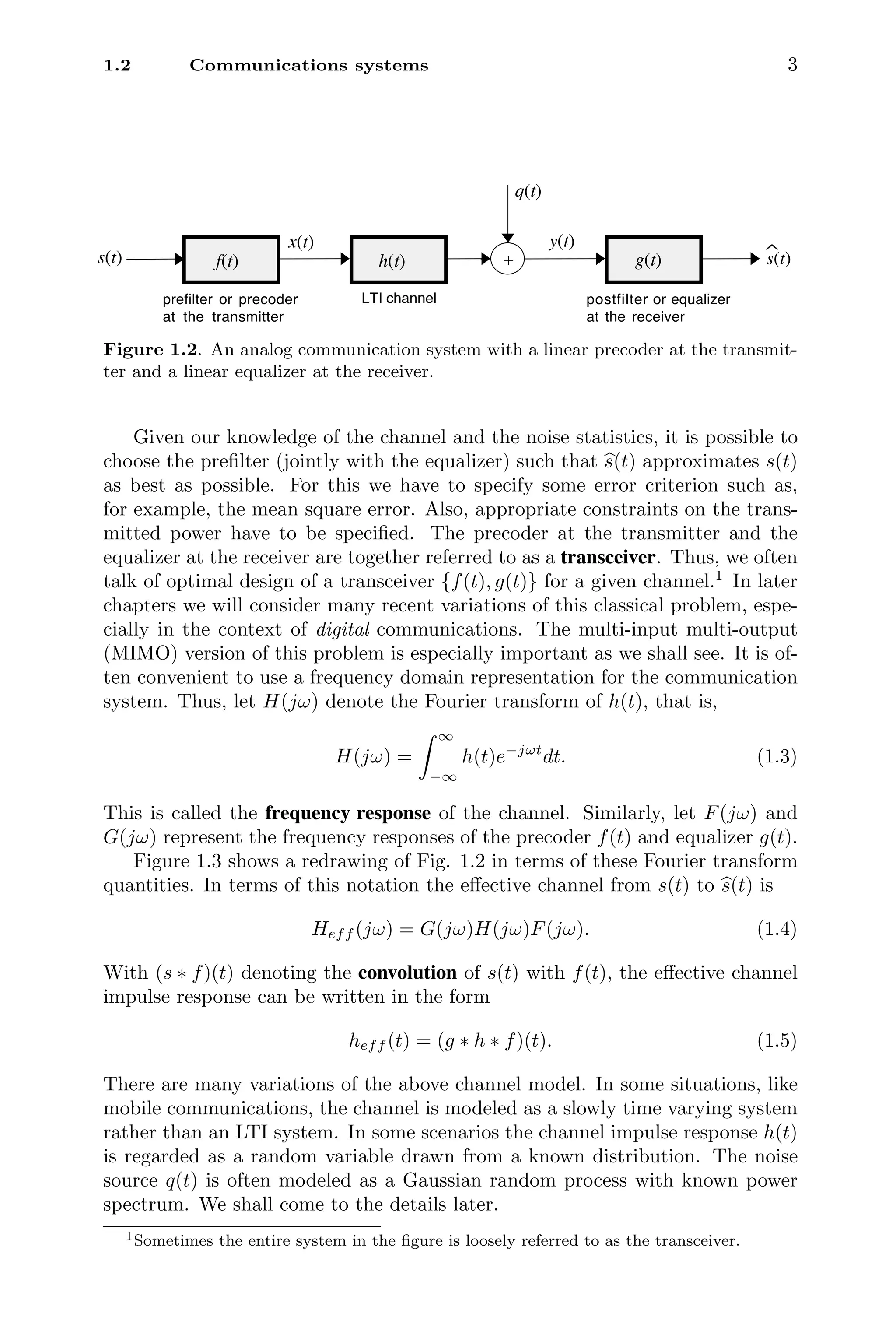

![4 Introduction

prefilter or precoder postfilter or equalizer

F(jω)

s(t)

q(t)

s(t)

G(jω)

+

y(t)

LTI channel

H(jω)

x(t)

Figure 1.3. The analog communication system represented in terms of frequency

responses.

1.3 Digitial communication systems

In the preceding section, the signal s(t) was regarded as a continuous time signal

with continuous (unquantized) amplitude. In a digital communication system,

the messages are quantized amplitudes, transmitted in discrete time. Figure 1.4

shows the schematic of a digital communication system. Here we have a discrete-

time message or signal s(n) which we wish to transmit over a continuous-time

channel. The amplitudes of s(n) are “digitized,” that is they come from a finite

set of symbols. This collection of symbols is called a constellation. We shall

come to details of digitization later.2

Since s(n) is a discrete-time signal and the

channel is continuous-time, the signal is first converted into a continuous-time

signal x(t) as indicated in the figure.

The conversion from s(n) to x(t) can be described schematically in two steps.

The building block indicated as D/C is a discrete-to-continuous-time converter,

and it converts s(n) to a signal sc(t) given by

sc(t) =

∞

n=−∞

s(n)δc(t − nT). (1.6)

Here δc(t) is the impulse or Dirac delta function [Oppenheim and Willsky, 1997].

Thus, the sample s(n) is converted into an impulse positioned at time nT. The

sample spacing T determines the speed with which the message samples are

conveyed. Since we have 1/T symbols per second, the symbol rate is given by

fs =

1

T

Hz. (1.7)

The prefilter F(jω) at the transmitter performs a convolution to produce the

output

x(t) =

∞

n=−∞

s(n)f(t − nT), (1.8)

2Examples of constellations include PAM and QAM systems to be described in Sec. 2.2.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65604-250620202834-0ce82231/75/Signal-Processing-and-Optimization-for-Transceiver-Systems-1st-Edition-P-P-Vaidyanathan-25-2048.jpg)

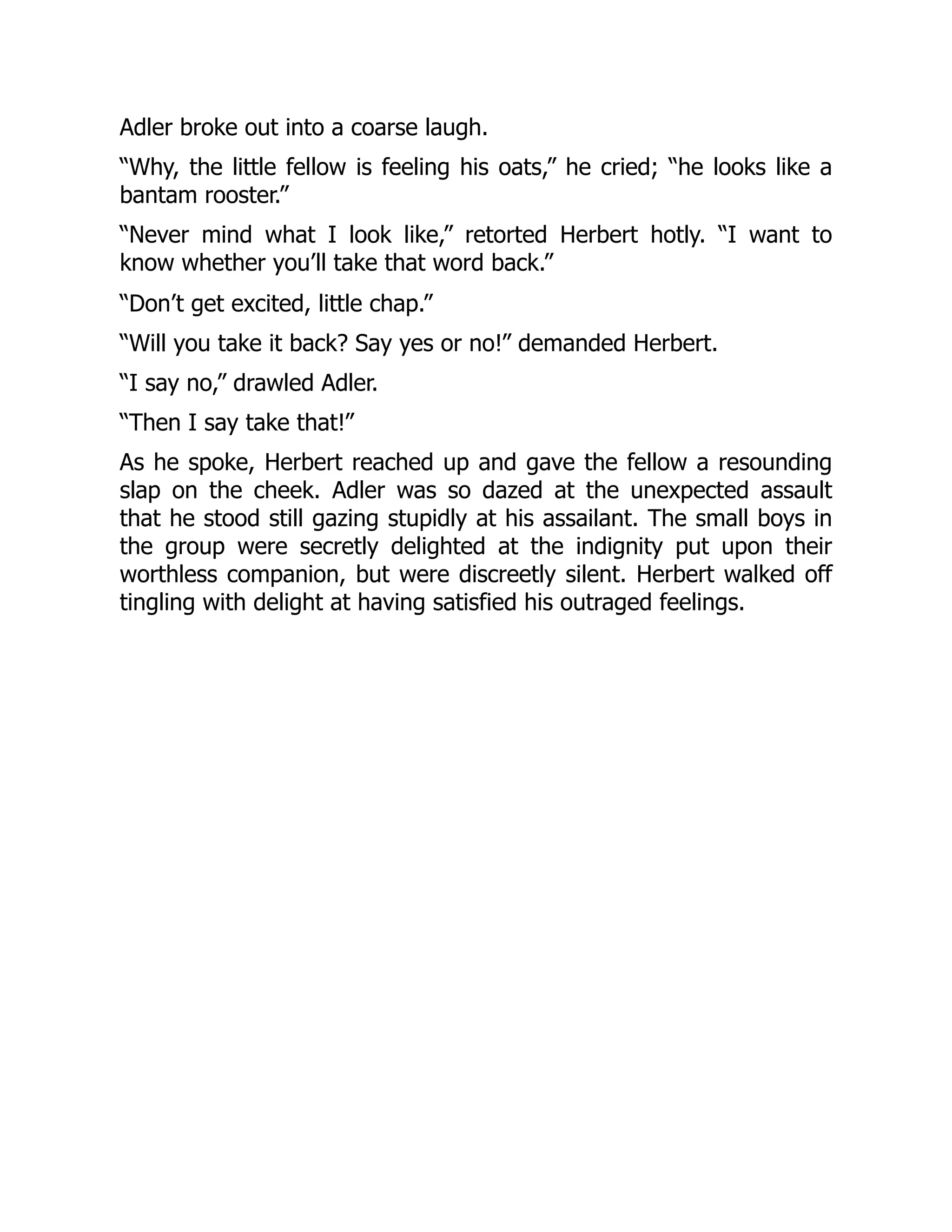

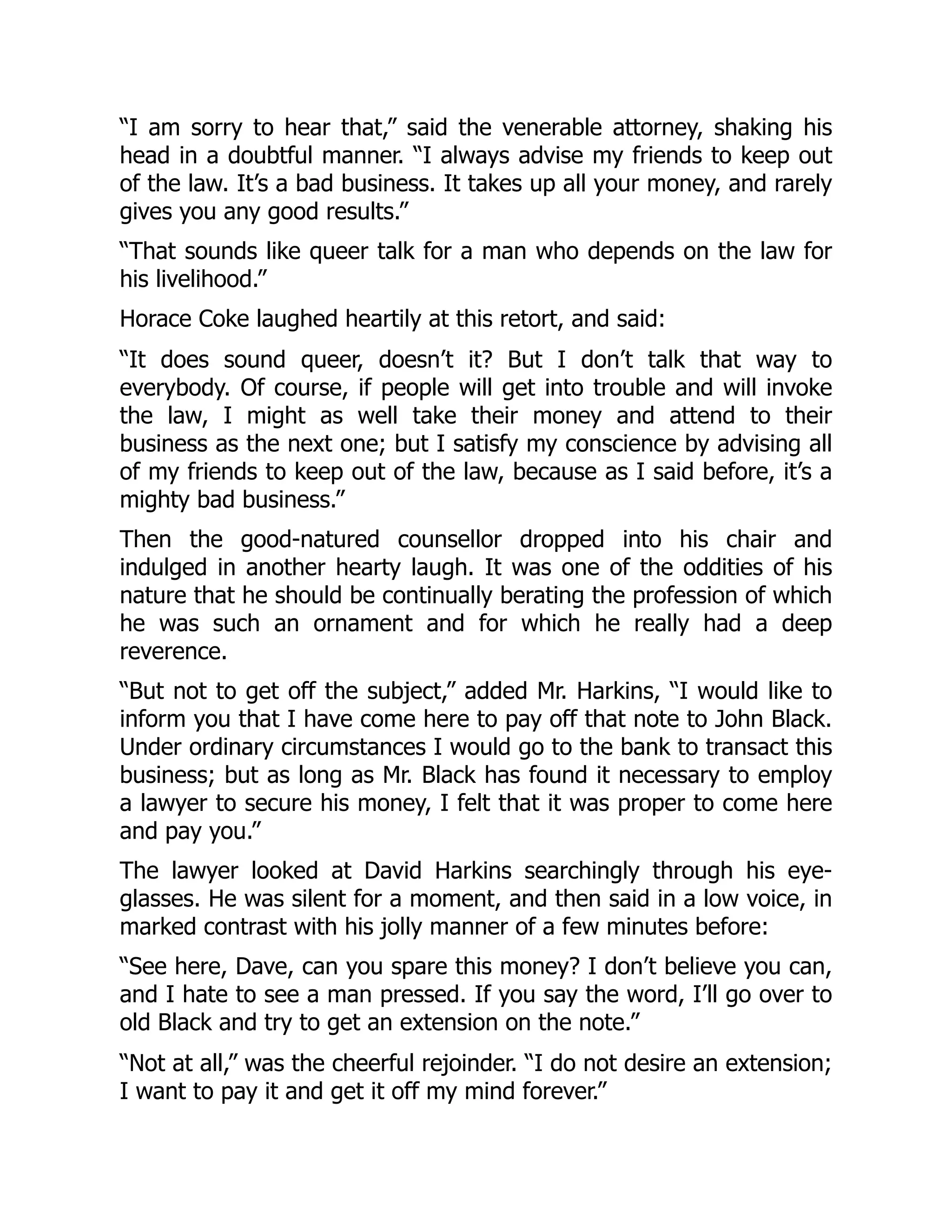

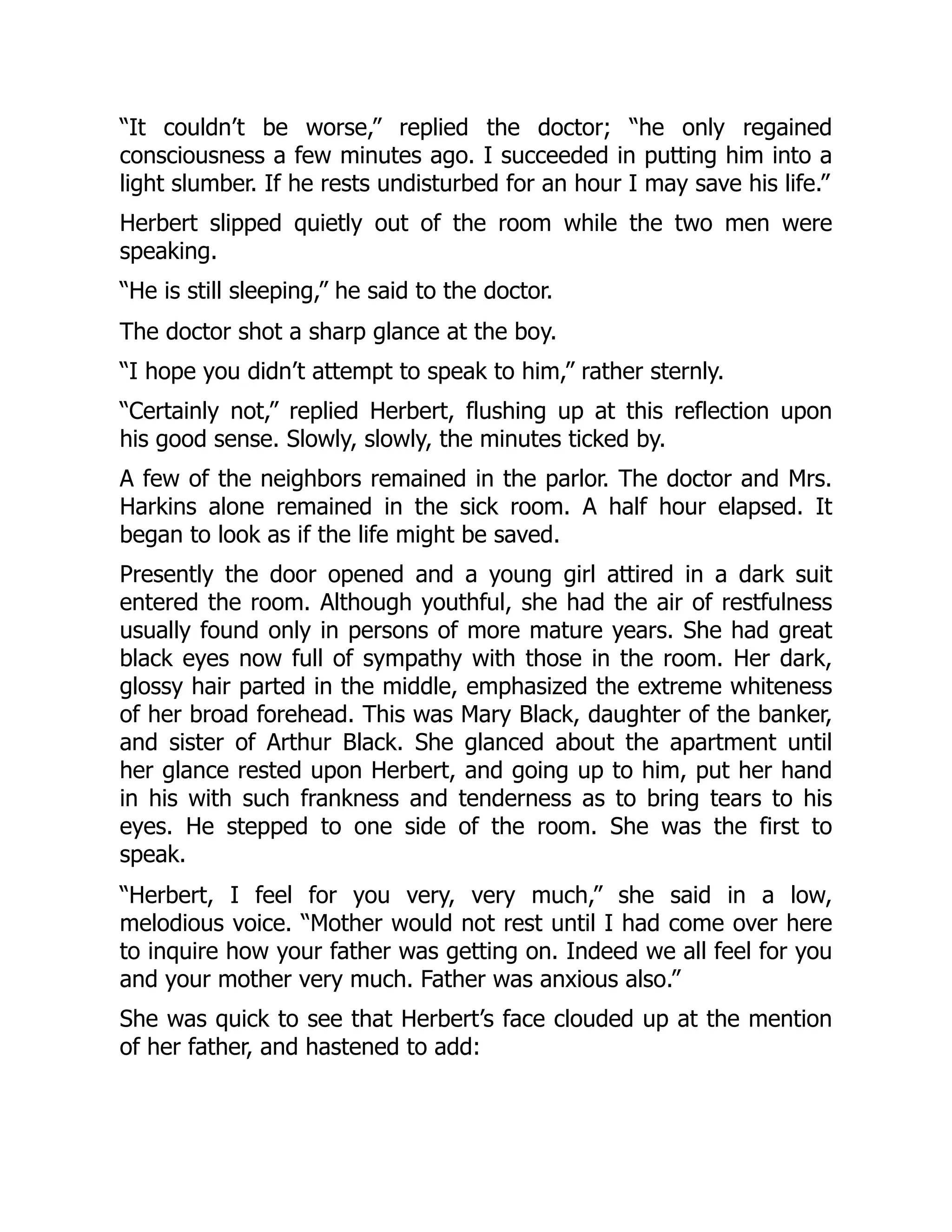

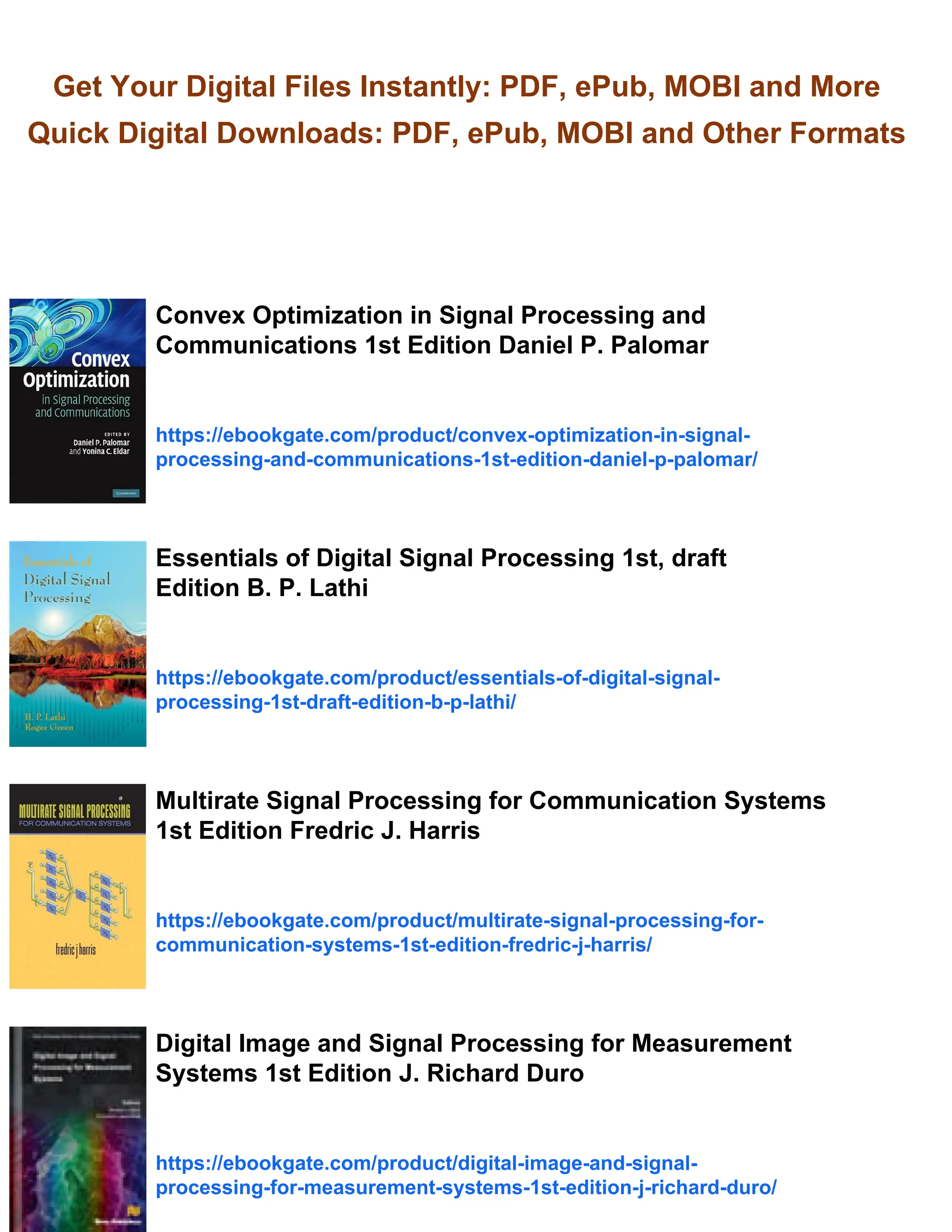

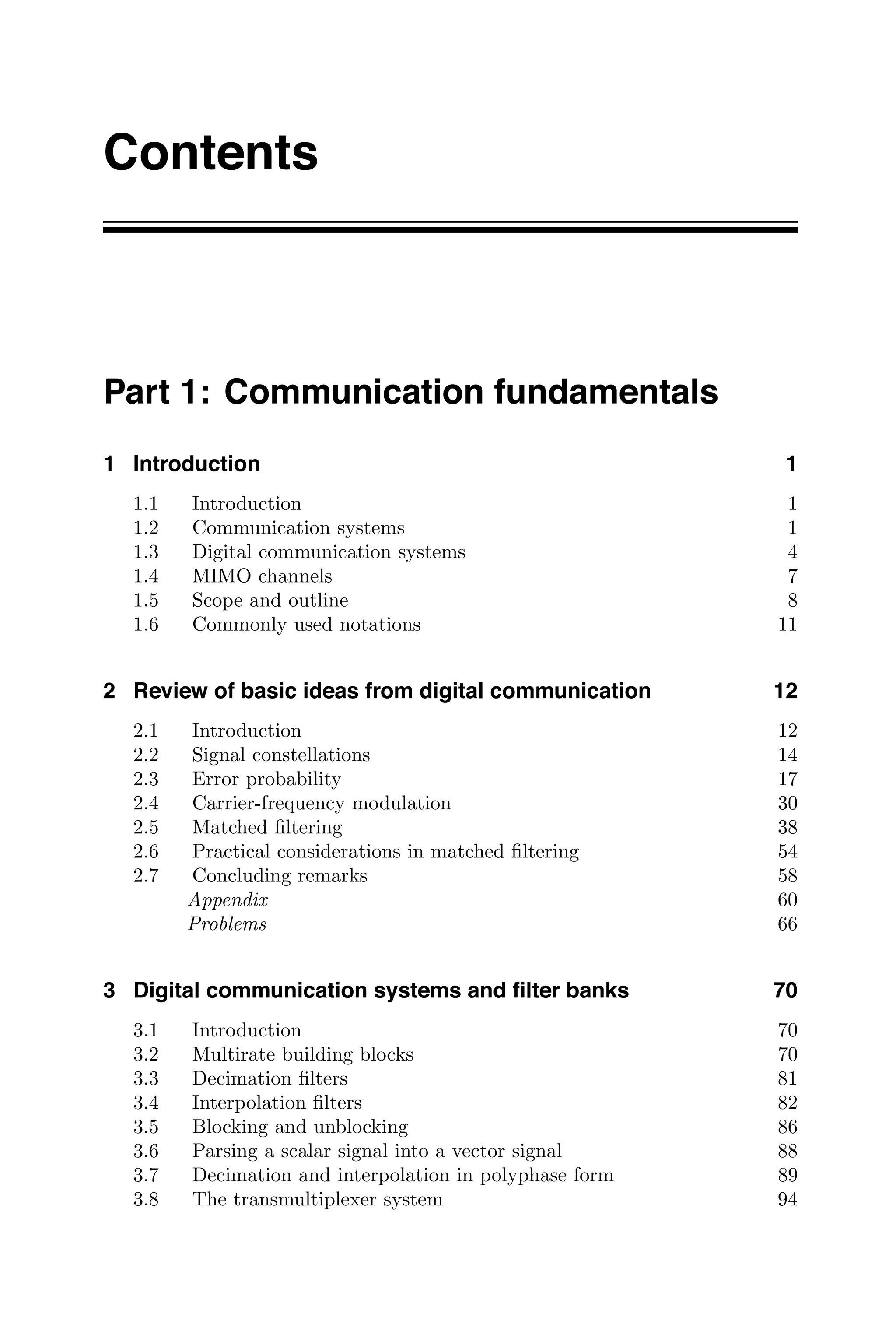

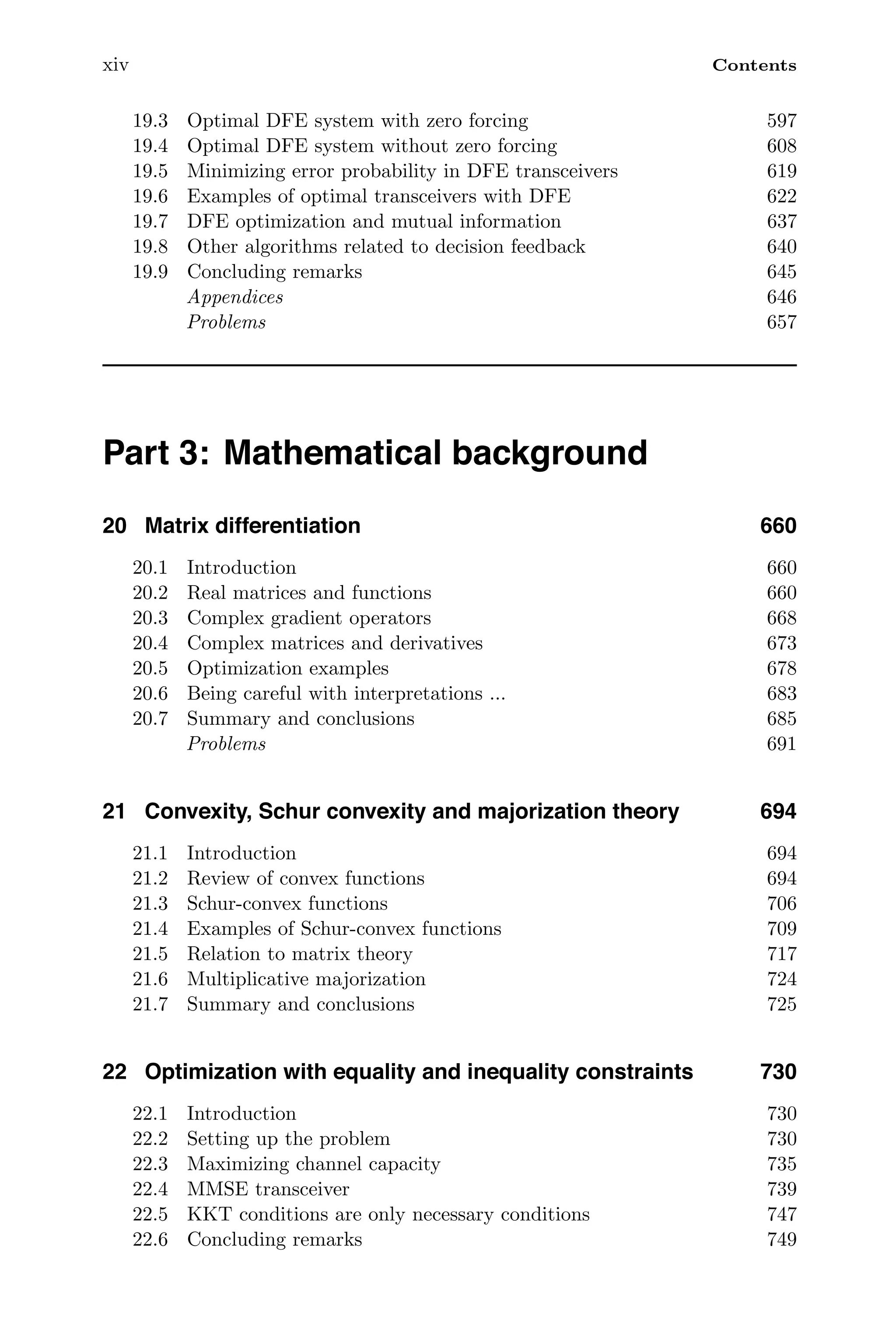

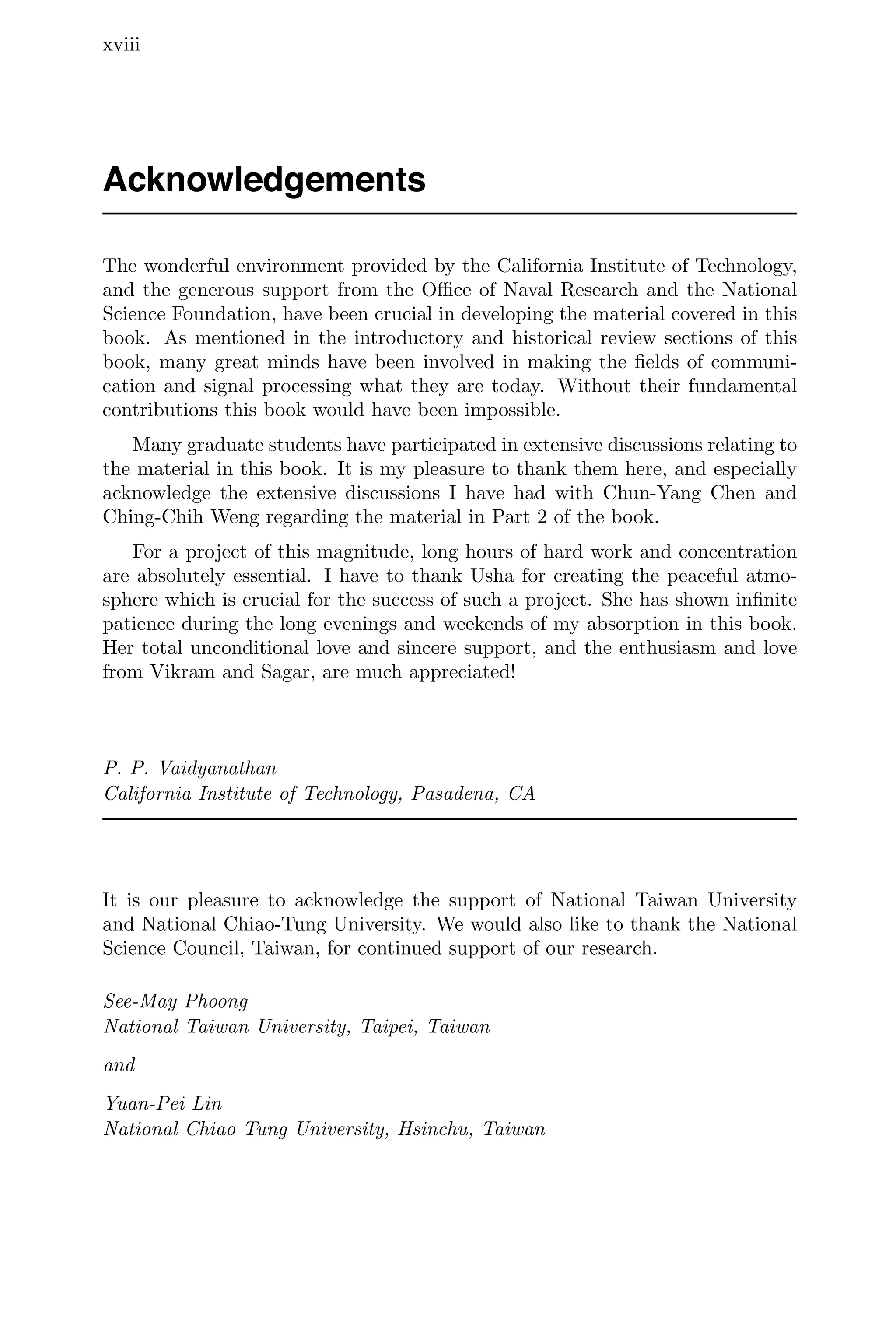

![1.4 MIMO channels 7

precoder equalizer

s(n) s(n)

+

channel

F (z)

d G (z)

d

H (z)

d

q (n)

d

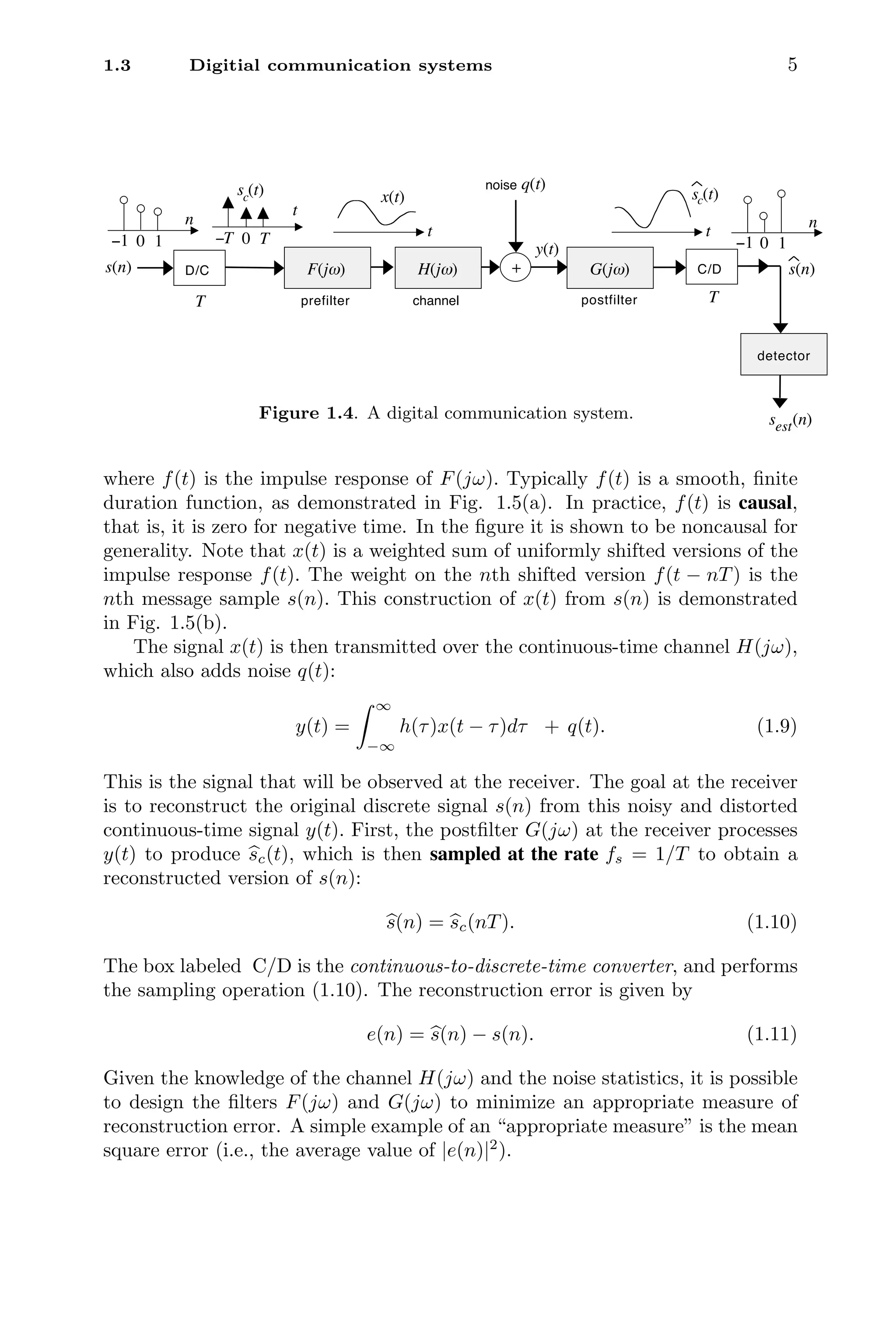

Figure 1.6. An all-discrete equivalent of the digital communication system.

Here Hd(z) is the transfer function of an equivalent discrete-time channel. It

is the z-transform of an equivalent digital channel impulse response hd(n), that

is

Hd(z) =

∞

n=−∞

hd(n)z−n

. (1.13)

Similarly, Fd(z) and Gd(z) are the transfer functions of the discrete-time pre-

coder and equalizer. The subscript d (for “discrete”), which is just for clarity,

is usually dropped. In practice Hd(z) is causal and can be approximated by a

finite impulse response, or FIR, system so that

Hd(z) =

L

n=0

hd(n)z−n

. (1.14)

The problem of optimizing the precoder Fd(z) and equalizer Gd(z) for fixed

channel Hd(z) and fixed noise statistics will be addressed in later chapters.

1.4 MIMO channels

The transceivers described so far have one input signal s(n) and a corresponding

output

s(n). These are called single-input single-output, or SISO, transceivers.

An important communication system that comes up frequently in this book is

the multi-input multi-output, or MIMO, channel. Figure 1.7 shows a MIMO

channel assumed to be linear and time-invariant with a transfer function matrix

H(z), usually an FIR system:

H(z) =

L

n=0

h(n)z−n

. (1.15)

The sequence h(n), called the MIMO impulse response, is a sequence of matrices.

If the channel has P inputs and J outputs then H(z) has size J × P, and so

does each of the matrices h(n). The MIMO communication channel is used to

transmit a vector signal s(n) with M components:

s(n) = [ s0(n) s1(n) . . . sM−1(n) ]

T

. (1.16)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65604-250620202834-0ce82231/75/Signal-Processing-and-Optimization-for-Transceiver-Systems-1st-Edition-P-P-Vaidyanathan-28-2048.jpg)

![1.5 Scope and outline 9

include Proakis [1995], Oppenheim and Willsky [1997], Oppenheim and Schafer

[1999], Lathi [1998], Haykin [2001], Mitra [2001], and Antoniou [2006], among

other excellent texts. Advanced material related to the topics in this book can

also be found in Ding and Li [2001], and Giannakis, et al. [2001]. Books on the

very important related areas of wireless and multiuser communications include

Rappaport [1996], Verdu [1998], Goldsmith [2005], Haykin and Moher [2005],

and Tse and Viswanath [2005].

The book is divided into four parts. Part 1 contains introductory material

on digital communication systems and signal processing aspects. In part 2 we

discuss the optimization of transceivers, with emphasis on MIMO channels. Part

3 provides mathematical background material for optimization of transceivers.

This part can be used as a reference, and will be very useful for readers wishing

to pursue more detailed literature on optimization. Part 4 contains eight appen-

dices on commonly used material such as matrix theory, Wiener filtering, and

so forth.

The history of digital communication theory is fascinating. It is a humbling

experience to look back and reflect on the tremendous insights and accomplish-

ments of the communications and signal processing society in the last six decades.

Needless to say, much of the recent research is built upon six to seven decades of

this solid foundation. A detour into history will be provided in Chap. 9, where

we present a historical perspective of transceiver design, equalization, and opti-

mization, all of which originated in the early 1960s, and have continued to this

day to be research topics. All references to literature will be given in the specific

chapters as appropriate. An extensive reference list is given at the end of the

book. In what follows we briefly describe the four parts of the book.

Part 1: Communication fundamentals

Part 1 consists of Chapters 1 to 8. In Chap. 2 we review basic topics in digital

communication systems, such as signal constellations, carrier modulation, and

so forth. Formulas for probabilities of error in symbol detection are derived.

Matched filtering, which is used in some receiver systems, is discussed in some

detail. In Chap. 3 we describe digital communication systems using the language

of multirate filter banks. Such a representation is very useful for transceivers with

or without redundancy, and has many applications as we shall see throughout

the book.

In Chap. 4 we describe digital communication systems using discrete-time

language. This chapter also introduces symbol spaced equalizers (SSE) and

fractionally spaced equalizers (FSE). The minimum mean square error (MMSE)

equalizer is also introduced in this chapter. Chapter 5 discusses a number of fun-

damental techniques that are commonly used in digital communications. First

a detailed discussion of the matched filter is provided. Then we discuss opti-

mal sequence estimators, such as the maximum likelihood (ML) detector and

the Viterbi alogrithm. Nonlinear methods, such as the decision feedback equal-

izer and nonlinear precoders, are introduced. Chapter 6 is a brief discussion of

channel capacity with emphasis on MIMO channels.

Chapter 7 introduces redundant precoders, including zero-padded and cyclic-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65604-250620202834-0ce82231/75/Signal-Processing-and-Optimization-for-Transceiver-Systems-1st-Edition-P-P-Vaidyanathan-30-2048.jpg)

![2

Review of basic ideas

from digital communication

2.1 Introduction

In this chapter we briefly review introductory material from the theory and

practice of digital communication. The reader familiar with such introductory

material can use this chapter primarily as a reference for later chapters. For

a more detailed treatement one should consult standard communication texts

such as Proakis [1995], Lathi [1998], or Haykin [2001].

2.1.1 Chapter overview

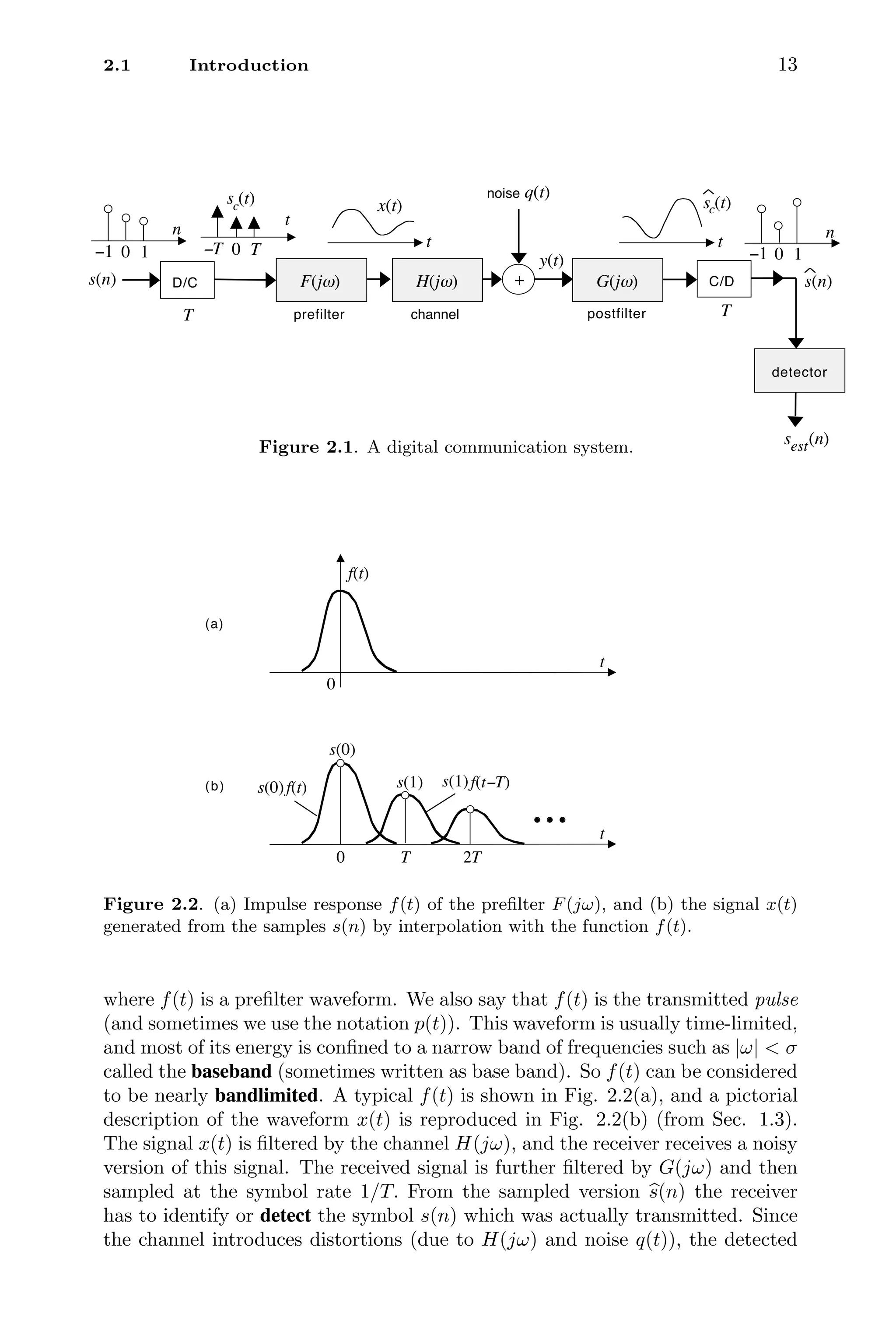

The schematic representation of digital communication systems described earlier

in Sec. 1.3 is reproduced in Fig. 2.1. As mentioned in that section, the input

symbol stream has sample values s(n) chosen from a finite set of values called the

symbol alphabet, constellation, or code words – we shall consistently use the term

constellation. In Sec. 2.2 we shall describe two commonly used constellations

called the PAM (pulse amplitude modulation) and the QAM (quadrature PAM)

constellations.

Given the symbol stream s(n) the transmitter generates the baseband wave-

form

x(t) =

∞

n=−∞

s(n)f(t − nT),

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65604-250620202834-0ce82231/75/Signal-Processing-and-Optimization-for-Transceiver-Systems-1st-Edition-P-P-Vaidyanathan-33-2048.jpg)

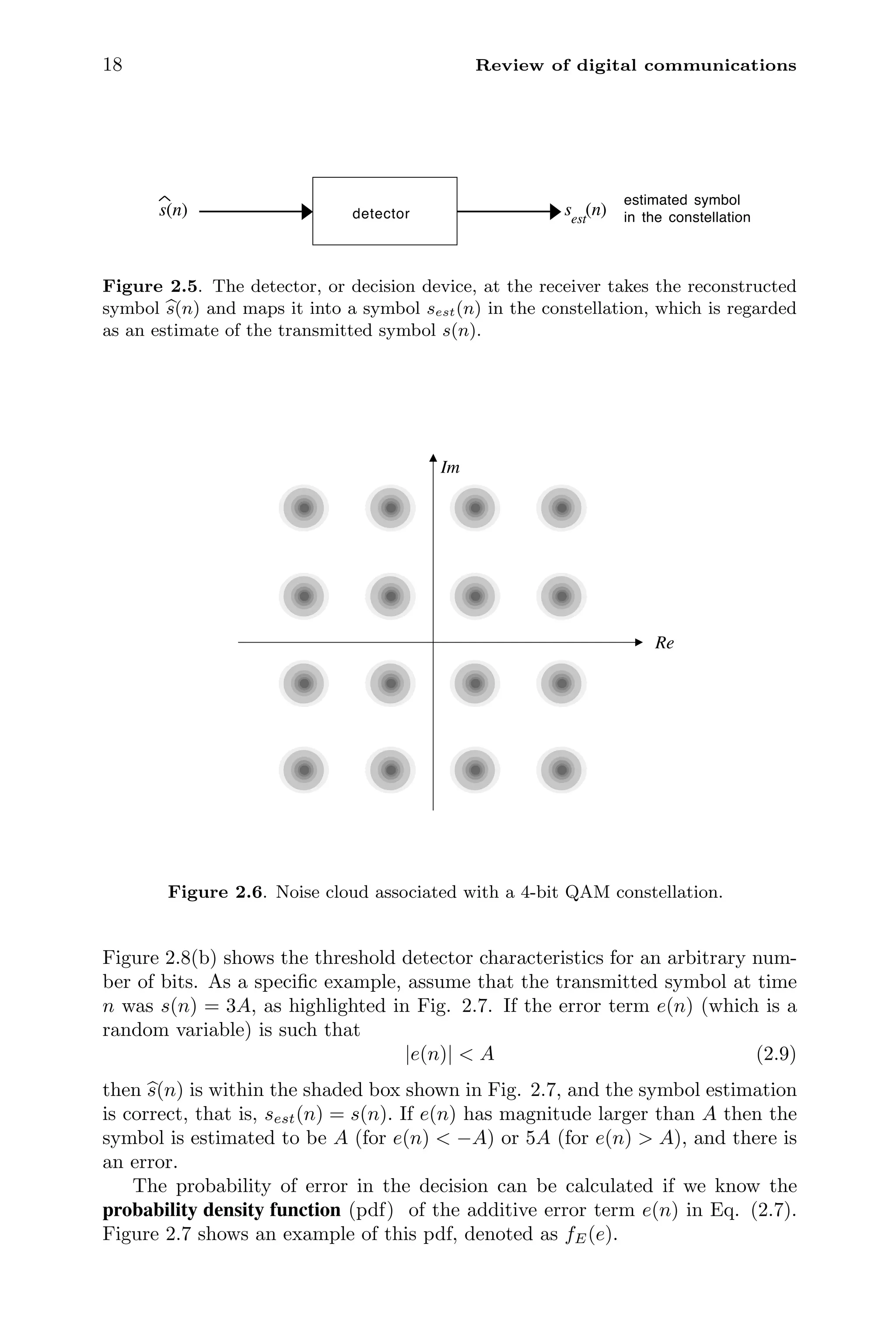

![14 Review of digital communications

symbol sest(n) can sometimes be different from s(n), resulting in an error. Under

appropriate assumptions on the statistics of the reconstruction error it is possible

to compute the probability of error in symbol identification. This is done in Sec.

2.3. In practice the baseband signal x(t) is used to modulate a high-frequency

carrier signal, and the modulated signal is transmitted. At the receiver this

signal is demodulated to extract the (noisy version of) the baseband signal. The

details of this modulation and demodulation are different for PAM and QAM

constellations, and will be presented in Sec. 2.4.

Returning to the postfilter G(jω), we mentioned in Chap. 1 that it is called

the equalizer, and compensates for the channel distortions. In practice, this

equalization is often performed with a digital filter after the sampling process.

The analog filter G(jω) then plays a different role called matched filtering. The

purpose of this filter is to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio at the sample lo-

cations, and its optimal choice depends on the channel H(jω) as well as on the

power spectrum of the noise q(t). Matched filtering is reviewed in Sec. 2.5, and

some practical details are discussed in Sec. 2.6.

2.2 Signal constellations

Two of the popular constellations widely used today are the PAM (pulse am-

plitude modulation) and the QAM (quadrature amplitude modulation) constel-

lations. The PAM constellation has real-valued numbers for s(n), whereas the

QAM constellation has complex numbers. A b-bit PAM or QAM constella-

tion has M = 2b

allowed numbers, called constellation symbols or codewords

(sometimes written as code words), and is also called an M-PAM or M-QAM

constellation.

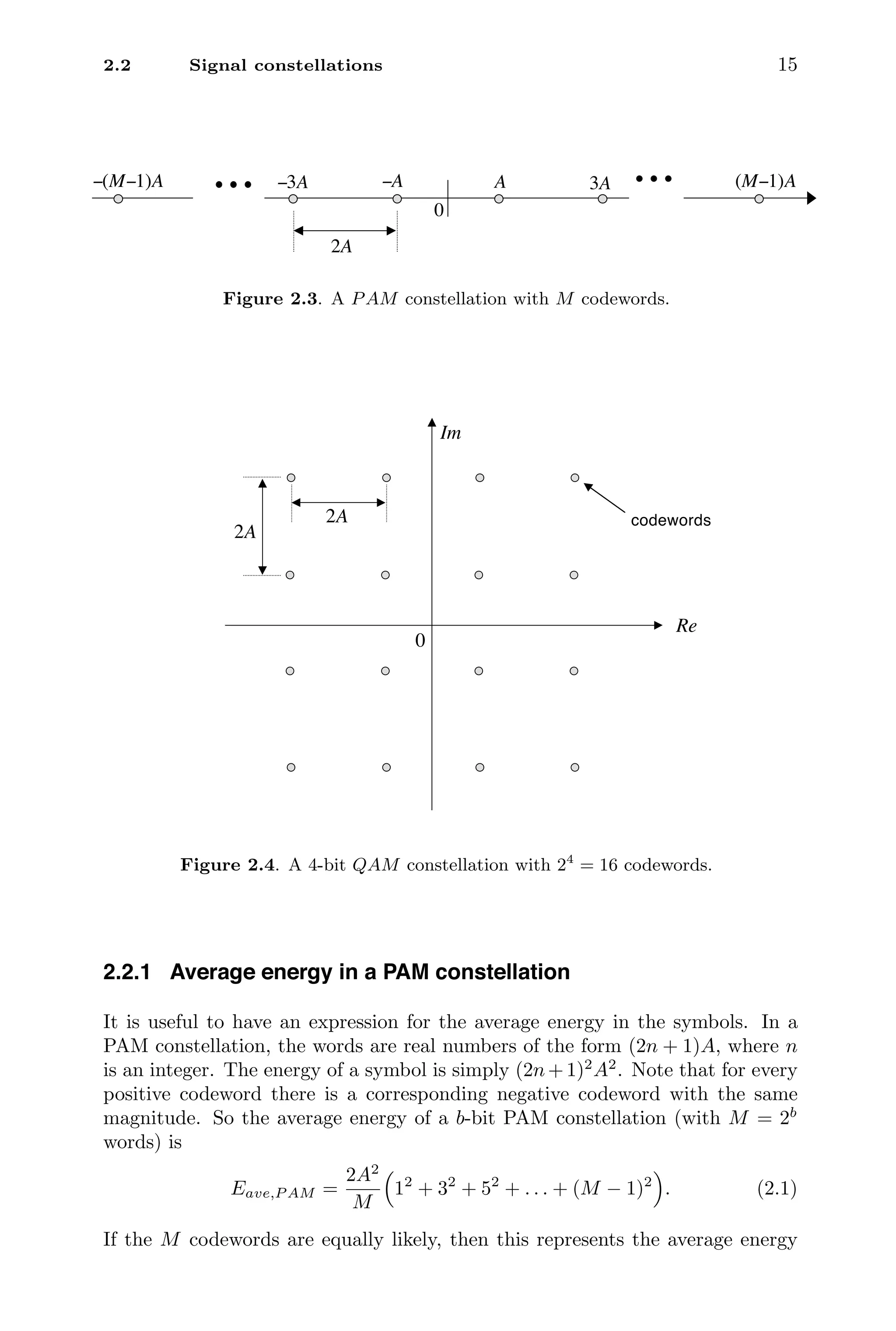

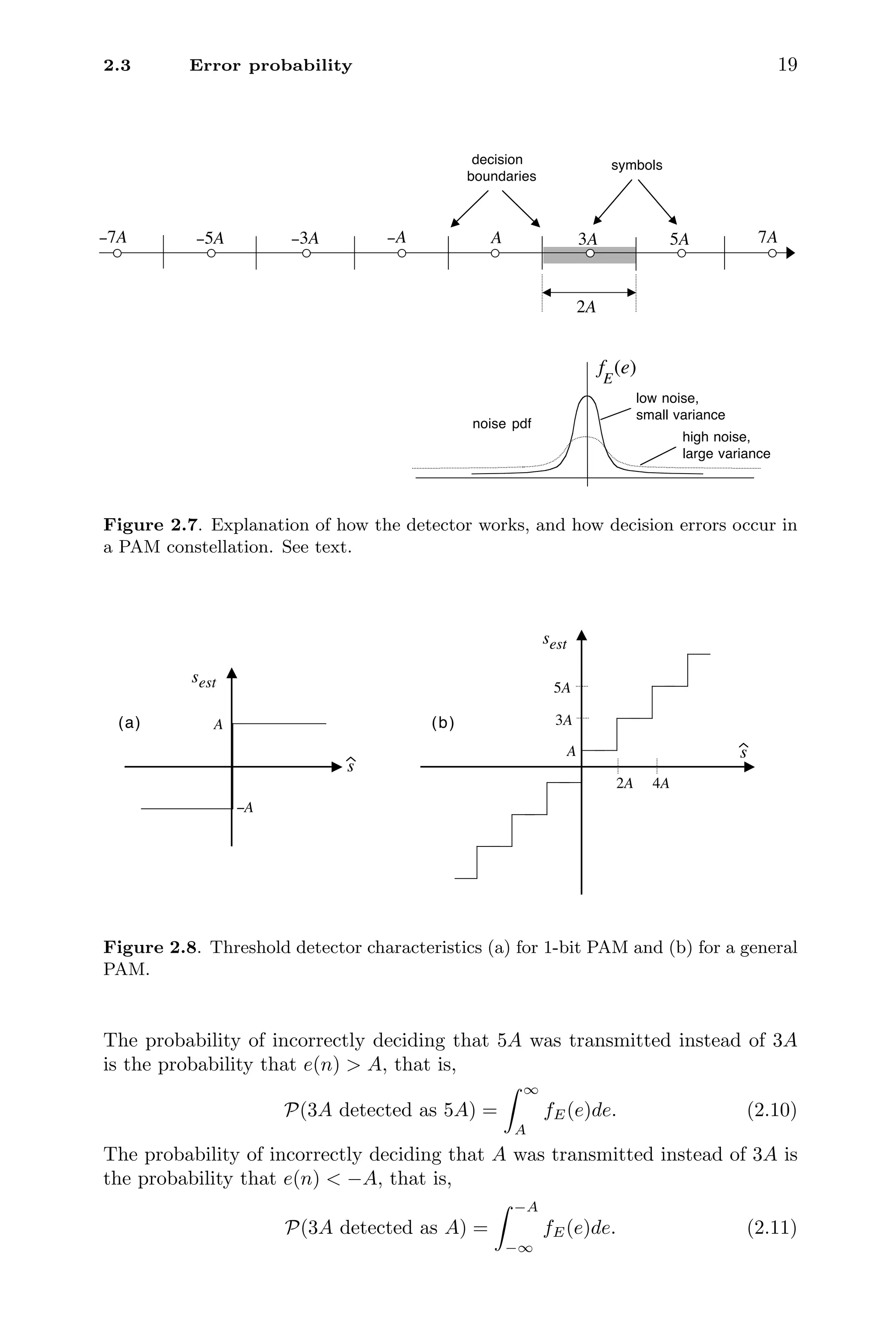

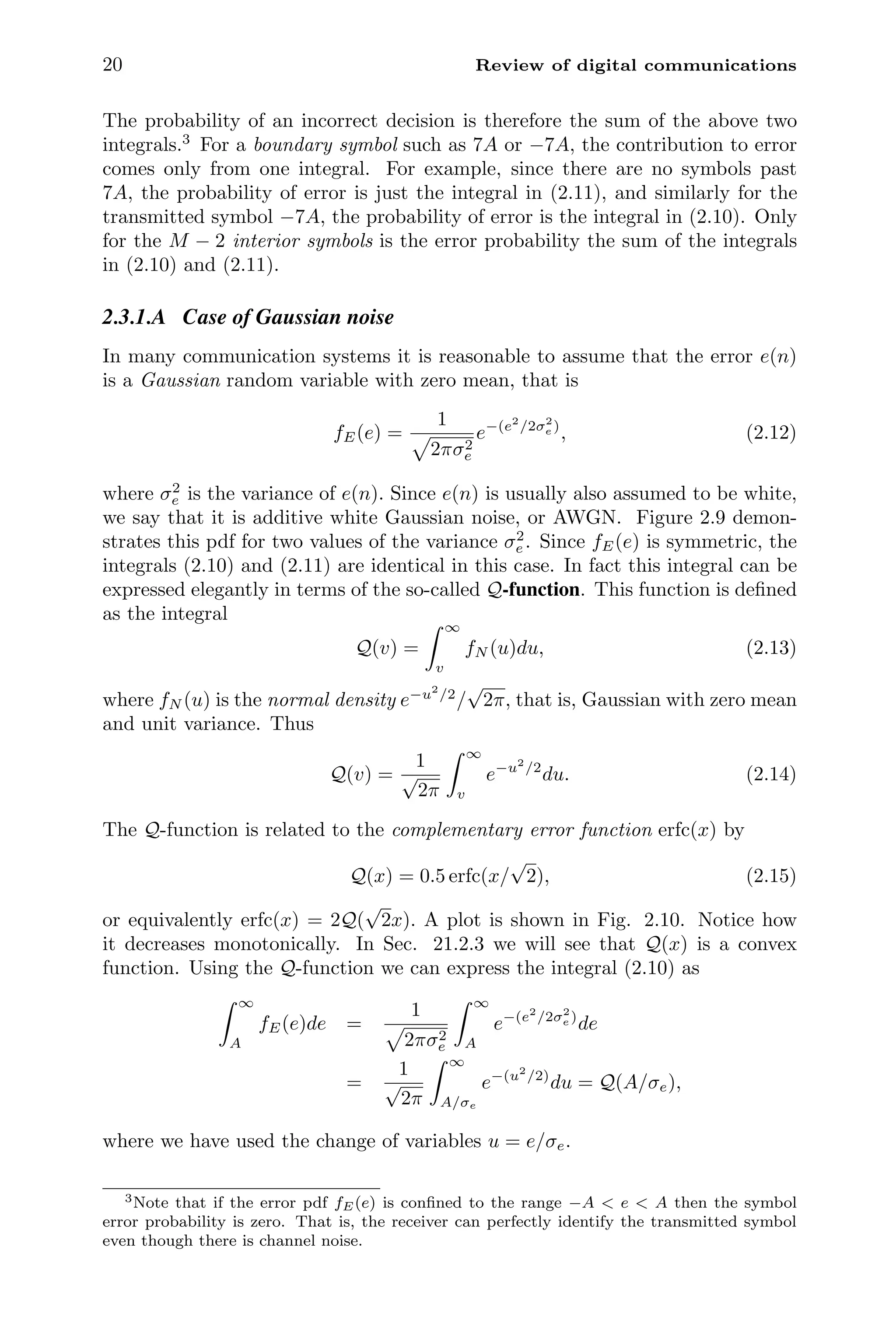

Figure 2.3 shows a PAM constellation with M codewords. Note that M is

even (a power of 2), and adjacent codewords are separated by a fixed amount

2A. No codeword has value zero. The positive number A can be chosen to adjust

the average energy per codeword as we shall see later. Figure 2.4 shows a QAM

constellation with M = 16 codewords. This is a 4-bit constellation. Once again,

no codeword has value zero. Note that any 4-bit QAM code word has the form

z = x + jy,

where x and y are 2-bit PAM words. The components x and y are sometimes

called the in-phase and quadrature components. A b-bit QAM constellation

has real and imaginary parts coming from (b/2)-bit PAM constellations. The

QAM constellations we use here are called square QAM constellations. More

generally they can be rectangular constellations with b1 bits for x and b2 bits

for y. There are more general types of QAM constellations including circular

ones [Proakis, 1995], but we shall not elaborate on those here. Unless mentioned

otherwise, we always imply square constellations when we use the term QAM.

So the number of bits b is an even integer. As in PAM, any word in the square

QAM constellation has nearest neighbors at distance 2A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65604-250620202834-0ce82231/75/Signal-Processing-and-Optimization-for-Transceiver-Systems-1st-Edition-P-P-Vaidyanathan-35-2048.jpg)

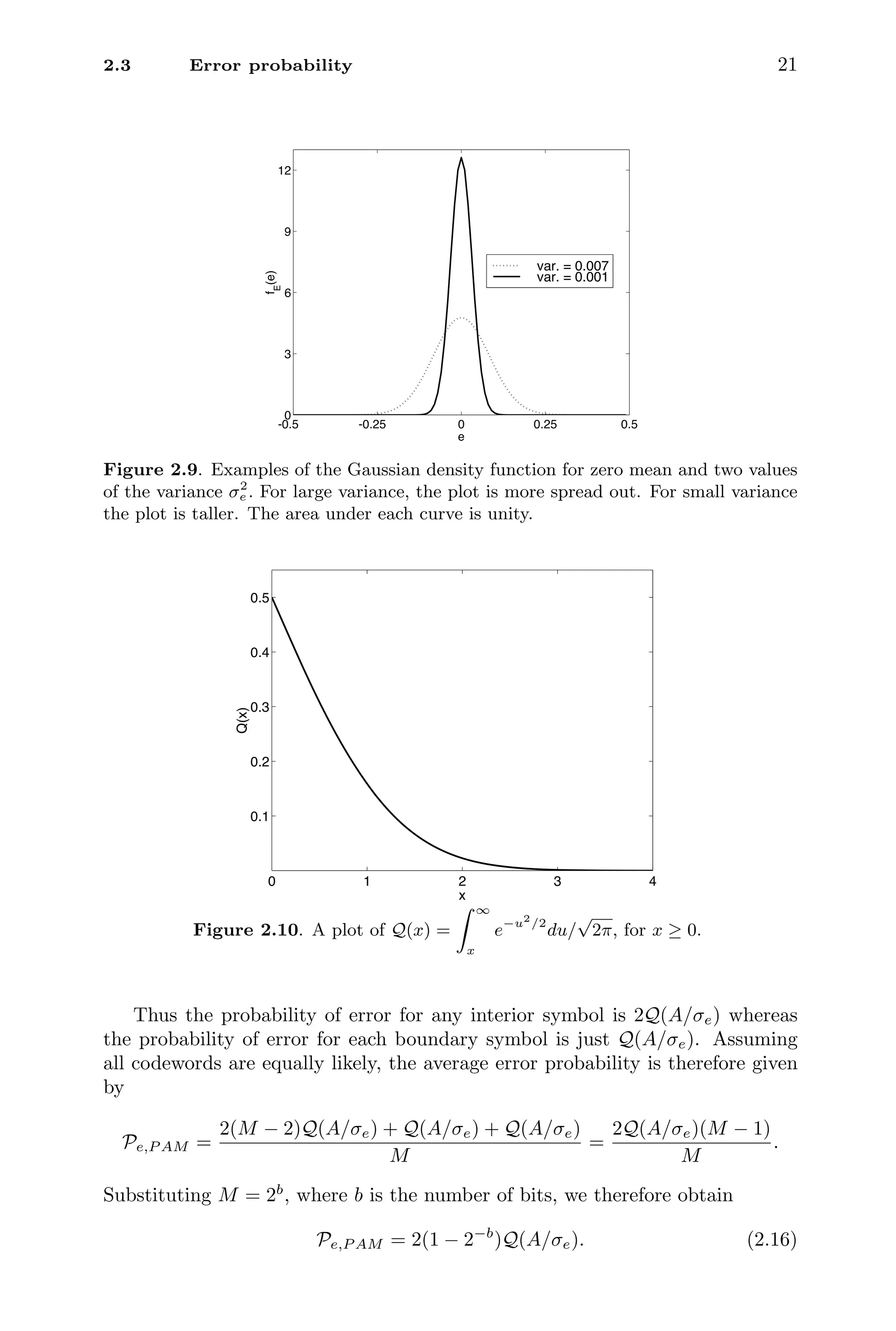

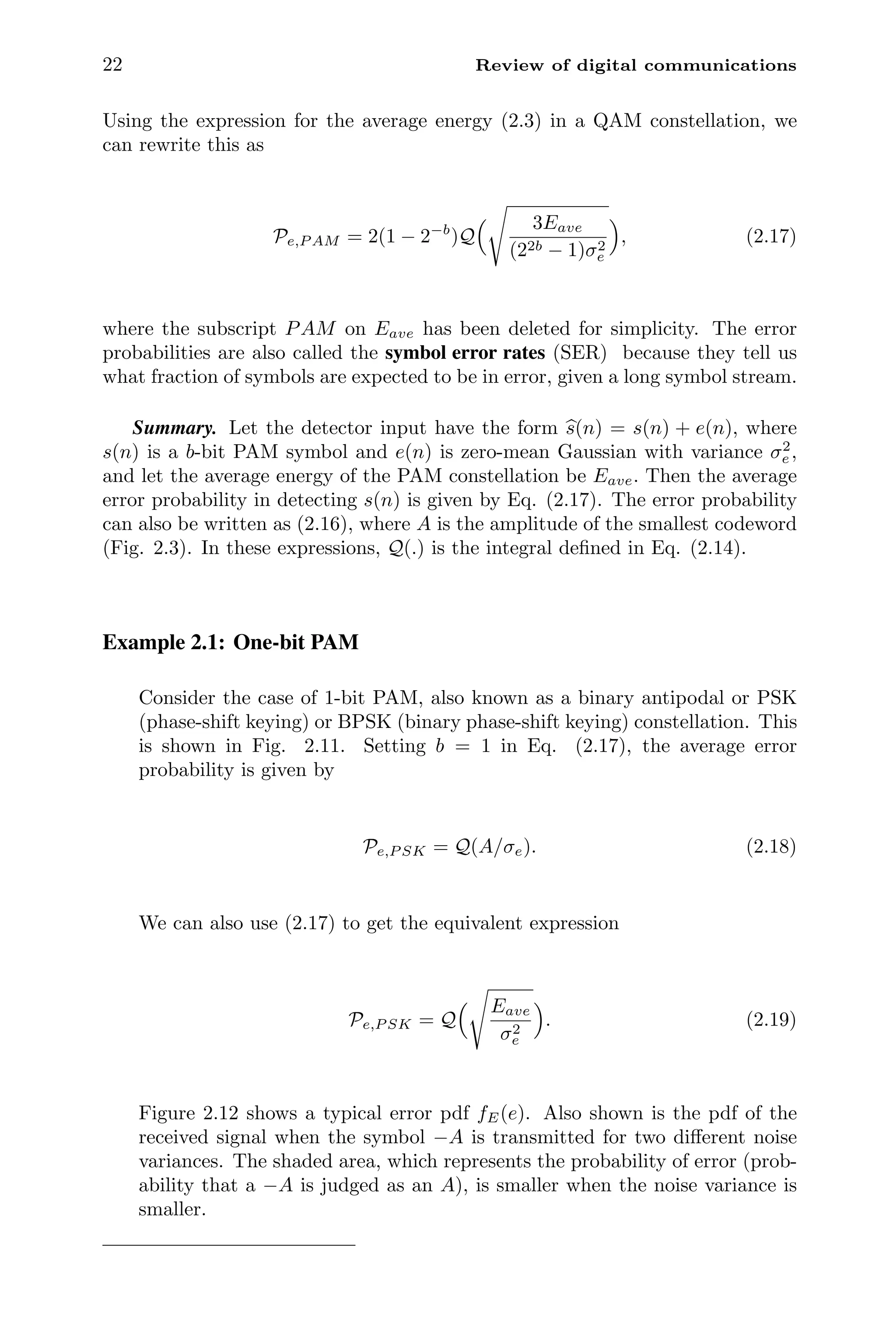

![24 Review of digital communications

of the transmitted symbol stream s(n), of the form

s(n) = s(n) + e(n), (2.20)

where e(n) is the reconstruction error. Recall here that s(n), and hence

s(n),

are complex numbers. It is usually reasonable to assume that the error e(n) is

complex and has the form

e(n) = er(n) + jei(n),

where er(n) and ei(n) are independent zero-mean Gaussian random variables

with identical variance 0.5σ2

e . In this case the total variance of the complex error

e(n) is

0.5σ2

e + 0.5σ2

e = σ2

e .

The joint pdf of the variables [er(n), ei(n)] is given by

fE(er, ei) =

e−e2

r/σ2

e

πσ2

e

×

e−e2

i /σ2

e

πσ2

e

=

e−(e2

r+e2

i )/σ2

e

πσ2

e

. (2.21)

Figure 2.13 demonstrates this for σ2

e = 0.01. This is a special case of a so-called

circularly symmetric complex Gaussian random variable.4

Next, the complex

symbol s(n) is of the form

sr(n) + jsi(n),

where sr(n) and si(n) are PAM symbols. Since

|s(n)|2

= s2

r(n) + s2

i (n),

it follows that the average energy of the constellation is the sum of the average

energies of the real and imaginary parts. Thus, for a b-bit QAM constellation

with average energy Eave, the real and imaginary parts are (b/2)-bit PAM con-

stellations with average energy Eave/2, and each of these PAM constellations

sees an error source with variance σ2

e /2. For the real-part PAM the probability

of error can be obtained from Eq. (2.17) by replacing b, Eave, and σ2

e with half

their values:

Pe,re = 2(1 − 2−b/2

)Q

3Eave

(2b − 1)σ2

e

. (2.22)

Since the factor of one-half cancels out in the ratio Eave/σ2

e , this is nothing but

the error probability for a (b/2)-bit PAM constellation with energy Eave and

noise variance σ2

e . Similarly for the imaginary part

Pe,im = 2(1 − 2−b/2

)Q

3Eave

(2b − 1)σ2

e

. (2.23)

The QAM symbol is detected correctly if the real part and imaginary part are

both detected correctly. The probability for this is

(1 − Pe,re)2

.

4A detailed discussion of circularly symmetric complex random variables can be found in

Sec. 6.6.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65604-250620202834-0ce82231/75/Signal-Processing-and-Optimization-for-Transceiver-Systems-1st-Edition-P-P-Vaidyanathan-45-2048.jpg)

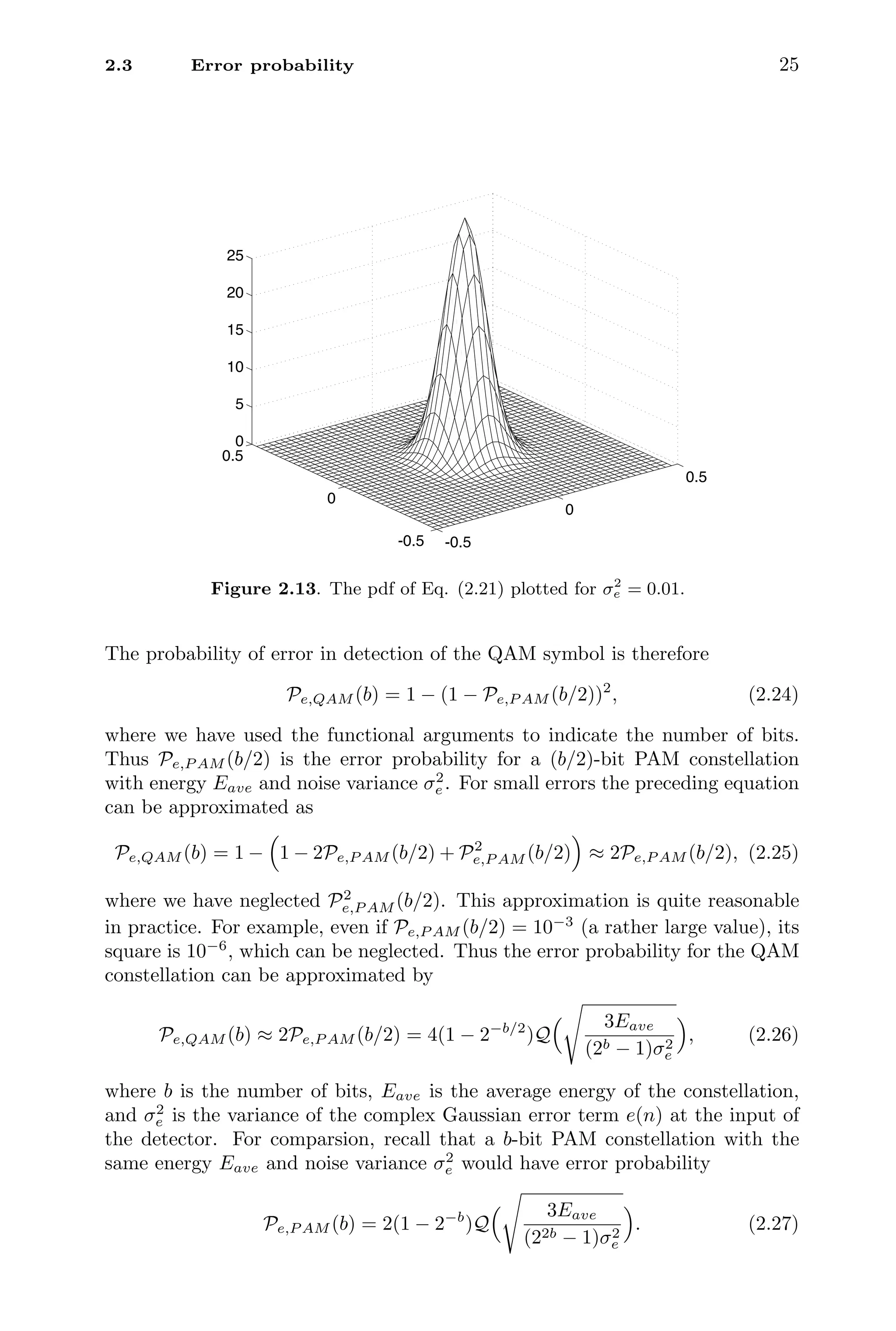

![26 Review of digital communications

Example 2.2: Two-bit QAM or QPSK

Consider the case of 2-bit QAM, also known as a QPSK (quadrature phase-

shift keying) constellation. This is shown in Fig. 2.14. Setting b = 2 in Eq.

(2.26), the average error probability is given by

Pe,QP SK = 2Q

Eave

σ2

e

. (2.28)

For both the PAM and QAM systems, note that the error probability depends on

the ratio Eave/σ2

e , rather than the individual values of the energy Eave and the

error variance σ2

e . This ratio is called the signal-to-error ratio or signal-to-noise

ratio SNR at the input of the detector:

SNR =

Eave

σ2

e

(2.29)

Figure 2.15 shows plots of the symbol error probability Pe,P AM as a function of

this SNR for PAM systems, for various values of the number of bits b. Figure 2.16

shows similar plots for QAM systems. To compare PAM and QAM systems, it

is useful to introduce the bit error rates (BER), which are related to the symbol

error rates. Before doing this we have to introduce a binary coding system called

the Gray code.

2.3.3 Gray codes

In digital communication systems we are often required to transmit binary

streams. These streams can be converted to PAM or QAM symbols by ap-

propriately grouping the bits. This is called the symbol modulation process. For

example, if the binary stream is divided into blocks of size 3:

. . . 010 001 111 011 100 . . .

then each 3-bit block can be turned into a 3-bit PAM symbol. More generally, a

b-bit block can be translated into an M-word constellation with M = 2b

. There

are many ways to define the mapping from the binary representation to the

constellation words. Figure 2.17 shows an example of such a representation for

a 3-bit PAM constellation. Thus the preceding binary sequence is converted to

. . . − A, −5A, 3A, −3A, 7A, . . .

In this example the binary words are assigned such that adjacent symbols in

the constellation (Fig. 2.17) differ only in one of the bit locations. Such a

representation is called a Gray code [Proakis, 1995].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65604-250620202834-0ce82231/75/Signal-Processing-and-Optimization-for-Transceiver-Systems-1st-Edition-P-P-Vaidyanathan-47-2048.jpg)