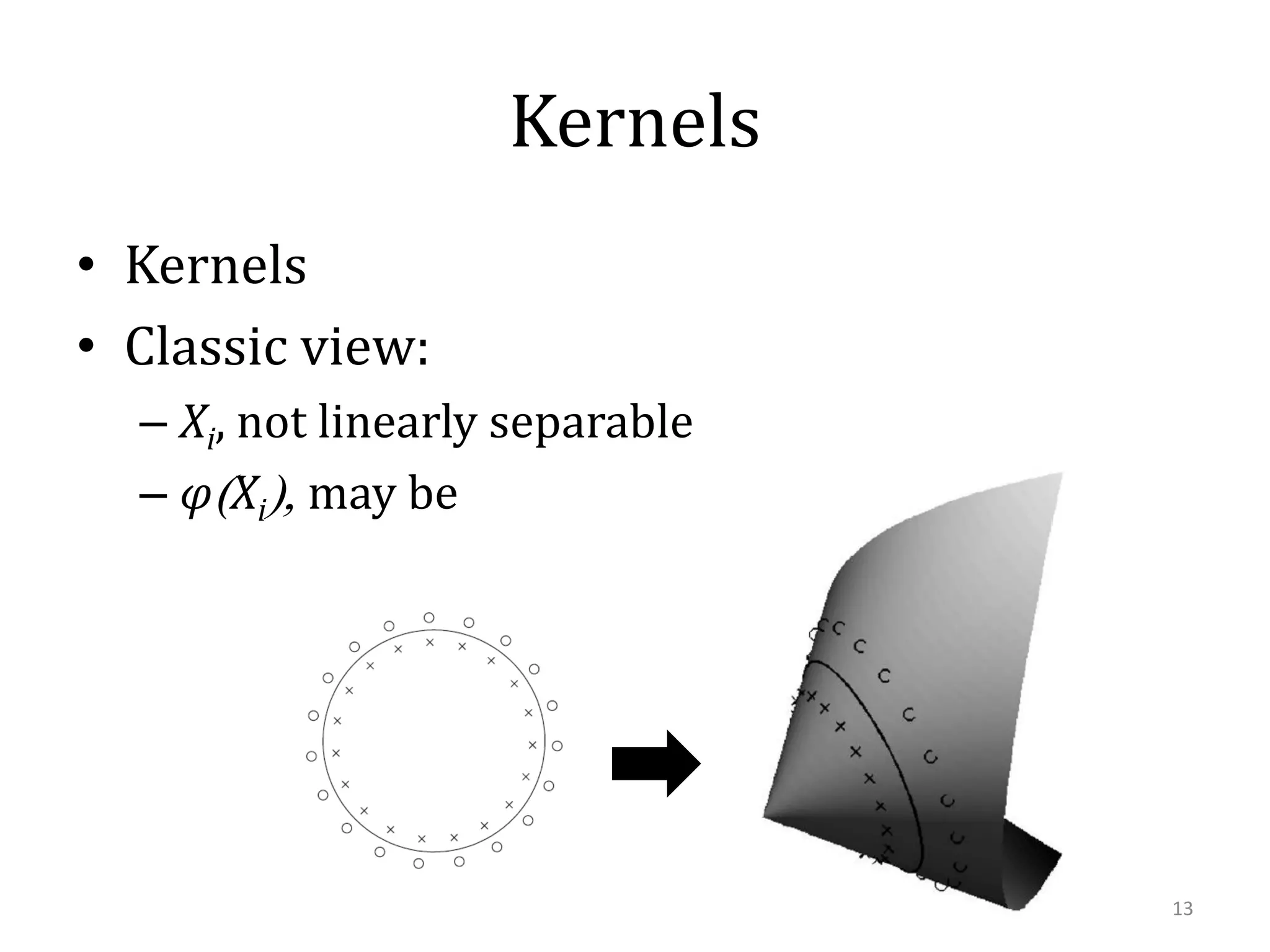

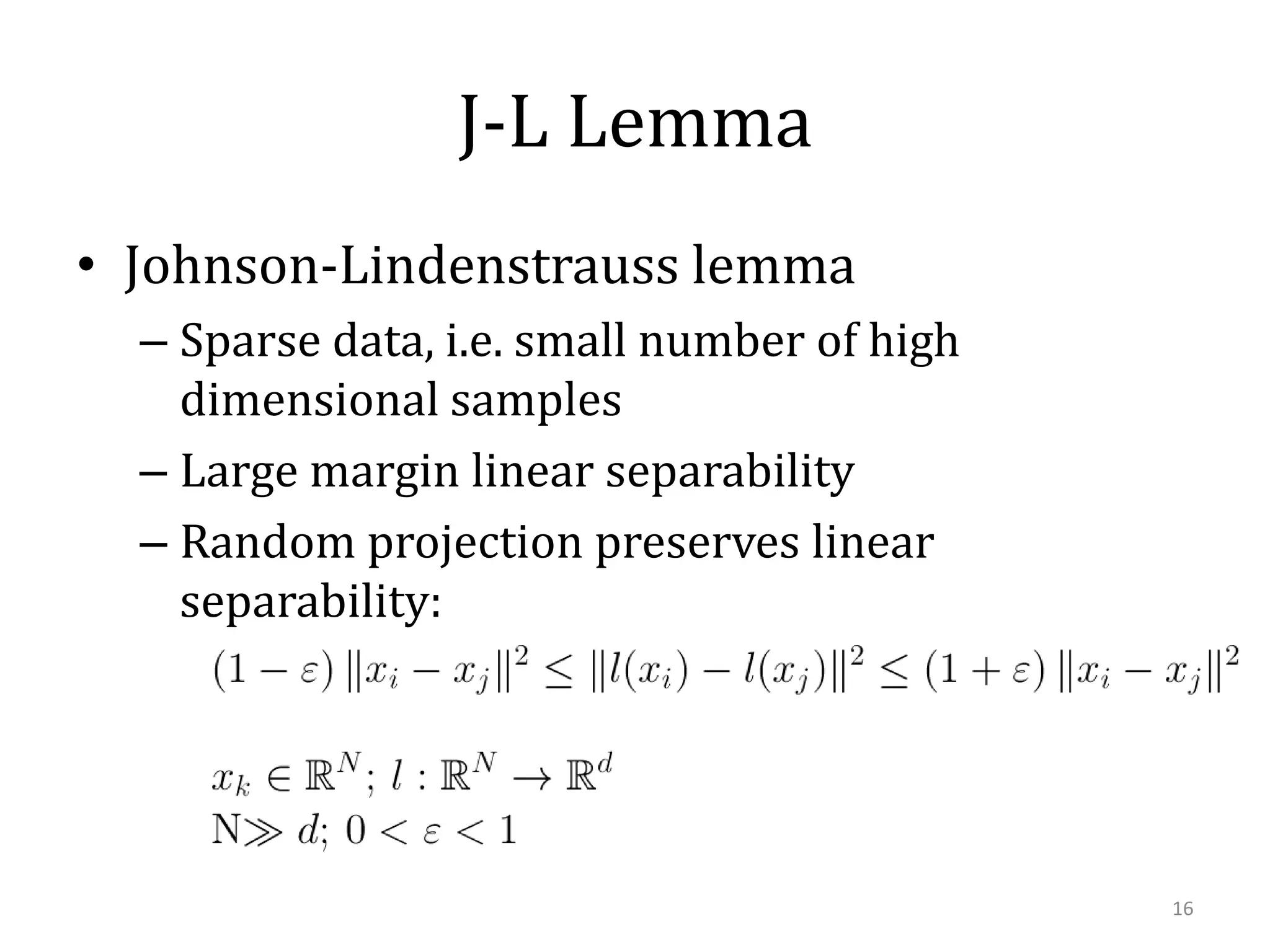

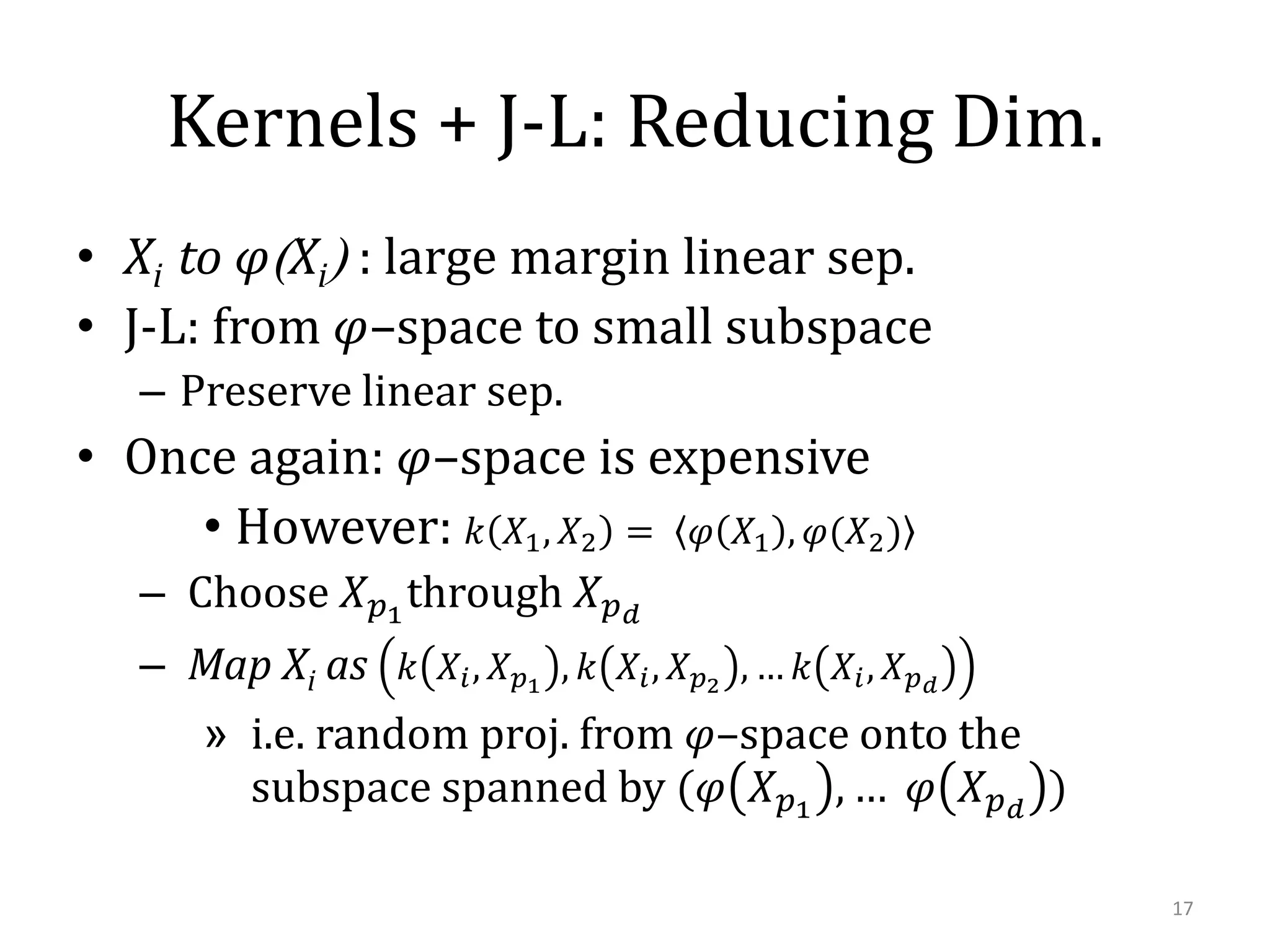

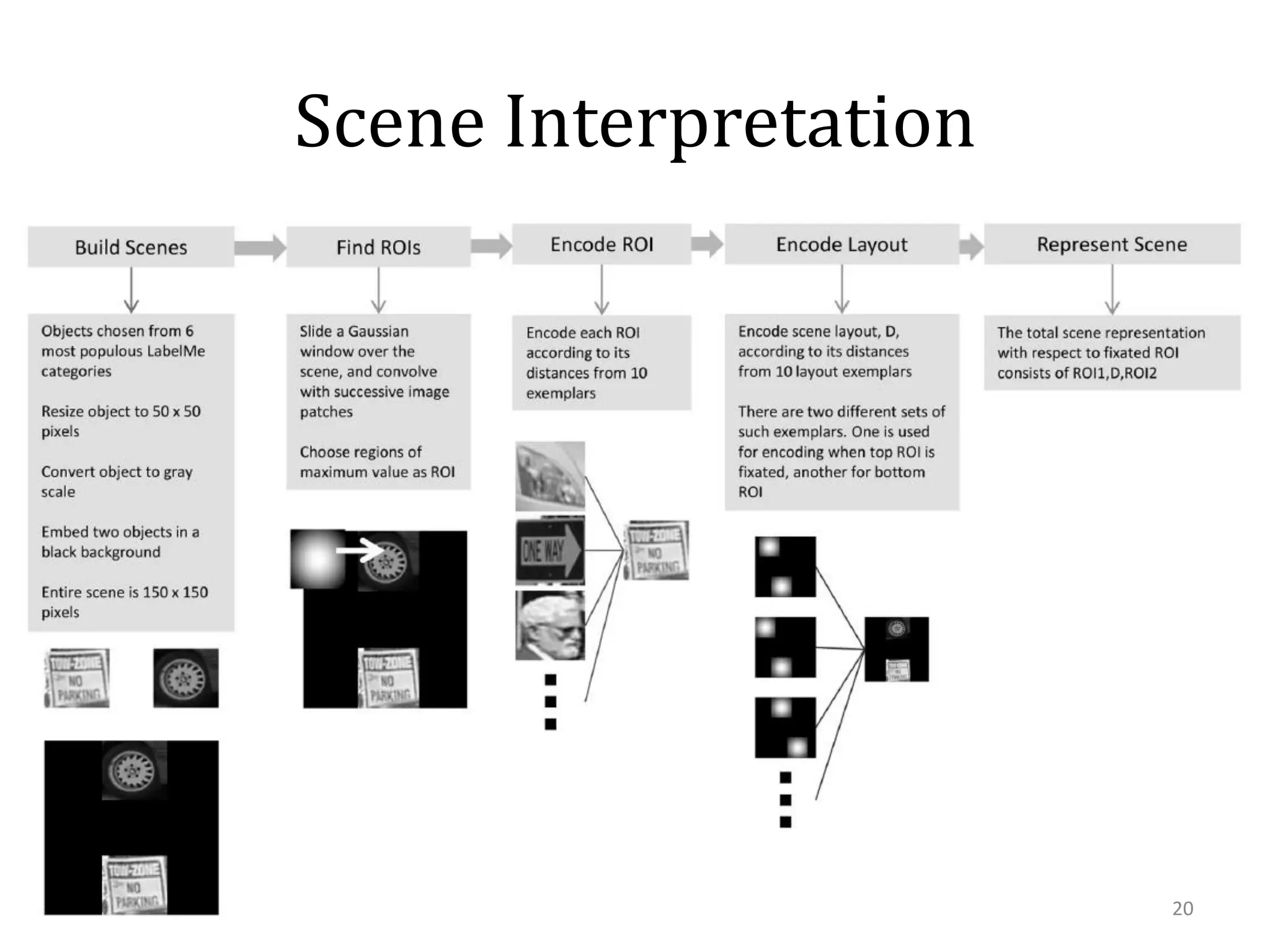

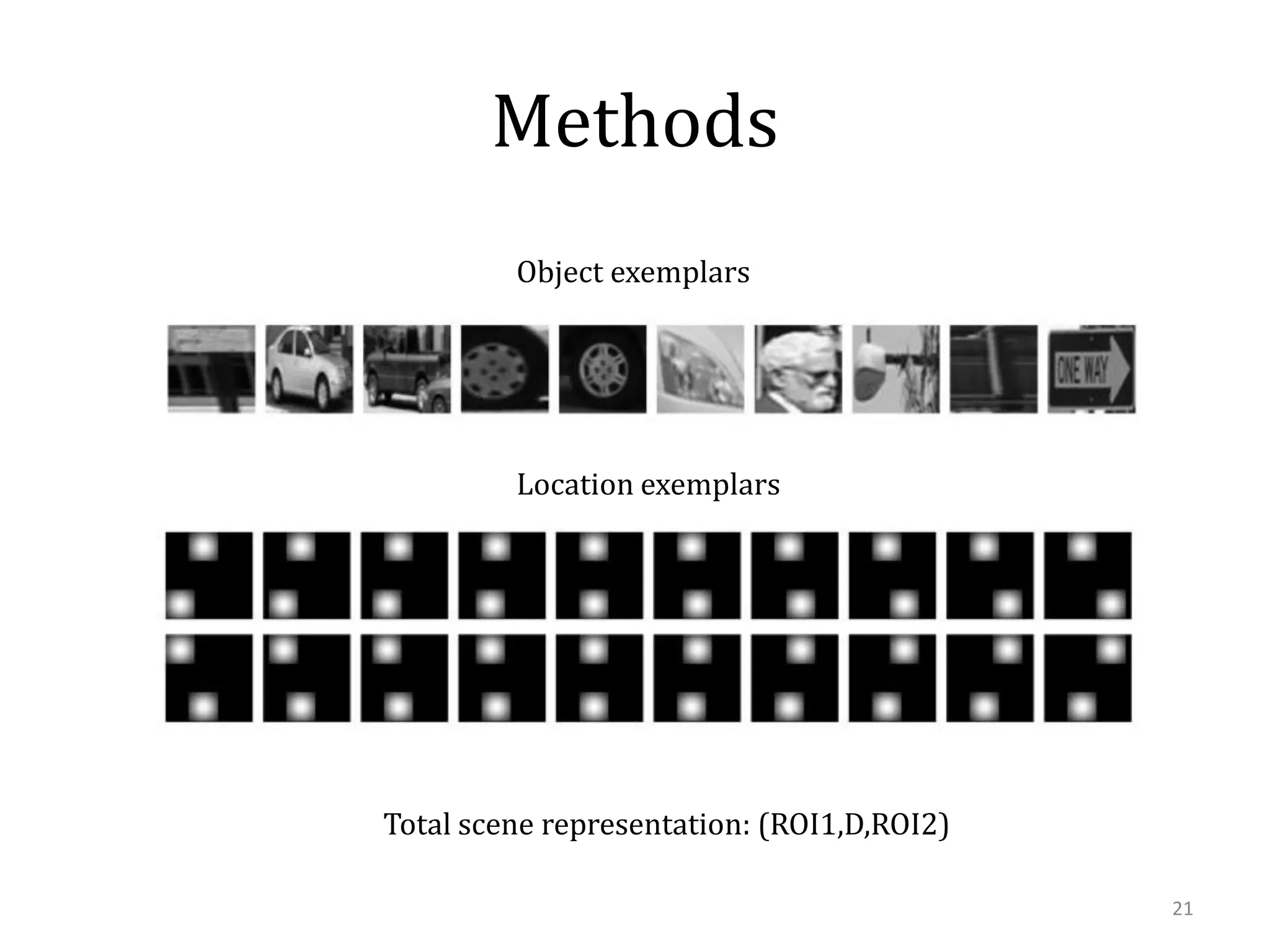

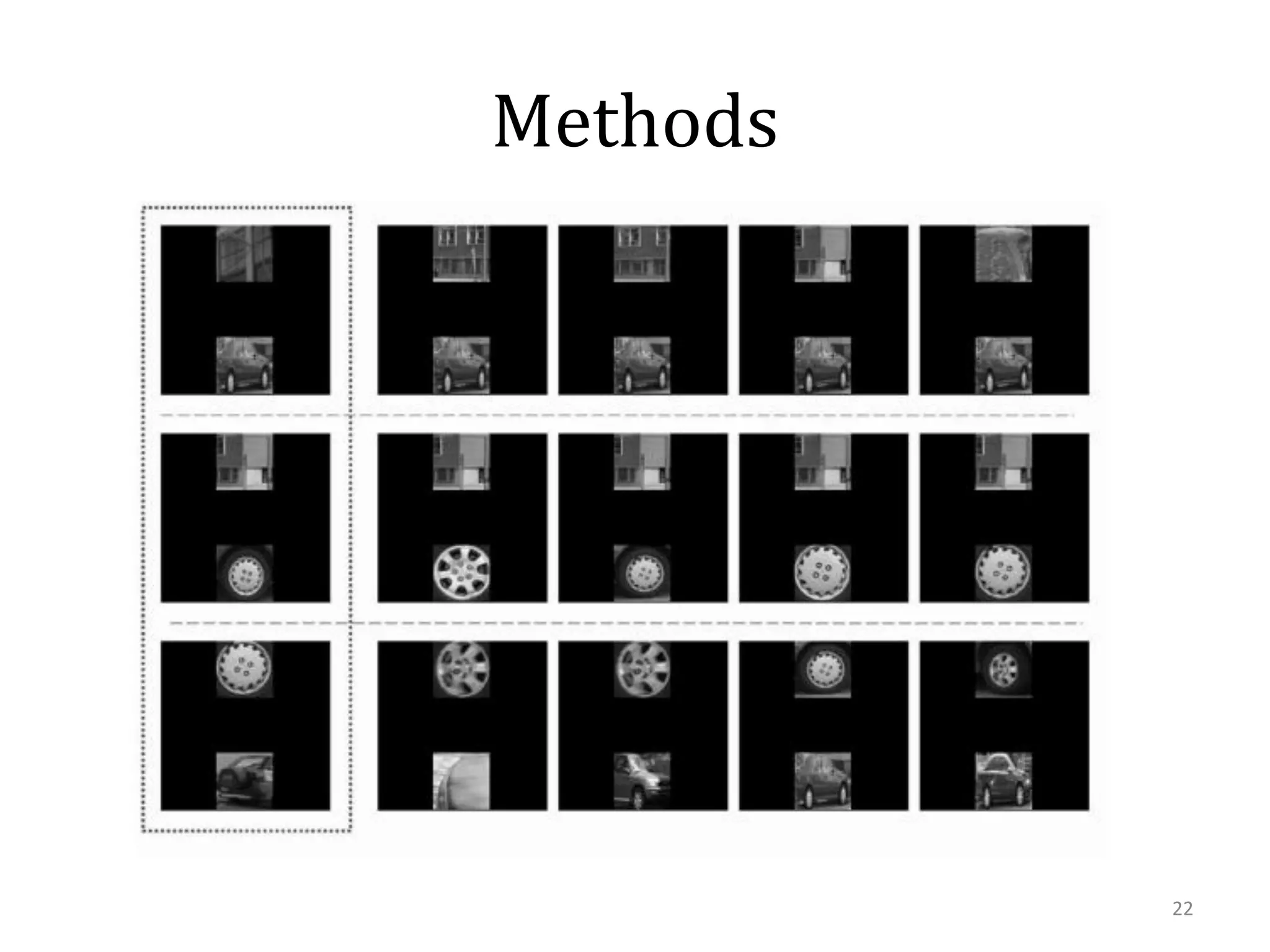

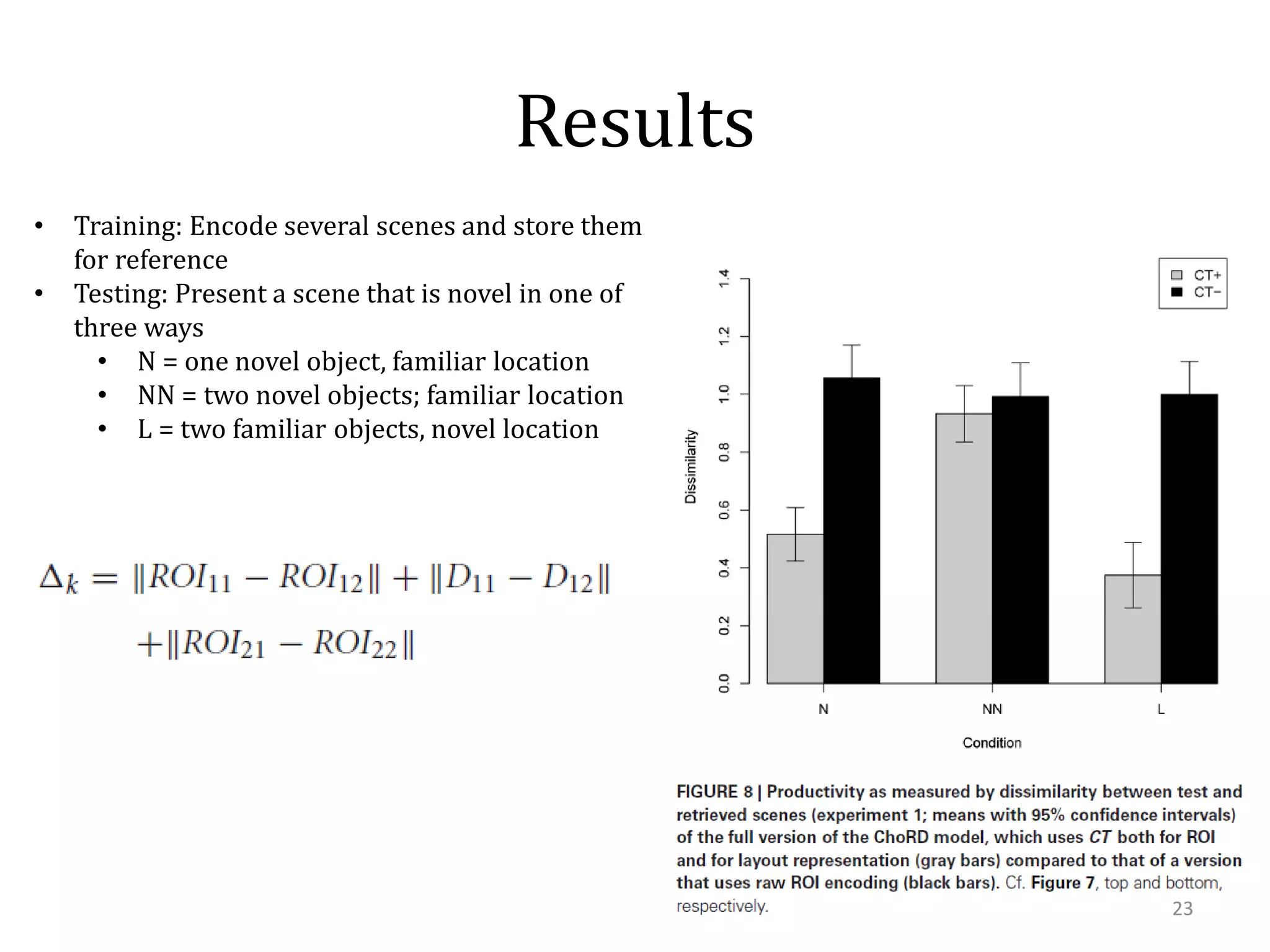

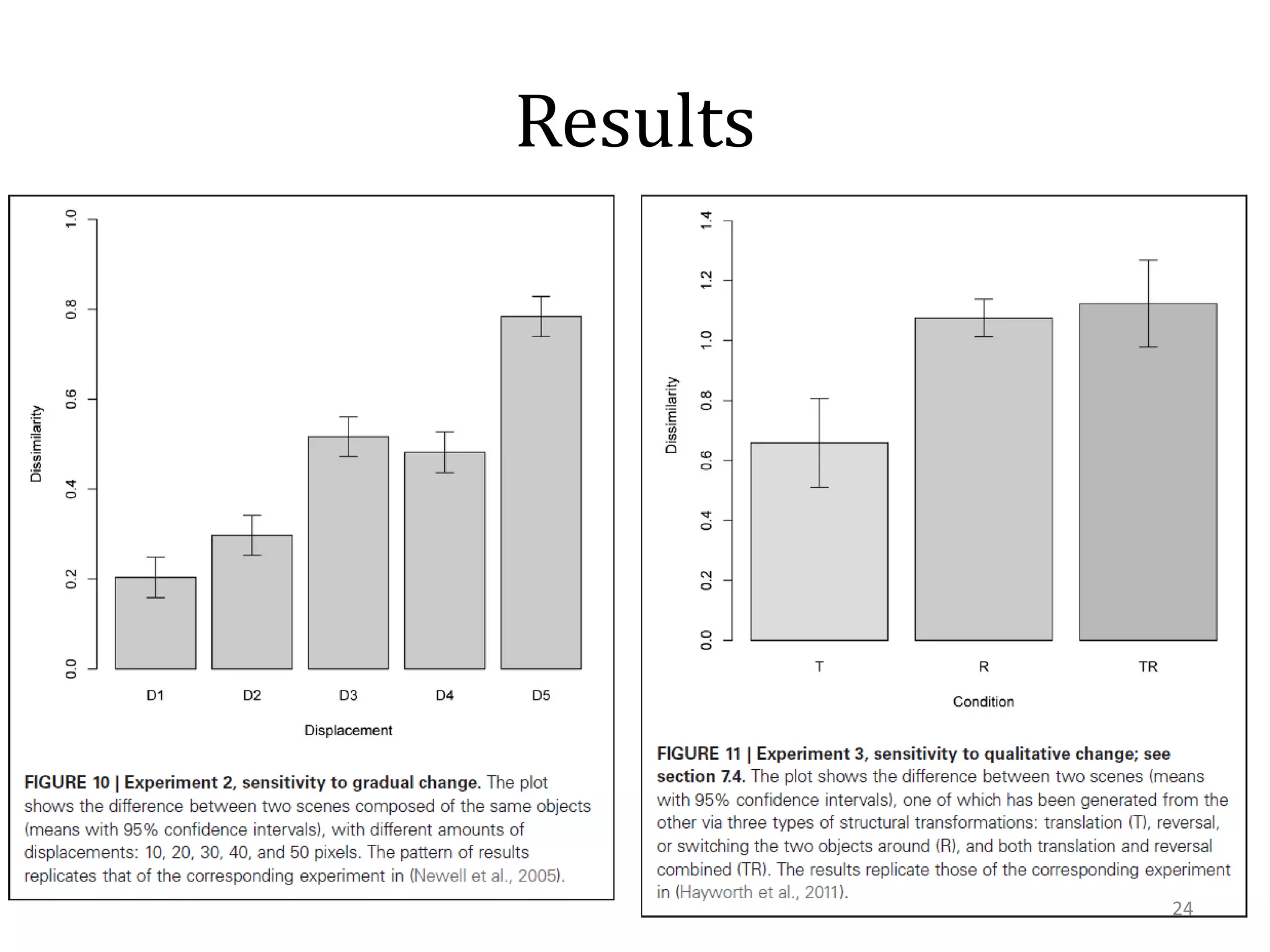

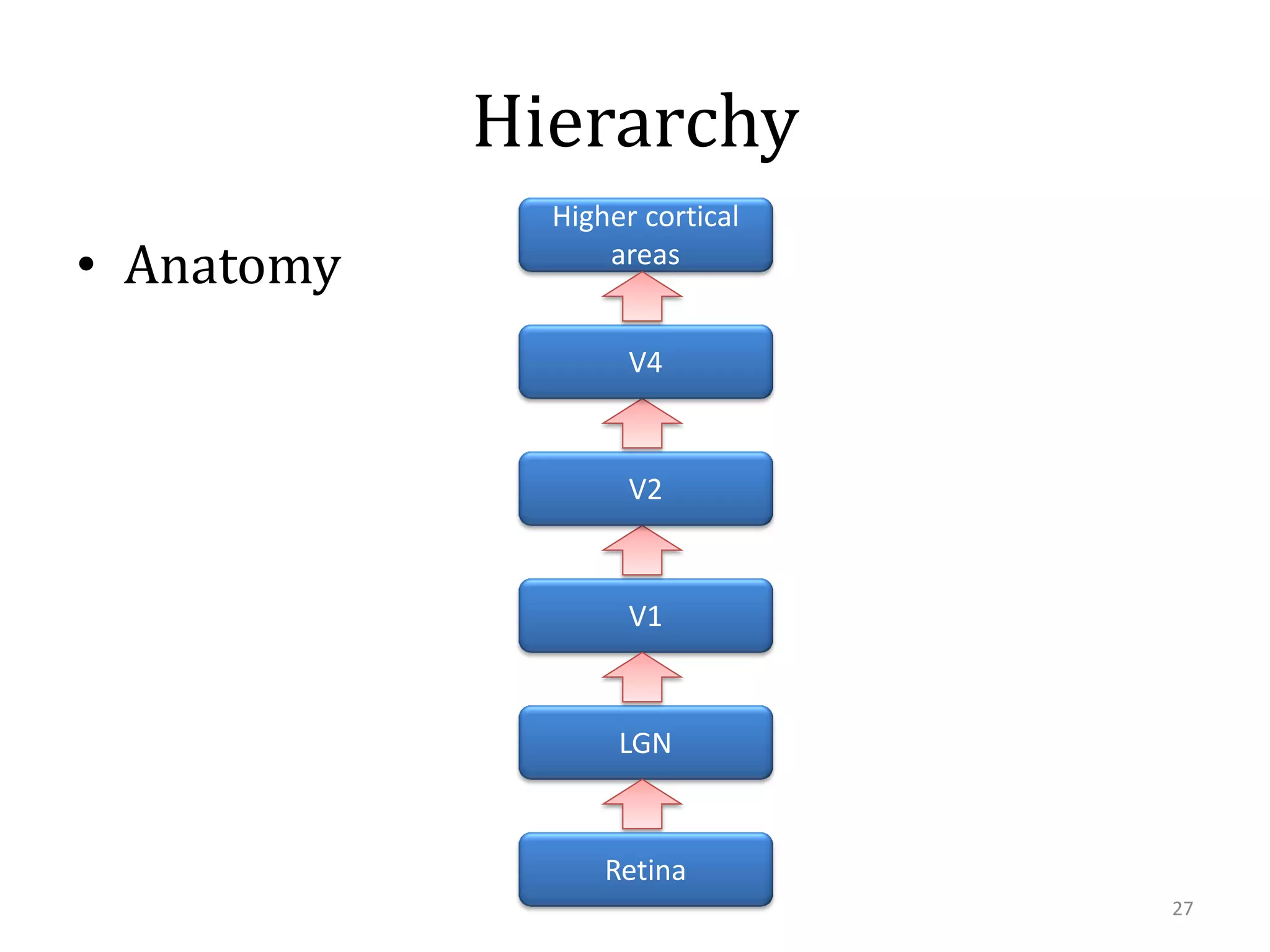

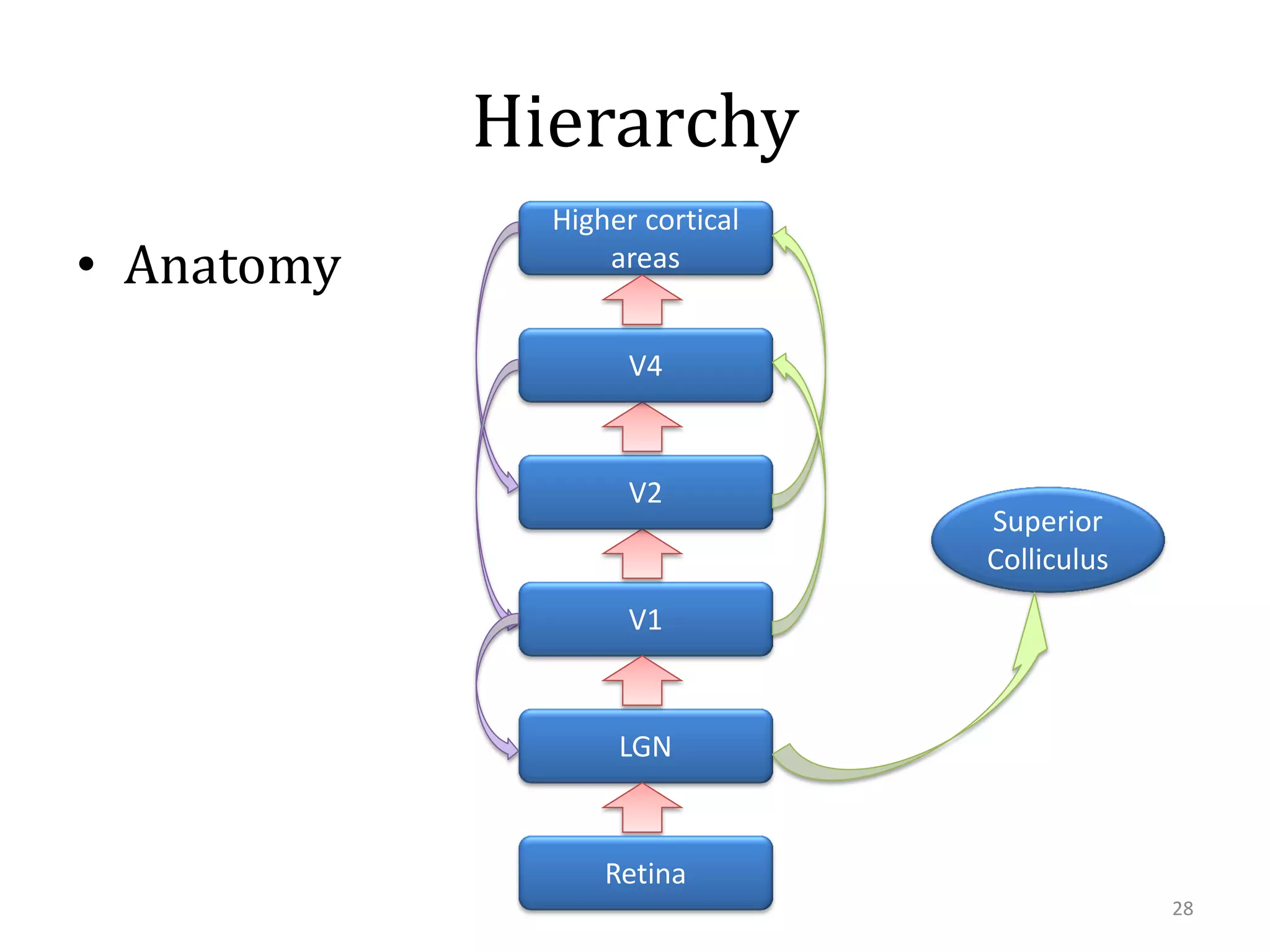

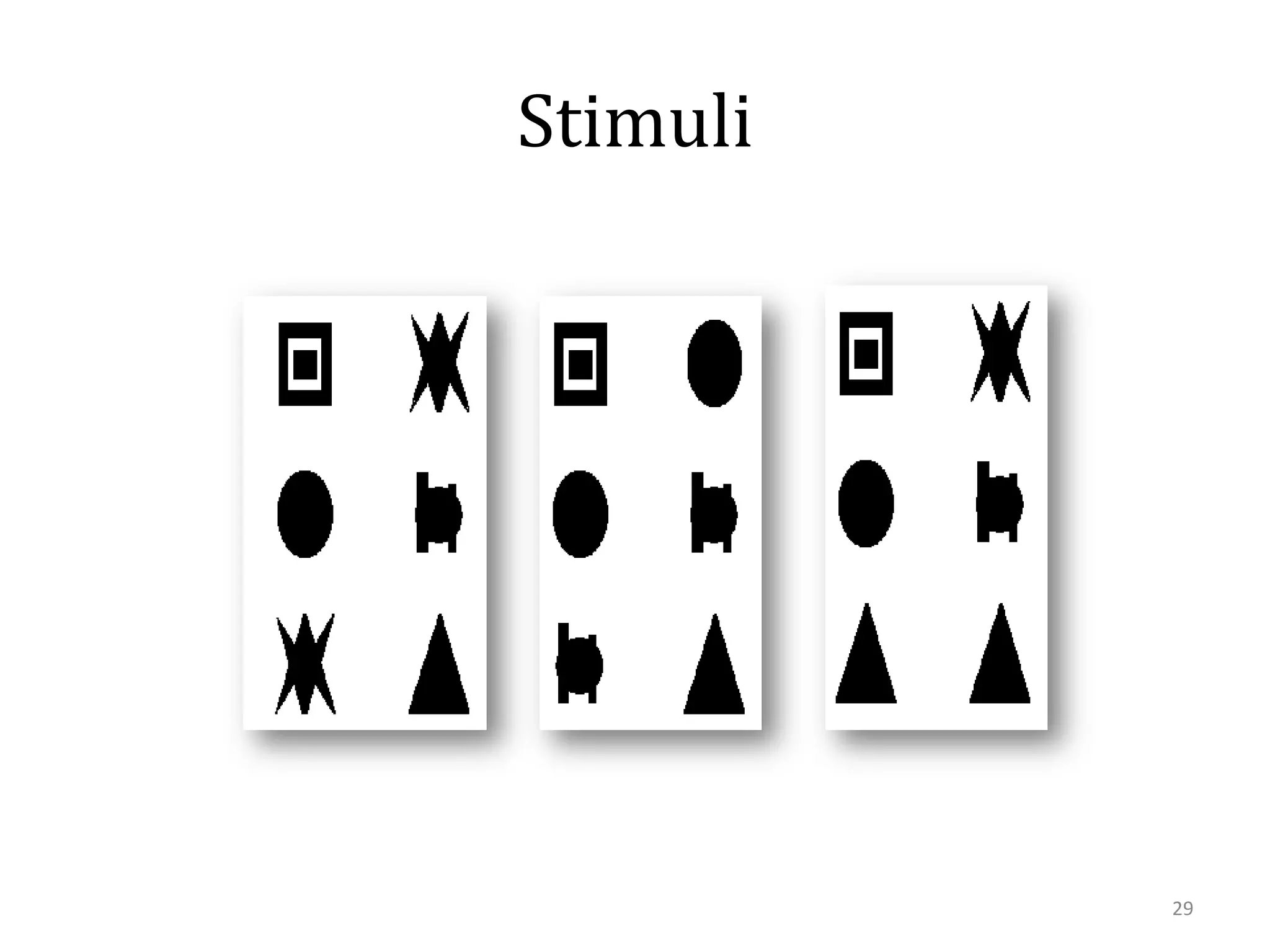

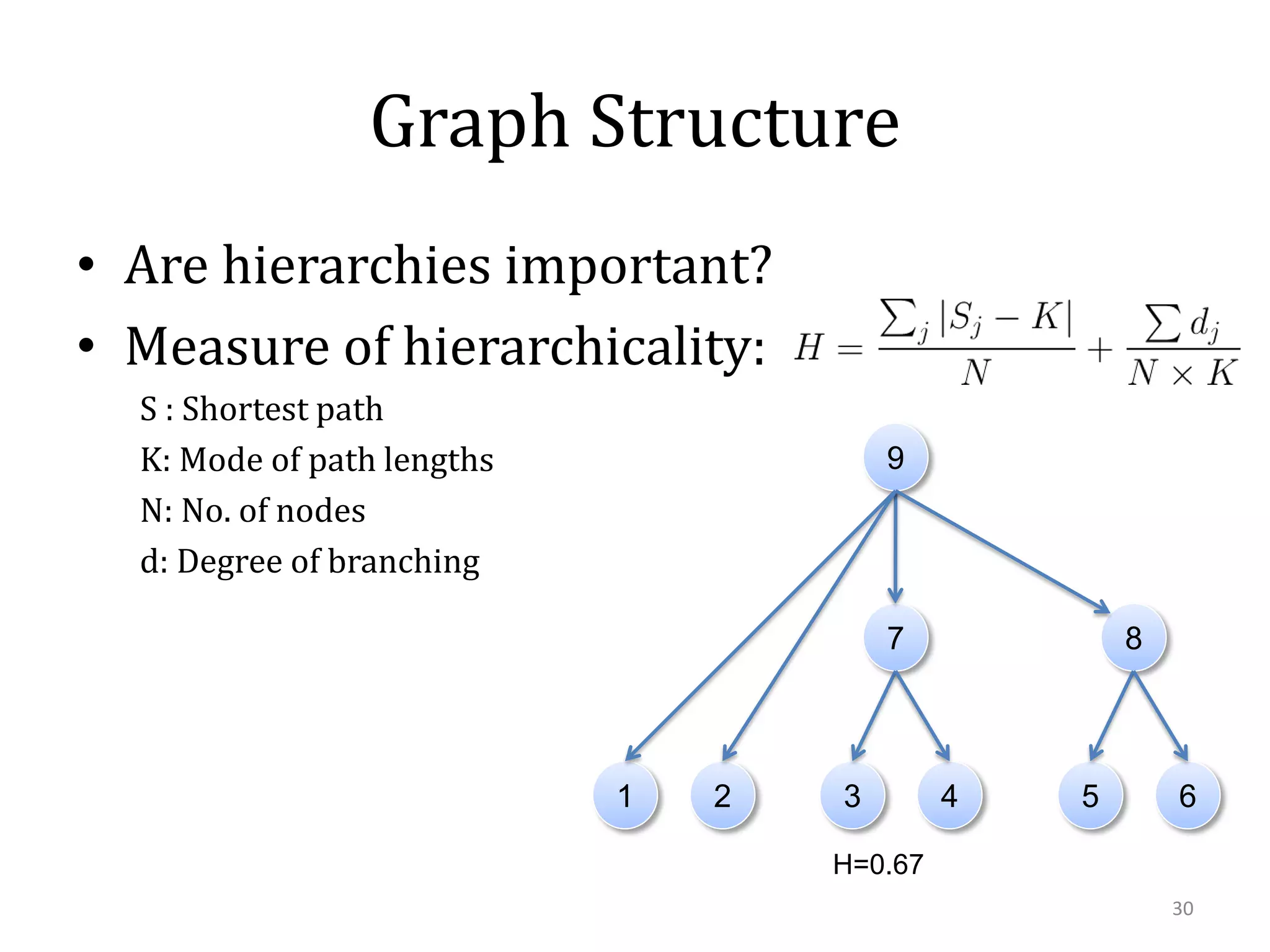

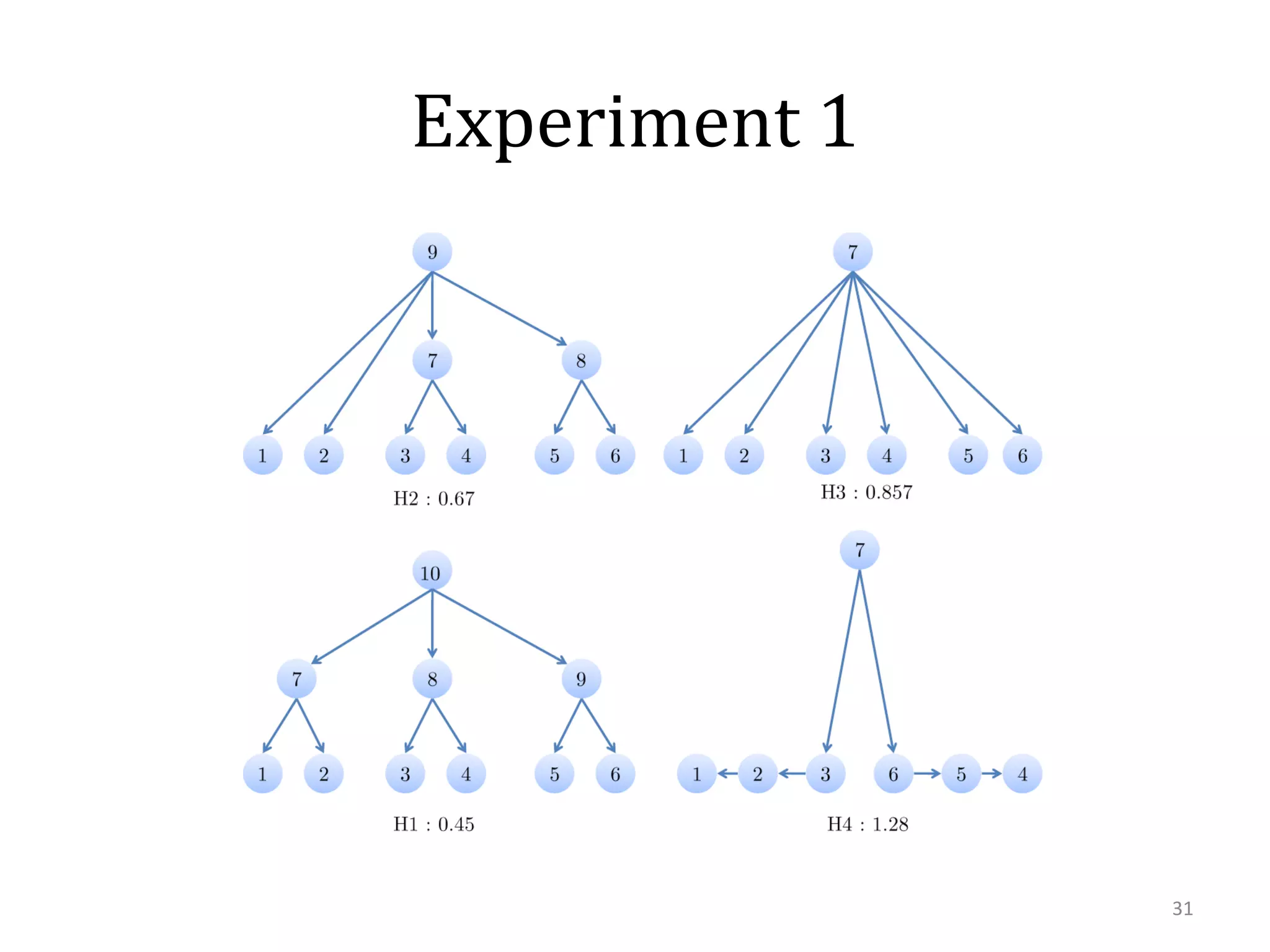

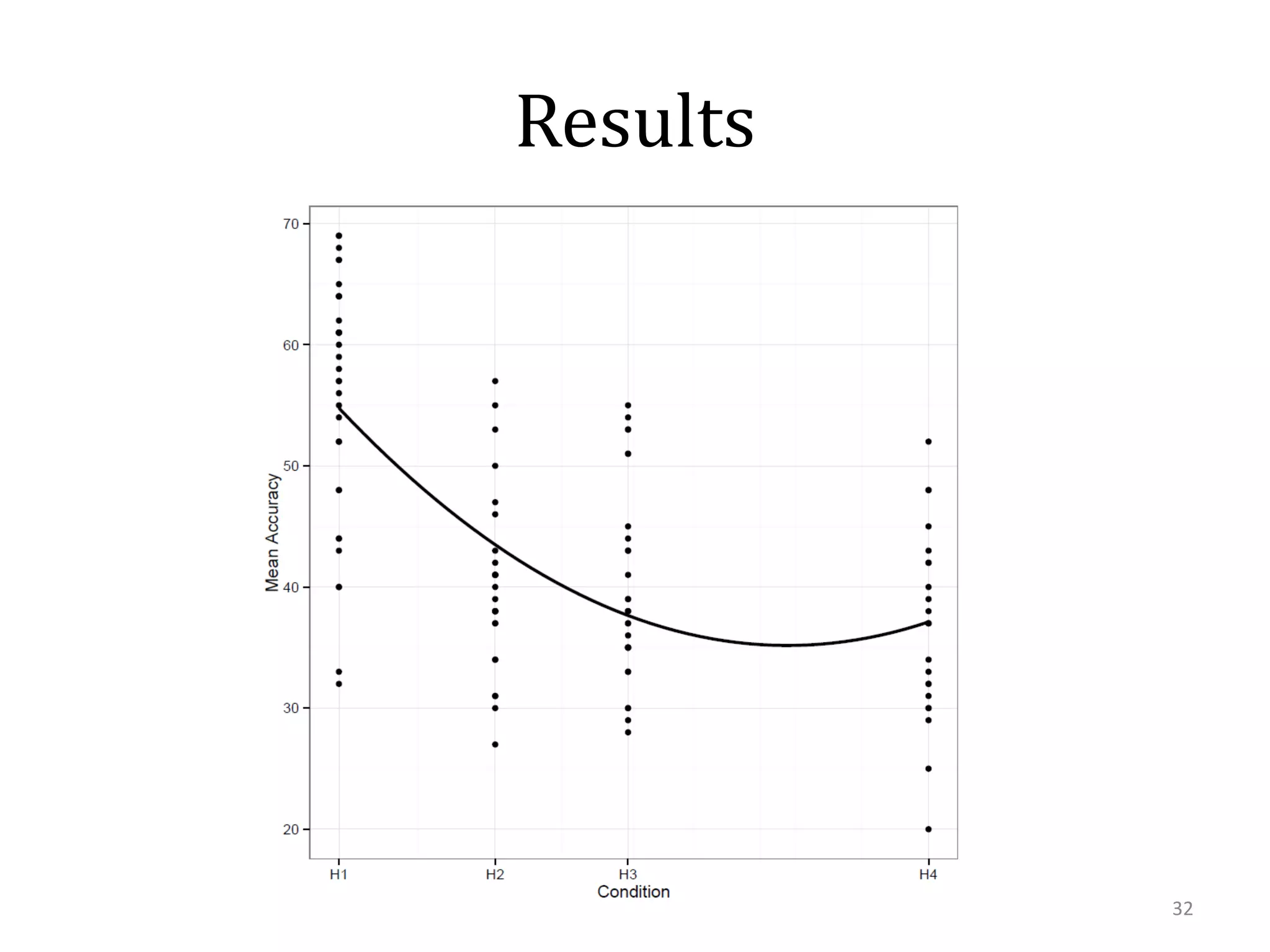

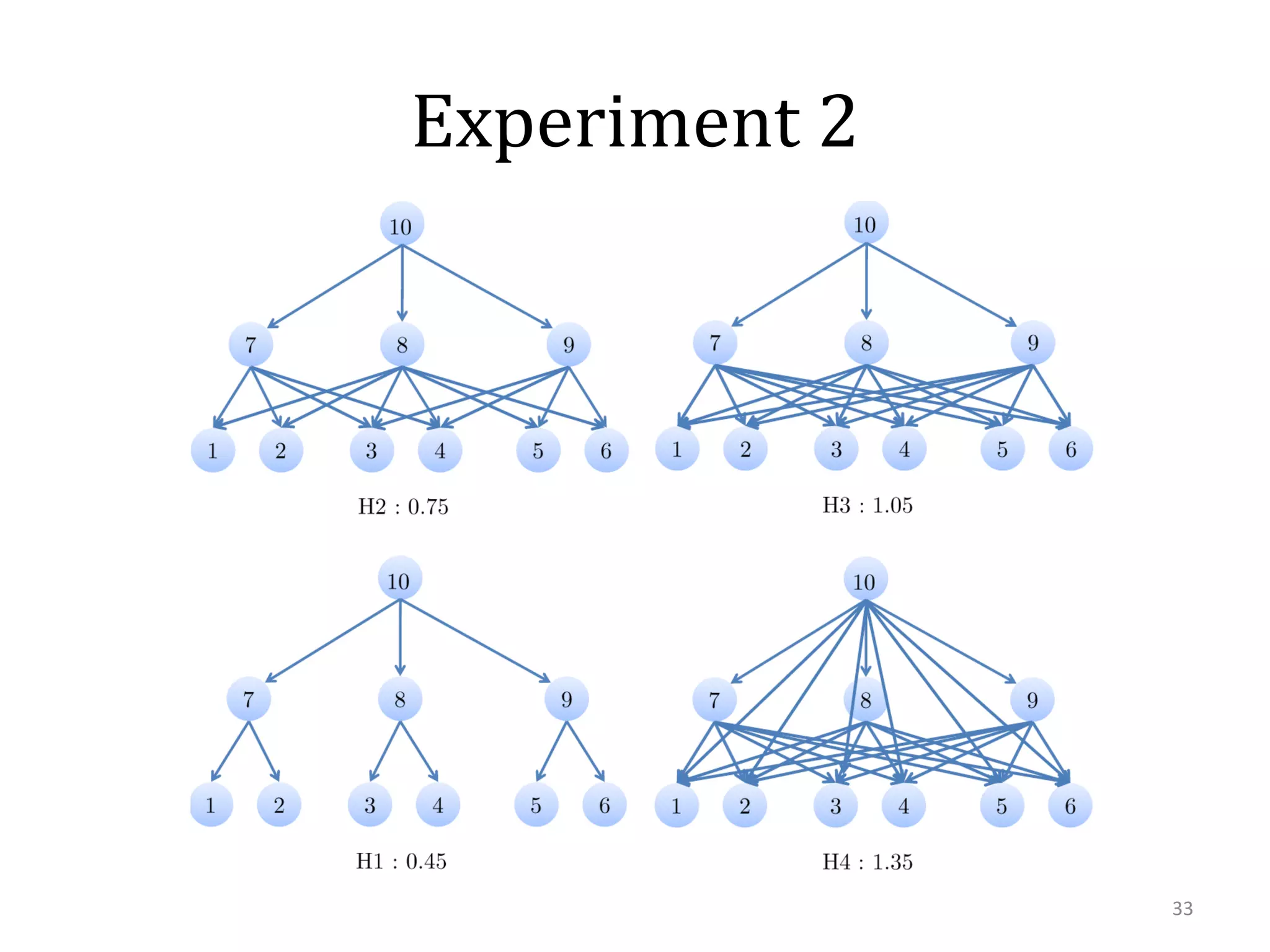

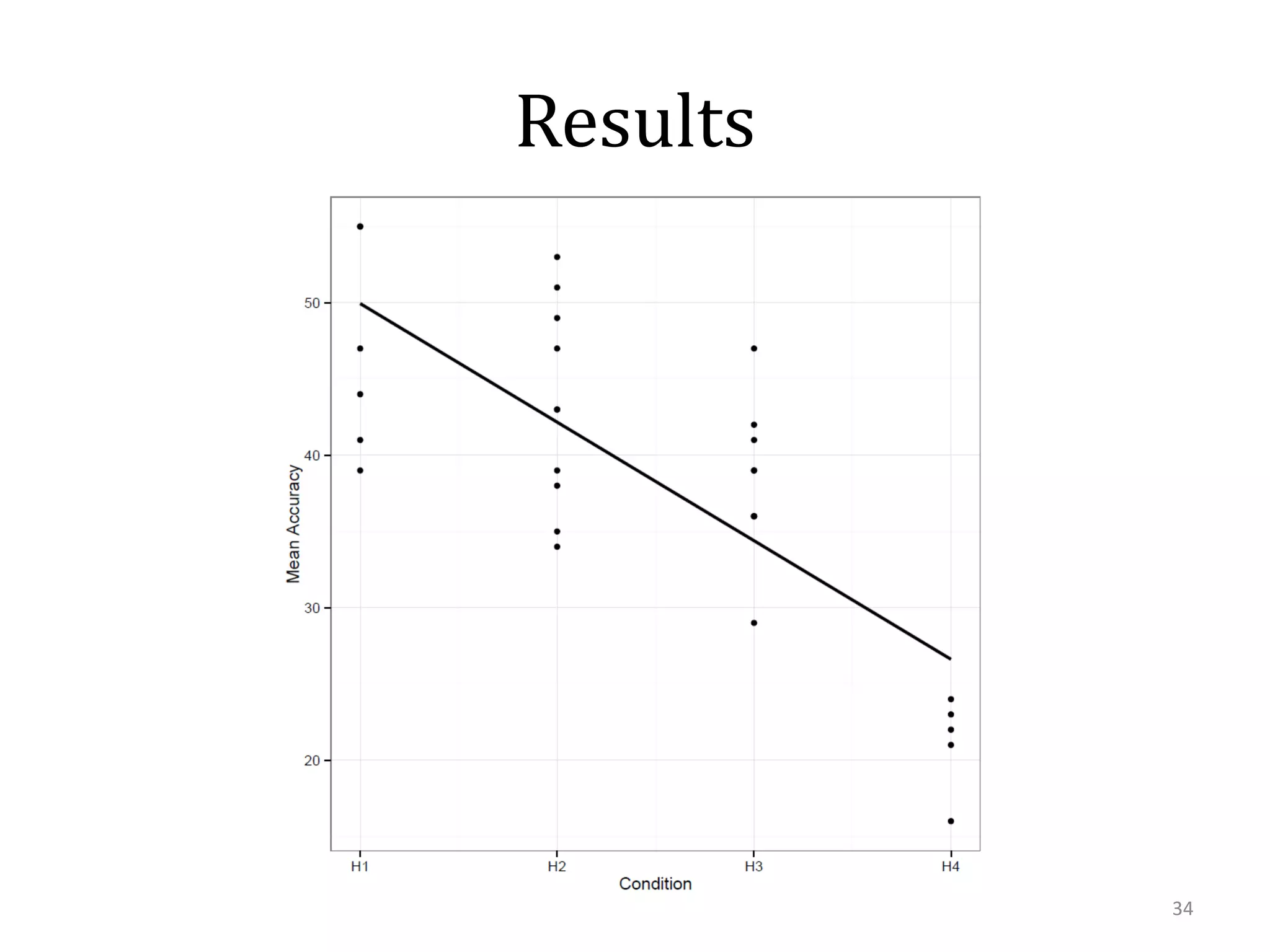

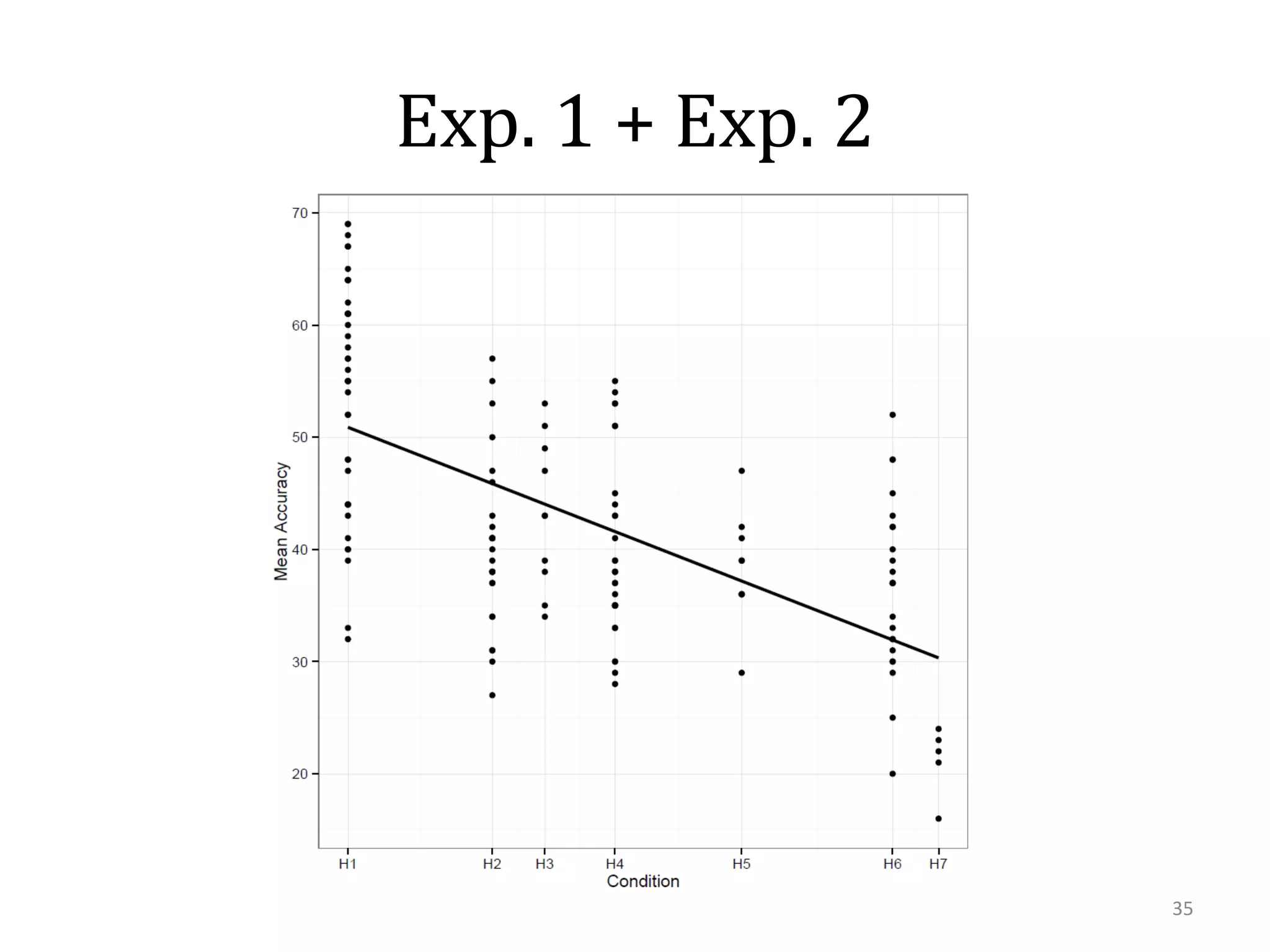

This document summarizes research on using similarity and structure for visual cognition and decision-making. It discusses how reducing dimensionality through techniques like PCA and autoencoders can build more invariant representations while lowering computational costs. Kernels are proposed to map data to a higher dimensional space where linear classifiers can be used, while avoiding high computational costs. Experiments on artificial scenes show how objects and their locations can be encoded using exemplars, and novel scenes classified based on familiar or novel elements. Further work aims to model natural scenes and object hierarchies using a graph structure approach.