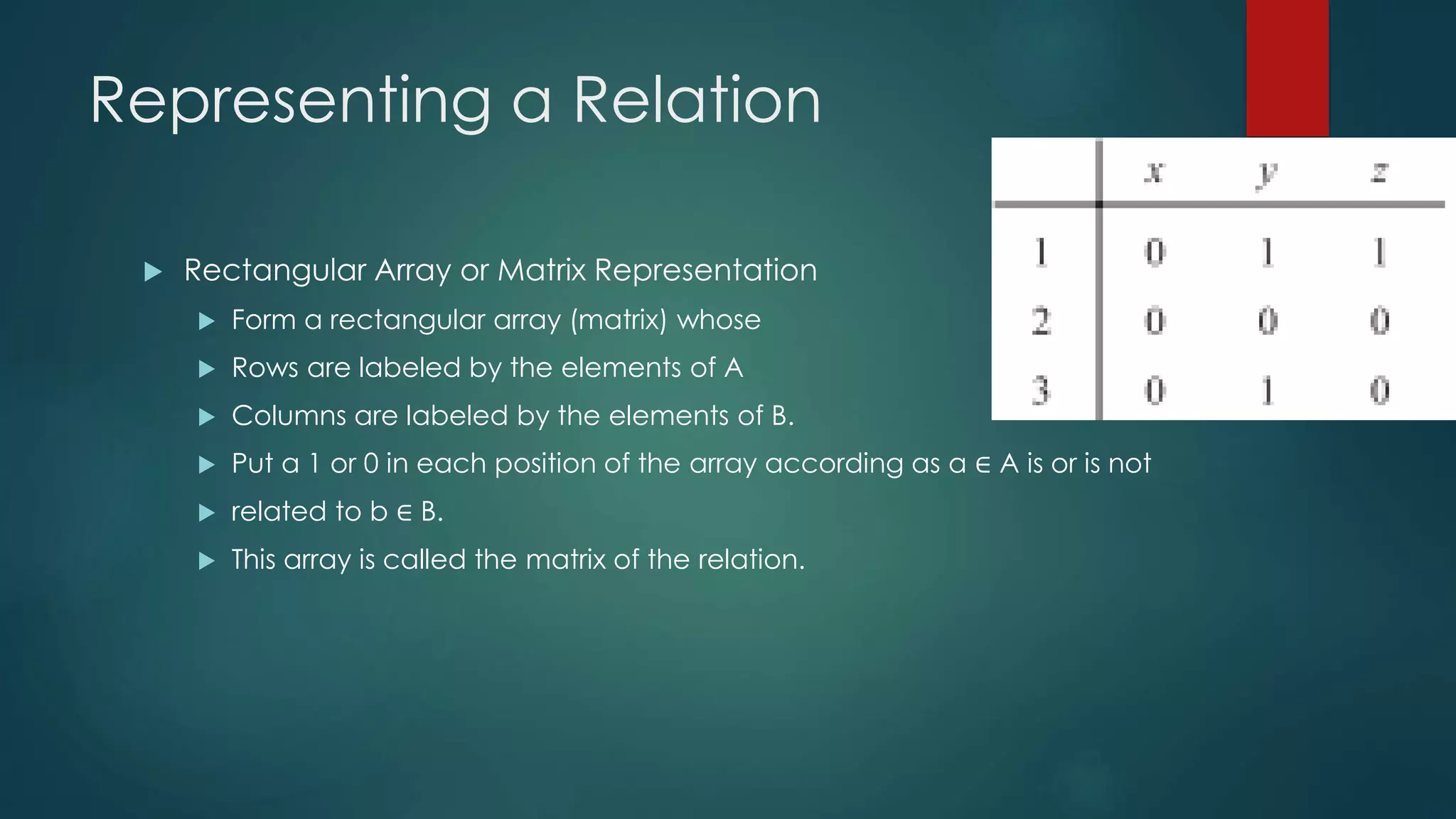

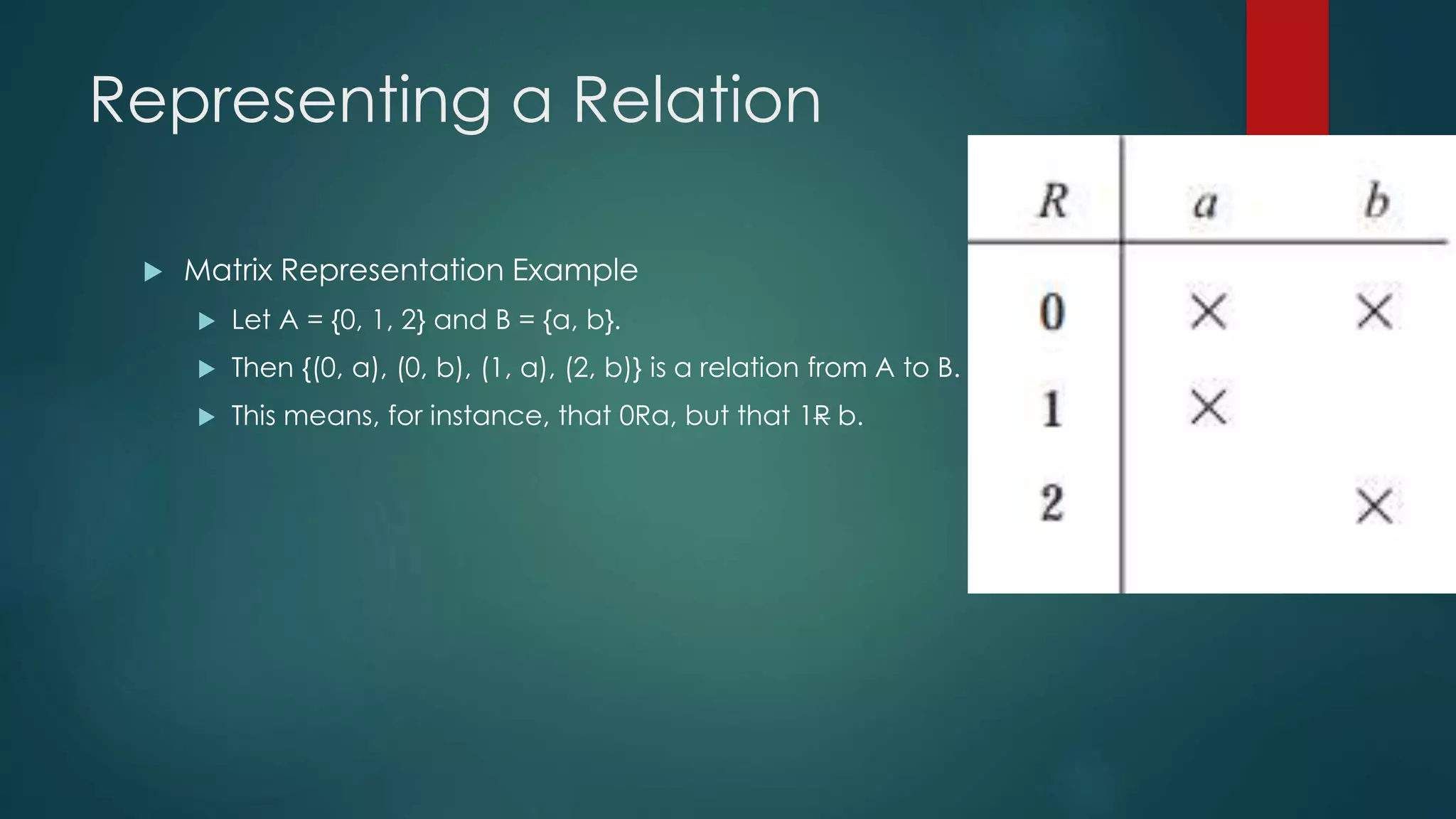

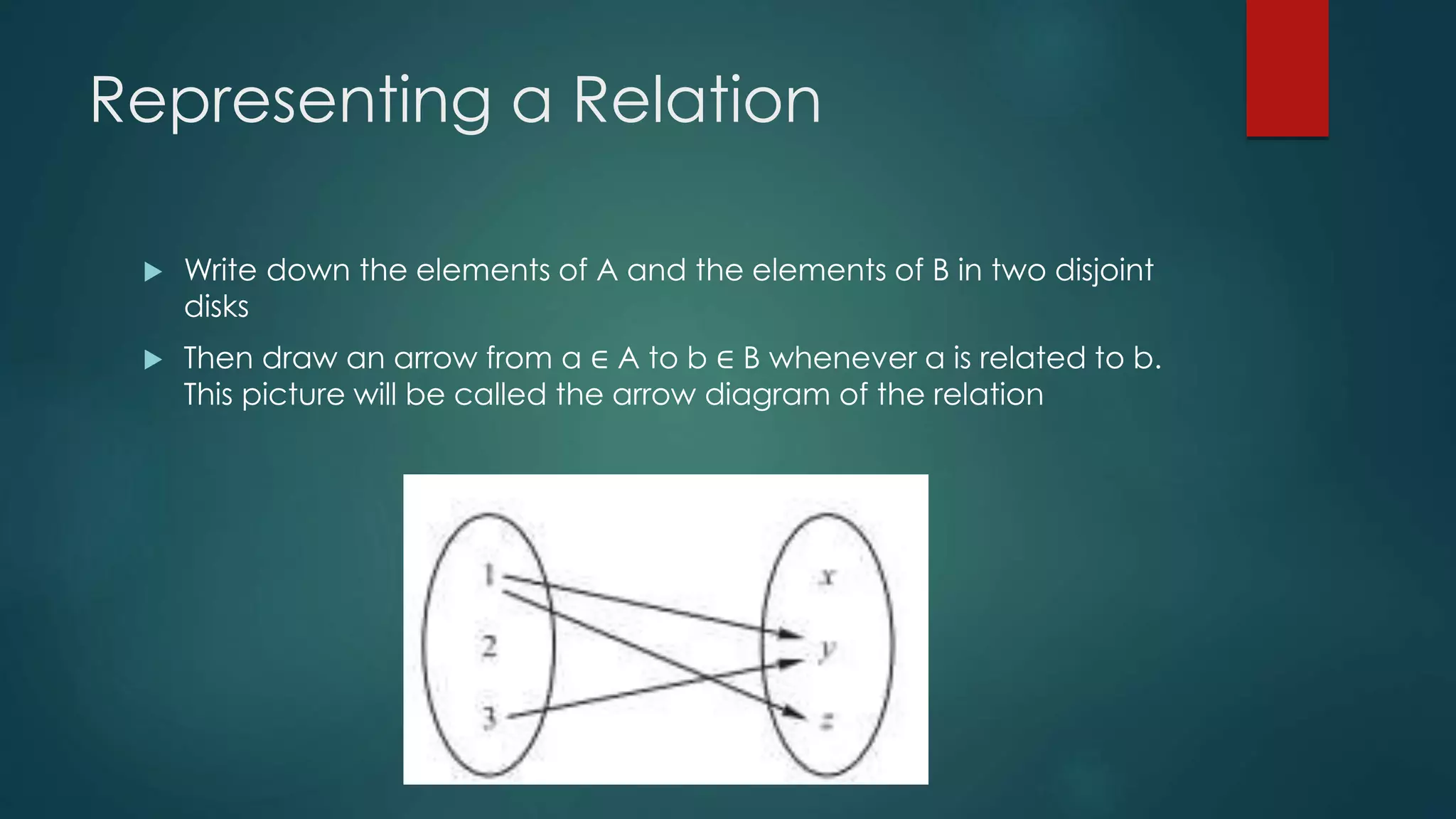

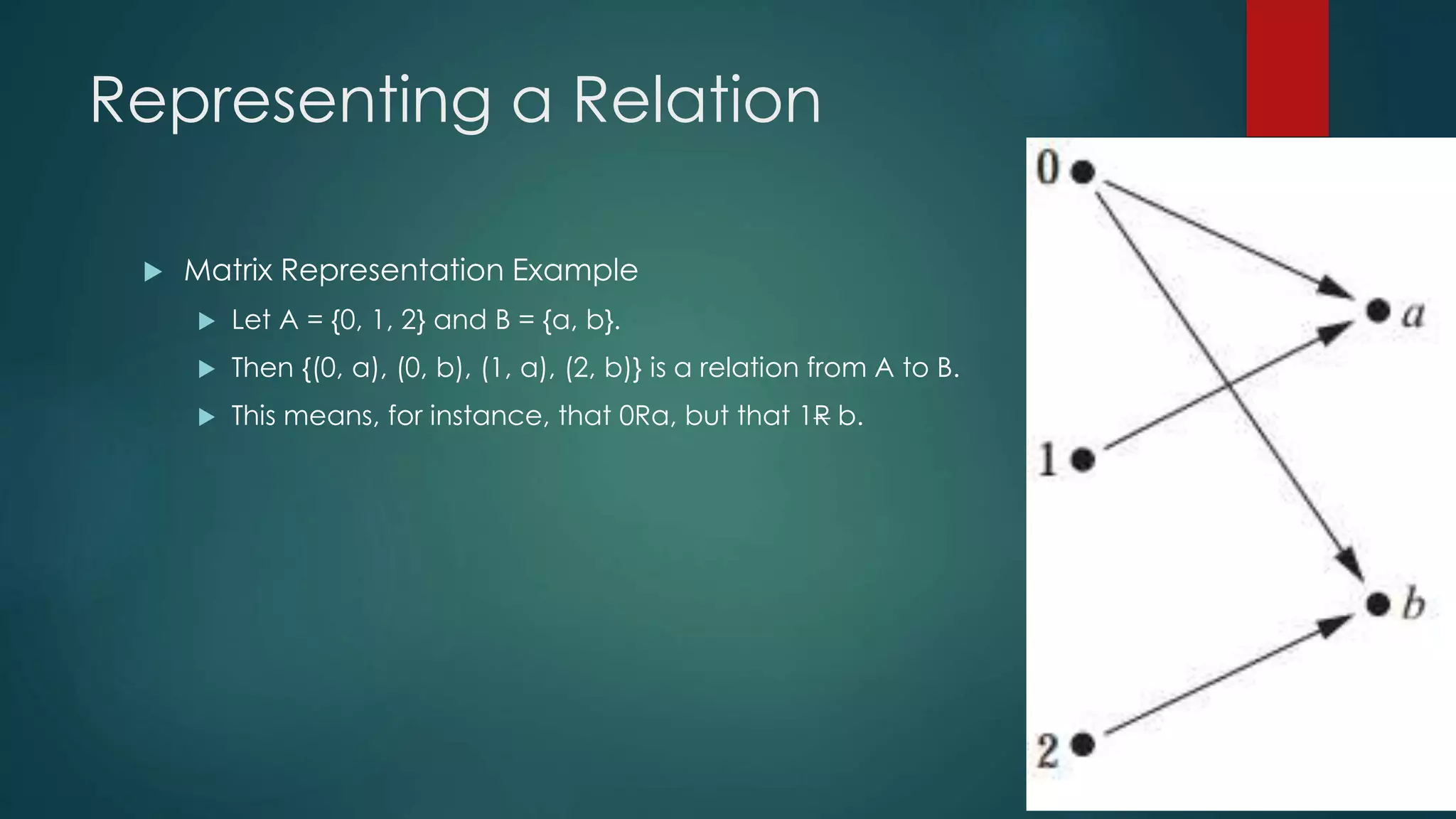

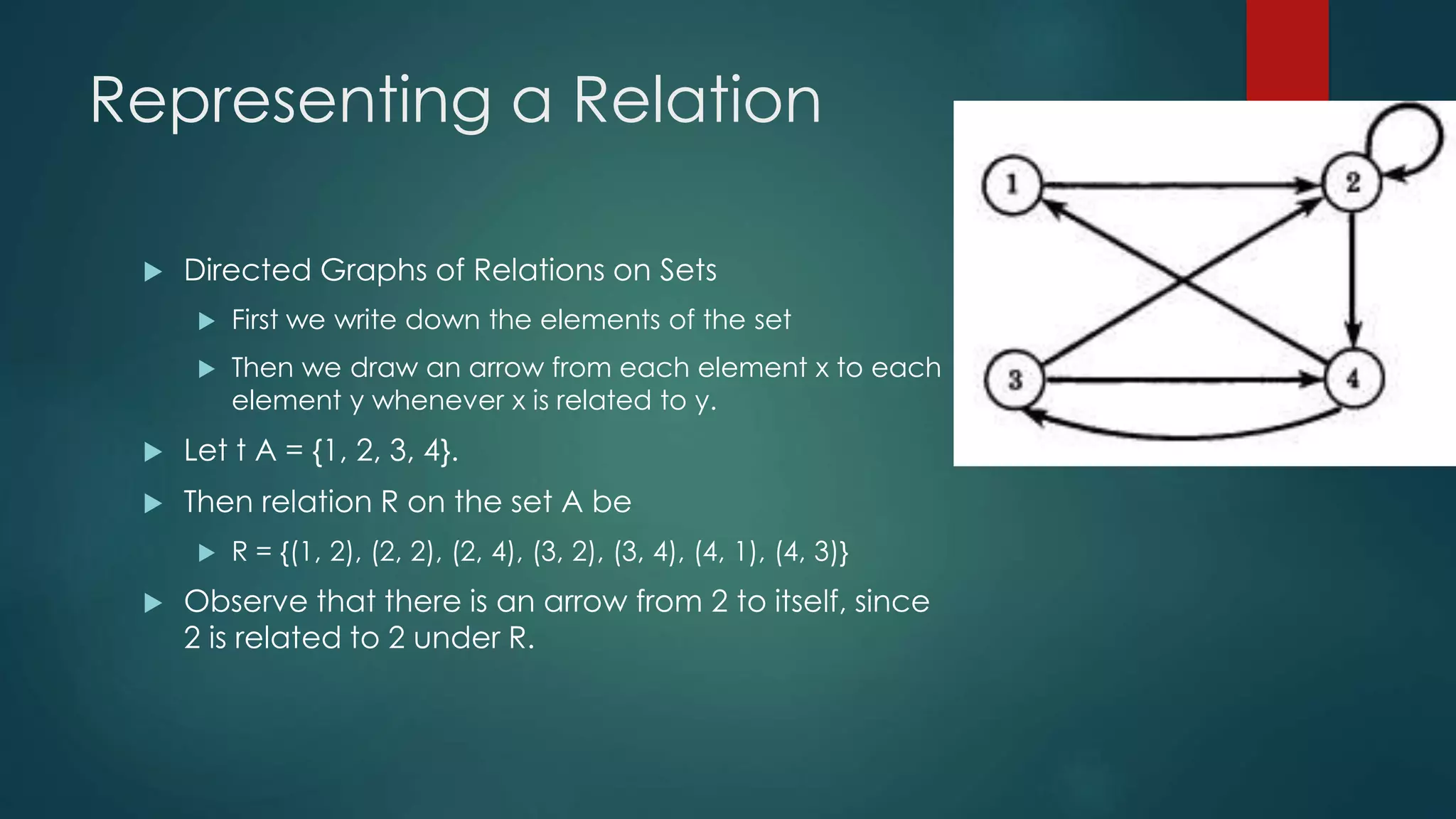

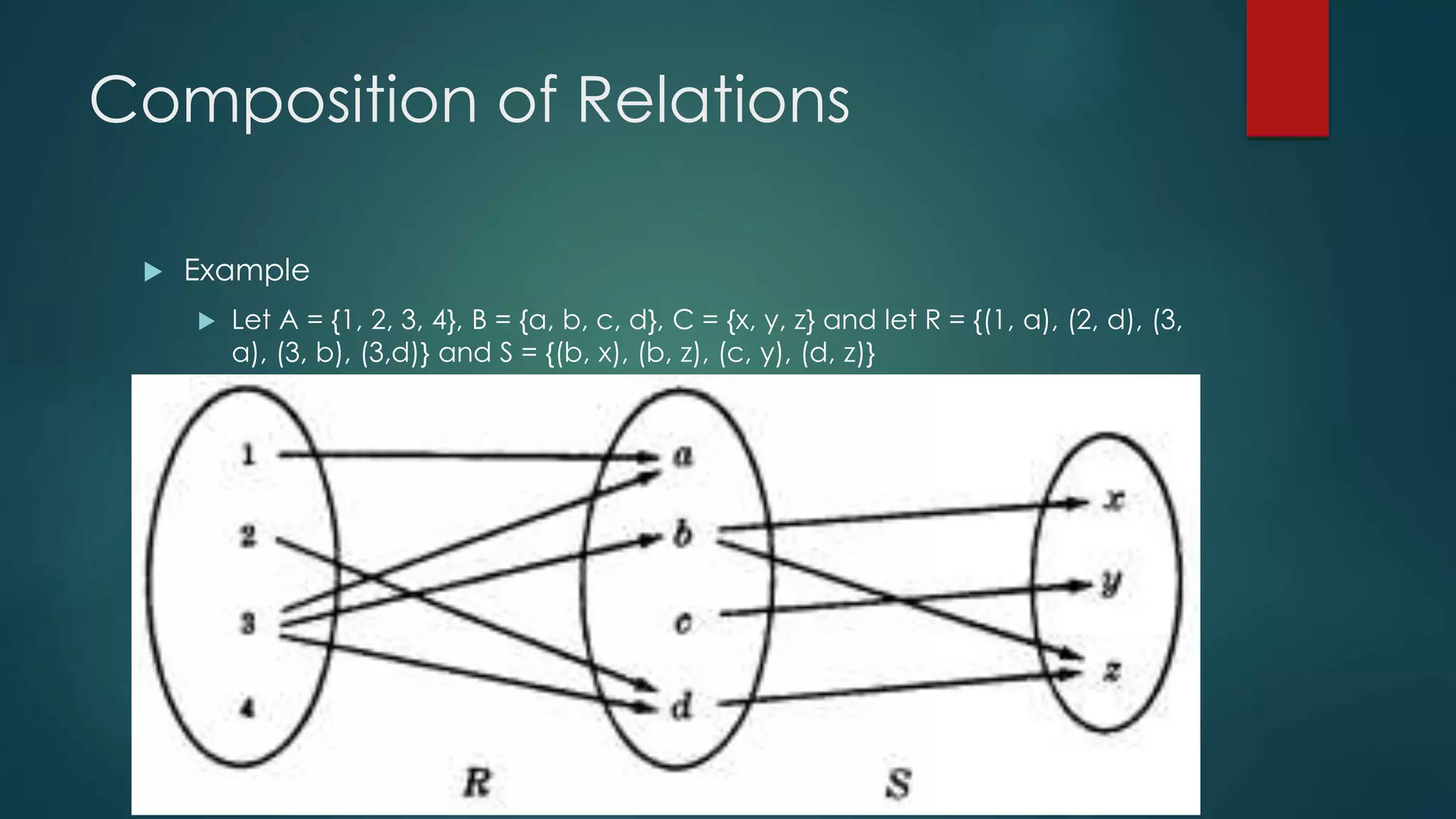

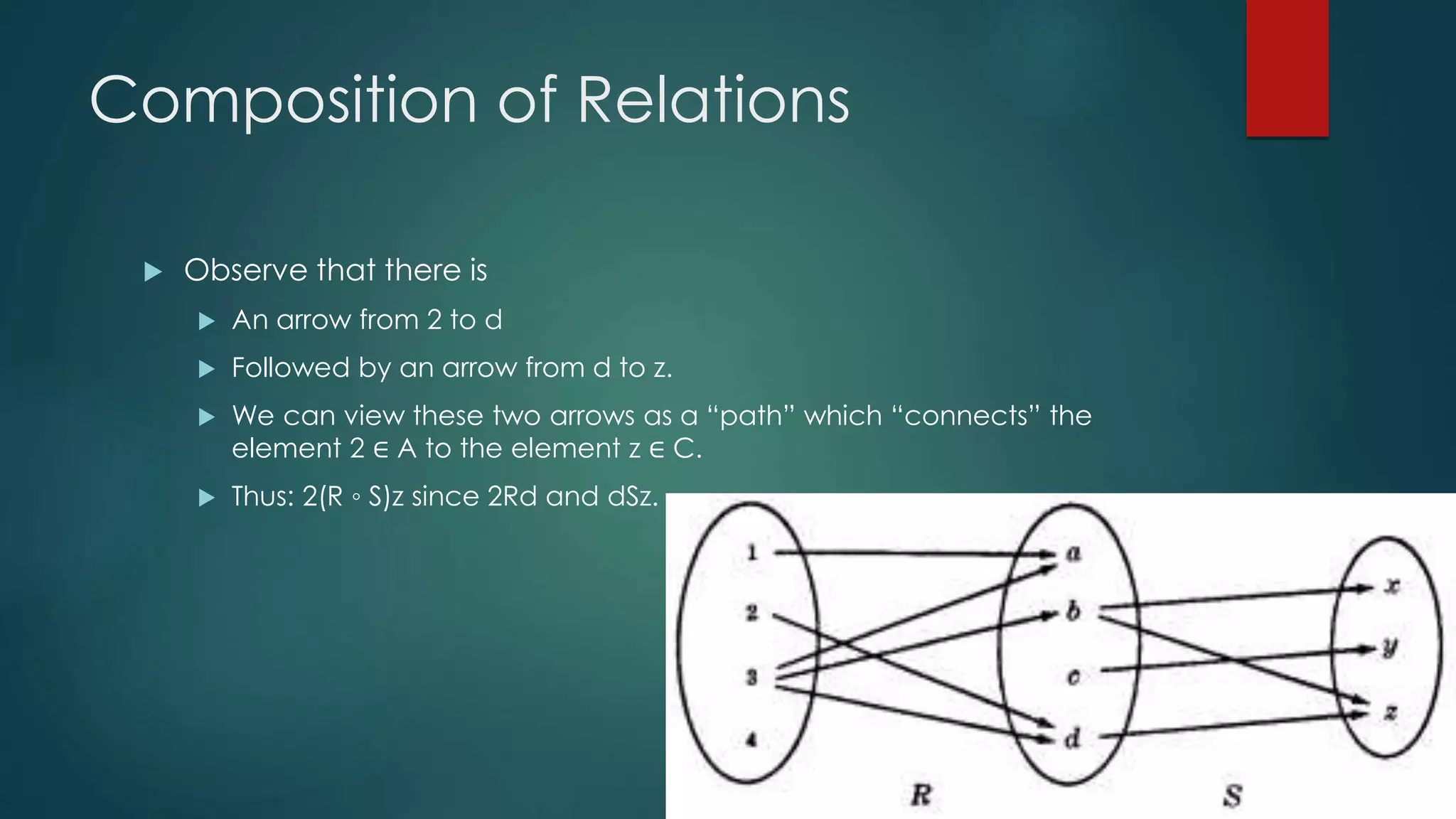

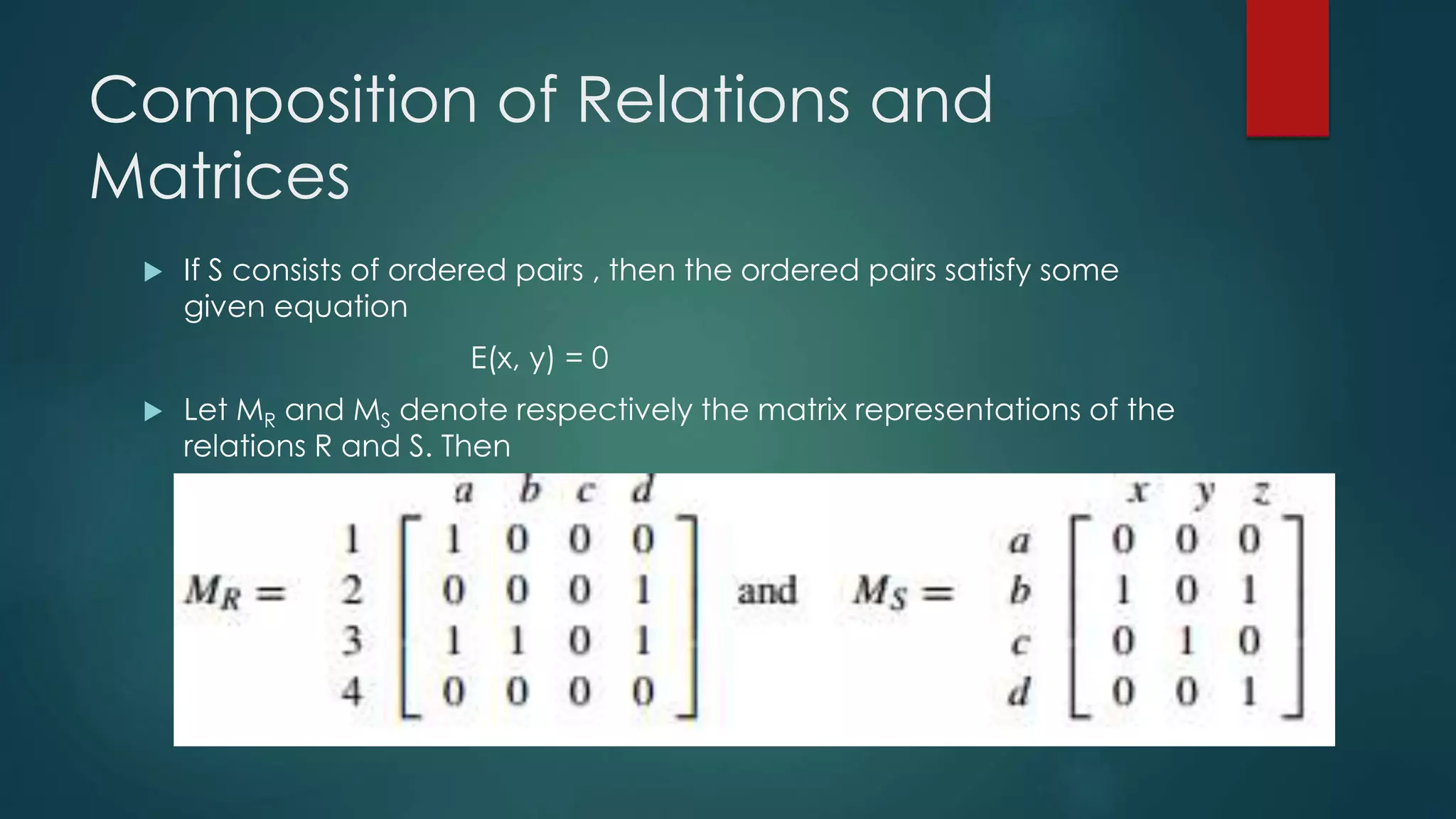

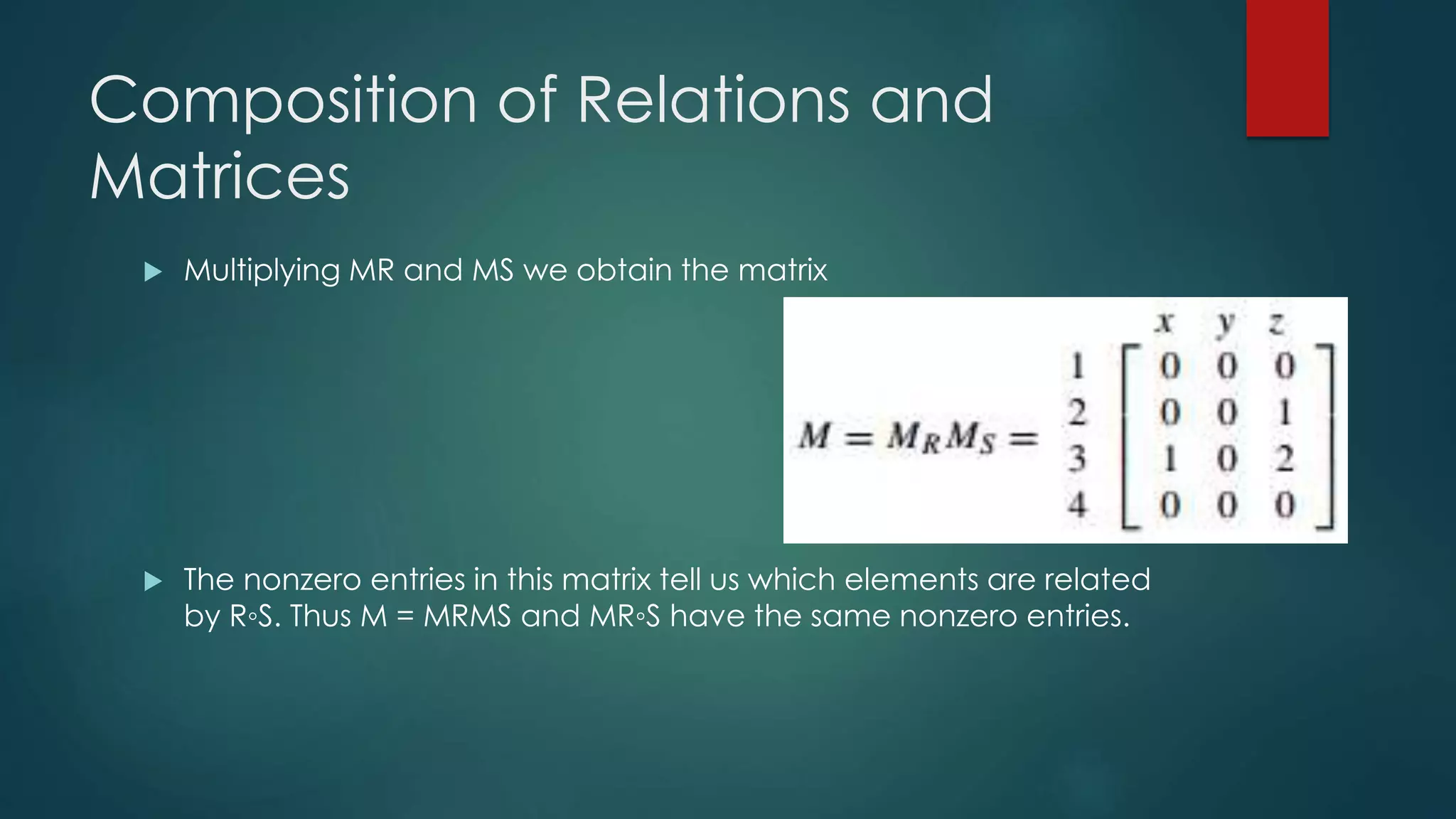

The document discusses different types of relations between elements of sets. It defines relations as subsets of Cartesian products of sets and describes how relations can be represented using matrices or directed graphs. It then introduces various properties of relations such as reflexive, symmetric, transitive, and defines what it means for a relation to have each property. Composition of relations is also covered, along with how relation composition can be represented by matrix multiplication.