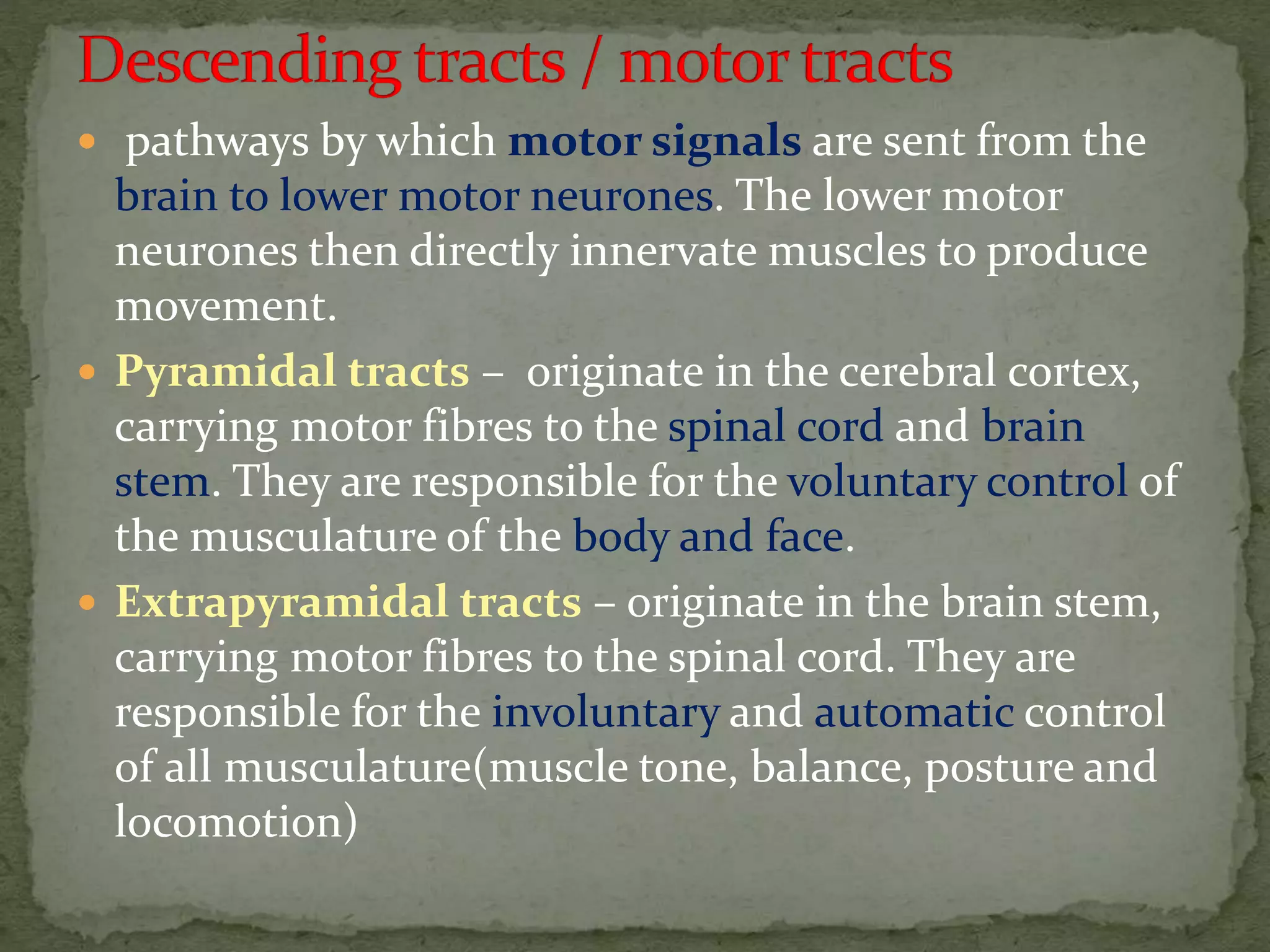

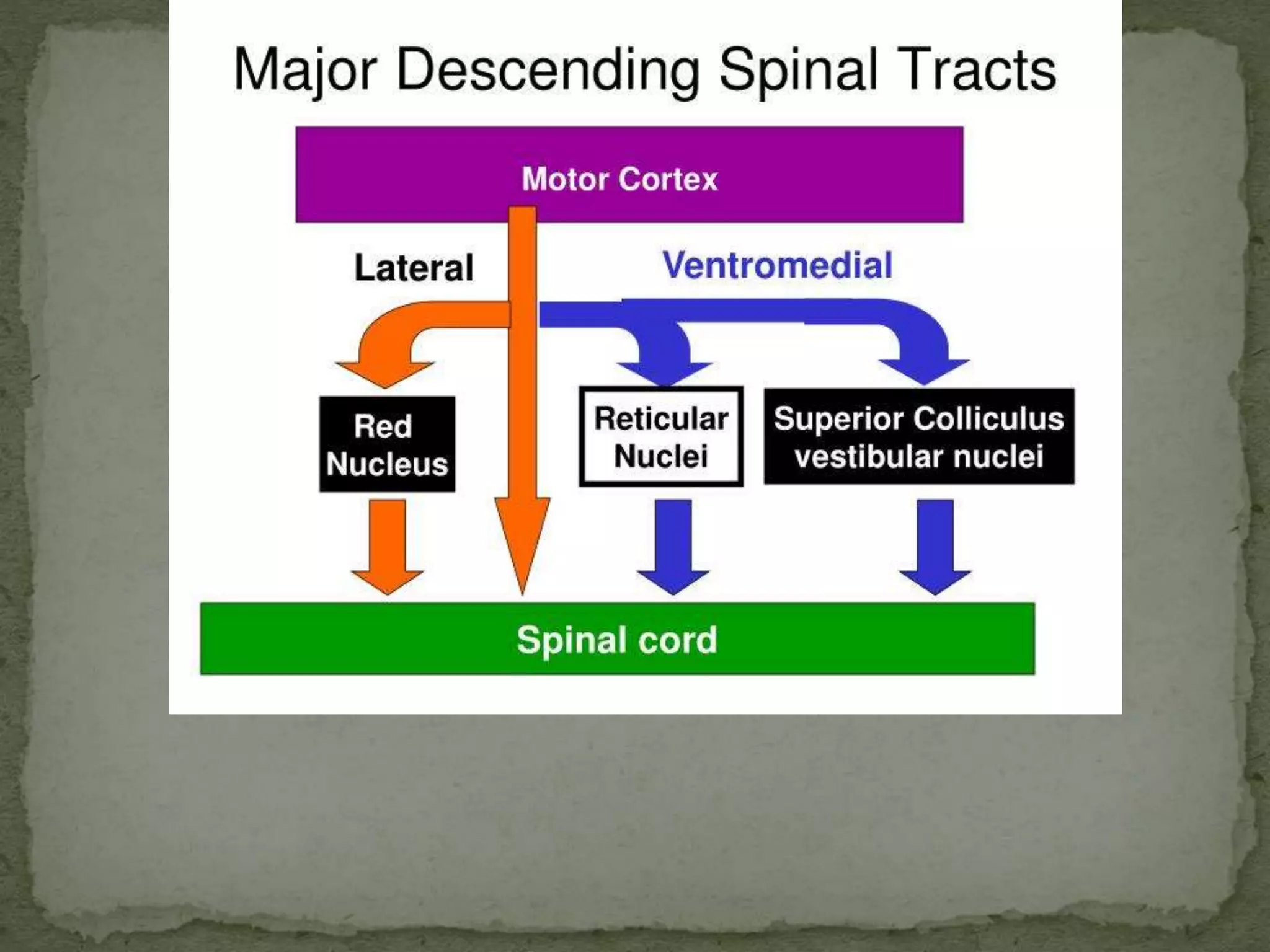

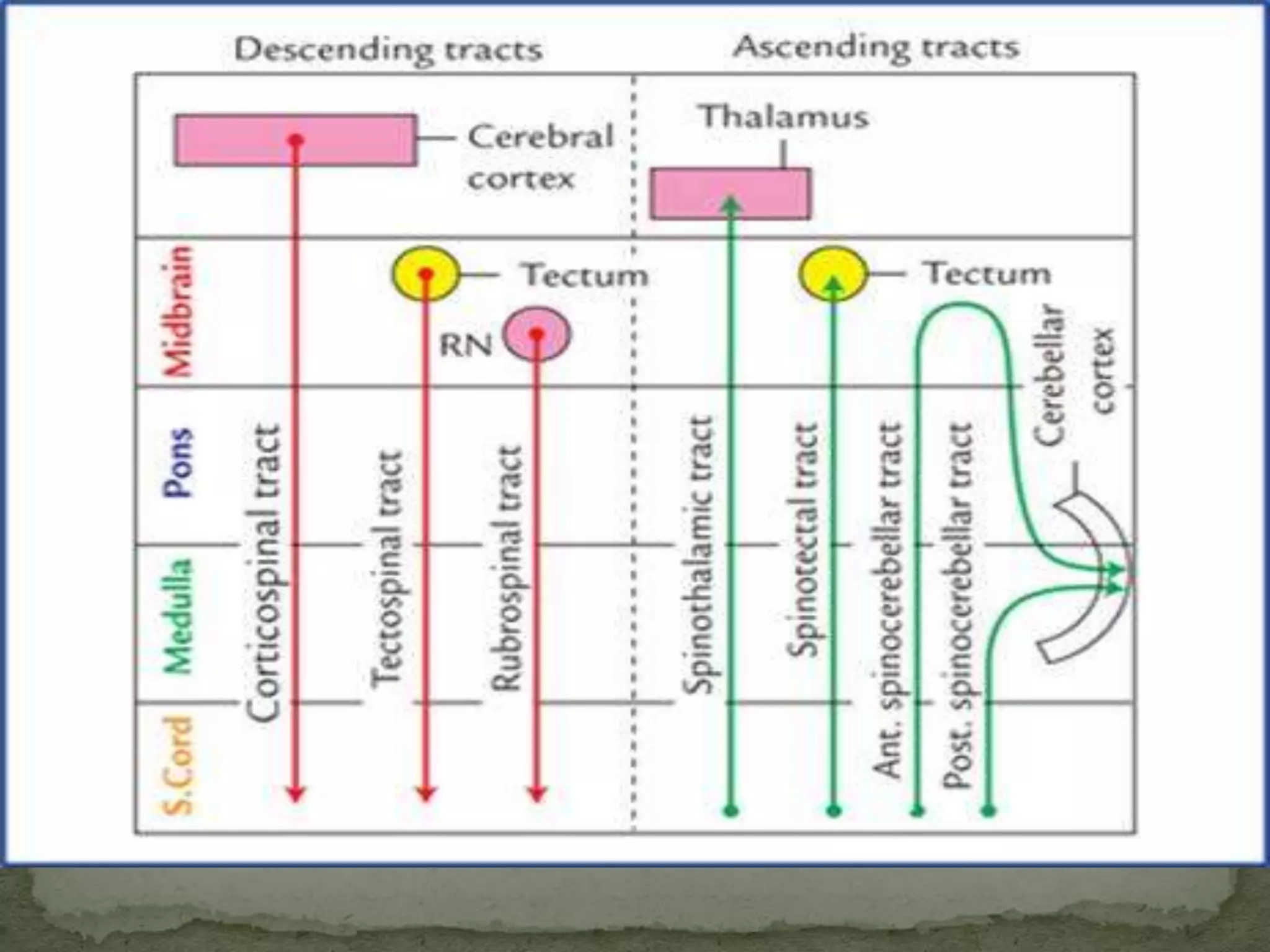

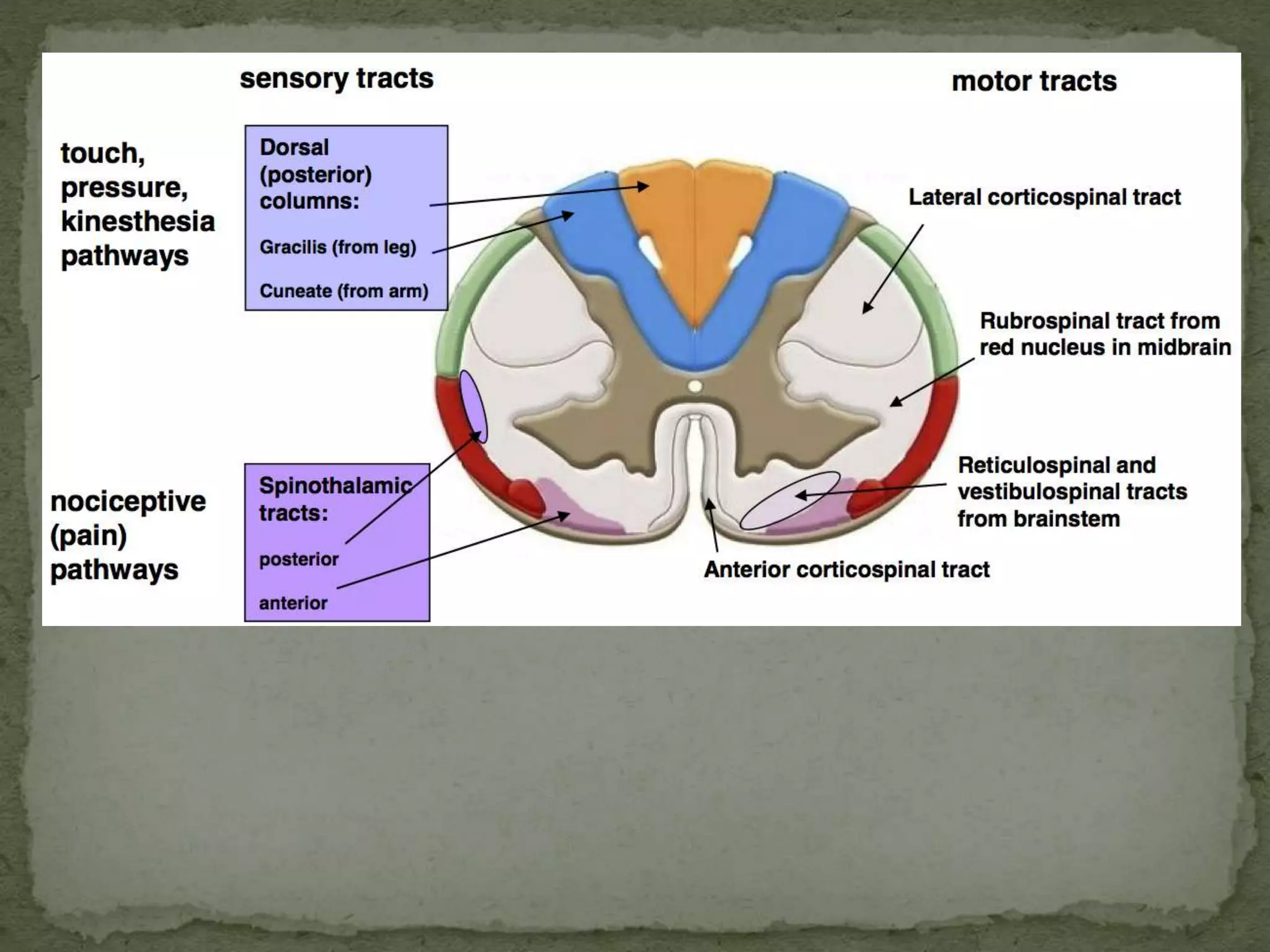

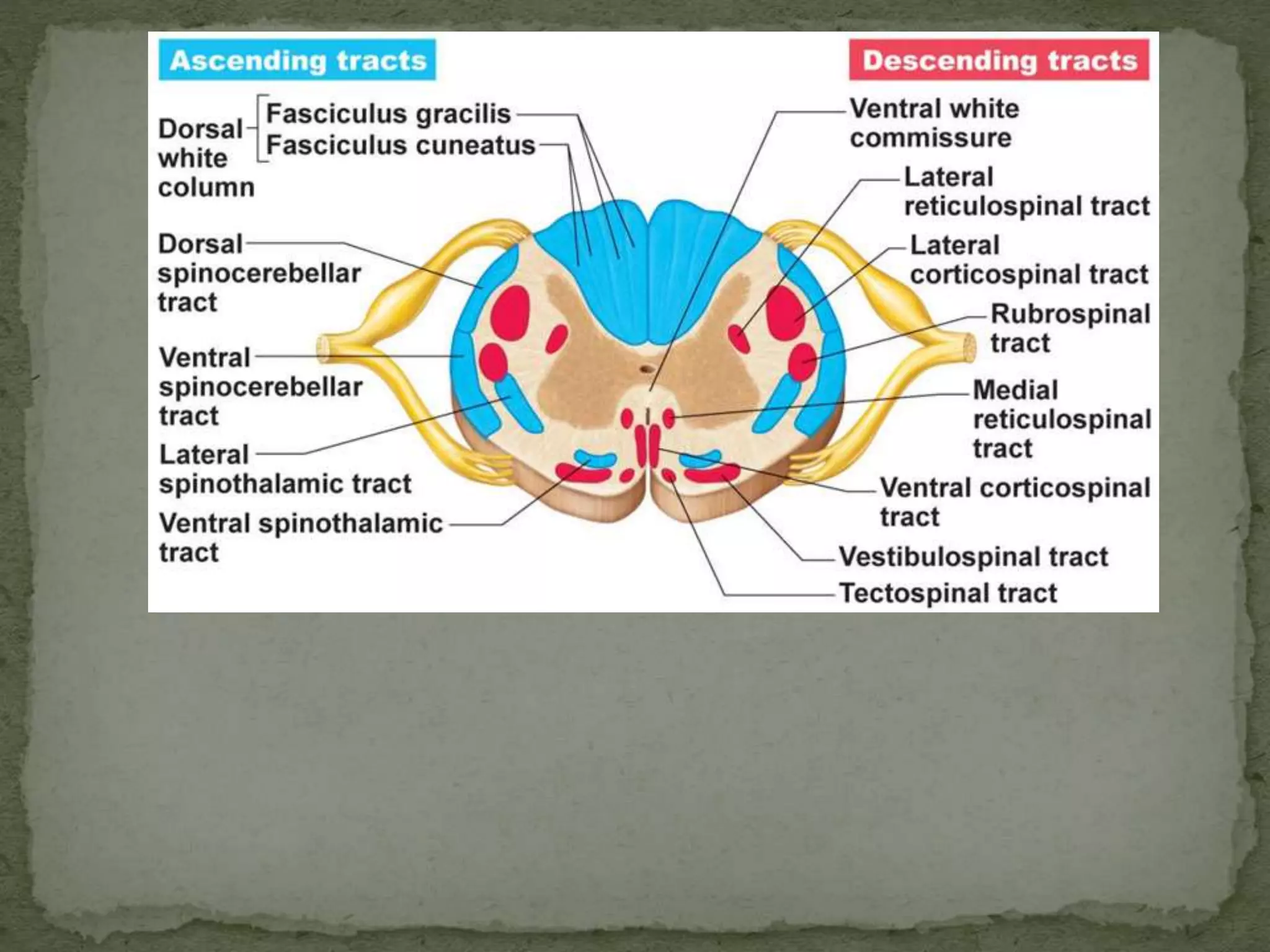

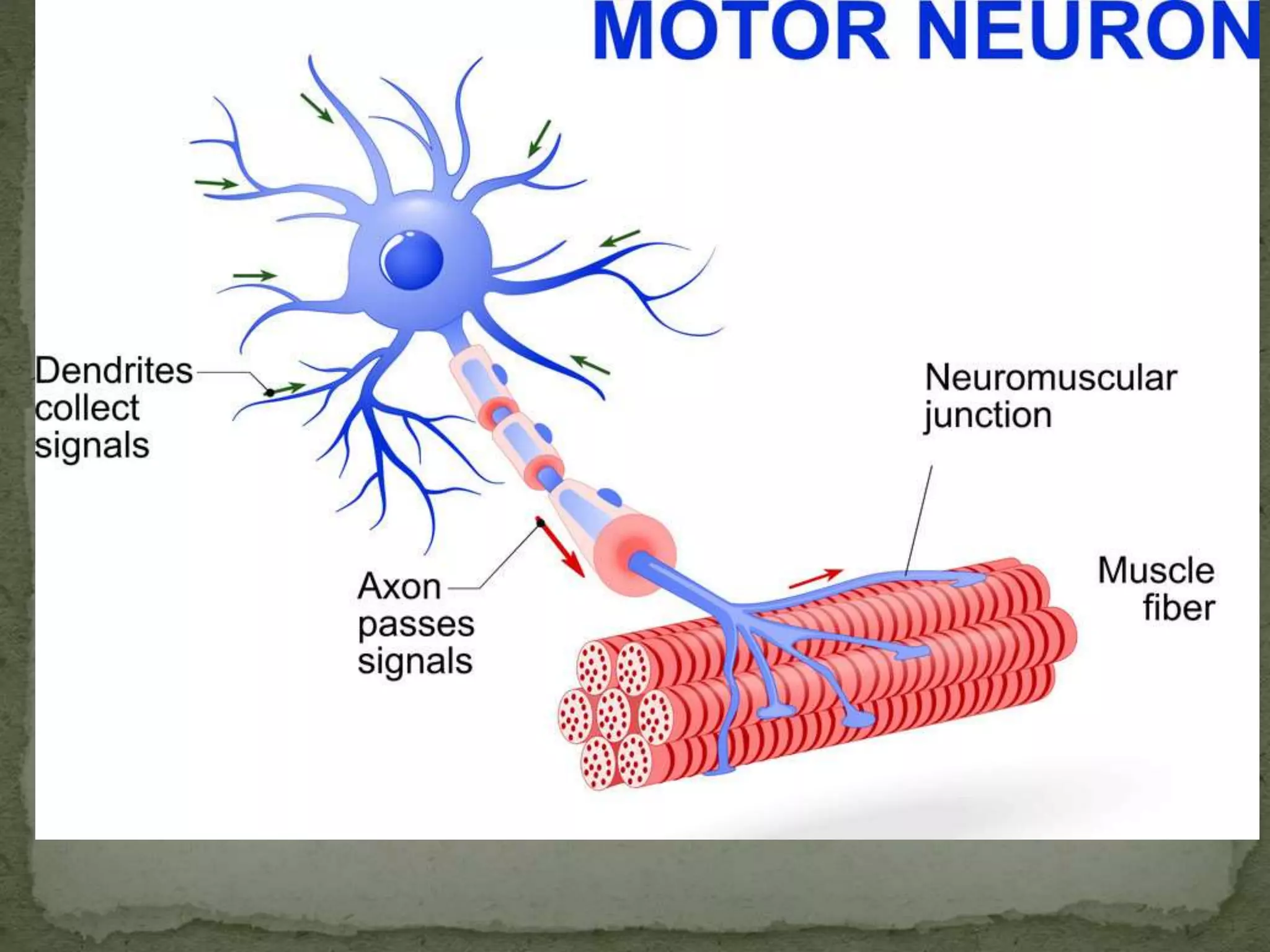

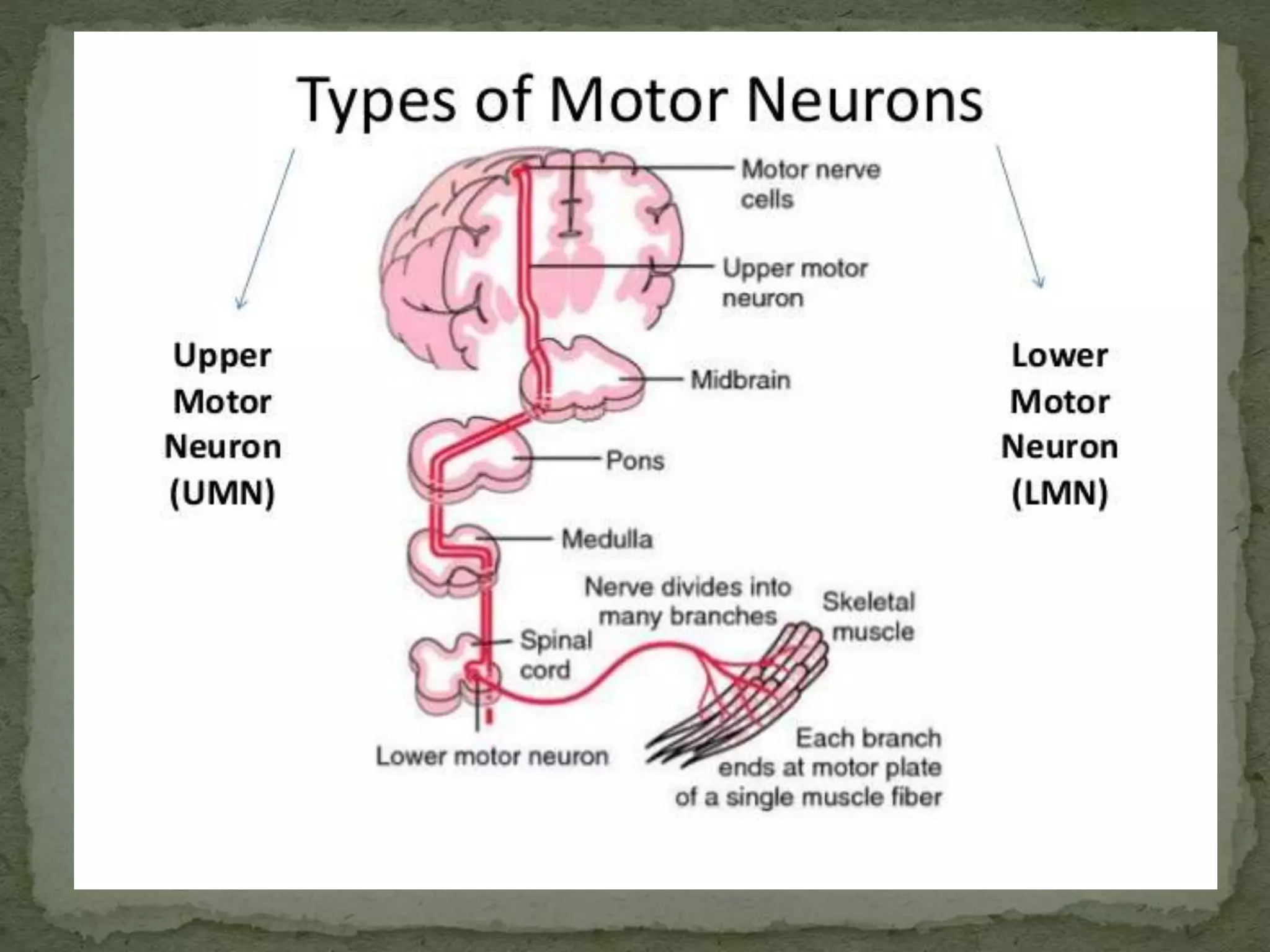

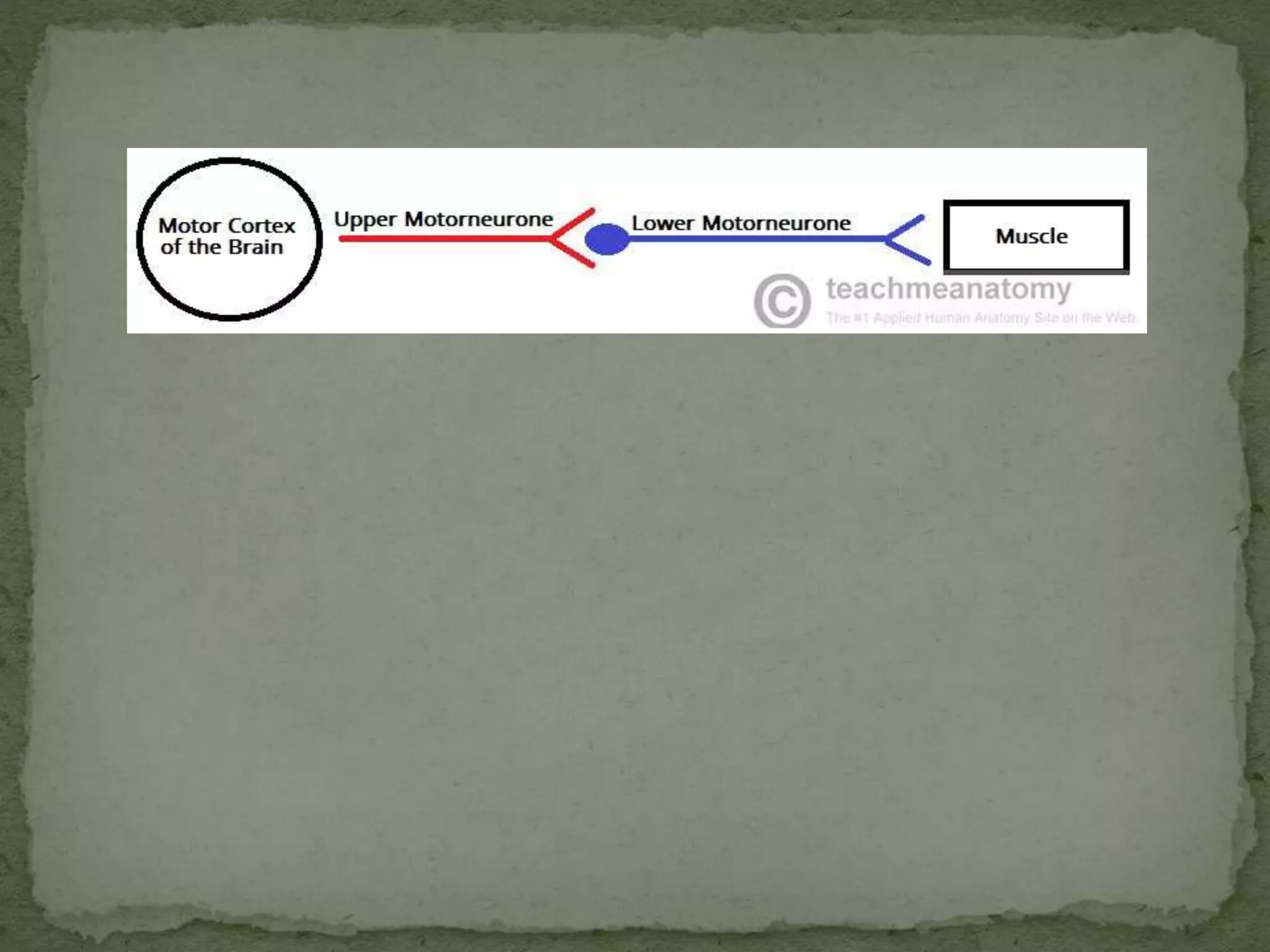

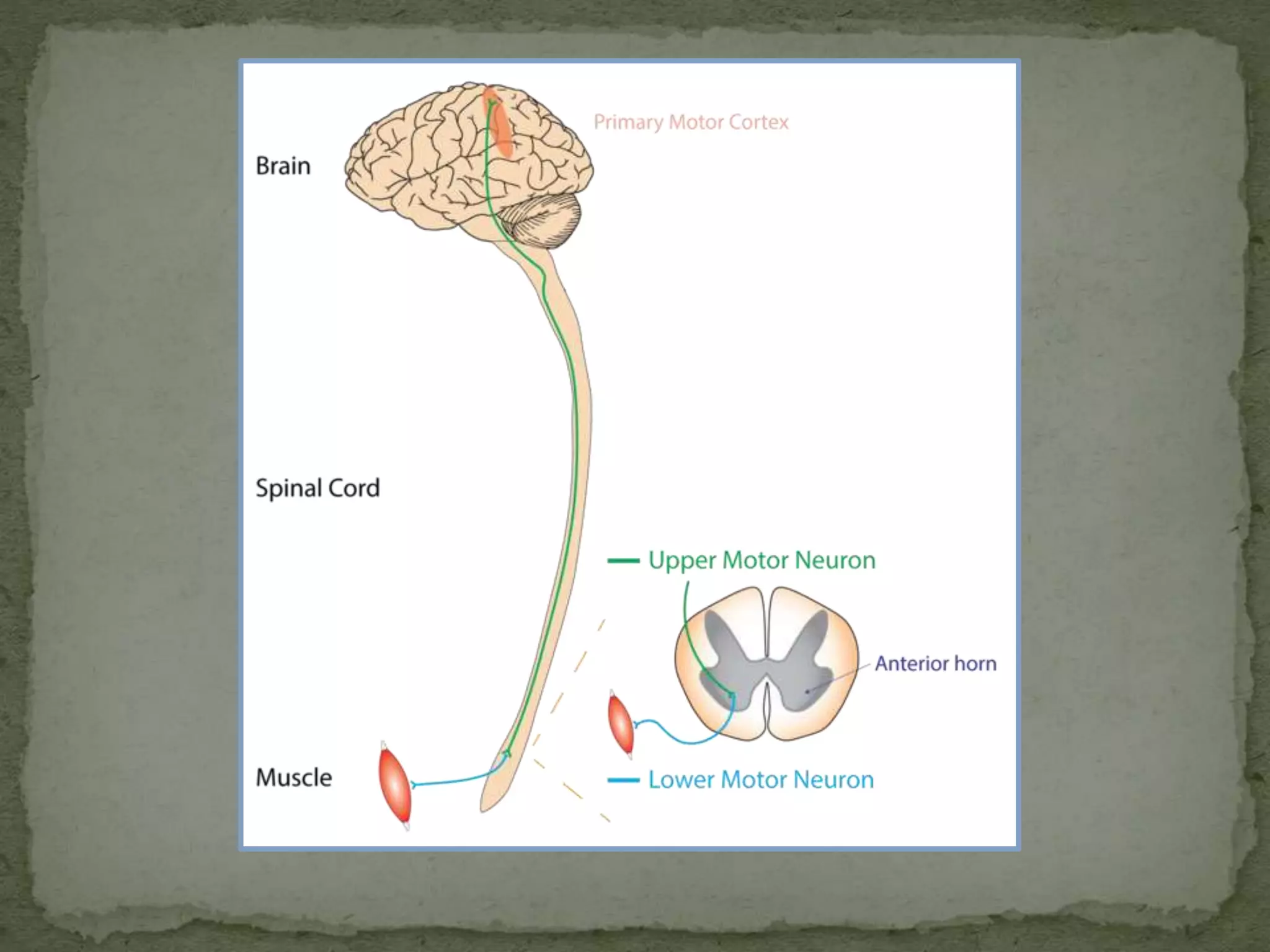

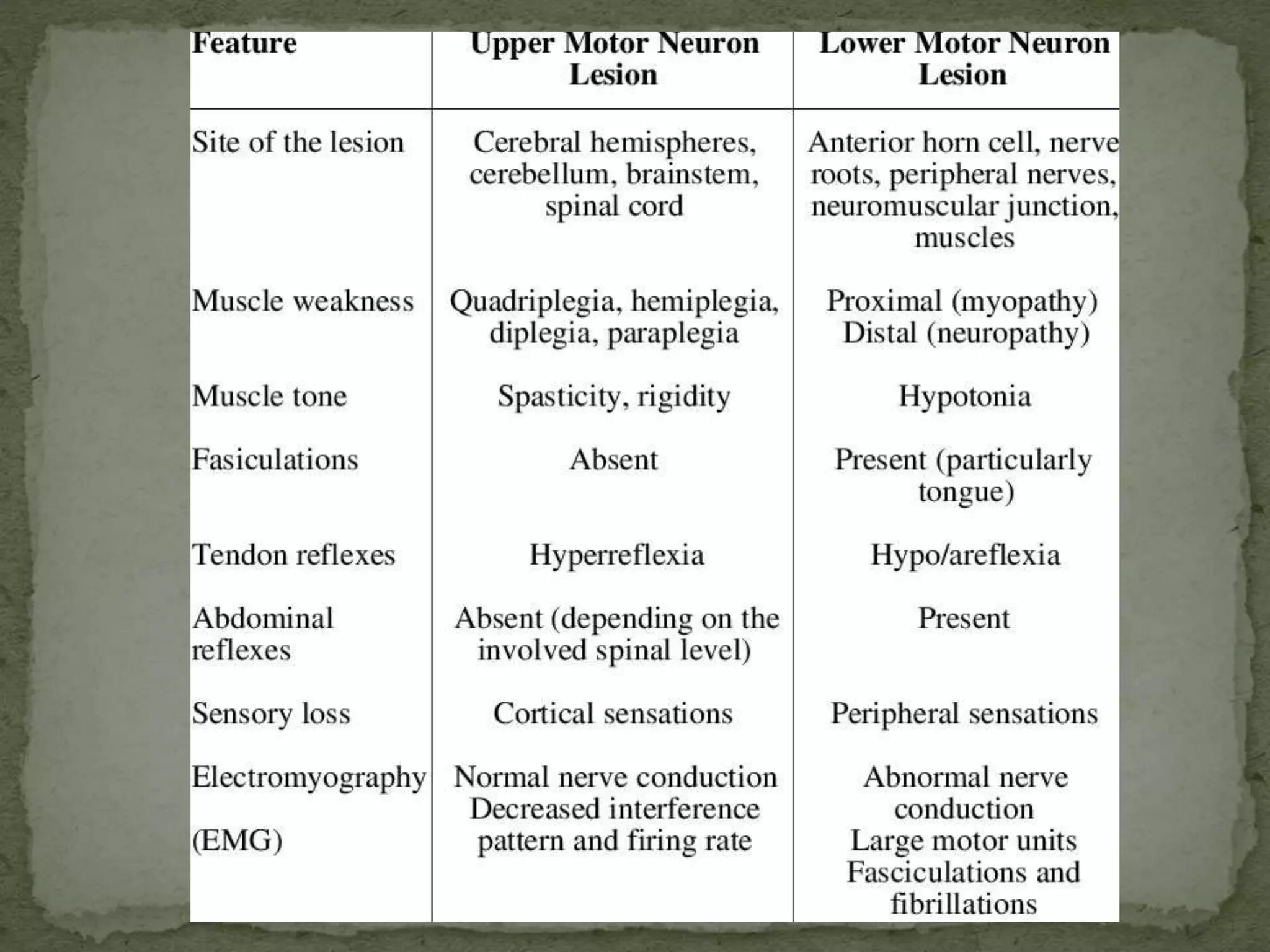

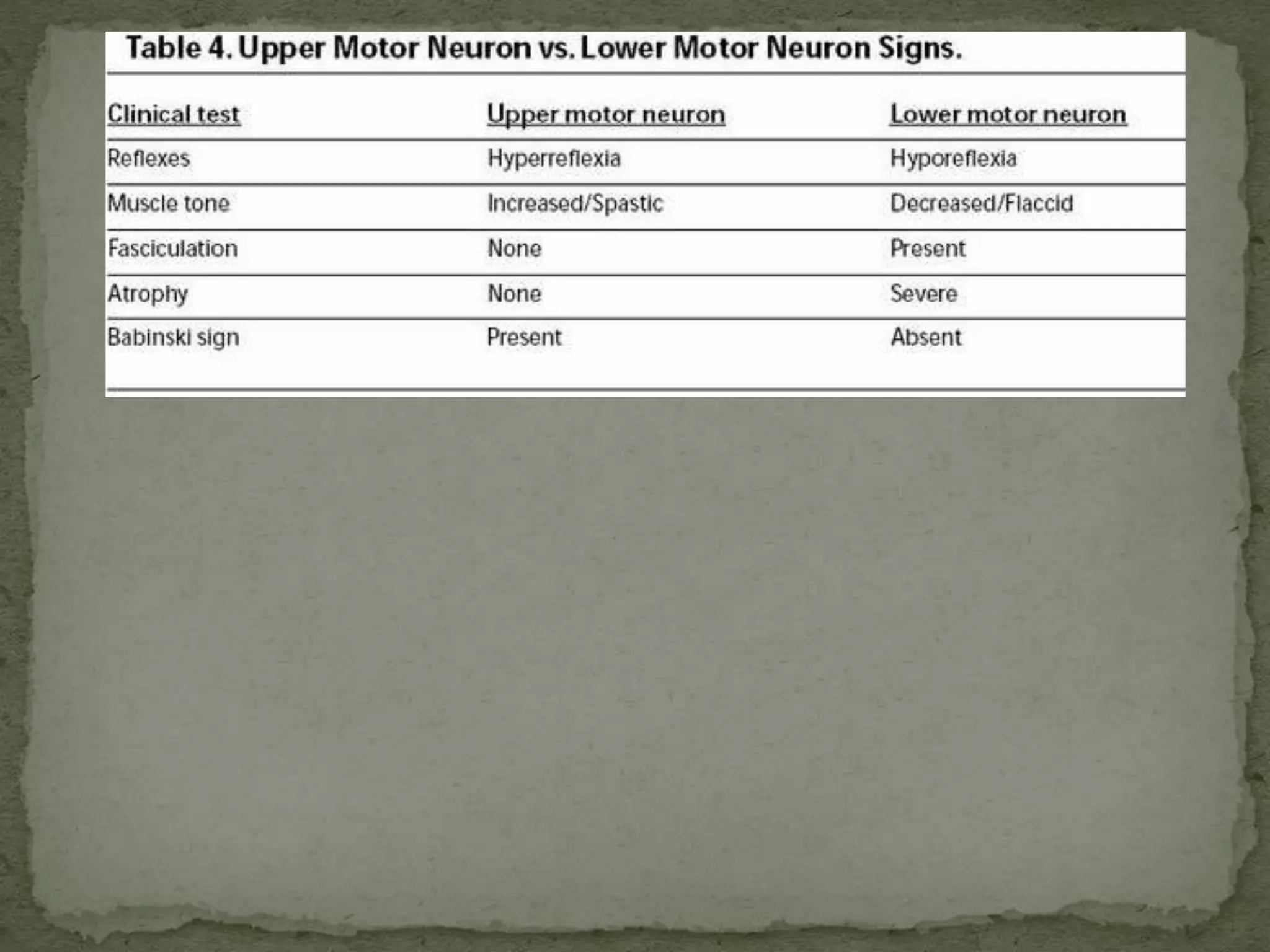

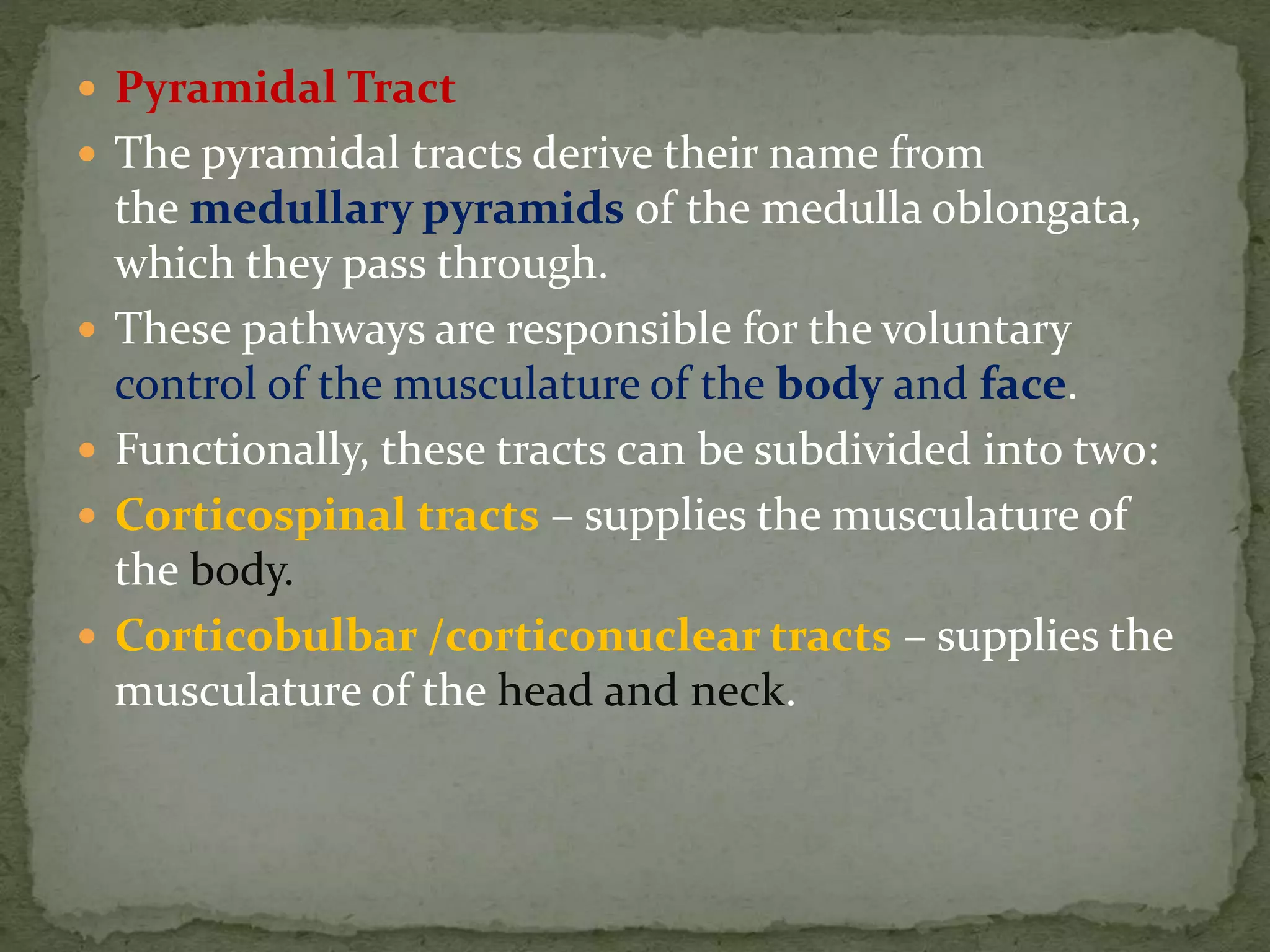

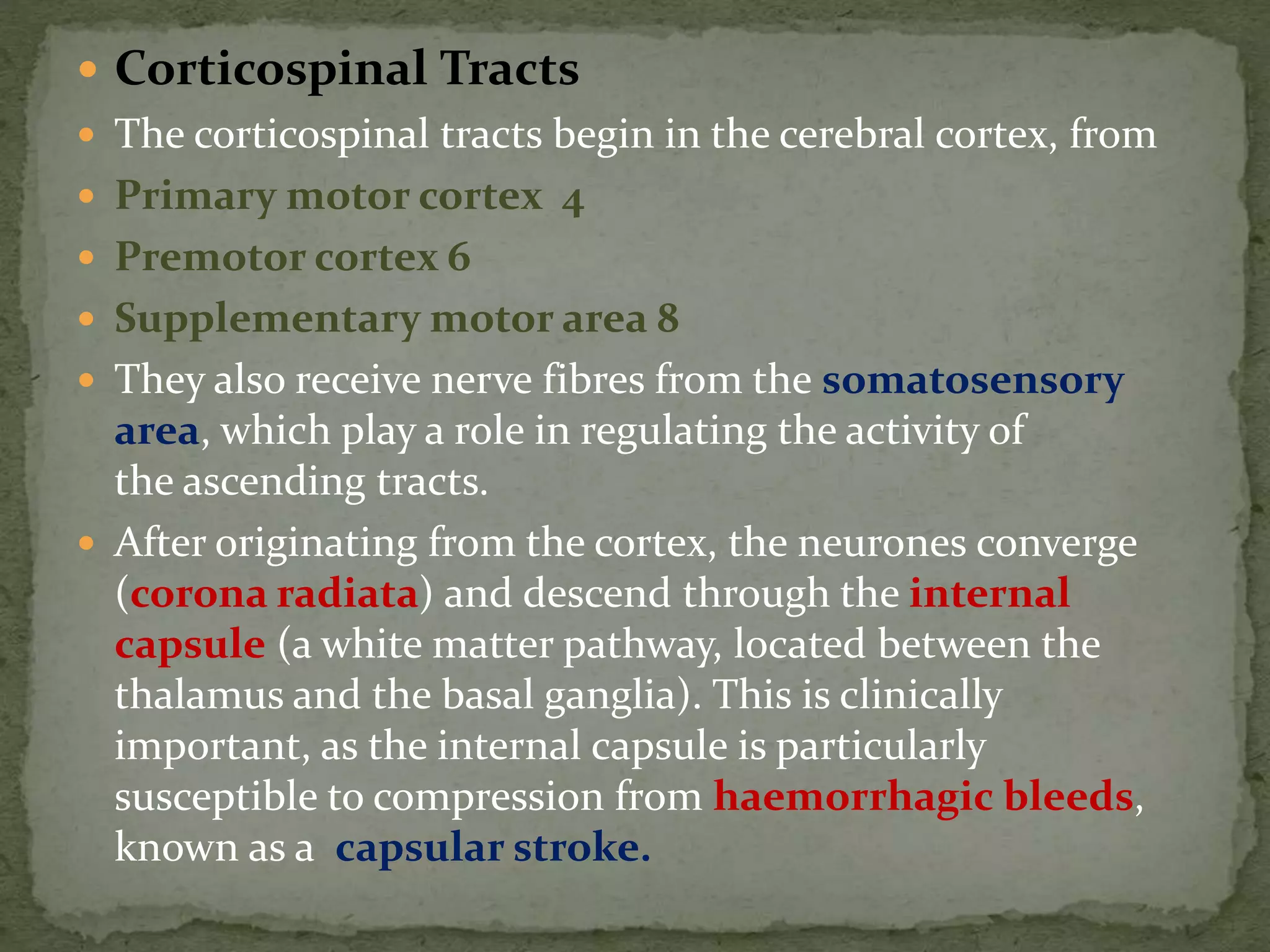

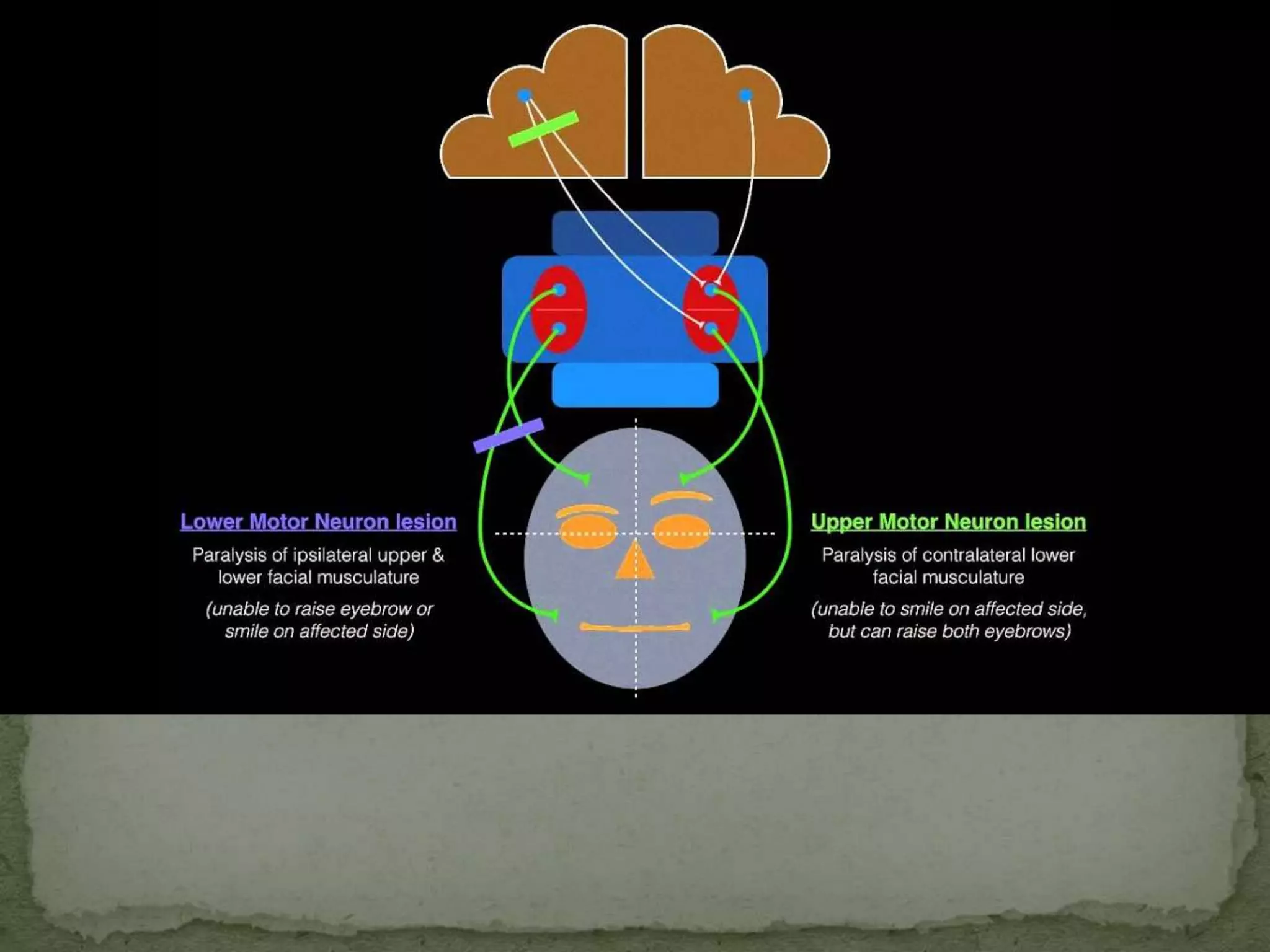

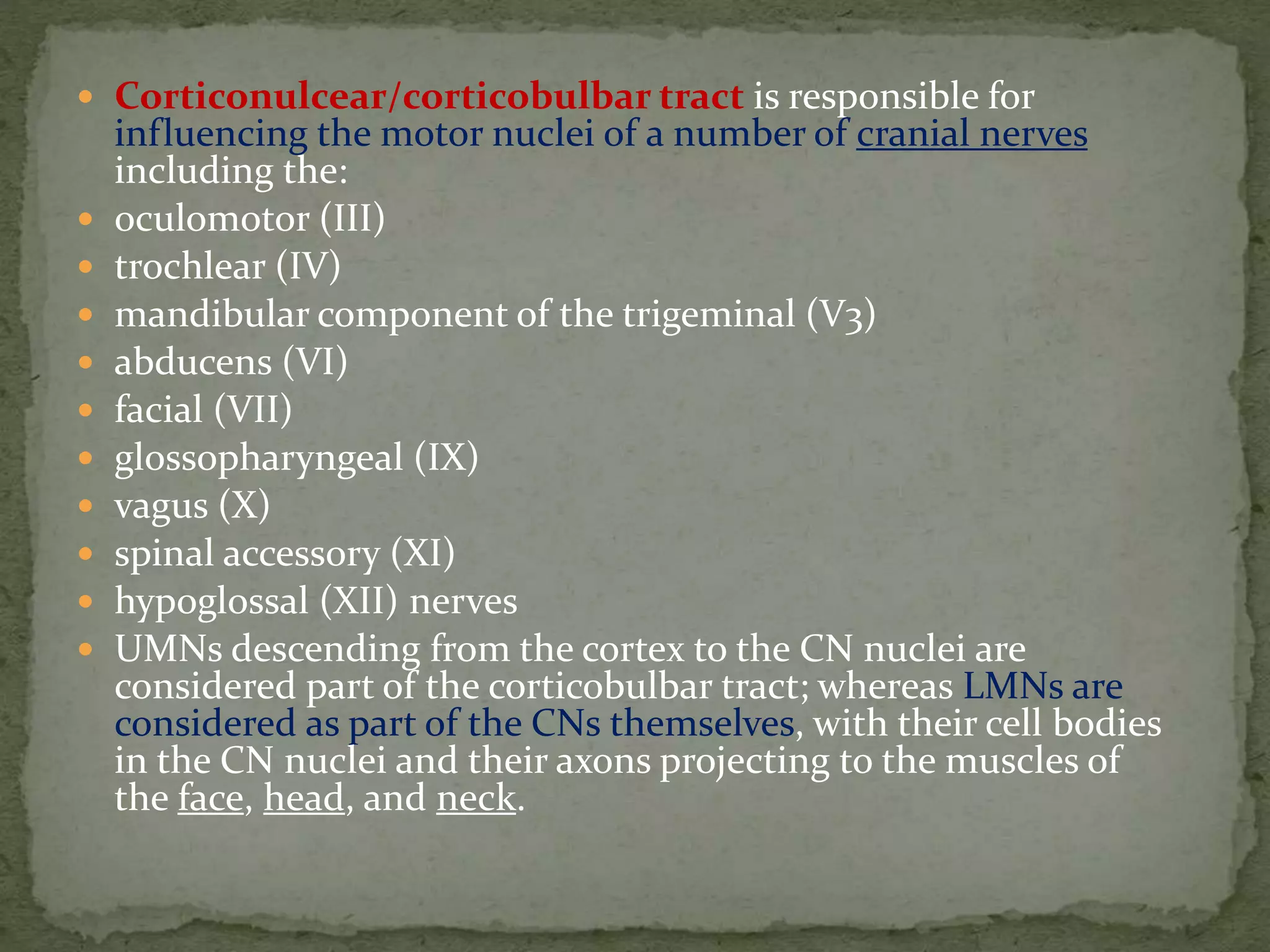

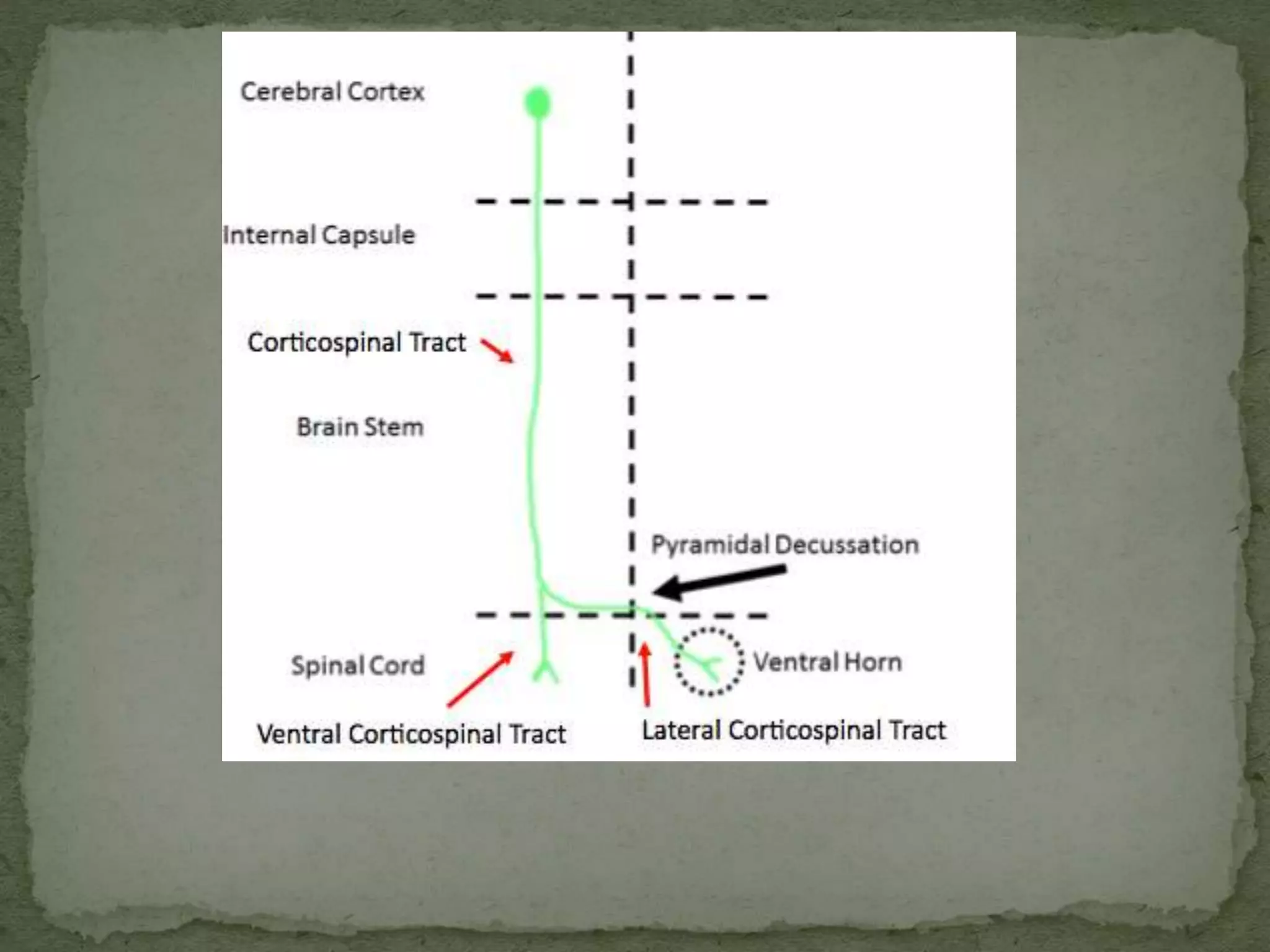

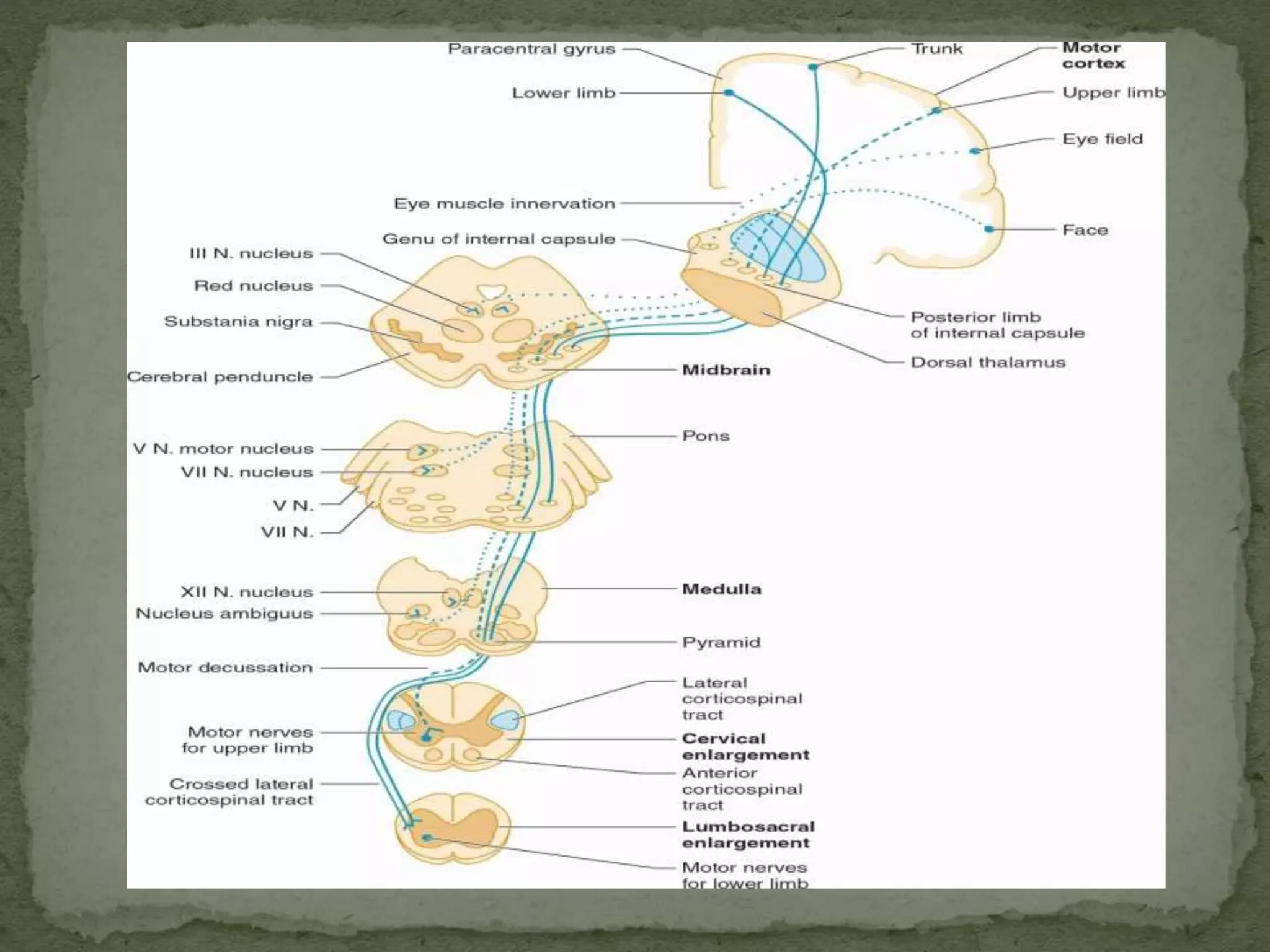

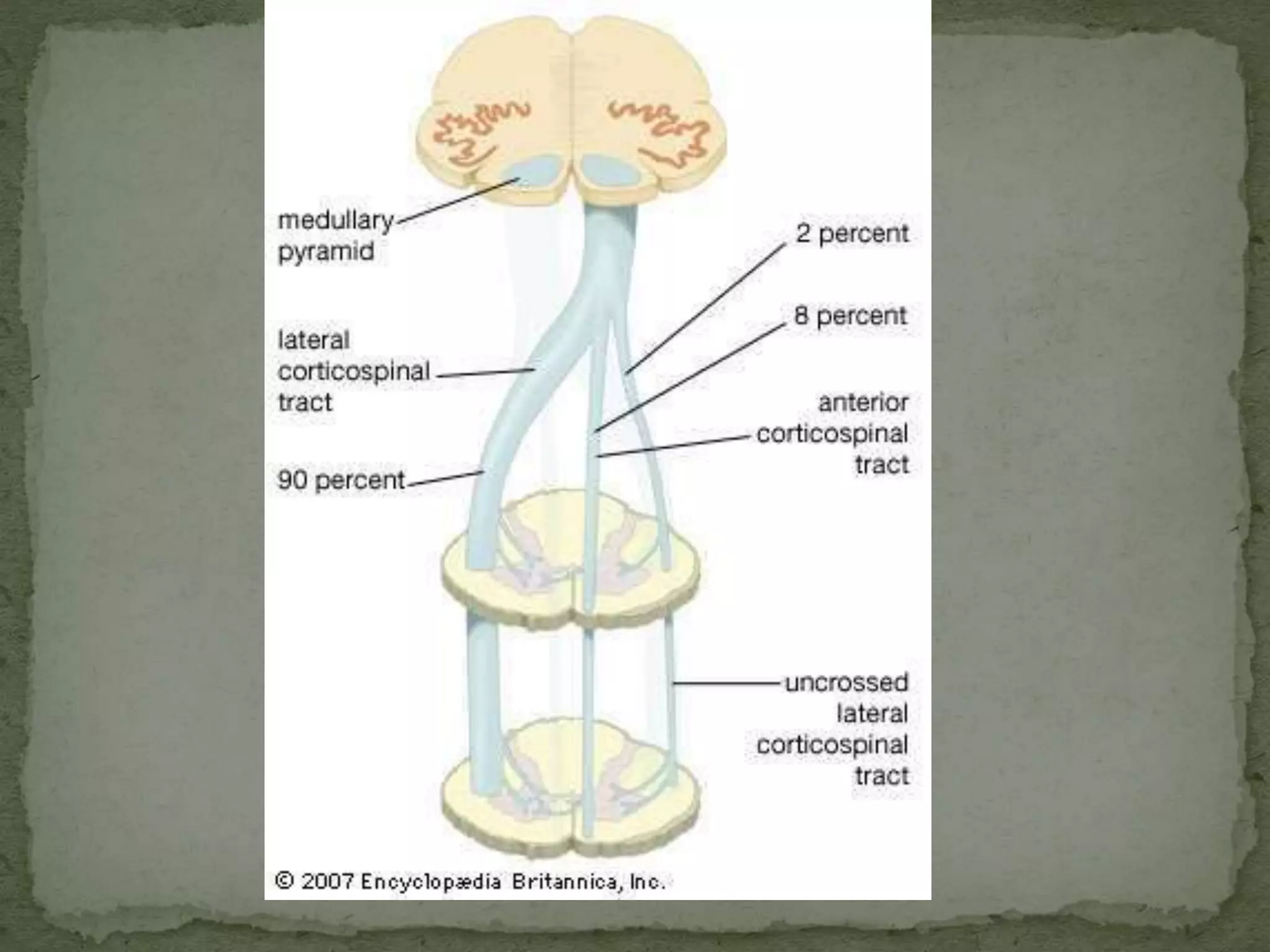

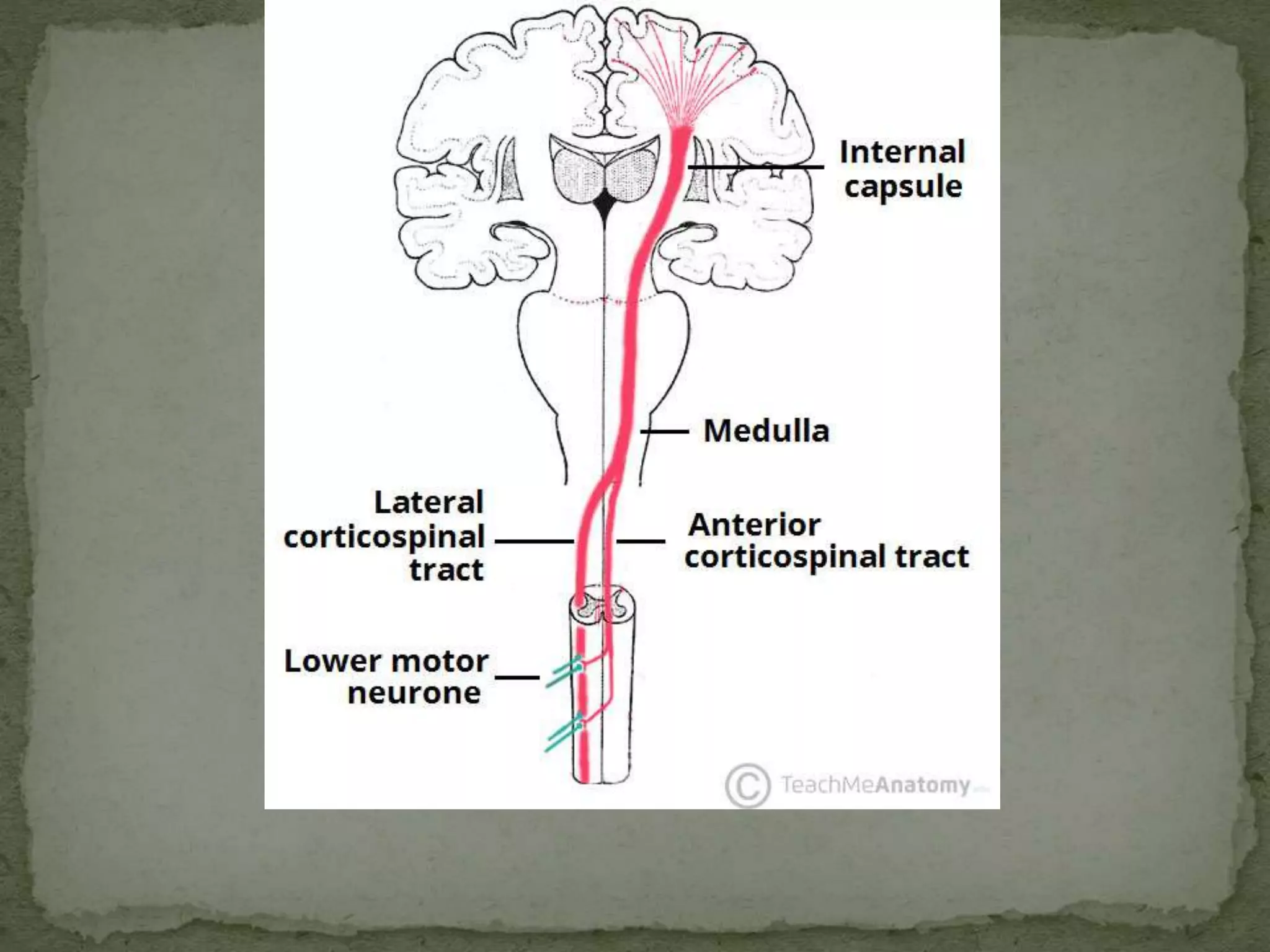

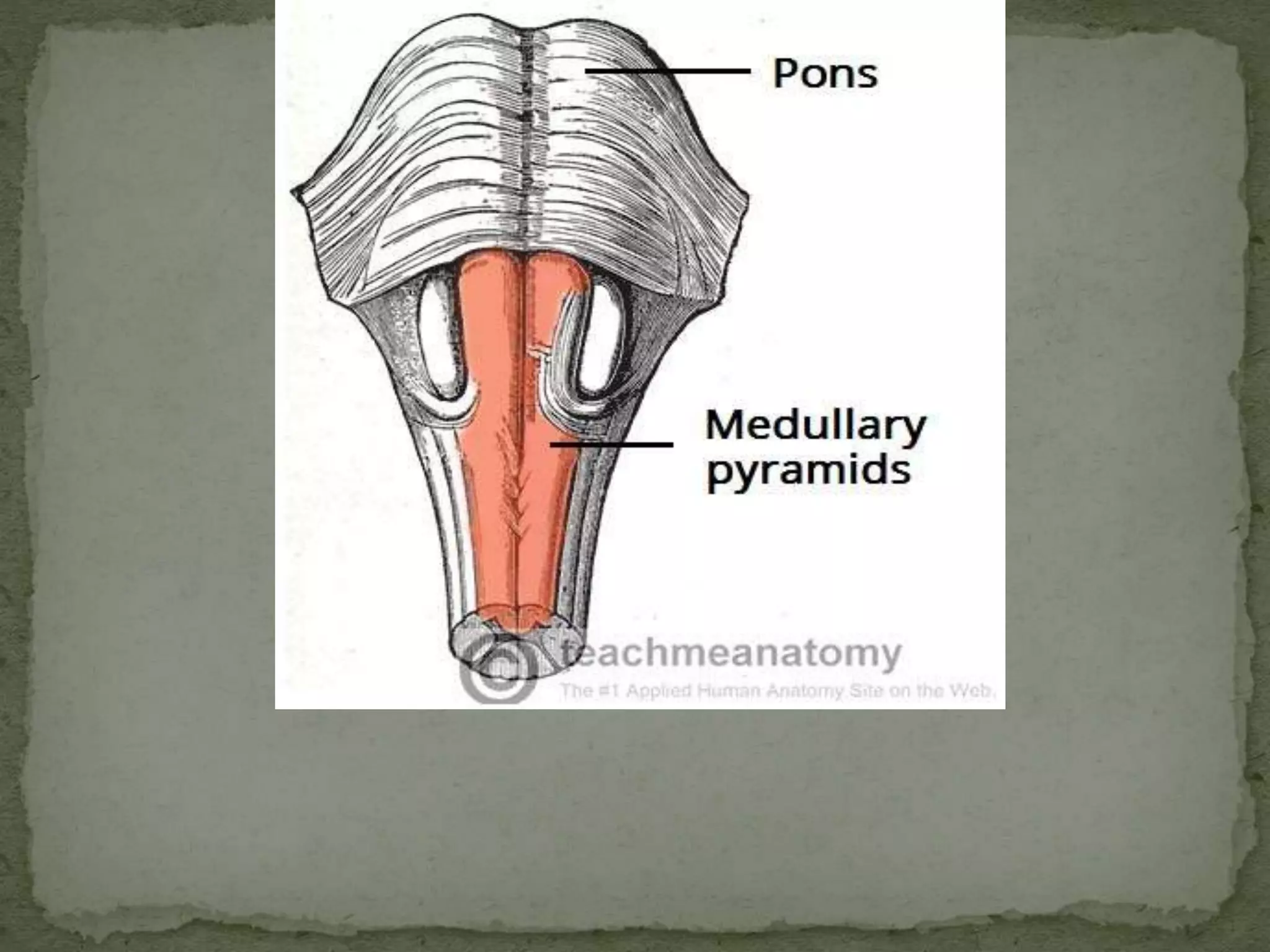

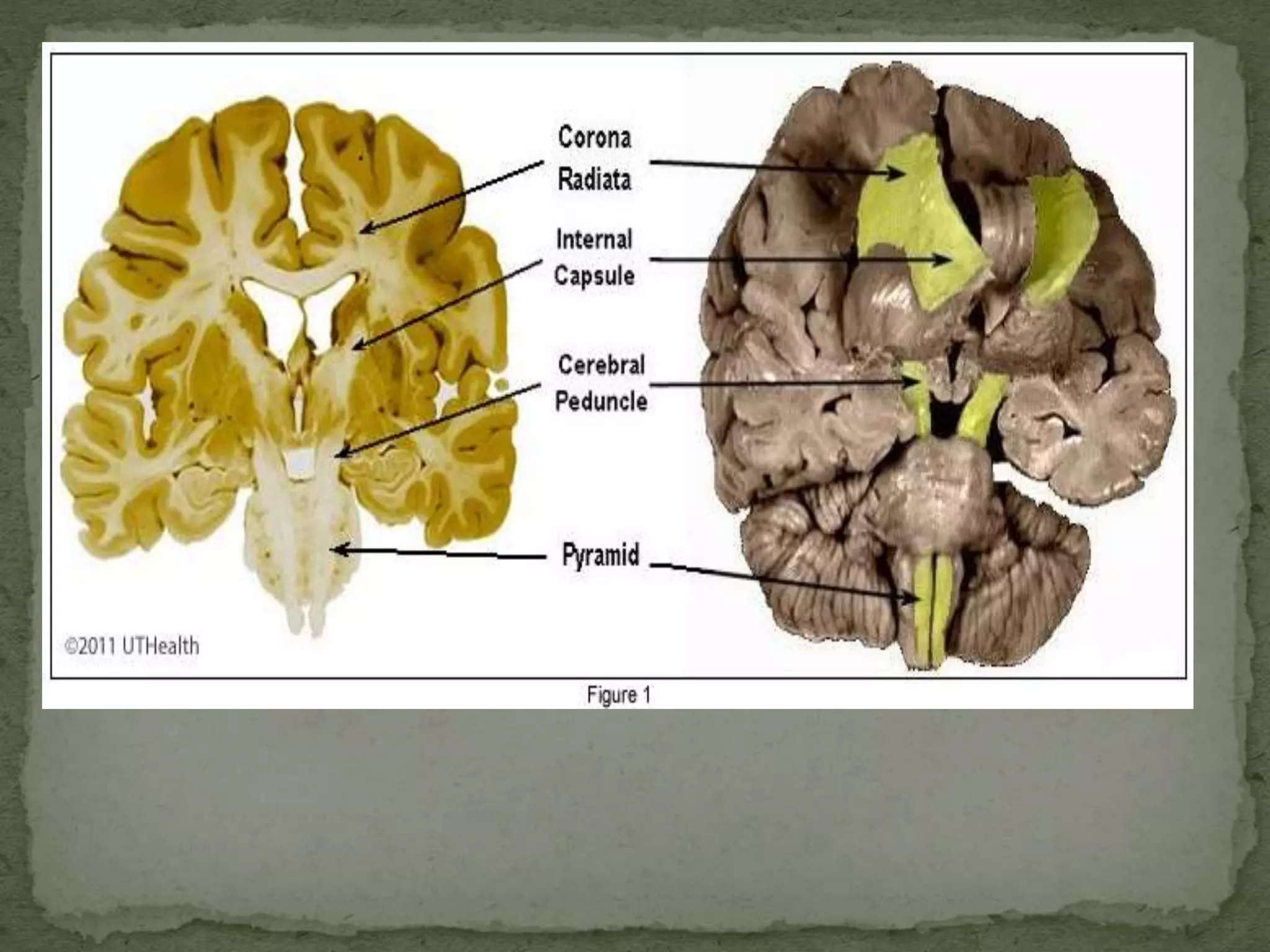

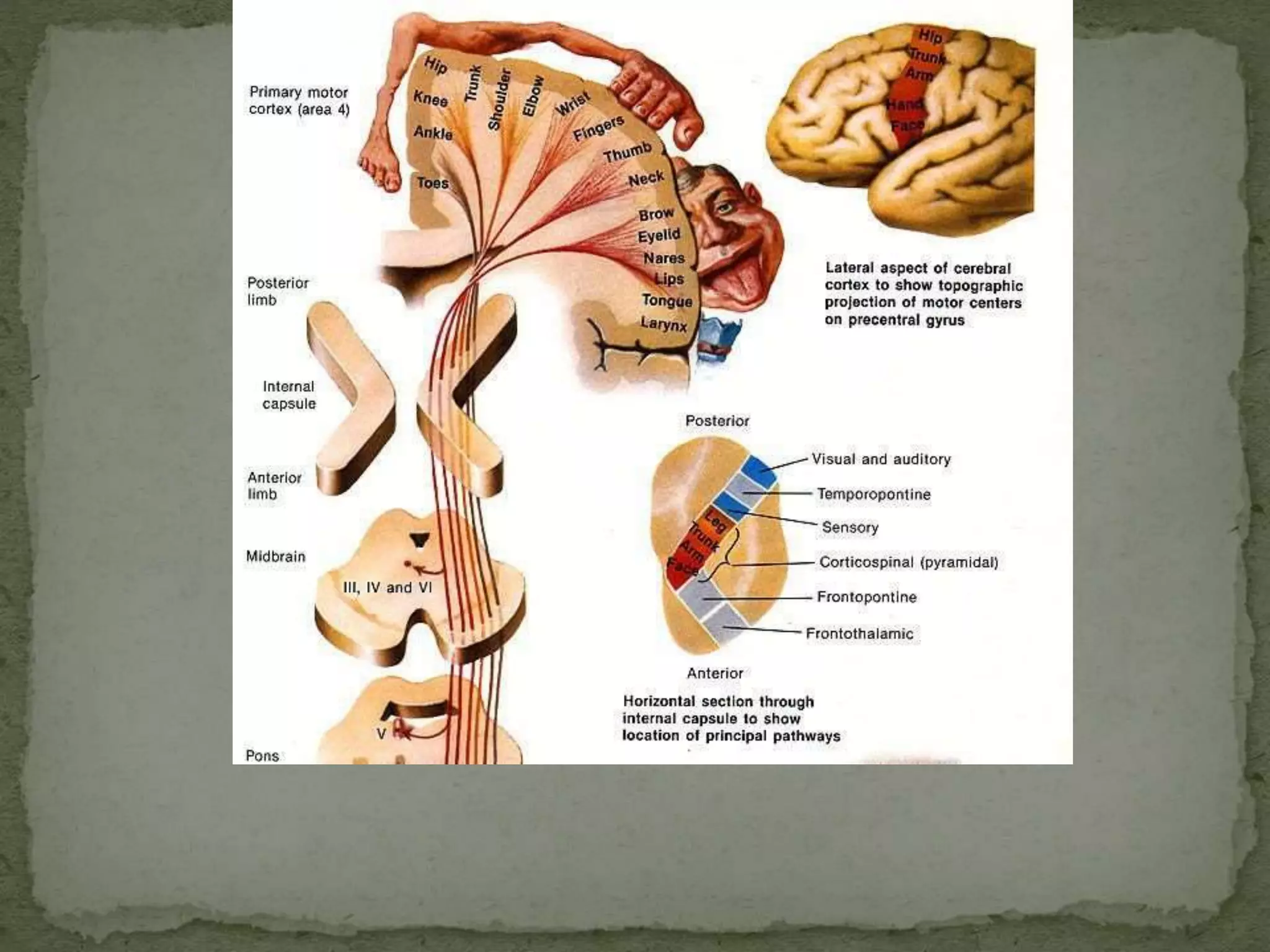

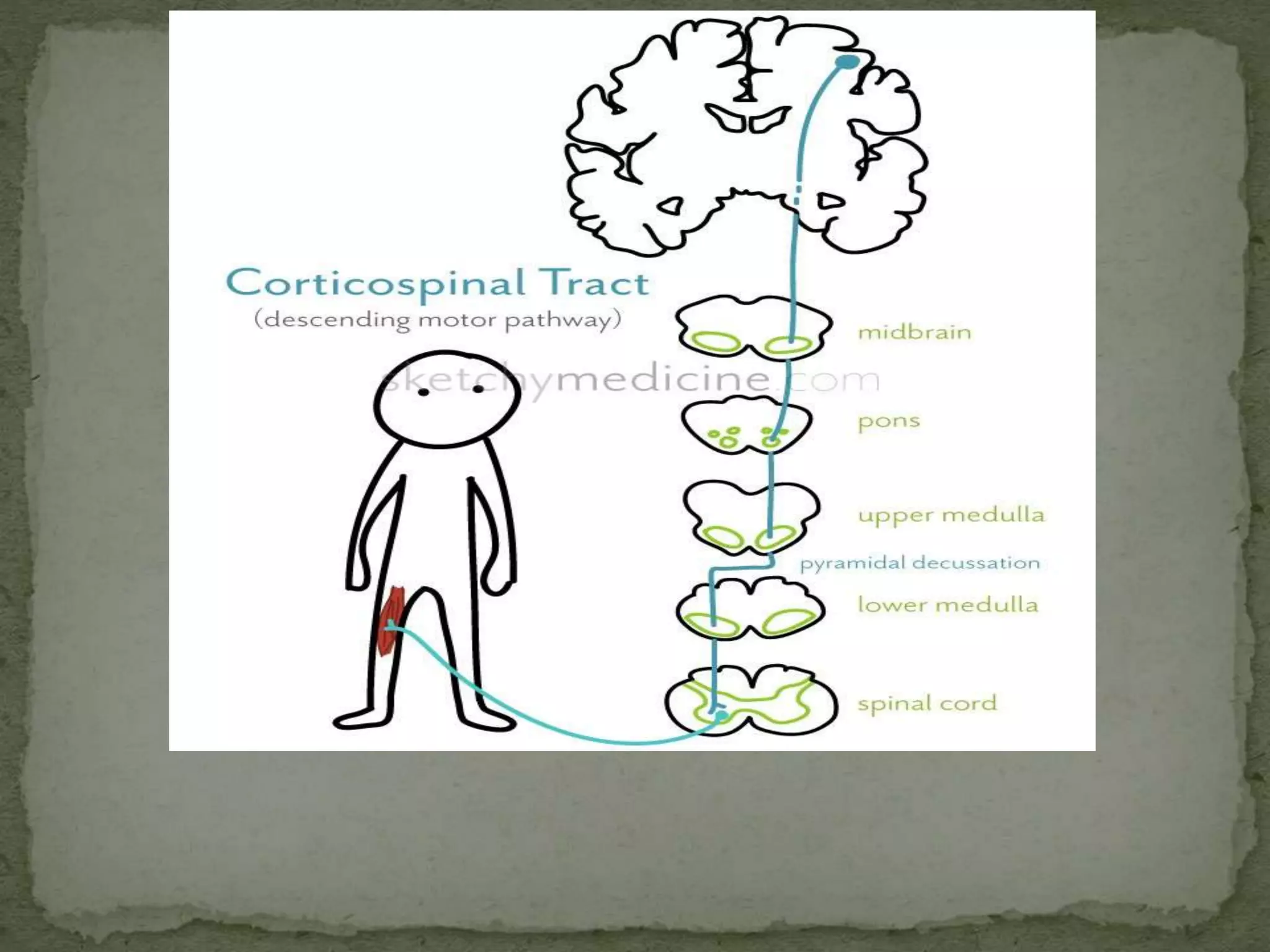

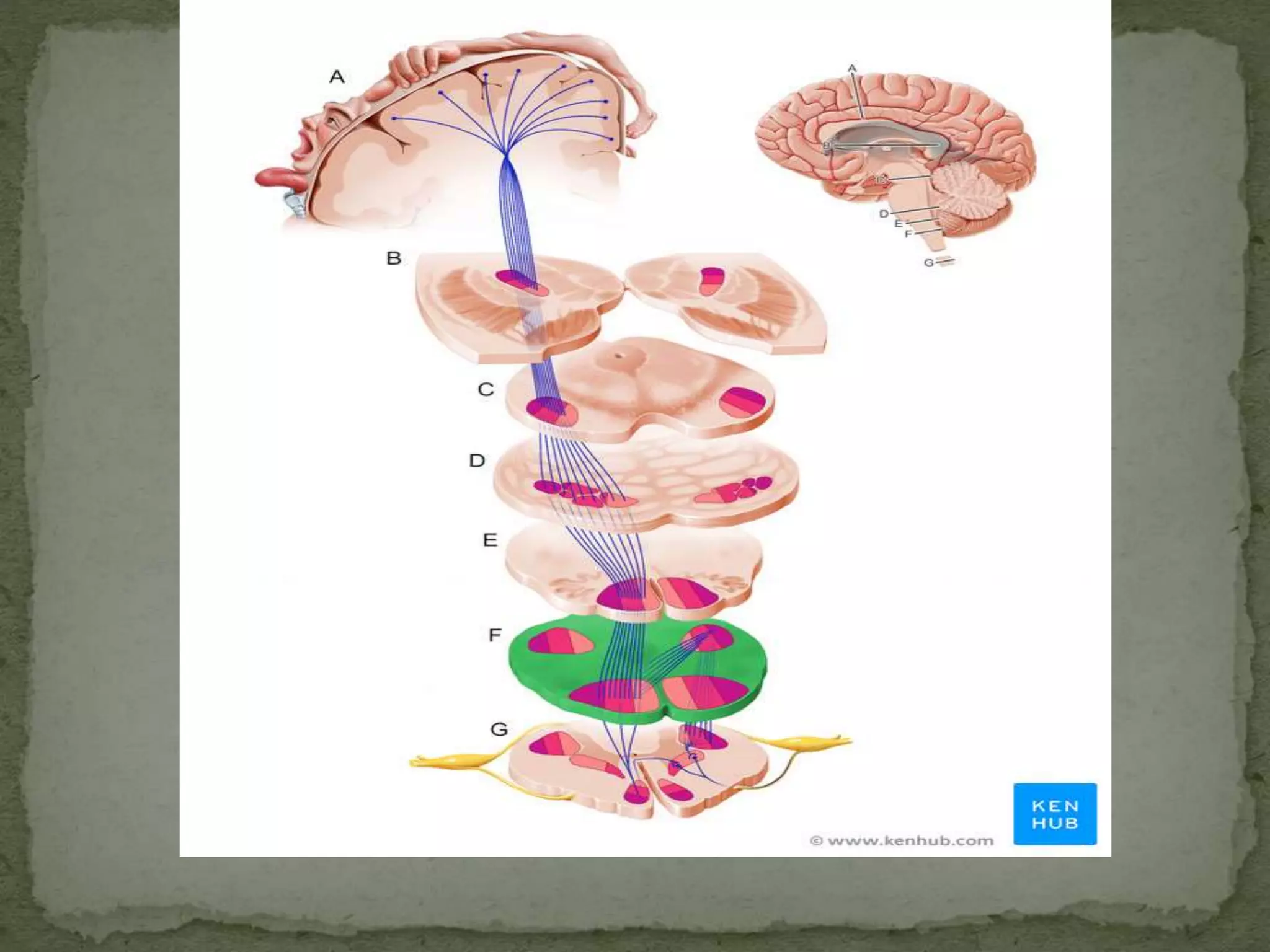

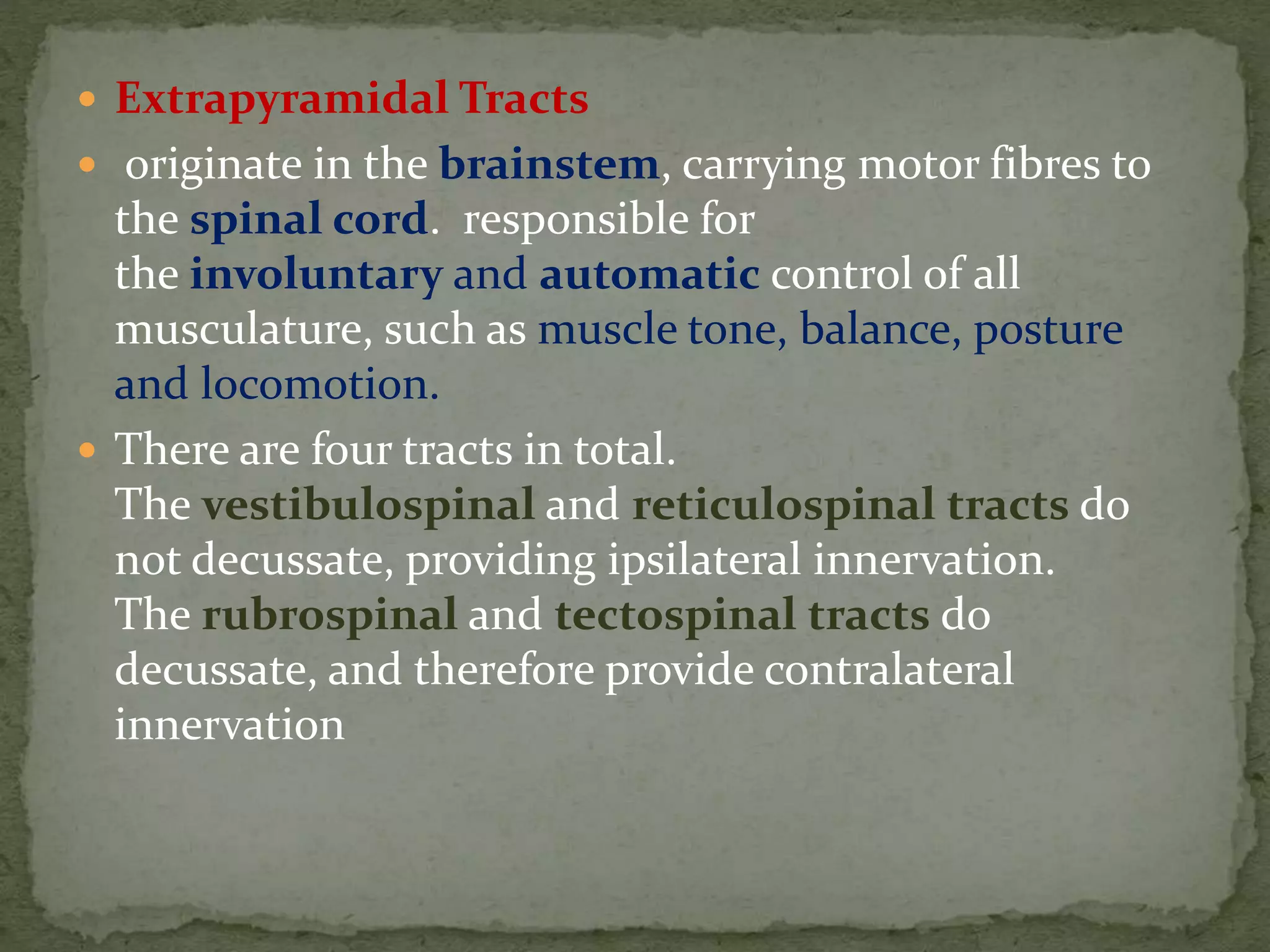

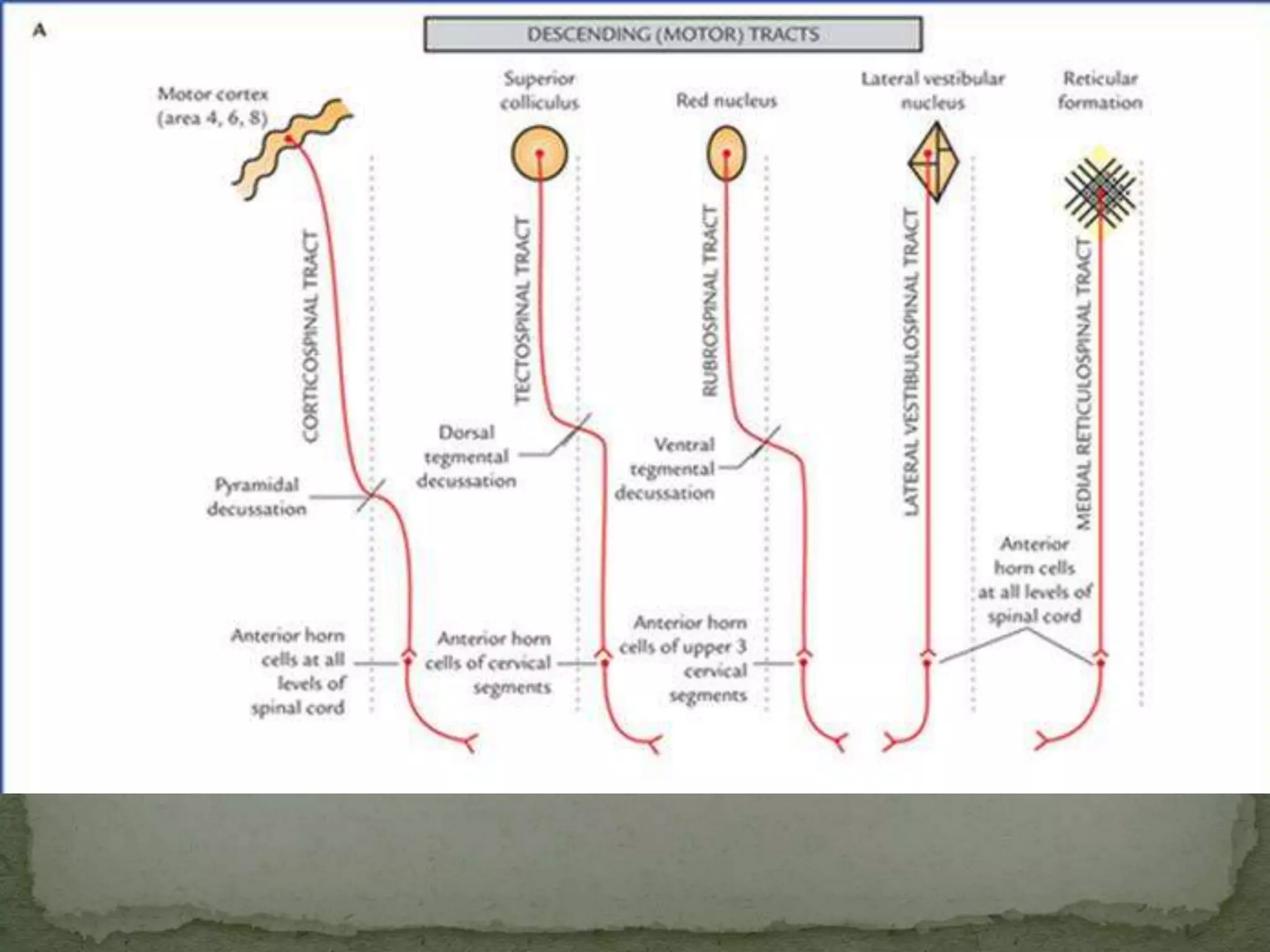

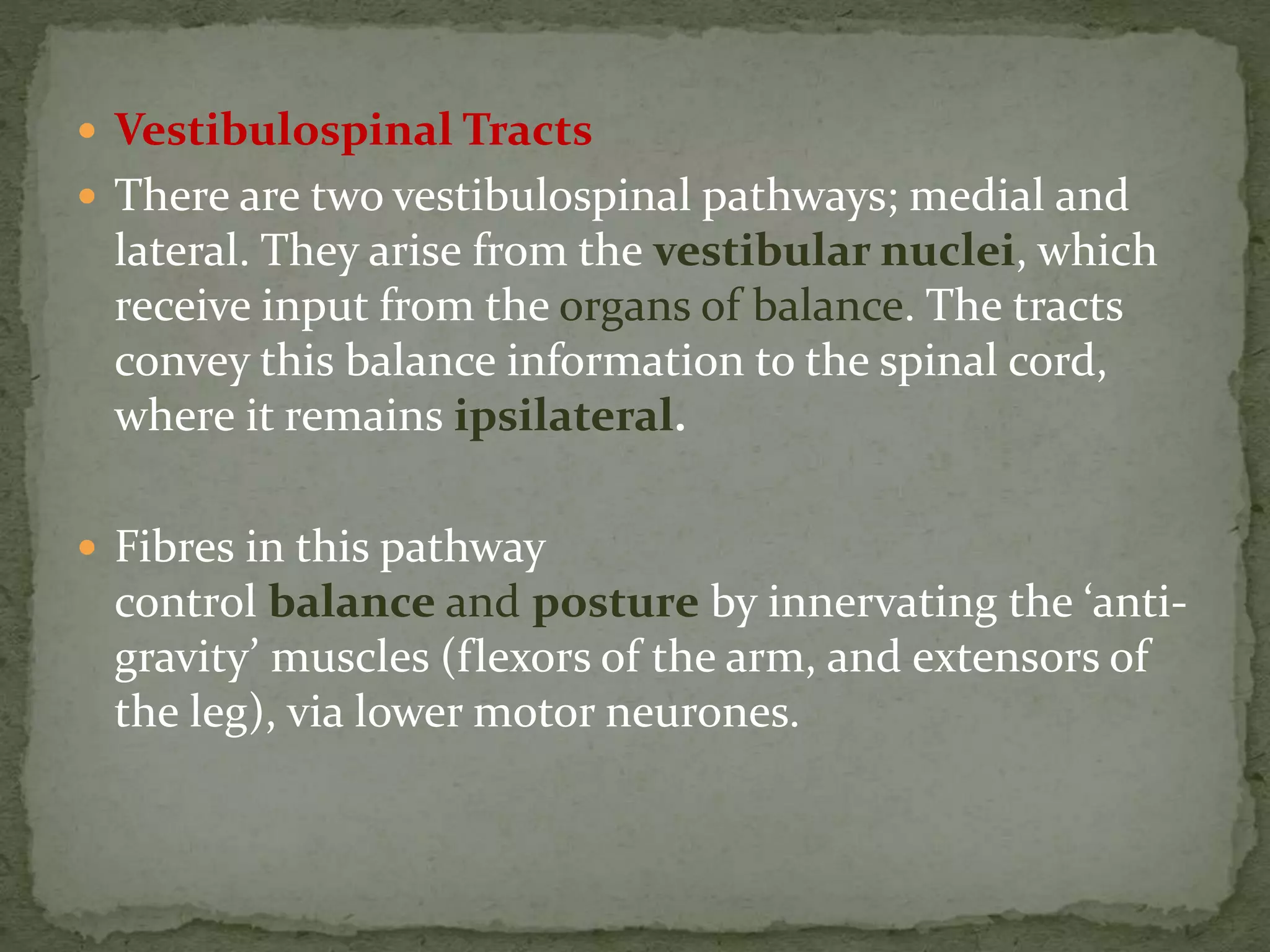

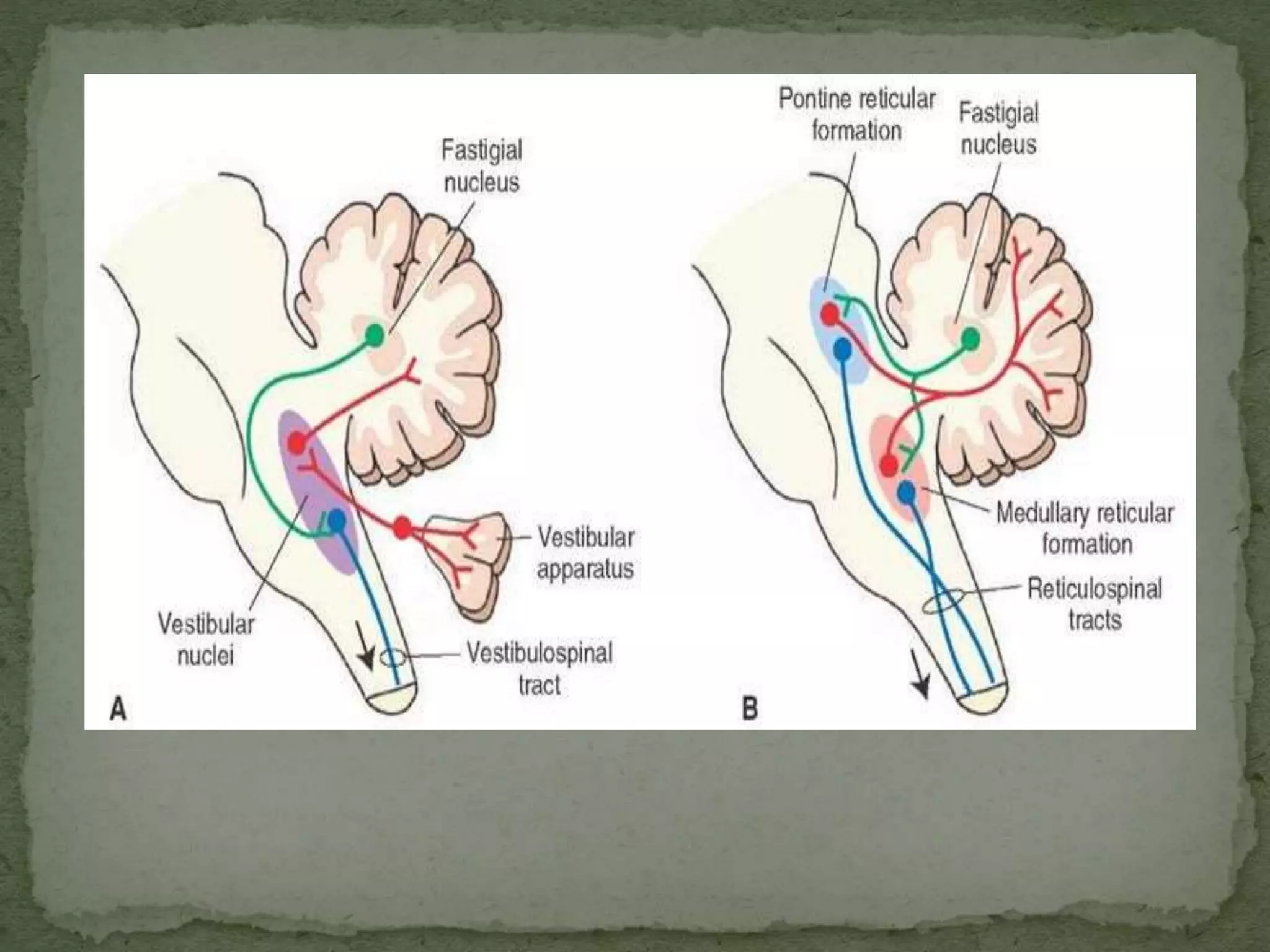

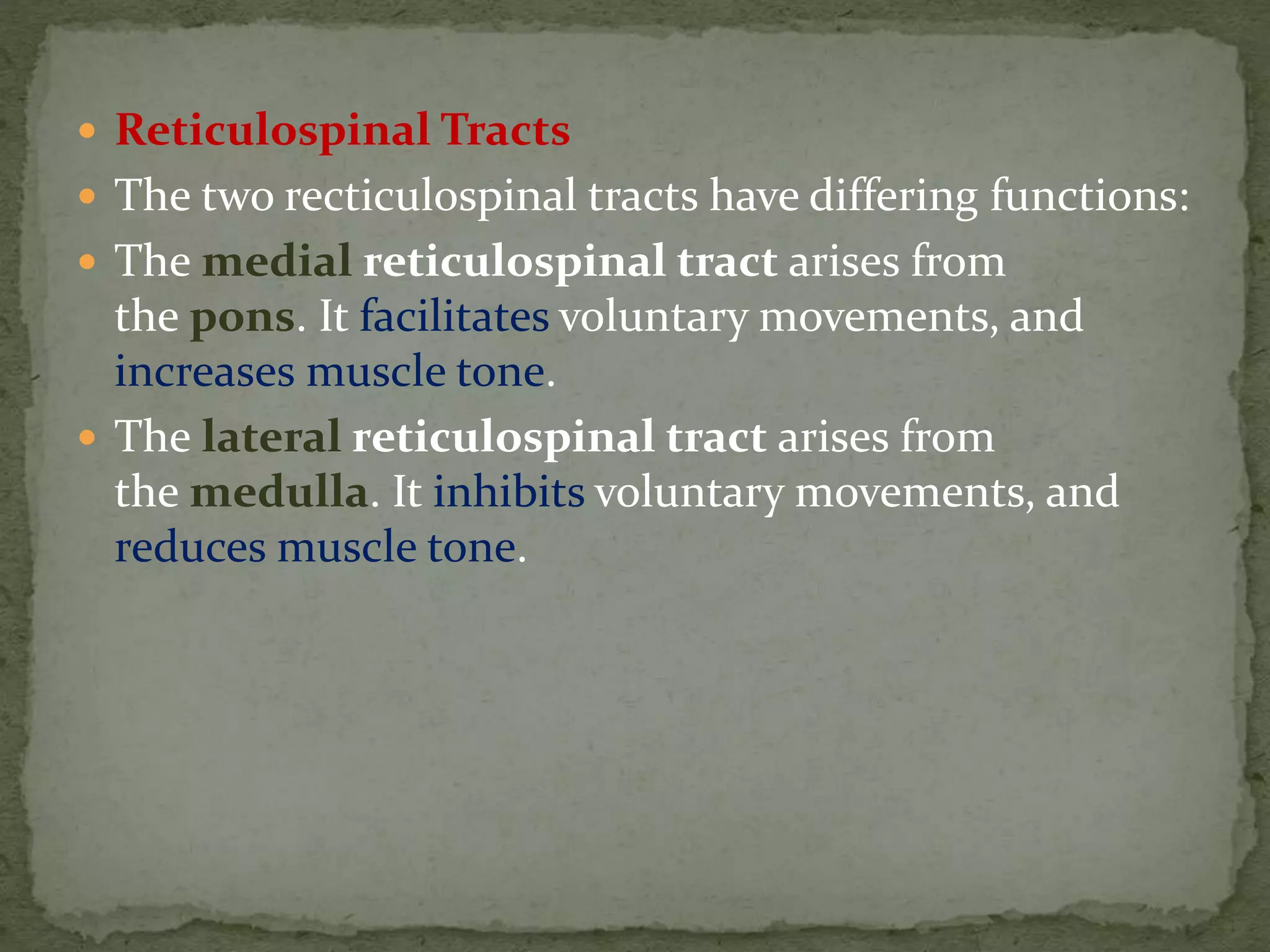

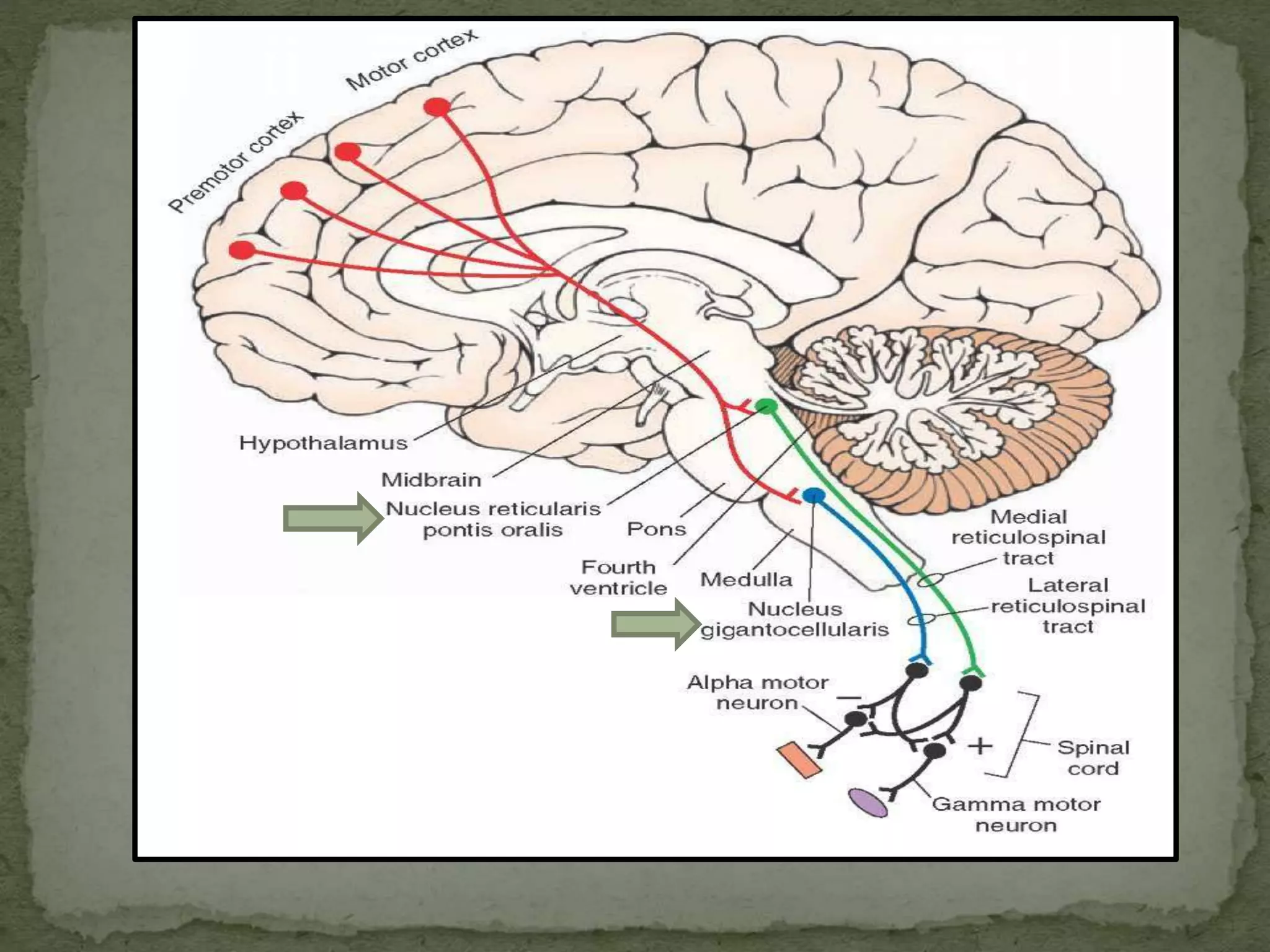

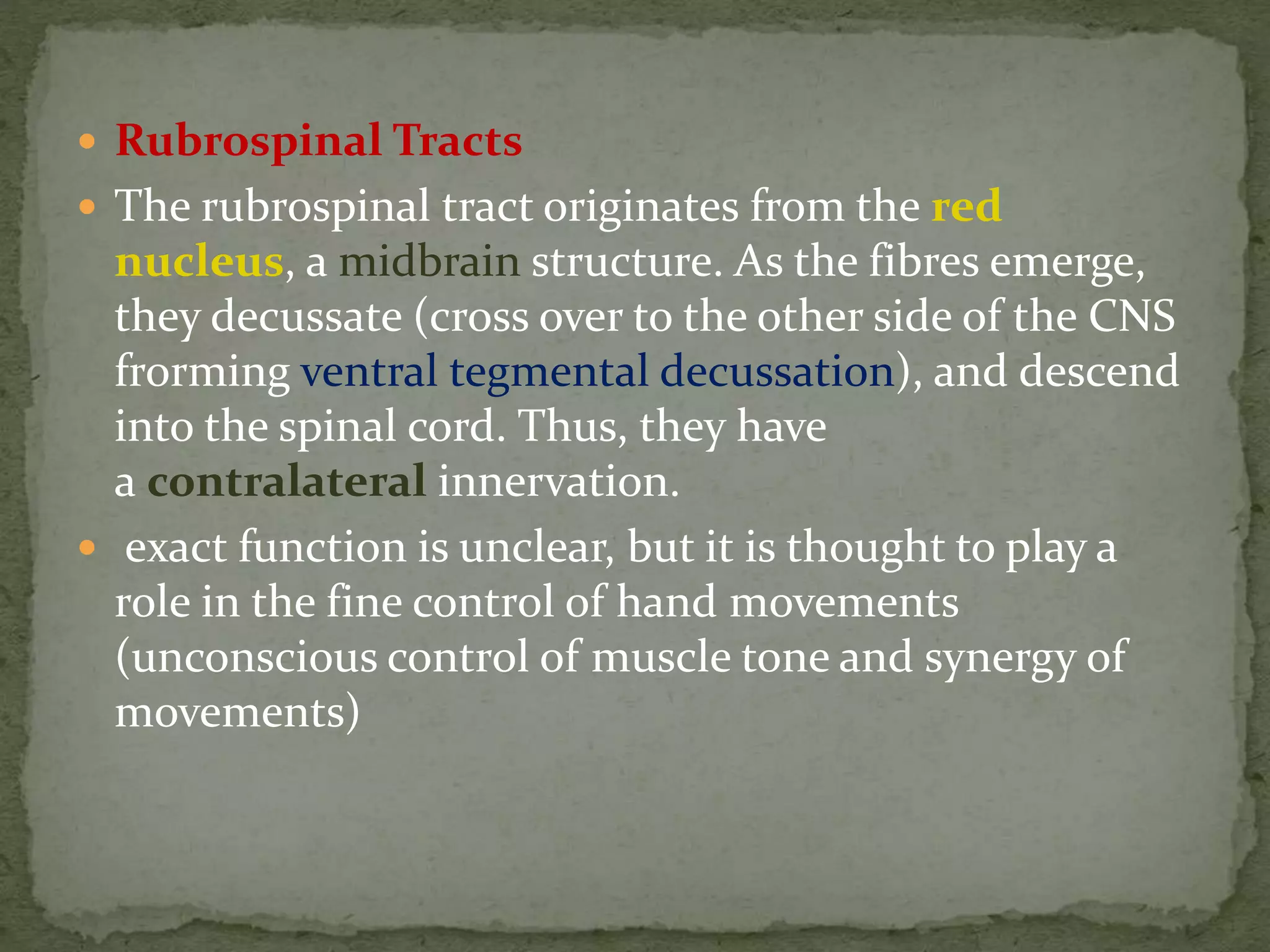

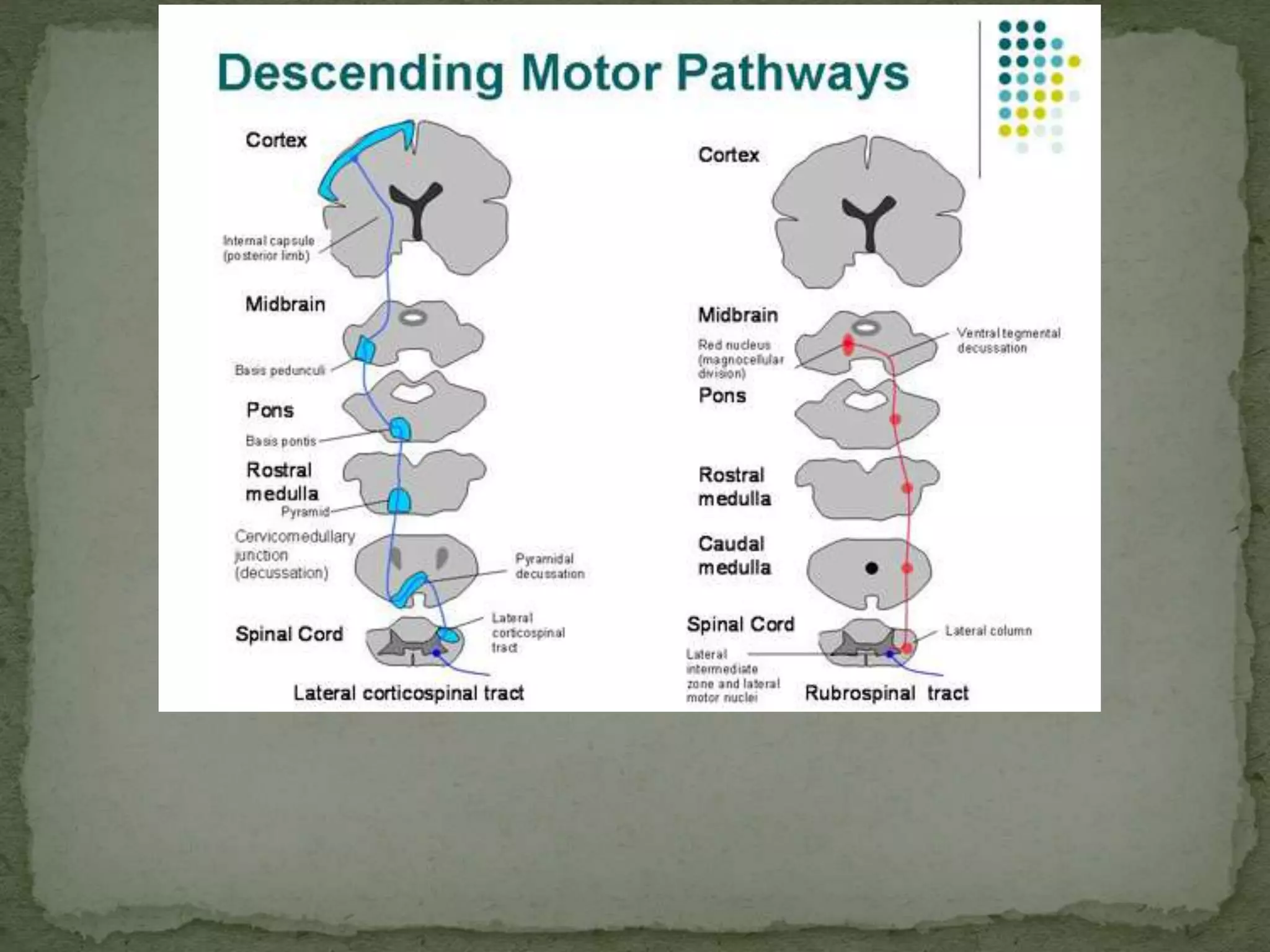

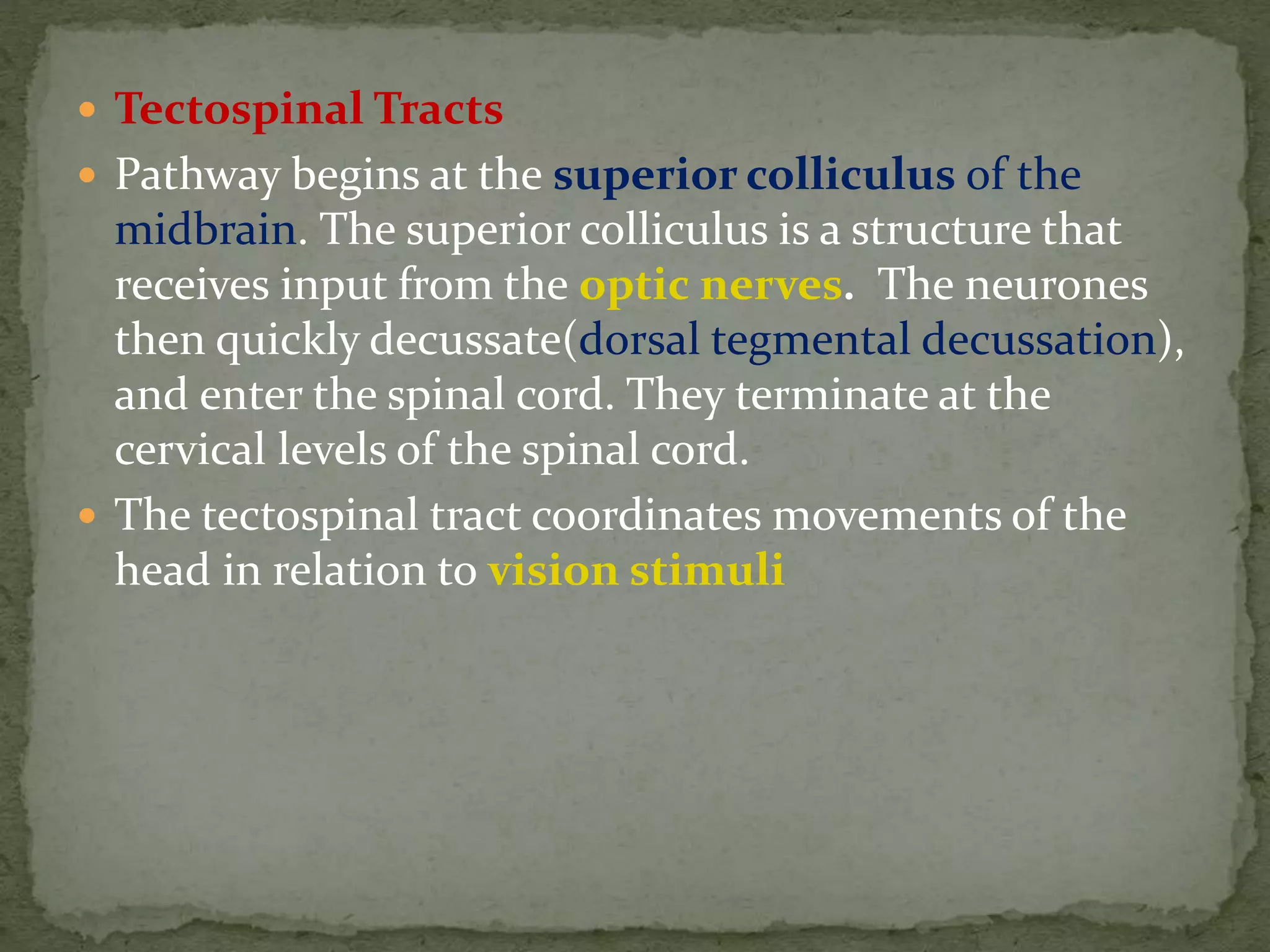

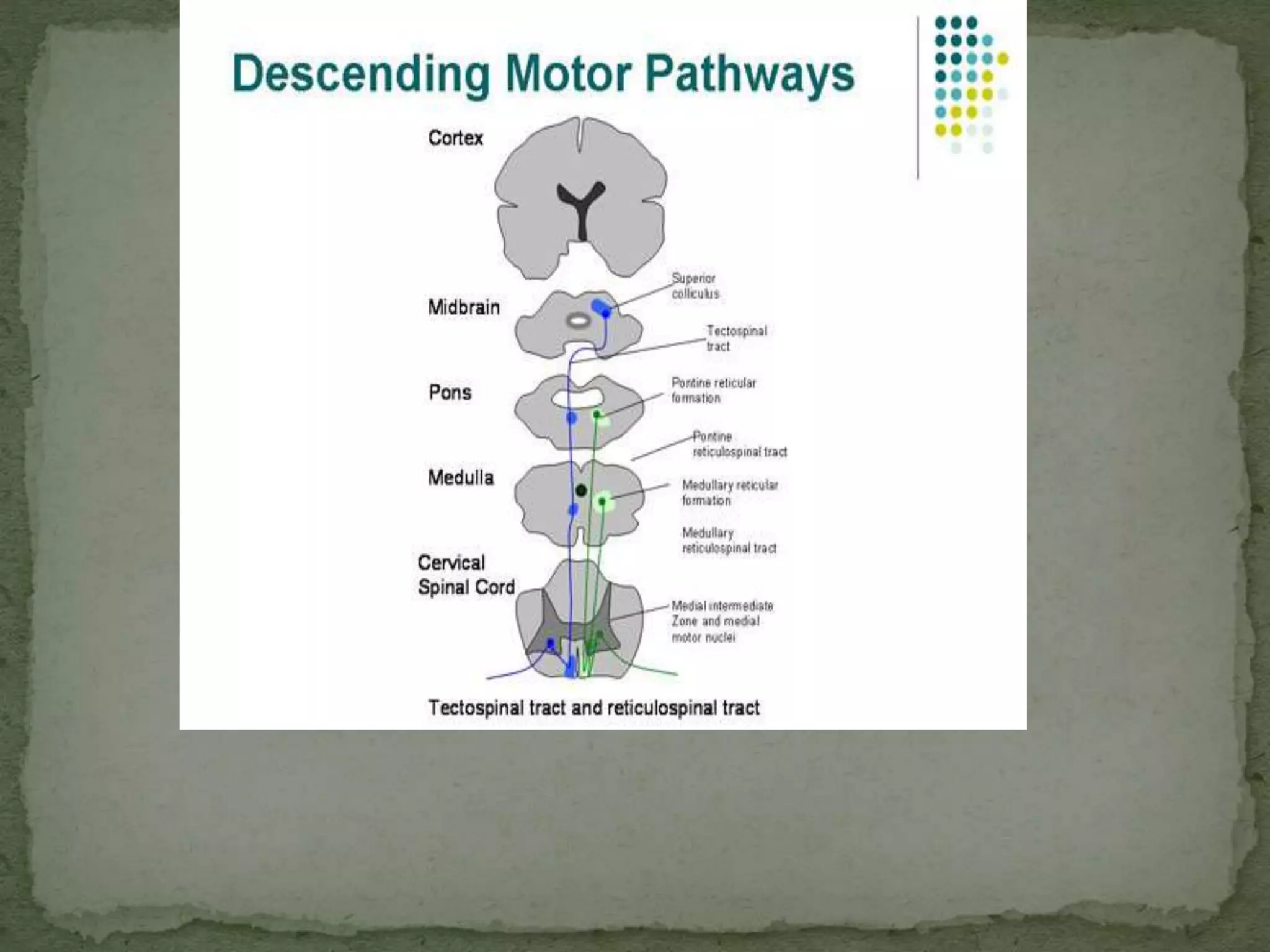

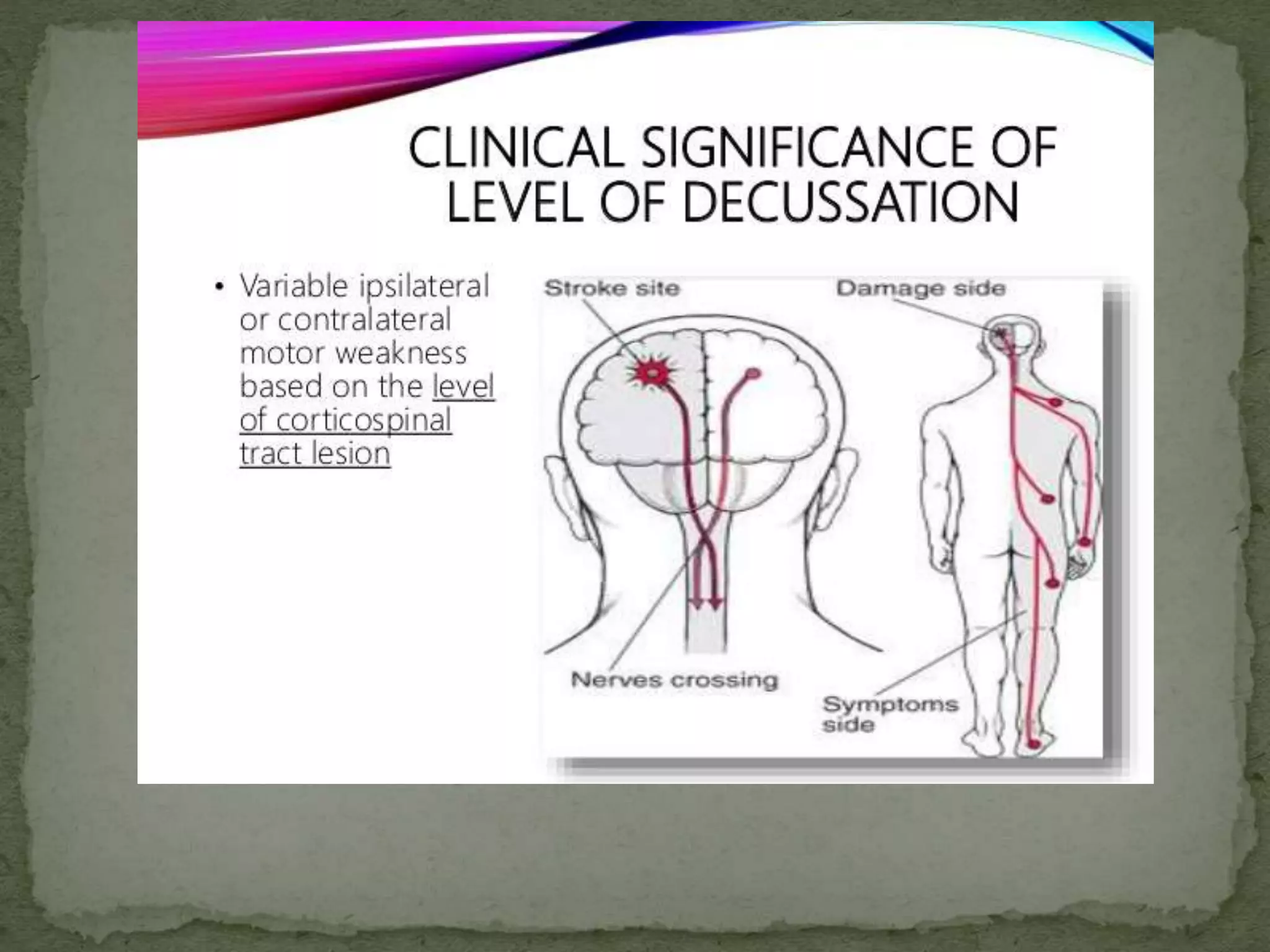

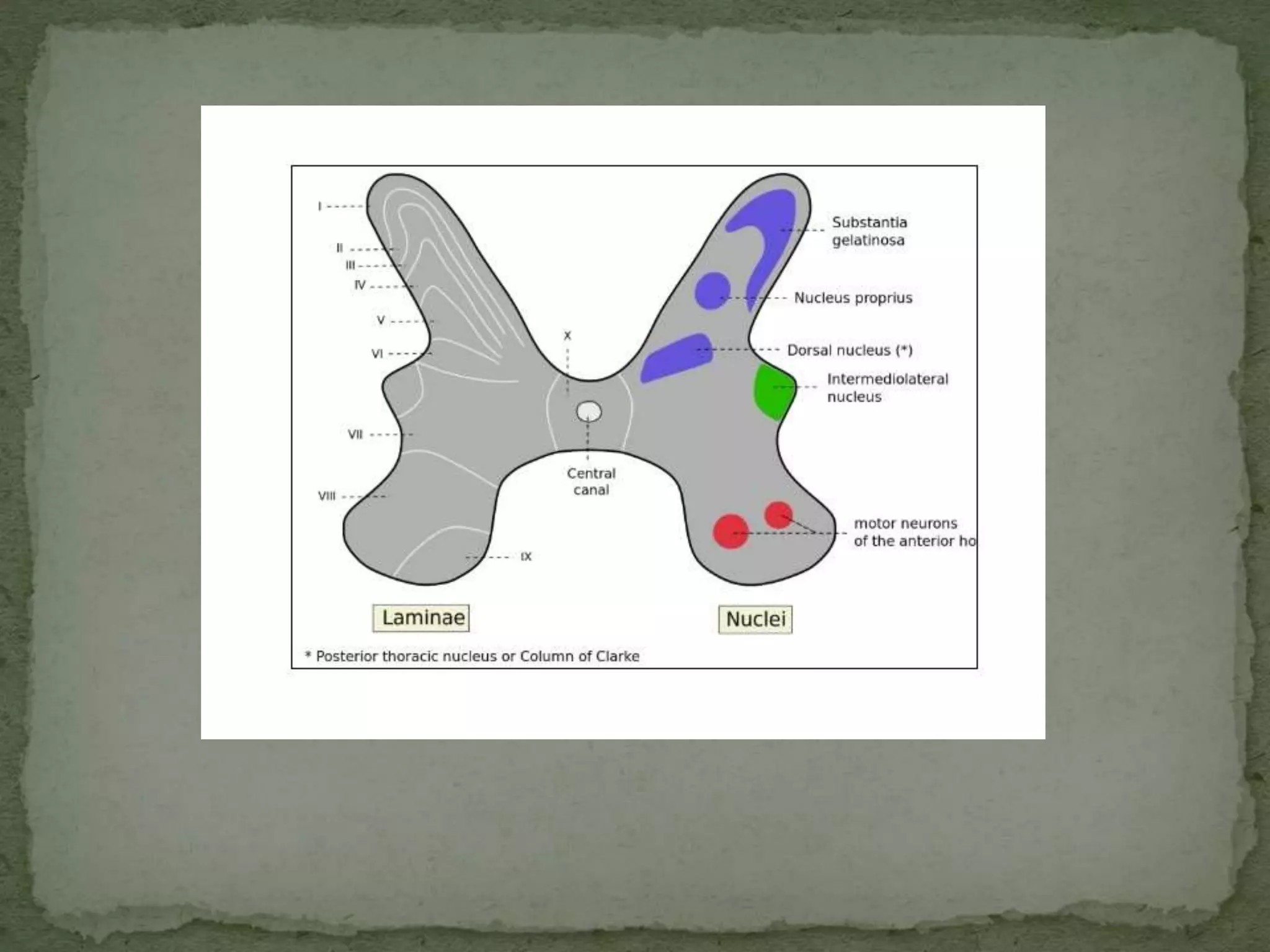

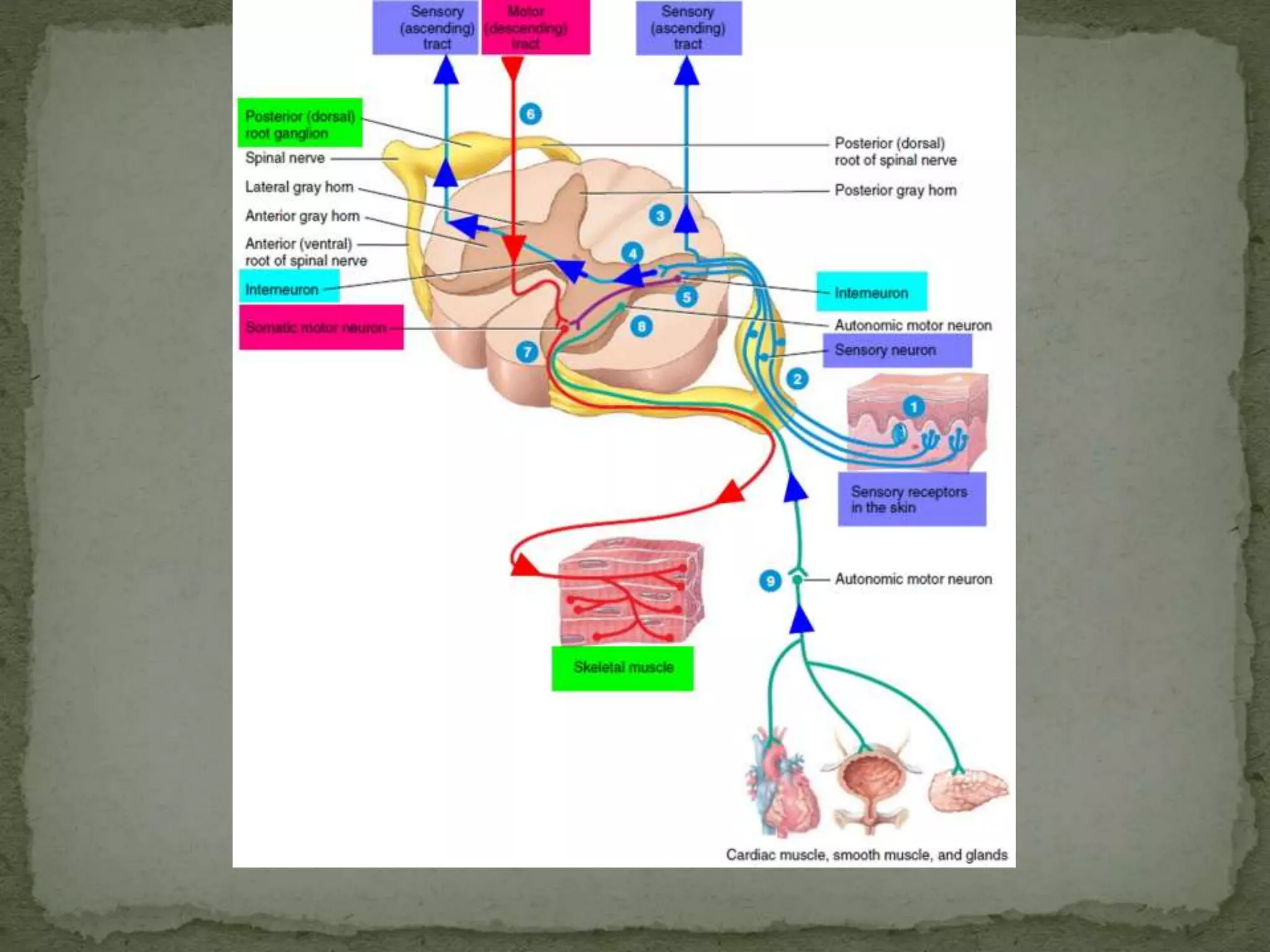

This document summarizes the major motor pathways in the brain and spinal cord. It describes the pyramidal tract, which originates in the motor cortex and is responsible for voluntary muscle control. The pyramidal tract includes the corticospinal and corticobulbar tracts. It also describes the extrapyramidal tracts that originate in the brainstem and are responsible for involuntary muscle control, including balance, posture and locomotion. Each tract is described in terms of its origin, pathway through the central nervous system, functions and clinical significance.