This document presents a study on a posteriori error estimation for the extended finite element method (XFEM). It discusses modeling discontinuities using XFEM for one- and two-dimensional problems. The study develops a recovery-based error estimator to measure the difference between the direct and post-processed approximations of the gradient from XFEM solutions. It aims to provide a smoothed gradient that is superior to the discontinuous gradient from the original finite element approximation. The document includes an introduction covering element approximation techniques, computational fracture mechanics, a posteriori error estimation, and an outline of the following sections on one-dimensional and two-dimensional model problems, XFEM formulations, and implementation results.

![7

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an introduction to discontinuous enrichment in the finite element

framework, and a solution to measure the accuracy of this tool for approximated solution in

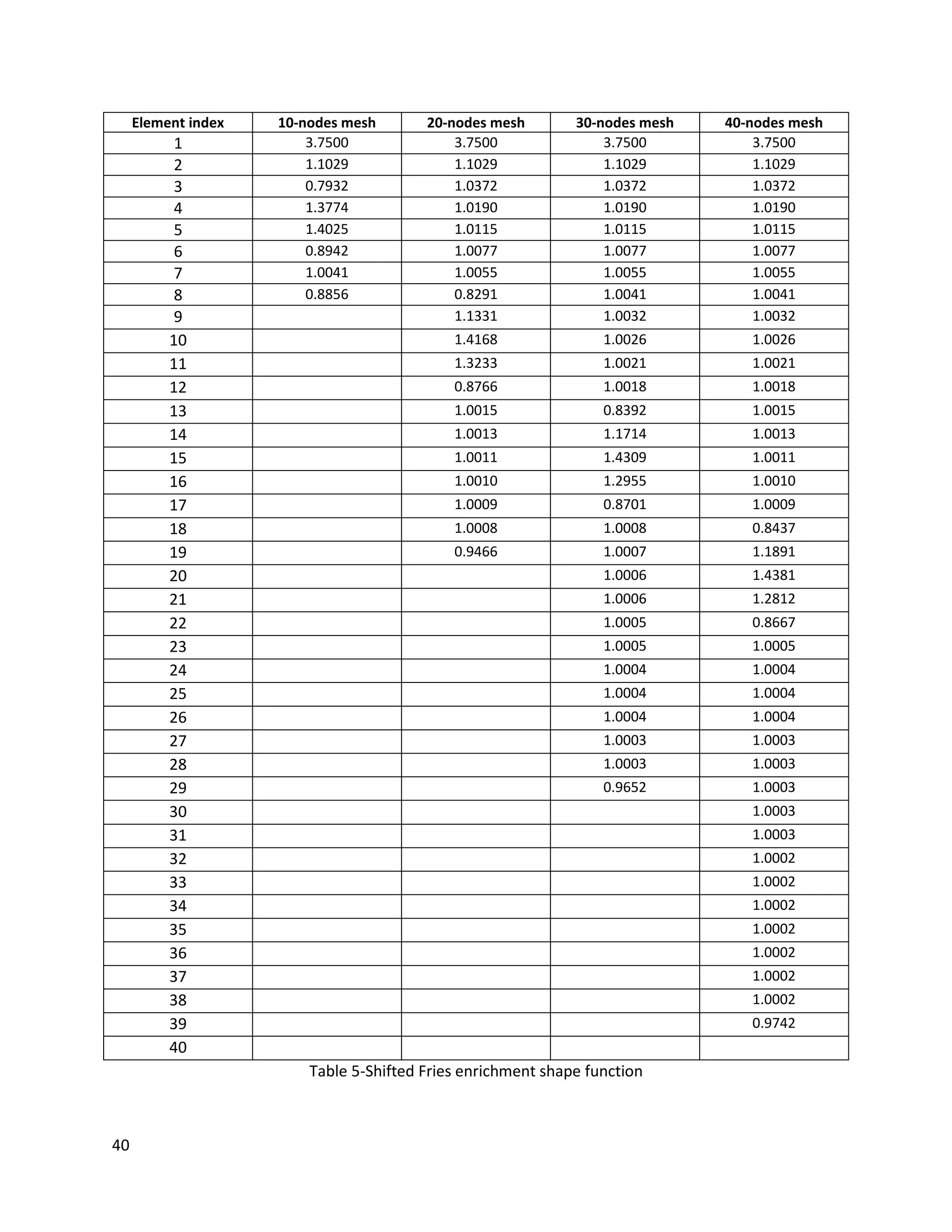

comparison to the exact solution without enhancing the exact equation. The introduction

consists of four sections. Section 1.1 reviews some advancements made in element and

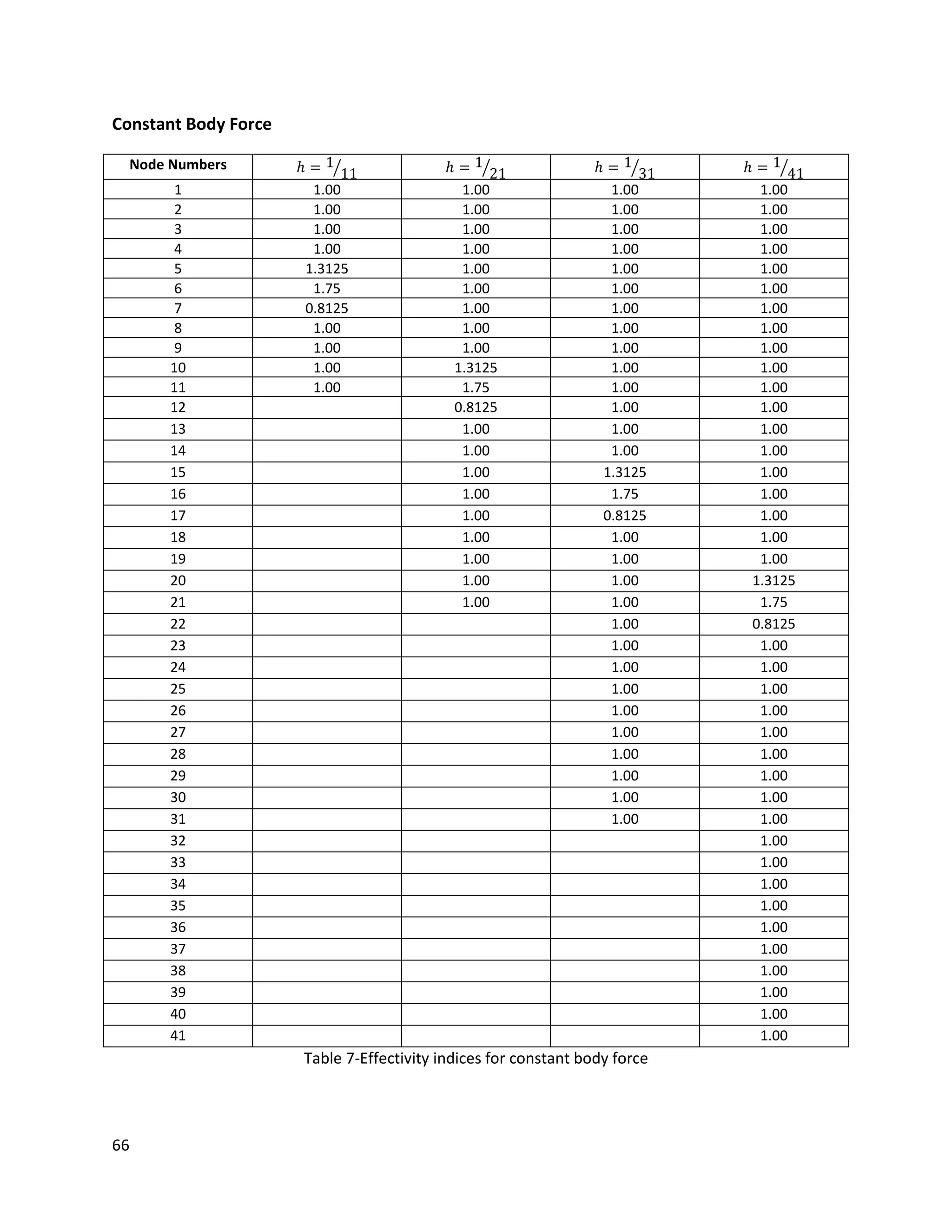

approximation technology in the recent progress of finite element method (FEM). The method

developed in the field of fracture mechanics, and pertinent issues are reviewed in section 1.2.

The following section discusses a posteriori error estimation principles, and suggests its

advantages over the adaptivity and discontinuous enrichment methods. Finally, section 1.4

provides an outline of the remainder of the work.

1.1. Element and Approximation Technology

Finite element methods (FEM) have been widely used since their appearance six decades ago.

This popularity is due to their flexibility to deal with numerous problems and due to their

robustness. The FEM is used by scientists and engineers to investigate the dynamic failure of

structures, turbulent flow around an airfoil, heat transfer, and electromagnetism just to name a

few applications. While the finite element method is robust, it is not particularly well suited to

models involving discontinuities or singularities.

Due to the fact that standard finite element methods are based on piecewise differentiable

polynomial approximation (Galerkin method), they rely on an element topology for

construction of an approximating space. The construction of a discontinuous space with finite

elements necessitates the alignment of the element boundary with the geometry of the

discontinuity. Typically, finite element methods require significant mesh refinement or meshes

which conform with these features to get accurate results. This is not only computationally

costly and cumbersome but also results in loss of accuracy as the data is mapped from old mesh

to the new mesh. To compensate this deficiency of standard finite element methods, extended

finite elements have been developed.

The partition of unity approach (Melenk and Babuska 1996 [17]) offered a systematic

methodology to incorporate arbitrary functions into the finite element approximation space.

Due to this it is then possible to incorporate any kind of function to locally approximate the

field. These functions may include any analytical solution of the problem or any a priori

knowledge of the solution from the experimental test. From there, X-FEM is able to reproduce

the problematic features, i.e., discontinuities and the singularities, without changing mesh sizes

and dramatically improved results are obtained. Since the introduction of extended finite

element method by (Moes, Dolbow, and Belytschko 1999 [8]) it has been widely applied to

numerous solid mechanics problem such as 2-, and 3-dimensional crack growth problems](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-7-2048.jpg)

![8

presented by Sukumar (2003) [23]. The XFEM also attains great simplicity of simulation for

interface problems like fluid-solid interaction to prevent computations that were formerly

tedious.

The enriched basis is formed by the combination of the nodal shape functions associated with

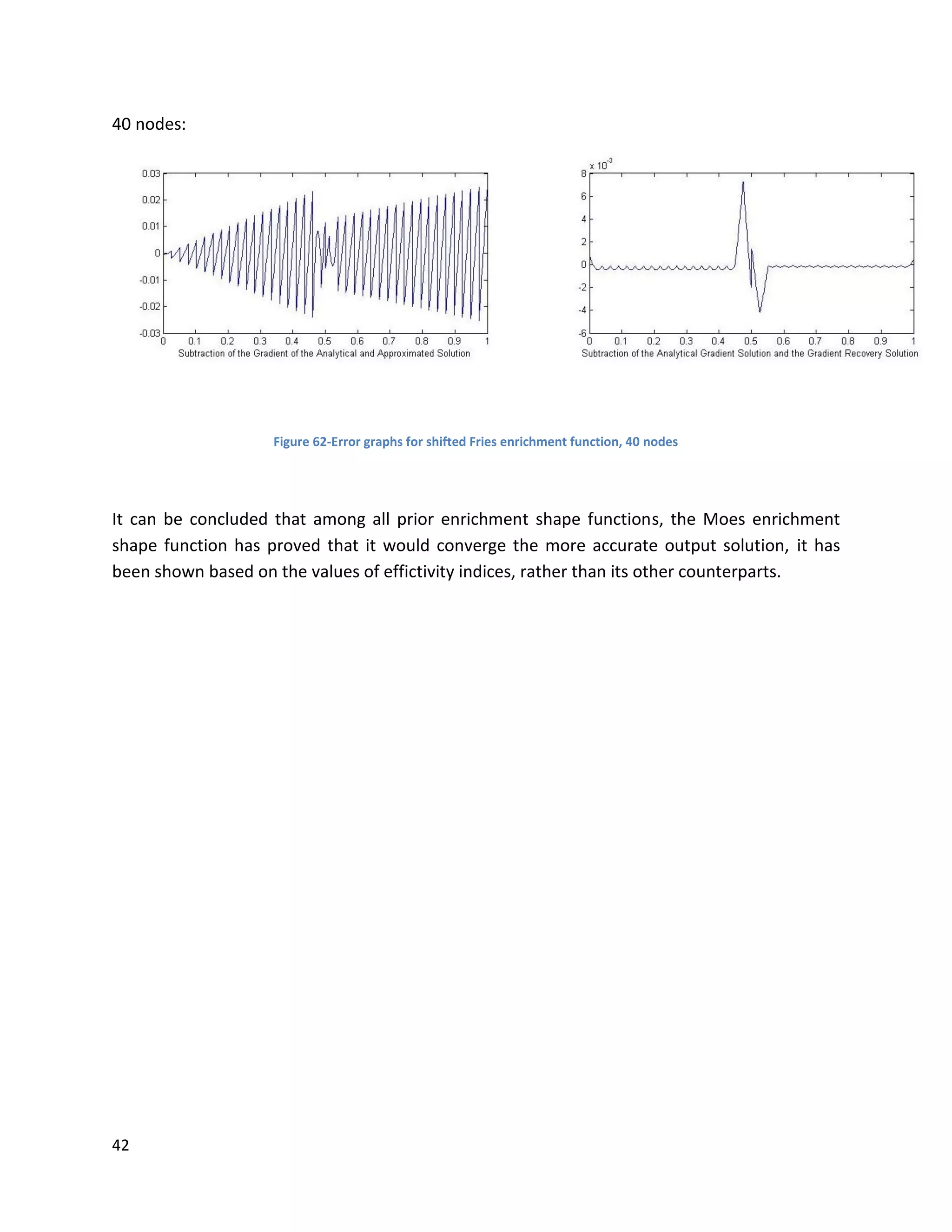

the mesh and the product of nodal shape functions with discontinuous functions. This

construction allows modeling of geometries that are independent of the mesh. Additionally, the

enrichment is added only locally i.e. where the domain needs to be enriched. The resulting

algebraic system of equations consists of two types of unknowns, i.e. standard degrees of

freedom and enriched degrees of freedom. Furthermore, the incorporation of enrichment

functions using the notion of partition of unity ensures the consistency of the solution. All the

above features provide the method with distinct advantages over standard finite element for

modeling arbitrary discontinuities.

1.2. Computational Fracture Mechanics

Of critical importance in computational fracture mechanics is the determination of the

parameters which characterize the stress and displacement field in the vicinity of the crack tip

or of the interface zone. For strong discontinuities, if the stress intensity factors exceed the

critical value of the material, crack growth and ultimately structural failure are possible. Several

strategies have been developed to extract mixed-mode intensity factors using contour integrals

derived from conservation laws. Moran (1987) [17] casts the essential issues in the general

framework of deriving domain integrals from momentum and energy-balance. The equivalent

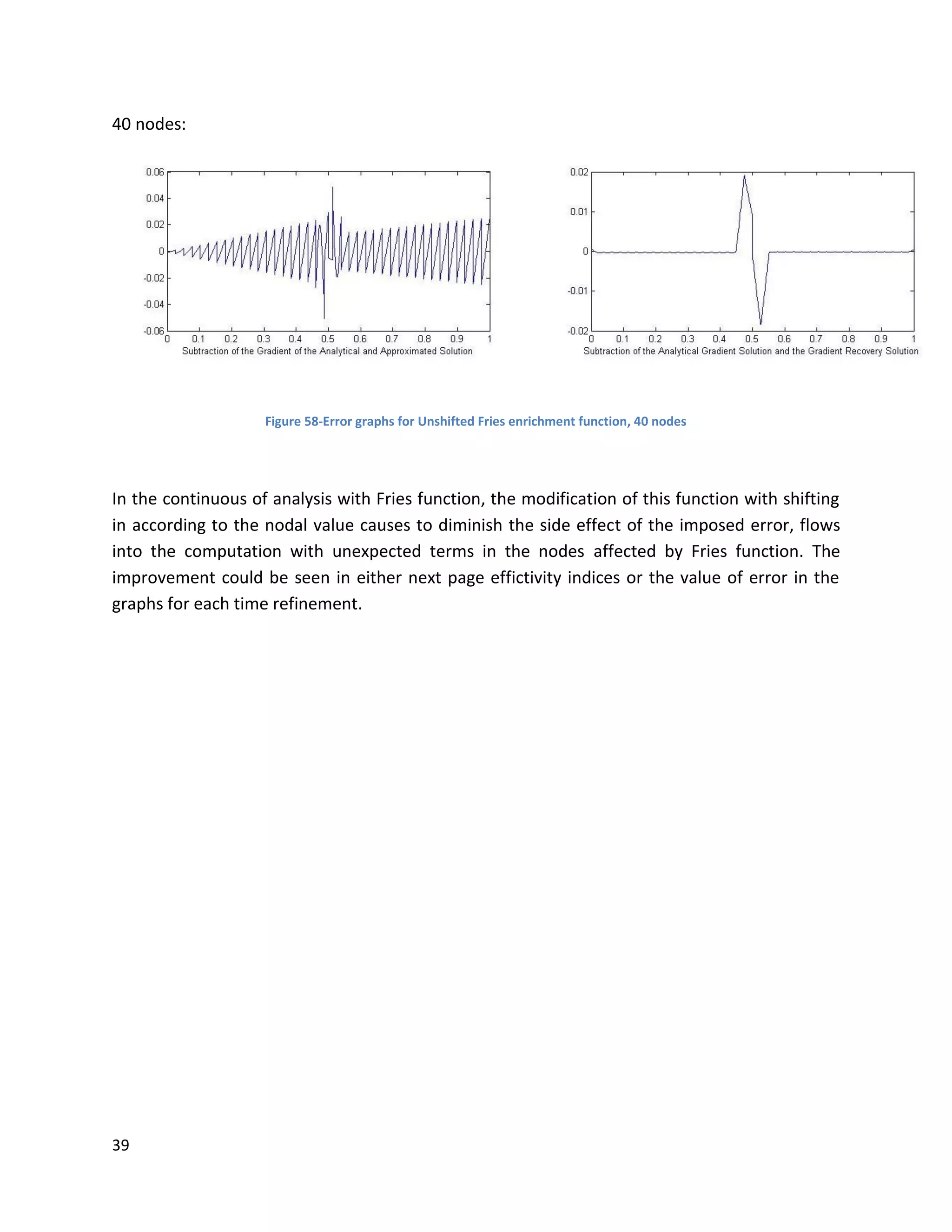

domain integrals are viewed to be better suited for finite element calculations, as the same

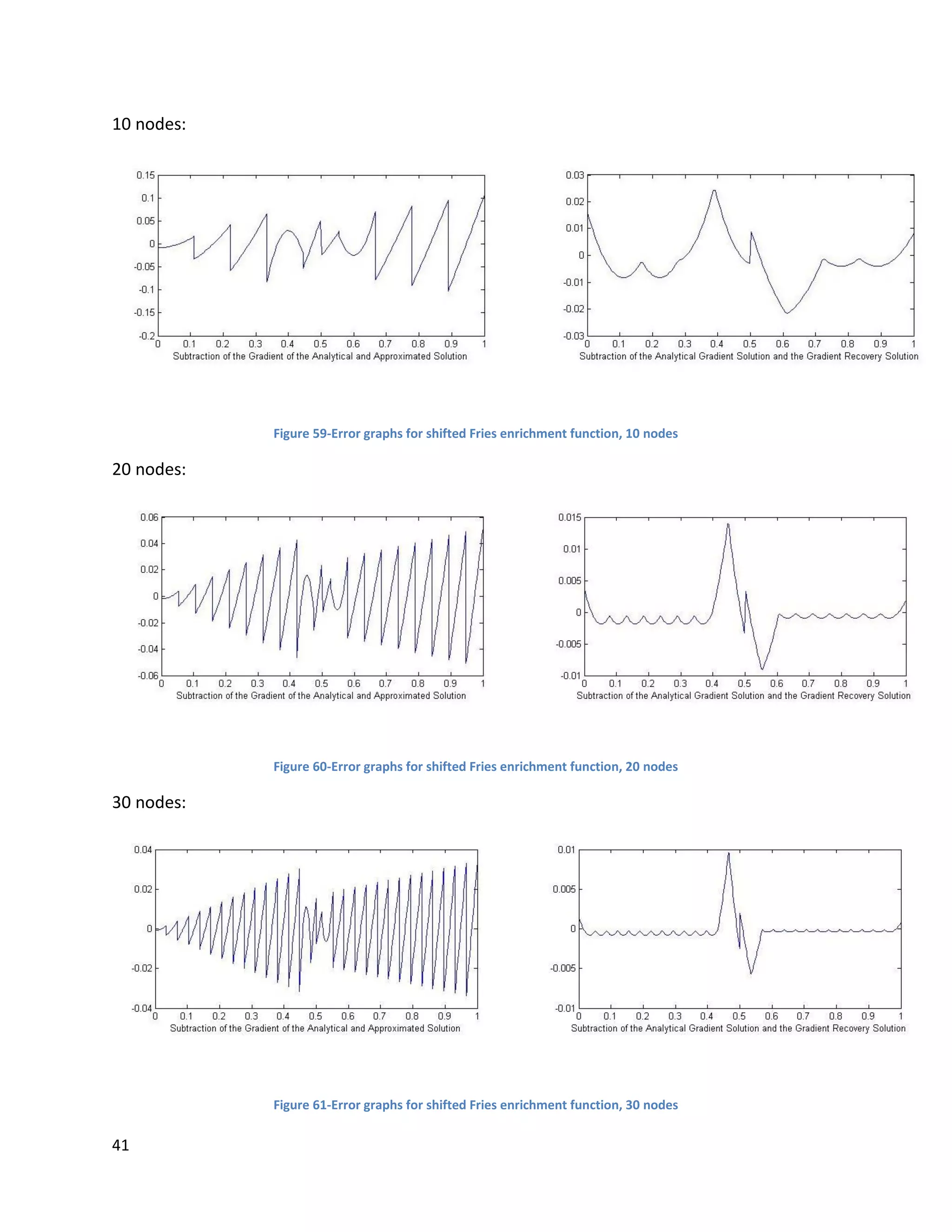

Gauss quadrature points used for the construction of the bilinear form can be used to evaluate

the domain integrals.

A re-meshing technique is traditionally used for modeling discontinuities within the frame-work

of the finite element method. This is done near the discontinuity to align the element edges

with the boundary of discontinuity. This turns to be very expensive in computation only if the

discontinuity evolves in time, which would require generating a new mesh for each time

refinement. This leads to the construction of new shape functions and all the calculations have

to be repeated. Furthermore, the approximation solution is built on a history of previous states,

and whenever the mesh is changed, this history must be preserved. This is accomplished by

interpolation of data from old mesh to new mesh. The process of mapping variables from old

mesh to the new mesh comes with a loss of accuracy.

The idea of enriching the field with an analytical solution in the context of evolving

discontinuities was utilized by Gifford and Hilton (1978) [21], the displacement approximation

for an element was considered to be combination of the usual FEM shape function](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-8-2048.jpg)

![9

displacement and the enriched displacement i.e. 𝑢 = 𝑢 𝑠𝑡𝑑 + 𝑢 𝑒𝑛𝑟 . The enriched part comes

from the displacement in the vicinity of discontinuity. The general idea of enriching the

approximation field was presented in Global-Local methodologies. The basic idea is aimed

towards reaching a global solution using a coarse grid of finite elements and then detailed

results are obtained by zooming to an area of interest (localization zones etc), refining the mesh

in the interest region and using the displacements from the global analysis as an input for the

refined mesh.

The work of Belytschko et al. (1998) [12] is one of the pioneering works toward the local

enrichment of the approximation field at an element level for the localization problems. His

work modified the strain field to get the required jumps in the strain field within the frame-

work of three-field variational principle. The three fields are the displacement 𝒖, strain 𝜖 and

the stress 𝜎. Embedded finite element method (EFEM) uses an element enrichment scheme,

where the field is modified or enriched within the framework of the three-field variational

principle. The enriched approximation to the field in generic from can be expressed as

𝒖 ≈ 𝑵 𝑠𝑡𝑑 𝒅 + 𝑵 𝑒𝑛𝑟 𝒅 𝑒 and 𝜖 ≈ 𝑩 𝑠𝑡𝑑 𝒅 + 𝑩 𝑒𝑛𝑟 𝒅 𝑒, where 𝑵 𝑠𝑡𝑑 and 𝑩 𝑠𝑡𝑑 are the standard FEM

displacement interpolation and strain-displacement interpolation matrices and 𝒅 are the FEM

standard degrees of freedom. 𝑵 𝑒𝑛𝑟 and 𝑩 𝑒𝑛𝑟 are the matrices containing enrichment terms for

the displacement and strain fields. 𝒅 𝑒 is the enriched degree of freedoms and are unknown.

These unknowns are found by imposing Drichlet and Neuwman boundary condition within the

element. The prominent feature in this method is that the enrichment is localized to an

element level. However, this method has a drawback the requirement of continuity along the

path of the crack. Extended finite element method (XFEM) on the contrary is also a local

enrichment scheme but uses the notion of partition of unity to incorporate an enrichment into

the approximating field. In XFEM, instead of an element enrichment scheme, a nodal

enrichment scheme is developed. A prominent feature of the partition of unity in XFEM or in

any partition of unity method is that it automatically enforces the conformity of the global

approximation space.

Extended finite element method (XFEM) introduced by Belytschko and Black (1999) [12] is able

to incorporate the local enrichment into the approximation space within the framework of

finite elements. The resulting enriched space is then capable of capturing the non-smooth

solutions with optimal convergence rate. The main scope of this thesis is to confirm the

convergence rate ratio obtained with XFEM in the case of the unavailability of the analytical

exact solution this is known as a posteriori error estimation.

The partition of unity finite element method (PUFEM) [14] defines set of functions over certain

domain 𝛺 𝑃𝑈𝐹𝐸𝑀

, such that they form a partition of unity, or in other words they sum up to 1.

This property lays on the basic rules of proposition for XFEM, and it corresponds to the ability of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-9-2048.jpg)

![10

the partition of unity shape functions to reproduce a constant, and this is essential for

convergence. The main idea of XFEM (or any partition of unity based method) lies in applying

the appropriate enrichment functions locally in the domain of interest using the partition of

unity. The XFEM brings the capability of tracking the discontinuity with coupling to level set

method. Level set method is a numerical technique to track the discontinuities. It is based on

the idea of defining a function such that the discontinuity is represented as the contour of the

zero level set function. Level set function not only helps in tracking arbitrarily aligned finite

element meshes but also helps in defining the enrichment function.

1.3. A Posteriori Error Estimation in Finite Element Analysis

After the advent of finite element method in the era of numerical simulation and mechanics, it

always brings the concern of error in calculations. Basically, there are two types of error

estimation procedures available. So called a priori error estimators provide information on the

asymptotic behavior of the discretization errors but are not designed to give an actual error

estimate for a given mesh. In contrast, a posteriori error estimators employ the finite element

solution itself to derive estimates of the actual solution errors. Numerical error is intrinsic in

mathematical simulation. No matter how sophisticated the mathematical model of an event is,

it is always subject to error. Discretization error can be large, pervasive, unpredictable by

classical heuristic means, and can invalidate numerical prediction. For these reasons, a

mathematical theory for estimating and quantifying discretization error is of paramount

importance to the computational solution. More importantly, knowledge of approximation

errors in simulation, as well as their distribution and magnitude provides the basis for adaptive

control of the numerical process, the meshing. This includes the choice of algorithms, and

consequently influences the efficiency and the feasibility of the computation. Advances have

been made to find the resolution on the above-mentioned problems a posteriori error

estimation. Besides, the analyst can use a posteriori error estimates as an independent

measure of the quality of the simulation under study, whereby the computed solution itself is

used to assess the accuracy.

These are further differences between the a priori estimation of error and the a posteriori error

estimation. The a priori error estimates give information on the convergence and stability of

various solvers and can give rough information on the asymptotic behavior of errors in

calculations as mesh parameters are appropriately varied. A posteriori error estimation is much

more useful in computational mechanics and in solving partial differential equations. These are

typified by particular algorithms in which the difference in solutions obtained by schemes with

different orders of truncation error is used as a rough estimate of the error. Babuska and

Rheinboldt [19] started the modern definition of a posteriori error estimation for finite element

methods for two point elliptic boundary value problems. Techniques were developed that](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-10-2048.jpg)

![11

delivered numbers ƞ 𝑘 approximating the error in an energy norm on each finite element K.

These formed the basis of adaptive meshing procedures designed to control and minimize the

error.

During the early 1980s several error estimators were introduced for effective adaptive

methods, of which many were based on a priori or interpolation estimates. They provided

crude but effective indications of the error, sufficient to derive adaptive processes. In the mean

time, Zienkiewicz and Zhu [27] developed a simple error estimation technique that is effective

for some classes of problems and types of finite element approximations. Their method is

categorized as a recovery-based method. Gradients of solutions obtained on a particular

partition are smoothed and then compared with the gradients of the original solution to assess

error. Eventually this approach evolved into the superconvergent patch recovery method. The

main scope of a posteriori estimator implementation for this work relies on SPR method, and it

has been expanded to estimate the local error in each element. The estimate is validated by the

effectivity index for either one- or two-dimensional problem.

Extrapolation methods have been used effectively to obtain global error estimates for both the

h and p versions of finite element method [10]. Most studies have dealt with a posteriori error

estimation for the h version of the finite element method. However, the element residual

method is applicable to both p and h-p version finite element approximations. Generally, the

emphasis of a posteriori error estimation runs around the study of robustness of existing

estimators and indentifying limits on their performance. Generally, the main purpose of an

error estimator is to provide an estimate and ideally bounds for the solution error in a specified

norm or in a functional of interest. Some characteristics of an effective error estimator include:

The error estimate should be accurate in the sense that the predicted error is close to

the actual (unknown) error.

The error estimate should be asymptotically correct in the sense that with increasing

mesh density the error estimate should tend to zero at the same rate as the actual

error.

Ideally, the error estimators should yield guaranteed and sharp upper and lower bounds

of the actual error.

The error estimator should be computationally simple, with the error estimate (and

bounds) inexpensive to compute when measured on the total computations of the

analysis.

The error estimator should be robust with regard to a wide range of applications,

including nonlinear analysis.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-11-2048.jpg)

![14

𝑓 𝑥 = 2. 𝑥 (1.4)

If the cross section area for the first segment of bar is 1

2 and for the second part is 1, and the

module of elasticity along the bar is 1, then the exact solution is given by

𝑈 𝑥 =

2

3

∗ 𝑥3

0 < 𝑥 < 0.5 (1.5)

𝑈 𝑥 =

1

3

∗ 𝑥3

+

1

24

0.5 < 𝑥 < 1.0 (1.6)

Note that the displacement is continuous for each point along the bar.

2.1.2. Weak form and discrete system

Consider the static response of elastic bar of two different cross sections such as shown in

fig1. The strong form (2.1) sets in body 𝛺 ∈ ℝ3

with boundary Ƭ is given as:

𝑑

𝑑𝑥

𝐸 𝑥 𝐴 𝑥

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

+ 𝑓 = 0 𝑜𝑛 0 < 𝑥 < 𝑙 (1.7)

As it has been described before, the investigated problem contains the constant module

elasticity; as well as two different cross sectional area joined in the interface location known

as notation of 𝐴1 and 𝐴2 for right and left hand side of interface location, respectively. The

strong form can be developed into the finite element equations by restating the partial

differential equation in an integral form called the weak form (principle of virtual work). To

show how the weak form is developed, the previous strong form equation (2.7) is multiplied

by a weight or test function 𝑤(𝑥) and integrating over the whole domain which is the

interval [0, 𝑙].

𝑤

𝑑

𝑑𝑥

𝐸𝐴(𝑥)

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

𝑑𝑥 + 𝑤𝑓 𝑑𝑥 = 0

𝑙

0

𝑙

0

∀𝑤 ∈ 𝛺 (1.8)

where 𝑢 𝑥 ∈ 𝛺

and 𝑤 ∈ 𝛺

are the approximating trial and test functions used in XFEM.

The 𝛺

contains both the enriched and standard finite element space that the trial function

must satisfy the essential boundary condition, and which include the shape functions that

are discontinuous across the interface location.

To obtain the weak form, we take the advantage of integration by parts for the first

component of equation (2.8) to relate the strong form to the weak form. By the application

of integration by parts the first component of formula (2.8) is expanded and written as:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-14-2048.jpg)

![15

𝑤

𝑑

𝑑𝑥

𝐴 𝑥 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

𝑑𝑥 = 𝑤𝐴 𝑥 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

𝑙

0

𝑙

0

−

𝑑𝑤

𝑑𝑥

𝐴(𝑥)𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

𝑑𝑥

𝑙

0

(1.9)

Now with substitution of (2.9) into (2.8), it would be written as follows:

𝑤𝐴 𝑥 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

𝑙

0

−

𝑑𝑤

𝑑𝑥

𝐴(𝑥)𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

𝑙

0

𝑑𝑥 + 𝑤𝑓 𝑑𝑥 = 0

𝑙

0

(1.10)

The formula (2.10) could be written by expansion of the first term:

(𝑤𝐴2 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

) 𝑥=𝑙 − (𝑤𝐴1 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

) 𝑥=0 −

𝑑𝑤

𝑑𝑥

𝐴(𝑥)𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

𝑙

0

𝑑𝑥 + 𝑤𝑓 𝑑𝑥 = 0

𝑙

0

(1.11)

The second term in the above vanishes because of the essential boundary condition. Also,

the (𝐴2 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

) 𝑥=𝑙 stands as traction boundary condition. Therefore, the above equation

could be rewritten as follows:

𝑑𝑤

𝑑𝑥

𝐴(𝑥)𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

𝑙

0

𝑑𝑥 = (𝑤𝐴2 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

) 𝑥=𝑙 + 𝑤𝑓 𝑑𝑥

𝑙

0

(1.12)

Because of the changing in cross sectional area of bar, the computation for the weak form is

broken up the general formulation of the weak form (2.8) into two compartments in

according to the location of interface. The weak form equation would be derived as

following equations: [put A = a1, a2]

𝑑𝑤

𝑑𝑥

𝑙

2

0

𝐴1. 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

𝑑𝑥 = (𝑤𝐴1. 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

) 𝑙

2

+

𝑤𝑙2

4

(1.13)

𝑑𝑤

𝑑𝑥

𝐴2. 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

𝑑𝑥

𝑙

𝑙

2

= (𝑤𝐴2 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

)𝑙 − (𝑤𝐴2 𝐸

𝑑𝑢

𝑑𝑥

) 𝑙

2

+

3𝑙2

4

𝑤 (1.14)

2.2. Finite Element Solution

The basic characteristic of finite element procedure is determined by the basis functions;

particularly their piecewise smoothness and local support of at least degree 1. In the global

point of view, these basis functions are considered to be defined everywhere on the domain of

the boundary-value problem. The global coordinates are useful in establishing the

mathematical properties of the finite element method. However, the computer](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-15-2048.jpg)

![16

implementation is being carried out on a reference element which is determined by local

coordinates.

The approximated solution 𝑢

is obtained by Galerkin method as a Variational Boundary Value

Problem (VBVP) restricted to the local domain. Each local domain is constructed by partitioning

of the global domain Ω into a set of m subdomains, labeled elements in fig…. Nodes are then

placed at the vertex of each element, for a total of n nodes in the domain. The coordinates of

the nodes are denoted by 𝑥1, 𝑥2, … , 𝑥 𝑛 and the element domains are denoted by 𝛺1, 𝛺2, … , 𝛺 𝑚 .

Associated with each node is a shape function 𝑁𝑖 or 𝛷𝑖, with compact support 𝜔𝑖. The support

of the nodal function is defined to be the union of the elements connected to the node. Fig 2

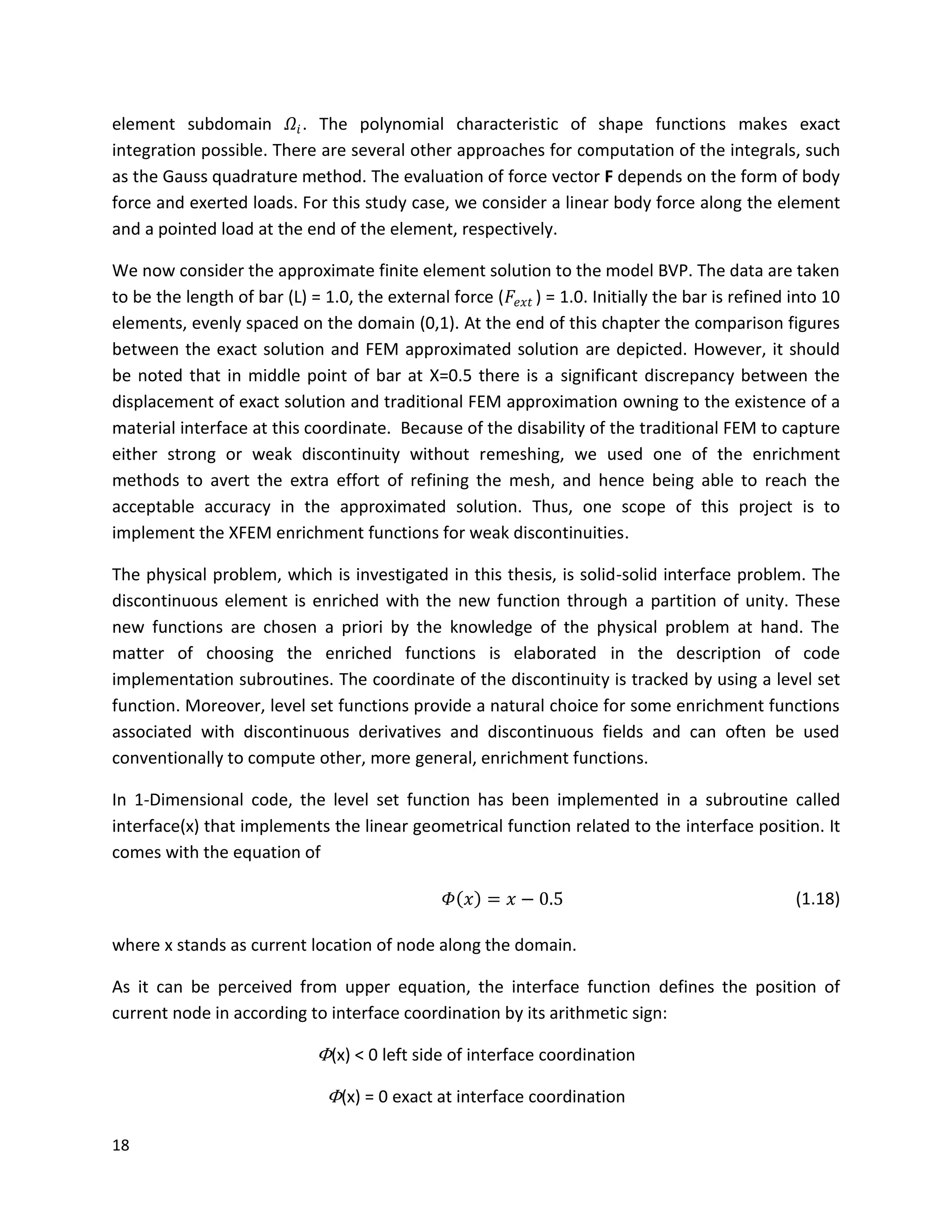

shows a nodal shape function and its support on a typical one- dimensional mesh.

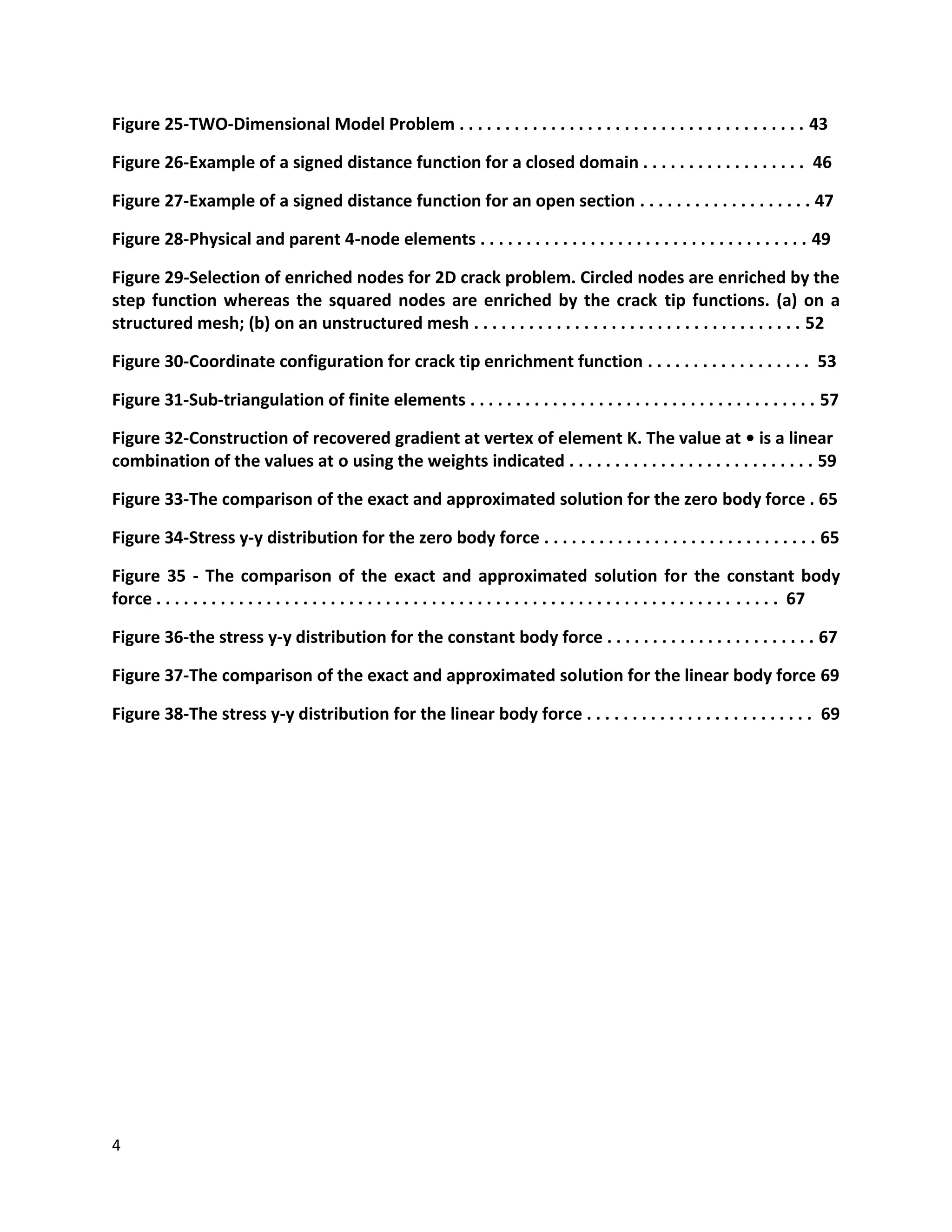

Figure 40-A typical one-dimensional mesh of 4 elements. A linear shape function in corresponding to node 3 with support of

shape function [1].

The finite element approximation in the global domain reads

𝑢

𝑥 = 𝑁𝑖(𝑥)𝑢𝑖

𝑛

𝑖=1

(1.15)

We can write the following properties:

The approximation 𝑢

interpolates the values 𝑢𝑖 of 𝑢 at nodes, i.e 𝑢

𝑥𝑖 = 𝑢𝑖 = 𝑢(𝑥𝑖)

The approximation is continuous, 𝑢

∈ 𝐶0(𝛺)

The approximation is exact for linear functions.

The interpolation property gives the physical meaning to the nodal coefficients 𝑢𝑖 as precisely

the values of the displacement field at the nodes. We shall provide a relation between the

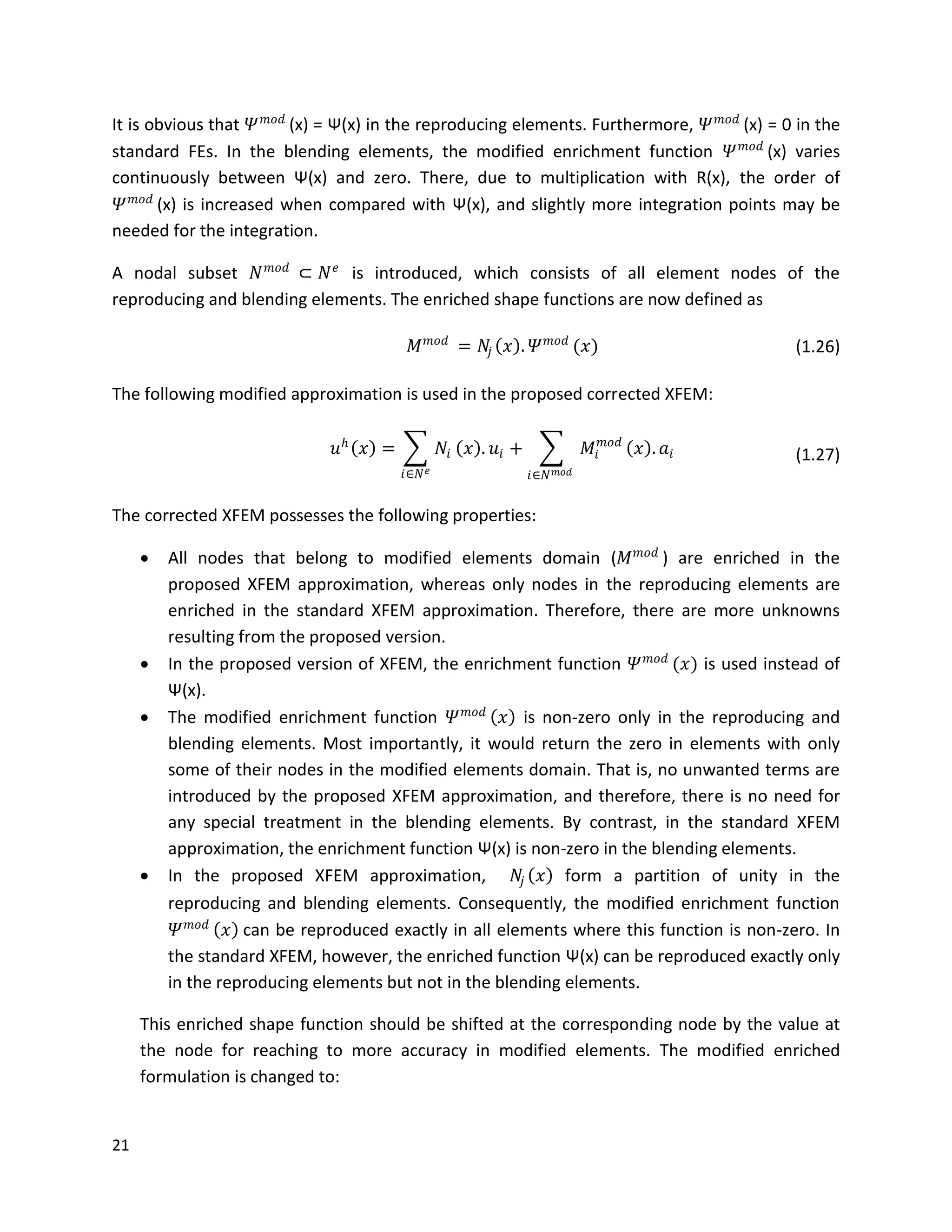

domains of the global and local coordinates by linear function ξ : [𝑥 𝐴, 𝑥 𝐴+1] [𝜉1, 𝜉2], which

satisfies ξ(𝑥 𝐴)=𝜉1 and ξ(𝑥 𝐴+1)=𝜉2. It is standard practice to take 𝜉1=-1 and 𝜉2=+1. The local and

global descriptions of the eth element are depicted in fig 3.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-16-2048.jpg)

![17

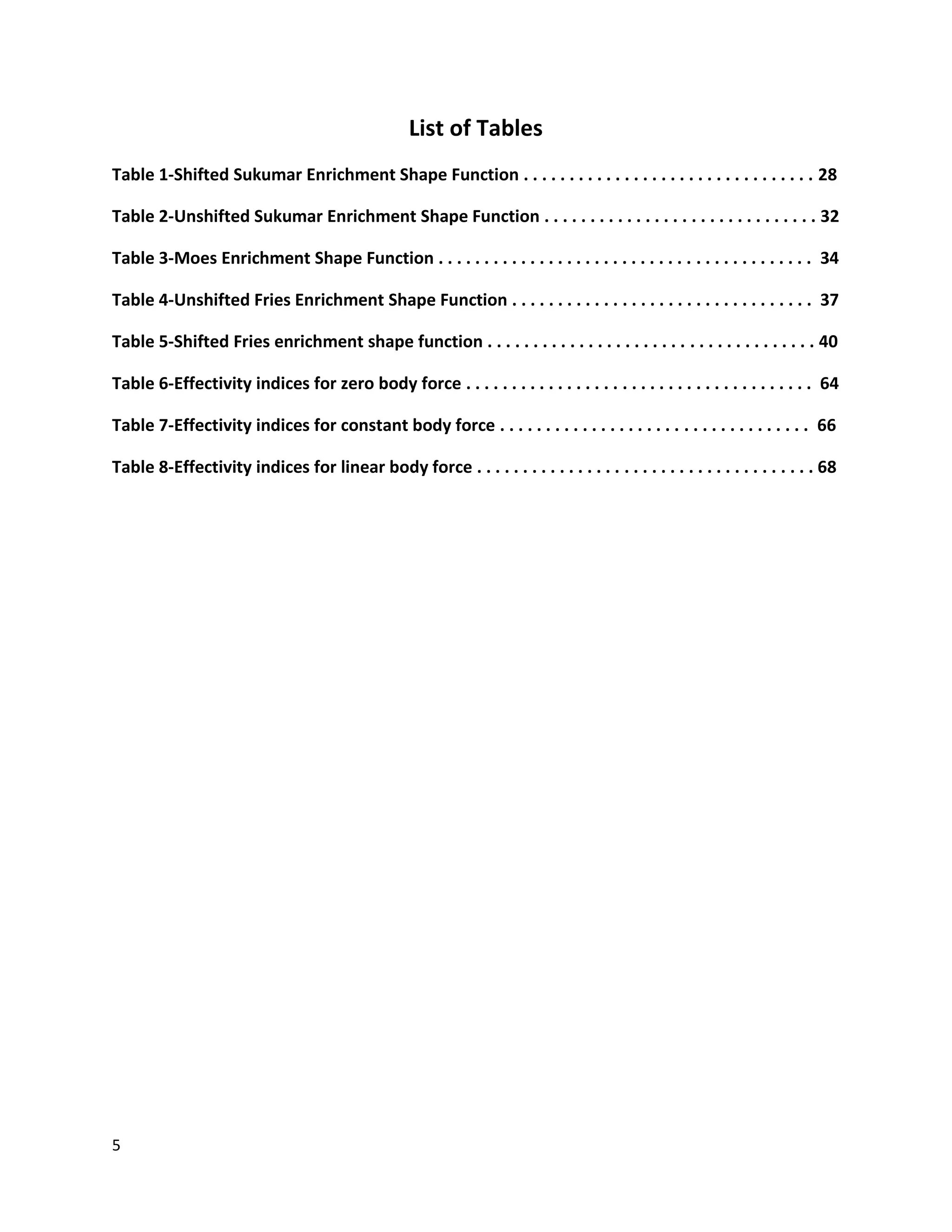

Figure 41-Interpolation between local and global coordinate system [2].

The linear order of the approximation comes with the fact that the shape functions satisfy

𝑁𝑖

𝑖

𝑥 = 1 (1.16)

𝑁𝑖 𝑥 𝑥𝑖 = 𝑥

𝑖

(1.17)

Hence, if the nodal values are prescribed for an arbitrary linear field, the finite element

approximation reproduces the field exactly. The above equations are indicating the reproducing

condition, with the first implying that shape functions form a partition of unity. This property

corresponds to the ability of the approximation to represent rigid body modes, and is closely

tied to the convergence of the method.

Concerning the construction of the stiffness matrix K and the force vector F, the integral over

the domain Ω (integration over all elements) are replaced by a sum of integrals over each](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-17-2048.jpg)

![19

Φ(x) > 0 right side of interface coordination

For each node 2 degree of freedom are allocated. One is dedicated to standard finite element

method, while the other one is spared to be implied for element with discontinuity.

In this code the basic idea of XFEM is implemented with several types of enriched shape

functions. These functions are built as the product of global enrichment functions with some

finite element shape functions. The point x is taken as an arbitrary value in the finite element e.

Denote the element’s nodal set as 𝑁𝑒 = {𝑛1 , 𝑛2 , … , 𝑛 𝑚 𝑒

}, where 𝑚 𝑒 is the number of nodes of

element e. The enriched displacement approximation for a vector-valued function 𝒖

∶ 𝑅 𝑑

→

𝑅 𝑑

is of the form

𝑢

= 𝑁𝐼

𝐼∈𝑁 𝑒

𝑥 𝑢𝐼 + 𝑁𝐽

𝐽∈𝑁 𝑒𝑛𝑟

𝑥 𝛹(𝑥)𝑎𝐽 (1.19)

Where the 𝑁 𝑒𝑛𝑟

is set of nodes whose support is cut by discontinuity, and 𝑁𝑒 is set of nodes

that are not enriched. 𝑁𝐼 and 𝑁𝐽 are finite element shape functions. The choice of enriched

function (Ψ(x)) depends on a priori solution of the problem. The 𝑢𝐼 is the nodal unknown as

well as 𝑎𝐽 for standard finite elements and enriched elements, respectively. 5 different types of

these functions have been implemented in this code, and subsequently the intrinsic estimated

error for each approximated solution is compared.

Moreover, for those enriched shape functions that brings an additional term in approximated

solution, the enriched function is shifted according to the value of the enriched function in

corresponding node. The modified approximation becomes:

𝒖

= 𝑁𝐼

𝐼∈𝑁 𝑒

𝑥 𝒖𝐼 + 𝑁𝐽

𝐽∈𝑁 𝑒𝑛𝑟

𝑥 (𝛹 𝑥 − 𝛹 𝑥𝐽 )𝑎𝐽 (1.20)

The first choice of enriched shape function is suggested by Sukumar [24], known as the signed

distance shape function. The second type is shifted version of this enrichment. The equation for

Sukumar enrichment is

𝛹 𝑥 = 𝛷(𝑥) (1.21)

and the shifted enrichment is

𝛹 𝑥 = 𝛷(𝑥) − 𝛷(𝑥𝑖) (1.22)

Both of these enriched shape function however, lead to issues with the blending between the

enriched and unenriched elements. The existence of blending elements imposes extra error in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-19-2048.jpg)

![20

approximated solution, as a result deteriorate the convergence rate. It all comes through two

main properties of blending elements: i) In these elements, the enrichment function can no

longer be reproduced exactly (because of a lack of a partition of unity). ii) These elements

produce unwanted terms into the approximation which cannot be compensated by standard FE

part of the approximation. Hence, Prof. Moes [4] and his co-workers used a new enriched

shape function which is able to eliminate the problems in the blending elements with the

enhancement of geometrical configuration and extra degree of freedom. The modified

equation of this enriched function is given by an interpolation of nodal values minus the

absolute value of the common ramp function, illustrated as:

𝛹 𝑥 = 𝑁. 𝛷(𝑥𝑖) − 𝛷(𝑥) (1.23)

where N denotes to standard shape function.

As could be perceived at the end of this chapter, this enriched shape function leads to the most

optimal enrichment among the other implemented enriched shape functions.

Another special treatment was proposed to eliminate the unwanted terms by Prof.Fries [3].

This new approached is known as modified or corrected XFEM, whereas the original definition

is called standard XFEM. Two significant differences can be found in the approximation of the

standard and corrected XFEM: i) In addition to those nodes that are enriched in the standard

XFEM, all nodes in the blending elements are enriched. That is, a complete partition of unity is

present in the reproducing and blending elements. ii) The enrichment functions of the standard

XFEM are modified except in the reproducing elements. These are element with all nodes being

enriched that are capable of reproducing the enriched function exactly. The enrichment

functions are zero in the standard FEs, and in the blending elements, they are multiplied by a

function that varies continuously between 0 and 1.(also called a ramp function) With the aid of

corrected XFEM there are no more unwanted terms in the blending elements.

The modified enrichment function is defined with 𝛹 𝑚𝑜𝑑

(x) as

𝛹 𝑚𝑜𝑑

𝑥 = 𝛹 𝑥 . 𝑅(𝑥) (1.24)

With R(x) being a ramp function

𝑅 𝑥 = 𝑁𝑗 (𝑥)

𝑗∈𝑁 𝑒𝑛𝑟

(1.25)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-20-2048.jpg)

![23

In order to calculate the energy norm, the gradient of both true and approximated solution is

considered. An a priori error estimator in energy norm is:

𝑢 − 𝑢 𝐸

2

= ∇𝑢 − ∇𝑢

2

𝑑𝑥 ≤ 𝐶 𝑝

𝑢 𝑃+1

(1.30)

As it could be seen from two former equations, the accuracy of the approximation in 𝐿2

norm is

one power of h higher than energy norm of the error. The estimation of the error depends on

the unknown constant e and the term 𝑢 𝑃+1 which in general is also not known. To get an

error estimator that does not depend on unknown constants, we need to study a posteriori

error estimators, which are based on the approximated solution itself.

A reasonable a posteriori error estimator can be obtained by using a suitable approximation to

the gradient in place of ∇𝑢. In particular, the gradient of the exact solution could be

approximated by a suitable post-processing of the finite element approximation, denoted by

𝐺 [𝑢 ].

The a posteriori error estimator is then simply taken as

ƞ2

= 𝐺 − ∇𝑢

2

𝑑𝑥 (1.31)

This approach allows considerable leeway in the selection of the post-processed gradient, as it

has already been mentioned the gradient of the finite element approximation provides a

discontinuous approximation to the true gradient. One possible approach that overcomes this

problem is the use of averaging methods. The idea is to construct an approximation at each

node by averaging the contribution from each of the elements surrounding the node. These

values may then be interpolated to obtain a continuous approximation over the whole domain.

The specific steps used to construct the averaged gradient at the nodes distinguish the various

estimators and have a major influence on the accuracy and robustness of the resulting

estimator. The several available rigorous approaches for computation of estimators lay within

the framework of corresponding to a particular recovered gradient 𝐺𝑥.

The implementation of the gradient recovery will be elaborated in several steps. The first step is

to define the procedure for smoothing the gradient of the finite element approximation. The

recovered gradient is denoted by 𝐺 (𝑢 ), where 𝑢 is the finite element approximation. The

recovered gradient is itself piecewise linear, with values at the nodes obtained by first

interpolating the gradient of the finite element approximation at the centroids of the elements

sharing the node. In each element 𝐾 the estimator is defined as](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-23-2048.jpg)

![25

The quality of an estimator is often judged by global effectivity indices

𝜃 =

ƞ

𝑒

or local effectivity indices

𝜃 𝑘 =

ƞ 𝑘

ƞ 𝑘

These indices can be used to measure the quality of an estimator when the exact error or a

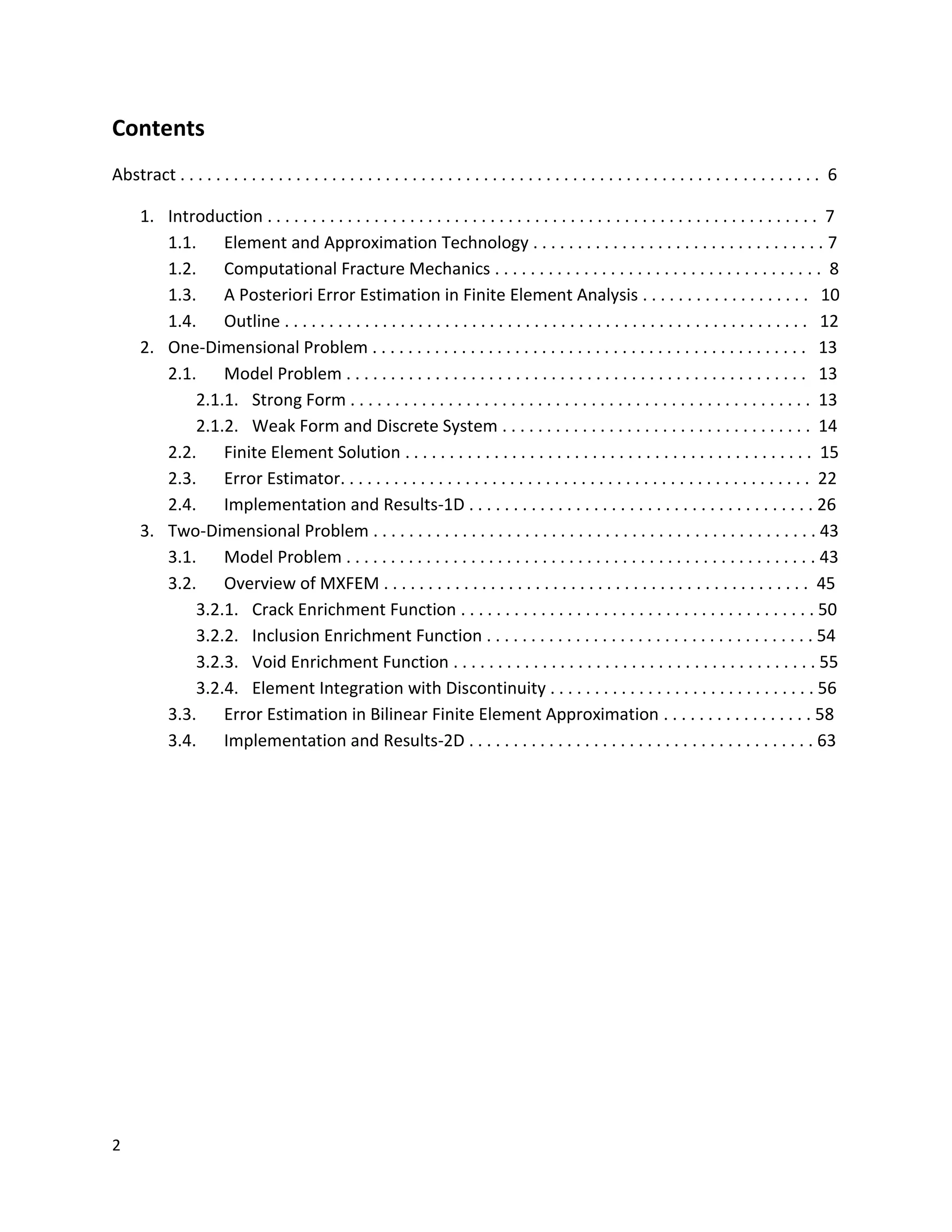

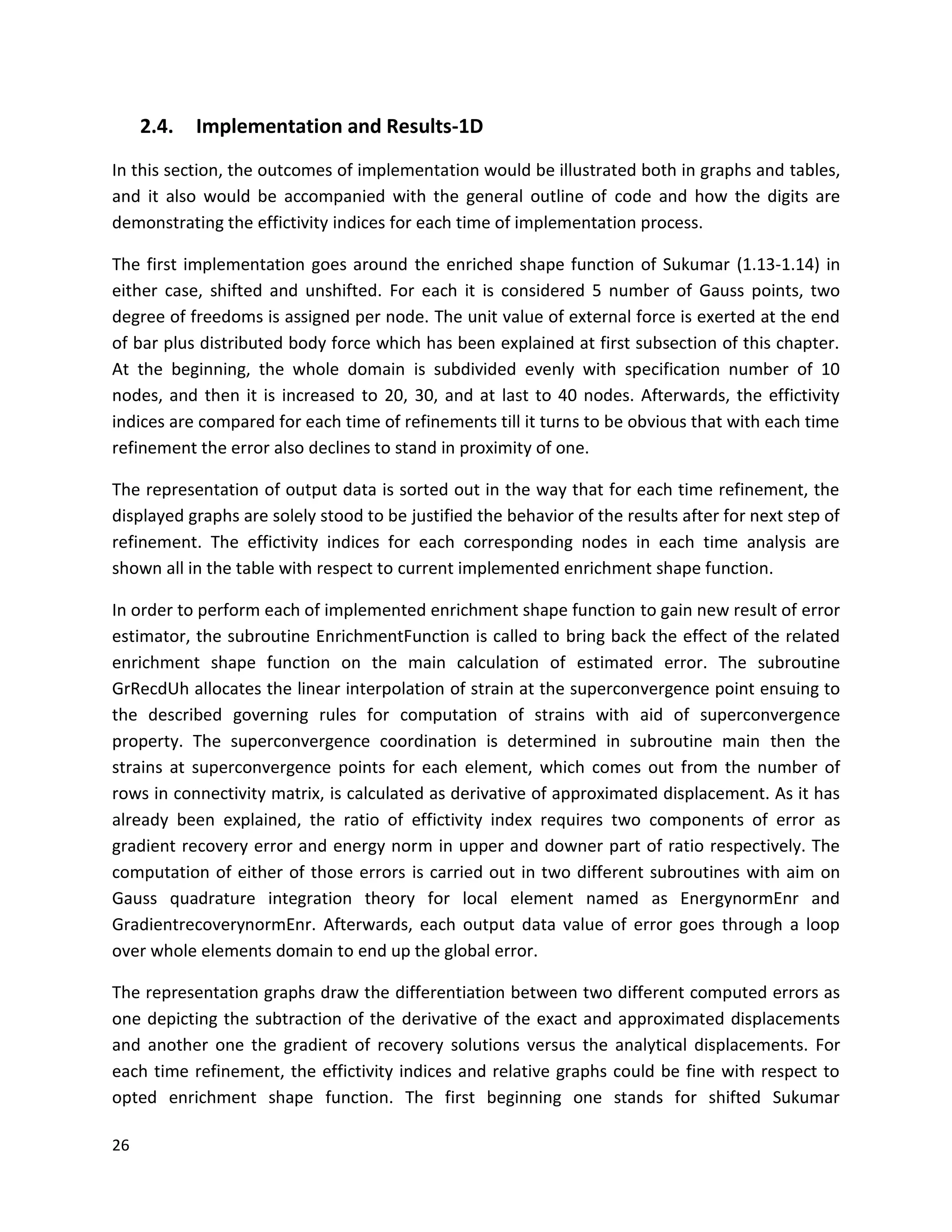

good approximation of it are known. The comprehension of previous concepts gives the rule of

the error estimator implementation for post-processing finite element belonged to one

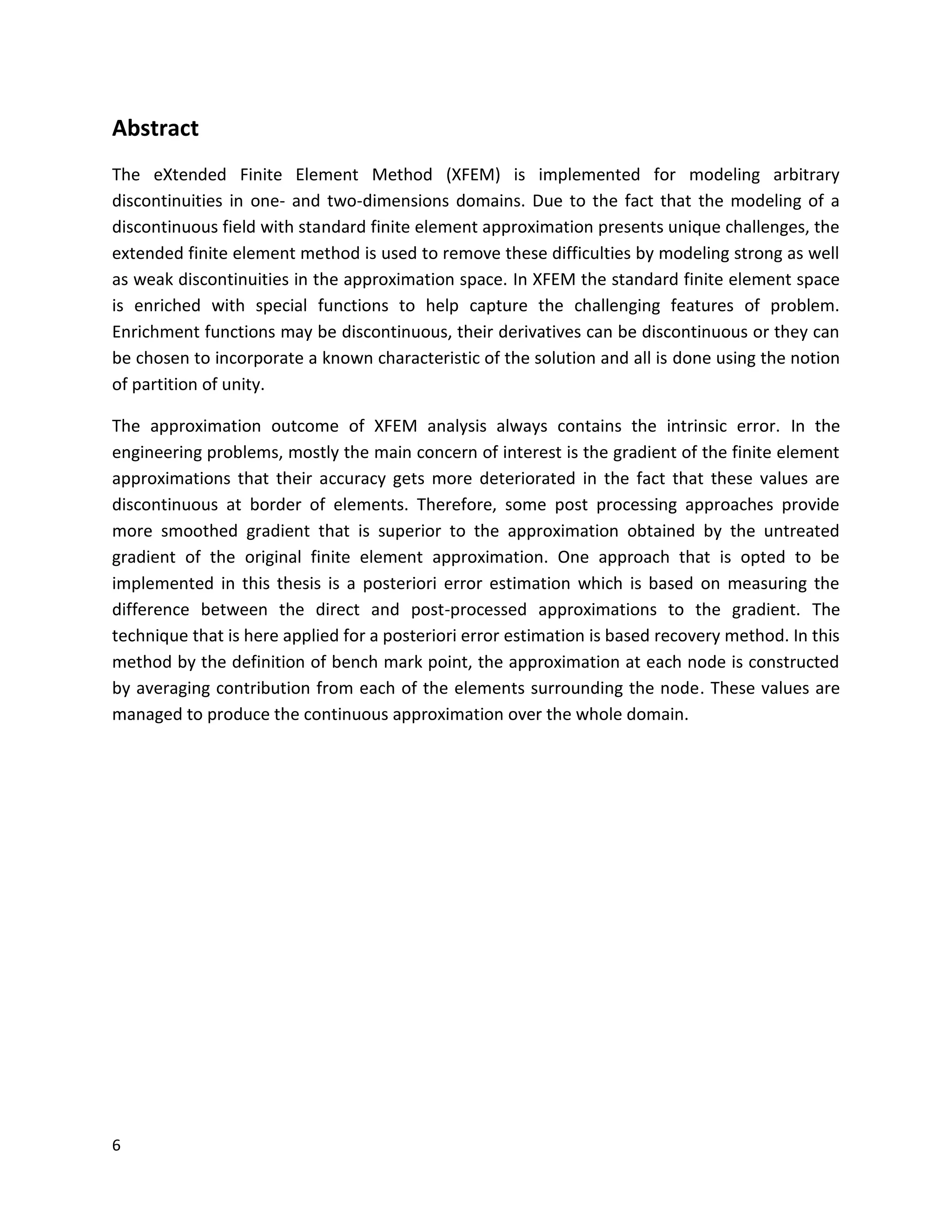

dimensional problem code. Its whole orientation can be summarized in following figure:

Figure 42-Construction of recovery operator 𝑮 𝒉 from piecewise linear approximation in one dimension [9].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-25-2048.jpg)

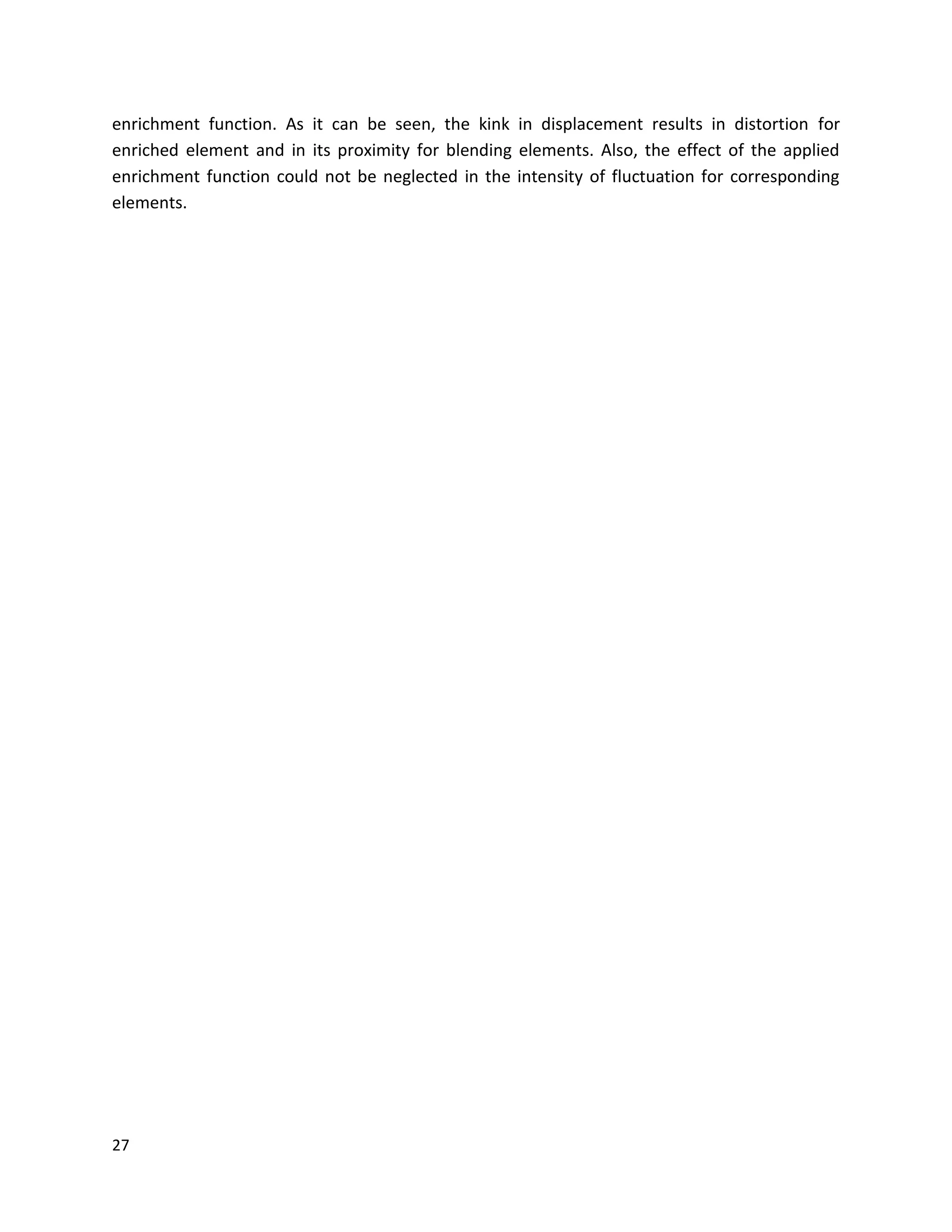

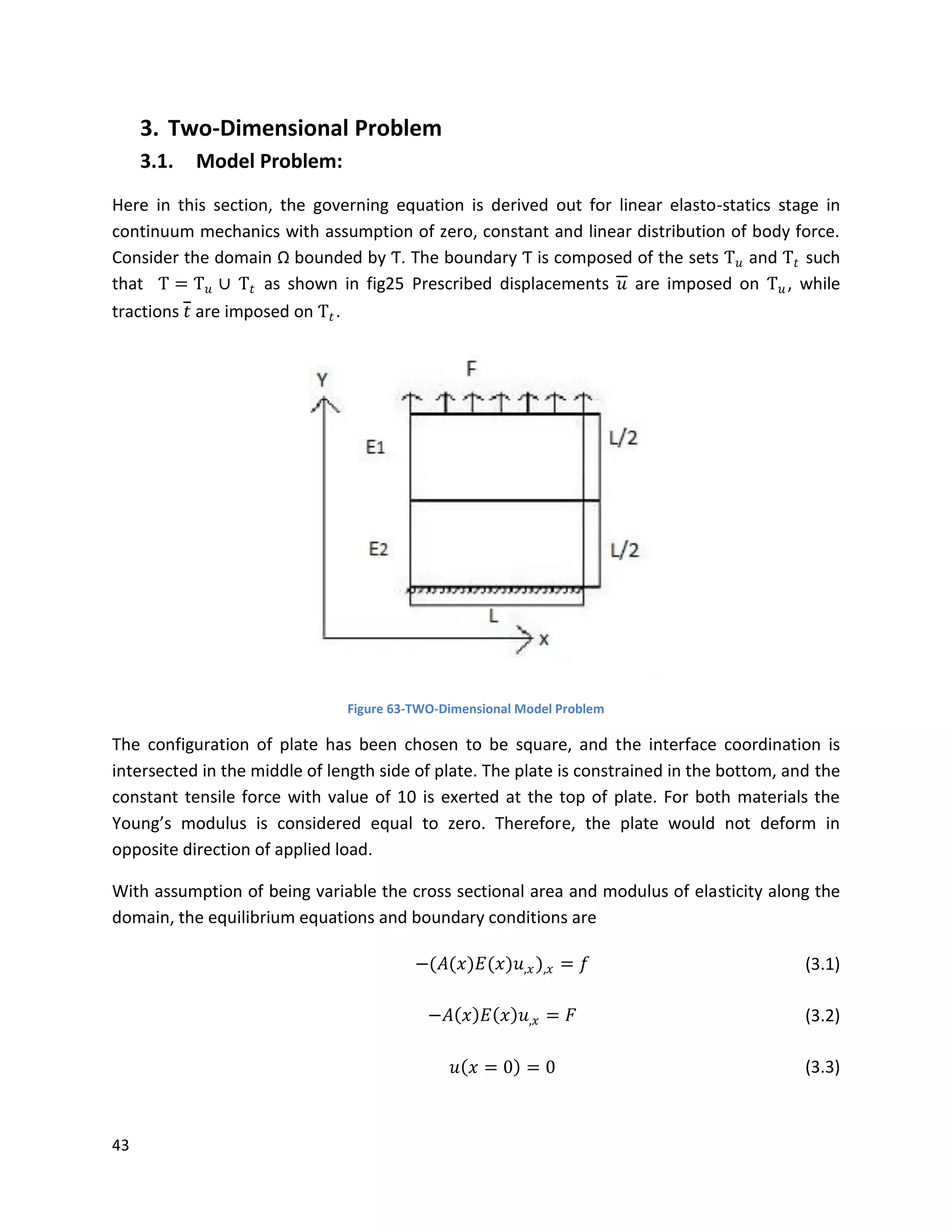

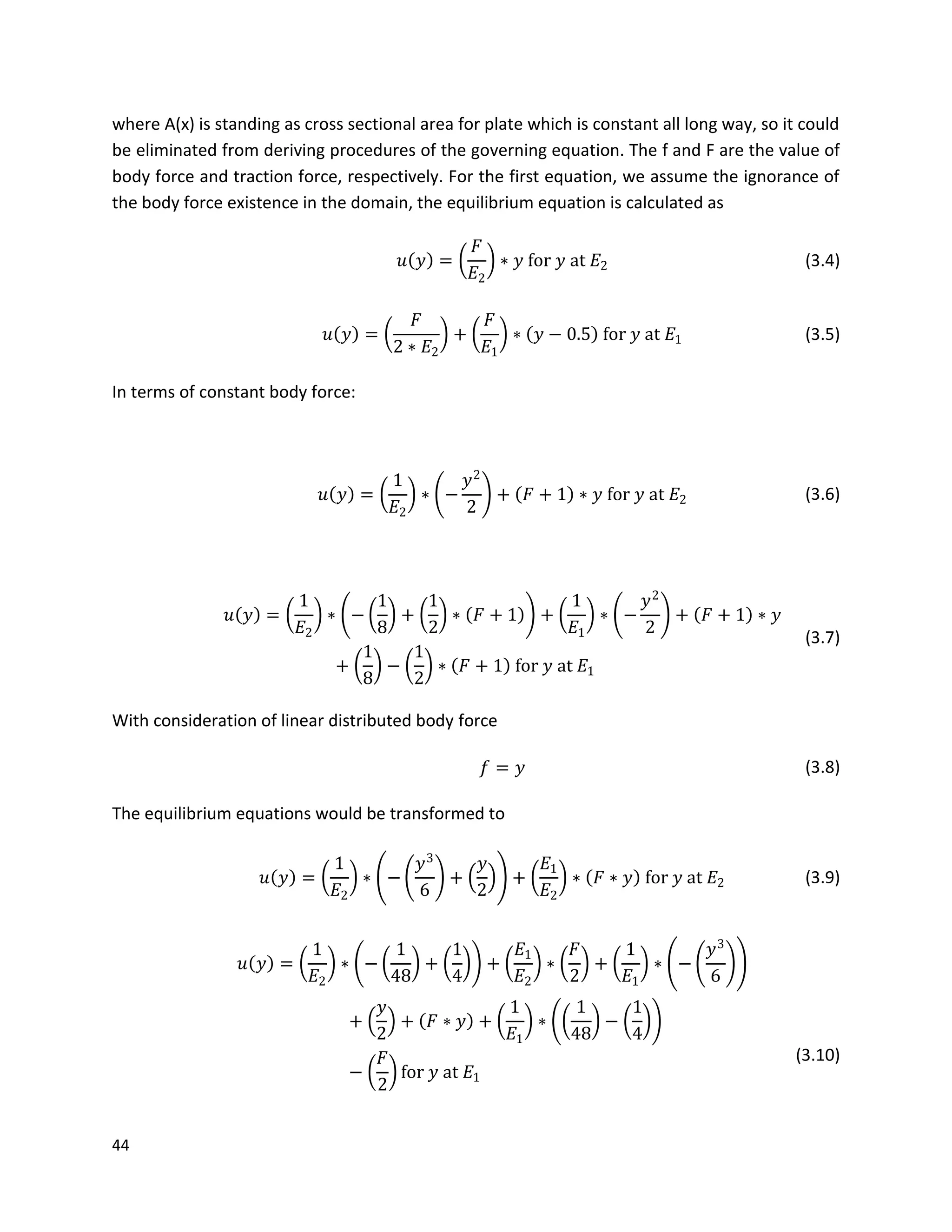

![46

𝛷 𝑥 𝑡 , 𝑡 ≤ 0 (3.15)

𝛹 𝑥 𝑡 , 𝑡 = 0 (3.16)

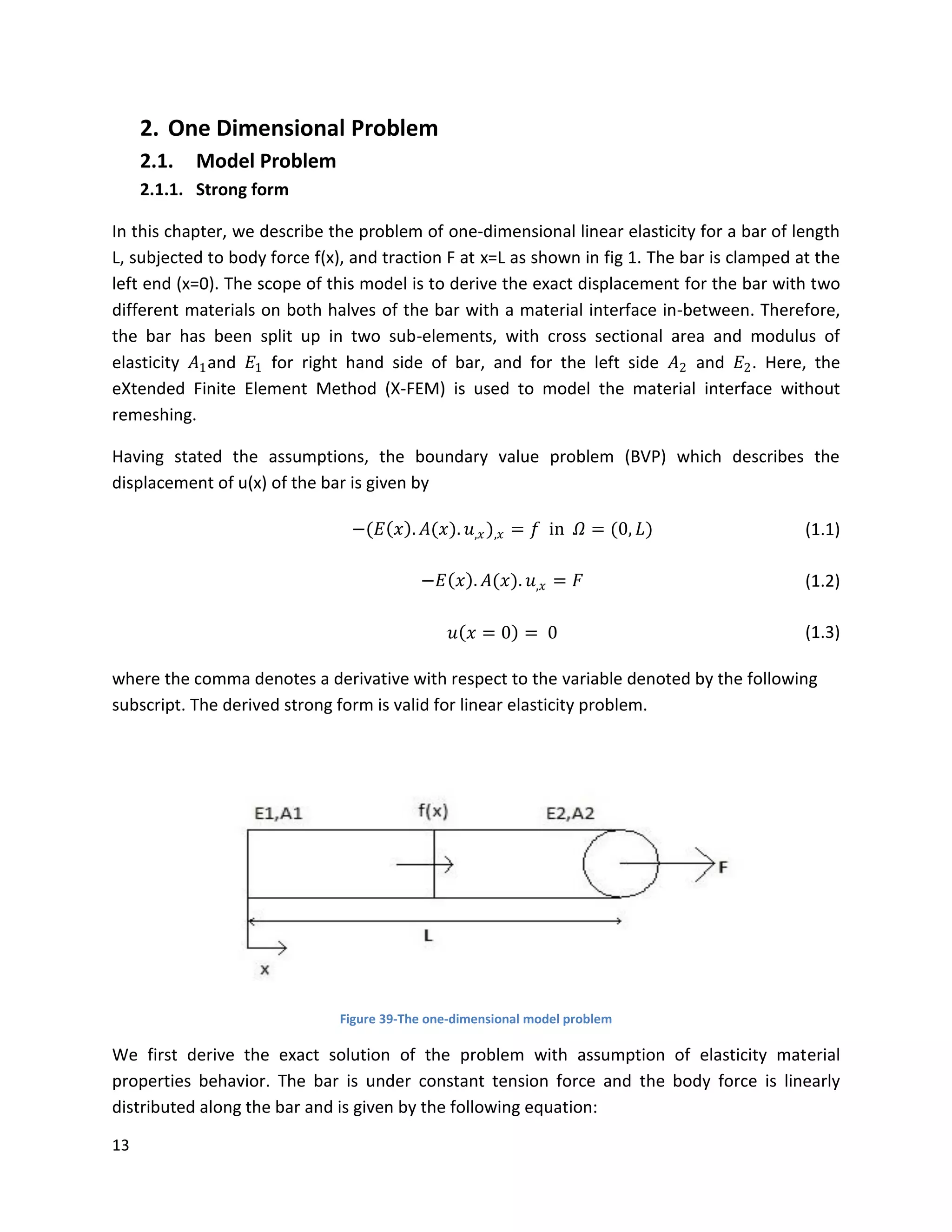

The defined level set function goes for closed domain like as fig….

Figure 64-Example of a signed distance function for a closed domain [15].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-46-2048.jpg)

![47

Figure 65-Example of a signed distance function for an open section [15].

The general implementation form of XFEM is similar to what has been described in 1-D;

nonetheless, it is expanded to one dimension higher. Here again by exploiting the partition of

unity finite element method (PUFEM), the discontinuities are simulated independent of finite

element mesh. The XFEM gives the viability to catch a non-smooth behavior of field variables,

such as stress across the interface of dissimilar materials or displacement across cracks, with

adding the enrichment functions to the displacement approximation as long as the partition of

unity is satisfied. Some additional degrees of freedom are introduced in all elements where

discontinuity is present, and due to type of enrichment functions, possibly some neighboring

elements which are known as blending elements.

In the XFEM the approximation takes the form

𝑢

= 𝑁𝐼(𝑥)

𝐼

[𝑢𝐼 + 𝑣 𝐽

(𝑥)

𝐽

𝑎𝐼

𝐽

] (3.17)

where 𝑢𝐼 are the classical finite element degrees of freedom (DOF), 𝑣 𝐽

𝑥 is the Jth

enrichment function at the Ith node, and 𝑎𝐼

𝐽

are the enriched DOF corresponding the Jth

enrichment function at the Ith node. On owing to introduction of enrichment functions into

approximation solution, the additional calculations are required to calculate the physical

variable, and hence the interpolation property does not satisfy in straight step, 𝑢𝐼 = 𝑢

(𝑥𝐼).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-47-2048.jpg)

![48

The interpolation property is important in practice in applying boundary or contact conditions.

Therefore, it is common practice to shift the enrichment function such that

𝛾𝐼

𝐽

𝑥 = 𝑣 𝐽

− 𝑣𝐼

𝐽

(𝑥) (3.18)

where 𝑣𝐼

𝐽

𝑥 is the value of the Jth enrichment function at the Ith node. The shifted enrichment

function is able to satisfy 𝑢𝐼 = 𝑢

(𝑥𝐼) and assign a value of zero to all standard FEM nodes. The

shifted displacement approximation is given by

𝑢

= 𝑁𝐼(𝑥)

𝐼

[𝑢𝐼 + 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

(𝑥)

𝐽

𝑎𝐼

𝐽

] (3.19)

The Hook’s equation in linear elastic problem indicates the formulation as

𝒌𝒒 = 𝒇 (3.20)

where K is global stiffness matrix, q are nodal degree of freedom, and f are external forces. The

global stiffness matrix can be rearranged in order to

K=

𝒌 𝑢𝑢 𝒌 𝑢𝑎

𝒌 𝑎𝑢

𝑇

𝒌 𝑎𝑎

where 𝒌 𝑢𝑢 is the classical finite element stiffness matrix, 𝒌 𝑎𝑎 is enriched finite element stiffness

matrix, and 𝒌 𝑢𝑎 is a combination of the classical and enriched stiffness matrix components.

Each component of global stiffness matrix K is computed by the integration such as

𝑲 𝑒 = 𝑩 𝛼

𝑇

𝑪𝑩 𝛽 𝑑𝛺 𝛼, 𝛽 = 𝑢, 𝑎 (3.21)

where C is the constitutive matrix for an isotropic linear elastic material, 𝑩 𝑢 is the classical

strain-displacement matrix, and 𝑩 𝑎is the enriched strain-displacement matrix. Both strain-

displacement matrices are illustrated like

𝑩 𝑢 =

𝑁𝐼,𝑥 0 0

0 𝑁𝐼,𝑦 0

0 0 𝑁𝐼,𝑧

0 𝑁𝐼,𝑧 𝑁𝐼,𝑦

𝑁𝐼,𝑧 0 𝑁𝐼,𝑥

𝑁𝐼,𝑦 𝑁𝐼,𝑥 0

; 𝑩 𝑎 =

(𝑁𝐼 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

),𝑥 0 0

0 (𝑁𝐼 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

),𝑦 0

0 0 (𝑁𝐼 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

),𝑧

0 (𝑁𝐼 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

),𝑧 (𝑁𝐼 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

),𝑦

(𝑁𝐼 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

),𝑧 0 (𝑁𝐼 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

),𝑥

(𝑁𝐼 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

),𝑦 (𝑁𝐼 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

),𝑥 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-48-2048.jpg)

![49

where each matrix constitutes from derivative of either standard or enriched shape function

with respect to each corresponding axis.

It is going to be apparent that the shape function matrix contains the same number of columns

as in the strain-displacement matrix, whose components for the 4-node planar element is used

as in fig…

Figure 66-Physical and parent 4-node elements [5].

The shape functions 𝑁𝐼 (I from 1 to 4) are bi-linear in r and s (coordinates in the parent

element):

𝑁1 =

1

4

(1 − 𝑟)(1 − 𝑠) (3.22)

𝑁2 =

1

4

(1 + 𝑟)(1 − 𝑠) (3.23)

𝑁3 =

1

4

(1 + 𝑟)(1 + 𝑠) (3.24)

𝑁4 =

1

4

(1 − 𝑟)(1 + 𝑠) (3.25)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-49-2048.jpg)

![50

The interpolation of the displacement or nodal DOF from parent element to physical element

with aid of shape functions are carried on as

𝑢 𝑒

𝑀 = 𝑁 𝑒

𝑀 𝑞 𝑒 (3.26)

As if

𝑁 𝑒

𝑀 = [𝑁𝑠𝑡𝑑

𝑒

𝑀 𝑁𝑒𝑛𝑟

𝑒

𝑀 ]

The q and f matrices are both identically given by

𝒒 𝑇

= {𝒖 𝒂} 𝑇

where u and a are vectors of the classical and enriched degrees of freedom and

𝒇 𝑇

= {𝒇 𝑢

𝑇

𝒇 𝑎

𝑇

}

where 𝒇 𝑢 and 𝒇 𝑎 are vectors of the applied forces for the classical and enriched components of

the global force matrix. The vectors 𝒇 𝑢 and 𝒇 𝑎 are given by calculation of tractions t and body

forces b over whole domain in the way as

𝒇 𝑢 = 𝑁𝐼 𝑡 𝑑Ƭ + 𝑁𝐼 𝑏 𝑑𝛺 (3.27)

and

𝒇 𝑎 = 𝑁𝐼 𝑡 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

𝑑Ƭ + 𝑁𝐼 𝑏 𝛾𝐼

𝐽

𝑑𝛺 (3.28)

The stress and strain should be calculated in the sense of consideration for realizing the

discontinuity. Therefore, the strain and stress may be computed as

𝜀 = 𝑩 𝑢 𝑩 𝑎 {𝑢 𝑎} 𝑇 (3.29)

and

𝜎 = 𝐶𝜀 (Constitutive Equation) (3.30)

3.2.1 Crack Enrichment Function

In general, XFEM is used to describe the discontinuity as either weak or strong. A strong

discontinuity can be considered one where both the displacement and strain are discontinuous,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-50-2048.jpg)

![52

Figure 67-Selection of enriched nodes for 2D crack problem. Circled nodes are enriched by the step function whereas the

squared nodes are enriched by the crack tip functions. (a) on a structured mesh; (b) on an unstructured mesh [5].

The B-branch functions as crack tip enrichment functions in isotropic elasticity are provided

from the asymptotic displacement fields.

𝑩 ≡ 𝐵1, 𝐵2, 𝐵3, 𝐵4 = [ 𝑟 sin

𝜃

2

, 𝑟 cos

𝜃

2

, 𝑟 sin

𝜃

2

cos 𝜃 , 𝑟 cos

𝜃

2

cos 𝜃]

Here, r and 𝜃 are polar coordinates in the local crack tip coordinate system as shown in fig…

The first element of branch function represents the discontinuity near the tip, while the other

three functions help to get accurate result with relatively coarse meshes. It has not been

proved yet by adding higher order terms in the asymptotic expansion of the near-tip fields

substantially enhance the improvement of solution.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-52-2048.jpg)

![53

Figure 68-Coordinate configuration for crack tip enrichment function [5].

Because the XFEM mesh does not need to conform to the domain, a method must be used to

track of the location of the cracks. Those mentioned level set functions are going to shed the

light to find the crack path. The zero level set of 𝛹(𝑥) represents the crack body, while the zero

level sets of 𝜑(𝑥), which is orthogonal to the zero level set of 𝛹(𝑥), represents the location of

the crack tips. The enrichment functions in terms of 𝜑(𝑥) and 𝛹(𝑥) can be noticed such as

𝑥 = 𝛹 𝑥 =

+1 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝛹(𝑥) > 0

−1 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝛹(𝑥) < 0

(3.34)

Furthermore, the polar crack tip coordinates are given as

𝑟 = 𝛹2 𝑥 + 𝛷2(𝑥) and 𝜃 = tan−1 𝛹(𝑥)

𝛷(𝑥)

The enrichment of nodes according to crack tip enrichment can also be determined through the

use of level set functions defining the crack. Consider an element where the maximum and

minimum values of 𝛹(𝑥) and 𝜑(𝑥) are given as 𝛹𝑚𝑎𝑥 , 𝛹 𝑚𝑖𝑛 , 𝛷 𝑚𝑎𝑥 , and 𝛷 𝑚𝑖𝑛 . Then an element

is enriched with the Heaviside enrichment when

𝛷 𝑚𝑎𝑥 <0 and 𝛹𝑚𝑎𝑥 𝛹 𝑚𝑖𝑛 ≤ 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-53-2048.jpg)

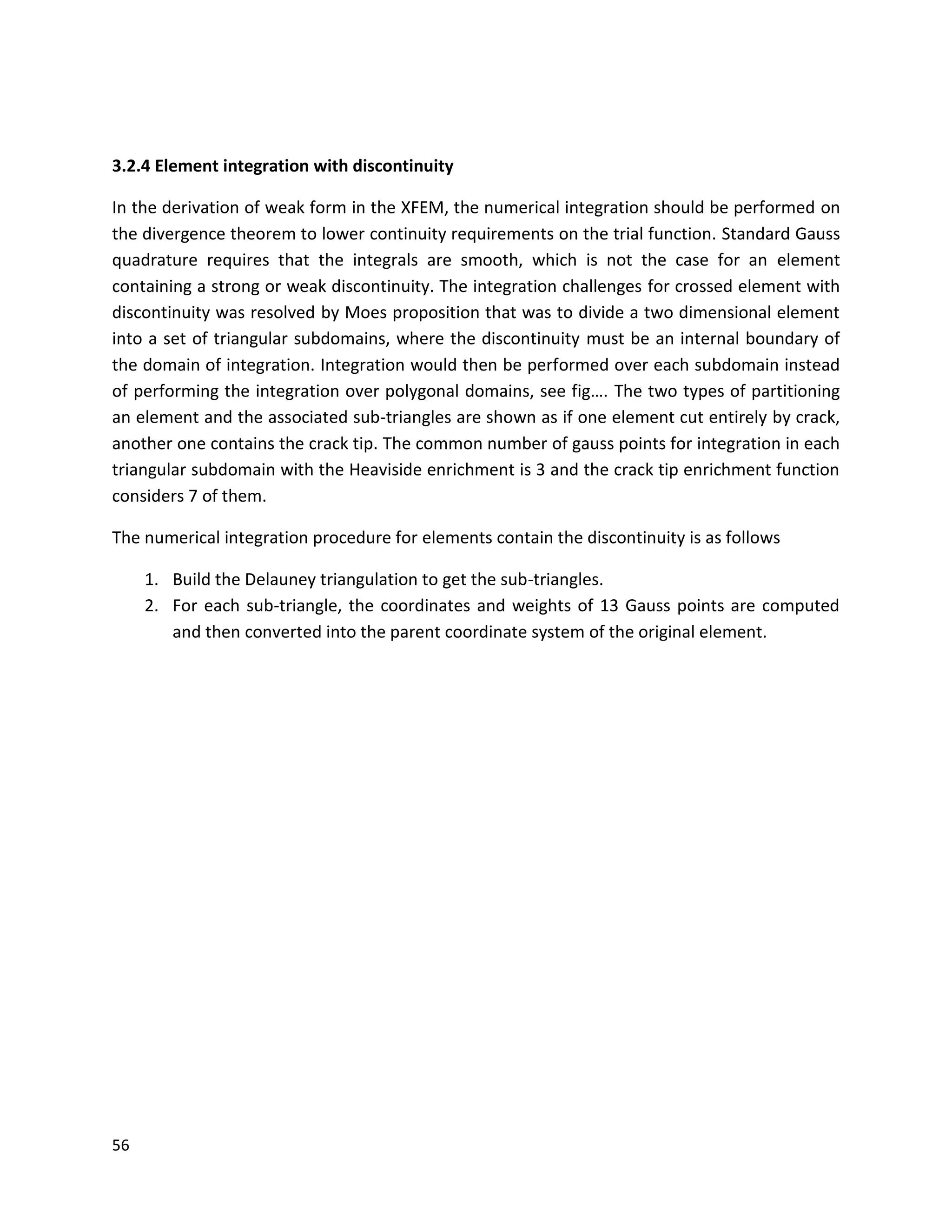

![57

Figure 69-Sub-triangulation of finite elements [6].

The MATLAB code was implemented for two-dimensional plane stress and plane strain

problems. The code is mainly developed for rectangular domain as structured grid of linear

square quadrilateral elements with arbitrary loading and boundary conditions. The enrichments

would be covered the homogenous crack, inclusion and void. All discontinuities are tracked

using level set method as well as calculation of enrichment functions. The 𝛷(𝑥) and 𝛹(𝑥) level

set functions track the crack, the χ(x) level set functions determine the boundary of void, and

the 𝜉(𝑥) level set function traces the inclusion. Integration of enriched elements is conducted

through the subdivision of elements into triangle regions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-57-2048.jpg)

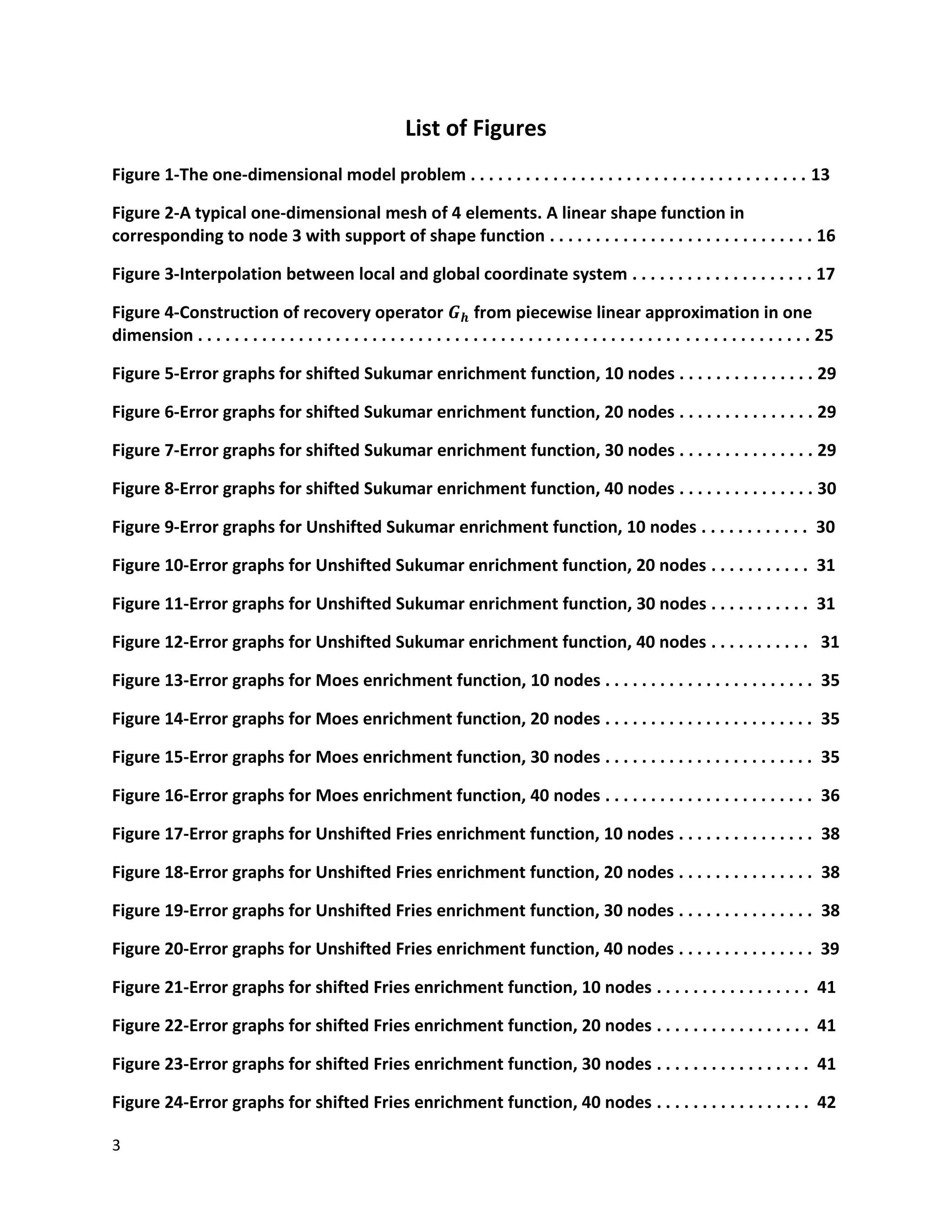

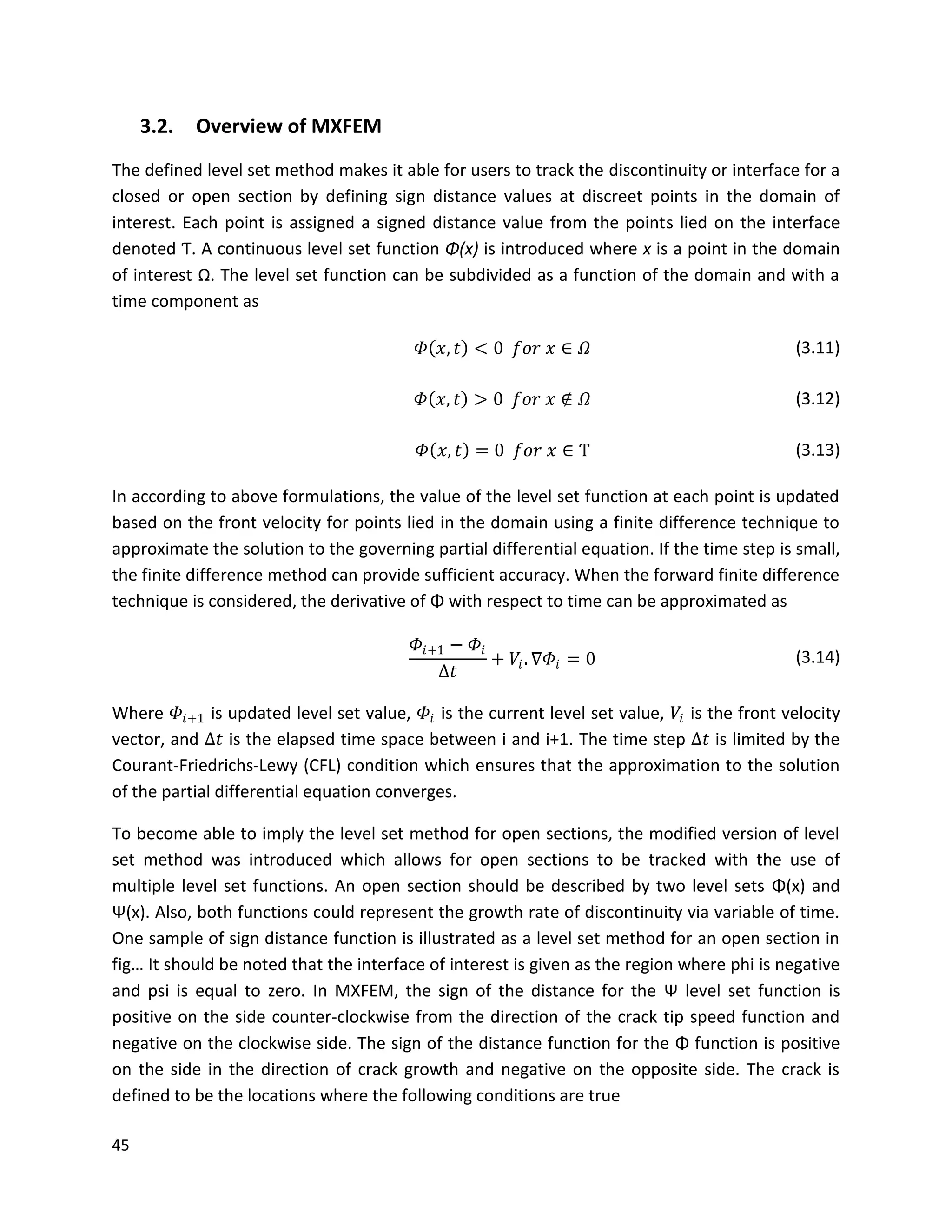

![59

where the discontinuities are evaluated at the midpoint of the sides. The gradient recovery-

based estimator might seem to be too complicated to be of practical use. However, the Kelly

estimator may be viewed as a modified recovery operator by taking the values of the recovered

gradient at the vertices likewise fig…

Figure 70-Construction of recovered gradient at vertex of element K. The value at • is a linear combination of the values at o

using the weights indicated [9].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/93377311-e16a-4bab-9909-0979dff6a332-160622121831/75/Master-Thesis-59-2048.jpg)