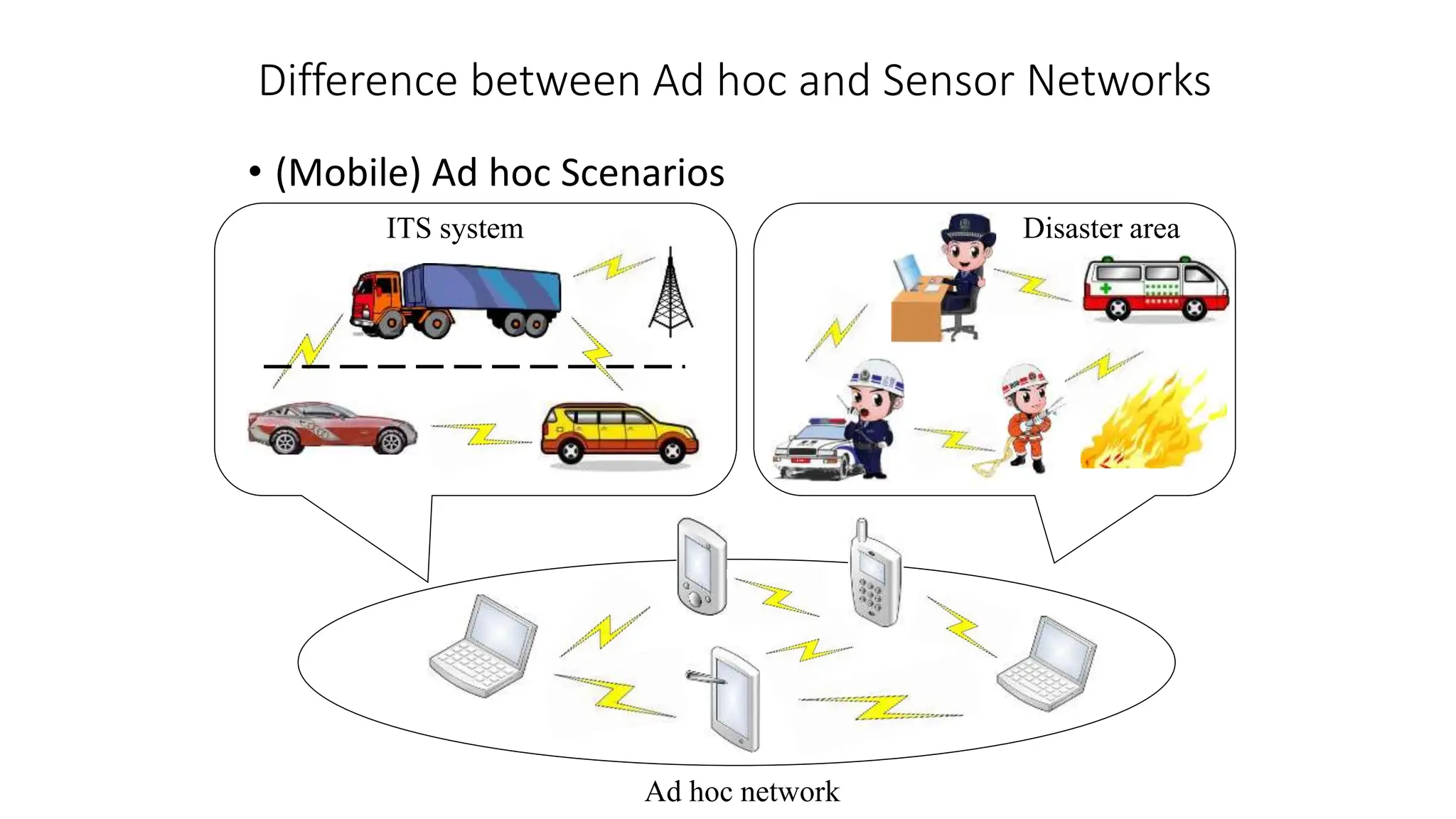

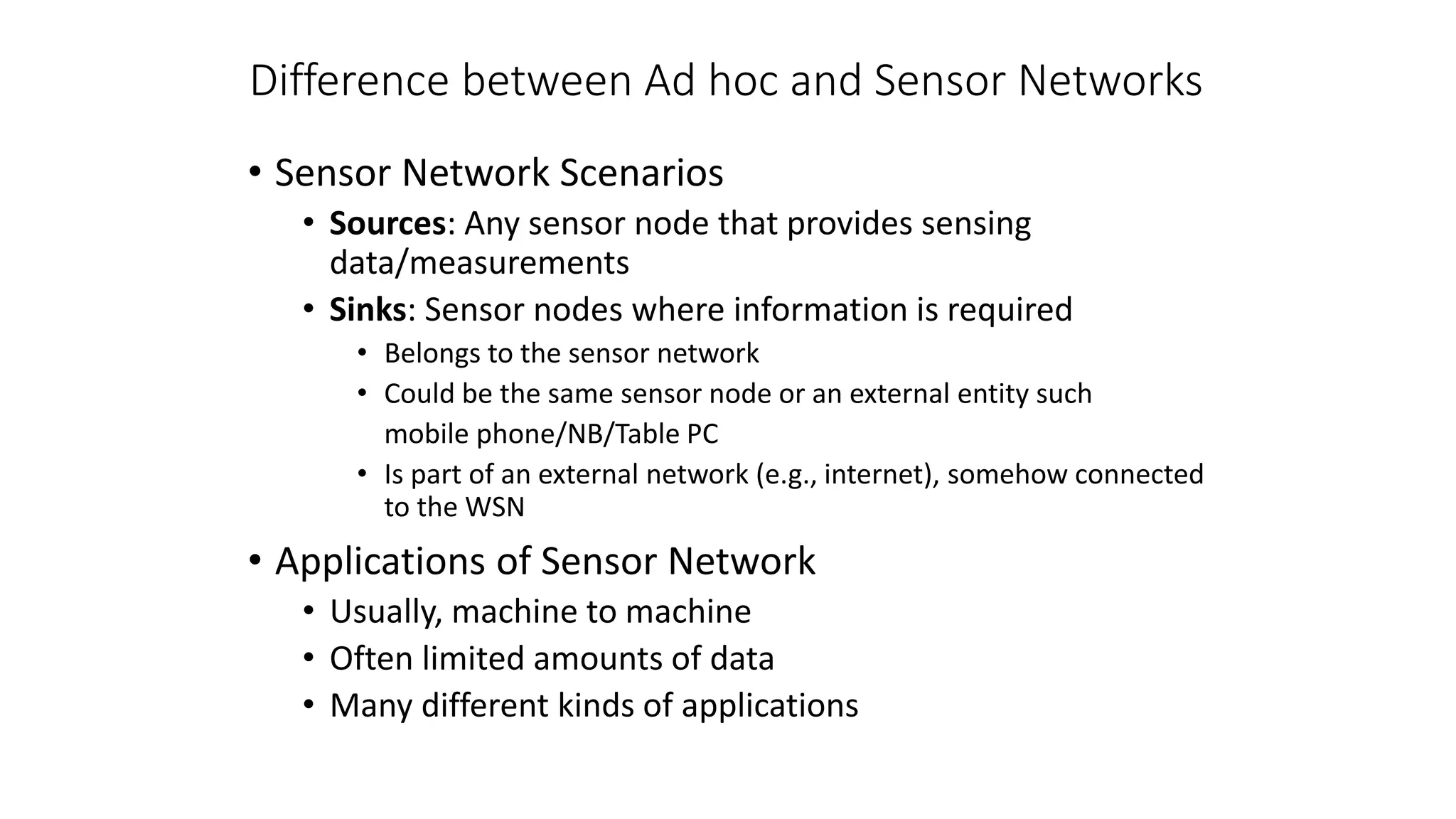

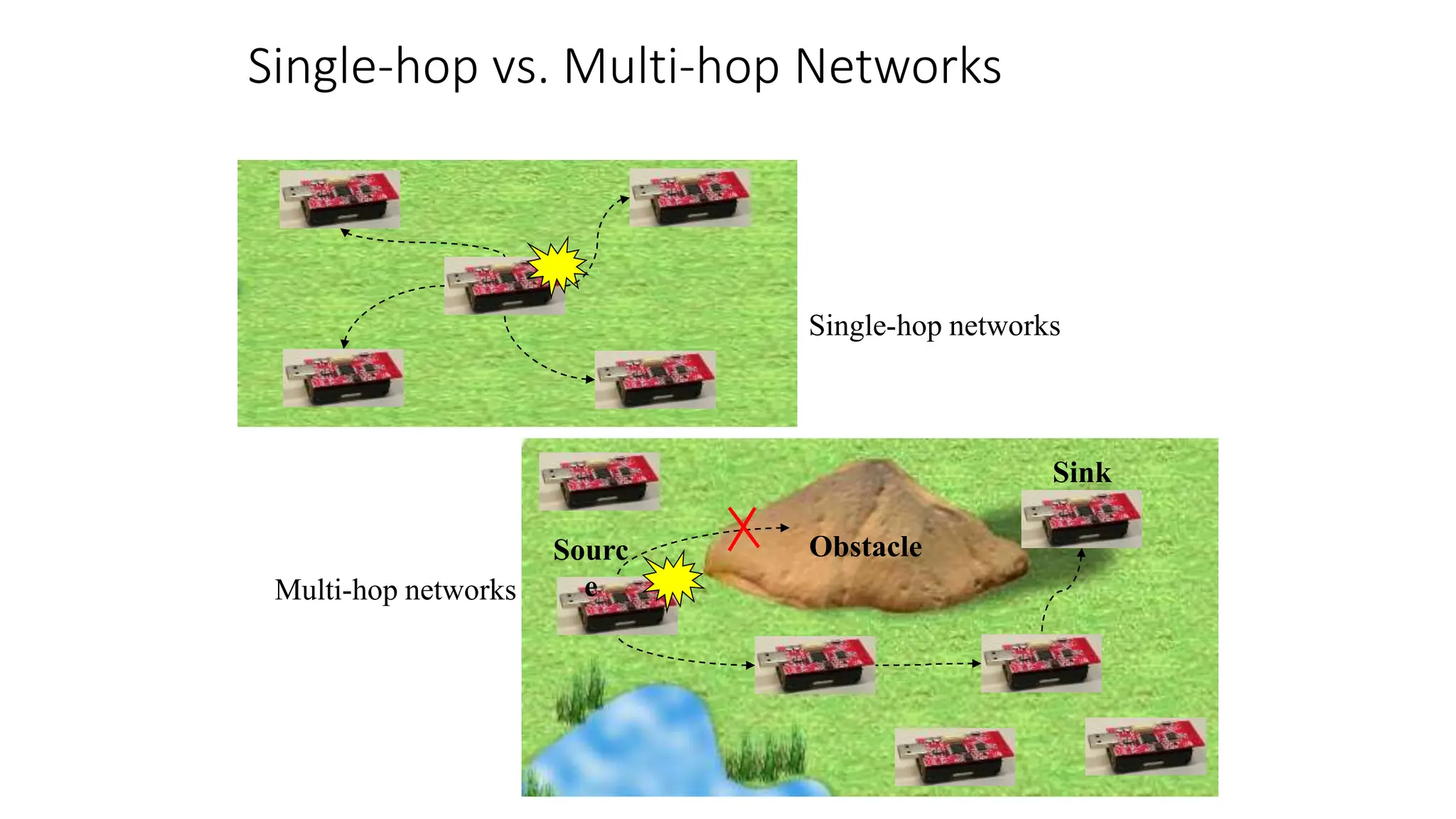

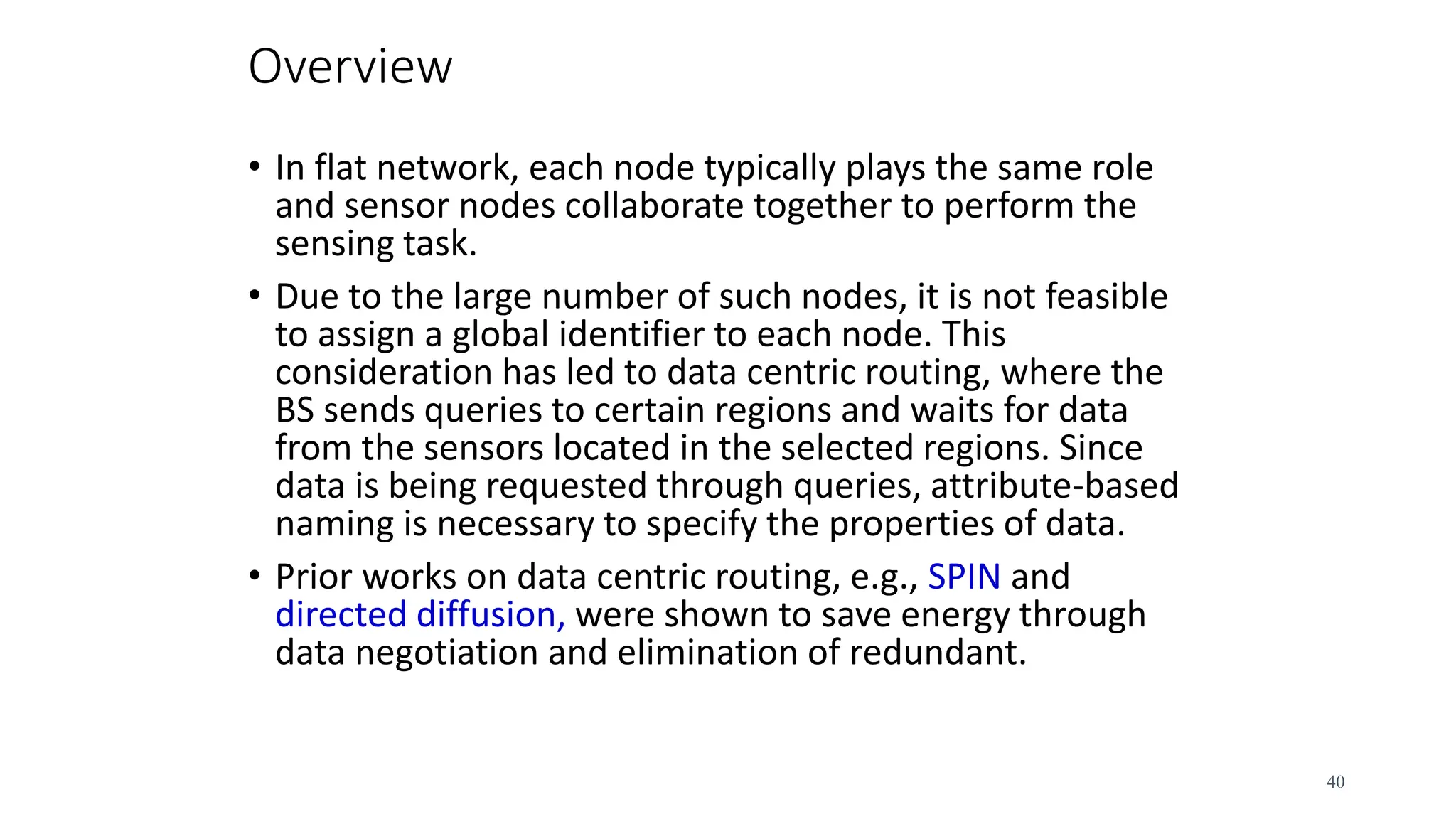

Network architecture documents the key differences between ad hoc and sensor networks. Ad hoc networks allow nodes to communicate directly with each other in a peer-to-peer fashion, while sensor networks have dedicated source nodes that sense data and sink nodes that receive the data. Sensor networks also employ in-network processing techniques like data aggregation to reduce energy costs of transmitting all raw data. Routing in wireless sensor networks faces challenges from limited node resources, topology changes, and energy constraints that require routing protocols to be scalable, fault-tolerant and energy-efficient.

![Single-hop vs. Multi-hop Networks

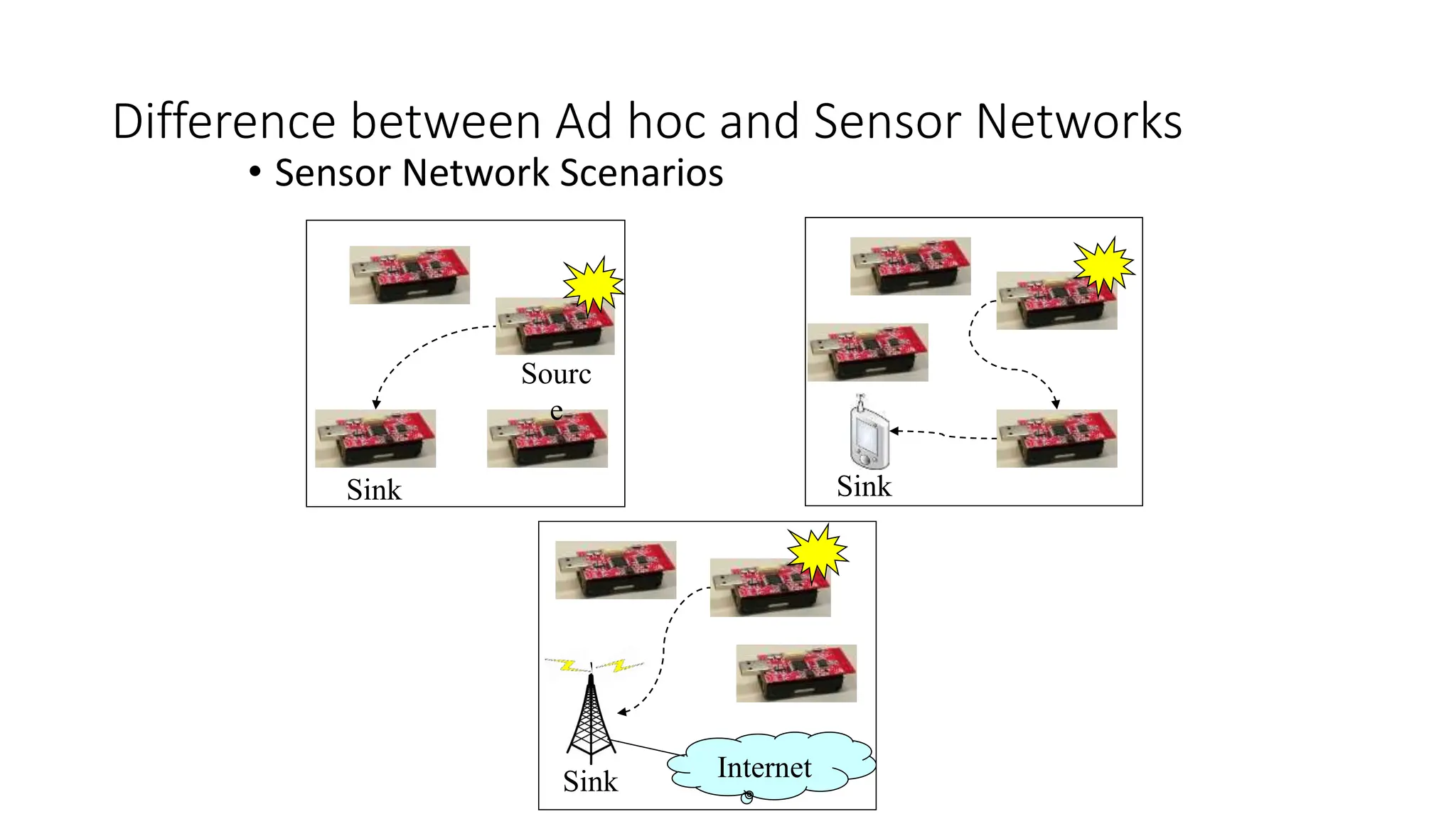

• One common problem: limited range of wireless

communication

• Limited transmission power

• Path loss

• Obstacles

• Solution: multi-hop networks

• Send packets to an intermediate node

• Intermediate node forwards packet to its destination

• Store-and-forward multi-hop network

• Basic technique applies to both WSN and MANET

• Note:

• Store-and-forward multi-hopping NOT the only possible

solution

• Ex: Collaborative networking, Network coding [11] [12].…](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kuliah02-240417014255-c7bd18a5/75/kuliah-02-network-architecture-for-student-pptx-6-2048.jpg)

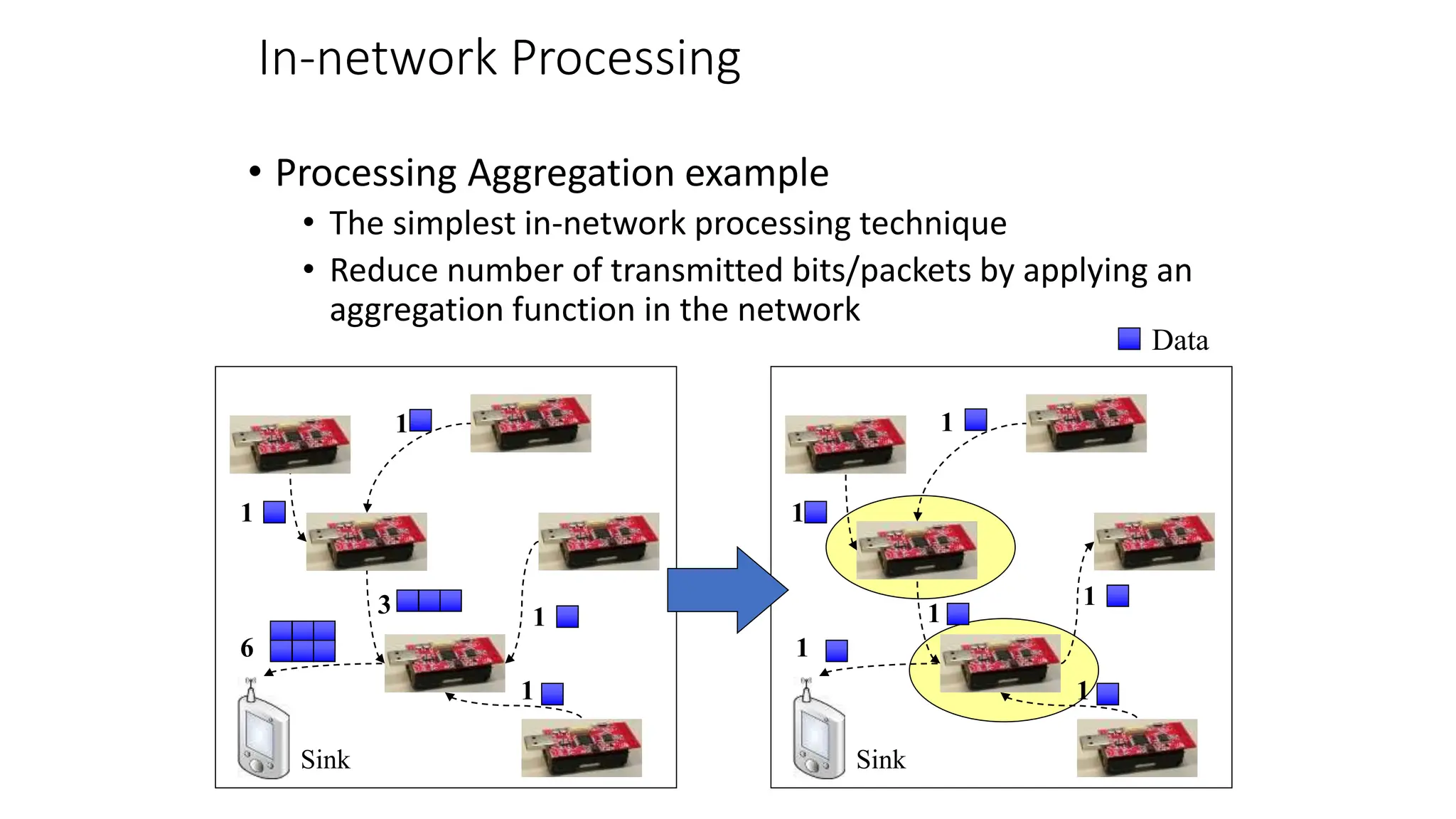

![In-network Processing

• MANETs are supposed to deliver bits from one end to

the other

• WSNs, on the other end, are expected to provide

information, not necessarily original bits

• Ex: manipulate or process the data in the network

• Main example: aggregation

• Apply composable [13] aggregation functions to a

convergecast tree in a network

• Typical functions: minimum, maximum, average, sum, …](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kuliah02-240417014255-c7bd18a5/75/kuliah-02-network-architecture-for-student-pptx-9-2048.jpg)

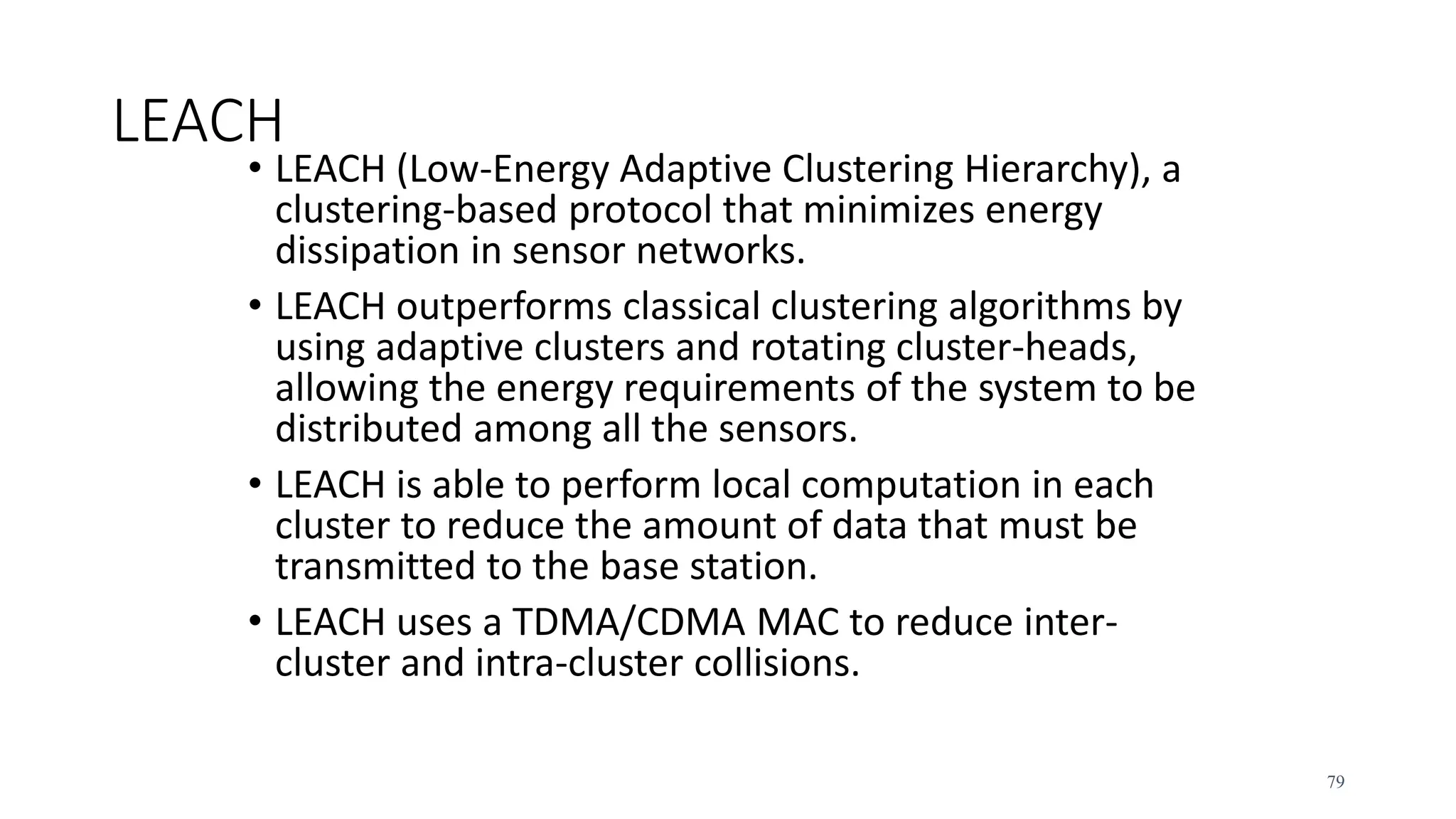

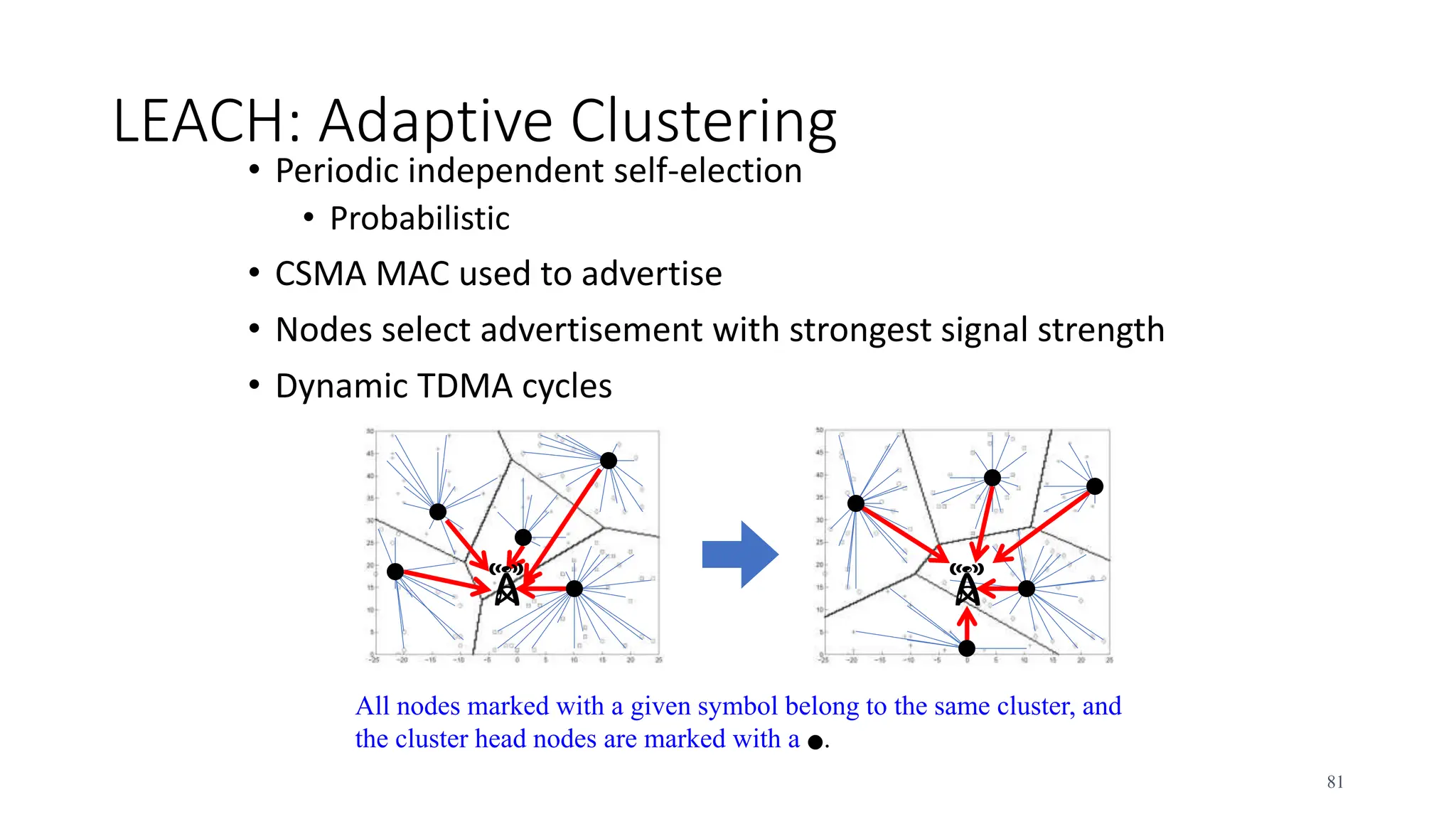

![Algorithm (cont.)

• Set-up phase

• Node n choosing a random number m between 0 and 1

• If m < T(n) for node n, the node becomes a cluster-head where

• where P = the desired percentage of cluster heads (e.g., P= 0.05),

r=the current round, and G is the set of nodes that have not

been cluster-heads in the last 1/P rounds. Using this threshold,

each node will be a cluster-head at some point within 1/P

rounds. During round 0 (r=0), each node has a probability P of

becoming a cluster-head.

1 [ * mod(1/ )]

( )

0 ,

P

if n G

P r P

T n

otherwise

84](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kuliah02-240417014255-c7bd18a5/75/kuliah-02-network-architecture-for-student-pptx-84-2048.jpg)