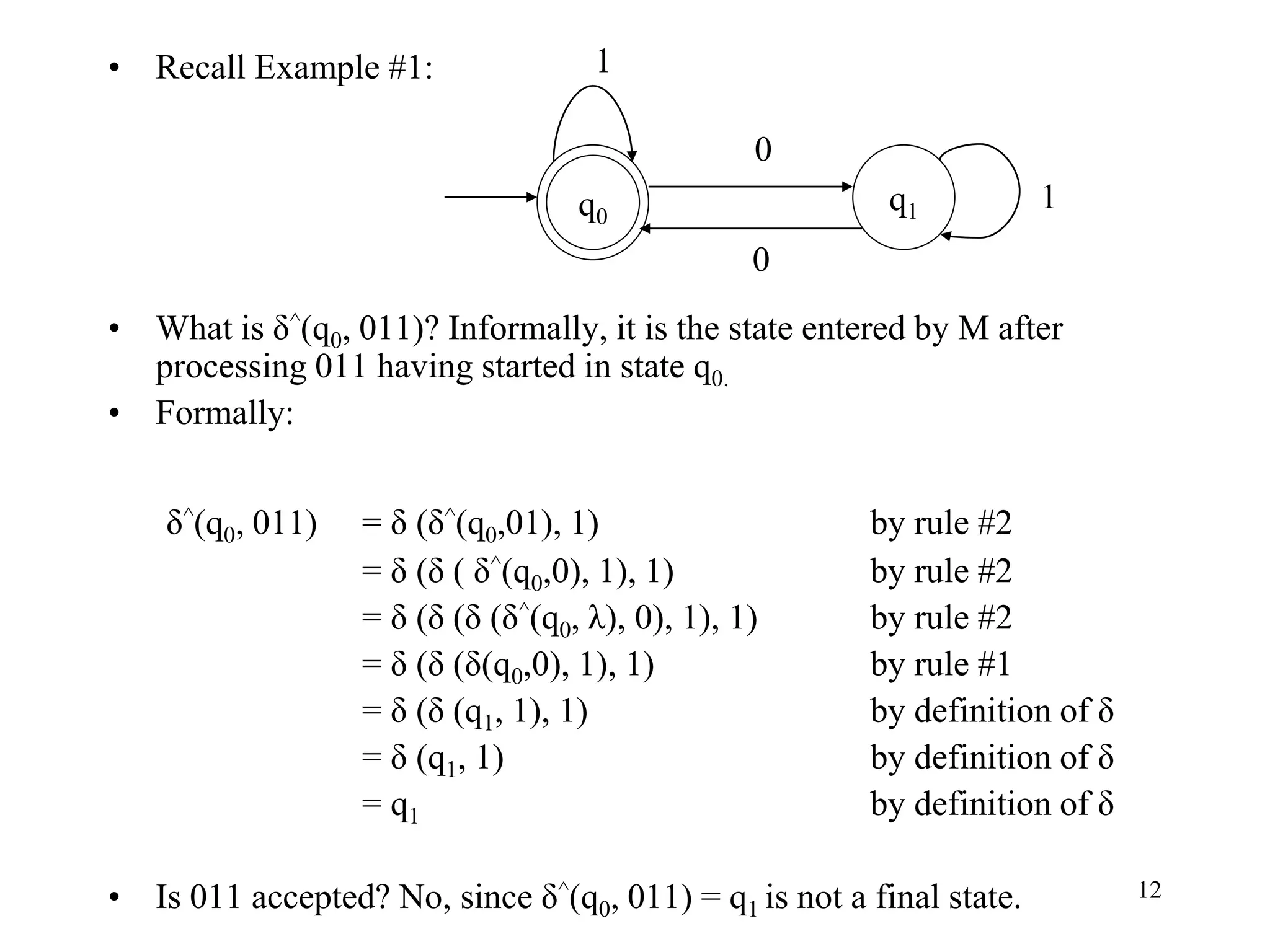

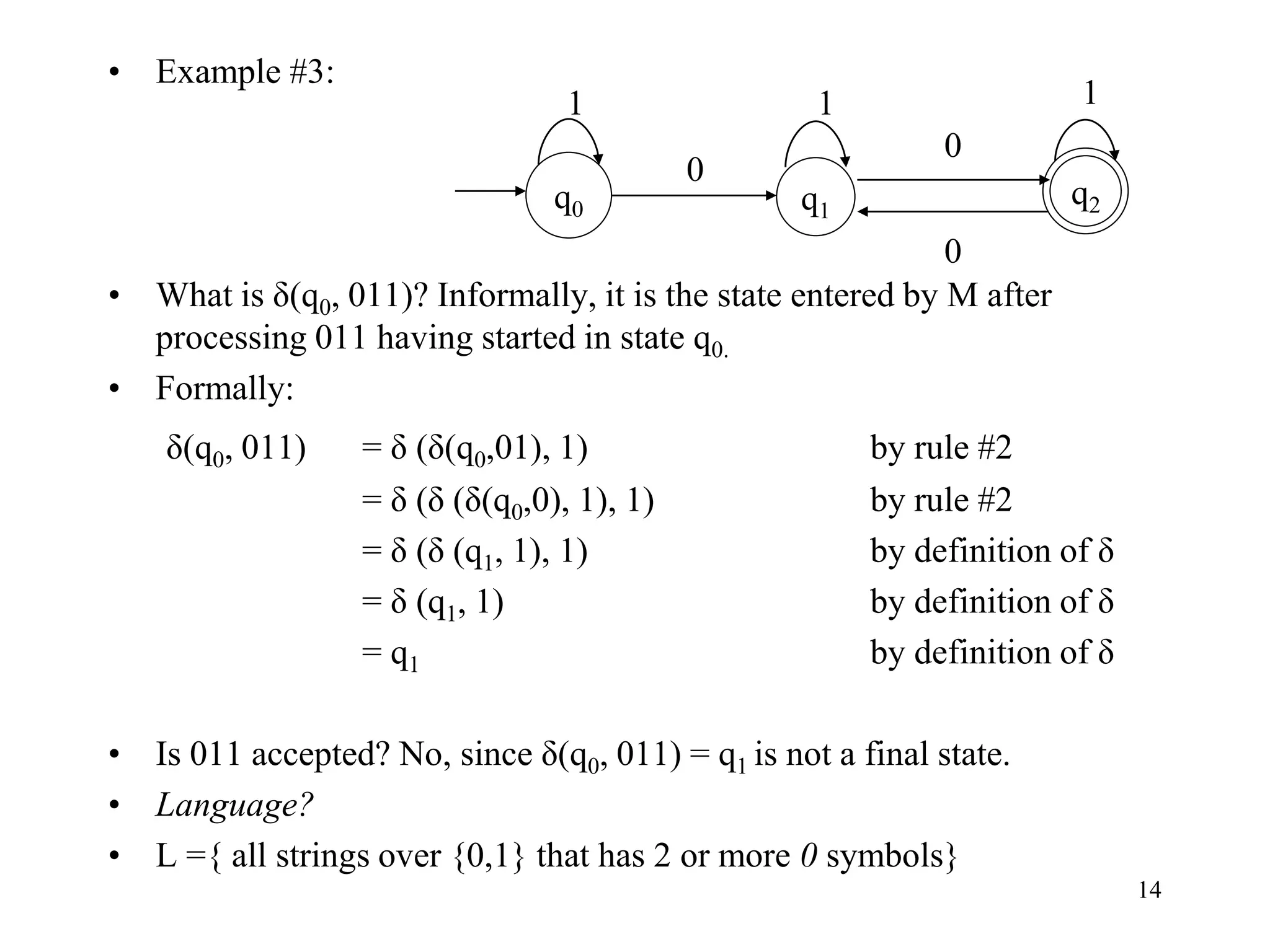

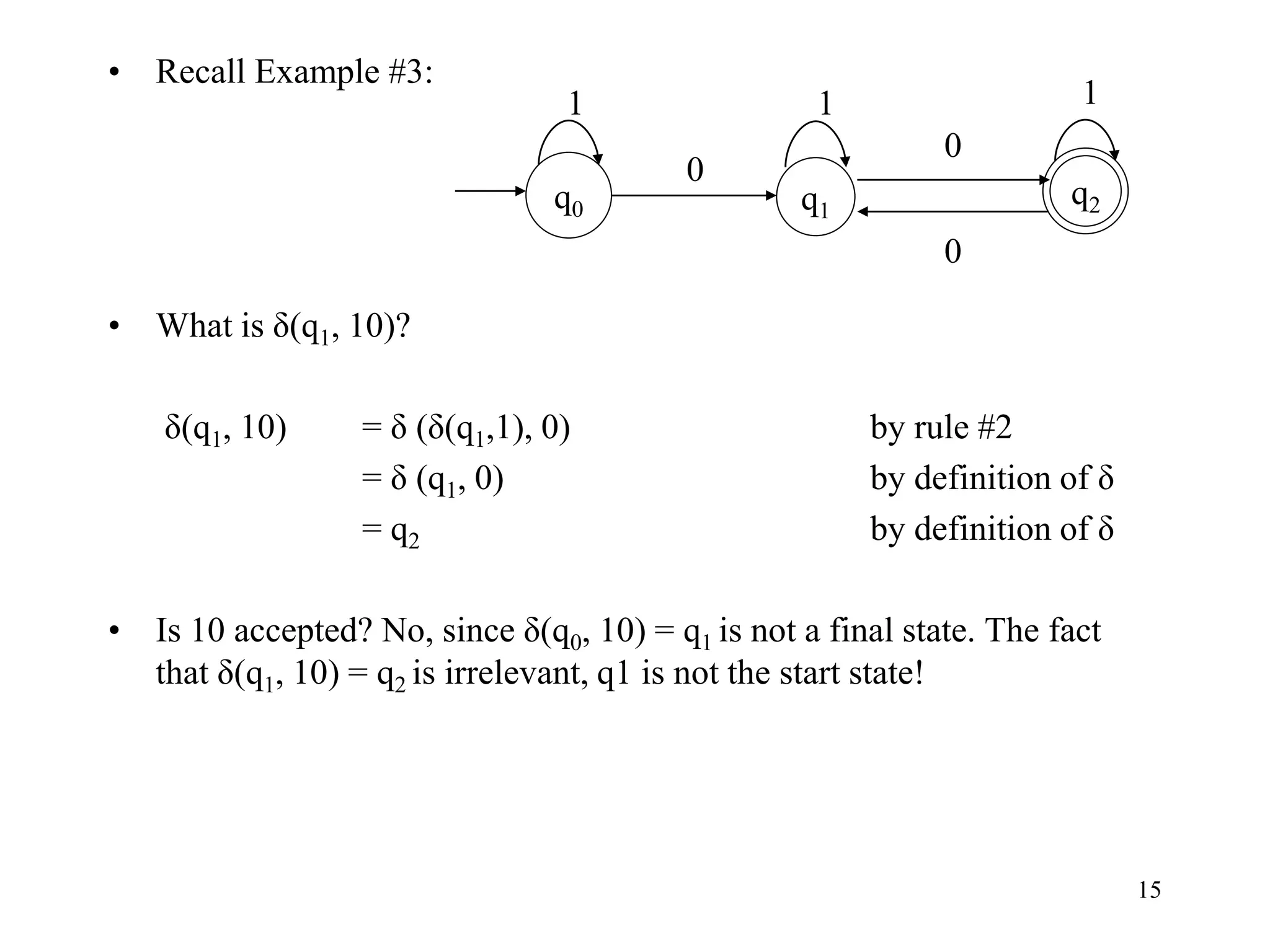

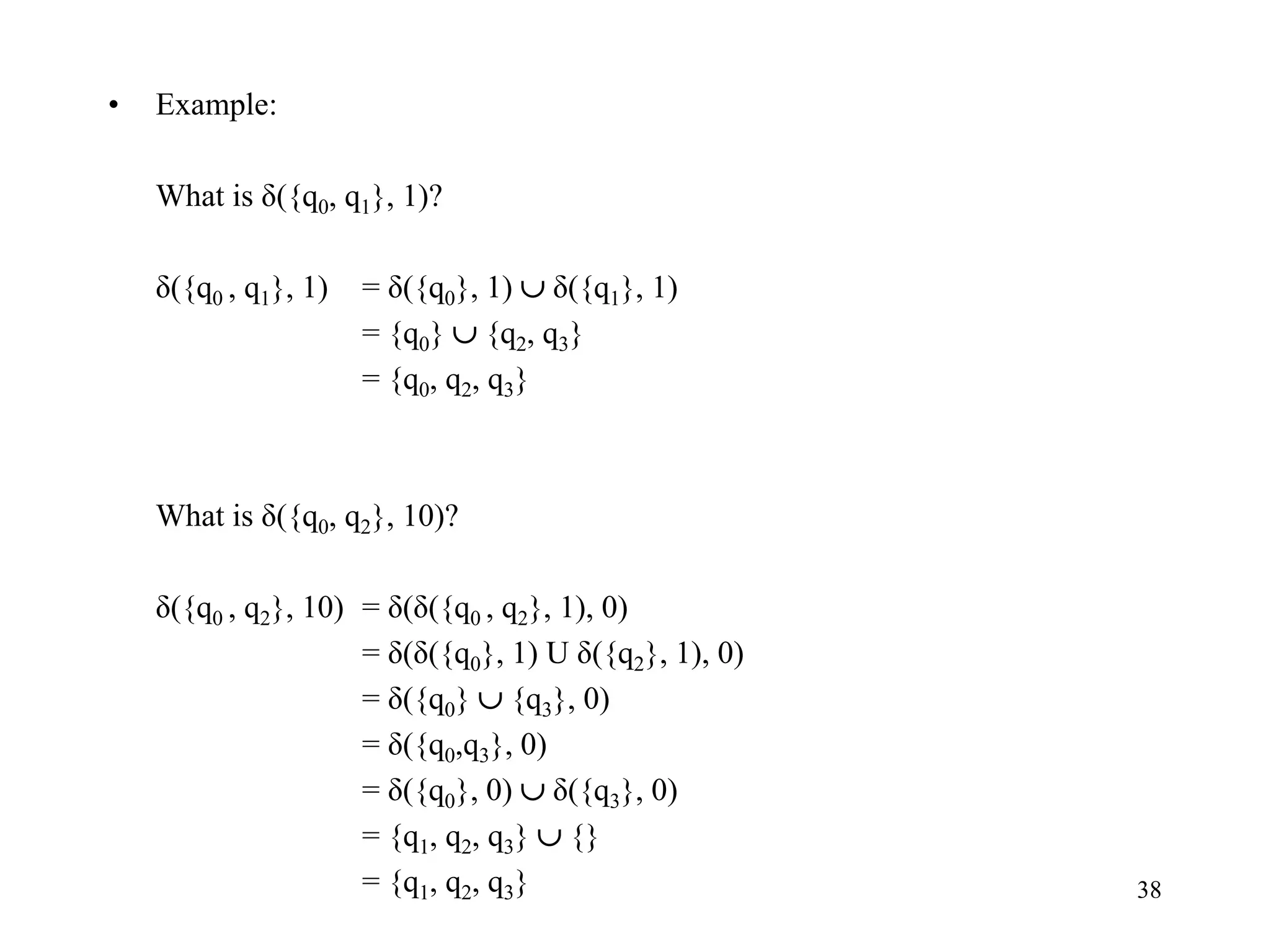

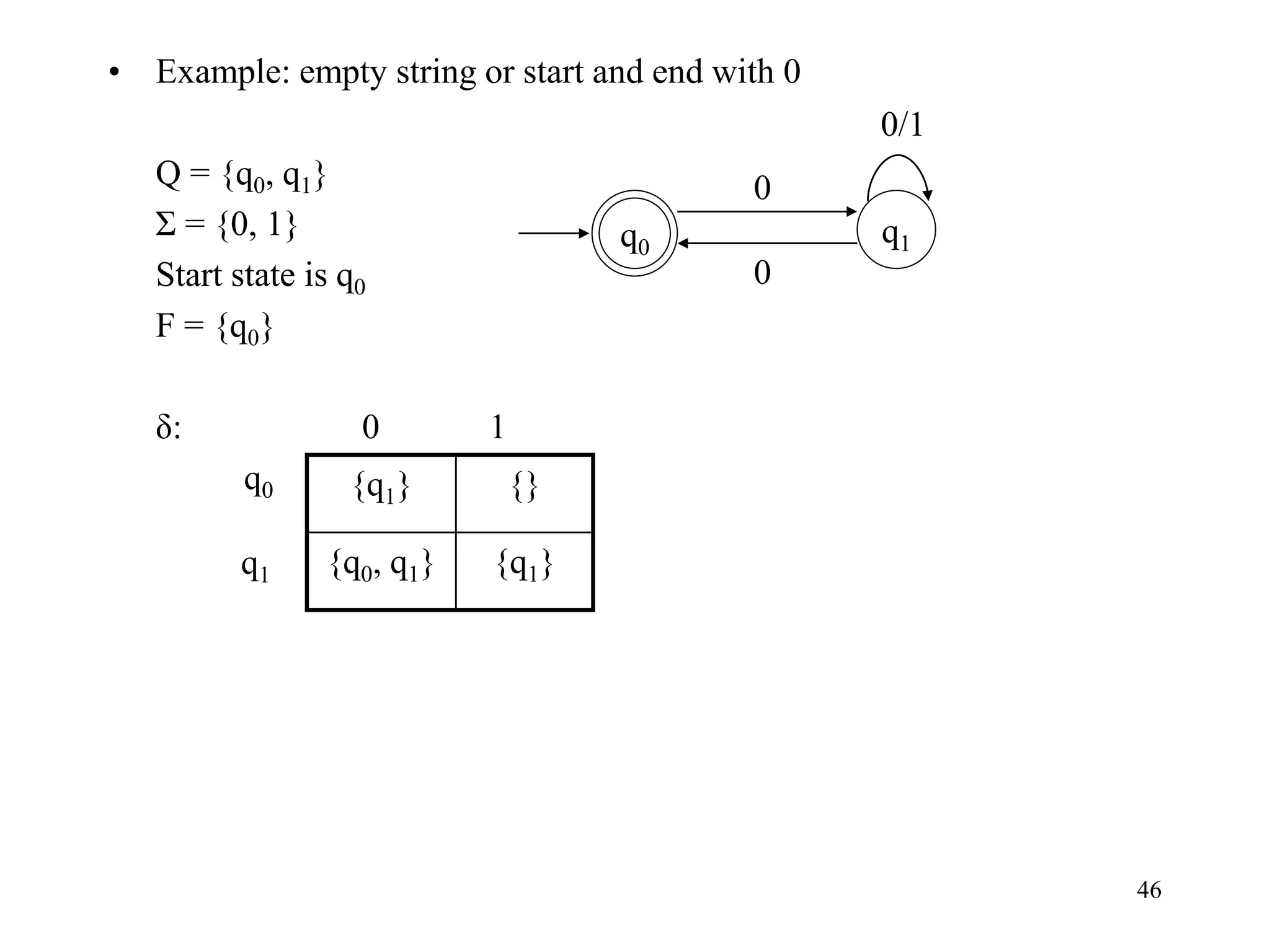

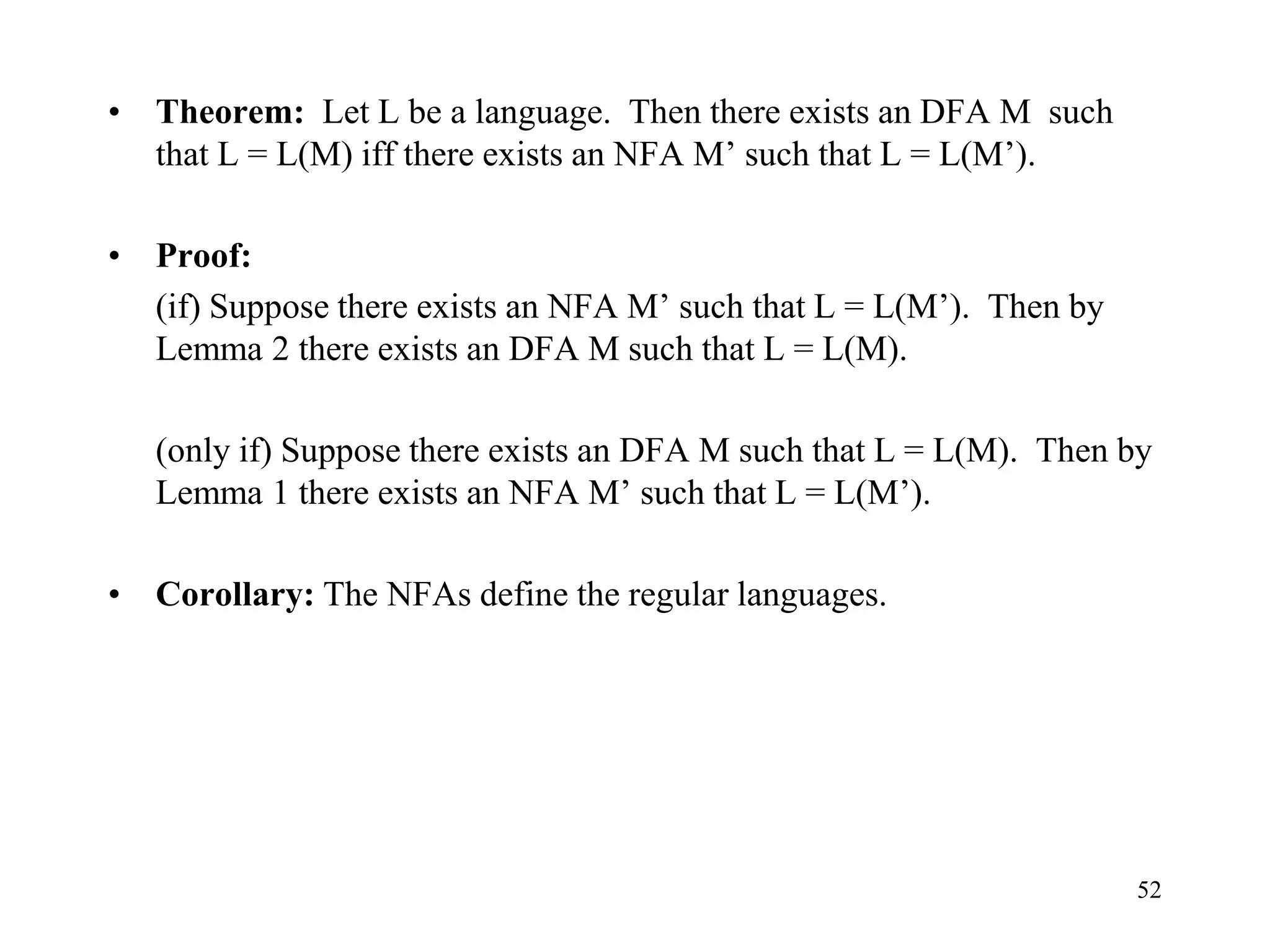

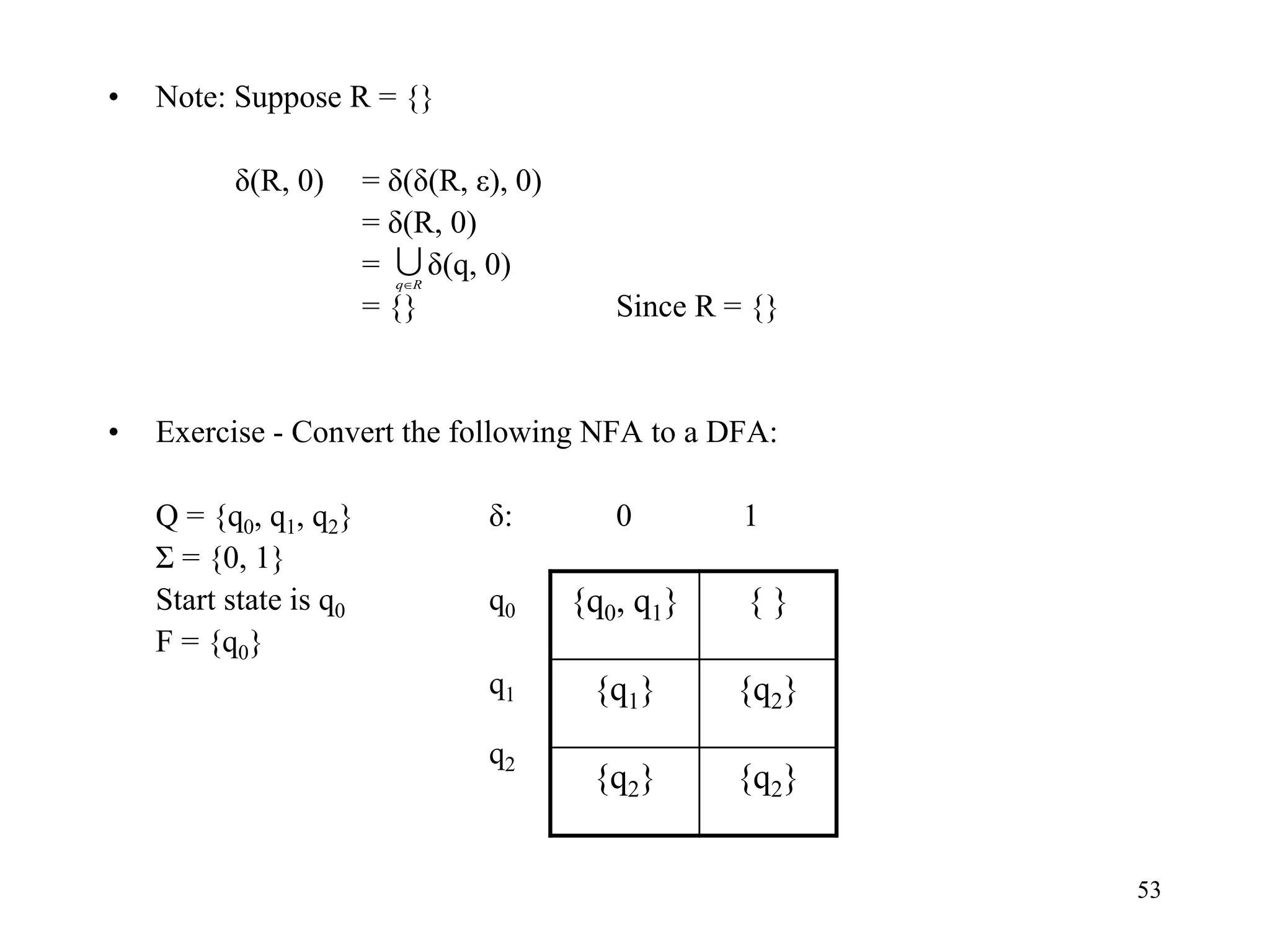

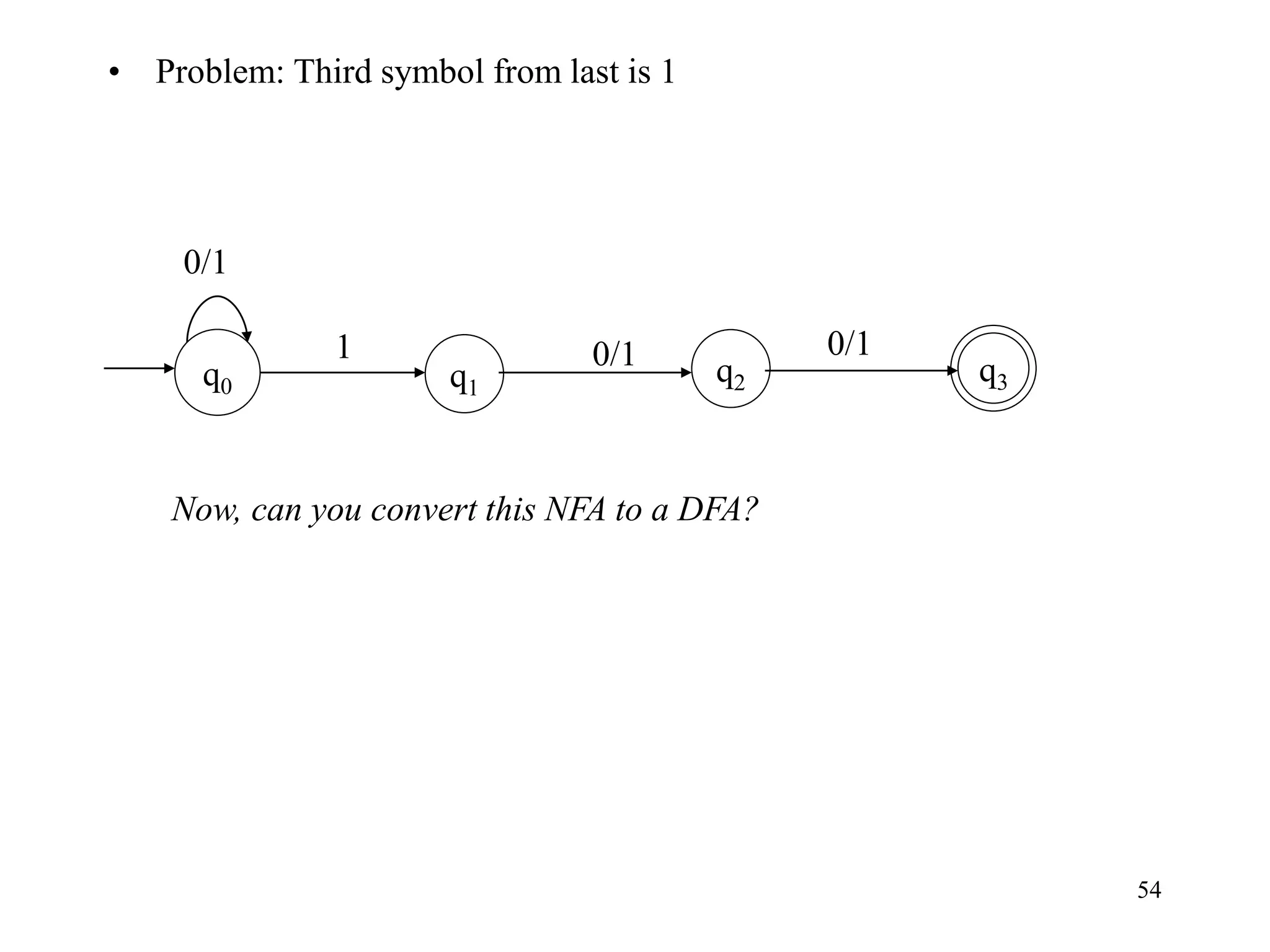

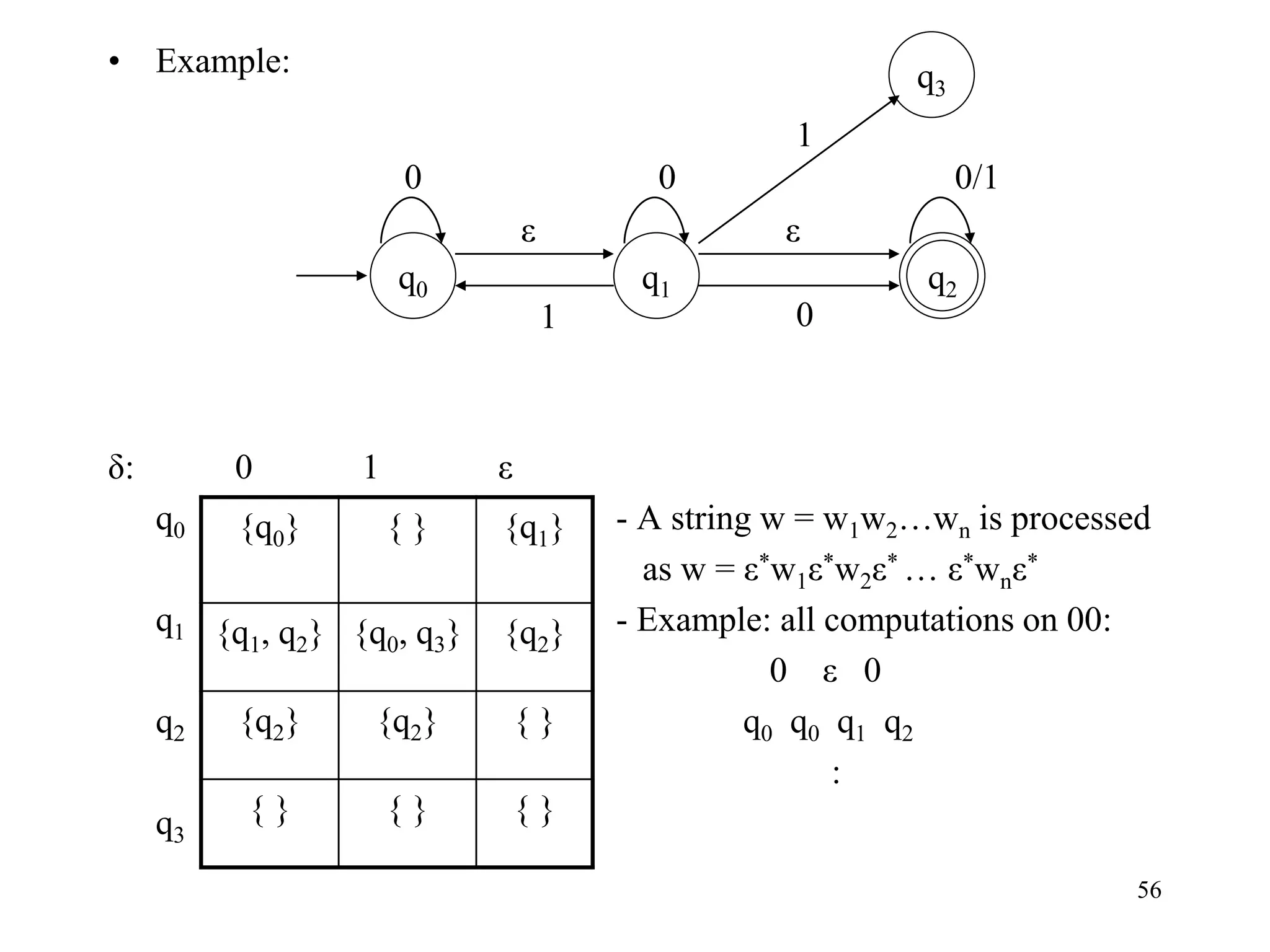

This document discusses deterministic finite automata (DFAs) and nondeterministic finite automata (NFAs). It provides examples of DFAs that accept certain languages over various alphabets. It also defines NFAs formally and provides examples of NFAs that accept languages. The key differences between DFAs and NFAs are that NFA transition functions can map a state-symbol pair to multiple possible next states, whereas DFA transition functions map to exactly one next state.

![45

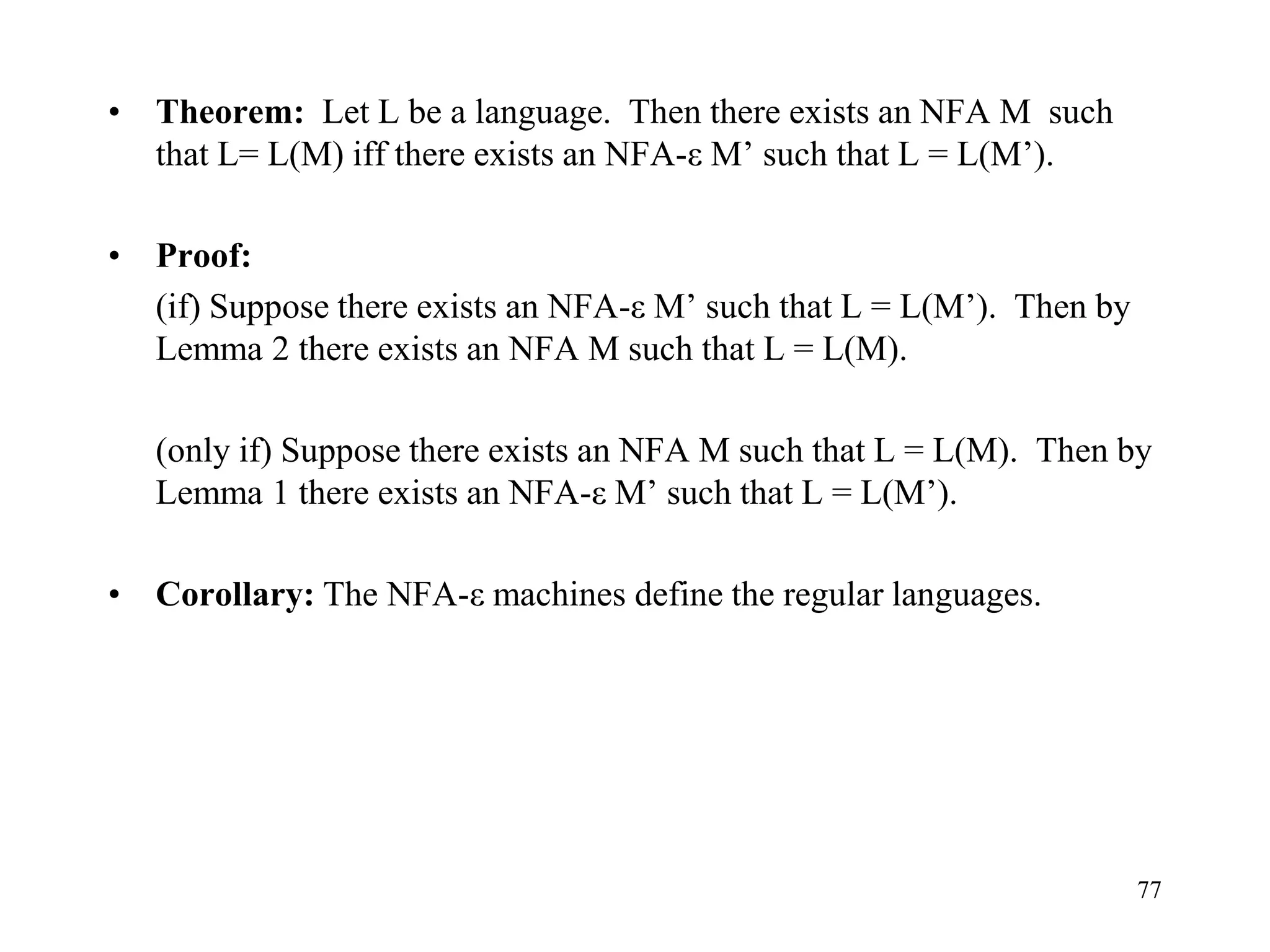

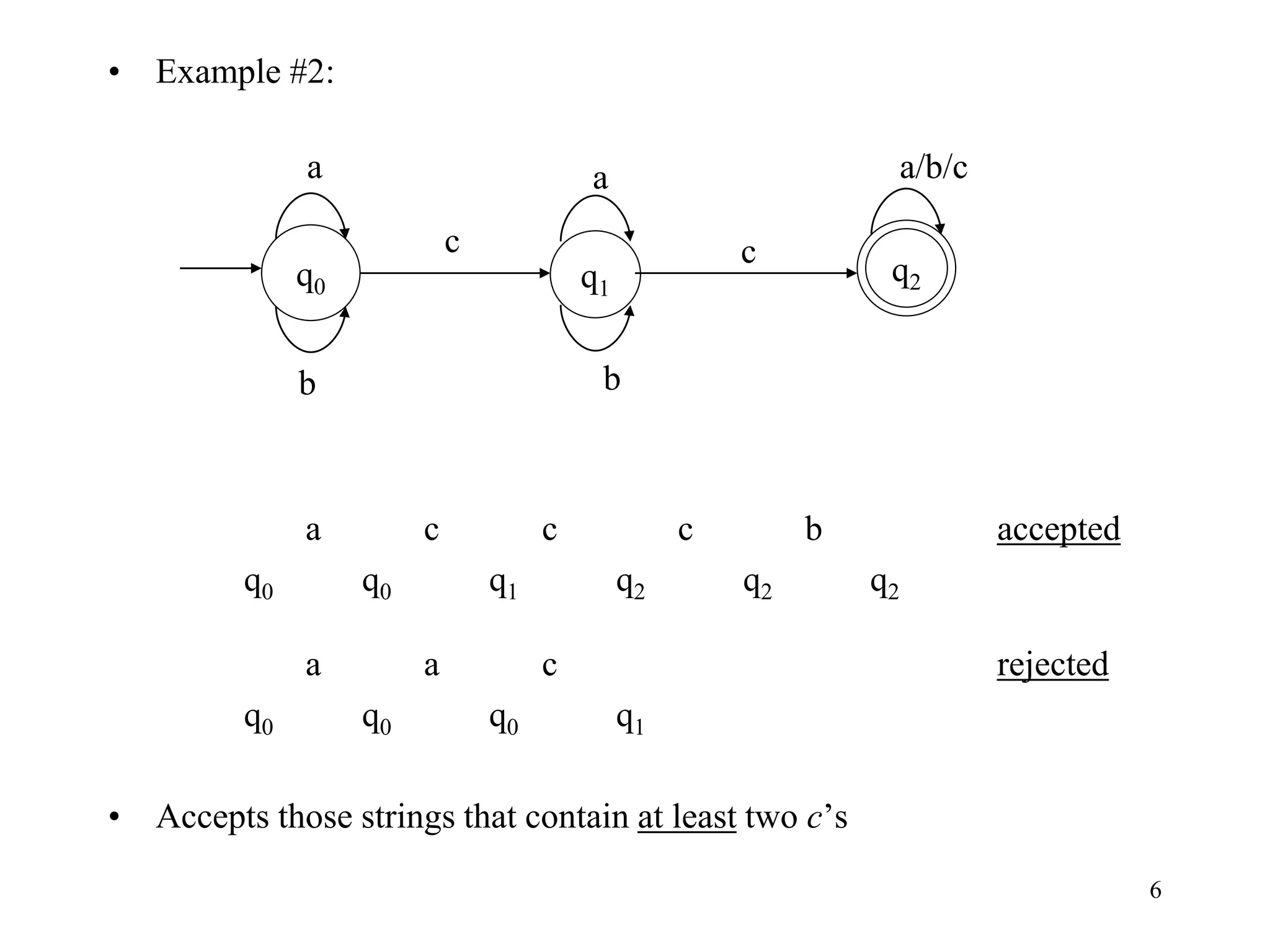

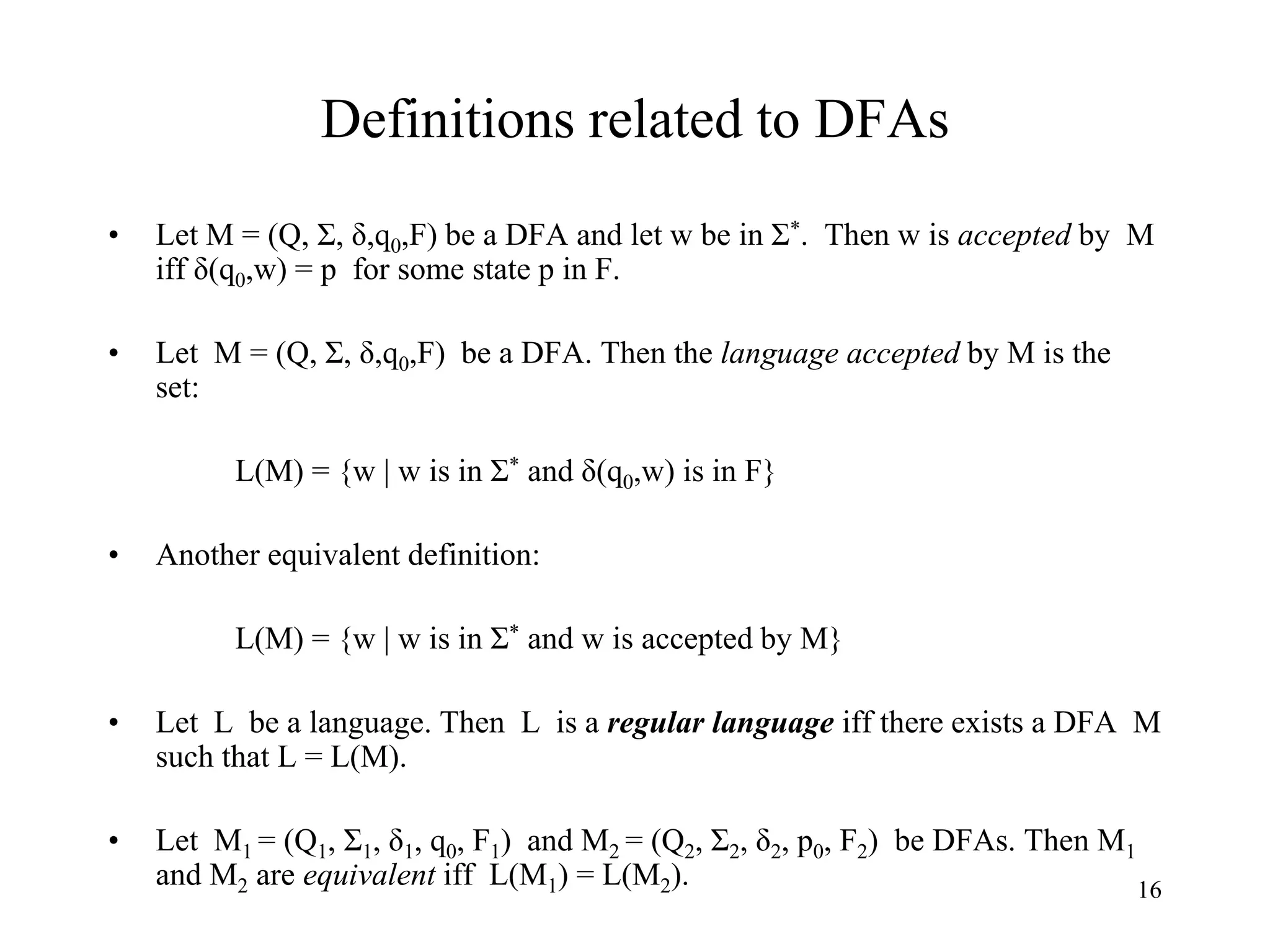

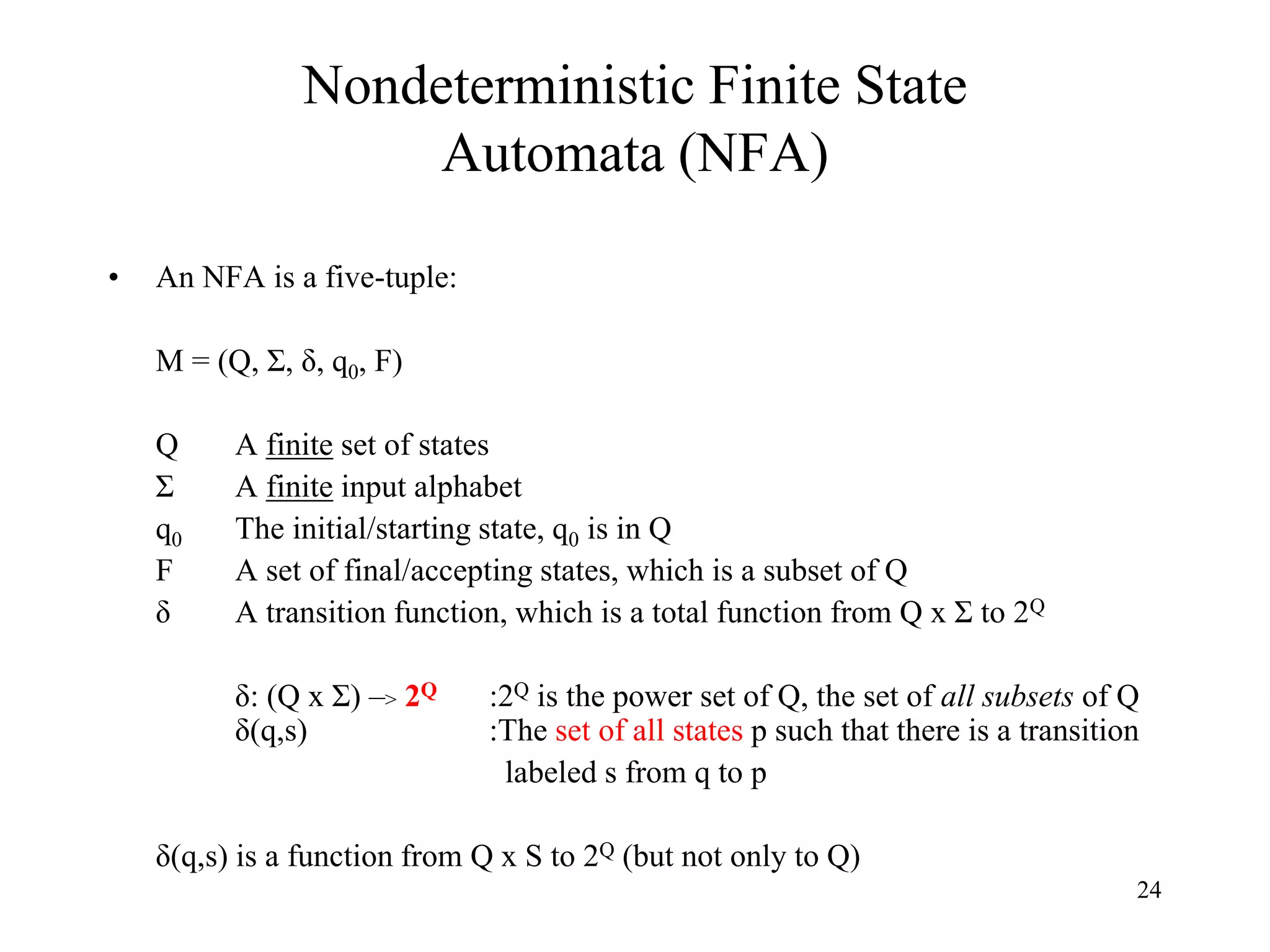

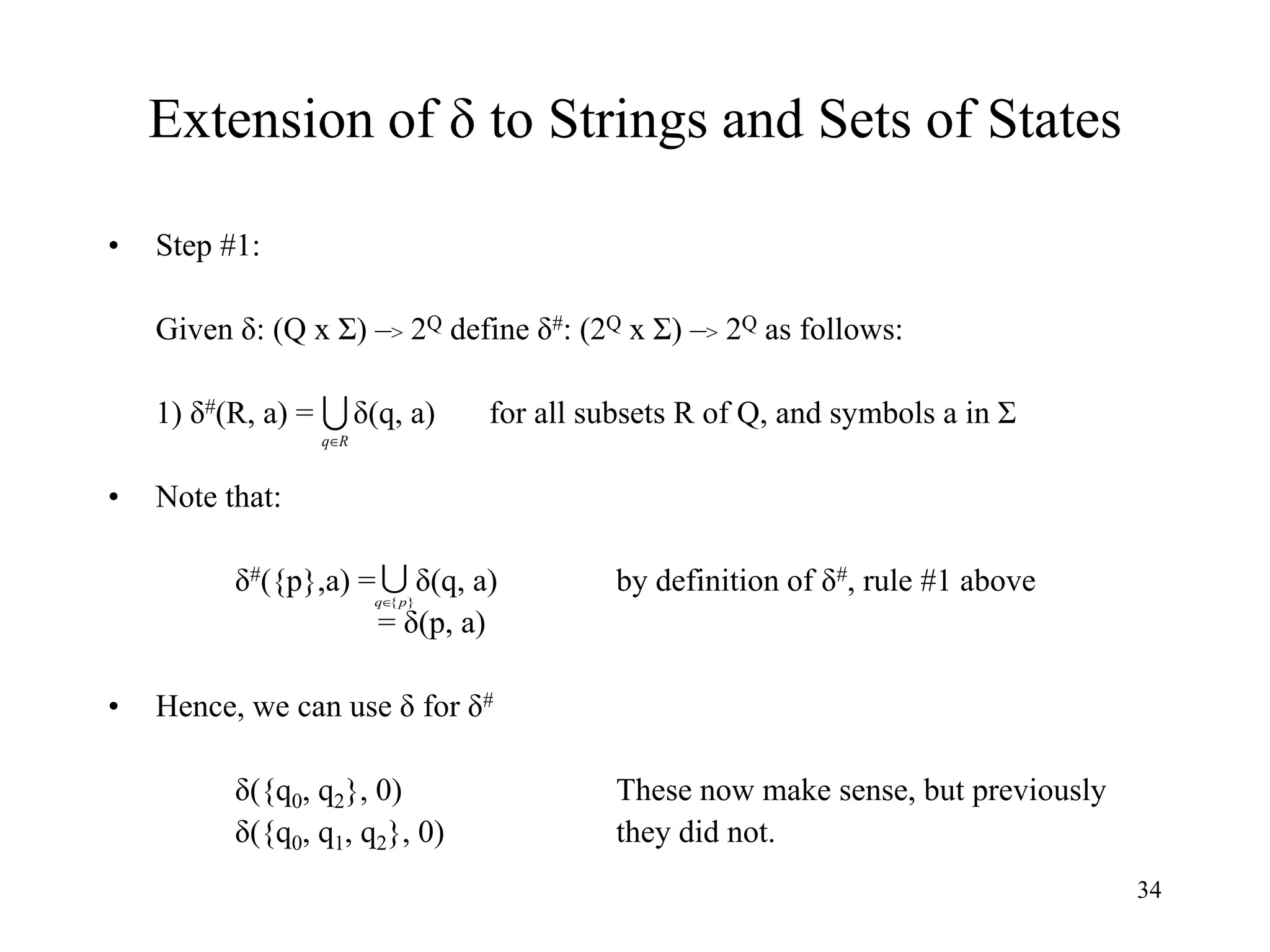

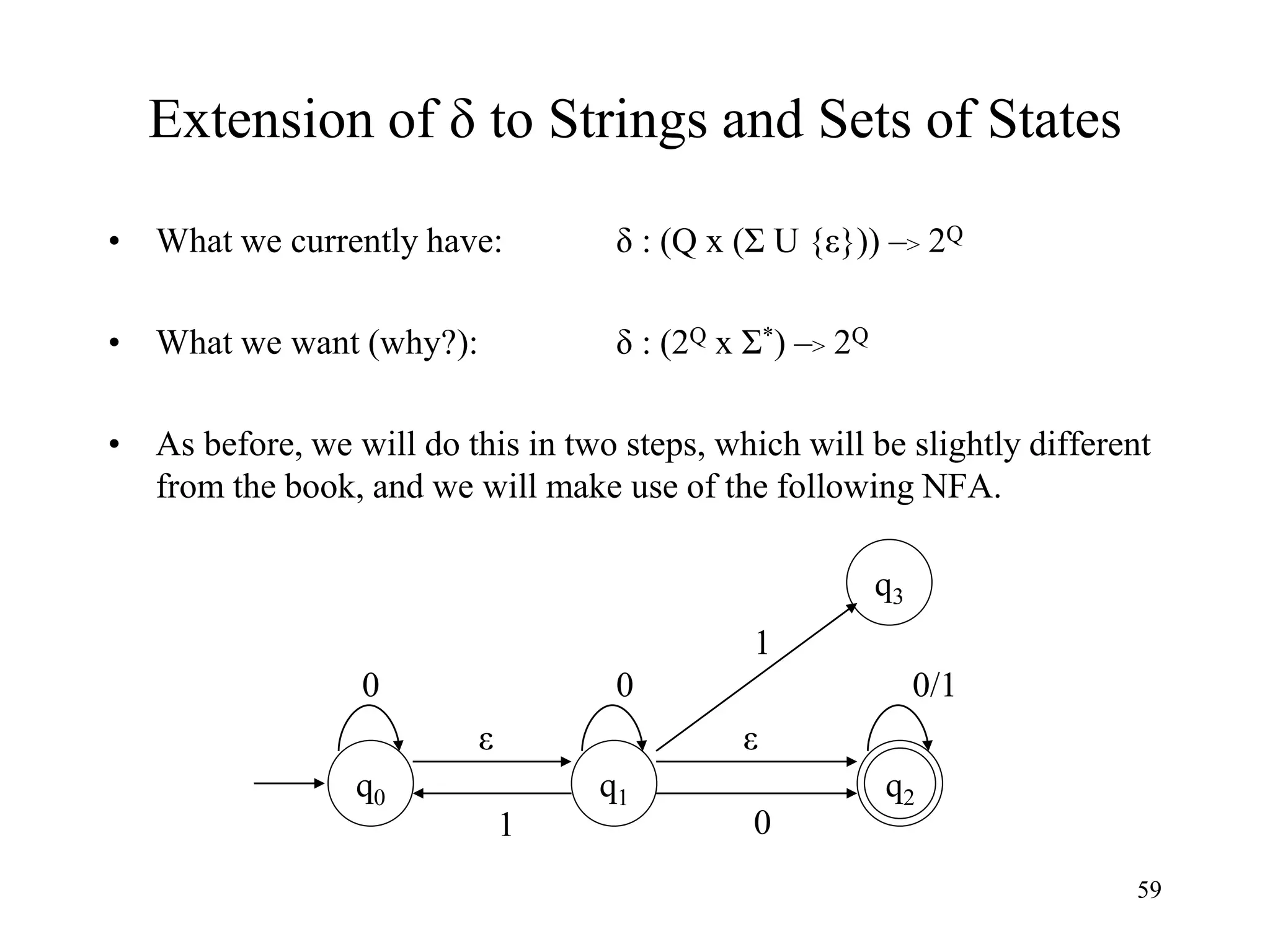

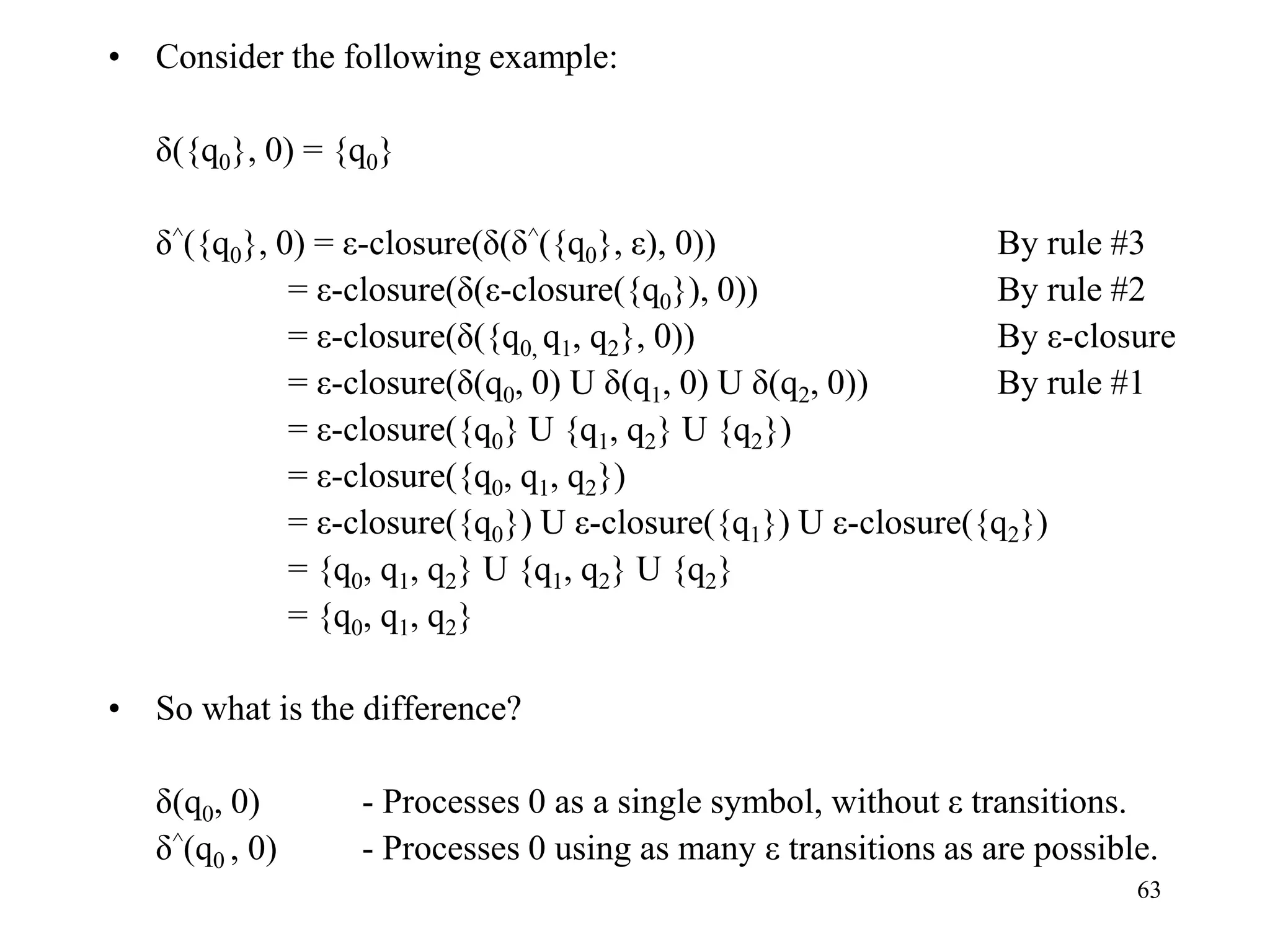

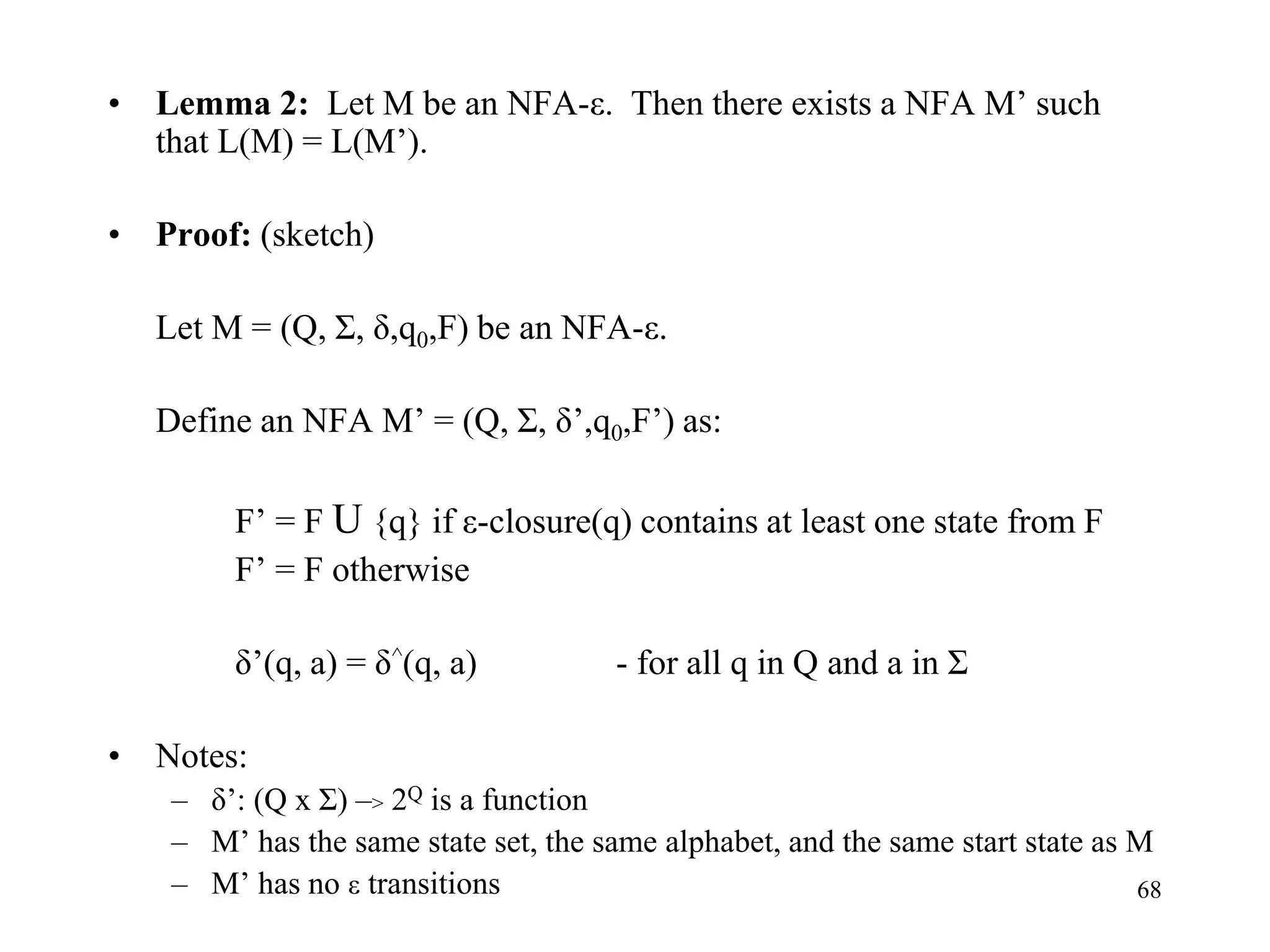

• Lemma 2: Let M be an NFA. Then there exists a DFA M’ such that L(M) =

L(M’).

• Proof: (sketch)

Let M = (Q, Σ, δ,q0,F).

Define a DFA M’ = (Q’, Σ, δ’,q’

0,F’) as:

Q’ = 2Q Each state in M’ corresponds to a

= {Q0, Q1,…,} subset of states from M

where Qu = [qi0, qi1,…qij]

F’ = {Qu | Qu contains at least one state in F}

q’

0 = [q0]

δ’(Qu, a) = Qv iff δ(Qu, a) = Qv](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finiteautomata1-230920000545-37281e08/75/FiniteAutomata-1-ppt-45-2048.jpg)

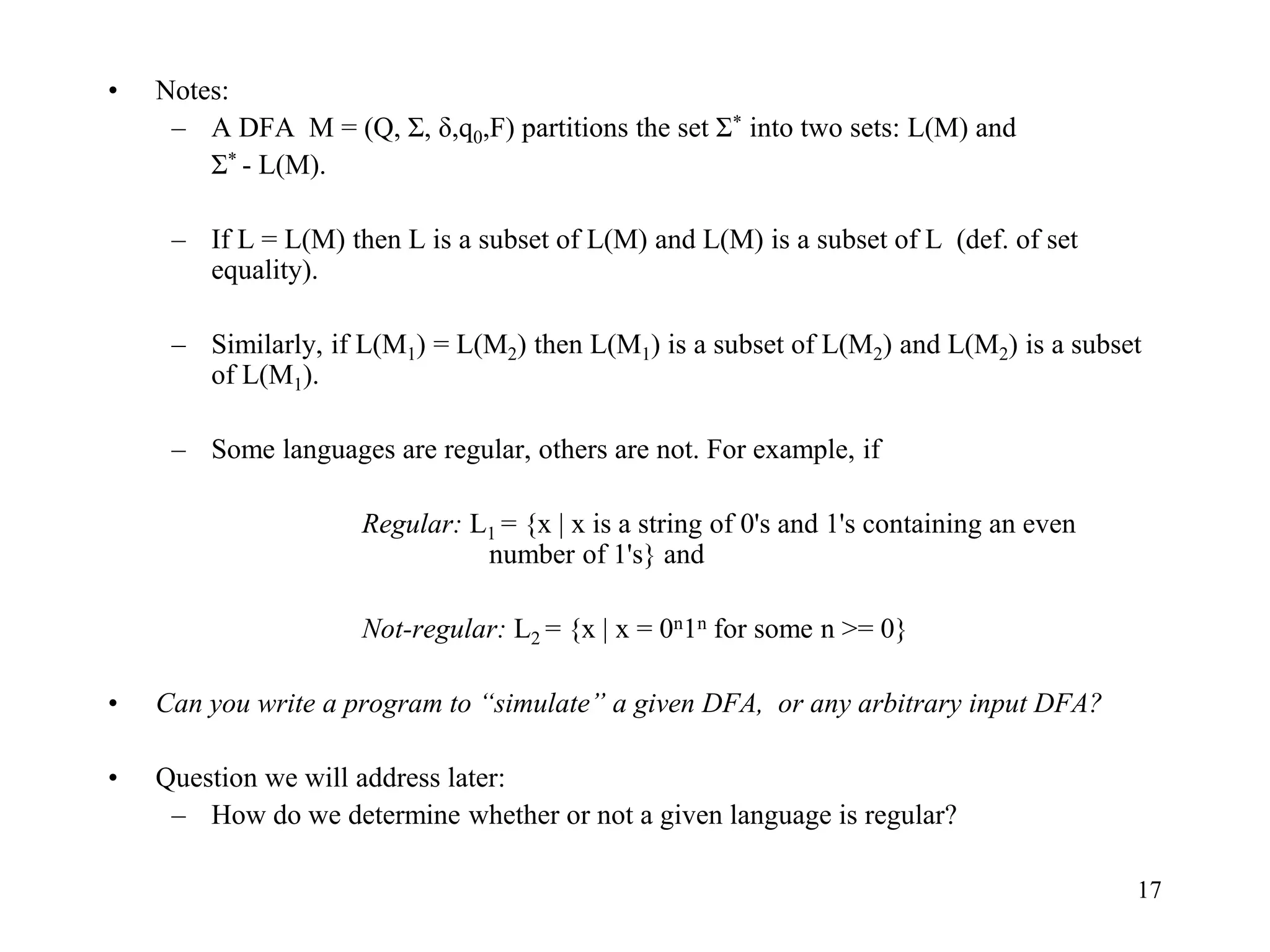

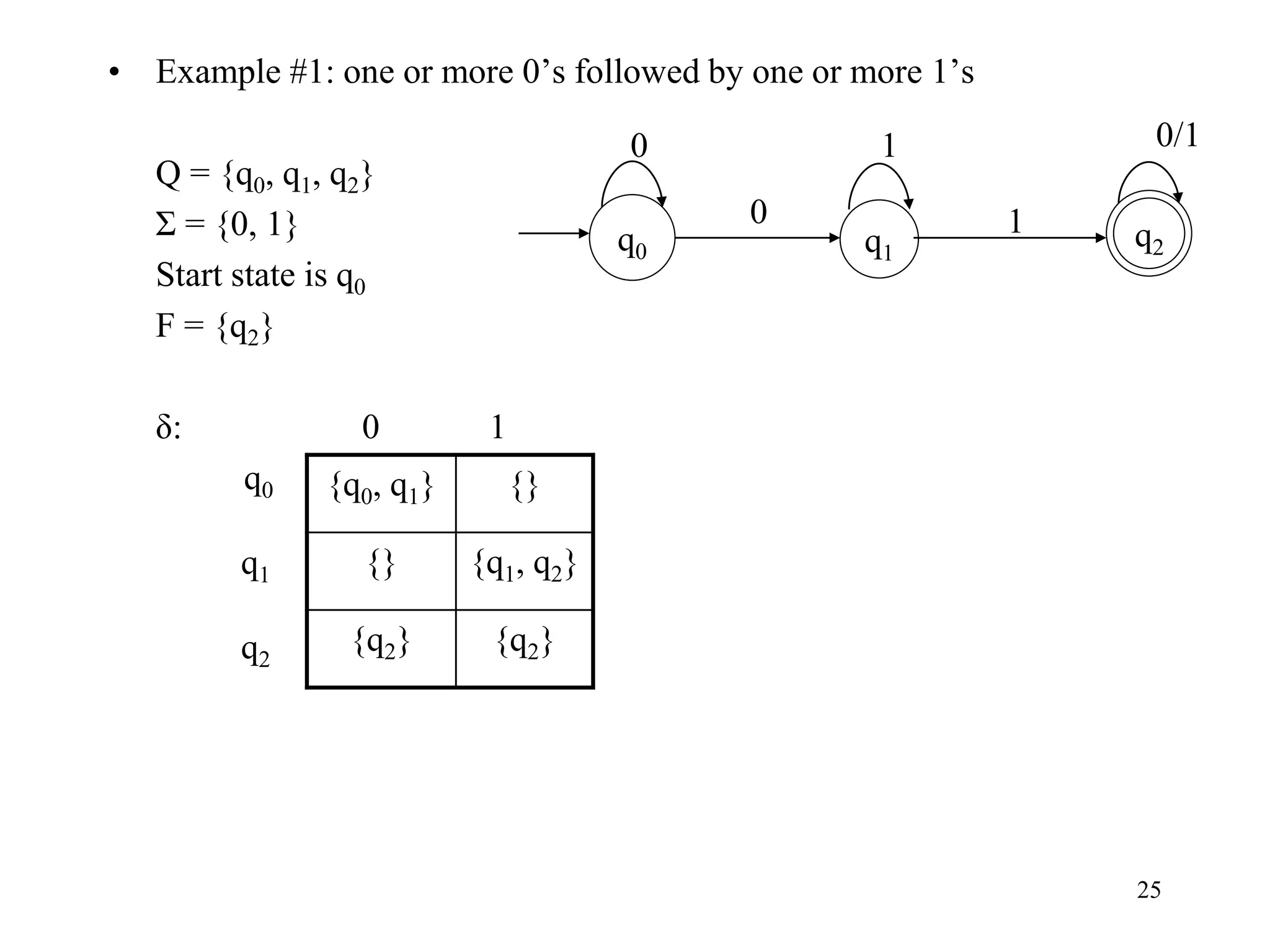

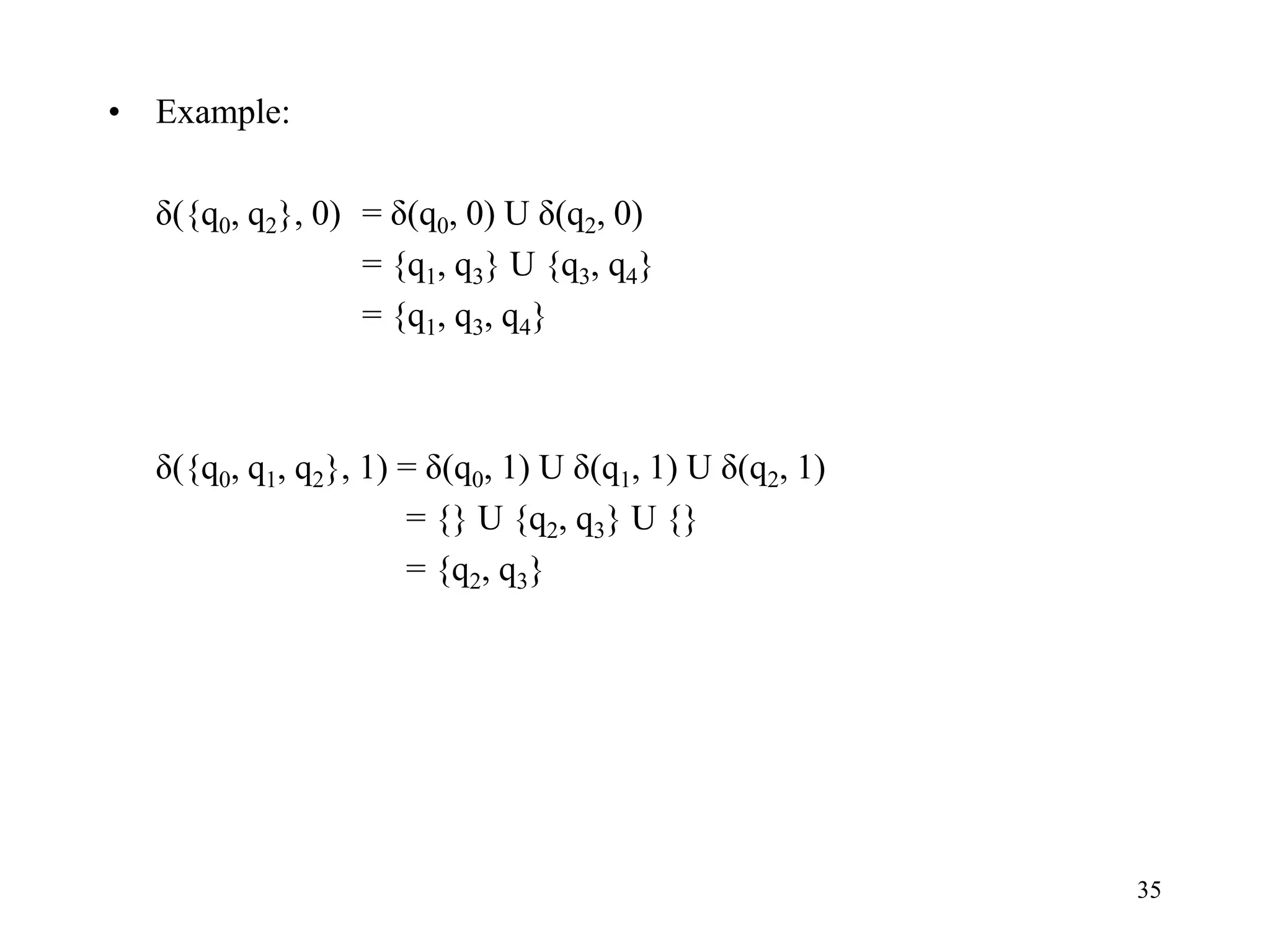

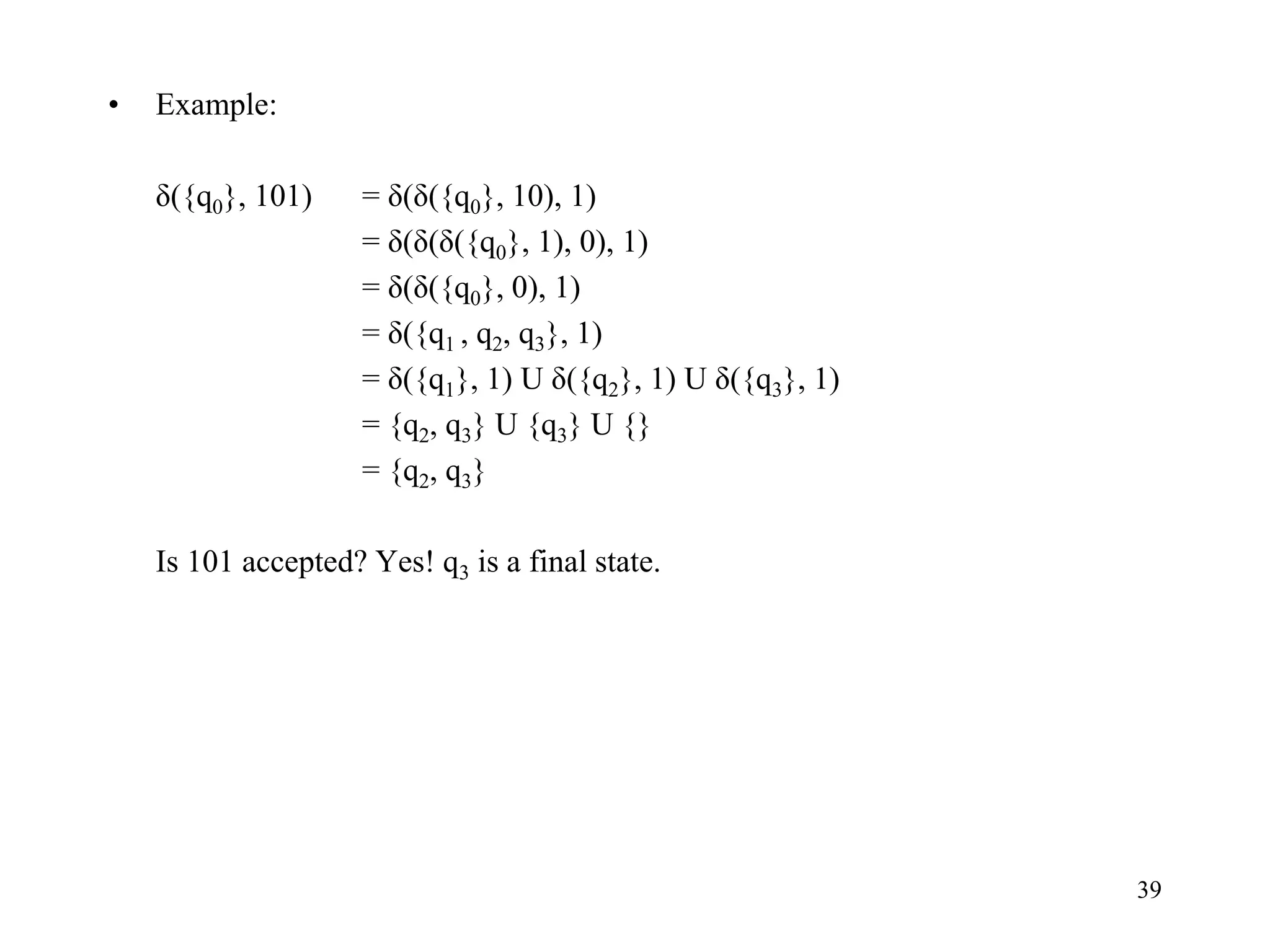

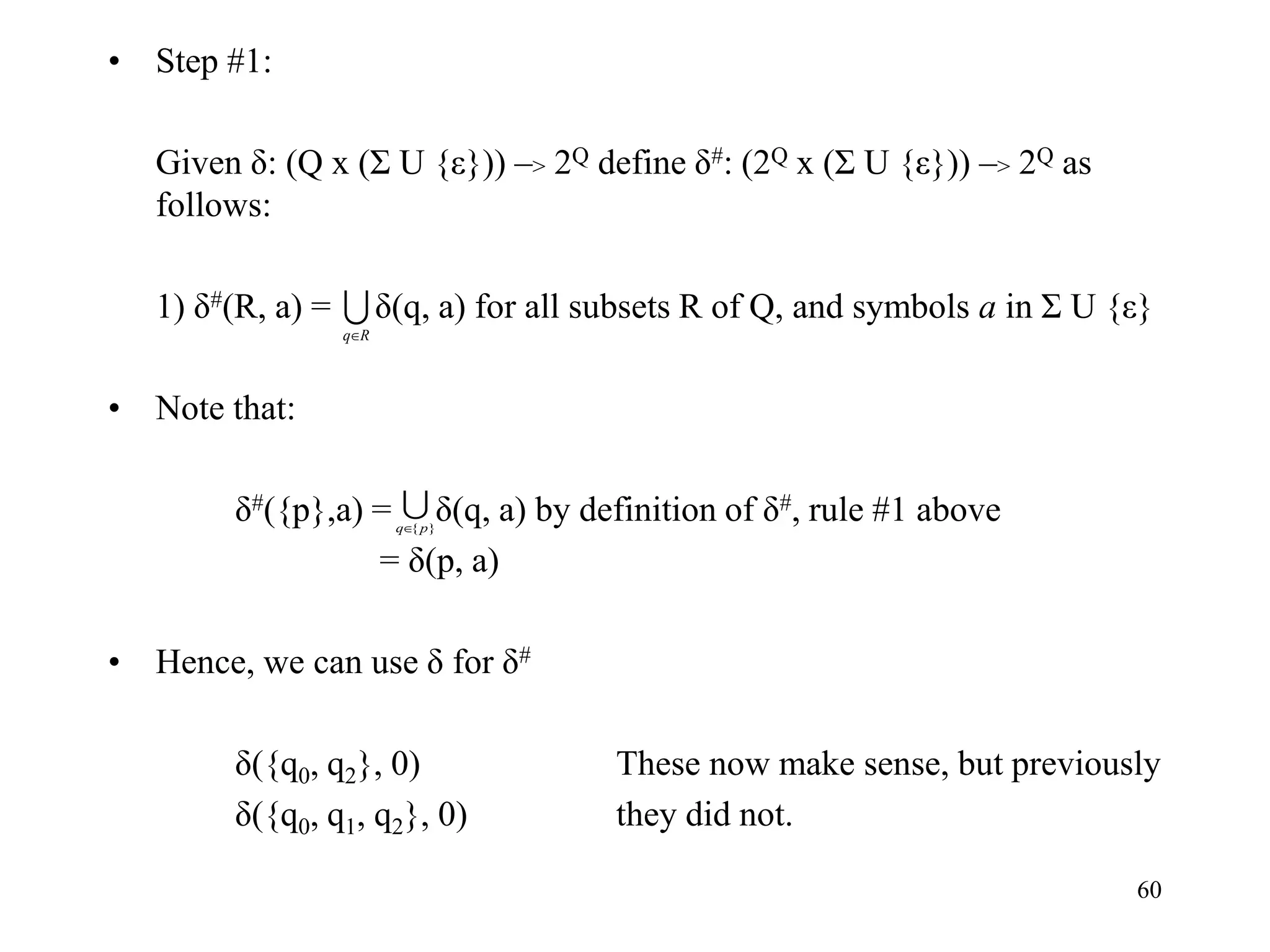

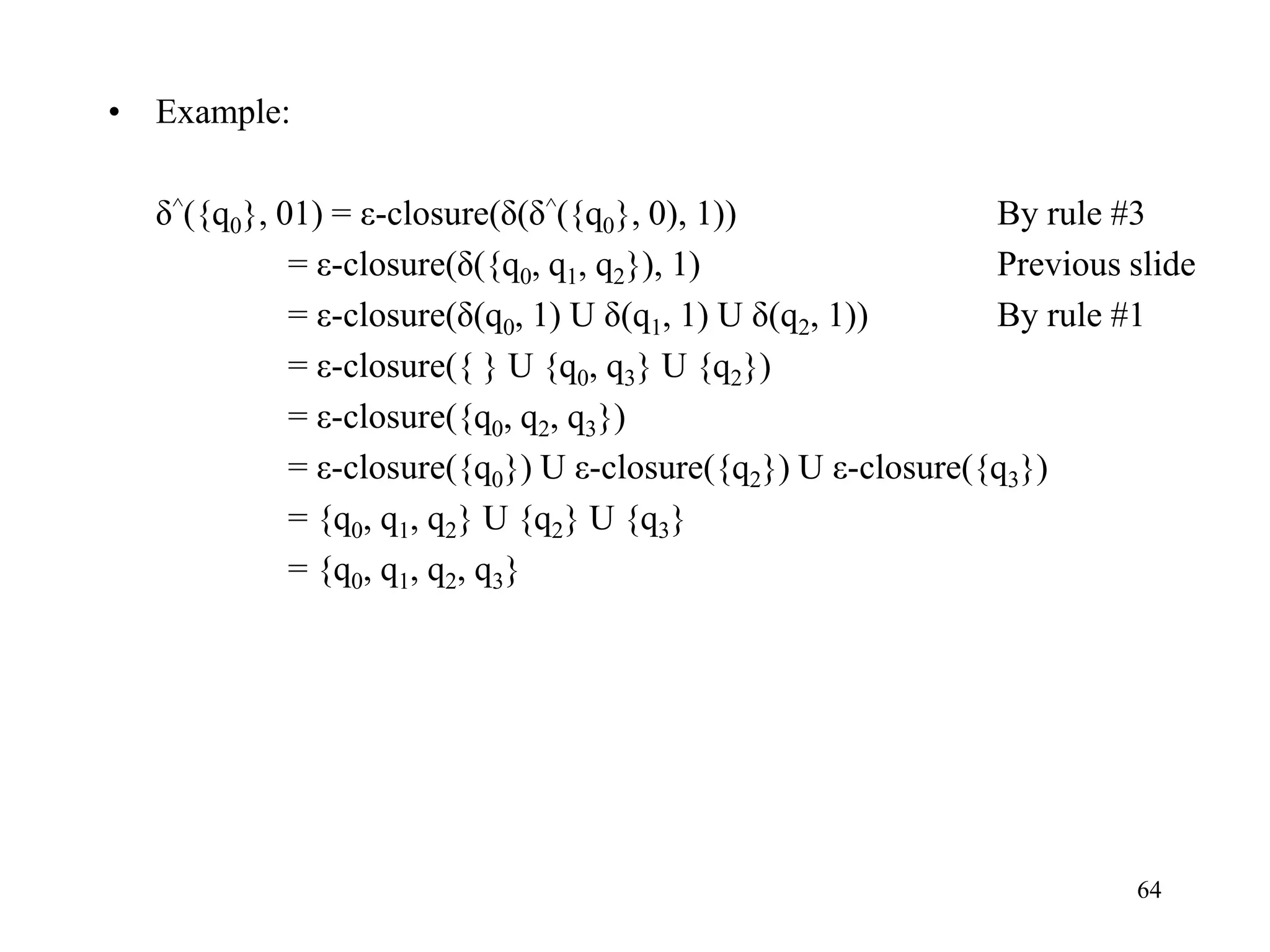

![47

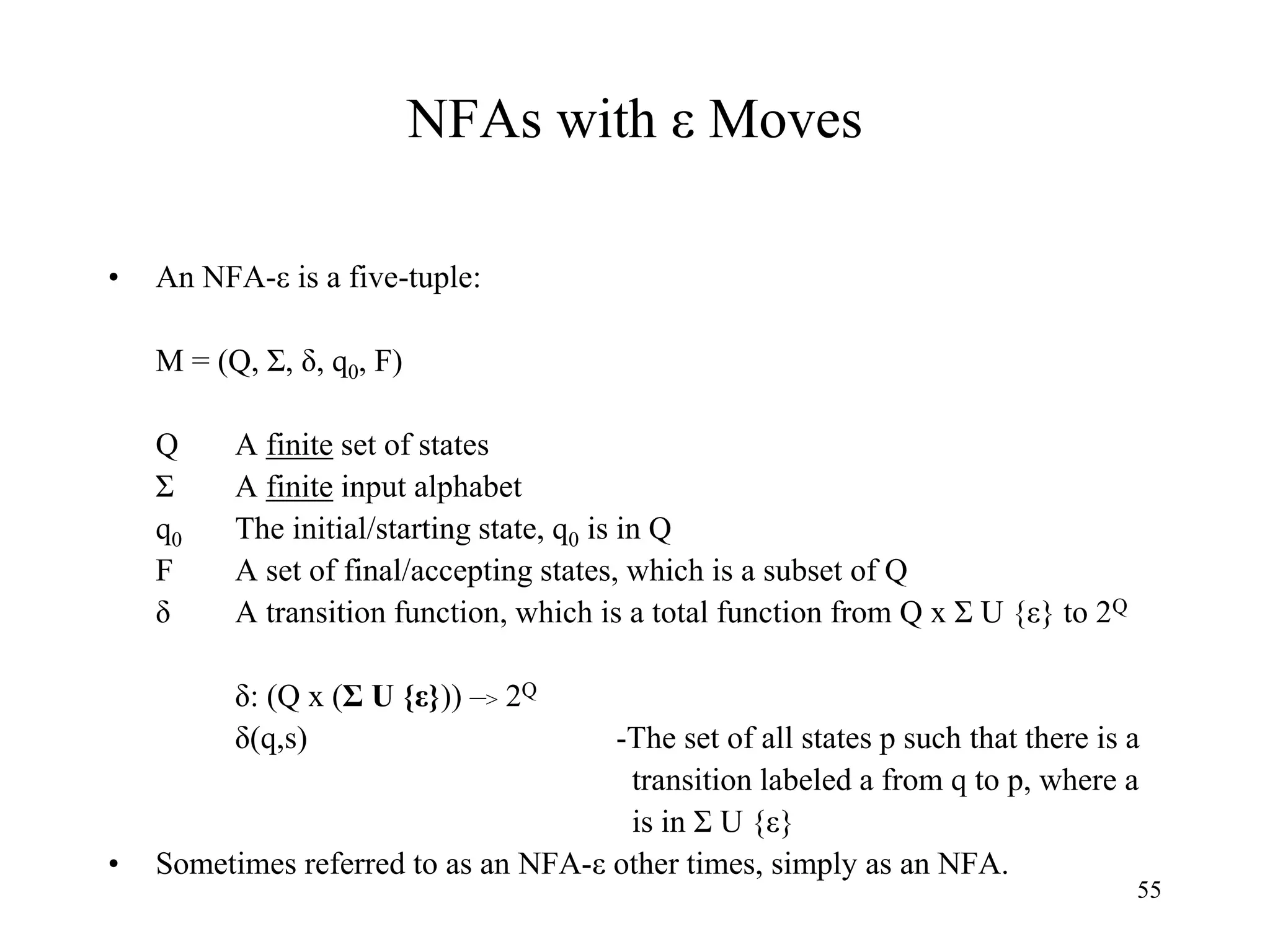

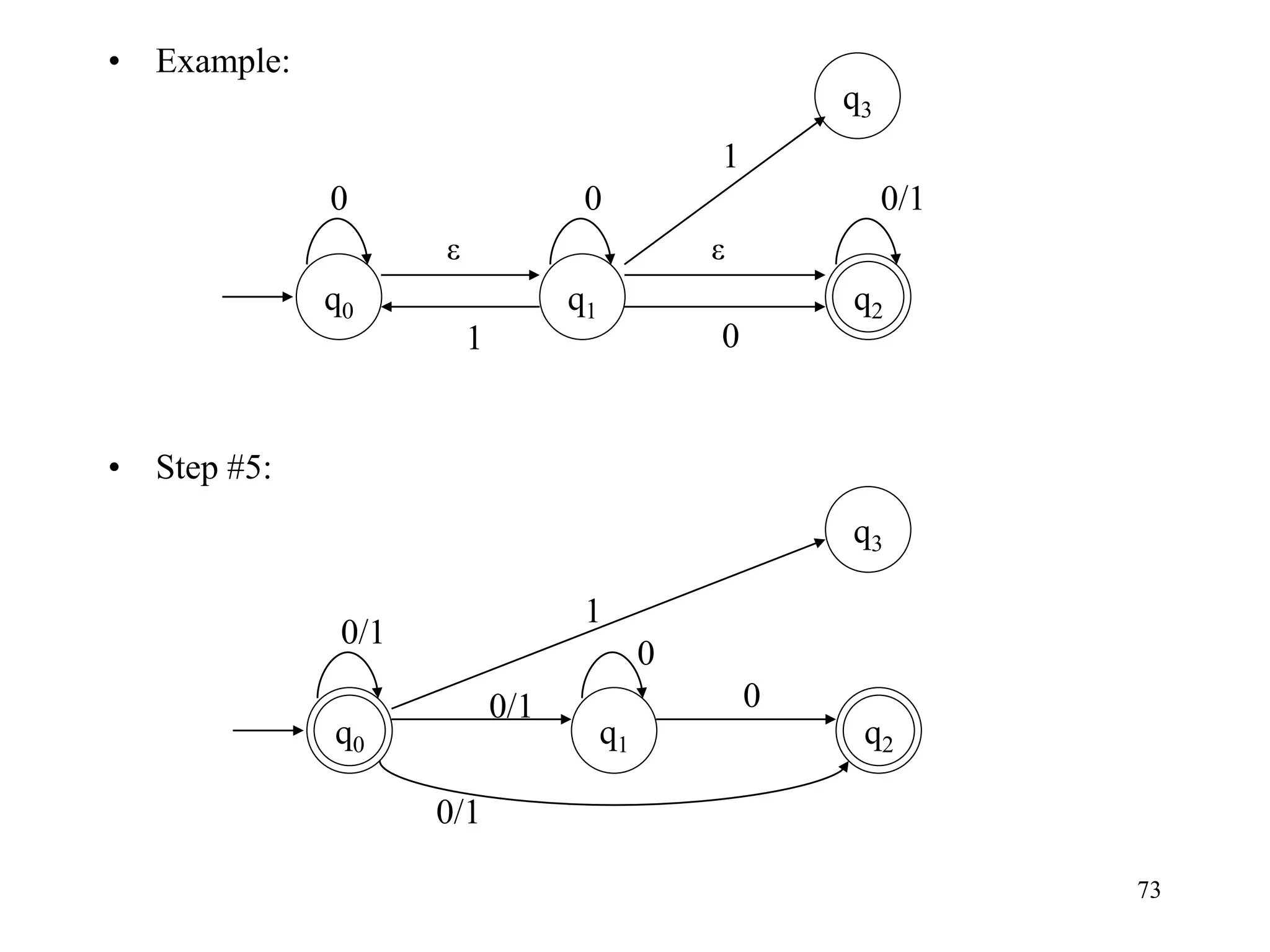

• Example of creating a DFA out of an NFA (as per the constructive

proof):

-->q0

δ for DFA: 0 1 q1

->q0

[q1]

[ ]

q1

q0

0

0/1

0

{q1}

write as

[q1]

{}

write as

[ ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finiteautomata1-230920000545-37281e08/75/FiniteAutomata-1-ppt-47-2048.jpg)

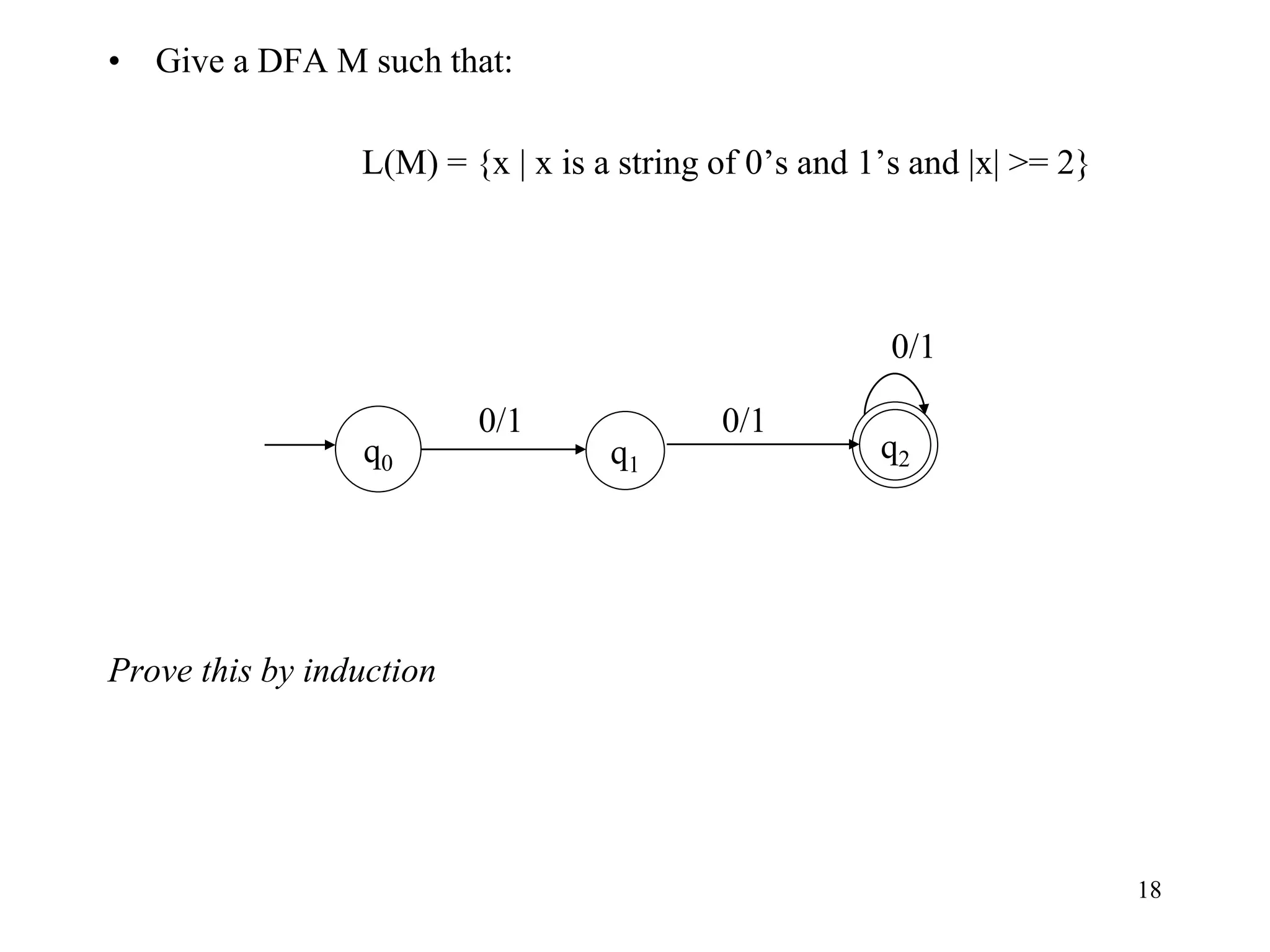

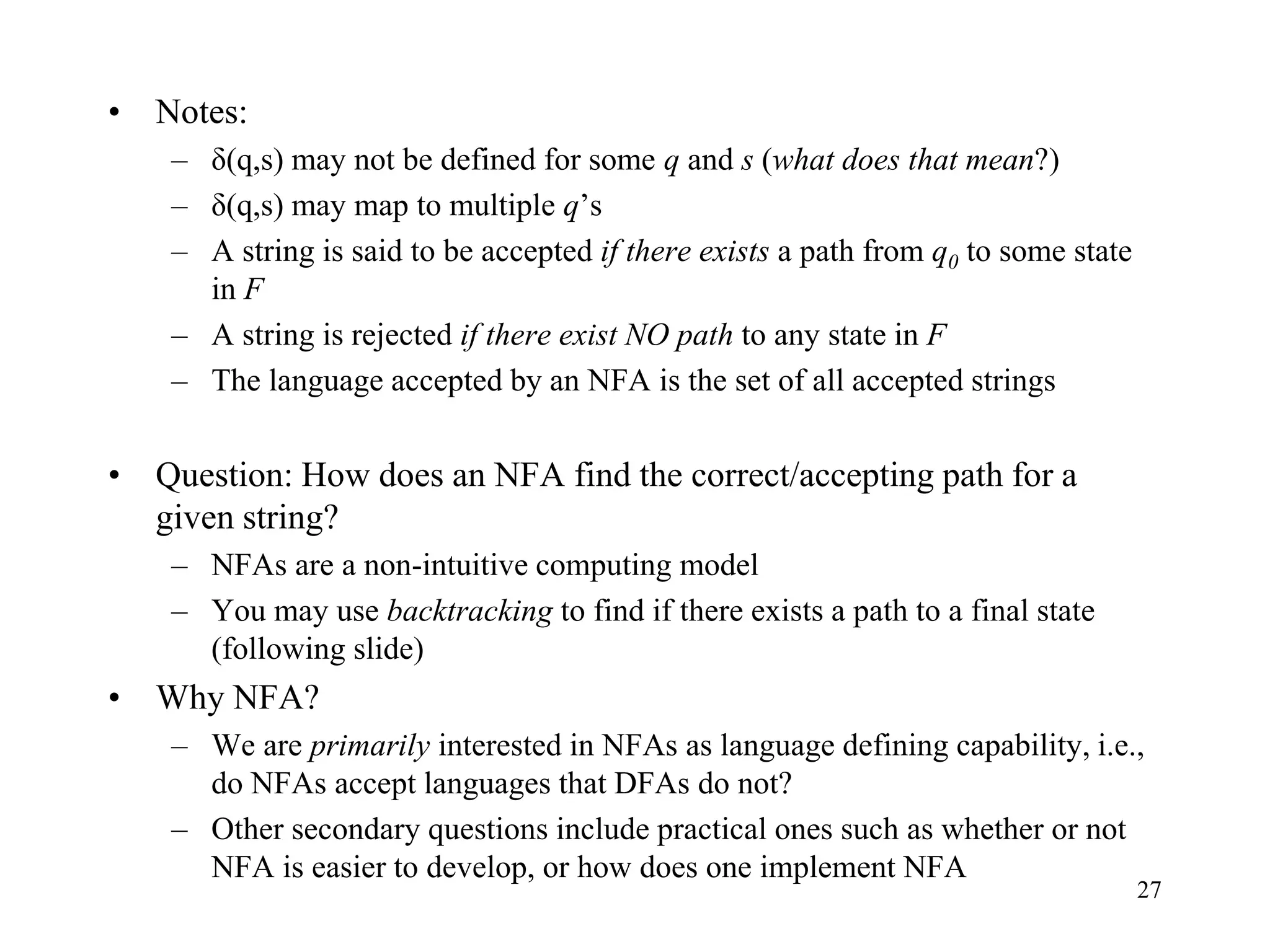

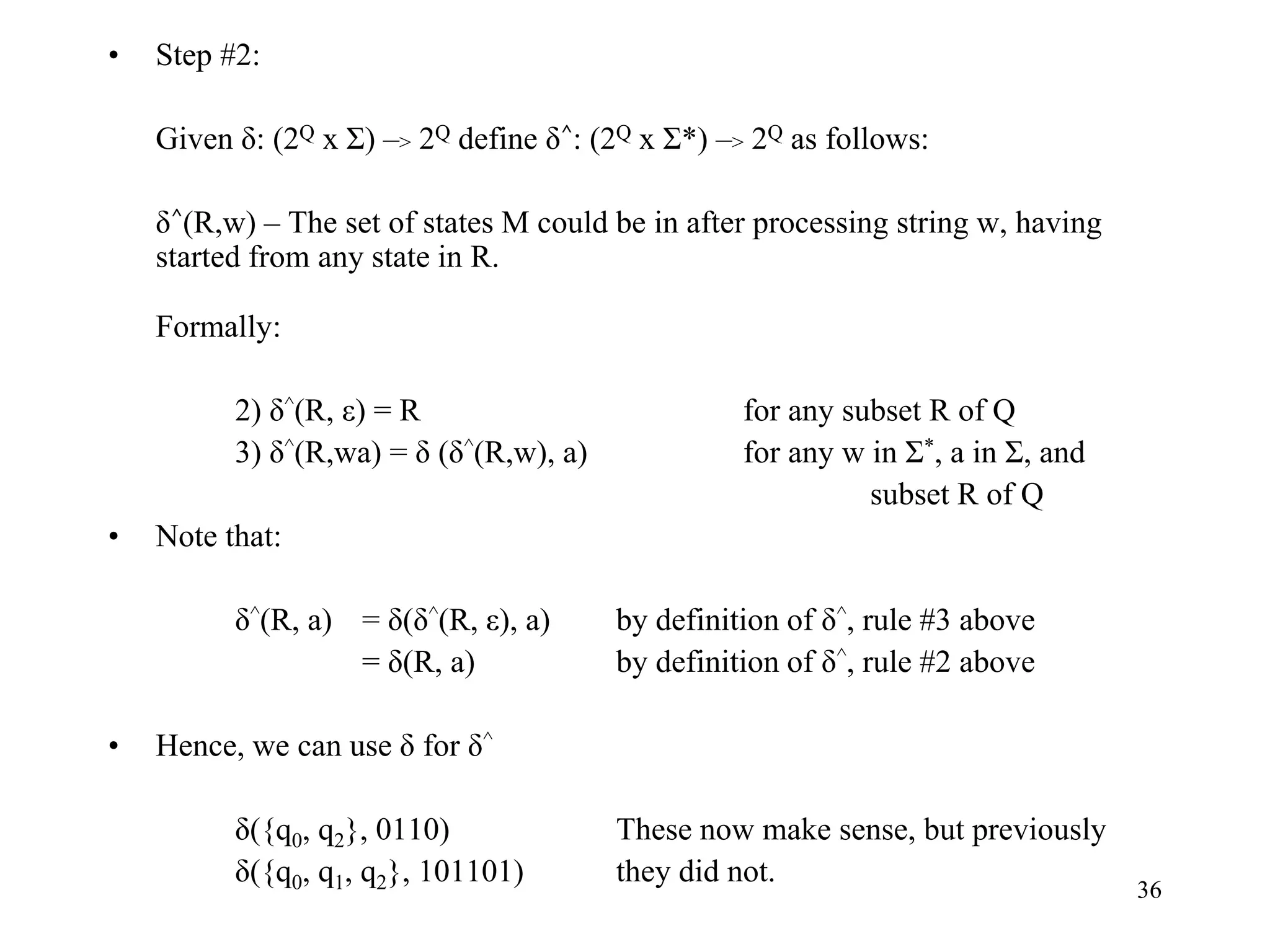

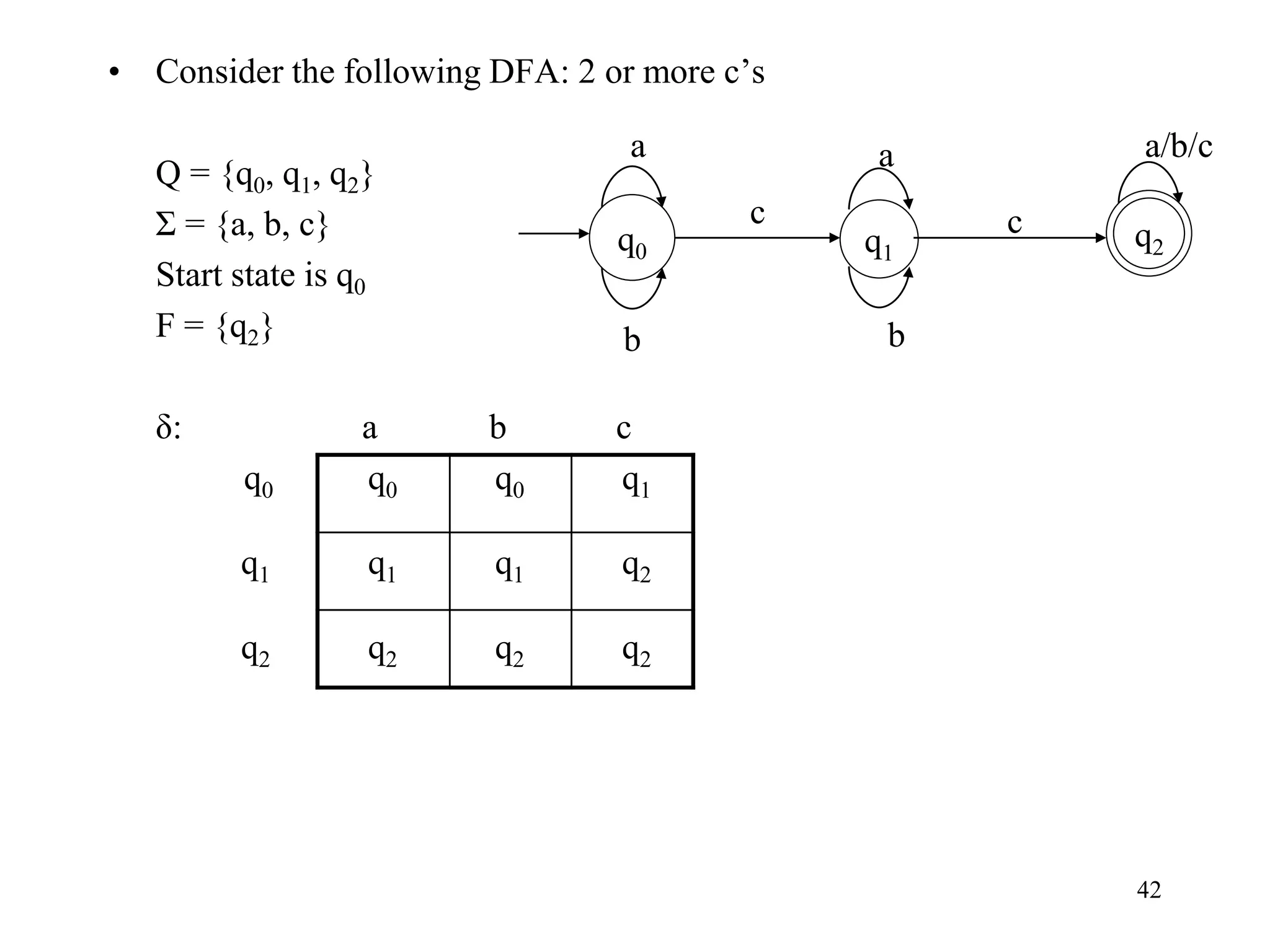

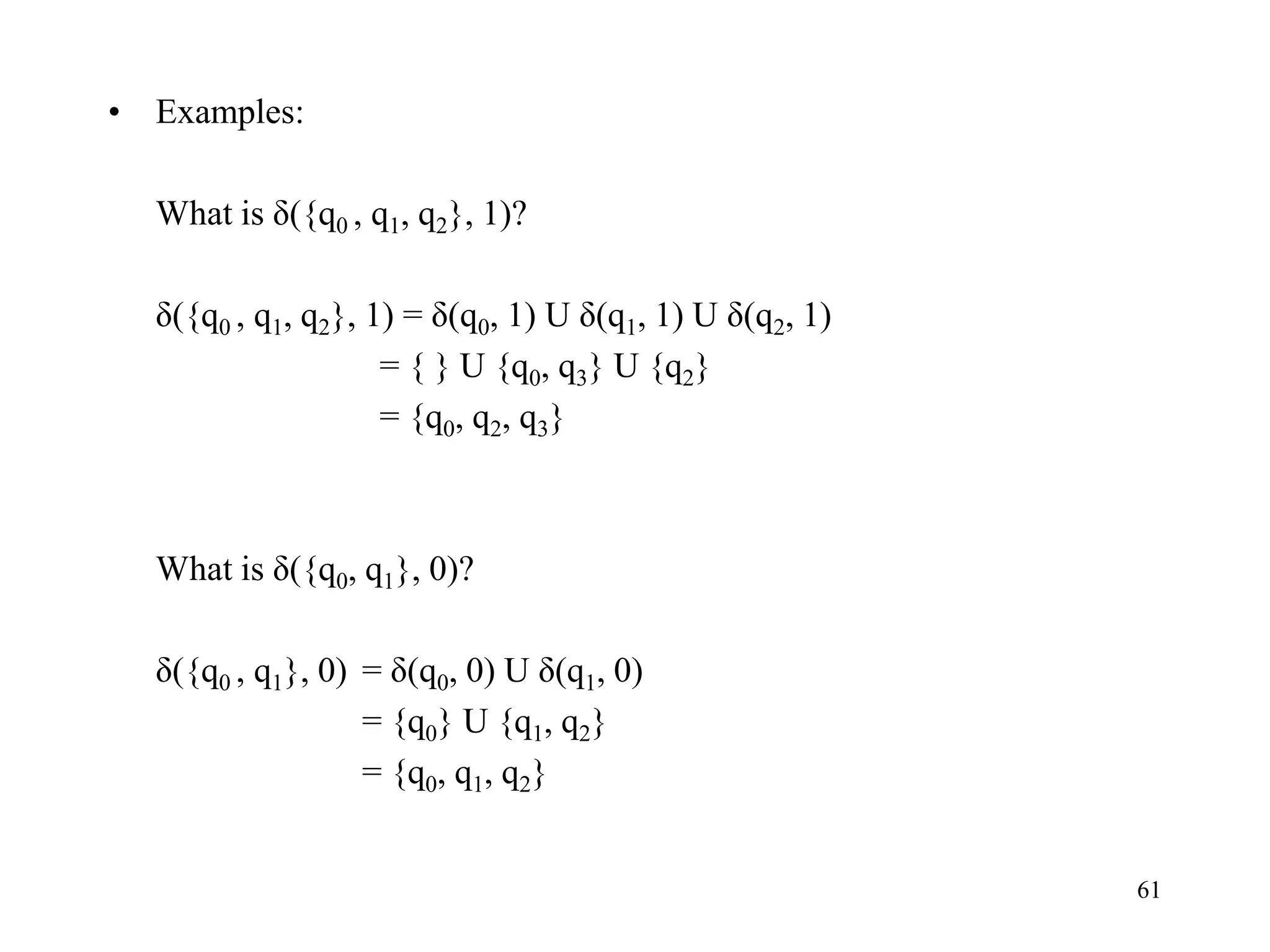

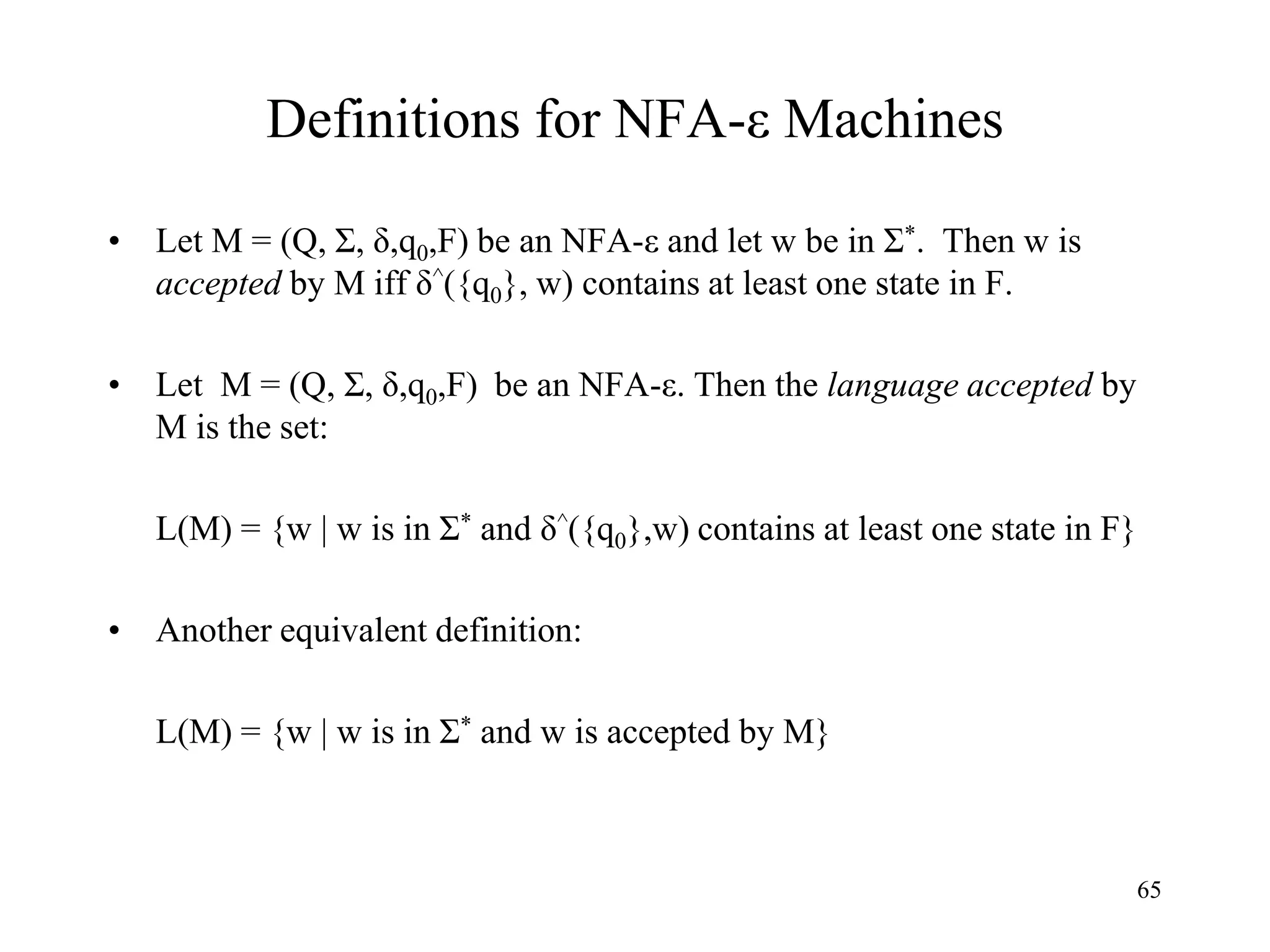

![48

• Example of creating a DFA out of an NFA (as per the constructive

proof):

δ: 0 1

->q0

[q1]

[ ]

[q01]

q1

q0

0

0/1

0

{q1}

write as

[q1]

{}

{q0,q1}

write as

[q01]

{q1}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finiteautomata1-230920000545-37281e08/75/FiniteAutomata-1-ppt-48-2048.jpg)

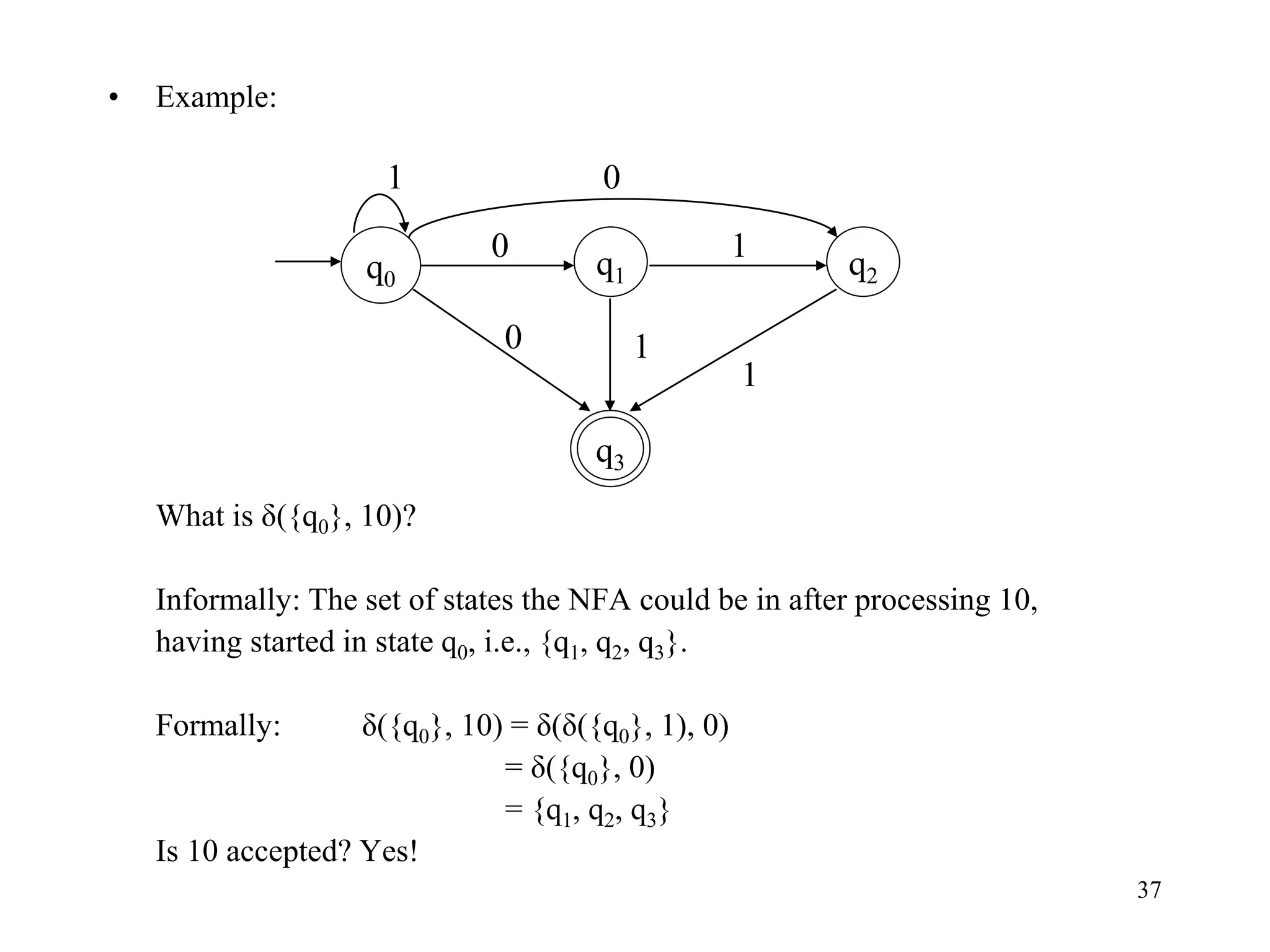

![49

• Example of creating a DFA out of an NFA (as per the constructive

proof):

δ: 0 1

->q0

[q1]

[ ]

[q01]

q1

q0

0

0/1

0

{q1}

write as

[q1]

{}

{q0,q1}

write as

[q01]

{q1}

[ ] [ ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finiteautomata1-230920000545-37281e08/75/FiniteAutomata-1-ppt-49-2048.jpg)

![50

• Example of creating a DFA out of an NFA (as per the constructive

proof):

δ: 0 1

->q0

[q1]

[ ]

[q01]

q1

q0

0

0/1

0

{q1}

write as

[q1]

{}

{q0,q1}

write as

[q01]

{q1}

[ ] [ ]

[q01] [q1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finiteautomata1-230920000545-37281e08/75/FiniteAutomata-1-ppt-50-2048.jpg)

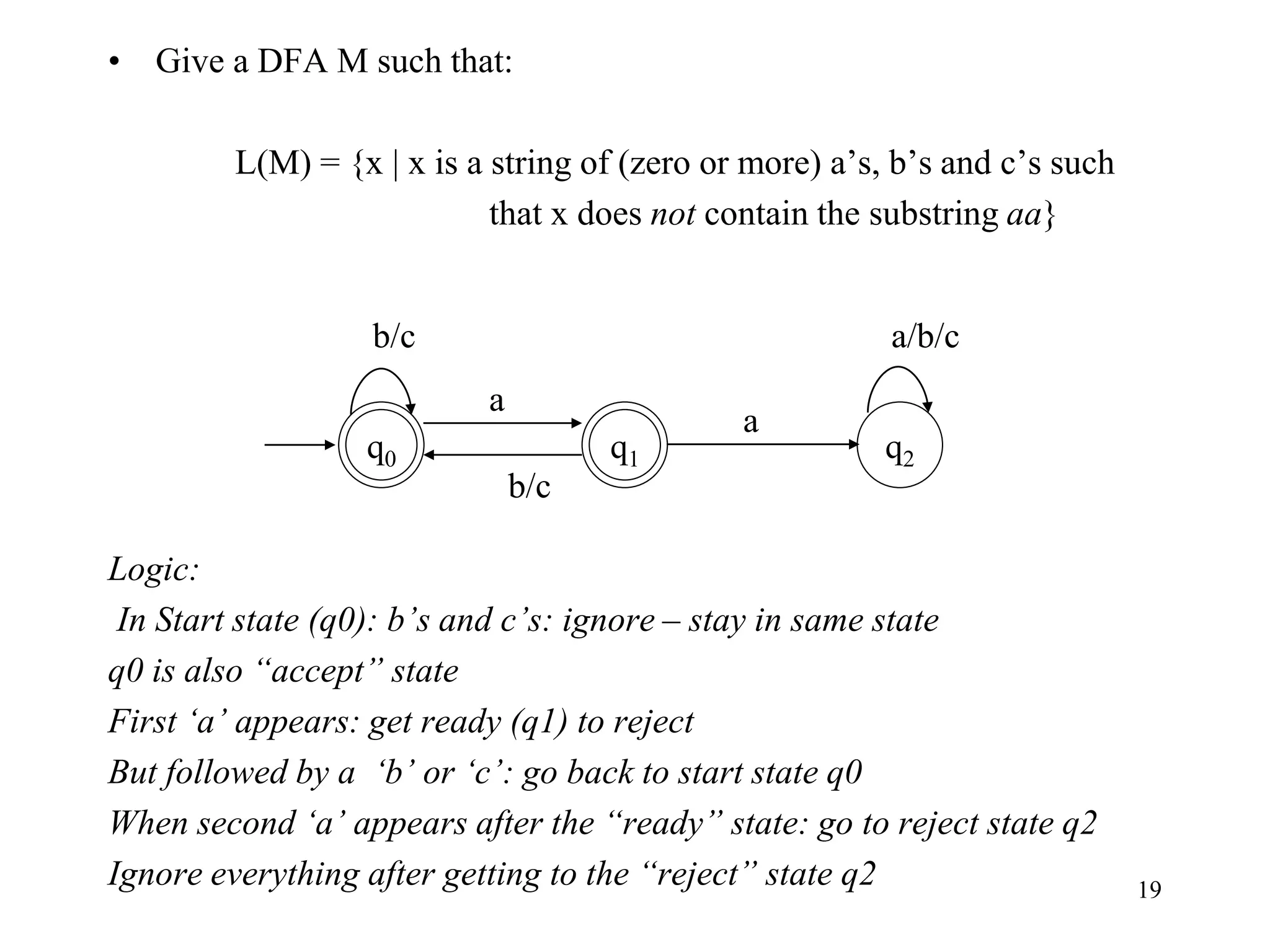

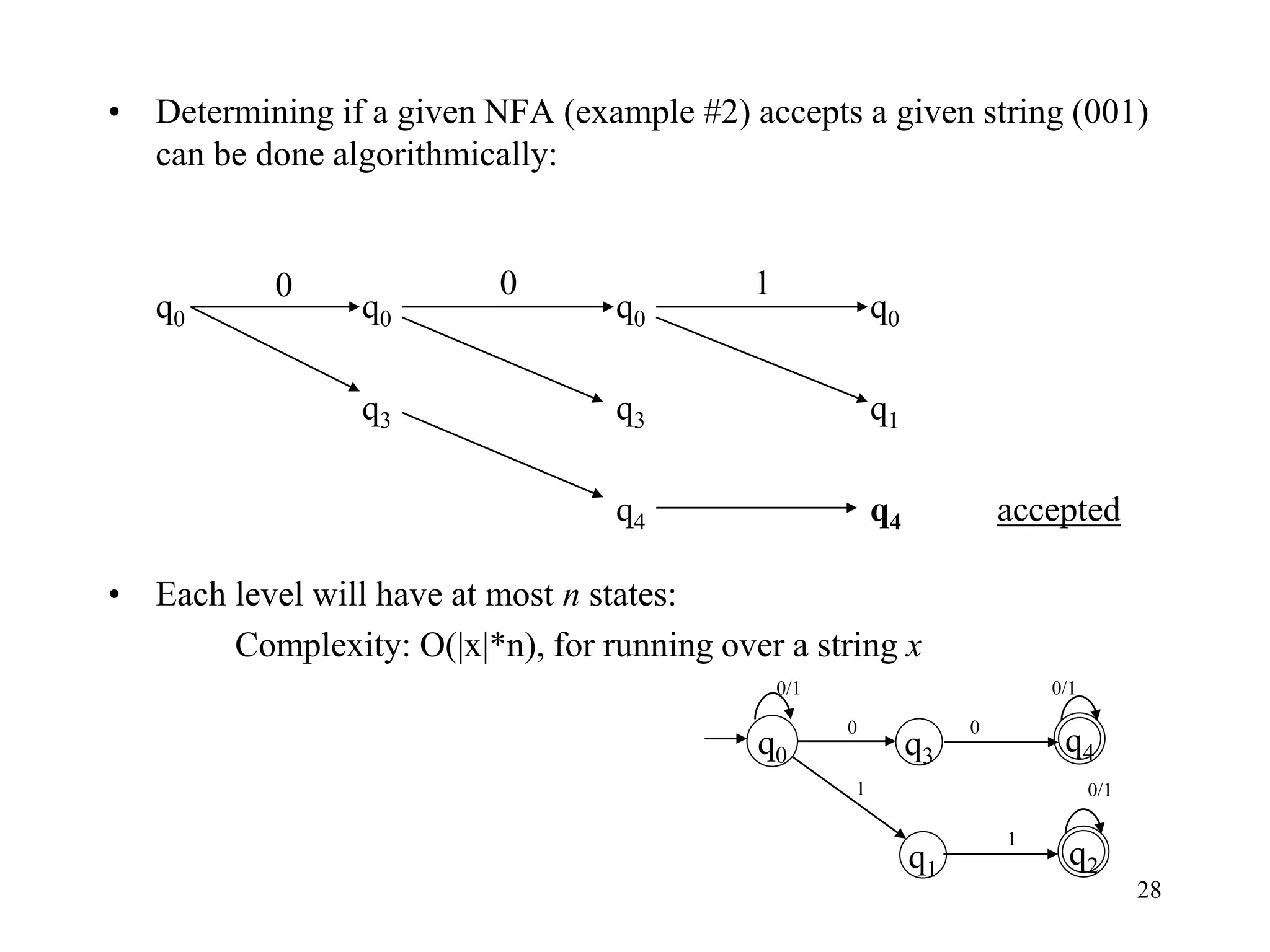

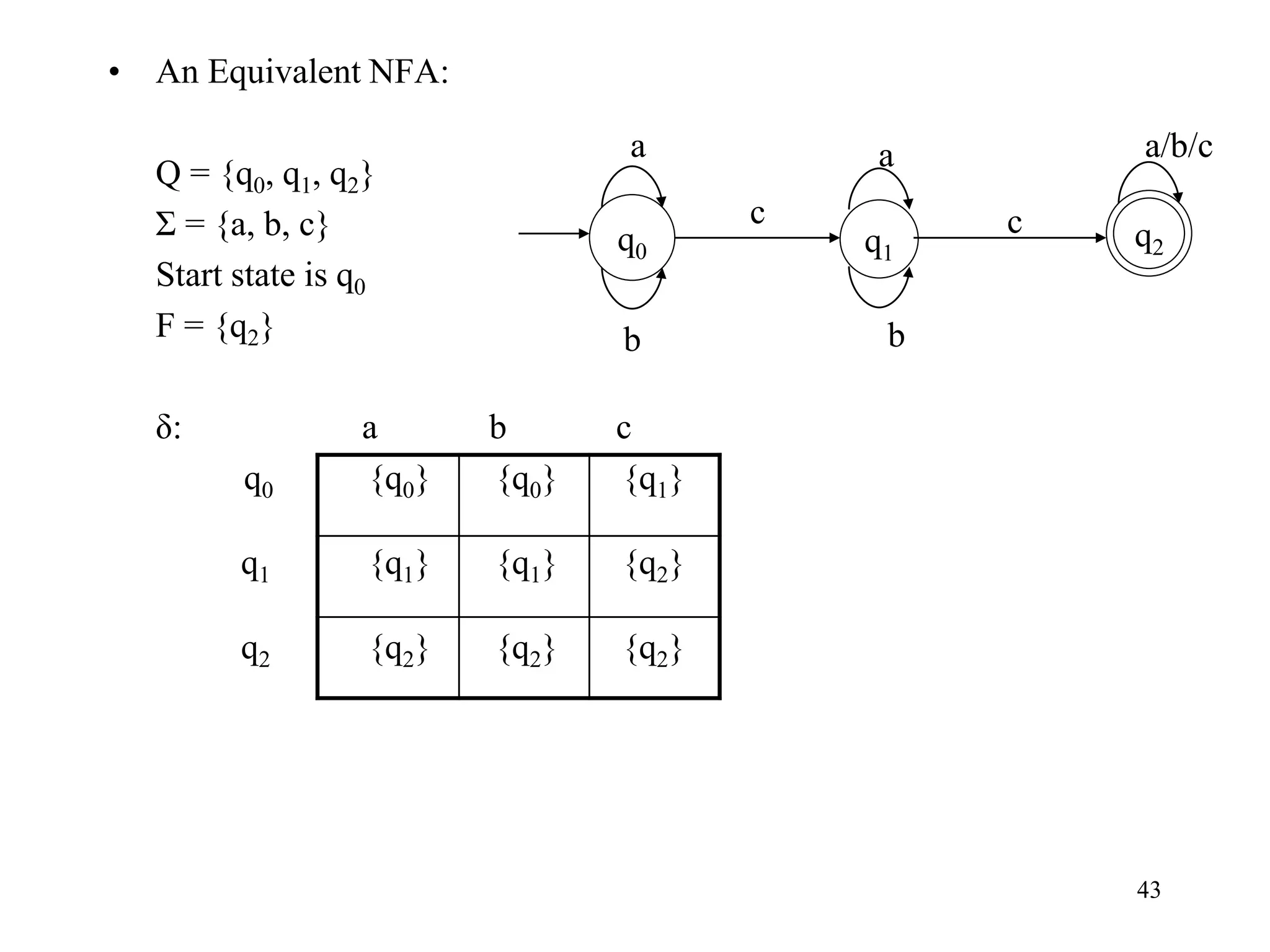

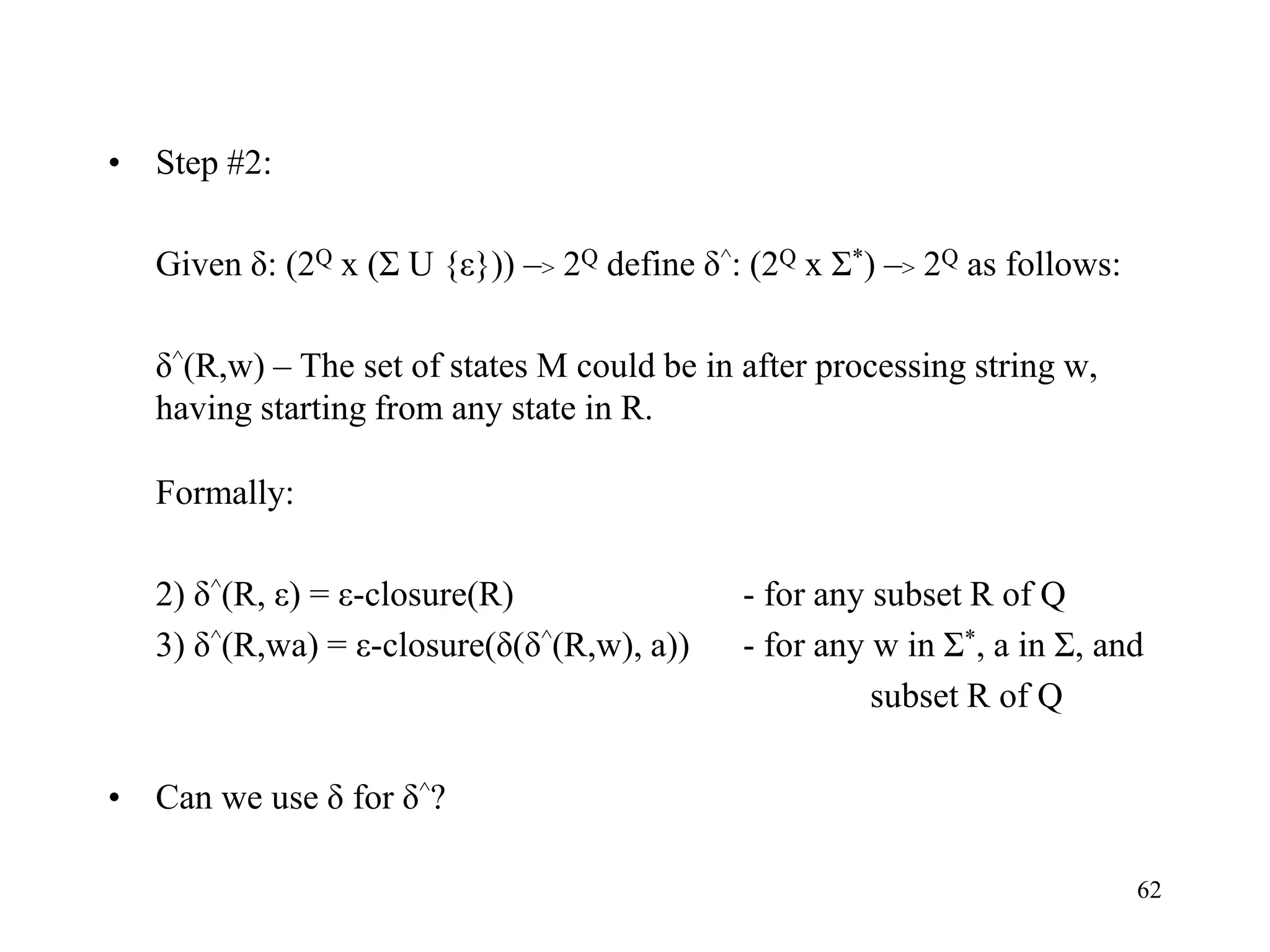

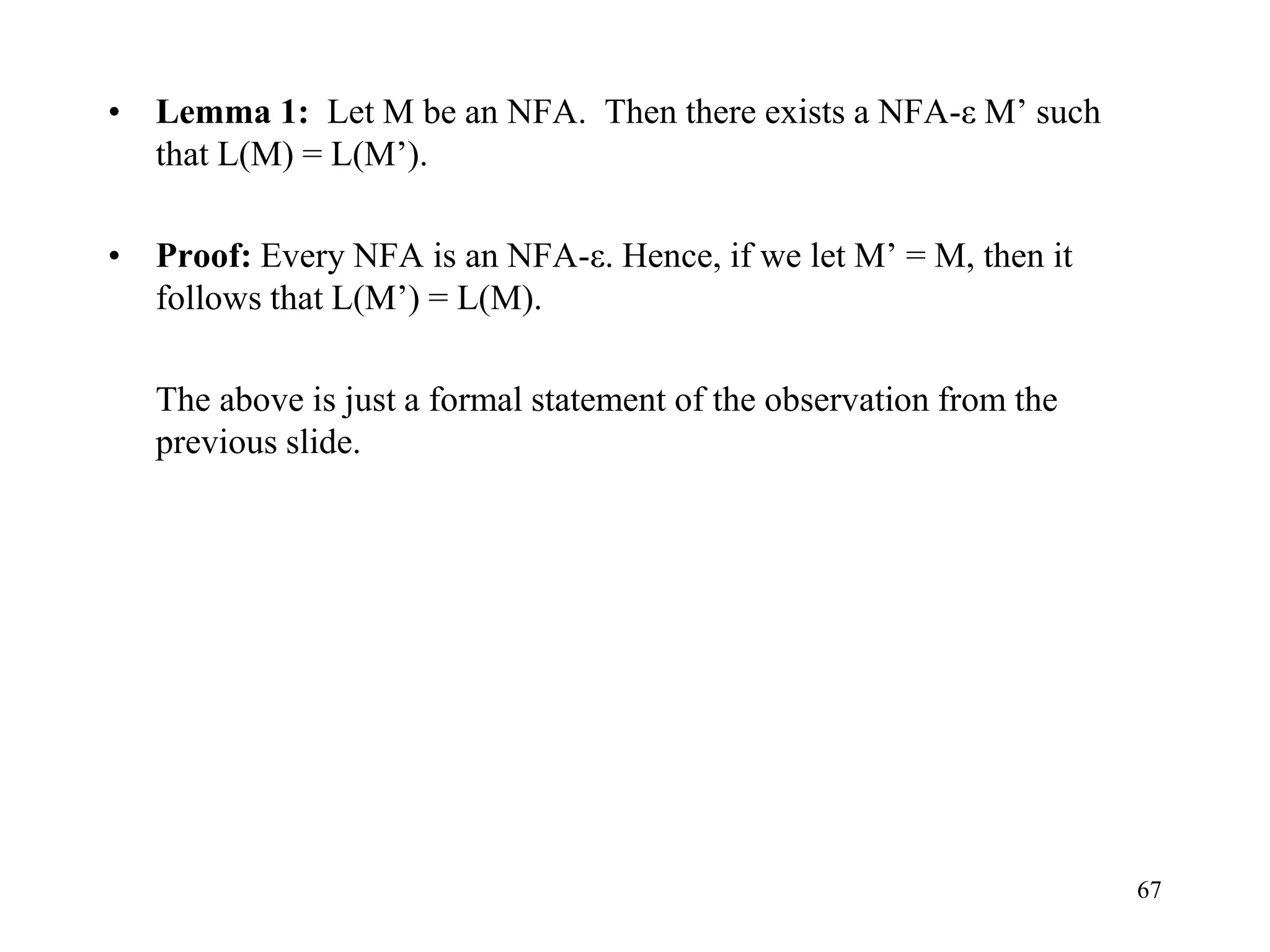

![51

• Construct DFA M’ as follows:

δ({q0}, 0) = {q1} => δ’([q0], 0) = [q1]

δ({q0}, 1) = {} => δ’([q0], 1) = [ ]

δ({q1}, 0) = {q0, q1} => δ’([q1], 0) = [q0q1]

δ({q1}, 1) = {q1} => δ’([q1], 1) = [q1]

δ({q0, q1}, 0) = {q0, q1} => δ’([q0q1], 0) = [q0q1]

δ({q0, q1}, 1) = {q1} => δ’([q0q1], 1) = [q1]

δ({}, 0) = {} => δ’([ ], 0) = [ ]

δ({}, 1) = {} => δ’([ ], 1) = [ ]

[ ]

1 0

[q0q1]

1

[q1]

0

0/1

[q0]

1

0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finiteautomata1-230920000545-37281e08/75/FiniteAutomata-1-ppt-51-2048.jpg)

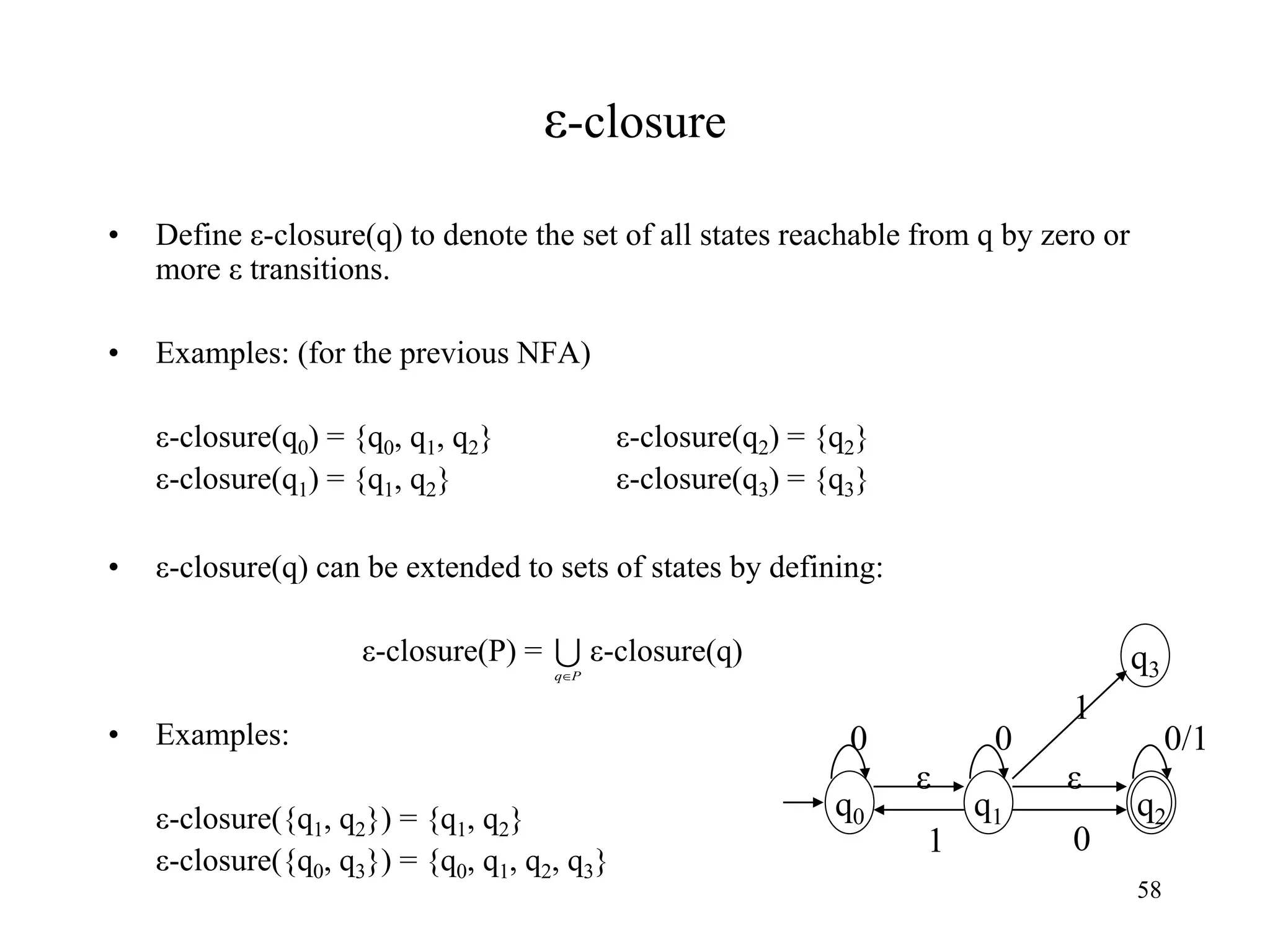

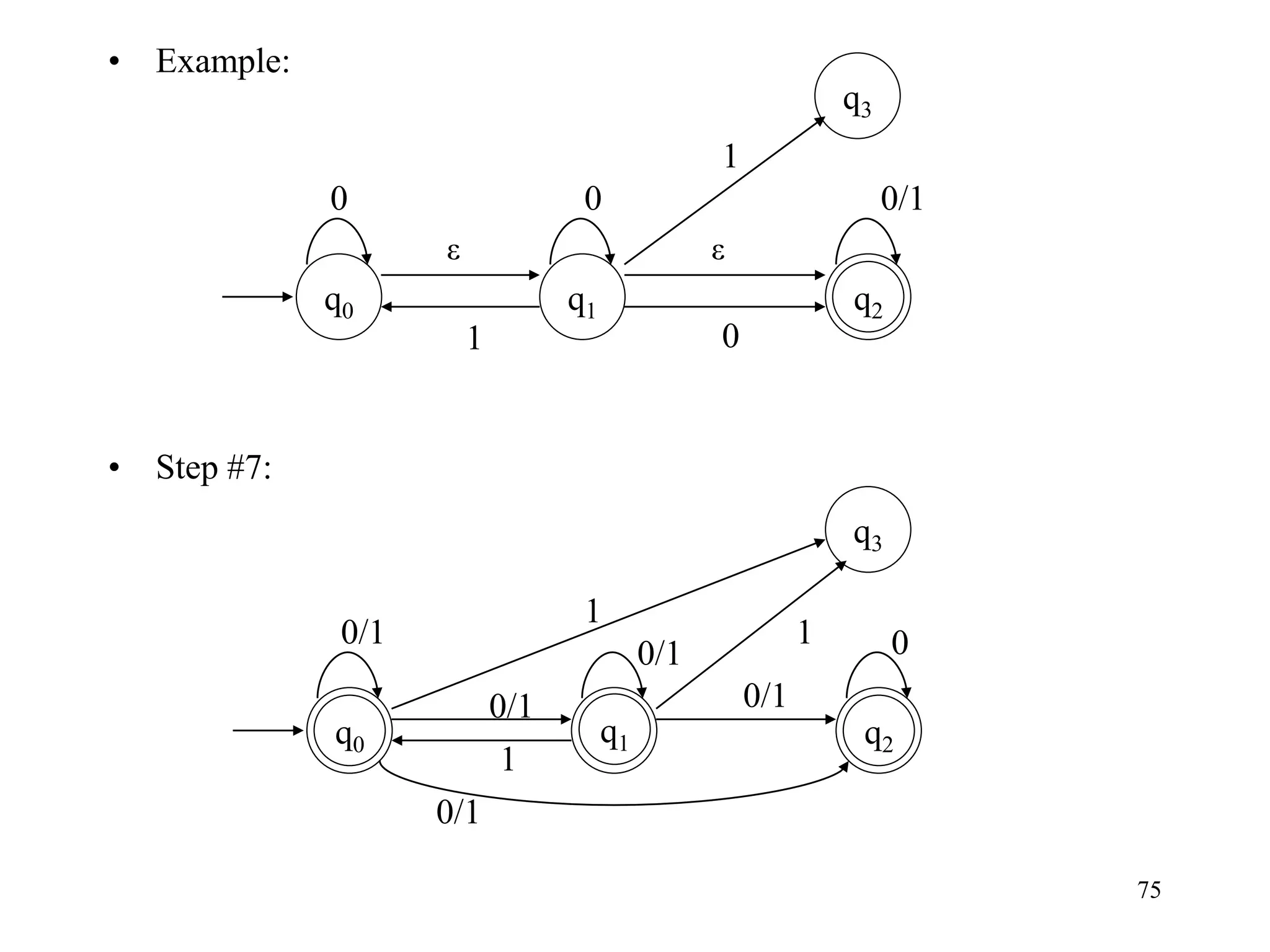

![76

• Example:

• Step #8: [use table of e-closure]

– Done!

q0

ε

0/1

q2

1

0

q1

0

q3

ε

0

1

q2

q1

q3

q0

0/1

0/1

0/1

1

0/1

0/1

1

1 0/1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finiteautomata1-230920000545-37281e08/75/FiniteAutomata-1-ppt-76-2048.jpg)