Eulexia is a wearable spell-checking aid designed for Google Glass. It uses optical character recognition to detect misspelled words in handwritten text. The user is then presented spelling suggestions one word per card which they can listen to via text-to-speech. Initial prototypes had challenges with word recognition and adapting to the Google Glass interface. The final design displays one spelling suggestion per card to better utilize the limited screen space.

![Eulexia: A Wearable Aid For Spell-checking

SEBASTIAN CHEAH, BUSHENG LOU, MICHELLE WU, PHOEBE GAO, and ANDREW DU,

University of California, San Diego

With Eulexia, we wanted to create an application that would help close the learning gap between dyslexic and non dyslexic

individuals. Word processors can to spell checking, but often we find ourselves in situations (homework assignments, white

boarding during company meetings, etc) that require handwriting. We envision Eulexia as a solution to this issue by providing

a ubiquitous form of spell checking for hand written documents. Our prototype is currently limited to accurate processing of

typed text and neat handwritten text, but access to a better OCR engine would allow us to easily achieve our vision.

Additional Key Words and Phrases: Dyslexia, Ubiquitous Computing, Optical Character Recognition (OCR), Dictation, Spell-

check and Suggestions, Levenshtein Distance

ACM Reference Format:

Sebastian Cheah, Busheng Lou, Michelle Wu, Phoeba Gao, and Andrew Du. 2015. Eulexia: A Wearable Aid For Spell-checking.

ACM Trans. Appl. Percept. 0, 0, Article 0 ( 2015), 15 pages.

DOI: 0000001.0000001

1. INTRODUCTION

With 3-7% of the population diagnosedand 20% exhibiting degrees of symptomsdyslexia continues to

be one of the most common learning disabilities in America. Characterized by inaccurate word recog-

nition during reading and writing despite the student possessing normal intelligence, dyslexia often

correlates to dysgraphia as well. Dysgraphia mainly entails trouble with written expression, and often

people misspell words when writing by hand [Peterson and Pennington 2012]. Due to this cognitive

disorder, misspellings in the classroom have become commonplace. Existing non-ubiquitous applica-

tions to aid dyslexic students with language and visual processing include spellchecking features in

Word processors and voice assistants such as Amazon Echo. Our ubiquitous approach is to implement

a wearable solution for correcting spelling via a Google Glass application.

The general idea is to offer the wearer a simple and easy-to-use spellchecker that can be utilized in

daily classroom tasks such as when taking notes or completing classwork. By integrating our appli-

cation into a wearable, we provide a method for the user to correct his or her own spelling through

simple steps: tapping to take a picture and swiping between spelling suggestions. People who suffer

from dyslexia do not have issues with audio processing, so we also provide a text-to-speech feature that

enables the user to listen to the spelling of each suggestion.

In section 2, we will describe the motivations and background behind our work.

In section 3, we will outline how we approached designing features for dyslexic users.

In section 4, we will discuss the system development of our application, specifically the architecture

design, the technologies we used, and the features we implemented.

In section 5, we will detail how we tested and evaluated our application.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others

than ACM must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific

permission and/or a fee. Request permissions from permissions@acm.org.

c 2015 ACM. 1544-3558/2015/-ART0 $15.00

DOI: 0000001.0000001

ACM Transactions on Applied Perception, Vol. 0, No. 0, Article 0, Publication date: 2015.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02321965-523e-41d1-8eb3-067f16de2115-160307211847/75/Eulexia-A-Wearable-Aid-For-Spell-checking-1-2048.jpg)

![0:2 • S. Cheah, B. Lou, M. Wu, P. Gao, and A. Du

In section 6, we will cover our collaboration, namely our team structure and how we solved issues.

In section 7, we will conclude our work and discuss future directions for our research.

2. MOTIVATION AND BACKGROUND

2.1 The Problem

Dyslexia is a condition that affects how the brain processes written and spoken language, which means

it specifically has an impact on writing, spelling, and speaking; however listening is not affected. Due

to this, students with dyslexia require methods of learning alternative to what conventionally exists

for the general population (i.e. listening to audio versions of a text since reading comprehension is

difficult).

A major side effect of this invisible illness is its tendency to affect an individual’s chances of educa-

tional success due to early experiences with the condition. Take, for example, two students, Jack and

Jill. Jack suffers from a mild form of dyslexia and was never diagnosed. Jill is not affected by dyslexia.

They both go through early elementary school, Jack struggling to keep up with other kids due to his

impaired reading and writing abilities, not really knowing why he is unable to learn as well as the

other students. Jill excels in all subjects, with a natural affinity for reading and obtaining new knowl-

edge. An important note is that Jack possesses intelligence akin to Jill, and simply becomes deficient

because he does not have the resources that he needs accessible in order to learn in an alternative way.

As the years go by, Jack begins to believe he simply is not as smart as the other students and gives

up trying on his assignments-slacking off and eventually dropping out of high school. Jill continues

to succeed in school-earning straight A’s, acceptance into a top university, and landing a competitive

position at a top company. This opportunistic gap is the motivation behind our application, Eulexia.

The technical problem-or the reason why this problem does not have a trivial solution-is the fact that

dyslexia cannot be cured. Individuals suffering from this condition simply learn to deal with dyslexia

in their own ways over time; however far too often, this happens too late in the game. We need to

target weaknesses caused by dyslexia in earlier stages of development so that effects do not grow

exponentially. Each individual with dyslexia is also unique, which is another reason why this problem

requires a ubiquitous solution, one that modifies itself continuously to fit each user’s needs.

2.2 Previous Solutions

2.2.1 Spell checking on computers. Modern word processors have built-in spell-checking features

such as Microsoft Word and Google Docs, and the latter also comes with a custom dictionary feature

which the user can use to add their commonly misspelled words. Though this feature is useful for

older dyslexics (and are currently used by them), none of these word processors process handwrit-

ing. Younger students may not regularly complete schoolwork on computers and are often assigned

worksheets in the classroom, and they are limited in resources to verify their spelling.

2.2.2 Text-to-Speech. There are multiple existing text-to-speech applications for documents on the

computers, which is useful to dyslexics because they have no issues with processing audio. DCODIA

is a mobile iOS text-to-speech application built for dyslexic students [Hall 2014]. A student takes a

picture of printed text and the application then dictates the words in the text aloud from the image.

While this approach is viable, the user must take out their mobile phone in order to position the camera

and take a picture, and this only works for printed text, not handwriting.

2.2.3 Voice assistants. Amazon Echo, a wireless speaker and voice command device from Ama-

zon.com, and Apple’s Siri provide another alternative solution for dyslexic students to spell-check.

Users can simply query these devices for the correct spelling of a word (i.e. ”Siri, how do you spell

ACM Transactions on Applied Perception, Vol. 0, No. 0, Article 0, Publication date: 2015.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02321965-523e-41d1-8eb3-067f16de2115-160307211847/75/Eulexia-A-Wearable-Aid-For-Spell-checking-2-2048.jpg)

![Eulexia: A Wearable Aid For Proofreading • 0:3

dyslexia?”) [Amazon 2015] [Sheehan 2012]. However, this method becomes reliant on user pronunci-

ation and there is no secondary option if multiple words have the same pronunciation but different

spellings. As solely voice assistants, these devices do not come with a camera feature and cannot pro-

cess written text. Constantly asking for correct spelling also becomes tedious and inefficient for those

with dyslexia because the problem is not that they do not know how to spell a specific word, it is that

they do not realize when they have misspelled one.

3. DESIGN

3.1 Design Idea

Before we could begin to design our application, we needed to familiarize ourselves with the target

user’s needs. To do so, we interviewed Gini Keating, a UX designer with dyslexia who works at Qual-

comm Inc. Through this interview, we gathered the following information on dyslexia, as it pertains to

her case:

—Spelling is still a challenge for her and does not improve over time.

—She spells phonetically, so she often misspells the same word in numerous different ways. However,

she spells Spanish words correctly.

—Text-to-speech feature to spell out loud is very helpful (she sometimes uses Amazon Echo). She also

uses the speech-to-text feature on her smartphone.

—She uses a custom dictionary on her word processor to give her spelling suggestions.

—During company meetings, her coworker writes on the whiteboard for her because one of her autistic

coworkers will be too distracted by misspelled words.

—She would like to either see a rectangle around misspelled words or blur/grey out the other text.

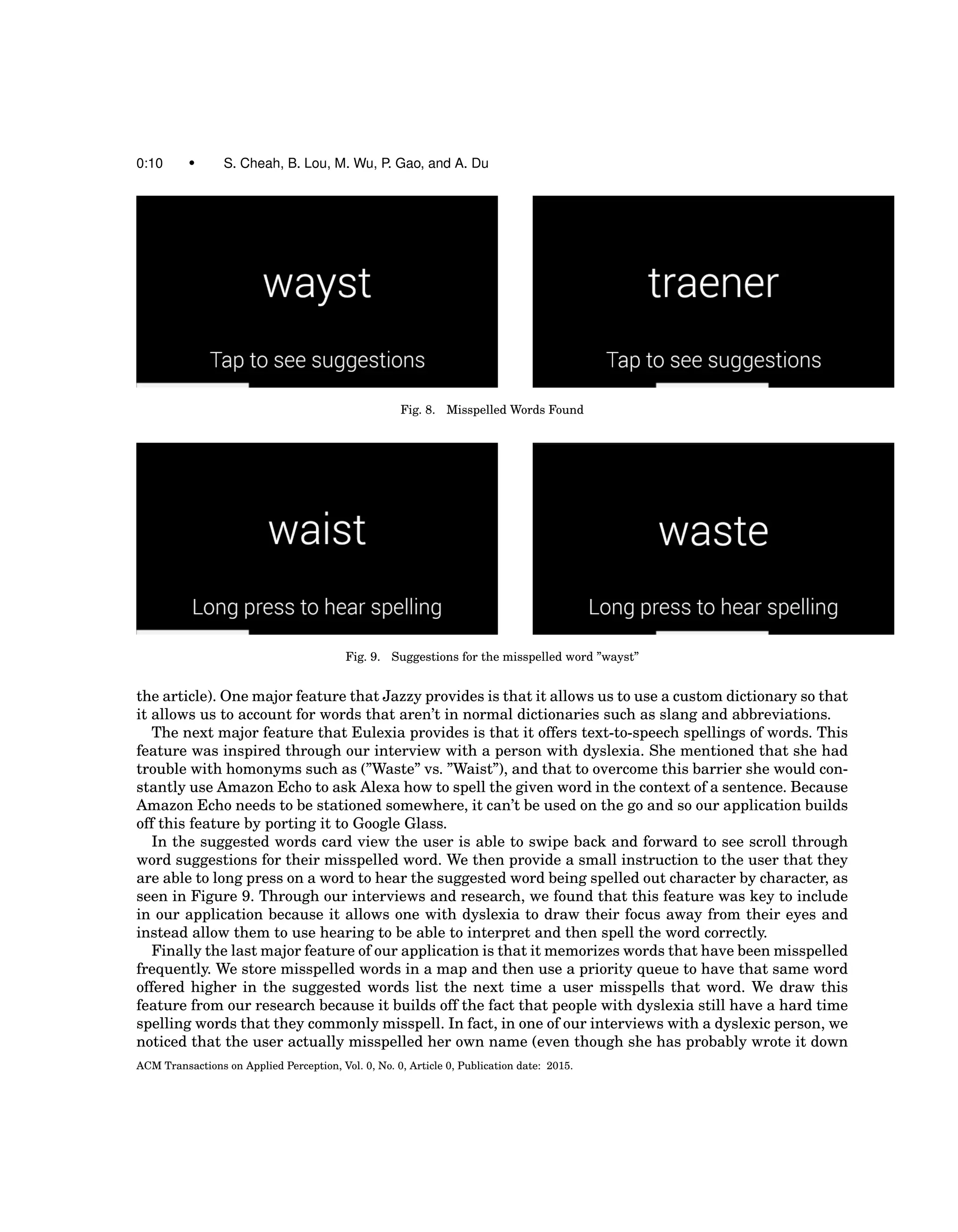

We then had Keating try on Google Glass to locate any problems she has with its current user

interface design. She could read words easily and had no issues with the font or default white color.

With this gathered information, we decided to keep the existing Google Glass font (Roboto) as well

as its white color with the slight shadow behind it. Since a high contrast leads to easier readability, we

set the background of each slide to black. In order to achieve a real-time effect, we intended to leave

the camera in live preview mode while the user writes. When a misspelled word is detected, a red box

would appear around the word and the user can then tap to view spelling suggestions in list format,

with the incorrect spelling in red color (Fig.1.). We also decided to include a text-to-speech feature for

the user to listen to the different spelling suggestions as well as a custom dictionary that prioritizes

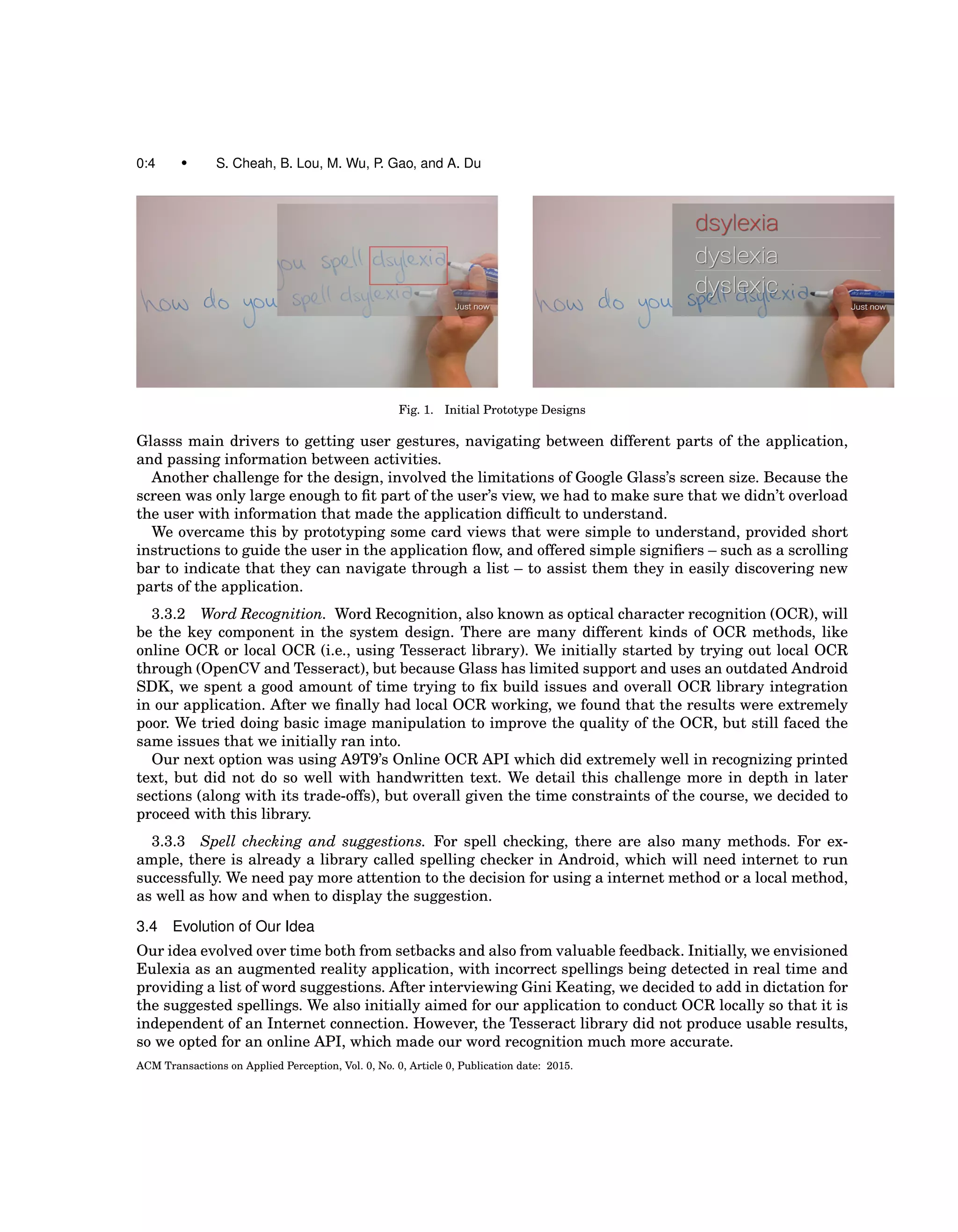

which suggestions to display first based on previous selections.

3.2 Design Prototypes

Our prototype consists of two specific features. First, we would like to provide an image overlaid with

bounding boxes over the misspelled words. Second, using a misspelled word as reference, provide sug-

gestions for the correct spelling. Figure 1 shows an example of how we visualized the Google Glass to

work.

3.3 Design Challenges

3.3.1 User Interface Design. One of the main challenges we faced when designing the user inter-

face was adopting existing design standards with Android and Google Glass applications. Because our

team had limited experience developing for Android, we had to initially spend some time to learn ba-

sic Android application flow. In addition, Google Glass has it’s own design and user flows that built

off of existing Android libraries that we had to learn. For example, the card view was one of Google

ACM Transactions on Applied Perception, Vol. 0, No. 0, Article 0, Publication date: 2015.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02321965-523e-41d1-8eb3-067f16de2115-160307211847/75/Eulexia-A-Wearable-Aid-For-Spell-checking-3-2048.jpg)

![Eulexia: A Wearable Aid For Proofreading • 0:7

Fig. 5. Comparison between Online OCR Service with different images

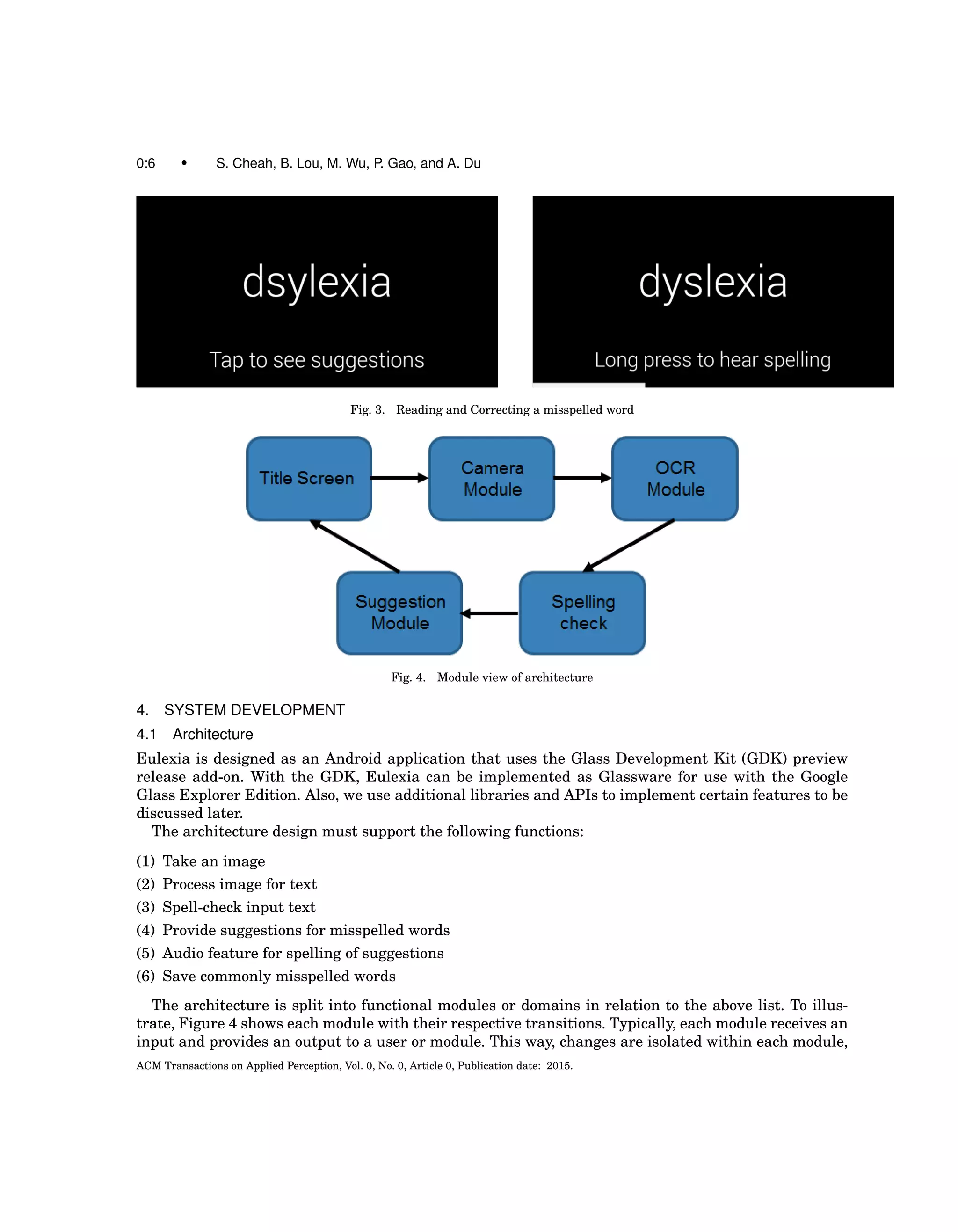

allowing for easier debugging efforts. The transitions between each module is aided with the use of the

GDK, allowing us to create transitions and read gestures from the user.

4.2 Technology used

4.2.1 Google Glass Explorer Edition. The application is created for use with the Google Glass Ex-

plorer Edition. We note that the Google glass allows us to work with its audio speaker, gesture com-

mands, and camera. These all will play a role in incorporating features for our Glassware.

The gesture commands are they key feature for the user to interact with our application. The user

would be prompted for certain gestures to navigate in the application. As for the audio speaker, it

allows us to provide a dictation aid when providing suggestions.

The camera on the Google Glass has some limiting features we have to consider when implementing

Eulexia. First, the camera takes pictures up to 5 megapixels uncompressed. This will affect the time it

will take to process the image during the OCR (Optical Character Recognition) process. Compression

can help speed up the processing times, but leads to degradation of quality and accuracy of results.

With this in mind, we consider accuracy as a top priority for the application when communicating

results to the user. No amount of compression is utilized, leading to the best possible image quality

at the cost of processing times. On a different note, users may have difficulty positioning the camera

when taking a picture of text. To counteract the problem with the camera capturing a small range of

the users vision, we provide a live camera preview feature. We make this feature readily available,

but optional in order to alleviate possible overheating problems. Additionally, the camera hardware is

limited to a single focus, leading to some low quality text in images. Nevertheless, before processing

the image with OCR, we provide an image preview of the image taken for the user to verify that the

picture taken contains the text they want to spell check.

4.2.2 OCR Service. An accurate OCR service is necessary to provide precise results for spell check-

ing. If this feature mistakenly extracts text from images, a spell checker would lose its ability to help

and inform the user. We decided upon the OCR online API from a9t9 (Autonomous Technology). This

online API is basically an extension of the Microsoft OCR library, which is easier to use and gives bet-

ter results than Tesseract, previously our first choice for an OCR library [Technology 2015]. We also

consider other services, but research into other OCR online services yielded lesser results most of the

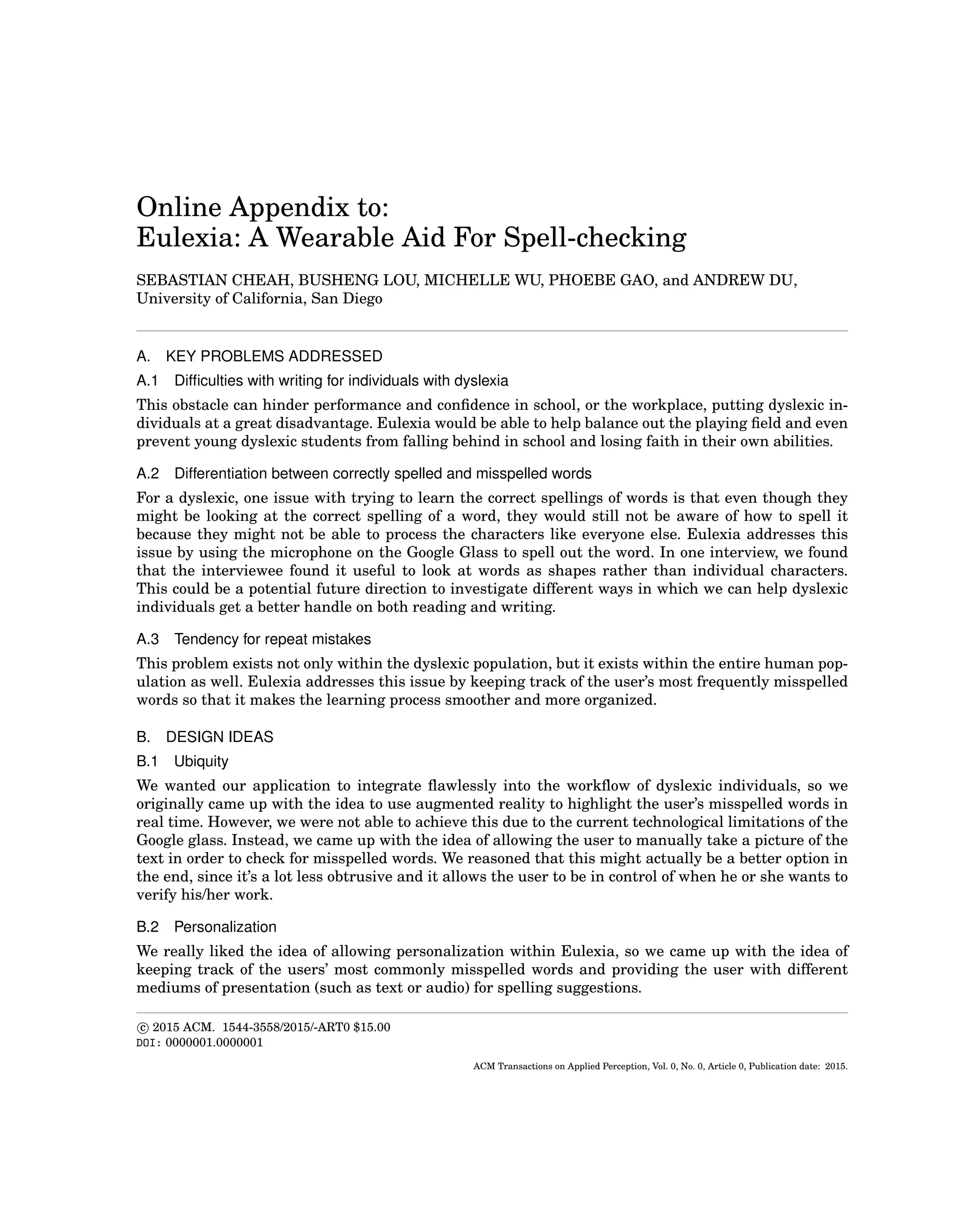

time. In our research, we note results comparing many services, shown in Figure 5. Comparison be-

tween Tesseract Online (a variant of Tesseract) and Abby Cloud SDK (which is similar to a9t9’s Online

OCR) show a clear difference in accuracy. Results were based on the Levenshtein distance between

ACM Transactions on Applied Perception, Vol. 0, No. 0, Article 0, Publication date: 2015.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02321965-523e-41d1-8eb3-067f16de2115-160307211847/75/Eulexia-A-Wearable-Aid-For-Spell-checking-7-2048.jpg)

![0:8 • S. Cheah, B. Lou, M. Wu, P. Gao, and A. Du

Table I. Edit distance calculation

parameters

Parameter Cost

Remove a character 95

Insert a character 95

Swap adjoining characters 90

Substituting a character 100

Change case of a character 10

Suggestion Cost Threshold 140

Fig. 6. Application Flow Simplified

Fig. 7. Capturing an image with the viewfinder

output and truth input strings (this will be discussed later). Our test cases involve a low quality image

of text (ideally close to a low quality scan of a text document), and we prefer an OCR solution capable of

providing accurate results. Despite this, we note that there is a limitation with current OCR solutions

used with images taken from a camera, as they do not consistently provide accurate results. Also to

consider, since this is an online service, it may take some time to upload the image using the Internet.

To alleviate these processing times, loading bars are used to provide feedback to the user.

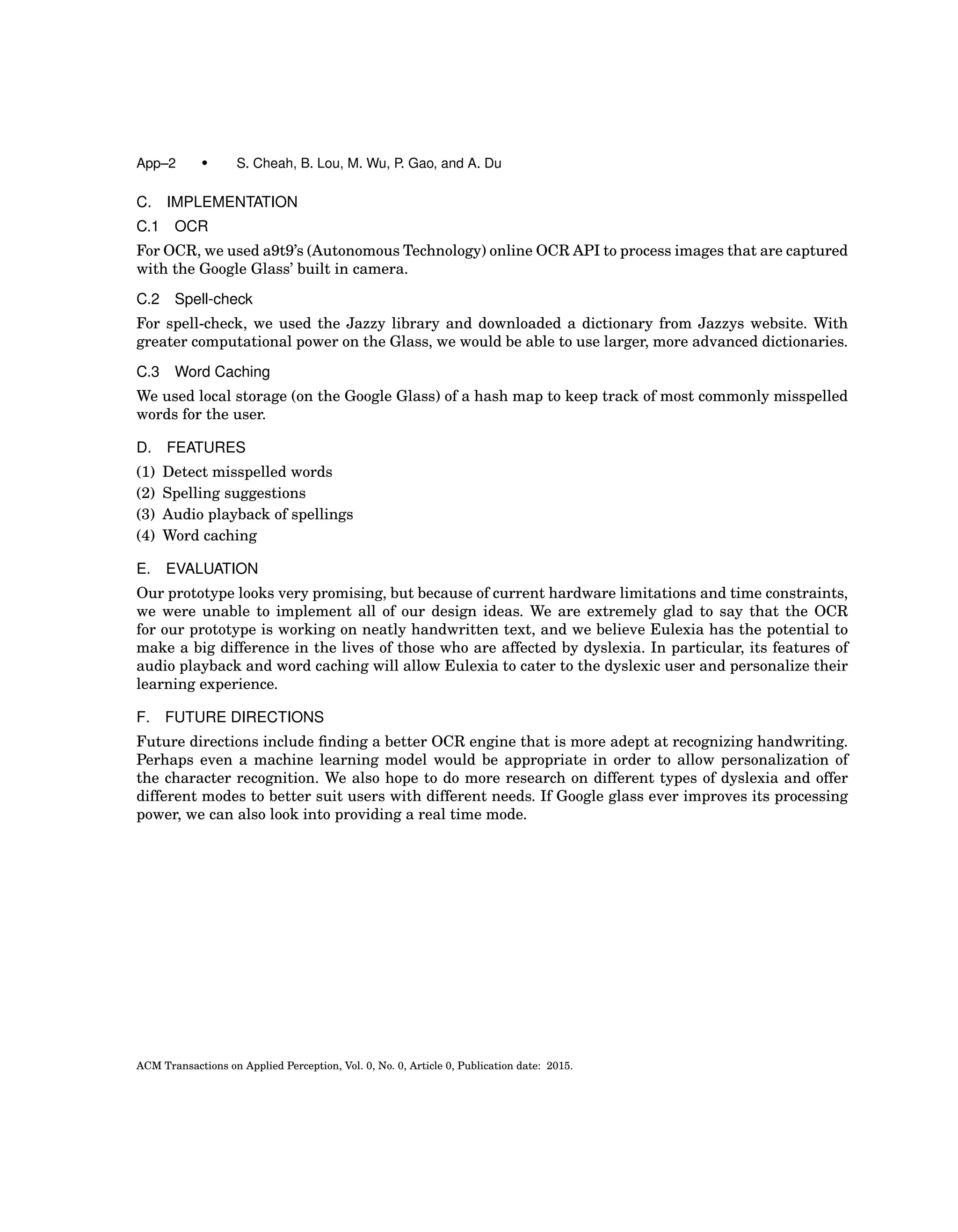

4.2.3 Spell-check and Suggestions. For spell checking and suggestions, the Jazzy library is used.

Jazzy is an open source spell checker, providing a set of APIs relevant to our project. Basically, Jazzy

takes as input a dictionary or word list with one word per line, to populate a dictionary hash map.

We check against this hash map when determining whether or not a word is misspelled. As for sug-

gestions, the Jazzy library utilizes the suggestion strategy from Aspell (the standard spell checker for

the GNU operating system). Basically, suggestions are based on thresholding an edit distance value

based on a variant of the Levenshtein distance between two strings [Atkinson 2004]. The edit distance

between two strings is defined as the number of operations, involving interchanging two adjacent let-

ters, changing one letter, deleting a letter, or adding a letter, to transform one string into the other.

To further clarify the default edit distance algorithm, please refer to Table I. Each operation has a

cost associated with it. Suggestions are generated and threshold-ed with costs less than the indicated

threshold value. The default configuration follows closely with Aspells suggestion strategy of returning

sounds-like suggestions up to two edit distances away.

ACM Transactions on Applied Perception, Vol. 0, No. 0, Article 0, Publication date: 2015.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/02321965-523e-41d1-8eb3-067f16de2115-160307211847/75/Eulexia-A-Wearable-Aid-For-Spell-checking-8-2048.jpg)