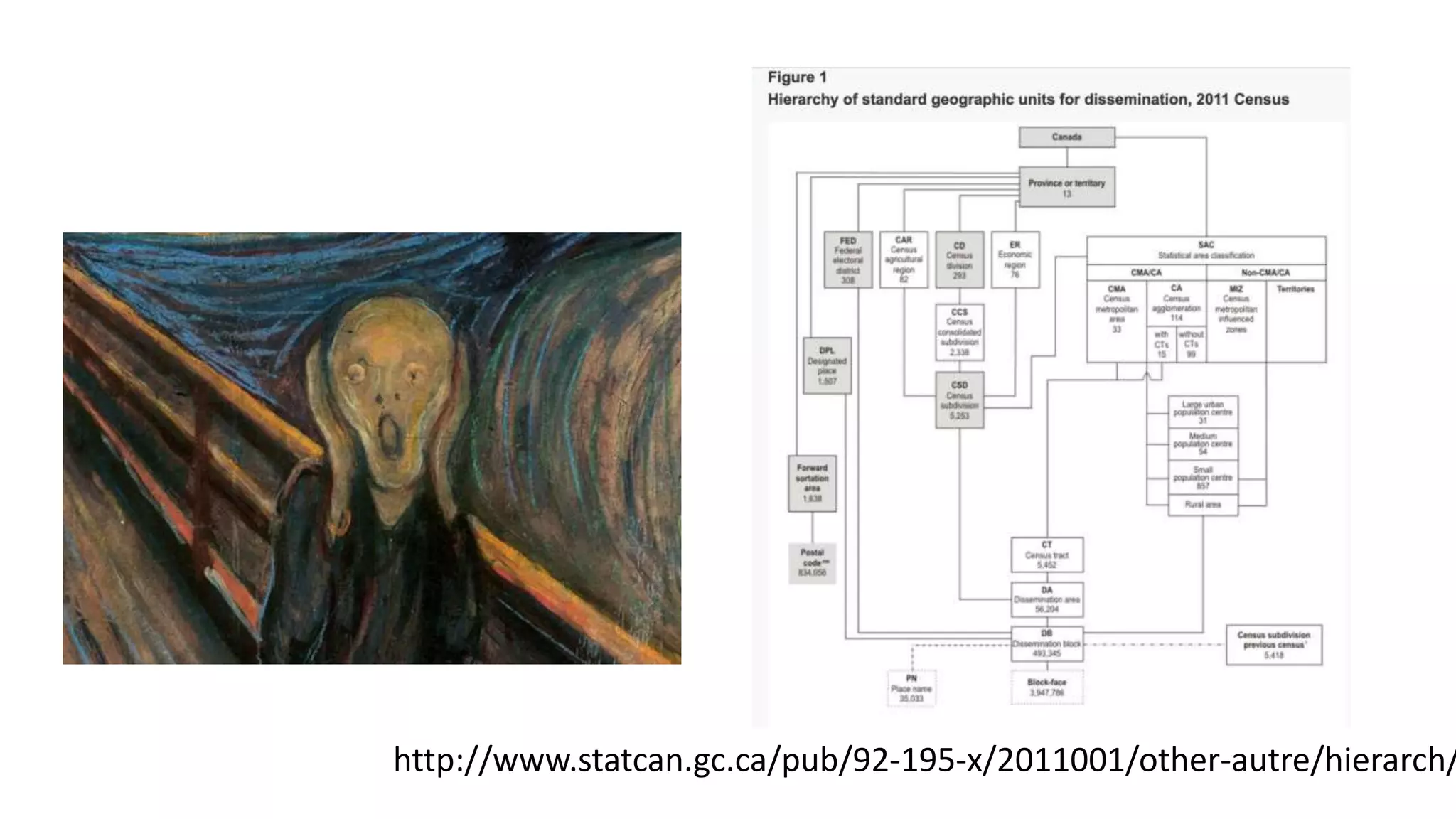

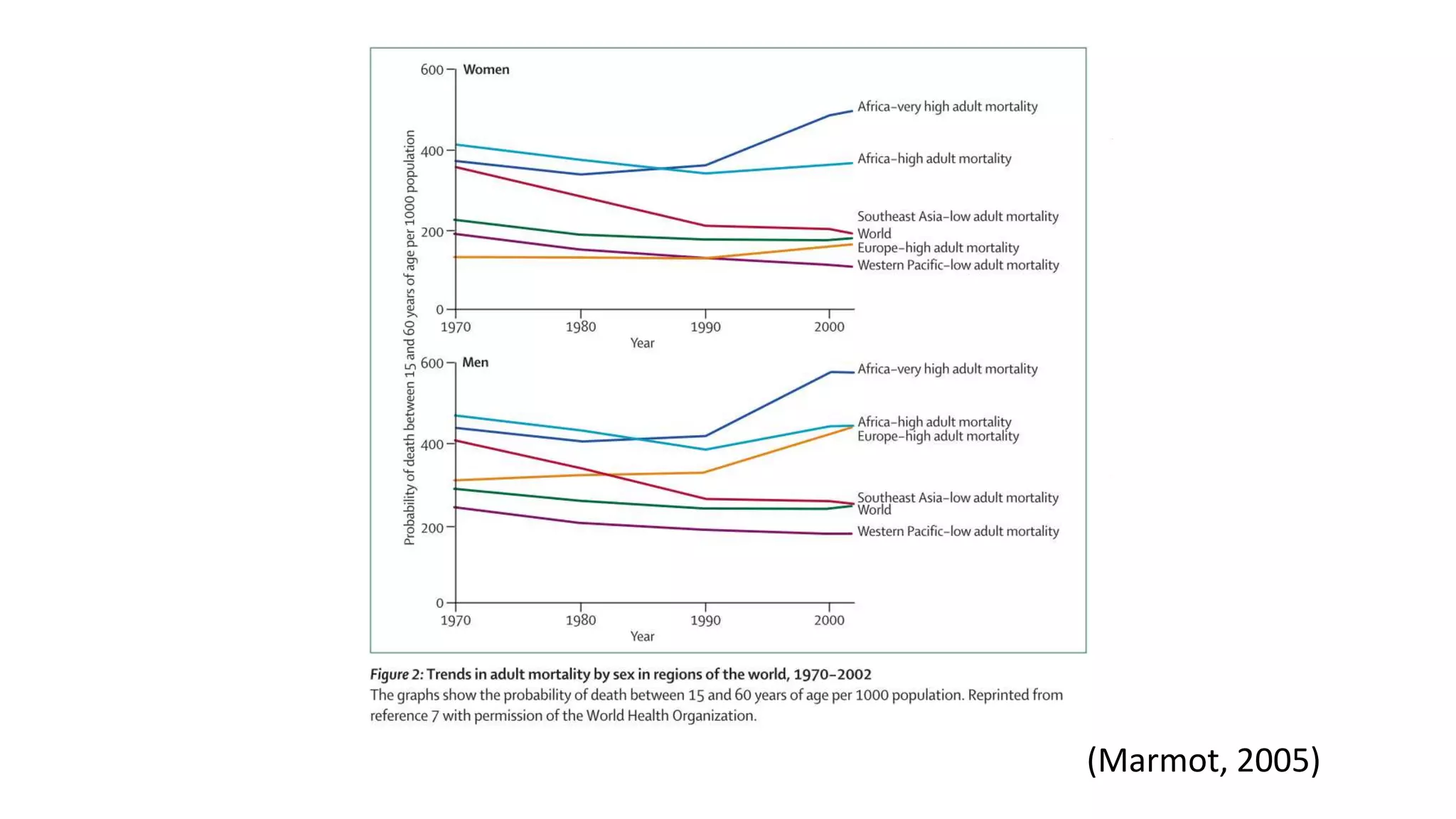

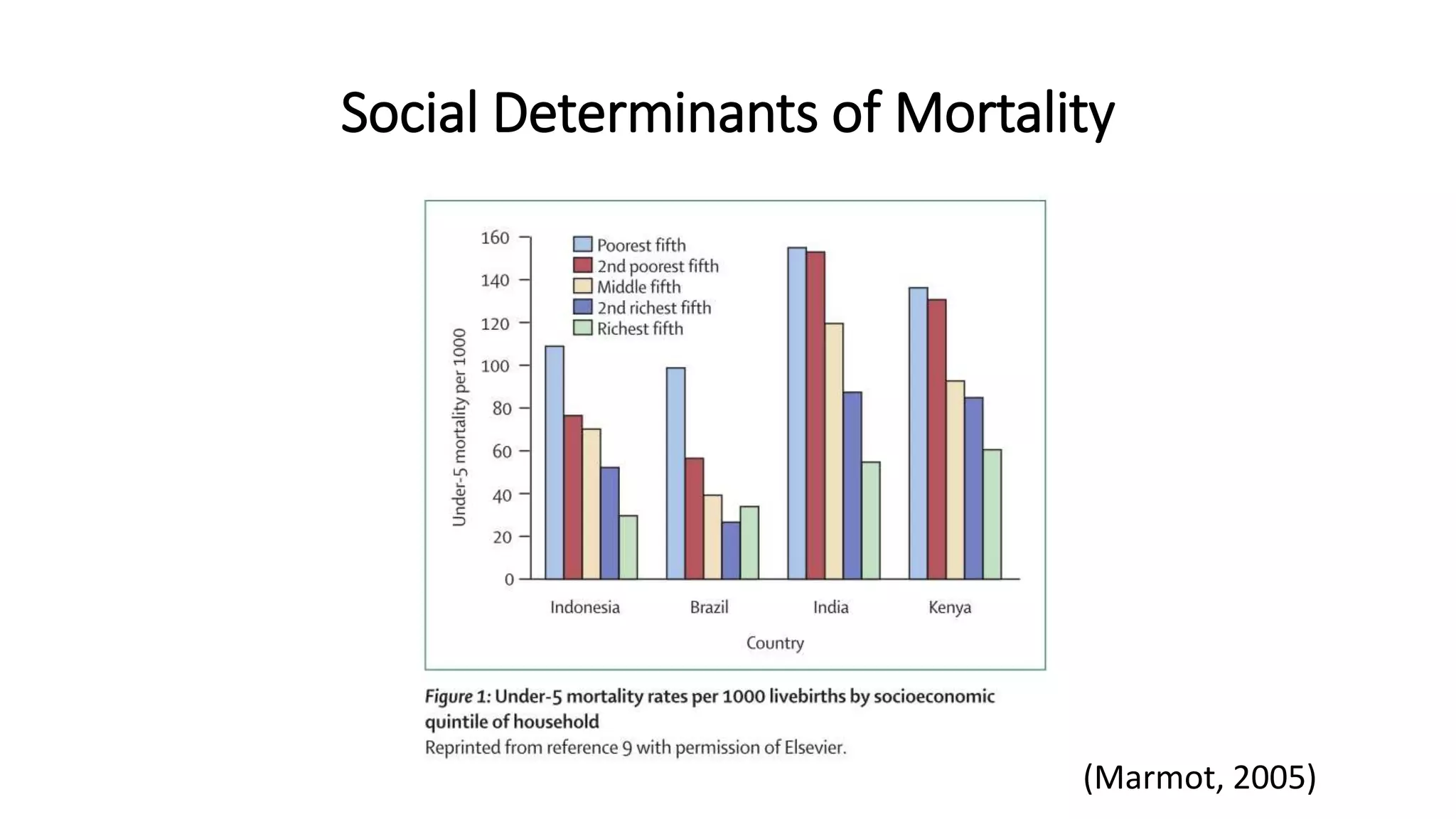

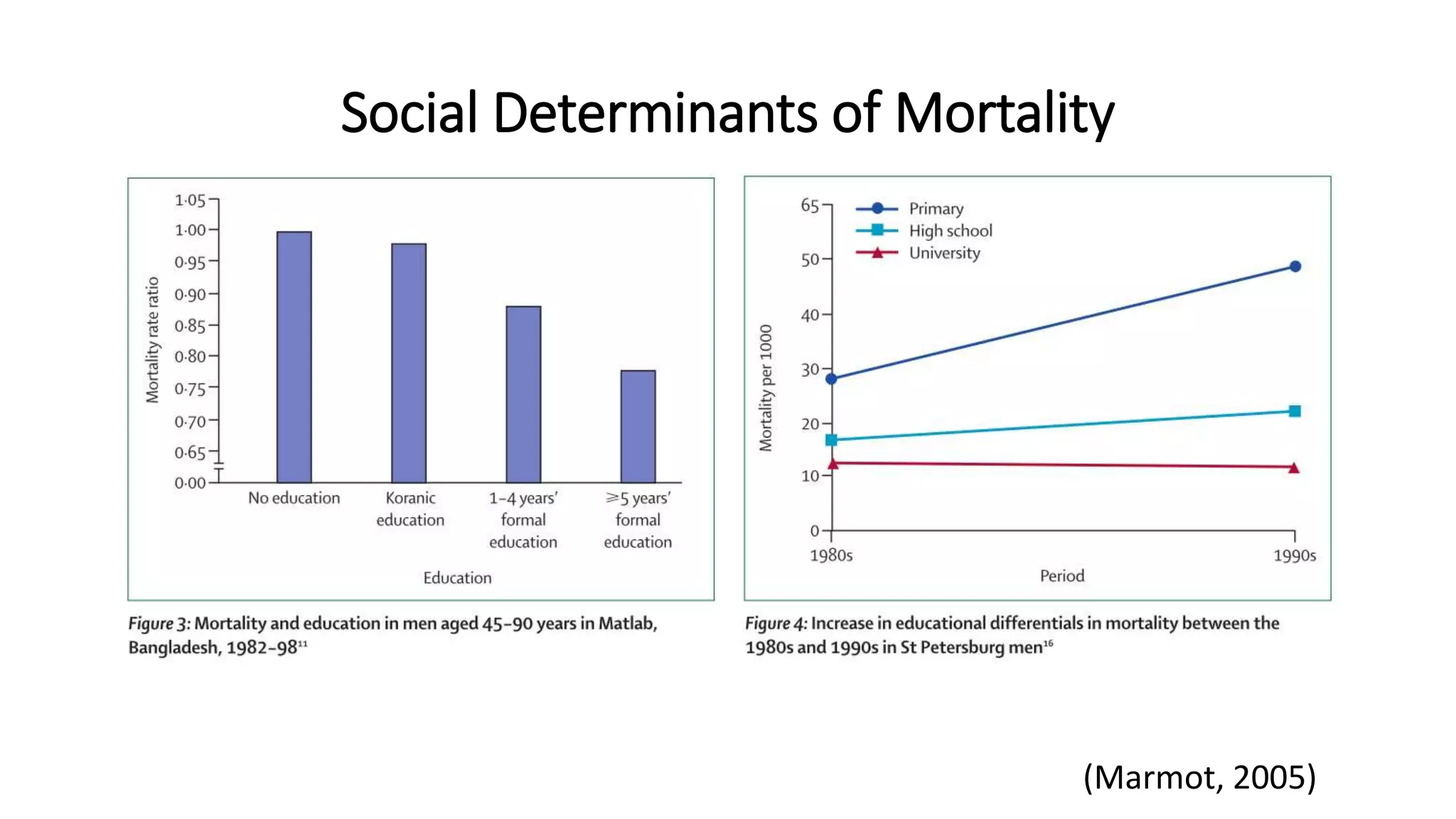

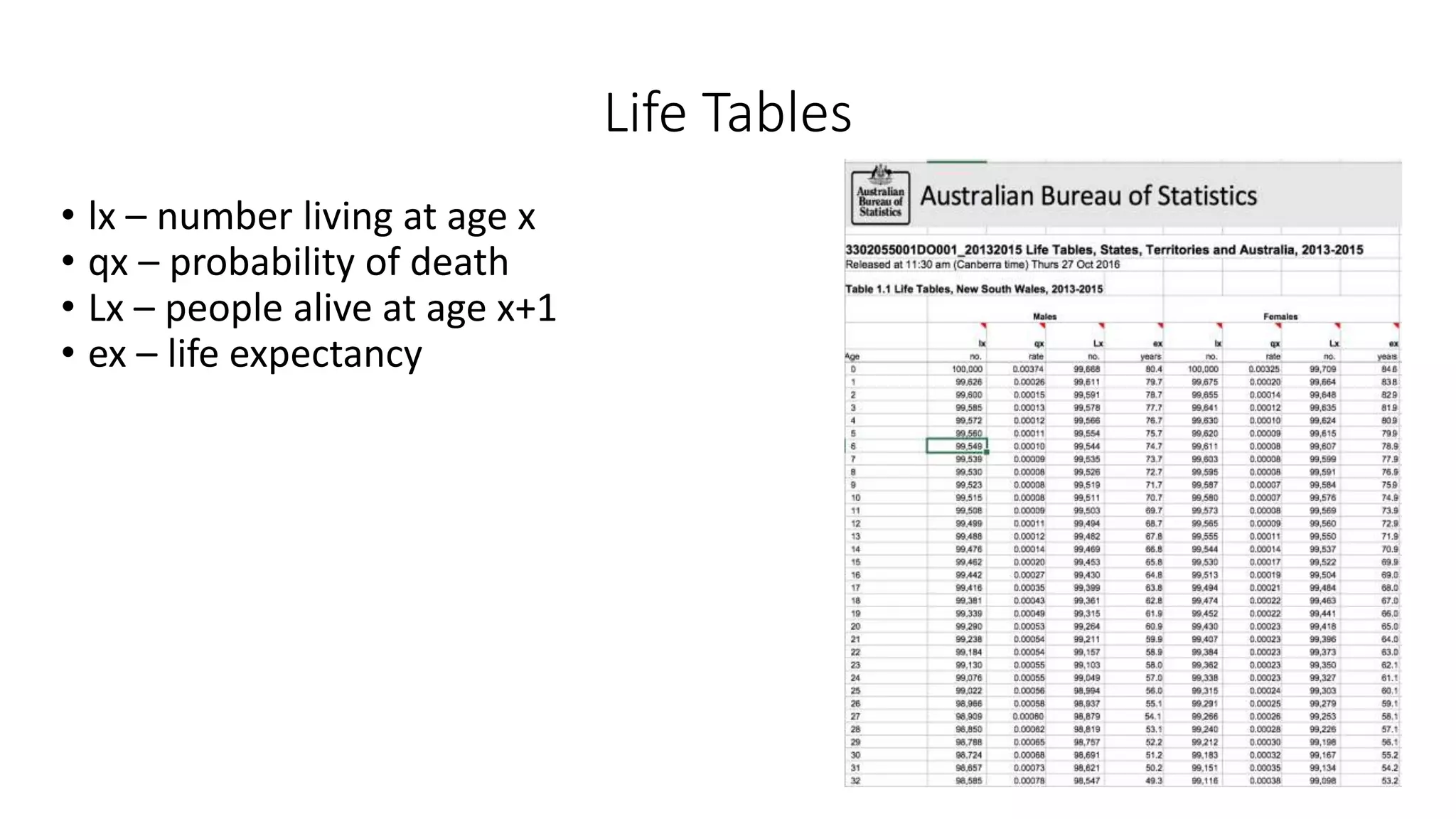

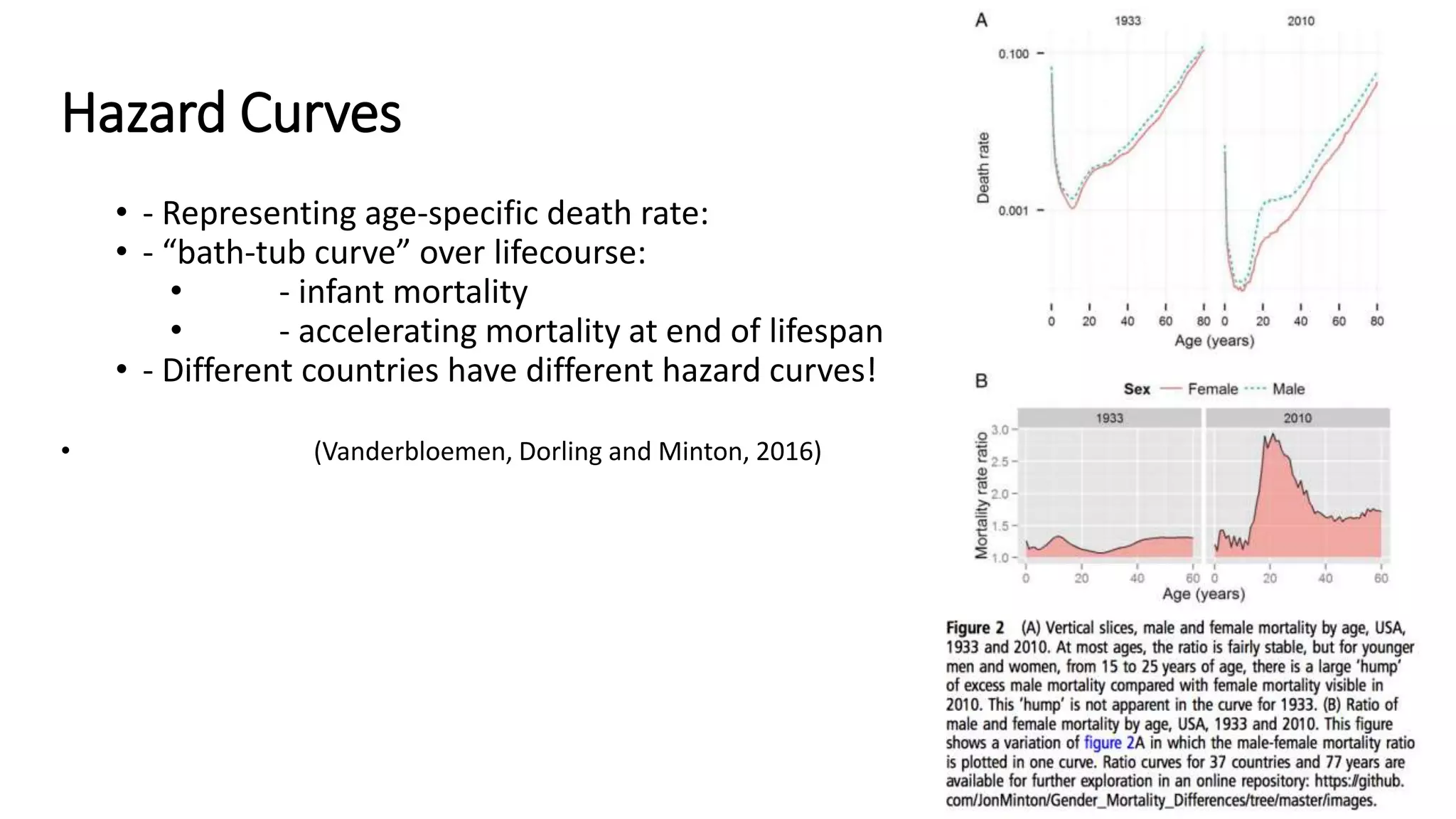

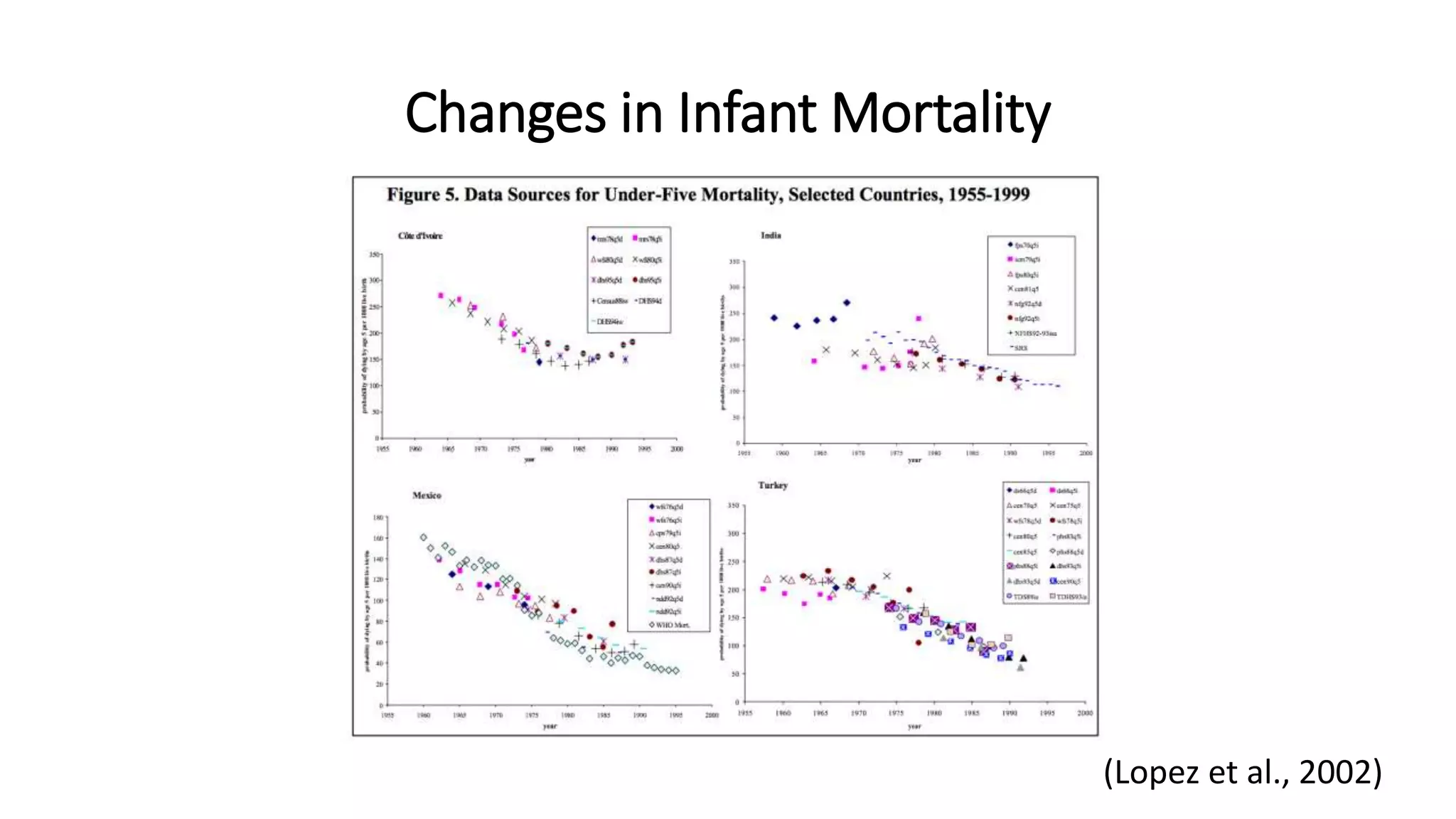

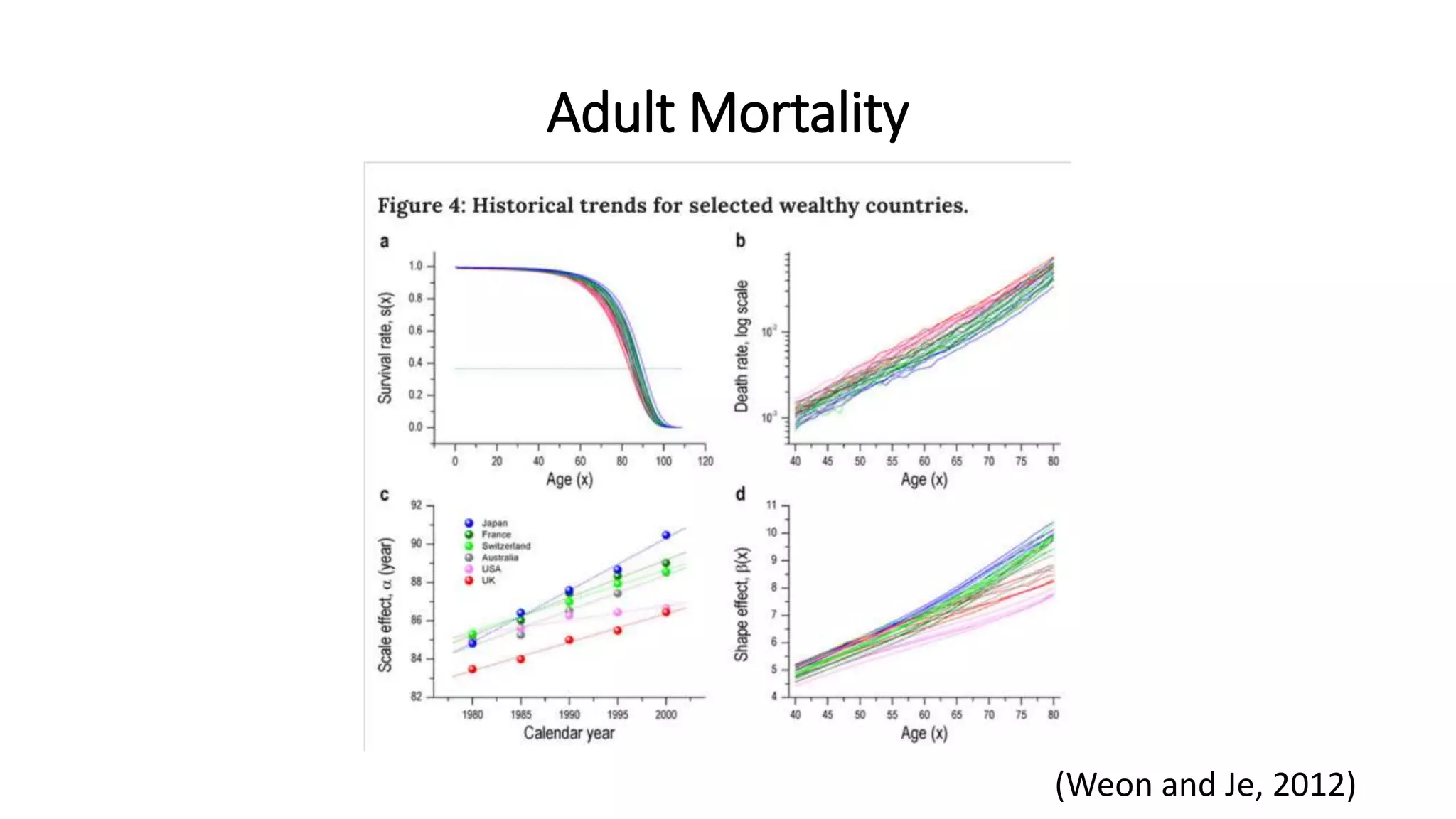

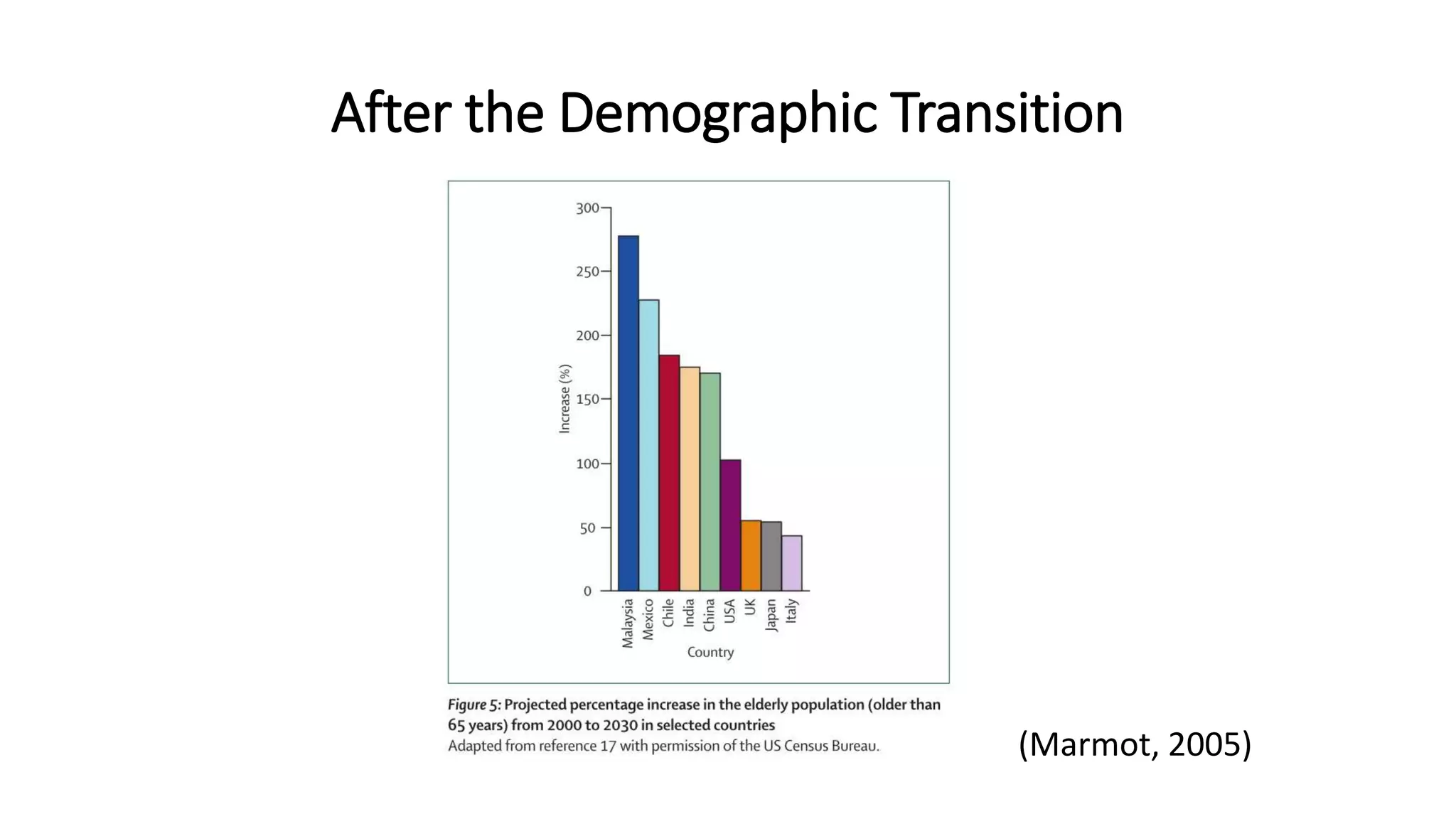

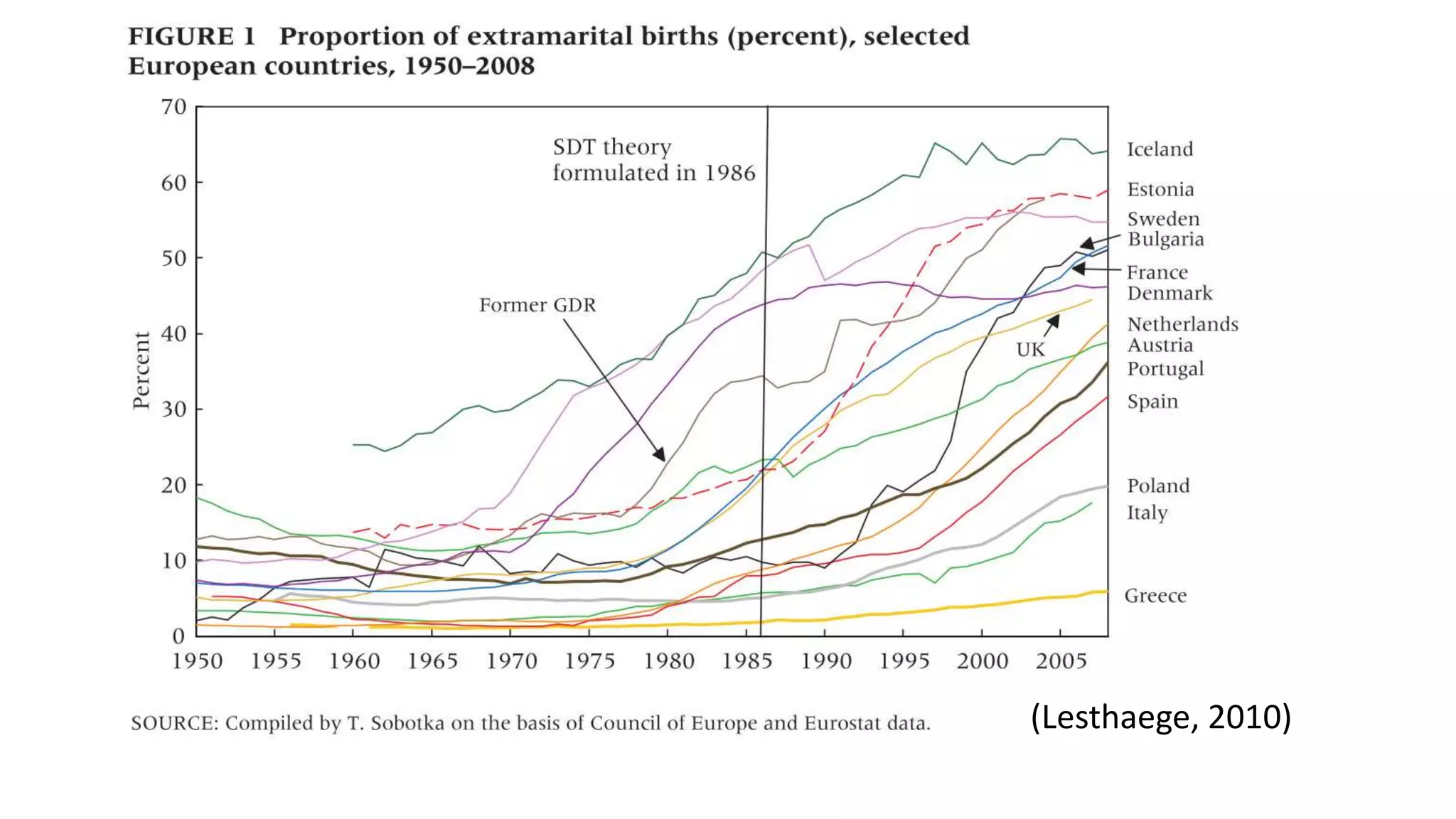

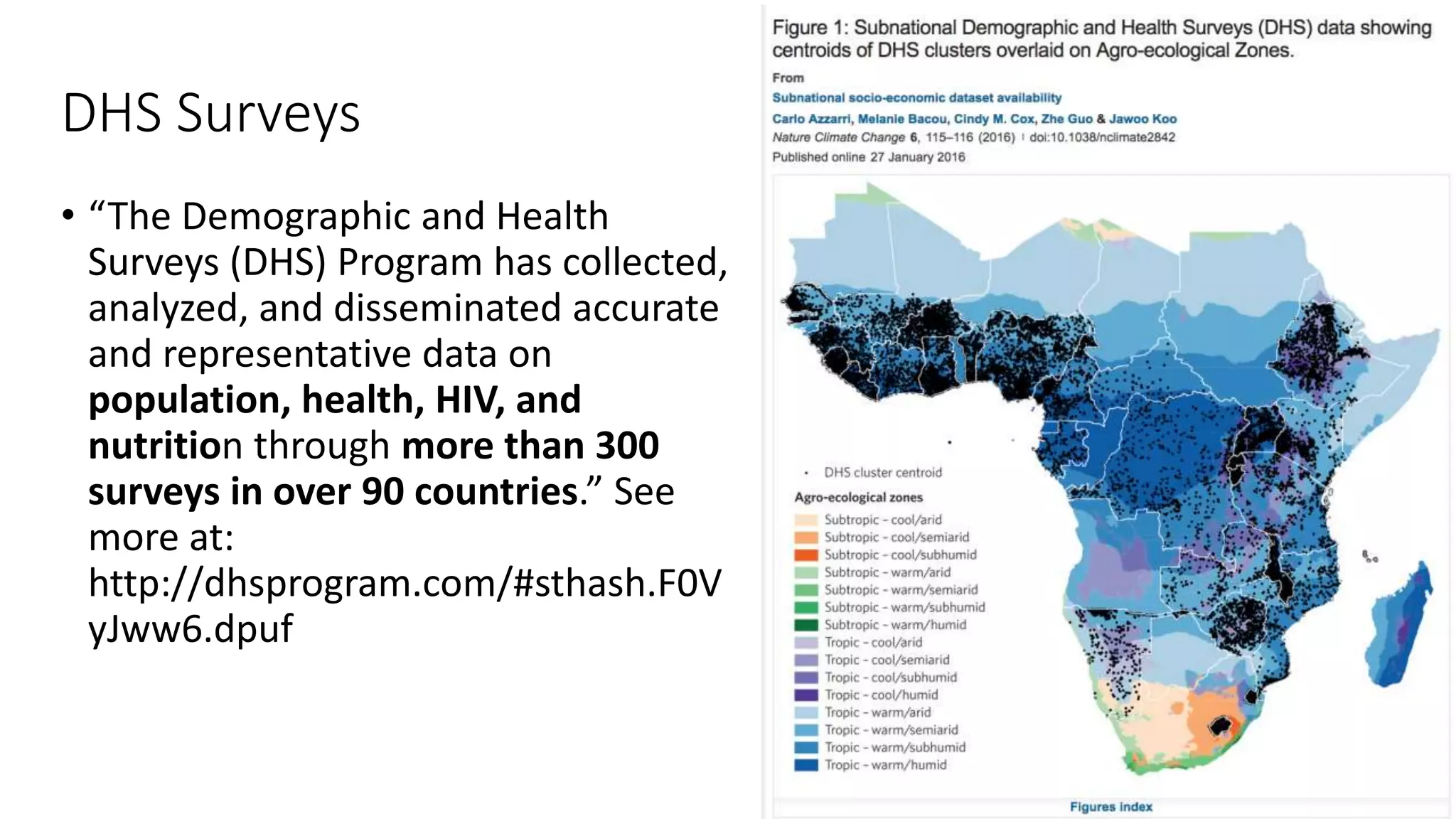

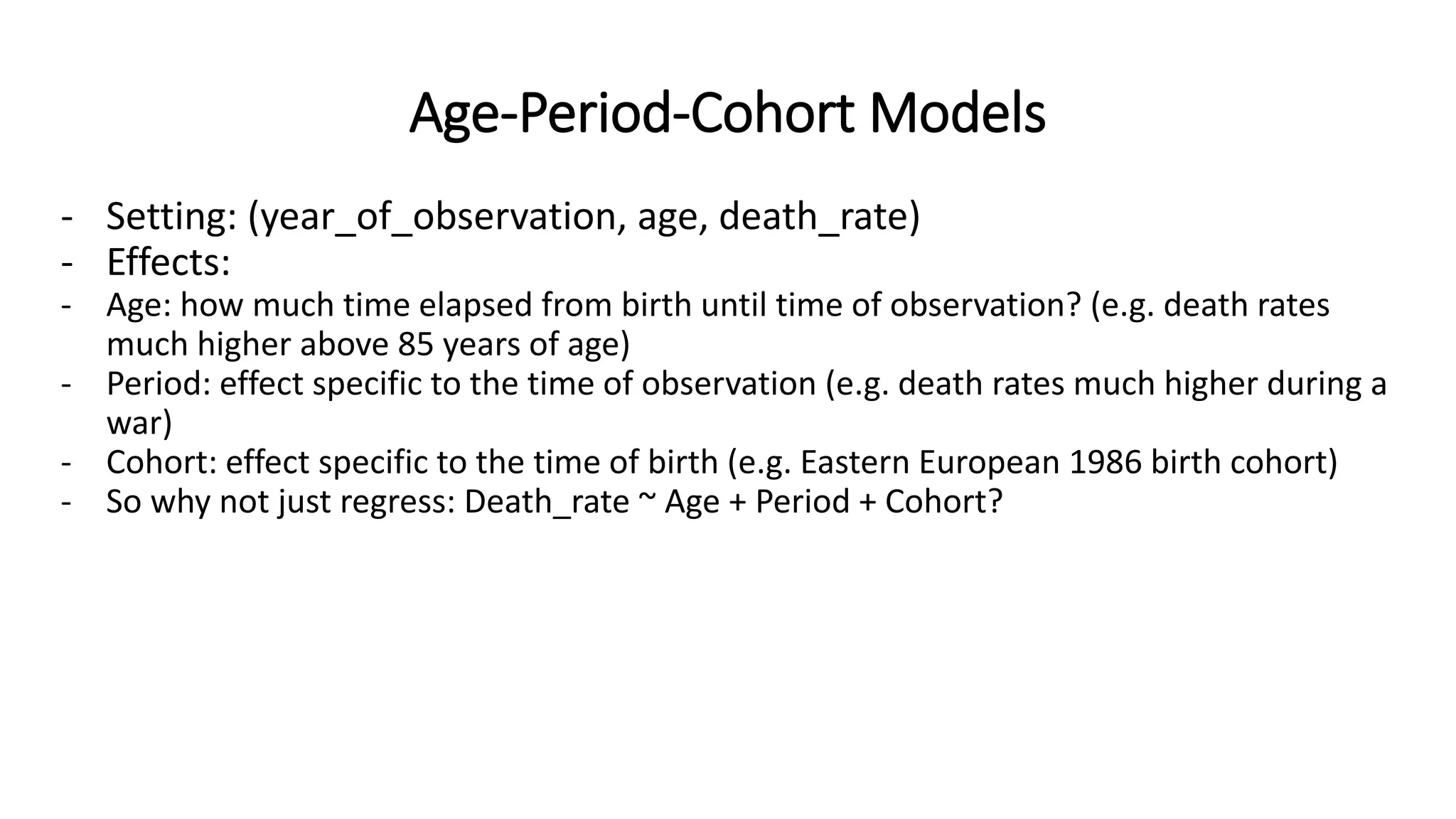

The document discusses digital demography, focusing on traditional demographic methods involving population equations and essential demographic questions like fertility, mortality, and migration. It addresses the impact of demographic transitions on population structures and explores measurement challenges in migration and data collection, including censuses and surveys. Additionally, it highlights various modeling approaches to analyze demographic data, incorporating methods like survival analysis and age-period-cohort modeling.

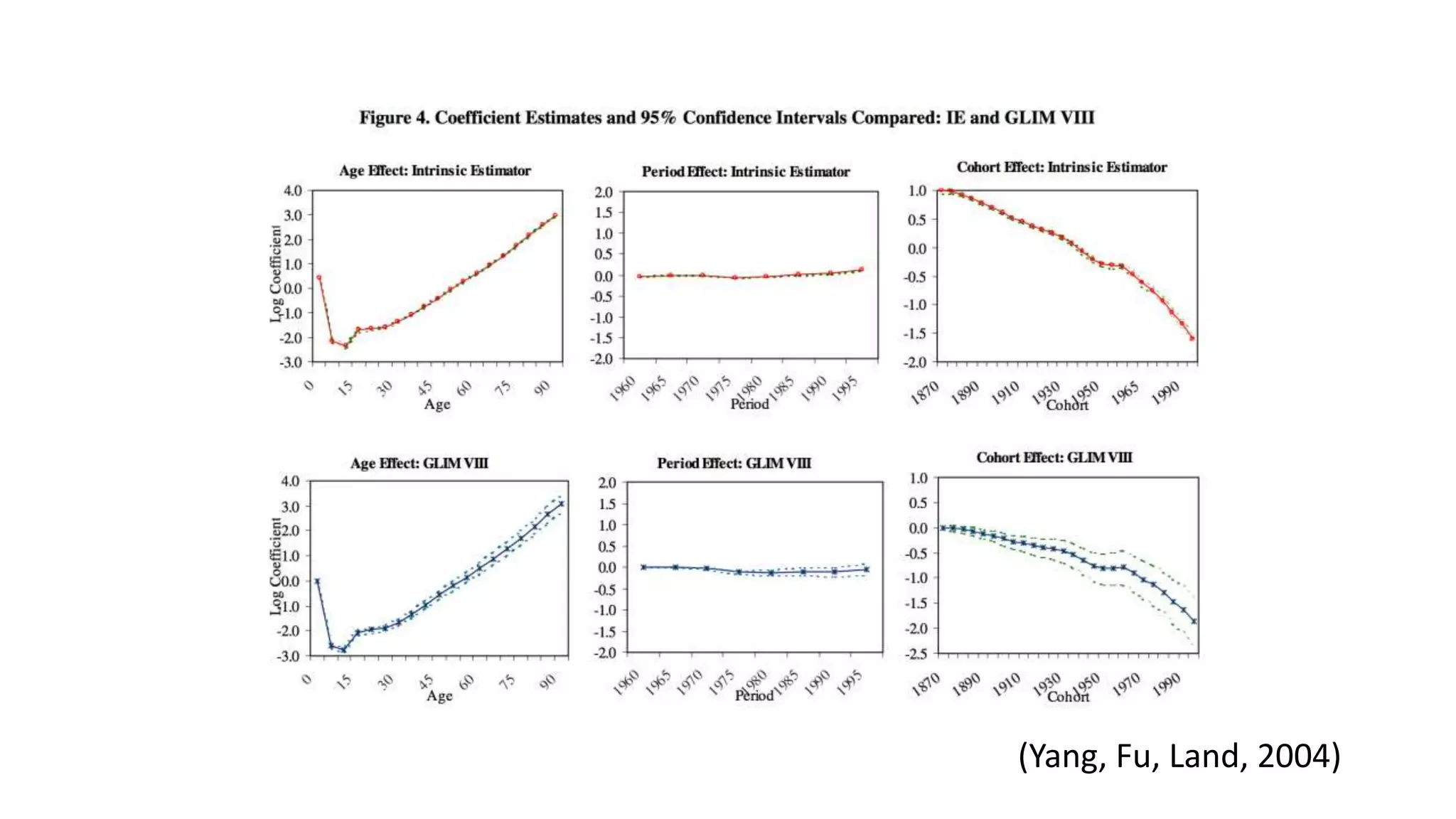

![Age-Period-Cohort Models

- Yang, Fu and Land (2004): “the identification problem [in APC analysis] still

remains largely unsolved.”

- Two solutions:

- GLM models, w/ either logarithmic or logit link function. Can be reparameterized as

fixed effects models.

- Intrinsic estimator based on SVD

- For microdata, can use mixed effects(Yang and Land, 2006)!

- Hacky solution: lme4: death_rate ~ age + age^2 + (1 | period) + (1 | cohort)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitaldemographyparti-170514024227/75/Digital-Demography-WWW-17-Tutorial-Part-I-40-2048.jpg)