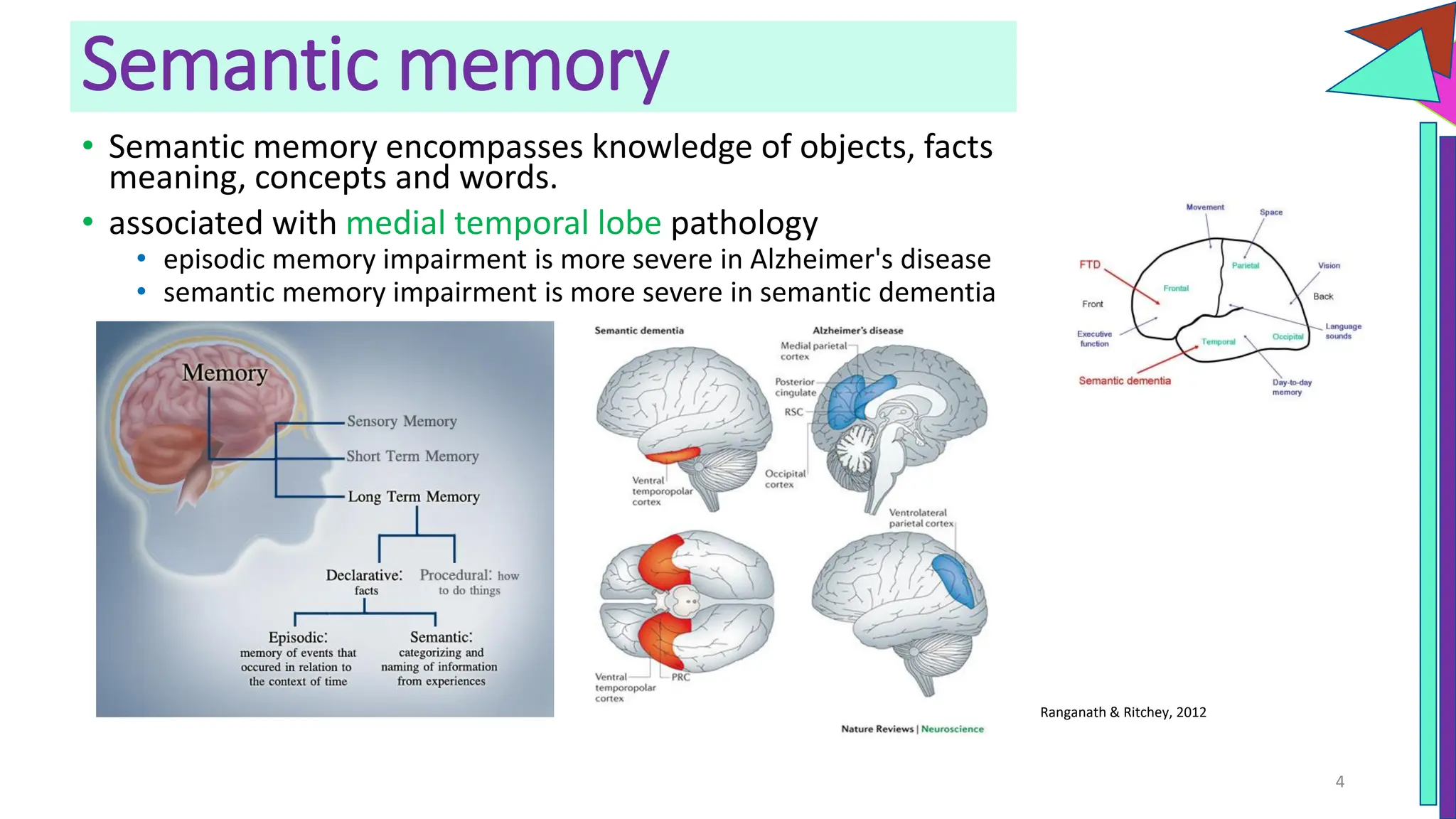

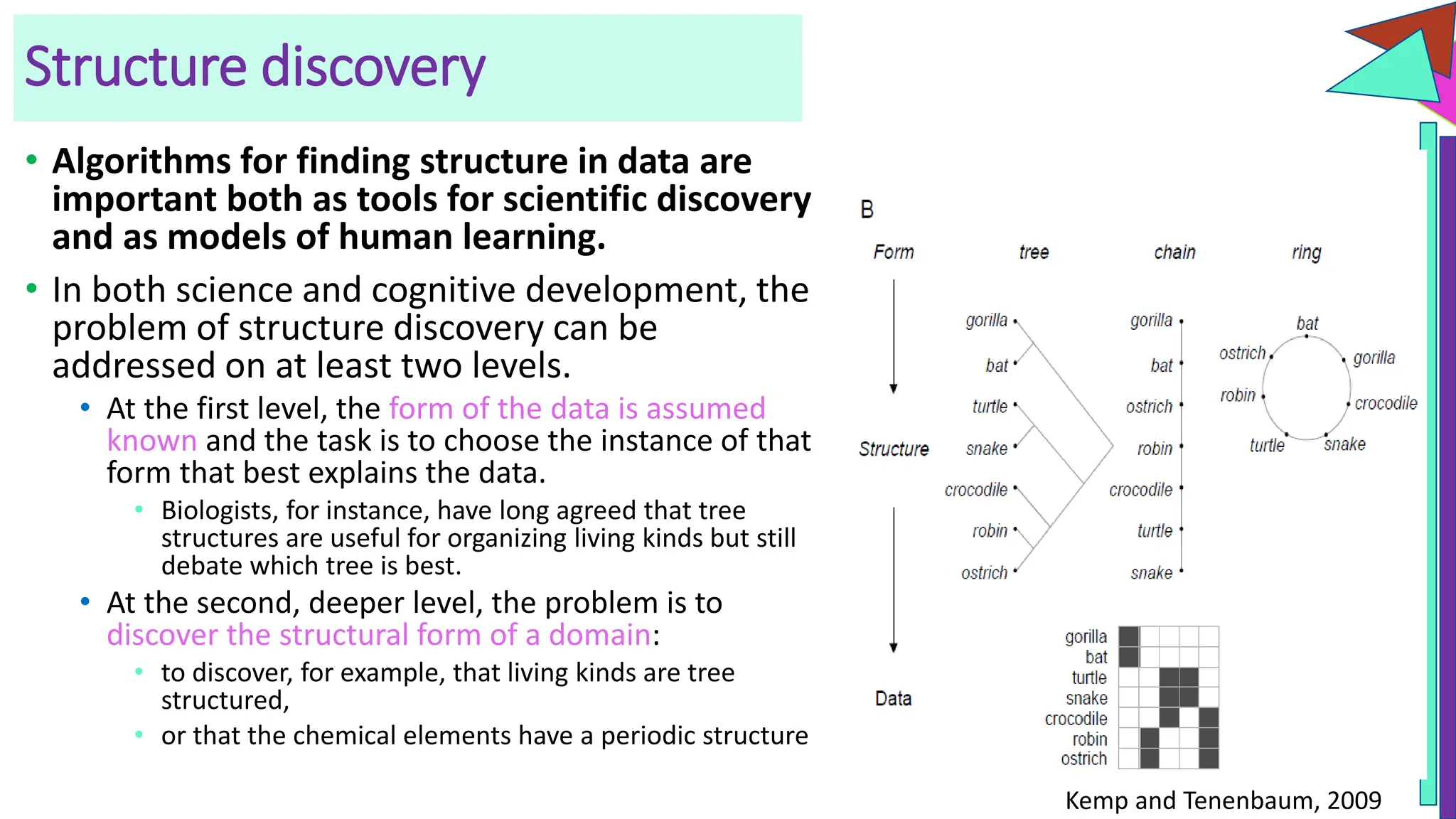

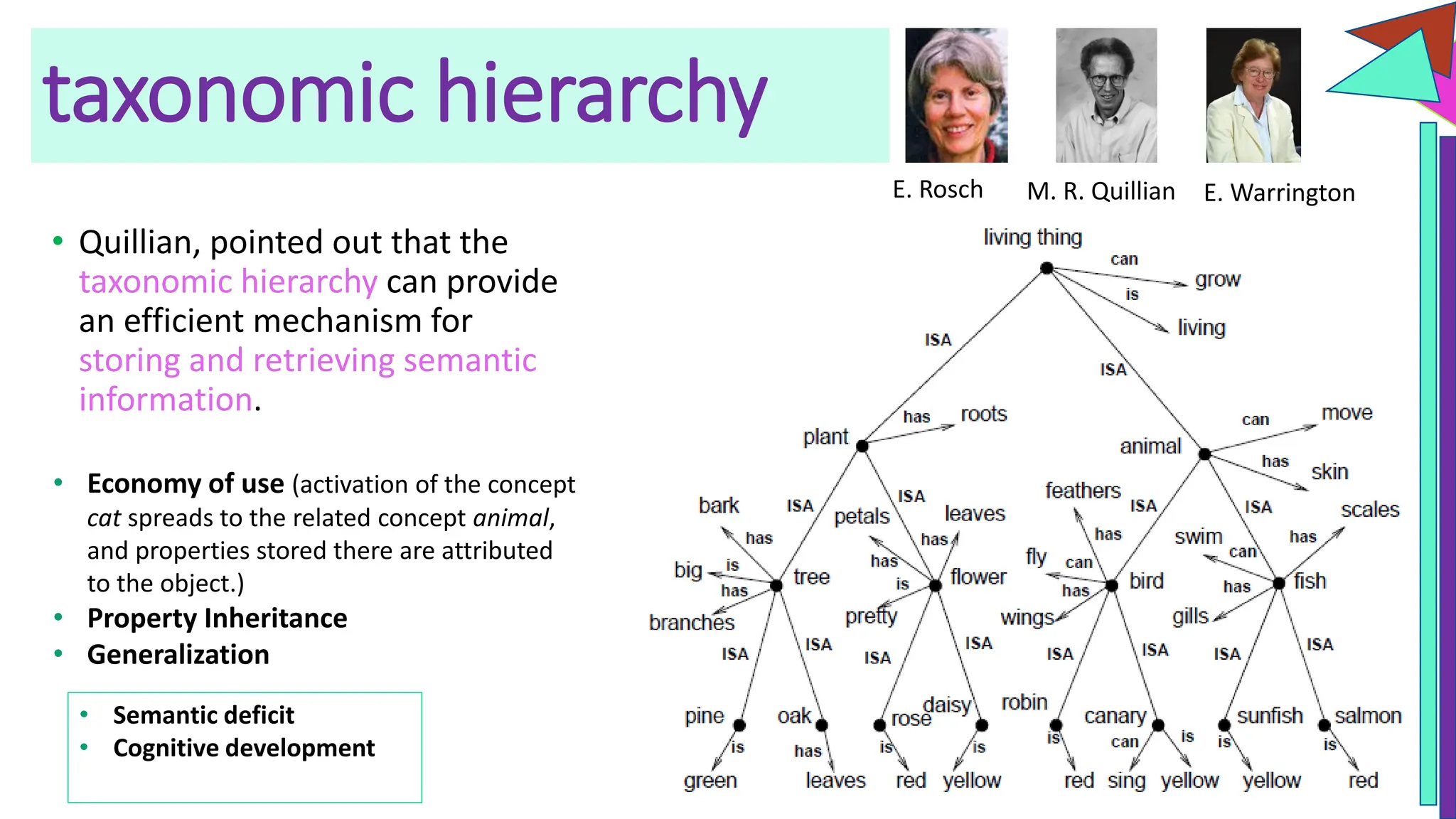

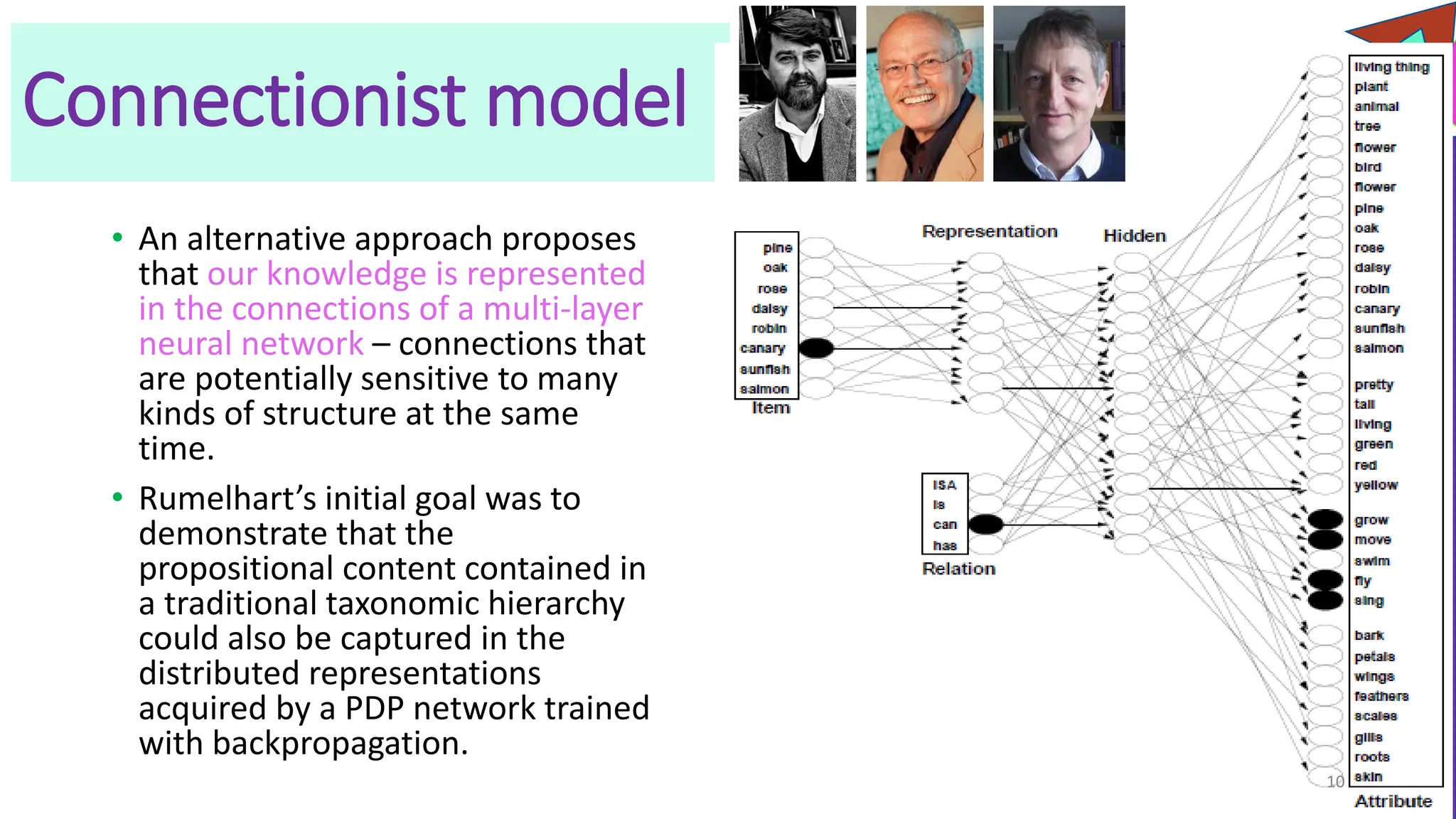

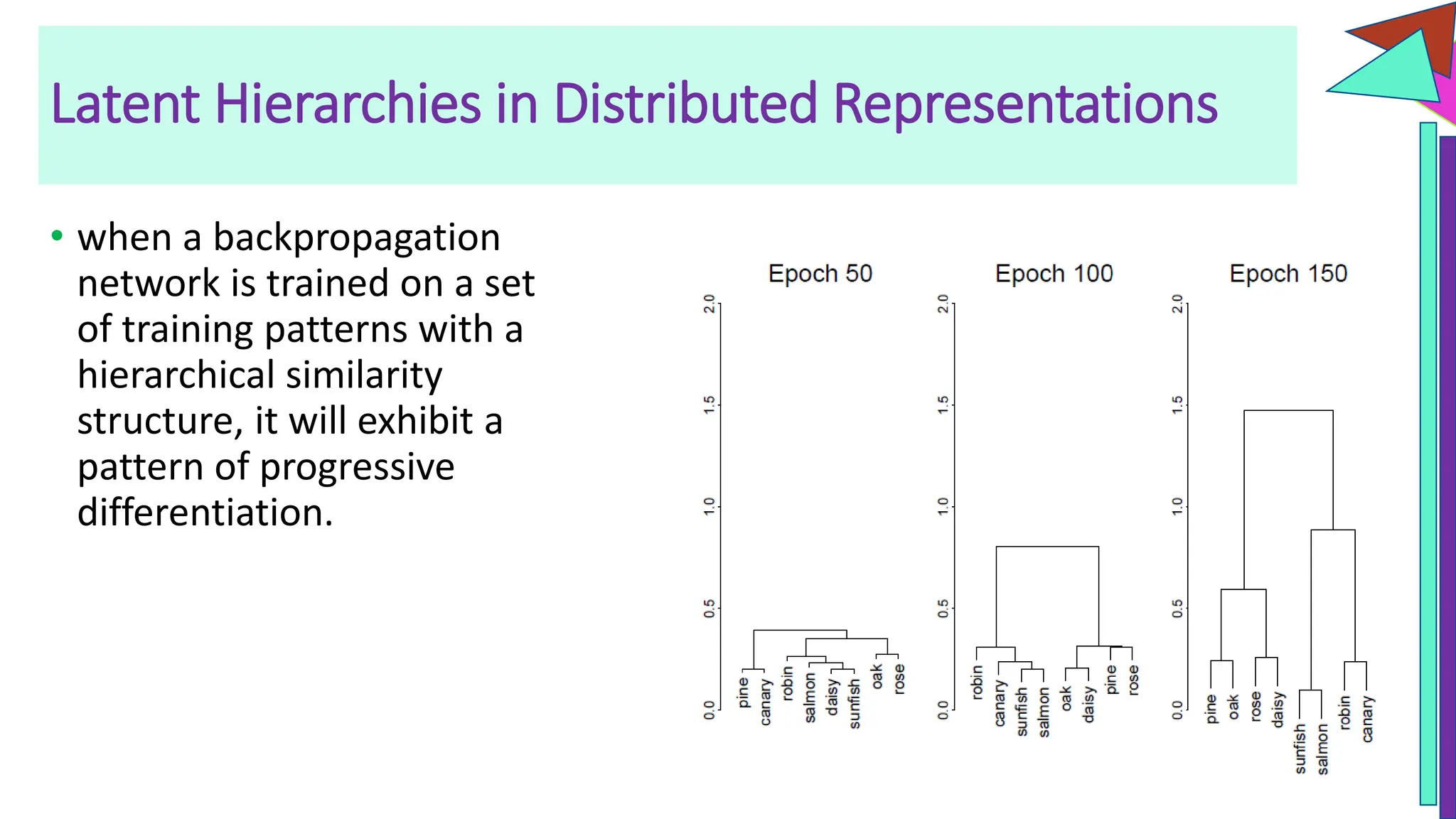

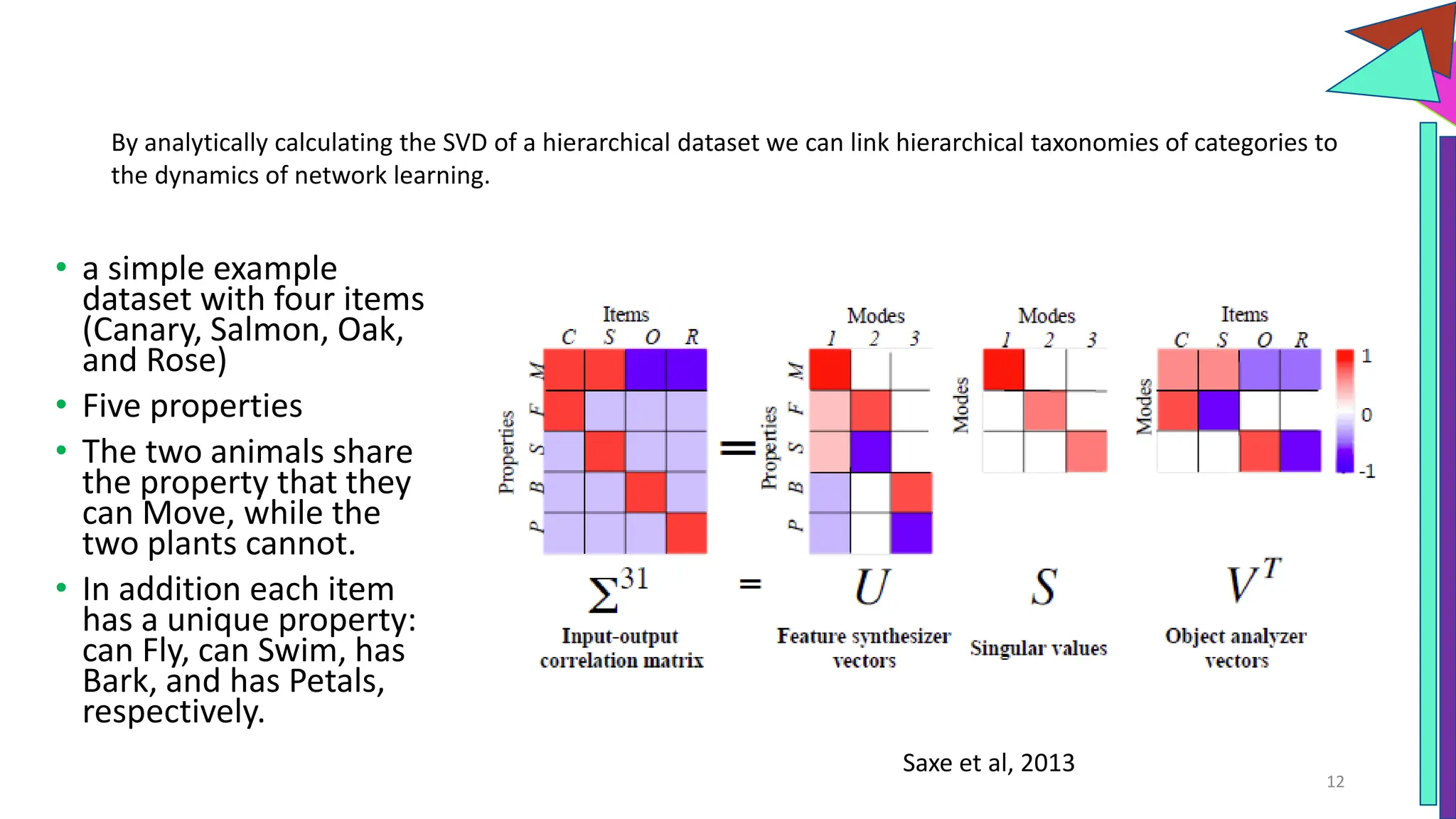

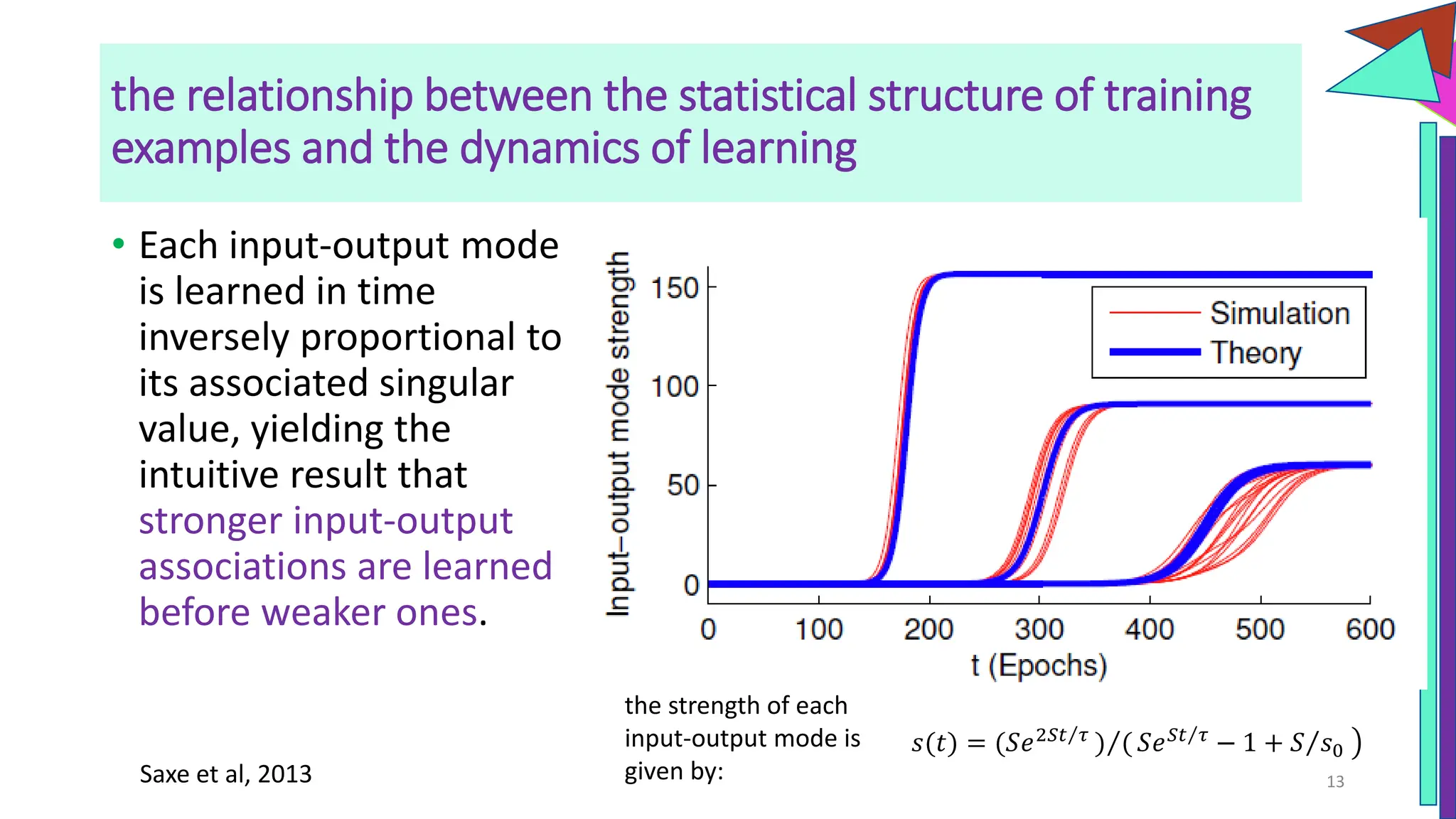

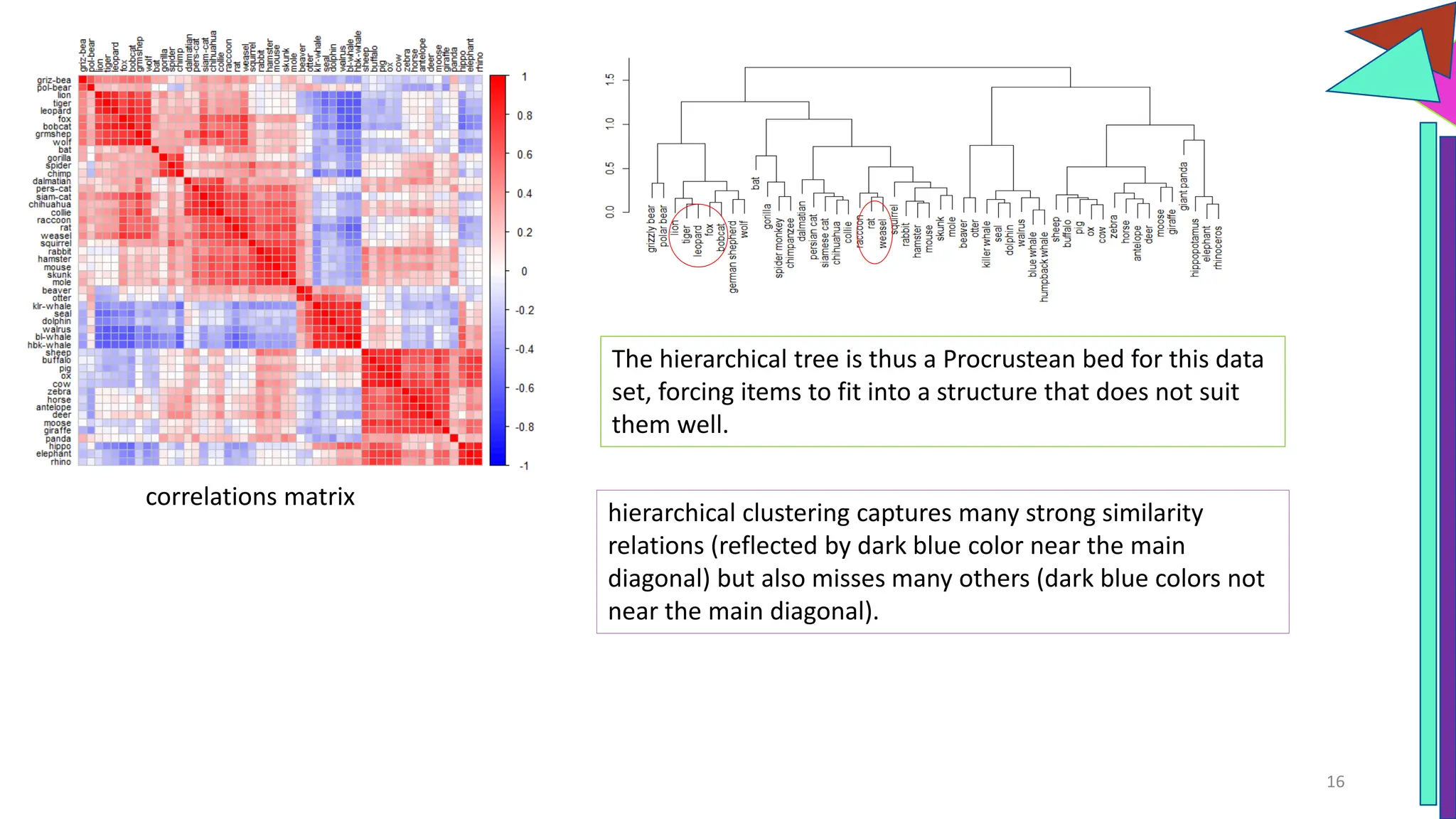

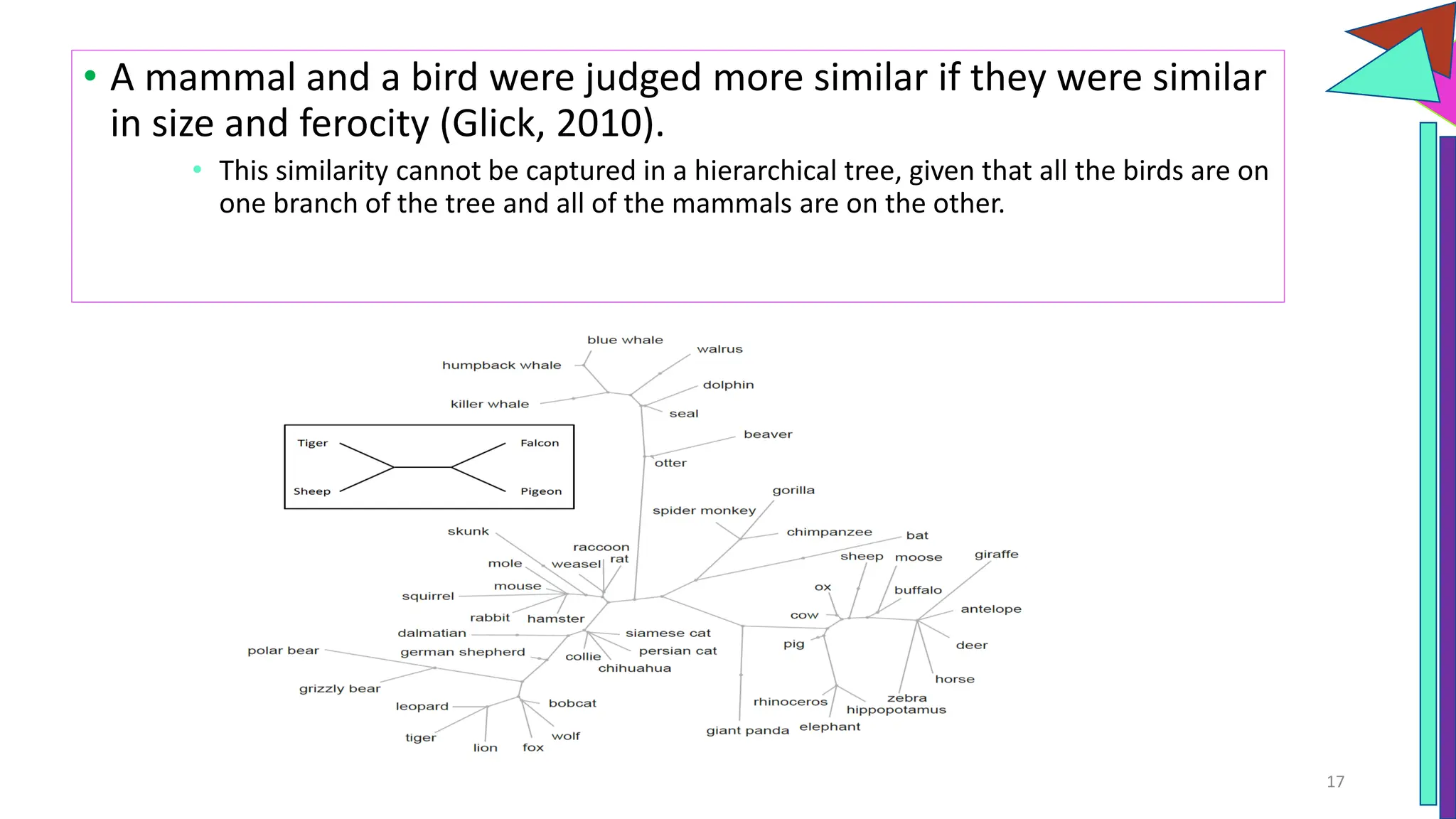

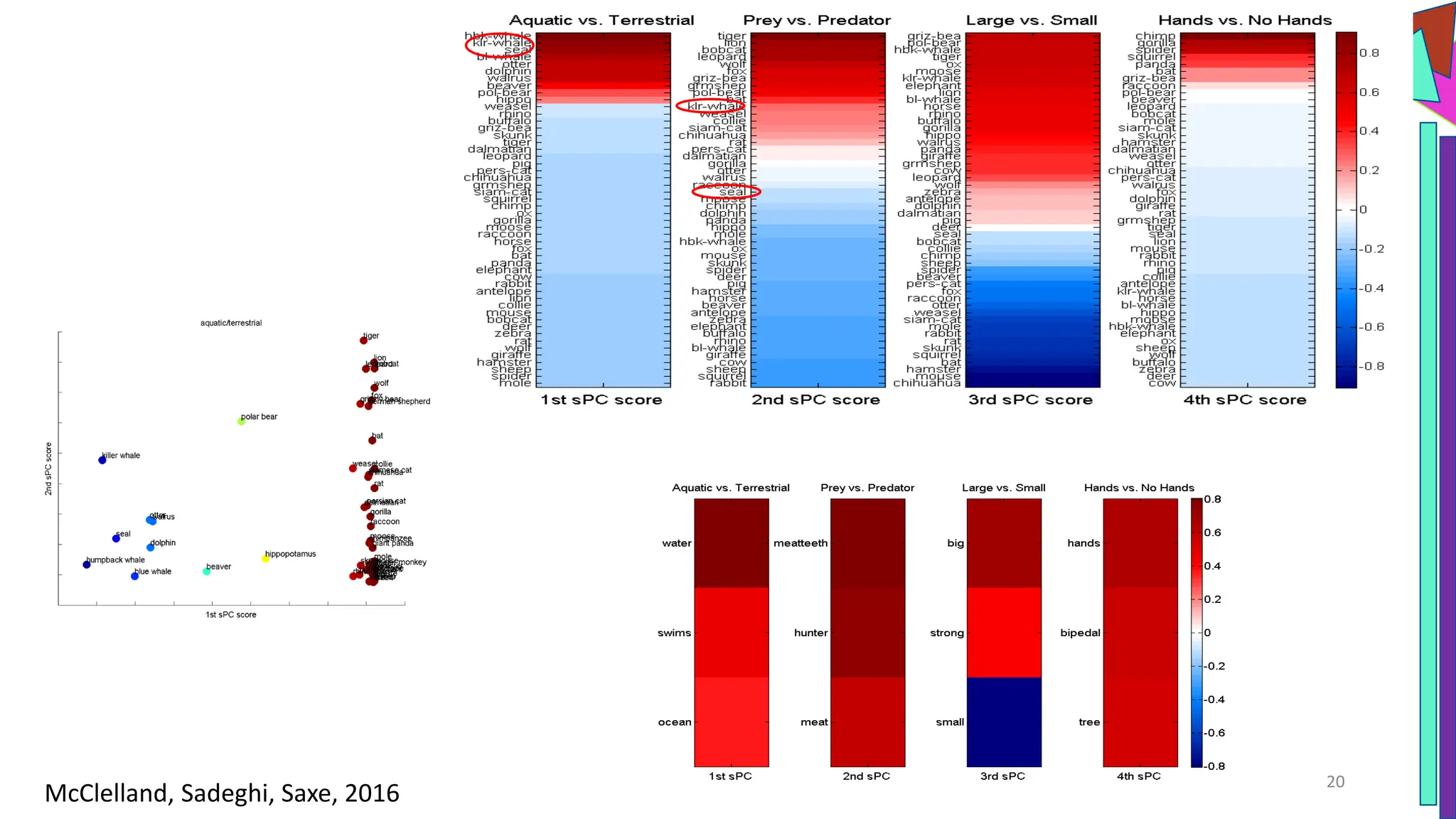

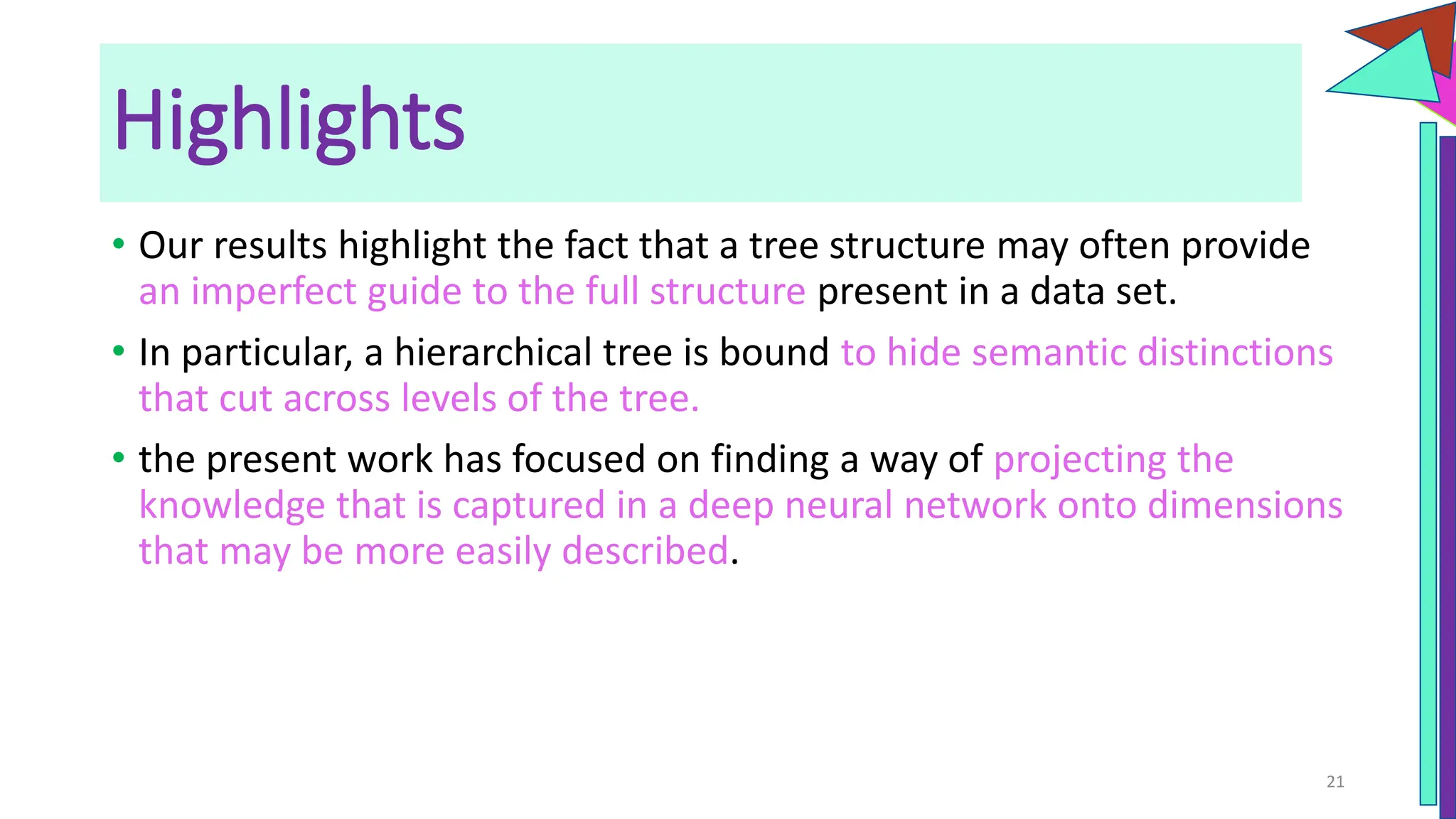

The document discusses a model of semantic category representation suggesting that semantic knowledge arises from interconnected processing units in a neural network. It highlights the limitations of traditional hierarchical structures in reflecting human categorization and proposes alternative connectionist models that capture a quasi-regular structure of knowledge. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of using datasets that characterize human knowledge to enhance understanding of semantic representations.