The document is a comprehensive overview of operations on languages, regular expressions, and finite automata. It explains various operations, including concatenation, union, Kleene closure, and positive closure, along with their definitions and examples. Additionally, it covers the basic terminology of regular expressions and details the processes for converting regular expressions to non-deterministic and deterministic finite automata.

![Dr. Mohamed Gamal Faculty of Computers and Informatics

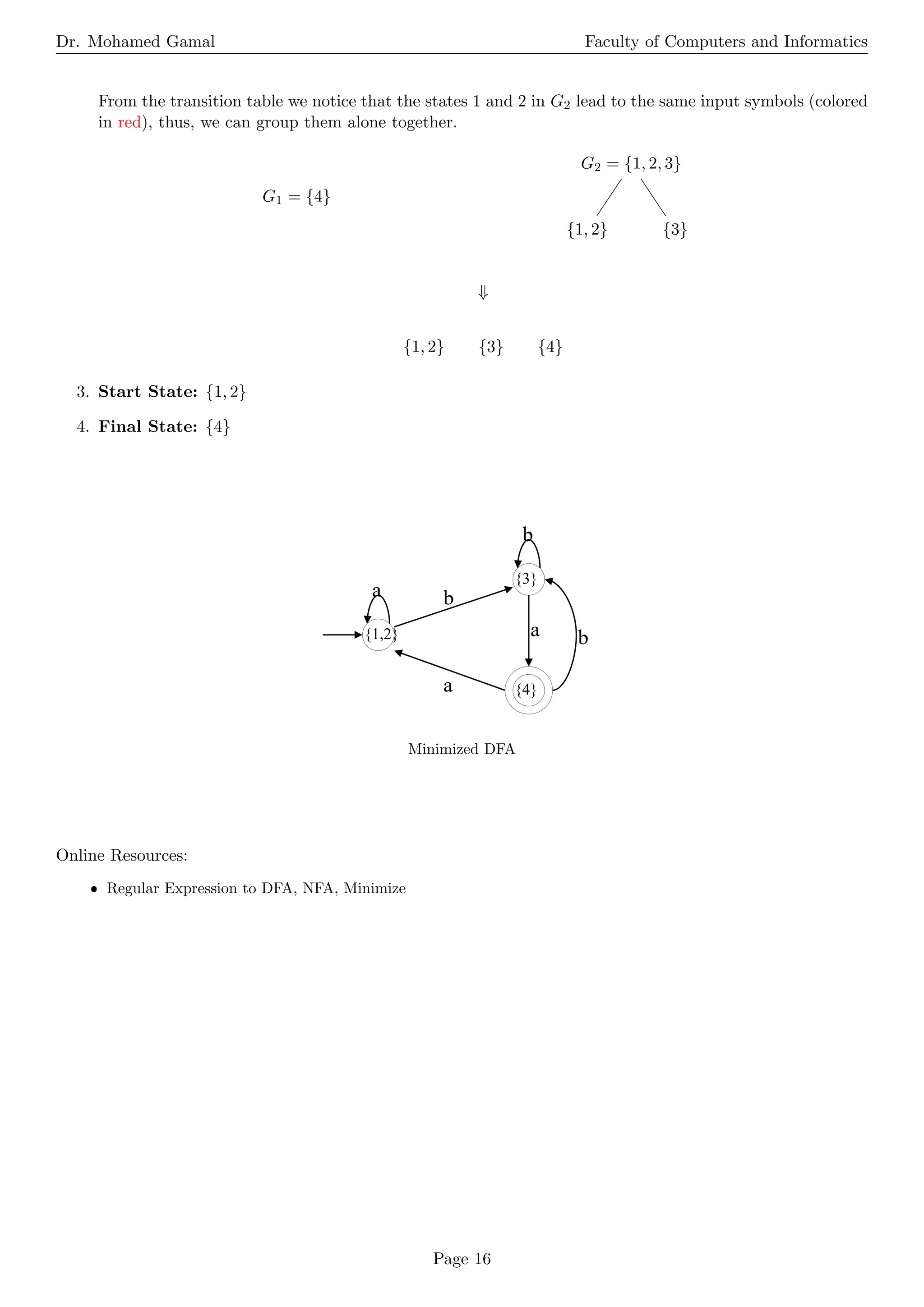

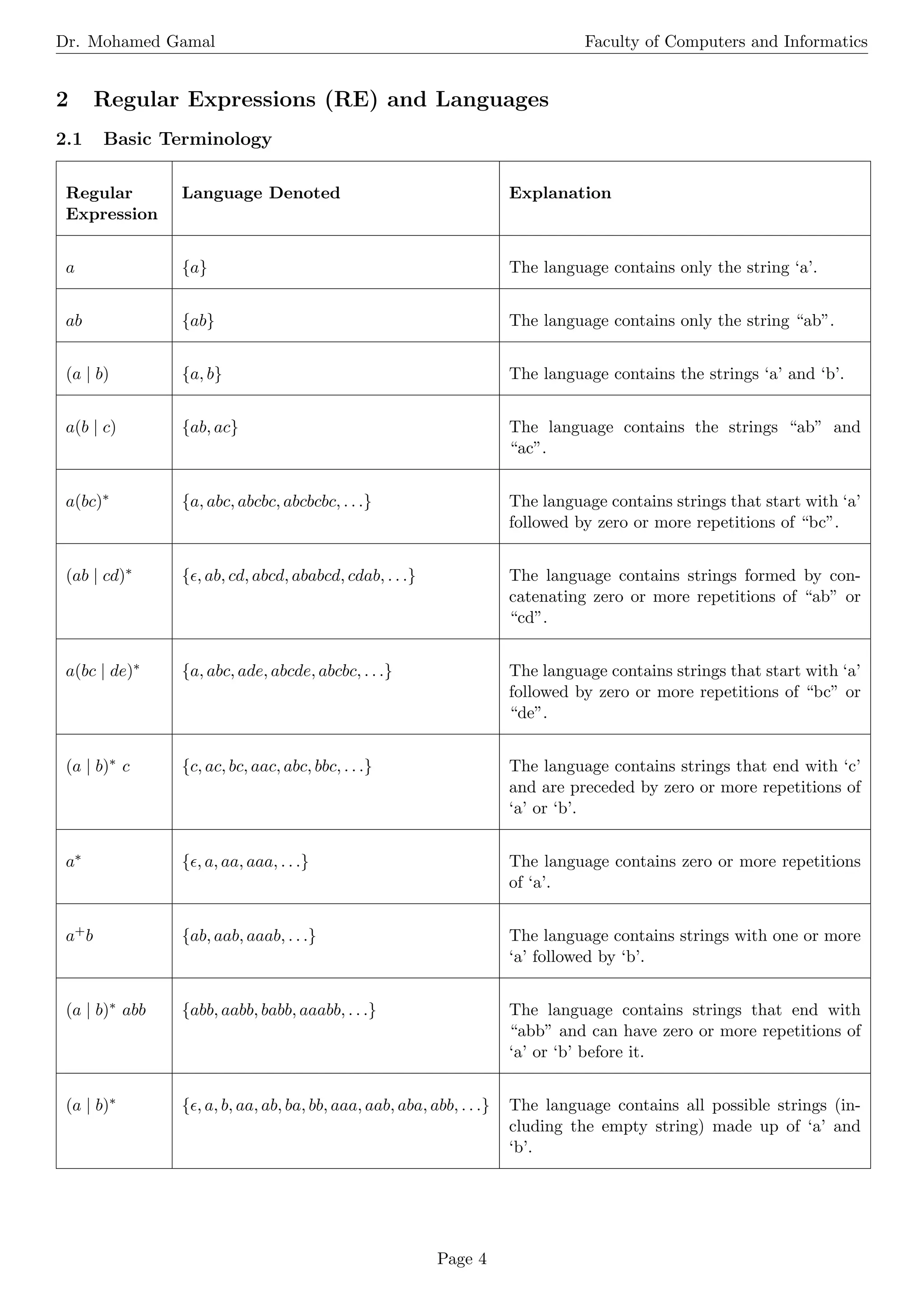

2.2 C-Language Identifiers and Numbers

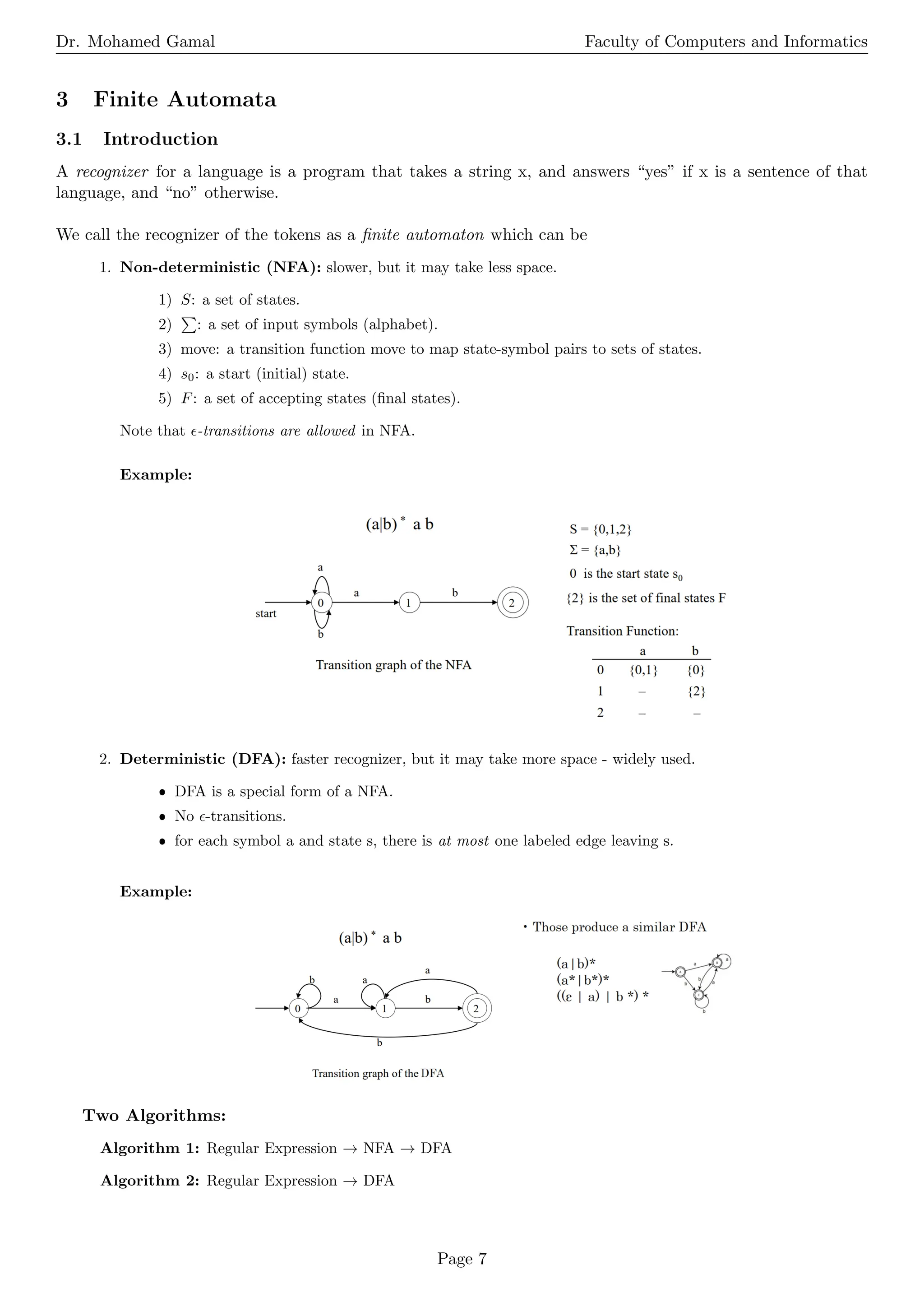

C-Language Identifiers

Definition Regular Expression Example

letter [A-Za-z ] a, B,

digit [0-9] 0, 1, 9

CId letter ( letter — digit )∗ var, myVar123, temp

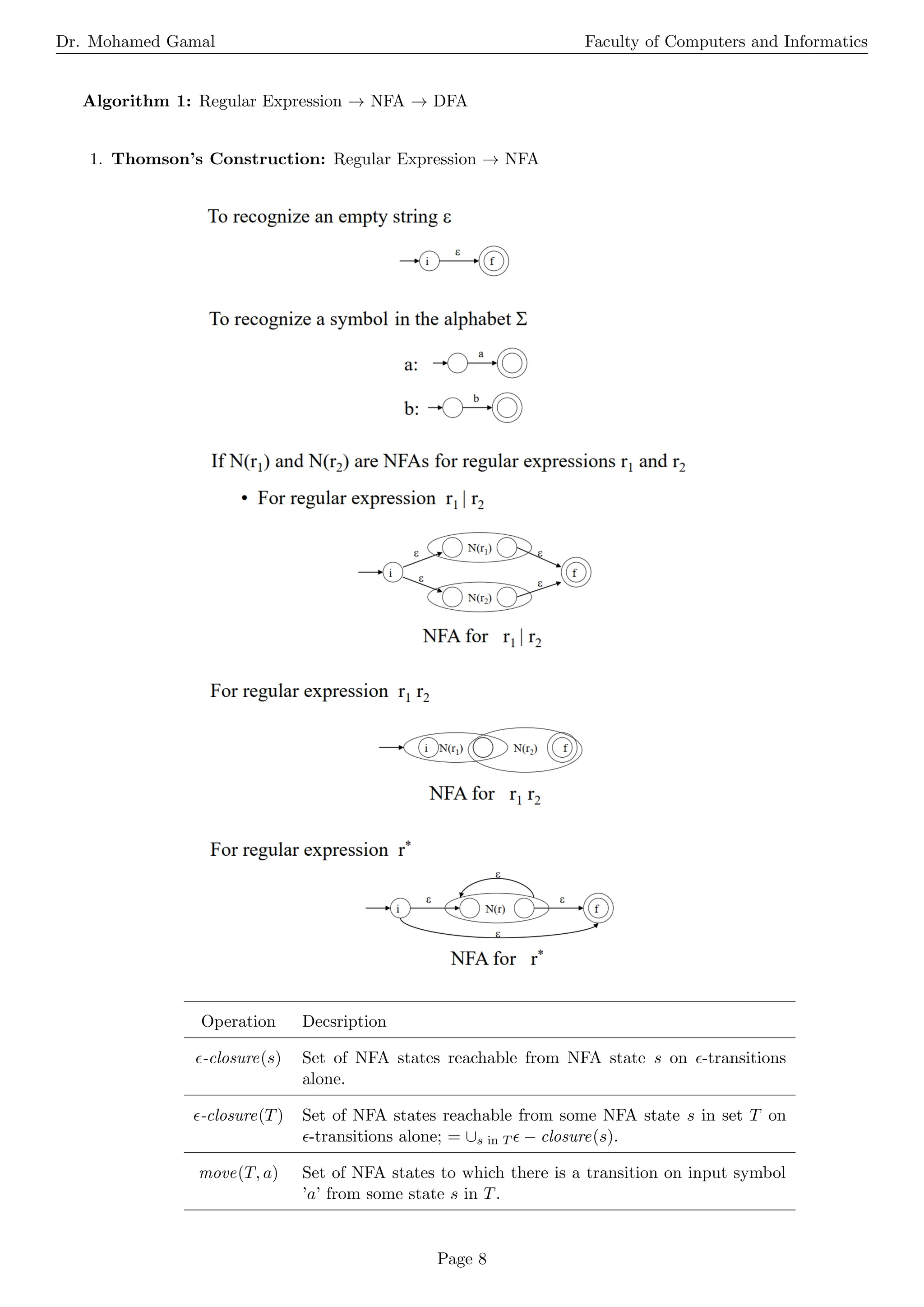

Unsigned Integer or Floating Point Numbers

Definition Regular Expression Example

digit [0-9] 0, 1, 9

digits digit+ 123, 4567

number digits (.digits)? ( E [+−]? digits)? 42, 3.14, 2.71E-3

Regular Expressions Validators:

ˆ https://regexr.com/

ˆ https://regex101.com/

Page 5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complierdesign-operatingsonlanguagesrefiniteautomata-240920162828-5f5b45f9/75/Complier-Design-Operations-on-Languages-RE-Finite-Automata-5-2048.jpg)