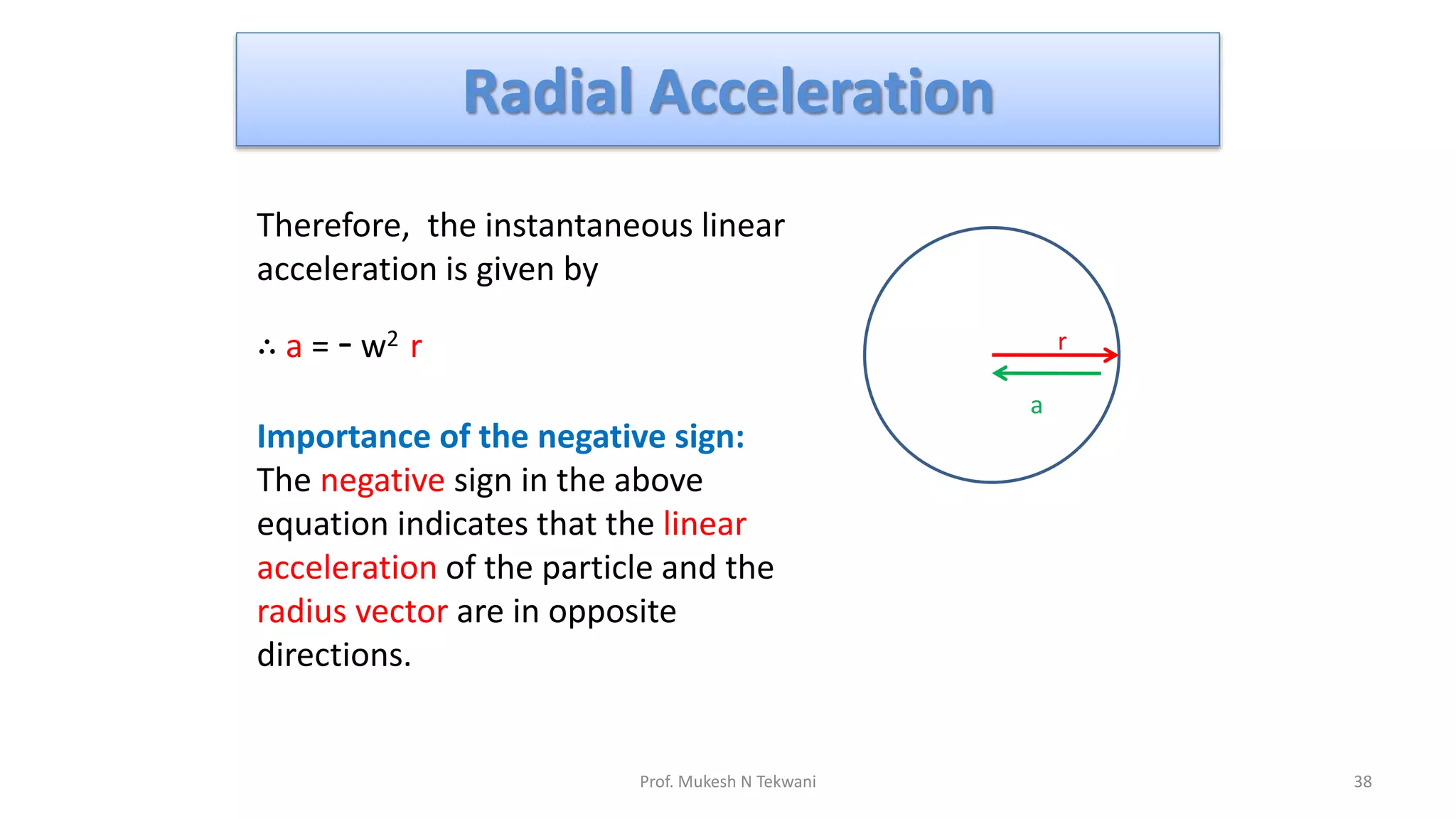

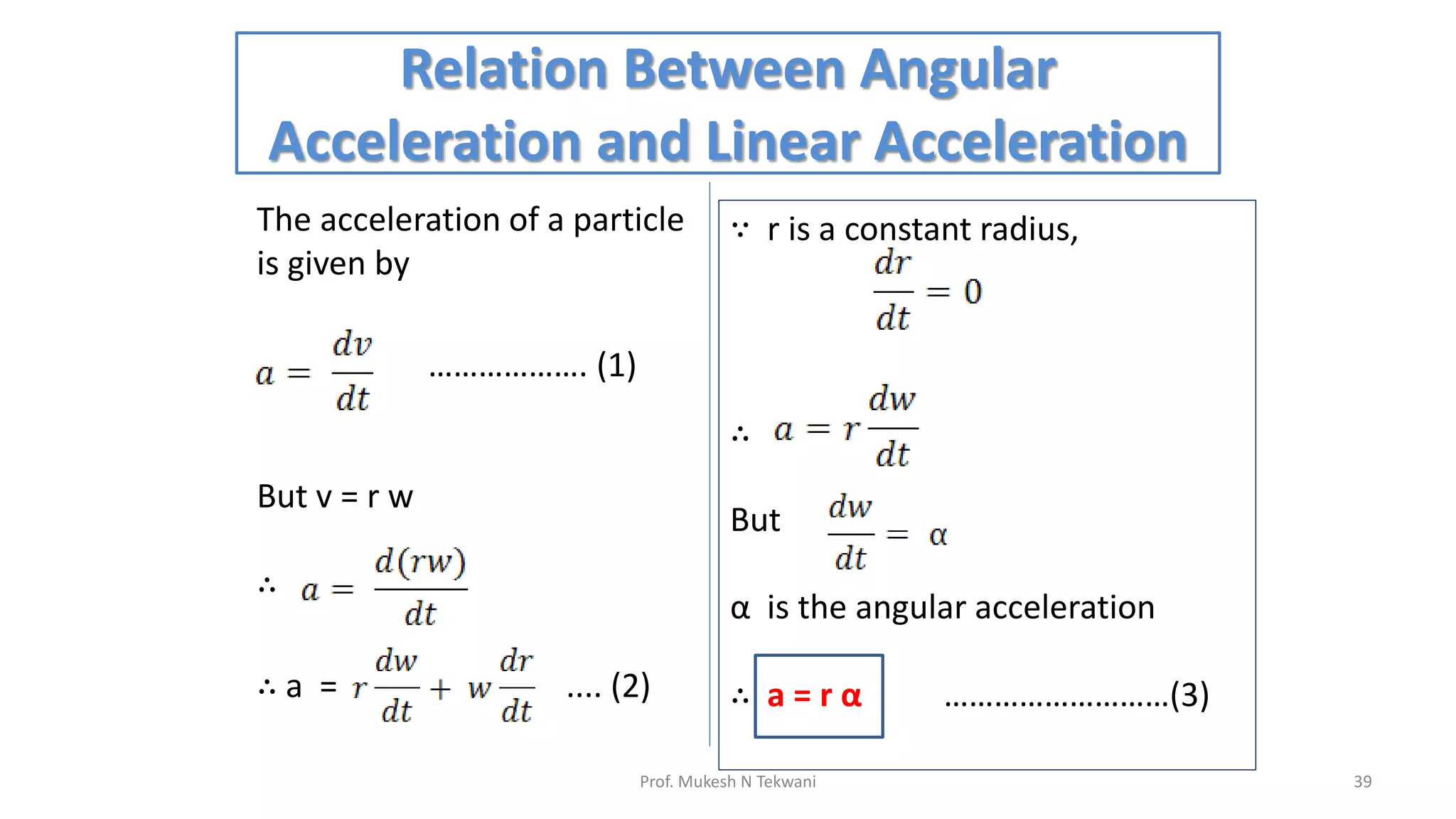

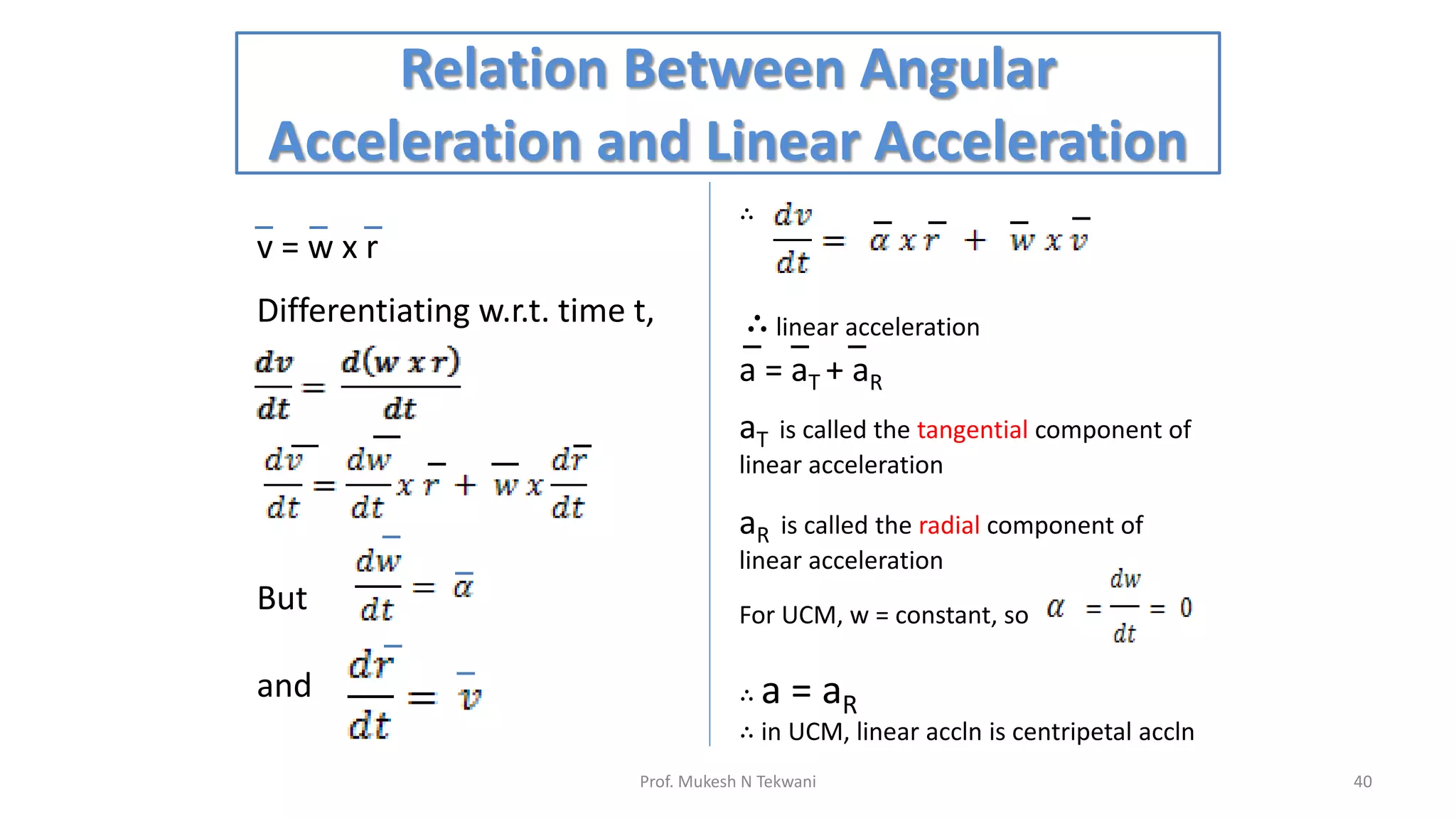

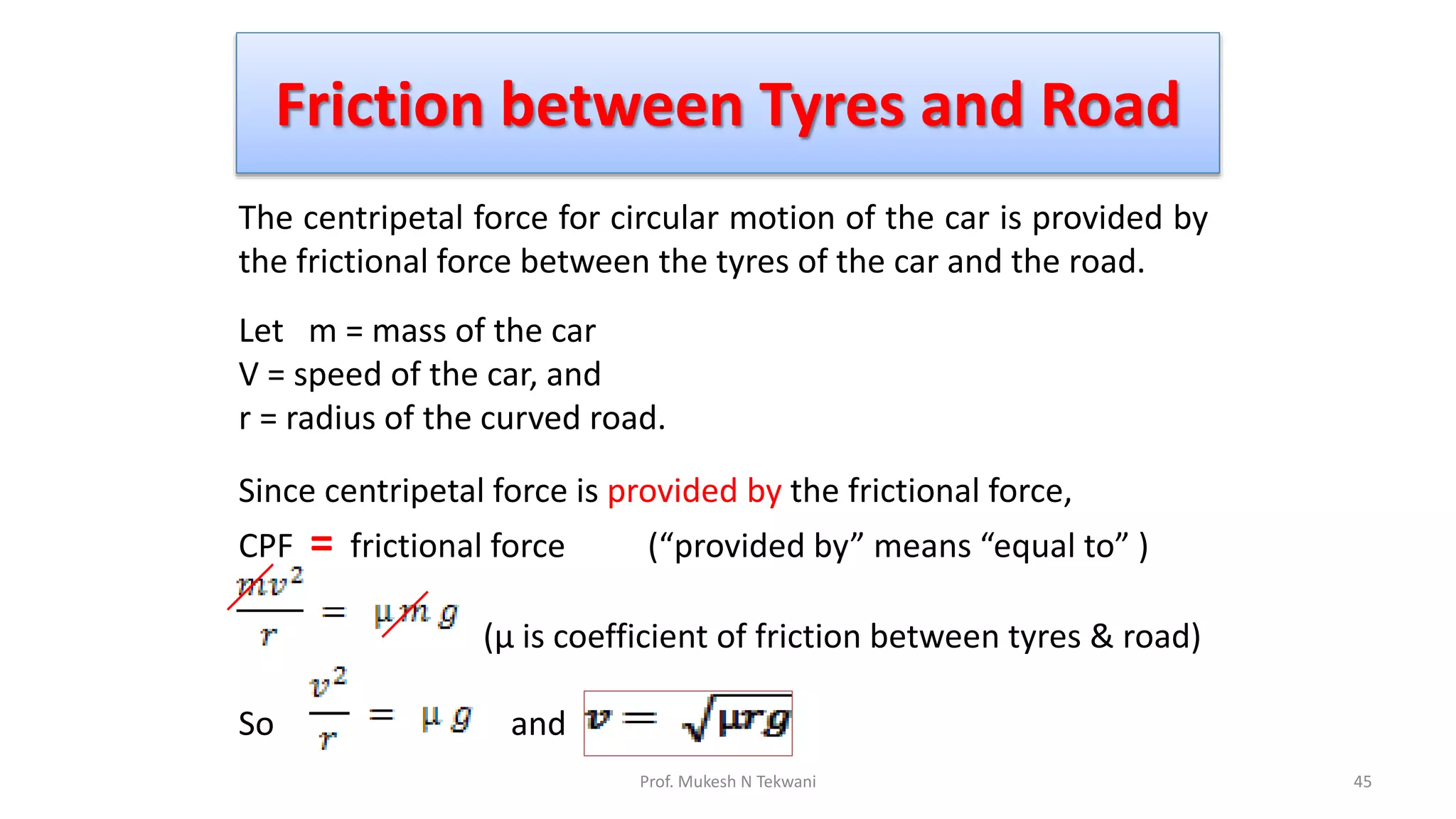

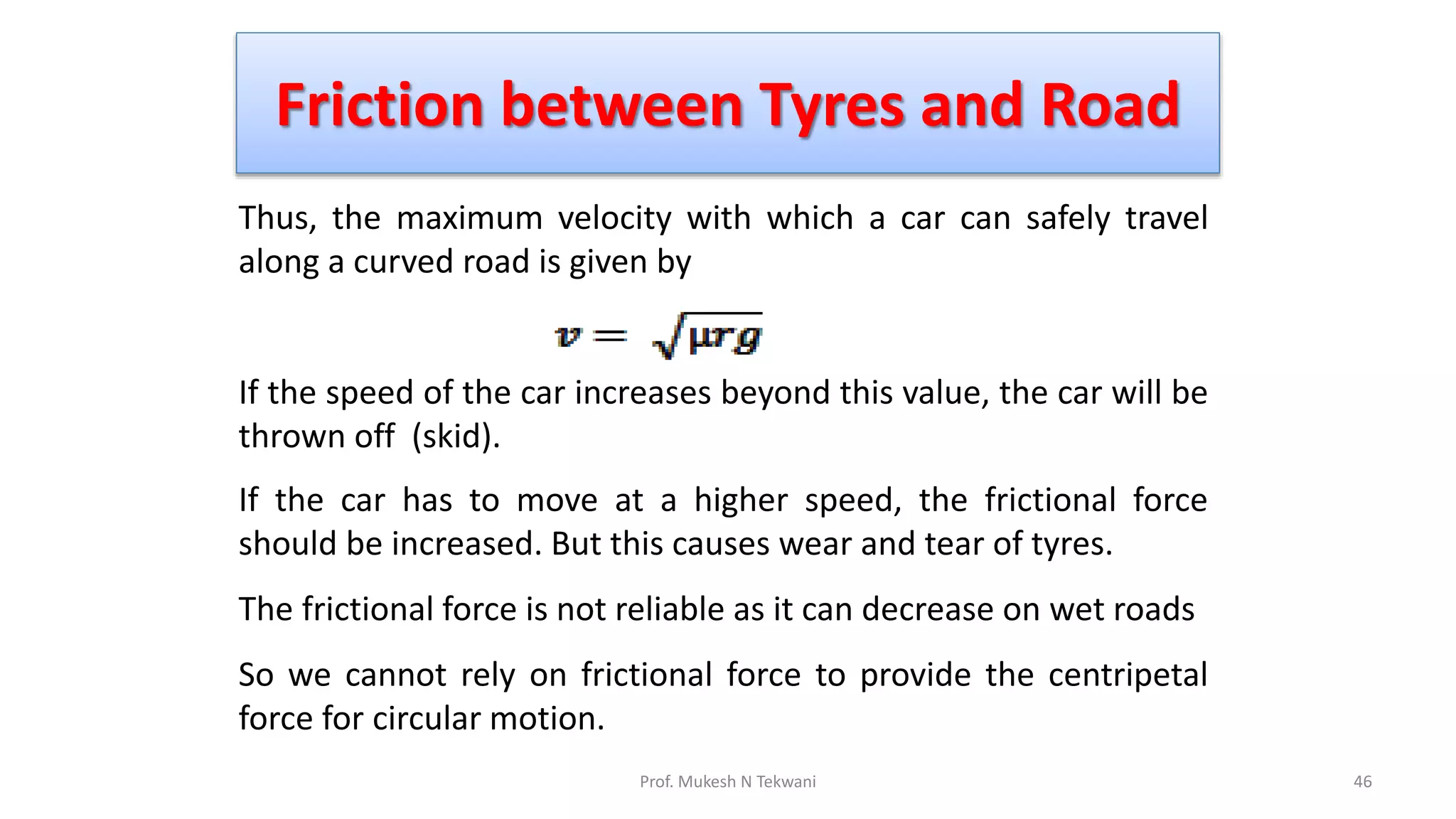

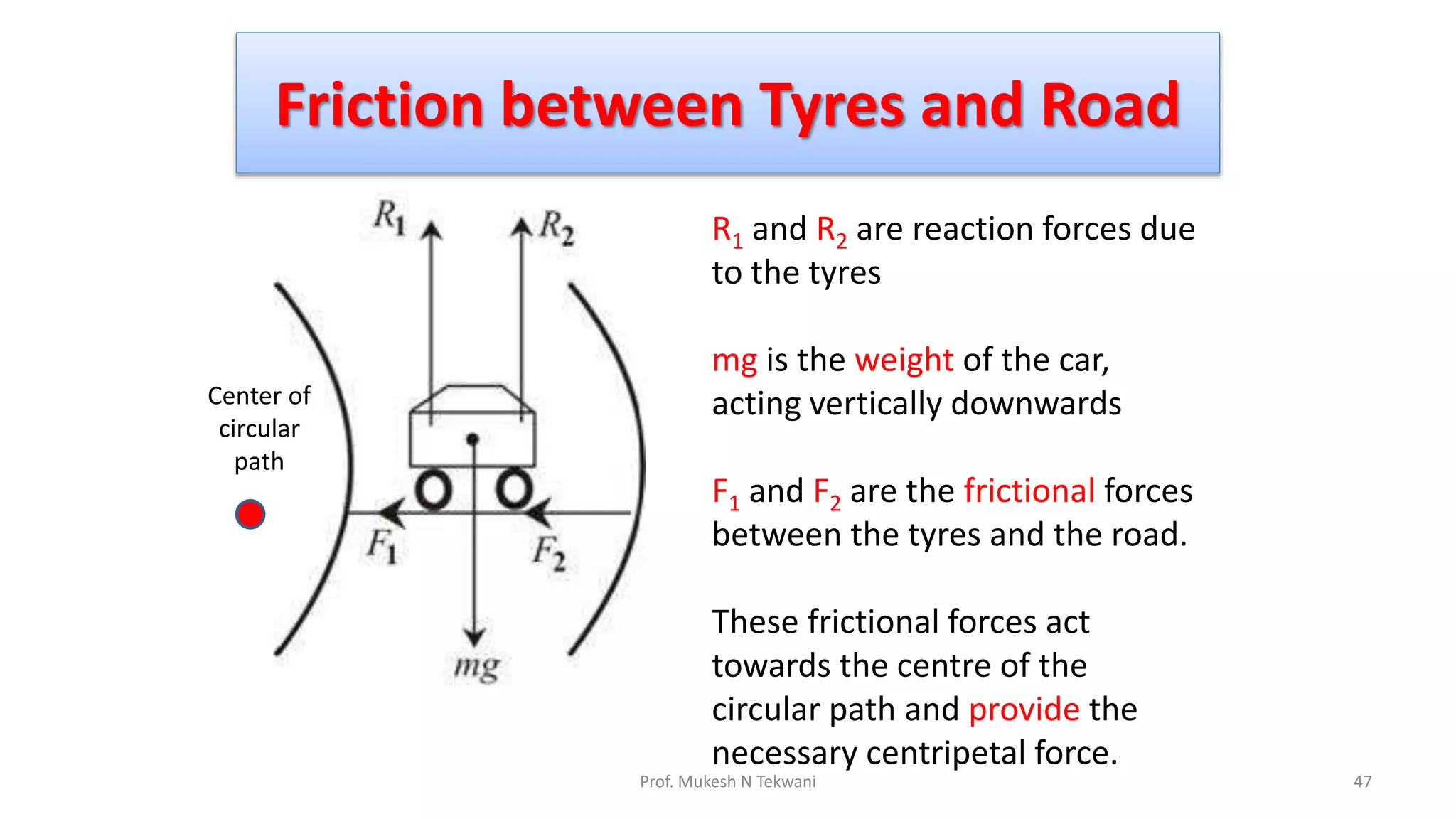

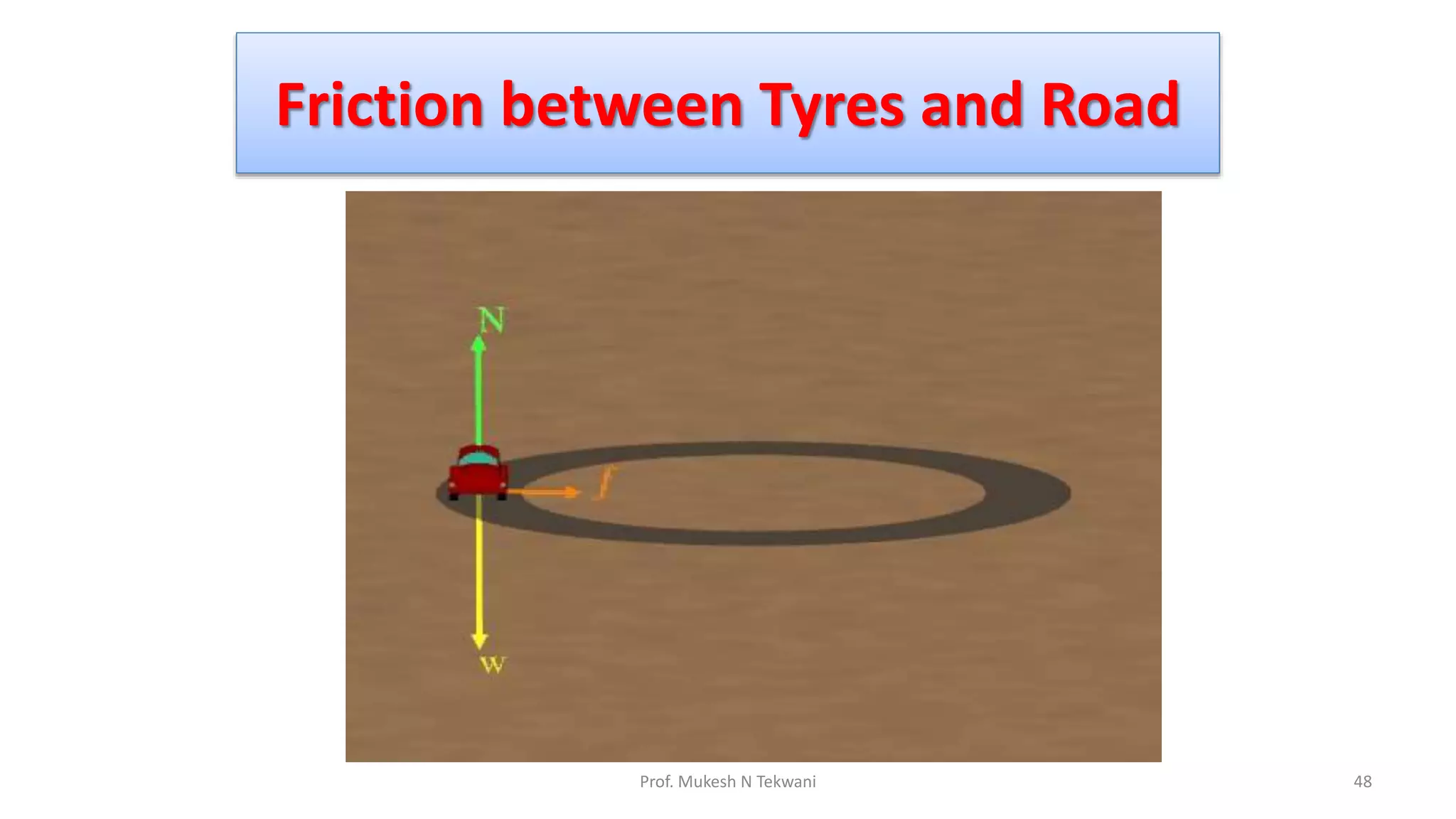

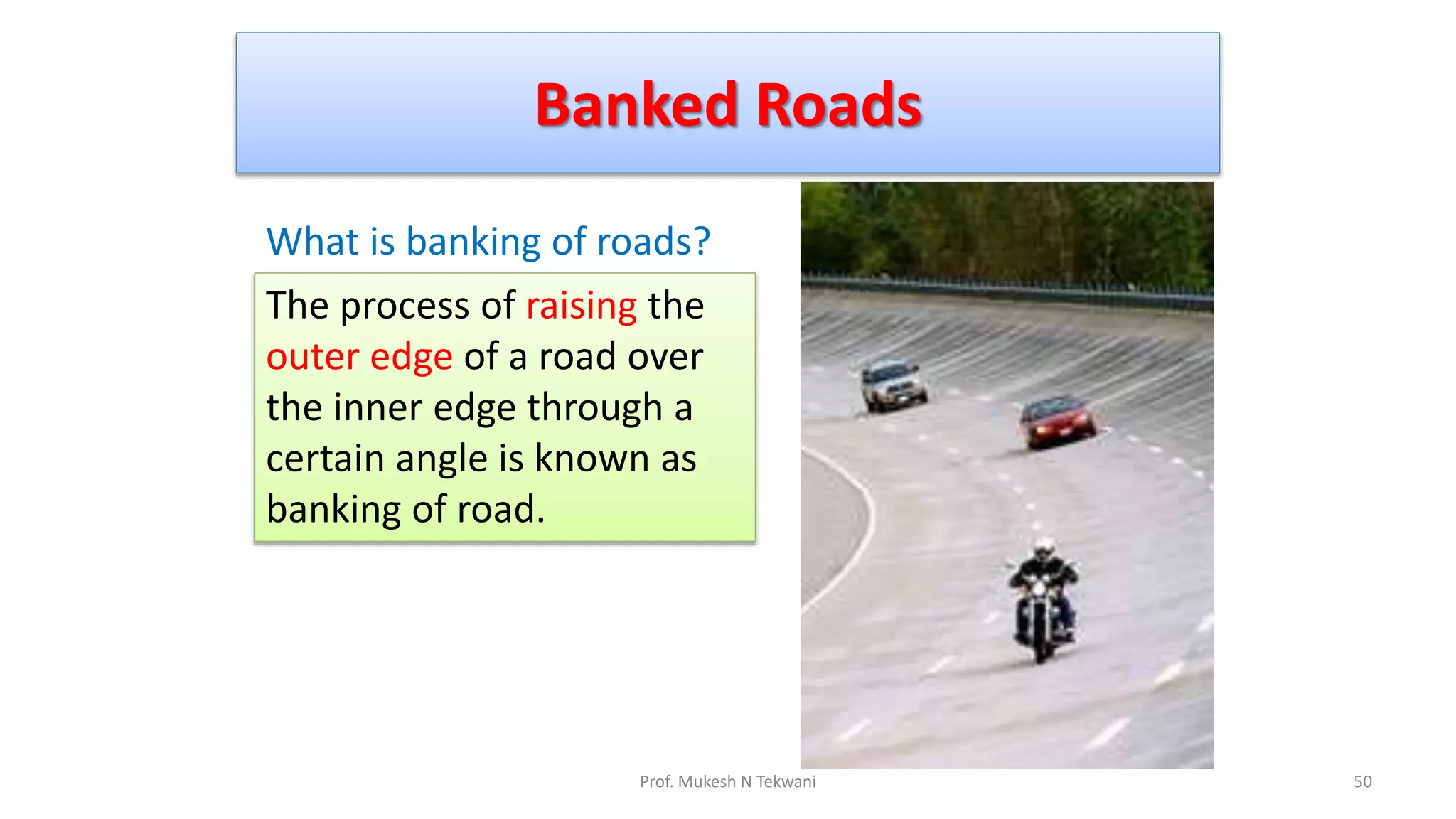

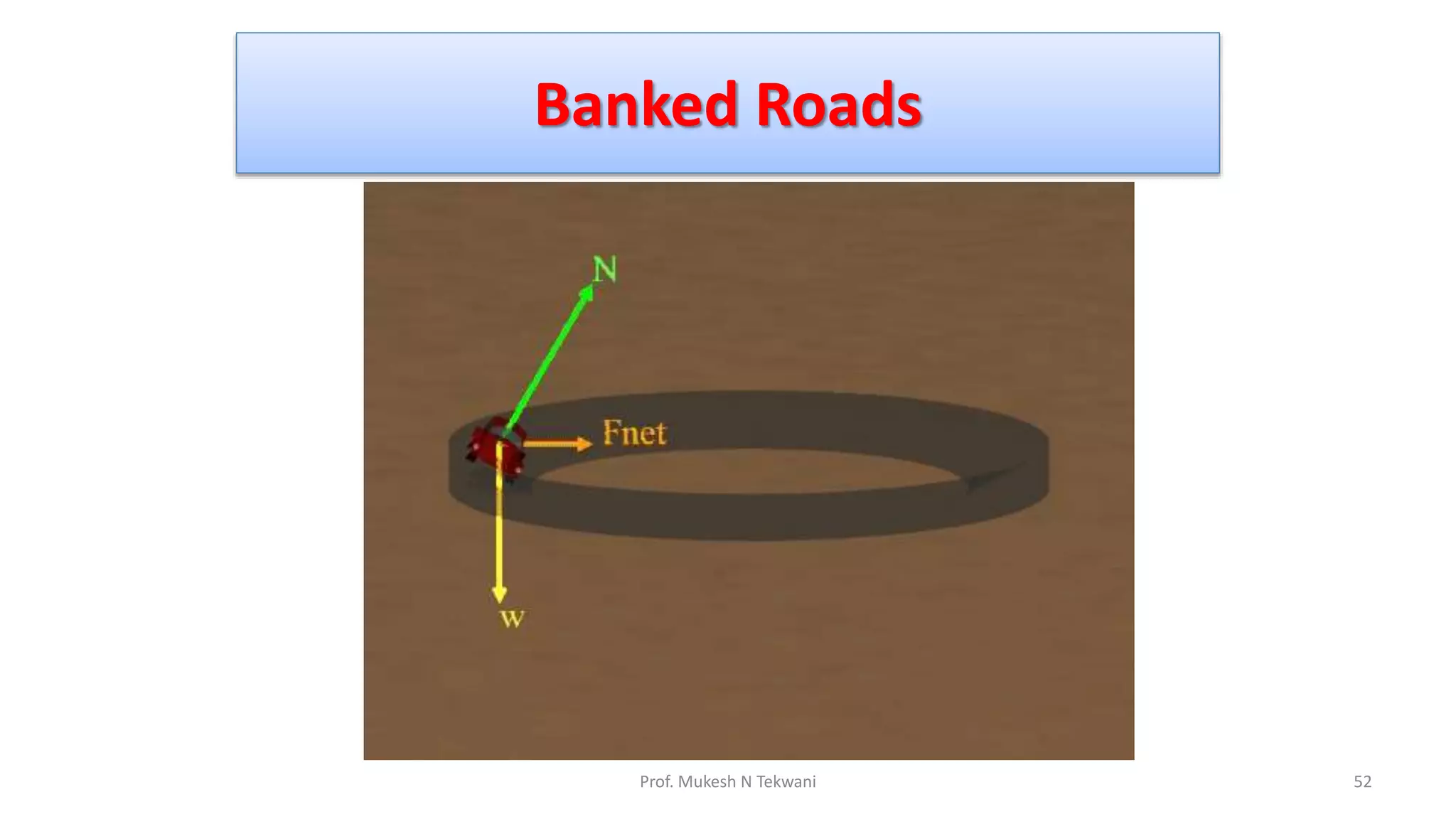

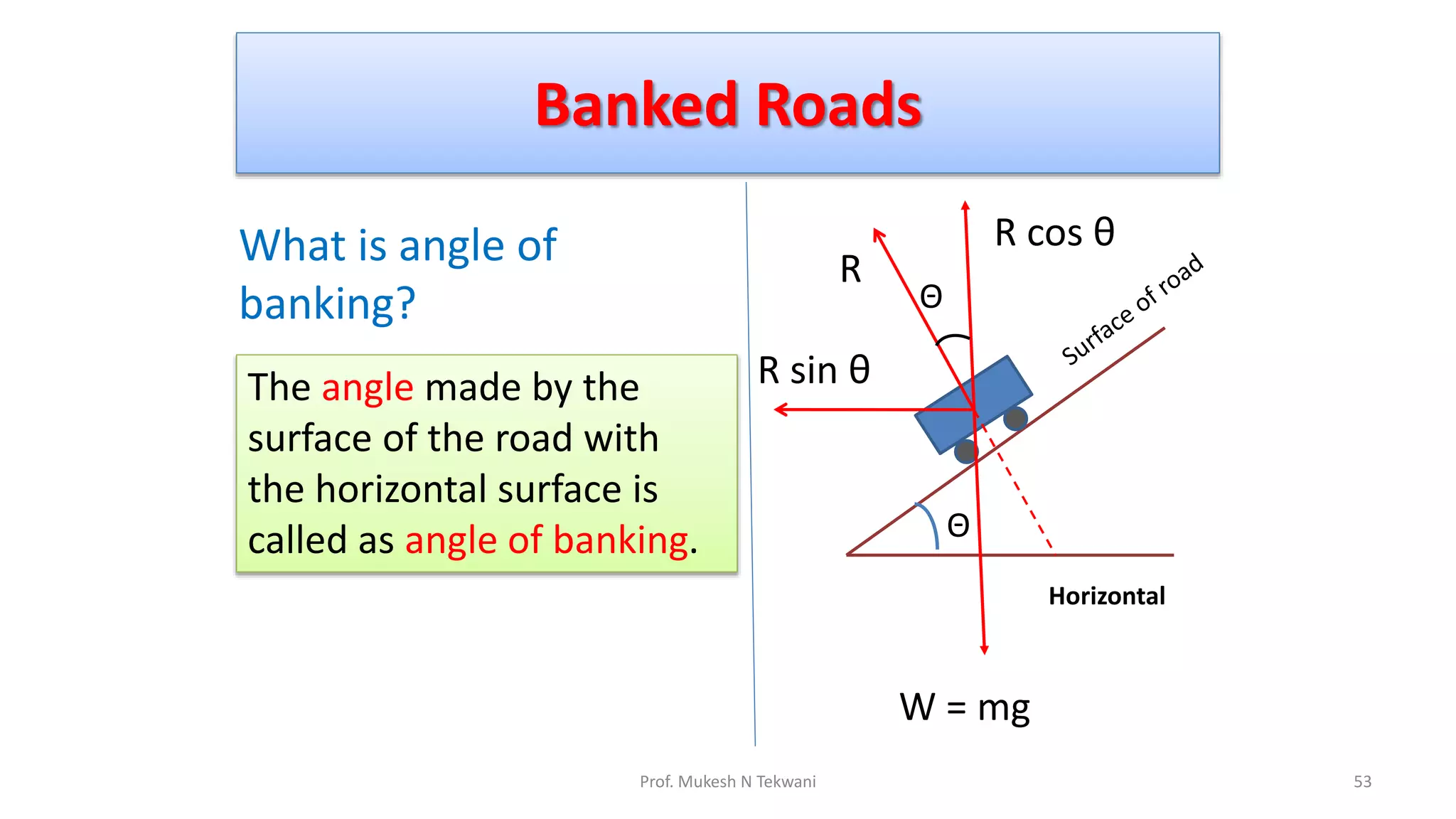

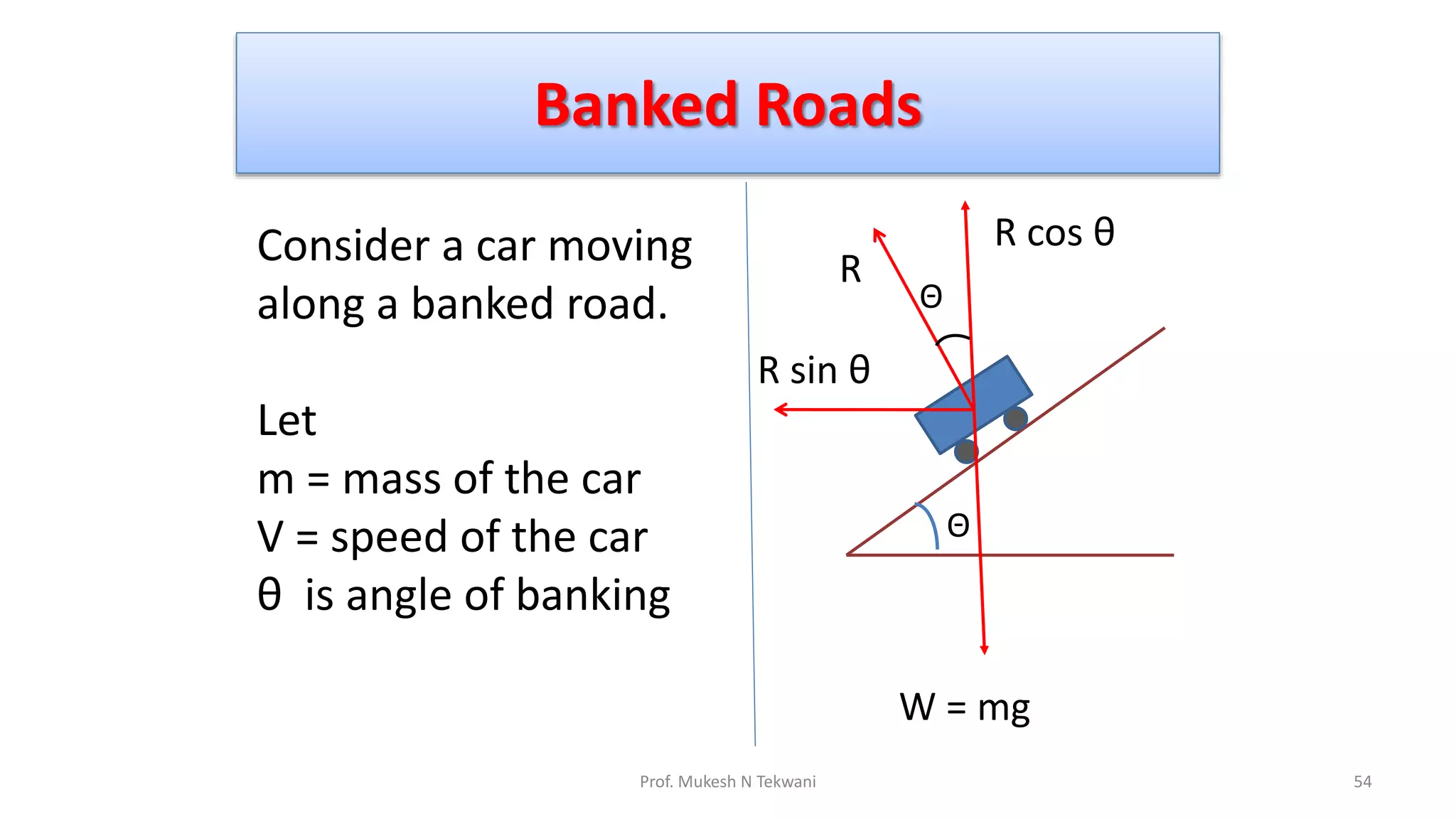

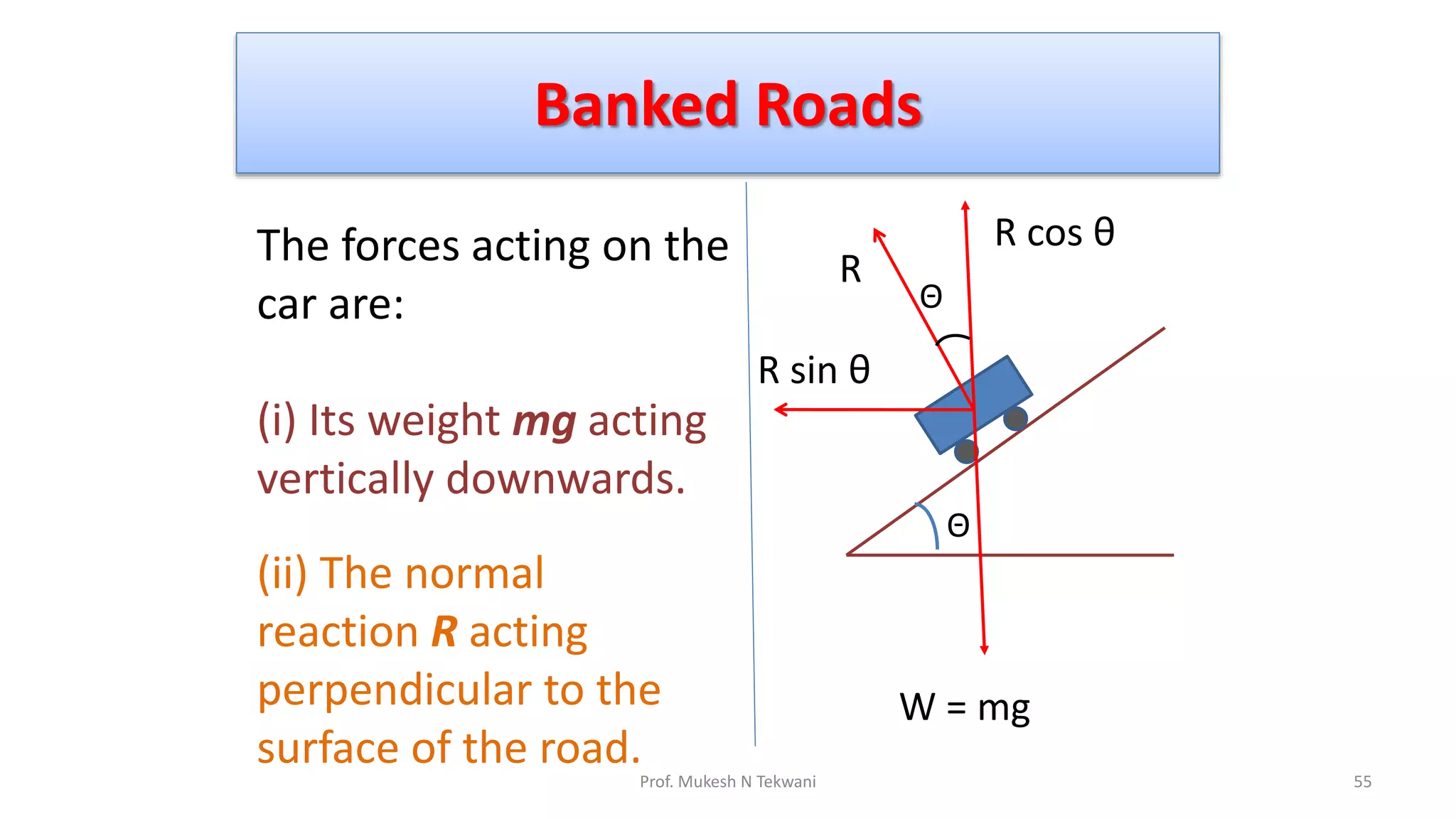

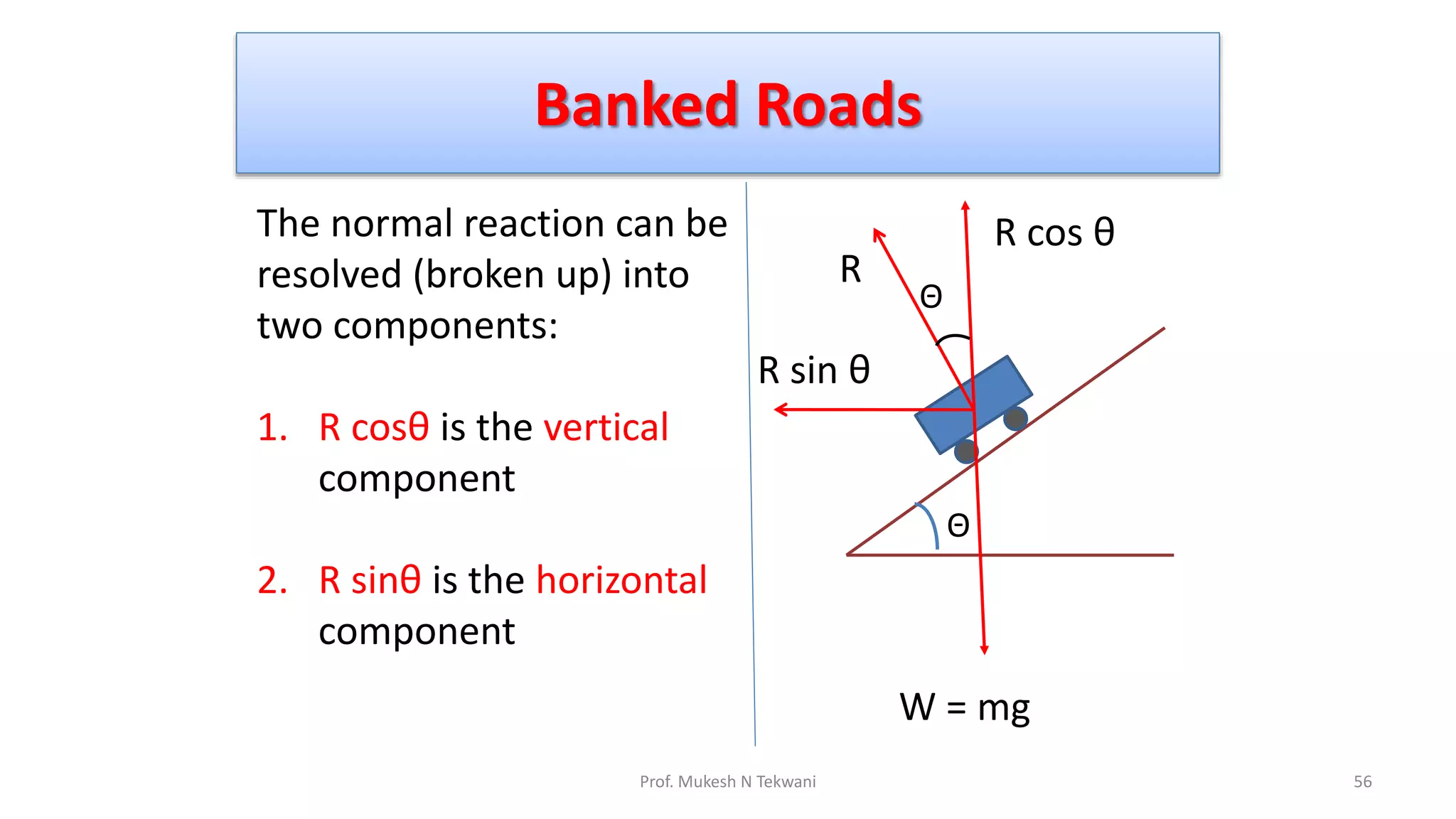

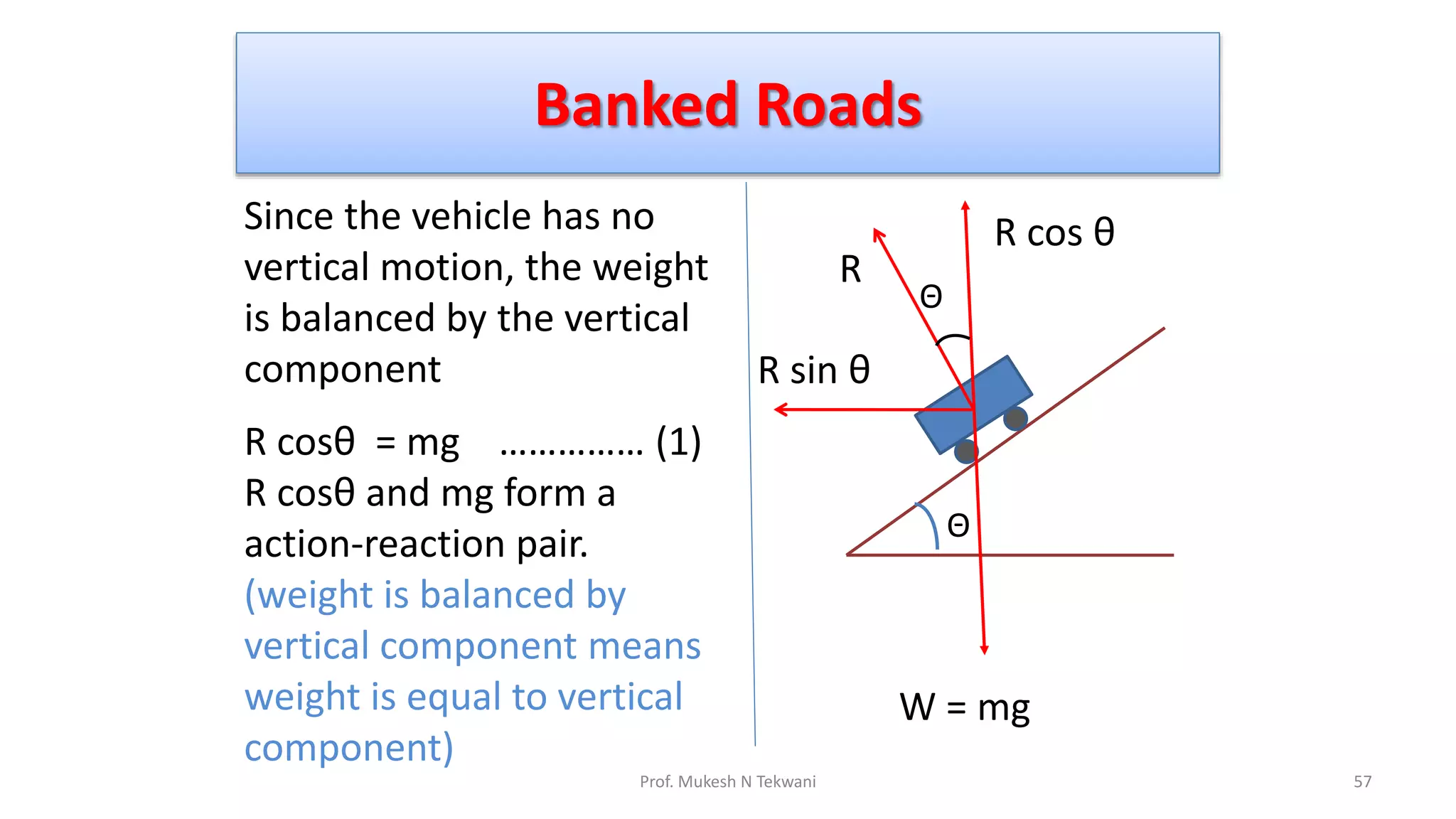

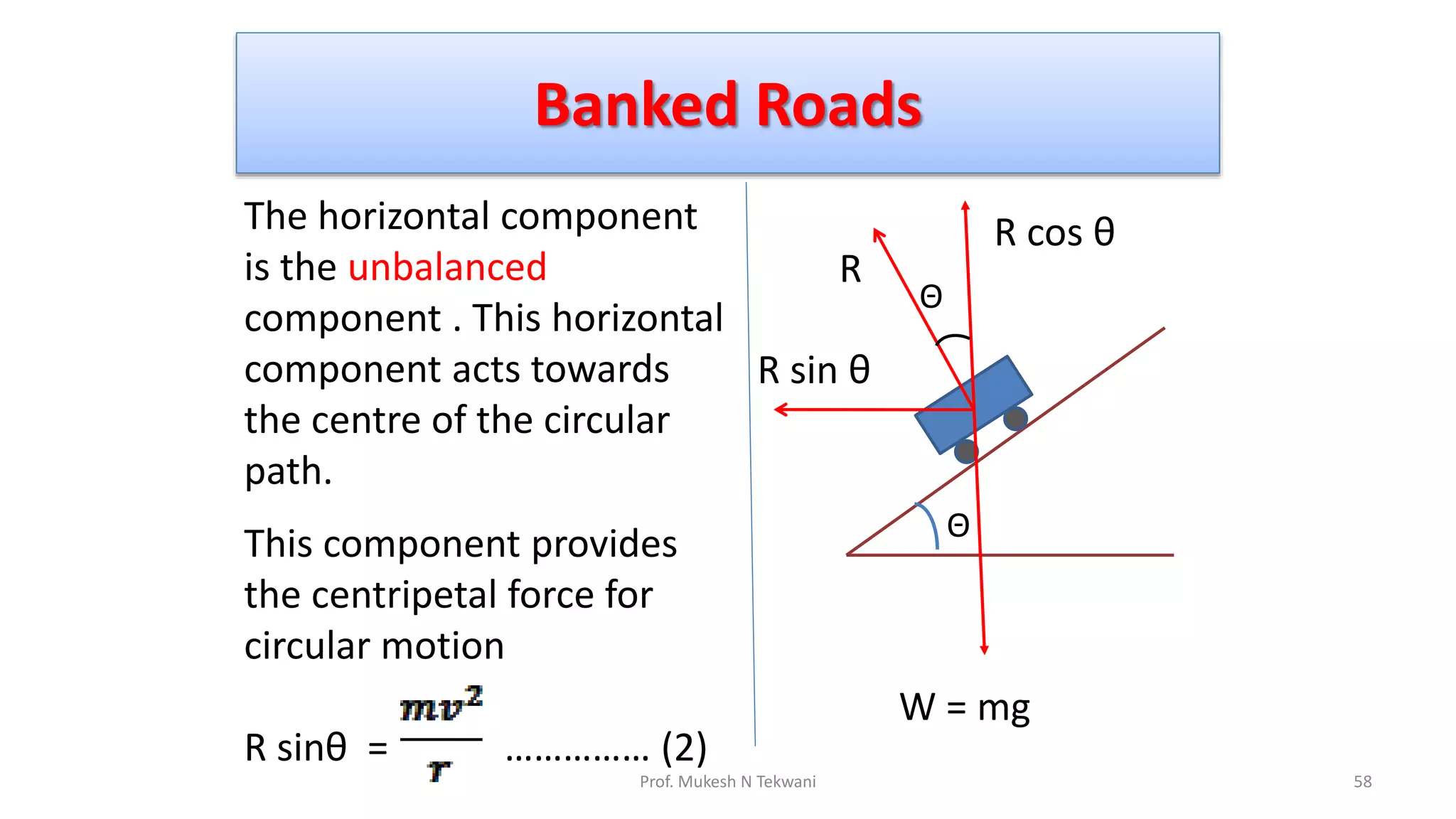

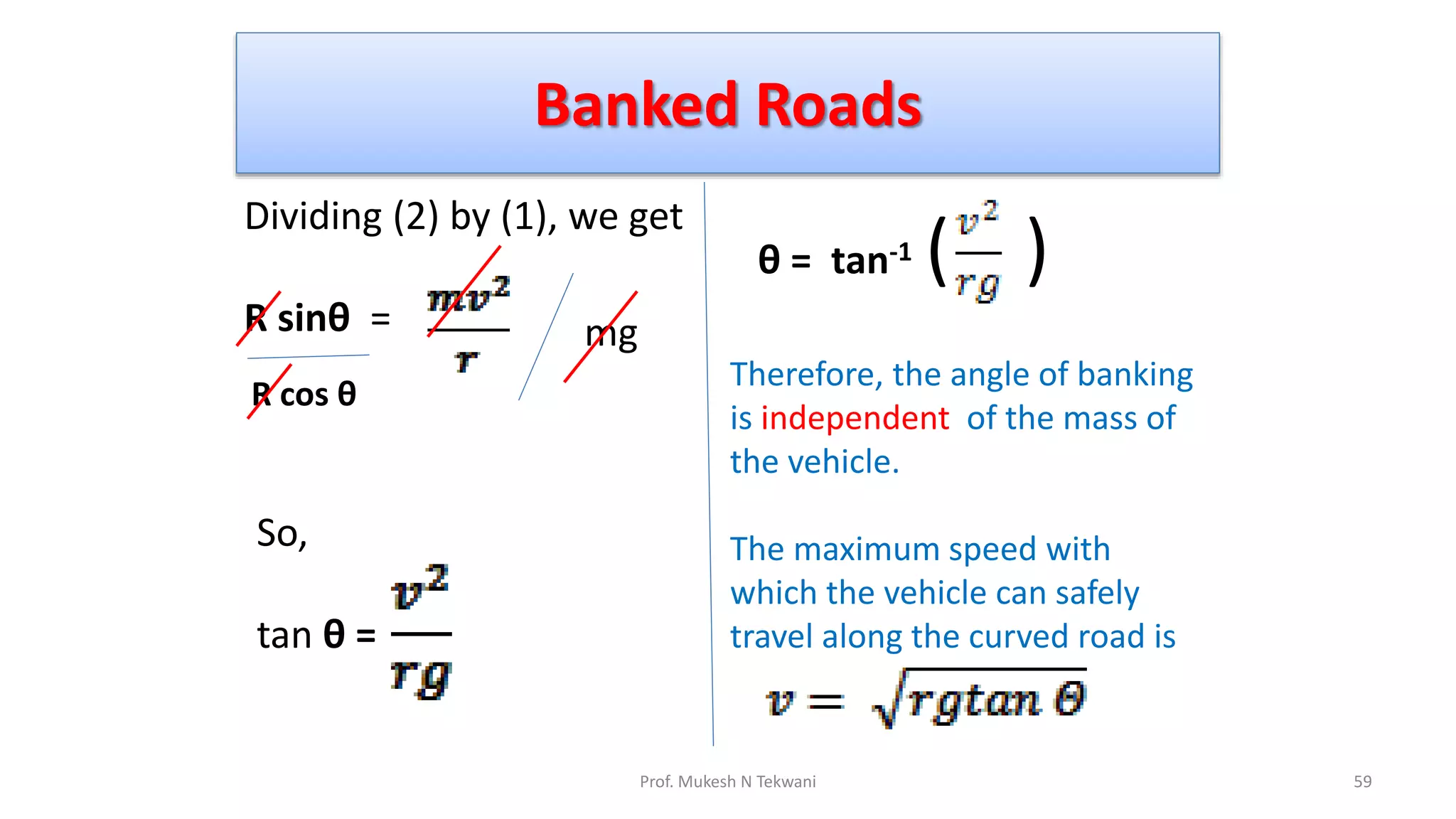

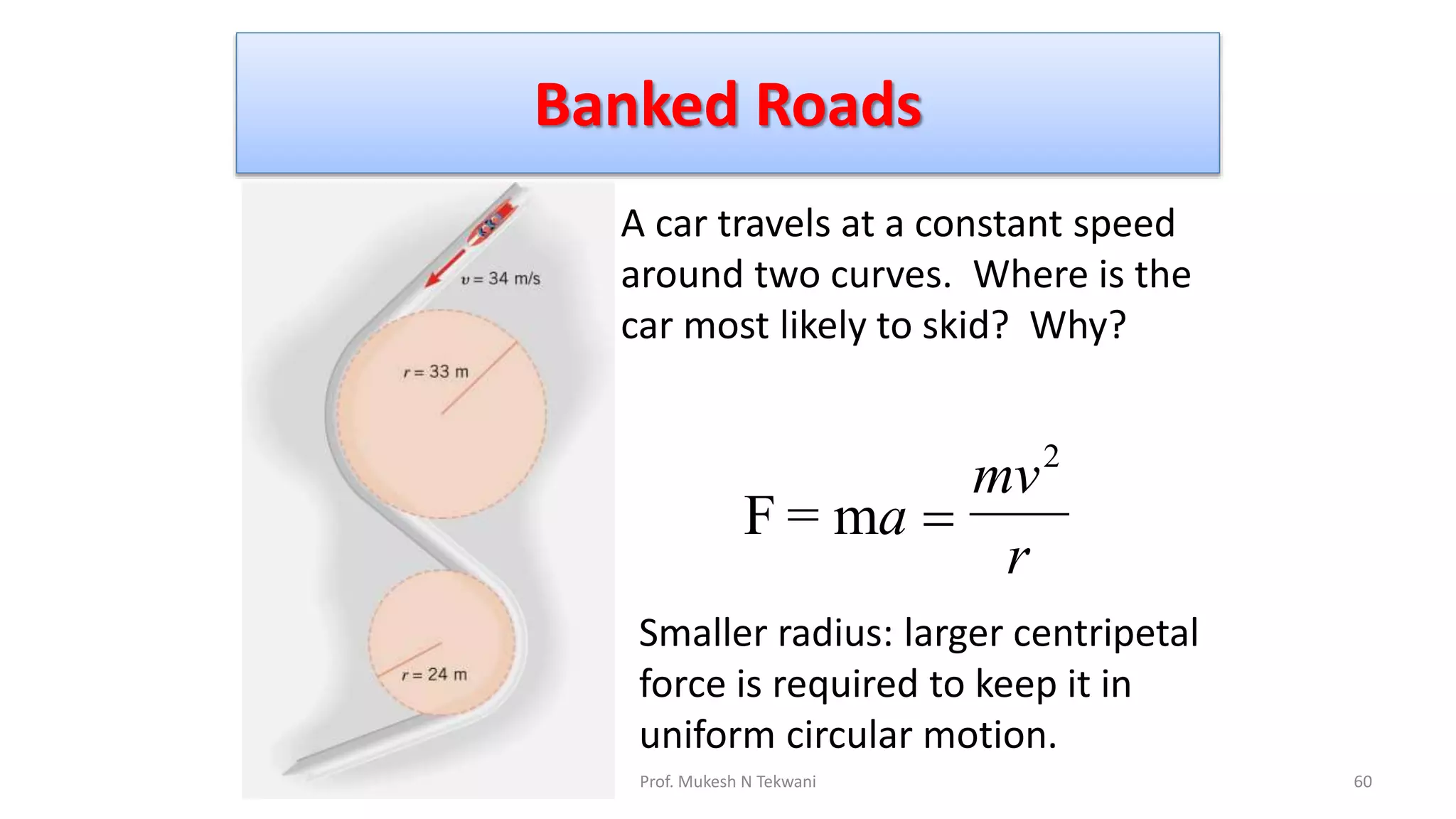

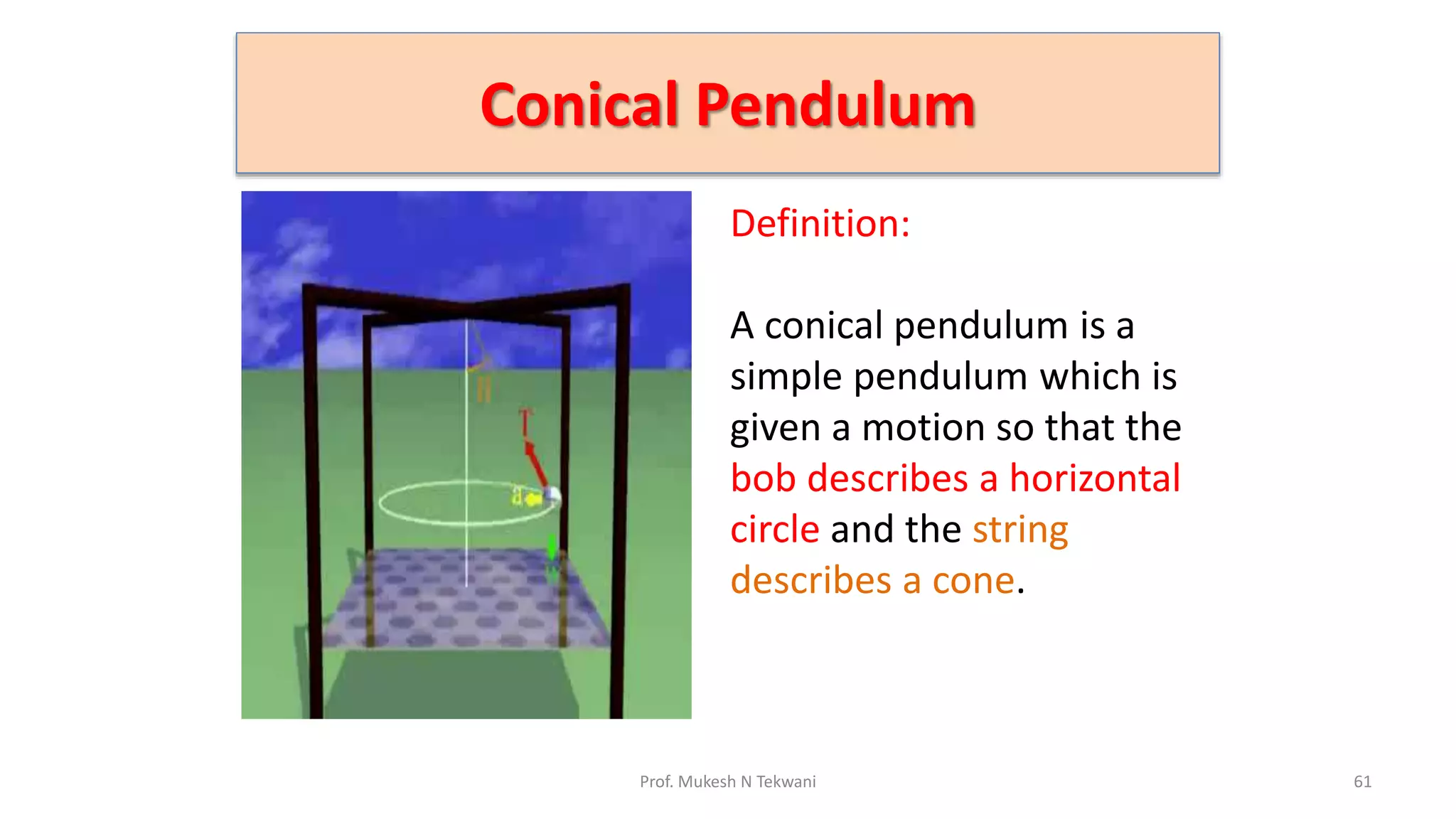

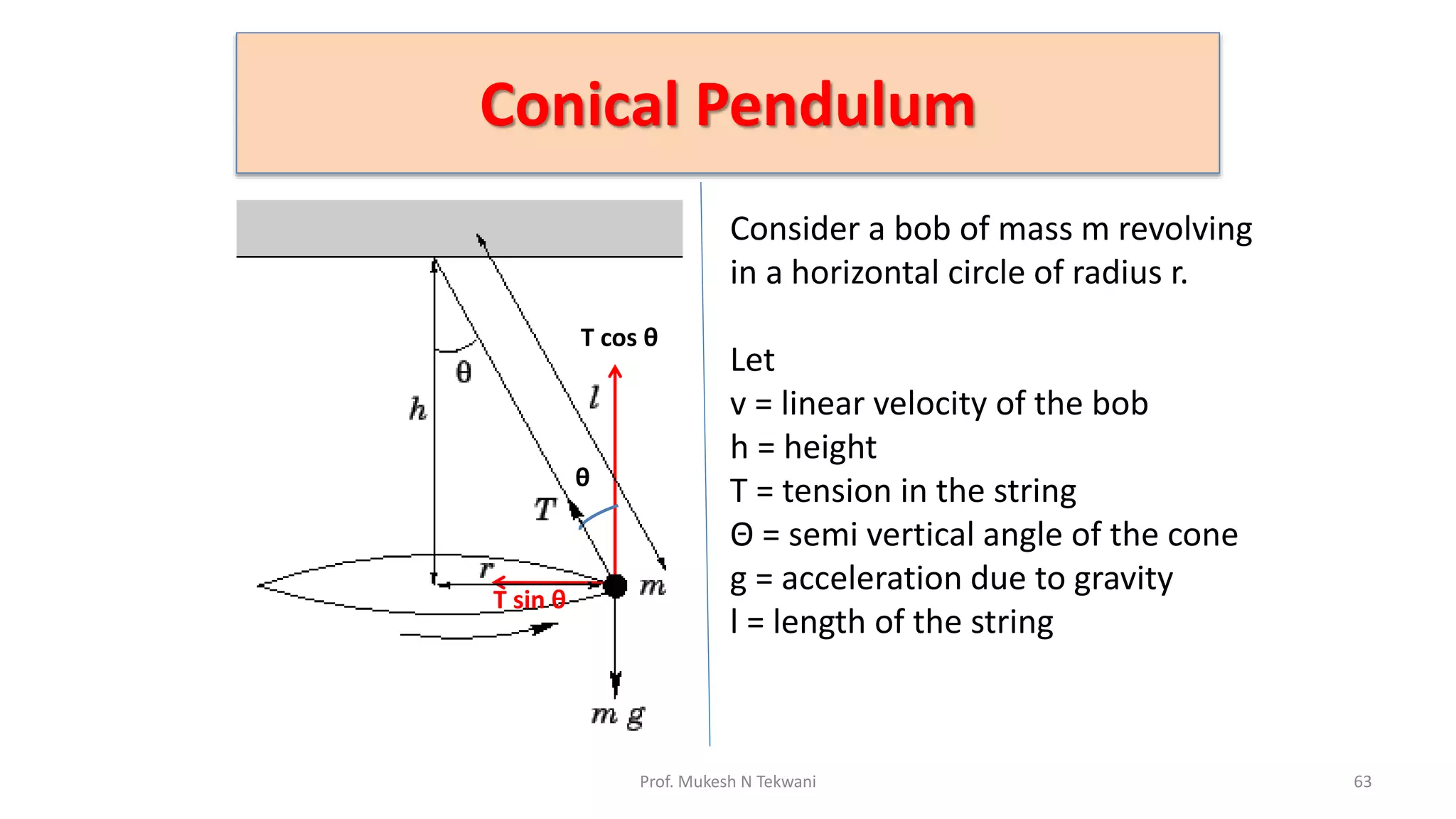

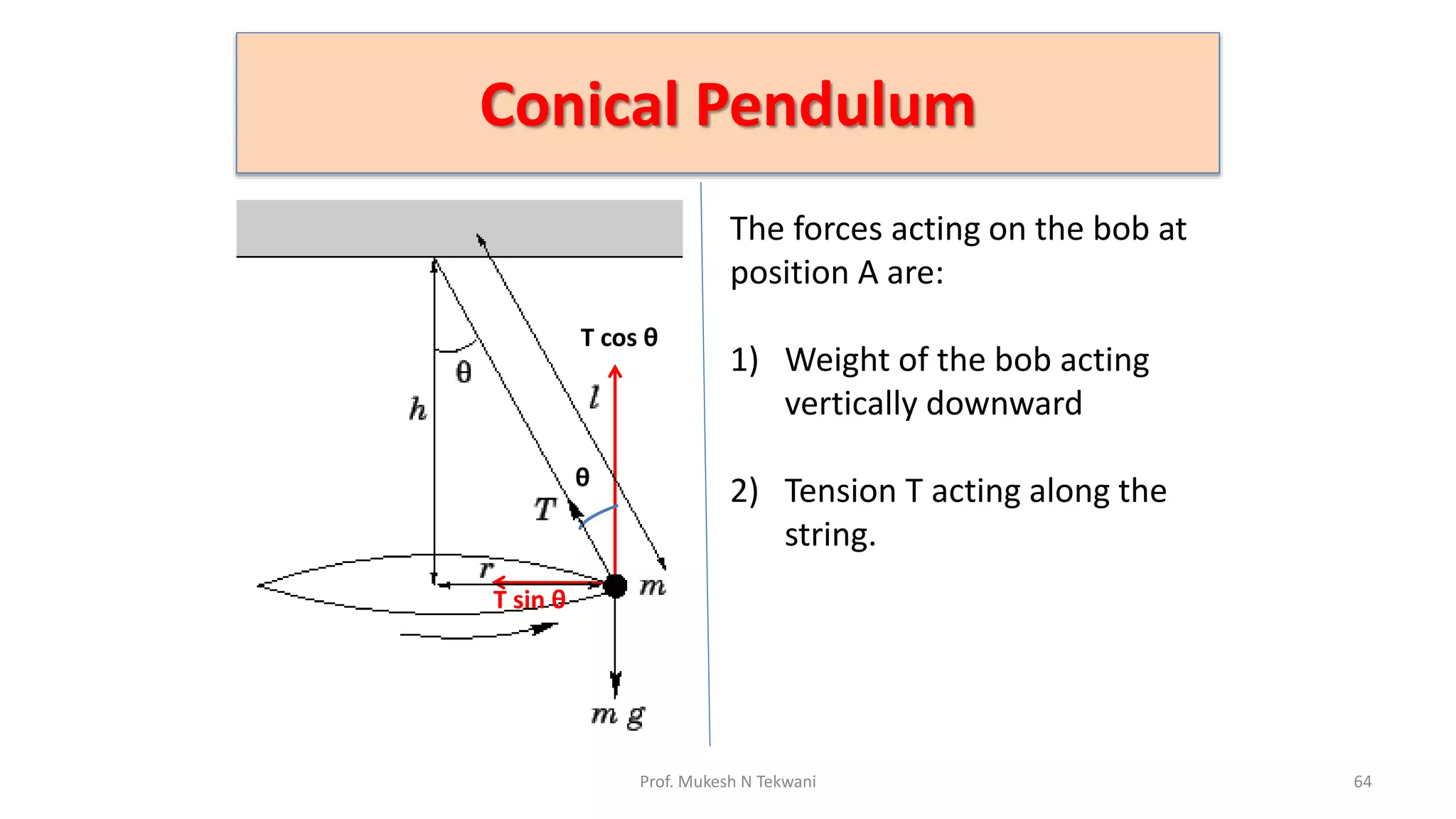

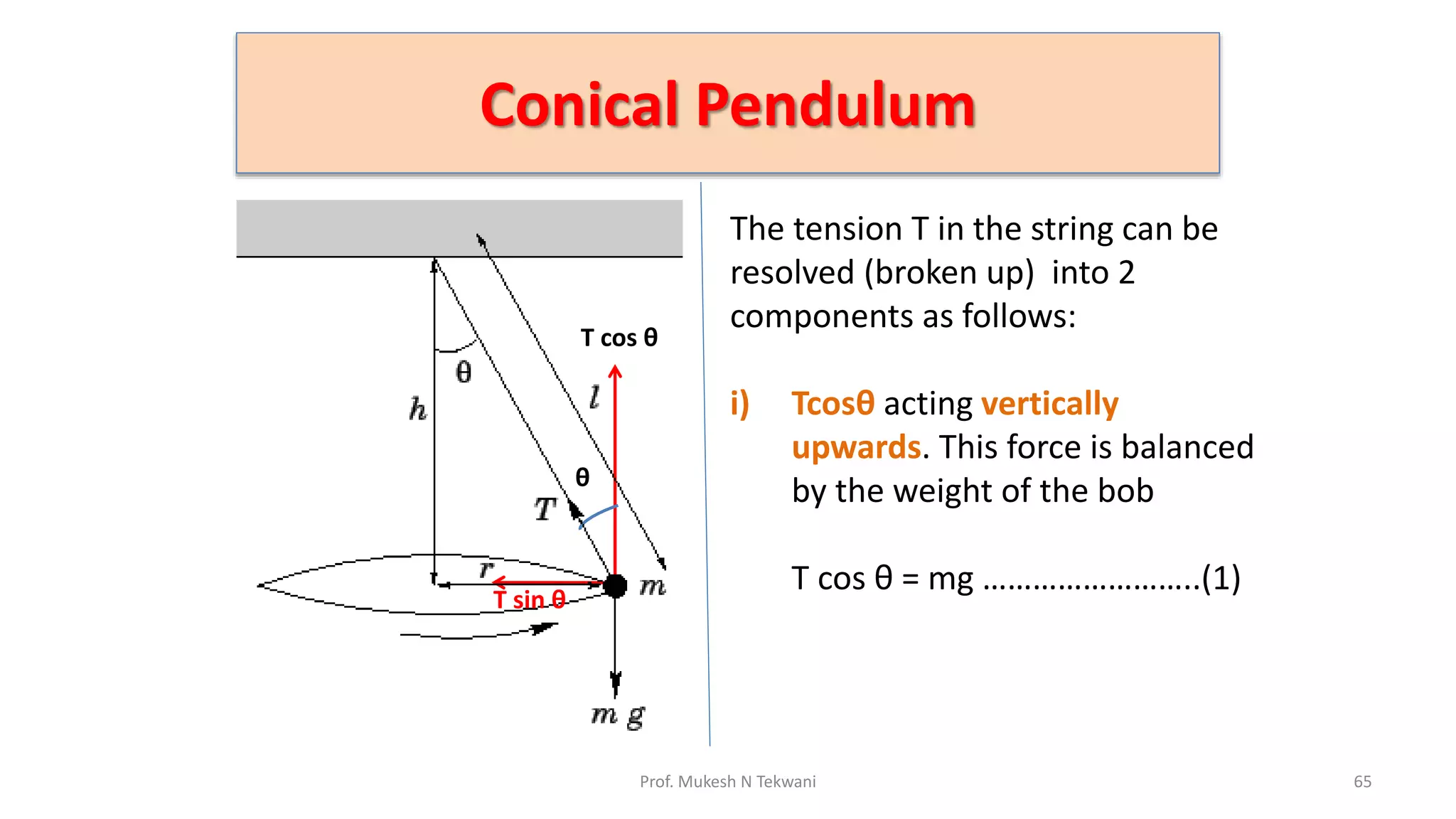

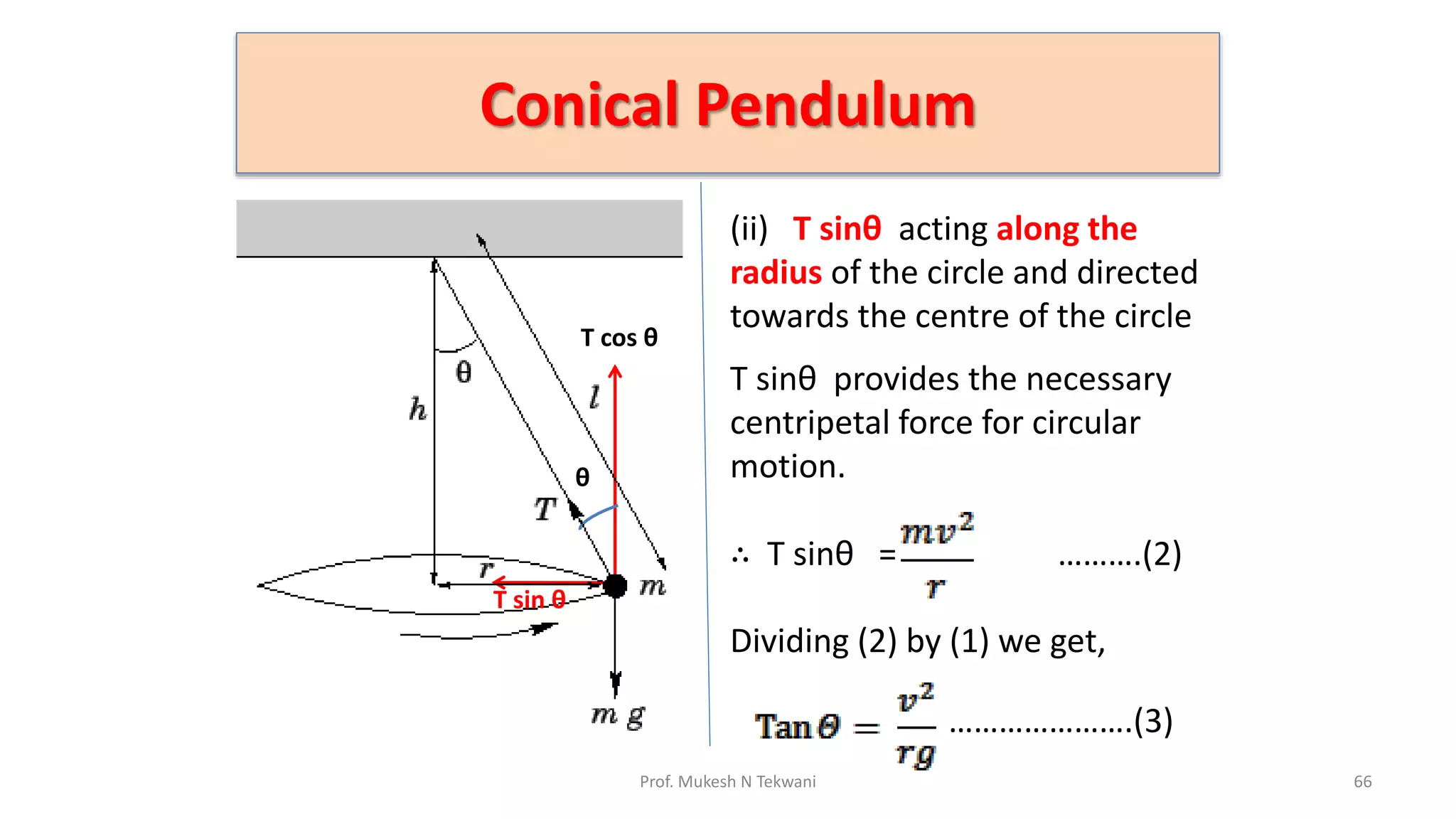

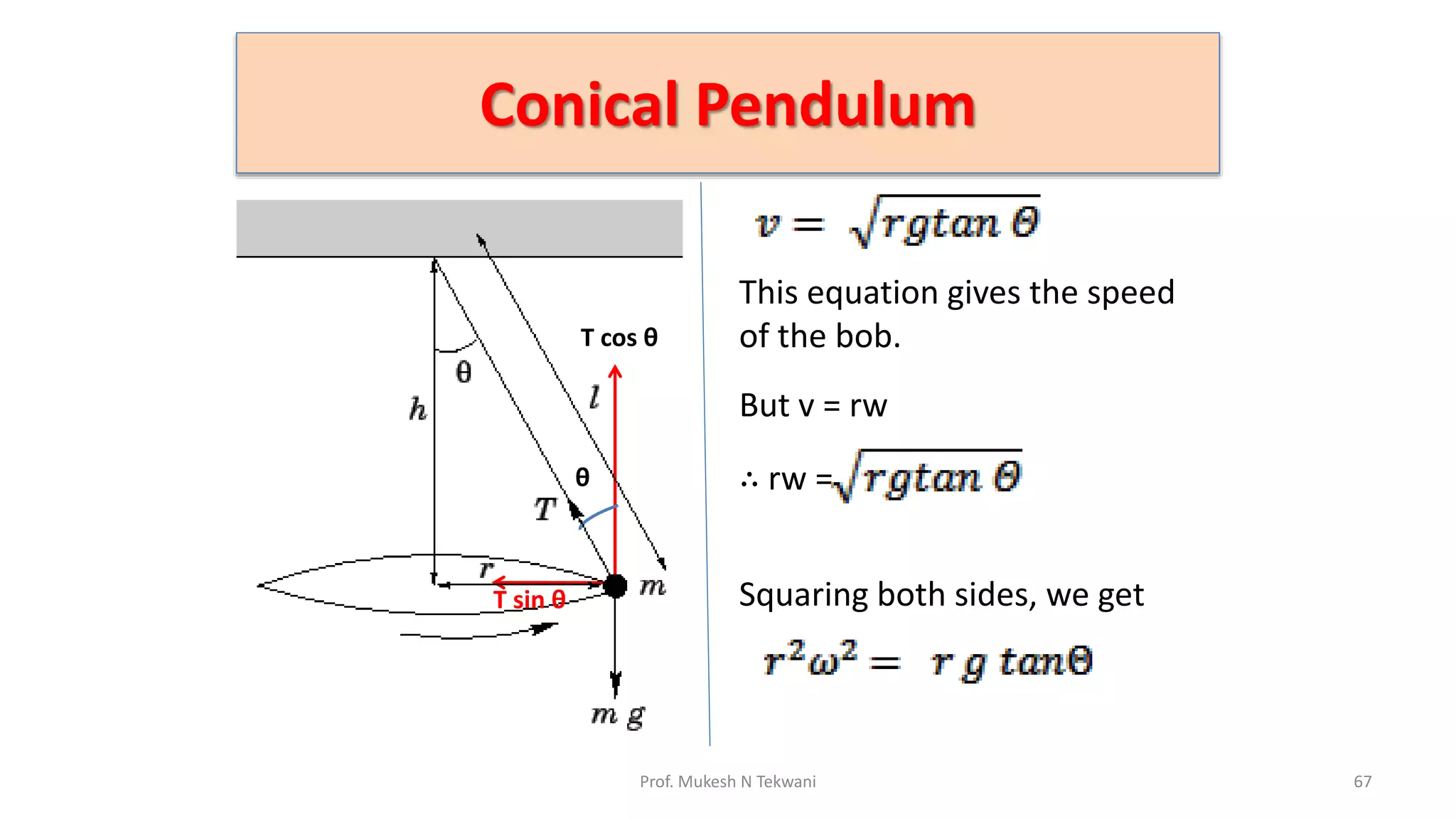

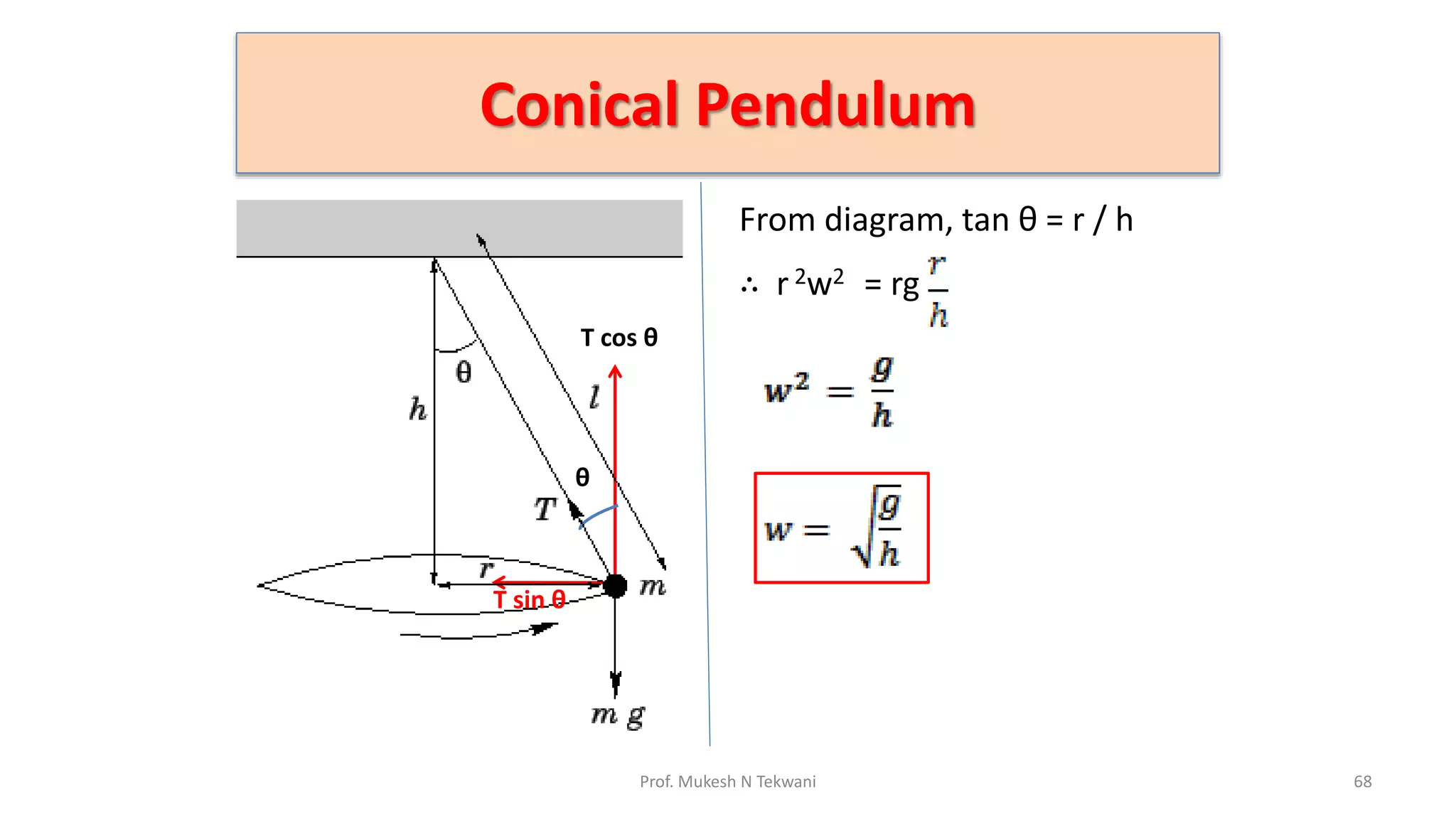

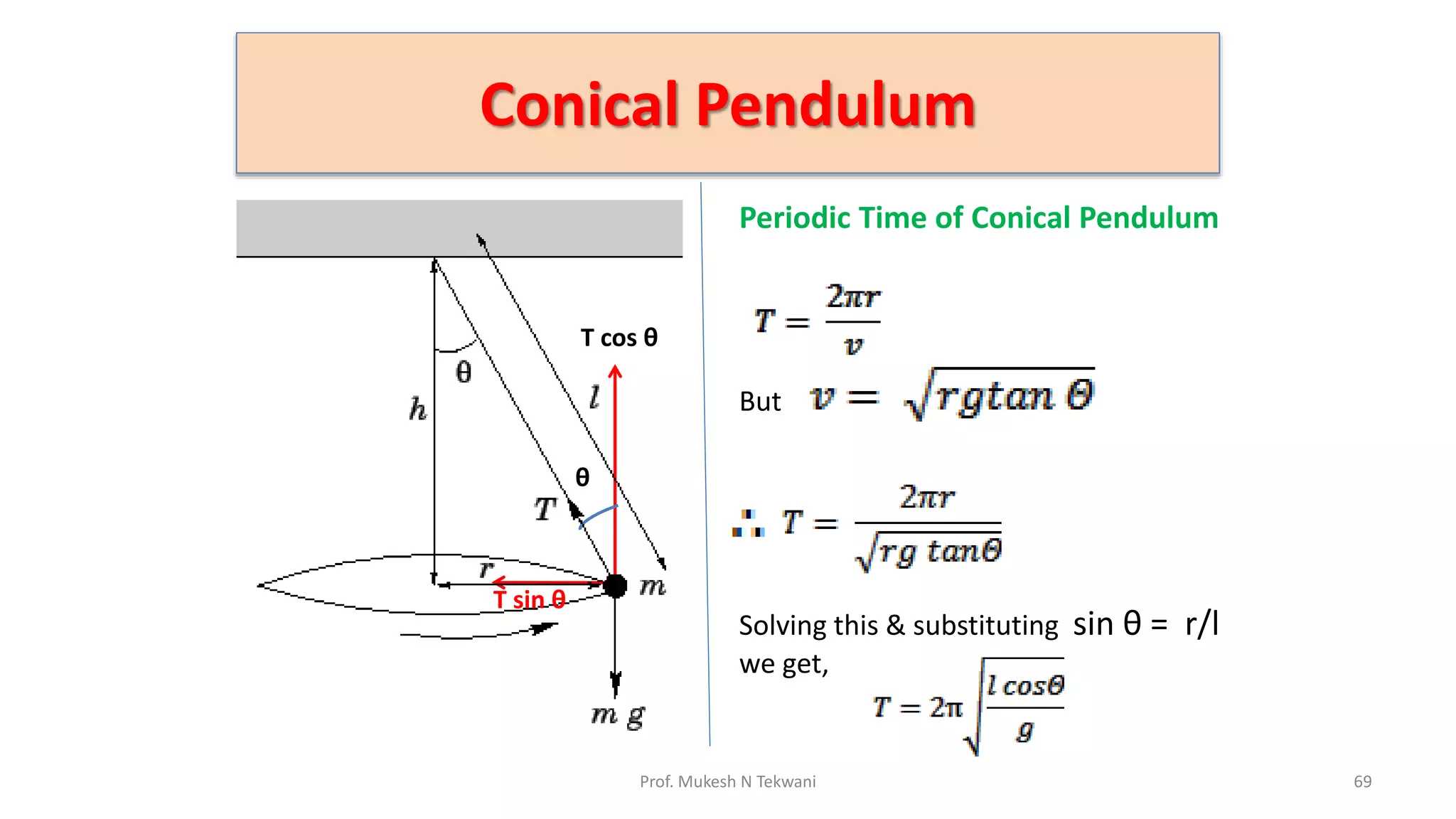

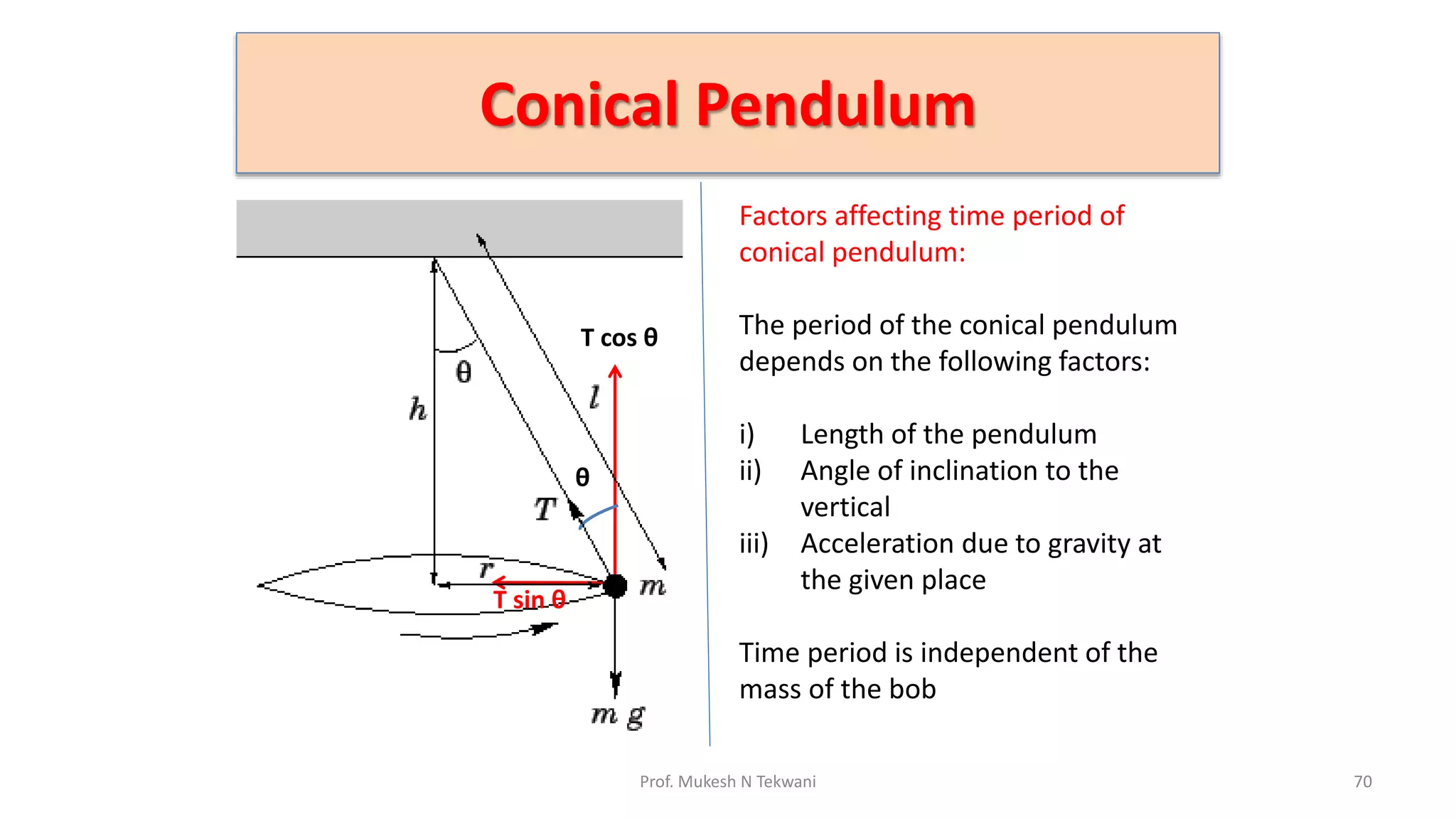

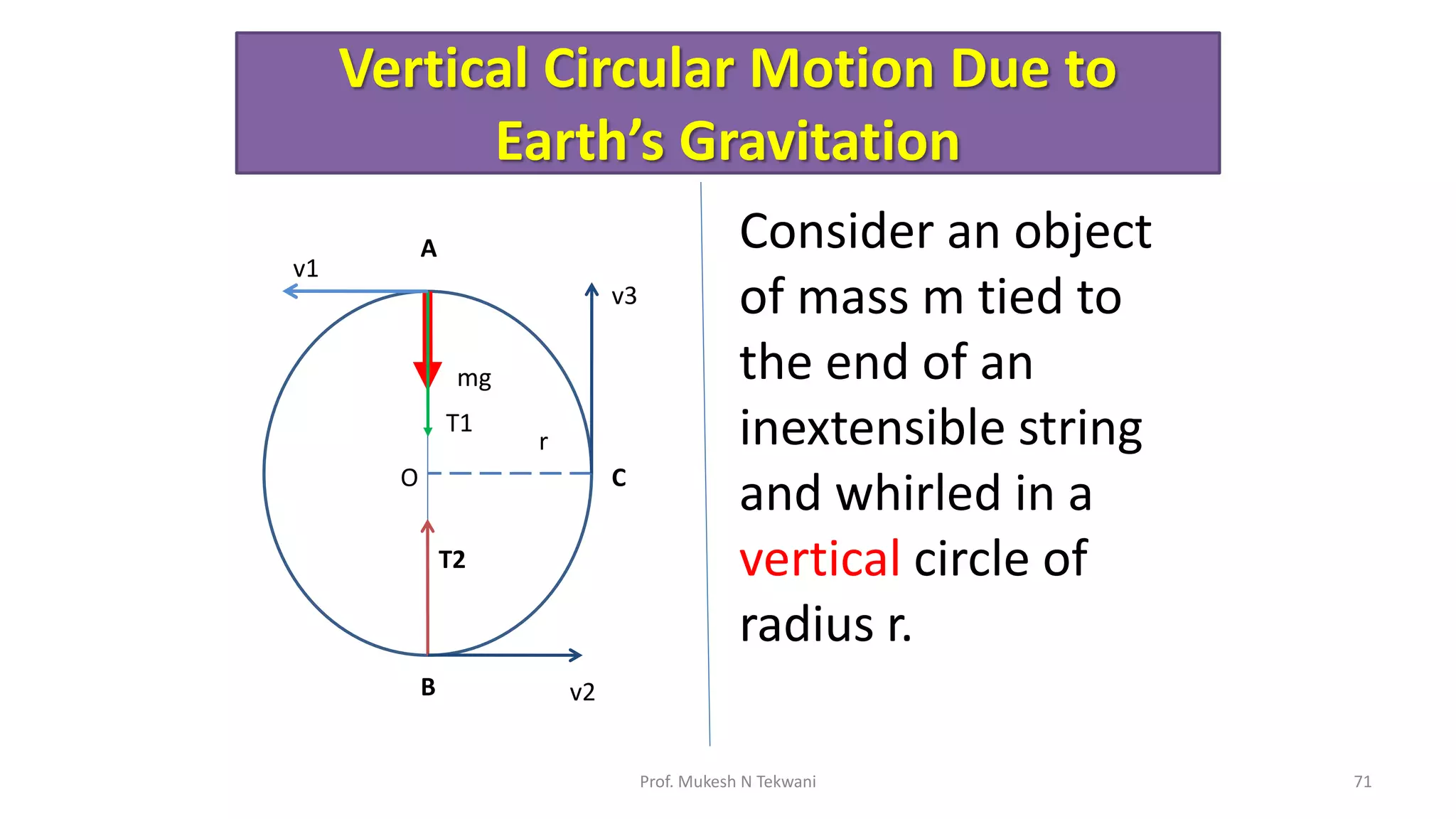

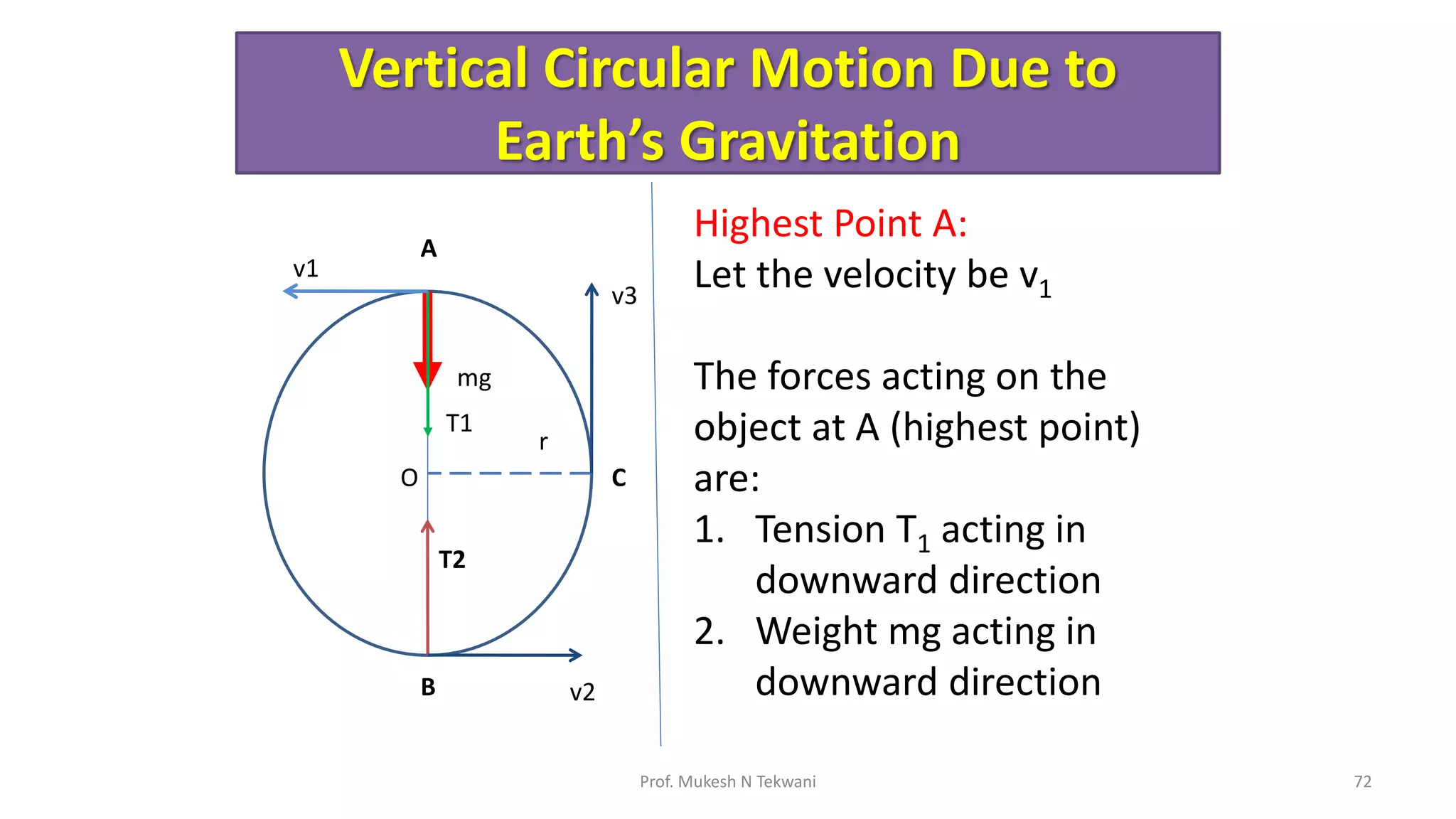

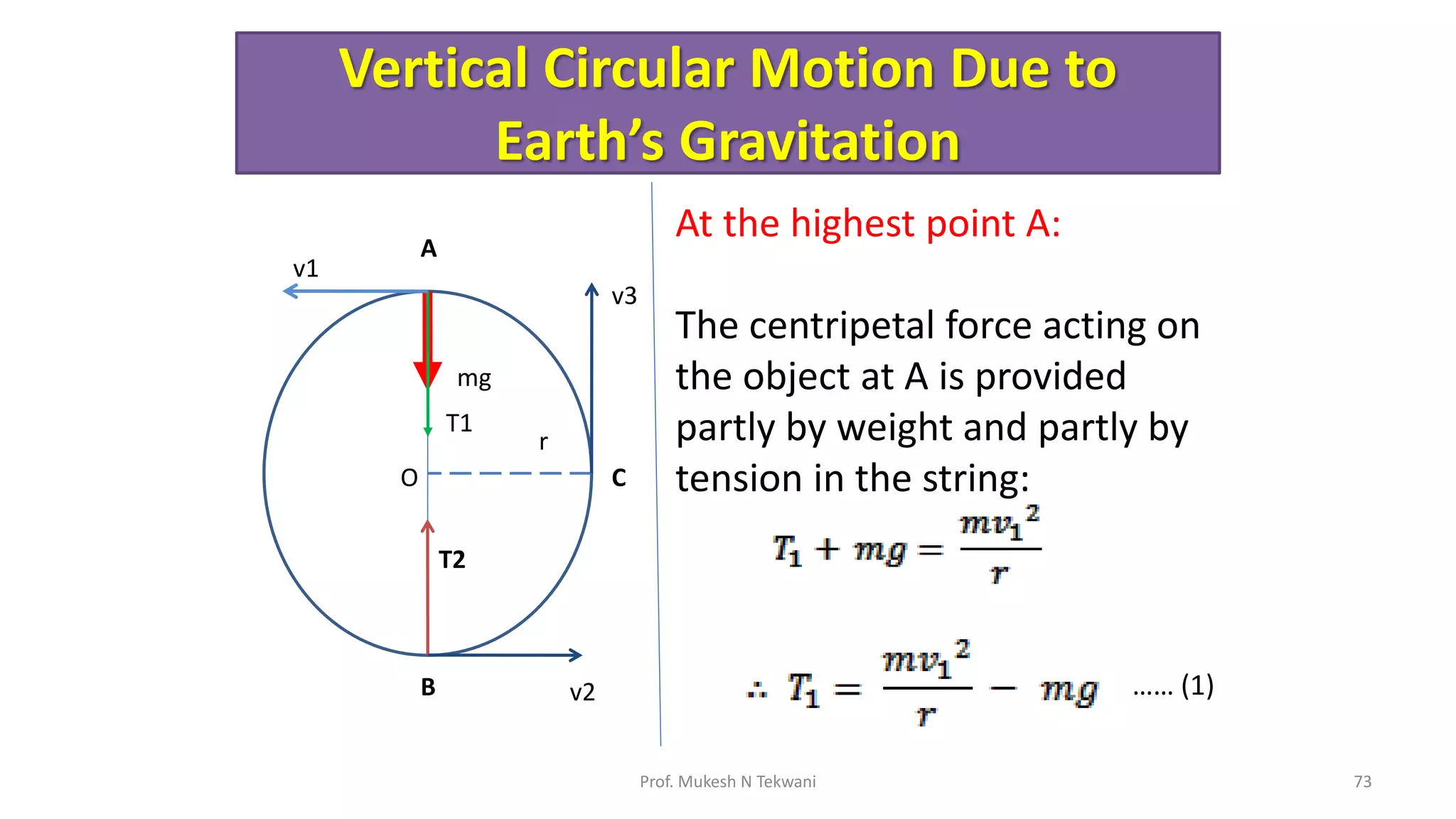

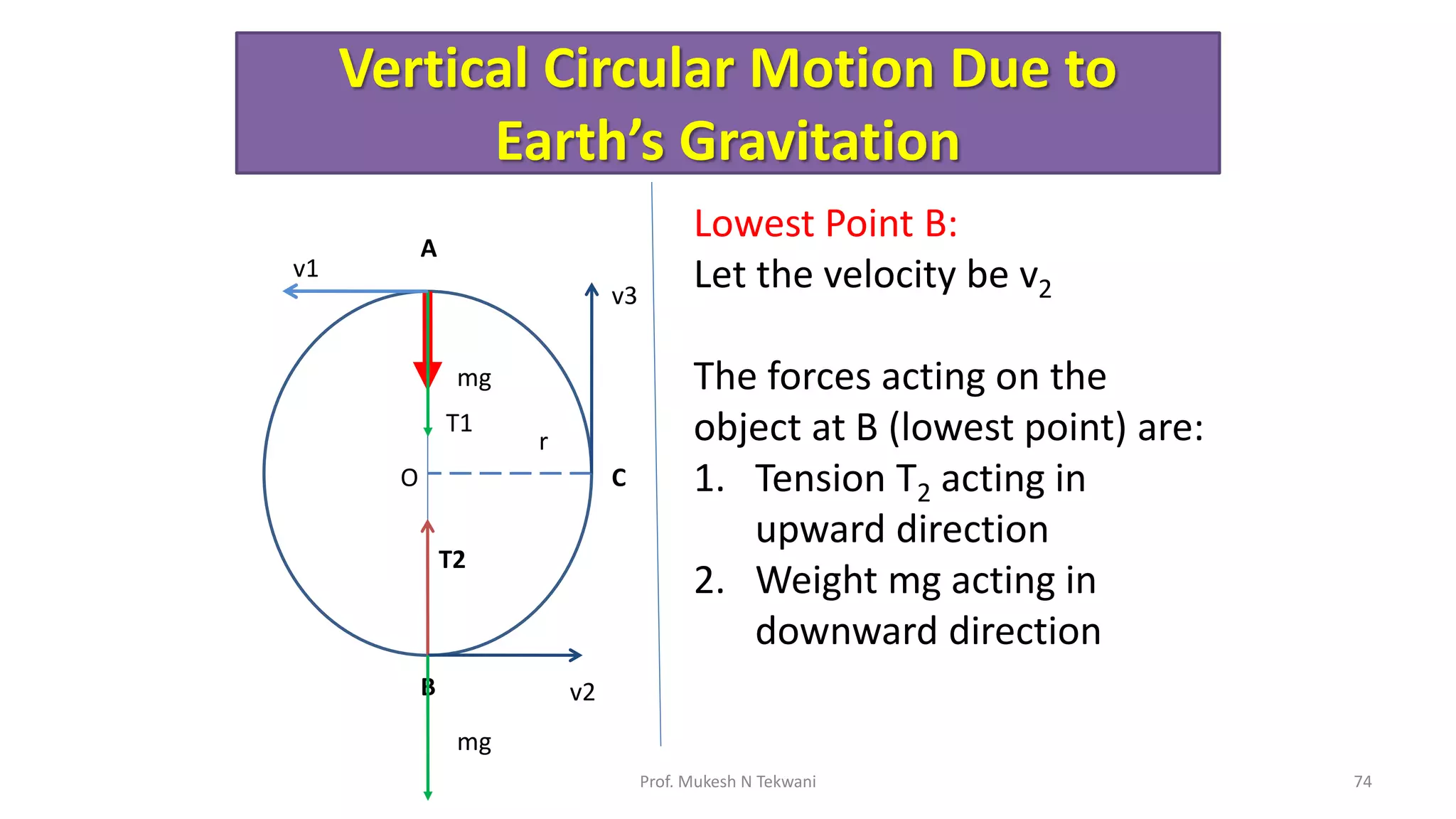

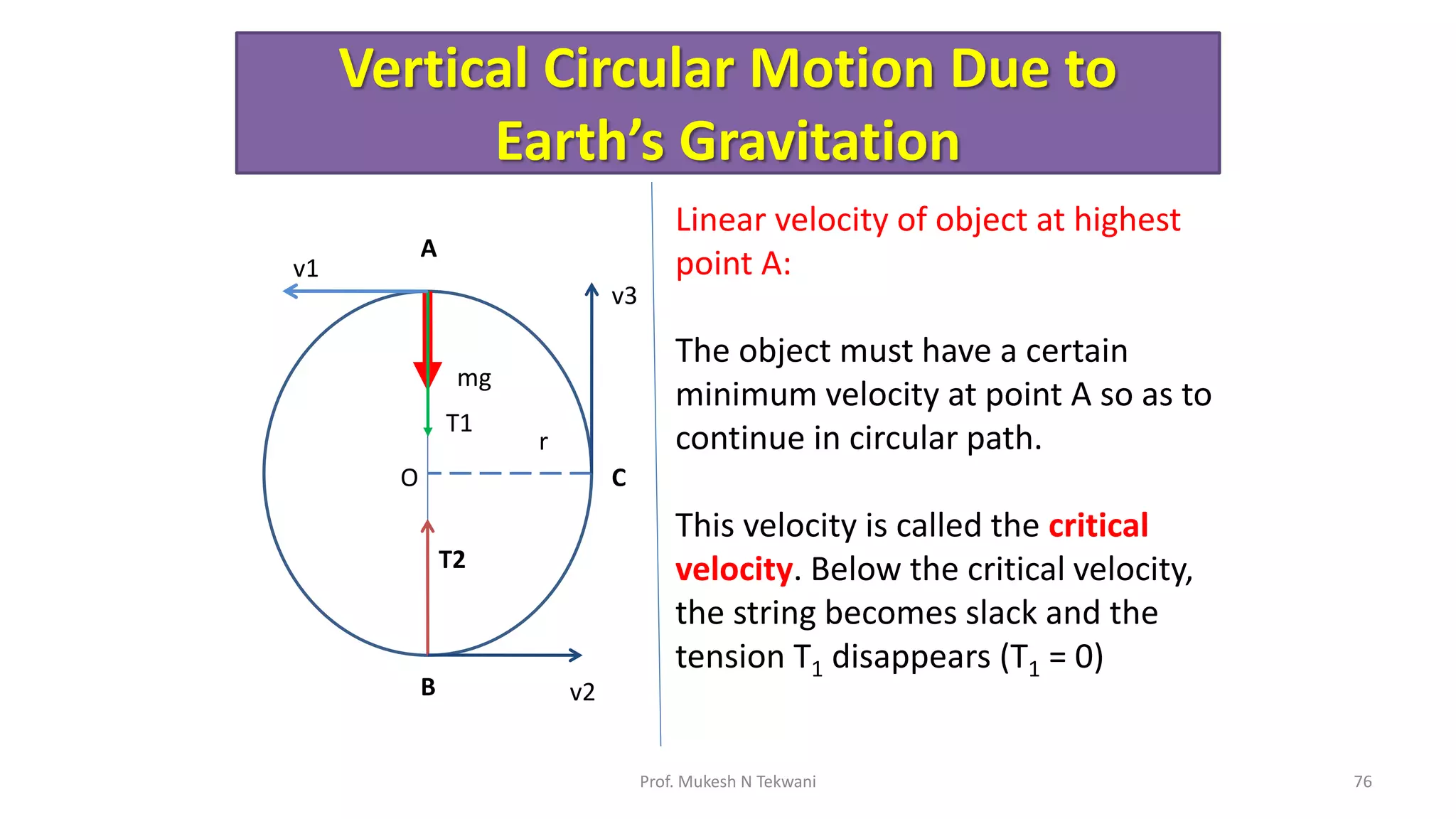

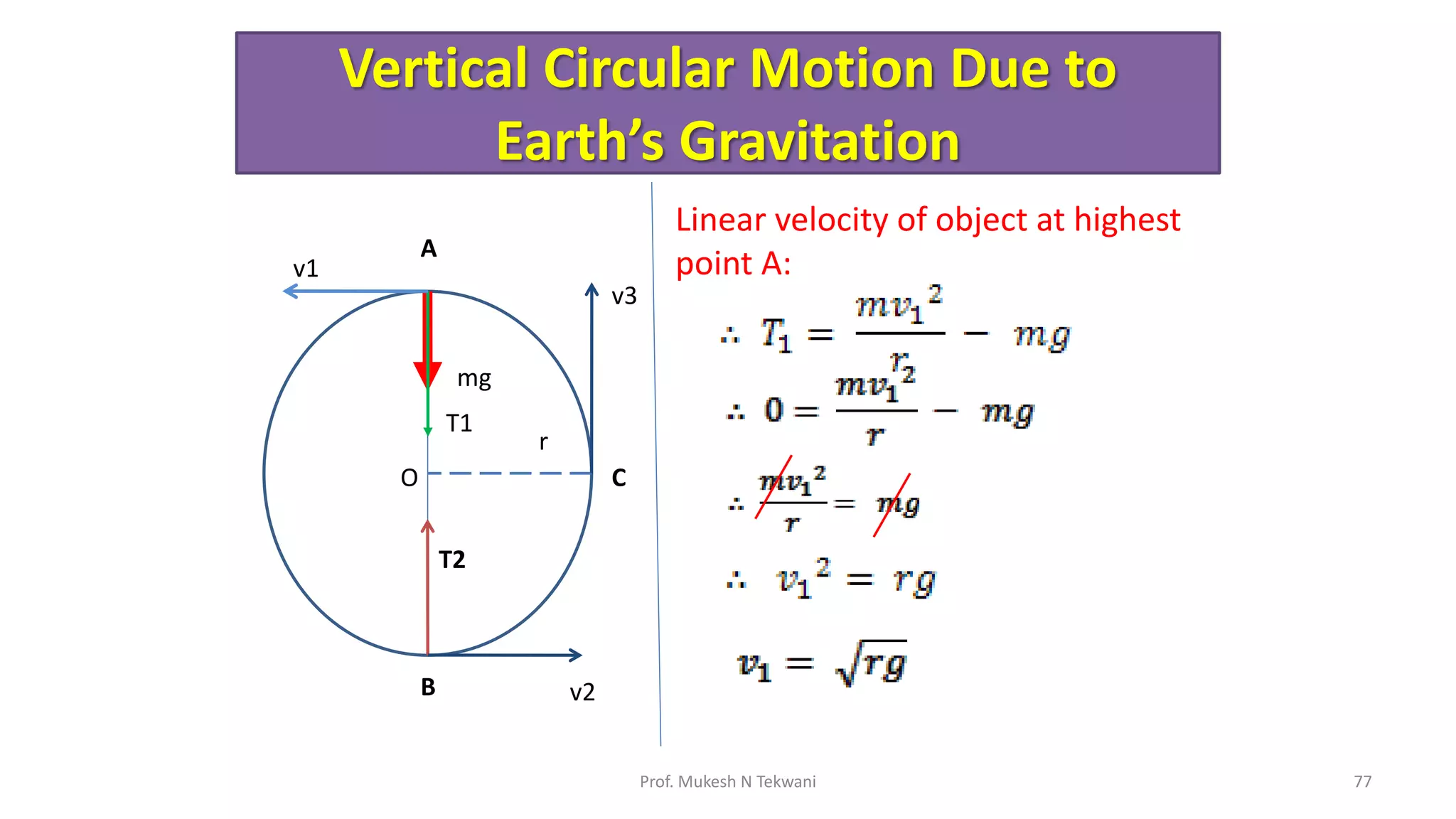

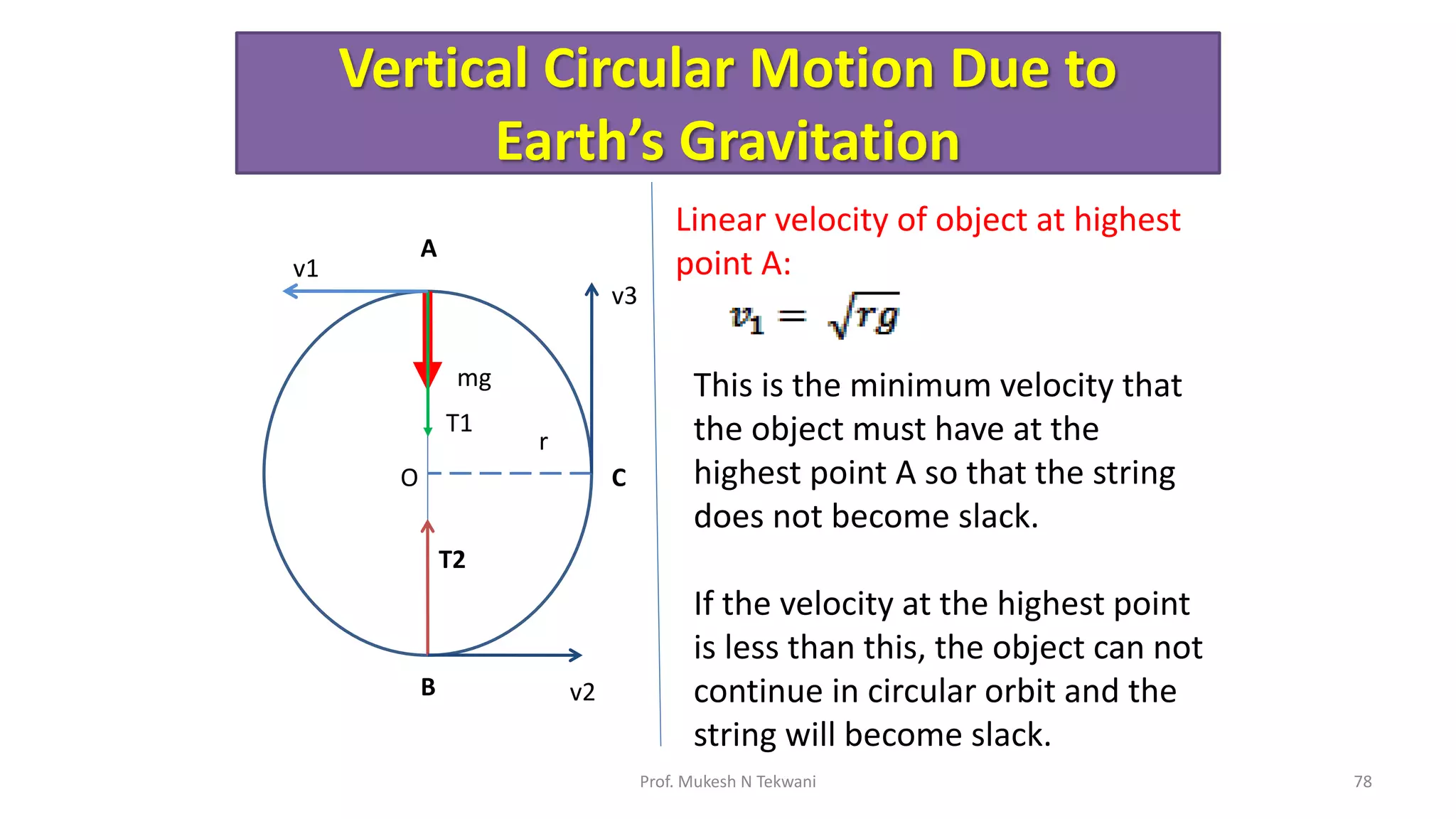

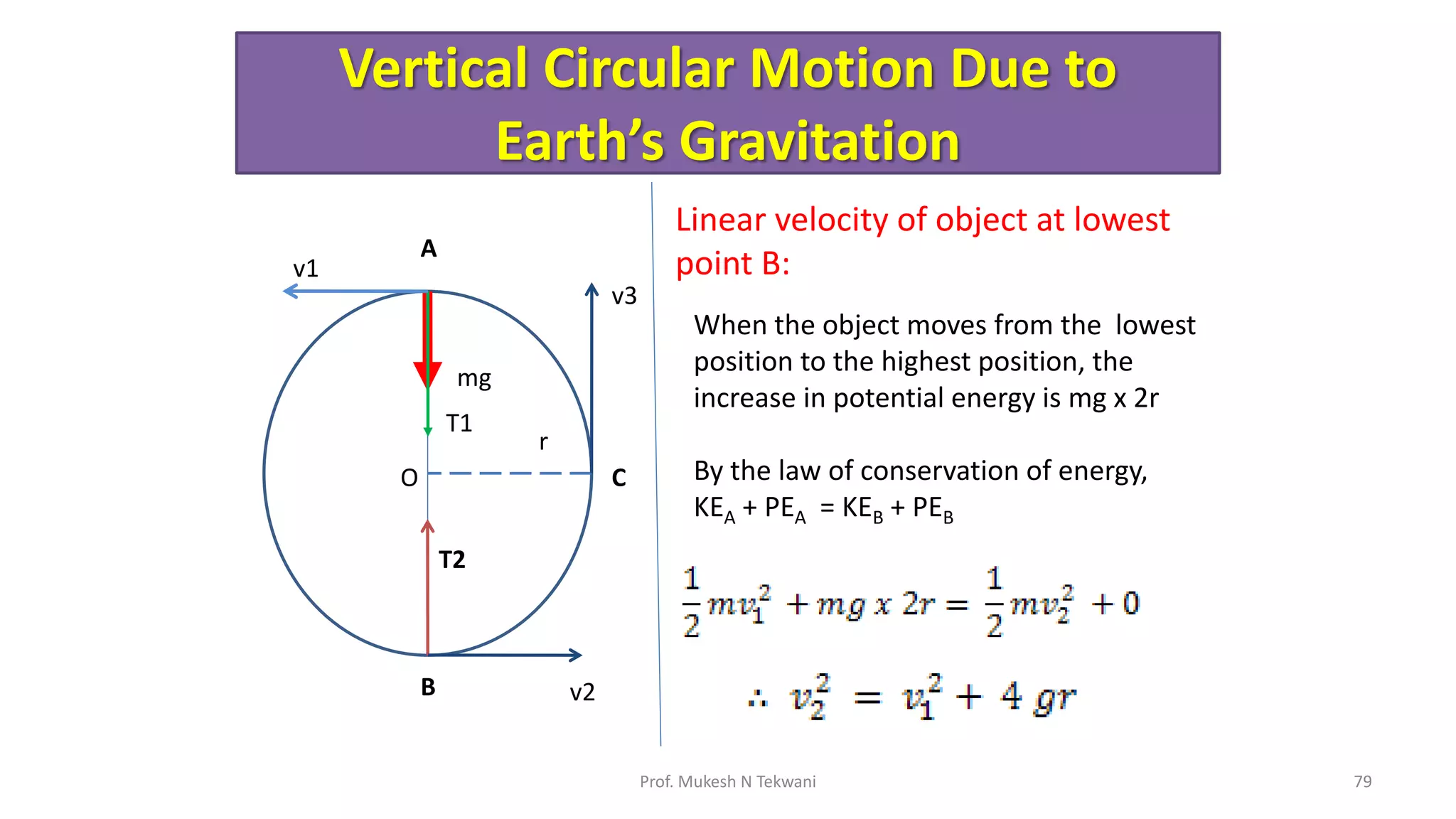

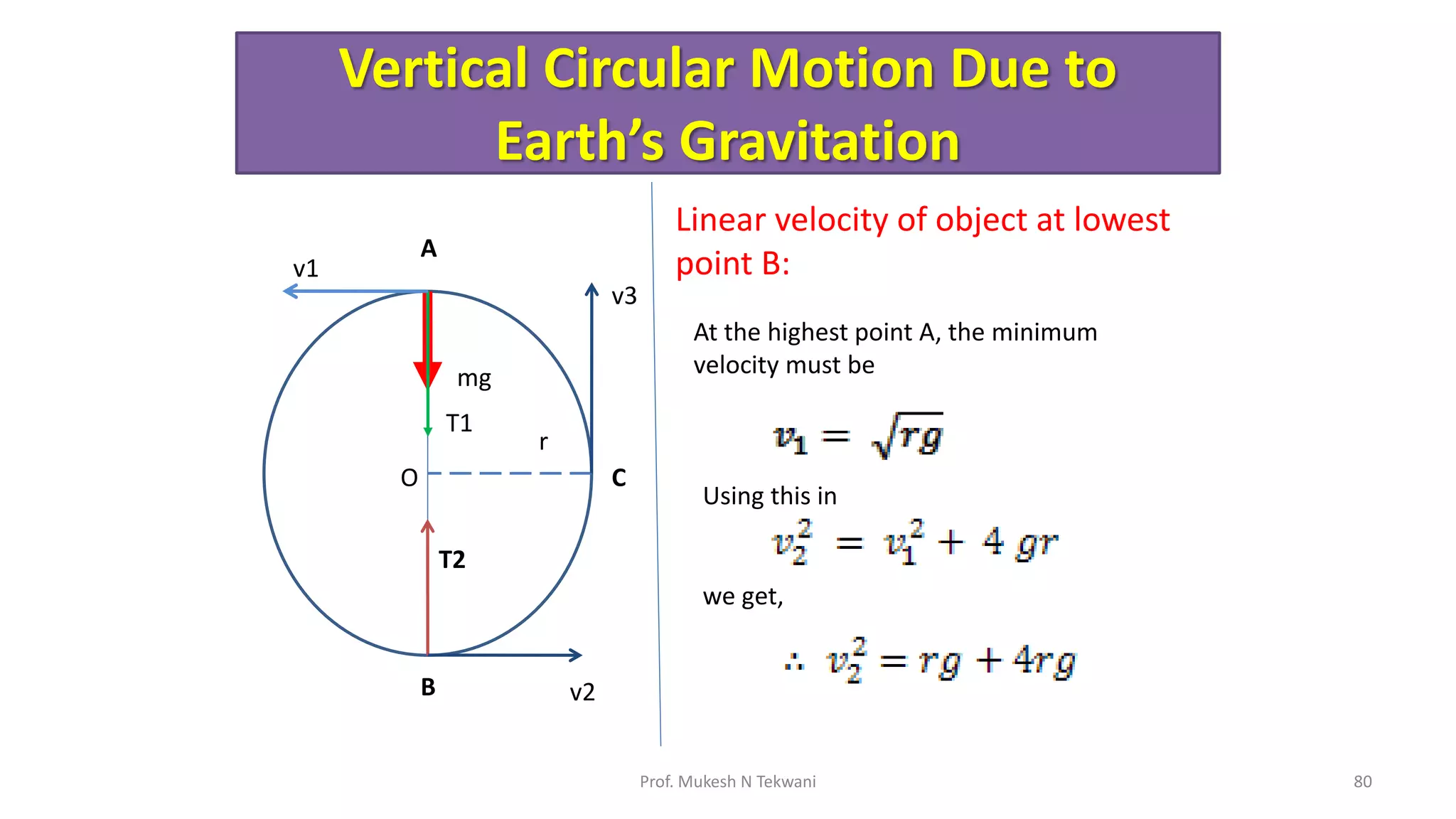

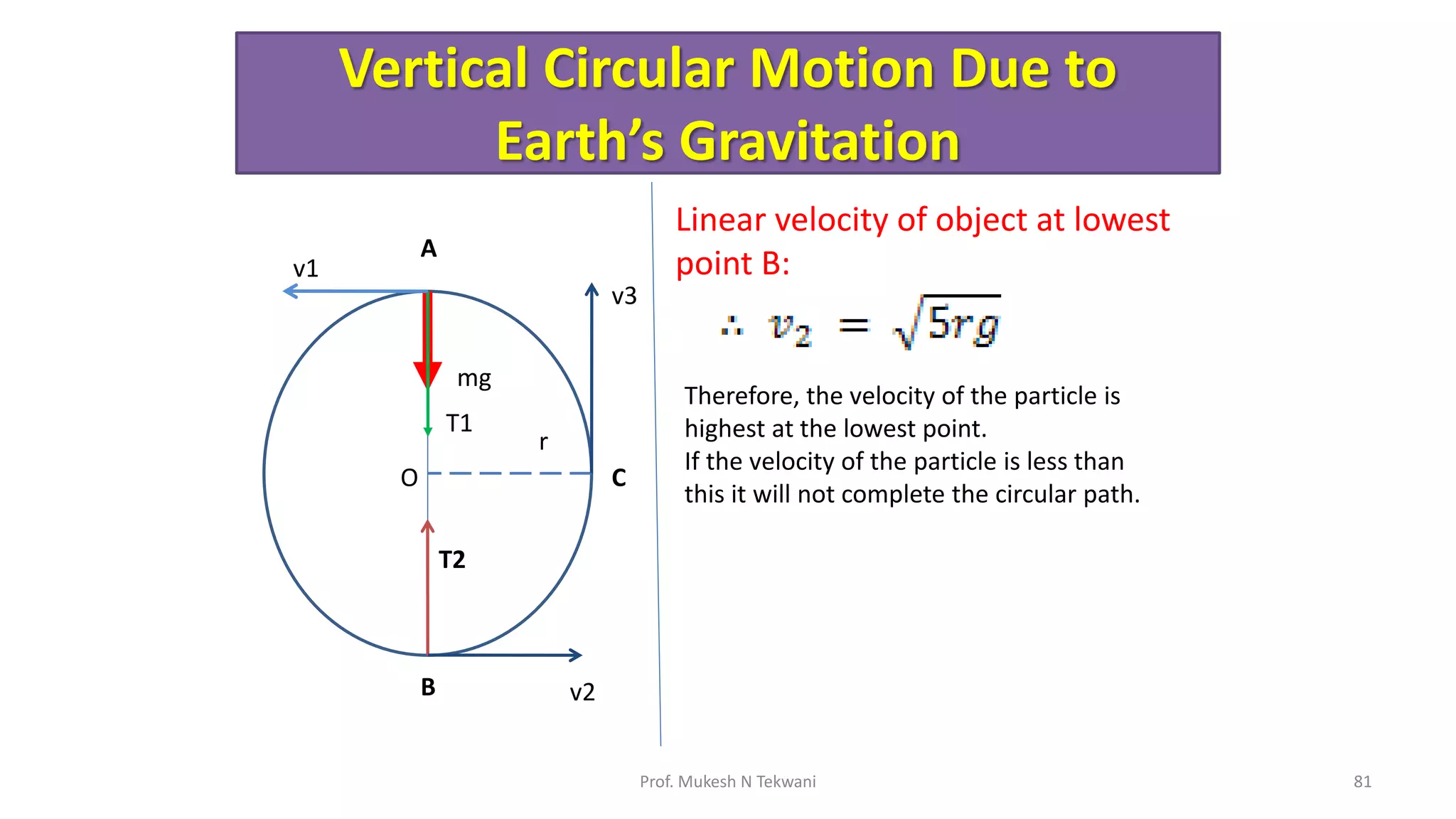

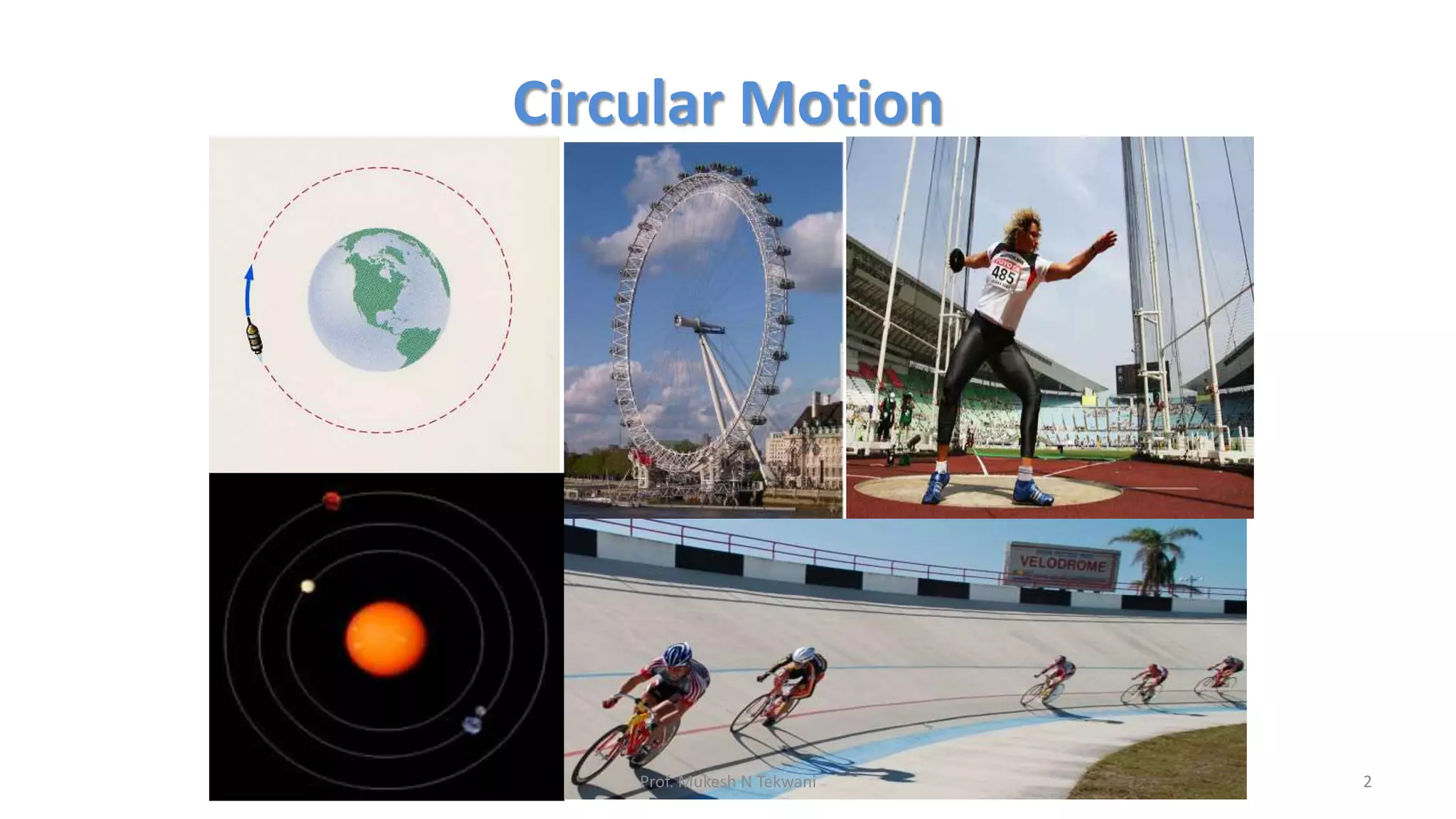

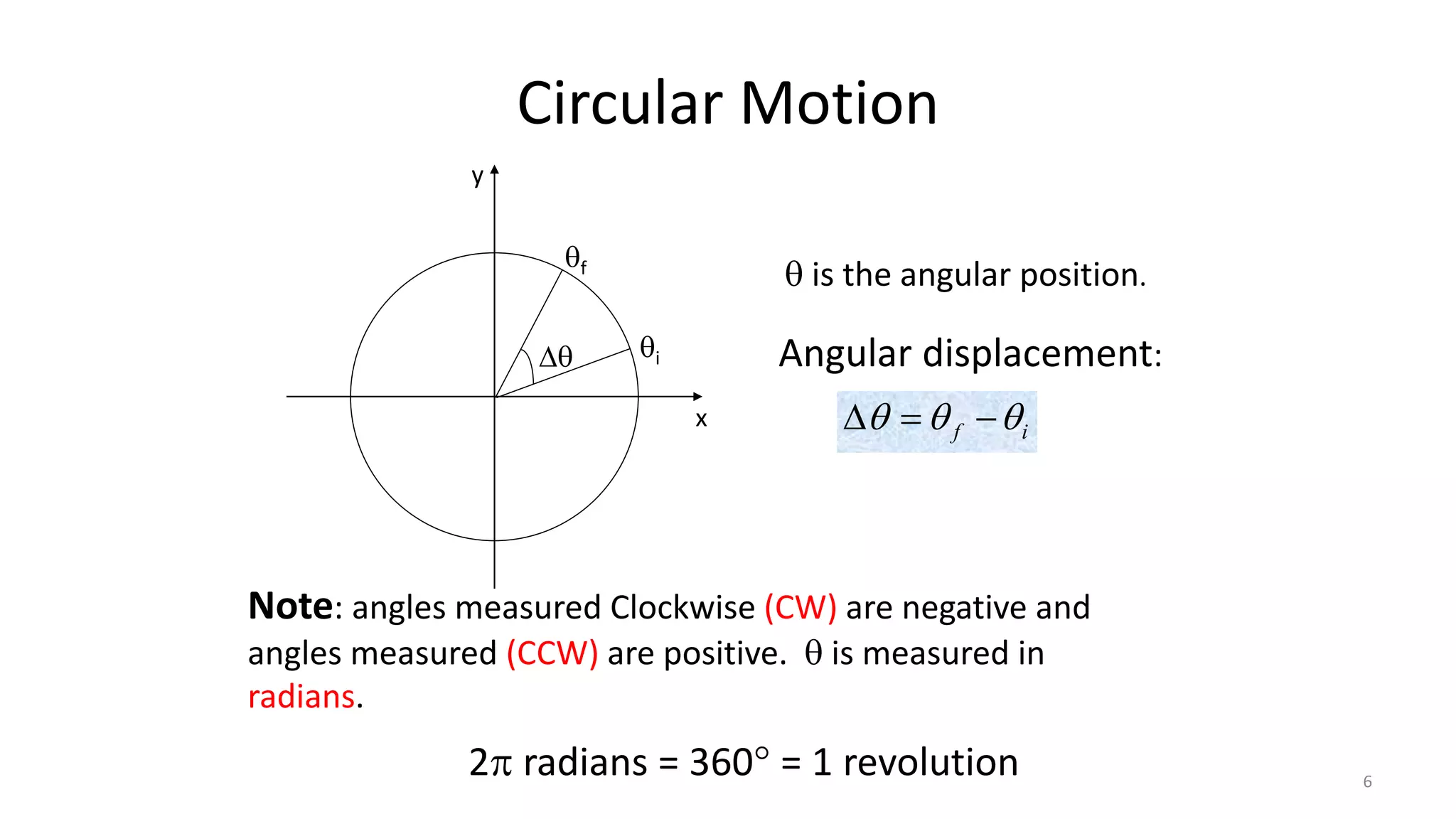

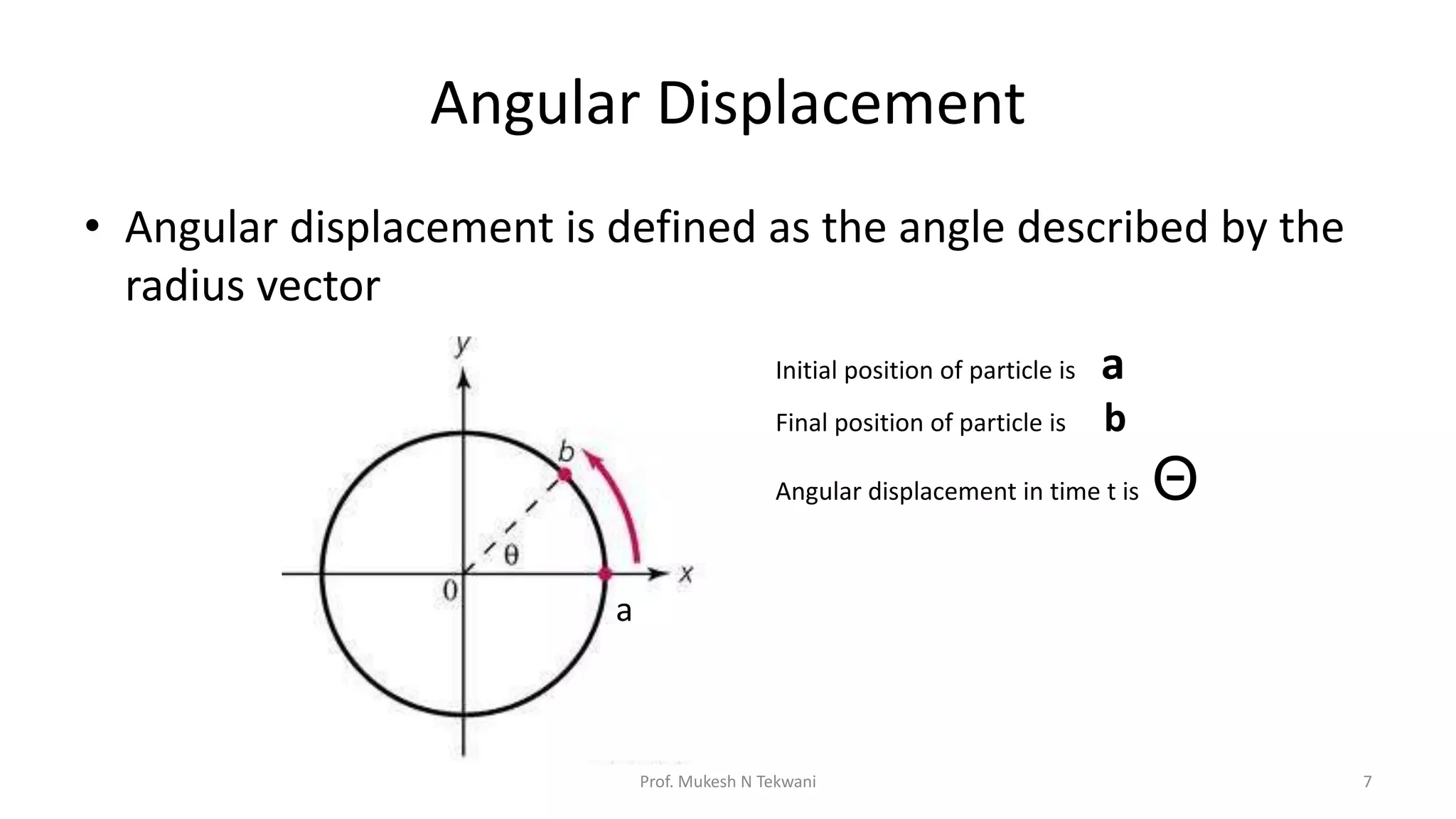

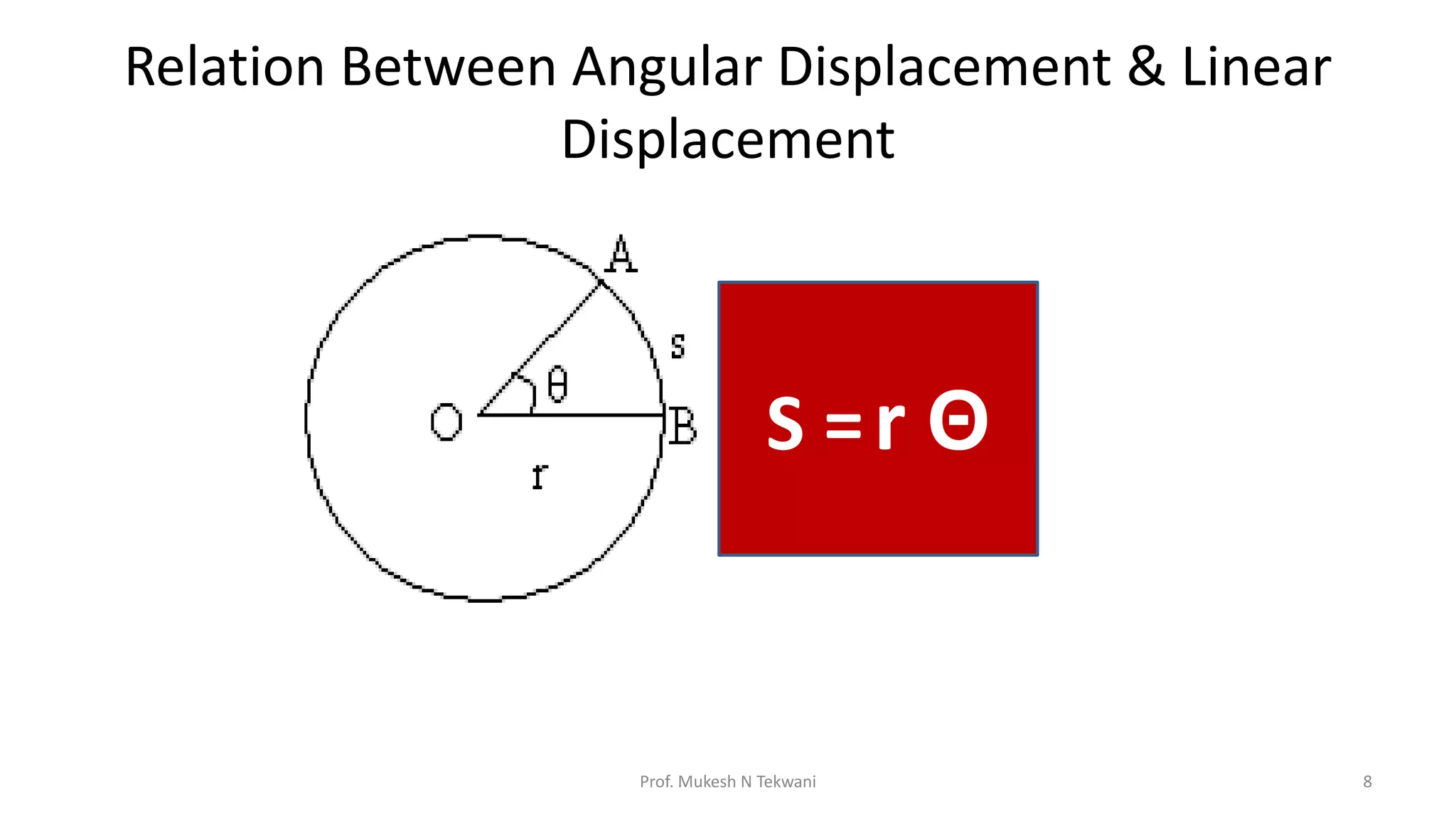

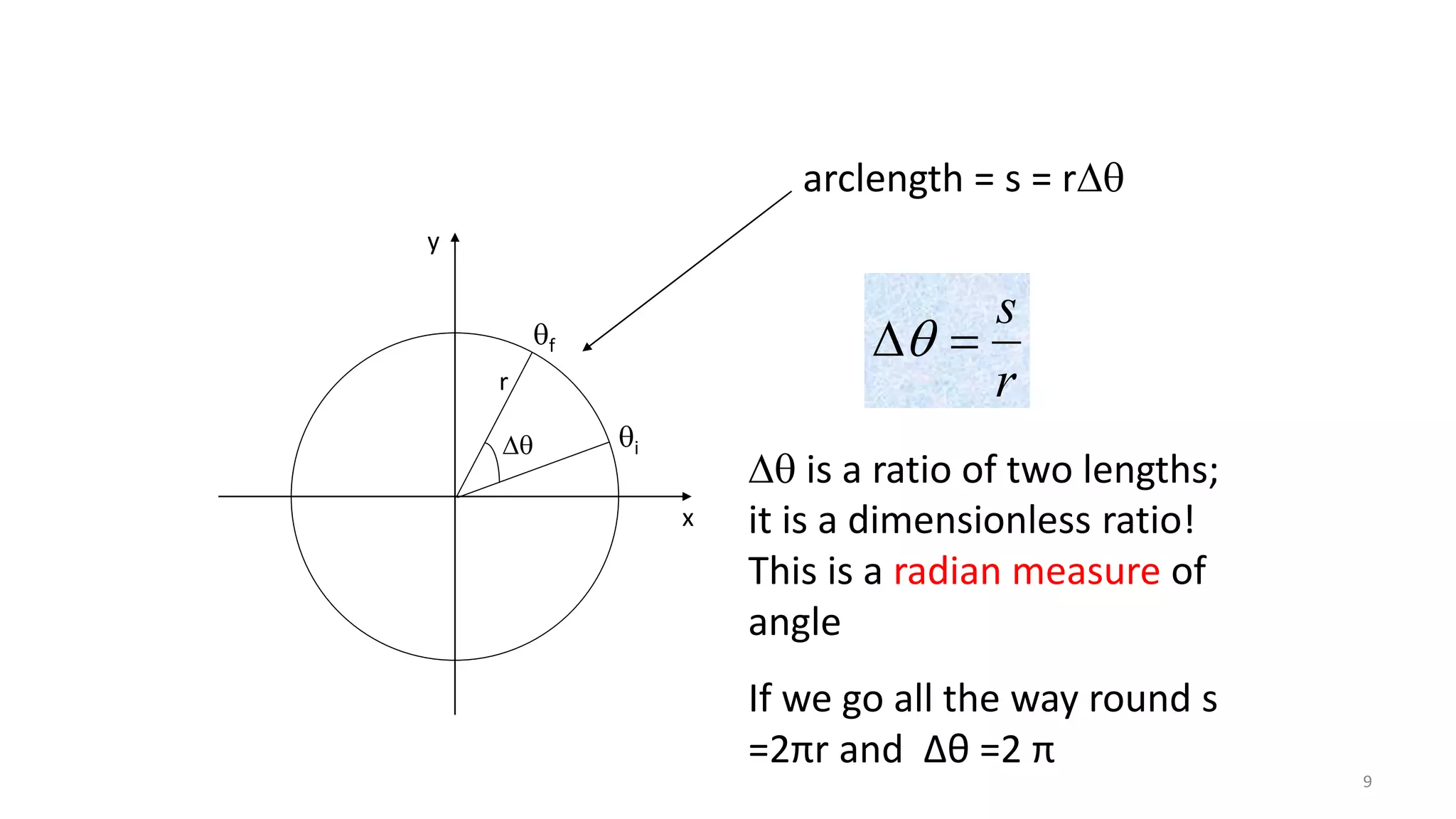

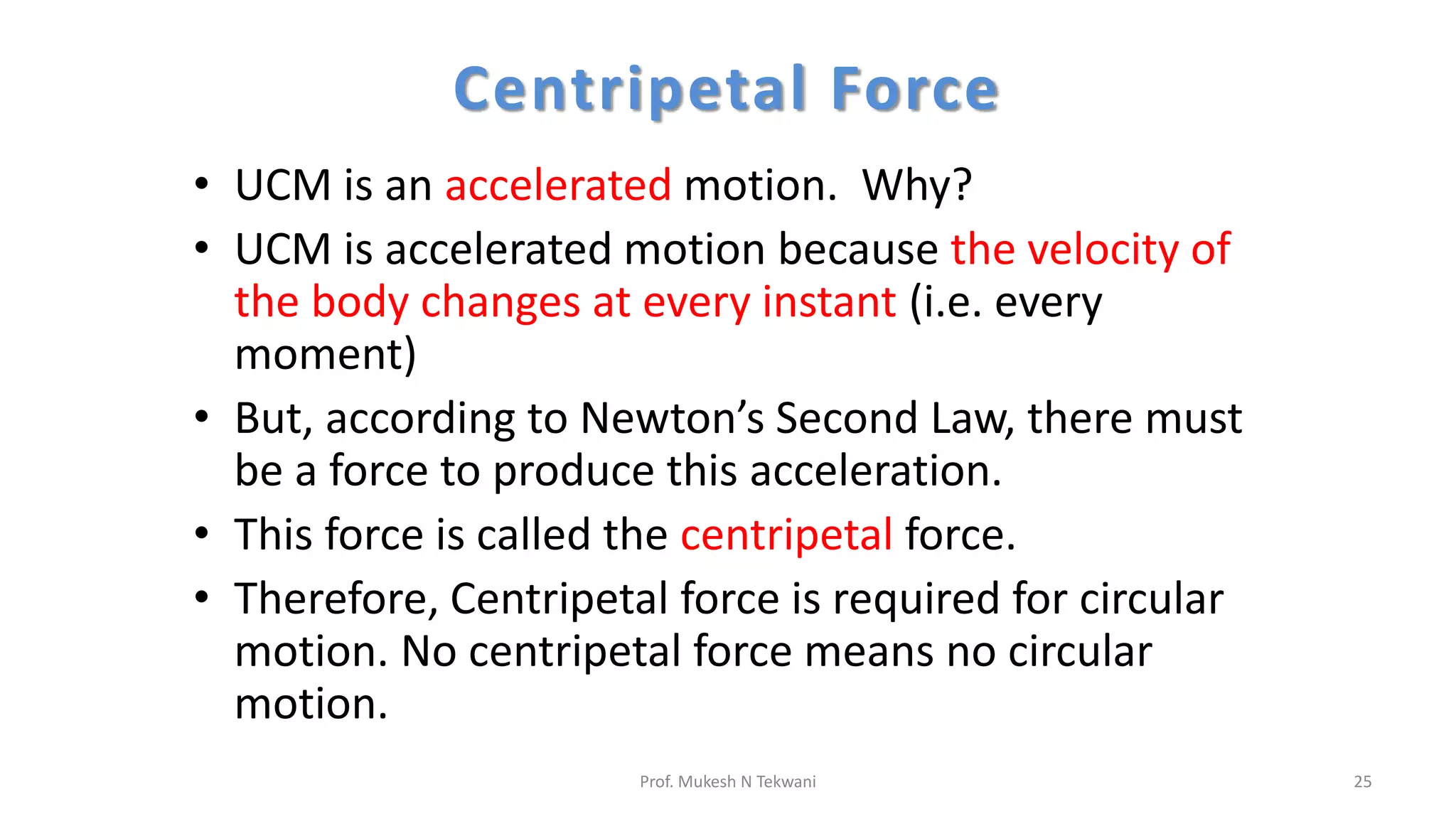

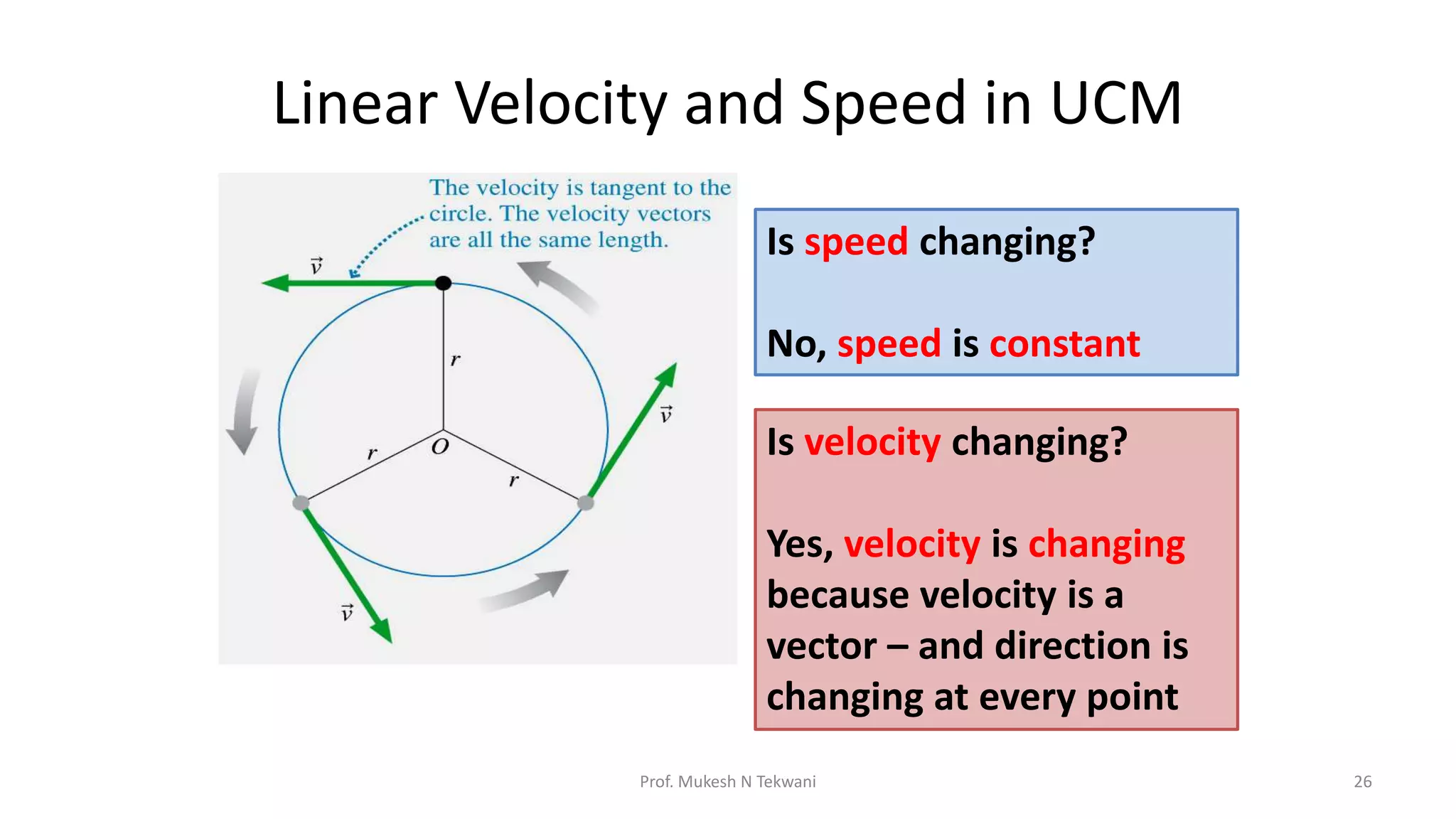

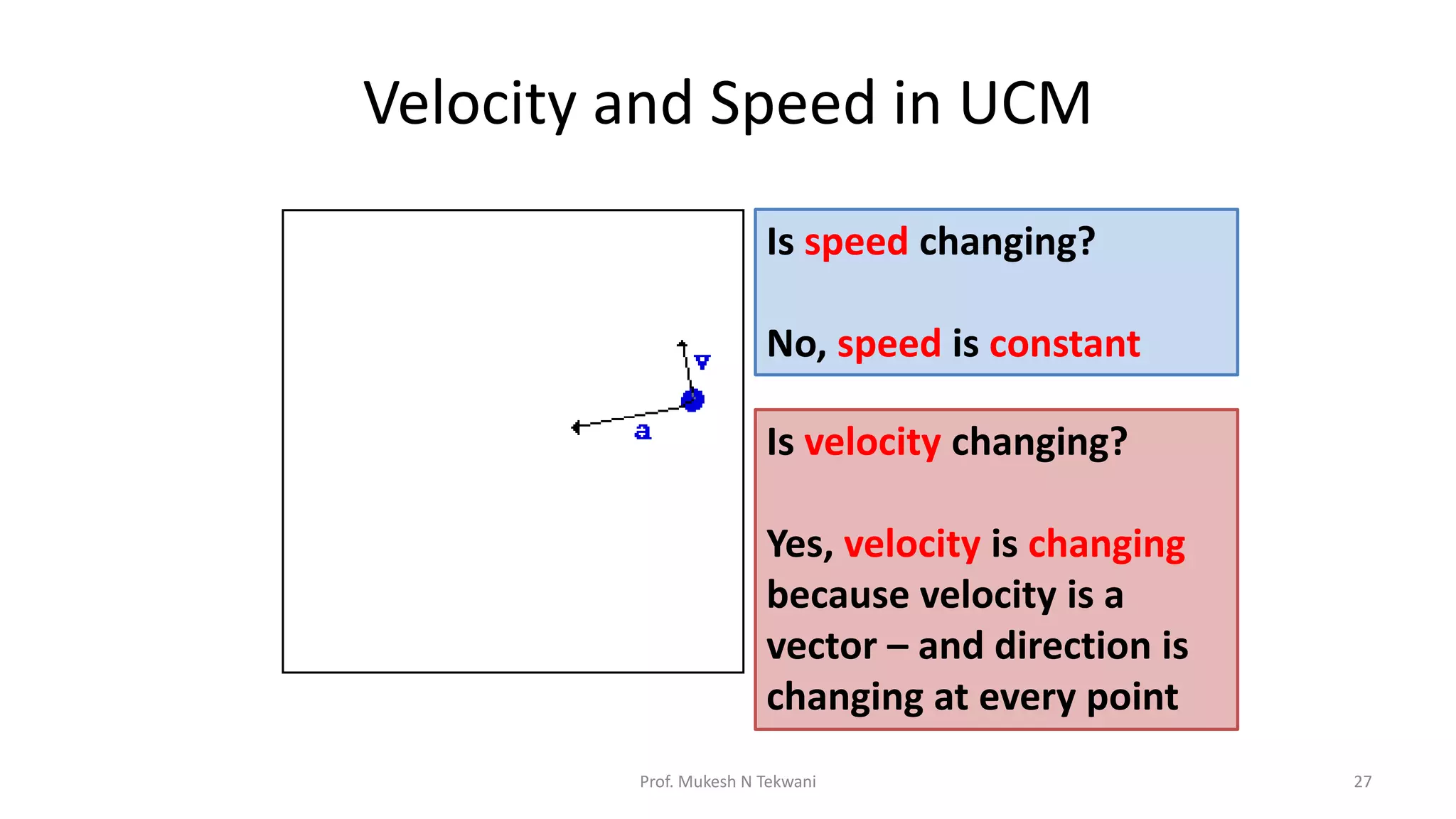

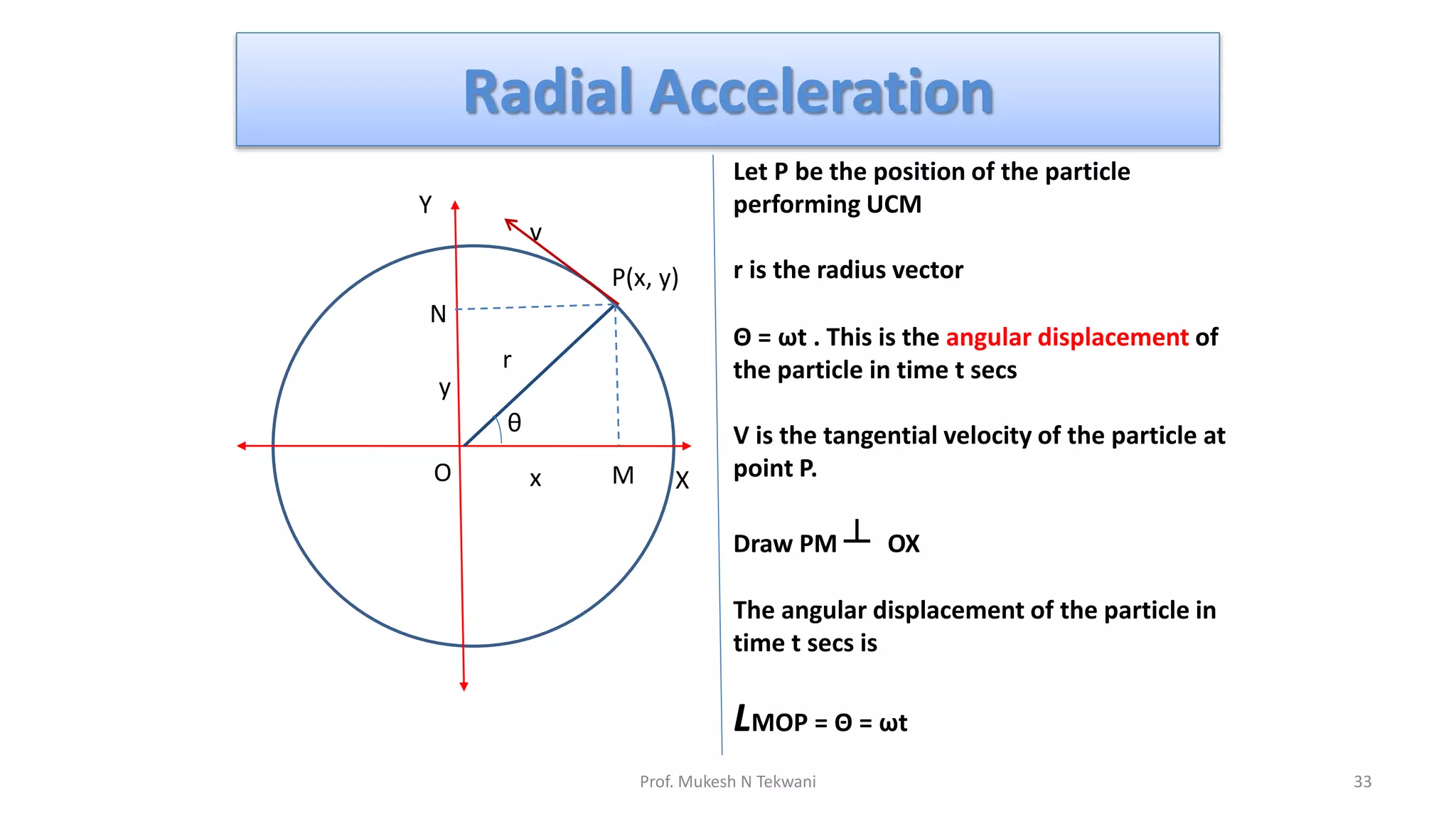

The document discusses circular motion and its applications, including the motion of planets, electrons, and vehicles. It defines angular displacement, centripetal force, and the importance of banking of roads for safe circular motion. Additionally, it covers concepts like conical pendulums and the effects of gravity on vertical circular motion.

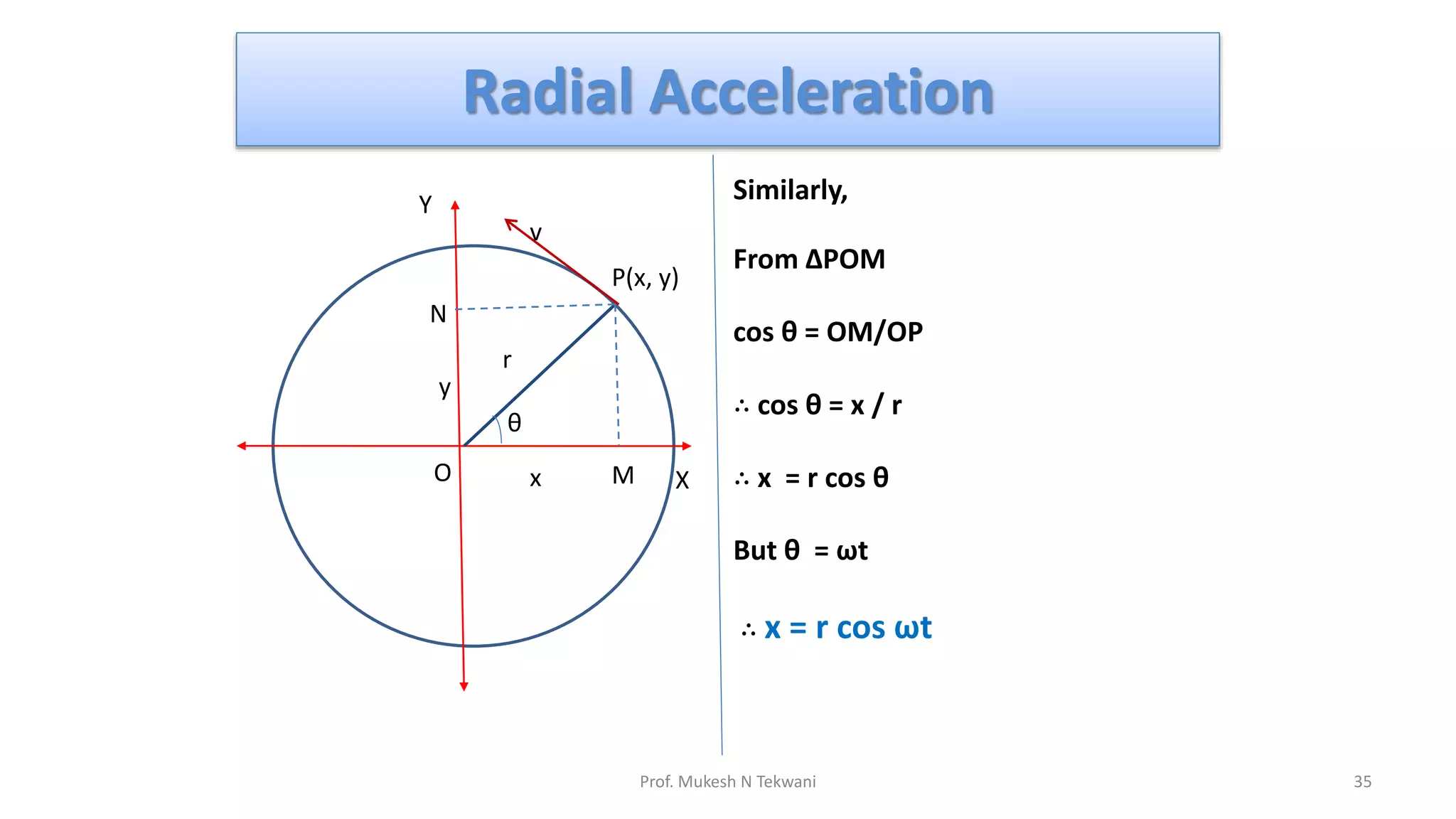

![Radial Acceleration

36

Prof. Mukesh N Tekwani

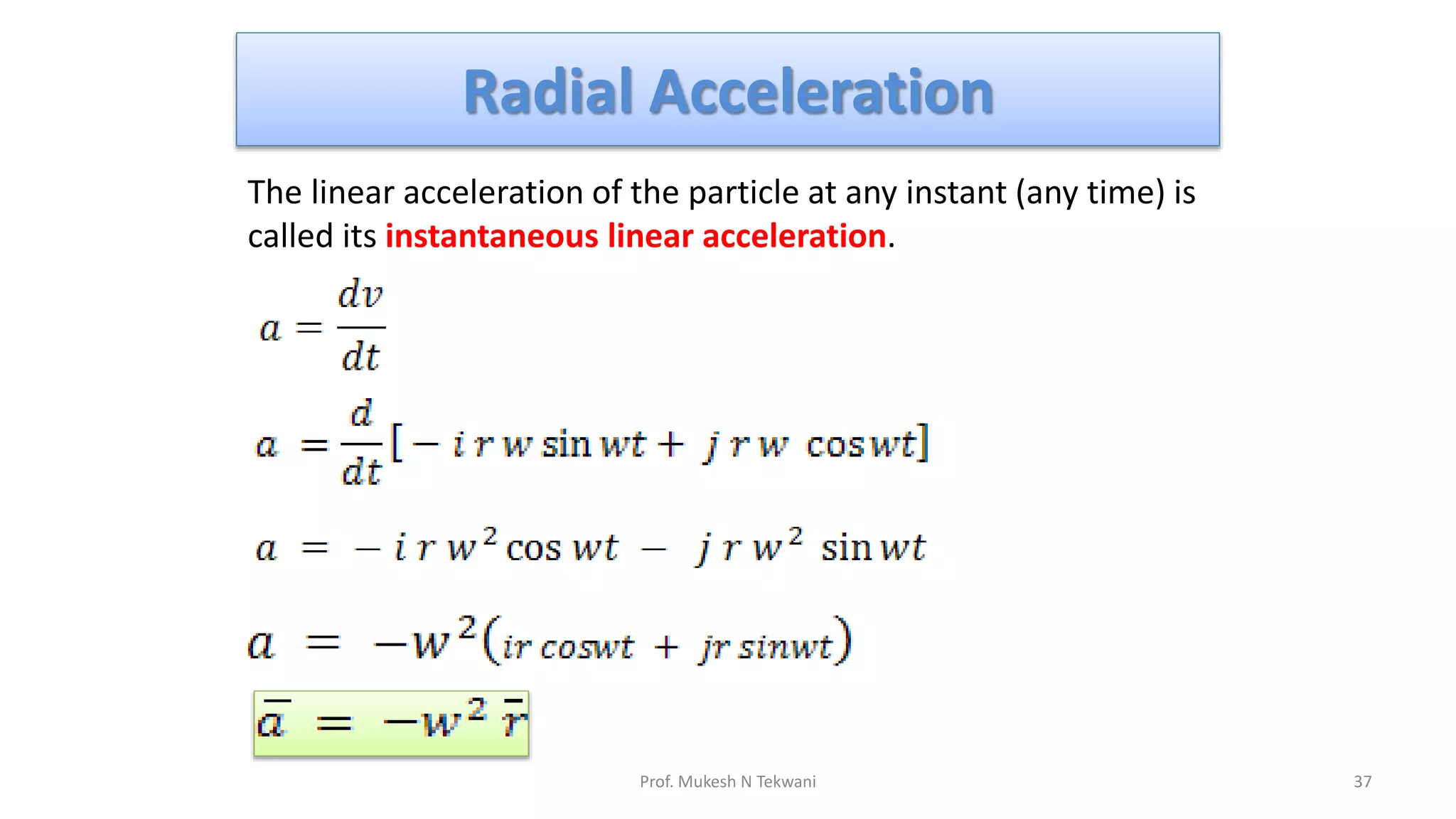

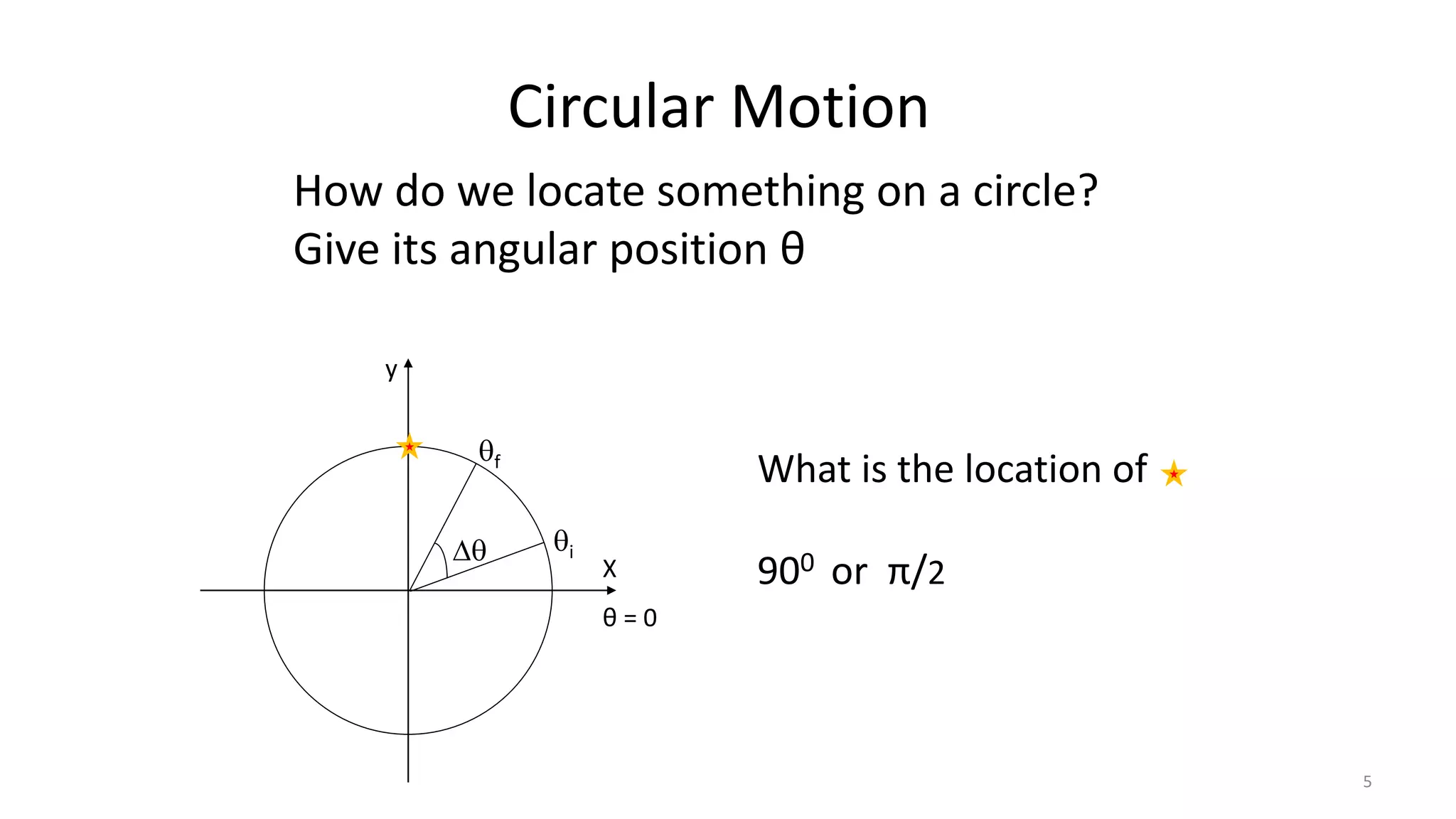

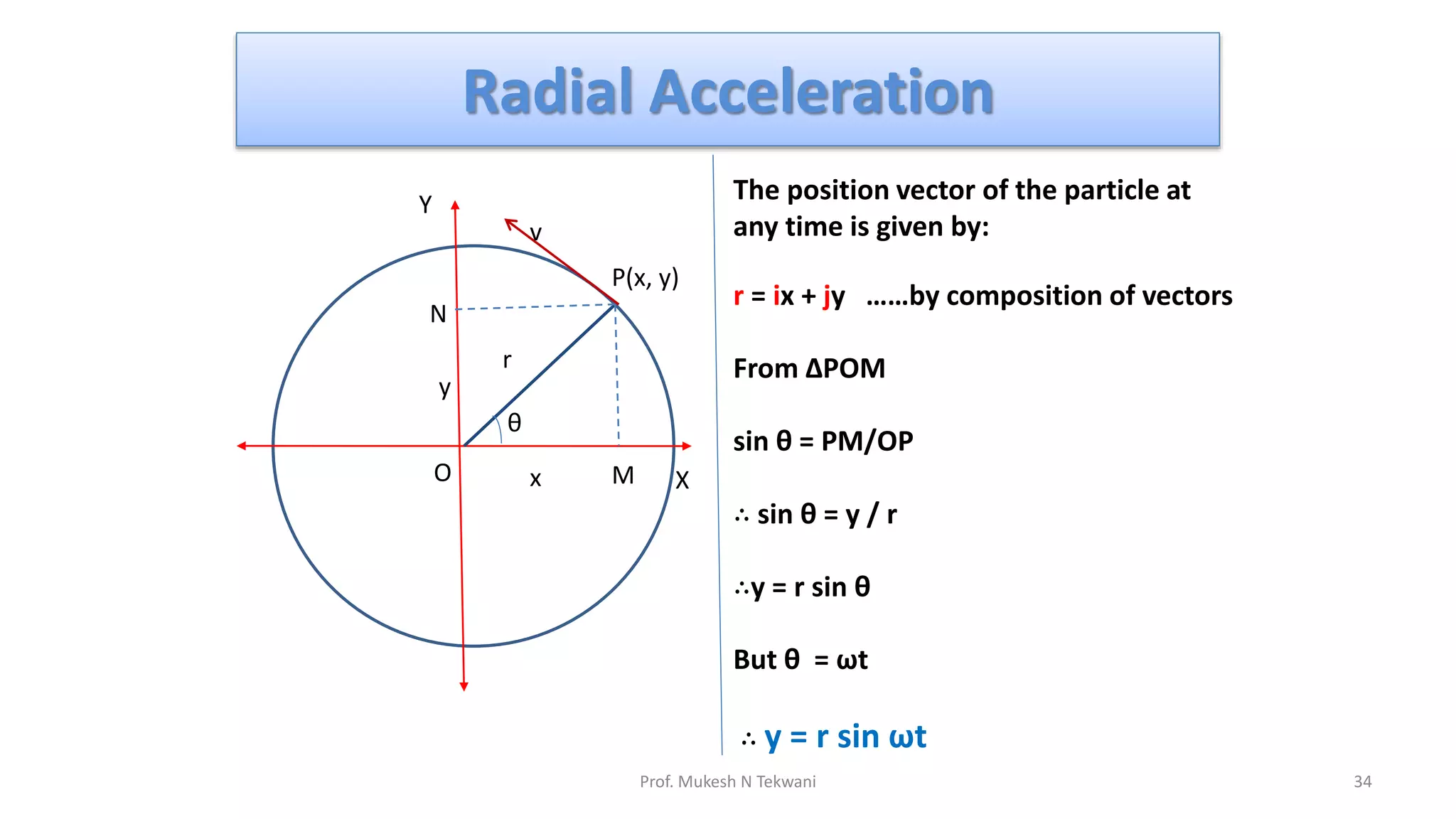

The velocity of particle at any instant (any time) is called its

instantaneous velocity.

The instantaneous velocity is given by

v = dr / dt

∴ v = d/dt [ ir cos wt + jr sin wt]

∴ v = - i r w sin wt + j r w cos wt](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/physics-circularmotion-210720032554/75/Circular-motion-23-2048.jpg)