This document discusses procedural fairness in the context of administrative law. It covers several key topics:

1) Sources of procedural fairness obligations, including the Charter, Canadian Bill of Rights, common law, and statutes.

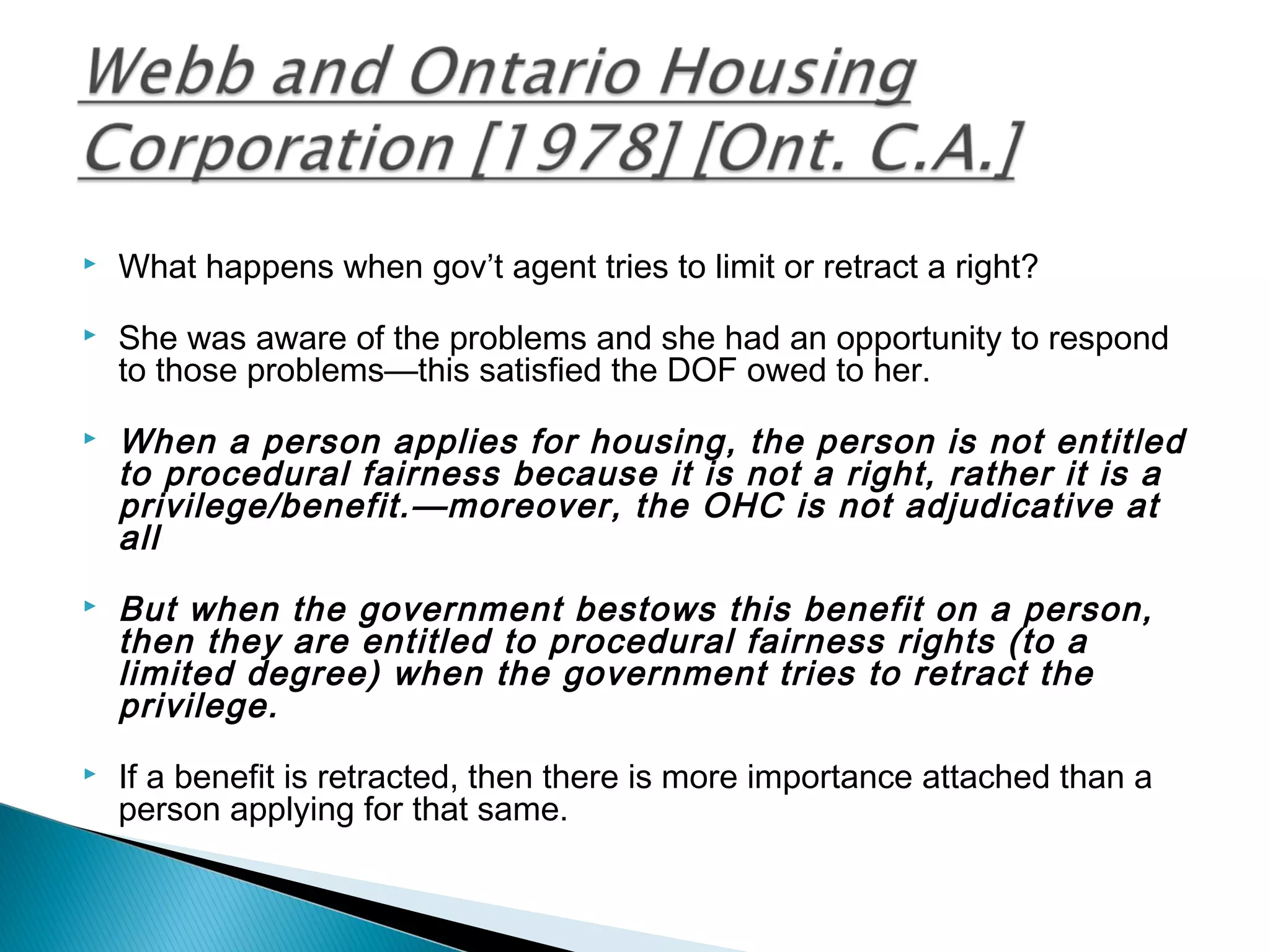

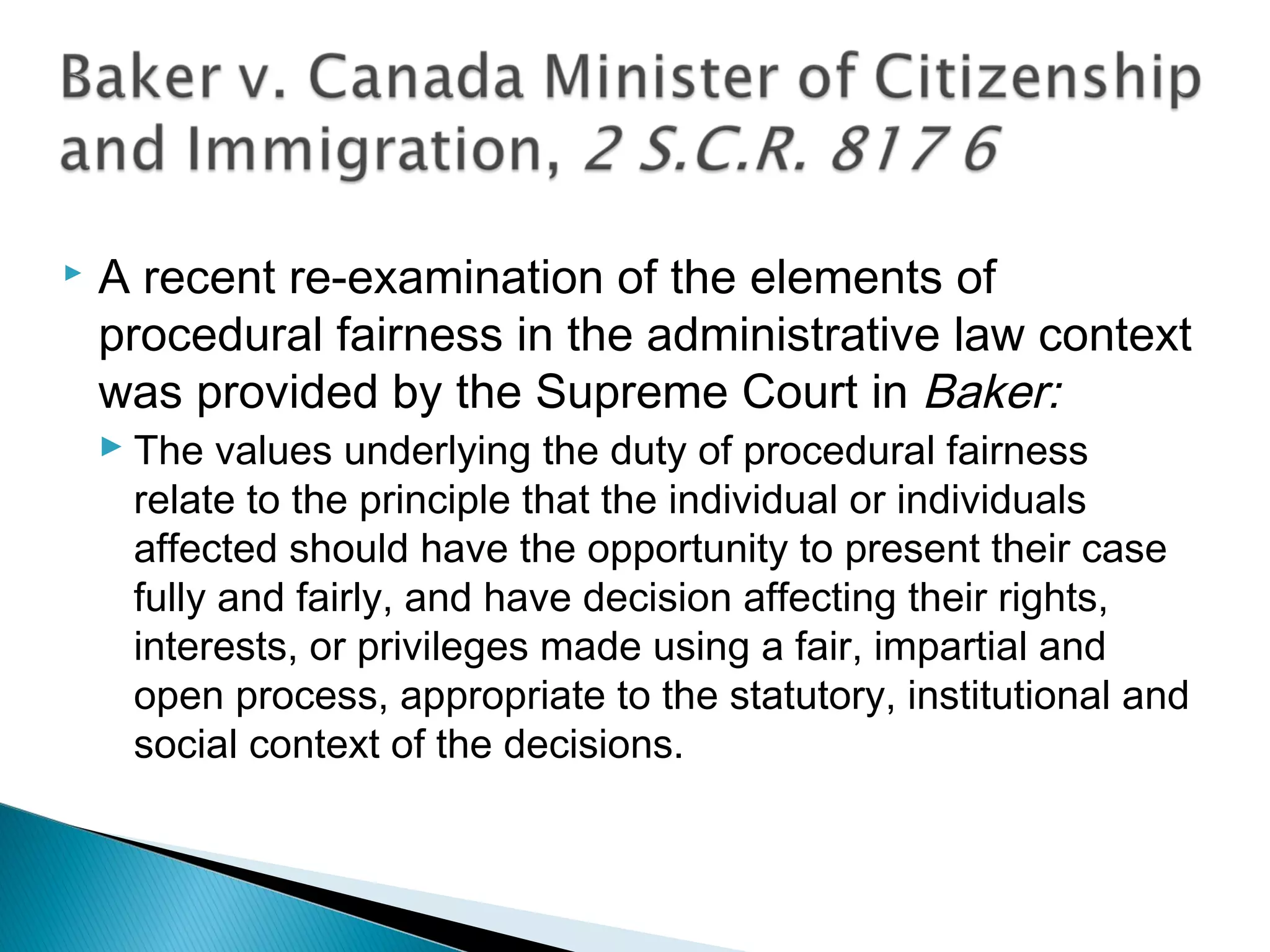

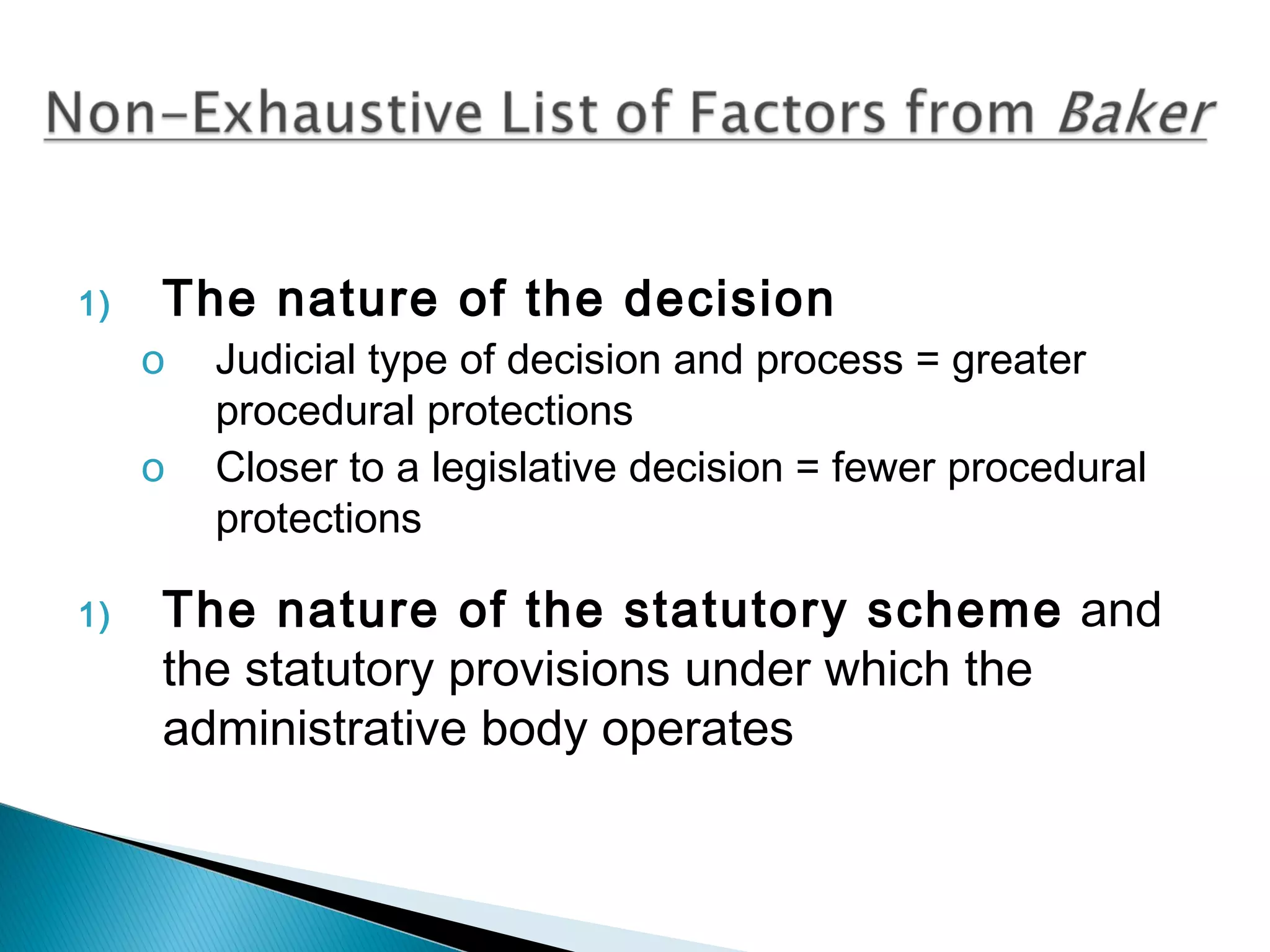

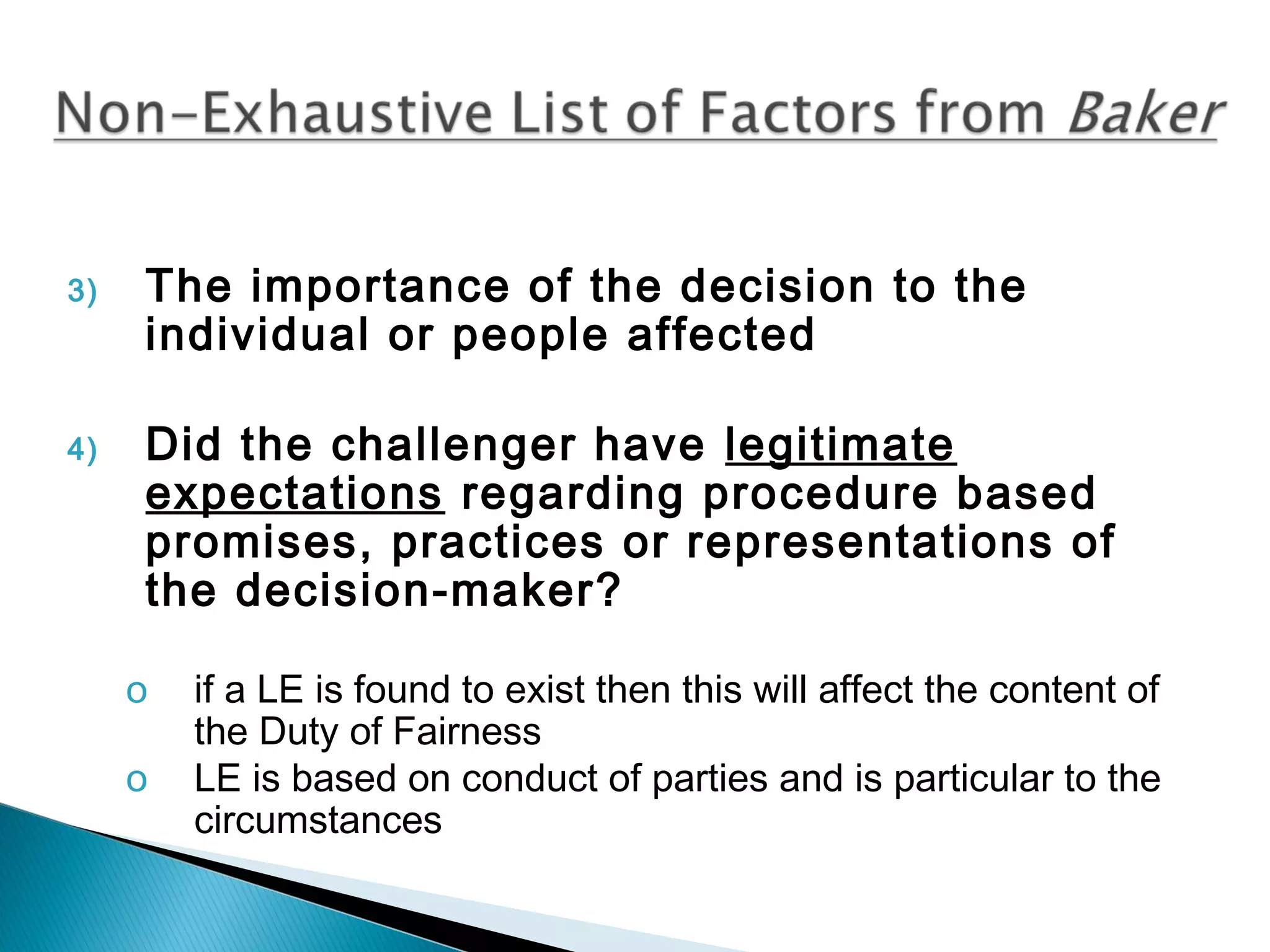

2) Key Supreme Court of Canada cases that have shaped the modern understanding of procedural fairness, including Nicholson, Baker, and Knight.

3) Factors considered in determining whether and to what extent procedural fairness applies in a given case, such as the nature of the decision, statutory context, and importance to individuals affected.

4) Examples of specific procedural protections, such as the right to a hearing, right to provide oral submissions, and right to respond to allegations.