This document discusses how Oracle's session wait virtual tables can be used to directly identify contention issues, reducing problem identification time. It provides details on the session wait views (v$system_event, v$session_event, v$session_wait) that show where sessions are waiting and why. This allows shifting from a traditional ratio-based analysis approach to directly seeing blocking issues. Examples are given of scripts using the views along with a case study analyzing the identified wait events.

![ways waiting for some resource. It could be data al-ready

in the SGA, data residing on disk, a latch (seri-alizing

execution for a piece of server kernel code),

an enqueue (access to an internal structure), a lock

(access to a user defined structure), or many other

items. But the bottom line is, there is always a bot-tleneck,

a session is always waiting for something

(either to start something or waiting for it to finish),

and the session wait statistics tells one exactly what a

specific session is specifically waiting for.

3.2 Session Wait Views

There is actually a family of session wait based

views. Each view has a special purpose and they

compliment each other providing direction for per-formance

specialists. The virtual tables are

v$system_event, v$session_event, and

v$session_wait. Each virtual table along with an

actual script and real-life output is presented below.

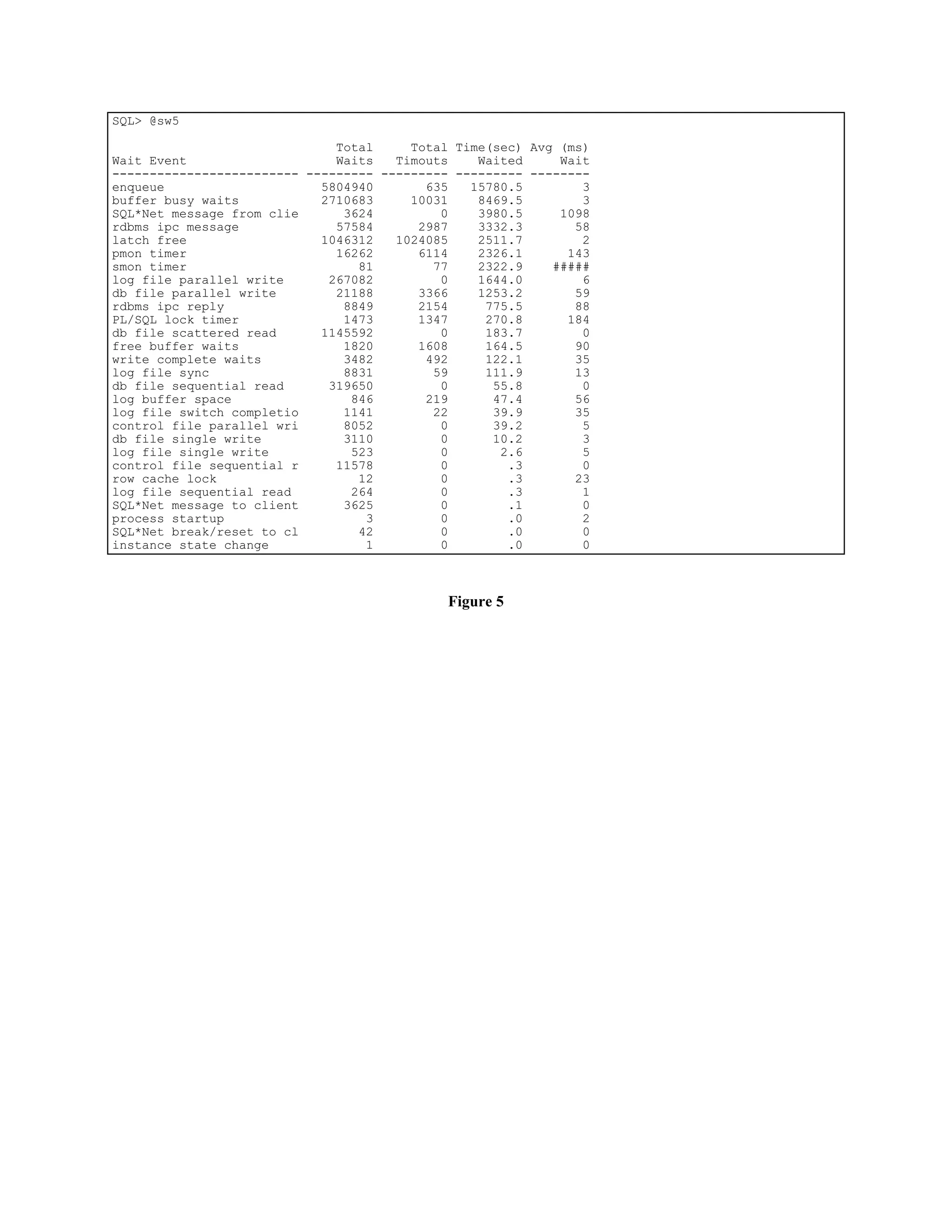

3.2.1 High level system perspective using

v$system_event

The v$system_event view looks at sessions at a high-level

perspective. It doesn’t report which specific

session is waiting for which specific resource or ob-ject.

It sums all the waits since the database instance

was last started by wait category. As with all “in-stance

accumulating” statistics (e.g., v$sysstat), col-lecting

and reporting the differences over periods of

time is much more useful than a single query.[Total

Performance Management]

There are only five columns in the v$system_event

view. Each is presented below.

· Event. This is simply the general name of the

event. While there are many wait events, the

most common events are latch waits, db file

scattered read, db file sequential read, en-queue

wait, buffer busy wait, and free buffer

waits. While I will be detailing the most com-mon

events, presenting each wait event is out of

scope for this paper. To get details about other

events one is experiencing, contact an Oracle

representative or search the WWW.

· Total_waits. This is the total number of waits,

i.e., a count, for the specific event since the da-tabase

instance has started.

· Total_timeouts. This is the total number of

wait time-outs, i.e., a count, for the specific

event since the database instance has started.

Not all waits result in a time-out. Some waits

will try “forever” (an exponential back-off algo-rithm

is sometimes used) while others will try

once or a few times, stop, and perform some

coded action.

· Time_waited. This is the total time, in milli-seconds,

all sessions have waited for the specific

event since the database instance has started.

· Average_wait. This is the average time, in

milliseconds, all sessions have waited for the

specific event since the database instance has

started. As one would expect, this should equal

time_waited divided by total_waits.

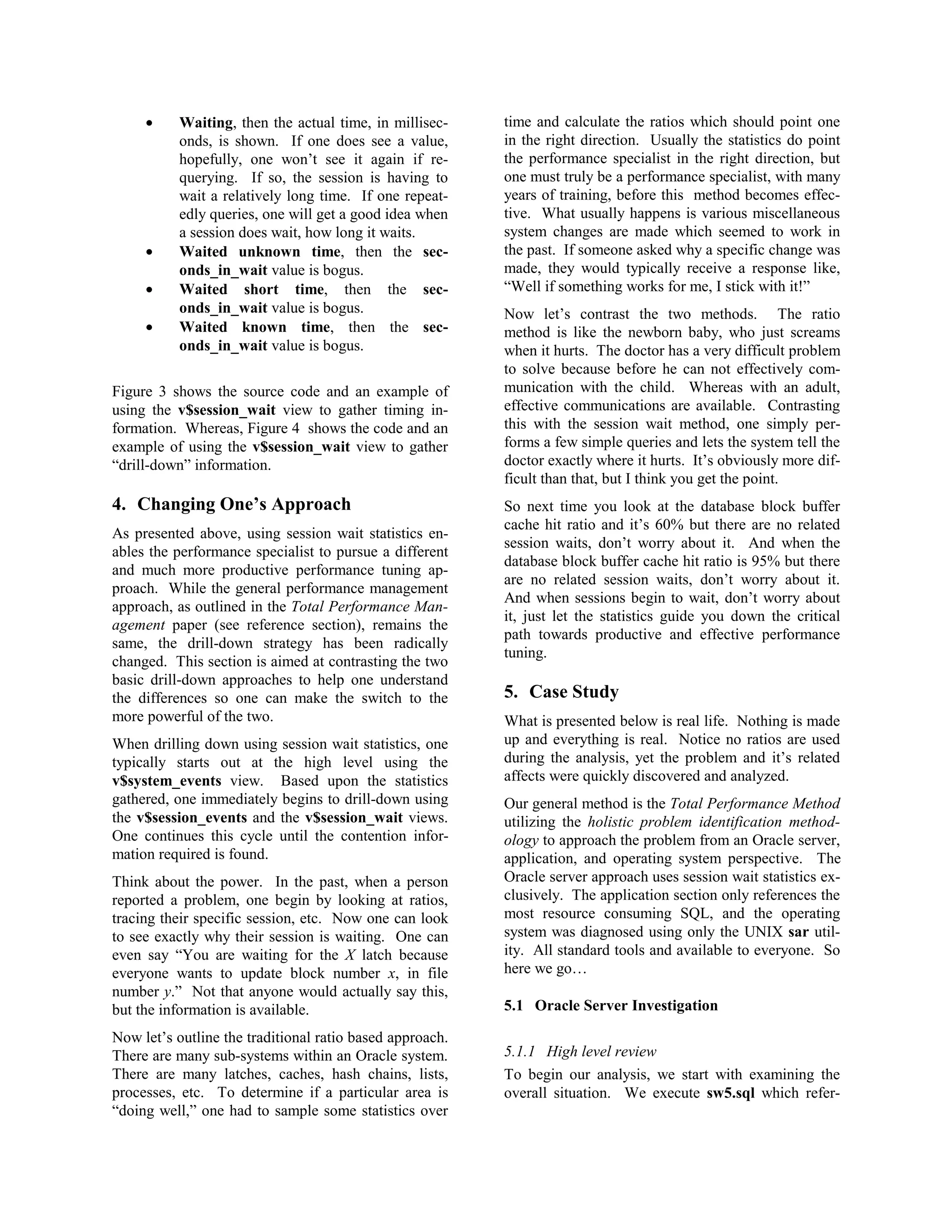

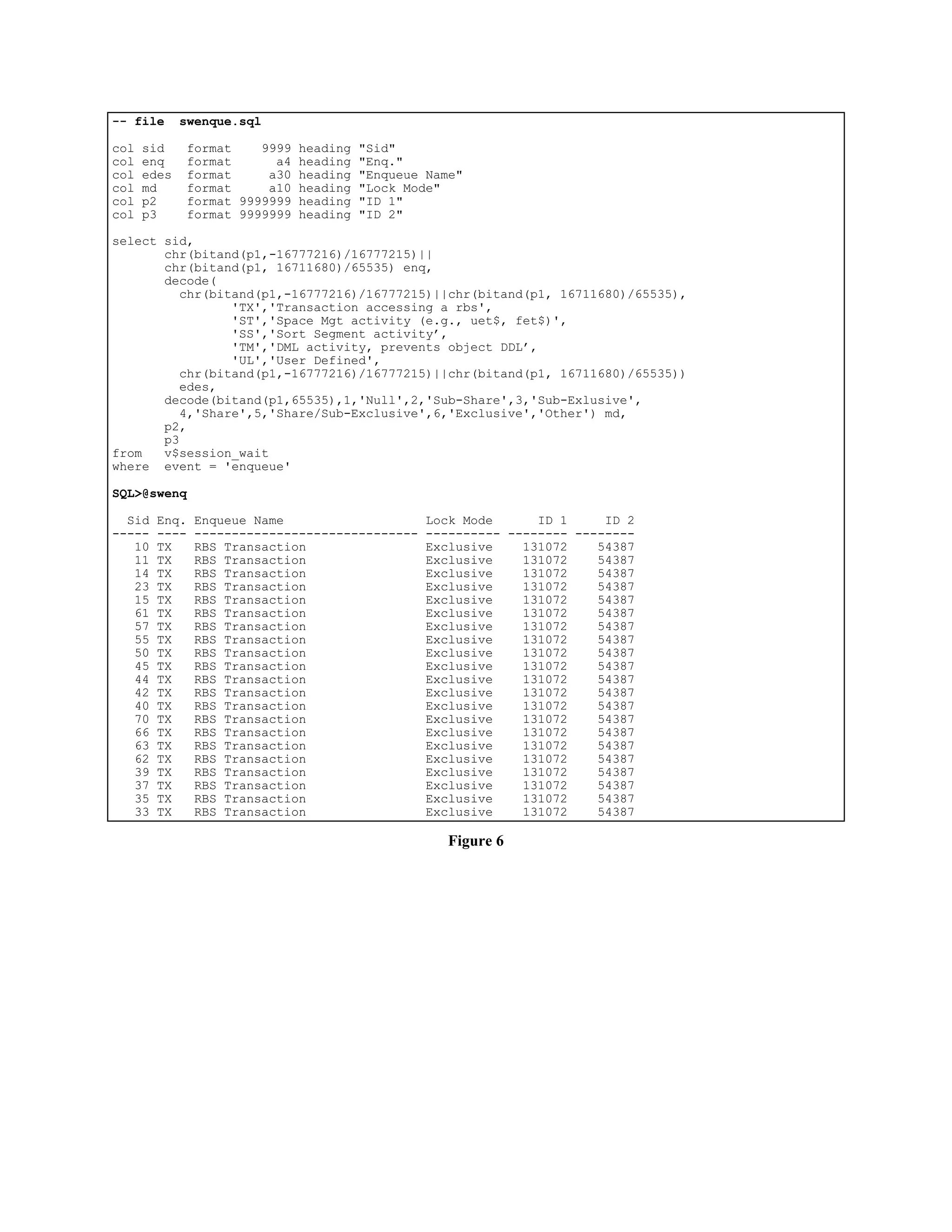

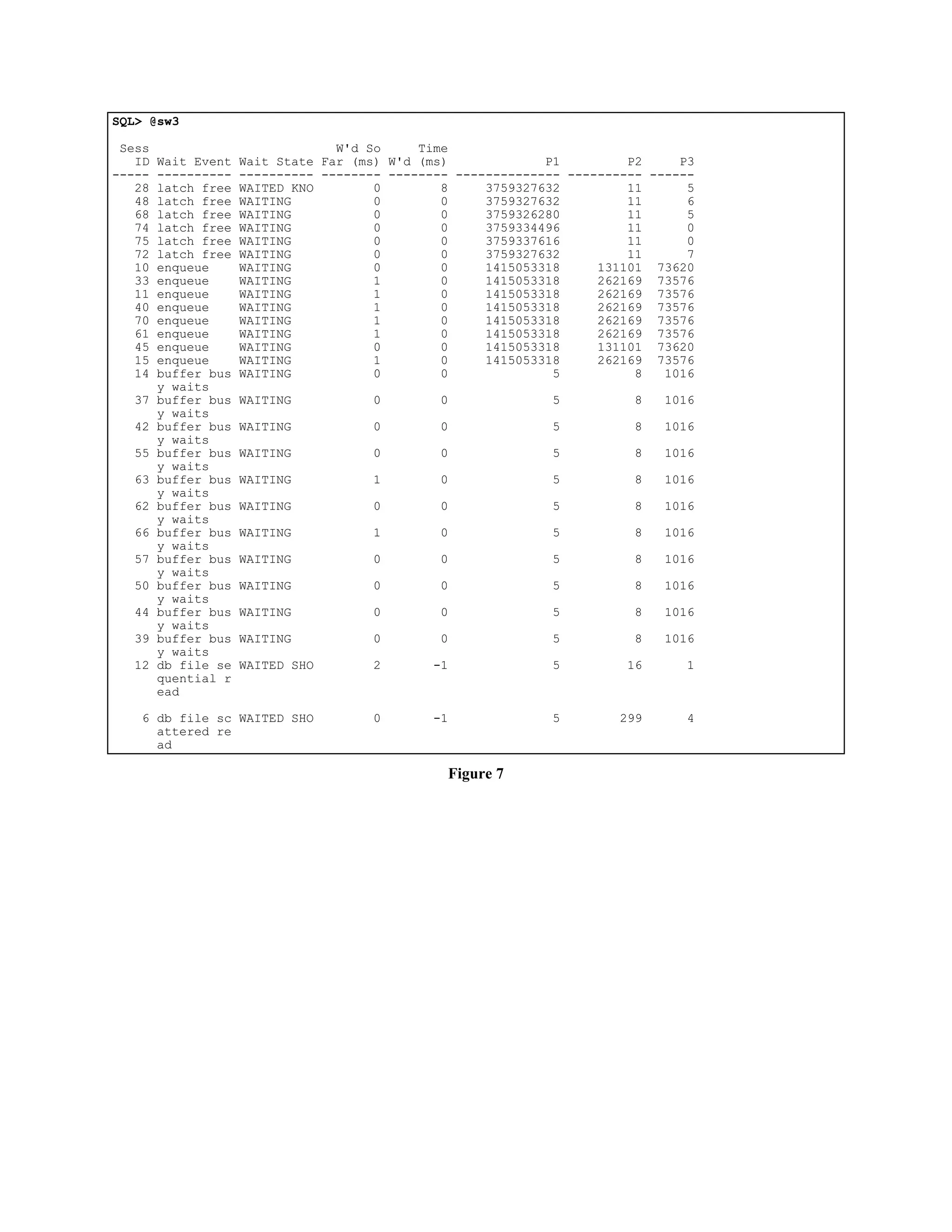

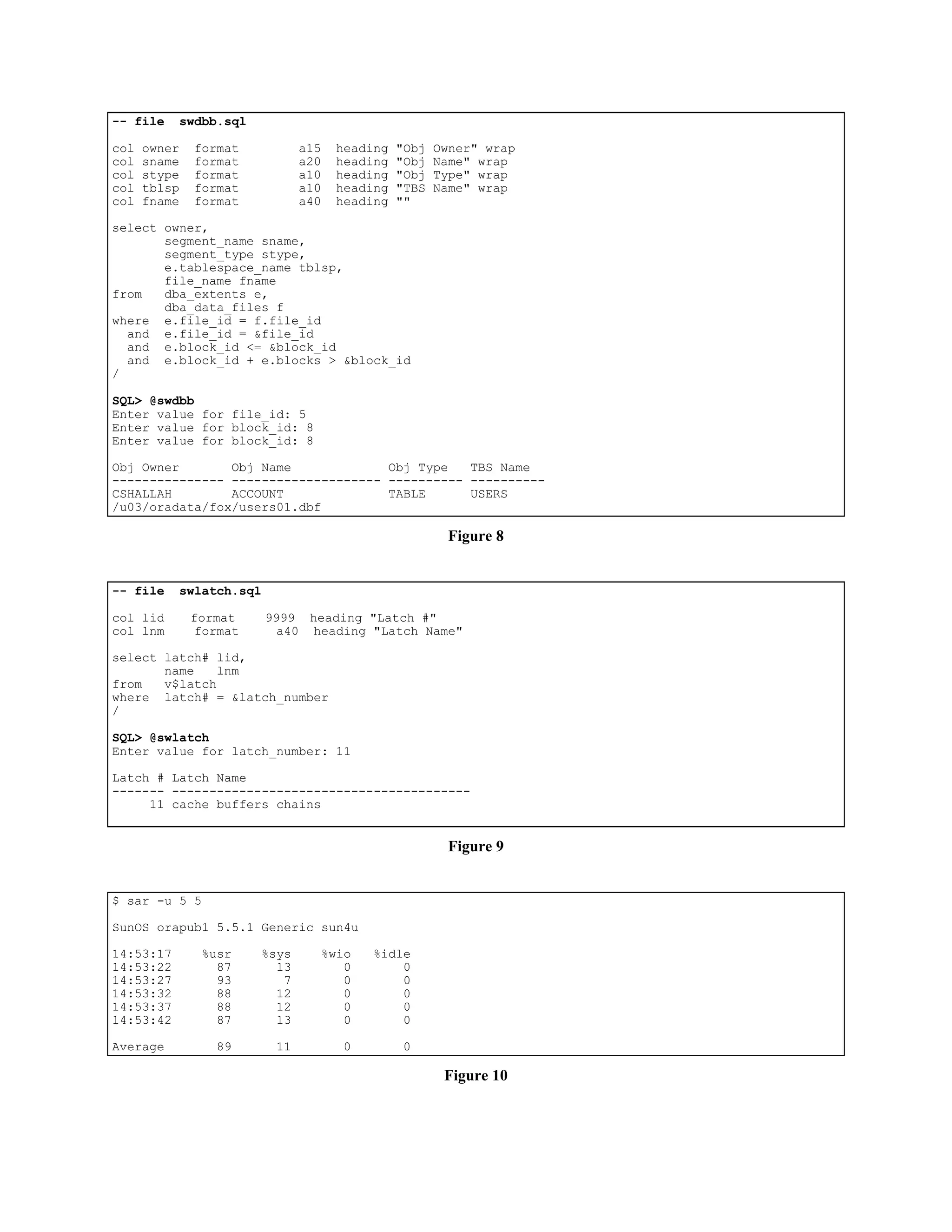

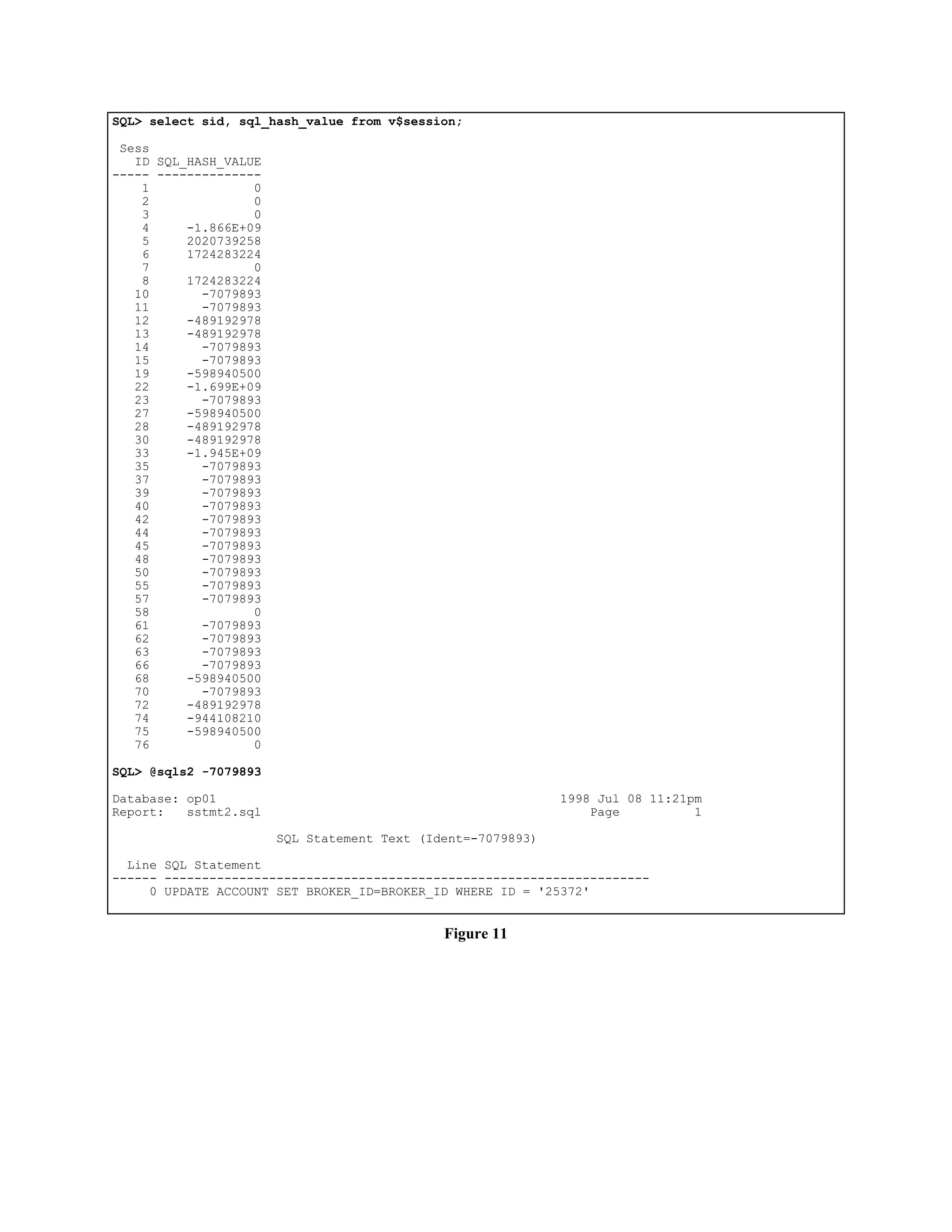

Figure 1. presents a v$system_event based tool and

sample output. Figure 1. clearly shows sessions

waiting for enqueues, busy database block buffers,

latches, and database files. Each of these common

waits will be discussed in this paper. Once the over-all

system has been examined, one drills-down into

each one of the significant wait areas, which we begin

presenting below.

3.2.2 High level session perspective using

v$session_event

The v$session_event virtual view presents exactly

the same information as the v$system_event virtual

view except it includes the session id for each event

and information is “zeroed” out after a session logs

off. For example, if session ten’s statistics suddenly

drop, that’s because session ten just logged off and

another session logged in and was assigned session

number ten.

This view is very useful for determining which ses-sions

are causing or experiencing the most waits and

then drilling down into the contention specifics.

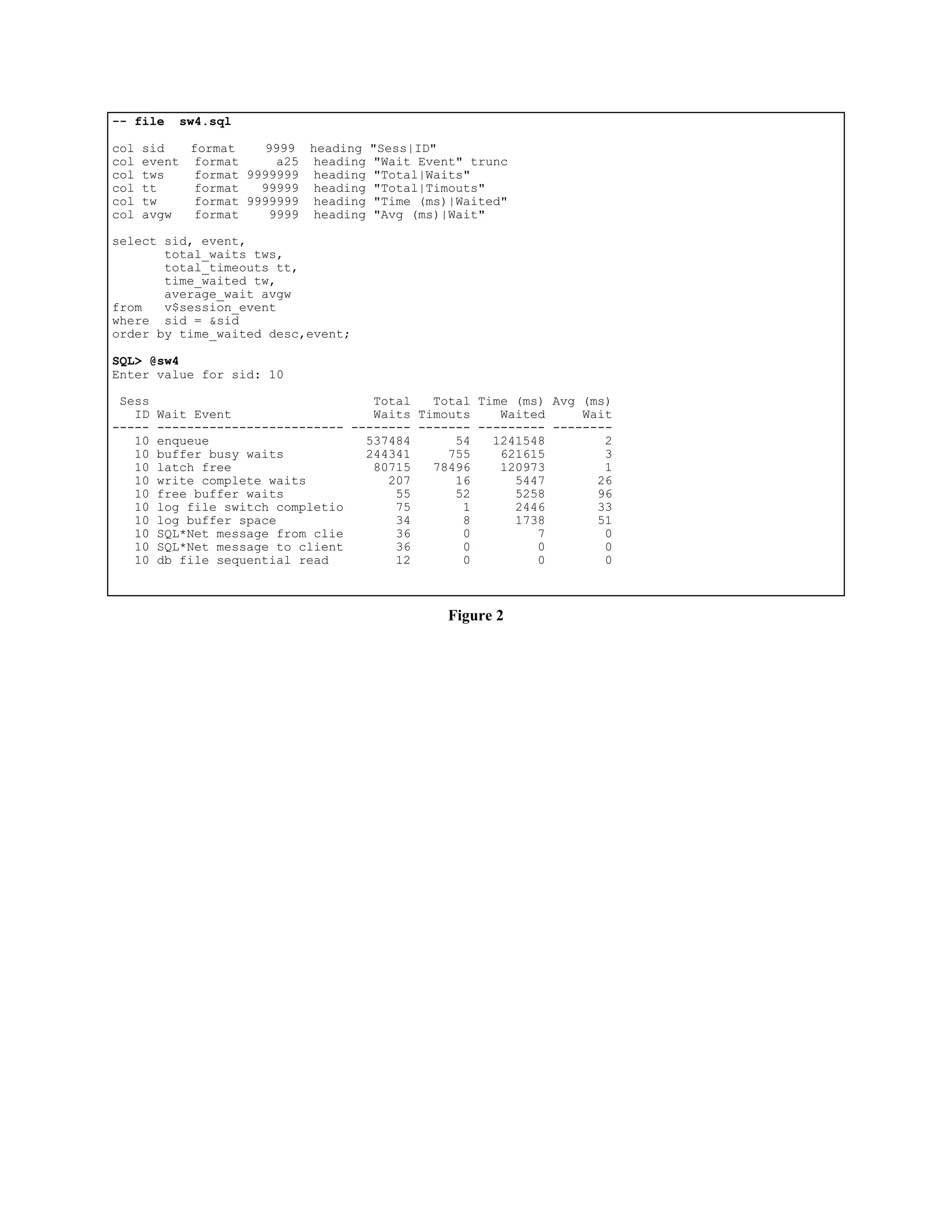

Figure 2 below presents a v$session_event based tool

and sample output. In situations where the session id

is not known or is not relevant, one could execute the

Figure 2 script without the session id filter. In the ex-ample

shown, session id is asked for and supplied.

Figure 2 clearly shows that session ten is experienc-ing

significant enqueue, buffer busy, and latch waits.

As we will see, this combination points towards ex-cessive

buffer activity typically caused by poorly

tuned SQL, poor application design, or both.

3.2.3 Low level session perspective using

v$session_wait

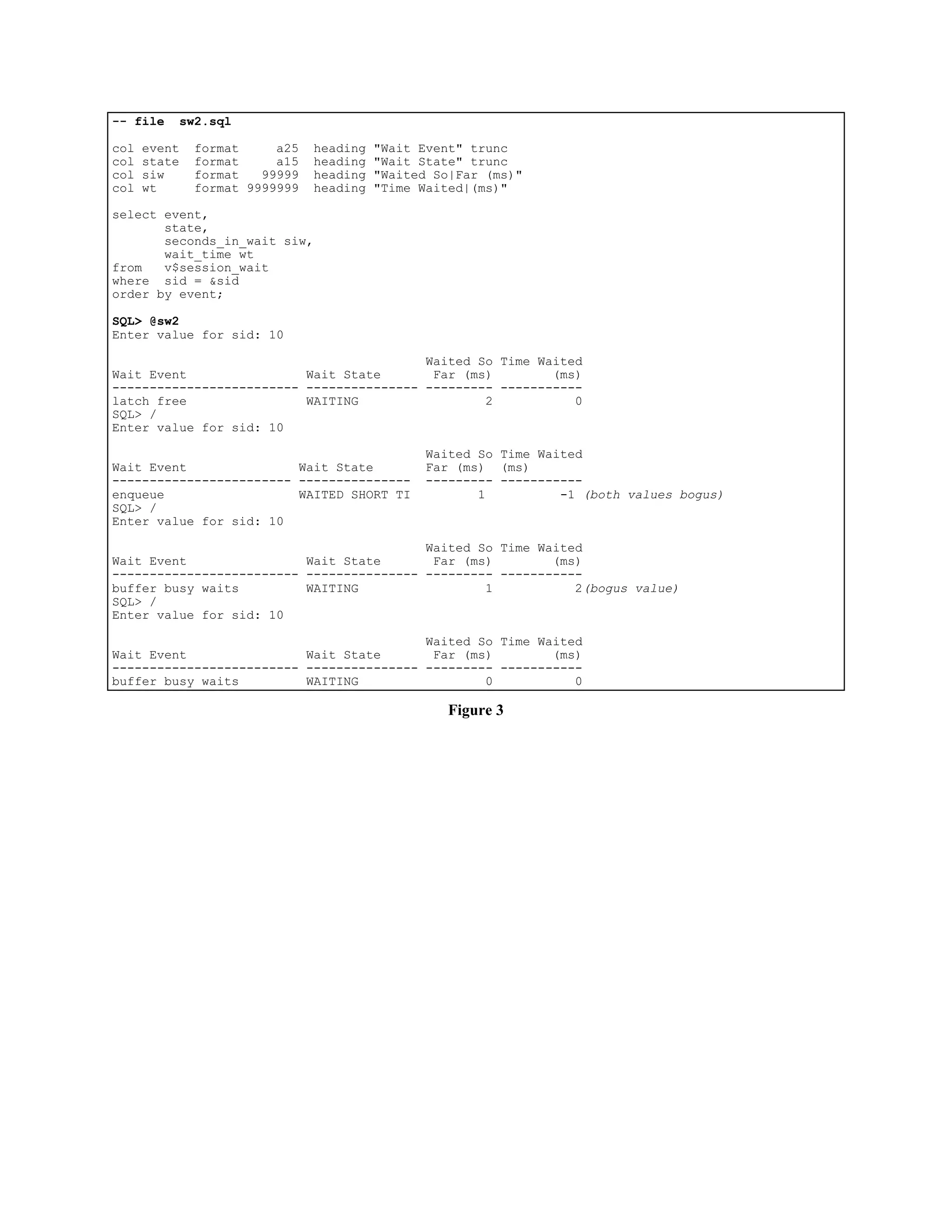

The v$session_wait view is the most complicated

and the most misunderstood of the session wait fam-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/appssessionwaittables-141121065106-conversion-gate02/75/Apps-session-wait_tables-2-2048.jpg)

![ily. I suppose this is because unlike the

v$system_event and the v$session_event view, the

v$session_wait view reports session level wait in-formation

in real-time. It does not store or summa-rize

information, but rather dumps out the raw infor-mation

as it’s occurring.

Activity in an Oracle database occurs very, very fast

(as opposed to other database vendors of course), so

even quickly re-running a v$session_wait query may

look totally different than a split-second before.

Don’t be alarmed by this, but rather understand why

this occurs.

In addition to presenting information in real-time, the

v$session_wait view provides detailed and specific

information about the actual waits. For example, it

will direct one to sessions experiencing latch conten-tion

and show which latch the sessions are waiting

for. Or, if a session is waiting for access to a block,

the actual database file number and data block num-ber

are provided.

The v$session_wait view also presents timing details,

much like the v$system_event and v$session_event

views. However, because of the v$session_wait’s

real-time reporting, the times presented mean differ-ent

things depending on the wait situation. This is

explained in more detail below.

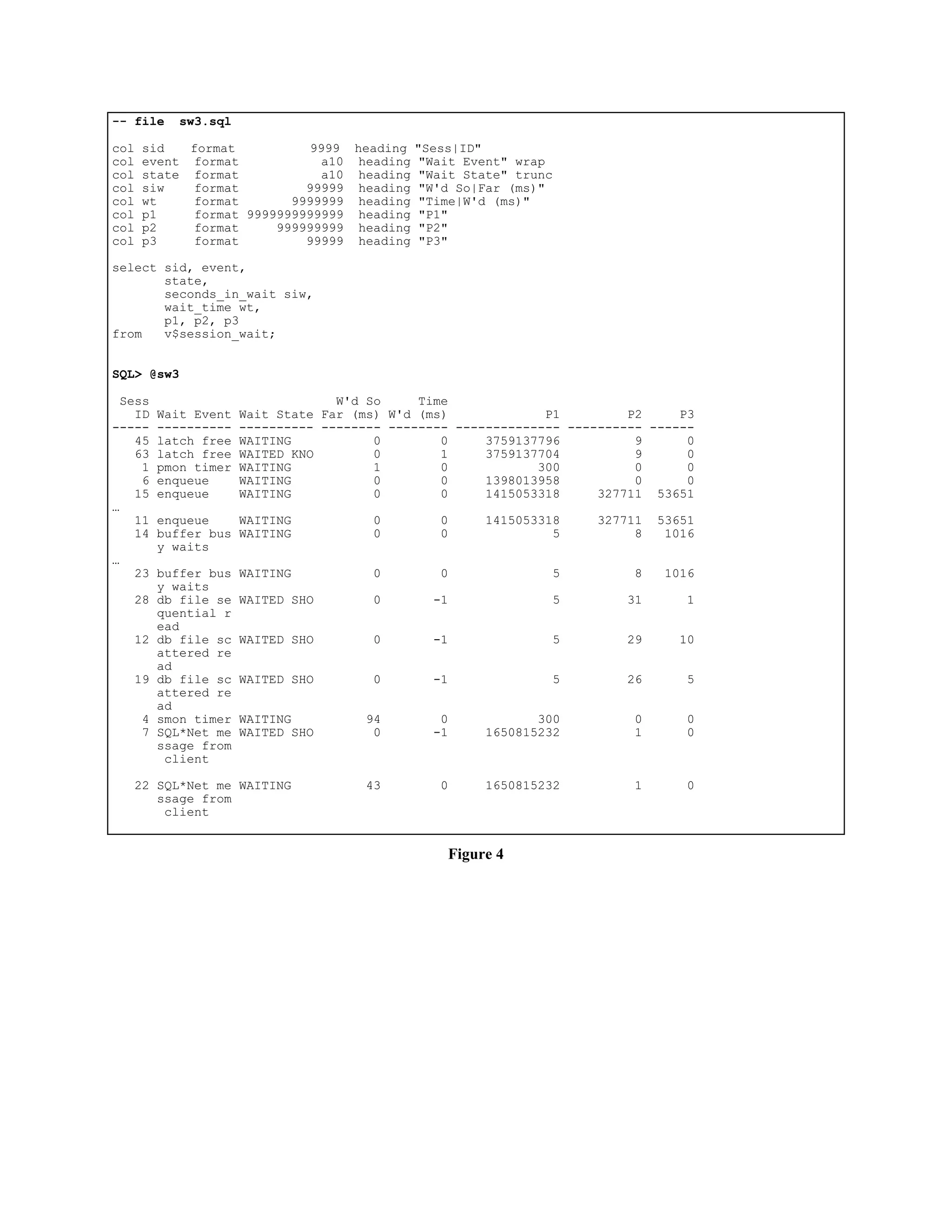

The v$session_wait columns are presented below.

· Sid. The session id number. The same as the

session id number in v$session_event and

v$session.

· Seq#. The internal sequence number of the wait

for this session. Use this column to determine

the number of waits, i.e. counts, the session has

experienced.

· Event. This is simply the general name of the

event. While there are many wait events, the

most common events are latch waits, db file

scattered read, db file sequential read, en-queue

wait, buffer busy wait, and free buffer

waits. While I will be detailing the most com-mon

events, presenting each wait event is out of

scope for this paper. To get details about other

events one is experiencing, contact an Oracle

representative or search the WWW

· P[1-3]. These three parameters are pointers to

more details about the specific wait. The pa-rameters

are foreign keys to other views and are

wait event dependent. For example, for latch

waits, p2 is the latch number, which is a foreign

key to v$latch. But for db file sequential read

(indexed read, yes an indexed read), p1 is the

file number (foreign key to v$filestat or

dba_data_files) and p2 is the actual block

number (related to dba_extents, sys.uet$,

sys.fet$). To use these parameters, one needs a

list of the waits with their associated parameters.

Again, for parameter specifics contact an Oracle

representative or search the WWW. The p[1-

3]text column may provide some information.

· P[1-3]raw. This is the raw representation of

p[1-3]. This is not used very often and none of

the tools presented in this paper make reference.

· P[1-3]text. Sometime the name of the parame-ter,

p[1-3], is provided. Don’t count on it.

· State. This is a very important parameter be-cause

is tells one how to interpret the next two

columns discussed below, wait_time and sec-onds_

in_wait. If one misinterprets the state or

chooses to ignore it, one will most likely misin-terpret

the wait_time and seconds_in_wait

numbers. The state column has four possible

values.

· Waiting. The session is currently waiting

for the event.

· Waited unknown time. The instance pa-rameter,

timed_statistics is set to false.

· Waited short time. Indeed, the session

did not wait even one clock tick to get

what it wanted, so no wait time was re-corded.

· Waited known time. Once the session

has waited and then received what it

wanted, the state turns from waiting to

waited known time.

· Wait_time. The value is dependent on the state

column discussed above. If the state column

value is:

· Waiting, then the wait_time value is bo-gus.

· Waited unknown time, then the

wait_time value is bogus.

· Waited short time, then the wait_time

value is bogus.

· Waited known time, then the actual wait

time, in milliseconds, is shown. One is

very lucky to see this value, because if the

session begins waiting for another re-source,

i.e., status will now be waiting,

the wait_time value turns bogus.

· Seconds_in_wait. The value is dependent on

the state column. If the state column value is:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/appssessionwaittables-141121065106-conversion-gate02/75/Apps-session-wait_tables-3-2048.jpg)