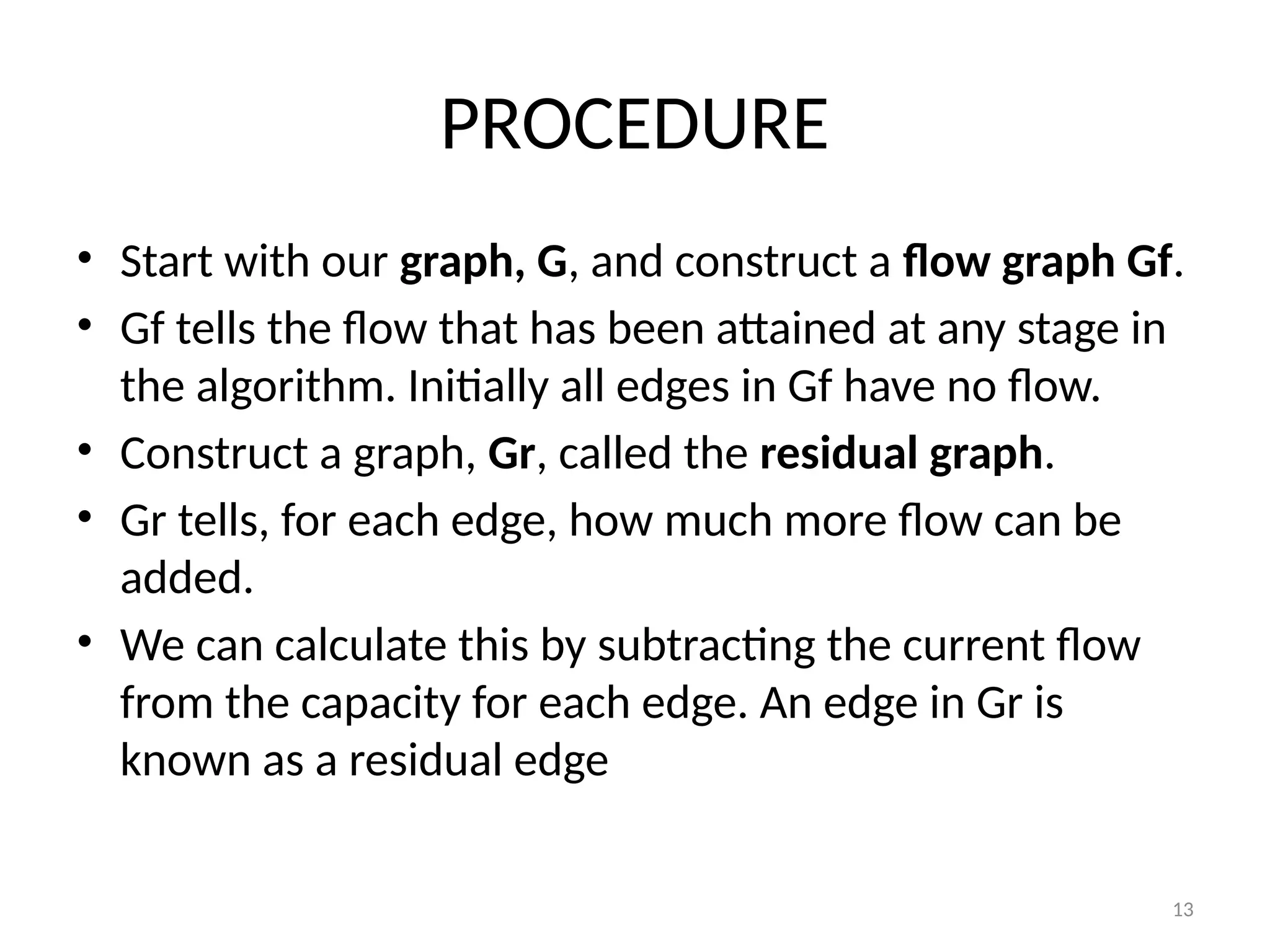

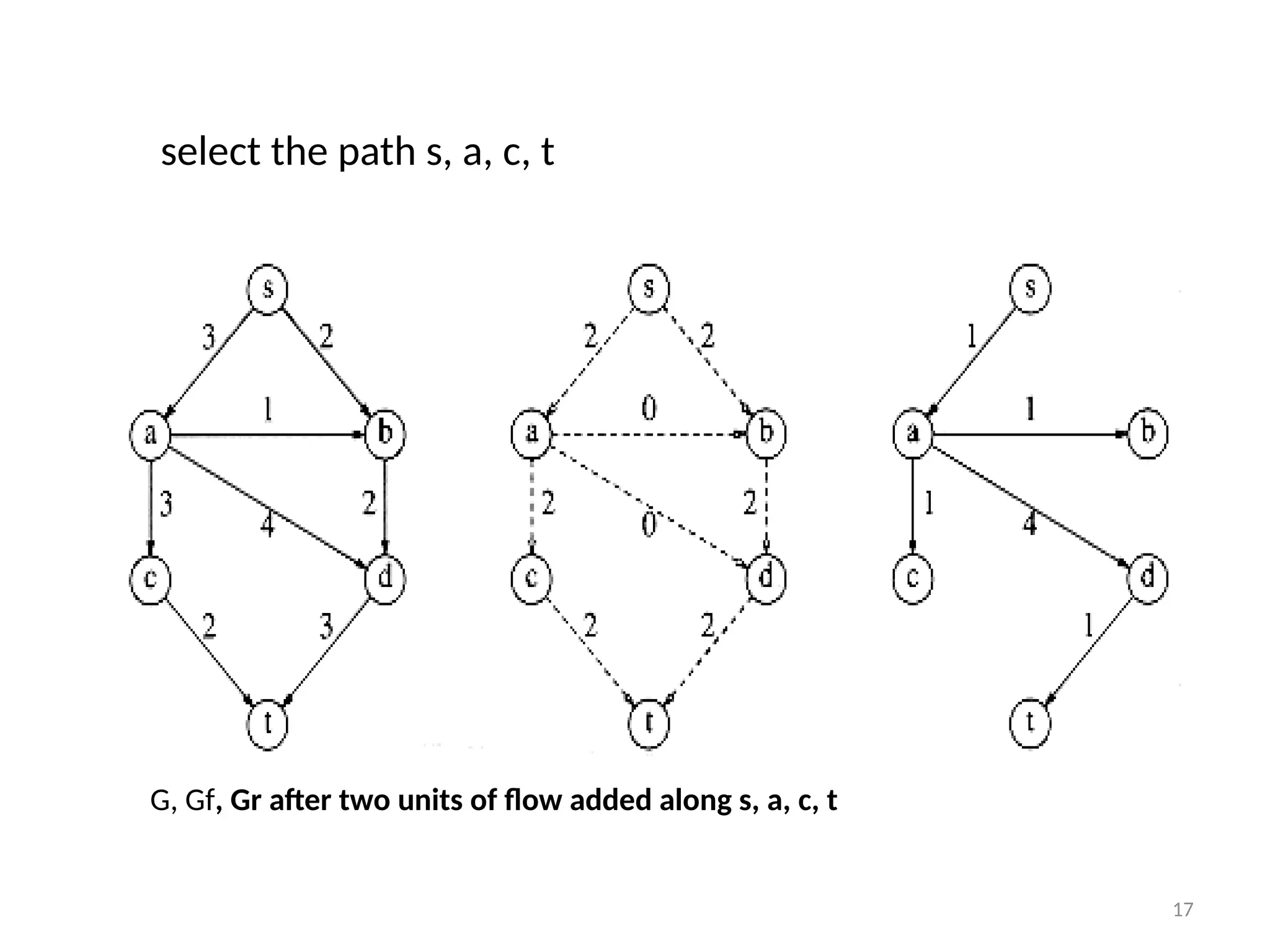

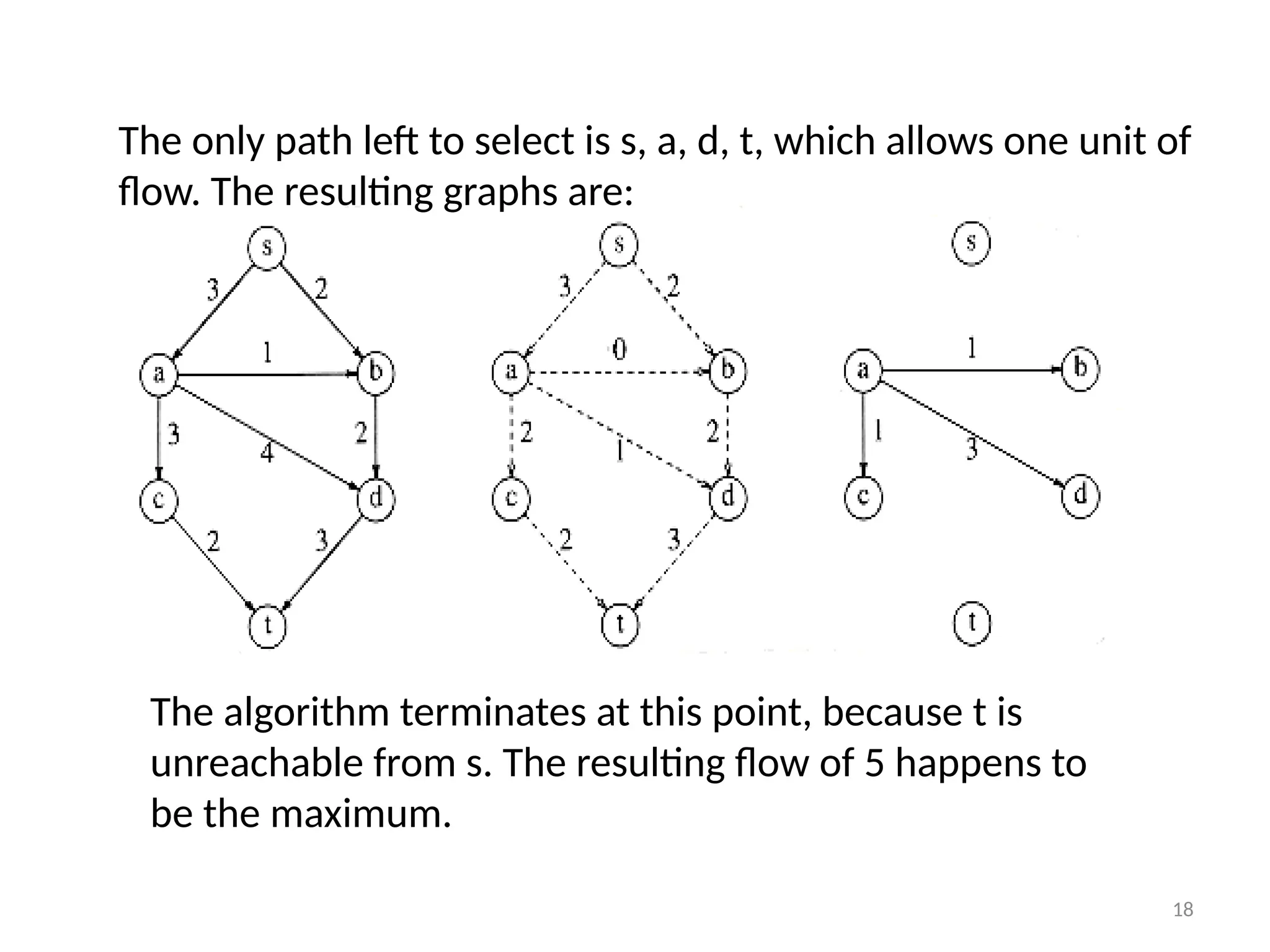

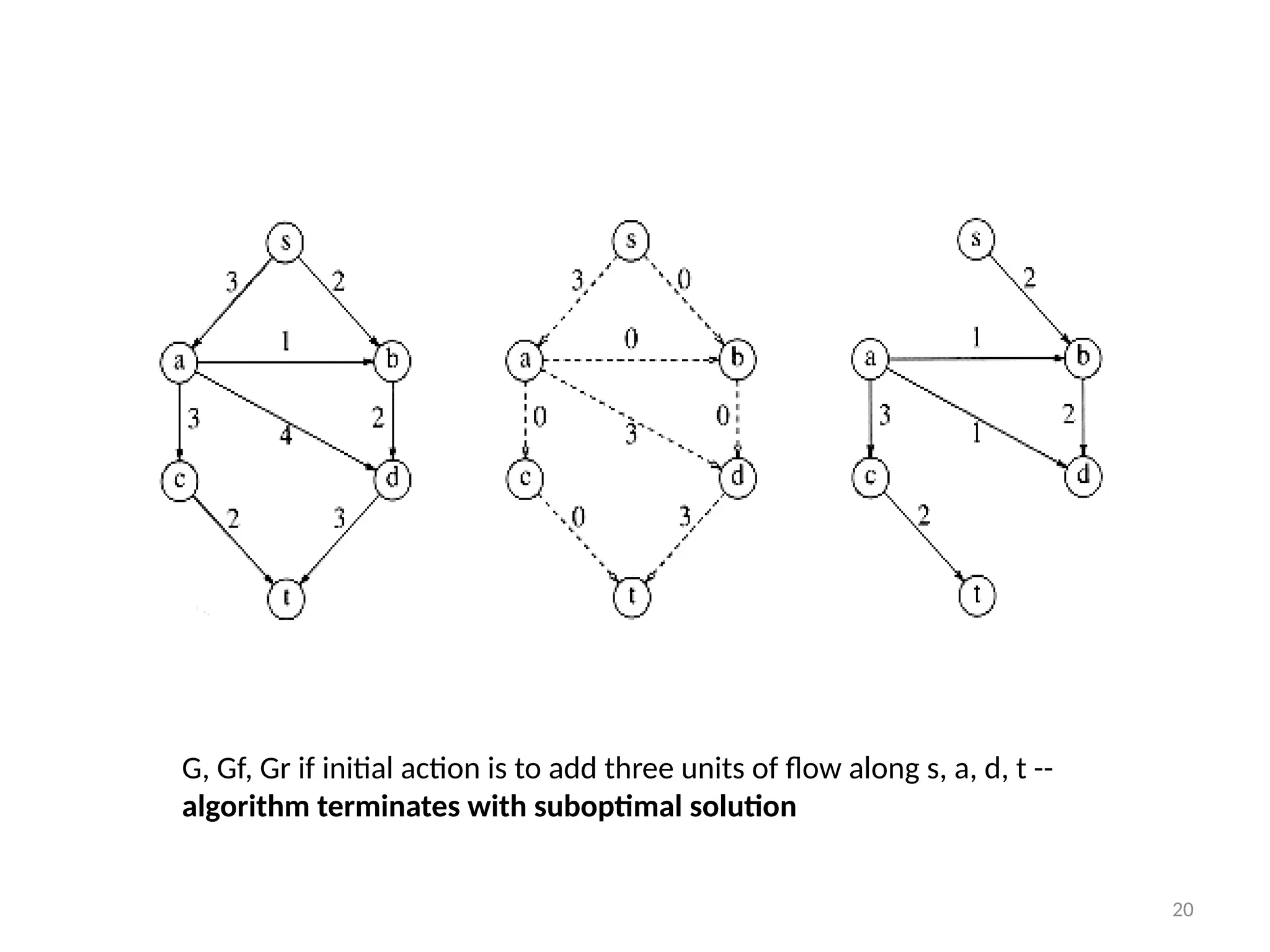

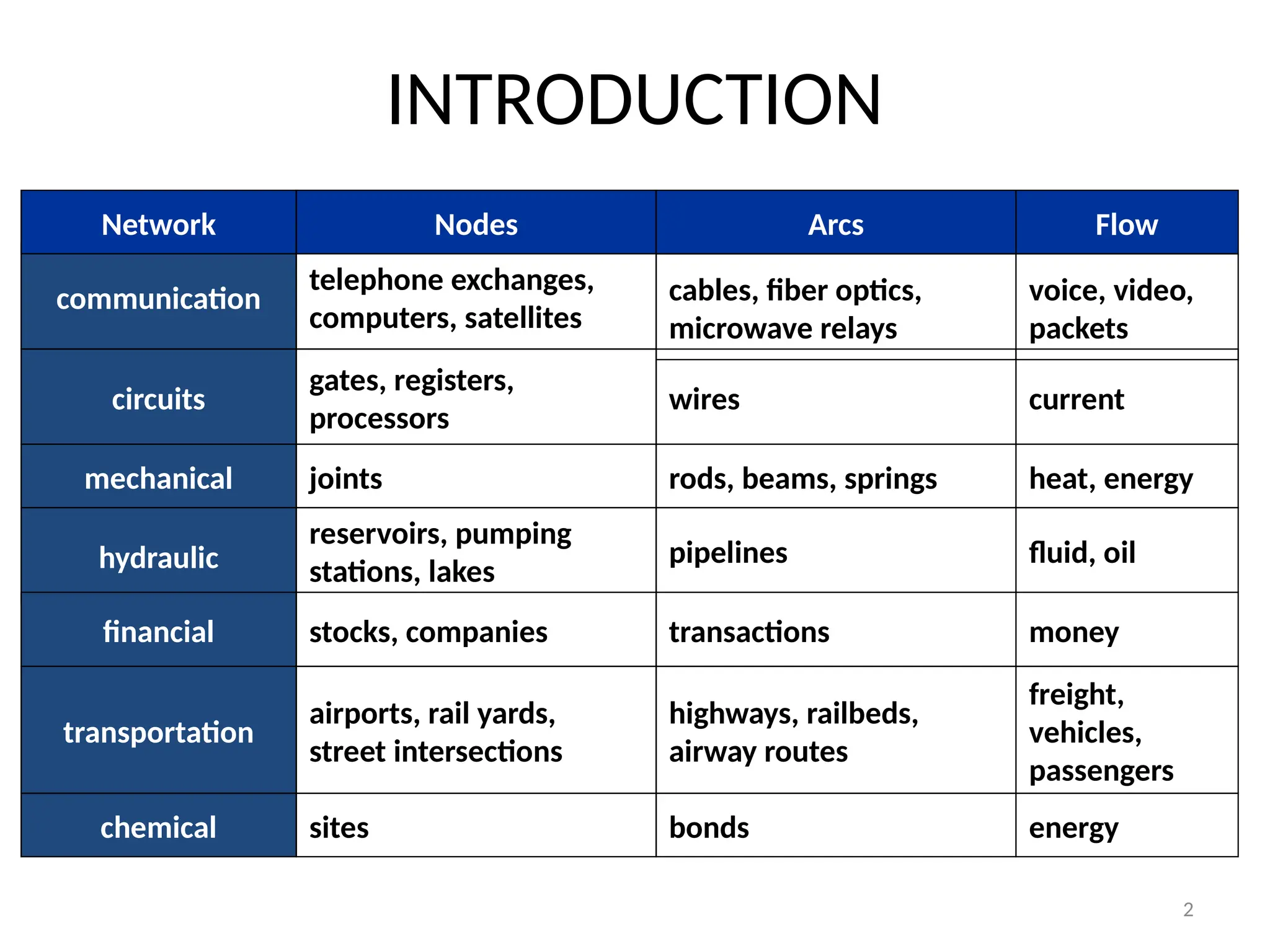

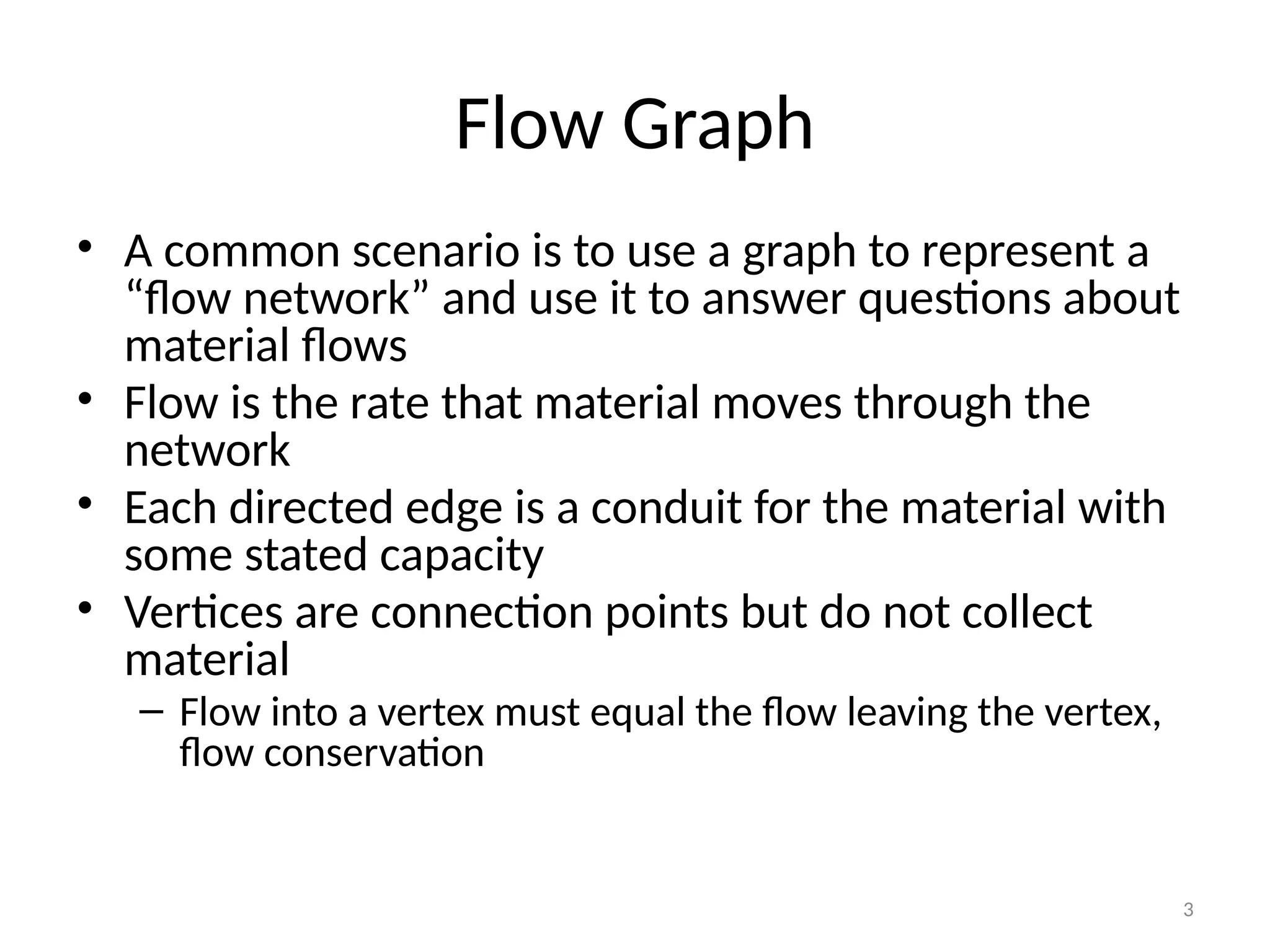

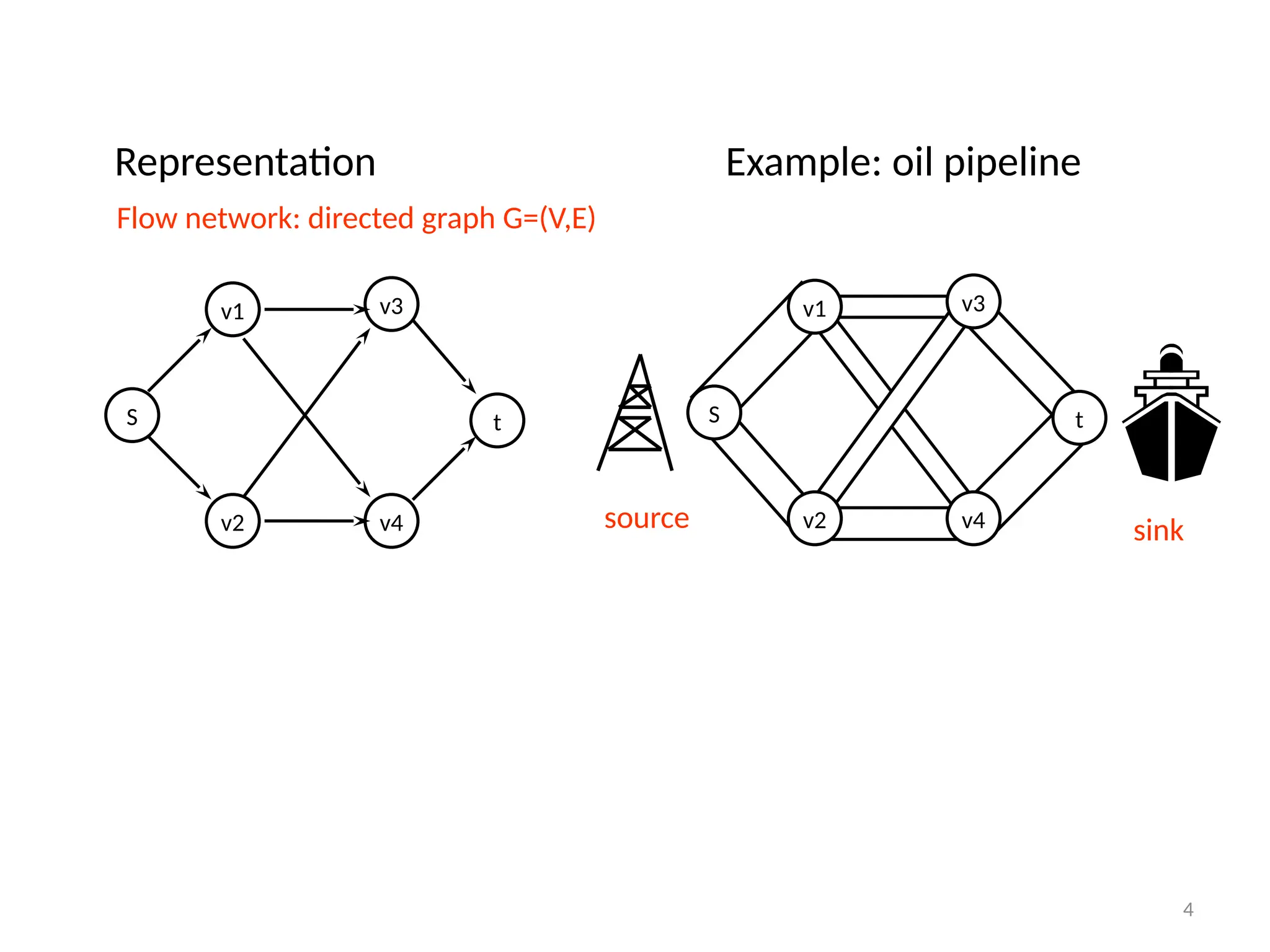

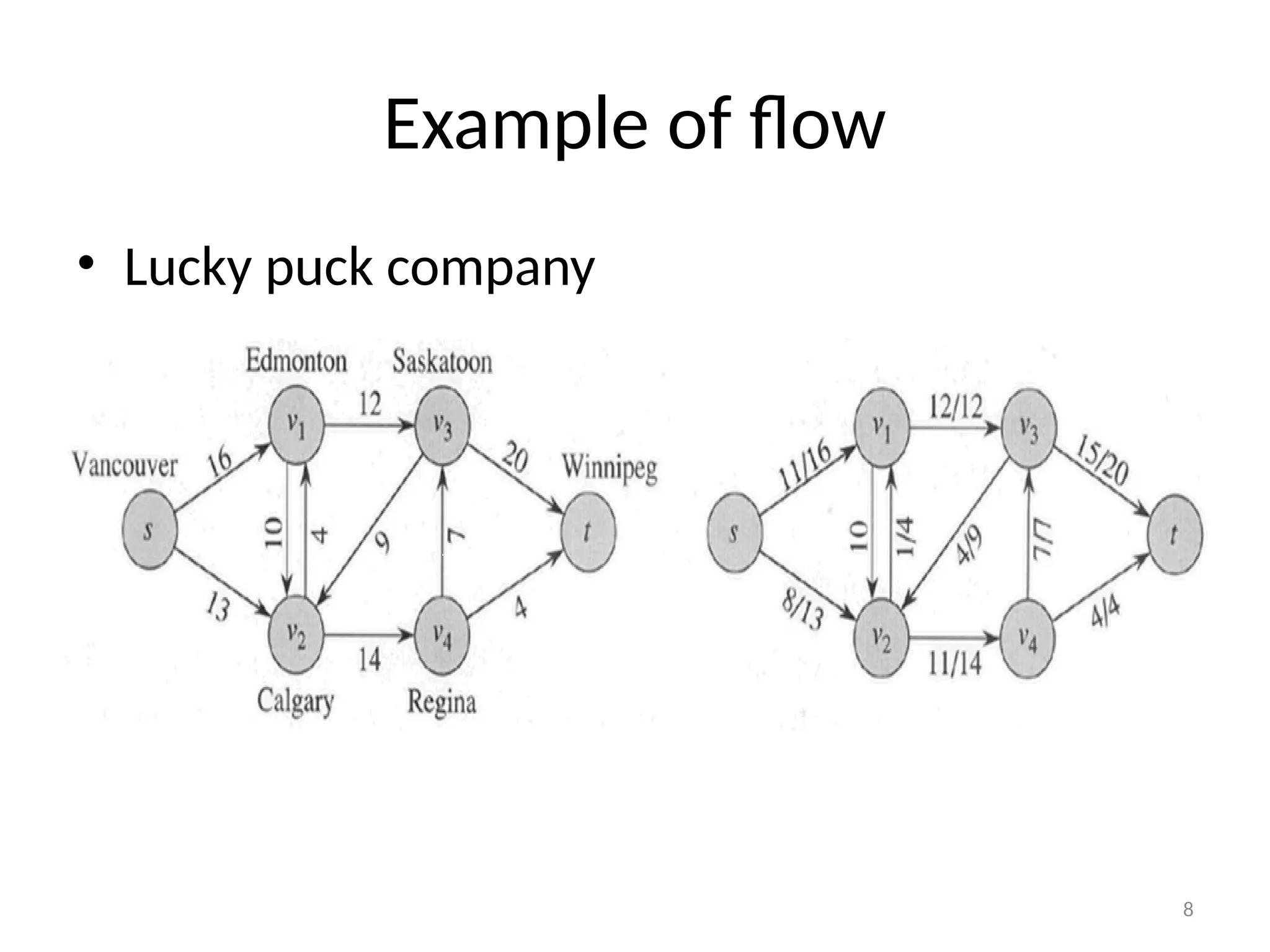

The document discusses network flow problems, focusing on flow networks represented as directed graphs with vertices and edges indicating material flow and capacity. It delves into the maximum flow problem, elucidating methods like the Ford-Fulkerson method for optimizing flow from a source to a sink within a network. Additionally, it highlights challenges such as greedy algorithm failures and suggests strategies for improving the efficiency of finding maximum flows.

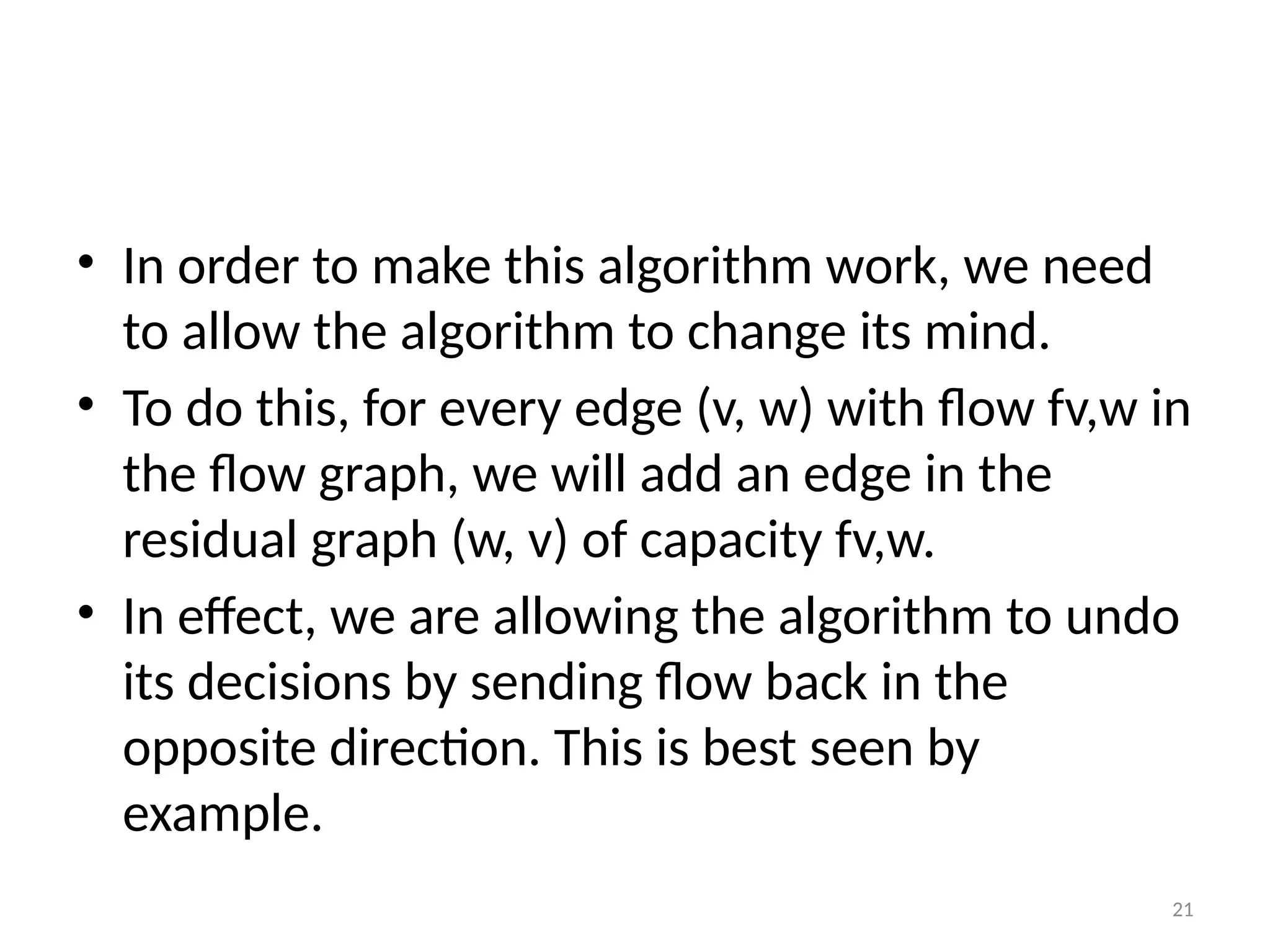

![12

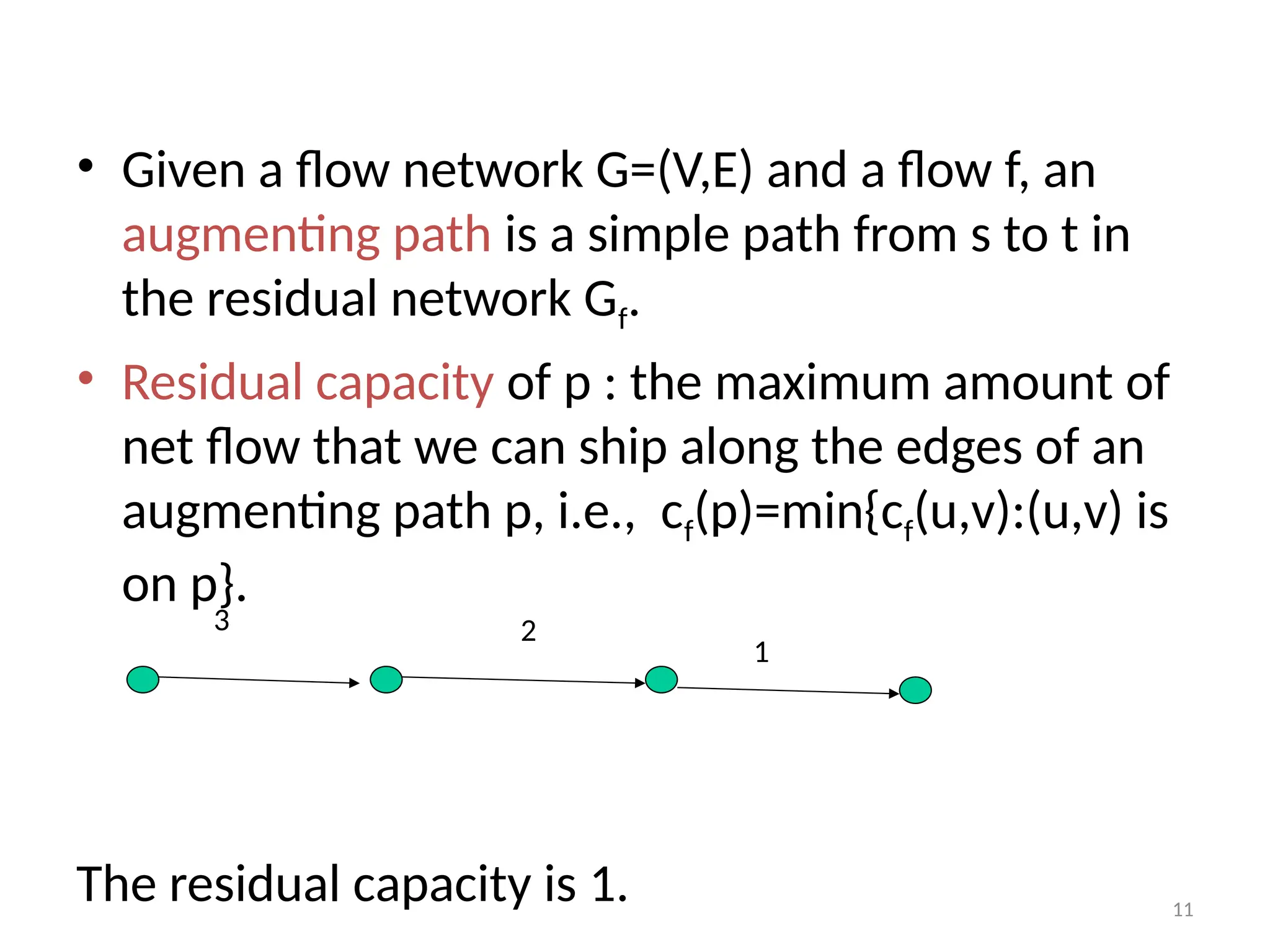

The basic Ford-Fulkerson algorithm

• FORD-FULKERSON(G,s,t)

for each edge (u,v)E[G]

do f[u,v] 0

f[v,u] 0

while there exists a path p from s to t in the residual

network Gf

do cf(p)min{cf(u,v): (u,v) is in p}

for each edge (u,v) in p

do f[u,v] f[u,v]+cf(p)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/86303192-network-flow-problem-241127132645-f9076ed0/75/86303192-Network-Flow-Problem-pptxnhghvvgcfbch-f-g-hxg-s-12-2048.jpg)