The document summarizes string matching algorithms. It discusses the naive string matching algorithm which compares characters at each shift to find matches. It also describes the Rabin-Karp algorithm which uses hashing to match the hash value of the pattern to the hash value of substrings in the text. If the hash values match, it then checks for an exact character match. The Rabin-Karp algorithm has better average-case performance than the naive algorithm but the same worst-case performance of O((n-m+1)m) time.

![String Matching

Algorithms

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Introduction

Text-editing programs frequently need to find all occurrences of a pattern in the text.

Typically, the text is a document being edited, and the pattern searched for is a particular word

supplied by the user. Efficient algorithms for this problem called “String Matching”. It can greatly

aid the responsiveness of the text editing program. Among their many other application, string

matching algorithm search for particular patterns in DNA sequence. Internet search engines also

use them to find Web pages relevant to queries [5].

We formalize the string matching problem as follows. We assume that the text is an array

T[1….n] of length n and that the pattern is an array P[1….m] of length m<=n. We further assume

that the elements of P and T are characters drawn from a finite alphabet ∑. For example, we may

have ∑ = {0,1} or ∑ = {a,b,….,z}. The character arrays P and T are often called string of character

[5].

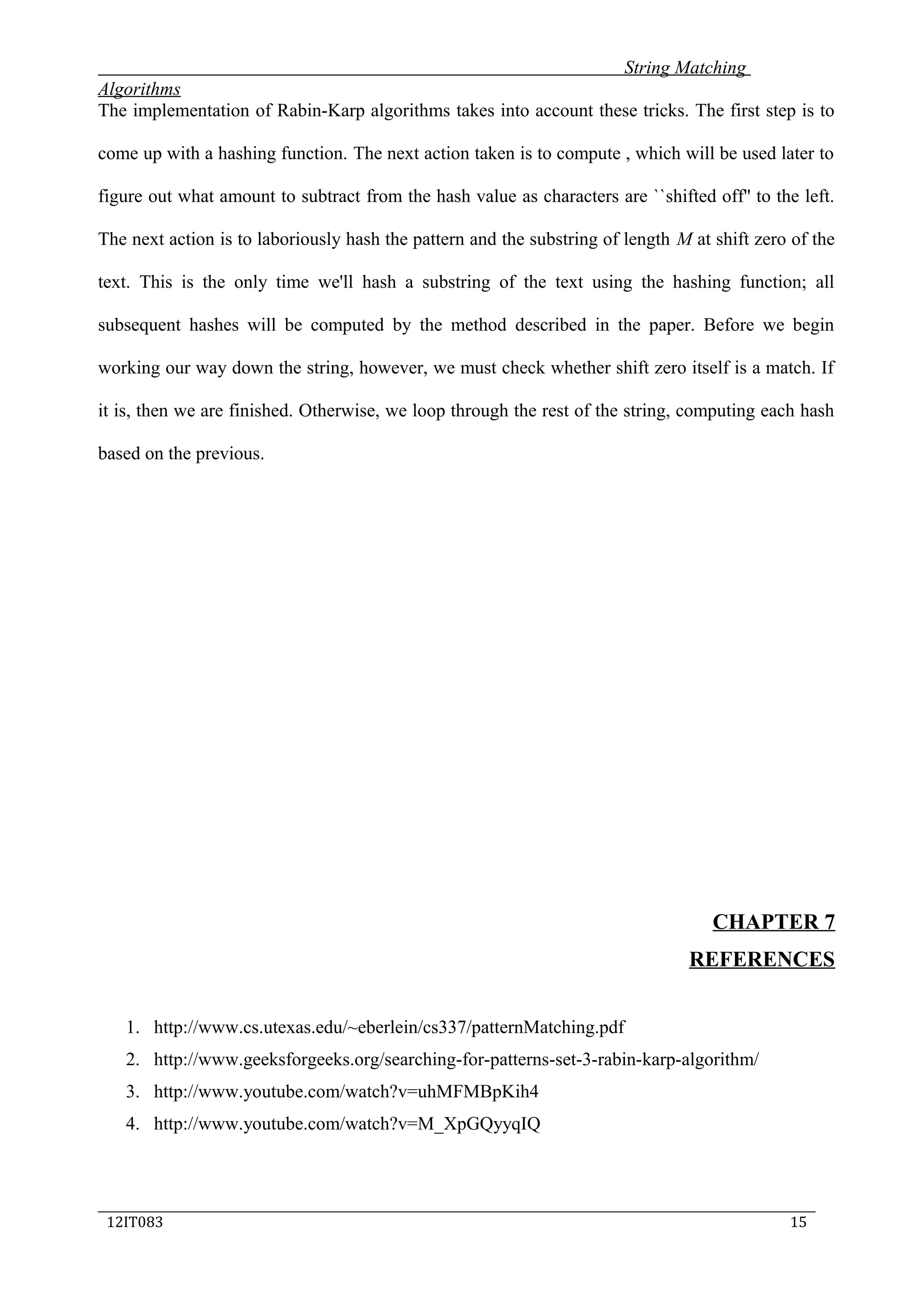

A B A C C A C C B A

_____________________________________________________________________________

12IT083 3

Text T

S = 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4reportformat-150909130156-lva1-app6891/75/4-report-format-3-2048.jpg)

![String Matching

Algorithms

Figure 1 An example of string matching problem, where we want to find all occurrences

of the pattern P = CCACC in the text T = ABACCACCBA. The pattern occurs only once

in the text, at shift S = 3, which we can call a valid shift. A vertical line connects each

character of the pattern to its matching character in the text [5].

Referring Figure 1, we say that pattern P occurs with shift s in the text T (or, equivalently,

that pattern P occurs beginning at position S+1 in text T) if 0 <= s <= n-m and T[S+1…S+m] =

P[1….m]. If P occurs with shift S in T, then we call S a valid shift; otherwise we call S an invalid

shift. The string matching problem is the problem of finding all valid shift with which a given

pattern P occurs in given text T [5].

1.2 Types of String matching Algorithms [5]

There are many types of String matching algorithms like,

(1) The Naive String matching

(2) The Rabin-Karp String matching

(3) String matching with finite automata

(4) The Knuth-Morris-Pratt

But we discuss about 2 types of String matching algorithms

1) The Naive String matching algorithm

2) The Rabin-Karp algorithm

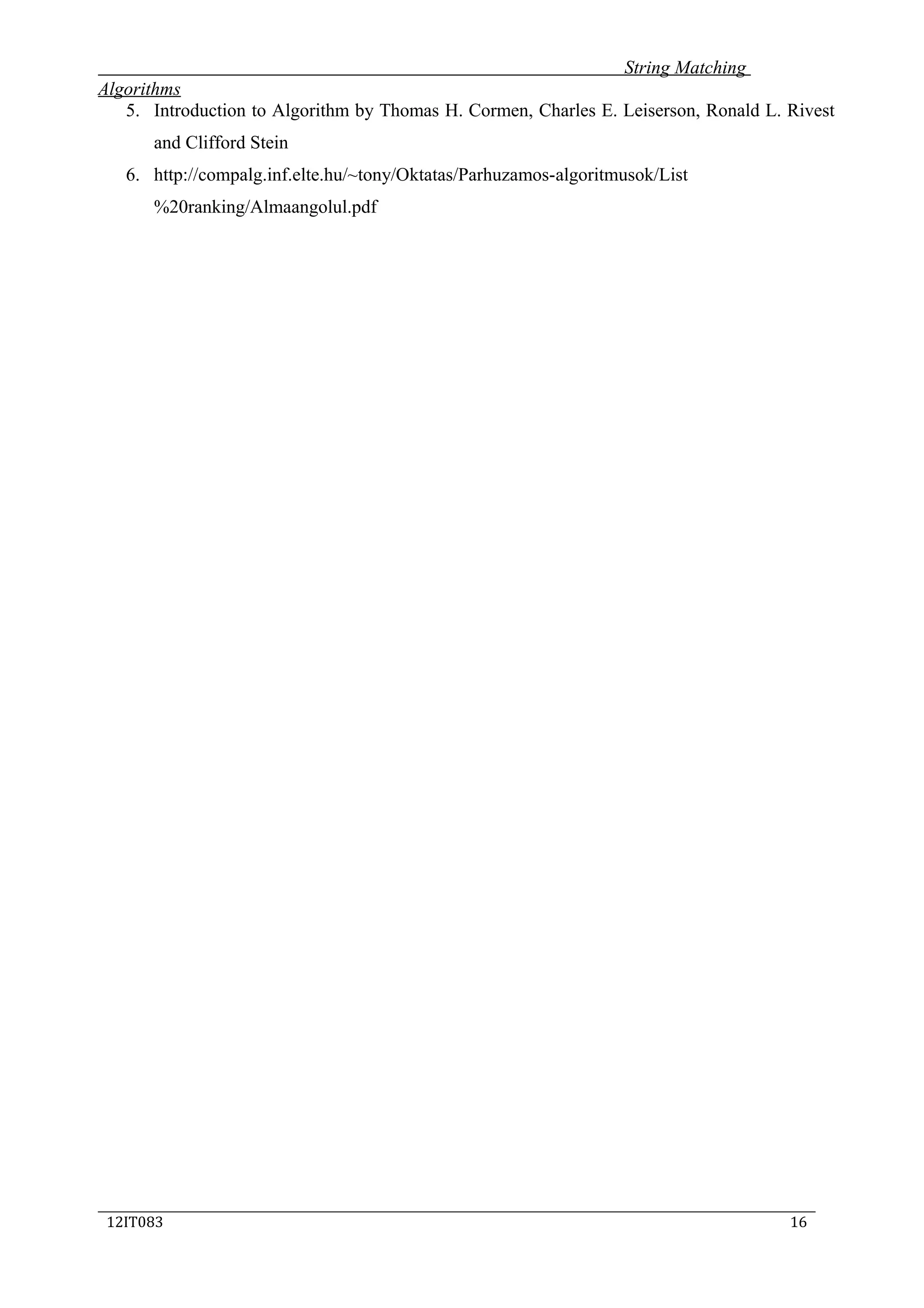

ALGORITHMS PROCESSING TIME MATCHING TIME

Naïve 0 O((n-m+1)m)

Rabin-Karp Θ(m) O((n-m+1)m)

Figure 2 The String matching algorithms in this chapter and their preprocessing and

matching times.

Except for the naive brute-force algorithm, which we review in figure 1, each string

matching algorithm in this chapter performs some preprocessing based on the pattern and then

finds all valid shift; we call this latter phase “matching”. Figure 2 shows preprocessing and

_____________________________________________________________________________

12IT083 4

C C A C CPattern P](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4reportformat-150909130156-lva1-app6891/75/4-report-format-4-2048.jpg)

![String Matching

Algorithms

matching times for each of the algorithms in this chapter. The total running time of each algorithm

is the sum of the preprocessing and matching times.

Figure 2 presents an interesting string matching algorithm, due to Rabin and Karp.

Although the Θ ((n-m+1)m) worst-case running time of this algorithm is no better than that of the

naive method, it works much better on average and in practice. It also generalizes nicely to other

pattern-matching problems.

CHAPTER 2

THE NAIVE STRING MATCHING ALGORITHM

2.1 What is Naive string matching?

The Naive String Matching algorithm slides the pattern one by one. After each slide, it one by

one checks characters at the current shift and if all characters match then prints the match. [1]

2.2 Algorithm for naive string matching [5]

The naive algorithm finds all valid shifts using a loop that checks the condition

P[1…m] = T[S+1….S+m] for each of the n – m + 1 possible values of S.

NAIVE-STRING-MTCHER (T, P)

(1) n = T.length

(2) m = P.length

(3) for S = 0 to n – m

(4) if P[1…m] == T[S+1…..S+m]

(5) printf “Pattern occurs with shift” S

2.3 How It Works [5]

Example portrays the naive string matching procedure as sliding a “template” containing

_____________________________________________________________________________

12IT083 5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4reportformat-150909130156-lva1-app6891/75/4-report-format-5-2048.jpg)

![String Matching

Algorithms

the pattern over the text, noting for which shifts all of the characters on the template equal the

corresponding characters in the text. The for loop of line 3-5 considers each possible shift

explicitly. The test on line 4 determines whether the current shift is valid or not; this test

Involves an implicit loop to check corresponding character positions until all positions match

successfully or a mismatch is found. Line 5 prints out each valid shift S.

Procedure NAIVE-STRING-MATCHER takes time O ((n − m + 1)m), and this bound is

tight in the worst case. For example, consider the text string an (a string of n a’s) and the pattern

am. For each of the n−m+1 possible values of the shift S, the implicit loop on line 4 to compare

Corresponding characters must execute m times to validate the shift. The worst-case running time

is thus Θ((n −m +1)m), which is Θ(n2)if m = [n/2]. Because it requires no processing,

NAIVE-STRING-MATCHER is running time equals its matching time.

2.4 Example [3]

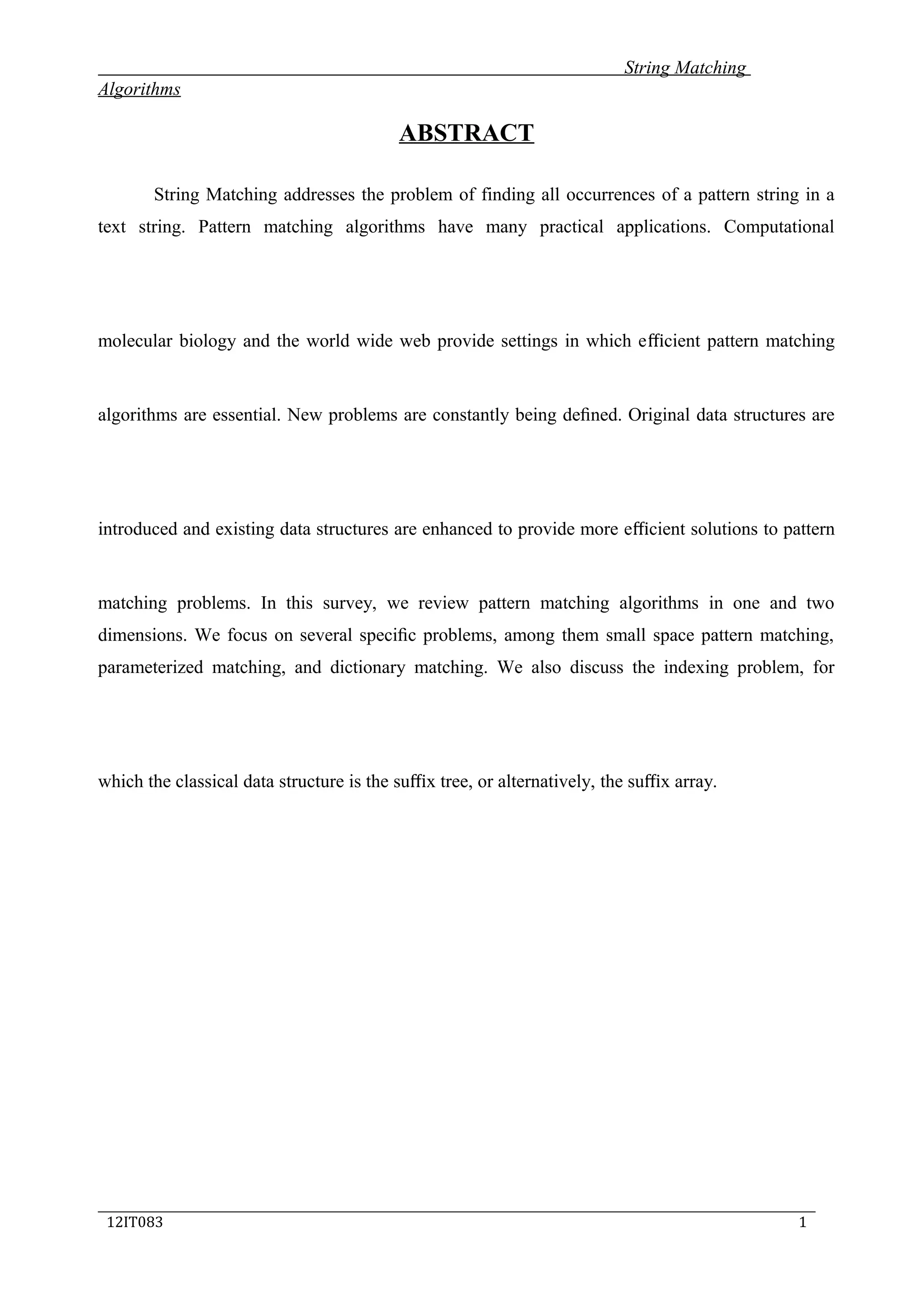

P R Q P P Q R

_____________________________________________________________________________

12IT083 6

P P Q

P R Q P P Q R

P P Q

Text T

Pattern P S=0

S=1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4reportformat-150909130156-lva1-app6891/75/4-report-format-6-2048.jpg)

![String Matching

Algorithms

P R Q P P Q R

Figure 3 The operation of the naive string matcher for the pattern P = PPQ and the text

T = PRQPPQR. We can imagine the pattern P as a “template” that we slide next to the

text. (a)–(d) The four successive alignments tried by the naive string matcher. In each

part, vertical lines connect corresponding regions found to match (shown shaded), and a

jagged line connects the first mismatched character found, if any. One occurrence of the

pattern is found, at shifts = 3.

As we shall see, NAIVE-STRING-MATCHER is not an optimal procedure for this problem.

Indeed, in this chapter we shall show an algorithm with a worst-case preprocessing time of (m)

and a worst-case matching time of (n). The naive string-matcher is inefficient because information

gained about the text for one value of s is entirely ignored in considering other values of s. Such

information can be very valuable, however. For example, if P = aaab and we find that s = 0 is

valid, then none of the shifts 1, 2, or 3 are valid, since T[4] = b. In the following sections, we

examine several ways to make effective use of this sort of information.

Time Complexity Analysis [6]

Worst-case:

_____________________________________________________________________________

12IT083 7

P R Q P P Q R

P P Q

P P Q

S=2

S=3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4reportformat-150909130156-lva1-app6891/75/4-report-format-7-2048.jpg)

![String Matching

Algorithms

CHAPTER 3

THE RABIN-KARP ALGORITHM

3.1 What is Rabin-Karp algorithm?

Like the Naive Algorithm, Rabin-Karp algorithm also slides the pattern one by one. But

unlike the Naive algorithm, Rabin Karp algorithm matches the hash value of the pattern with the

hash value of current substring of text, and if the hash values match then only it starts matching

individual characters. [2]

3.2Algorithm for Rabin-Karp[5]

P[1. .m] = T[s +1. .s +m]. If q is large enough, then we can hope that spurious hits occur

infrequently enough that the cost of the extra checking is low.

The following procedure makes these ideas precise. The inputs to the procedure are the text T,

the pattern P, the radix d to use (which is typically taken to be ∑), and the prime q to use.

RABIN-KARP-MATCHER (T, P, d, q)

1) n ← length[T]

2) m ← length[P]

3) h ← dm−1 mod q

4) p ← 0

5) t0 ← 0

6) for i = 1 to m // Preprocessing.

7) p = (dp + P[i]) mod q

8) t0 = (dt0 + T[i]) mod q

9) for s = 0 to n −m // Matching.

10) if p = ts

11) if P[1. .m] = T[s +1. .s +m]

12) print “Pattern occurs with shift” s

13) if s < n −m

_____________________________________________________________________________

12IT083 9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4reportformat-150909130156-lva1-app6891/75/4-report-format-9-2048.jpg)

![String Matching

Algorithms

14) ts+1 ← (d(ts − T[s +1]h)+ T[s +m +1]) mod q

3.3 How It Works

The procedure RABIN-KARP-MATCHER works as follows. All characters are

interpreted as radix-d digits. The subscripts on t are provided only for clarity; the program

works correctly if all the subscripts are dropped. Line 3 initializes h to the value of the high-

order digit position of an m-digit window. Lines 4–8 compute p as the value of P[1. .m] mod

q and t0 as the value of T[1. .m] mod q. The for loop of lines 9–14 iterates through all

possible shifts s, maintaining the following invariant: [5]

Whenever line 10 is executed, ts = T[s +1. .s +m] mod q

RABIN-KARP-MATCHER takes (m) preprocessing time, and its matching time is ((n −

m + 1)m) in the worst case, since (like the naive string-matching algorithm) the Rabin-Karp

algorithm explicitly verifies every valid shift. If P = am and T = an, then the verifications take

time _((n − m + 1)m), since each of the n − m + 1 possible shifts is valid. [6]

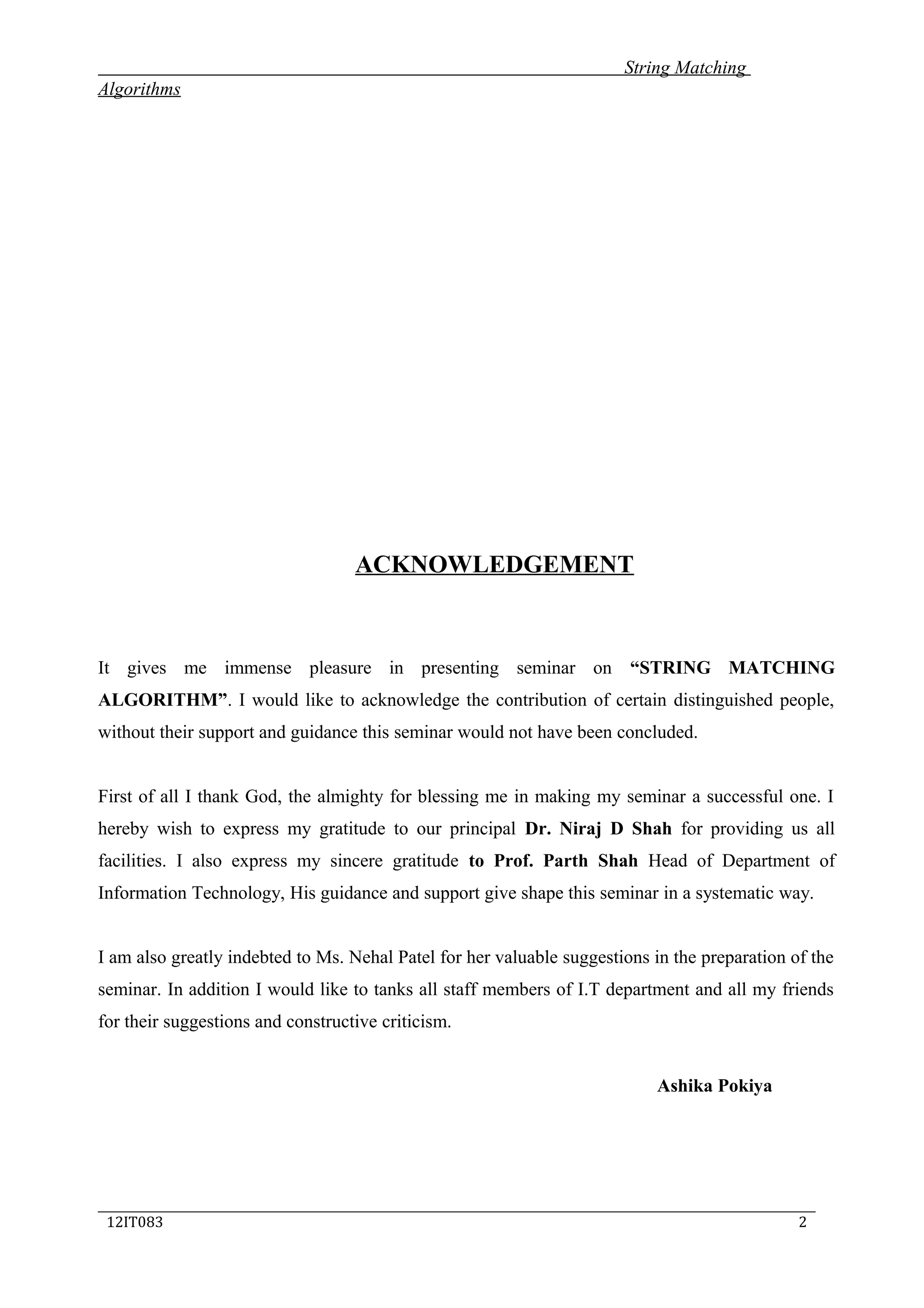

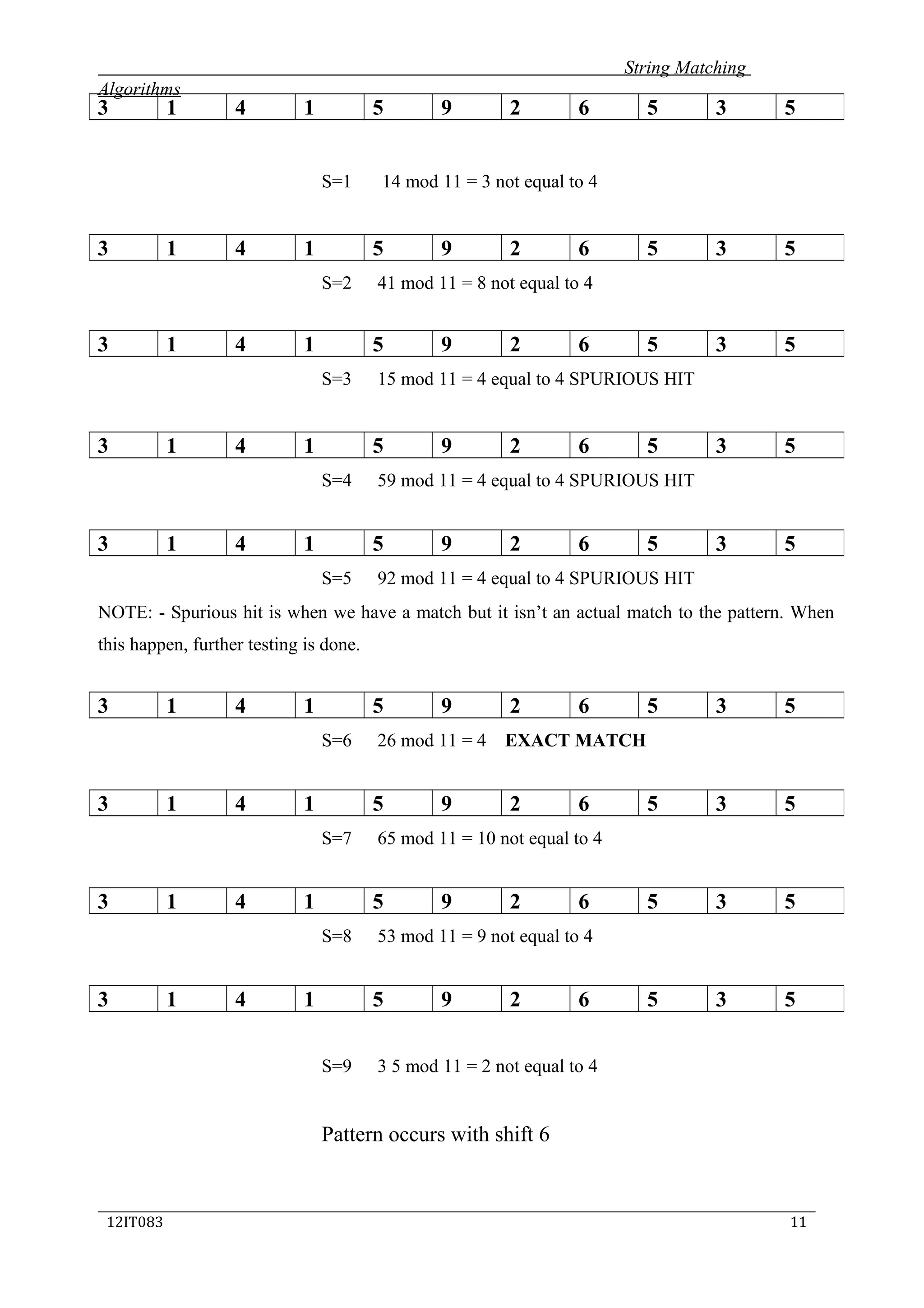

3.4Example[4]

Pattern P=26, how many spurious hits does the Rabin Karp matcher in the text

T=3 1 4 1 5 9 2 6 5 3 5.

T = 3 1 4 1 5 9 2 6 5 3 5

P = 2 6

Here T.length=11 so Q=11

and P mod Q = 26 mod 11= 4

Now find the exact match of P mod Q…

S=0 31 mod 11 = 9 not equal to 4

_____________________________________________________________________________

12IT083 10

3 1 4 1 5 9 2 6 5 3 5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4reportformat-150909130156-lva1-app6891/75/4-report-format-10-2048.jpg)

![String Matching

Algorithms

Time Complexity Analysis

The running time of Rabin-Karp matcher is θ((N-M+1) M) in the worst case, since the Rabin-

Karp algorithm explicitly verifies each valid shift. If P = aM

and T = aN

, then the verifications take

θ((N-M+1) M), since each of the N-M+1 possible shifts is valid [1]. In many applications only a

few valid shifts (perhaps θ(1) of them) and so the expected running time of the algorithm is

θ(N+M) plus the time required to process spurious hits [1].

CHAPTER 4

COMPARISON OF ALGORITHMS

4.1 Between Naive algorithm and Rabin-Karp algorithm

_____________________________________________________________________________

12IT083 12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4reportformat-150909130156-lva1-app6891/75/4-report-format-12-2048.jpg)

![String Matching

Algorithms

The Naive String Matching algorithm slides the pattern one by one. After each slide, it one

by one checks characters at the current shift and if all characters match then prints the

match. [1]

Like the Naive Algorithm, Rabin-Karp algorithm also slides the pattern one by one. But

unlike the Naive algorithm, Rabin Karp algorithm matches the hash value of the pattern

with the hash value of current substring of text, and if the hash values match then only it

starts matching individual characters. [2]

Rabin-Karp algorithm gives a better run time performance of θ(N+M), than the naive brute

force string matching algorithm θ((N-M) M). The Rabin-Karp algorithm can be very slow

if the text contains a lot of false matches. Sub strings that hash to the same number as the

pattern, cause expensive string compares to be performed. A lot of tricks as shown in the

paper, make it faster. The implementation of Rabin-Karp algorithms takes into account

these tricks. The first step is to come up with a hashing function. The next action taken is

to compute , which will be used later to figure out what amount to subtract from the hash

value as characters are ``shifted off'' to the left. The next action is to laboriously hash the

pattern and the substring of length M at shift zero of the text. This is the only time we'll

hash a substring of the text using the hashing function; all subsequent hashes will be

computed by the method described in the paper. Before we begin working our way down

the string, however, we must check whether shift zero itself is a match. If it is, then we are

finished. Otherwise, we loop through the rest of the string, computing each hash based on

the previous. [6]

CHAPTER 5

ADVANTAGES OF STRING MATCHING

5.1 ADVANTAGES

_____________________________________________________________________________

12IT083 13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4reportformat-150909130156-lva1-app6891/75/4-report-format-13-2048.jpg)

![String Matching

Algorithms

– Text-editing programs frequently need to find all occurrences of a pattern in the text.

Typically, the text is a document being edited, and the pattern searched for is a particular word

supplied by the user. [5]

– Efficient algorithms for this problem called “String Matching”. It can greatly aid the

Responsiveness of the text editing program. [5]

– Among their many other application, string matching algorithm search for particular

patterns in DNA sequence. Internet search engines also use them to find Web pages relevant to

queries. [5]

CHAPTER 6

CONCLUSION

Rabin-Karp algorithm gives a better run time performance of θ(N+M), than the naive brute force

string matching algorithm θ((N-M) M). The Rabin-Karp algorithm can be very slow if the text

contains a lot of false matches. Sub strings that hash to the same number as the pattern, cause

expensive string compares to be performed. A lot of tricks as shown in the paper, make it faster.

_____________________________________________________________________________

12IT083 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4reportformat-150909130156-lva1-app6891/75/4-report-format-14-2048.jpg)